Iron Mountain: From Cold War Bunker to Digital Age Infrastructure

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

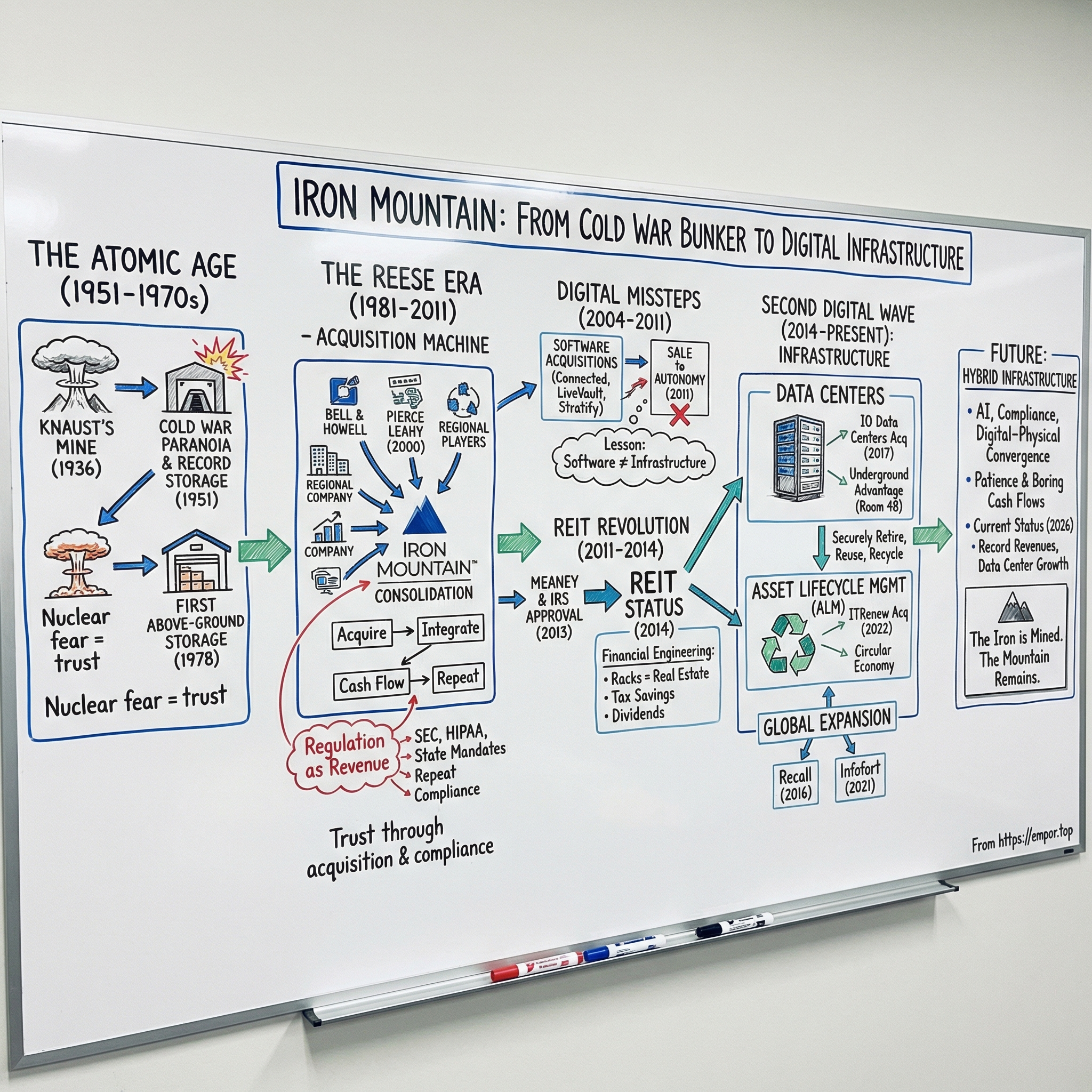

Picture this: it’s 1950. Herman Knaust is sitting on a depleted iron ore mine in upstate New York—an asset he bought for $9,000 back in 1936, originally with the very unglamorous plan of growing mushrooms. The mushroom business doesn’t pan out. But then Knaust starts reading headlines about the Soviet Union’s nuclear capabilities, and he sees a different kind of demand forming.

Not for backyard bomb shelters. For something corporate America is suddenly terrified of losing: its records. Its contracts. Its signatures. Its history. In Knaust’s mind, that abandoned mine isn’t a failed farm anymore. It’s a vault. A fortress for the documents that keep companies alive.

How does a mushroom farmer’s abandoned mine turn into a $25 billion-plus REIT? The answer runs through Cold War paranoia, waves of regulation, a few painful lessons in digital transformation, and a very modern realization: even in the cloud era, physical space still matters. Iron Mountain’s business isn’t just storage. It’s trust—built into infrastructure.

Today, Iron Mountain serves more than 240,000 customers across 61 countries, including approximately 95% of the Fortune 1000. Its footprint stretches across more than 1,400 facilities in over 50 countries, spanning more than 85 million square feet. But the path from one mine in Kingston, New York to a global information infrastructure company was anything but straight. It’s a story of pivots, roll-ups, reinventions, and a few moments where the company backed the wrong version of the future—until it didn’t.

Here’s where we’re headed. We’ll start in the atomic age, when “disaster recovery” meant nuclear war. Then we’ll move into the compliance era, when regulation turned paper into a permanent revenue stream. From there: the first digital push, why it didn’t work, and what Iron Mountain learned the hard way. Then comes the financial engineering—specifically, the REIT conversion that reshaped the company’s economics and investor base. And finally, the second digital wave: data centers, hybrid physical-digital infrastructure, and a new growth engine that fits Iron Mountain’s original advantage better than software ever did.

This is a story about patient capital and the power of boring, durable cash flows. It’s also about how the most valuable “tech” businesses sometimes look like real estate, logistics, and operations—not apps. Welcome to the Iron Mountain saga: where mushroom farms meet nuclear bunkers, paper meets pixels, and yesterday’s paranoia becomes tomorrow’s infrastructure.

II. The Atomic Age Origins: Herman Knaust's Vision (1936–1970s)

The caves beneath Rosendale, New York had been quiet since the ore played out. In 1936, Herman Knaust bought the mine and 100 acres for $9,000 with a simple idea: mushrooms. The temperature stayed a steady 52 degrees, the humidity was high, and on paper it looked perfect. In reality, for the next fourteen years, the mushrooms never quite behaved like a dependable business.

