U.S. Bancorp: The Minneapolis Banking Machine

I. Introduction

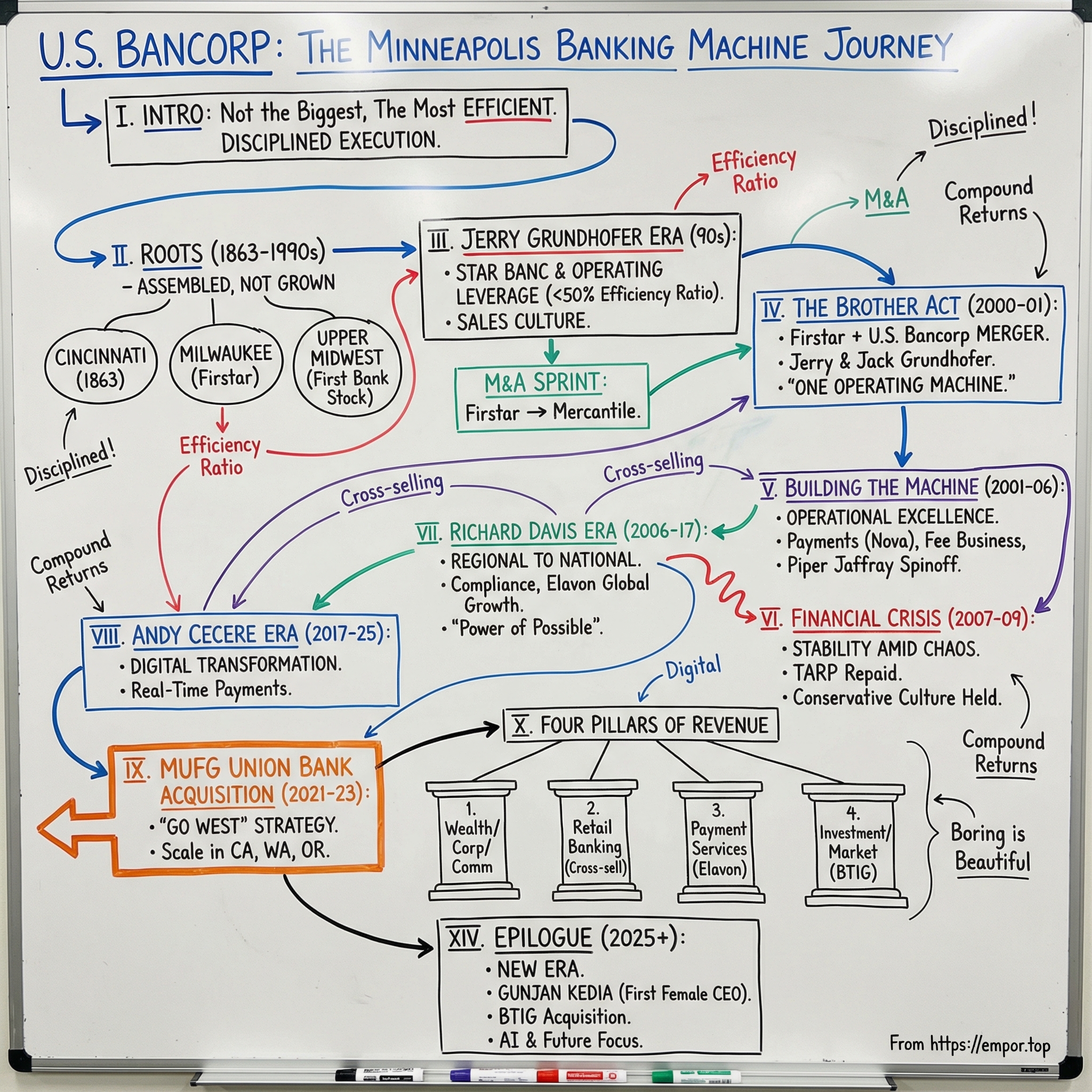

When people think about American banking power, they picture the glass canyons of Wall Street or the sprawling headquarters of Charlotte. They don’t usually picture Minneapolis.

But about twelve hundred miles from New York, in a city famous for lakes, winter, and Midwestern understatement, sits one of the most impressive banking franchises in the country. U.S. Bancorp, headquartered in Minneapolis, was the fifth-largest bank in the United States by assets as of late 2025, with roughly $695 billion on its balance sheet. It was the largest bank domiciled in the Midwest. And the Financial Stability Board considered it systemically important.

So how did a Midwest regional bank become America’s most efficient banking powerhouse?

That’s the story here. Not a story about being the biggest—U.S. Bancorp was never going to out-JPMorgan JPMorgan, or out-scale Bank of America. This is a story about being better. About disciplined, almost relentless execution. About taking a messy patchwork of acquired banks and welding them into a machine that, year after year, generated returns that much bigger peers envied.

The timeline runs all the way back to 1863, when a banking charter was granted in Cincinnati during the Civil War. From there, it winds through decades of quiet Midwestern consolidation, then accelerates into the merger wave of the late 1990s and early 2000s—the period when the company’s identity was truly forged. Along the way, two brothers from a modest home in Glendale, California helped build one of the most famous sales cultures in banking. Their successors then navigated the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, doubled down on payments and digital infrastructure, and eventually made a major land grab on the West Coast. And by 2025, the company was preparing for another new era, naming its first female CEO, Gunjan Kedia.

A few themes will keep showing up: operational excellence, a hard-edged cross-selling culture, aggressive but well-timed M&A, and an obsession with something most people outside banking never think about—the efficiency ratio. That ratio—how many cents a bank spends to earn a dollar of revenue—became U.S. Bancorp’s true north for decades.

