Snowflake: The Data Cloud Revolution

I. Introduction & Episode Framing

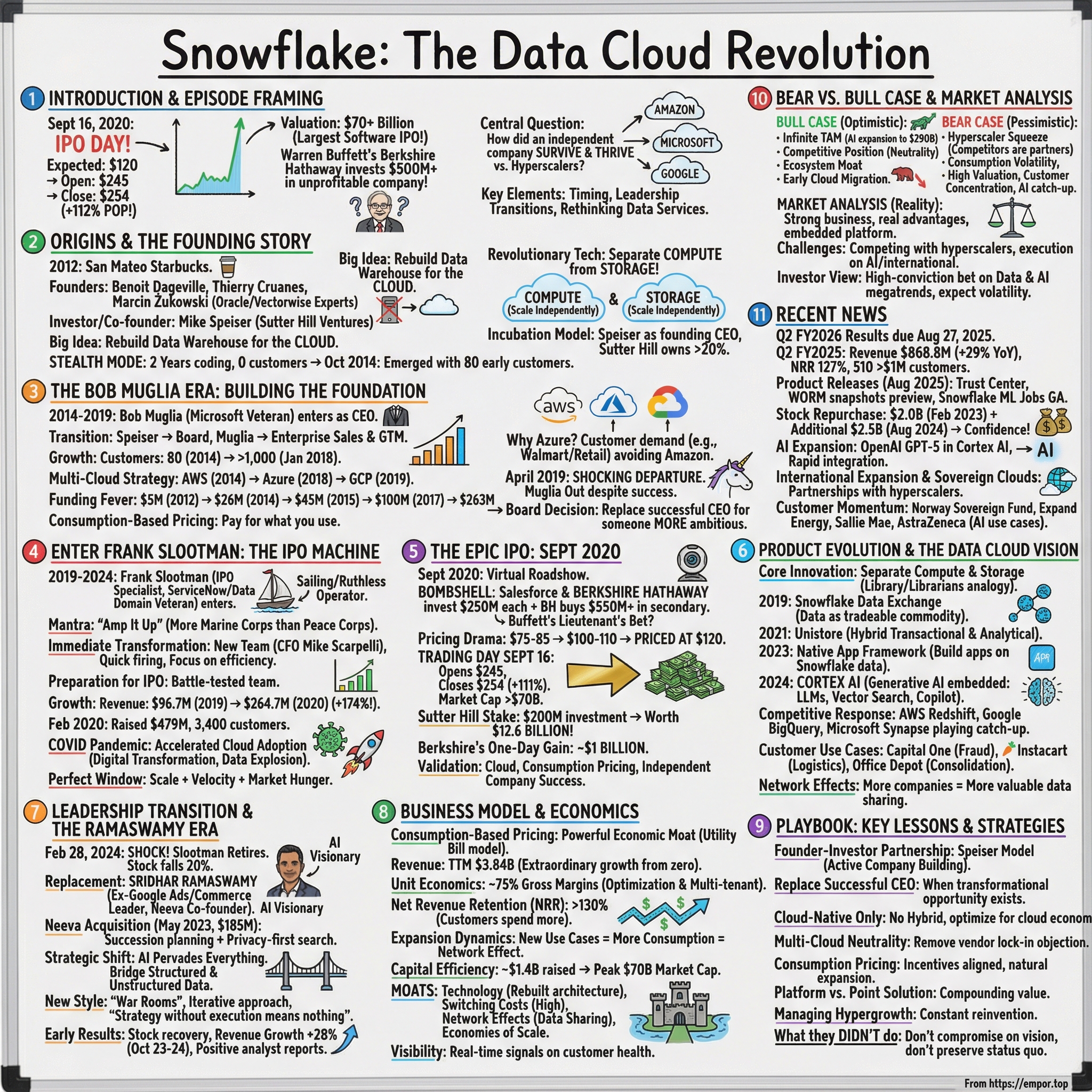

Picture this: September 16, 2020. The market is about to open, and Wall Street is bracing for a big software IPO. But almost no one outside the data-infrastructure world has heard of the company at the center of it: Snowflake.

The night before, the deal prices at $120 a share—already above what most people expected. Then trading starts. Snowflake opens at $245 and finishes the day at $254, up 112%. In the span of a single session, Snowflake is suddenly valued north of $70 billion. It’s the largest software IPO ever, and one of the rare ones that more than doubles on day one.

And then there’s the part that really breaks everyone’s mental model: Berkshire Hathaway is involved. Warren Buffett’s firm—famous for steering clear of tech, and even more famous for steering clear of IPOs—had agreed to buy hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of Snowflake shares and picked up additional shares in a secondary transaction. A not-yet-profitable cloud data company is suddenly sitting in a portfolio that was built on banks, railroads, and consumer staples.

So how did it happen? How did three database engineers—working in stealth, with essentially no commercial footprint early on—end up building the company Wall Street couldn’t get enough of?

The answer isn’t just the tech, though the tech mattered. Snowflake’s core architectural bet—separating compute from storage so customers could scale each independently—was a clean break from how data warehouses had always worked. But this story is also about timing, about cloud platforms reshaping the rules of enterprise software, and about leadership decisions that were anything but calm and incremental.

Snowflake is a San Mateo-based company that didn’t merely build a better data warehouse. It helped define what it called the Data Cloud: a centralized place to analyze and govern data, even when that data lives across different public clouds. It’s a three-act story: the founders with the vision, the enterprise CEO who built the foundation, and the IPO operator who turned Snowflake into a Wall Street event.