By 1950, Knaust needed a new plan—and the world handed him one. The Korean War had started. Senator Joseph McCarthy was on television warning about communists. And American companies were beginning to ask a question that sounds extreme now, but felt urgent then: if the Soviets drop the bomb, what happens to our records?

Suddenly, Knaust’s “failed” mushroom mine didn’t look like dead weight. It looked like a bunker.

In 1951, he founded Iron Mountain Atomic Storage Corporation. He opened underground vaults in the mine and, just as importantly, set up a sales office in the Empire State Building—about 125 miles south of where the records would actually live. The product wasn’t only the geology. It was the story. Knaust was a natural promoter, and he understood that in a trust business, perception matters. He persuaded high-profile visitors, including General Douglas MacArthur, to tour the site. The image sold itself: America’s most famous general walking into the mountain, steel doors behind him, cameras flashing. If MacArthur took it seriously, your board could too.

The first customer made the pitch real. East River Savings Bank began sending microfilm copies of deposit records and duplicate signature cards, transported in armored cars, up to the mountain facility. That visual—armored vehicles carrying financial identity into a fortified mine—wasn’t just good marketing. It captured the core promise: continuity. No matter what happened above ground, the bank’s proof of who owned what would still exist.

The Cold War anxiety was fuel, but Knaust’s obsession with preserving records ran deeper. After World War II, he had sponsored the relocation to the United States of many Jewish immigrants who had lost their identities when personal records were destroyed. He had seen what the loss of paperwork could do to a human life. That experience, combined with the era’s nuclear dread, gave Iron Mountain its mission: protect vital information from war and disaster.

And he didn’t aim only at big institutions. In the 1950s, for $2.50 a year, a consumer or small business could pack records into a tin can and store it in the mine. It was a clever way to monetize empty underground space, but it also revealed something fundamental about the company’s future. Individuals might gamble with inconvenience. A bank—or any regulated business—couldn’t. A family could risk losing keepsakes. A financial institution could not risk losing its ledger.

As the decades moved on, the business naturally expanded beyond nuclear scenarios. By the 1960s, the demand wasn’t just “protect this from a bomb.” It was “protect this from everything”: fires, floods, and the slow, everyday entropy that ruins paper. Compliance and risk management started to matter as much as Cold War survivalism.

In 1978, Iron Mountain opened its first above-ground records-storage facility. It was a turning point. The company was no longer just selling a doomsday vault. It was building a broader kind of infrastructure—places and processes that let companies move information off-site, safely, and still feel in control.

That’s the real magic Iron Mountain created early: a system where information could leave your building, but never truly disappear. The armored cars and the steel doors were dramatic, yes—but they were also a ritual. A way for companies to prove to themselves, to regulators, and to their customers that their most important records were being handled with care. Iron Mountain had taken paranoia and turned it into process. And that process would outlive the Cold War by decades.

III. The Reese Era: From Regional Player to National Consolidator (1981–2011)

In December 1981, Richard Reese arrived at Iron Mountain as president and CEO. The company was still a small, privately held regional operator doing about $3 million a year in revenue. Reese, a Harvard Business School lecturer who had never taken a finance course, was about to turn this niche business into a national machine. By the time he finally retired in 2013, Iron Mountain’s revenue was north of $3 billion.

Reese’s key insight was simple: this wasn’t really a storage business. It was a trust business. Companies weren’t paying for cardboard boxes and square footage. They were paying for the right to stop worrying—about losing documents, failing an audit, or not being able to prove what happened years later.

And trust, Reese realized, could scale fast if you bought it.

Every regional records management company Iron Mountain acquired came with something that was hard to build from scratch: long-standing customer relationships. In many cases, those relationships were measured in decades. These deals weren’t just about facilities or trucks; they were about persuading thousands of customers to keep doing what they’d always done, but now with Iron Mountain’s logo on the invoice. In a business like this, acquisitions weren’t just growth—they were trust transfers.

This was also the moment the company’s value proposition quietly shifted. The Cold War bunker story still worked, but the real driver became regulation. Through the 1980s and 1990s, the modern compliance state was piling on requirements that created paper by the ton. SEC rules, healthcare privacy requirements, state-level mandates—each new standard meant one thing in practice: more records that had to be stored, tracked, and retrievable on demand. Reese saw that for customers, compliance wasn’t a paperwork problem. It was an existential risk. And if it was a risk, it was something you could outsource.

So Iron Mountain started buying.

In 1988, it expanded into a dozen additional U.S. markets through the acquisition of Bell & Howell Records Management, Inc. Through the mid-1990s, growth accelerated sharply, and by 1998 the company reported revenue up 103% from the prior year. This wasn’t a sudden burst of operational genius or a viral product moment. It was consolidation—disciplined, relentless consolidation.

Then came the crown jewel.

In February 2000, Iron Mountain announced it had completed the acquisition of Pierce Leahy Corp. in a stock-for-stock merger valued at approximately $1.1 billion. Pierce Leahy wasn’t just another regional tuck-in. It was Iron Mountain’s primary rival—and a consolidator in its own right.

Pierce Leahy’s story rhymed with Iron Mountain’s. Founded by Leo W. Pierce Sr. in 1969, it began in the family’s garage and grew steadily to about $20 million in annual revenue over the next two decades. In 1990, J. Peter Pierce orchestrated the acquisition of Leahy Business Archives, helping create a true national records and information management company with around $40 million in annual revenue. He then led Pierce Leahy’s initial public offering on the New York Stock Exchange on July 1, 1997.

And Pierce Leahy had been running the same playbook at full speed. Between 1992 and 1999, it acquired and integrated more than 65 records and information management companies across the U.S. and internationally. This was a roll-up acquiring a roll-up—consolidation squared.

The combined company was enormous for the category. At the time, Pierce Leahy had an enterprise value of $1.2 billion, about 3,500 employees, and roughly $400 million in annual revenue. Together, Iron Mountain now served more than 115,000 clients through 77 facilities in the United States, nine Canadian operations, and joint ventures spanning Mexico, South America, and Europe.

By this point, Reese had effectively written the industry’s modern rulebook: acquire regional players for their customer relationships, integrate operations to gain scale, use the steady cash flow to fund the next wave, and repeat. It was boring. It was predictable. And it worked.

