Johnson & Johnson: The Healthcare Giant's Story

Introduction

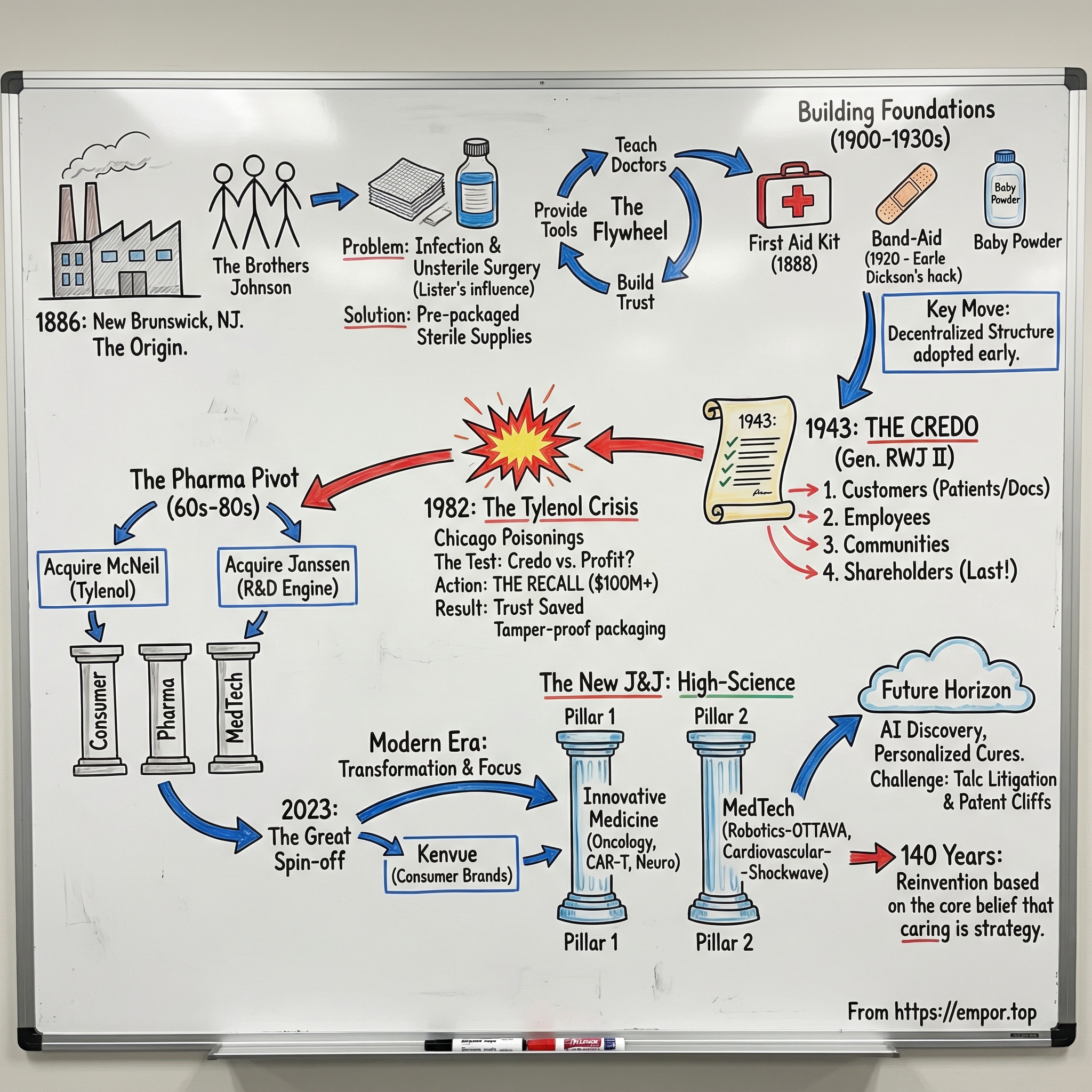

Walk the sterile corridors of a hospital almost anywhere on Earth and you’ll see it. Open a medicine cabinet from Mumbai to Minneapolis and it’s there too. Step into an operating room, where the tools quite literally hold human bodies together, and the same name keeps showing up: Johnson & Johnson.

Today, this institution out of New Brunswick, New Jersey sits among the most valuable companies in the world, with a market cap nearing $550 billion and about $94.2 billion in revenue in 2025. It’s also one of the most diversified businesses in healthcare. Over nearly a century and a half, it has lived through two world wars, the Great Depression, a poisoning crisis that would have ended most brands, and a pandemic that rewired global health systems.

So the question that makes this story worth telling is simple: how did three brothers, selling surgical dressings out of a converted factory in 1886, build an empire that—almost 140 years later—develops cancer immunotherapies, robotic surgery platforms, and treatments for diseases that didn’t even have names when the company began?

The answer isn’t a single breakthrough or a lone visionary moment. It’s a pattern: radical decentralization that lets many businesses run fast at once; a one-page corporate philosophy that leaders actually use to make hard calls; and an almost generational willingness to reinvent what Johnson & Johnson is.

A few themes will keep resurfacing. Innovation as survival. Crisis as the ultimate identity test. And the permanent tension between doing good and making money—plus the rare cases where a company figures out how to make those two forces reinforce each other instead of collide. Along the way, J&J becomes a masterclass in portfolio management: when to hold, when to buy, and, as the company later proved with the Kenvue spin-off, when to let go.

This is the story of a company that went from cotton and gauze to CAR-T cell therapy, from baby powder to bispecific antibodies—and, somehow, managed to keep its institutional soul intact through all of it.

