IDEXX Laboratories: The Unlikely King of Animal Diagnostics

Introduction and Episode Roadmap

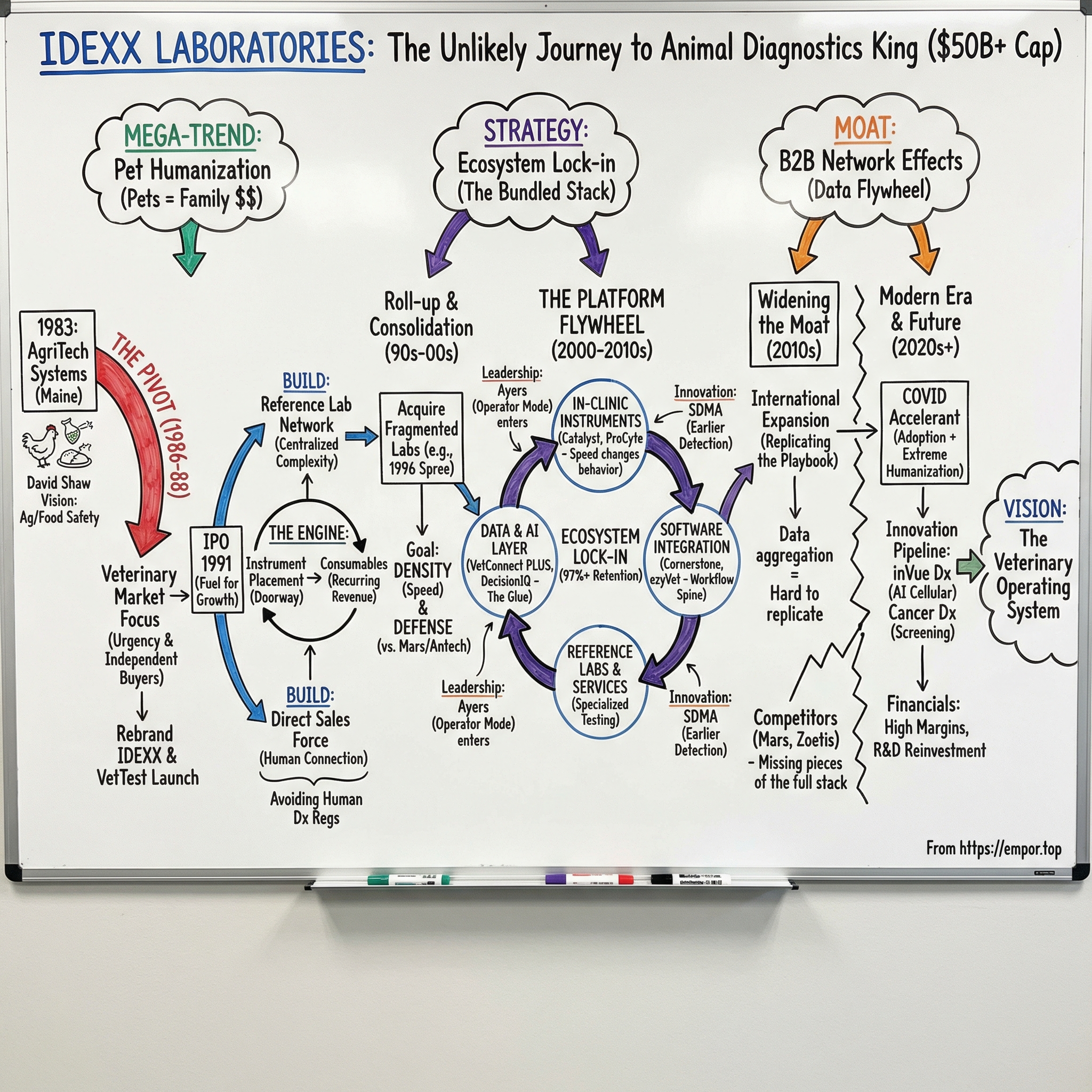

In Westbrook, Maine, a town of roughly 20,000 people along the Presumpscot River, there’s a corporate headquarters that doesn’t look like the command center of a global powerhouse. But it is. IDEXX Laboratories is one of the most dominant franchises in American healthcare, even though most people outside the veterinary world couldn’t pick the name out of a lineup.

Today, IDEXX carries a market capitalization north of $50 billion. It controls an estimated 60 to 65 percent of the North American in-clinic veterinary diagnostics market. And it keeps customers at a rate above 97 percent. Wall Street once wrote off veterinary diagnostics as too small, too fragmented, too niche. IDEXX turned that “niche” into a near-fortress.

The central question is simple: how did a company founded in 1983 by a 30-year-old management consultant from Maine—initially focused on agricultural testing, like detecting disease in poultry—become the indispensable backbone of modern veterinary medicine?

The answer isn’t one magic product. It’s a sequence of compounding moves: a crucial early pivot toward veterinary, a razor-and-razorblade model executed with unusual discipline, a roll-up of a fragmented industry through acquisitions, and then the real ace—an ecosystem that ties together instruments, consumables, software, and reference lab services so tightly that leaving feels like ripping out a clinic’s entire operating system.

Three themes drive everything that follows.

First, network effects in B2B healthcare: IDEXX built tools and data platforms that get more valuable as more clinics use them, creating a flywheel competitors struggle to match.

Second, the pet humanization megatrend: over time, pet owners have increasingly treated animals like family, spending more on preventive care, diagnostics, and treatment than any generation before.

Third, ecosystem lock-in: the deliberate bundling of hardware, tests, software, and services into one integrated stack—high switching costs disguised as convenience.

What makes IDEXX such a great business story is how quietly it happened. No magazine-cover charisma. No viral product moment. While Silicon Valley chased social media and cloud computing, IDEXX was putting blood chemistry analyzers into clinics in Des Moines and Düsseldorf, building a franchise now worth more than plenty of companies that got all the attention. From five employees in a small Portland, Maine office in 1983 to a $50 billion-plus market cap by 2026, it became one of the great American compounders—by helping veterinarians answer a simple, urgent question: what’s wrong with this animal?

This is the story of IDEXX Laboratories: the agricultural biotech startup that, almost unnoticed, became the most important name in animal diagnostics.

Origins: The David Shaw Vision and Early Pivot (1983-1990)

In the early 1980s, David Evans Shaw was living the kind of week that wears people down fast. He’d just turned thirty, and he was commuting from Maine to Massachusetts, week after week, to work at Agribusiness Associates—a consulting firm operating right at the crossroads of agriculture and biotechnology. Before that, Shaw had served in the Maine State Executive Department, and he’d helped build a leading food and agribusiness consulting practice alongside Professor Ray A. Goldberg at Harvard Business School.