Reese stepped down as CEO in 2008, handing the role to Bob Brennan, then returned in 2011 after Brennan’s departure. By then, Iron Mountain had grown from a $3 million regional operator to roughly $2.7 billion in revenue. The mushroom mine had become an empire—built one acquisition, one facility, and one inherited relationship at a time.

IV. Digital Transformation Attempts & Missteps (2004–2011)

By the early 2000s, the ground was shifting under Iron Mountain’s feet. Paper was still everywhere, but the center of gravity was moving to hard drives, laptops, and servers. If Iron Mountain was going to remain the place companies trusted with their “vital records,” it couldn’t stay purely physical.

So in October 2004, Iron Mountain made what looked like its opening move into the digital world: it acquired Connected Corporation for $117 million in cash. Connected specialized in protecting, archiving, and recovering distributed data, and it had generated $18 million in revenue in the first half of 2004.

Richard Reese sold the idea with a line that could’ve come straight from Iron Mountain’s core identity: “go where our customers need us to be.” The customer need was real. A huge portion of corporate information was no longer sitting in file rooms or even centralized data centers. It was spread across laptops and desktops—data that was easy to lose, hard to control, and increasingly important.

Then Iron Mountain leaned in. In 2005, Iron Mountain Digital bought LiveVault, an online backup provider focused on server data, for about $50 million. LiveVault said it had grown more than 100 percent that year, serving 2,000 corporate clients and supporting 6 petabytes of data. In 2007, Iron Mountain acquired Stratify Inc., a sizable e-discovery services provider. These businesses were rolled up into a single unit, Iron Mountain Digital—on paper, a ready-made digital growth engine.

But by May 2011, Iron Mountain had effectively called it. The company sold Iron Mountain Digital to Autonomy Corporation for $380 million.

The economics told the story. Iron Mountain had spent roughly $437 million assembling the pieces—$117 million for Connected, $50 million for LiveVault, $158 million for Stratify, plus other acquisitions—then exited for less than that, before even counting the years of operating costs and integration effort. For a company built on predictable returns and long-lived customer relationships, it was an unusually expensive lesson.

So what went wrong?

Iron Mountain wasn’t just adding a new product line. It was stepping into a fundamentally different kind of business. Digital services meant competing with software companies that lived and died by product velocity: rapid release cycles, constant feature upgrades, and a relentless push toward simpler, cheaper, more self-serve experiences. Iron Mountain’s instincts—enterprise-heavy sales, premium positioning, and an operational culture designed around stability—fit the physical world perfectly. They were a mismatch in software.

And there was a subtler problem: the brand itself. Customers trusted Iron Mountain with paper because it felt permanent—secure, conservative, and unchanging. In the fast-moving digital world, those same traits could read as slow and outdated, not innovative and nimble.

When Reese returned as CEO in April 2011, after Bob Brennan’s departure, he framed the sale as part of delivering on the company’s strategic commitments. But the implication was hard to miss: Iron Mountain wasn’t going to win by trying to become a pure-play software company.

Still, the retreat mattered. Iron Mountain had now seen, up close, what “digital” actually demanded—and what it didn’t. That clarity would shape the company’s next pivot, when it found a version of digital that fit its real advantage: infrastructure, not applications.

V. The REIT Revolution: Financial Engineering Meets Storage (2011–2014)

January 7, 2013. William Meaney walked into Iron Mountain’s Boston headquarters with a mandate that sounded simple and was anything but: make this document-storage giant into something Wall Street would value differently. The plan he inherited—and would have to finish—was audacious in the most Iron Mountain way: convince the IRS that a key part of the company’s business wasn’t “equipment,” but real estate.

Meaney was an unusual fit on paper for a storage company CEO, which was exactly the point. He had a mechanical engineering degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and an MBA from Carnegie Mellon’s Tepper School of Business. He’d spent time as a CIA operations officer, then moved through management consulting, airline leadership roles at South African Airways and Swiss International Airlines, and ultimately ran Hong Kong’s Zuellig Group as its first non-family CEO—tripling sales there from $4 billion to $12 billion. He and his Swiss wife relocated from Hong Kong to Boston for the job. That range of experiences gave Meaney a valuable talent: he could look at Iron Mountain not as a legacy “boxes and trucks” company, but as a set of cash flows and assets that could be re-framed.

His timing was no accident. Iron Mountain had been under activist pressure: Elliott Management took a large position in late 2010 and, in early 2011, succeeded in getting four nominees onto the board—two with experience converting companies into REITs. The board had already approved pursuing REIT status in June 2011 after what it described as a “thorough analysis of alternative financing, capital and tax strategies.” But approval wasn’t a paperwork exercise. It was a fight.

The fight came down to a question that sounds trivial until you realize it determined the company’s entire tax structure: what, exactly, counts as real estate?

To qualify as a REIT, at least 75% of income has to come from real estate. Iron Mountain’s warehouses obviously counted. But the business didn’t really happen in the empty warehouse; it happened in the dense steel racking systems that turned air into storage capacity. If those racks were treated as equipment instead of real estate, Iron Mountain couldn’t pass the REIT tests. And if it couldn’t pass the tests, the whole strategy collapsed.

In June 2012, the IRS delivered what felt like a death blow: it was “tentatively adverse” on Iron Mountain’s private letter ruling request that the racking structures qualified as “real estate” for REIT purposes. Investors got whiplash. The stock drifted in the high 20s to low 30s as sentiment swung back and forth and more than a few people concluded this was never going to happen.

Meaney and the team didn’t back off. Their case was that these racks weren’t removable accessories; they were “inherently permanent structures” and “structural components,” as integral to the buildings as elevators or HVAC systems. They kept pushing until, on June 25, 2014, the answer finally came back: yes. The IRS approved Iron Mountain’s REIT conversion plan, and the stock jumped more than 20% in after-hours trading.

The payoff was enormous. The ruling implied annual tax savings of roughly $130 million to $150 million. And because REITs are built to pass income through to shareholders, Iron Mountain would now distribute at least 90% of its taxable income. It also announced plans to distribute $1 billion to $1.5 billion in accumulated earnings and profits, including a special distribution of $600 million to $700 million expected in the second half of 2014.

