Automatic Data Processing (ADP): The Payroll Processing Powerhouse

Introduction and Episode Setup

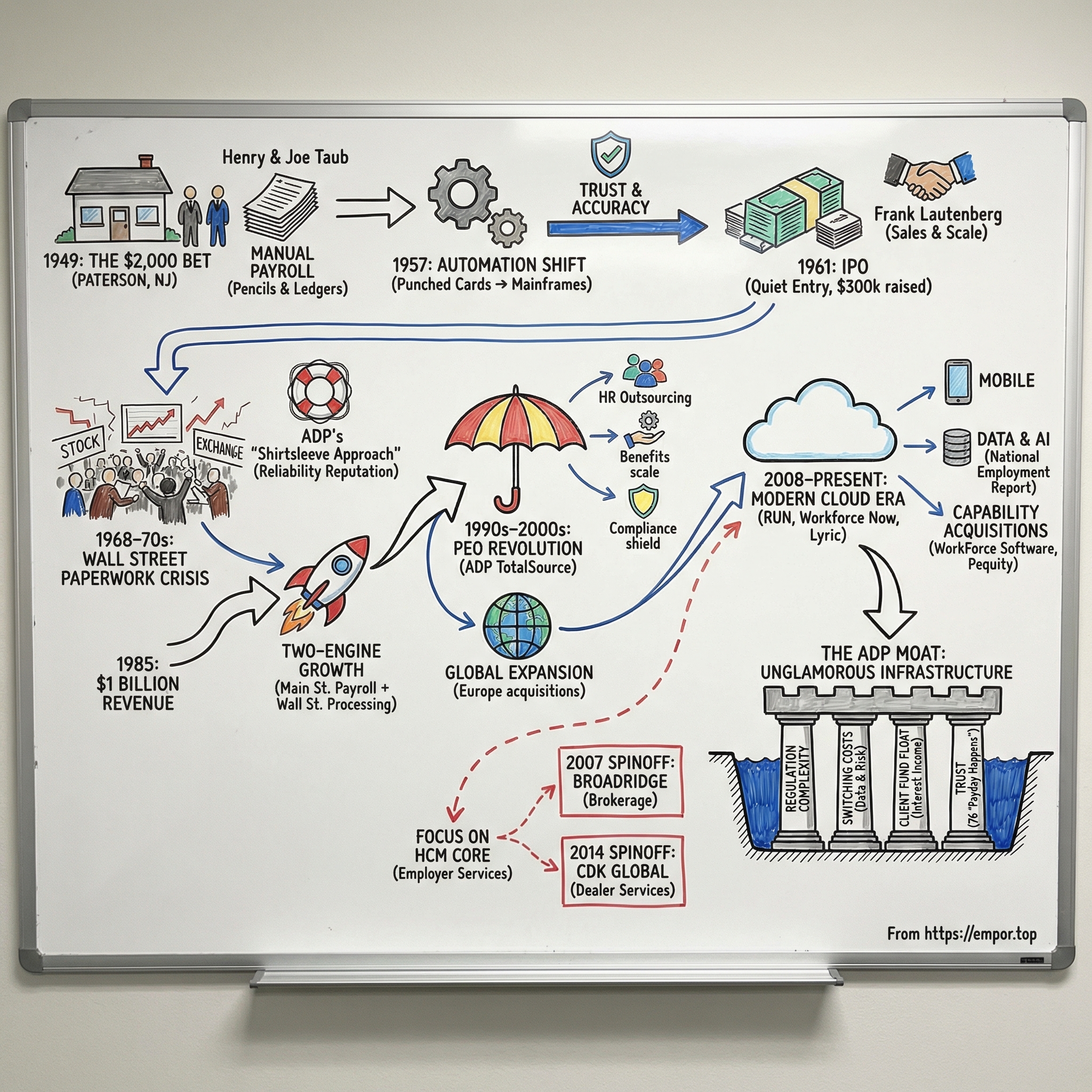

Every two weeks, roughly one in six American private-sector workers gets a paycheck that was calculated, taxed, filed, and delivered by the same company. Not a bank. Not the government. A 76-year-old firm headquartered in Roseland, New Jersey—one most people never think about until something goes wrong with their direct deposit. Automatic Data Processing, or ADP, is the invisible plumbing beneath the American labor market. And increasingly, it’s part of the payroll infrastructure in 140 countries around the world.

By fiscal year 2025, ADP was generating $20.6 billion in revenue, employing roughly 67,000 people, and serving more than a million client organizations. Its monthly National Employment Report doesn’t just make headlines—it can move markets, shaping expectations for the economy before the official government numbers land. ADP has been in the S&P 500 for decades and, for a long stretch, enjoyed a near-mythic reputation in corporate finance: until its eventual downgrade, it was one of the very few U.S. companies to hold a AAA credit rating from Standard & Poor’s.

So here’s the question that drives this story: how did a 20-year-old accountant with a $2,000 startup turn into the backbone of American payroll?