It was a perfect perch for what came next, because the biotech revolution was just starting to feel inevitable. Genentech had gone public in 1980. Amgen was incorporated that same year. Capital was rushing toward anything that sounded like “biology + technology,” and the big idea was straightforward: diagnostics were going to move out of slow, centralized labs and into faster, more practical, real-world applications.

Shaw wasn’t a lab-coat founder. He was a market person. He looked at agriculture—the supply chains, the safety risks, the inefficiencies—and saw diagnostics as an enormous opportunity hiding in plain sight. As he later put it, he saw “opportunities in animal health that were not being served well.” He also didn’t love the commute, and he did love living in Maine. So rather than go chase the biotech gold rush from Boston or the Bay Area, he decided to build from home—and to start with poultry, a segment that required less upfront capital and offered a quicker path to market than many other parts of agriculture.

The need was real and immediate. Farmers needed to test milk for antibiotic contamination. Food processors needed rapid assays for pathogens. Regulators needed better tools to keep food safe. The existing options were slow and expensive, and often meant shipping samples off to distant labs and waiting days for answers.

In 1983, Shaw incorporated AgriTech Systems in Portland’s Old Port neighborhood. The company started with just five employees. The thesis was narrow, practical, and very “Maine”: build rapid, affordable tests that could detect contaminants and disease in food and agricultural products using the emerging tools of immunodiagnostics. By 1985, AgriTech had its first commercial products—systems government agencies and food businesses could use to test for contaminants in foods. Not glamorous, but useful. And crucially, they worked.

Then, in 1986, the move that changed everything began to take shape. The company started selling diagnostic and detection products for use by veterinarians in their own offices.

This wasn’t a single lightning-bolt moment. It was more like Shaw and the team noticing something obvious in retrospect: if you could build immunodiagnostic tests for agriculture, you could adapt the same underlying technology for clinical use. The science foundation held. What changed was the customer—and the economics.

Agricultural diagnostics could be huge, but it was also fragmented, price-sensitive, and heavily shaped by government procurement cycles. Veterinary medicine was different. It was thousands of independent, doctor-run small businesses making quick decisions. A vet didn’t have time for a drawn-out purchasing process. A dog was sick. An owner wanted answers. The clinic needed results now, not next week after a lab shipment and a backlog. That difference in urgency—and in who controlled the buying decision—turned out to matter a lot.

In 1988, AgriTech Systems became IDEXX Laboratories, a name derived from IDX, shorthand for immunodiagnostics. That same year, the company developed the VetTest Chemistry Analyzer, a product that pushed diagnostics directly into the clinic by letting veterinarians run blood chemistry panels on-site. The rebrand and the product launch weren’t just cosmetic progress. They were the company tipping its hand: veterinary diagnostics wasn’t going to be a side hustle. It was the future.

What made the pivot so powerful wasn’t only the size of the market. It was the relationship it created. In agriculture, IDEXX was effectively selling a testing capability—valuable, but closer to a commodity. In veterinary medicine, it was inserting itself into clinical decision-making. When a clinic used an IDEXX diagnostic to evaluate kidney disease or detect heartworm, it wasn’t just buying a kit. It was training staff, building routines, learning an instrument, and developing trust in the results. Each test run was small. Together, they created workflow dependence—lock-in that didn’t feel like lock-in, because it arrived disguised as speed and reliability.

By the end of the 1980s, IDEXX was still a small company by any normal standard. It faced competition from established players that had been selling into veterinary practices for decades. But Shaw had already put a much bigger idea into motion: a technology company could own the diagnostic workflow in veterinary medicine. The next question was whether IDEXX could scale fast enough to make that vision inevitable—before the rest of the industry fully understood what was happening.

Building the Foundation: Reference Labs and Distribution (1990s)

On June 21, 1991, IDEXX went public on NASDAQ. For a company not even a decade old, the IPO was less about optics and more about fuel. Shaw wanted capital to do two hard things at the same time: build a national network of reference laboratories and build a direct sales force that could walk into vet clinics everywhere. Those bets weren’t glamorous, but they became the load-bearing beams of the IDEXX empire.

The reference lab push was the real infrastructure play. In-clinic tests were great for fast answers, but a clinic can’t do everything on a countertop machine. Biopsies, advanced bloodwork, specialized pathology, and more esoteric panels require expensive equipment, tight quality control, and highly trained people—investments no single practice could justify. Reference labs solved that by centralizing the complexity: clinics shipped samples out and got results back quickly, often the same day, without building a lab inside the practice.

Of course, “just build labs” is easy to say and brutal to execute. Each location needed veterinary pathologists and technicians, sophisticated instrumentation, and dependable logistics to handle thousands of incoming samples and deliver consistent results. IDEXX wasn’t the first to offer veterinary reference testing, but it approached the business like a technology company. Results would move electronically, not by slow, error-prone processes. Turnaround times would be tight. And over time, reference lab data would connect with in-clinic diagnostics to form a more complete medical record—something single-product competitors couldn’t replicate.

This is also where IDEXX’s focus became clearer: veterinary, not human. That choice wasn’t obvious in the early ’90s. Human diagnostics was a much bigger market, and a lot of biotech companies naturally drifted toward the biggest prize. But the structure of human diagnostics was punishing. Huge incumbents like Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp had scale and relationships that were hard to dislodge. Pricing was shaped by insurers and government payers. Regulatory pathways could be long and expensive.

Veterinary diagnostics was the opposite. The vet was the clinician and the buyer. There was no insurer between the recommendation and the purchase. Pet owners generally paid out of pocket, and the vet could decide what to run based on medical judgment and what the owner would approve. Regulatory barriers were lower than in human testing, and the market was made up of thousands of independent practices—exactly the kind of landscape where a focused company could build direct relationships and steadily take share.

By the mid-1990s, IDEXX also broadened its reach with water testing. In 1993, it introduced products that helped government agencies and businesses detect contaminants in drinking water. It was a logical extension of the same immunodiagnostic capabilities—useful diversification, and proof that the underlying platform traveled well—even if it never rivaled the scale or profitability of the companion animal business.

Underneath all of this, you can see IDEXX’s economic model starting to click into place. The company sold everything from relatively inexpensive tests to much more complex, higher-priced panels. It also sold instruments that could represent a major purchase for a clinic. That mix mattered, because it set up the flywheel IDEXX would perfect later: get instruments into clinics, then earn recurring revenue as those instruments consumed a steady stream of tests and reagents. The one-time placement opened the door; the consumables kept the relationship paying.

