Vertex Pharmaceuticals: The Relentless Pursuit of Transformative Medicine

I. Introduction

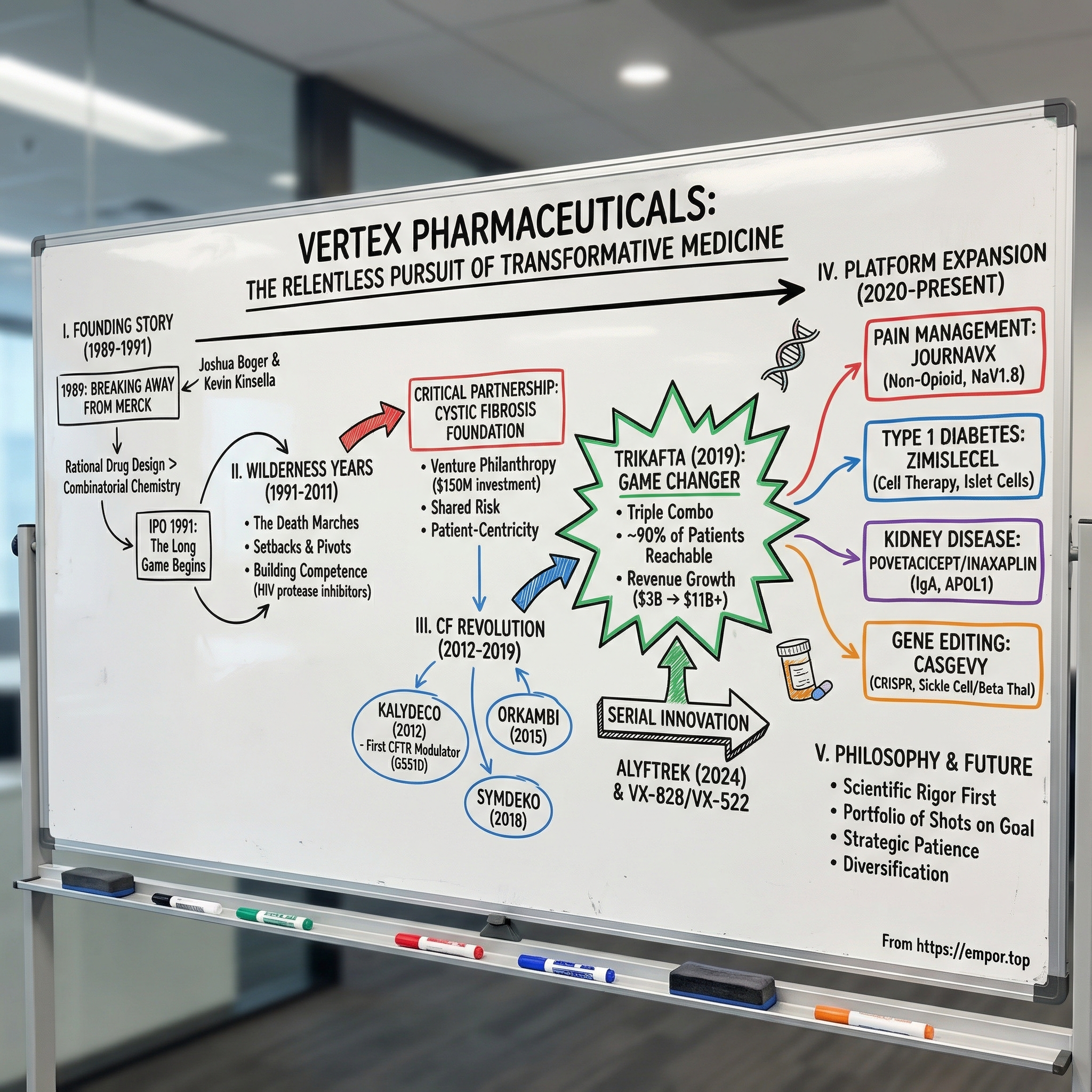

In the summer of 1989, a young chemist named Joshua Boger did something most people in his position wouldn’t even consider. He walked away from Merck, then widely seen as the gold standard of pharmaceutical science. Not because he was pushed out, not because he had a better offer, but because he believed Big Pharma’s golden era of breakthrough discovery was fading.

What he built instead became one of biotech’s most improbable arcs: Vertex Pharmaceuticals. For years, it was a company that seemed to do everything right scientifically and still couldn’t turn the corner commercially. It burned cash, reset its strategy, and endured the kind of long stretches that kill most startups. And then it did something almost no one does in drug development: it fundamentally changed the trajectory of a disease. Vertex transformed cystic fibrosis care, grew into a business generating more than eleven billion dollars a year, and is now pushing into pain management, gene editing, Type 1 diabetes, and kidney disease.

So how did a startup founded by a Merck scientist become the dominant force in cystic fibrosis, and then use that success to reach for entirely new frontiers? The answer is a story of scientific conviction and uncomfortable patience, of a partnership that rewrote what “nonprofit funding” could mean, and of a company willing to bet that if you truly understand a disease at its molecular root, you can build medicines that don’t just manage symptoms, but correct the biology underneath.

Along the way, Vertex’s journey runs straight through the big questions that define modern biotech: the brutal time lag between insight and impact, the power of venture philanthropy to finance high-risk science, the economics and controversy of rare-disease pricing, and the challenge of building a second act before your first franchise matures. Today, Vertex sits at an inflection point, with new products launched or nearing market, a pipeline that spans small molecules, cell therapies, and gene editing, and a market capitalization above one hundred billion dollars.

The through-lines of this story are clear: scientific innovation as a real competitive moat, patient-centricity as an operating system rather than a slogan, strategic patience measured in decades, and the discipline to diversify before the market forces you to.

II. The Founding Story: Breaking Away from Big Pharma (1989-1991)

Picture Merck’s research campus in Rahway, New Jersey, in the late 1980s. The company had been named Fortune’s Most Admired Corporation three years running. The labs were shipping blockbuster after blockbuster. The stock was flying. And inside that machine sat Joshua Boger, a Harvard-trained chemist who had climbed to Senior Director, overseeing both Biophysical Chemistry and Medicinal Chemistry.