The answer is more dramatic than it sounds. It’s a tale of early bets on automation, a Wall Street paperwork crisis that could have crushed the business (but instead supercharged it), a future U.S. senator who helped build the company, and a pair of spinoffs that trimmed a sprawling empire into a focused payroll-and-HR powerhouse. And through it all, ADP built one of the most durable moats in business services—not with patents or flashy breakthroughs, but with regulation, trust, switching costs, and the universal CFO nightmare of botching payroll.

It starts in postwar New Jersey, with two brothers—and a borrowed $2,000.

Origins: The Taub Brothers and Manual Payroll Processing (1949–1961)

In 1949, the American economy was surging. Factories were busy, suburbs were expanding, and small businesses were popping up all over northern New Jersey. But every new dry cleaner, trucking company, or machine shop ran into the same unglamorous reality: Friday was coming, and someone had to run payroll.

Back then, payroll wasn’t software. It was pencils, adding machines, and a stack of rules that seemed designed to punish mistakes—withholding tables, Social Security, state taxes, overtime. Many owners did it themselves, often poorly. Or they paid for a bookkeeper they could barely afford.

Henry Taub saw opportunity in that pain.

He’d graduated from New York University’s School of Commerce in 1947—still not yet 20 years old, and still more than a year away from even being eligible to sit for the CPA exam. Instead of waiting around, Taub borrowed $2,000 and, with his brother Joe, started a company in Paterson, New Jersey: Automatic Payrolls, Inc.

The name was more vision than description. There was nothing automatic about it. Henry and Joe were essentially an outsourced payroll desk, doing the work by hand for local businesses. Their pitch was simple and practical: give us the hours and the wages, and we’ll handle the calculations, the tax paperwork, and the checks—so you can run your business.

Those early years were pure grind. The Taubs had to sell something most small business owners didn’t think was a “service” at all. Payroll was what you did in-house, or what your spouse did at the kitchen table after dinner. Handing over employee pay information to an outside firm required trust—and trust took time. Henry obsessed over accuracy and process. Joe brought hustle and the willingness to knock on one more door.

In 1952, the business found the third piece it needed: Frank Lautenberg.

Lautenberg was a World War II veteran, a Columbia Business School graduate, and—most importantly—a natural salesman. Where the Taub brothers were careful operators, Lautenberg was a persuader. He brought structure to selling and ambition to marketing, pushing the idea that payroll processing could be a real standalone business—not just something accountants did on the side. Years later, he’d become ADP’s CEO and chairman, and later still a U.S. senator. But at this moment, he was the partner who could turn a quiet back-office service into something scalable.

Scale, however, didn’t come quickly. By the fiscal year ending June 1957, operating revenues had reached $150,000—respectable for a small service company. Profits were another story: $964 for the entire year. After nearly a decade, they had built a business that, on paper, barely made money.

But the numbers missed what mattered. They’d built a repeatable workflow, a base of recurring clients, and an intimate understanding of payroll’s one defining feature: it has to be right, every time.

That insight led to the most important decision of the era: stop treating payroll like paperwork, and start treating it like computation.

In 1957, the company renamed itself Automatic Data Processing, Inc.—a deliberate signal that Henry Taub planned to ride the wave of business computing. ADP began adopting punched card machines, check-printing equipment, and eventually mainframe computers. For a small company, these were serious bets. But Taub understood the core truth of the category: payroll is math, rules, and repetition. Computers were born for exactly that.

Automation changed the economics. With manual processing, every new client meant more hands. With machines, every new client could mean mostly more throughput.

By 1959, ADP pushed beyond payroll and set up a subsidiary, Automatic Tabulating Services, to sell general data processing work. It was an early attempt to squeeze more value out of expensive computing capacity—and a sign that ADP was starting to think like a technology company, not just a bookkeeping service.

The shift from pencils to punched cards to mainframes was bumpy and costly. But it set the trajectory. Taub wasn’t betting that people would be the moat. He was betting that systems would be. And the next chapter would put that bet to the test.

Going Public and Early Computer Adoption (1957–1970)

By the early 1960s, ADP hit the classic ceiling for a scrappy services business. It could keep growing, but not quickly—not without real capital. And in that era, “real capital” usually meant one thing: the public markets.

So in June 1961, ADP cleaned up its house. The payroll business and its data-processing sidecar were merged into a single entity under the Automatic Data Processing name, making the company easier to understand—and easier to sell—to outside investors. By then, ADP had built roughly 200 payroll clients, including one that feels like it belongs in a period film: the cast and crew of the Broadway production of My Fair Lady. Yes, the show that helped define the decade was getting its payroll run by a growing back-office shop in New Jersey.

The financials going into the IPO were humble. For the fiscal year ending June 1961, ADP posted $419,000 in revenue and $25,000 in net income, with about 125 employees. In September, it sold its first 100,000 shares to the public at $3 each, raising $300,000. No frenzy, no Wall Street spectacle—just a small company quietly stepping onto a much bigger stage.