The other half of the foundation was distribution—specifically, IDEXX building its own direct sales force instead of leaning on third-party distributors. It was costly, but it created something competitors couldn’t buy off the shelf: a tight, human connection to the customer. IDEXX reps weren’t just taking orders. They could speak the language of the clinic, walk through diagnostic protocols, and show how better testing could improve both patient care and the practice’s economics. Over time, those relationships became their own moat. Trust doesn’t come from a catalog.

The Acquisition Spree: Roll-up Strategy (1996-2000s)

By the mid-1990s, IDEXX had a working engine: products that clinics actually used, a growing reference lab footprint, and a sales force building real relationships. But David Shaw and his team could see what everyone else could see, too: veterinary diagnostics was still wildly fragmented. That fragmentation wasn’t just a market condition. It was an opportunity.

So IDEXX stopped playing only offense through product innovation and started playing offense through consolidation. What followed became one of the more disciplined roll-ups in healthcare—less about flashy deals and more about stitching together a network that would be harder and harder to compete with.

1996 was the inflection point. In one year, IDEXX acquired six companies: Vetlab, Inc., Grange Laboratories Ltd., Veterinary Services, Inc., Consolidated Veterinary Diagnostics, Inc., Ubitech Aktiebolag, and Idetek, Inc. The strategy wasn’t “buy whatever’s available.” Each deal filled a specific gap. Vetlab and Consolidated Veterinary Diagnostics added reference lab capacity in important geographies. Grange Laboratories helped extend reach internationally. Ubitech, based in Sweden, strengthened European distribution. Idetek brought complementary diagnostic technology.

Taken together, those six acquisitions weren’t random. They were a coordinated campaign to expand coverage, deepen capabilities, and pull more of the market into the IDEXX orbit.

And IDEXX didn’t let up in 1997. The company kept acquiring competitors, and the cumulative effect of 1996 and 1997 was bigger than simple revenue growth. IDEXX was removing independent players from the board, absorbing their customer relationships, and turning their lab capacity into nodes inside the broader IDEXX system. Every acquired lab could plug into the company’s increasingly electronic, increasingly standardized way of moving results back to clinics.

Of course, the hard part of a roll-up isn’t signing the purchase agreement. It’s making the whole thing work afterward. Buying six companies in a year is difficult for any organization; for IDEXX at the time, it was a high-wire act. Labs came with different quality standards, different systems, different cultures, and different ways of serving customers. Integrating them into one coherent network took management focus and real capital. Some businesses folded in quickly. Others took years to fully contribute. IDEXX learned, the painful way, the difference between acquiring businesses and actually integrating them.

Still, the underlying logic was powerful: density. In reference lab services, geography is destiny. Clinics want samples to arrive quickly and results to return the same day or overnight. Each additional lab reduced shipping time for nearby practices, improved service, and made IDEXX more compelling compared to rivals with fewer locations. More labs meant faster results. Faster results meant happier clinics. Happier clinics meant higher retention. Higher retention meant more volume, more cash, and more ability to expand. The flywheel didn’t just spin—it accelerated.

The roll-up also served a defensive purpose. By buying regional labs, IDEXX made it harder for competitors to assemble comparable networks through the same consolidation playbook. The most significant rival taking a similar path was Mars, Inc., via its Antech Diagnostics subsidiary. The scramble for independent veterinary reference labs in this era wasn’t subtle; it felt like a land grab. Every lab IDEXX bought was one Antech couldn’t.

Then came a leadership transition. In 2002, Shaw stepped down as CEO and Chairman, handing the reins to Jonathan Ayers. The founder era ended, but the architecture Shaw left behind—reference labs, direct distribution, in-clinic instruments, and a steadily more integrated technology platform—proved durable. Shaw stayed active in the world he helped build, later establishing Black Point Group as an investment vehicle and co-founding Covetrus, another company at the intersection of technology and animal health.

Fast forward to June 2021, and the M&A playbook shows how much IDEXX’s strategy had evolved. IDEXX acquired ezyVet, a cloud-based practice management software platform founded in 2006 in New Zealand by Hadleigh Bognuda. This deal wasn’t notable because it was huge. It was notable because it was strategic. IDEXX’s Cornerstone software was powerful, but it was built for an earlier era: server-based, installed, and deeply embedded. ezyVet offered a modern, cloud-native alternative for newer, tech-forward practices that wanted cloud tools from day one. The deal also brought Vet Radar, a mobile-responsive electronic treatment sheet and whiteboarding solution.

With ezyVet, IDEXX wasn’t just buying a software product. It was broadening its claim on the clinic’s workflow—from general practices to specialty clinics to university hospitals—and reinforcing the same core idea that had driven the roll-up decades earlier: the more of the veterinary practice you can support, the harder you are to replace.

The Platform Play: In-Clinic Diagnostics Revolution (2000-2010)

Picture a veterinary clinic in suburban America around the year 2000. A golden retriever named Max comes in with his worried owner: he’s lethargic, he’s been drinking water nonstop, and something is clearly off. The vet suspects kidney disease, but suspicion isn’t a treatment plan. The vet needs bloodwork.

In the old model, that meant drawing blood, packaging it up, and shipping it to a reference lab. Then everyone waited. A day, maybe two. The owner went home anxious. The vet moved on to the next appointment. And Max’s treatment didn’t really start until the results came back. It was modern medicine, throttled by logistics.

IDEXX rewired that experience by pushing serious diagnostics directly onto the clinic counter. The Catalyst chemistry analyzer—developed and refined throughout the 2000s—could run a full blood chemistry panel in minutes. The vet drew blood, loaded a sample, ran the test, and had results during the same visit. Max’s kidney values weren’t a phone call tomorrow. They were on the screen right now, while the owner was still in the exam room. The conversation changed from “we’ll call you” to “here’s what’s happening, and here’s what we’re going to do next.”

That speed wasn’t just a nicer customer experience. It changed behavior. When answers arrive in minutes instead of days, vets test more often. They test earlier. They start running diagnostics as part of routine wellness visits, building baselines and catching disease before it turns into an emergency. In other words: IDEXX didn’t just take share from reference labs. It expanded the entire pie by making diagnostics something you do proactively, not just when things go wrong.