He should’ve been satisfied. Instead, he was getting uneasy.

Boger’s issue wasn’t that Merck had stopped doing great science. It was that the industry’s philosophy of discovery was changing, and not in a direction he trusted. Drug hunting was drifting toward combinatorial chemistry: make huge libraries of molecules, run them through screens, and hope something interesting pops out. It worked sometimes. But to Boger, it felt like volume replacing understanding.

He believed in the opposite approach: rational drug design. If you could see your target clearly—its three-dimensional shape, down to the atomic level—you could design a molecule to bind it with intent. Not trying thousands of random keys, but machining the key you actually needed.

For Boger, this wasn’t a stylistic preference. It was a bet about outcomes. Start from structure and mechanism, and you could, in theory, build better medicines faster, with fewer side effects, because the work was guided by biology rather than luck. The problem was that Big Pharma wasn’t built for that kind of long, high-conviction, structure-first grind. Bureaucracy slowed decisions. Committees diluted accountability. Public-company pressure rewarded predictability over deep, uncertain research.

So in 1989, Boger left Merck and teamed up with Kevin J. Kinsella, a venture capitalist known for spotting scientific talent early. Together, they started Vertex Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Even the name carried a manifesto: vertex, the peak—the highest point. Boger wasn’t looking to build a service shop or a single-asset biotech. He wanted to build the pinnacle of drug design.

The first months quickly disabused everyone of the romance. A company whose pitch was essentially “we’re going to understand molecular structure better than anyone else” still had to raise money in the real world. Boger and Kinsella set off on what Vertex lore calls the “death marches”: punishing fundraising trips through Asia and Europe, selling a vision to investors who often couldn’t tell rational drug design from any other biotech promise.

Those years were captured in unusual detail by journalist Barry Werth, who embedded himself with the company and later wrote The Billion-Dollar Molecule in 1994. The title nods to the staggering cost of getting a single drug to market, and Werth’s story shows Vertex as it really was: cramped labs, big brains, constant cash pressure, and a group of people trying to will a new model of discovery into existence. It’s still one of the clearest portraits of what early biotech feels like from the inside.

Then came the leap. Vertex went public in 1991—two years after it was founded—with no products and no revenue. Just the claim that it could outthink disease at the molecular level. In time, the IPO would look brilliant: investors who bought and held would see gains exceeding 1,760 percent. But in 1991, that outcome was invisible. What lay ahead were decades of setbacks, pivots, and near misses—the kind of stretch that breaks most companies long before they ever find a breakthrough.

This founding story matters because it locked in Vertex’s operating belief: transformative medicines come from deep understanding, not brute force. That conviction would be tested again and again. But Vertex never really let it go.

III. The Wilderness Years: Building the Foundation (1991-2011)

For the two decades after its IPO, Vertex became the kind of company Wall Street loved to argue about and investors periodically gave up on. The promise was clear: rational drug design, done right, should beat trial-and-error chemistry. The problem was that in real life, translating beautiful structural biology into an approved medicine was slower, messier, and far more expensive than anyone wanted to admit in 1991.

In the 1990s, Vertex chased opportunities across viral infections, inflammatory diseases, and cancer. The science worked—at least in the way scientists mean it. The company scored early credibility with HIV protease inhibitors, proof that structure-based design could yield powerful drug candidates. But turning a candidate into a product meant surviving the long, punishing middle of biopharma: clinical trials that fail for reasons you can’t predict, regulatory demands that shift as you learn, and manufacturing realities that don’t care how elegant your molecule looks on a computer screen. All of it happened while the company steadily burned cash, with no meaningful revenue to soften the blows.

By 2004, Vertex’s pipeline had tightened around viral infections, inflammatory disorders, and cancer. Over time, the company went through management shake-ups and strategic resets. From the outside, that can look like instability. From the inside, it’s often the only rational response to biotech physics: most programs don’t work, and the only unforgivable sin is sticking with a failing program out of pride.

What ultimately kept Vertex alive wasn’t a single hero product. It was the accumulation of hard-earned competence. Year after year, the company got better at the unsexy essentials—how to design molecules that can survive in the body, how to run trials, how to talk to regulators, how to build the early scaffolding of commercialization. None of that produced splashy headlines. But those muscles would matter enormously when Vertex finally found a disease it could truly change.

That disease entered the story through an unlikely partner: the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. The foundation had pioneered something that, at the time, sounded almost radical—venture philanthropy. Instead of funding academic research and hoping industry picked it up, it invested directly into drug development at biotech companies. It took risk like a venture fund and, in return, secured the possibility of royalties that could be recycled into more research.

The foundation ultimately invested about $150 million into Vertex’s cystic fibrosis program—an enormous bet for a nonprofit. And it wasn’t sentimental. It was a deliberate wager that Vertex’s structure-driven approach could be aimed at the defective CFTR protein at the heart of cystic fibrosis, and that this team had a real shot at cracking it.

The partnership didn’t just provide money. It brought infrastructure: access to patient data, trial readiness, and a community that could mobilize around recruitment and endpoints. More than anything, it created alignment—between a for-profit company trying to justify a risky program, and a patient community that needed someone to take the risk.

By the end of these wilderness years, Vertex still hadn’t produced the kind of breakthrough the public markets crave. But it had something more valuable than a good story: a strengthened engine, a sharpened strategy, and a partnership that would soon pull the company out of the valley of death—and into a revolution in cystic fibrosis care.

IV. The Cystic Fibrosis Revolution: Kalydeco and The Breakthrough (2012-2019)

To understand why Vertex’s cystic fibrosis work landed like an earthquake, you first have to understand what cystic fibrosis actually is.

CF is a genetic disease caused by mutations in the CFTR gene. That gene makes a protein that sits on the surface of cells and works like a tiny gate, controlling the flow of salt and water. When CFTR is broken, that balance collapses. Mucus that should be thin and slippery becomes thick and sticky. It clogs airways and ducts, especially in the lungs and pancreas. The downstream effects are relentless: chronic infections, progressive lung damage, and historically, a drastically shortened lifespan.

