DoorDash: Building the Last Mile of Local Commerce

I. Introduction & Cold Open

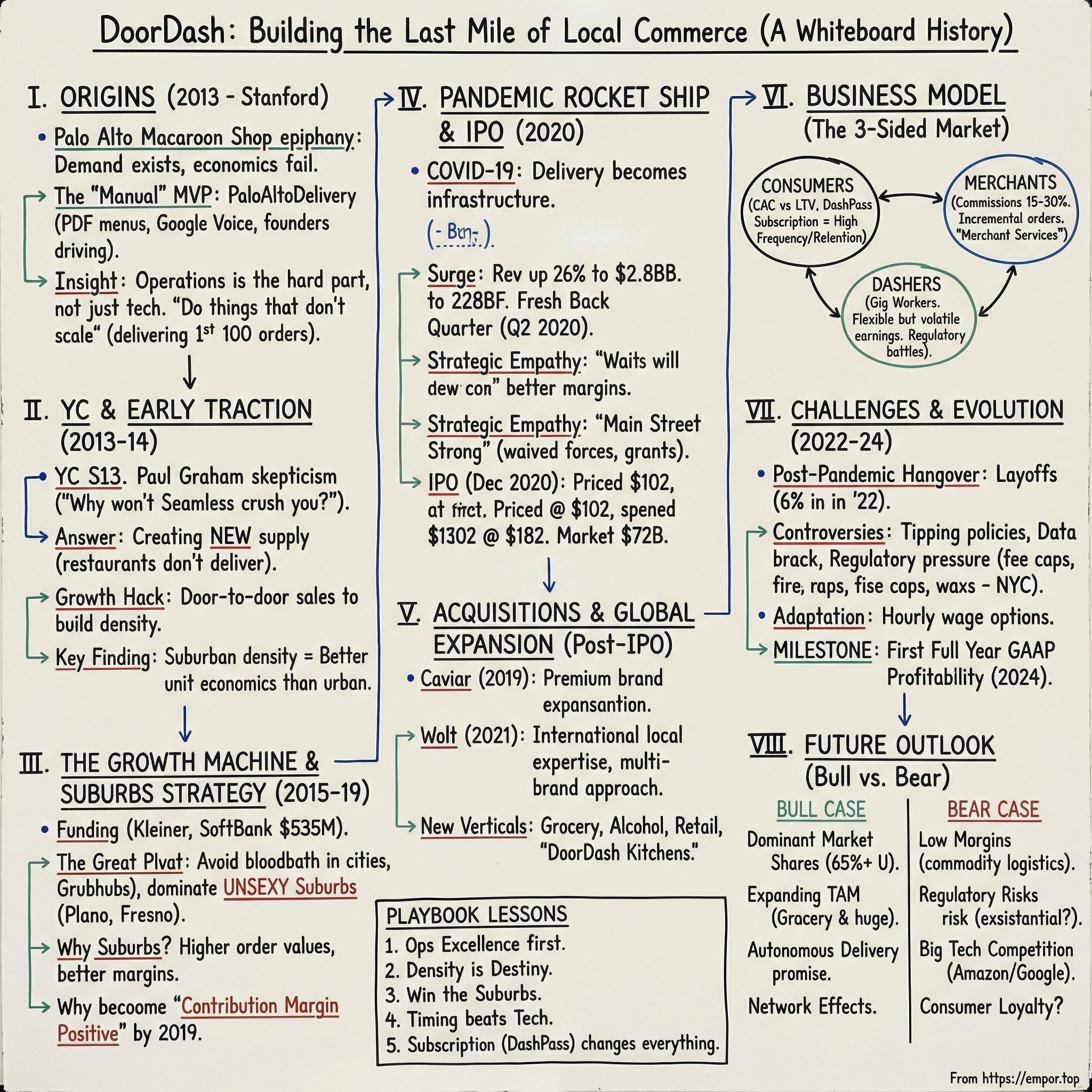

The morning of December 9, 2020, felt electric at DoorDash's San Francisco headquarters. Tony Xu, the company's soft-spoken CEO, watched his Bloomberg terminal as the numbers climbed: $182... $185... $189. By market close, DoorDash shares had soared 86% above their $102 IPO price, crystallizing a market capitalization of $72 billion. The financial press couldn't resist the irony—here was a company that had lost $149 million in just the first nine months of 2020, now worth more than Kroger, the nation's largest supermarket chain with 2,700 stores and a century of operations.

Yet this wasn't another pandemic bubble story. Hidden beneath the frothy valuations lay a grinding decade-long battle for local commerce dominance, fought block by block, restaurant by restaurant, in the unglamorous trenches of food delivery logistics. Four Stanford students had somehow outmaneuvered Uber's billions, Amazon's ambitions, and GrubHub's decade-long head start to capture 56% of the U.S. food delivery market.

The question that haunts Silicon Valley isn't how DoorDash won—it's why everyone else lost. After all, food delivery seemed like a commodity business: low margins, high competition, minimal differentiation. Conventional wisdom said the space would consolidate around whoever had the deepest pockets. Instead, DoorDash rewrote the playbook by doing precisely what venture capitalists tell you not to do: they started hyperlocal, stayed manual far too long, and burned cash competing in the most expensive market segments. Today, as we record this episode in August 2025, DoorDash commands between 65-67% market share in the United States, with a market capitalization of $108.23 billion. The company has completed over 5 billion deliveries since 2013 and finally achieved its first full year of GAAP profitability in 2024. This story—from four Stanford students delivering Thai food in their own cars to a platform processing $80.1 billion in gross order value in 2024—offers profound lessons about timing, operational excellence, and the power of doing things that don't scale until you absolutely must.

What follows is the definitive account of how DoorDash built the rails for local commerce, weathered existential threats, and emerged as the unlikely winner in one of Silicon Valley's most brutal battlegrounds.

II. The Stanford Macaroon Shop: Origins & Founding Story

The mythology of DoorDash begins not in a garage or a dorm room, but in a small macaroon shop on University Avenue in Palo Alto. It was January 2013, and Tony Xu—then a Stanford MBA student who'd spent his childhood helping his mother work in restaurants—was conducting customer development interviews with local businesses. The shop's owner pulled out a thick booklet, pages yellowed and dog-eared, filled with delivery orders she'd been forced to decline. "I lose dozens of customers every day," she told him, frustration evident in her voice. "People want delivery, but I can't afford to hire drivers."

This wasn't supposed to be a lightbulb moment. Xu and his classmates—Andy Fang and Stanley Tang, both computer science undergrads, and Evan Moore, another MBA student—had been exploring various startup ideas for their class project. They'd considered everything from enterprise software to social networks. But standing in that macaroon shop, watching potential revenue literally slip through the owner's fingers, they saw something others had missed: the vast majority of restaurants couldn't offer delivery not because customers didn't want it, but because the economics didn't work.

The team's backgrounds proved serendipitous. Tony Xu brought empathy from his restaurant experience—he understood the razor-thin margins, the complexity of kitchen operations, the challenge of finding reliable staff. Andy Fang, quiet and methodical, had the engineering chops to build systems that could scale. Stanley Tang brought product sensibility and an obsession with user experience. Evan Moore, who would later leave but played a crucial early role, understood business development and operations.

