Western Digital: From Calculator Chips to Data Infrastructure Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 1976, and Western Digital is in bankruptcy court. The company that would one day help store a huge share of the world’s data is watching its biggest customer—calculator maker Bowmar Instrument—collapse after the oil crisis. Desks get cleared. Creditors close in. The big idea of building a semiconductor powerhouse out of Santa Ana looks like it’s over.

Now jump to 2024. Western Digital is a cornerstone of modern computing. Hyperscale data centers—Amazon, Google, Microsoft—run on fleets of storage, and WD is one of the companies at the center of that world. The business that almost died selling calculator chips has become part of the infrastructure layer underneath cloud computing and the AI boom. How does a company go from Chapter 11 to the storage big leagues?

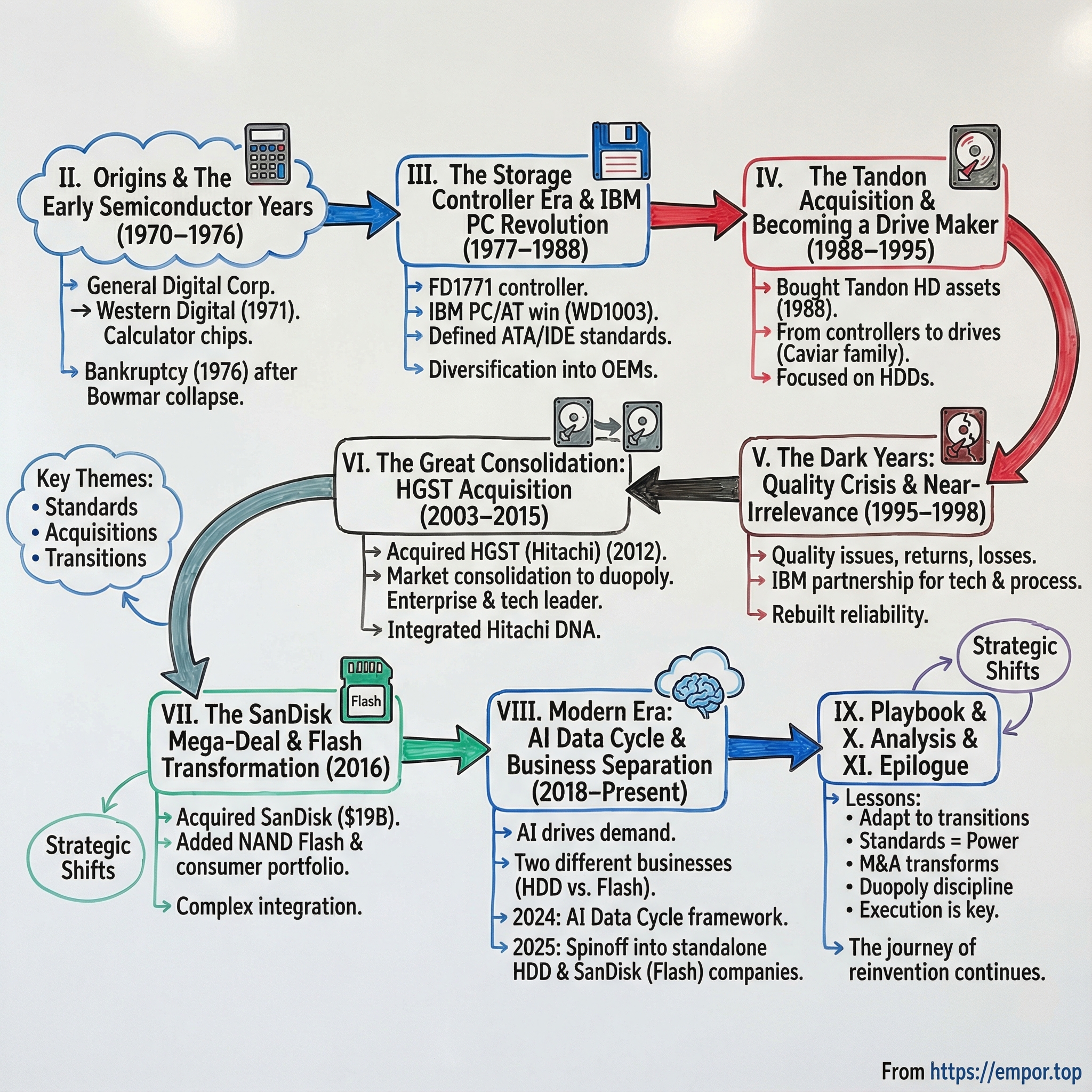

That arc is what makes Western Digital so fascinating. This isn’t a straight-line “innovate and win” story. It’s reinvention, over and over: calculator chips to disk controllers, controllers to hard drives, hard drives to flash memory, and now a new bet on what storage looks like in an AI-driven world. Along the way are quality crises, brutal competition, giant acquisitions, and regulatory fights that threatened to freeze the company in place.

Western Digital began on April 23, 1970, when Motorola engineer Alvin B. Phillips founded General Digital Corporation. In July 1971, it took the name Western Digital, a California-flavored signal that it planned to ride the next wave of electronics. Phillips’s initial plan was straightforward: build specialized chips for the growing calculator market. What followed was anything but. This same company would eventually outlast whole eras of storage history, including IBM’s hard drive business, then buy Hitachi’s storage arm, and later acquire SanDisk in a deal so big it changed the company’s identity.

At its core, this is a story about surviving disruption in a category where disruption is constant. Many names that once dominated storage—Quantum, Maxtor, Conner Peripherals—either faded or disappeared. Western Digital kept going by changing what it was, even when that meant abandoning yesterday’s strengths.

As we tell the story, three themes keep showing up. First: standards create empires. WD didn’t just sell disk controllers; it helped shape the ATA/IDE interface that defined PC storage for decades. Second: in consolidating industries, acquisition strategy is destiny. Deals like Tandon, HGST, and SanDisk didn’t merely add revenue—they rewired Western Digital’s capabilities and competitive position. Third: transitions kill complacent companies. Storage has marched from one generation to the next, and Western Digital survived by being willing to disrupt itself before someone else did.

And today, the company is staring down another defining move: spinning off the flash business it once paid $19 billion to acquire, while leaning harder into hard drives at the exact moment AI is driving a new wave of data creation. Is that disciplined focus, or the kind of strategic overcorrection that looks obvious only in hindsight?

To answer that, we have to go back to the beginning—before the hard drives, before the cloud, before “data infrastructure” was even a phrase—when Western Digital was just a small chip company trying to ride the calculator boom.

II. Origins & The Early Semiconductor Years (1970–1976)

In April 1970, Newport Beach didn’t look like the future. There were no glassy campuses or mythology yet—just low industrial buildings, forklifts, and the Southern California sun beating down on warehouse roofs. That’s where Alvin B. Phillips, a 29-year-old engineer from Motorola, opened up shop. He leased about 1,500 square feet, stitched together startup money from investors, and—most importantly—landed strategic backing from Emerson Electric. The company was incorporated as General Digital Corporation. A year later, in July 1971, Phillips renamed it Western Digital, a brand that sounded bigger than the modest space it started in.