Along the way, we’ll see how Snowflake pulled off a near-impossible balancing act—running on Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform while also pushing into territory those giants desperately wanted to own. And we’ll dig into the bigger question underneath all of it:

In a world dominated by hyperscale cloud providers with effectively unlimited resources, how did an independent software company not only survive—but become one of the most valuable software companies on the planet? The answer carries lessons about founder-investor dynamics, product strategy in a platform era, and the controversial moment when a board decides that “doing great” isn’t the same thing as “becoming iconic.”

II. Origins & The Founding Story

Snowflake didn’t start in a garage. It started in a Starbucks in San Mateo.

It was 2012, and Benoît Dageville—a French database architect who’d spent 16 years inside Oracle—sat down with Mike Speiser of Sutter Hill Ventures. Dageville wasn’t shopping a startup idea. He was interviewing with another company when Speiser heard about him and asked to meet. Speiser had a different agenda.

What if you could rebuild the data warehouse from scratch for the cloud?

It sounds obvious now. In 2012, it wasn’t. The “data warehouse” was still a heavy, on-premise institution: expensive, rigid, and designed around the assumptions of physical servers. Dageville had watched enterprises try to drag those systems into the cloud and get the worst of both worlds—complexity without elasticity, costs without the promised efficiency, scaling that felt more like planning a construction project than clicking a button.

Dageville wasn’t alone. He teamed up with Thierry Cruanes, another Oracle data architect, and Marcin Żukowski, a database builder who had co-founded Vectorwise and knew columnar tech cold. All three had the same conviction: the cloud didn’t just need a hosted version of yesterday’s warehouse. It needed a new one.

Speiser’s contribution wasn’t merely writing a check. Sutter Hill had developed what it called an “incubation model,” and Snowflake was a textbook example. Speiser served as Snowflake’s founding CEO from 2012 to 2014, effectively acting as an operational co-founder while the engineers built. Within Sutter Hill, Speiser ran on what he described as a “40% model”: two days a week dedicated to the company being originated, the rest split across the broader portfolio. This wasn’t passive venture capital. It was hands-on company construction.

Then came the big technical bet. Snowflake would separate compute from storage.

In the old world, those two were chained together. Need more processing power to run bigger queries? You’d typically have to buy more storage along with it. Need more storage for more data? You’d end up paying for more compute you didn’t necessarily need. Snowflake wanted to break that linkage so customers could scale each independently and pay for what they actually used.

The early days were almost unnervingly quiet. For the first year, the team stayed in full stealth. They didn’t talk to customers. They didn’t sell anything. They just built.

Snowflake incorporated in July 2012, and in August Sutter Hill led its $5 million Series A. And Sutter Hill’s commitment wasn’t symbolic: by the time Snowflake reached its IPO, the firm owned more than 20% of the company—an unusually large stake that reflected how deeply involved it had been from the beginning.

By October 2014, Snowflake finally emerged from stealth. When it did, it wasn’t stepping into the light empty-handed. It already had 80 organizations using the product—early believers willing to trust a radical new architecture from a company that had barely existed in public.

There’s something important in that origin story. This wasn’t a campus-born consumer app. It was a company started by seasoned enterprise technologists—people who’d lived the pain firsthand—paired with a venture capitalist who didn’t just fund the idea, but helped operationalize it. A new kind of founding team for a new kind of software era.

III. The Bob Muglia Era: Building the Foundation (2014-2019)

By mid-2014, Snowflake was getting ready to step out of stealth. The product vision was bold, the architecture was different, and early users were already kicking the tires. But to turn that into a real enterprise company, Mike Speiser made a defining call: bring in a CEO who had done it at the highest level.

In June 2014, Snowflake hired Bob Muglia.

Muglia wasn’t just “an experienced operator.” He’d spent 23 years at Microsoft, including running the Server and Tools Business—one of the company’s most important franchises. After that, he served as CEO of Juniper Networks. In other words: if Snowflake was going to ask the Fortune 500 to trust a startup with their most sensitive asset, their data, it needed a leader who could speak enterprise fluently and build an organization that could deliver.

His arrival also marked a clean handoff. Speiser stepped back into a board role after incubating Snowflake through its most fragile stage. Now the job was less about invention and more about execution: building go-to-market, proving reliability at scale, and translating a technical advantage into a repeatable sales machine.

In June 2015, Snowflake launched its first product: its cloud data warehouse. From there, the company’s traction accelerated fast. Snowflake had emerged from stealth in October 2014 with about 80 organizations using it. By January 2018, that number had grown to more than 1,000 customers.

One of Muglia’s smartest moves was strategic, not just technical: multi-cloud. Snowflake ran on Amazon Web Services from 2014, expanded to Microsoft Azure in 2018, and added Google Cloud Platform in 2019. That positioning mattered because it turned Snowflake into a neutral layer—something enterprises could adopt without feeling like they were picking sides.

And the demand for that neutrality was real. Adding Azure wasn’t a theoretical “optionality” play; it came from customers, especially in industries that competed with Amazon and didn’t want to build more of their future on AWS. Muglia pointed to situations like Nielsen: already using Snowflake on AWS, but wanting to use it on Azure for a new product serving retail customers. As he put it, some of those customers—“particularly a large one based in Arkansas”—had strong feelings about Amazon. That was Walmart.