What ADP had that many early “data processing” outfits didn’t was the pairing of Henry Taub’s operational rigor with Frank Lautenberg’s pure selling force. Lautenberg—by then the driving commercial engine and soon CEO—understood something fundamental about payroll: once you win the account, you tend to keep it. Switching payroll providers is miserable. Every employee record, withholding choice, tax detail, and garnishment has to be migrated perfectly, on a deadline, with zero room for error. Most companies would rather endure almost anything than risk a failed payday. That dynamic made payroll unusually sticky, and it gave ADP a base of recurring revenue long before “recurring revenue” was a Silicon Valley mantra.

In 1962, ADP made a move that would open up an entirely new lane. It set up an office on Wall Street to provide brokerage firms with payroll and basic accounting services. This was Taub’s instinct for adjacency: if you’re already trusted with money-sensitive work, why not take on more of it? Brokerage firms were buried in manual back-office operations—trade confirmations, settlement paperwork, recordkeeping—mountains of paper generated by every transaction. ADP saw an industry begging for automation.

The company’s ambitions weren’t confined to the U.S., either. In 1965, ADP established its first international subsidiary in the United Kingdom. That same year, it began to lean into acquisitions—small, practical additions that brought in clients and capability. And in 1967, ADP bought Computer Services of Florida, a Miami Beach-based firm. None of this was splashy. It was the early version of a strategy ADP would refine for decades: add clients, expand geography, plug them into a standardized operating system, and keep the revenue coming back every pay period.

By the late 1960s, the ADP playbook was already recognizable: sell a mission-critical service, automate the mechanics behind it, use acquisitions to compound the client base, and above all, never miss. Not on compliance. Not on taxes. Not on the paycheck.

The foundation was solid. But the next chapter would test it under real pressure—an oncoming Wall Street paperwork crisis that threatened to swallow the brokerage industry whole and, in the process, would make ADP’s reputation.

Wall Street Crisis and the Brokerage Business (1968–1985)

In 1968, Wall Street hit a problem that looked, at first, like success: trading volume surged. A late-’60s bull market pulled in waves of new investors, and suddenly the brokerage industry’s back offices were drowning. This was still a world of paper tickets, file cabinets, hand-written ledgers, and armies of clerks. More trades didn’t just mean more commissions. It meant exponentially more paperwork—and the machinery behind the scenes simply couldn’t keep up.

The result became known as the paperwork crisis, and it was brutal. Firms lost track of securities. Confirmations piled up. Trades sat unprocessed for weeks. The New York Stock Exchange even started closing on Wednesdays so firms could try to catch up. Some brokerages didn’t survive at all, crushed not by bad bets, but by operational collapse.

ADP walked into that chaos and did what it had quietly trained itself to do for two decades: make the messy, mission-critical work run on time.

While exchanges put dozens of firms “on restriction,” effectively warning them they could be shut down if they couldn’t clean up their books, ADP’s clients avoided that fate. ADP’s advantage wasn’t a glossy product demo. It was execution. The company’s “shirtsleeve approach,” as people described it at the time, meant ADP teams embedded with client back offices—processing, reconciling, and clearing the backlog shoulder to shoulder. It was grinding, detailed, deadline-driven work. But in a crisis like this, boring competence becomes the differentiator. When Wall Street couldn’t keep Wall Street running, ADP could.

Coming out of the paperwork crisis, ADP’s reputation changed. It wasn’t just the company that ran payroll accurately. It was the company you called when the consequences of failure were existential.

That set up the company’s “two-engine” growth through the 1970s: payroll for Main Street, back-office processing for Wall Street. In 1970, ADP’s stock moved from the American Stock Exchange to the New York Stock Exchange—a symbolic upgrade that reflected a very real one in market stature. Then ADP doubled down on technology. In 1974, it acquired Time Sharing Limited (TSL), an early online computer services company, and in 1975 it bought Cyphernetics. These weren’t trophy deals. They were capability deals—steps toward more interactive, on-demand computing, and away from the batch-processing world that defined early data services.

Overseeing much of this expansion was Frank Lautenberg, who had grown from the company’s early sales catalyst into chairman and CEO. He pushed relentlessly: new markets, new acquisitions, new systems. And then, in 1982, he did something almost no one expects from the head of a payroll-and-processing company: he left to run for the U.S. Senate from New Jersey. He won, beginning a political career that would last years and ultimately run until his death in 2013. The arc is remarkable, but it also says something important about ADP’s early leadership bench: this wasn’t a sleepy back-office vendor. It was a serious institution that created serious winners.

By 1985, ADP cleared another threshold: annual revenue topped $1 billion. At that point, the company was processing pay for about 20% of the U.S. workforce. That’s not a market position. That’s infrastructure. The moat wasn’t an abstract concept—it was embedded in how America paid its people.

Meanwhile, the brokerage operation had become enormous in its own right, handling trade processing, shareholder communications, and proxy services for major Wall Street firms. But success created a strategic tension that would only grow louder over time: was ADP, at its core, a payroll company with a powerful adjacent business? Or was it becoming a diversified processing conglomerate that happened to do payroll?

The company wouldn’t answer that question immediately. But the idea had been planted—and it would eventually lead to a spinoff.

