Coherent Corp (COHR): The Pick & Shovel of the AI Era

I. Introduction: The "Arms Dealer" of the Future

Picture the great data center construction boom of the 2020s. Somewhere in the high desert of Nevada, or on a windswept expanse in Iowa, a warehouse the size of a small city block hums with the steady roar of compute. Inside, NVIDIA’s H100 GPUs chew through the math behind the next breakthrough in artificial intelligence.

The GPUs get the glory. But they’re useless without the plumbing.

In an AI cluster, trillions of bits have to move constantly—chip to chip, rack to rack, building to building. And the old workhorse of the last century, copper, runs headfirst into physics. Over distance and at high speeds, electrical signals degrade. Heat goes up. Power gets wasted. Latency piles on. At some point, you stop fighting electrons and you switch to photons: tightly controlled light racing through glass fiber.

Enter Coherent.

If some competitors look like precision laser specialists, Coherent looks like an industrial machine: built to manufacture at scale. With roughly a quarter of the optical transceiver market, it’s often the volume leader—the company you call when you don’t need a lab sample, you need a flood of production units, fast. Hyperscalers like Microsoft don’t win by having the best transceiver in a slide deck. They win by deploying hundreds of thousands of the right transceiver on time. Coherent has become one of the few players with the manufacturing depth to do that.

And it’s not just assembly. Coherent is vertically integrated in a way that’s increasingly rare. It doesn’t only bolt together modules; it makes critical pieces upstream too—wafers, lasers, and other components that ultimately become the finished transceiver.

But that’s just one pillar.

Zoom out and the company’s footprint is even more interesting. Coherent sits underneath multiple defining technology waves at once. It helps move the world’s data, yes—but it also makes the materials that are reshaping electric power. Silicon carbide, a compound so hard it’s often compared to diamond, is becoming a cornerstone of modern power electronics. It enables higher efficiency, higher voltage, and better thermal performance—exactly what EV drivetrains and fast-charging infrastructure demand. Meanwhile, Coherent’s lasers show up everywhere from cutting smartphone screens to welding car chassis. AI, cloud, 5G, electric mobility: all roads keep circling back to the same toolbox.

Now for the twist that makes this story worth telling.

The Coherent you see today—Coherent Corp.—is wearing a famous name, but it’s not originally the company that built that name. Modern Coherent is, in reality, II-VI Incorporated: a quietly formidable materials science company from rural Pennsylvania. In 2022, II-VI acquired the legacy Coherent, Inc., and the combined company took the Coherent brand while keeping II-VI’s founding date. The result is a corporate identity switcheroo: the brand says “California laser royalty,” but the DNA is “Pennsylvania crystal growers who rolled up photonics.”

So this isn’t just a laser company. It’s a story about compound semiconductors, crystal growth, and strategic patience—about a business that spent decades getting good at the hardest, least glamorous part of modern tech: materials.

II-VI was founded in 1971 by Carl Johnson and James Hawkey. The name “II-VI” comes straight from the periodic table: the company started with compounds made from elements in groups II and VI, beginning with cadmium telluride. It’s the kind of origin story that sounds obscure until you realize it created the foundation for a global photonics platform.

The theme here is simple, and it keeps paying off: Materials matter. We’re moving from the electronic age, where electrons carry information and power, into the photonic age, where photons carry information at the speed of light. That shift doesn’t happen because someone writes better software. It happens because someone learns how to grow better crystals, fabricate better lasers, build better optical components, and then manufacture them reliably at massive scale.

Only a couple decades ago, the fastest mainstream optical transceivers moved data at 10G. Today, more than half of Coherent’s datacom revenue comes from transceivers running at 200G and above. That leap requires new materials, new architectures, and ruthless process discipline. Coherent has spent half a century building exactly that capability.