II. The Pre-History: Multiple Roots (1863–1990s)

Every great institution has an origin story. U.S. Bancorp has several—stacked on top of one another like geological layers.

Its family tree is famously complicated: a century and a half of mergers, name swaps, and holding-company reshuffles. But the complexity isn’t trivia. It explains how a bank headquartered in Minneapolis ended up with a broad footprint, a mix of businesses, and—most importantly—a culture that treats integration not as a one-off event, but as a core skill.

The oldest strand starts in Cincinnati. In 1863, just after Congress passed the National Bank Act—Lincoln-era wartime legislation that created the national banking system—First National Bank of Cincinnati received one of the earliest federal banking charters. That charter, the second oldest in the system, would travel across corporate parents for more than a century, eventually ending up under Star Banc Corporation.

Another strand begins in Milwaukee. In 1853, Farmer’s and Millers Bank opened its doors. Over decades of mergers and renamings, it became First Wisconsin National Bank by 1919—one of the anchors of Milwaukee finance. That lineage ultimately became Firstar Corporation, the platform that would later help assemble the modern U.S. Bancorp.

Then there’s the Upper Midwest thread—the one that made Minneapolis the center of gravity. In April 1929, just six months before the stock market crash, eighty-five banks across the Ninth Federal Reserve District—Minnesota, the Dakotas, Montana, and parts of Wisconsin and Michigan—joined a loose confederation called First Bank Stock Investment Corporation. This was the age of “chain banking”: regulators made interstate branching difficult, so bankers stitched together networks through common ownership instead. Over time, that confederation evolved into the entity that carried the U.S. Bancorp name into the modern era.

And finally, there’s the name itself. “U.S. Bank” first appeared far from Minneapolis, on the West Coast, when United States National Bank of Portland was founded in Oregon in 1891. It sounds like an odd starting point for a Midwestern powerhouse, but that Oregon franchise would become strategically valuable once the company started building a truly national footprint decades later.

The takeaway isn’t the exact sequence of dates and corporate titles—banking historians can spend whole careers on those. It’s the pattern. U.S. Bancorp didn’t grow as one bank in one city, steadily expanding outward. It was assembled. Its real advantage wasn’t a single legacy franchise; it was the ability to take different banks, different cultures, and different systems—and turn them into one operating machine. That capability would soon be tested at a much larger scale.

III. The Jerry Grundhofer Era Begins: Star Banc Years (1990s)

Jerry Grundhofer didn’t come up through the usual pipeline of polished prep schools and family connections. He and his older brother Jack grew up in a modest home in Glendale, in the foothills outside Los Angeles. Their father was a bartender. Their mother worked as a caterer and a maid. Money was always tight, but the family still found a way to put the kids through Jesuit schools—Loyola High School, then Loyola Marymount University. Jerry’s first job was parking cars at church. Jack coached him in baseball. It’s the kind of background that tends to produce either chip-on-the-shoulder ambition or quiet gratitude. In Jerry, it seemed to produce both.

He entered banking and eventually landed at Star Banc Corporation, a Cincinnati-based holding company that traced its lineage back to that 1863 national bank charter. Star Banc was solid, Midwestern, and unflashy—the sort of bank that could coast on decent market share and steady deposits. Grundhofer wasn’t interested in coasting. He brought urgency, and with it a management idea that became his trademark: “operating leverage.”

The logic was straightforward and unforgiving. He wanted the bank to spend less than fifty cents for every dollar it brought in. In banking terms, that meant driving the efficiency ratio below 50%. At the time, many banks were living in the 60s and 70s—comfortable, but bloated. Grundhofer wanted a machine.

But he didn’t try to cut his way to greatness. He paired cost discipline with something many banks then resisted: a true sales culture. In the early 1990s, most retail banks still acted like civic utilities. Open the doors, staff the teller line, and wait for customers to show up. Grundhofer flipped that mindset. He emphasized low-cost retail products, then trained employees to sell around them—to cross-sell checking customers into credit cards, cardholders into mortgages, mortgage customers into investments and insurance. Every month, he sat down with the heads of the major business lines and went through the numbers. Revenue had to grow. Costs had to stay tight. No excuses.

To keep the whole organization pointed in the same direction, each business unit signed onto something called the “Five-Star Service Guarantee.” On the surface, it was customer-friendly promises about service quality and responsiveness. Internally, it was something more valuable: a discipline system. It created clear expectations and made performance visible—exactly the kind of structure that helps a sprawling bank behave like one company instead of a loose federation of branches.

Then Grundhofer started buying scale.

In 1998, Star Banc acquired Firstar Corporation, the Milwaukee-based franchise descended from the old Farmer’s and Millers Bank. The combined company kept the Firstar name—a signal that this wasn’t just a merger, but an attempt to build a larger Midwestern platform with a stronger brand.

And almost immediately, he went again.

In early 1999—just months after the Star Banc–Firstar deal closed—Grundhofer announced that Firstar would pay $10 billion for Mercantile Bancorp of St. Louis, a regional holding company with $33 billion in assets. Analysts were stunned. Integration teams were still untangling systems and cultures from the previous merger. The conventional playbook says you digest before you hunt again. Grundhofer’s view was different: in a consolidating industry, the window doesn’t stay open for long. If the right asset is available at the right price, you move. He even admitted he would have preferred to go slower. He just didn’t think the market would let him.

What made this more than bravado was that it worked. Over his three years leading the Firstar franchise, the company grew roughly eightfold. Earnings kept rising even as complexity piled up.

The deeper proof point wasn’t simply that he could buy banks. It was that his operating system traveled. He could bolt it onto acquired franchises—cost discipline, cross-selling, service guarantees—and it would take. That’s rare in banking, where mergers often turn into multi-year IT slogs, cultural stalemates, and promised savings that never quite appear. Grundhofer’s team, deal after deal, actually delivered.

