AMD: The Resurrection of Silicon Valley's Ultimate Underdog

I. Introduction: From the Brink of Oblivion to the AI Arms Race

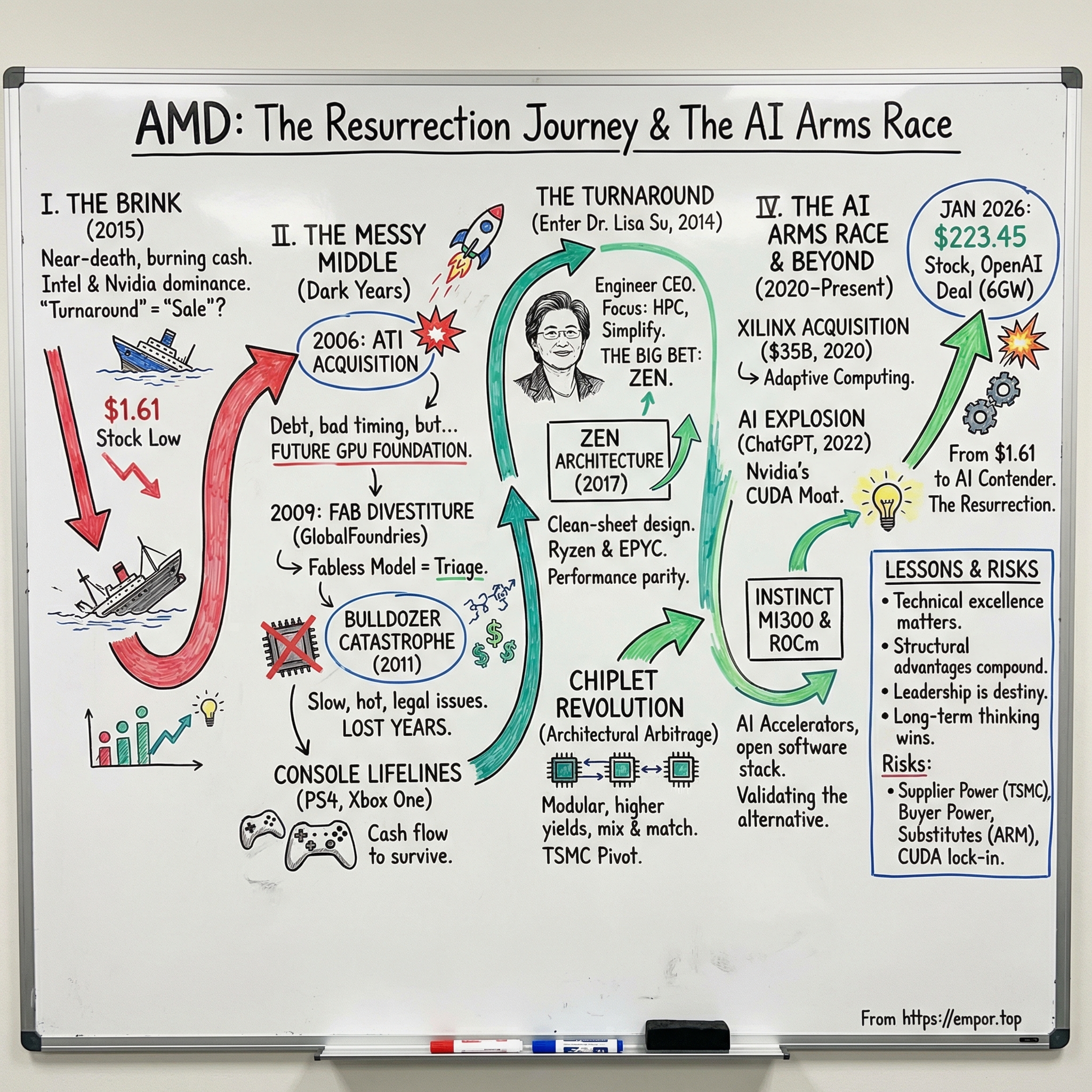

In July 2015, AMD’s stock sank to $1.61 a share. The company was effectively out of oxygen—burning cash, losing market share quarter after quarter, and staring down a future where “turnaround” was starting to sound like a euphemism for “sale” or “shutdown.” Inside the Sunnyvale headquarters, employees reportedly sold off office furniture to keep the lights on. Intel’s grip on CPUs looked unbreakable. Nvidia owned graphics. In the semiconductor world, AMD felt like yesterday’s news.

Now jump to January 14, 2026. AMD closed at $223.45, after hitting an all-time high of $264.33 on October 29, 2025. From the 2015 low, that’s a return that’s hard to say out loud without sounding like you’re exaggerating. And 2025 didn’t just ride the market up—AMD rose 77.3% that year, outpacing the S&P 500 by a wide margin. Along the way, OpenAI signed a multi-year deal to buy 6 gigawatts of AMD Instinct AI accelerators—framed as a $120 billion revenue opportunity over the next five years.

But this isn’t just a stock chart miracle. It’s a company that went from nearly dead to doing something nobody was supposed to be able to do: fight a two-front war against Intel in CPUs and Nvidia in GPUs—and not only survive, but win meaningful ground.

This story is about resilience through technical leverage. It’s about knowing when to ignore consensus, place a long-dated bet, and absorb years of pain while you build the thing that can change the game. And it’s about the leader who saw that path clearly: Lisa Su, a Taiwanese-American electrical engineer who walked into a company in free fall and treated it less like a turnaround and more like an engineering problem.