The PEO Revolution and Expansion (1990s–2000s)

By the 1990s, payroll wasn’t the only thing keeping small and mid-sized business owners up at night. HR was turning into a regulatory minefield. The Americans with Disabilities Act. COBRA. HIPAA. The Family and Medical Leave Act. Each new rule wasn’t just another form to fill out—it was another way to get sued, fined, or blindsided by paperwork you didn’t even know you were supposed to have.

Into that mess stepped a new model: the Professional Employer Organization, or PEO. The pitch was almost audacious. In a co-employment arrangement, the PEO becomes the employer of record for tax and benefits purposes, while the client still runs the day-to-day work. The PEO takes over the heavy administrative lifting—payroll, benefits administration, workers’ compensation, and compliance. For a business that couldn’t justify a full HR team, it felt like renting an HR department instead of building one.

For ADP, this wasn’t a leap into the unknown. It was the next obvious rung on the ladder. If you’re already running the payroll, you’re already sitting at the center of the company’s employee data, deadlines, and legal risk. So why stop at cutting checks? Why not also manage the health plan, handle the workers’ comp claims, and file the taxes? ADP leaned in, making acquisitions in the PEO space and assembling what would become ADP TotalSource—eventually one of the largest PEOs in the United States.

The logic was as clean as the model was powerful. A PEO pools employees from hundreds or thousands of smaller companies into one large buying group. That scale can unlock better health insurance options, retirement programs, and workers’ compensation rates than most small businesses could ever negotiate on their own. The PEO earns fees for providing both that purchasing power and the administrative machine behind it. For ADP—already embedded in client workflows and already trusted with the most sensitive back-office function—PEO was less like starting a new business and more like adding a second floor to an existing building.

At the same time, ADP kept widening its geographic footprint. In 1995, it acquired Autonom in Germany and GSI in France. In 1998, it purchased the UK-based Chessington Computer Centre. The playbook was consistent: buy a local specialist to get on the ground fast, then bring it into ADP’s broader operating system. Payroll may be deeply local—every country has its own tax rules, labor laws, and banking rails—but the underlying mechanics are universal. ADP was positioning itself so multinational companies could manage payroll across many countries through a single provider.

The PEO business also introduced a financial tailwind that sat quietly in the background. As employer of record, ADP TotalSource collected funds for health insurance and workers’ compensation before paying them out to insurers and government agencies. That created float—money that temporarily sat on ADP’s balance sheet—and float generates interest income. As the PEO client base grew, so did that stream of interest revenue, an extra layer of economics that wasn’t obvious if you only thought of ADP as a “payroll company.”

By the end of the 2000s, ADP had evolved into something much bigger than payroll processing. It had become a broad human capital management provider—spanning basic paycheck calculation, benefits and retirement administration, HR outsourcing, and compliance support across more than a hundred countries. The same company that started by hand-calculating wages for small businesses in New Jersey was now the dominant global player in payroll and HR services.

But that success came with a cost: sprawl. And the next era of ADP’s story would be about focus—created not by adding, but by subtracting.

The Spinoff Era: Broadridge and CDK Global (2007–2014)

By the mid-2000s, ADP had a good problem with a bad side effect: it had become too many different things at once. Under one ticker lived three businesses that barely spoke the same language—employer services (payroll and HR), brokerage services (trade processing and investor communications), and dealer services (software and data systems for auto dealerships). They had different customers, different competitive arenas, and different needs for capital and investment. And the market did what the market usually does in that situation: it priced ADP like a conglomerate, valuing the whole at less than the parts.

The first big move came in March 2007. ADP spun out its Brokerage Service Group into a standalone public company: Broadridge Financial Solutions. It was a tax-free distribution, with each ADP shareholder receiving one Broadridge share for every four shares of ADP they owned, based on the March 23, 2007 record date. Broadridge began trading independently on March 30. Overnight, roughly $2 billion in annual revenue moved off ADP’s top line—and Wall Street could finally value the two businesses on their own terms.

Strategically, it was almost a confession. Brokerage services had been a defining growth engine since the 1960s, especially after the Wall Street paperwork crisis. But by 2007, it had matured into a highly specialized technology-and-communications platform for financial institutions. Its world revolved around broker-dealers, asset managers, and regulation-heavy infrastructure. That world had very little in common with getting 50 factory workers in Ohio paid correctly on Friday. With Broadridge on its own, ADP could say, credibly and simply: we are an employer services company.

Then ADP did it again.

In April 2014, the company began reshaping its Dealer Services unit. On April 7, ADP laid off several associates there as part of a reorganization. Three days later, it announced plans to separate the division entirely. The spinoff became CDK Global, which began trading on October 1, 2014. The name—CDK—came from Cobalt, Dealer Services, and Kerridge, three brands inside the unit. Like Broadridge, CDK was a solid business in a very specific niche: software, data, and marketing tools for car dealerships. And like Broadridge, it didn’t meaningfully reinforce ADP’s payroll-and-HR core.

The immediate reaction wasn’t universally glowing. In April 2014, both S&P and Moody’s downgraded ADP’s credit rating to AA, citing the loss of diversification. That downgrade mattered—ADP had long carried a AAA rating, a status so rare it functioned like a corporate Good Housekeeping seal. But the tradeoff was focus. With the dealer business gone, ADP could concentrate investment on employer services and PEO, pursue acquisitions that fit cleanly, and tell investors a clearer story.