IV. The Brother Act: Firstar–U.S. Bancorp Merger (2000–2001)

Jerry Grundhofer once joked that if his bank ever merged with his older brother’s, their mom would end up as CEO. She didn’t—but the fact that two siblings were running the would-be partners made what came next one of the strangest, most watchable matchups in American banking.

By 2000, Jack Grundhofer was in the top job at U.S. Bancorp in Minneapolis—the bank that had grown out of the First Bank Stock network and, through a long string of combinations, carried the U.S. Bank name into the modern era. It was a serious institution, but Jack thought it needed more scale and a bigger base to really compete. U.S. Bancorp had valuable fee businesses and investment banking horsepower through Piper Jaffray. What it didn’t have, at least to the same degree, was the relentless retail sales engine and cost discipline Jerry had drilled into Firstar.

Jerry saw the same equation from the other side. Consolidation was moving fast, and he believed the window to buy U.S. Bancorp wouldn’t stay open. If Firstar waited, someone else would take the shot. And strategically, the fit made sense: Firstar’s low-cost retail machine paired with U.S. Bancorp’s fee-driven businesses. The overlap was manageable. And as bank-merger risks go, “the CEOs are brothers” is about as close as you get to a built-in communication channel.

The transaction closed in 2001. Firstar bought U.S. Bancorp for roughly $21 billion, and then did something that told you exactly who was really acquiring whom: it took the U.S. Bancorp name and moved the headquarters to Minneapolis. Jerry became president and CEO of the combined company, now the nation’s eighth-largest commercial bank. Jack became chairman of the board.

Wall Street didn’t exactly exhale. This was peak mega-merger era, and plenty of “can’t miss” bank combinations were turning into expensive, slow-motion problems—culture clashes, messy conversions, and cost saves that never arrived. Against that backdrop, the idea that two brothers could stitch together two big banks and make it look easy sounded, depending on your mood, either charming or wildly irresponsible.

And yet: it worked.

The brothers didn’t treat the deal like a conquest. They treated it like a build. Jerry brought the system—operating leverage, the sales culture, the Five-Star Service Guarantee—and pushed it across the combined franchise. Jack brought steadiness, institutional credibility, and a chairman’s hand on the wheel while the integration machine ran. The conversion stayed on track, the savings showed up, and performance improved.

When Jack retired at the end of 2002, Jerry took the chairman role too. By then, the new U.S. Bancorp wasn’t just a larger Midwest bank. It was a real multi-region franchise—reaching from the Pacific Northwest through the Upper Midwest and into markets like Ohio and Missouri—run with a single operating playbook.

The part skeptics underestimated wasn’t sentimentality. It was coordination. The Grundhofers had been running side-by-side their whole lives—competing as kids, following the same schools, then rising through the same industry. In a business where most mergers fail on miscommunication and mistrust, they had a head start that no integration consultant can sell: they already spoke the same language.

V. Building the Machine: Operational Excellence (2001–2006)

With the mega-merger behind him, Jerry Grundhofer went back to what he did best: turning a big, complicated bank into something that ran like a machine. The goal wasn’t flashy growth. It was repeatable performance. Keep the efficiency ratio relentlessly low, make cross-selling a habit instead of a slogan, build real fee businesses like payments, and stay away from the kind of exotic risk that was starting to creep into the industry.

The sales engine kept compounding. U.S. Bancorp opened student-loan, auto-leasing, and home-mortgage units, and pushed investment and insurance products through the branch network. By the summer of 2003, the bank had about 220 branches in California and had become the nation’s largest real-estate lender. That same summer, it made a serious push into corporate banking in downtown Los Angeles—an almost poetic return to the city where the Grundhofer brothers had grown up, long before either of them ran a bank.

Grundhofer kept buying too, but now it was more surgical than sweeping. He acquired Leading Mortgage Company of Defiance, Ohio, and Nova Corporation of Atlanta, the country’s third-largest payment processor. Nova mattered far more than its headline might suggest. Payment processing—the plumbing that makes a card swipe turn into money in a merchant’s account—was turning into one of the best businesses in finance: high growth, strong margins, and anchored by scale. Many regional banks treated it like a back-office utility. Grundhofer treated it like a core franchise worth building.

And then came the move that surprised people who assumed every bank wanted more Wall Street. Grundhofer spun off Piper Jaffray, the investment-banking subsidiary that had been one of U.S. Bancorp’s marquee assets. The logic was simple and disciplined. Piper was a good business, but it was volatile, capital-intensive, and culturally different from what he was constructing. Grundhofer didn’t want a single swingy business line whipsawing the earnings profile of a bank he wanted to feel steady and predictable. The spinoff was a declaration: U.S. Bancorp was going to win by being focused, efficient, and consistent—not by trying to be everything.

By 2004, U.S. Bancorp had more than $189 billion in assets, nearly 2,300 bank offices, and 4,500 ATMs spread across 24 states, still operating under the Five-Star Service Guarantee. That May, Grundhofer said he had no plans for further major acquisitions. Translation: the platform was in place. Now the job was to run it.

The proof showed up in one number the bank lived and died by. During this period, the efficiency ratio sat in the mid-to-low 40s—an almost absurd result by the standards of the era, and a level most competitors simply couldn’t touch. It didn’t come from one breakthrough. It came from hundreds of small improvements, stacked and restacked quarter after quarter. Grundhofer’s management meetings were famous for how granular they got: cost-per-transaction in the ATM network, cross-sell performance in Des Moines versus Portland, expense creep in one unit versus another. He managed the bank the way a manufacturing executive might run a factory floor—except the “factory” held nearly $200 billion in assets.