Under Jonathan Ayers, who took over as CEO in 2002, IDEXX leaned hard into this shift. Shaw had built the early foundation—products, labs, distribution, a strategic north star. Ayers brought the operator’s instinct for compounding: invest more in R&D, get more instruments placed, and make sure those instruments didn’t live as standalone devices, but as nodes in a broader system. Over that decade, IDEXX started to look less like a diagnostics vendor and more like the platform that diagnostic workflows ran on.

The menu kept filling out. The ProCyte Dx Hematology Analyzer brought complete blood counts into the clinic, not just chemistry. A CBC gives vets visibility into red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets—clues that can point to anemia, infection, inflammation, and even cancers. With chemistry from Catalyst and hematology from ProCyte running side by side, a general practice could deliver a level of diagnostic clarity that used to require sending samples out.

IDEXX also made sure it had coverage for different kinds of practices. The VetTest Chemistry Analyzer offered a smaller footprint option for clinics that didn’t need the full Catalyst capability, letting IDEXX serve everything from high-volume hospitals to smaller general practices without leaving an opening for competitors to wedge in.

Then the business model kicked in. An analyzer isn’t a one-time sale; it’s the doorway. Once an instrument is installed, every test requires proprietary consumables—slides, reagents, kits. A reasonably busy clinic can run enough panels that the consumables quickly dwarf the upfront economics of the machine itself. Multiply that across thousands of clinics, and you don’t just get revenue—you get a recurring stream that’s predictable, resilient, and naturally grows as the standard of care rises and testing becomes more routine.

IDEXX often made the upfront decision easier, too. Clinics could buy instruments outright, but IDEXX also used lease and reagent-rental style programs—low or even no upfront cost, in exchange for a commitment to buy consumables. To a clinic, it felt like getting capabilities now and paying as you use them. To IDEXX, it was a long-lived annuity with extremely attractive economics.

And once a practice ran its workflow on IDEXX, switching wasn’t a casual decision. It wasn’t just swapping a machine. It meant retraining technicians, changing established protocols, adjusting to different test menus and reference ranges, and living through a period of friction and inefficiency. In a busy clinic, that pain is real. For most, it was far easier to stay with the system that already worked.

Software made that stickiness even stronger. IDEXX’s Cornerstone practice management software handled the operational spine of a clinic—appointments, medical records, billing, inventory—and it integrated tightly with IDEXX instruments. Results flowed directly into the patient record without retyping or manual entry. Over time, Cornerstone grew to serve more than 125,000 veterinary professionals and expanded into features like appointment reminders, a pet owner app called Vello, and integrated payment processing that reduced administrative hassle at checkout.

By the end of the 2000s, IDEXX had built something more cohesive than a great set of machines. Instruments, consumables, software, and reference labs all reinforced each other. Each piece made the others more valuable. And the more a clinic depended on the whole stack, the harder it became to displace any one part of it.

This was ecosystem strategy before “ecosystem” became a cliché—and IDEXX was executing it in a corner of healthcare most people still underestimated.

And importantly, this platform didn’t just make testing faster. It created the conditions for new kinds of tests to matter. In 2015, IDEXX introduced SDMA at its reference laboratories, a kidney biomarker that became one of the company’s most meaningful innovations. For years, veterinarians had relied heavily on creatinine to assess kidney function, but creatinine typically didn’t rise above normal until a pet had already lost about three-quarters of kidney function. SDMA—symmetric dimethylarginine—started rising when only about a quarter of kidney function had been lost. It gave vets a much earlier warning signal, and unlike creatinine, it wasn’t skewed by a pet’s muscle mass. Studies showed SDMA helped identify additional cases of early kidney disease—especially in cats—where creatinine alone would have missed it.

In other words, IDEXX wasn’t just selling speed. It was selling earlier answers. And earlier answers pull more diagnostics into everyday care—which sends even more volume through the platform IDEXX had spent the decade building.

The Moat Widens: Network Effects and Lock-in (2010-2020)

If the 2000s were when IDEXX built the platform, the 2010s were when that platform hardened into a moat.

By this point, IDEXX wasn’t just winning deals. It was keeping customers at a rate above 97 percent. In any business, that’s elite. In a world of independent veterinary practices—where nobody is forced into a long-term contract, and switching is always technically possible—it’s a flashing sign that IDEXX had become part of the clinic’s muscle memory. Leaving wasn’t just inconvenient. It meant ripping out workflow.

A big reason was VetConnect PLUS, one of the most important evolutions in IDEXX’s strategy. VetConnect PLUS was a cloud portal that pulled results from IDEXX in-clinic instruments and IDEXX reference labs into one searchable patient record. A vet could open a case and see the full story: bloodwork from years ago, last month’s urinalysis, today’s chemistry panel—plus trend lines showing what was changing and how fast.

On the surface, that sounds like “better software.” In practice, it created something much closer to network effects.

Every result that flowed into the system made the system more useful. Longitudinal data turned one-off numbers into patterns. A slight drift in kidney values, a recurring inflammatory marker, a trend that would be easy to miss in a folder of PDFs—VetConnect could make it visible. And at scale, aggregated, anonymized data gave IDEXX statistical power that smaller competitors simply couldn’t match. Better data improved interpretive tools, which made the platform more valuable, which encouraged more usage, which generated more data. It’s a flywheel that looks obvious after the fact and brutal to replicate from scratch.

Over time, VetConnect PLUS added DecisionIQ, an AI-powered feature that offered interpretive support and suggested clinical considerations alongside results. It drew on IDEXX’s own massive dataset and incorporated input from IDEXX’s board-certified pathologists. The pitch wasn’t “replace the veterinarian.” It was “help the veterinarian catch what’s easy to miss when you’re moving fast.”

And it fit the way vets actually work. VetConnect PLUS was available on mobile, so a doctor could check results from home late at night, swipe through historical trends, and share client-friendly summaries with pet owners. Two-way integration with practice management systems cut out retyping and manual entry—the kind of small friction that silently eats time and introduces errors. This wasn’t just a results portal. It was a diagnostic workflow layer sitting on top of everything IDEXX had already placed in the clinic.

Meanwhile, competitors weren’t asleep. If anything, the 2010s clarified who the real challengers were.

Mars, through Antech Diagnostics, was the biggest rival in reference labs, backed by the resources of one of the world’s largest private companies. Mars also owned veterinary hospitals through VCA Animal Hospitals and Banfield Pet Hospital, giving it a built-in base of clinics that could send volume through its system. Zoetis, spun out of Pfizer in 2013, had deep veterinary relationships through pharmaceuticals and the scale to invest heavily if it chose to. Heska, much smaller, competed in point-of-care instruments, often with compelling pricing.