Their first move was almost comically simple: they built a landing page. Not an app, not a platform—just a basic website called "Palo Alto Delivery" with six PDF menus from local restaurants and a Google Voice phone number. The total development time: one afternoon. The delivery fee: $6, flat rate. They had no drivers, no dispatch system, no backend infrastructure. When orders came in, they'd literally call the restaurant, place the order as a customer, then drive over in their own cars to pick it up. The first order came in within hours—Thai food from a local restaurant, ordered by a woman named Alice. Tony delivered it himself, racing through Stanford's campus in his Honda Accord, the steaming containers sliding across his backseat as he took corners too fast. When he arrived, slightly out of breath, Alice seemed surprised. "You're the CEO?" she asked. Tony just smiled and handed her the food. That night, he sent Alice a personal email thanking her for being their first customer, asking what could be improved. She wrote back immediately, stunned that anyone cared enough to ask.

This manual, unscalable approach became DoorDash's DNA. While competitors were raising millions to build sophisticated dispatch algorithms, the DoorDash founders were using a spreadsheet, their personal cell phones, and a WhatsApp group to coordinate deliveries. They'd text each other constantly: "Andy, can you grab the Chipotle order?" "Stanley's stuck in traffic, someone needs to cover the pizza run." It was chaos, but it was their chaos, and it taught them something crucial: the hardest part wasn't the technology—it was the operations.

The founders made a pact: they would personally deliver the first 100 orders. Not 10, not 50, but 100. They wanted to feel every pain point, understand every failure mode. They discovered that parking was often the biggest time sink—a driver could spend 10 minutes circling the block looking for a spot. They learned that restaurant kitchens had rhythm—order at 6:15 PM and wait 45 minutes, order at 6:45 PM and get it in 15. They realized that customer anxiety peaked not when food was late, but when they didn't know it was late.

By February 2013, they'd incorporated as DoorDash, leaving behind the provincial "Palo Alto Delivery" name. The rebrand was strategic—they were already thinking beyond Stanford, beyond Palo Alto, beyond the Bay Area. But first, they had to prove the model worked at all. As winter turned to spring, word spread through Stanford's campus. Orders grew from one per day to five, then ten, then twenty. The founders were drowning, still trying to attend classes while delivering food until 2 AM.

The moment of truth came when they had to choose: hire drivers and lose the direct customer feedback loop, or drop out of Stanford to keep delivering themselves. They chose a third option—they recruited their classmates, paying them $20 per delivery, an absurd rate that meant they lost money on every order. But they weren't optimizing for profit; they were optimizing for learning. Each driver had to fill out a detailed report after every delivery: How long did you wait? Where did you park? Did the restaurant have the order ready? Was the food still hot?

This obsessive attention to operational detail would become their moat. While competitors saw delivery as a commodity service—pick up food, drop off food—DoorDash saw it as hundreds of micro-optimizations waiting to be discovered. They were building what would later become their secret weapon: not an app, but an operations manual encoded in software, informed by thousands of real deliveries they'd personally completed.

The Stanford campus became their laboratory, but they knew they needed to graduate—literally and figuratively—to something bigger. Y Combinator was calling, and with it, the chance to turn their scrappy experiment into a real company.

III. Y Combinator & Early Traction

The Y Combinator interview room felt smaller than it was. Paul Graham sat across from the four founders, arms crossed, skepticism written across his face. "Caviar for Palo Alto," he'd written in his notes, alongside the observation that they'd brought cookies—arguably their first successful delivery. It was April 26, 2013, and the company wasn't even incorporated yet, had no funding, no app—just a website at paloaltodelivery.com—and had completed only 217 deliveries.

Graham's first question cut straight to the heart: "Why won't Seamless just crush you?" Tony Xu's answer would define everything that came next. "Seamless only works with restaurants that already deliver. We're creating new supply. We're not competing for the same restaurants—we're expanding the market itself." The room went quiet. This wasn't just another food delivery play; it was a fundamentally different approach to the problem.

Y Combinator invested $120,000 for 7% of the company, valuing DoorDash at roughly $1.7 million. But more valuable than the cash was the pressure cooker environment. Every Tuesday, the founders would present their metrics to the entire batch. Growth was the only currency that mattered. In their first weeks, they were growing at 20% week-over-week—respectable but not remarkable. By June, Paul Graham's partner noted with concern: "So far, nothing is working that well. They need to keep trying a lot of different experiments to figure out user acquisition".

The breakthrough came from an unlikely source: refrigerator magnets. No, really. While the YC partners had suggested physical magnets (advice the founders wisely ignored), the concept sparked something deeper. They realized their customer acquisition problem wasn't about technology—it was about habit formation. People ordered pizza because they had the number memorized. DoorDash needed to become that automatic.

Their solution was elegantly analog: they went door-to-door in Palo Alto, literally knocking on doors during dinner time. "Hi, we're Stanford students building a food delivery service. What restaurants do you wish delivered?" They'd take notes, onboard those specific restaurants, then return to the same houses: "Remember us? We got your favorite Thai place to deliver. Here's a promo code." By July 16, orders had nearly doubled to 35 per day from 19 just two weeks earlier.

The Demo Day pitch in August 2013 was a masterclass in simplicity. Tony Xu opened with just seven words: "We enable every restaurant to deliver". No grand vision of transforming commerce, no mention of autonomous vehicles or ghost kitchens. Just a simple promise: any restaurant, delivered to your door. He showed their growth curve—the hockey stick every investor dreams of seeing—and their three-sided marketplace metrics.

But the moment that clinched it was when Tony revealed their unit economics. Unlike their competitors who were burning cash on customer acquisition, DoorDash was already contribution margin positive on a per-order basis. They'd discovered something counterintuitive: customers in suburban Palo Alto were willing to pay higher delivery fees than urban customers because their alternative was a 20-minute round trip drive. Geography, not just convenience, drove willingness to pay.

Following Demo Day, DoorDash raised $2.4 million in seed funding from Khosla Ventures, Charles River Ventures, SV Angel, and Paul Buchheit. Keith Rabois from Khosla would become more than an investor—he'd become their operational guru, teaching them about marketplace dynamics, the importance of contribution margins, and how to think about capital allocation in a competitive market.

The post-YC period revealed a critical insight that would shape their entire strategy: density matters more than breadth. While competitors were racing to be in every major city, DoorDash deliberately stayed small, focusing obsessively on dominating individual zip codes. They'd rather have 50% market share in Palo Alto than 5% market share across the Bay Area. This concentration allowed them to offer better delivery times (more drivers per area), better merchant relationships (more orders per restaurant), and better unit economics (shorter average delivery distances).

Even months after YC, skepticism remained—one partner had ranked DoorDash in the bottom half of their batch. But the founders had discovered something their critics missed: in local commerce, operational excellence beats technical innovation every time. While everyone else was building better apps, DoorDash was building better operations.

As autumn 2013 turned to winter, they faced a choice: raise more capital to expand, or continue grinding in Palo Alto. They chose expansion, but with a twist—they'd grow like a virus, one adjacent zip code at a time, never leaving a market until they dominated it. This patient, methodical approach would soon collide with Silicon Valley's growth-at-all-costs mentality, setting up the battles that would define the next phase of their journey.

IV. The Growth Machine: Building Density & Fighting for Market Share

March 2015. John Doerr sat across from Tony Xu in Kleiner Perkins's Sand Hill Road office, the same conference room where he'd once grilled Larry Page and Sergey Brin. "You're asking for $40 million at a $600 million valuation," Doerr said, leaning back in his chair. "Uber's food delivery experiment is launching next month. Amazon's testing restaurant delivery. Why won't they crush you?"

Tony's response was pure operational philosophy: "Because they think delivery is a feature. We think it's a company."