For investors, the bet was clear. U.S. Bancorp wasn’t built to deliver occasional blowout quarters like an investment bank in a boom. But it also wasn’t built to blow up. And as other institutions piled into mortgage-backed securities and structured credit, the value of U.S. Bancorp’s boring, engineered consistency was about to get very real, very fast.

VI. The Financial Crisis Test: Stability Amid Chaos (2007–2009)

When the financial system started cracking in 2007 and then broke wide open in 2008, this was the exam U.S. Bancorp had been studying for—whether it meant to or not. Years of conservative underwriting, an allergy to “too clever” products, and that relentless efficiency discipline were suddenly the difference between embarrassment and survival.

The machine held.

As Citigroup required a massive government rescue, Wachovia was forced into a hurried sale, and Washington Mutual failed in the largest bank collapse in U.S. history, U.S. Bancorp stayed in the black. Not just standing—profitable. Quarter after quarter through the crisis and the recession that followed, it remained the only bank in its large-peer group to do so. The same traits that could look almost boring in a boom—tight risk controls, avoiding exotic structured exposure, and a cost structure with real margin for error—turned out to be exactly what the moment demanded.

That didn’t mean U.S. Bancorp walked away untouched. On November 14, 2008, the U.S. Treasury invested about $6.6 billion in preferred stock and warrants through the Troubled Asset Relief Program, created under the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act. In practice, taking TARP wasn’t really a free choice for major banks—the government wanted broad participation so no single institution looked singled out. Still, U.S. Bancorp treated it like a short-term bridge, not a crutch. By June 2009, it had fully repaid the funds, becoming the first bank to repay TARP. Internally, it was a point of pride. Externally, it sent a blunt message: this balance sheet was never on life support.

The chaos also created a fascinating near-miss. U.S. Bancorp held acquisition talks with National City, the Cleveland-based bank with meaningful operations in Florida, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—three states where U.S. Bancorp still didn’t have a retail presence. U.S. Bancorp made an offer. But PNC Financial Services used its own TARP capital to outbid them and won the deal. If U.S. Bancorp had landed National City, it would have pushed the franchise deeper into the East and South, though it also would have triggered major divestitures in overlapping Midwestern markets, especially Ohio. It’s one of those “what if” forks in the road that still invites debate: would that bigger footprint have strengthened the machine—or complicated it?

Instead of swinging for a crisis-era mega-deal, U.S. Bancorp went back to its favorite kind of opportunism: targeted, fee-heavy additions that didn’t load the balance sheet with new credit risk. In October 2009, the company acquired the mutual fund administration and accounting servicing division of Fiduciary Management, Inc., a business with about $8 billion in scope. It fit neatly into the wealth-management infrastructure, and it was the kind of move U.S. Bancorp could execute while others were still triaging their own problems.

By the end of the crisis, a reputation had hardened around U.S. Bancorp—and it has largely stuck ever since. This was the bank built by discipline. The returns in good times might not always have looked the flashiest. But in the bad times, they didn’t go negative. And over a full cycle, that kind of consistency doesn’t just survive. It compounds.

VII. The Richard Davis Era: From Regional to National (2006–2017)

Jerry Grundhofer stepped down as CEO on December 12, 2006, and Richard K. Davis took over. If Grundhofer was the builder—the dealmaker who stitched the franchise together and hardwired efficiency into the culture—Davis was the operator who had to keep that machine winning in a very different world. His job wasn’t to reinvent U.S. Bancorp. It was to refine it, deepen it, and steer it through the post-crisis decade as regulation tightened and technology started reshaping what “banking” even meant.

That meant absorbing the aftershocks of 2008 and then living under the new rules that followed. Dodd-Frank brought tougher capital standards, stress tests, and a lot more scrutiny. For a bank that took pride in running lean, compliance wasn’t just a checkbox—it was a real cost, and a real threat to the efficiency edge that had become the company’s calling card. Davis responded the only way U.S. Bancorp really knows how: invest where you must, measure everything, and keep the discipline. The bank built up its compliance infrastructure without letting the entire organization get soft.

Strategically, Davis kept leaning into the businesses that fit U.S. Bancorp’s personality: fee-heavy, scaled, and operationally demanding. Payments and wealth management were the big ones. The payments franchise, anchored by Elavon (the renamed Nova Corporation), expanded across Europe and became one of the largest payment processors in the world. The groundwork for that global push actually started earlier—back in June 2000, through a joint venture called Euroconex, which U.S. Bancorp later fully acquired. Over time, the business grew through a mix of organic investment and bolt-on acquisitions. By the Davis era, Elavon had thousands of employees across North America, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Poland, and other European countries. For a bank with a Midwestern core, it was a strikingly international footprint—and one that didn’t depend on taking big credit bets.

Davis also made a subtle but important shift in how the company presented itself. For the first time in its history, U.S. Bancorp ran a national advertising campaign focused on the brand, not a specific product. The tagline was “the power of possible.” The message was simple: this wasn’t just a strong regional bank with a great efficiency ratio. It was a national institution that wanted to be recognized as one.

But the era wasn’t spotless. In February 2018, shortly after Davis retired, the Department of Justice charged the bank with failing to implement adequate measures to prevent illegal activities, including one case involving abetting. U.S. Bancorp agreed to pay $613 million in fines and to strengthen its monitoring of customer transactions. It was a jolt—partly because the company’s reputation had been built on being the grown-up in the room. And it was a reminder of an uncomfortable truth in banking: efficiency is a competitive weapon, but it can also create pressure points if control functions don’t scale fast enough.