But each competitor was missing key pieces.

Mars and Antech had scale in reference labs, but they didn’t match IDEXX’s breadth in in-clinic instruments and practice management software. Zoetis had relationships and distribution, but it was late to diagnostics and didn’t have the installed instrument base that drives recurring consumables. Heska had credible in-clinic products, but it couldn’t replicate IDEXX’s lab network or software platform. Everyone had part of the puzzle. IDEXX had the full picture—and, more importantly, had already fit the pieces together.

It’s worth noting that the competitive story doesn’t end neatly in 2020. In 2023, Mars made the boldest move yet by acquiring Heska for about $1.3 billion. Strategically, the intent was clear: combine Heska’s in-clinic instrumentation with Antech’s reference labs, plus Mars’s ownership footprint across VCA and Banfield, and its European presence through Synlab Vet. It created the most credible integrated challenger IDEXX had faced.

The logic is compelling: Mars can own the testing infrastructure and, through its hospitals, influence the ordering behavior. In theory, that means captive volume, bundling power, and the ability to build a data layer that competes with VetConnect PLUS.

The catch is integration. Stitching together Antech, Heska, VCA, Banfield, and Synlab into a coherent operating system—across different technologies, cultures, and management structures—is enormously difficult. Mars is private, so the numbers aren’t publicly reported, but the organizational challenge is real. IDEXX built its ecosystem over decades, with compatibility and workflow in mind from the start. Mars was trying to assemble one through acquisition on a much faster clock. That can work, but it’s rarely smooth.

While the battle lines sharpened in North America, IDEXX also pushed outward. The 2010s were when international expansion became more systematic: build or acquire reference lab capacity, deploy a direct sales force, place instruments, then wrap it all in software and data infrastructure.

International growth mattered because diagnostic utilization outside the U.S. tended to be lower. In many countries, vets leaned more heavily on physical exams and clinical judgment—not because they didn’t value data, but because fast, convenient diagnostics weren’t as accessible, and the workflow change hadn’t yet become standard practice. IDEXX’s playbook—instrument placement, training, and showing both clinical and economic benefits—didn’t just take share. It helped create the habit of routine testing.

By the end of the decade, IDEXX operated more than 70 reference laboratories worldwide, sold into over 175 countries, and employed roughly 11,000 people. International business made up about 35 percent of revenue, with major markets including Germany, the U.K., France, Australia, and Japan. The shape of the business reflected deliberate expansion: the U.S. still drove most revenue, but the rest of the world was no longer a side quest—it was a compounding engine.

And the long runway was obvious. In the U.S., routine in-clinic diagnostics had become part of standard care—chemistry panels, CBCs, add-on screens. In many European and Asian markets, that level of routine testing still wasn’t universal. The reasons varied: pet owner expectations, clinical training norms, instrument availability, and cost sensitivity. But the gap itself was the opportunity. Closing it would take time, local execution, and sustained investment—exactly the kind of slow, methodical work IDEXX had shown it was willing to do.

Modern Era: AI, Innovation, and Market Domination (2020-Today)

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted nearly every industry on the planet. For IDEXX, it acted less like a shock and more like an accelerant.

As millions of people started working from home, pet adoption surged. Shelters reported record-low inventory. Breeders built waiting lists months long. The American Pet Products Association estimated that U.S. pet ownership rose from roughly 67 percent of households to over 70 percent during the pandemic years. More pets meant more vet visits. More vet visits meant more diagnostics. And more diagnostics meant more volume flowing through IDEXX’s installed base of instruments and reference laboratories.

But the real tailwind wasn’t just more animals. It was how owners behaved.

The pet humanization trend shifted into a higher gear. Owners increasingly wanted “human-grade” medicine for their animals: annual bloodwork, preventive screening, specialty referrals, and advanced imaging. The mindset moved from “go when something is obviously wrong” to “monitor, screen, and catch it early.” That change matters enormously for IDEXX because preventive and wellness testing tends to be both more frequent and stickier than one-off, acute diagnostics.

You can see the result in the financial profile. IDEXX’s 2024 revenue reached $3.898 billion, with gross margins at 61 percent and operating margins at 29 percent. That margin structure looks unusually strong for a company that sells physical instruments, and the reason is classic IDEXX: it designs the instruments and the consumables, manufactures at scale, and sells through its own direct sales force. It keeps the distributor margin for itself. The cash that throws off gets recycled into more R&D and returned to shareholders through buybacks.

The momentum carried into 2025. By the third quarter, IDEXX reported revenue of $1.105 billion, up 13 percent, with 12 percent organic growth. Operating margins expanded to 32.1 percent, up 100 basis points year over year—evidence that growth wasn’t being “bought” by sacrificing profitability. Companion Animal Group Diagnostics recurring revenues grew more than 10 percent organically, with international growth running ahead of the more mature U.S. market. IDEXX also raised its full-year 2025 earnings guidance to $12.81 to $13.01 per share. By this point, the Companion Animal Group made up about 92 percent of total revenue—less “concentration risk” than a signal that IDEXX had found the best pocket of animal health and built a machine around it.

The machine runs on innovation, too. IDEXX invested nearly 7.5 percent of revenue in R&D, and that spend wasn’t producing only incremental upgrades. The most significant launch in years was the IDEXX inVue Dx Cellular Analyzer, announced in January 2024 and shipping globally by late 2024.

To understand why inVue Dx matters, it helps to remember what “cellular analysis” used to look like in a typical clinic. A technician draws blood, makes a smear on a glass slide, stains it, puts it under a microscope, and then manually identifies and counts cell types. It takes time. It takes skill. And results can vary depending on technique and experience.

inVue Dx aimed to remove the slide—and much of the manual burden—entirely. Using advanced optics and AI trained by IDEXX board-certified pathologists on more than ten million images, the instrument analyzed cells directly from a blood sample in about ten minutes. IDEXX positioned the output as reference-laboratory quality at the point of care, including three-dimensional cell assessment and high-contrast images of cellular features that aren’t visible under a traditional microscope. The first applications were blood morphology and ear cytology, with fine needle aspirates for “lumps and bumps” planned for later expansion. By the second quarter of 2025, IDEXX had placed nearly 2,400 inVue Dx units—an early sign that it wasn’t just replacing an old workflow, but expanding a category many general practices had either outsourced or avoided altogether.

Then came an announcement that could be even bigger over the long run. In January 2025, IDEXX introduced IDEXX Cancer Dx: a diagnostic panel designed for early detection of canine lymphoma via a routine blood test.