Origins: Three Brothers and a Revolution (1886-1900)

The American Civil War killed more than 720,000 people. But the grim reality was that many of those deaths didn’t come from bullets. They came later—from infection, gangrene, and the everyday practices of medicine at the time: surgeons operating with unwashed hands, bandages reused until they were stiff with old blood. Germ theory was still new. Antisepsis wasn’t standard. In many places, it wasn’t even accepted.

A sixteen-year-old named Robert Wood Johnson saw enough of that suffering to have it mark him for life. He carried a simple, stubborn idea forward: there had to be a safer way to treat wounds.

Years later, Johnson encountered the work of Joseph Lister, the British surgeon who showed that disinfecting with carbolic acid could dramatically reduce infection during surgery. It was a breakthrough—scientifically persuasive, morally urgent, and, for most American doctors, hard to apply. Lister’s methods demanded discipline, preparation, and supplies that weren’t readily available. In the 1880s, many physicians still operated in street clothes. Even the most conscientious doctor couldn’t easily create sterility from scratch.

Robert Wood Johnson recognized the gap between what medicine now knew and what medicine could actually do. If hospitals and doctors couldn’t reliably produce sterile materials themselves, what if someone could manufacture them instead—ready to use, consistently prepared, and easy to order?

He took that idea to his brothers, James Wood Johnson and Edward Mead Johnson. In 1886, the three founded Johnson & Johnson in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

They set up shop in the old Janeway and Carpenter building on Neilson Street—hardly a grand headquarters, just an industrial space repurposed for a new kind of manufacturing. The company began with 14 employees: eight women and six men. For the era, that mix wasn’t typical, and it hinted at something that would show up again and again in J&J’s story: a practical willingness to do things differently if it made the operation stronger.

The products were the real disruption. Johnson & Johnson began manufacturing what became the world’s first commercially available sterile surgical supplies—sutures, absorbent cotton, gauze dressings. Before this, surgeons and hospitals often improvised, assembling materials on their own and hoping their process was “clean enough.” J&J offered something medicine was desperate for: standardization and sterility, packaged in a way that fit real-world practice.

And Johnson understood that products alone wouldn’t change behavior. Doctors needed a playbook. So the company did something that feels very modern: it taught the market. Johnson & Johnson published "Modern Methods of Antiseptic Wound Treatment," a detailed guide to Lister’s principles and how to apply them, using the company’s supplies. It spread widely among physicians—an educational mission, yes, and also a way to build trust and demand at the same time.

That was the early Johnson & Johnson flywheel. Teach antiseptic practice. Make it easier to adopt. Supply the tools that make it possible. As more doctors embraced the approach, more patients survived. And every better outcome reinforced the shift.

By the end of the 1890s, Johnson & Johnson had become the dominant American manufacturer of surgical supplies. More importantly, it had staked out a distinctive identity from day one: a business built right at the boundary between science and commerce, betting that better healthcare wasn’t just good ethics—it could be good strategy too.

Building the Foundation: Innovation and Expansion (1900-1930)

Johnson & Johnson’s first big leap into “everyday healthcare” didn’t start in a lab. It started out on the western edge of American railroad construction.

Back in 1888—just two years after the company was founded—a railroad surgeon wrote to Robert Wood Johnson with a blunt problem. His crews were laying track hundreds of miles from real medical care. Accidents were common. And when someone got hurt, there often wasn’t anything on hand to treat the wound.

Johnson’s response was practical and immediate: build a kit. He put together the first commercial first aid kit, stocked with antiseptic supplies and simple instructions. It was medicine packaged for the real world—portable, standardized, and designed for people who couldn’t wait for a doctor.

That little box captured a pattern that would show up again and again in J&J’s history. The company didn’t just invent things in isolation. It listened to the people doing the work—surgeons, nurses, workers, parents—then engineered products that closed the gap between what medical science knew and what daily life demanded.

In 1910, Robert Wood Johnson died, and his brother James took over as chairman. Under James’s leadership, the company accelerated. The founders had already built the hard stuff: manufacturing capability, trust with hospitals, and distribution channels. Now J&J could use that foundation as a platform—expanding product lines, deepening relationships, and scaling faster than a single-category company ever could.

Consumer products, interestingly, weren’t the original plan. In 1893, J&J introduced baby powder as a soothing companion to its medicated plasters. But customers kept writing in about the powder itself. The message was clear: this wasn’t just an add-on. It was a product people wanted on its own. J&J leaned in. Baby shampoo and other infant-care items followed, and a new kind of Johnson & Johnson began to take shape—one that didn’t just serve hospitals, but entered the home.

Then in 1920 came the kind of invention that feels obvious in hindsight and brilliant in the moment. Earle Dickson, a cotton buyer at the company, watched his wife Josephine repeatedly cut and burn herself in the kitchen. So he hacked together a solution: small squares of gauze fixed onto adhesive tape, ready to apply without help. When he shared the idea at work, people immediately saw what it could be. Johnson & Johnson launched Band-Aid, and it became one of the most recognizable healthcare products in history.

While all of that was happening at home, the company also started looking outward. In 1919, J&J established its first international affiliate in Canada. And in 1923, Robert W. Johnson’s sons—Robert Johnson and J. Seward Johnson—took an around-the-world trip that changed how they saw the business. They came back convinced that Johnson & Johnson couldn’t stay an American company. The need for sterile supplies wasn’t local; it was global. And J&J had learned how to manufacture trust at scale.

Inside the company, another foundational decision was quietly taking shape—one that would later become a defining competitive advantage. Instead of pulling everything into a single centralized machine, Johnson & Johnson began operating through semi-autonomous divisions, each focused on a specific product line or market. In an era when most big companies were consolidating power at the center, the Johnsons were making the opposite bet: that smaller teams, closer to customers, would move faster and make better calls than distant corporate headquarters.