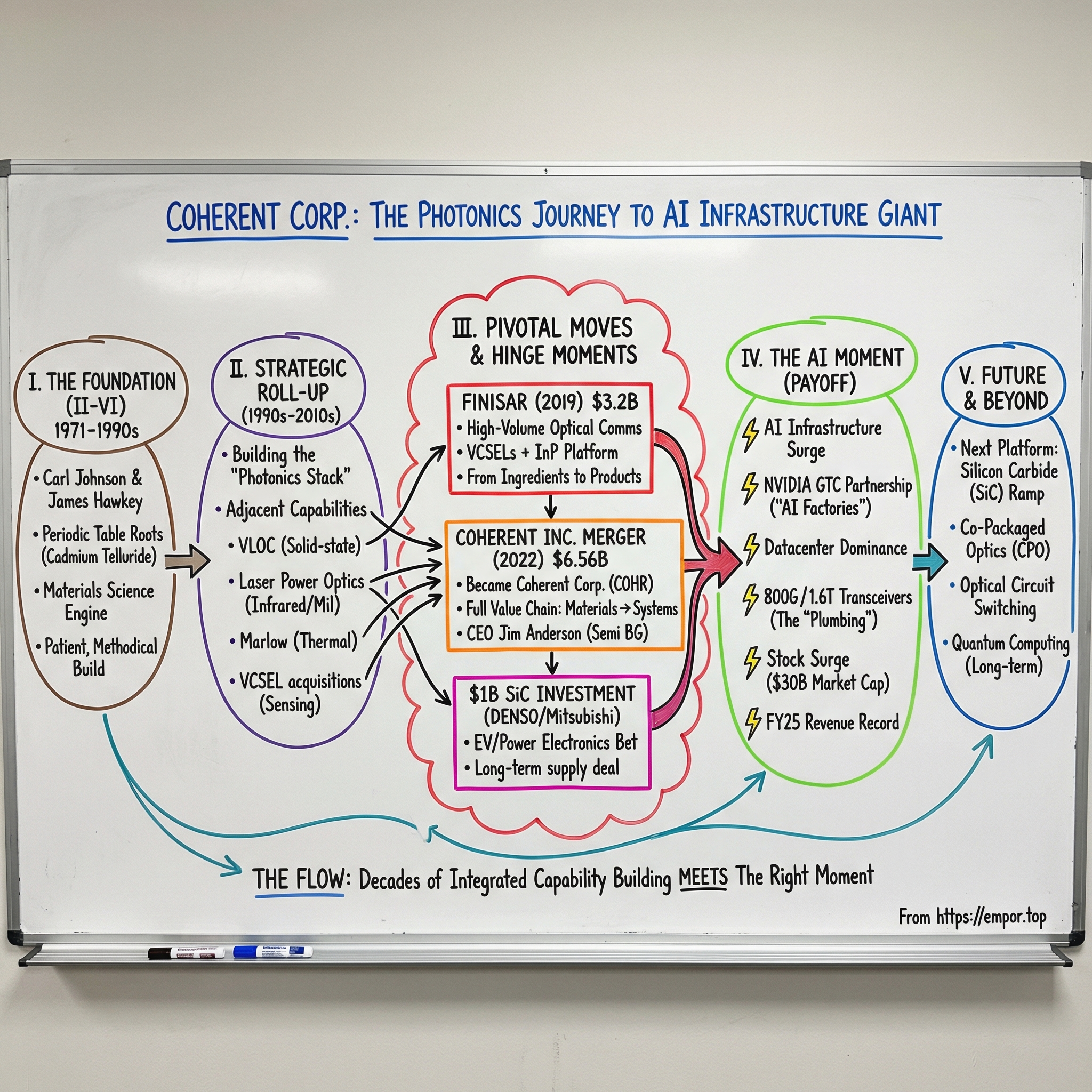

What follows is the arc from a Pennsylvania garage in 1971, through a dramatic three-way bidding war in 2021, to the Jim Anderson turnaround playing out today. Along the way, we’ll see why growing crystals can feel closer to alchemy than manufacturing, why the Finisar acquisition was a guppy-swallowing-whale moment, and why Coherent has become one of the purest “pick and shovel” plays on the AI buildout—selling the photonic infrastructure that makes the whole thing work.

II. The Origins: Saxonburg & The Periodic Table

This story doesn’t start in Silicon Valley or along Boston’s Route 128. It starts in Saxonburg, Pennsylvania—a town of fewer than two thousand people, about twenty-five miles north of Pittsburgh. Rolling hills, farms, light industry. The kind of place where you’d expect machine shops and feed stores, not the foundation of a future photonics powerhouse.

For Carl J. Johnson, though, Saxonburg became the center of gravity for almost his entire professional life. A rival once described him as “a real capable scientist and manager,” which, in this business, is basically the highest compliment you can get.

Johnson’s path was pure engineering pedigree: a bachelor’s from Purdue, a master’s from MIT, and a Ph.D. in electrical engineering from the University of Illinois in 1964. He did a short tour at Bell Labs—two years on the technical staff—then moved to Essex International, an automotive products maker, where he spent five years running R&D. And then, still in his late twenties, he did the thing that would define the next half century: in 1971, he started II-VI.

The spark was unusually specific. Johnson’s Ph.D. work depended on cadmium telluride crystals. The problem was, you couldn’t just order them. Commercial suppliers couldn’t provide the purity and quality he needed. So Johnson did what the best materials people always do: he stopped asking and started making. He decided to grow his own crystals.

That choice—part stubbornness, part vision—was the company.

Johnson later explained that he and the late James E. Hawkey founded II-VI because the infrared optical materials available to the laser industry at the time couldn’t survive what was coming: the kilowatt-level power demands projected by the new generation of carbon-dioxide (CO2) laser developers. The optics were the bottleneck. If lasers were going to get dramatically more powerful, somebody had to invent the materials that wouldn’t crack, cloud, or burn out.

Even the name II-VI was a flag planted in the ground. It wasn’t a brand brainstorm; it was chemistry. Groups II and VI of the periodic table—cadmium, zinc, tellurium, selenium—form compounds like cadmium telluride (CdTe) and zinc selenide (ZnSe), the raw ingredients for the infrared optical materials Johnson wanted to commercialize.

This wasn’t Silicon Valley silicon. These were specialized crystals with exotic properties—materials that could enable high-power industrial lasers, support infrared imaging for defense systems, and, eventually, sit upstream of the components that move information through the modern internet. The company’s identity wasn’t “we build lasers.” It was “we build the materials lasers require.”

II-VI’s first products were lenses, windows, and mirrors for CO2 lasers—the industrial workhorses of the era, used for cutting and processing materials. But those systems were only as good as their optics, and the optics had to withstand punishing heat and power. Zinc selenide became the breakthrough: transparent in the infrared, and durable enough to take on kilowatt-class beams. II-VI carved out a niche by doing the hard part reliably—growing ZnSe crystals with the purity and size the market needed.

And here’s the key: growing compound semiconductor crystals is not like making silicon chips. There’s no Moore’s Law for crystal growth. You can’t just “scale” by stamping out more units. It’s closer to winemaking than manufacturing. Crystals grow slowly—over days, weeks, sometimes months—under tightly controlled temperature, pressure, and chemical conditions. Tiny changes can turn a batch from usable to worthless.

That’s why II-VI’s advantage wasn’t a patent you could read or a machine you could buy. It was know-how. Anyone could purchase a furnace and attempt to grow zinc selenide. Very few could hit the yields, consistency, and purity that industrial customers demanded. The recipes lived in the organization: temperature ramps, seed timing, impurity control, handling techniques—the kind of tacit knowledge that gets built one hard-won iteration at a time, then passed down.

By the mid-1980s, the business had turned that craft into something durable. II-VI was profitable and growing, reaching about $10 million in sales by fiscal 1987, with roughly 40% of revenue coming from international customers. In 1978, the company acquired its Saxonburg facility outright—an unglamorous move, but exactly the kind that signals permanence and supports expanding production.