Here’s the maddening part. Scientists found the CF gene in 1989—the same year Vertex was founded. But identifying the broken gene didn’t automatically translate into fixing what the mutation did to the protein. For more than two decades, CF care was still about managing consequences, not correcting cause: antibiotics for infections, enzymes for digestion, chest physiotherapy to help clear mucus. Patients could fight the symptoms, but no one could get to the source.

This is where Vertex’s core belief—structure, mechanism, design—stopped being a philosophy and became a weapon.

Instead of throwing giant libraries of molecules at the problem and hoping something stuck, Vertex’s scientists went after CFTR’s dysfunction directly. Not every CF mutation breaks CFTR the same way. Sometimes the “gate” is there but won’t open. Sometimes it’s misfolded and never reaches the cell surface at all. So Vertex pursued different classes of molecules for different failure modes. If the gate is stuck shut, you need a potentiator: something that helps it open. If the protein can’t fold correctly or can’t traffic to the surface, you need a corrector: something that helps it form and arrive.

That framework led to Kalydeco, or ivacaftor—the first drug ever approved that treated the underlying cause of cystic fibrosis, not just the symptoms. In January 2012, the FDA approved it for patients with a specific mutation called G551D. The outcomes were striking. Lung function rose. Sweat chloride, a key biomarker of CFTR activity, dropped toward normal. And patients described feeling better in ways that standard CF care simply hadn’t delivered.

It was proof—real proof—that a small molecule could correct the biology of CF.

But it came with a brutal limitation: the G551D mutation is rare. Kalydeco applied to only about six percent of the roughly 30,000 Americans living with cystic fibrosis. Vertex had cracked the concept, but most patients were still waiting.

What came next was not a one-and-done biotech victory lap. It was a campaign.

In 2015, Vertex won approval for Orkambi, combining ivacaftor with a corrector called lumacaftor for patients with the most common CF mutation, F508del, when present in two copies. In 2018 came Symdeko, pairing ivacaftor with a newer corrector, tezacaftor, aimed at improved tolerability and broader efficacy.

This was Vertex’s CF strategy in full view: iterative, multi-generation progress. Each round brought more eligible patients, better outcomes, and fewer drawbacks. Vertex wasn’t trying to get lucky with one miracle drug. It was trying to systematically take a disease apart.

And in the background, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s bold financing model was paying off in a way almost no one had imagined. In 2014, the foundation sold its royalty rights for Vertex’s CF medicines for $3.3 billion—about twenty times its entire 2013 annual budget. The deal didn’t just enrich the foundation; it permanently expanded what a disease nonprofit could be. Venture philanthropy went from a daring experiment to a model other foundations had to take seriously.

Of course, CF also turned Vertex into a lightning rod for pricing. Kalydeco came in at roughly $300,000 per year, and later therapies landed in a similar range. Vertex argued the prices reflected transformative value and funded continued R&D. Critics pointed to the scale of outside support—especially the foundation’s funding—and called the pricing excessive. The tension between rewarding innovation and ensuring access became part of the Vertex story, and it never really went away.

By 2019, one thing was undeniable: Vertex had done what decades of gene discovery and symptom management hadn’t. It showed that a company could build medicines that changed the course of a genetic disease by going straight at the molecular defect.

And then, just as the industry was catching up to what that meant, Vertex was about to raise the bar again.

V. Trikafta: The Game Changer (2019-2024)

Trikafta arrived with the kind of pacing drug development almost never gets. From the point Vertex’s chemists synthesized the key compound to the day the FDA approved the final triple-combination therapy, only three years passed. In an industry where a decade can feel like the minimum sentence, that timeline was jaw-dropping. And it wasn’t because Vertex rushed. It was because Vertex had been running toward this moment for twenty years. By 2019, they knew CFTR inside and out, they knew how to run CF trials, and they knew exactly what a next-generation combination needed to do.

Trikafta combined three molecules: elexacaftor, a next-generation corrector; tezacaftor, the corrector from Symdeko; and ivacaftor, the original potentiator from Kalydeco. The logic was simple and brutally specific to CF biology. Many patients’ CFTR protein doesn’t just have one problem. It’s misshapen, unstable, and underperforms even when it reaches the cell surface. So Vertex didn’t bet on a single “fix.” It stacked mechanisms—help the protein fold better, stabilize it, and then help the channel open and function.

The clinical results landed like a shock. Patients saw an average improvement in lung function of about fourteen percentage points—an effect size that hadn’t shown up in earlier CF therapies. Sweat chloride dropped dramatically, pointing to real restoration of CFTR activity. And beyond the charts: fewer pulmonary exacerbations, better weight gain, and day-to-day changes that medicine doesn’t always measure cleanly. Parents talked about kids who could finally run without stopping. Adults talked about breathing in a way they couldn’t remember ever doing.

In October 2019, the FDA approved Trikafta more than three months ahead of schedule—an unmistakable signal that regulators saw the benefit as exceptional. With that one approval, Vertex jumped from treating slivers of the CF population to reaching roughly 90 percent of people with cystic fibrosis. And for approximately 6,000 people in the U.S., it was the first therapy that addressed the underlying cause of their disease at all.

Jeffrey Leiden, Vertex’s CEO through much of the CF transformation, put it bluntly: “We have conquered a disease.” In biotech, that kind of line usually tempts fate. But in CF, it captured something real. Vertex had taken a disease once synonymous with childhood decline and made it, for most patients, a manageable chronic condition.

The business impact matched the medical one. Trikafta turned Vertex into a different company almost overnight, driving revenue from roughly three billion dollars in 2018 to more than eleven billion by 2024. It wasn’t just a blockbuster; it was rapid adoption powered by transformative outcomes and a CF community that knew exactly what was at stake.

Vertex moved quickly to expand access globally, winning approvals across Europe, Canada, Australia, and other markets. Every new country meant a new round of pricing negotiations and reimbursement debates. Vertex leaned hard into patient support programs and access pathways, partly because the company had built its CF identity around the idea that changing a disease creates an obligation to get the medicine to the people who need it.

And crucially, Vertex didn’t treat Trikafta as the finish line. It treated it as the new baseline.