It was an unusual choice. And it would turn out to be a prophetic one.

The General Takes Command: Robert Wood Johnson II Era (1930s-1960s)

Robert Wood Johnson II—son of the founder—didn’t walk into Johnson & Johnson through a side door. As a teenager, he started as a mill hand and learned the business where the noise and heat were: on the factory floor. He moved up through the company with an operator’s intensity and a leader’s instinct for what a company should stand for. During World War II, he coordinated wartime manufacturing and earned the rank of brigadier general. The title followed him home, and so did the nickname: “the General.”

He took command during the Great Depression, and the choices he made in that moment revealed the kind of institution he wanted J&J to be. While plenty of companies cut wages and shed workers, Johnson leaned into employee welfare. He argued that security and respect weren’t feel-good perks; they were fuel for productivity and loyalty. In his mind, this wasn’t charity. It was how you built a durable enterprise.

That thinking became explicit in 1943, when he wrote a single-page document he called “Our Credo.” It laid out Johnson & Johnson’s responsibilities in a specific order. First: customers—doctors, nurses, patients, and parents. Second: employees. Third: the communities where the company operated. And only then, fourth: shareholders, who would earn “a fair return” if the first three obligations were met.

For the 1940s, that ordering was a jolt. Most American companies would have put shareholders at the top without a second thought. Johnson insisted the sequence worked the other way around: serve customers, treat employees well, invest in communities, and the profits would come as a consequence. The Credo wasn’t just a moral statement. It was a management tool—a way to make hard decisions consistently. And it would be stress-tested under extreme pressure decades later, when Tylenol faced the crisis that could have ended the brand.

In 1944, Johnson & Johnson went public on the New York Stock Exchange. The listing opened the door to deeper pools of capital, but the General was determined that the company wouldn’t become a slave to short-term expectations. He pushed a long view—building long-term value by behaving like a company that planned to be around for generations.

The war years and their aftermath also expanded what J&J could do. Supplying surgical products to the military forced the company to sharpen its mass manufacturing and logistics at a scale few could match. When peace returned, those capabilities translated into a commercial edge. And with the postwar baby boom came a wave of demand for J&J’s consumer products—especially baby care—which increasingly became part of the everyday language of American parenthood.

But the General’s most enduring move wasn’t a product. It was an operating system.

He formalized the decentralized “family of companies” model. Instead of folding everything into a single corporate machine, Johnson let subsidiaries run with real autonomy: their own presidents, cultures, and profit-and-loss responsibility. Headquarters supplied capital, direction, and the Credo. The rest stayed close to the ground, where decisions could be made faster and with better information. The structure drew entrepreneurial managers—people who wanted the resources of a large company without the suffocation of a large bureaucracy. Over time, it became one of Johnson & Johnson’s quiet superpowers.

And even as he strengthened the base—surgical supplies and consumer staples—he was also looking ahead. He could see where healthcare was going. The pharmaceutical industry was entering a new era, and J&J couldn’t afford to watch from the sidelines. The purchases that would redefine the company were approaching fast.

The Pharmaceutical Pivot: Becoming a Drug Giant (1960s-1980s)

In 1959, Johnson & Johnson made an acquisition that quietly changed what the company was capable of becoming. It bought McNeil Laboratories, a small pharmaceutical firm in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania. McNeil’s most important product was a pain reliever called acetaminophen, sold under the brand name Tylenol. Within a year, J&J received approval to sell Tylenol without a prescription—taking it from a doctor-mediated pharmaceutical into something that could sit on a shelf in every American pharmacy.

Tylenol would go on to become one of the best-selling drugs in American history—and later, the center of an existential moment for the company. But at the time, the point wasn’t just the revenue. The point was intent. Johnson & Johnson was no longer satisfied being known for surgical dressings and baby products. It wanted a serious seat at the table in pharmaceuticals.

That ambition became impossible to miss in 1961, when J&J acquired Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Janssen had been founded in 1953 by Belgian scientist Paul Janssen, and it wasn’t simply a drug company—it was a drug discovery machine. Janssen was one of the most prolific pharmaceutical scientists of the twentieth century, personally inventing or co-inventing more than eighty drugs over his career. Among them was fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that transformed surgical anesthesia long before it became associated with a far darker chapter decades later.

The genius of the Janssen deal wasn’t just the purchase. It was how Johnson & Johnson handled what came next. Or more accurately: what it chose not to do. Instead of folding Janssen into a centralized corporate structure, J&J let Paul Janssen keep running his lab with near-total scientific freedom. It was the decentralized model, now applied to R&D: put extraordinary talent in the best possible environment, give it resources, and keep bureaucracy out of the way. Janssen kept producing important compounds, and J&J gained a world-class discovery engine without breaking the culture that made it work.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, this all hardened into what became J&J’s three-pillar strategy: Consumer Products, Pharmaceuticals, and Medical Devices. Each pillar was made up of its own network of semi-autonomous businesses, but together they gave Johnson & Johnson reach across the healthcare system. A person might trust a J&J product at home, encounter a J&J drug in a hospital, and be treated with a J&J device in surgery. Few companies could claim that kind of end-to-end presence.

Pharma kept expanding through both acquisitions and internal investment. Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation, a J&J subsidiary, became a major force in women’s health, especially oral contraceptives. J&J also poured money into research infrastructure—labs, clinical development capabilities, and the long, expensive machinery required to turn science into approved medicine.

Medical devices grew in parallel. Ethicon was already a leader in sutures, and J&J broadened into other surgical products, diagnostics, and orthopedic devices. And the company kept running the same playbook: buy strong businesses with strong leaders, don’t smother them inside a central headquarters, and use J&J’s capital and distribution to help them scale.