Zoom out, and the logic snaps into focus. This was a business with predictable, recurring revenue and unusually sticky customers—people don’t move boxes unless they absolutely have to. The economics looked far closer to leased space than to a typical service business. The REIT conversion wasn’t just financial engineering for its own sake. It was an admission of what Iron Mountain had effectively been all along: a real estate company, purpose-built for storing information instead of housing tenants.

And in the end, the entire transformation hinged on one strangely poetic detail—steel shelves. Meaney, the former CIA officer turned conglomerate executive, had helped pull off a corporate identity change by persuading the IRS to see the company the way Iron Mountain had always wanted customers to see it: not as a storage vendor, but as infrastructure.

VI. The Second Digital Wave: Data Centers & Infrastructure (2014–Present)

The second digital wave didn’t start with a big strategy deck. It started with customers asking a practical question. Not long after the REIT conversion, in 2014, companies that already trusted Iron Mountain with their most sensitive paper records began asking: can you store our servers the way you store our boxes?

It was the right kind of digital for Iron Mountain. Last time, they tried to win in software—backup, archiving, e-discovery—and found themselves in a world of fast product cycles and brutal competition. This time, they stayed in their lane. Iron Mountain wasn’t going to fight Amazon Web Services or Microsoft Azure. The bet was simpler: even in a cloud-first world, someone still has to run the physical infrastructure. Data centers weren’t a departure from Iron Mountain’s identity. They were an extension of it—secure, compliance-heavy real estate, designed for things customers can’t afford to lose.

That strategy went from “interesting” to “real” in December 2017, when Iron Mountain acquired IO Data Centers’ U.S. operations for $1.315 billion, plus up to $60 million tied to future performance. Overnight, Iron Mountain owned four modern data centers in Phoenix and Scottsdale, Arizona; Edison, New Jersey; and Columbus, Ohio. The footprint was substantial: 728,000 square feet, 62 megawatts of capacity, and room to expand by another 77 megawatts. Meaney described it as a measured transformation—bringing data centers to roughly 7% of total revenue—not a sudden tech pivot, but a deliberate move into a faster-growing corner of the same infrastructure business.

Then came the uniquely Iron Mountain twist: the underground advantage.

Room 48 is a data center built 220 feet underground, inside a section of a Pennsylvania limestone mine. Down there, the ambient temperature sits around 52 degrees—naturally cool, naturally stable. The facility also uses a 35-acre underground lake for geothermal cooling, avoiding the need for power-hungry chillers. The U.S. Department of Energy recognized it as a Better Buildings Showcase Project. It wasn’t just a clever reuse of old space. It was the kind of structural cost advantage that most data center competitors can’t simply decide to copy.

By 2025, what started as a 7% revenue contribution had grown into a major engine. In the third quarter of 2025, data center revenue grew 33% year over year, and the company projected data center revenue would exceed $1 billion and grow more than 25% in 2026. Iron Mountain operated about 424 megawatts of capacity globally with occupancy near 96%, and its broader data center portfolio spanned 1.3 gigawatts across three continents.

And they weren’t slowing down. In late 2024, Iron Mountain acquired more than 100 acres in Virginia with plans to develop over 350 megawatts of new capacity—more than 200 megawatts in Richmond and roughly 150 megawatts in Manassas. The Richmond campus at White Oak Technology Park was designed with heavily regulated customers in mind, carrying compliance certifications including HIPAA, FISMA High, PCI-DSS, and ISO 27001.

In February 2025, the company broke ground on its first Miami data center, MIA-1: a 150,000-square-foot, AI-ready facility delivering 16 megawatts of capacity. It was slated to run on 100% carbon-free energy when it launched in 2026. Construction also began on AZP-3 in Phoenix, with the first phase targeting a late-2025 launch. Internationally, a 42-megawatt campus in Chennai, India was underway, and LON-3 in London—a three-story, 25-megawatt facility with GPU-ready data halls—began a phased opening through 2026.

In April 2025, Iron Mountain acquired the remaining stake in Web Werks and rebranded the India business to Iron Mountain Data Centers, strengthening its position in one of the world’s fastest-growing data center markets.

So why did this digital push work when the last one didn’t?

Because it let Iron Mountain stay true to what it had always been: a trust-and-compliance company expressed through physical infrastructure. The hybrid model was the unlock. Customers already trained themselves to rely on Iron Mountain for critical records; extending that trust from boxes to servers was a smaller leap than asking them to buy software from a company best known for storage. And the same regulatory muscle that made Iron Mountain indispensable in records management made it attractive in data centers, especially for industries where audits and certifications aren’t optional.

Iron Mountain didn’t need to become the cloud. It just needed to own more of the ground the cloud sits on.

VII. Global Expansion & The Recall Acquisition (2015–2020)

April 27, 2015. Iron Mountain went back to what it did best—buying scale—but this time the prize wasn’t another U.S. metro area. It announced a deal to acquire Recall Holdings, an Australian data protection services provider, for about $2.2 billion in cash and stock. For Meaney, it was the clearest signal yet that the company wasn’t content to be a North American records giant with a few outposts. It wanted to be global infrastructure.

By June 8, 2015, the definitive agreement was signed, valuing the transaction at approximately $2.6 billion in cash and stock. Recall wasn’t a random target. It was, in many ways, Iron Mountain’s counterpart in Asia-Pacific—an established information management player with the kind of footprint Iron Mountain couldn’t quickly build on its own.

Then came the hard part: regulators.

On March 31, 2016, the United States filed a civil antitrust complaint alleging the deal would reduce competition for hard-copy records management services in fifteen metropolitan areas, including Detroit, Kansas City, Atlanta, and Seattle. Iron Mountain agreed to divest Recall’s records management assets in those markets. Canada’s Competition Bureau required divestitures in six cities: Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, Calgary, Edmonton, and Vancouver. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority demanded the sale of Recall’s operations in Aberdeen and Dundee.

And Australia delivered the ultimate twist. To buy an Australian company, Iron Mountain effectively had to step back from its own Australian records management business, divesting most of it.

Even after all that, the deal still went through. On May 2, 2016, Iron Mountain completed the acquisition for approximately $2 billion, mostly in stock—down from the original headline number, reflecting the impact of those divestitures. Shareholders overwhelmingly approved it, with 99.9% of votes cast in favor. What Iron Mountain got was Recall’s global operations, minus the pieces regulators forced out. What it gave up was the idea that “global” could be achieved without painful trade-offs.