The arc of AMD’s journey stretches across decades and reads like a survival saga: Jerry Sanders and the era of marketing swagger and “Real Men Have Fabs”; a disastrous ATI acquisition that nearly crushed the company but, years later, turned out to be strategic oxygen; the gut-wrenching decision to spin off manufacturing and go fabless; the Bulldozer catastrophe and the band-aid years of simply staying alive; the agonizing wait for Zen; the chiplet revolution that changed the economics of modern CPUs; and, now, an all-out assault on Nvidia’s AI stronghold.

Each chapter is a case study in how competition actually works in capital-intensive industries—where cycles are long, mistakes are expensive, and the only real advantage is being right about the future before everyone else is forced to admit it.

Let’s dive in.

II. Origins: "Real Men Have Fabs" (1969–2000)

Picture a modest living room in Sunnyvale, California, in May 1969. Eight engineers from Fairchild Semiconductor are huddled together, plotting their escape. They’re not the headliners. Intel had already been founded a year earlier by the A-list: Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore.

These eight know they’re not going to beat Noyce and Moore by playing the same game, the same way. So they make a very un-Silicon-Valley choice: they put a salesman in charge. Not just any salesman—Jerry Sanders, a flamboyant, force-of-nature personality who understood something the engineers didn’t always want to admit: in semiconductors, the story you sell can matter almost as much as the silicon you ship.

Walter Jeremiah Sanders III would go on to lead Advanced Micro Devices for decades, serving as CEO from 1969 to 2002. His worldview was forged long before AMD existed. He grew up on the South Side of Chicago, raised by his paternal grandparents. At eighteen, he was attacked by a street gang and beaten so badly a priest was called in to administer last rites. He survived, and later said the experience taught him two lessons: “Don’t count on other people—not my favorite part of learning. And the second thing I learned was loyalty, because a neighbor threw me in the trunk of his car and got me to a hospital, so I survived.”

That loyalty—hard-earned and personal—would become part of AMD’s cultural DNA.

At Fairchild, Sanders rose quickly through sales into marketing leadership. But in 1968, new management led by C. Lester Hogan clashed with Sanders’ boisterous style. His personality made the new regime uneasy, and they fired him.

So when the eight engineers came to him to run their new company, Sanders agreed—but only on one condition: he wanted to be president. The group argued, then relented. Innovation Magazine dubbed the venture “the least likely to succeed of the technology startups of the 68–69 timeframe.” Sanders took it as a dare.

On May 1, 1969, Jerry Sanders and seven others from Fairchild founded Advanced Micro Devices. AMD began as a producer of logic chips—nothing glamorous, but exactly the kind of business where a relentless operator could carve out a foothold.

The Second-Source Strategy: AMD's Cornered Resource

Then, in 1982, something happened that would shape AMD’s destiny for the next four decades.

In February 1982, AMD signed a contract with Intel to become a licensed second-source manufacturer of the 8086 and 8088 processors. This wasn’t Intel doing AMD a favor. It was IBM forcing the issue.

IBM wanted to use Intel’s 8088 in its IBM PC, but IBM policy required at least two suppliers for critical components. No second source, no deal. So Intel—pragmatic and confident—agreed to let AMD make compatible parts.

The companies formalized this in a technology exchange agreement that the Ninth Circuit later described as “in effect, a reciprocal second sourcing agreement: if one party wanted to market parts the other party had developed, it could offer parts that it had developed in exchange.”

This became AMD’s cornered resource: a moat you can’t code around, hire around, or outspend. As x86 became the default language of computing, only a tiny number of companies could legally make processors compatible with it—and AMD had the key. It meant that even when AMD faltered, the world had a reason to want it alive: an Intel monopoly would have been untenable.

Sanders didn’t just sign the deal and smile for the cameras. He pushed for a renegotiated licensing arrangement that enabled AMD to copy Intel’s processor microcode to build its own x86 processors. But the relationship was never going to stay friendly. Sanders used the agreement’s open-ended language to drive efforts to reverse-engineer and clone Intel’s 8086. Intel countersued. AMD’s stock collapsed. For a moment, it looked like the x86 bet might kill the company.

The legal war dragged on for years. AMD ultimately won in arbitration in 1992, but Intel challenged the outcome. The fight continued until 1994, when the Supreme Court of California sided with the arbitrator—and with AMD.

AMD had survived, and it had something priceless: a path to remain Intel’s only real x86 rival.

The K7/Athlon Era: First Blood

Through the 1990s, AMD lived in Intel’s shadow—usually cheaper, usually behind, and always treated like the scrappy alternative.

Then AMD launched the K7 architecture, code-named Athlon, and for a brief, glorious stretch, the script flipped.

Athlon debuted on June 23, 1999, and by August it was broadly available. From then until January 2002, that first K7 generation was the fastest x86 chip in the world. The shift was so jarring that even the industry commentary sounded surprised: AMD, historically trailing Intel’s fastest processors, had overtaken the leader. Major OEMs like Compaq and IBM were planning to use Athlon in their most powerful PCs, and analysts were blunt—Athlon was meaningfully faster than Intel’s Pentium III.

For the first time, AMD wasn’t just “good for the money.” It was genuinely better.