The backdrop here is grim but common. Lymphoma is one of the most frequent cancers in dogs. Often, by the time owners notice signs—swollen lymph nodes, lethargy, weight loss—the disease is already advanced, narrowing treatment options. A screening test that can flag risk months earlier changes the timing of the conversation: earlier intervention, more informed decisions, and potentially better outcomes.

IDEXX priced the test at $15, explicitly positioning it as something that could fit into standard wellness screening rather than a costly add-on. IDEXX said it could detect lymphoma six to eight months before clinical signs appeared, with a 79.3 percent detection rate and 98.9 percent specificity. That specificity is the key to making broad screening feasible: it keeps false positives low enough that veterinarians can use it at scale without creating constant alarm. IDEXX also indicated the platform would expand to cover a majority of canine cancer types, with mast cell tumor detection coming next.

While Cancer Dx pointed toward a new frontier, IDEXX kept upgrading the core. The Catalyst platform added specialty tests for pancreatic lipase and cortisol during this period—part of the third expansion of the Catalyst test menu in under a year. The message was consistent: the installed base isn’t static. It keeps getting more capable, which keeps clinics running more tests on the same IDEXX footprint.

In January 2026, IDEXX also pushed further into imaging with the launch of the ImageVue DR50 Plus Digital Imaging System at the Veterinary Meeting and Expo in Orlando. IDEXX said the system reduced radiation exposure by up to 60 percent versus competitive imaging solutions while producing higher-definition images through AI-powered processing. A larger 17-by-17-inch panel expanded the range of patients that could be imaged, and integration with IDEXX’s Web PACS software tightened the radiology workflow. It was another step toward IDEXX’s broader ambition: not just in-vitro diagnostics, but the diagnostic ecosystem—more workflow, more recurring revenue, more switching costs.

The final major development of this era was leadership. On January 13, 2026, IDEXX announced that Jay Mazelsky—President and CEO since stepping in as interim chief executive in June 2019 after Jonathan Ayers’s serious bicycling accident—would become Executive Chair of the Board effective May 12, 2026. Michael Erickson, PhD, would take over as CEO.

It’s hard to pick a clearer signal about where the board believes the next decade comes from. Erickson had been at IDEXX since 2011 and most recently led Global Point of Care Diagnostics and Telemedicine—the product lines that include Catalyst and inVue Dx. Before IDEXX, he worked as an Associate Principal at McKinsey advising pharmaceutical and biotech firms, and his doctorate underscored the company’s tilt toward deep technical execution. An internal, diagnostics-focused successor read as continuity: IDEXX wasn’t looking to reinvent itself. It was looking to press its advantage.

Mazelsky’s own rise reflected the company’s operator DNA. After Ayers’s 2019 accident, Mazelsky stepped in as interim leader and proved steady enough to earn the permanent role. Under his tenure, IDEXX navigated the pandemic demand surge, accelerated the innovation pipeline, and extended its market leadership. He planned to retire following the annual shareholder meeting in May 2027 after a transition period with Erickson. Ayers, meanwhile, resigned from the board effective November 2024—closing a chapter that began when he took over as CEO in 2002.

Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

The IDEXX story offers lessons that travel far beyond veterinary diagnostics. Strip away the lab coats and analyzers, and you’re left with a case study in how to build a dominant franchise—then make it harder and harder to dislodge.

The first lesson is the power of being the arms dealer in a growing market. IDEXX doesn’t own veterinary practices. It doesn’t employ veterinarians. And it doesn’t compete with its customers. It sells the picks and shovels—diagnostics, instruments, software, and services—and then benefits from every force that makes veterinary care bigger: more pets, more spending per pet, more testing per visit, and more visits over a pet’s lifetime.

That positioning is quietly brilliant. Owning practices, as Mars does through VCA and Banfield, can absolutely create scale—but it also drags in the messy parts of healthcare operations: labor shortages, facility costs, regulatory exposure, and day-to-day management complexity. IDEXX gets to ride the same demand curve with a very different risk profile. It captures growth without having to run the clinics.

The second lesson is how to turn a transactional category into a recurring revenue machine. Before IDEXX, diagnostic testing was mostly episodic: order a test, pay for it, move on. IDEXX changed the relationship by placing instruments in clinics and tying those instruments to ongoing consumable purchases. The feel is closer to enterprise software than to classic med-dev—once a Catalyst analyzer is in the building, the clinic’s workflow starts to orbit around it, and the consumables become a long-lived, predictable stream. IDEXX doesn’t have to “re-win” the customer every quarter. It has to keep the system reliable and the customer satisfied.

The third lesson is that the strongest moats are rarely single walls. IDEXX’s advantage is a set of reinforcing advantages that stack together into something far more durable than any one of them alone. Switching costs are real: changing analyzers and test menus isn’t like swapping out office supplies; it means retraining staff and disrupting clinical routines. A direct sales force keeps relationships tight in a way distributors rarely can. VetConnect PLUS creates data flywheels that get better as usage scales. And ecosystem lock-in—the integration of instruments, consumables, software, reference labs, and now imaging—means a competitor can’t win with one great product. To truly displace IDEXX, you have to match the whole system.

Capital allocation is the glue that makes that system compound. IDEXX has consistently poured meaningful dollars into R&D—around 7.5 percent of revenue—to stay ahead on the product roadmap. It has used acquisitions selectively, usually when a deal fills a real strategic gap, like ezyVet. And it has returned capital through buybacks rather than dividends, which fits a business with strong reinvestment opportunities and high returns on invested capital. Dividends would imply maturity. IDEXX has been behaving like a company still in build mode, even at massive scale.

It also helps to understand why veterinary diagnostics is structurally more attractive than human diagnostics—because that’s the foundation under IDEXX’s margin profile and staying power.

In human medicine, diagnostics companies run an obstacle course: insurance reimbursement, heavy regulation, hospital purchasing committees, group purchasing organizations, and long adoption cycles shaped by layers of decision-makers. New tests often require FDA clearance or authorization, clinical validation, coding, and reimbursement negotiations. That process can take years and cost enormous sums. And even then, the final gatekeeper can be an insurer deciding the test isn’t “medically necessary.”

Veterinary medicine is different. The veterinarian is usually the decision-maker, and the pet owner pays directly. Regulatory requirements are typically less burdensome than in human diagnostics for many products, and the buying cycle is measured in weeks, not years. There’s no insurer in the middle dictating what gets ordered. No reimbursement committee negotiating price down. The vet recommends, the owner agrees, and the clinic runs the test. That’s a big reason IDEXX can sustain operating margins north of 30 percent on a revenue base approaching $4 billion—economics that human diagnostics companies would love to have.