As adoption grew, so did Snowflake’s funding momentum. After the initial $5 million Series A in 2012 and a $26 million round in October 2014, the raises kept getting bigger: $45 million in June 2015, $100 million in April 2017, then a major milestone in January 2018—$263 million at a $1.5 billion valuation, officially making Snowflake a unicorn. In October 2018, Snowflake raised another $450 million, pushing its post-money valuation to about $3.9 billion.

Analysts noticed. Donald Farmer of TreeHive Strategy credited Muglia’s tenure with “outstanding commercial growth,” driven by high customer satisfaction, smart pricing, and effective marketing. A big part of that was the consumption-based model Snowflake leaned into: customers paid for what they used, which lowered adoption friction and let spending expand naturally as Snowflake became more embedded.

Then came the twist.

In April 2019, despite the growth, despite the funding success, despite taking Snowflake to roughly a $4 billion valuation, Muglia was out. It was the kind of move boards rarely make when things are working—and the kind of move that signals something important: “great” isn’t the same as “as big as this can possibly get.”

Snowflake’s directors believed the company needed a different kind of leader for the next phase. In Mike Speiser’s words at the time, “Snowflake is one of the most significant new companies in Silicon Valley,” and he said they were “thrilled” to have the next CEO take the helm.

That next CEO was Frank Slootman.

IV. Enter Frank Slootman: The IPO Machine (2019-2024)

Frank Slootman was sailing—literally—when Mike Speiser called.

Slootman, a 60-year-old Dutch-born executive, had already built a very specific reputation in Silicon Valley: come in, sharpen the company, and take it public. He’d done it before, more than once. After stepping down from ServiceNow in 2017, he’d drifted away from the operating grind and into competitive sailing, the rare arena where he could be intense without being on a quarterly clock.

Then Speiser offered him Snowflake.

It was a jarring move from the board’s side, too. Snowflake was growing fast, the product was loved, and Bob Muglia had helped turn a technical vision into a real enterprise business. Boards don’t usually replace that kind of CEO. They do it when they think the ceiling is higher than the current trajectory—and when they believe a different kind of leader is needed to reach it.

Slootman’s resume explained why Snowflake made the bet. His first CEO role was at Data Domain in 2003, where the company raised funding to avoid bankruptcy and then grew revenue for the next four years. Under his watch, Data Domain went public in 2007, and in 2009 he left as part of EMC’s acquisition. Then came ServiceNow. From 2011 to 2017, Slootman served as CEO and President, taking it from around $100 million in revenue, through an IPO, to $1.4 billion.

Even he didn’t expect to jump back in.

“I didn’t see it coming,” Slootman said of the Snowflake opportunity. He wasn’t looking for another CEO job. He’d stepped away, had no plan, and was trying—at least temporarily—to live without the constant operational pull. He was out racing his sailboat, The Invisible Hand, which he’d led to victory in the 2017 Transpac Honolulu race. But Speiser knew exactly who he was calling, and exactly what kind of challenge would get his attention: a startup that had built something technically extraordinary, and now needed to scale its commercial ambition to match.

Slootman took the job. He even sold some of his sailboats and gave others away. This wasn’t going to be a part-time engagement.

What followed inside Snowflake was fast and unsentimental. Slootman had a reputation for moving aggressively—especially on talent—and Snowflake was no exception. The backchannel chatter was that he’d bring in his own trusted team. And that’s largely what happened. Nearly all the big changes were made in his first 90 days.

One of the first was a familiar name: Mike Scarpelli, his long-time finance partner, joined as CFO. Scarpelli had worked with Slootman before—at ServiceNow and at Data Domain—and the pairing signaled what Snowflake was optimizing for now. This wasn’t just “keep growing.” This was “get the company into public-company shape.”

Slootman’s operating philosophy had a name: “Amp It Up.” It later became the title of his business book, but inside Snowflake it was a directive, not a slogan. He described himself as “more Marine Corps than Peace Corps,” and the company began to run that way—higher urgency, tighter accountability, and zero patience for drag.

The results showed up quickly. On February 7, 2020, Snowflake raised $479 million. Around that time, it had 3,400 active customers. Growth was surging: revenue rose from $96.7 million in 2019 to $264.7 million in 2020. The pace stayed intense into the first half of the following year, when revenue growth continued to triple digits. And the customer base wasn’t just expanding—it was deepening. By the end of July, Snowflake had 56 customers spending at least $1 million over the previous 12 months, more than doubling from the prior year.

But Slootman didn’t treat growth as permission to relax. If anything, it was proof the company could be pushed harder. He was famously intolerant of ineffective sales execution, and he acted accordingly.

Snowflake’s largest customers became proof points for the public-market story it was building. Capital One, which accounted for 11% of Snowflake’s revenue as of January, had migrated its data analytics in 2017 and expanded usage across the bank, from personalized recommendations to real-time marketing. Cisco was another example of the consumption model doing what it was designed to do: it multiplied its Snowflake spending nearly 40-fold in a year, reaching $4.8 million.

By mid-2020, the world had changed. COVID was ripping through every industry, and companies were accelerating cloud adoption out of necessity. It turned out to be a strange kind of tailwind for Snowflake: enterprises were digitizing faster, data volumes were exploding, and public markets were hungry for clean, high-growth cloud stories.