In December 2024, the FDA approved ALYFTREK, a once-daily triple combination of vanzacaftor, tezacaftor, and deutivacaftor. The headline was convenience—once daily instead of Trikafta’s twice-daily regimen—but the biology mattered too: ALYFTREK delivered a superior reduction in sweat chloride, suggesting even greater correction of the underlying CFTR defect. By early 2025, it had also been approved in the United Kingdom and the European Union, with the EU granting the broadest label by covering patients with at least one non-class I mutation.

Vertex also pushed its next wave of CF science forward. VX-828, its next-generation 3.0 CFTR corrector, entered clinical studies in people with CF, with data expected in the second half of 2026. And for the patients Trikafta still couldn’t reach—those whose mutations produce no functional CFTR protein at all—Vertex partnered with Moderna on VX-522, an mRNA therapy designed to deliver working CFTR protein directly to the lungs. That effort hit a setback in May 2025 when the FDA placed a temporary clinical hold on the multiple ascending dose portion of the Phase 1/2 trial. Vertex said the hold was temporary, and the program continued.

If Kalydeco was proof of concept and Trikafta was the unlock, the bigger story is what came after: serial innovation. Vertex kept upgrading the franchise—expanding eligibility, improving dosing, and taking aim at the remaining untreated patients. That mindset didn’t just build a durable CF business. It built the scientific confidence and commercial muscle Vertex would need for its next act beyond cystic fibrosis.

VI. Beyond CF: The Platform Expansion (2020-Present)

By 2020, Vertex ran into the inevitable question that eventually finds every breakout, single-franchise biotech: what comes next?

Cystic fibrosis had become an engine—medically extraordinary, financially massive. But it was also bounded. The global CF population is finite, around 90,000 people. Even with international launches and younger-patient approvals, the market would mature. Vertex had to show that CF wasn’t a one-time miracle, but proof that its way of doing science could travel.

So the company started placing multiple bets at once, across multiple modalities—small molecules, cell therapies, and gene editing. The targets varied, but the underlying pattern didn’t: pick diseases with huge unmet need, understand the biology deeply, and build something that changes the trajectory, not just the symptoms.

Pain Management: JOURNAVX and the Non-Opioid Revolution

On January 30, 2025, the FDA approved JOURNAVX (suzetrigine). It was a real line-in-the-sand moment for pain medicine: the first new class of acute pain treatment in more than twenty years, and a non-opioid option positioned to deliver relief comparable to opioids.

The stakes here are not subtle. Each year, more than eighty million Americans get prescriptions for moderate-to-severe acute pain, and roughly forty million of those prescriptions are for opioids. The opioid epidemic has killed hundreds of thousands of Americans. And for all the policy attention and public anguish, the on-the-ground reality in clinics has been brutally simple: if you need strong acute pain relief, opioids are often what you get.

Suzetrigine attacks pain differently. It selectively blocks the NaV1.8 sodium channel, a key pathway for transmitting pain signals in peripheral nerves. Importantly, NaV1.8 is found mostly on pain-sensing neurons outside the brain. So the drug aims to stop pain signals at the source without crossing the blood-brain barrier—sidestepping the euphoria, sedation, respiratory depression, and addiction risk that make opioids so dangerous.

Vertex tested suzetrigine in two large trials of roughly a thousand patients each, looking at pain after abdominoplasty and bunionectomy. The headline result: pain relief comparable to hydrocodone-acetaminophen (Vicodin), and both treatments beat placebo. Commercially, the launch was quick out of the gate. In its first year, JOURNAVX topped 500,000 prescriptions and generated about twenty million dollars in revenue in the third quarter of 2025 alone—early innings, but enough to suggest the product has room to grow if prescribing behavior truly shifts.

The policy winds are also changing. Seven states passed laws specifying that opioids should not be preferred over non-opioid therapies when effective alternatives exist. That kind of tailwind—driven by public health urgency rather than marketing muscle—is rare, and it matters.

Vertex is also trying to push suzetrigine beyond acute pain. The FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy designation in diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and Vertex expects to complete Phase 3 enrollment for that indication by the end of 2026. A Phase 2 study in lumbosacral radiculopathy, commonly called sciatica, also produced encouraging results and is expected to advance into pivotal trials.

Type 1 Diabetes: The Cell Therapy Frontier

If JOURNAVX is Vertex extending its small-molecule playbook into a massive new category, Type 1 diabetes is a different kind of ambition. VX-880—now called zimislecel—is a stem cell-derived islet cell therapy designed to replace the insulin-producing cells the immune system destroys in Type 1 diabetes.

The logic is clean. The reality of living with the disease is not. Without pancreatic beta cells, patients have to monitor glucose constantly and dose insulin multiple times a day. It’s exhausting, imprecise, and still leaves people exposed to dangerous swings—including severe hypoglycemic episodes that can cause seizures, loss of consciousness, or death.

Zimislecel aims to restore the missing biology. Vertex manufactures fully differentiated islet cells from stem cells, then infuses them through the hepatic portal vein. Those cells engraft in the liver and begin producing insulin in response to blood sugar—functionally standing in for what the pancreas used to do.

The Phase 1/2 data, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in June 2025, were striking. All twelve treated patients showed restored insulin production, measured by detectable C-peptide. Ten of the twelve—eighty-three percent—no longer needed exogenous insulin at twelve months. Average insulin use across the group fell by ninety-two percent. All patients reached hemoglobin A1C below seven percent and spent more than seventy percent of the time in range. And the most frightening part of many patients’ lives—severe hypoglycemic events—stopped.

If those results hold up at scale, this isn’t incremental progress. It’s the shape of a cure for a disease affecting roughly two million people in the United States. Vertex has initiated the Phase 3 portion of the study, with global regulatory submissions planned for 2026 and the possibility of availability as early as 2027.

There’s also a major catch: zimislecel currently requires chronic immunosuppression so the immune system doesn’t destroy the transplanted cells—similar to organ transplantation. That limits near-term use to patients with the most severe Type 1 diabetes, where the tradeoff makes sense. Vertex is also working on encapsulated cell therapies and immune-evasion approaches that could remove the need for immunosuppression, but those efforts are earlier.