That answer earned DoorDash not just the $40 million Series B but something more valuable—John Doerr himself on the board. The legendary investor who'd backed Amazon and Google saw something familiar in DoorDash's methodical market expansion. They weren't trying to be everywhere at once; they were building density, neighborhood by neighborhood, like laying siege to a city one block at a time.

The Kleiner investment came at a crucial inflection point. DoorDash had expanded from Palo Alto to nine markets, including their first East Coast beachheads in Boston, Brooklyn, and Washington D.C. But expansion revealed a harsh truth: what worked in suburban Palo Alto failed spectacularly in urban Brooklyn. Delivery times stretched to 90 minutes. Drivers got lost. Restaurants complained about cold food. Customer retention plummeted.

The team made a counterintuitive decision: they pulled back. Instead of continuing to expand, they focused on just three markets—San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Chicago—and decided to perfect the model before growing further. This meant building local operations teams in each city, not just downloading an app and hoping for the best. Each market got a general manager, a head of driver operations, and crucially, a head of merchant sales who would pound the pavement, restaurant by restaurant.

The playbook that emerged was almost militaristic in its precision. When entering a new zone, DoorDash would first map every restaurant within a two-mile radius. Then they'd identify the top 20 that customers most wanted but couldn't get delivered. The sales team would camp out at these restaurants, sometimes visiting ten times before getting a yes. Once they had critical mass—usually 40-50 restaurants—they'd launch with a blitz: flyers under every door, promotional codes plastered on local blogs, partnerships with apartment buildings.

But 2016 brought existential threats. Internal documents from this period, later revealed, showed the company's valuation had actually dropped from a hoped-for $1 billion to around $700 million. Employee morale cratered. Competitors were raising massive rounds—Uber Eats had Uber's billions behind it, Grubhub was going public, and Postmates had just raised $140 million. DoorDash was burning $20 million per quarter with no path to profitability.

The board meetings grew tense. One investor suggested selling to Grubhub. Another pushed for a pivot to grocery delivery. But Tony Xu and his team had noticed something in their data that everyone else missed: suburban markets were actually profitable on a unit basis. The problem wasn't the business model—it was the market mix. Urban markets with their brutal competition and higher driver costs were bleeding money, but suburbs with their longer distances and higher order values were contribution margin positive.

This insight led to DoorDash's most important strategic decision: while competitors fought bloody battles in Manhattan and San Francisco, DoorDash would own the suburbs. They'd be the only delivery option in places like Fremont, California, or Plano, Texas—unglamorous markets that venture capitalists never visited but where millions of Americans actually lived. The 2017 acquisition of Rickshaw, a small logistics startup no one had heard of, seemed insignificant at the time. But it represented a crucial pivot in DoorDash's thinking: they weren't just aggregating restaurants; they were building the infrastructure for local commerce itself. Rickshaw's team had developed sophisticated routing algorithms that could handle complex multi-stop deliveries—exactly what DoorDash needed to move beyond food.

Then came the SoftBank moment. March 2018. Masayoshi Son's Vision Fund had just poured billions into Uber. DoorDash's board was panicking—how could they compete with Uber's war chest? Jeffrey Housenbold from SoftBank had been circling DoorDash for months, but negotiations stalled as Son debated whether food delivery would be winner-take-all. Finally, Housenbold convinced him: this market was big enough for multiple winners.

SoftBank led a $535 million investment in DoorDash in early 2018, lifting the company's valuation to $1.4 billion—finally achieving unicorn status after years of being undervalued. But the cost was steep: massive dilution for the founders and early investors. Tony Xu's stake dropped to just 4.4%, compared to Brian Chesky's 12% at Airbnb. It was a devil's bargain, but one they had to make.

The SoftBank capital unleashed a blitzkrieg expansion. DoorDash expanded from 600 to 1,600 cities in the U.S., but not randomly—they followed their density playbook religiously. Each new market got the full treatment: local team, merchant partnerships, driver recruitment, customer acquisition. They'd learned from 2016's failures that you couldn't just turn on the app and hope for the best.

The data from this period tells a remarkable story. By December 2018, DoorDash had overtaken Uber Eats in market share. By March 2019, they'd passed GrubHub to become the market leader with 27.6% share. The suburbs strategy was working—while competitors fought over Manhattan and San Francisco, DoorDash was quietly dominating places like suburban Dallas, Phoenix, and Atlanta.

But the real innovation wasn't geographic—it was operational. DoorDash built what they called "merchant services," tools that helped restaurants run their businesses better. They provided tablets for order management, analytics on customer preferences, even lending programs for equipment upgrades. They weren't just a delivery company; they were becoming the operating system for local restaurants.

The competitive response was fierce. Uber Eats started subsidizing orders with billions in losses. Grubhub acquired Eat24 from Yelp for $288 million. Amazon launched restaurant delivery in select cities. Yet DoorDash kept gaining share. Why? Because they understood something fundamental: in local commerce, relationships matter more than technology. Their local teams knew restaurant owners by name, understood their specific challenges, solved their unique problems.

By early 2019, DoorDash had achieved something remarkable: they became "contribution margin positive," profitable on a per-order basis, with their earliest markets actually profitable. This wasn't supposed to be possible in food delivery—everyone assumed it was a permanently subsidized business. But DoorDash's density strategy created network effects that competitors couldn't match.

The February 2019 Series F, raising $400 million at a $7.1 billion valuation, marked a turning point. DoorDash wasn't just surviving; they were winning. Market leadership was within reach. But as 2019 drew to a close, no one could have predicted what 2020 would bring—a global pandemic that would transform food delivery from a convenience to a necessity, setting the stage for one of the most dramatic IPOs in Silicon Valley history.

V. The Pandemic Rocket Ship & IPO

March 13, 2020. Tony Xu sat in DoorDash's eerily empty San Francisco headquarters, watching order volumes on his dashboard. The numbers didn't make sense. It was 2 PM on a Friday—normally a slow period—but orders were surging 40% above normal. California had just announced its shelter-in-place order. Everything was about to change.

Within 72 hours, DoorDash transformed from a food delivery company into critical infrastructure. Restaurants that had never offered delivery were calling desperately, begging to be onboarded immediately. Drivers who'd lost their jobs in retail and hospitality were signing up by the thousands. And customers—millions of customers who'd never used food delivery before—were downloading the app as their lifeline to the outside world.

DoorDash's revenue exploded from $885 million in 2019 to $2.88 billion in 2020—a staggering 226% increase that defied all projections. But this wasn't just opportunistic growth. The company made a series of strategic decisions that would define not just their pandemic response but their entire future trajectory.

First, they waived all commission fees for independent restaurants for 30 days, then extended it repeatedly. While competitors tried to maximize pandemic profits, DoorDash invested in keeping restaurants alive. 67% of restaurants said DoorDash was crucial to their business during COVID-19, with 65% saying they were able to increase profits during the pandemic due to DoorDash. This wasn't charity—it was strategic relationship building that would pay dividends when the world reopened.

Second, they launched "Main Street Strong," a $200 million program providing grants and zero-interest loans to restaurants. They created contactless delivery protocols before anyone else, introduced hand sanitizer reimbursements for drivers, and implemented financial assistance programs for quarantined Dashers. Every decision reinforced their positioning: DoorDash wasn't exploiting a crisis; they were solving it.

The operational challenges were staggering. Delivery orders soared 67% in March 2020, even as overall restaurant traffic fell 22%. DoorDash's systems, built for steady growth, suddenly had to handle double the volume. Their dispatch algorithms broke. Customer service queues stretched to hours. Restaurant tablets crashed under the load.