The strategic logic survived the haircut: multinational customers wanted consistency. They wanted one vendor, one set of standards, one relationship—across regions and time zones. Recall helped Iron Mountain get much closer to that.

And the company kept going. In February 2021, Iron Mountain expanded further into emerging markets by acquiring Infofort, the largest information management solutions provider in the Middle East, North Africa, and Turkey (MENAT) region. Founded in 1997 and headquartered in Dubai, Infofort served clients across 13 countries with document storage, destruction, digitalization, and backup management services. The acquisition added 12 facilities across eight new countries to Iron Mountain’s footprint.

Zoom out, and the pattern is clear. Information management may look local—boxes, trucks, buildings—but the customers that matter most aren’t. Iron Mountain’s global push was a response to that reality: if your clients operate everywhere, the vendor they trust has to be able to show up everywhere, too.

VIII. Asset Lifecycle Management & The Circular Economy Play (2020–Present)

January 2022. William Meaney was at ITRenew’s Silicon Valley headquarters, watching technicians break down racks of servers fresh from a hyperscaler decommission. Machines that had powered the internet a few weeks earlier were now being stripped to components—tested, wiped, refurbished, and sorted into their next destination: resale, reuse, or recycling.

This wasn’t “storage” in the Iron Mountain sense. It was value recovery—extracting what’s left from some of the fastest-depreciating assets in corporate America. And Iron Mountain was about to wager that this, too, belonged in its wheelhouse.

On January 26, 2022, Iron Mountain completed its acquisition of ITRenew, buying 80 percent of the outstanding shares for approximately $725 million in cash, with the remaining 20 percent to be acquired within three years for a minimum enterprise value of $925 million. Founded in 2000, ITRenew primarily served hyperscalers—the fastest-growing segment of the global IT Asset Disposition market—helping maximize the lifetime value of data center servers through sustainable asset disposition, recycling, and remarketing. At the time, ITRenew had trailing twelve-month revenue of more than $415 million and a two-year compounded annual growth rate of roughly 16 percent.

The strategic logic was straightforward. Hyperscalers like Amazon, Microsoft, and Google refresh data center infrastructure every three to four years. That creates a constant wave of still-working equipment that can’t just be tossed in a dumpster. It has to be decommissioned securely. It has to be handled with chain-of-custody discipline. And if you do it right, there’s real money left in the hardware.

ITRenew’s circular model turned that wave into a system. Refurbished equipment could be remarketed to smaller companies that couldn’t justify new enterprise-grade servers. What truly reached end-of-life could be recycled responsibly, recovering materials instead of sending them to landfill. In other words: less waste, more value, and a process customers could trust.

Then the numbers started to tell their own story. ALM revenue jumped 145% year over year to $102 million in Q3 2024. By Q3 2025, the business was still accelerating, delivering 65% reported and 36% organic revenue growth. This wasn’t a one-off pop—it tracked a world where refresh cycles kept tightening and sustainability expectations kept rising.

Iron Mountain didn’t stop at one platform, either. It expanded ALM through additional acquisitions, including Premier Surplus, an IT asset disposition leader based in Georgia, and Wisetek, a global ITAD and manufacturing services provider headquartered in Cork, Ireland. The point was coverage: more geographies, more capability, and more control over the full asset lifecycle.

And the sustainability story clicked. Data centers were consuming a growing share of electricity, and the environmental cost of manufacturing new equipment was becoming harder to ignore. Extending the life of a server isn’t just a margin opportunity—it avoids the emissions and resource use that come with making a replacement. Iron Mountain’s data centers already ran on 100 percent renewable energy, and ALM added a second engine to the same theme: not just powering the digital world, but cleaning up after it.

The arc is almost absurd when you zoom out. Iron Mountain began by protecting paper in a mine. Now it was helping the largest computing companies on Earth securely retire, reuse, and recycle the machines that run the modern internet. Same core business, new substrate: trust, expressed through process—only now the boxes are servers, and the mountain is the supply chain itself.

IX. Financial Performance & Business Model Analysis

Iron Mountain’s financials read like a company that found its second act—and then kept going. In 2024, it posted record results: $6.1 billion in revenue, record Adjusted EBITDA of $2.2 billion, and AFFO of $1.34 billion. The fourth quarter capped it off with another set of highs, including $1.6 billion in revenue and $605 million in Adjusted EBITDA.

That strength didn’t fade in 2025. In Q3 2025, Iron Mountain delivered record quarterly revenue of $1.8 billion, up strongly year over year even after adjusting for foreign exchange. What’s most telling is where the growth came from: the newer engines—data centers, digital solutions, and ALM—grew more than 30% year over year. William Meaney called it “another quarter of very strong performance,” with new records across revenue, Adjusted EBITDA, and AFFO.

To understand why Iron Mountain can produce this kind of consistency, you have to look at the mix. Storage rentals still sit at the core: about 60% of revenue and roughly 80% of gross profits, with EBITDA margins around 75%. This is the elegant part of the model. Once a box is in an Iron Mountain facility, it tends to stay there—on average, for about 15 years—while costing very little to keep. It’s a subscription business hiding inside a warehouse business: low churn, high predictability, and margins that widen over time. Services are lower margin, but they’re the glue—pickup, retrieval, shredding, scanning—the touchpoints that keep customers embedded.

Meanwhile, the growth segments are no longer “future optionality.” They’re changing the company’s profile in real time. Data center revenue grew 33% in Q3 2025, with Iron Mountain projecting the segment would top $1 billion in revenue in 2026 and grow more than 25%. ALM grew 65% on a reported basis in the same quarter. These businesses don’t just add growth—they change how investors are supposed to value the whole company.

The REIT conversion continues to show up where it matters: in shareholder returns and financial flexibility. In November 2025, the board declared a quarterly dividend of $0.864 per share, a 10% increase, bringing total dividends to $3.07 per share for 2025. Net lease adjusted leverage was about 5.0 times—its lowest level since the REIT conversion—giving Iron Mountain more room to fund expansion without stretching the balance sheet.

That funding is increasingly aimed at data centers. Iron Mountain planned to lease roughly 125 megawatts of additional capacity in 2025, and capital spending followed the opportunity. With occupancy near 96%, the math is straightforward: keep building where demand is strong and contracts are sticky.