Looking back, the spinoffs did what they were supposed to do. Broadridge went on to thrive as an independent leader in investor communications and proxy services. CDK built a strong position in automotive retail technology before being acquired by Brookfield Business Partners in 2022 for $8.3 billion. And ADP, slimmer and more coherent, was set up for the next wave: the shift from legacy processing to cloud-based HR technology that would reshape the entire category.

The lesson of this era is simple and surprisingly rare in corporate America: ADP got more valuable by getting smaller.

Modern ADP: Technology and Scale (2008–Present)

In October 2008, with the global financial system wobbling, ADP made a move that looked small on the surface but carried real signaling power: it switched its stock listing from the New York Stock Exchange to the NASDAQ Global Select Market. NASDAQ was where the market mentally filed “technology companies.” ADP wanted to be filed there too—not just as a payroll outsourcer, but as a scaled software-and-services platform that ran on technology.

The decade that followed was about dragging payroll out of the batch-processing era and into the cloud. The old world—mainframes, locked-down IT departments, and paper-heavy workflows—gave way to browser-based dashboards, mobile apps, and self-serve analytics. ADP poured investment into cloud platforms aimed at different customer segments: RUN for small businesses, Workforce Now for the mid-market, and Vantage HCM for large enterprises. More recently, it introduced Lyric, its next-generation HCM platform, which went on to win a 2026 Big Innovation Award from the Business Intelligence Group.

Acquisitions evolved right alongside the product strategy. Earlier deals had often been about entering a new geography or picking up a book of business. Now, they were increasingly about capability—buying specific tools that made the platform stronger. In 2018, ADP acquired WorkMarket, a freelance management platform built for the growing gig economy. In 2023, it bought Sora, a workflow automation tool aimed at streamlining HR processes. The biggest recent step came in October 2024, when ADP acquired WorkForce Software for $1.2 billion. WorkForce specialized in time and attendance, scheduling, forecasting, and leave management for large global enterprises—exactly the kind of “deep operations” functionality that keeps big customers from ever wanting to switch vendors. By November 2025, ADP launched the ADP Workforce Suite, integrating WorkForce Software’s technology across its broader HCM offerings. And in January 2026, ADP acquired Pequity, a compensation management platform—another sign that the company still prefers targeted bolt-ons over sprawling reinvention.

Structurally, modern ADP runs through two main segments. Employer Services is the core: payroll, tax filing, benefits administration, talent tools, and compliance services for companies of virtually every size. PEO Services—branded as ADP TotalSource—offers full HR outsourcing through the co-employment model. Together, those businesses serve more than one million clients across 140 countries.

The scale is hard to overstate. ADP processes payroll for roughly one in six American private-sector workers. And it doesn’t just report on the economy—it’s become part of the way the market understands it. ADP’s National Employment Report, produced in collaboration with the Stanford Digital Economy Lab, is published monthly the day before the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases its official jobs report. In 2022, ADP revamped the report’s methodology, moving away from a model built to anticipate the BLS and toward a direct read based on ADP’s own anonymized payroll data covering more than 26 million employees. The company later added a weekly employment tracker for near-real-time insight into private-sector labor trends. When ADP talks, investors pay attention—not because ADP is trying to be the government, but because it’s sitting on an enormous, timely dataset that’s difficult to replicate.

Financially, the machine keeps doing what machines like this do: compounding steadily. In Q2 of fiscal 2026, reported on January 28, 2026, ADP posted $5.4 billion in revenue, up 6.2% year over year, and earnings per share of $2.62, beating consensus estimates. Adjusted EBIT rose 10% to $1.4 billion, and margin expanded by 80 basis points to 26%. The company also pointed to a notable international win—a European bank with 75,000 employees—an example of where incremental growth can still be very large outside the U.S.

For fiscal 2026, management guided to about 6% revenue growth and 9% to 10% adjusted EPS growth, along with 50 to 70 basis points of margin expansion. Pricing remained steady, contributing about 100 basis points—slightly lower than fiscal 2025, but still well above pre-pandemic norms.

In 2026, Fortune named ADP one of the world’s most admired companies for the twentieth consecutive year. In a category where the worst-case scenario is a missed payday, “admired” isn’t about being flashy. It’s about being trusted. And ADP’s modern story—cloud platforms, capability acquisitions, global scale—still cashes out in the same simplest promise it started with back in New Jersey: payday happens, correctly, every time.

Business Model Deep Dive

To understand why ADP is so difficult to displace, you have to look past the brand and into the machinery: how the company gets paid, what it actually does every day, and why customers stick around even when a competitor offers a cheaper quote.

Employer Services is the bigger of ADP’s two segments and the heart of the business. It’s software plus service, wrapped around the most unforgiving deadline in corporate America: payday. ADP’s cloud platforms handle the full chain—calculating payroll, withholding taxes, running direct deposit, issuing W-2s, administering benefits, tracking time, supporting recruiting and talent tools, and keeping clients onside with regulators. The customer base spans the spectrum, from a five-person shop on RUN to global enterprises running systems like Workforce Now or the enterprise-grade Lyric platform. The pricing generally looks like a subscription: you pay for the platform, and the fee scales with headcount and complexity. For a small business, that might be a few hundred dollars a month. For a large enterprise, it can run into the millions a year.