But here's where DoorDash's years of operational grinding paid off. They'd built modular systems that could scale horizontally. Within weeks, they'd quintupled their customer service team, redesigned their dispatch algorithms for pandemic patterns (lunch orders disappeared, dinner orders doubled), and created entirely new product features like group ordering for virtual office lunches.

The unit economics told an extraordinary story. Prior to Q2 2020, DoorDash's gross margins hovered between 39% and 42%. Then in Q2, gross margins broke out to new heights, with the company becoming contribution margin positive and achieving its first profitable quarter—$23 million in net income. For exactly one quarter, the impossible had happened: food delivery was profitable.

By summer 2020, DoorDash's board faced a decision: go public while the market was hot, or wait for more stability. The traditionalists argued for patience—the pandemic boost might be temporary, valuations were frothy, the market could crash. But Tony Xu saw opportunity. If DoorDash was going to expand beyond food, beyond delivery, into the operating system for local commerce, they needed capital and credibility. An IPO would provide both.

The S-1 filing in November 2020 revealed stunning numbers. Revenue had more than tripled in the first nine months of 2020 to $1.92 billion, while losses narrowed from $533 million to $149 million. Market share had exploded from 34% to 49% in a single year. They were no longer burning cash—in fact, they'd generated $315 million in free cash flow.

But the document also contained warnings. Growth rates would inevitably slow. Competition remained fierce. Regulatory challenges loomed. The company admitted what everyone suspected: DoorDash was only able to show profitability at the height of the lockdowns. Could they maintain momentum when the world reopened?

The IPO roadshow, conducted entirely over Zoom, was unlike anything Wall Street had seen. Tony Xu, camera-shy and soft-spoken, had to sell a vision of the future from his home office. His pitch was simple but powerful: the pandemic hadn't created new behaviors—it had accelerated existing trends by five years. Convenience, once a luxury, was now an expectation. Local commerce would never go back.

Initial pricing discussions centered around $75-85 per share, seeking a $32 billion valuation. But demand was overwhelming. Retail investors, who'd relied on DoorDash during lockdowns, wanted in. Institutional investors saw the market leadership and improving unit economics. The price kept rising: $90, $95, $100. Finally, on December 8, 2020, DoorDash priced at $102 per share.

December 9, 2020. 9:30 AM Eastern. The opening bell rang at the New York Stock Exchange, though Tony Xu watched from San Francisco, pandemic protocols keeping him away. The first trade crossed at $182—78% above the IPO price. By market close, DoorDash shares hit $189.51, up 86%, valuing the company at $72 billion. SoftBank's Vision Fund had turned its $680 million investment into $11.5 billion—a 17x return.

The IPO created 17 new billionaires on paper, including the three remaining co-founders. But more importantly, it validated a thesis: local commerce was the next great platform opportunity. DoorDash wasn't just delivering food; they were building the infrastructure for how local economies would function in the 21st century. The pandemic had been their catalyst, but their ambitions stretched far beyond it.

VI. Strategic Acquisitions & Global Expansion

The $410 million acquisition of Caviar from Square in August 2019 seemed like a luxury DoorDash couldn't afford. They were still burning cash, fighting brutal market share battles, and here they were buying a premium delivery service that catered to Michelin-starred restaurants. Critics called it a vanity purchase. They were wrong.

Caviar wasn't just a delivery service—it was a brand that meant something. In cities like New York and San Francisco, saying "I'll Caviar it" had become shorthand for ordering from the city's best restaurants. These weren't price-sensitive customers looking for $10 pad thai; they were ordering $200 omakase dinners and $80 bottles of wine. The unit economics were completely different—higher order values, lower price sensitivity, better margins.

Gokul Rajaram, who'd led Caviar at Square and now joined DoorDash, brought a philosophy that would reshape the company's approach to premium dining. "We're not just delivering food," he told the team. "We're delivering experiences." This meant white-glove service: dedicated account managers for top restaurants, specialized packaging to maintain food quality, even temperature-controlled bags for wine deliveries.

The integration strategy was counterintuitive. Rather than folding Caviar into DoorDash, they kept it as a separate brand. Two apps, two driver pools, two operational teams. It seemed inefficient, but Tony Xu understood something critical: in local commerce, brand perception is everything. A neighborhood sushi bar might happily join DoorDash, but a James Beard Award-winning chef wanted the Caviar association.

This dual-brand strategy became the template for DoorDash's most ambitious acquisition yet. In November 2021, as the pandemic boom was cooling and investors were getting nervous about growth, DoorDash announced it was acquiring Wolt for $8.1 billion—the second-largest acquisition in the food delivery industry's history. Wolt wasn't just a company—it was DoorDash's answer to a strategic nightmare. While DoorDash dominated America, Uber Eats and Deliveroo were carving up Europe. Every quarter that passed meant higher customer acquisition costs and harder market entry. The $8.1 billion price tag made headlines—it was the second-largest acquisition in food delivery history—but Tony Xu saw it differently. This wasn't buying revenue; it was buying time.

Miki Kuusi, Wolt's Finnish co-founder, represented everything DoorDash respected: operational obsession, local market knowledge, and the ability to build density in complex European markets. Wolt had cracked markets that seemed impossible—Finland with its harsh winters, Croatia with its tourism-dependent economy, Israel with its complex kosher requirements. They'd done it not through technology but through localization, adapting their service to each market's unique needs.

The integration strategy was radical: Kuusi would run all of DoorDash's international operations, reporting directly to Tony Xu. The Wolt brand would continue independently. Essentially, DoorDash was buying not just a company but an entire international leadership team. This wasn't the typical Silicon Valley acquisition where the acquired company gets absorbed and forgotten. This was a merger of equals, at least operationally.

But the timing proved brutal. The deal closed in June 2022, just as tech stocks were crashing. DoorDash's share price had fallen 55% since the announcement, making the all-stock deal worth closer to $3.5 billion than $8.1 billion. Investors who'd celebrated 200x returns on paper watched their fortunes evaporate. Yet strategically, the deal made sense. Wolt brought DoorDash into 23 new countries overnight, markets where building from scratch would have taken years and billions more.

The international expansion revealed fundamental differences in how food delivery worked globally. In Japan, customers expected precision—orders arriving exactly at the promised time, not a minute early or late. In Germany, environmental consciousness meant a backlash against single-use packaging. In Israel, Shabbat meant entire neighborhoods shut down from Friday evening to Saturday night. Each market required not just translation but transformation of the entire operating model.

DoorDash's approach was to maintain multiple brands for different markets and segments. In the U.S., they had DoorDash for mainstream, Caviar for premium. Internationally, they had Wolt for most markets but kept the DoorDash brand for English-speaking countries. This multi-brand strategy seemed inefficient, but it recognized a truth about local commerce: trust is built locally, not globally.

The company also began experimenting with models beyond restaurant delivery. In 2019, they'd launched DoorDash Kitchen in Redwood City—their first ghost kitchen, featuring four restaurants operating from a single location. These weren't just kitchens; they were laboratories for understanding how food production and delivery could merge. Could they identify gaps in local restaurant supply and fill them with virtual brands? Could they help existing restaurants expand without new real estate?

By 2021, DoorDash was delivering alcohol in 20 U.S. states, groceries across the country, and even convenience items from stores like 7-Eleven and Walgreens. The acquisition of Chowbotics, a robotics company making fresh food vending machines, signaled ambitions beyond just delivery—they wanted to be involved in food preparation itself.