And yet, the market hasn’t fully moved with the story. Iron Mountain still traded at a meaningful discount to pure-play data center REITs, despite its growing exposure to that higher-multiple business. Investors who saw the company as a slow-motion decline in paper storage tended to miss what the numbers were already showing: this wasn’t just a records company anymore. It was becoming a diversified information infrastructure platform—and the valuation gap was the bet.

X. Competitive Dynamics & Strategic Positioning

In records management, competition looks less like a knife fight and more like a map with one name written in bold. In North America, Iron Mountain’s records management business is about ten times the size of its next-largest competitor, Access Information Management. That isn’t just leadership. That’s gravity.

The moat is layered, and each layer reinforces the next.

Start with sheer footprint. With more than 1,400 facilities around the world, Iron Mountain can show up wherever its customers operate. A multinational with offices across continents doesn’t want a patchwork of local vendors and a dozen different contracts. It wants one relationship, one standard, and the comfort of knowing the same playbook applies everywhere. At global scale, Iron Mountain is often the only realistic choice.

Then there are switching costs—brutal, and very real. Getting your own records back isn’t free. “Permanent withdrawal fees” can run into the hundreds of dollars per box, turning a provider change into a budget event. The customer isn’t locked in by a clever contract clause. They’re locked in by the physical and financial reality of moving mountains of paper.

And above it all sits compliance. Whether it’s HIPAA in healthcare or the alphabet soup of security standards that show up in government and regulated enterprise environments—FISMA High, FedRAMP, ISO 27001—Iron Mountain has spent decades building the processes, controls, and certifications that make auditors comfortable. New entrants can rent a warehouse. They can’t rent seventy years of operational trust.

If you like Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, Iron Mountain checks multiple boxes. Scale economies mean each incremental customer becomes cheaper to serve across an existing network. Switching costs discourage churn in a way few businesses can match. Brand matters because the product is peace of mind. And some resources are effectively cornered: unique underground facilities and a compliance posture that’s hard to replicate at global scale.

Porter’s Five Forces tells a similar story. Suppliers have limited leverage—racking and real estate are inputs you can buy in many places. Buyers have limited power because the service is mission-critical and hard to unwind. New entrants face capital intensity, long timelines to earn trust, and a compliance uphill climb. Substitutes, like cloud storage and paperless workflows, are the real long-term pressure—but it’s a slow, secular drag, not a sudden cliff. Legal, regulatory, and practical realities keep physical records alive far longer than “paperless office” predictions suggest.

Data centers are a different arena. Here, Iron Mountain isn’t the biggest player in the room. Digital Realty and Equinix dominate colocation with much larger footprints. But Iron Mountain isn’t trying to win by being the broadest commodity platform. It’s leaning into what it already does better than almost anyone: security, compliance, and long-standing enterprise relationships—especially in heavily regulated industries. And it has a differentiator that’s hard to copy: the Underground facility, which offers a physical profile that pure-play data center REITs simply can’t replicate.

This is where Iron Mountain’s “convergence” strategy starts to look less like a slogan and more like positioning. Physical storage, data centers, and asset lifecycle management don’t just coexist—they reinforce each other. Few companies can offer secure document storage, critical digital infrastructure, and secure IT asset disposition at global scale. It’s not only about being big. It’s about being the only vendor that can plausibly cover the full lifecycle of information and the infrastructure around it.

If you’re tracking whether this strategy is working, two metrics do most of the work. First: data center leasing velocity—how many megawatts get leased each quarter—because it shows whether the growth engine is keeping pace with the capital going into new capacity. Second: organic storage rental revenue growth, because it tells you whether the core cash generator still has pricing power and staying power. Together, they answer the real question: is Iron Mountain funding its future without losing the foundation that paid for everything in the first place?

XI. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

The Power of Boring Businesses with Predictable Cash Flows. Iron Mountain is proof that “boring” can be a superpower. Nobody brags about document storage at a cocktail party, but this is exactly the kind of business that throws off dependable, recurring cash. Customers sign up, pay regularly, and once their records are in the system, they tend to stick around for a long time—on average about 15 years. And after the hard work of onboarding, the ongoing cost of keeping one more box on a shelf is tiny. The takeaway is simple: customer inertia can be a feature, not a flaw.

Roll-up Strategies: When They Work and When They Don't. Under Richard Reese, Iron Mountain ran one of the cleanest roll-up playbooks you’ll ever see. Buy small regional operators, integrate them, use the newly consolidated cash flow to fund the next set of deals, and repeat. The real asset wasn’t the buildings. It was the customer relationships—sticky, local, and slow to recreate from scratch. But roll-ups only work when the pieces actually fit together operationally. Iron Mountain’s digital services push showed the other side of the coin: buying software companies and expecting them to mesh wasn’t consolidation—it was wishful thinking. Roll-ups work best in fragmented industries where scale truly lowers costs and increases defensibility. They fail when you’re just piling up unrelated assets and hoping for synergy to appear.

Financial Engineering as Competitive Advantage. The REIT conversion wasn’t just a tax tweak. It was a redefinition of what Iron Mountain was. By persuading the IRS that its steel racking qualified as real estate, the company changed its economics, its investor base, and its ability to return capital. The deeper lesson is that sometimes the biggest unlock isn’t a new product or a new market—it’s getting the world to price your business the way it actually operates. Iron Mountain had long behaved like real estate wrapped around a trust service. The REIT structure finally made that official.

Pivoting Without Abandoning Core Competencies. Iron Mountain’s second act—data centers and asset lifecycle management—worked because it built directly on what the company already did well: security, compliance, chain of custody, customer trust, and running physical infrastructure. The earlier digital attempt failed because it asked Iron Mountain to compete like a software company, in a business where speed and product iteration matter more than permanence. The best pivots don’t erase your strengths. They extend them into adjacent markets. Storing servers is a natural cousin to storing documents. Building backup software was a different sport.

Building Trust in Trust-Based Businesses. The product Iron Mountain really sells is peace of mind. Customers hand over some of their most sensitive information and expect it to remain secure, confidential, and retrievable when it matters. That kind of trust compounds slowly and, once earned, becomes brutally hard for competitors to replicate. In trust-based businesses, marketing can open the door—but operations are what keep it open for decades.

The Patience Required for Infrastructure Plays. Iron Mountain didn’t become what it is overnight. The journey from a $9,000 mine purchase to a $25 billion-plus REIT took more than seventy years. That’s the nature of infrastructure businesses: moats form gradually. Relationships deepen over time. Compliance muscle is built audit by audit. Scale advantages compound quietly. It’s slow, until it isn’t—and then it’s incredibly hard to dislodge.