Then came a milestone: II-VI went public in 1987. Johnson said the IPO proceeds let the company expand its zinc selenide manufacturing capacity—fuel for the core engine. The timing was almost cinematic: the offering closed just days before the October 1987 stock market crash. The market fell apart, but II-VI already had the cash in the bank.

After the IPO, Johnson still owned 31% of the company, and he steered II-VI into the 1990s—a decade when growth accelerated and acquisitions began to play a larger role, especially after management resolved issues in one of the company’s key markets.

Through it all, the culture that formed in Saxonburg stayed consistent: frugal, engineering-led, and patient. These were the farmers of the tech world, growing crystals over long cycles instead of chasing quick hits. Overhead stayed lean. Profits went back into R&D. Flashy spending was never the point.

And that culture had strategic consequences. II-VI wasn’t going to win by out-marketing anyone. It was going to win by becoming the vendor customers couldn’t replace—the company that could deliver mission-critical materials, on spec, again and again.

Those were the seeds planted in the 1970s: deep materials expertise, process discipline, and a bias toward being indispensable instead of famous. In time, they would grow into a global photonics platform. But first, II-VI needed a leader who could take that patient, crystal-growing machine and aim it at something much bigger.

III. The Quiet Compounder & The Mattera Era

By the early 2000s, Carl Johnson had been steering II-VI for more than three decades. The company was no longer a niche crystal shop. It had grown into a diversified specialty materials business with thousands of employees and a global customer base. But the next chapter—something bigger than steady expansion—needed a different kind of leadership.

That leader was Dr. Vincent D. “Chuck” Mattera, II-VI’s third CEO in nearly five decades. The founder’s wife once described him as the perfect blend of Johnson and Francis Kramer, the company’s first two CEOs: highly technical, highly operational. Mattera first entered the II-VI orbit in 2000 as a board member, brought in for his semiconductor laser expertise. Four years later he joined full-time as a vice president, after a 20-year career that began inside an AT&T Bell Laboratories division.

Mattera’s mix was unusual: deep engineering credibility paired with real appetite for scale. When he joined in 2004, II-VI had roughly $150 million in sales. By the time he stepped down as CEO in 2024, sales had grown more than thirty-fold. But that kind of transformation didn’t come from one lucky break. It started with a moment of uncertainty—then a choice to lean into it.

Mattera began asking a question that sounds simple but was existential for II-VI: what did the rise of fiber lasers mean? Opportunity, threat, or both?

He couldn’t get a clear answer. So Johnson and Kramer told him to go find out. Mattera came back with a conclusion that set the tone for the era: “It may be a threat, but for sure it’s an opportunity.”

Fiber lasers were a real potential disruption. II-VI’s early growth engine had been CO2 lasers, which drove demand for zinc selenide optics. Fiber lasers were different—different architectures, different material needs, different supply chains. The conservative move would have been to defend the legacy business and hope customers stayed put. Mattera chose offense.

As he later put it, the board encouraged him to define a path to diversify II-VI and build sustainable advantage in markets the company wasn’t yet in. And he understood the constraint that makes photonics so different from software: you can’t just will new materials into existence on a startup timeline. These technologies can take decades to mature. If II-VI wanted a broader portfolio within a realistic timeframe, it would have to buy its way there—acquiring teams and capabilities that had already absorbed the years of R&D risk.

That became the strategic cornerstone of the Mattera era: accelerate diversification through acquisitions, then use II-VI’s manufacturing discipline and materials know-how to scale what it bought.

Over the next decade, he worked to position II-VI around the fiber laser ecosystem at multiple layers—higher and lower levels of integration—without going straight at the dominant incumbent, IPG Photonics, in finished systems. Mattera later said the approach came straight out of Sun Tzu: don’t attack the enemy head-on. Go around the problem.

So instead of trying to out-IPG IPG, II-VI built leverage where it already had an advantage: components, materials, coatings, specialty optics—the stuff fiber laser manufacturers needed no matter whose logo was on the finished box. Vertical integration became more than a buzzword. It was the playbook: don’t just assemble value downstream; own critical inputs upstream.

The acquisition cadence reflected that ambition. After Mattera joined in 2004, II-VI completed more than 20 acquisitions, each one intended to extend reach, deepen the technology and IP portfolio, and broaden the customer base. And by the end of the 2010s, the company was preparing for its biggest leap yet: the planned acquisition of Finisar, a similar-sized company with about $1.3 billion in annual revenue. The platform-building phase was about to collide with a true “guppy swallowing the whale” moment.

But before that, there was an acquisition that quietly changed the geometry of the whole company: Photop Technologies in 2010. Mattera called it a platform in China—a way into a market that was scaling fast and investing heavily. When II-VI bought Photop, it had $66 million in trailing twelve-month sales. Years later, Mattera said that business had grown to over $600 million in annual revenue and had become a major backbone of II-VI’s communications segment.

The timing mattered. During the Great Recession, growth in the U.S. and Europe collapsed. China, by contrast, kept expanding, with the government pushing stimulus into communications infrastructure. II-VI could have waited out the downturn. Instead, it bought a foothold in the fastest-growing market and rode the buildout.

Then came the iPhone moment—the kind of event that makes a company’s decade of preparation suddenly look inevitable in hindsight.

In 2017, Apple launched the iPhone X with Face ID, built on structured light. At the heart of it were VCSELs: vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers. These tiny semiconductor lasers, operating in infrared, project a pattern onto your face; sensors read the reflection and build a 3D map in milliseconds. The iPhone X used multiple VCSEL dies across its proximity sensor and Face ID module, and the result was a market shock. VCSEL demand surged, helping propel overall VCSEL market revenue to roughly $330 million that year.

II-VI had been laying the groundwork. In 2016, the company acquired epitaxial growth and device fabrication capabilities on 6-inch gallium arsenide wafer platforms, then worked to transfer, scale, and qualify VCSEL manufacturing processes on those lines. As analyst Mark J. Lourie noted, II-VI became the only vertically integrated 6-inch wafer VCSEL manufacturer, and in the second half of 2017 it significantly ramped VCSEL production for 3D sensing.