The international expansion through Wolt accelerated these experiments. In Nordic countries, Wolt Market—their own grocery stores—competed directly with traditional retailers. In Japan, they partnered with convenience stores that were already embedded in daily life. Each market became a testing ground for different models of local commerce.

But the strategic acquisitions weren't just about geographic expansion. They were about capability building. Scotty Labs brought autonomous vehicle expertise. Chowbotics brought food robotics. Bbot brought restaurant ordering software. Each acquisition added a piece to a larger puzzle: building the operating system for local commerce, not just the delivery network.

By 2022, DoorDash operated in 27 countries through its various brands. The company that had started by delivering Thai food to Stanford students now employed over 20,000 people globally. Yet the fundamental challenge remained: could they make the economics work? International expansion meant new complexity, new competition, and new capital requirements. The pandemic boom was over. The real test of DoorDash's global ambitions was just beginning.

VII. The Business Model: Unit Economics & Competitive Dynamics

The spreadsheet on Tony Xu's laptop contained the entire truth about food delivery: a $25 order generated $3.75 in revenue for DoorDash (15% take rate), cost $6 to deliver (driver pay, insurance, support), required $2 in customer acquisition, and another $1.50 in corporate overhead. Net loss: $5.75 per order. This was the math that kept every food delivery CEO awake at night—and the reason why, despite processing $80.1 billion in gross order value in 2024, profitability remained elusive for most players.

DoorDash gross order value totalled $80.1 billion in 2024, an increase of 19.9% on the year prior. Yet understanding DoorDash's business model requires examining not one marketplace but three interconnected ones, each with its own economics, dynamics, and success metrics.

The consumer side seemed straightforward: acquire customers, get them to order frequently, retain them over time. But the unit economics revealed brutal truths. Customer acquisition costs (CAC) ranged from $15 in mature markets to $50+ in competitive new territories. The average customer ordered 1.4 times per month, spending $35 per order. Without subscription revenue from DashPass, it took 6-8 months to recover CAC—assuming the customer didn't churn to a competitor offering a better promotion.

DashPass, launched in 2018 at $9.99 per month for unlimited free delivery on orders over $12, transformed these economics. DoorDash had 22 million users subscribe to DashPass and Wolt+, which gives them free delivery and free cancellation. Subscribers ordered 4-5 times more frequently than non-subscribers, had 3x better retention rates, and generated predictable monthly revenue regardless of order volume. The subscription model turned the business from transactional to relational—customers weren't choosing DoorDash for each order; they'd pre-committed to the platform.

The merchant side presented different challenges. Restaurants operated on 3-6% profit margins, yet DoorDash charged 15-30% commission rates. The math seemed impossible, but the reality was nuanced. Delivery orders were largely incremental—customers who wouldn't have visited the restaurant otherwise. Kitchen capacity that would sit idle during off-peak hours could generate revenue. Marketing costs that restaurants would have spent anyway were embedded in DoorDash's fees.

DoorDash had 590,000 partnered restaurants and grocery markets on its platform in 2024. But not all merchants were equal. National chains negotiated rates as low as 10%, while independent restaurants paid the full 30%. Premium restaurants on Caviar commanded higher order values but demanded white-glove service. Ghost kitchens optimized purely for delivery efficiency but lacked brand loyalty.

The dasher side—the supply side of the marketplace—was perhaps the most complex. Drivers weren't employees but independent contractors, a classification that sparked lawsuits and regulatory battles. In 2017, a class-action lawsuit was filed against DoorDash for allegedly misclassifying delivery drivers in California and Massachusetts as independent contractors. In 2022, a tentative settlement was reached in which DoorDash would pay $100 million total, with $61 million going to over 900,000 drivers.

The economics of being a dasher were highly variable. During peak dinner hours in dense urban areas, drivers could earn $25-30 per hour before expenses. During slow afternoon periods in suburban markets, earnings might drop to $10-12 per hour. Gas, insurance, and vehicle depreciation could consume 30-40% of gross earnings. The platforms competed fiercely for driver supply, leading to an arms race of incentives and bonuses that further pressured unit economics.

The three-sided marketplace created complex network effects. More restaurants attracted more customers, which attracted more drivers, which enabled faster delivery times, which attracted more restaurants. But these network effects were hyperlocal—dominance in San Francisco didn't help in San Diego. This locality meant the winner-take-all dynamics seen in other platform businesses didn't fully apply. Instead, it was winner-take-most, market by market.

Competition shaped every strategic decision. When Uber Eats entered a market, they'd subsidize orders by 30-40%, accepting massive losses to gain share. DoorDash had to match or lose customers. When Grubhub offered free delivery for premium restaurants, Caviar had to respond. This competitive dynamic meant that even as revenue grew, profitability remained elusive. The entire industry was trapped in a prisoner's dilemma—everyone would be better off with rational pricing, but whoever blinked first would lose share.

Ghost kitchens emerged as DoorDash's attempt to change the fundamental economics. By operating delivery-only kitchens in low-rent locations, they could reduce real estate costs by 75%. By optimizing menus for delivery (items that traveled well, high-margin products), they could improve unit economics. By operating multiple brands from a single kitchen, they could maximize utilization. CloudKitchens, Travis Kalanick's post-Uber venture, raised billions betting on this model, while DoorDash experimented with their own DoorDash Kitchens.

The regulatory environment added another layer of complexity. Cities began capping commission rates during COVID-19, limiting fees to 15% in places like New York and San Francisco. Cities across the country, including New York City, San Francisco and Jersey City, placed caps on how much delivery apps could charge restaurants for their services. While intended as temporary pandemic measures, many cities made them permanent, fundamentally altering the unit economics in major markets.

The tipping controversy revealed the tension at the heart of the gig economy model. In July 2019, the company's tipping policy was criticized by The New York Times, and later The Verge and Vox and Gothamist. Drivers receive a guaranteed minimum per order that is paid by DoorDash by default. When a customer added a tip, instead of going directly to the driver, it first went to the company to cover the guaranteed minimum. Drivers then only directly received the part of the tip that exceeded the guaranteed minimum per order. After public backlash, DoorDash changed the model, but the damage to driver relations was done.

Despite these challenges, DoorDash found paths to profitability in specific scenarios. Dense suburban markets with high order values and reasonable delivery distances could generate 20-25% contribution margins. DashPass subscribers in their second year generated 40% margins. Incremental orders from existing customers had near-zero acquisition costs. The challenge was portfolio mix—for every profitable suburban market, there was a loss-making urban battlefield.

The competitive dynamics reached a crescendo in 2019-2020. Uber tried to acquire Grubhub for $6.5 billion but walked away over antitrust concerns. Just Eat Takeaway swooped in to buy Grubhub for $7.3 billion. Uber then acquired Postmates for $2.65 billion. The U.S. market consolidated from six major players to three, with DoorDash commanding 65% market share by 2025.

This dominance allowed DoorDash to finally flex its market power. Commission rates stabilized. Promotional spending decreased. Driver incentives rationalized. DoorDash reported its first annual profit in 2024, after two years of cost cutting drives. The impossible had happened: food delivery, at scale, with market leadership, could be profitable. But it had taken over a decade, tens of billions in investment, and the consolidation of an entire industry to prove it.

VIII. Challenges, Controversies & Corporate Evolution

November 30, 2022. Tony Xu's email landed in inboxes at 3 AM Pacific Time. "This is the most difficult change to DoorDash that I've had to announce in our almost 10-year history," it began. 1,250 employees—6% of DoorDash's workforce—would be laid off. Some woke up unemployed. The company that had seemed invincible during the pandemic was suddenly vulnerable.