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case & Investment Analysis

Bear Case: The Secular Decline Thesis

The bear case starts with a blunt premise: paper is in structural decline. In mature markets, stored volumes have been slipping as companies digitize workflows. The pandemic poured gasoline on that shift—remote work proved that, for most day-to-day operations, a filing room isn’t mission-critical. Iron Mountain has fought back with price increases and add-on services, but there’s an obvious ceiling. If the box count keeps shrinking, pricing can’t do all the work forever.

Then there’s the data center question. Iron Mountain is competing in a field dominated by specialists like Digital Realty and Equinix—and, at the top of the food chain, by hyperscalers that increasingly want control over their own infrastructure. Even with hundreds of megawatts operating and a much larger development pipeline, bears argue Iron Mountain is still subscale relative to the purpose-built data center REITs. Data centers also demand relentless capital spending. If pricing pressure rises or demand softens, that buildout could deliver disappointing returns.

Balance sheet and structure add another layer of concern. Even though net lease adjusted leverage improved to around 5.0 times, it’s still meaningful for a company whose original engine—physical records storage—faces long-term headwinds. And the REIT model comes with a trade-off: distributing at least 90% of taxable income is great for yield, but it can reduce flexibility when the business needs to fund growth or weather a downturn.

Finally, the newer growth engines have their own dependencies. With sizable international operations, currency swings can inject volatility. And Asset Lifecycle Management, while growing fast, is tied to hyperscaler refresh cycles and the health of secondary hardware markets. If the cloud giants decide to run equipment longer to cut costs—or if geopolitical tensions disrupt where that used gear can be sold—growth could cool quickly.

Bull Case: The Infrastructure Transformation Thesis

The bull case argues Iron Mountain is being priced like yesterday’s company, not today’s. In this view, it’s not a melting-ice-cube storage business—it’s an information infrastructure platform, built on assets that are hard to replicate and increasingly relevant.

Start with the moat. A global footprint of more than 85 million square feet across roughly 1,400 facilities in 50-plus countries isn’t something a competitor can spin up with a few years of capex. The replacement cost would be enormous, and some sites—like the Underground facility and the original mountain vaults—aren’t just expensive to reproduce. They’re effectively one-of-one.

Next: the “paper is dying” story is real, but incomplete. Iron Mountain serves approximately 95% of the Fortune 1000, and regulation creates a stubborn long tail. Legal holds, retention schedules, audits, and compliance requirements don’t vanish just because a company rolls out new software. Meanwhile, the growth engines are now large enough to matter. Data center revenue grew 33% year over year in Q3 2025, and the company projected the segment would exceed $1 billion in revenue in 2026. ALM posted 65% reported growth. Together, these lines were growing more than 30% year over year—fast enough to change the overall trajectory.

Bulls also point to the REIT structure as a form of downside support: a dividend that was increased 10% in late 2025 helps anchor the story for income-focused investors. And because Iron Mountain still traded at a discount to data center REIT peers, believers see a setup where execution drives a “re-rating.” If the company keeps proving the mix shift is real, the market has to stop valuing it like a slow decline.

There’s also evidence Iron Mountain is expanding into new categories of work that look a lot more like modern digital services than “boxes in warehouses.” In September 2025, the company secured a $714 million, five-year U.S. Treasury contract for IRS digitization services—a meaningful signal that government-scale digital transformation is now part of the opportunity set.

Finally, regulation isn’t just supporting the legacy business—it may be creating new demand. Data sovereignty rules, privacy regulation, AI governance frameworks, and the general rise in compliance complexity all push companies toward more careful information management. GDPR, CCPA, the EU’s AI Act, and emerging standards don’t reduce documentation. They multiply it—and raise the stakes of getting it wrong.

Holistic Assessment

The reality is messier than either extreme. Physical storage faces genuine secular pressure, and data centers and ALM aren’t risk-free growth stories. But Iron Mountain has also put real proof on the board: record financial results in 2024 and 2025, accelerating growth in its newer segments, and expanding capabilities beyond traditional records management. At current valuations, the tension is the point. The market often seems to assume the bear case and underwrite the bull case at a discount. The investment question is whether the transformation is durable—and with each new quarter of record results, it becomes harder to argue it’s just a temporary detour.

XIII. The Future: AI, Compliance, and Digital-Physical Convergence

The AI revolution isn’t replacing Iron Mountain’s business. It’s turning the volume up.

Every large language model trained on corporate data, every automated decision engine, every algorithmic system produces more data that has to be stored, governed, and secured. And here’s the paradox: the more digital the world gets, the more physical infrastructure it needs to run.

Training a modern AI model can mean storing and processing petabytes of data. But the real sprawl isn’t just raw storage. AI also creates a growing demand for audit trails, compliance documentation, and version history—records that regulators increasingly want maintained in ways that are tamper-resistant and retrievable.

If you’re not steeped in AI infrastructure, here’s the simplest way to think about it. A large language model is like a student that reads every book in a massive library to learn how to write. The books have to live somewhere. The collection has to be organized and preserved. And if the student’s work is going to be trusted, someone has to track what it read, what sources it used, and what changed over time. That “somewhere,” that organization, that chain of custody—that’s where Iron Mountain fits.

At the same time, data sovereignty and compliance rules are creating new categories of demand. The European Union’s Digital Services Act, China’s data localization requirements, and emerging AI governance frameworks are all pushing companies toward more specific, more constrained data-handling practices. The old default—dump it all in one cloud region and call it a day—doesn’t look so simple anymore. In a world where data is increasingly fragmented by geography and regulation, Iron Mountain’s global network of physical facilities starts to look less like legacy footprint and more like strategic infrastructure.

Climate risk adds another tailwind. Extreme weather events are becoming more common, and that makes disaster recovery feel less like a checkbox and more like a board-level concern. Companies are also relearning an uncomfortable truth: “multiple availability zones” don’t help much if a whole region loses power. Geographic distribution still matters. Physical backup across distributed locations—what Iron Mountain has been selling, in one form or another, for decades—becomes resilience infrastructure again.

Then there’s edge computing. As more AI processing moves from centralized clouds to distributed locations closer to where data is generated, demand grows for smaller-scale data center capacity in more places. Iron Mountain’s vast facility network creates an intriguing possibility: sites that can support workloads closer to where they’re needed.