Slootman wasn’t going to rush the moment. He said the company was waiting for the right time because, when it went out, he wanted Snowflake presented “in its best form possible” rather than forcing an early debut.

That was the setup. A company with breakaway growth, a multi-cloud posture the hyperscalers hated, and a CEO built for the roadshow.

Next came the part that turned Snowflake from a hot startup into a full-blown Wall Street spectacle.

V. The Epic IPO: September 2020

Snowflake’s roadshow was virtual—a first for a major tech IPO. Frank Slootman wasn’t pacing conference rooms in Manhattan. He was pitching the biggest software IPO in history through a webcam, from a plain, nondescript room in Montana. It was September 2020. The world was deep into the pandemic. For a company built entirely in the cloud, the format felt strangely fitting.

The backdrop was just as unusual. COVID had slammed the accelerator on cloud adoption. Companies that once talked about “multi-year digital transformation” suddenly needed remote work, e-commerce, and real-time analytics to function at all. Cloud migration timelines collapsed. Data volumes spiked as businesses tried to make sense of consumer behavior that was changing week to week. For Snowflake, this wasn’t a headwind. It was a demand shock in exactly the direction they’d built for.

Then came the headline that made even seasoned Wall Street people do a double-take. On September 8, 2020, Snowflake announced that Salesforce and Berkshire Hathaway would each buy $250 million of stock alongside the IPO. And Berkshire wasn’t stopping there: it also agreed to buy an additional 4.04 million shares from an existing stockholder in a secondary transaction. At the midpoint of Snowflake’s expected IPO pricing range, that would put Berkshire’s stake at more than $550 million.

The Buffett angle was the part nobody could quite square. Berkshire wasn’t known for jumping into newly public tech, and Buffett’s reputation was built on disciplined, conservative value investing—not on paying up for a fast-growing company without profits or a public track record. Yet Berkshire was here, anchoring the deal.

Most observers assumed the decision likely came from Buffett’s investment lieutenants, Todd Combs and Ted Weschler. But whoever pushed it through, the signal was unmistakable: if Berkshire was willing to show up, Snowflake wasn’t just another cloud IPO. It was being treated like a category-defining one.

As the IPO approached, the pricing story became its own kind of drama. The initial range was $75 to $85 per share. Then it moved up to $100 to $110. Finally, Snowflake priced at $120—above even the revised expectations.

And then, on September 16, 2020, the market opened.

Snowflake shares began trading at $245—more than double the IPO price. By the end of the day, they closed at $254, up 112%. In a single session, Snowflake was worth more than $70 billion. The company raised $3.4 billion and became the largest software IPO ever—and the largest one to double on its first day of trading.

For the early believers, it was a jaw-dropping payoff. Sutter Hill Ventures owned 20.3% of Snowflake’s outstanding shares. After investing less than $200 million, the firm suddenly held a stake worth about $12.6 billion. Mike Speiser’s incubation model—patient, hands-on, years in stealth—had just become one of the biggest venture wins in modern history.

Berkshire’s math looked pretty good too. It bought $250 million of Snowflake at the IPO price and then picked up the additional 4.04 million shares in the secondary transaction. With the stock spiking as high as $319 that day, Berkshire’s paper gains quickly became the kind of number you normally associate with entire portfolios, not a single trade.

But the real point of the IPO wasn’t the spectacle or the money. It was validation. Validation that enterprises were committing their most important data workloads to the cloud. Validation that consumption-based pricing could power expansion at scale. And, maybe most importantly, validation that an independent company could become a core layer of the cloud era—even while running in the shadow of Amazon, Microsoft, and Google.

Slootman had done exactly what Snowflake hired him to do. He took the machine public. Now the question was: what do you build once you’ve earned that kind of platform-level credibility?

VI. Product Evolution & The Data Cloud Vision

By the time Snowflake hit the public markets, the IPO story was already legendary. But the reason it could justify that kind of belief comes down to one deceptively simple idea: compute and storage shouldn’t be glued together.

Think of old-school data warehouses like a library where the shelves and the staff are a single unit. If you want faster service—more people to help answer questions—you’re forced to build more shelving too. Even if you don’t need it. Systems like Oracle and Teradata were built around that coupling, because that’s how on-prem hardware worked.

Snowflake’s breakthrough was to separate the shelves from the staff. Store data cheaply, scale compute up when you need it, and scale it back down when you don’t. Customers could keep enormous amounts of data sitting in the cloud and only pay for serious processing when they were actually running serious work. It wasn’t just a performance upgrade. It changed the economics and the operating model of analytics.

Then Snowflake took the next step: it tried to turn a data warehouse into a network.

In June 2019, it launched Snowflake Data Exchange. The pitch was bold: stop treating data like something you hoard, and start treating it like something you can share—securely—without copying it all over the place. The idea was that a retailer could pull in third-party data like weather or demographics to forecast demand, healthcare companies could collaborate on research, and financial firms could subscribe to alternative datasets, all while keeping governance intact.

From there, Snowflake kept expanding the definition of what the platform was.

In 2021, it launched Unistore, a hybrid workload that combined transactional and analytical operations in the same system. That’s Snowflake stepping into territory traditionally owned by operational databases—pushing the argument that you shouldn’t have to run one system for transactions and another for analytics if your business increasingly needs both in real time.