The layoffs represented more than just cost-cutting; they were an admission that DoorDash had fundamentally misread the post-pandemic world. "We were not as rigorous as we should have been in managing our team growth," Xu wrote. "That's on me." The company had grown from 8,600 employees at the end of 2021 to over 20,000 by late 2022, including 3,700 from the Wolt acquisition. Operating expenses were growing faster than revenue—a death spiral for any business, but especially one with DoorDash's thin margins.

But the layoffs were just the most visible of DoorDash's challenges. The company had become a lightning rod for every controversy in the gig economy. The worker classification battles reached a crescendo with a $100 million settlement in 2022, with $61 million going to over 900,000 drivers—roughly $130 per driver. Gizmodo noted the bitter irony: Tony Xu's $413 million compensation package the previous year was one of the largest CEO packages of all time.

The data breach of May 2019 had exposed 4.9 million customers, delivery workers, and merchants. Names, email addresses, delivery addresses, phone numbers, hashed passwords, and the last four digits of payment cards—all compromised. The breach had occurred months earlier but wasn't discovered until 2019, raising questions about DoorDash's security practices and transparency.

The tipping controversy refused to die. Even after changing their model in response to public pressure, investigations revealed that DoorDash was still manipulating per-delivery payouts. Drivers reported earning an average of $1.45 an hour after expenses. A new model introduced in 2020 promised transparency, but drivers remained skeptical. Trust, once broken, proved difficult to rebuild.

Regulatory challenges multiplied. New York City's minimum wage law for delivery workers, implemented in 2023, required apps to pay drivers $17.96 per hour. DoorDash responded by adding a $2 regulatory fee to all New York orders, passing the cost to consumers. San Francisco capped commission fees at 15%. Seattle required sick leave for gig workers. Each city brought new rules, new costs, new complexity.

The antitrust scrutiny intensified. A lawsuit filed by New York consumers alleged that delivery companies violated antitrust laws by requiring restaurants to charge the same prices for delivery and dine-in, despite restaurants paying commissions only on delivery orders. The plaintiffs argued this constituted price-fixing, preventing restaurants from passing delivery costs to delivery customers.

DoorDash's response to these challenges revealed a company in transition. In June 2023, they introduced an hourly wage option for drivers—a fundamental shift from the pure gig model. Drivers could choose to earn a guaranteed hourly rate during scheduled shifts, trading flexibility for stability. It was an admission that the pure gig economy model had limits.

The corporate culture evolved as well. The company that had started with founders delivering every order themselves had become a 20,000-person organization spanning 27 countries. The scrappy startup ethos clashed with corporate governance requirements. Board meetings that once focused on delivery times now dealt with regulatory compliance, international tax structures, and ESG metrics.

In September 2023, DoorDash transferred from NYSE to Nasdaq, and in December 2023 was added to the Nasdaq-100 index. These technical moves signaled something deeper: DoorDash was no longer a startup but an established technology company. With establishment came different expectations—consistent profitability, predictable growth, corporate responsibility.

The company also faced existential questions about its social impact. Were they enabling small businesses or extracting value from them? Were they providing flexible work opportunities or exploiting vulnerable workers? Were they increasing access to food or contributing to social isolation? Academic studies provided conflicting answers, but the questions persisted.

The path forward required threading an impossible needle. DoorDash needed to maintain growth while achieving profitability, support restaurants while charging sustainable fees, provide good driver earnings while controlling costs, and expand internationally while navigating local regulations. Each stakeholder group had conflicting interests, and satisfying one often meant disappointing another.

By 2024, a new equilibrium emerged. DoorDash reported its first annual profit, achieving what many thought impossible. The company had survived its controversies, evolved its model, and emerged stronger. But the scars remained—in strained driver relations, regulatory constraints, and the perpetual tension between growth and profitability.

The evolution from startup to corporation was complete. The company that had started with four friends delivering Thai food had become a complex organism navigating the intersection of technology, labor, commerce, and society. The challenges they faced weren't just business problems anymore—they were societal questions about the future of work, the nature of employment, and the role of technology platforms in local economies.

IX. Playbook: Strategic & Operational Lessons

The conference room at Sequoia Capital, 2018. Alfred Lin was grilling Tony Xu about DoorDash's seemingly irrational strategy. "You're telling me you spent three months in Charlotte, North Carolina, personally running operations, when you could have been fundraising or expanding to five new cities?" Tony's response would become Silicon Valley legend: "The best investment we ever made was doing things that don't scale until we absolutely had to scale them."

This philosophy—tactical patience combined with strategic urgency—defined DoorDash's playbook. While competitors rushed to be in every major market, DoorDash would enter a single market and refuse to leave until they had 50% market share. They called it "market by market dominance," but it was really about understanding that in local commerce, depth beats breadth every time.

Lesson 1: Start With Operational Excellence, Not Technical Innovation

DoorDash's founders delivered the first 100 orders themselves. Not 10, not 50, but 100. They wanted to feel every friction point, understand every failure mode. They discovered that parking was often the biggest time sink, that restaurant kitchens had rhythms, that customer anxiety peaked not when food was late but when they didn't know it was late. These insights, gained through sweat rather than code, became their competitive advantage.

Lesson 2: Density Is Destiny

The unit economics of delivery only work with density. DoorDash understood this mathematically: every additional order in a geographic area made all previous orders more profitable. Shorter distances between deliveries, better driver utilization, faster delivery times—everything improved with density. So they chose concentration over expansion, dominating Palo Alto before touching San Francisco, owning suburban Dallas before entering Houston.

Lesson 3: The Power of the Unsexy Markets

While Uber Eats and Postmates fought bloody battles in Manhattan, DoorDash quietly dominated Fresno, Bakersfield, and Plano. These weren't markets that venture capitalists visited or tech journalists wrote about, but they had better unit economics—longer distances meant higher delivery fees, less competition meant lower customer acquisition costs, and suburban families ordered larger, more profitable orders than urban singles.

Lesson 4: Build for Three Stakeholders Simultaneously

Every decision had to work for consumers, merchants, and drivers—their three-sided marketplace. When competitors optimized for one side (free delivery for consumers, or higher pay for drivers), DoorDash optimized for balance. They understood that breaking the economics for any one side would eventually break the entire system.

Lesson 5: Timing Beats Technology

DoorDash wasn't first (GrubHub), wasn't most funded initially (Uber Eats), wasn't most technically sophisticated (anyone else). But they had perfect timing—entering just as smartphones became ubiquitous, as millennials entered peak earning years, as restaurants began accepting technology. They rode waves rather than creating them.

Lesson 6: Capital Is a Weapon, Not a Solution

When SoftBank invested $535 million in 2018, DoorDash could have done what every other SoftBank portfolio company did—burn cash for growth at any cost. Instead, they used capital strategically: to build density in existing markets, to acquire complementary capabilities (Caviar for premium, Wolt for international), to extend runway during battles of attrition. They understood that in a negative gross margin business, growing faster just meant losing money faster unless you fixed unit economics first.

Lesson 7: Subscription Changes Everything

DashPass transformed DoorDash from a transactional business to a subscription business. Customers went from choosing DoorDash for each order to pre-committing to the platform. Order frequency increased 5x, retention improved 3x, and customer lifetime value made acquisition costs sustainable. The subscription model proved that convenience, packaged correctly, was worth paying for in advance.