One final lesson: geographic expansion matters even more when you’re already dominant at home. Once you’ve captured a large share of your domestic market, growth becomes incremental and competitive. IDEXX avoided that stall by exporting its playbook internationally, where diagnostic utilization has often lagged the U.S. by years. Each new country is a chance to build the same loop—reference labs, instrument placement, software integration, and workflow lock-in—before habits fully form and before competitors cement their positions. International has been growing faster than the U.S. business and offers a longer runway, giving IDEXX a second engine even as its core market matures.

Analysis: Bear versus Bull Case

The Bull Case

IDEXX sits in one of those rare sweet spots where market structure and business design reinforce each other. With roughly 60 to 65 percent share of the North American in-clinic diagnostics market and customer retention above 97 percent, it starts every year with an unusually stable base. And because the core model is built around recurring consumables tied to an installed instrument footprint, that base doesn’t just sit there—it tends to grow.

The category itself is expanding, too. The companion animal diagnostics market is projected to grow from about $2.99 billion in 2024 to $4.55 billion by 2029, close to a 9 percent annual growth rate. IDEXX doesn’t need to “win” all of that growth to do well. It just needs to keep doing what it’s done for decades: place instruments, drive utilization, and keep clinics inside the ecosystem. The more a practice leans into diagnostics as standard of care, the more IDEXX’s integrated stack—hardware, consumables, software, and reference labs—starts to feel less like a vendor relationship and more like the clinic’s operating system.

International is the other big upside lever, and it’s still early. Diagnostic utilization in Europe, Asia, and Latin America generally trails the U.S. That gap is the opportunity. International already accounts for about 35 percent of revenue, and double-digit organic growth in recent quarters suggests the playbook is translating. As pet ownership rises and owner expectations shift toward more preventive care, IDEXX’s advantage comes from being on the ground with reference lab capacity, a direct sales force, and a footprint of instruments already embedded in clinic workflows.

Look at IDEXX through Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers, and the picture is unusually stacked. Switching costs show up in the day-to-day reality of a clinic: instruments, staff training, reference ranges, integrations, and routines that are painful to unwind. Network effects emerge as more results flow through VetConnect PLUS and improve the usefulness of the platform. Scale economies are real in a global network of more than 70 reference labs and a distribution machine built over decades. Counter-positioning matters because rivals can’t easily copy the integrated platform model without years of investment and messy integration, often while their existing businesses keep running. And IDEXX has cornered resources in proprietary tests like SDMA and Cancer Dx, plus a direct sales force with deep relationships that no competitor can spin up quickly. Most companies are thrilled to have one of these. IDEXX can credibly claim several at once.

Porter’s Five Forces is similarly favorable. Supplier power is muted because IDEXX designs and manufactures its own instruments and consumables. Buyer power is fragmented across thousands of independent practices, none of which is big enough to dictate terms—and most of which face meaningful switching costs anyway. Substitutes are limited: evidence-based veterinary medicine runs on diagnostics; you can’t replace bloodwork with a hunch. New entrants face a brutal barrier: to truly compete, they’d need to replicate not just a machine, but a full system—reference labs, logistics, software integration, sales relationships, and installed base—built through decades of cumulative investment. Rivalry exists, but the ecosystem makes direct head-to-head battles extremely expensive.

The Bear Case

The cleanest risk is valuation. With a price-to-earnings ratio in the mid-50s, IDEXX is priced like what it is: a high-quality compounder with durable growth. The problem is that this leaves little room for disappointment. If organic growth slows, if margins compress, or if markets rotate away from premium “quality growth” stocks, the multiple can come down fast. When expectations are high, even a modest miss can hurt.

Competition is also becoming more credible. In 2023, Mars acquired Heska, creating the most serious integrated challenger IDEXX has faced. Mars now has Antech reference labs, Heska point-of-care instruments, VCA and Banfield hospitals, and Synlab’s European veterinary diagnostics. If Mars can actually knit those pieces into a coherent system—and use its hospital footprint to drive volume—it could pressure IDEXX in a way fragmented competitors never could. Zoetis is pushing, too, advancing its diagnostic portfolio with launches like the Vetscan OptiCell hematology analyzer in early 2024 and AI-powered analysis tools in 2025. So far, IDEXX’s share hasn’t shifted meaningfully, but the competitive temperature is rising.

Then there’s the reality of maturity in the U.S. companion animal market. Most clinics already have some form of in-clinic diagnostics. That means IDEXX increasingly has to grow through deeper penetration: higher utilization per instrument, more premium upgrades, and placing newer systems like inVue Dx into clinics that may already own a Catalyst. That’s harder than winning greenfield placements. It requires behavior change, workflow change, and convincing a busy practice that “good enough” isn’t good enough anymore.

Finally, pet spending is more cyclical than the narrative sometimes admits. Pet humanization is real, but diagnostics still sit inside household budgets. In a severe downturn, owners can and do defer wellness testing, postpone follow-ups, or decline expensive workups—especially for older animals. This happened in the 2008–2009 recession, when veterinary visit volumes declined and IDEXX’s growth slowed. The business didn’t break—the installed base continued to throw off consumable revenue—but demand wasn’t immune.

Myth versus Reality

One story that needs a reality check is the idea that IDEXX is “recession-proof” because people love their pets. People do love their pets. But love doesn’t always translate into the same level of spending when household finances tighten. In 2008–2009, veterinary visits fell meaningfully. Owners delayed elective appointments, skipped annual wellness exams, and postponed chronic-condition workups. IDEXX slowed accordingly. The better framing is recession-resistant, not recession-proof: acute diagnostics tend to hold up, but the incremental growth engine—wellness and preventive testing—has a discretionary component and can compress when the economy does.

Another common claim is that IDEXX has a “monopoly.” That’s overstated. IDEXX clearly dominates in-clinic diagnostics, but the broader diagnostic landscape includes reference labs, imaging, and point-of-care rapid tests where competition is very real. Mars-Antech is formidable in reference labs. Zoetis is investing heavily in point-of-care and AI-driven tools. IDEXX’s moat is wide and deep, but maintaining it still requires continued innovation and execution.

Key KPIs to Watch

If you want to track whether the IDEXX story is staying on script, two metrics do most of the work.