Even so, the core story of the Davis years is continuity. U.S. Bancorp’s operational advantage survived a CEO transition, a harsher regulatory environment, and the early waves of digital change. The efficiency ratio did drift upward—from the low 50s into the mid-50s—as compliance and technology spending rose. But it remained well below industry norms. The machine Grundhofer built didn’t just hold together under new leadership. It kept doing what it was designed to do: generate steady returns, through almost any environment.

VIII. The Andy Cecere Era: Digital Transformation and Scale (2017–2025)

In January 2017, U.S. Bancorp announced that Richard Davis would hand the CEO job to Andrew Cecere, then the bank’s president and COO. The handoff was classic U.S. Bancorp: orderly, deliberate, no drama. Davis stayed on as chairman for another year, retiring in April 2018. Cecere took the chair at that point, holding both titles.

Cecere was the ultimate insider. He’d joined the company in 1985 and spent more than three decades learning how the machine worked—then helping build it. He’d been in the room for the late-’90s and early-2000s merger sprint, and he rose through roles that force you to understand the guts of a bank: CFO, COO, operator-in-chief. If Grundhofer built the engine and Davis kept it humming, Cecere was the engineer who knew exactly which bolt to tighten, and when.

His defining challenge was obvious: digital transformation. By 2017, the threat wasn’t another regional bank down the street—it was the unbundling of banking itself. Fintechs were peeling off the best parts of the value chain—payments, consumer lending, wealth tools—and shipping them through sleek mobile apps. At the other end of the spectrum, giants like JPMorgan were spending enormous sums on technology. For a super-efficient regional bank, that created a tension: invest heavily enough to keep up, without breaking the discipline that made the model work in the first place.

Cecere leaned in. U.S. Bancorp accelerated technology investment, but tried to do it the U.S. Bancorp way: practical, measured, and tied to execution. In November 2017, the bank pulled off a small transaction with big symbolism—the first real-time payment in the U.S. banking industry using a system built by The Clearing House. A nominal amount moved between accounts at BNY Mellon and U.S. Bancorp in about three seconds, marking the first new U.S. payment clearing and settlement system in more than forty years. In other words: the “boring Midwestern bank” was the one helping inaugurate the new rail.

The broader push was less headline-friendly but more important day to day: improving mobile banking, building smoother digital account opening, and using data analytics to run the franchise better. The goal wasn’t to out-gloss fintechs. It was to make sure customers could do what they needed to do—quickly, securely, and without friction—and to make the platform strong enough to absorb whatever came next.

And what came next was Cecere’s biggest strategic swing: a major acquisition that would reshape U.S. Bancorp’s footprint. That story deserves its own chapter.

IX. The MUFG Union Bank Acquisition: Go West Strategy (2021–2023)

In September 2021, U.S. Bancorp announced what would become the largest acquisition in its history: buying MUFG Union Bank’s core regional banking franchise from Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Japan’s largest bank. The move paired two organizations to better serve customers across California, Washington, and Oregon—markets where U.S. Bancorp already had a foothold, but not the kind of scale that turns a footprint into a franchise.

The terms underscored just how serious this was. U.S. Bancorp put up $5.5 billion in cash and about 44 million shares of its own stock. When the deal closed, MUFG kept a roughly 3% stake in U.S. Bancorp—less like a clean exit, more like a vote of confidence in what the combined company could become. All in, the transaction came in around $8 billion, the biggest swing U.S. Bancorp had taken since the merger sprint of the Grundhofer era.

The strategic logic was straightforward: California is the largest U.S. banking market by deposits, and U.S. Bancorp had long been underweight there. Union Bank changed that overnight. It brought more than 300 branches, about $80 billion in deposits, and roughly 1.2 million consumer and small-business customers—concentrated in the country’s most demographically and economically important state. For a bank built in the Upper Midwest and the Pacific Northwest, this was the clearest “go west” moment in company history.

But big deals don’t just come with upside. They come with scrutiny. The regulatory review dragged on and became politically charged, with community groups and consumer advocates pressing for commitments. U.S. Bancorp responded with a five-year, $100 billion community benefits plan, with 60% directed to California. The stated goal: expand access to capital and help build wealth in low- and moderate-income communities and communities of color. In the context of bank M&A, it was enormous—one of the largest community benefit agreements tied to a merger.

The deal finally closed in December 2022, and then the real test began: integration. Cecere said the company needed a three-day holiday weekend to convert Union Bank’s systems and accounts. The conversion was initially slated for Presidents Day weekend in February 2023, but was pushed to Memorial Day weekend in May to allow more preparation. On May 26, 2023, MUFG Union Bank was merged into U.S. Bank National Association, and over the course of 2023 the systems integration was completed.

Behind the scenes, this is where the economics of the deal lived or died. U.S. Bancorp expected nearly $900 million of pre-tax cost synergies—driven by real estate consolidation, technology and systems conversion, and back-office efficiencies. About 40% to 50% of those savings were targeted for 2023, with the rest expected to show up in 2024.

By the end of 2023, Union Bank was fully inside the machine. U.S. Bancorp reported strong results from the combined franchise, with California performing ahead of initial expectations. Observers widely viewed the integration as one of the cleaner large-bank mergers of the post-crisis era—another reminder that, for U.S. Bancorp, M&A wasn’t an occasional strategy. It was a practiced capability, built over decades and still very much alive.

X. Business Model Deep Dive: The Four Pillars

By the time Union Bank was fully absorbed, U.S. Bancorp wasn’t just bigger—it was clearer. The company’s revenue engine is built on four pillars, and each one is a different way of making money, serving customers, and spreading risk. If you’re trying to understand why U.S. Bancorp has often traded at a premium to other regionals, this is the place to look.