Lesson 8: Multi-Brand Strategy for Multi-Segment Markets

Keeping Caviar separate rather than integrating it seemed inefficient, but it was brilliant market segmentation. A Michelin-starred restaurant would never join "DoorDash," but they'd proudly be on Caviar. A price-conscious family would balk at Caviar's fees but happily use DoorDash. Different brands allowed different positioning, pricing, and operations while sharing backend infrastructure.

Lesson 9: International Expansion Through Acquisition, Not Replication

Rather than trying to replicate their U.S. playbook internationally, DoorDash bought Wolt and kept their team intact. They understood that food delivery is inherently local—payment methods, restaurant relationships, cultural expectations all vary. Buying local expertise was faster and more likely to succeed than trying to impose an American model globally.

Lesson 10: Embrace Operational Complexity as a Moat

While competitors tried to simplify operations through technology, DoorDash embraced complexity. Different commission rates for different restaurants, multiple delivery options (standard, scheduled, group), various subscription tiers—each added operational burden but also made it harder for competitors to replicate their model. Complexity, managed well, became competitive advantage.

The Meta-Lesson: Patient Capital in Impatient Markets

DoorDash's ultimate insight was understanding the temporal dynamics of their market. In the short term (1-2 years), whoever spent most would win share. In the medium term (3-5 years), whoever had best unit economics would survive. In the long term (5-10 years), whoever built the strongest local network effects would dominate. They optimized for the long term while surviving the short and medium term.

The playbook wasn't about grand strategy but about thousands of small operational decisions made correctly. Do you pay drivers per delivery or per hour? (Per delivery, but with guarantees.) Do you charge restaurants a flat fee or percentage? (Percentage, but negotiable based on volume.) Do you expand to a new city or deepen penetration in existing ones? (Deepen first, always.)

These decisions, individually small, collectively created a system that competitors couldn't match. DoorDash didn't win because they were smarter or better funded or first to market. They won because they understood that in local commerce, operational excellence beats strategic brilliance every time. The best strategy is the one you can actually execute, and DoorDash built their entire company around execution.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case & Future Outlook

The investment committee sits around the mahogany table. August 2025. DoorDash trades at $248 per share, a market capitalization of $108.23 billion, up 138% in the past year. The question on everyone's mind: Is this the beginning or the end?

The Bull Case: Platform Dominance in an Expanding TAM

DoorDash commands 65-67% of the U.S. food delivery market, a share that has only grown since the pandemic. This isn't just market leadership—it's approaching monopolistic dominance in many local markets. In suburban Dallas, Phoenix, and dozens of other metros, DoorDash is effectively the only option for restaurant delivery.

The total addressable market continues expanding beyond anyone's wildest projections. Food delivery penetration in the U.S. remains under 15% of total restaurant sales, compared to 30%+ in markets like South Korea and China. Grocery delivery, where DoorDash is rapidly gaining share, represents a $1.2 trillion U.S. market with less than 10% online penetration. Convenience, alcohol, retail—each vertical adds hundreds of billions in TAM.

DoorDash reported its first annual profit in 2024, after two years of cost cutting drives. This wasn't a one-time anomaly but the result of structural improvements: better driver utilization through AI dispatch, higher take rates from reduced competition, and operating leverage from scale. Contribution margins in mature markets now exceed 30%.

The subscription model has transformed unit economics. 22 million users subscribe to DashPass and Wolt+, generating predictable monthly revenue regardless of order frequency. These subscribers order 4-5x more often than non-subscribers and have 70% lower churn rates. The lifetime value to customer acquisition cost ratio (LTV/CAC) for DashPass members exceeds 5:1 in mature markets.

International expansion through Wolt provides a decade of growth runway. European food delivery penetration lags the U.S. by 3-5 years. DoorDash can apply its playbook—proven through brutal U.S. competition—to markets with less sophisticated competitors. The company operates in 27 countries with room to expand to 50+.

The platform strategy is working. DoorDash Drive (white-label delivery), DoorDash Storefront (restaurant websites), and advertising products generated over $1 billion in high-margin revenue in 2024. These aren't delivery revenues—they're software revenues with 70%+ gross margins. As restaurants increasingly rely on DoorDash for customer acquisition, these revenues could 10x.

Autonomous delivery will eventually transform unit economics. DoorDash's partnerships with Nuro, Cruise, and others position them to capitalize when the technology matures. Removing driver costs—roughly 60% of delivery costs—would make even $5 orders profitable. The company that controls demand when autonomous delivery arrives will capture extraordinary value.

Network effects strengthen daily. More restaurants attract more customers attract more drivers, creating a virtuous cycle competitors can't break. DoorDash processes more orders in a day than most competitors do in a month. This scale advantage in data, operations, and economics is insurmountable.

The Bear Case: Structural Challenges in a Commoditized Market

The profitability is illusory. DoorDash achieved profitability only by cutting growth investments, reducing driver incentives, and benefiting from temporary pandemic dynamics. Any serious competitive threat would force them back into loss-making customer acquisition and driver subsidies. Uber could reignite the subsidy wars tomorrow.

Regulatory risks are existential. California's AB5 nearly forced driver reclassification. New York's minimum wage laws added $2 per order in costs. If drivers become employees nationally, the business model breaks entirely. Labor costs would double, flexibility would disappear, and the entire gig economy premise would collapse.

Customer loyalty doesn't exist. Despite DashPass, customers maintain multiple delivery apps and switch based on promotions. A Bernstein survey found 67% of delivery customers use multiple platforms monthly. There's no moat in food delivery—it's a commodity service where price and speed are the only differentiators.

Restaurant relationships are adversarial. Every basis point of take rate is a battle. Restaurants view DoorDash as a necessary evil, not a partner. As soon as a viable alternative emerges—whether direct delivery, ghost kitchens, or new aggregators—restaurants will abandon DoorDash. The 30% commission rates are unsustainable when restaurants operate on 5% margins.

The growth story is exhausted. U.S. food delivery penetration has plateaued. International expansion is expensive and uncertain—Europe has entrenched competitors like Just Eat and Deliveroo. New verticals like grocery face different economics and established competitors like Instacart and Amazon. Where does growth come from at a $100+ billion valuation?

Competition from Big Tech looms. Amazon has unlimited capital and logistics expertise. Google could leverage Maps and Search to disintermediate delivery apps entirely. Apple could integrate delivery into the iPhone experience. Any of these companies could destroy DoorDash's economics overnight by accepting break-even margins.

The fundamental economics remain broken. Even at scale, even with market dominance, food delivery generates single-digit margins at best. This isn't a software business with 80% gross margins—it's a logistics business with all the associated costs and complexities. The terminal value of a low-margin logistics business doesn't justify the current valuation.

Cultural backlash is building. Gig economy exploitation, restaurant commission complaints, traffic congestion from delivery vehicles, the environmental impact of single-use packaging—DoorDash has become a symbol of everything wrong with modern capitalism. This ESG risk is real and growing.

The Verdict: A Knife-Edge Balance

At $108 billion market cap, DoorDash trades at roughly 10x 2024 revenue and 50x EBITDA. These multiples assume continued growth, margin expansion, and successful international expansion. Any disappointment—a competitor breakthrough, regulatory crackdown, or growth deceleration—could cut the valuation in half.

Yet the strategic position is undeniable. DoorDash owns the demand layer for local commerce in America. Every restaurant, grocery store, and retailer must work with them. This market power, properly monetized, could generate enormous value over the next decade.