Phillips’s bet was simple: don’t try to beat Intel and Fairchild at the broad, general-purpose game. Go where demand was screaming and specialization mattered. In the early 1970s, that meant calculators—the must-have electronics product of the era. As prices fell from the hundreds of dollars toward the mass market, calculators went from luxury to everyday tool. And every one of them needed silicon.

Western Digital’s first product, introduced in 1971, was the WD1402A UART—a Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter. Not a consumer headline-grabber, but exactly the kind of practical building block that proved the team could design real chips that customers could ship. That credibility and revenue funded the bigger prize: calculator chipsets. With products like the WD1001 set, Western Digital offered calculator makers an off-the-shelf path to a working four-function device. Instead of building their own silicon from scratch, they could buy the brain.

It worked—almost too well. By 1975, Western Digital had become the largest independent calculator chip maker in the world, with annual revenue above $25 million and a workforce of more than 1,000 people spread across California facilities and assembly operations in Mexico. Phillips had executed a classic early-stage strategy: focus hard, win a vertical, scale fast.

Then the world changed.

The mid-1970s brought a one-two punch. The oil embargo slammed consumer spending and made discretionary electronics harder to sell. At the same time, Texas Instruments pulled a move that would become a recurring nightmare in tech: vertical integration. TI started selling complete calculators at prices so low they undercut what Western Digital’s chips cost on their own. When the product becomes cheaper than the components, the component maker doesn’t just lose margin—it can lose the market.

And then Western Digital’s single biggest risk turned into a single point of failure. Bowmar Instrument, its largest customer—responsible for more than 40% of revenue—went bankrupt in 1976. The impact wasn’t gradual. It was immediate and brutal. Payroll became a question mark. Suppliers demanded cash. Lenders got nervous. In September 1976, Western Digital filed for Chapter 11.

The company that had just “won” its niche discovered the dark side of winning a niche: if the niche collapses, you collapse with it.

That’s the moment the story could have ended. Instead, it set up the pivot that defined everything that came after.

In June 1977, Chuck Missler came in as chairman and CEO. A former fighter pilot turned tech executive, Missler had a reputation for turnarounds—and he backed the job with his own money, injecting capital and becoming the company’s largest shareholder. His message to the board was blunt: Western Digital could not afford to be a one-market, one-customer company ever again. The strategy was diversification, not as a buzzword, but as a survival mechanism.

The bankruptcy left Western Digital with scars—and a new operating philosophy. Dominance in a single category was useless if the category could evaporate. Customer concentration wasn’t just bad—it was existential. And technology transitions weren’t interesting; they were lethal.

Missler also saw something else: the engineers who could build calculator silicon could build other kinds of silicon. And off to the side of the calculator bust, a new market was quietly starting to form—computers, and the storage systems they would need. Western Digital’s next act wouldn’t be selling brains to calculators. It would be selling brains to disks.

III. The Storage Controller Era & IBM PC Revolution (1977–1988)

In early 1978, Chuck Missler walked into a room full of Western Digital engineers and held up a floppy disk: an 8-inch, flexible square that looked more like a record sleeve than “the future.” His pitch was simple. Computers were spreading. Computers needed disks. And disks needed controllers. Western Digital didn’t have to build the drives to win—just the silicon that made them work.

It sounded like another niche. The team had just lived through what happens when a niche collapses.

But Missler had picked the right wedge. Floppy drives were taking off, and the electronics inside them were a mess: lots of separate TTL chips handling motor control, head positioning, data encoding, error checking—the unglamorous plumbing that made storage reliable. Western Digital’s edge was exactly the kind of integration that had once powered its calculator run. In 1978, it shipped the FD1771, one of the first single-chip floppy disk formatter/controllers. Instead of a board stuffed with logic, you could build around one chip. Less cost. Less space. Fewer failure points.

The FD1771 became Western Digital’s post-bankruptcy comeback. Drive makers like Shugart, Tandon, and TEAC adopted it, and importantly, the customer base didn’t look like Bowmar. Storage had lots of manufacturers, lots of buyers, and lots of SKUs. Diversification came baked in. By 1980, revenues had rebounded to about $45 million, and Western Digital had become a force in floppy controllers.

Then the PC revolution put rocket fuel under the controller business.

IBM, building what became the IBM PC and then the PC/AT, needed a hard disk controller that fit the economics of a mass-market personal computer. Existing options were too expensive and too complex. Western Digital pitched its way into the conversation and iterated toward what IBM wanted. The result was the WD1003, which shipped with the IBM PC/AT in 1984.

That win mattered for revenue, but it mattered even more for what it set in motion. Working with Compaq and Control Data, Western Digital helped turn controller interfaces into something the entire PC ecosystem could standardize around: ATA, later known as IDE. Western Digital wasn’t just selling a part anymore—it was helping define the rules of the road. And when you help define the standard, you don’t have to guess where the market is going. You’re standing in the middle of it while everyone else routes their products around you.

Through the mid-to-late 1980s, the business turned into a cash machine. Controller shipments went from “tens of thousands” to “millions,” margins were strong, and by 1988 revenue had climbed to $348 million. Western Digital—recently bankrupt, once written off as a calculator-chip casualty—had become one of the great tech turnaround stories of the decade.

And yet, inside the company, the mood wasn’t victory laps. It was déjà vu.

Missler and his team could see the same pattern that had destroyed them once before. Drive makers like Seagate and Quantum were increasingly integrating controller functionality into the drive itself. If the controller became part of the drive, the standalone controller supplier didn’t just lose some margin—it risked losing the whole product category. Vertical integration was back, and it was coming straight at Western Digital’s core.

So Western Digital started hedging. In the mid-to-late 1980s, it expanded beyond controllers into broader OEM PC hardware: Paradise Systems in graphics cards, Faraday Electronics in PC chipsets, and ADSI’s SCSI controller business to push into enterprise storage. Each move was defensible on its own. Together, they revealed a company that was profitable, but strategically unsettled—rich, and also scattered.

The controller era left Western Digital with a different set of lessons than the calculator bust. Standards create power. Platforms are more durable than any one chip. And vertical integration is both the threat you fear and the move you eventually have to make.

By 1988, the choice was no longer theoretical. Western Digital could stay a controller company and watch its market slowly compress as controllers disappeared into drives. Or it could do something radical: become a drive maker itself, and start competing with the very customers it had supplied.

Missler chose disruption over decay. And the bet he made next—the Tandon acquisition—would turn Western Digital from the arms dealer of the PC storage world into a front-line combatant.

IV. The Tandon Acquisition & Becoming a Drive Maker (1988–1995)

On an October morning in 1988, Western Digital executives walked into Tandon Corporation’s facility in Chatsworth for due diligence and got a sensory jolt of what they were about to buy. The place was enormous—about 400,000 square feet of assembly lines and clean-room stations, with the constant whine of disk platters spinning up for test. From an office upstairs, Tandon’s founder, Jugi Tandon—an Indian immigrant who’d built one of the biggest disk-drive operations on Earth—watched WD’s team crawl through the inventory. He was preparing to sell his manufacturing crown jewels for $122 million, a painful price for assets he’d poured years of capital into.

The deal happened because both sides were running out of options.