When Apple needed VCSELs at massive scale, II-VI was ready. Apple said II-VI’s VCSELs helped power features like Face ID, Memoji, Animoji, and Portrait mode selfies, and also noted work with II-VI on lasers used in the LiDAR scanner for augmented reality and improved autofocus in low-light conditions.

Strategically, this was a new identity. II-VI wasn’t just supplying industrial optics anymore. It was now embedded in consumer electronics at one of the most demanding volumes and quality bars on Earth. Billions of phones later, vast numbers of people had II-VI technology in their pockets without ever knowing the company existed.

And that was the whole Mattera approach in one snapshot: own hard-to-replicate materials capabilities, buy your way into adjacent technologies, then be the supplier that can actually deliver when the market turns from prototypes to mass production.

To investors, the outline of the strategy was clear—even if the stock didn’t always reward it in the moment. II-VI was assembling something bigger than any one product line: a platform spanning industrial, communications, and consumer end markets. The open question was integration. Could all these pieces become one machine, or would they remain a collection of parts?

That question was about to be tested in spectacular fashion with the next acquisition.

IV. Inflection Point #1: The Finisar Acquisition (2018)

To understand why II-VI’s acquisition of Finisar mattered, you have to understand the physics of the modern internet.

When you click a link, stream a video, or send a prompt to ChatGPT, your request eventually hits a hard boundary: at some point, electrons can’t do the job efficiently anymore. The signal has to become light, travel through fiber, and then turn back into an electrical signal on the other end.

That conversion happens inside optical transceivers. They’re the unsexy plugs that make the cloud work. And in 2018, Finisar was one of the most important companies in the world at making them.

Finisar was founded in 1987 in Menlo Park by Frank Levinson and Jerry Rawls. It went public in 1999, right as optical networking mania peaked. The company’s early focus was straightforward: optical transceivers for high-speed networks, back when “the internet” was still something you explained to your parents.

But Finisar wasn’t just a transceiver assembler. It built deep technical muscle in the core building blocks—especially VCSELs. In 1997, it launched the first VCSEL-based transceiver products, and that expertise would come roaring back two decades later when 3D sensing exploded.

By 2018, two waves were cresting at the same time.

First: cloud computing. Data centers were ballooning in size and number, and every new server rack meant more optical links. Second: consumer 3D sensing. Finisar became a major beneficiary of Apple’s push into Face ID, including a $390 million investment from Apple to expand VCSEL production capacity.

II-VI saw what that meant. It had spent decades becoming world-class at materials and components. Finisar sat downstream, where those materials turned into the modules that hyperscalers actually buy by the hundreds of thousands. Put the two together and you don’t just sell parts into photonics—you become infrastructure for the internet.

In late 2018, II-VI announced it would acquire Finisar in a cash-and-stock deal valued at about $3.2 billion.

This was the guppy swallowing the whale moment. Finisar’s annual revenue—about $1.3 billion—was roughly the same as II-VI’s. II-VI wasn’t picking up another tidy $50 million tuck-in. It was attempting to merge with a peer and come out the other side as something much bigger: a photonics platform with transceivers at its center.

Mattera framed the logic in the way he always did: if you believe these markets take decades to develop, you don’t wait around for capability to appear. You buy it, integrate it, and scale it with your process discipline. But he also admitted what everyone could see: the debt load was daunting. II-VI was taking on roughly $2 billion of debt to make the deal happen. “It’s a staggering and steep slope to climb,” he said.

Wall Street’s reaction was immediate and brutal. II-VI’s stock fell by roughly 20% on the announcement. Analysts weren’t debating whether Finisar was a quality asset—they were asking whether II-VI could actually digest it. That “indigestion” narrative, the idea that II-VI had finally bitten off more than it could chew, started here.

The deal took time to close. II-VI completed the acquisition in September 2019, after receiving regulatory clearance from China’s State Administration for Market Regulation. The company financed it in part with about $1.9 billion in cash from new loans and laid out a plan to achieve significant cost savings over the following years.

Integration was hard—as it always is when you stitch together two global manufacturing organizations with overlapping product lines, fabs, and cultures. But the strategic shift was unmistakable.

After Finisar, II-VI was no longer primarily an industrial materials company with some photonics exposure. It was a communications infrastructure heavyweight, placed directly in the path of the data center build-out that would define the next decade.

For investors, Finisar was also a bright signal about management’s worldview. Mattera had long argued that materials technologies take decades to mature. With Finisar, he turned that philosophy into a multi-billion-dollar bet: that optical connectivity would only become more central, and that owning the transceiver layer—at scale—would be worth the pain.

As AI workloads began to push bandwidth and latency requirements into overdrive, that bet started to look less like recklessness and more like positioning.

But Finisar was only the warm-up. The truly dramatic fight—the one that would redefine the company’s name and identity—was still ahead.

V. Inflection Point #2: The Battle for Coherent (2021-2022)

In January 2021, with the world still living under pandemic uncertainty, a very different kind of contagion spread through photonics: deal fever.

Lumentum Holdings announced it would acquire Coherent, Inc. for about $5.7 billion. And this wasn’t just any target. Coherent traced its roots back to 1966 and had become one of the most storied names in lasers—scientific, industrial, and the precision tools that underpin everything from medical devices to semiconductor manufacturing. If Finisar was the transceiver heavyweight, Coherent was laser royalty. On paper, a Lumentum–Coherent tie-up looked like classic industry consolidation: cleaner product overlap, a straightforward strategic story, a bigger combined platform.

Then the process stopped being straightforward.