Kidney Disease: Povetacicept and Inaxaplin

Vertex’s push into kidney disease snapped into focus in April 2024, when it acquired Alpine Immune Sciences for $4.9 billion—its largest acquisition to date. The centerpiece was povetacicept, a dual antagonist of BAFF and APRIL, two proteins that play major roles in immune signaling. The lead target is IgA nephropathy, the most common cause of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide, affecting roughly 130,000 people in the U.S. It’s a chronic autoimmune disease: abnormal antibodies deposit in the kidneys, inflammation builds, and over time patients can progress to kidney failure.

After the deal, Vertex moved fast. By the fourth quarter of 2025, it began a rolling submission of a biologics license application to the FDA, with completion expected in the first half of 2026. Povetacicept received Breakthrough Therapy designation, and Vertex plans to use a Priority Review Voucher to cut review time from ten months to six.

In parallel, Vertex is developing inaxaplin for APOL1-mediated kidney disease, a genetically driven condition that disproportionately affects people of African descent. The program advanced into the Phase 3 portion of its adaptive trial in September 2025, with a forty-eight-week interim analysis that could support accelerated approval.

Gene Editing: CASGEVY

CASGEVY—developed with CRISPR Therapeutics—already has its place in the history books: the first CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing therapy approved anywhere. The FDA approved it for sickle cell disease in December 2023 and for transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia in January 2024.

Both diseases trace back to mutations affecting hemoglobin. CASGEVY’s approach is as elegant as it is intense: collect a patient’s own blood stem cells, edit them to switch on fetal hemoglobin production (a form not impacted by the disease-causing mutations), then infuse the edited cells back after chemotherapy clears space in the bone marrow.

The launch has been slower than some expected—not because the science is in doubt, but because delivering the therapy is complex. It requires cell collection, gene editing, conditioning chemotherapy, infusion, and long follow-up. By September 2025, nearly 300 patients had been referred to authorized treatment centers, about 165 had completed cell collection, and 39 had received infusions. Revenue reflected that pace: about seventeen million dollars in the third quarter of 2025, and roughly sixty-two million through the first three quarters of the year.

Vertex is also working to broaden access. In December 2025, it presented the first clinical data in children ages five to eleven at the American Society of Hematology meeting. Regulatory submissions for a pediatric indication are expected to start in the first half of 2026, supported by an FDA Commissioner’s National Priority Voucher.

Taken together, this is an unusually wide expansion for a company that built its name—and its cash machine—on one disease. Four new arenas. Four different modalities. Huge upside, and plenty of execution risk. But it also signals something important about Vertex’s identity: it doesn’t want to be the cystic fibrosis company. It wants to be the company that keeps doing cystic fibrosis-grade transformations—over and over again.

VII. Scientific and Development Philosophy

Walk onto Vertex’s research campus in Boston’s Innovation District and you hear the same thing from just about everyone: the intensity is real. This is not a company that treats R&D as a cost center while it shops for the next asset to buy. Drug discovery is still the center of gravity—by design—because that was Joshua Boger’s original wager back in 1989, and Vertex never abandoned it.

The philosophy is straightforward, and brutally demanding: don’t start by hunting for a drug. Start by understanding the disease. Get to the molecular mechanics first—what’s broken, where it’s broken, and why. Only then do you try to build the molecule, the cell therapy, or the genetic intervention that can actually change the biology.

That sounds like common sense, but it’s not how much of the industry operates. A lot of drug discovery still starts with massive screening: throw huge libraries of compounds at a target and hope the data points you toward something usable. Vertex tends to work the other direction. It begins with structure, binding sites, and mechanism, then designs from there. Cystic fibrosis became the clearest demonstration of that mindset. CFTR doesn’t fail in one uniform way, so Vertex didn’t chase one universal fix. It built correctors and potentiators to match different defects—because it had done the work to understand the defects.

What’s telling is that this way of thinking didn’t stop at small molecules. The Type 1 diabetes program depends on real mastery of islet cell biology, not just optimism about cell therapy. The CASGEVY partnership required more than knowing CRISPR could edit DNA; it required knowing exactly which regulatory switches to flip to restore fetal hemoglobin. Even the move into kidney disease—highlighted by the acquisition of povetacicept—was rooted in a specific biological thesis about how BAFF and APRIL signaling drives disease in IgA nephropathy.

Vertex also talks about its development strategy as a “portfolio of shots on goal,” and here it’s more than a slogan. The company deliberately runs multiple programs in parallel, accepting that some will fail and planning for that reality upfront. It’s a way of reducing existential risk in a business where failure is normal. When something goes sideways—like the clinical hold on VX-522—Vertex doesn’t have to pretend it didn’t happen or bet the company on a single readout. The pipeline is built to absorb hits.

Then there’s patient-centricity, which is easy for pharma companies to say and hard to prove. Vertex’s relationship with the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation created a level of engagement that shaped how the company works: patient registries that influence trial design, endpoints that reflect real lived outcomes, and support programs built early rather than patched on after launch. None of this makes Vertex a charity—Kalydeco’s roughly $300,000 annual price made that clear. But it does create a tighter feedback loop between patient need and scientific priorities than you see at many large companies.

Finally, Vertex’s capital allocation reflects the same long game. Rather than optimizing for near-term earnings by dialing down R&D, it has consistently plowed most of its CF cash flow back into research and development. The bet is simple: keep funding the engine that made CF possible, and it can produce the next franchise—and the one after that. For investors, that can mean less emphasis on maximizing today’s margins, in exchange for the chance at a much larger, more diversified Vertex tomorrow.

VIII. Financial Architecture and Business Model

Vertex’s financial arc is the kind biotech investors dream about and almost never actually get: a company that spent years in the wilderness, then found a true breakthrough—and turned it into more than eleven billion dollars a year in revenue. By 2024, Vertex had put together its tenth straight year of double-digit revenue growth, which is especially rare in an industry where one patent expiration or one new competitor can abruptly end the party.

That growth is still, overwhelmingly, the cystic fibrosis franchise. Trikafta brings in the lion’s share, with ALYFTREK now joining the lineup and the earlier generation products—Kalydeco, Orkambi, and Symdeko—continuing to serve patients in narrower mutation groups or clinical situations. For 2025, Vertex guided to roughly $11.9 to $12.0 billion in total revenue, and notably tightened the range upward from where it started—another sign that demand in CF remained strong.