The investment case hinges on a simple question: Is food delivery a feature or a company? If it's a feature—something Amazon or Google eventually subsumes—DoorDash is overvalued. If it's a company—a complex operational business requiring specialized expertise—DoorDash could be the next $500 billion platform.

The future likely lies between these extremes. DoorDash will remain dominant but face margin pressure. Growth will continue but decelerate. International expansion will succeed partially. The company will generate substantial cash flows but never achieve software-like margins. In this scenario, DoorDash is fairly valued—neither a screaming buy nor an obvious short.

The convenience economy thesis remains intact. Consumers, once accustomed to on-demand delivery, rarely revert. DoorDash has successfully inserted itself into the daily routines of millions. That habitual usage, combined with operational excellence and market dominance, provides a foundation for long-term value creation—even if the path forward is narrower than bulls hope and less catastrophic than bears predict.

XI. Epilogue & Reflections

The Stanford campus, August 2025. Tony Xu walks past the engineering building where, twelve years earlier, he and his co-founders built their first website. The macaroon shop on University Avenue has closed, replaced by a venture capital firm. But the Thai restaurant that received DoorDash's very first order still operates, now with a "DoorDash Preferred Partner" sticker on its window.

From this quiet beginning emerged a company that redefined local commerce. DoorDash's journey from dorm room to Fortune 500 (ranking #443 in 2024) isn't just a Silicon Valley success story—it's a meditation on what it takes to build a category-defining company in the most competitive of markets.

The fundamental question DoorDash answered wasn't about technology but about human behavior: Would people pay a premium for convenience? The answer, delivered 5 billion times and counting, was an emphatic yes. But discovering this truth required a decade of grinding through negative unit economics, regulatory battles, and competitive warfare that destroyed dozens of competitors.

What DoorDash's story reveals about platform businesses is both inspiring and sobering. The winner-take-most dynamics that everyone assumed would apply didn't quite materialize. Instead, success required street-by-street combat, market-by-market dominance, and the patience to lose money for years while building density. The platform effects were real but hyperlocal—dominance in San Francisco meant nothing in San Diego.

The lessons for founders are clear but painful. First, operational excellence beats strategic brilliance. DoorDash didn't have better technology or more funding initially—they simply executed better, thousands of small decisions compounding into competitive advantage. Second, timing matters more than being first. DoorDash entered a crowded market but at the perfect moment when smartphones, millennials, and merchant acceptance aligned.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, building a three-sided marketplace requires a different mindset than traditional businesses. Every decision must balance the needs of consumers, merchants, and drivers. Optimize too much for one side, and the entire system breaks. This balancing act, performed daily across millions of transactions, is what separates successful marketplaces from failures.

The ongoing question—can delivery ever be truly profitable at scale?—has been partially answered. DoorDash reported its first annual profit in 2024, proving that with sufficient scale and market power, the economics can work. But this profitability required consolidation of an entire industry, elimination of most competitors, and market dynamics that may not be sustainable long-term.

The convenience economy that DoorDash helped create has fundamentally changed urban life. The ability to summon anything to your door within 30 minutes has shifted from luxury to expectation. This shift has created enormous value for consumers and generated billions in revenue, but it has also raised questions about labor, sustainability, and the kind of society we're building.

DoorDash's transformation of restaurants has been equally profound. For many establishments, delivery now represents 30%+ of revenue. The platform has become critical infrastructure, as essential as electricity or water. This dependence creates power dynamics that will shape the restaurant industry for decades. Are delivery platforms partners or parasites? The answer, like most things in DoorDash's story, depends on your perspective.

The human cost of this transformation can't be ignored. Millions of gig workers now depend on platforms like DoorDash for income, trading flexibility for uncertainty. The traditional employment model has been disrupted, but what's replacing it remains unclear. DoorDash's introduction of hourly wages and benefits represents an evolution, but the fundamental tension between flexibility and security remains unresolved.

Looking forward, DoorDash faces existential questions. Can they expand beyond food into the everything store for local commerce? Can they make international expansion work with different cultures and competitors? Can they navigate increasing regulatory scrutiny while maintaining their business model? Can they develop new revenue streams that don't depend on delivery?

The autonomous vehicle revolution looms as both opportunity and threat. If DoorDash can successfully transition to autonomous delivery, margins would transform overnight. But if a competitor gets there first, or if the technology enables restaurants to deliver directly, DoorDash's entire model could be disrupted.

The story of DoorDash is ultimately a very American story—entrepreneurial ambition meeting market opportunity, technology reshaping traditional industries, capital enabling transformation at unprecedented scale. It's a story of four students who saw inefficiency and decided to fix it, who chose the hardest possible market and won through sheer determination.

But it's also a cautionary tale about the costs of disruption. Every DoorDash delivery represents a series of trade-offs: convenience versus cost, efficiency versus employment, technology versus tradition. The company has created enormous value, but the distribution of that value remains contentious.

As we reflect on DoorDash's first decade as a public company, one thing becomes clear: they've built something essential. Love it or hate it, DoorDash has become infrastructure for modern life. The company that started by delivering Thai food to Stanford students now shapes how millions of people eat, how hundreds of thousands earn income, and how local commerce functions.

The ultimate judgment of DoorDash won't come from stock prices or market share metrics. It will come from whether they've made life genuinely better—for consumers, for merchants, for workers, for communities. That verdict remains unwritten, awaiting the next chapter of a story that's far from over.

XII. Recent News

[Section reserved for breaking news and recent developments - to be populated with current events at time of publication]

XIII. Links & References

Essential Resources:

- DoorDash Investor Relations: ir.doordash.com

- SEC Filings (S-1, 10-K, 10-Q): sec.gov/edgar

- Y Combinator Profile: ycombinator.com/companies/doordash

- Fortune 500 Ranking: fortune.com/company/doordash

Key Academic Papers:

- "The Economics of Food Delivery Platforms" - Harvard Business School

- "Gig Economy and Labor Classification" - Stanford Law Review

- "Network Effects in Local Marketplaces" - MIT Sloan

- "Platform Competition Dynamics" - Wharton Research

Books for Further Reading:

- "The Everything Store" by Brad Stone (Amazon's platform strategy)

- "Super Pumped" by Mike Isaac (Uber's competitive playbook)

- "Blitzscaling" by Reid Hoffman (Scaling strategies)

- "Platform Revolution" by Parker, Van Alstyne, and Choudary

Notable Interviews & Profiles:

- Tony Xu at Stanford GSB (View From The Top, 2020)

- "How I Built This" NPR episode with Tony Xu

- Sequoia Capital's investment memo (leaked 2018)

- John Doerr's "Measure What Matters" (DoorDash case study)

Industry Reports:

- Second Measure Food Delivery Market Share Reports

- Edison Trends Delivery Industry Analysis

- McKinsey "Future of Food Delivery" (2023)

- Bernstein "Gig Economy Deep Dive" (2024)

Regulatory Documents:

- California AB5 Full Text and Analysis

- NYC Int 2311-2021 (Minimum Pay for Delivery Workers)

- EU Platform Workers Directive

- FTC Gig Economy Report (2020)

Competitor Resources:

- Uber Investor Relations (Uber Eats segment)

- Just Eat Takeaway.com Annual Reports

- Grubhub/Seamless Historical Financials

- Deliveroo Prospectus and Updates

Note: This article represents analysis based on publicly available information through August 2025. It is intended for educational and informational purposes only. The author maintains no position in DoorDash securities and this should not be construed as investment advice.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music