The first—and largest—pillar is wealth, corporate, commercial, and institutional banking, which generates roughly 36.5% of revenue. This is the segment that lives with middle-market and large corporate clients: lending, treasury management, capital markets services, and wealth management. It’s also where U.S. Bancorp most directly runs into the money-center banks. But it fights with a home-field advantage that’s hard to copy: deep, local relationships in its core markets. A middle-market company in Minneapolis or Portland is far more likely to have grown up with U.S. Bank than with a New York-based giant.

The second pillar is retail banking, at about 35.5% of revenue. This is the branch network and the day-to-day financial life of households and small businesses: checking, mortgages, auto loans, and everything that comes with them. U.S. Bancorp runs more than 2,200 banking offices across the U.S., and it has long pushed a cross-selling culture designed to turn one relationship into several. The Five-Star Service Guarantee—born in the Grundhofer era—has been refreshed over time, but it’s still part of the bank’s operating DNA.

The third pillar, and the one that’s quietly made U.S. Bancorp look different from many peers, is payment services, which accounts for roughly 24% of revenue. This includes merchant acquiring through Elavon, corporate payment systems, and consumer card services. Payments is classic “good boring”: it’s operationally intense, scale-driven, and supported by a long-term tailwind as commerce keeps moving away from cash. Many banks treat payments like plumbing. U.S. Bancorp treats it like a franchise.

The fourth pillar is investment and market banking, a smaller piece at roughly 4% of revenue. Historically it hasn’t moved the overall story much, but it gained new relevance after the January 2026 announcement that U.S. Bancorp would acquire BTIG—an institutional trading and investment banking firm—for up to $1 billion. The deal was designed to add capabilities in institutional equity sales and trading, equity capital markets, and M&A advisory—areas where U.S. Bancorp had previously leaned more on referral relationships than in-house depth.

Put together, the four pillars create a revenue mix that’s unusually balanced for a bank this size. As of 2025, about 42% of U.S. Bancorp’s revenue came from fee income—well above the roughly 30% median for regional bank peers. That matters because fee businesses like payments and wealth management can cushion the blow when interest margins get squeezed. And when rates rise, the traditional banking businesses get the lift while fees keep the base steady. The result is a bank that tends to be less hostage to the rate cycle than most of its competitors—and one that can keep the machine running even when the environment changes.

XI. Competitive Analysis and Market Position

U.S. Bancorp sits in a rare spot on the banking map. It’s not a “regional” in the way most people mean it—at close to $700 billion in assets, it’s in a different weight class than banks like Regions Financial or KeyCorp. But it’s also not a true money-center giant. JPMorgan, Bank of America, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo operate at a scale—and with global reach—that U.S. Bancorp simply doesn’t try to match.

That in-between status is both the point and the risk.

On the plus side, U.S. Bancorp is big enough for real scale advantages where scale matters most: technology, compliance, and especially payments. It’s also big enough to be a serious contender for middle-market corporate relationships—clients that might be too small to command daily attention at JPMorgan, but too complex for a community bank to cover end-to-end. And while fintechs can build slick interfaces, they can’t easily replicate what a bank like U.S. Bancorp has spent decades assembling: a nationwide branch network of more than 2,200 offices and a massive deposit base, roughly $512 billion, that provides stable, low-cost funding.

But the competitive pressure comes from both directions. Above it, the money-center banks spend staggering sums on technology and can bundle in global services U.S. Bancorp doesn’t offer. Below it, fintechs keep attacking the high-growth, high-fee edges of banking—payments through Square and Stripe, lending through SoFi and LendingClub, wealth tools through Robinhood and Wealthfront. And among its true peers, the big regionals like PNC, Truist, and Citizens are fighting for many of the same households, deposits, and middle-market clients. The consolidation wave that created so much opportunity for U.S. Bancorp hasn’t ended; it’s just become a tighter, more competitive game.

Through all of that, U.S. Bancorp’s most reliable weapon is still the one it has been sharpening for decades: efficiency. With an adjusted efficiency ratio of 57.4% as of the fourth quarter of 2025, the bank turns more of each revenue dollar into profit than almost any comparable institution. That discipline gives it flexibility. It can price aggressively on loans and deposits and still earn attractive returns. And when the cycle turns and revenue gets pressured, it has more margin for error than a bank running at 65% or 70%.

Geography is the other lens that matters. The Union Bank acquisition fixed the most obvious hole by giving U.S. Bancorp real density in California. But big blank spaces remain: no retail presence in Florida, much of the Southeast, or the major Northeastern markets. Competitors like PNC and Truist have been pushing into those regions for years. Whether U.S. Bancorp tries to fill those gaps through another major acquisition—or decides that its current footprint is wide enough, and focuses on deepening relationships inside it—is one of the central strategic questions hanging over the next chapter of the story.

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

Start with the efficiency ratio. In banking, being the low-cost producer isn’t just nice to have—it’s the whole game. Most banking products are commoditized. A dollar in a checking account is a dollar in a checking account, whether it sits at U.S. Bank or JPMorgan. So the bank that can deliver the same service with fewer people, fewer layers, and fewer wasted steps turns that advantage almost directly into profit. U.S. Bancorp has kept its efficiency ratio meaningfully below peer averages for roughly three decades. That isn’t a lucky stretch of the cycle. It’s structural—baked into the culture, the operating cadence, and the way the organization is managed.

The revenue mix strengthens the story. With about 42% of revenue coming from fees—payments, wealth management, capital markets—U.S. Bancorp is less dependent on the interest-rate cycle than a traditional spread lender. And within that fee mix, payments stands out. Payment processing benefits from long-running tailwinds: commerce moving online, card and digital payments taking share from cash, and the broader digitization of how money moves. Those trends don’t require the Federal Reserve’s help.