But the most elegant part of ADP’s economics isn’t the subscription fee. It’s what happens around the paycheck.

When ADP runs payroll, it typically pulls the money from the employer a few days before pay day, then sends it out to employees and tax authorities on schedule. In that in-between window, the funds sit with ADP. This is client fund float, and it’s a quiet but powerful engine in the model. In Q2 fiscal 2026, ADP reported an average client fund balance of $37.6 billion. With an average interest yield of 3.3%, that produced $309 million of interest income in the quarter. The direction of interest rates matters—a rising-rate environment is a tailwind, a falling-rate environment is a headwind—but the underlying reality doesn’t change: payroll keeps running, and the float keeps existing.

Tax filing and compliance adds another layer of stickiness and scale advantage. ADP files payroll taxes for clients across federal, state, and local authorities. In the U.S., that means navigating thousands of tax jurisdictions, each with its own rules, deadlines, and quirks. For most companies, keeping up is painful and risky. For ADP, it’s part of the operating system. The work is expensive to build once, but cheap to spread across a massive client base—exactly the kind of scale dynamic that turns compliance into a moat.

PEO Services (TotalSource) is where ADP becomes more than a vendor. In the PEO model, ADP TotalSource acts as the employer of record for tax and benefits purposes, while the client still manages day-to-day work. ADP takes on payroll, benefits, workers’ compensation, and compliance. As of recent disclosures, the PEO business had access to the buying power of 722,000 worksite employees. That scale gives it real leverage with insurers and workers’ comp providers, and it’s the basis of the “join us and get big-company benefits” pitch. In a recent quarter, the PEO segment’s revenue grew 11% year over year to $487 million, reflecting sustained demand for full-service HR outsourcing among small and mid-sized businesses.

Then there’s the real trapdoor in the model: switching costs.

Changing payroll providers sounds like a procurement project. In reality, it’s a high-stakes data migration with reputational risk attached. You’re moving every employee’s tax setup, direct deposit details, benefits elections, historical pay records, and compliance configurations. You’re retraining HR, rebuilding integrations to accounting and time systems, and running parallel processes to make sure the new engine doesn’t misfire. And if you’re a PEO client, it’s even harder: you’re not just swapping software, you’re changing the employer of record and potentially disrupting benefits coverage. That combination—complexity plus fear of errors—creates unusually strong retention and makes ADP’s revenue base remarkably predictable.

Finally, ADP benefits from network effects, just not the loud, viral kind you see in consumer tech. As ADP processes more employees, its aggregate labor market dataset gets richer. That data underpins products like the National Employment Report, which strengthens ADP’s credibility, which helps win more clients, which generates more data. And on the PEO side, every added client increases the buying pool, improving negotiating leverage and strengthening the value proposition for the next client. It’s a flywheel built out of scale, trust, and the simple reality that nobody wants to gamble with payroll.

Financial Performance and Market Position

ADP’s recent financial record reads like the kind of compounding investors love and everyone else ignores. Over fiscal 2023 through 2025, revenue stepped up from $18.0 billion to $19.2 billion, then to $20.6 billion. Not explosive growth—just the steady, repeatable kind you get when your product is both recurring and mission-critical. The drivers are straightforward: keep winning new clients, sell more services into the existing base, and apply price increases where the value is obvious.

What’s more interesting is how that growth translates into profit. In Q3 fiscal 2024, ADP posted $5.3 billion in revenue and $1.2 billion in net income, up 14% year over year. Earnings per share rose 15% to $2.88, and adjusted EBIT increased 12% to $1.5 billion. This is what operating leverage looks like in a platform business: once the core systems and compliance engine are in place, each incremental client—and each additional module a client adopts—tends to drop through at attractive margins.

And those margins have been inching higher. Adjusted EBIT margin expanded by 80 basis points in the most recent quarter to 26%, and management guided for another 50 to 70 basis points of expansion in fiscal 2026. In other words, ADP isn’t just getting bigger; it’s getting more efficient at delivering what it sells.

Then there’s the earnings lever that doesn’t look like software at all: interest on client funds. Because ADP pulls money from employers before distributing it to employees and tax authorities, it sits on a massive pool of client funds in the meantime. With $37.6 billion in average client fund balances and a 3.3% yield, that float produces well over a billion dollars a year in interest income. It’s a powerful revenue stream that doesn’t require extra sales, marketing, or implementation work—just the continued, relentless rhythm of payroll. The catch is that it’s rate-sensitive, which makes ADP a little unusual: Federal Reserve policy can show up in its earnings in a way most “HR tech” companies never experience.