The natural question is durability. How long can a franchise this concentrated keep throwing off cash?

Part of the answer is legal: Vertex holds composition-of-matter patent protection on its key CFTR modulators that extends well into the next decade. But the bigger part is practical. The capability that built Trikafta wasn’t a single clever molecule—it was decades of accumulated CFTR understanding, trial infrastructure, relationships with the CF community, and hard-won know-how about how to modulate a protein with hundreds of clinically relevant mutations. That combination—patents plus deep disease mastery plus real-world operating infrastructure—creates a moat that’s difficult for would-be competitors, generics, or biosimilars to simply copy and cross.

Vertex has used that cash engine in a way that also explains the business model: rather than harvesting profits and slowing down, it keeps feeding the R&D machine. The spending is significant. In 2024, Vertex recorded $4.6 billion of acquired in-process R&D charges, largely tied to the Alpine Immune Sciences acquisition. For 2025, it guided to non-GAAP operating expenses of about $5.0 to $5.1 billion. And while Vertex has often run a non-GAAP tax rate in the high teens to low twenties, one-time items pulled its 2025 guidance down to about seventeen to eighteen percent.

Diversification is starting to show up in the numbers, even if it’s still early. CASGEVY brought in roughly sixty-two million dollars through the first three quarters of 2025, and JOURNAVX began ramping after its January 2025 approval. Against the CF franchise, those are small contributions today. But strategically, they’re the first proof points that Vertex can commercialize outside CF—and that management’s pitch of future multi-billion-dollar franchises isn’t purely hypothetical. If zimislecel delivers in Type 1 diabetes and povetacicept reaches the market in IgA nephropathy, Vertex could plausibly exit the decade with a half-dozen distinct franchises instead of one.

All of this is enabled by something most biotechs never get: financial self-sufficiency. CF throws off enough cash to fund the pipeline without constant dilution or heavy reliance on debt. That’s what allowed Vertex to do a $4.9 billion deal for Alpine while still running an expansive research agenda. It’s also what gives the company patience—time to run the trials it needs to run, rather than the trials it can afford.

And looming behind the entire financial story is the funding model that helped make it possible in the first place. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s roughly $150 million investment, which ultimately turned into a $3.3 billion royalty-rights sale, didn’t just change CF. It proved that a patient foundation can act like a sophisticated capital allocator, not merely a grantmaking organization. In rare diseases especially—where the science is hard, timelines are long, and commercial outcomes can look uncertain—that example expanded the imagination of what early-stage drug development funding can be.

IX. Leadership Transitions and Culture

When Reshma Kewalramani became CEO of Vertex in April 2020, she walked into a company riding the biggest launch in its history. Trikafta had been on the market for only five months. The CF franchise was exploding. And the world was tipping into the uncertainty of a global pandemic. On top of the operational moment, the appointment carried historic weight: Kewalramani became the first woman to lead a major public U.S. biotech company, and she remains the only woman leading a biopharma company with a market capitalization above one hundred billion dollars.

Her path to the corner office was also different from the typical biotech CEO résumé. Kewalramani is a physician and nephrologist. She joined Vertex in 2017 as Chief Medical Officer after years in clinical practice and medical affairs roles at other pharma companies. That training shows up in how she frames decisions. The question isn’t only, “Can this work?” It’s, “If it works, does it truly change patients’ lives?” That filter matters at a company trying to turn a once-in-a-generation cystic fibrosis success into a repeatable playbook.

Jeffrey Leiden, who had led Vertex through the CF revolution as CEO from 2012 to 2020, moved into the role of Executive Chairman. The transition was unusually calm for biotech, where leadership changes often spark strategy drift or internal churn. Leiden had built the commercial machine that turned Trikafta into a blockbuster. Kewalramani’s mandate was more complex: keep CF strong while building credible second and third franchises that could eventually stand on their own.

Culturally, Vertex has worked hard to project stability in an industry known for volatility. Under Kewalramani, the company has been recognized repeatedly as an employer of choice, including an appearance on Science magazine’s Top Employer list for fifteen consecutive years. It has also landed on the TIME100 Most Influential Companies list and Fortune’s 100 Best Companies to Work For—signals that the culture scales even as the business gets larger and higher stakes.

Kewalramani has also received a slate of personal recognition, including Fortune’s 100 Most Powerful People in Business in 2025, CNBC Changemaker in 2025, and the CED Distinguished Leadership Award. In a sector where outcomes are often attributed to pipelines more than people, those honors reflect how closely her leadership has become tied to Vertex’s post-Trikafta identity: execution, diversification, and staying scientifically serious.

One small moment captured that mindset. At a November 2025 event with Nasdaq CEO Adena Friedman, Kewalramani described herself as a former “AI skeptic” who changed her view as evidence accumulated about AI’s potential in drug discovery. In an industry overflowing with AI hype, that was notable not because it made Vertex sound trendy, but because it signaled something rarer: a willingness to be publicly wrong, then update beliefs without pretending it was the plan all along.

That gets at what Vertex tries to be inside. The culture blends deep scientific rigor with real commercial urgency, and the balance is hard to pull off. The research side operates with academic-level depth and internal peer review. The commercial side moves with speed and customer focus. In many companies, those instincts collide. At Vertex, the friction is meant to be productive, held together by a shared premise: rigorous science only matters if it reaches patients fast enough to change the course of a disease.

X. Playbook: Lessons for Biotech and Investing

Vertex’s journey is a masterclass in building an enduring biotech company. And the takeaways travel well beyond pharmaceuticals into any world defined by long R&D cycles, high failure rates, and advantages that compound over time.

The Power of Focus. Vertex spent more than two decades, and poured billions into, truly mastering one disease before it tried to become something bigger. That depth created the kind of institutional knowledge you can’t shortcut: how CF works at a molecular level, how CF trials should be run, how to support patients on therapy, and how to build trust with physicians. In biotech, the temptation to chase whatever therapeutic area is hot is constant. Vertex largely resisted it until it had real dominance in its core market.