In 2023, Snowflake introduced the Native App Framework, letting developers build, distribute, and monetize applications that run inside a customer’s Snowflake account. That mattered because it flipped a core enterprise-software constraint on its head: developers could ship apps to where the data already lived, instead of dragging sensitive data out into yet another system. It nudged Snowflake from “warehouse” toward “platform.”

And then came the shift that shaped the next chapter: AI. In 2024, Snowflake launched Cortex, a set of generative AI services embedded in the platform, including access to large language models, vector search, and model deployment capabilities. The message was clear: the future wasn’t just asking better queries. It was building systems that could reason over enterprise data, search it in new ways, and automate analysis.

Cortex also aimed to widen the funnel of who could get value out of data. Snowflake described it as bringing AI models, LLMs, and vector search to users across skill levels, and pairing that with LLM-powered experiences. One example was Snowflake Copilot, an assistant (in private preview) designed to generate and refine SQL using natural language—so an analyst could ask a question, have Copilot draft the query against the right tables, and then iterate through conversation until the result matched the task.

The hyperscalers didn’t ignore any of this. AWS, Google, and Microsoft all moved to strengthen their own warehouse offerings—adding capabilities and repositioning products like Redshift, BigQuery, and Azure Synapse. But the scramble was telling: Snowflake had forced the category forward, and everyone else had to respond on Snowflake’s terms.

The customer stories show why this platform framing resonated. As of November 2024, Snowflake said it had 10,618 customers, including more than 800 members of the Forbes Global 2000, and that it processed 4.2 billion daily queries. Capital One used Snowflake for real-time fraud detection across millions of transactions. Instacart built its data infrastructure on Snowflake to process massive event volumes and improve personalization and operations. Office Depot consolidated dozens of data systems into a single Snowflake environment and dramatically reduced query times.

That’s the Data Cloud vision in practice: as more companies standardize on the same layer, sharing becomes easier, governance becomes more consistent, and data becomes something closer to a networked asset than a pile of disconnected silos. Snowflake didn’t just build a warehouse that scaled. It tried to make data interoperable—and then built a platform around the idea that, in the cloud era, the most valuable datasets don’t live alone.

VII. Leadership Transition & The Ramaswamy Era (2024-Present)

The news hit on February 28, 2024, on what should’ve been a routine earnings call. Frank Slootman—the CEO who had taken Snowflake from a roughly $4 billion valuation into the rare air of a peak market cap above $100 billion—was retiring.

Wall Street’s reaction was immediate and visceral. The stock dropped about 20% in after-hours trading, the worst one-day fall in the company’s history.

Slootman’s own numbers underscored just how big this era had been. His total compensation in 2023 was $23.7 million, almost entirely in stock and option awards. As of February 9, he owned 10.6 million Snowflake shares. At that Wednesday’s close, the stake was worth about $2.4 billion.

But the real jolt wasn’t that Slootman was leaving. It was who Snowflake picked to replace him.

Sridhar Ramaswamy, 57, wasn’t an “IPO machine” or a classic enterprise-software operator. He was a technologist. He’d spent 15 years at Google, most recently leading the ads and commerce business until 2018—work that sat at the center of some of the most advanced machine-learning systems on the planet, and the engine behind the bulk of Alphabet’s revenue.

After Google, he co-founded Neeva in 2019, a consumer search engine aimed at challenging Google with a privacy-first approach. Neeva later shut down its product, and Snowflake acquired the company for $185 million, according to a filing.

Suddenly, that acquisition read differently. What looked like a modest acqui-hire in May 2023—Snowflake agreed then to buy privacy-focused Neeva for $185 million—turned into a clear piece of succession planning. On February 28, 2024, the Neeva cofounder was now CEO of Snowflake.

Slootman made the rationale explicit. “There is no better person than Sridhar to lead Snowflake into this next phase of growth and deliver on the opportunity ahead in AI and machine learning,” he said. “He is a visionary technologist with a proven track record of running and scaling successful businesses.”

With Ramaswamy, Snowflake’s center of gravity shifted. The company wasn’t just layering AI features onto the existing Data Cloud pitch. Ramaswamy framed AI as something that now “pervades everything that is happening in Snowflake”—a reminder that in enterprise, there’s no AI strategy without a data strategy. If the data lives in Snowflake, then the models, the apps, and the workflows increasingly want to live there too.

His operating cadence changed as well. Where Slootman was famous for his blunt, top-down urgency, Ramaswamy introduced weekly “war rooms”—cross-functional sessions pulling in engineering, product, marketing, and sales. The goal was tight iteration with real customers: “We said, ‘We’re going to meet every week, we’re going to identify a set of customers that we want to push [products] to, and we’re going to learn.’”

Ramaswamy described it as learning faster without lowering standards. “One of the biggest changes is how we get to be a more iterative company,” he said. “That doesn’t mean release half-baked products, that means pay extra attention to what are the components we need to build right now, release, get feedback on, make sure they are rock-solid before we build the next one.”

The near-term market read-through was rough. Snowflake forecast first-quarter product revenue of $745 million to $750 million, below what analysts were expecting. It also guided to a first-quarter adjusted operating margin of 3%, versus estimates around 7.2%. Investors heard “slower” and sold first, asked questions later.

Ramaswamy’s posture, though, was long-term and execution-heavy—something he’d internalized at Google. “Strategy without execution means nothing,” he said. And he brought the same push for ambition: “I routinely have squabbles with teams about whether something is ambitious or not. You gotta play the game of averages—if you try enough ambitious things, a bunch of them will work out.”