Competitive dynamics are where ADP’s scale becomes the story. Paychex is the clearest peer in small business payroll—strong operator, similar category, but roughly half ADP’s revenue scale. In large-enterprise HCM, Workday is a serious cloud-native competitor for organizations doing full HR system overhauls. UKG is a major force in workforce management and service delivery. Paycom and Paylocity have built modern, all-in-one offerings aimed squarely at the mid-market. But none of them spans ADP’s full map: small business to global enterprise, payroll to PEO, domestic to international. ADP is one of the few vendors that can plausibly serve a ten-person company and a 100,000-employee multinational without forcing them into completely different universes.

ADP also has a differentiator that competitors can’t easily copy: it’s become a trusted public read on the private-sector labor market. The ADP National Employment Report is cited every month precisely because it’s not a survey or a model—it’s grounded in real payroll data at enormous scale. That creates a subtle advantage. It sharpens ADP’s view of employment trends, adds credibility in client conversations, and delivers brand exposure money can’t buy when financial news anchors repeat the ADP number as a key economic signal.

As of late January 2026, ADP traded around $248 per share, with a market cap near $100 billion—down from a 52-week high of $330. The stock carried a P/E around 24 and a dividend yield of roughly 2.5%. The decline reflected macro anxiety—cooling employment growth and a broader rotation away from defensive names—but the underlying business kept doing what it has done for decades: show up on time, execute reliably, and compound.

Playbook: Strategic and Investing Lessons

ADP’s 76-year run isn’t a story of one brilliant invention. It’s a story of a playbook—repeated, refined, and scaled until it became infrastructure. Here are the lessons that show up again and again for operators and investors.

The power of mission-critical, recurring revenue. Payroll is non-negotiable. If you have employees, you have to pay them—on time, every pay period, with the right withholdings—or the consequences are immediate: angry staff, regulatory penalties, and legal risk. That makes ADP’s revenue unusually durable. In a recession, companies may shrink headcount, which trims per-employee fees, but they don’t “pause payroll.” The service stays essential, which makes the business far more resilient than most enterprise software.

Regulatory complexity as a competitive moat. U.S. payroll sits inside a labyrinth of federal, state, and local tax rules—thousands of jurisdictions, constant changes, and zero tolerance for mistakes. For a single employer, keeping up is a burden. For ADP, it’s the job. Scale turns compliance into an advantage: the cost of building the rules engine is high once, but cheap to spread across a massive client base. And every new regulation, ironically, strengthens the case for outsourcing. It’s one of the few moats that deepens every time lawmakers add complexity.

Strategic use of acquisitions. Over the years, ADP has done more than twenty acquisitions, averaging about $213 million per deal. The pattern is disciplined: buy capabilities or geographic reach, integrate into the platform, then sell those new capabilities across the existing customer base. The WorkForce Software deal is a clean example. ADP saw a gap in enterprise workforce management, acquired a specialist, and shipped an integrated offering within about a year.

The discipline of spinoffs. Broadridge and CDK Global weren’t failures—they were good businesses that didn’t fit. By spinning them off, ADP chose focus over diversification. Both companies went on to succeed independently, and ADP ended up with a clearer identity, cleaner economics, and more concentrated investment in payroll, HR, and PEO. The takeaway is simple: if a unit has different customers, different competitive dynamics, and different growth drivers, it may be worth more on its own than trapped inside a conglomerate.

Capital allocation discipline. ADP has paired steady dividends with consistent buybacks and selective M&A. It’s a Dividend Aristocrat with decades of consecutive dividend increases, and it has generally avoided the classic mature-company traps: overpaying for acquisitions or chasing growth for growth’s sake. The result is a company that throws off significant free cash flow—and returns a meaningful share of it to shareholders.

Building trust through reliability. Payroll is a trust business. One mistake can mean someone can’t pay rent, and the employer blames the vendor. ADP’s brand is built on decades of doing the unglamorous work correctly, over and over again. That reputation is hard to copy and, as long as execution stays tight, even harder to dislodge.

Analysis and Investment Case

Bull Case

If you like businesses with real moats—not vibes—ADP has them. A lot of them.

Start with scale economies. Payroll is brutally fixed-cost heavy: compliance engines, tax tables, integrations, security, uptime, customer service, and benefits administration infrastructure. ADP spreads those costs across more than a million clients. That’s why it can keep investing in the platform and still expand margins.

Then there are switching costs, which in payroll are as close to “don’t try this at home” as enterprise software gets. Moving providers means migrating every employee record, every withholding choice, every garnishment, every tax jurisdiction setup, and every integration to timekeeping and accounting—while still paying everyone correctly, on time, during the cutover. Even when a competitor is cheaper, the fear of a broken payday is often enough to keep customers put.

ADP also benefits from network economies, just not the social-media kind. More clients means more payroll data, which strengthens products and insights. And on the PEO side, more pooled employees means more buying power on benefits and workers’ comp—improving the offer and helping win the next client. Finally, there’s process power: decades of institutional muscle memory in how to run payroll at scale without interruption. That sounds unsexy, but it’s exactly what mission-critical infrastructure is made of.