And AMD didn’t just edge Intel. It embarrassed them. As Intel prepared to launch a 1GHz Coppermine Pentium III in March 2000, AMD stole the moment with the Athlon 1000—and did it two days earlier, becoming the first to ship a 1000MHz x86 CPU.

One gigahertz was a psychological milestone. In an era when clock speed was the headline, “1,000MHz” sounded almost absurd—big, round, and undeniable. AMD got there first, and everyone noticed.

For investors and competitors alike, the Athlon era proved something fundamental: AMD’s engineers could go toe-to-toe with anyone when the stars aligned. But it also hinted at the darker truth of this industry—one bad strategic swing can erase years of good execution.

Which brings us to 2006.

III. The Icarus Moment: The ATI Acquisition (2006–2008)

On July 24, 2006, AMD CEO Hector Ruiz stepped up to the microphone and made a move that would define the company for the next twenty years: AMD would buy ATI, the graphics chipmaker, in a deal valued at about $5.6 billion. The transaction closed on October 25, 2006, paid with a mix of cash, debt, and roughly 56 million shares of AMD stock.

The idea had a name that sounded like destiny: “Fusion.” Put the CPU and the GPU on the same silicon. Build an integrated platform Intel couldn’t easily copy. In plain terms, AMD wanted to stop selling chips in isolation and start selling a complete computing engine—general-purpose processing plus graphics, together, designed as one.

And on paper, it wasn’t crazy. ATI gave AMD real graphics IP and a world-class GPU team, and it set the foundation for what would become AMD’s Fusion line of processors—chips that integrated CPU compute with GPU graphics in a single package.

The problem wasn’t the vision. It was the bill.

The economics were brutal. The roughly $5.4 billion price tag reflected AMD’s own stock trading around $20 a share at the time. And the cash portion didn’t come from a pile of excess profits; it came from financing. AMD lined up a $2.5 billion term loan through Morgan Stanley Senior Funding and paired it with about $1.8 billion of cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities to fund the deal.

Then the world turned.

AMD had essentially bought at the top of a credit cycle and loaded itself with debt—right before the Great Recession slammed the door on easy money. At the exact same moment, Intel launched the Core architecture, a performance counterpunch that flipped the CPU narrative back in Intel’s favor. AMD’s CPU roadmap slipped. The ATI integration was harder than expected. And with debt payments now a constant drumbeat, AMD didn’t have the luxury of time.

Ruiz’s tenure is complicated. He led AMD during one of its strongest competitive stretches, roughly 2003 to 2006, when AMD chips were widely viewed as superior to Intel’s. He also authorized a major antitrust lawsuit against Intel. But the end was ugly: seven straight quarters of losses totaling billions, culminating in Ruiz’s resignation in July 2008, right as the financial crisis deepened. Later, he was pulled into an insider trading scandal, accused of sharing confidential AMD information with hedge fund traders.

From the outside, the conclusion seemed obvious. The ATI deal looked like the swing that finally broke AMD: too expensive, too much debt, too little time, and a competitor that had just regained technical leadership. Market share dropped. The roadmap fell behind. Survival became the only objective.

And yet—this is the twist that makes AMD’s story so hard to stop listening to—ATI turned out to be more than a bad purchase at a bad time.

Because what AMD bought in 2006 wasn’t just a product line. It was the GPU foundation: the engineers, the architectures, the Radeon brand, the muscle memory of building massively parallel compute. Years later, when machine learning became the defining workload in computing, that “graphics” expertise would suddenly look like the most important asset in the building.

But before any of that could matter, AMD had to do something far less glamorous.

It had to stay alive.

IV. The Wilderness & The Fab Divestiture (2009–2014)

By late 2008, AMD was out of room to improvise. It was bleeding cash, carrying debt from ATI, and stuck in the most punishing arms race in the industry: manufacturing.

Jerry Sanders had turned “Real men have fabs” into a kind of creed. For decades, AMD did exactly that—designed its chips and built them, too. But the industry had changed. Leading-edge fabs were no longer “a factory.” They were multibillion-dollar science projects that demanded constant reinvestment. Unless you had enormous scale, the economics could crush you.

Hector Ruiz and then-CEO Dirk Meyer faced the uncomfortable truth Sanders never wanted to hear: real men go bankrupt with fabs.

So AMD made the most consequential structural move in its modern history. On October 7, 2008, it announced plans to spin off its manufacturing operations into a separate company, first described as “The Foundry Company.” Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala, through its subsidiary Advanced Technology Investment Company, agreed to invest $700 million to raise its stake in AMD’s manufacturing business to 55.6%, and also invested $314 million for 58 million new AMD shares—bringing its AMD ownership to 19.3%.

On March 4, 2009, the new entity had a name: GlobalFoundries.

For AMD, this wasn’t a victory lap. It was triage. The deal delivered $700 million in cash, about $1.1 billion in debt relief, and left AMD with a 34% stake in the spun-out foundry business. AMD would go forward as a fabless company—designing chips, outsourcing the manufacturing, and trying to survive long enough for the next product cycle to turn.

The problem was: the next product cycle was a disaster.

The Bulldozer Catastrophe

In October 2011, AMD launched Bulldozer, a brand-new CPU architecture built around a simple bet: the future would be massively multi-threaded, so more cores would win.

But the present didn’t cooperate.

Bulldozer’s flagship chips, like the FX-8150, struggled in workloads that weren’t heavily threaded. Reviewers found it falling behind Intel’s second-generation Core processors, and in some cases getting matched—or even beaten—by AMD’s own older Phenom II X6. That is a brutal sentence for any “next-gen” architecture.