By the early 1980s, the transformation was complete. Johnson & Johnson had become a diversified healthcare conglomerate, operating through more than 150 subsidiaries worldwide. The three pillars offered resilience—if one part of healthcare slowed, another could carry the load. And the decentralized structure meant decisions could be made close to the customer, fast.

Then came the kind of event no strategy memo can plan for. In the fall of 1982, people in Chicago began dying after taking Tylenol capsules—and Johnson & Johnson’s response would become the defining case study in corporate crisis management for a generation.

The Tylenol Crisis: Masterclass in Crisis Management (1982)

On the morning of September 29, 1982, twelve-year-old Mary Kellerman in Elk Grove Village, Illinois woke up with cold symptoms. Her parents gave her an Extra-Strength Tylenol capsule. By seven o’clock, she was dead.

That same day, Adam Janus, a postal worker in nearby Arlington Heights, took Tylenol and collapsed. He died soon after. Then, in a tragic ripple effect, his brother Stanley and sister-in-law Theresa took capsules from the same bottle. They died too. In all, seven people across the Chicago area died after taking Extra-Strength Tylenol capsules that had been laced with potassium cyanide.

The poisonings—still unsolved—set off a nationwide panic. Tylenol wasn’t some fringe brand. It controlled more than a third of the over-the-counter pain reliever market at the time and generated roughly $500 million in annual revenue. Millions of bottles were sitting on store shelves and in medicine cabinets across the country. And the terrifying part wasn’t just what had happened. It was what no one could yet answer: how many bottles were compromised, and whether Chicago was the start or just the first place anyone noticed.

At headquarters in New Brunswick, New Jersey, the crisis landed on the desk of Chairman James Burke. The debate inside the company was immediate and intense. Some executives and outside advisers argued the evidence pointed to a localized tampering event in Chicago. A nationwide recall would be catastrophic: hundreds of millions in losses, a brand that might never come back, and a public signal that could invite copycats. The “rational” move, they argued, was to work with law enforcement, pull product regionally, and wait for clarity.

Burke and his team reached for the Credo.

The one-page document Robert Wood Johnson II had written nearly forty years earlier wasn’t treated like a slogan or a piece of corporate decor. Burke saw it as an operating manual for moments exactly like this. And the Credo’s ordering was unambiguous: the first responsibility was to customers—doctors, nurses, patients, parents. If that statement meant anything at all, it meant consumer safety came before the income statement.

So Johnson & Johnson made the call that felt almost unthinkable at the time. It pulled about 31 million bottles of Tylenol from store shelves nationwide. The recall cost more than $100 million—a staggering hit in 1982. The company set up a toll-free hotline, offered free replacement products, and cooperated fully and publicly with the FBI and FDA investigation. Burke went on national television, including 60 Minutes and The Phil Donahue Show, and explained what the company was doing and why.

The coverage was intense, but it wasn’t the feeding frenzy many expected. It was largely admiring. The Washington Post wrote that “Johnson & Johnson has effectively demonstrated how a major business ought to handle a disaster.” Plenty of marketing and public relations experts had predicted Tylenol was finished. Instead, they watched the company behave less like a defendant and more like another victim—one with the power and willingness to take action.

But the recall was only act one. Act two was the relaunch, and it mattered just as much.

Johnson & Johnson introduced triple-sealed, tamper-resistant packaging—an innovation that quickly became the new baseline for the entire over-the-counter drug industry. It backed that change with aggressive efforts to win trust back: discounts, heavy advertising, and a clear message that the product was now designed to make this kind of crime dramatically harder to pull off.

And it worked. Within months, Tylenol began to recover. Within a year, it had regained essentially all the market share it had lost.

The Tylenol crisis became one of the most studied corporate responses in modern business history—not because the company had brilliant PR tactics, but because it had something far rarer: a decision framework that existed before the emergency. Companies that try to discover their values mid-crisis are improvising while the building burns. Johnson & Johnson had the Credo long before anyone could imagine cyanide in a painkiller, and in the most important moment imaginable, it functioned like a compass.

There was a deeper lesson too, especially for investors. Corporate culture often gets dismissed as soft, vague, and unmeasurable. In 1982, Johnson & Johnson showed it could be worth nine figures, in cash, on demand. The recall cost $100 million. The brand it protected was worth many times that. In the clearest possible way, culture wasn’t a cost center.

It was an asset.

Global Expansion and Portfolio Building (1980s-2000s)

Coming out of the Tylenol crisis, Johnson & Johnson did something rare: it didn’t just survive. Its credibility actually went up. And with that trust came something even more useful—permission to keep expanding.

The late 1980s and 1990s became an era of confident, well-funded building. J&J went on what looks, in hindsight, like a remarkably disciplined acquisition campaign: not random shopping, but a decades-long effort to lock in leadership positions across all three pillars of the business.

On the consumer side, the company assembled a portfolio of brands that already had what money can’t easily buy: trust. Neutrogena, acquired in 1994, brought a premium skincare franchise with strong dermatologist credibility. Aveeno followed, with its oatmeal-based products and “gentle, natural” positioning that resonated with families. Then, when Pfizer decided to divest its consumer health business in 2006, J&J picked up major brands including Listerine—suddenly giving the company a flagship in oral care. The playbook stayed consistent: acquire products people already believed in, then use J&J’s global distribution and marketing muscle to scale them.

Medical devices went through a similar consolidation—except here, the stakes were even higher because surgeons don’t switch lightly. Buying DePuy in 1998 made Johnson & Johnson a serious force in orthopedics, from hip and knee replacements to spine products. Over time, the company kept deepening that position. Ethicon, its surgical instruments business, expanded into advanced energy devices and minimally invasive surgery—exactly where operating rooms were heading.