Over time, sentiment began to thaw. After Snowflake’s share price had slid starting in late 2021, the post-transition period looked different: the stock rose sharply late last year, revenue grew between October 2023 and October 2024, and bullish notes followed from firms like Jefferies, Goldman Sachs, and Deutsche Bank. One analyst even floated a $235 target.

Underneath the stock calls, the strategy was clear: make Snowflake the place where enterprise AI actually happens. Ramaswamy repeatedly came back to what might be the core challenge in practical AI—connecting messy, unstructured information to the clean, structured systems businesses run on. “One lens that all of you should have in your thinking about AI models is as a bridge between things like unstructured data and structured data,” he said. “That’s a fancy way of saying, AI is really good at figuring out from your spoken words what concepts, what numbers you’re looking for. It can also do that from documents. It’s these kinds of applications that end up creating the most value in enterprises.”

VIII. Business Model & Economics

Snowflake’s pricing model looks simple, but it rewired the incentives of the whole category. Instead of selling big, fixed licenses that customers pay for whether they use them or not, Snowflake charges like a utility: you pay for storage while data sits, and you pay for compute when you actually run queries. No giant upfront commitment. No buying capacity “just in case.” The bill follows the value.

That structure turned out to be more than customer-friendly—it became a growth engine. Snowflake’s trailing twelve-month revenue reached $3.84B, a stunning result for a company that was basically pre-revenue a decade earlier. And despite being consumption-based, Snowflake still produced gross margins around 75%, helped by relentless cloud-cost optimization and a multi-tenant architecture that lets improvements compound across the entire customer base.

The clearest proof of how sticky this gets isn’t the logo list, though Snowflake had 10,618 customers as of November 2024, including more than 800 members of the Forbes Global 2000. It’s what those customers do after they sign. Net revenue retention has consistently been over 130%, meaning the average customer spends meaningfully more each year. Even early on, this pattern was obvious: in the first half of 2020, customers who’d been on Snowflake for at least a year spent 58% more than they had the year before. That’s not just acquiring customers. That’s customers expanding from the inside.

Here’s how the flywheel works. A company might start with one workload—marketing analytics, for example. It goes well, the data stays centralized, performance is good, and governance is clean. Then other teams notice. Finance wants forecasting. Product wants behavioral analytics. Operations wants supply-chain visibility. Each new use case pulls in more data and generates more queries, and the Snowflake footprint spreads without the painful “new license negotiation” moment. Adoption expands because success expands.

Snowflake has also been unusually capital-efficient for a company that scaled this fast. It raised about $1.4 billion in total funding, yet reached a peak market cap around $70 billion. And it did it while sustaining explosive growth and strong unit economics—an outcome that tends to be rare in enterprise software, where companies often trade margin for momentum.

Underneath all of this are moats that reinforce each other.

The first is architectural. Separating compute from storage isn’t a cosmetic feature—it required rebuilding the system from the ground up. That’s why legacy vendors trying to “cloud-wash” older warehouses struggled to match Snowflake’s performance and cost profile.

The second is switching costs. Once Snowflake becomes the center of an enterprise’s data pipelines, analytics workflows, and internal applications, switching isn’t a weekend migration. It’s a risky, expensive overhaul: moving data, rebuilding integrations, retraining teams, and praying nothing mission-critical breaks.

The third is network effects. Snowflake’s data sharing and marketplace-style capabilities make the platform more valuable as more organizations participate. Customers can combine third-party data—weather, demographics, industry datasets—with their own internal data, without copying it all over the place. One customer captured the appeal succinctly: “We can now access weather data from one vendor, demographic data from another, and combine it with our sales data—all without moving a single byte.”

The fourth is economies of scale. Snowflake’s multi-tenant model means optimizations don’t stay isolated. When Snowflake squeezes better efficiency out of its infrastructure, everyone benefits. When it improves query performance, those gains show up across the fleet.

And finally, the model gives Snowflake unusually sharp instrumentation. Because revenue tracks usage, consumption becomes a real-time indicator of customer health. If usage drops, you don’t find out at renewal—you see it immediately. If it spikes, it’s a signal to lean in. That visibility doesn’t just help forecasting. It helps Snowflake run the business with urgency, precision, and a constant feedback loop between product value and commercial expansion.

IX. Playbook: Key Lessons & Strategies

Snowflake’s rise looks like a straight line in hindsight: great product, great timing, huge IPO. But the more interesting lessons are the ones underneath—the bets they made early, the constraints they embraced, and the uncomfortable decisions they didn’t flinch from.

The power of the founder-investor partnership: Snowflake is a case study in how venture capital can be more than funding. Sutter Hill Ventures owned more than 20% of Snowflake leading up to the IPO, and it earned that stake by operating, not just advising. Sutter Hill led Snowflake’s $5 million Series A in August 2012, and Mike Speiser didn’t just sit on the board—he served as founding CEO from 2012 to 2014. This wasn’t passive investment. It was active company construction during the most fragile years, when there was no product launch, no sales engine, and no external validation. The takeaway isn’t that investors should “run companies.” It’s that the founder-in-the-trenches role can be filled by someone who can recruit exceptional technical talent and provide operating leverage before a startup can afford it.