Tandon had been a floppy-drive giant, once doing roughly $400 million in revenue, but it had misplayed the move to hard drives. Its 3.5-inch drives developed a reputation for failure; returns piled up and PC makers started fleeing to Seagate and Quantum. Tandon needed cash.

Western Digital, meanwhile, was staring straight at Chuck Missler’s old nightmare. The company had made a fortune selling controllers, but drive makers were increasingly integrating the controller into the drive. If that trend continued—and it was—Western Digital’s core business would get designed out of existence.

So WD did the thing that feels obvious only after you’ve watched the whole industry play out: it moved from selling shovels to mining for gold. Buying Tandon’s hard drive assets gave Western Digital immediate scale—three manufacturing facilities, about 2,400 employees, and a 3.5-inch design team that had learned a lot of expensive lessons. The intent wasn’t to copy Tandon’s product line. It was to buy the factory, the know-how, and the right to get into the fight.

Wall Street hated the move. Western Digital had been a controller company with fat gross margins. Hard drives were the opposite: lower margins, brutal capital requirements, and a failure mode that didn’t show up on an oscilloscope—it showed up as angry customers sending boxes back. The stock fell sharply after the announcement. One analyst called it “strategic suicide—like Rolls-Royce deciding to make taxi cabs.”

Inside the company, the whiplash was real. WD’s controller engineers and Tandon’s drive engineers didn’t just have different specialties—they had different worldviews. One team lived in logic density and signal timing. The other lived in vibrations, alignment, and mechanical tolerances. Early integration meetings weren’t elegant collaborations; they were arguments. Should the drive design bend around the controller team’s assumptions, or should the electronics be rebuilt around the realities of the mechanics? Who owned the spec?

The breakthrough came from IBM. IBM’s research labs had developed “embedded servo” technology—magnetic patterns written on the disk surface that helped the drive position the read/write head precisely without using dedicated servo surfaces. Western Digital licensed the technology, then fused it with what it already knew better than most companies on the planet: controllers. The result was a new kind of drive—one with more brains inside it.

That became the Caviar family, launched in 1990. These drives didn’t just store data; they monitored themselves. They included on-board diagnostics, automatic mapping of bad sectors, and early forms of failure prediction. In a market where “works reliably” was the whole product, intelligence was a differentiator.

Caviar worked. Shipments ramped quickly—from hundreds of thousands in the first year to millions not long after. One model in the line, the 420MB Caviar priced at $299, became a standout hit in the desktop market. Western Digital had made the leap: from the company that helped other people’s drives work, to the company shipping the drive.

But that success came with a price: focus. To make drives the center of the company, Western Digital had to stop being a collection of interesting hardware businesses. Between 1991 and 1994, it peeled away anything that wasn’t essential. Paradise Systems, the graphics-card business, went to Philips for $45 million. Networking and floppy controller operations were sold off or shut down. The SCSI business went to Future Domain, later acquired by Adaptec. The company that had spent years trying to diversify now did the opposite—concentrating the entire organization around one product category.

Even Emerson Electric, WD’s original investor and steady presence since the early days, exited in 1994, selling its remaining stake for $230 million. It was a huge return for Emerson—and a sign that Western Digital had moved into a new phase where “patient capital” had less influence than the operating reality of the hard drive wars.

The strategy showed up in the results. Revenue climbed from $348 million in 1988 to $2.1 billion by 1994. Western Digital became the world’s third-largest hard drive maker, behind Seagate and Quantum. Headcount swelled to about 24,000 globally, with big operations in Malaysia and Thailand. And the old existential risk—being beholden to one giant customer—was gone. WD now sold to more than a thousand system builders worldwide.

From the outside, it looked like a transformation with a clean ending: controllers to drives, and a new growth engine locked in.

But Western Digital had also just done something that would define its next crisis: it picked a battlefield—3.5-inch desktop drives—and committed almost everything it had. By 1995, that commitment was about to be tested in the only way storage companies ever really get tested: by quality, reliability, and the unforgiving memory of customers who have lost their data.

V. The Dark Years: Quality Crisis & Near-Irrelevance (1995–1998)

The failure announced itself with a sound.

At first it was faint—an occasional click, like a fingernail tapping glass. Then it came faster. Louder. And then the drive would lock up completely. By late 1995, Western Digital’s returns operation in Lake Forest was getting flooded. Failed drives were coming back by the truckload—about ten thousand a day. Boxes piled up. Engineers ran marathon shifts, ripping units apart and chasing a problem that was destroying the thing WD had just spent years building: trust.

The cause turned out to be microscopic, and that was the problem. In the race for higher capacity, Western Digital pushed recording densities past what its manufacturing process could reliably handle. In its Malaysian assembly lines, tiny contamination—particles far smaller than anything you’d notice with the naked eye—made it onto disk surfaces. At full speed, when the read/write head hit one of those particles, it could crash, scrape the platter, and kick off a chain reaction: more debris, more damage, and a dead drive in hours or days. The company that had staked its future on reliability was now shipping drives that could self-destruct.

And the market didn’t wait around.

While WD was fighting fires, Quantum was executing. Its Fireball drives delivered more capacity at lower prices and failure rates that stayed under one percent. Maxtor’s DiamondMax line became the enthusiast favorite, with faster performance, quieter operation, and long warranties that made WD’s one-year coverage feel like an apology. The big system builders—Dell, Gateway, and others—didn’t make speeches about it. They just moved their orders. By 1996, Western Digital’s share slid hard, from about a fifth of the market to barely more than a tenth.

Financially, it turned into a wrecking ball. Warranty and return costs alone topped $400 million in 1996. Margins collapsed. Western Digital posted its first loss since emerging from Chapter 11: roughly $492 million. The stock cratered from the mid-forties to single digits. Analysts stopped debating strategy and started questioning whether there was even a company worth saving.

Charles Haggerty, who had taken over as CEO in 1992, reached for a classic escape hatch: leapfrog the industry with something new. Western Digital poured money into two big bets. One was the Portfolio drive, built around advanced magnetoresistive heads to push density. The other was SDX, a faster interface intended to replace ATA entirely. Both bets failed. Portfolio didn’t rescue quality—it made it worse. And SDX ran into a brick wall: it didn’t play nicely with existing systems, and Intel and Microsoft wouldn’t back it. In storage, compatibility is gravity. SDX tried to defy it, and the market shrugged.

The manufacturing engine that had powered WD’s rise now magnified its problems. Malaysia—three facilities and about 13,000 employees—had been built for scale. But scale punishes sloppy processes. Clean-room standards that held up at lower volumes broke down when production surged. Training programs designed to ramp quickly created workers who could move units, but not spot contamination risks early enough to stop them. The same expansion that had enabled the Caviar boom had quietly baked in fragility.

By early 1998, the situation turned existential. Cash dwindled to about $78 million—less than two weeks of operating runway. Banks grew hostile. Suppliers demanded cash up front. In board meetings, the conversation shifted from “fix it” to “do we file Chapter 11 again, or do we sell something to stay alive?” The company that had reinvented itself once already was staring at the possibility of not getting a second reinvention.

Then the lifeline came from an unlikely place: IBM.