And while this story is about the 1980s through the 2000s, one later deal shows what the strategy was ultimately building toward: the acquisition of Synthes in 2012 for $21.3 billion. Synthes brought a major trauma and surgical fixation portfolio that complemented DePuy’s joint replacement strength. Together, they cemented J&J’s dominance in orthopedics.

But the biggest long-term shift was happening in pharmaceuticals.

Janssen—still benefiting from the discovery culture Paul Janssen had created—became a source of true blockbuster medicines. Remicade, an anti-TNF biologic for autoimmune diseases, grew into one of the best-selling drugs in the world. Stelara followed, targeting interleukin pathways for psoriasis and other inflammatory conditions. These weren’t minor reformulations. They represented new ways of treating entire categories of disease—and they changed Johnson & Johnson’s financial profile in the process.

Geographically, the company pushed hard outside the U.S. and Western Europe. J&J expanded into emerging markets, building manufacturing and sales capabilities across China, India, Brazil, and Southeast Asia. The logic was simple: as middle classes grew, healthcare spending would rise. J&J wanted to already be there—embedded in the system—before that wave arrived.

Still, the ride wasn’t perfectly smooth. Like every major drugmaker, J&J periodically hit patent cliffs, when exclusivity expired and generic competition rushed in. And in the late 2000s, the company took reputation damage from FDA warning letters and product recalls—especially in consumer and over-the-counter products. The most visible pain was at McNeil Consumer Healthcare in 2009 and 2010, when manufacturing quality problems triggered a series of recalls. For a company that had built its name on reliability, it was a jarring public stumble—and it forced major investment to fix operations.

But zoom out, and the arc is clear. By the end of the 2000s, Johnson & Johnson had grown into a truly global healthcare institution, generating more than $60 billion in annual revenue and holding top-tier positions in pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and consumer health. The three-pillar strategy delivered resilience: when one segment took a hit, the others often helped absorb it. And the decentralized model—messy at times, criticized as inefficient—kept pulling in entrepreneurial leaders who could run businesses with real autonomy, but with J&J’s capital and credibility behind them.

That success created a new debate. As Wall Street fell in love with focus, pure-play pharma companies like Pfizer and Roche often commanded higher earnings multiples, and specialist medical device companies drew investors who wanted simpler stories. So analysts started asking the uncomfortable question: was Johnson & Johnson’s diversification still a superpower—or had it become a conglomerate structure that hid value?

It would take another decade for the company to answer that question in a definitive way.

Modern Era: Transformation and Focus (2010s-Present)

The decade that started in 2010 tested Johnson & Johnson in ways that felt almost stacked. Manufacturing recalls. Patent expirations. An opioid crisis that pulled much of pharma into the public square. A once-in-a-century pandemic. And then, hanging over everything, mounting litigation tied to legacy products. For many companies, that kind of overlap becomes a defensive crouch. For J&J, it became the runway for the biggest strategic reshaping since its pharmaceutical pivot in the 1960s.

The shift began with a hard, quiet truth: the consumer health business—the baby powder, Band-Aids, and the household brands that had defined J&J’s public identity for more than a century—was no longer the main engine of value creation. Pharmaceuticals and medical devices carried higher margins, demanded deeper R&D, and offered more durable competitive positions. Consumer health was still a strong business. It just wasn’t the growth business. And it played by a different set of capital and innovation rules than the rest of the company.

In 2023, J&J made the break. Kenvue, the newly named consumer health company, went public in May 2023 in the largest U.S. IPO since 2021, raising $3.8 billion. J&J completed its full exit by May 2024 through a final debt-for-equity exchange. The brands that had defined Johnson & Johnson for generations—Tylenol, Band-Aid, Neutrogena, Listerine, baby products—moved to Kenvue. In a remarkable coda, Kimberly-Clark agreed to acquire Kenvue for approximately $40 billion in November 2025, validating both the quality of those franchises and J&J’s timing in spinning them off while they still commanded premium value.

What remained was a more focused healthcare company with two segments: Innovative Medicine (the renamed pharmaceutical division) and MedTech (the devices business). Even the new naming wasn’t cosmetic. It was a signal of identity. The company was no longer trying to be the most familiar name in your bathroom cabinet. It was trying to be the best at complex science, clinical execution, and regulated innovation.

The COVID-19 pandemic became an unexpected proving ground for that identity. J&J developed a single-dose adenoviral vector vaccine, which received Emergency Use Authorization in February 2021. The single-dose design made it especially valuable for hard-to-reach populations and many developing countries. In total, J&J delivered hundreds of millions of doses globally before the vaccine’s EUA was revoked in June 2023 as demand shifted almost entirely to mRNA boosters. Commercially, it was never the kind of windfall the mRNA vaccines became. Operationally, it showed J&J could still mobilize science, manufacturing, and distribution at global scale under extreme time pressure.

As the pandemic faded, the company’s acquisition strategy in the 2020s sharpened—more aggressive, more focused, and clearly aimed at future therapeutic leadership. In 2024 alone, J&J completed the $13.1 billion acquisition of Shockwave Medical, bringing catheter-based cardiovascular intervention technology into MedTech. It acquired Ambrx Biopharma for $2 billion, gaining antibody-drug conjugate technology for oncology. Proteologix joined for $850 million to add bispecific antibody capabilities, and V-Wave for $600 million upfront to push deeper into heart failure treatment.