First: organic revenue growth in the Companion Animal Group. That’s the heartbeat of the business. It reflects underlying demand for diagnostics, IDEXX’s ability to place new instruments, and its ability to drive utilization on the instruments already in clinics. If CAG organic growth were to slow and stay below mid-single digits, it would be a real signal—whether of saturation, share pressure, or a softening in veterinary spending.

Second: growth in the premium instrument installed base, especially Catalyst, ProCyte, and inVue Dx. Instrument placements today are a leading indicator for consumables tomorrow. The inVue Dx number matters disproportionately because it’s not just a replacement cycle—it’s IDEXX trying to expand what clinics can do in-house and open up new categories of testing. If that installed base keeps growing, the annuity stream strengthens. If it plateaus, it suggests a tougher environment: more maturity, more competition, and a harder path to growth.

Epilogue: If We Were Running IDEXX

The most interesting strategic question facing IDEXX is whether it should expand beyond diagnostics into treatment. Today, IDEXX tells veterinarians what’s wrong with the animal. It doesn’t provide the drugs, therapies, or interventional tools to fix it. Cancer Dx captures both the opportunity and the tension. IDEXX can now flag lymphoma in a dog months before clinical signs appear, but it can’t deliver the next step that early detection makes possible. Moving into therapeutics would be a major shift. It could put IDEXX on a collision course with Zoetis and other animal health pharmaceutical giants. But it would also open a huge adjacent market and potentially deepen IDEXX’s role with clinics from “diagnostic partner” to something closer to a full-spectrum care platform.

A less dramatic, but equally consequential, opportunity is simply running the international playbook faster. The gap between U.S. and international diagnostic utilization remains one of the clearest growth opportunities in the portfolio. And the recipe is the same blocking and tackling IDEXX already knows how to do: add reference lab capacity, build local sales coverage, place instruments, train teams, and make the software integrations effortless. Third quarter 2025 showed double-digit international organic growth, a sign the machine travels well. The bigger point is that the runway still looks long.

The ezyVet acquisition also hinted at what may be IDEXX’s ultimate ambition: becoming the veterinary operating system. If IDEXX can own the in-clinic diagnostic instruments, the reference lab network, the practice management software, imaging systems, the data platform, and the tools that connect vets to clients, it becomes the infrastructure layer modern veterinary medicine runs on. Cornerstone already serves more than 125,000 veterinary professionals. VetConnect PLUS aggregates diagnostic history across in-clinic and reference lab testing. New systems like inVue Dx and new assays like Cancer Dx don’t just improve the existing workflow; they expand what clinics can do in-house. Each new product adds another strand of integration, making the overall platform harder to replace. If that vision fully clicks, IDEXX won’t just be the leader in veterinary diagnostics. It will be the default platform for running a veterinary practice.

Software is the piece to watch most closely, because it may be where IDEXX’s next major advantage compounds. With Cornerstone serving established practices, ezyVet built for cloud-first clinics, and VetConnect PLUS tying diagnostic data together across them, IDEXX is building something that starts to resemble the veterinary version of Epic in human healthcare. Epic’s power doesn’t come from winning one feature war at a time. It comes from being comprehensive—and from how painful it is to rip out once embedded. IDEXX is pursuing a similar logic in veterinary medicine, and it’s further along than many people realize. With ImageVue expanding the imaging workflow, DecisionIQ adding AI-powered interpretive support, and broader telemedicine and client communication capabilities, the software layer is evolving from a results portal into a clinical platform.

The lessons travel well beyond animal health. IDEXX is a case study in what can happen in a fragmented professional market where practitioners are independent operators, where technology can improve workflow and outcomes, and where data becomes a flywheel. Dentistry, optometry, independent pharmacies, dermatology—anywhere you can place mission-critical equipment, earn recurring consumables or services revenue, integrate into the system of record, and use data to improve the product, you can see echoes of the IDEXX playbook. IDEXX proved the pattern works. The next question is who else will try to run it.

Mike Erickson, the incoming CEO, inherited a company in an enviable position: dominant share, accelerating innovation, and strong secular tailwinds—plus a market capitalization that reflects how much confidence investors have in continued execution. The job now is to keep the discipline that built the franchise while deciding where, and how far, to push into new markets and categories that come with unfamiliar risks. That’s the trade: protect the moat, and still keep building.

Recent News

In January 2026, IDEXX laid out its succession plan: Jay Mazelsky would shift to Executive Chair, and Michael Erickson would step in as President and CEO on May 12, 2026. Mazelsky also signaled a clear end date, saying he planned to retire after the annual shareholder meeting in May 2027, following a year-long transition.

A few weeks later, at the 2026 Veterinary Meeting and Expo in Orlando, IDEXX used the industry’s biggest stage to unveil its newest push into imaging: the ImageVue DR50 Plus Digital Imaging System. It was positioned as the company’s most advanced radiology offering yet, with AI-powered image processing, radiation doses up to 60 percent lower than competing systems, and a larger panel option designed to handle a wider range of patients.

Meanwhile, IDEXX kept turning last year’s headline launch into installed base. Throughout 2025, the company continued shipping the inVue Dx Cellular Analyzer, and by the second quarter had placed nearly 2,400 units. The promise was simple but powerful: take a workflow that traditionally required manual slide prep and microscope time, and make it fast, standardized, and AI-assisted—bringing in-clinic cellular analysis to general practice in a way that previously leaned heavily on technician skill and reference labs.

IDEXX also pushed into a new category that could reshape routine care: cancer screening. IDEXX Cancer Dx, announced in January 2025 and available beginning in March 2025, introduced an early detection test for canine lymphoma designed to be affordable enough for routine wellness visits. IDEXX priced it at $15 and said it planned to expand the platform to cover additional cancer types over time.

All of this played out against a backdrop of strong operating performance. In the third quarter of 2025, IDEXX reported revenue of $1.105 billion on 12 percent organic growth, with operating margins rising to 32.1 percent. The company raised full-year earnings guidance to $12.81 to $13.01 per share. Companion Animal Group Diagnostics recurring revenues grew more than 10 percent organically, and international growth continued to outpace the more mature U.S. business.

Links and Resources

IDEXX Laboratories Investor Relations: ir.idexx.com

IDEXX Product Catalog and Veterinary Diagnostics Overview: idexx.com/en/veterinary

American Pet Products Association (APPA) Industry Statistics: americanpetproducts.org

Companion Animal Diagnostics Market Research: Market Research Future; Grand View Research

Historical IDEXX SEC Filings: SEC EDGAR (search “IDEXX Laboratories”)

Veterinary Industry Economics and Market Data: American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Economic Reports

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music