Bulldozer became known for exactly the wrong reasons: slow, hot, and power hungry. Windows also couldn’t reliably schedule work across Bulldozer’s unusual module design, which only made real-world performance feel worse.

Years later, the fallout even turned legal. In November 2015, AMD was sued under the California Consumers Legal Remedies Act for allegedly misrepresenting Bulldozer’s core count—arguing that each module wasn’t truly equivalent to two independent CPU cores. In August 2019, AMD agreed to settle for $12.1 million.

But the real damage had already been done. Bulldozer didn’t just miss expectations. It burned time—years of it—in the one market where you don’t get years back.

The Band-Aid Years and Console Lifelines

Rory Read, a former IBM and Lenovo executive, became CEO in August 2011. His mandate wasn’t to beat Intel. It was to stop AMD from bleeding out.

Read leaned hard into something that could actually pay the bills: semi-custom chips. Instead of trying to win every benchmark, AMD would design specialized processors for big customers—products that were less glamorous than flagship PC CPUs, but far more dependable as a business.

That’s where the console deals came in—and they were a lifeline.

Sony launched the PlayStation 4 in early 2013, and AMD built the custom processor inside it. Microsoft’s Xbox One used an AMD processor too. Internally, AMD leaders later described the effort as helping the company avoid bankruptcy. The console chips weren’t high-margin, but they were steady. Predictable. Bankable.

Across the full console generation, the scale was enormous—an estimated 117 million PlayStation 4 units and roughly 58 million Xbox One units. AMD didn’t capture all that value, but it captured something it desperately needed: enough stable cash flow to keep investing in the future.

More than anything, the console business bought time.

Time for a new CEO to arrive. Time for a radical new CPU architecture to be designed. Time for AMD to set up the most important bet it would make in decades.

V. The Turnaround: Enter Dr. Lisa Su (2014–2017)

On October 8, 2014, AMD’s board made a decision that would end up defining the next decade of the company’s life: Lisa Su became president and CEO, replacing Rory Read.

Su didn’t show up with a flashy slogan or a grand rebrand. She laid out a plan that sounded almost boring in its simplicity: make the right technology investments, streamline the product lineup, keep diversifying revenue, and—her word—simplify. The subtext was clear. AMD didn’t need more hustle. It needed focus, and it needed execution.

Wall Street didn’t throw a party. The stock sat around $3. Commentary at the time had a consistent edge of skepticism: she’s an engineer, not a salesman—can she really talk customers and investors into believing again?

The thing was, AMD didn’t need a pitchman. It needed someone who could look at a roadmap, a process node, a power budget, and a microarchitecture—and tell, with brutal honesty, what was real and what was wishful thinking.

Su was built for that.

Born in Taiwan and raised in the United States, she earned three degrees at MIT, then built a career at Texas Instruments, IBM, and Freescale. At IBM, she was known for hands-on work in semiconductor R&D, including silicon-on-insulator and more efficient chip designs. She arrived at AMD with what the company had been missing for years: deep technical credibility paired with the authority to make hard calls.

And the hard calls came immediately. When she took over, AMD was still fighting for breath, and the share price reflected it.

The Big Bet: Zen

Su’s first major move wasn’t launching a new chip. It was cutting. She pushed AMD out of marginal businesses—areas like low-end mobile and tablets—where the company was battling for scraps and burning precious engineering time. Internally, the thinking became known as “the 5% rule”: if it wasn’t high-margin and high-performance, it didn’t deserve focus. AMD would concentrate on High-Performance Computing, where winning actually mattered and where the economics could work.

Then she made the bet that would either resurrect AMD or finish it.

No more incremental fixes to Bulldozer. No more patching a philosophy that wasn’t delivering. Su greenlit a clean-sheet CPU architecture—an all-new core design from the ground up.

That project was Zen.

AMD began planning Zen not long after re-hiring Jim Keller in August 2012, and the company formally revealed Zen in 2015. Keller led the effort during his three-year stint, alongside Zen team leader Suzanne Plummer, with AMD Senior Fellow Michael Clark as chief architect.

Keller wasn’t just another hire. He was the kind of engineer whose name carries lore inside this industry: lead architect of AMD’s K8, involved in Athlon (K7), instrumental in Apple’s A4/A5, and a coauthor of x86-64 and HyperTransport. If AMD was going to try to out-innovate Intel again, it needed that level of design talent—someone who’d already done it once.

By the time Ryzen launched in 2017, Keller had already moved on—this time to Tesla. But the blueprint he helped set in motion was the one AMD would stake its future on.

Zen, as AMD described it, was a clean-sheet break from Bulldozer. Built on a 14 nm FinFET process, designed to be more energy efficient, and engineered for a big jump in instructions per cycle. It also introduced SMT, letting each core run two threads.

In other words: Zen wasn’t supposed to be a little better. It had to be meaningfully better.

The Agonizing Wait

There was just one problem. You can’t ship a promise.

From 2014 through early 2017, AMD had to live in the gap between strategy and product. The company kept selling Bulldozer-derived chips into a market that knew they weren’t competitive, while asking customers and investors to wait for a future architecture that hadn’t proven itself in public yet.

Quarter after quarter, the questions didn’t change: When does Zen arrive? Is it real? Will it actually close the performance gap?