When to replace a successful CEO: The Muglia-to-Slootman transition is still one of the sharpest examples of a board acting on ambition rather than rescue. Under Muglia, Snowflake became one of the most highly valued private tech companies in the U.S.; Muglia himself noted, “Our post-money valuation is now $3.9bn making Snowflake amongst the top 25 most highly valued private US tech companies.” Yet the board made a call that’s rare when things are going well. Speiser put it plainly: “Snowflake is one of the most significant new companies in Silicon Valley and we believe Frank is the right leader at this juncture to fully realize that potential.” In other words, they weren’t optimizing for “excellent.” They were optimizing for “iconic.” The lesson is uncomfortable: sometimes a CEO can be doing everything right, and the board still decides the opportunity demands a different kind of leader.

Building for the cloud-native era: Snowflake’s founders didn’t hedge. They made a hard bet that the future of data infrastructure would be cloud-first and cloud-only—no on-premise fallback, no hybrid compromise. That matched Speiser’s broader philosophy: lean into transitions early, especially the ones incumbents can’t fully commit to without cannibalizing themselves. While competitors tried to bridge worlds, Snowflake optimized for one world. That focus let them build around cloud economics and elasticity from the start, instead of dragging legacy assumptions forward.

Multi-cloud neutrality as strategy: Snowflake’s multi-cloud posture wasn’t just a technical flex—it was a commercial wedge. Muglia said the push to add Azure came from customer demand, especially from retailers that compete with Amazon and were uneasy about building their data future on AWS. He gave the example of Nielsen: already using Snowflake on AWS, but wanting to use Snowflake on Azure for a new product. Running across AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud was expensive and operationally complex, but it removed a huge enterprise objection: lock-in. Snowflake positioned itself as the neutral layer companies could standardize on, regardless of which hyperscaler was underneath.

Consumption pricing as a growth accelerator: Snowflake’s consumption model didn’t just lower adoption friction—it changed the expansion mechanics. Customers could start small, prove value, and scale usage as new teams and workloads moved onto the platform. Revenue grew because customers grew, often without the classic enterprise software moment where expansion requires a brand-new negotiation. The model aligned incentives: if customers got more value, Snowflake earned more.

Platform vs. point solution: Snowflake kept widening what it meant to be “the data warehouse.” The Data Cloud vision stretched from analytics into data sharing, marketplace-style distribution, application development, and AI capabilities. Each layer increased the surface area of what customers could do without leaving Snowflake. The lesson here is about compounding: when you build a platform, each new capability can make the previous ones stickier and more valuable.

Managing hypergrowth: Snowflake didn’t just grow fast; it grew at a pace that forces internal reinvention. Revenue reached $264.7M in 2020, up from $96.7M in 2019. It went from roughly 80 early organizations to more than 10,000 customers in under a decade. That kind of scaling doesn’t happen by “adding headcount.” It requires rebuilding processes, systems, and culture repeatedly, always preparing for the next order of magnitude.

The playbook isn’t only defined by what Snowflake did. It’s also defined by what it refused to do. It didn’t dilute its cloud-only conviction to make early enterprise sales easier. It didn’t treat leadership continuity as sacred when the board believed the ceiling was much higher. It didn’t stay a single-product company once it had the credibility to become a platform.

Sometimes the biggest strategic advantage is a willingness to sacrifice comfort in exchange for focus.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Market Analysis

Bull Case: The Infinite TAM

The optimistic case for Snowflake starts with a simple belief: we’re still early in the data era. AI is pouring fuel on the fire, and Snowflake itself has argued its addressable market could grow dramatically by 2027 compared with last year. That’s why some analysts model years of outsized earnings growth ahead. If every company is becoming a data company, then Snowflake wants to be the neutral layer they all standardize on—the Switzerland of data infrastructure: trusted, cloud-agnostic, and hard to replace once it’s in the middle of everything.

AI is the clearest path to expanding the market. Ramaswamy has framed enterprise AI as a bridge between structured data—transactions, customer records, operational tables—and unstructured data like documents, audio, and video. “One lens that all of you should have in your thinking about AI models is as a bridge between things like unstructured data and structured data,” he said. And the implication is straightforward: if enterprises want AI that actually works, they need a place to store, process, and govern that messy reality. Snowflake’s pitch is that Cortex, plus the platform’s governance and security posture, makes it a safe default for deploying AI inside big companies.

Even with hyperscalers circling, Snowflake’s supporters argue its competitive position remains strong. Multi-cloud neutrality is still a powerful wedge, and the product’s reputation for performance and ease of use continues to win deals. The fact that net revenue retention has stayed above 130% is the punchline: customers aren’t merely renewing—they’re expanding.

Then there’s ecosystem compounding. The marketplace, data sharing, and native applications are all designed to make Snowflake more than a warehouse. As more third-party data products and apps live inside the platform, Snowflake becomes harder to unwind. Not because of a contract, but because the workflows, integrations, and distribution channels start to accumulate around it.

Finally, the cloud migration tailwind isn’t over. A large share of enterprise data still lives in on-prem systems. If the next leg of migration accelerates—pushed by AI, cost pressure, or modernization mandates—Snowflake is positioned to capture more of that flow.

Bear Case: The Hyperscaler Squeeze

The bearish case begins with a structural tension Snowflake can’t escape: its biggest competitors also own the infrastructure it depends on. Amazon, Microsoft, and Google don’t just have rival products—they control the cloud platforms Snowflake runs on. That’s the squeeze: you’re building a business on top of partners who have every incentive to commoditize your layer. Snowflake has also committed to spending $1.2 billion with Amazon over the next five years through a cloud infrastructure contract—real money, paid to a rival.