IBM—the same company that had once helped WD break into storage with the PC/AT controller—offered a partnership. IBM’s disk business had technology Western Digital badly needed: advanced heads, servo systems, and, crucially, world-class clean-room and process discipline. Western Digital had what IBM didn’t: low-cost manufacturing scale and broad channel reach. They signed a technology transfer agreement: IBM would bring the brains and the process; WD would bring the factory and the distribution. It was, in effect, technological life support—IBM keeping WD alive in exchange for market access.

The recovery wasn’t cinematic. It was grinding.

Western Digital brought in Matthew Massengill as CEO, an operations veteran from Hewlett-Packard, and the new regime treated quality like a war. Drives were put through 48-hour testing before shipment. Lines that drifted above a 0.5% failure rate were shut down immediately. IBM engineers embedded alongside WD teams, shadowing processes and forcing Malaysian operations to behave less like high-speed assembly and more like precision manufacturing. It took years, but by 2001, WD’s failure rates were back in line with the industry.

Those dark years left scars—and a few hard rules that Western Digital would carry forward. In a commodity market, quality isn’t a feature; it’s the price of admission. Scaling doesn’t just amplify success—it amplifies every weakness you’ve tolerated. And “better technology” doesn’t matter if customers can’t use it or trust it. Worst of all, reputation takes years to build and almost no time to lose.

There was one more lesson, maybe the most painful: focus.

In the same period Western Digital was trying to do everything at once, competitors were specializing. Seagate was sharpening its enterprise strategy. Quantum was nailing desktop. Maxtor owned the performance crowd. Western Digital had tried to serve everyone, and ended up with a brand associated with the click of failure.

Survival now meant picking a battlefield—and committing to it with the discipline the company had almost forgotten.

VI. The Great Consolidation: HGST Acquisition (2003–2015)

The slide that changed Western Digital’s future showed up in a board meeting in September 2011.

It was a simple timeline of the hard drive industry shrinking in on itself: a crowded field in the mid-1980s, fewer players by the mid-1990s, fewer again by the mid-2000s—and now, after Seagate’s merger with Samsung, only a handful left. CEO John Coyne clicked to the next slide and asked the question that made everyone sit up straighter: what happens when there are only two?

Everyone in the room knew the answer. When an industry goes from knife-fight commodity to a tight oligopoly, pricing stops being suicidal. Margins can expand. The business can finally breathe.

The obvious target was Hitachi Global Storage Technologies—HGST. It wasn’t supposed to be available. HGST had been created in 2003, when Hitachi paid IBM $2.05 billion to combine their hard drive operations. Over time it became the industry’s quiet technology leader: first to a one-terabyte drive with the Deskstar 7K1000, a powerhouse presence in data centers with Ultrastar, and density advances competitors struggled to match.

But Hitachi’s priorities were shifting. After the March 2011 tsunami, the company needed cash and wanted to focus on infrastructure. Storage, increasingly brutal and cyclical, no longer fit the story Hitachi wanted to tell.

So in October 2011, Western Digital found itself negotiating to buy a company many people believed was better than WD.

On paper, it looked almost backwards. HGST had fewer employees and less revenue than Western Digital, but it had stronger technology and better margins. The price reflected that: $3.9 billion in cash plus 25 million Western Digital shares, valued around $900 million. Western Digital was effectively paying a premium for the more admired asset—using its own stock as currency.

And then, right as due diligence was wrapping up, nature intervened.

On October 25, 2011, Thailand suffered its worst flooding in half a century. Water swallowed Western Digital’s facilities. The Bang Pa-In industrial park—where WD produced the majority of its drives—ended up under roughly six feet of water. The damage ran past $400 million. Production halted. Across the industry, capacity dropped sharply and prices spiked almost overnight.

A deal that already looked ambitious now seemed impossible.

But the flood also rewrote the economics. With Western Digital’s output crushed and prices soaring, HGST was suddenly printing excess profit—hundreds of millions per month. The acquisition started to look less like a strain and more like a solution. HGST’s flood-era cash generation could help pay for HGST.

On March 7, 2012, Western Digital announced the acquisition. Hitachi would end up owning about 10% of the combined company. And strategically, the goal was clear: Western Digital was positioning itself to control about half the global hard drive market. The industry was tilting toward a duopoly.

Then China stepped in.

China’s Ministry of Commerce—MOFCOM—didn’t view this as a neat story of “rational competition.” Their concern was straightforward: if Western Digital combined with HGST, the merged company could dominate supply in China and squeeze local manufacturers. What was expected to be a routine review dragged on for eighteen months. And when MOFCOM finally delivered its conditions, they were extraordinary.

HGST had to operate as an independent subsidiary for at least two years. Separate R&D. Separate sales teams. Separate product roadmaps. No shared facilities, no unified purchasing, no integrated technology development.

So Western Digital bought HGST—then was told it couldn’t really merge with it.

The result was one of the strangest corporate structures in modern tech. Legally, it was one company. Operationally, it was two competitors living under the same roof. They went after the same customers. They built rival products. At trade shows, the absurdity became visible: two adjacent booths selling competing drives, both ultimately reporting to the same corporate parent.

Regulators demanded more. To address market share concerns, Western Digital completed a complicated 2012 asset swap with Toshiba. WD divested its 3.5-inch drive production assets and, in exchange, received Toshiba’s 2.5-inch manufacturing facility in Thailand. Strategically, it aligned with the market: 3.5-inch desktop drives were shrinking, while 2.5-inch notebook drives were growing. Symbolically, it was almost shocking. Western Digital was letting go of the very 3.5-inch manufacturing foundation it had built when it bought Tandon decades earlier.

But the forced separation had an unexpected upside: it kept both engines running hot.

Instead of one R&D organization swallowing the other, each company kept its momentum. HGST pushed forward with helium-filled drives that boosted capacity dramatically. Western Digital advanced shingled magnetic recording for archive and nearline use cases. Yes, there was duplication. But there was also urgency—two teams racing, not one bureaucracy consolidating.

When MOFCOM finally allowed integration in October 2015, Western Digital had two mature technology portfolios waiting to be combined. The integration still took time—HGST’s brand wasn’t fully retired until 2018—but the strategic bet had already paid off.

Financially, Western Digital emerged as a different kind of company. Before the acquisition, it was a large player in a punishing industry. After the industry consolidated, pricing became more disciplined and competition shifted from “who can cut the most” to “who can build the best.” For enterprise buyers, the reality hardened into a simple choice set: Western Digital or Seagate.

And the biggest change wasn’t just market structure—it was identity. Through HGST, Western Digital inherited something it had spent decades trying to prove it could earn: IBM’s storage DNA, passed down through Hitachi—an obsession with process, quality, and enterprise-grade reliability. The company that had nearly been destroyed by a quality crisis in the 1990s now owned one of the industry’s most respected engineering lineages.

Western Digital had used consolidation to escape commodity gravity. Now it was about to try the same trick in an even harsher battlefield—flash memory—by making a bet that would reshape the company all over again.

VII. The SanDisk Mega-Deal & Flash Transformation (2016)

On October 21, 2015, Steve Milligan walked into a Western Digital board meeting with a proposal that made even the HGST deal feel small: buy SanDisk for $19 billion. The room went quiet. Three years earlier, the board had signed off on a historic consolidation move. Now Milligan was asking them to swallow something far bigger—and far riskier.