Su’s answer was consistency. No wild overpromising. No fake bravado. She managed expectations, protected credibility, and kept the company pointed at the same target.

Her view of the business was long-cycle and unsentimental. “When you invest in a new area, it is a five- to 10-year arc to really build out all of the various pieces,” Su said. “The thing about our business is, everything takes time.”

In December 2016, AMD finally showed Zen engineering samples. The early benchmarks looked encouraging—enough to suggest this wasn’t vaporware.

But the real test was still ahead.

March 2017 was coming.

VI. David Slays Goliath: Ryzen, EPYC, and Chiplets (2017–2020)

Zen finally arrived on shelves in early March 2017, first inside Ryzen desktop CPUs. By mid-2017, the same core architecture was powering EPYC in servers, and by the end of the year it showed up in APUs, bringing Zen into more mainstream PCs.

The immediate takeaway was simple and shocking if you’d lived through the Bulldozer years: Ryzen wasn’t a “good try.” It was genuinely good. After years of selling the cheaper alternative, AMD could finally stand in the same sentence as Intel on performance, not just price. The market responded. Between 2017 and 2020, AMD’s CPU share climbed from under 10% to over 20%, a real reversal in a market that normally moves like tectonic plates.

But Ryzen, as important as it was, was only half the story. The real prize was the data center—where margins are thick, customers are sticky, and wins tend to compound for years.

In March 2017, AMD announced it was re-entering servers with a Zen-based platform code-named Naples. In May, it revealed the EPYC brand. And in June, it launched the first EPYC 7001 processors, with configurations reaching up to 32 cores per socket—enough to make EPYC a credible alternative to Intel’s Xeon Scalable lineup and, more importantly, enough to get serious customers to actually take meetings again.

The Chiplet Revolution

Then AMD did something even more consequential than building a great core. It changed the way modern CPUs could be built.

Instead of betting everything on one huge, monolithic piece of silicon, AMD leaned into a modular approach: chiplets. With Zen 2, AMD’s desktop, workstation, and server CPUs became multi-chip modules—built from the same core chiplets, then paired with different I/O silicon in a hub-and-spoke layout.

The intuition is wonderfully unglamorous: smaller pieces are easier to manufacture well. When a defect hits a giant monolithic die, you throw away the whole thing. When a defect hits a small chiplet, you toss just that chiplet. Yields go up. Costs come down. And because you can combine chiplets like building blocks, you can scale product lines without redesigning everything from scratch.

In practice, this made AMD’s lineup feel almost elastic. Ryzen could scale up across core counts, while EPYC could stretch much further for servers. And AMD could also mix process nodes—using leading-edge silicon where it mattered most, and more mature nodes where it didn’t—optimizing both performance and economics.

In November 2018, AMD previewed the next wave at its Next Horizon event: second-generation EPYC, code-named Rome, based on Zen 2. Rome’s design showcased the chiplet idea in its purest form: multiple 7nm compute chiplets around a central I/O die, tied together with Infinity Fabric. AMD launched EPYC Rome on August 7, 2019, and it made the chiplet philosophy impossible to ignore.

Intel, meanwhile, was getting stuck in the mud. For decades, Intel’s superpower had been vertical integration: design the chips, manufacture the chips, control the entire stack. But when its process roadmap stumbled, that same integration turned from advantage to anchor. Intel’s 10nm delays kept stacking up. AMD, now a fabless designer, could simply ride the best manufacturing available.

The TSMC Pivot

This is where AMD’s earlier “triage” decision—spinning out the fabs—turned into a strategic weapon.

Zen 2’s chiplet approach depended on advanced manufacturing, and when GlobalFoundries exited the 7nm race, AMD pivoted hard to TSMC. TSMC’s process leadership let AMD deliver smaller, more efficient silicon and move quickly. For the first time, AMD had what it almost never had in the x86 era: a better design on a better process than Intel.

That combination hit Intel where it hurt most: the data center.

Hyperscalers like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google began deploying EPYC, drawn by the straightforward business case—strong performance, great performance-per-watt, and compelling total cost of ownership. And the share gains weren’t theoretical. By 2024, Lisa Su said AMD’s server CPU market share had reached 34%, with AMD’s server revenue share in Q2 2024 at 33.8% and unit share at 27.3%.

Investors took notice, too. Over Su’s tenure, AMD’s market cap grew from roughly $3 billion to more than $200 billion, and AMD overtook Intel in market capitalization for the first time.

The resurrection was real. But it didn’t mean the war was over.

It just meant AMD had finally earned the right to fight the next one.

VII. The New War: Xilinx & The AI Pivot (2020–Present)

In October 2020, with Zen working and momentum finally on AMD’s side, Lisa Su announced the biggest acquisition in the company’s history: Xilinx.

The two companies entered a definitive agreement for AMD to acquire Xilinx in an all-stock transaction valued at $35 billion. The pitch was straightforward: together, they would form a broader high-performance computing powerhouse, with a portfolio that spanned CPUs, GPUs, and Xilinx’s specialty—adaptive chips like FPGAs and adaptive SoCs. AMD said the deal would be immediately accretive to margins, EPS, and free cash flow.

And crucially, this time the structure matched the strategy.

Unlike ATI—which AMD bought from a position of weakness and financed with debt—the Xilinx deal was done from strength. All-stock meant AMD didn’t load the company up with new borrowings. A strong valuation meant a favorable exchange. And the fit was cleaner: Xilinx’s field-programmable gate arrays complemented AMD’s CPUs and GPUs in the data center, especially for specialized workloads where flexibility mattered as much as raw throughput.