The pace accelerated again in 2025. In January, J&J announced the $14.6 billion acquisition of Intra-Cellular Therapies, adding lumateperone (CAPLYTA) and a neuroscience pipeline that expanded J&J’s position in schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder. In December 2025, it completed the $3.05 billion acquisition of Halda Therapeutics, gaining a novel platform aimed at oral targeted therapies for prostate cancer. Across 2024 and 2025, J&J deployed more than $30 billion on M&A—capital deliberately concentrated around oncology, immunology, neuroscience, and cardiovascular disease.

The bet wasn’t just on dealmaking. It was on output. In 2025, J&J received FDA approval for INLEXZO, the first drug-releasing system for bladder cancer treatment. IMAAVY (nipocalimab) was approved for generalized myasthenia gravis. AKEEGA became the first precision therapy for BRCA2-mutated prostate cancer, showing a 54% reduction in disease progression. RYBREVANT FASPRO received approval as the first subcutaneous therapy for EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. And the oncology franchise kept compounding: DARZALEX exceeded $3 billion in quarterly sales, while CARVYKTI—J&J’s CAR-T therapy for multiple myeloma—reached $334 million in a single quarter and continued to grow.

The financial results reflected the momentum. In 2025, J&J posted $94.2 billion in revenue, up 6% year over year, with adjusted earnings per share of $10.79. The company guided to approximately $100 billion in sales for 2026—a milestone that would have sounded absurd back in that converted factory on Neilson Street.

But the modern era hasn’t been a clean victory lap. The largest overhang remains talc litigation. Tens of thousands of plaintiffs allege that J&J’s baby powder—once one of the company’s most iconic products—contained asbestos and caused ovarian cancer. J&J has vigorously denied the claims, pointing to decades of testing that it says showed the product was safe. The company attempted to resolve the litigation through a subsidiary bankruptcy strategy, with proposed settlement amounts that increased from $6.48 billion to $9 billion. In April 2025, a federal judge rejected the third bankruptcy attempt, and J&J said it would not appeal. As of January 2026, approximately 67,580 lawsuits remained pending. Separately, the company reached a $700 million tentative settlement with more than 40 U.S. states over marketing practices. The uncertainty is real—even if J&J’s balance sheet is built to absorb outcomes that would cripple smaller companies.

Since CEO Joaquin Duato took the role in January 2022, and then became chairman the following year, the strategy has been consistent: concentrate on high-innovation, high-margin healthcare businesses where deep science and regulatory expertise create durable competitive advantage. The consumer health separation, the acquisition surge, and the pipeline investment all flow from that thesis. The open question now is the only one that ever matters at this scale: can execution keep pace with ambition?

Playbook: Business and Management Lessons

Nearly 140 years of history is enough time to try almost every management idea—and to learn, the hard way, which ones actually hold up when the stakes are real. With Johnson & Johnson, the lessons aren’t abstract. They show up in how the company is built, how it buys, how it responds under pressure, and how it keeps thousands of leaders moving in roughly the same direction.

The Credo as Operating System. Most corporate values statements are wall art. J&J’s Credo has behaved more like code. Its power comes from being specific: it doesn’t just say “do the right thing,” it ranks responsibilities—customers first, shareholders last. That sounds soft until you watch it become decisive. In the Tylenol crisis, the Credo didn’t just offer moral reassurance; it removed the need to argue about first principles while the company was in free fall. The organization already knew what it was supposed to optimize for. The broader lesson is that values-based management isn’t anti-shareholder. When it’s real, it’s a form of risk management that can protect the asset that matters most: trust.

The Decentralization Paradox. It’s one thing to talk about empowerment. It’s another to run an enterprise made up of more than 250 operating companies and still feel like one Johnson & Johnson. The model gives subsidiary leaders real authority over strategy, hiring, and day-to-day resource decisions. The center holds the levers that keep the system coherent: capital allocation, M&A strategy, and the Credo. The tension is the point, and it never fully goes away. The upside is speed and accountability—leaders close to customers can act fast, and when a unit wins or loses, ownership is clear. The downside is duplication, occasional fragmentation, and the constant risk that a unit optimizes for itself at the expense of the whole. Making decentralization work isn’t a one-time design choice; it’s an ongoing calibration problem.

Crisis as Defining Moment. Tylenol became the template because it was more than good messaging. It was a commitment to actions that were painful up front: move quickly, put safety ahead of cost, communicate plainly, and then spend what it takes to rebuild confidence. The companies that try to thread the needle with half-measures often learn the same lesson too late: you can’t negotiate with a public loss of trust. J&J showed that taking the financial hit early to protect long-term credibility isn’t just the ethical move—it’s often the economically rational one.

Buy, Build, or Both. Johnson & Johnson never treated R&D as a pure “invent everything ourselves” game, or a pure “buy innovation” game. It did both. It kept meaningful internal research horsepower—spending roughly $15 billion a year on R&D—while using acquisitions to add platforms, capabilities, and scientific talent that would take too long to build organically. The Janssen deal in 1961 and the Intra-Cellular Therapies deal in 2025 are the same logic applied across sixty years: acquire exceptional science, don’t crush it under bureaucracy, and use J&J’s scale to expand what it can become.

Stakeholder Complexity as Moat. Healthcare is brutal not just because it’s regulated, but because it’s multi-player. J&J has to work across patients, physicians, hospital systems, insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, and regulators—often all at once, and across dozens of countries. That complexity is expensive, slow, and often frustrating. It’s also a barrier that protects incumbents. A new entrant isn’t just building a product; it’s trying to build relationships, regulatory competence, and distribution infrastructure that take decades to earn. At J&J’s scale, navigating that maze isn’t just overhead. It’s part of the competitive advantage.

Power Analysis and Competitive Position

Look at Johnson & Johnson through a competitive-strategy lens and you see something more interesting than “a big healthcare company.” You see a set of advantages that stack on top of each other—capital, regulation, trust, and deep integration into how medicine actually gets practiced.