The consumption model can also cut the other way. In good times, usage expands naturally. In downturns, customers can tighten budgets by simply running fewer workloads—immediately. That makes revenue less predictable than classic subscription software, and it can turn macro uncertainty into a near-term business problem.

Valuation is another risk lever. Snowflake’s market cap was about $75 billion on the Wednesday before its after-hours plunge. As of 15-Aug-2025, the stock price was $199.08 and the market capitalization was $66.4B. Even after pullbacks, the stock has often been priced for excellence—implying sustained hypergrowth that becomes harder to deliver as the revenue base gets bigger.

Customer concentration adds a different kind of fragility. Big enterprises are great logos, but when one customer—like Capital One, which accounted for 11% of Snowflake’s revenue as of January—represents that much of the business, any change in usage patterns can show up quickly in results.

And then there’s AI competition. Snowflake is investing aggressively, but rivals like Databricks had a meaningful head start in machine learning and AI-native workloads. In the fastest-moving part of the stack, “catching up” is a risky strategy.

Market Analysis: The Reality

The real story is tension, not certainty. Snowflake has built a genuinely impressive platform with real strengths: deep entrenchment in enterprise data workflows, high switching costs, and expansion dynamics that prove customers keep finding more value over time. The CEO transition to Ramaswamy is also a clear signal that the company wants to lean into technical velocity and AI-first product direction, not just sales execution.

But the risks aren’t theoretical. The hyperscalers aren’t going away. The consumption model magnifies both upside and downside. And the market has consistently treated Snowflake as a premium asset—which means the company doesn’t get many “okay” quarters without consequences.

So the question isn’t whether Snowflake makes it. The question is whether it can keep earning its position as the independent, neutral data layer while scaling into a world where AI is rewriting what “data platform” even means. The outcome likely comes down to execution: shipping compelling AI products, expanding internationally, and protecting economics even while paying infrastructure costs to companies that would love to own the whole stack.

For investors, Snowflake is a high-conviction bet on the long arc of cloud data and enterprise AI. It’s also a bet that won’t be smooth. Volatility comes with the territory. But if you believe data keeps growing in importance—and AI is the next interface to that data—Snowflake remains one of the cleanest ways to ride both waves at once.

XI. Recent News

The latest updates out of Snowflake paint a clear picture of the Ramaswamy era: faster product cadence, heavier emphasis on AI, and a company trying to look more like a durable platform business than a momentum trade.

Snowflake said it will report second quarter fiscal 2026 results on August 27, 2025. In the most recently reported quarter referenced here (Q2 FY2025), Snowflake posted $868.8 million in revenue, up 29% year over year. Product revenue was $829.3 million, up 30%. Net revenue retention was 127% as of July 31, 2024, and the company said it now had 510 customers generating more than $1 million in trailing 12-month product revenue. The headline isn’t any single metric—it’s that the engine still runs: customers keep expanding, and the number of large deployments keeps climbing.

On the product side, the release notes tell you where Snowflake’s priorities are. Trust Center email notifications reached general availability on August 19, 2025. Write Once, Read Many (WORM) snapshots were in preview as of August 18, 2025. And Snowflake ML Jobs hit general availability on August 12, 2025. Taken together, it’s a familiar Snowflake pattern: enterprise controls and governance on one side, AI and machine learning tooling on the other, all moving forward in parallel.

Capital allocation has been getting more aggressive, too. In February 2023, Snowflake’s board authorized a stock repurchase program of up to $2.0 billion. As of July 31, 2024, $491.9 million remained available. Then in August 2024, the board authorized an additional $2.5 billion and extended the program’s expiration from March 2025 to March 2027. Whatever you think about buybacks for a growth company, Snowflake is clearly signaling confidence in the long-term story—even as the stock has seen real volatility.

The AI push is also becoming more concrete inside the platform. Snowflake said OpenAI’s GPT-5 is now available in Snowflake Cortex AI, and that it is bringing OpenAI’s latest open-source models to Cortex the same day they’re released. The message Snowflake wants customers to hear is simple: you shouldn’t have to leave the Data Cloud to access state-of-the-art models.

At the same time, Snowflake is leaning harder into international expansion and sovereign cloud initiatives, a theme that’s only grown louder as data sovereignty moves from “compliance checkbox” to board-level strategy. Ramaswamy framed it bluntly: “We’re headed into a fracturing world in terms of how different areas of the world are thinking about things like software and data and where it should sit.” Snowflake’s approach is partnership-driven, running on hyperscalers rather than trying to own the infrastructure itself. As he put it: “Many of the sovereign clouds are being built by the hyperscalers. We don’t own the data centers, we don’t own the software that are run on the machines that are in data centers, so we run on top of the hyperscalers.”

And the customer narratives Snowflake is highlighting are increasingly less about “faster analytics” and more about measurable business outcomes with AI in the loop. The company points to examples like Norway’s $1.8T sovereign wealth fund saving 213,000 hours each year with AI, Expand Energy pushing operational efficiency, Sallie Mae cutting regulatory processing times by 90%, and AstraZeneca using AI-powered chest X-rays to help detect lung disease. Whether you view these as case studies or marketing, they reinforce the same direction: Snowflake wants to be where enterprise data work happens—and where enterprise AI actually gets deployed.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music