When the acquisition closed, AMD framed it as the creation of a “high-performance and adaptive computing leader,” with significantly expanded scale and one of the strongest lineups in computing, graphics, and adaptive products. The combined company also positioned AMD as the No. 1 FPGA vendor, ahead of Intel in the No. 2 spot—exactly the kind of quiet, strategic advantage that matters in enterprise.

And then the market changed again.

The AI Explosion

In November 2022, ChatGPT detonated in public, and the entire competitive landscape tilted toward one thing: AI compute.

Overnight, Nvidia’s data center GPUs—descended from gaming hardware—became the most valuable shovels in the modern gold rush. But Nvidia’s real lock wasn’t just silicon. It was CUDA: a decade-plus head start in tooling, libraries, and developer habits. Hyperscalers didn’t just want Nvidia chips; they wanted the whole ecosystem that made them easy to deploy and hard to replace.

AMD had the ATI-derived GPU heritage. What it didn’t yet have was Nvidia’s software gravity.

Nvidia’s position in AI accelerated because CUDA became the default standard: deeply integrated into the major AI tools, tuned for performance, and reinforced by developer lock-in. AMD and others could build credible hardware, but dislodging an ecosystem is a different kind of fight.

The MI300 Launch and the ROCm Challenge

AMD’s counterpunch was the Instinct MI300 series—a direct attempt to do to Nvidia what Ryzen and EPYC did to Intel: show up with a real alternative, price it competitively, and iterate relentlessly.

The headline product was the Instinct MI300X, a GPU-focused accelerator with 192GB of HBM3 memory and 5.3 TB/s of memory bandwidth. The point wasn’t just specs. It was practicality: large language models are ravenous for memory, and MI300X’s capacity made it attractive for the kind of “how do we fit this model” problems that dominate real deployments. AMD also claimed MI300X could deliver 1.6 times inference performance on specific LLMs versus Nvidia’s H100.

The broader strategy was familiar: be “good enough” first, then get better fast. MI300’s performance and pricing gave customers leverage and optionality, even if AMD still trailed Nvidia overall. For cloud buyers, competition wasn’t philosophical—it was a way to get supply, control costs, and avoid a single-vendor choke point.

But in AI, hardware is only half the product. The software stack is the gate.

That’s where ROCm comes in: AMD’s open-source answer to CUDA, a software stack with drivers, tools, and APIs for GPU programming—from low-level kernels to end-user applications—aimed at generative AI and high-performance computing, with a focus on making migration easier.

AMD positioned ROCm’s HIP (Heterogeneous-compute Interface for Portability) as a key wedge: it allows developers to port CUDA applications to AMD GPUs with minimal code changes. And with ROCm 7, introduced in 2025, AMD said it delivered major gains versus ROCm 6—about a 3.5x uplift in inference performance on MI300X, and a 3x boost in effective floating point performance for training. AMD also claimed these software improvements, combined with its newer MI355X GPU, produced a 1.3x edge in inference workloads over Nvidia’s B200 when running DeepSeek R1.

Initial reactions from major customers were encouraging: Microsoft and Meta both adopted MI300X for inferencing infrastructure. That matters, because in this market, credibility is earned through deployment, not demos.

The OpenAI Deal: Validation

The most visible validation arrived in late 2025.

AMD stock rose 77.3% in 2025, nearly doubling the S&P 500’s return, as the company announced major AI wins—most notably a multi-year deal with OpenAI to buy 6 gigawatts of AMD Instinct AI accelerators, framed as a $120 billion revenue opportunity over the next five years. AMD also secured deals with Oracle, with Oracle planning to install 50,000 AMD GPUs across its cloud infrastructure.

Six gigawatts is an attention-grabbing number because it describes commitment at the data center scale—real power budgets, real racks, real procurement. Some estimates translate that into millions of accelerators based on roughly 1,000 watts per card, and with pricing discussed around $20,000 per card for the current generation, the implied revenue opportunity becomes enormous.

The AI war, though, is nowhere near settled. Nvidia still holds massive advantages in ecosystem, installed base, and developer mindshare. But AMD proved something that would have sounded implausible not long ago: it can win at the top end of AI, not just participate at the margins.

And once customers believe you can ship and support the real thing, the next battles stop being hypothetical. They become procurement decisions.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The Second-Source Moat

AMD’s x86 license may be the most valuable—and most misunderstood—piece of intellectual property in modern computing. Tucked inside it is a poison pill: the agreement terminates if either party undergoes a change of control. In plain English, you can’t just buy AMD and keep the crown jewels.

That one clause explains decades of “AMD will get acquired” speculation that never turned into reality. Any buyer would be purchasing the company only to instantly lose the license that makes the company worth buying. The result is a strange but powerful equilibrium: AMD needs to remain independent to keep its x86 rights, and the world needs AMD to remain independent to keep Intel from becoming a monopoly.

Counter-Positioning: The Fabless Model

Spinning out the fabs didn’t just reduce complexity. It rewired AMD’s economics.

While GlobalFoundries was still inside the company, manufacturing problems translated directly into product problems: delays, weaker chips, and fewer chances to fight Intel on equal footing. The spin-out changed that. AMD gained breathing room in cash flow, removed restrictions on where it could manufacture, and—most importantly—freed itself to chase the best process technology available instead of being stuck with whatever its own fabs could deliver.