Scale Economies. J&J spends roughly $15 billion a year on R&D, putting it in the top tier globally. That matters because drug development is not just expensive—it’s probabilistic. If the average new therapy can cost on the order of $1–2 billion to take from discovery to market, then the biggest edge isn’t predicting the one winner. It’s being able to run many shots on goal at once. J&J can fund dozens of clinical programs simultaneously and survive the failures because the portfolio throws off enough cash to keep reinvesting. Smaller competitors often have to make a few concentrated bets and hope they land. In MedTech, scale shows up differently: purchasing leverage, manufacturing efficiency, and the capacity to place long-term platform bets—like the OTTAVA robotic surgical system—without risking the entire business.

Switching Costs. In many of J&J’s most important categories, “competition” is real, but switching is slow. If a patient is stable on DARZALEX or STELARA, there’s rarely an incentive to change therapies without a clear clinical reason. On the device side, switching can be even stickier: surgeons train on specific systems, hospitals standardize protocols, and procurement contracts add institutional friction. None of this blocks challengers forever—but it buys time, and time in healthcare often translates into durable revenue.

Regulatory Moats. Every product J&J sells—drug or device—has already climbed the hardest hill: years of trials, evidence generation, and regulatory review. That process acts like a toll road for new entrants. Generics must prove bioequivalence for small-molecule drugs. Biosimilars face their own costly clinical burdens to compete with biologics. And layered on top is intellectual property: patents and regulatory exclusivities that, together with sophisticated life-cycle management, can extend the commercial runway of key franchises.

Brand and Reputation. In healthcare, brand isn’t about clever advertising. It’s about what people trust when the consequences are real. When a surgeon evaluates an orthopedic implant, or a hospital system signs a supply contract, J&J’s name carries earned credibility—built over decades of product performance and clinical evidence. That reputation doesn’t win on its own, but it can tip close decisions and reduce the friction of adoption.

Competitive Landscape. One reason J&J is hard to neatly categorize is that it faces different rivals depending on the room it’s walking into. In pharma, competitors include Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, AbbVie, and Merck. In medical devices, it’s Medtronic, Abbott, Stryker, and Boston Scientific. Very few companies compete with J&J across both arenas at scale. That breadth becomes a subtle structural advantage in relationships with hospitals and health systems: J&J can show up with a wider set of solutions than a pure-play competitor can.

Against all of this, the most telling way to track whether J&J is winning isn’t a single quarter’s earnings beat. It’s whether the innovation machine is replenishing itself. Two metrics capture that best: Innovative Medicine operational sales growth (which strips out currency noise to show core momentum), and new product contribution (how much revenue is coming from products launched in the last five years). Together, they answer the question that never goes away in healthcare: is the next generation arriving fast enough to replace what time and competition inevitably erode?

Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

The first and most obvious risk is the patent cliff. Stelara, which at its peak brought in more than $10 billion a year, is now facing biosimilar competition. Johnson & Johnson has navigated big transitions before, but this one is different in a simple way: when a product that large starts to fade, replacing it isn’t about finding “a” new hit. It’s about stacking multiple meaningful wins, fast. If the pipeline or recent acquisitions don’t fill the gap on the right timeline, Innovative Medicine could hit a stretch of flat or declining revenue.

At the same time, pricing pressure is rising almost everywhere. In the U.S., the Inflation Reduction Act introduced Medicare drug price negotiation, and additional policy changes could expand government leverage over pricing. In Europe and Asia, reference pricing and health technology assessments continue to push prices down. MedTech isn’t immune either: hospital budgets are tight, and group purchasing organizations can squeeze device pricing. J&J can defend premium pricing when it keeps delivering clear clinical advantages—but innovation is uncertain by nature, and competitors are well-funded and relentless.

Then there’s litigation, and it’s not a footnote. With roughly 68,000 talc lawsuits pending and the bankruptcy settlement approach rejected, the company is now looking at a longer, more granular legal process—one case, one jurisdiction, one verdict at a time. J&J can likely absorb large dollar outcomes financially. The harder costs are reputational drag and management attention: what doesn’t show up neatly on an income statement, but can still tax an organization.

Zooming out, the industry structure is getting tougher too. Buyer power keeps rising as healthcare systems consolidate and governments get more assertive on pricing. Substitutes are spreading as generics and biosimilars compress exclusivity periods. And rivalry in the most attractive therapeutic areas remains intense, with deep-pocketed peers chasing the same categories J&J is targeting.

The Bull Case

The bull case starts with what J&J is trying to replace Stelara with: not hope, but a pipeline and portfolio that’s been producing real approvals in the 2020s. DARZALEX continues to grow. CARVYKTI is ramping in CAR-T. And deals like Intra-Cellular Therapies and Halda Therapeutics add both near-term products and longer-dated shots on goal. Management has guided to roughly $100 billion in revenue in 2026, which implies that even with legacy pressure, the machine is still expected to move forward.

On durable advantage, J&J checks a lot of boxes. Under Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, scale economies show up most clearly in R&D, manufacturing, and commercialization—places where spending and experience compound. The Kenvue spin-off is also a kind of counter-positioning: by exiting consumer health, J&J made itself a more focused innovation company while other large incumbents have been less willing to part with non-core assets. And process power may be the most underappreciated strength of all—decades of clinical development execution, regulatory navigation, and global launch capability that competitors can’t copy quickly, even with money.

Financially, the foundation is unusually strong. J&J is one of only two U.S. corporations with a AAA credit rating from Standard & Poor’s, alongside Microsoft. That’s not just a badge; it’s strategic freedom—cheap capital when opportunities show up, and flexibility when markets seize up. Add in 64 consecutive years of dividend increases, and you have a picture of a company that has historically thrown off durable cash through multiple cycles.