His argument wasn’t subtle. Hard drives were still profitable, he told them, but the long-term gravity of storage was pulling toward flash. This wasn’t a “nice-to-have” adjacency. In Milligan’s framing, it was survival.

SanDisk was the prize because it wasn’t merely in flash—it was flash. Founded in 1988 by Eli Harari, the engineer behind the floating-gate breakthroughs that helped make flash memory practical, SanDisk didn’t just sell products. It helped invent categories. SD cards, USB drives, consumer flash, and a meaningful share of the SSD wave that started pushing hard drives out of performance-sensitive workloads. By 2015, it was doing $5.56 billion in revenue with about 8,800 employees—big, profitable, and strategically central.

But it wasn’t invincible.

SanDisk had spent the previous several years buying its way deeper into enterprise storage: Pliant in 2011, FlashSoft in 2012, SMART Storage Systems in 2013, and Fusion-io in 2014. Each deal made sense on a slide. Together, they created a company pulling in multiple directions. Enterprise and consumer. OEM and channel. Premium and commodity. Integration was messy, and internally the seams showed—overlapping teams, competing motions, and culture clashes that didn’t resolve themselves just because the paperwork said “acquired.”

Western Digital, meanwhile, had been quietly building its own flash and software toolkit. It bought Virident and STEC to get closer to enterprise SSDs, VeloBit for compression, Amplidata for object storage software, and Skyera for flash controllers. These were smaller, more digestible bets—but the pattern was clear. WD wasn’t dabbling. It was assembling pieces for a flash future. What it hadn’t expected was the chance to buy the keystone.

On paper, the rationale for a full combination was powerful. Together, Western Digital and SanDisk would pair a huge hard drive footprint with a meaningful position in NAND flash. More importantly, they’d be able to offer every tier of storage: hard drives for capacity, flash for speed, and combinations in between. For enterprise customers and cloud providers, that meant the promise of a single supplier across the stack—media, controllers, and finished products.

Then came the part that made the deal so hard: executing it.

SanDisk’s NAND supply wasn’t a simple “we own the fabs” story. It ran through a joint venture with Toshiba, spanning multiple fabrication facilities in Japan and dense agreements around capacity, technology development, and economics. Western Digital wouldn’t just be buying a flash company. It would be inheriting a partnership structure that forced it into a complicated relationship with Toshiba—collaborating deeply in NAND while competing in other storage markets. The strategic logic was clear; the corporate geometry was not.

And even if the legal structure could be navigated, the human one would be worse.

Western Digital was a company forged in the discipline of mechanical precision—motors, platters, servo control, vibration, reliability under shock and heat. SanDisk came from semiconductor physics—process nodes, cell architectures, electrons, yields. When integration teams sat down together, they didn’t just disagree on priorities. They used different mental models for what “good” looked like.

The customer-facing side got tangled fast too. Western Digital tried to keep the machine running by organizing around major lines—hard drives on one side, flash on the other—while sharing functions like sales and marketing. But in the market it created brand confusion. Should buyers choose Western Digital SSDs or SanDisk SSDs? What was the difference between WD Blue SSDs and SanDisk Ultra SSDs? The combined company ended up juggling overlapping brands—Western Digital, SanDisk, WD, and G-Technology—with channel partners complaining that they were being asked to sell products that competed with each other.

The early financial aftermath reflected the chaos. Integration costs piled up. Customers hesitated or shifted spending as product lines and go-to-market motions got reorganized. The stock fell hard from where it had been around the deal announcement, and the tone around the acquisition changed from “bold strategic move” to “did they just make the company too complicated to run?”

But under the noise, something important was happening: the center of gravity was moving.

Western Digital’s enterprise relationships helped pull SanDisk’s flash deeper into data centers. SanDisk’s consumer strength gave WD a retail and brand footprint it hadn’t historically owned as a hard-drive-first company. And the combined R&D firepower created a different competitive posture—one that could fund long roadmaps in both HDD and flash at the same time.

By 2018, flash had become a much bigger part of Western Digital’s mix, and the company increasingly looked like what Milligan had pitched in that boardroom: not a hard drive company with some SSDs, but a storage company spanning both worlds.

Still, the strategic question never went away. Samsung’s position in NAND was overwhelming and tightly vertically integrated. Seagate stayed a sharper, simpler pure-play on hard drives. Western Digital was straddling both—integrated enough to be complex, but not integrated enough to be Samsung.

Which set up the next twist: after spending years and billions transforming itself into a combined storage giant, Western Digital would eventually decide the answer might be to split that giant back in two.

VIII. Modern Era: AI Data Cycle & Business Separation (2018–Present)

By 2018, Western Digital had pulled off the kind of transformation that was supposed to end the story: it had become one of the very few scaled companies left in hard drives, and it had bought its way into flash with SanDisk. On paper, it was the “everything storage” company.

In practice, it was starting to feel like two companies forced to share a logo.

Inside the business, the divergence was hard to ignore. Hard drives were a long-cycle, physics-and-mechanics grind—slow, expensive generational shifts, where process discipline and manufacturing scale often mattered as much as the next breakthrough. Flash lived on a different clock: faster iteration, different capital decisions, different pricing dynamics. Even the dashboards didn’t want to sit next to each other. As the world moved toward AI and data-center-first computing, Western Digital was undeniably in the middle of the action—yet increasingly unsure how to run a single strategy across two fundamentally different engines.

AI didn’t simplify that tension; it amplified it. The same workloads that made data centers hungry for massive, cheap capacity also demanded blistering performance close to compute. Training data gets stored. Then it gets streamed to GPUs. Then the outputs get saved, served, and archived. Western Digital made the high-capacity hard drives that held oceans of data, and the enterprise SSDs that helped move the hot data fast. It was perfectly positioned—and still internally conflicted about what “the company” actually was.

One thing did become clear: the center of gravity shifted hard toward cloud customers. By Q4 2024, cloud represented 50% of total revenue. That wasn’t an abstract milestone. It was Western Digital becoming a different creature from the company that once won on desktop drives in retail boxes. Growth came from higher nearline HDD shipments and pricing, plus increased bit shipments and pricing in enterprise SSDs. The takeaway wasn’t the quarter-to-quarter detail. It was that hyperscalers were now the market.

So Western Digital reorganized around them. The logic was simple: if Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Meta, and a handful of others were the demand curve, then serving them better than anyone else became the whole game—roadmap alignment, supply reliability, and building the products that matched their architectures.

In June 2024, Western Digital introduced a six-stage AI Data Cycle framework meant to map the storage mix AI workloads needed at scale. It was positioned as a planning tool—how to build infrastructure that was scalable, efficient, and sustainable, while improving efficiency and lowering total cost of ownership. But it was also something else: a flag planted in the ground. Western Digital wasn’t trying to be just a component supplier. It wanted to be the storage architect for AI-era data centers.

That positioning showed up in the product roadmap. In October 2024, Western Digital said it was shipping the world’s highest capacity UltraSMR HDD, up to 32TB, using shingled magnetic recording. It leaned on a stack of innovations—ePMR, OptiNAND, ArmorCache, a triple-stage actuator—and a commercially available 11-disk platform. The point wasn’t that WD had added a little more capacity. It was that the company was pushing hard on what hyperscalers pay for: cost per terabyte, density, and reliability at ridiculous scale.