Patient-Centric Innovation. The partnership with the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation wasn’t a branding exercise. It shaped what Vertex worked on, how it designed trials, and how it brought medicines to patients. Companies that treat advocacy groups as PR channels miss what actually matters: lived experience, practical constraints, and the difference between a statistically significant result and a life-changing one. You can see that orientation in Vertex’s current targets—sickle cell disease, Type 1 diabetes, IgA nephropathy—places where patients still don’t have good options.

Strategic Patience. Vertex went public in 1991 and didn’t generate meaningful product revenue until 2012. That’s a twenty-one-year gap—an eternity in public markets. Plenty of investors gave up. Plenty of observers wrote the company off. The lesson isn’t that patience magically turns into profits—many biotechs stay patient and still fail. The lesson is that patience, paired with real scientific capability and disciplined capital allocation, can create outcomes that look impossible from the middle of the story.

Platform Thinking. Vertex’s wins weren’t isolated events. Capabilities built in one era became leverage in the next. The structure-based design chops developed on HIV targets helped enable the CFTR modulator program. The trial playbook and commercial infrastructure built for Kalydeco made it possible to move fast with Trikafta. The regulatory experience earned through repeated CF approvals helped as Vertex brought CASGEVY and JOURNAVX into the world. Each success didn’t just produce revenue—it built a platform for the next launch, and the compounding effect is the whole point.

The Venture Philanthropy Model. The CF Foundation’s bet on Vertex proved that patient foundations can do more than fund basic research and raise awareness. They can underwrite drug development directly, take financial risk, and—if it works—recycle returns into the next wave of science. It won’t fit every disease or every foundation. But in rare diseases, where uncertainty keeps traditional capital on the sidelines, it can change what’s even possible.

Serial Innovation over Single Bets. Vertex didn’t treat Kalydeco as the finish line. It treated it like version one. Then came Orkambi, Symdeko, Trikafta, and now ALYFTREK—each generation expanding the eligible population and improving outcomes. That habit of relentless iteration built a franchise with unusual durability. It also created real switching costs: not just economic, but clinical and operational, reinforced by years of experience across the CF care ecosystem.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case and Competitive Analysis

The Bull Case

Vertex’s bulls see something rare in biotech: a company with a dominant, cash-gushing franchise today, and a pipeline that could plausibly produce multiple meaningful second acts.

Cystic fibrosis is still the foundation. It continues to benefit from geographic expansion, pediatric label extensions, and the transition to ALYFTREK’s once-daily dosing. But with more than ninety percent of eligible patients in major markets already on Vertex therapy, the growth story increasingly shifts from “finding new patients” to expanding access—into younger ages, into additional geographies—and sustaining pricing and reimbursement.

The real bull case is that Vertex is no longer trying to be a one-franchise company. JOURNAVX puts Vertex into a massive pain market that has been stuck with the same brutal tradeoff for decades: strong relief usually means opioids. If suzetrigine can extend from acute settings into chronic indications like diabetic neuropathy, the opportunity could dwarf CF. Zimislecel, if Phase 3 confirms what early data suggests, could look like the first functional cure for Type 1 diabetes. Povetacicept goes after IgA nephropathy, where patients still face progression risk and limited options. If even one of these becomes a durable franchise, Vertex’s revenue base starts to look very different. If two or three hit, the company’s dependence on CF meaningfully fades.

Strategically, bulls argue Vertex has real competitive “powers” that are hard to copy. In Hamilton Helmer’s language, Vertex has counter-positioning against incumbents whose models lean heavily toward symptom management rather than disease modification. It has cornered resources in CFTR know-how and deep relationships within the CF ecosystem. The CF business also gives it scale economies—experienced development teams, regulatory muscle, and a global commercial platform that can launch products faster than most biotechs. And its habit of serial innovation creates switching costs, because patients and physicians don’t just adopt a pill—they adopt a whole regimen and support system.

Under Porter’s lens, Vertex looks especially strong where it matters most today: in CF. New entrants face steep scientific and regulatory barriers. Payers push hard, but transformative outcomes blunt that leverage. Substitutes like gene therapy exist in theory but remain far from displacing a widely adopted oral therapy. Rivalry inside CF is low—though rivalry is higher in the new markets Vertex is entering, where incumbents are already entrenched.

The Bear Case

Bears start with a simple point: even after all the pipeline progress, Vertex is still a cystic fibrosis company in financial terms.

CF has a built-in ceiling. The patient population is finite, and Vertex already reaches most eligible patients in the U.S. and Europe. That means growth naturally slows as the franchise matures—while the timeline for new programs to become large, repeatable revenue engines is still uncertain.

Then comes execution risk, and it’s everywhere. JOURNAVX has to change prescribing behavior in a field where opioids are deeply ingrained, despite their risks. Zimislecel’s need for chronic immunosuppression is a major limiter on who can realistically take it. CASGEVY is clinically powerful but operationally heavy; complex manufacturing and treatment logistics make scaling inherently harder. Povetacicept, acquired as part of a $4.9 billion deal, has to deliver in Phase 3 to earn its price tag.

Pricing and access remain another pressure point. Vertex’s CF drugs are among the most expensive medicines in the world, and drug-pricing politics are not going away. Over time, Medicare negotiation under the Inflation Reduction Act could become a real factor. Internationally, Vertex faces reimbursement negotiations and reference-pricing dynamics that can compress prices as it expands.

And while Vertex built a moat in CF over decades, that moat doesn’t automatically transfer. Pain is crowded. Kidney disease is crowded. Gene and cell therapy are crowded. In those arenas, Vertex is competing with well-funded players who have been there for years—and the company will have to prove it can win outside the ecosystem it essentially created.

KPIs to Watch

If you want a simple dashboard for whether Vertex’s next era is working, three metrics do most of the work.

First: non-CF revenue as a percentage of total revenue. It will be small at first, but by 2027–2028 it needs to show a clear upward slope.

Second: JOURNAVX prescriptions and revenue growth. This is the cleanest real-time signal of whether Vertex can build a meaningful commercial franchise outside CF.