Going fabless turned fixed costs into variable costs. When demand fell, AMD didn’t have to carry the dead weight of underutilized factories. When demand rose, AMD could ride TSMC’s leading-edge manufacturing rather than spending years and billions trying to catch up with new facilities of its own.

Architectural Arbitrage: Chiplets

Chiplets were AMD’s Henry Ford moment—an assembly line for silicon.

Instead of putting the whole business on the yield of one giant, monolithic die, AMD broke the problem into smaller, more manufacturable blocks. That lowered risk, improved yields, and let AMD scale across product tiers by mixing and matching the same building blocks. The punchline is business, not just engineering: chiplets gave AMD room to price aggressively without turning margins into collateral damage.

Leadership Dynamics: The Engineer CEO

Lisa Su’s turnaround is now widely viewed as one of the greatest corporate transformations in tech. But it wasn’t magic, and it wasn’t marketing. It was focus.

Her strategy had a clear through line: stop burning time on low-margin, generic products and double down on high-performance computing—where AMD could actually win on technical merit and get paid for it. Zen wasn’t just a product launch; it was the centerpiece of that decision.

What made Su unusually effective was that she understood the physics of the product. She could look at roadmaps and trade-offs and make long-horizon bets—three to five years out—without flinching. And because she had technical credibility, she could make the hard calls that turnarounds require: killing projects, exiting markets, and betting the company on Zen when there was no backup plan.

IX. Analysis: Competitive Position & Risks

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Cornered Resource: AMD’s x86 license is still the company’s most stubborn advantage. You can’t just spin up a startup and decide to compete in PC and server CPUs; the legal and IP wall is too high. And even when alternatives exist, the real barrier is all the software history baked into x86—decades of code that companies don’t want to rewrite unless they absolutely have to.

Counter-Positioning: Against Intel, AMD’s chiplet strategy created a different cost structure, not just a different product. AMD can mix and match smaller building blocks and ride the best foundry process available. Intel, for years, was optimized for big monolithic dies built in Intel fabs—a model that’s hard to unwind quickly without sacrificing the very integration advantage that made Intel, Intel.

Switching Costs: In the data center, switching costs cut in AMD’s favor. x86 compatibility makes it easier for buyers to swap Intel out and put AMD in without rebuilding their software world. But in AI, AMD runs into the mirror image of that problem: CUDA. Nvidia’s platform lock-in makes it difficult for AMD to take training share, even when the hardware is competitive.

Porter's 5 Forces

Supplier Power: This is AMD’s biggest structural risk. As a fabless company, AMD lives and dies by other people’s factories—especially TSMC. Lisa Su told Nikkei Asia that AMD would consider “other manufacturing capabilities” beyond TSMC to build a more resilient supply chain, a clear signal that the dependency is not theoretical inside the company.

TSMC has leverage because there just aren’t many peers at the leading edge. If Taiwan faced disruption—natural disaster, geopolitical conflict, or simply capacity constraints—AMD’s options would be limited. Samsung and Intel Foundry Services have been working to close the gap, but they’ve trailed TSMC on the most advanced processes.

Buyer Power: AMD’s biggest customers are also some of the most powerful buyers on earth. Hyperscalers like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google negotiate hard, demand customization, and increasingly build their own chips—AWS Graviton and Google TPUs being the obvious examples. Even when they buy from AMD, they can credibly threaten to buy less.

Threat of Substitutes: The long-term threat to AMD isn’t another x86 company. It’s the idea that the world stops caring about x86. ARM has already proven it can win on efficiency and integration—Apple Silicon made that obvious in laptops. AWS Graviton made it credible in servers. If that migration accelerates, AMD’s “cornered resource” matters less, because the game itself shifts.

Bull Case

AMD takes meaningful share in AI accelerators, and even a slice of that market would be transformative. EPYC keeps compounding in servers as more of the data center shifts from Intel to AMD. ROCm matures into a credible ecosystem for real deployments, particularly in inference, where buyers are often more flexible than in training. AMD believes its multi-generational EPYC portfolio can put it in position to lead in servers, and it has said it expects to reach more than 50% server CPU revenue market share. In data center AI, AMD has set an ambition to drive revenue CAGR of more than 80%.

Bear Case

Nvidia’s software moat holds. Developers stay glued to CUDA, and AMD’s hardware gains don’t translate into lasting platform wins. ARM continues to eat into x86 across laptops and servers, shrinking the core market AMD fought so hard to reclaim. Intel executes a real turnaround, regains manufacturing leadership with Intel 18A, and wins back share in the data center. And looming over all of it: supply chain fragility. If U.S.-China tensions disrupt TSMC operations or trigger export restrictions, AMD’s growth could get clipped by forces entirely outside its control.

X. Key Metrics to Watch

If you’re trying to understand whether AMD’s comeback in CPUs can translate into a durable position in AI, there are three numbers that tell the story better than any hype cycle.

1. Data Center Revenue Growth Rate

AMD’s Data Center segment posted $3.7 billion in revenue, up 57% from a year earlier. That’s the clearest signal that EPYC is still expanding in servers and Instinct is starting to matter in AI—training and inference alike.

This is where AMD’s future is being written. If this line keeps compounding at a strong clip, it means the strategy is working. If it slows sharply, that’s usually competition showing up—Intel in CPUs, Nvidia in GPUs.