Financially, the business reflected the data-center tilt. Fourth quarter 2024 revenue was $3.76 billion, up 9% sequentially. For fiscal 2024, revenue was $13.00 billion, up from 2023’s $12.318 billion after the brutal downturn. Earnings per share improved too—fourth quarter GAAP EPS was $0.88 and non-GAAP EPS was $1.44—showing margin expansion as the mix moved toward enterprise.

And then the old question resurfaced, louder than ever: what, exactly, was Western Digital now?

Running HDD and flash under one roof wasn’t just complex. It forced constant tradeoffs—capital allocation, R&D priorities, go-to-market clarity, even what “success” meant. Hard drives asked for long-term mechanical and manufacturing bets. Flash asked for faster-cycle innovation and different supply-chain dynamics, including the inherited complexity of NAND relationships tied to Toshiba/Kioxia structures. The businesses didn’t just have different products. They had different operating rhythms.

By 2022 and 2023, a strategic review brought the board to a conclusion that would have sounded heretical in 2016. On October 30, 2023, Western Digital’s board unanimously approved a plan to separate its HDD and Flash businesses. The pitch was the standard breakup logic, but the underlying driver was operational reality: focused companies, clearer roadmaps, cleaner capital structures, and management teams optimized for their specific markets. Investors could choose: mature HDD cash flows or flash growth exposure.

The separation itself was anything but clean. It spanned more than a dozen countries, multiple consumer and professional brands, relationships with the world’s largest cloud providers and device OEMs, and the legal and supply structure around NAND production agreements. Entities had to be created, contracts renegotiated, supply agreements untangled. It was corporate surgery on a company that had spent a decade stitching itself together.

Leadership changes made it real. David Goeckeler was named CEO Designate for the Flash spinoff, while Irving Tan, the Executive Vice President of Global Operations, was set to become CEO of the standalone HDD company. The split wasn’t only financial. It was cultural: flash oriented toward faster innovation cycles, HDD toward operational excellence and cash generation.

Then timing complicated everything. Flash markets in 2024 were volatile—NAND oversupply collided with weaker consumer demand, and enterprise SSD adoption slowed as hyperscalers digested inventory. The separation, initially expected in mid-2024, slipped. Costs accumulated. Customers wanted clarity on product roadmaps and long-term support, and any ambiguity becomes expensive when your buyers run data centers.

On February 24, 2025, Western Digital announced it had completed the separation. Sandisk Corporation began trading on Nasdaq under the ticker “SNDK.” After months of preparation, the company that had spent decades consolidating itself—chips to controllers, controllers to drives, drives to flash—formally pulled itself apart.

The rationale was compelling and controversial in equal measure. Optimists argued the split would unlock focus and valuation—pure plays, specialized management, and a cleaner story for investors. Skeptics pointed to what gets lost: shared R&D, procurement leverage, and the ability to offer one integrated portfolio to hyperscalers at massive scale.

For the HDD business, the forward path was clearer, if narrower. It would compete in a duopoly dynamic with Seagate, where roadmaps and customer relationships matter as much as short-term pricing. Western Digital also framed HDDs as central to the AI Data Cycle: not the flashy part, but the essential part—handling ingestion and bulk storage on the way in, then preserving outputs for the long haul on the way out.

For the flash company, the challenge was different. SanDisk faced heavyweight competition from Samsung, SK Hynix, Kioxia, and Micron in NAND, where scale and process leadership can dictate who survives commoditization. SanDisk also pointed toward more ambitious bets, including its High-Bandwidth Flash (HBF) concept—bandwidth-optimized NAND positioned as potentially offering HBM-equivalent bandwidth with far greater capacity at similar cost. If it works, it opens a new lane in AI infrastructure. If it doesn’t, it’s still a reminder of what flash companies must do: keep reinventing, fast.

What made the moment so poetic is that, for Western Digital, reinvention has always involved breaking something that used to work. It broke away from calculator chips. It broke away from standalone controllers. It broke into hard drives, then into flash. And now it broke the integrated storage giant it had worked so hard to build—because the company finally admitted what the market had been implying all along: you can be broad, or you can be great, but being both at once is brutally hard.

The investor lesson is equally uncomfortable. Yes, conglomerate discounts can be real, and clarity can create value. But so do transformation costs—acquisitions, integrations, restructurings, and separations. Whether this breakup created net value won’t be decided by a press release or a first day of trading. It will be decided by execution over the next decade, in two separate companies, each facing a different version of the same Western Digital challenge: survive the next storage transition before it survives you.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Western Digital is a masterclass in strategic transformation—but not the clean, case-study version. This is transformation by demolition: tearing down what’s working before the market tears it down for you. The company has effectively reinvented itself four times: from calculator chips to controllers after the 1976 collapse, from controllers to drives in 1988, from drives to an integrated storage portfolio after the HGST era, and then back to focused pure-plays with the 2025 separation. Each reinvention came with real pain first, and value later.

Lesson 1: Technology Transitions Are Binary—Transform or Die

The storage graveyard is full of famous names: Quantum, Maxtor, Conner Peripherals, Fujitsu, ExcelStor. They didn’t all fail for the same tactical reason, but they failed the same strategic test: navigating a platform shift. Western Digital survived by treating transitions as a moment for commitment, not caution. When calculator chips commoditized, it didn’t try to squeeze out a niche; it left. When controllers started getting absorbed into drives, it didn’t argue with physics; it bought its way into manufacturing. When flash became unavoidable, it didn’t wait to be displaced; it bought SanDisk.

The pattern is consistent: see the transition early, move hard, and accept that the short-term is going to hurt. The Tandon bet shocked the market. The HGST deal got tied up in years of regulatory constraints. The SanDisk acquisition created so much organizational complexity that the company eventually chose to split. At announcement, these moves looked reckless. In hindsight, they were the price of staying in the game.

Lesson 2: Industry Standards Create Monopolistic Returns

Western Digital’s most valuable “product” in the 1980s wasn’t a controller chip—it was the standard it helped create. ATA/IDE shaped how PCs talked to storage for decades. When you help define the interface, you stop fighting for sockets one design win at a time; you become part of the default. It’s the same kind of advantage Intel earned with x86 and ARM earned in mobile.

The catch is that standards often require sacrifice. Western Digital could have tried to keep its interface tighter and more proprietary. Instead, it went for broad adoption and ecosystem momentum. The payoff wasn’t a quarter of higher margins—it was years of structural power.

Lesson 3: M&A as Transformation Is Never Just “Integration”

Western Digital’s biggest acquisitions weren’t bolt-ons. They were identity swaps. The company would buy capability, then reorganize around it. Tandon gave WD the manufacturing foundation to become a drive maker. HGST brought an enterprise-grade technology lineage and credibility. SanDisk brought NAND and a flash portfolio that WD couldn’t build fast enough organically.

And yes, each deal came with culture clash. But the deeper point is that transformative M&A changes the acquiring company as much as the acquired one. If you buy something truly strategic, you don’t get to keep operating like you did before. The integration pain isn’t an accident; it’s evidence the acquisition actually mattered.