Then there’s the West Coast move. The MUFG Union Bank acquisition finally gave U.S. Bancorp true density in California, Washington, and Oregon. California in particular is the prize: the largest state economy in the U.S., and large enough that, on its own, it would rank among the biggest economies in the world. Union Bank brought a meaningful footprint—more than 300 branches and roughly $80 billion in deposits—instantly putting U.S. Bancorp in markets where it had been present, but not dominant.

The credit culture is another part of the bull case because it’s already been stress-tested. U.S. Bancorp was the only bank among its peer group to remain profitable every quarter through the 2008–2009 financial crisis. That doesn’t mean it’s immune from losses in a downturn. But it does mean the organization has repeatedly shown it can manage risk without destroying shareholder value when the world gets ugly.

Finally, the BTIG acquisition announced in January 2026 signals a push to expand capital markets fee income while staying away from the kind of balance-sheet and trading risk that defined the blowups of 2008. BTIG adds institutional sales and trading and advisory capabilities that can plug into U.S. Bancorp’s existing corporate relationships and, if executed well, increase fee income without fundamentally changing the bank’s risk profile.

If you look at this through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, U.S. Bancorp checks several boxes. It has scale economies in payments and the compliance infrastructure required to run a systemically important bank. It benefits from switching costs—treasury management setups and payment integrations don’t get ripped out on a whim. Its brand isn’t as nationally dominant as Chase or Bank of America, but loyalty in its core markets is real. And its process power—the operational excellence discipline built over decades—is the hardest advantage of all for competitors to copy, because it’s not a feature. It’s a way of running the place.

The Bear Case

Interest-rate sensitivity still matters, even with the fee-income buffer. Net interest margin was 2.75% in late 2025, with management targeting 3% by 2027. If rates fall faster than expected, margin compression can show up quickly. And with a loan book of nearly $374 billion, small changes in spread turn into very large changes in revenue.

Regulatory scrutiny is another persistent overhang. The 2018 Department of Justice settlement tied to anti-money-laundering failures cost $613 million and dented the company’s reputation. For a bank designated as systemically important, compliance is never “done”—it’s an ongoing operating burden that pulls resources and management attention. And after the SVB-era shock, large regional banks have faced sharper scrutiny, with the always-present possibility of tighter capital rules or new requirements.

Technology is the most strategically uncomfortable risk. The money-center banks, especially JPMorgan, spend enormous sums on technology each year—amounts U.S. Bancorp simply can’t match in absolute dollars. U.S. Bancorp can invest heavily by regional-bank standards and still be outspent. If customer expectations keep shifting toward digital-first experiences, any lag in product quality, speed, or reliability can slowly weaken the branch-based relationships the franchise was built on.

Geography is improved, but not solved. The Union Bank deal filled the California gap, yet U.S. Bancorp still has no meaningful retail presence east of Ohio. That leaves major growth markets—much of the Southeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Northeast—largely untouched. It also creates exposure to regional economic softness in the Midwest and West, because the footprint isn’t fully balanced across the country.

And zooming out through Porter’s Five Forces, banking remains a knife fight. Fintech substitutes are growing, especially in unbundled services like payments and consumer financial tools. Large corporate customers have significant negotiating leverage and can shift relationships. Rivalry among incumbents is intense, especially now that consolidation has produced fewer, bigger, sharper competitors. Deposit competition swings with rate cycles. Barriers to entry are still high for full-service banking, but much lower for individual slices of the value chain.

The KPIs That Matter Most

If you only tracked two numbers to understand whether the U.S. Bancorp machine is getting stronger or weaker, they’d be these.

First: the efficiency ratio, the share of revenue consumed by non-interest expense. It’s the clearest single expression of U.S. Bancorp’s identity. When it improves, the operating system is doing what it’s designed to do. When it worsens, something is off—either revenue isn’t coming through as expected, or costs are starting to creep.

Second: fee income as a percentage of total revenue. This is the cleanest read on diversification and on whether the bank is gaining more weight in businesses like payments and wealth management that don’t live and die by net interest margin. Over time, a healthy, rising fee mix is a sign that U.S. Bancorp is building a franchise that can keep compounding through different rate environments.

XIII. Lessons and Playbook

The U.S. Bancorp story offers a handful of lessons that travel well beyond banking.

First: operational excellence beats growth for growth’s sake. Jerry Grundhofer didn’t set out to build the biggest bank in America. He set out to build the most efficient one—and that difference shaped everything. Companies that worship size often destroy value: they overpay for acquisitions, charge into markets where they don’t have an edge, or take on risks they don’t fully understand. Grundhofer’s obsession with the efficiency ratio forced discipline at every level. The bank did grow—dramatically, even roughly eightfold early on—but that growth was the output of a system, not the goal of the company.

Second: leadership chemistry matters more than most deal models admit. Family businesses are common, but it’s almost unheard of for two siblings to independently become CEOs of major banks and then merge them. The Firstar–U.S. Bancorp combination worked in part because Jerry and Jack Grundhofer brought something you can’t buy with consultants: decades of shared context and mutual trust. The lesson isn’t “merge with your brother.” It’s that the relationship between the people doing the merging is a real variable in whether integration becomes a trench war or a clean build.

Third: timing in M&A is a competitive advantage. Analysts hated Grundhofer’s habit of lining up the next acquisition before the last one felt fully digested. The conventional playbook says: pause, integrate, stabilize, then move. Grundhofer believed that in a consolidating industry, the best assets show up on their own schedule. If you wait until it’s comfortable, the deal is gone. But there’s a catch: rapid-fire M&A only works if you have a repeatable integration machine. U.S. Bancorp did—and that was the difference between bold and reckless.