On January 19, Coherent, Inc. said it had agreed to be acquired by Lumentum for $100 per share in cash plus 1.1851 shares of Lumentum stock. Within weeks, MKS Instruments showed up with an unsolicited bid—kickstarting a public, months-long bidding war that soon pulled in II-VI as the third contender. Offer after offer hit the tape, generally pushing the price up while shifting the mix toward more cash and less stock. At some point along the way, MKS dropped out.

The spectacle was rare: a true three-way fight playing out in the open, with all the messy incentives exposed. Coherent made lasers and related products across medical and scientific equipment, industrial applications, and semiconductor manufacturing—exactly the kinds of end markets the bidders cared about. And because there was enough overlap in any pairing, everyone knew antitrust review wouldn’t be trivial no matter who won.

The numbers climbed fast. MKS came in around $6 billion, offering $115 in cash plus 0.7473 of a share of MKS stock for each Coherent share. II-VI countered at roughly $6.4 billion, offering $130 in cash plus 1.3055 shares of II-VI stock. Then II-VI raised again: about $7.01 billion, offering $220 in cash plus 0.91 shares of II-VI stock.

This is where the “Chuck factor” took over.

Lumentum arguably had the cleaner deal logic. But Mattera wanted Coherent with the same intensity he’d shown with Finisar—and he was willing to lean hard on II-VI’s balance sheet to get it. In late March, Lumentum put in a last bid of about $7.03 billion. II-VI held its $7.01 billion offer. And Coherent’s board chose II-VI anyway—agreeing to pay Lumentum a $217.6 million termination fee to walk away.

Why take the slightly lower headline number? Coherent’s board said it weighed the benefits and risks of both proposals, including synergy potential and long-term opportunity. The implication was clear: II-VI’s broader materials-and-components platform offered a longer runway for value creation than a more narrowly framed laser consolidation.

And then came the slow part.

On July 1, 2022—after the year-and-a-half saga, the bidding war, and a long antitrust review—II-VI completed its acquisition of Coherent for $6.56 billion. Alongside the closing announcement, II-VI said the combined company would be called Coherent.

That was the identity switch.

In one of the boldest branding decisions in corporate history, II-VI—the acquirer—discarded its own periodic-table name and adopted the legacy brand of the company it had just bought. II-VI Incorporated announced it would change its corporate name to Coherent Corp. and roll out a new brand identity. Mattera explained the choice simply: the name “Coherent” had a universal meaning—“bringing things together”—and he believed it would broaden recognition and ultimately drive value creation.

Unfortunately, the timing couldn’t have been more punishing.

The deal closed just as the Federal Reserve began aggressively raising interest rates. Investors who had worried about leverage during the Finisar acquisition now saw a much bigger balance sheet under a much harsher cost of capital. The market response was what you’d expect: the stock languished as concerns mounted that interest expense would swallow the upside before integration synergies could show up.

On paper, the new Coherent was enormous: more than 28,000 employees across 130 locations, serving industrial, communications, electronics, and instrumentation markets that the company pegged as a combined $65 billion opportunity.

Internally, it organized into three segments: Materials, Networking, and Lasers. The scope was breathtaking—everything from raw compound semiconductors to components and subsystems, all the way to finished laser systems.

For investors, this was the culmination of Mattera’s two-decade plan: build the broadest photonics platform in the industry. The question that hung over the combined company wasn’t whether it had the assets. It was whether it could turn that breadth into one coherent operating machine—and whether shareholders would ever see the payoff.

VI. The Three Pillars: Networking, Lasers, & Materials

To understand Coherent, you have to hold three different businesses in your head at once. They sell into different customers, fight different competitors, and run on different clocks. But together, they explain why this company sits under so many of the biggest technology waves at the same time.

Networking: The AI Bet

This is where the AI story becomes real.

As AI clusters have grown from “a lot of servers” into “a single computer the size of a warehouse,” the network has become the bottleneck. Training runs aren’t limited by how fast one GPU can calculate. They’re limited by how fast thousands of GPUs can share information—constantly shuttling gradients, activations, and weights back and forth.

Copper worked for the last era. It doesn’t work for this one. At these speeds and distances, electrons lose the fight. Photons win.

That’s why transceiver performance has become existential for hyperscalers. And it’s why Coherent’s datacom mix has already shifted: today, more than half of its datacom revenue comes from 200G-and-above transceivers. The industry has moved even faster than anyone expected. 800G is already shipping in production, and Coherent expects 1.6T to follow in the next few years. In the company’s view, within five years the opportunity for 800G and 1.6T datacom transceivers will outweigh all other transceiver types combined—pulled forward primarily by AI and machine learning.

At the sharp edge of that transition is the 1.6T-DR8 transceiver module in the OSFP form factor: eight electrical lanes and eight optical lanes, each running at 200 Gbps, for a total of 1.6 terabits per second in a single pluggable module. This design incorporates an advanced digital signal processor supplied by NVIDIA, and Coherent positions it specifically for AI and networking workloads. The module can transmit up to 500 meters over eight pairs of single-mode fiber, and it showcases Coherent’s silicon photonics technology.

If that sounds like a lot, it is. A 1.6-terabit module packs more bandwidth into a box you can hold in your hand than the early internet ever had in its spine. And it only works if you can manufacture it with brutal precision—laser performance, optical alignment, signal integrity, thermal behavior—then do it at scale, with yields that make the economics work.

Coherent has pointed to record bookings, with orders extending more than a year out, as a signal that AI networking demand isn’t just a spike—it’s becoming a backlog. The company has also described accelerating adoption of 1.6T alongside broad 800G deployments, with silicon photonics and EML-based 1.6T ramping now, and 200G VCSEL-based 1.6T expected to ramp next calendar year. Datacenter revenue grew 23% year over year in Q1, though the company said it was supply-constrained by indium phosphide (InP) lasers.

That last detail matters: Coherent doesn’t just assemble modules. It’s often constrained by the very upstream components it also makes—because those components are hard, and because the entire industry is trying to scale at once.