Third: pipeline advancement rate—how often programs move into pivotal trials and, ultimately, into approvals. Vertex’s story has always been about the engine. This metric tells you if that engine is still producing.

XII. The Future: What's Next for Vertex

Vertex’s next few years are packed with moments that can meaningfully change the company’s shape. The first comes fast: Vertex reports full-year 2025 results on February 12, 2026, alongside its 2026 financial guidance. Investors will be listening for more than a revenue number. They’ll want to know how quickly non-CF products are ramping, how hard Vertex plans to keep pressing on R&D spend, and whether management’s confidence matches the expanding scope of the pipeline.

On the product and regulatory front, the calendar is crowded. Vertex expects to complete the povetacicept BLA submission in the first half of 2026. With priority review, that timeline could put a decision before year-end. Inaxaplin’s interim analysis in APOL1-mediated kidney disease could also set up an accelerated approval filing. And two important expansions are expected in early 2026: CASGEVY submissions to broaden into pediatric use, and a Trikafta label extension to children aged one to two.

Beyond those near-term events, the real franchise-defining readouts are still ahead. Zimislecel’s Phase 3 data is the critical test of whether Vertex can translate early Type 1 diabetes results into a scalable, durable therapy—potentially putting it at the center of cell therapy for diabetes. In cystic fibrosis, VX-828 data expected in the second half of 2026 will show whether Vertex can keep pushing CFTR modulation forward, even after Trikafta and ALYFTREK raised the standard. And in pain, suzetrigine’s Phase 3 program in diabetic neuropathy—where enrollment is expected to complete by the end of 2026—will help answer the biggest open question about JOURNAVX: is it an acute-care breakthrough, or the foundation of a much larger chronic-pain franchise?

Geography is another lever Vertex can still pull. Historically, the company has been concentrated in the United States and Western Europe. But CF and Vertex’s newer disease areas have meaningful patient populations across Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Building commercial capability there takes time and capital, but it also extends the runway for the products Vertex already has.

Underneath all of this is a technological posture that’s becoming a strategy in its own right. Vertex is investing across small molecules, biologics, cell therapies, and gene editing—an unusually wide toolkit for a company that once defined itself by structure-based design. That breadth gives Vertex options: it can push whichever modality proves most productive, and it’s better positioned than most to live in a future where therapies aren’t just one “type,” but combinations of approaches.

And then there’s dealmaking. M&A is likely to remain part of the playbook. The Alpine acquisition showed Vertex is willing to pay up for programs that fit its scientific thesis and that it believes it can develop and commercialize well. With the cash generation of the CF franchise behind it, Vertex has the financial capacity to do more—if it can find assets that truly belong in the same long-term architecture.

XIII. Epilogue

Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ arc—from a two-person startup founded by a Merck scientist convinced Big Pharma had lost its edge, to a hundred-billion-dollar company with six approved products across four therapeutic modalities—is one of modern biotech’s defining stories. It’s what you get when scientific conviction collides with urgent patient need, when capital is deployed with both ambition and restraint, and when a culture is built to think in decades, not quarters.

Cystic fibrosis is the achievement that made Vertex, and its impact reaches far beyond CF. Vertex proved that a fatal genetic disease could be pulled back from the edge and turned, for most patients, into a manageable chronic condition. It validated venture philanthropy as a serious engine for drug development, not just a charitable add-on. And it vindicated rational drug design—the 1989-era belief that if you understand the structure and mechanism deeply enough, you can build the right medicine on purpose, not by accident.

But the story doesn’t end with CF. If anything, it gets harder.

Vertex’s push into pain, diabetes, kidney disease, and gene editing is both the company’s biggest opportunity and its biggest test. If even a couple of those bets become durable franchises, Vertex won’t just be the cystic fibrosis company that pulled off a miracle. It will be one of the premier pharmaceutical companies in the world. If they don’t, the risk is obvious: a business still anchored to a single franchise in a disease with a finite patient population.

The reason Vertex is worth studying—whether you’re an investor, an operator, or someone trying to understand how innovation actually happens in medicine—is that its success wasn’t luck, and it wasn’t destiny. It was decades of deliberate choices: science over shortcuts, focus before diversification, and reinvesting profits into the next set of hard problems rather than optimizing for the easiest near-term win. None of those choices guaranteed success. But together, they created the conditions where transformative science could finally become transformative medicine.

XIV. Links and Resources

- Barry Werth, The Billion-Dollar Molecule: The Quest for the Perfect Drug (Simon & Schuster, 1994)

- Barry Werth, The Antidote: Inside the World of New Pharma (Simon & Schuster, 2014)

- Vertex Pharmaceuticals Investor Relations: investors.vrtx.com

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation: cff.org

- New England Journal of Medicine: Zimislecel Phase 1/2 data (June 2025)

- FDA approval announcements: JOURNAVX (January 2025), ALYFTREK (December 2024), CASGEVY (December 2023)

XV. Recent News and Developments

- February 12, 2026: Vertex is scheduled to report Q4 and full-year 2025 financial results, along with 2026 guidance.

- December 2025: At the ASH Annual Meeting, Vertex and its partners presented the first CASGEVY clinical data in children ages 5–11.

- November 2025: CEO Reshma Kewalramani discussed Vertex’s evolving approach to AI in drug discovery at a Nasdaq-hosted event.

- September 2025: Inaxaplin advanced into the Phase 3 portion of its adaptive trial for APOL1-mediated kidney disease.

- Q4 2025: Vertex initiated a rolling BLA submission for povetacicept in IgA nephropathy.

- Q3 2025: Vertex reported total revenue of $3.08 billion; JOURNAVX surpassed 500,000 prescriptions; CASGEVY generated $17 million in revenue.

- June 2025: Phase 1/2 zimislecel data published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported an 83% insulin independence rate.

- May 2025: The FDA placed a temporary clinical hold on the multiple ascending dose portion of the VX-522 mRNA therapy trial.

- March 2025: ALYFTREK received approval from the UK MHRA.

- January 2025: The FDA approved JOURNAVX (suzetrigine), a first-in-class non-opioid pain treatment.

- December 2024: The FDA approved ALYFTREK for cystic fibrosis.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music