MedTech is another reason bulls stay bullish. If OTTAVA clears review and launches successfully, it could give J&J a real shot at a market that Intuitive Surgical has dominated for years. The Shockwave acquisition places the company in faster-growing cardiovascular interventions. And the broader backdrop is favorable: aging populations create steady, long-duration demand for procedures and devices.

The final argument is structural. Post-Kenvue, Johnson & Johnson is simpler and more focused than it has been in decades. Investors aren’t being asked to underwrite a mixed bag of consumer brands alongside pharma and devices. What remains—Innovative Medicine and MedTech—shares science, regulatory competence, and overlapping healthcare customers. The case that the whole is worth more than the parts is now easier to tell, and easier to believe.

Epilogue and Future Outlook

Healthcare is hitting another inflection point. Artificial intelligence is changing how drugs get discovered, letting researchers screen enormous numbers of molecules in silico before anyone mixes chemicals in a lab. Digital health tools are turning everyday life into data—streams of measurements, symptoms, and outcomes that can reshape how diseases get understood and treated. Personalized medicine, built around genetic profiles, is moving from theory into practice. And gene and cell therapies are pushing medicine toward something it has almost never been: curative.

Johnson & Johnson is trying to plant flags across that whole frontier. By acquiring the technology behind CARVYKTI, it bought a real position in CAR-T—one of the most consequential shifts in cancer treatment in decades. OTTAVA is a bet that the operating room keeps moving toward software, data, and precision robotics. And its push into antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, and targeted protein degradation—much of it accelerated through recent acquisitions—is a signal that J&J intends to stay on the sharp edge of modern pharma, not just defend legacy franchises.

The question for the next decade is the same one J&J has faced at every major turn: can it reinvent itself again, at the pace the world now demands? It has made these leaps before—from surgical supplies to consumer products, from consumer products to pharma, and now from sprawling conglomerate to a more focused innovation company. Each shift required new muscles and new leaders. But the thread that ties them together is the same one-page idea Robert Wood Johnson II put into writing: that if you make decisions in the long-term interest of patients and customers, the long-term value tends to follow.

The three brothers who opened that factory in New Brunswick in 1886 couldn’t have imagined CAR-T cells or robotic surgery. But they would recognize the core belief underneath all of it: that improving human health can be both a moral obligation and a durable business strategy. Nearly 140 years later, in a world of quarterly pressure and constant disruption, Johnson & Johnson is still making the same bet it made at the beginning—that if you want to build a company that lasts, you have to build one that cares.

Recent News

Full-Year 2025 Results and 2026 Guidance. Johnson & Johnson closed 2025 with $94.2 billion in revenue, up 6% from 2024, and adjusted earnings per share of $10.79. Management guided to roughly $100 billion in sales for 2026—a symbolic threshold that also signals continued momentum across both Innovative Medicine and MedTech.

Major Acquisitions. The M&A push stayed aggressive and targeted. In January 2025, J&J completed its $14.6 billion acquisition of Intra-Cellular Therapies, bringing in CAPLYTA and a broader neuroscience pipeline. In December 2025, it closed the $3.05 billion acquisition of Halda Therapeutics, aimed at next-generation oral therapies for prostate cancer.

FDA Approvals. The pipeline translated into approvals in 2025. The FDA cleared INLEXZO for bladder cancer, IMAAVY for generalized myasthenia gravis, AKEEGA for BRCA2-mutated prostate cancer, and RYBREVANT FASPRO for EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. CAPLYTA also picked up approval as an adjunctive therapy for major depressive disorder.

Talc Litigation. The legal overhang remained unresolved. In April 2025, a federal judge rejected J&J’s third attempt to resolve talc claims through a subsidiary bankruptcy. The company said it would not appeal. Roughly 67,580 lawsuits remained pending in New Jersey multidistrict litigation. Separately, J&J reached a $700 million settlement with more than 40 U.S. states over marketing practices.

Kenvue Developments. The consumer-health chapter kept moving forward without J&J. In November 2025, Kimberly-Clark agreed to acquire Kenvue—J&J’s former consumer health subsidiary—for approximately $40 billion. The deal was expected to close in mid-2026.

Pipeline and Clinical Data. At ASH 2025, J&J presented landmark data for TECVAYLI plus DARZALEX FASPRO in second-line relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Nipocalimab received FDA Fast Track designation for Sjogren’s disease. And in MedTech, the OTTAVA robotic surgical system was submitted for regulatory review.

Shareholder Returns. J&J raised its dividend for the 64th consecutive year, with the annualized payout at $5.20 per share. The stock hit all-time highs in January 2026, trading near $227 and putting the company’s market capitalization close to $550 billion.

Links and References

- Johnson & Johnson Annual Reports and SEC Filings (investor.jnj.com)

- "Our Credo" — Johnson & Johnson’s corporate values document (jnj.com/credo)

- "The Tylenol Crisis, 1982" — case studies on the poisonings, the recall, and the rise of tamper-resistant packaging

- Lawrence G. Foster, "Robert Wood Johnson: The Gentleman Rebel" — biography of J&J’s transformative leader

- Johnson & Johnson Heritage Archives — company history and archival materials

- Kenvue Inc. SEC Filings — documents related to the separation transaction

- FDA approval letters for DARZALEX, CARVYKTI, IMAAVY, INLEXZO, and AKEEGA

- Scott Bartz, "Killer Business: Meditations on the Tylenol Murders"

- Acquired.fm podcast archives — related episodes on healthcare and the pharmaceutical industry

- Johnson & Johnson Pipeline updates and R&D Day presentations (investor.jnj.com)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music