Coherent has also been recognized as an NVIDIA Ecosystem Innovation Partner, and it’s collaborating with NVIDIA on silicon photonics and co-packaged optics for networking switches—another step toward the next architecture for AI infrastructure.

Materials: The EV Bet

If Networking is photons, Materials is electrons—specifically the electrons you’re trying to move through an EV drivetrain without wasting energy as heat.

Coherent’s silicon carbide business is where that bet lives. In 2023, the company announced an investment that did two things at once: it brought in capital and it validated demand from some of the most serious players in automotive. DENSO Corporation and Mitsubishi Electric Corporation agreed to invest $1 billion in aggregate—$500 million each—in exchange for a combined 25% non-controlling ownership interest in the silicon carbide business. Coherent retained the remaining 75%, and later said it had closed the transaction.

The product here is silicon carbide (SiC), and the role it plays in electrification is hard to overstate. Chuck Mattera explained it this way: electrification and renewable energy get more efficient with power electronics made from SiC. That efficiency shows up as practical, tangible outcomes—smaller and lighter systems, lower power consumption, and greater driving range per charge compared with conventional silicon-based power electronics. The same logic applies beyond cars: solar and wind systems benefit too, because SiC power electronics can regulate and deliver electricity to the grid more efficiently.

And SiC is hard. Growing silicon carbide crystals is even more punishing than the zinc selenide work II-VI was built on. The process happens at temperatures above 2,000°C. Crystals grow slowly—just millimeters per day. And defects that might be tolerable in silicon can be catastrophic in SiC. The result is a market that has repeatedly faced shortages, and where high-quality supply commands premium pricing.

Market estimates Coherent cited suggest SiC could grow from about $3 billion in 2022 to about $21 billion by 2030.

Strategically, the DENSO and Mitsubishi investment mattered for three reasons. First, it injected $1 billion into the business without Coherent needing to raise public equity or add debt. Second, it tied Coherent more closely to two major automotive suppliers, aligning incentives around long-term supply. Third, it brought in partners with deep domain expertise and market visibility—helpful when you’re scaling a material that’s notoriously difficult to manufacture consistently.

Lasers: The Cash Cow

Then there’s the legacy heart of the Coherent name: lasers.

This segment is the industrial workhorse—lasers that cut, weld, drill, and mark materials across manufacturing. It’s the toolkit behind production lines in automotive, microelectronics, and industrial manufacturing more broadly. Coherent has long been prominent here, alongside players like TRUMPF, with a mix of advanced laser technologies and global reach.

It’s not as headline-grabbing as AI optics or EV materials. But it matters because it tends to generate steadier cash flows. When a manufacturer designs a production line around a specific laser platform, switching isn’t trivial. You have qualification cycles, equipment changes, operator retraining, and real risk of downtime. Those are meaningful switching costs—and they create a kind of durability you don’t always get in faster-moving tech markets.

Put the three pillars together and you get the central tension of modern Coherent. On one hand, it’s a diversified platform with exposure to multiple megatrends. On the other, it’s a complicated machine. If AI networking demand cools, maybe EV adoption accelerates. If automotive slows, industrial manufacturing might hold up. Some investors see that breadth as complexity. Others see it as resilience.

Either way, these three pillars are the operating reality Jim Anderson inherited—and the base he now has to turn into something that performs like one company, not three businesses under one ticker.

VII. The Jim Anderson Turnaround

Despite owning remarkable technology across multiple growth markets, Coherent’s stock drifted through 2023 and into early 2024. Two mega-acquisitions had left behind the usual hangover—overlapping factories, tangled product lines, and a balance sheet that looked a lot scarier once interest rates started rising. Investors didn’t just worry about debt. They worried the whole thing had become too complicated to run cleanly. The classic “conglomerate discount” settled in.

Then Coherent went and hired the kind of CEO you bring in when you want to change the narrative fast.

On June 3, 2024, Coherent appointed Jim Anderson as Chief Executive Officer and added him to the Board of Directors.

Anderson came in with more than 25 years across the technology and semiconductor world. Immediately before Coherent, he was President and CEO of Lattice Semiconductor from September 2018 to 2024. Before that, he was Senior Vice President and General Manager of AMD’s Computing and Graphics Business Group—meaning he’d already lived through one of the most famous semiconductor turnarounds of the last decade.

His reputation was straightforward: make hard choices, simplify the story, and push margins up. At Lattice, he tightened strategy, strengthened the roadmap, and drove record operating profits and gross margins for a company many had written off as a low-end commodity shop.

Wall Street got the message instantly.

Coherent’s shares jumped about 23% in one session on the news, rising from roughly $57 at the prior close to around $70. In a neat, brutal little market verdict, Lattice shares fell around 15% the same day—investors essentially pricing in that Anderson had been a meaningful part of what made Lattice work.

So what was the playbook everyone expected him to bring? Anderson has a phrase for it: “Value over Volume.”

At Lattice, that meant cutting low-margin products, narrowing focus, and putting resources behind the highest-value opportunities—even if that meant walking away from revenue. The bet at Coherent was that the same discipline could turn a sprawling photonics platform into a sharper, more profitable machine.

Early moves pointed in that direction. Coherent continued optimizing the portfolio and footprint: closing the Aerospace & Defense sale, announcing a Munich tools divestiture, and exiting 23 sites since FY 2025. The stated goal was clear—deleveraging and margin expansion toward a target model of greater than 42% gross margin.

Management also tied the operational cleanup directly to the company’s most important growth engine. Anderson highlighted strong AI-driven demand in datacenters and the launch of new optical networking products. CFO Sherri Luther emphasized cash discipline, including a $136 million reduction in debt, and framed priorities around cash management while still investing for long-term growth.

The restructuring got formal in 2025, when the company approved a plan covering site consolidations, facility moves, closures, and workforce reductions, with expected completion by fiscal year 2026. And on August 13, 2025, Coherent announced an agreement to sell its aerospace and defense business to Advent International for $400 million.