All of this points to the same idea: the convergence of physical and digital isn’t a slogan. It’s physics and policy.

Every digital transaction creates heat that has to be dissipated. Every AI model runs on physical servers that eventually have to be decommissioned—securely—through ALM. Every compliance requirement produces records that must be retained and produced on demand. Iron Mountain is positioning itself where these threads meet.

And the regulatory environment keeps raising the stakes. The SEC’s cybersecurity disclosure rules, the EU’s AI Act, and emerging quantum-computing considerations don’t reduce the need for information management. They formalize it. You can’t regulate away the need to store, secure, and prove what happened. You can only make it more critical.

XIV. Epilogue & Reflections

If you stand in Iron Mountain’s original facility in upstate New York, the place still feels like it’s keeping secrets. You can see the chisel marks from the 1800s, when miners carved the ore out by hand. The mushroom racks from Herman Knaust’s failed farming experiment are long gone. In their place: row after row of storage, engineered for stability—temperature, humidity, access, chain of custody. The cave is the same. The mission is the same. The payload changed.

Iron Mountain is the rare transformation that didn’t require burning down the past. It compounded on it.

It’s also a reminder of what patient capital actually looks like. In a world conditioned to expect breakout growth in a handful of years, Iron Mountain took more than seven decades to become a $25 billion-plus company. But it didn’t get there by chasing hype. It got there by staying profitable, paying dividends, and quietly becoming embedded in how the world’s largest organizations manage risk. This is what lasting infrastructure looks like: slow, stubborn, and then—suddenly—irreplaceable.

It’s hard not to wonder what Herman Knaust would think if he could walk the halls today. The Hungarian immigrant who bought a depleted mine for $9,000 almost certainly didn’t picture a global platform spanning records storage, data centers, and asset lifecycle management. But he would recognize the core insight that drove the original pivot: valuable things need protection, and protection is worth paying for. In the 1950s, it was corporate records shielded from catastrophe. Today, it’s servers, compliance workflows, and the secure retirement of the machines running the modern economy. Different medium, same promise.

Iron Mountain’s story also flips a few pieces of conventional business wisdom on their heads.

First: sometimes the right response to disruption is not to sprint, but to pace. Digitization threatened the box business, and Iron Mountain didn’t pretend paper would last forever. But it also didn’t abandon the cash engine that funded everything. It diversified methodically, while continuing to do what it did best.

Second: “boring” can be a moat. Document storage isn’t glamorous, which is exactly why it can be so attractive. The work is operational, regulated, and trust-heavy—hard for newcomers to replicate, and not the kind of market that produces endless copycats.

Third: physical assets don’t matter less in the digital age. They matter more. Every cloud still sits on real ground. Every AI model runs on physical servers that need power and cooling. Every regulation ultimately demands something tangible: a record you can retrieve, prove, and defend.

Zoom out far enough and Iron Mountain becomes a meditation on compounding. Over decades, it built facilities, routings, processes, certifications, customer relationships, and a brand that essentially means “safe hands.” Those things don’t show up all at once. They accrue—one audit, one retention schedule, one renewal, one acquisition at a time—until the company becomes the default.

And the need isn’t going away. The Sumerians had clay tablets. The Romans had scrolls. The British Empire had ledgers. The atomic age had microfilm. The digital age has servers. The medium changes, but the need stays stubbornly consistent: information has to be stored, controlled, secured, and produced on demand.

As of January 2026, AI is reshaping workflows, data volumes are exploding, and regulation keeps getting more complex. That doesn’t reduce the importance of information management—it raises the stakes. Someone still has to manage the physical infrastructure of the digital world. Iron Mountain, still growing and still reinventing, looks built for that job.

The iron has been mined. The mountain remains.

XV. Recent News

By the third quarter of 2025, Iron Mountain was still putting up the kind of numbers that make a “legacy storage company” label hard to defend. It posted record quarterly revenue of $1.8 billion—up 12.6%—and set all-time highs for Revenue, Adjusted EBITDA, and AFFO. The mix shift kept showing up, too: the growth businesses—data centers, digital solutions, and ALM—were up more than 30% year over year.

The data center buildout remained the headline. In February 2025, Iron Mountain broke ground on its first Miami data center, a 16-megawatt, AI-ready facility targeted for completion in 2026 and planned to run on 100 percent carbon-free energy. It also acquired more than 100 acres in Virginia, with plans to develop over 350 megawatts of new capacity across Richmond and Manassas. Construction began on AZP-3 in Phoenix, a 42-megawatt campus in Chennai was underway, and the LON-3 facility in London—25 megawatts across six GPU-ready data halls—moved through a phased opening. In April 2025, Iron Mountain bought the remaining stake in Web Werks and rebranded the India business to Iron Mountain Data Centers.

Then came a very different kind of “digital” win—one that played straight into Iron Mountain’s brand of operational trust. In September 2025, it secured a $714 million, five-year contract with the U.S. Department of the Treasury for IRS digitization services. The award replaced an earlier $79.7 million contract from April 2025, and it marked a meaningful expansion into government-scale digital transformation. Revenue was expected to come in steadily over the life of the contract, with seasonal peaks tied to tax season.

Shareholders got their own clear signal that the cash engine was still humming. In November 2025, the board declared a quarterly dividend of $0.864 per share—a 10% increase—payable January 6, 2026. Total 2025 distributions reached $3.07 per share.

Next up, Iron Mountain scheduled its fourth quarter and full-year 2025 earnings release for February 12, 2026. The company was projecting data center revenue would exceed $1 billion in 2026, with growth above 25%, and it expected high seasonal volumes from the Treasury contract in spring 2026.

XVI. Links & Resources

Iron Mountain Investor Relations and Quarterly Results: investors.ironmountain.com

Iron Mountain Data Center Locations and Portfolio: ironmountain.com/data-centers/locations

Iron Mountain Asset Lifecycle Management: ironmountain.com/services/it-asset-lifecycle-management

Iron Mountain Leadership: ironmountain.com/about-us/leadership

SEC EDGAR filings for Iron Mountain Incorporated (IRM): sec.gov/edgar

NAREIT (National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts): reit.com

Acquired.fm podcast archive (for related infrastructure and REIT episodes): acquired.fm

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music