Lesson 4: Vertical Integration Is Both Weapon and Trap

Western Digital has lived the full vertical integration loop. It started in components, moved into subsystems, then complete products, then into a broader storage stack spanning HDD and flash. Each step created leverage—until the industry shifted and that leverage turned into weight.

Controllers were great until they got integrated into drives. Drive differentiation was great until competition and scale pressures pushed it toward commodity dynamics. The integrated HDD-plus-flash model promised synergy, until complexity started taxing execution. The 2025 separation underlines a hard truth: integration can be a temporary advantage, but complexity sticks around.

Lesson 5: Duopolies Are Unstable Equilibria That Must Be Managed

From the outside, the HDD market looks simple now: Western Digital and Seagate. In reality, duopolies are fragile. The temptation to grab share through pricing is constant. The need to keep investing in R&D never goes away. And both players have to avoid behavior that invites regulatory intervention, even as they benefit from rational competition.

So “discipline” becomes a core capability. A duopoly can be extremely profitable, but it’s also mentally and operationally demanding: you’re always one bad incentive cycle away from turning a good market into a price war.

Lesson 6: Capital Allocation in Cyclical Industries Requires Contrarian Courage

Storage is cyclical, and the cycle is brutal. The trap is behaving like everyone else: cut too deep in downturns, then overspend in booms trying to catch up. Western Digital’s history shows repeated moments of acting when it felt uncomfortable—making big strategic moves amid volatility and disruption rather than waiting for calm.

That approach only works if the balance sheet can take the punch. It means preserving flexibility in good times, not maximizing every short-term return. The mechanics matter, but the real differentiator is psychological: being willing to commit when the environment is loud and uncertain.

Lesson 7: Brand Matters Less as Customers Get Smarter

Western Digital’s customer base evolved from consumers to system builders to hyperscale cloud operators. And as that sophistication increased, brand power declined. When buyers are comparing retail boxes, reputation can carry a premium. When buyers are data centers negotiating cost per terabyte at massive scale, brand is background noise.

That helps explain the company’s center-of-gravity shift toward enterprise and cloud. It wasn’t only about growth; it was about where the advantage is defensible. Consumer rewards marketing and distribution. Hyperscale rewards roadmap alignment, reliability, and economics.

Lesson 8: Complexity Is a Hidden Tax on Innovation

The post-SanDisk organization carried real complexity: overlapping brands, overlapping products, multiple go-to-market motions, and internal coordination that never shows up neatly on a financial statement. The obvious costs were integration expenses and confusion in the channel. The more damaging cost was slower decision-making and diluted focus.

The 2025 separation is best understood as paying down that hidden tax. Focused organizations don’t just run cleaner—they iterate faster, allocate capital more cleanly, and make tradeoffs with less internal friction.

Lesson 9: The Innovator’s Dilemma Is Also an Integrator’s Dilemma

Western Digital’s experience suggests a twist on the classic “innovator’s dilemma.” The problem isn’t only that new technology starts worse and then gets good enough. The problem is trying to run the old and the new inside one operating system.

HDDs and SSDs have different clocks, different economics, and different competitive sets. Trying to optimize both under one roof can produce compromise strategies—protecting one business while undercommitting to the other. The separation logic argues that, in some transitions, structure is strategy: splitting can be the clearest way to fully commit on both fronts.

Lesson 10: Financial Engineering Can’t Outrun Operational Reality

Western Digital’s biggest deals could be made to look elegant on paper—cash, stock, synergies, smart structuring. But the story keeps returning to the same constraint: operations win. Integration costs can exceed promised savings. Complexity can erode margins. Customer uncertainty can slow revenue. No spreadsheet can make incompatible rhythms compatible.

In the end, Western Digital’s long arc reinforces a simple rule: in technology, outcomes are built on execution. Finance can shape returns, but it can’t create the underlying advantage.

X. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The investment case for Western Digital in 2025 comes down to what you believe about three things: how fast storage technology shifts, how durable HDD duopoly economics really are, and whether management can execute now that the company has split in two. It’s an inflection point. AI is pulling demand forward. But the same AI era is also accelerating the transition risk underneath both businesses. The bull and bear cases aren’t just different conclusions—they’re different stories about what “storage” even is in the next decade.

The Bull Case: Duopoly Economics Meet AI Explosion

The optimistic view starts with a simple, unglamorous advantage: structure. In HDDs, Western Digital sells into a world where hyperscale cloud has become the center of gravity—cloud represented 50% of total revenue in Q4 2024, with growth driven by higher nearline HDD shipments and better pricing. That isn’t just “good demand.” It’s what pricing power looks like in a market where, for exabyte-scale deployments, buyers largely have two realistic suppliers: Western Digital or Seagate.

In that framing, AI doesn’t replace HDDs—it makes them more necessary. AI training and inference are data factories. The datasets have to live somewhere before they’re useful, and the outputs have to be stored and served afterward. The bull case says: yes, flash is essential for performance, but the world still needs the cheapest possible bulk capacity, and HDDs remain the economic workhorse for that job.

Western Digital’s product roadmap supports the argument that HDDs still have runway. The company has been pushing capacity upward with innovations like shingled magnetic recording, and it has talked publicly about shipping 32TB UltraSMR drives. If WD can keep extending areal density, then it keeps lowering cost per terabyte—and in nearline storage, cost per terabyte is the product.

Financially, the appeal of a standalone HDD business is straightforward in the bull case: a big installed base, long relationships with hyperscalers, and an industry structure that allows rational pricing instead of constant share wars. The bet is that this is a cash-generating duopoly, not a dying commodity category.

The split is also central to the optimistic narrative. Removing the “conglomerate” structure lets each business tell a cleaner story, run a clearer roadmap, and be valued like a focused company instead of a complicated mix. In that world, the separation isn’t a retreat—it’s a catalyst.

And finally, the bull case leans on management credibility. This is a team that lived through a flood that wiped out core production, integrated HGST under unusually restrictive regulation, and absorbed SanDisk’s complexity. Supporters see the separation as another hard operational project the company can execute—not financial engineering, but focus by operators.

The Bear Case: Technological Obsolescence Meets Margin Compression

The pessimistic view begins with the uncomfortable truth that HDDs are mechanical devices in a world that keeps moving toward solid state. The bear case isn’t that HDDs vanish next year. It’s that they’re on the wrong side of the long-term trend, and AI can mask that for a while by inflating near-term demand.

In that story, today’s duopoly is less fortress and more temporary truce. Hyperscalers are huge, sophisticated buyers, and nearline demand is concentrated among a small set of customers. If even one major cloud player changes its architecture meaningfully—leaning harder into SSDs, tape, or custom approaches—the pricing equilibrium can crack fast.

The bear case also points to the hard limits of the HDD roadmap. As densities rise, reliability gets harder and the engineering gets more complex. Meanwhile, flash has continued scaling through 3D NAND. Even if HDDs stay cheaper for cold capacity, the bear argument is that the gap narrows over time, and “good enough” SSD economics eventually spread into workloads that used to belong to disk.