Financially, the company started to show momentum. Coherent revenue for the twelve months ending September 30, 2025 was $6.043B, a 20.8% increase year-over-year. Coherent annual revenue for 2025 was $5.81B, a 23.42% increase from 2024.

In Q3 fiscal 2025, revenue reached $1.50 billion, up 24% year over year. GAAP gross margin improved to 35.2%, up 491 basis points, and non-GAAP gross margin rose to 38.5%. Non-GAAP EPS came in at $0.91, up $0.53 from the prior year.

For investors, Anderson represented a specific kind of bet: not that Coherent needed better technology, but that it needed better execution. Chuck Mattera assembled a world-class set of assets. Anderson’s job was to make it run like a disciplined operating company—focused, simpler, and capable of turning all that photonics horsepower into sustainable margins and cash flow.

VIII. Power Analysis: Competitive Dynamics

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework is a useful way to make sense of Coherent’s strange mix of strengths: some that feel almost unassailable, and others that look uncomfortably exposed.

Process Power: The Crown Jewel

Growing compound semiconductor crystals—zinc selenide, silicon carbide, gallium arsenide—is closer to alchemy than manufacturing. As the company has put it: “II-VI focuses on materials that exhibit unique optical, electrical, thermal or mechanical properties. These materials take a long time to develop and typically enable multiple applications over time. That leads to technology that is hard for competitors to replicate and results in a healthy business that is driven by diversified and rapidly growing end markets, fueled by enabling products.”

That’s the thesis, and it’s also the moat.

Competitors can buy furnaces. They can copy equipment layouts. They can hire smart people. What they can’t buy is the accumulated, battle-tested process knowledge—the recipes, the tweaks, the intuition about why one run yields and the next one fails. In Coherent’s world, the difference between “it works” and “it doesn’t” is often invisible on a spreadsheet. It lives in the organization.

This is process power in its purest form: hard to see, hard to copy, and incredibly valuable once you’re the qualified supplier.

Scale Economies

Bain Capital, which pledged to support the II-VI merger plan, believed the combined company would benefit from being much larger than most peers in photonics. With combined annual revenues in the region of $4.1 billion, the merged entity would have exceeded the sales of MKS, Lumentum, and IPG Photonics, as well as privately owned TRUMPF.

Whether you anchor on that moment-in-time view or the larger reality today, the point holds: the acquisition strategy created the world’s largest photonics company, and scale actually matters here.

R&D can be spread across a wider base. Manufacturing footprints can run at higher utilization. And in markets where customers are trying to de-risk supply chains, “one capable vendor who can ship” often beats “three smaller vendors who might.”

Switching Costs

Once a transceiver is qualified inside a hyperscale data center, customers don’t switch casually. Qualification can mean months of testing, integration work, validation, and documentation. You don’t rip that out on a whim—especially not when downtime is measured in real money and reputational pain.

The same dynamic shows up in industrial lasers. When Coherent’s systems are embedded in a production line, switching means requalification, retraining, and the risk of disrupting throughput. Those switching costs don’t make Coherent invincible, but they do make relationships stickier than the quarterly pricing battles would suggest.

Counter-Powers: Customer Concentration

The sharpest edge against Coherent’s moats is customer concentration.

The major hyperscalers—Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Meta—buy at a scale that gives them enormous leverage. Apple’s influence over the VCSEL ecosystem is similarly concentrated. These customers can push for pricing concessions, and over time they can encourage second sources or invest in alternative paths.

Coherent benefits when it becomes indispensable. But when your biggest customers are also sophisticated, well-capitalized, and allergic to dependency, you have to keep earning the position.

Competitive Landscape

Coherent competes across several arenas at once. In broad photonics and lasers, it faces established players like IPG Photonics, Lumentum, and TRUMPF, all fighting for share in industrial applications and precision manufacturing. IPG is a major force in high-power fiber lasers and can be especially aggressive on price in markets where products are becoming more standardized.

In compound semiconductors and optical networking, the rival set shifts: Broadcom, MKS Instruments, and Wolfspeed show up more often. Wolfspeed, in particular, is a specialist in silicon carbide—a fast-expanding battleground where Coherent is also leaning in.

The broader laser optics market is consolidated, with the top five players—Coherent Corp., TRUMPF, Han's Laser Technology Industry Group Co., Ltd, IPG Photonics Corporation, and JENOPTIK AG—collectively estimated to hold roughly 35–50% share. These are global-scale companies with broad portfolios and constant investment in innovation, which makes the market competitive even when it’s consolidated.

Porter’s Five Forces Assessment

Threat of New Entrants: Low in materials (it takes decades to develop), moderate in transceivers (large capital needs, but fewer exotic process barriers).

Supplier Power: Coherent’s vertical integration lowers dependency, but certain specialty gases and equipment are still sourced from concentrated supplier bases.

Buyer Power: High among hyperscalers and Apple; more moderate among diversified industrial customers.

Threat of Substitutes: Limited for optical interconnects at these speeds; more moderate for SiC, where GaN competes in some applications.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense in transceivers; more moderate in specialty materials, where fewer suppliers are qualified.

Key KPIs for Investors

For long-term investors watching whether the Anderson-era cleanup is translating into results, two metrics matter most:

-

Non-GAAP Gross Margin: A practical read on whether Coherent is capturing value from its platform. Anderson’s target model calls for margins above 42%. Recent performance around the high-30s suggests there’s still meaningful room for improvement, and progress here would be a clear signal that portfolio pruning and execution are working.

-

Datacom Revenue Growth: The cleanest window into Coherent’s exposure to the AI infrastructure buildout. Quarterly datacom growth, year over year and sequentially, helps reveal whether demand is accelerating and whether Coherent is holding or gaining share as customers scale deployments.

IX. The Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

The AI supercycle looks real—and, more importantly, it looks structural. Every major technology company is pouring capital into AI infrastructure, and that infrastructure is bottlenecked by one thing: moving data fast enough inside and between data centers. That means optical interconnects, at huge scale.