2. Server CPU Market Share (Revenue Basis)

On units, AMD’s share in server CPUs is still under 25%. On revenue, it’s closer to a third of the market. That gap is the point: buyers aren’t just using EPYC as a cheaper substitute. They’re paying up for it in the workloads that actually carry margins.

Unit share tells you adoption. Revenue share tells you positioning. AMD needs to keep proving it can win the premium tiers, not just the volume tiers.

3. ROCm Software Adoption

ROCm is the hinge between “AMD has competitive hardware” and “AMD is a real platform.” AMD’s ROCm open software stack has been gaining momentum, with meaningful performance and feature upgrades in each release. AMD also says ROCm downloads have grown 10x year-over-year.

In AI, software is the lock-in. ROCm adoption is the best early indicator of whether AMD can meaningfully loosen Nvidia’s CUDA grip—or whether the market will keep treating AMD as the alternative you trial, but don’t standardize on.

XI. Epilogue: The Transition from "The Cheaper Option" to "The Performance Leader"

Step back and look at the full arc of AMD’s life. This company started as a scrappy second-source supplier, spent years as Intel’s cheaper shadow, flirted with oblivion after a debt-loaded acquisition, and somehow emerged as a real force in the two most consequential arenas in computing: CPUs and AI accelerators. In an industry where one missed process node can erase a decade, that kind of resurrection is not supposed to happen.

And yet, by the fall of 2025, AMD’s results no longer read like a turnaround story. They read like a company that had found its footing.

AMD reported its third-quarter 2025 financial results: record revenue of $9.2 billion, gross margin of 52%, operating income of $1.3 billion, and net income of $1.2 billion. On a non-GAAP basis, gross margin was 54%, operating income was $2.2 billion, and net income was $2 billion.

Zooming out, AMD’s revenue for the quarter ending September 30, 2025 was $9.246B, up 35.59% year-over-year. Revenue for the twelve months ending September 30, 2025 was $32.027B, up 31.83% year-over-year. AMD’s annual revenue for 2024 was $25.785B.

It’s a long way from where this story started. From $5.5 billion in revenue in 2016 to over $32 billion. From a roughly $3 stock in 2014 to over $220 by early 2026. From “will they make it?” to “can they take meaningful share from Nvidia in AI?”

If you want to take something durable from the AMD saga, it’s this:

Technical excellence eventually asserts itself. AMD spent years trying to survive on value positioning. That works only until the gap becomes too wide. The reversal didn’t come from better messaging. It came when Zen made AMD’s products genuinely competitive again—and then, in many cases, meaningfully better. In this business, you can’t talk your way out of physics.

Structural advantages compound. The x86 license—born out of IBM’s second-source requirements—kept AMD in the game when it had no right to still be there. Then additional leverage stacked on top: console wins that bought time, chiplets that rewired economics, and the shift to TSMC that let AMD ride a leading process while Intel fought its own manufacturing battles. None of these moves alone is the whole comeback. Together, they create compounding momentum.

Leadership is destiny. Jerry Sanders’ salesmanship willed AMD into existence. Hector Ruiz’s ATI bet nearly crushed it under debt at the worst possible moment. Lisa Su’s engineering discipline and strategic focus rebuilt it. Same industry. Same core constraints. Very different outcomes—depending on who was making the calls.

Long-term thinking wins—if you can survive long enough to cash the check. Su’s early tenure required a painful kind of patience: cutting distractions, narrowing focus, and living through the gap between “we have a plan” and “the market can buy it.” Betting on Zen meant selling uncompetitive products for years while building the thing that could change the company’s trajectory. Most public companies don’t have the stomach for that. AMD did.

When Su became CEO, she laid out a three-part plan to compete with Intel and Nvidia: ship only high-quality products, deepen customer trust, and simplify operations. The plan took time to pay off, but by 2022 AMD had surpassed Intel in both market value and annual revenue.

So what happens next?

The next decade will be written by the AI arms race. Nvidia still holds commanding advantages in training workloads and in the software ecosystem that makes its hardware the default choice. AMD’s challenge is clear: keep improving Instinct, but—more importantly—keep closing the software gap so customers can deploy at scale without feeling like they’re taking a career risk.

But if AMD has taught the market anything, it’s that “impossible” is often just “early.” This is the company that survived the Great Recession with debt on its back, lived through Bulldozer, spun out its fabs, and then came roaring back with Zen and chiplets. It has competed against giants before—and it has proven it can learn faster than it bleeds.

Lisa Su’s legacy is already secure: one of the defining turnarounds in modern technology, powered less by theatrics than by clarity, discipline, and execution. And AMD’s broader lesson is even simpler: in technology, comebacks are always available—if you can build real performance, make hard strategic choices, and wait long enough for those choices to compound.

Recommended Reading

If you want to go deeper on the forces that shaped AMD—and the industry it fought its way back into—these are the two books I’d start with:

- Chip War by Chris Miller — The clearest, most compelling overview of how semiconductors became both an economic engine and a geopolitical fault line.

- The Intel Trinity by Michael S. Malone — The best window into Intel’s culture and history, which is really another way of understanding the rival AMD has been chasing, dodging, and occasionally outmaneuvering for decades.

And if you want Lisa Su in her own words, skip the summaries and go straight to the primary sources: her keynote talks at AMD’s Advancing AI events, plus AMD’s earnings call transcripts, where the strategy shows up in the details.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music