Fourth: you can build a sales culture in places that don’t think of themselves as “sales.” Banks, hospitals, universities, government agencies—some of the biggest institutions in the economy were designed to be passive. People come to you; you serve them. Grundhofer flipped that assumption. Even in banking, where products often look like commodities, a real sales and service discipline can compound into an edge. The Five-Star Service Guarantee wasn’t just marketing. It was an operating system: expectations, measurement, accountability, and a shared language for how the frontline should behave.

And finally: boring banking can be beautiful. In an era when financial institutions chase headlines—crypto ventures, metaverse strategies, splashy fintech partnerships—U.S. Bancorp’s playbook has been almost aggressively unglamorous. Lend prudently. Build fee businesses like payments. Cross-sell with discipline. Run the cost base like it’s your job—because it is. Over decades, that kind of consistency can produce something rare in finance: performance you can count on.

XIV. Epilogue: The Future of Regional Banking

In April 2025, U.S. Bancorp named Gunjan Kedia as its next CEO—the first woman to lead the company in its roughly 160-year history. Born in Delhi, India, Kedia brought an engineering degree from Delhi Technological University, an MBA from Carnegie Mellon’s Tepper School of Business, and nearly three decades of experience across PricewaterhouseCoopers, McKinsey, Bank of New York Mellon, State Street, and U.S. Bancorp itself. At U.S. Bancorp, she had served as vice chair of the wealth, corporate, commercial, and institutional banking division since 2016. Andy Cecere moved into the role of executive chairman.

Her appointment wasn’t just a milestone. It was also a signal about what the next era of banking demands. The industry was already consolidating, but the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in March 2023 poured gasoline on the trend. Regulators tightened, markets got less forgiving, and suddenly “small” looked like a risk factor. The survivors got bigger. The rulebook got thicker. For U.S. Bancorp—too large to hide, but not a money-center behemoth—the strategic question sharpened: stay a super-regional with national capabilities, or push toward true national scale.

The BTIG acquisition, announced in January 2026 for up to $1 billion, offered an early clue about how that question might be answered. Instead of chasing another giant bank merger, U.S. Bancorp went after capabilities: institutional equity sales and trading, equity capital markets, and M&A advisory—tools that could plug into its existing corporate relationships. BTIG’s more than 700 employees across 20 global offices represented years of buildout in one move. It was a very post-MUFG kind of bet: assume the branch footprint is largely set, and make growth about earning more per relationship rather than simply adding more relationships.

Heading into 2026, the underlying performance suggested the machine was still doing what it was built to do. Fourth-quarter 2025 earnings per share came in at $1.26, up 18% year over year on an adjusted basis. Full-year net revenues reached a record $28.7 billion. Fee income grew 8%. The bank posted positive operating leverage for the sixth straight quarter. And management guided to 4% to 6% revenue growth in 2026, with positive operating leverage of more than 200 basis points.

But the next decade won’t be decided by whether U.S. Bancorp can keep doing what it has always done. It will be decided by whether that operating playbook—built by Jerry Grundhofer in the 1990s, refined under Richard Davis and Andy Cecere, and now handed to Kedia—can keep working as banking gets rewired in real time. Real-time payments, embedded finance, artificial intelligence, and a generation of customers who may never visit a branch change the field of play. The efficiency ratio will still matter. The cross-selling culture will still matter. What has to change is the delivery system: the channels customers live in, the data and risk controls beneath them, and the technology foundation that has to move faster than a bank’s culture naturally wants to.

U.S. Bancorp has made a habit of proving doubters wrong with quiet, disciplined execution. From a loose confederation of Midwestern banks to a nearly $700-billion institution with national reach, it has shown—again and again—that operational excellence, relentlessly applied, is a compounding advantage. Whether that same advantage is enough in an AI-shaped financial system is the question that defines the next chapter.

XV. Recent News

U.S. Bancorp reported fourth-quarter 2025 results on January 20, 2026. Earnings per share came in at $1.26, and the company posted record net revenues—$7.4 billion for the quarter and $28.7 billion for the full year. CEO Gunjan Kedia pointed to the same themes that have defined the franchise for decades: fee income up 8% year over year, positive operating leverage for the sixth straight quarter, and an adjusted efficiency ratio of 57.4%.

A week earlier, on January 13, 2026, U.S. Bancorp announced a definitive agreement to acquire BTIG, LLC for up to $1 billion. The target purchase price at closing is $725 million, split between $362.5 million in cash and about 6.6 million shares of U.S. Bancorp stock, with the potential for up to another $275 million in cash over three years if BTIG hits performance targets. The company expected the deal to close in the second quarter of 2026.

Management’s 2026 outlook stayed consistent with the bank’s “steady compounding” identity: total revenue growth of 4% to 6%, positive operating leverage of more than 200 basis points, and loan growth of 3% to 4%, while continuing to work toward a 3% net interest margin target by 2027. Commercial loans and credit cards were expected to be the main engines of that loan growth.

The leadership transition continued too. Andy Cecere, CEO from 2017 to 2025, moved into the executive chairman role when Gunjan Kedia became CEO in April 2025. The company expected Cecere to retire as chairman, with Kedia slated to take over the chair role as well.

As of late January 2026, U.S. Bancorp shares traded near $56, implying a market cap of about $87 billion. The stock traded at roughly 12 times trailing earnings and yielded about 3.7% in dividends.

XVI. Links and Resources

Company filings and investor presentations are available on the U.S. Bancorp investor relations site. Much of the historical context on the Grundhofer era comes from banking industry coverage at the time, along with SEC filings from the late 1990s and early 2000s. Details on the MUFG Union Bank acquisition are documented in U.S. Bancorp’s December 2022 closing announcement and the quarterly filings that followed. The BTIG acquisition terms are laid out in the January 13, 2026 press release. Gunjan Kedia’s biographical information is available through U.S. Bancorp’s corporate governance disclosures and Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music