Coherent sits right on that choke point. Its leadership in 400G and 800G modules has already made it a key supplier to hyperscalers, and the next step-change is already in view: 1.6T, and eventually 3.2T, as AI workloads push bandwidth demands higher.

The near-term bull thesis is simple: Coherent is trying to be the first mover at 1.6T. The market is still working through 800G deployments, but frontier AI models will increasingly need 1.6T-class links to keep training times from blowing out. If Coherent can ramp that product line cleanly and at volume, it likely becomes one of the main determinants of the stock over the next year.

Then there’s the Anderson angle. If Jim Anderson can run the Lattice playbook here—shrink the sprawl, stop chasing low-margin revenue, and make the factory network and product portfolio behave like one disciplined company—margin expansion becomes a very real lever. The tech base is already world-class. The value unlock is execution.

Finally, silicon carbide is the call option. With $1 billion of strategic partner investment already in the business and a market expected to compound rapidly through 2030, Coherent has meaningful exposure to electrification—even if the AI cycle wobbles.

The Bear Case

The “conglomerate discount” might not be a misunderstanding. Running Networking, Lasers, and Materials under one roof sounds elegant on a strategy slide, but in practice it means juggling three very different sets of customers, cycles, and competitive dynamics. There’s a legitimate question of whether shareholders would ultimately do better with a breakup—spinning off SiC, for example, or separating lasers from networking.

Debt is still the other shadow. Even with deleveraging, a higher-for-longer rate environment means interest expense can eat a meaningful portion of cash flow. And if a recession hit both data center spending and EV adoption at the same time, the balance sheet would feel tight again, fast.

Competition is also not standing still. New entrants and incumbents alike are investing aggressively in silicon photonics and next-generation optics. Coherent has a seat at that table, but if well-funded players like Intel, Marvell, or Broadcom drive parts of the transceiver stack toward commoditization, pricing power could erode in exactly the segment investors are counting on.

And then there’s geopolitics. Coherent’s manufacturing footprint is meaningfully concentrated in Asia, including significant operations in China. Trade tensions, export controls, and supply-chain disruptions aren’t abstract risks here—they can show up as real operational constraints.

Myth vs. Reality

Myth: Coherent is just a laser company.

Reality: Lasers are only one part of the business. Networking (transceivers) and Materials (including SiC and specialty crystals) drive much of the company’s revenue and growth narrative.

Myth: The acquisition spree created an unfocused conglomerate.

Reality: The segments share common roots in photonics and compound semiconductors, and the vertical integration can be a real advantage—if the company is run with enough operational discipline to make the pieces reinforce each other.

Myth: AI transceiver demand will fade once the initial buildout is done.

Reality: AI infrastructure still appears early in its upgrade cycle. The industry’s march from 800G to 1.6T and then 3.2T implies multiple refresh waves, not a one-time spike, as model sizes and cluster scales keep climbing.

X. Conclusion: Grading the Acquisition

II-VI’s acquisition of Coherent, Inc. was one of the boldest consolidation moves photonics has ever seen. Under Chuck Mattera, II-VI didn’t just grow—it rolled up capabilities across the stack, most notably with Finisar in 2019 and then the legacy Coherent in 2022. And after winning that fight, it did something even rarer: it took the acquired company’s name. II-VI became Coherent.

Mattera later wrote that II-VI began as “a startup underwritten by a US$125,000 initial investment.” By fiscal 2023, the successor company was producing US$5.2 billion in revenue and sitting among the world’s largest photonics players. That’s an astonishing arc. But “big” isn’t the same as “successful,” at least not in the way public markets grade companies.

So was it worth it?

The honest answer is: the verdict is still being written.

On the one hand, Mattera assembled a platform that’s genuinely formidable—arguably the most complete photonics toolbox in the industry, spanning networking optics, industrial and precision lasers, and the materials underneath both. On the other hand, he bought that toolbox with real costs: heavy leverage, integration complexity, and years where the stock didn’t get paid for the ambition because simpler, cleaner stories were easier to own.

That’s why the Jim Anderson era matters so much. The technology base is already there. The question now is operational: can Coherent run like one disciplined company? If Anderson can lift margins, simplify the footprint, and focus the portfolio—while accelerating the parts of the business riding AI networking demand—then the Coherent acquisition won’t just be remembered as expensive. It’ll be remembered as decisive.

For long-term investors, this is the quintessential pick-and-shovel play of the AI era. Coherent doesn’t mine the gold. It doesn’t build the LLMs or design the GPUs. But when NVIDIA ships an H100 cluster, when Microsoft builds another data center, when factories automate and EV power electronics scale, Coherent’s lasers, optics, and materials are part of what makes those systems actually work.

And in a tech world obsessed with the newest model and the latest benchmark, there’s something almost contrarian about that: a company that spent fifty years getting good at growing crystals—and then used that quiet advantage to buy its way to the center of the photonics universe.

XI. Carve-Outs

If you want to go one level deeper on the science, the history, and the industry context behind Coherent, here are a few great places to start.

Books: - The Alchemy of Air by Thomas Hager — Not about photonics, but a perfect window into how a single materials breakthrough can reshape an entire economy. - The Idea Factory by Jon Gertner — The story of Bell Labs, and the research culture that helped lay the groundwork for many of the laser and semiconductor technologies this company ultimately rides.

Industry Resources: - Lightwave and Optics.org — Two solid, ongoing sources for optical communications news, product cycles, and competitive dynamics. - Yole Développement — Widely used market research on photonics, compound semiconductors, and the supply chains behind them.

Technical Foundations: - Fiber Optics Weekly Update — A practical way to build intuition for how fiber networks and optical components actually work without drowning in jargon. - OFC (Optical Fiber Communication Conference) proceedings — The industry’s front line. If you want to see what’s coming before it shows up in earnings calls, this is where it tends to surface first.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music