Then there’s geopolitics and supply chain risk. Western Digital has meaningful exposure to Asia manufacturing and Chinese customers. In a world of export controls, shifting trade rules, and rising US-China tension, bears see a category that could get pulled into broader technology restrictions—and a company with enough regional concentration to feel it sharply.

The separation itself is also read as a warning sign. If the integrated HDD-plus-flash model created durable advantage, why unwind it? Bears argue the split is an admission that the combined company became too complex to run effectively—and that the process adds real costs: duplicate infrastructure, lost scale benefits, and a transition window competitors can exploit.

The Balanced View: Durable Cash Flows, Uneasy Growth

A more neutral view lands between those two extremes. HDDs likely don’t disappear, but they also don’t look like a growth engine forever. Units can decline while exabytes shipped rise, and revenue can be supported by mix shifting toward enterprise and nearline. That can still produce strong cash flow—but it’s a business that has to keep earning the right to exist each generation.

In that middle case, the split creates two cleaner companies, but not necessarily two great ones. The HDD business becomes a focused, cash-oriented duopoly player. The flash business (SanDisk) competes in a brutal NAND landscape against much larger and deeply integrated rivals. Focus helps. It doesn’t remove the fundamental competitive realities.

So valuation becomes less about heroic upside and more about what you’re paying for cash flows under uncertainty. If you believe the HDD duopoly stays rational and AI keeps pulling capacity demand forward, then the story can work. If you believe flash keeps eating storage while hyperscalers keep squeezing suppliers, then “cheap” can turn into “cheap for a reason.”

Ultimately, Western Digital in 2025 isn’t a simple bet on one product. It’s a bet on how the storage stack evolves—and on whether two newly separated companies can execute cleanly while the ground beneath storage shifts again.

XI. Epilogue & "If We Were CEOs"

Walk through Western Digital’s headquarters and you can feel the company’s whole arc in the décor. The walls are lined with framed patents and product callouts: the WD1402A UART from 1971, the FD1771 floppy controller, the WD1003 that helped set PC storage standards, the first Caviar drives that pulled WD into the hard drive wars. It’s a museum of reinvention—and a reminder that in this business, even the “revolutionary” becomes routine, and then obsolete.

The same goes for the decisions made in those conference rooms: Chuck Missler choosing to leave calculators behind, the board approving Tandon and turning WD into a drive maker, Steve Milligan signing up for the SanDisk leap. Each one was a destruction-and-creation moment. Each one also carried a quiet truth: the company never got to stand still.

So, if we were CEO of the newly independent Western Digital—the HDD company—what would we do?

We’d keep the strategy brutally clear: run the duopoly for what it’s worth, and do it with discipline. Not because the business is “dead,” but because it’s mature, cyclical, and concentrated. The job is to compound cash flow while HDDs remain the cheapest way to store massive amounts of data at scale.

That playbook has three pillars.

First: operational excellence, treated as the product. Not vague “efficiency initiatives,” but a culture where every defect is a real business threat and every avoidable dollar of cost is a strategic gift to Seagate. The goal would be relentless manufacturing and supply-chain improvement—automation where it pays, tighter process controls, and quality systems that prevent a 1990s-style reputation hit from ever becoming possible again.

Second: aim R&D at one north star—density and cost per terabyte. The world has already decided where performance lives, and it isn’t in spinning disks. The win condition for HDD is straightforward: keep pushing capacity higher so hyperscalers can store more data with fewer drives, less power, and less footprint. That means focusing engineering resources on whatever actually moves the density curve, without getting distracted by “nice-to-have” improvements that don’t change the economics.

Third: treat capital allocation like a promise. In a business that’s inherently cyclical, shareholders don’t want an empire-building story. They want a company that invests enough to keep the technology roadmap credible, maintains a resilient balance sheet for downturns, and then returns excess cash in a predictable way. The pitch isn’t glamour. It’s reliability—financially, the same way the product has to be reliable technically.

For SanDisk—the newly independent flash company—the strategy would have to be different. Flash is a knife fight: faster iteration cycles, different pricing dynamics, and competitors with massive scale. You can’t manage it like an HDD business and expect to win.

The opportunity, though, is real. If global supply chains keep fragmenting and geopolitics keeps mattering, large customers and governments will care more about trusted supply and resilience—not just lowest cost. That creates an opening for a Western-aligned flash supplier with credibility.

A SanDisk “CEO plan” would start with focus.

First: make the portfolio and go-to-market unambiguous. Flash is broad—consumer, client, enterprise—but not all lanes are equally defensible. The company would need to decide where it can sustainably differentiate, and where it’s better off not fighting a scale war.

Second: invest in the technologies that could actually change its negotiating leverage. Concepts like High-Bandwidth Flash are interesting precisely because they imply a world where NAND isn’t only a commodity input—it becomes a system-level advantage for AI-era infrastructure. That’s the kind of bet that, if it works, changes how customers value you.

Third: win trust with the customers that care most about continuity and qualification—large enterprises, cloud operators, and government-linked buyers—by being exceptionally dependable on roadmap clarity, supply commitments, and long-term support. Flash buyers may be price-sensitive, but the biggest ones are also risk-sensitive. Being the vendor that doesn’t surprise them can be a competitive weapon.

All of this rolls up into the question that will hang over the story for years: was the split the right call?

It was probably inevitable. HDD and flash have different clocks, different capital needs, and different competitive sets. Running them inside one structure forces compromises, and compromises are where execution goes to die. But the timing will always be debated. Separations are disruptive by nature, and doing one while customers are re-architecting around AI introduces extra uncertainty. It’s not hard to imagine a world where a few more years of simplification inside the integrated company could have captured more value before pulling the businesses apart.

That said, “should we have done it earlier or later?” is ultimately less important than “can we execute now?” Splits are messy. Employees leave. Customers worry about roadmaps and support. Competitors whisper. The first year after a separation is where value is either protected—or quietly given away.

The broader lesson here is structural, and it shows up across tech history: corporate structure has to match what the industry is becoming. When an industry consolidates, scale can be destiny—HGST is the example. When technologies diverge and operate on different rhythms, forcing them into one operating system can become a tax you can’t afford—hence the separation.

And for investors, Western Digital’s story is a live experiment in mature tech economics. Can a concentrated, cyclical hardware business generate durable shareholder returns through ruthless execution and disciplined capital allocation? Can a flash company carve out defensible ground against scaled, vertically integrated giants? The answers won’t show up in a single quarter. They’ll show up over a cycle.

There’s also a final irony worth sitting with. Western Digital helped standardize storage in the PC era. Standards are powerful—but they also make products interchangeable, and interchangeable products become commodities. WD benefited enormously from the world it helped create, and then had to spend decades fighting the consequences.

If there’s one takeaway from Western Digital’s journey, it’s not “be bold” or “do big acquisitions.” It’s simpler, and harder: in technology, permanence is the mirage that kills you. Every advantage decays. Every category shifts. The companies that last are the ones that plan for the day their best business stops being their best business—and act before the market forces them to.

Now the next chapter starts: two companies where there was one. Less hedging, more clarity. Cleaner stories—and nowhere to hide. Whether it creates or destroys value will be decided the only way it ever is in storage: by execution.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music