Porter’s Five Forces tells a similar story. The threat of new entrants is capped by regulation, trust, and the sheer operational burden of getting payroll right across thousands of jurisdictions. Buyer power is diluted—most customers are small and mid-sized businesses without the leverage (or appetite) to squeeze a vendor that can easily out-execute them. Supplier power is limited because ADP’s main inputs are labor and technology. Substitutes are scarce: every employer must run payroll, and building it in-house is expensive, risky, and distracting. Rivalry exists, but it’s typically fought on product depth, service quality, and reliability—not on suicidal price cuts.

And the macro winds are generally at ADP’s back. Regulations keep multiplying. Remote and hybrid work makes multi-state and multi-country payroll table stakes. The gig economy adds new kinds of workers to manage and pay. And the PEO model keeps gaining share as small businesses decide they’d rather outsource HR complexity than hire into it.

Underneath all of that is the financial engine. ADP generates substantial free cash flow, which funds dividends, buybacks, and targeted acquisitions without needing to lean on outside capital. And then there’s the client fund float—an “invisible” profit center that scales naturally with the base business and becomes especially powerful when interest rates cooperate.

Bear Case

The biggest risk is that payroll, especially in the U.S., is a mature category. There’s only so much greenfield left. That means growth increasingly has to come from expanding internationally and selling more products into existing clients—harder work than winning a brand-new payroll account in a fast-growing market.

Competition is also getting sharper. Workday, Paycom, Paylocity, Rippling, and Gusto are pushing modern, cloud-first experiences across different segments of ADP’s customer base. ADP has invested heavily in its own cloud platforms, but it also carries the baggage of decades of legacy architecture and operating complexity. Modernizing at ADP’s scale is possible—but it’s never quick, and it’s never cheap.

AI is the wild card. It cuts both ways. ADP is building AI-driven features like smarter compliance monitoring and workforce analytics. But if AI meaningfully reduces the “pain” of payroll and compliance—by automating what used to require expertise and headcount—it could weaken one of ADP’s oldest moats. In that world, a new generation of software-first players might deliver “good enough” payroll at lower cost.

ADP is also economically sensitive in a straightforward way: fewer employed people means fewer paychecks processed, and in a deep downturn PEO enrollment can compress. The counterpoint is that payroll doesn’t go away in a recession—it just shrinks. And the pandemic showed that even a dramatic shock can be temporary, with revenue rebounding as hiring returns.

Finally, there’s valuation. At around 24 times earnings, the market treats ADP like a premium compounder. That leaves less room for disappointment. If growth slows, margins stall, or retention softens, the multiple can compress—even if the business remains fundamentally strong.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

For investors trying to track whether the ADP machine is getting stronger or starting to leak, two metrics matter most:

-

Client retention rate (Employer Services). This is the cleanest read on moat health. ADP’s retention has historically sat in the low-to-mid 90s. A meaningful, sustained drop would suggest competitive pressure, execution issues, or both.

-

PEO worksite employee growth. PEO is one of ADP’s most important growth engines. The worksite employee count shows whether the co-employment model is gaining traction and whether ADP is successfully moving customers from “payroll vendor” to “outsourced HR partner.”

Future Outlook and Key Questions

ADP entered 2026 with real momentum—and an equally real set of open questions. The biggest one sits at the center of almost every enterprise roadmap right now: AI.

Management had been clear that AI, and especially generative AI, would increasingly shape the product. The near-term targets were practical and high-value: smarter compliance monitoring, faster employee self-service, and better workforce analytics. The tension is obvious. Startups are building AI-native HR tools from day one, without decades of legacy systems to modernize. ADP’s bet is that what looks like “legacy” is also an advantage: scale, distribution, and a dataset that’s hard for anyone else to match. The question is whether ADP can translate those advantages into shipping velocity—and stay ahead as expectations reset for what “good software” should feel like.

International expansion is the other major lever. ADP already operated across more than 140 countries, but penetration and product depth varied widely by market. The recent win of a European bank with 75,000 employees is a great example of the prize: a single multinational account can be enormous. But global payroll is where the industry stops being “complex” and starts being punishing—local tax rules, labor laws, and reporting requirements that differ not just country to country, but sometimes region to region. And unlike the U.S., the competitive map changes everywhere you go.

More acquisitions also seemed likely. The January 2026 purchase of Pequity signaled that ADP was still playing the same disciplined game: tuck in a specialized capability, integrate it, and then scale it through the broader platform. Compensation management is one piece of that puzzle, but it points toward a broader direction—benefits navigation, analytics, and automation that makes HR feel less like paperwork and more like a control system.

Over it all hangs the biggest macro variable: the future of work. Remote work, gig and contractor labor, cross-border hiring, reclassification risk, and constantly evolving regulation all push companies toward outsourced expertise. In ADP’s world, every new rule and every new edge case is both a burden and an opportunity. Complexity is the product.

And that’s the enduring punchline of the ADP story. The company Henry Taub started in 1949 with $2,000 now touches the pay of roughly one in six American workers and generates more than $20 billion a year. Its moat isn’t a patent portfolio or a single breakthrough feature. It’s the unglamorous truth that payroll is hard, compliance is harder, and most businesses would rather pay a trusted specialist than risk getting either one wrong. As long as that stays true, ADP keeps collecting its toll.

Recent News

ADP opened 2026 by reminding investors what it does best: steady, deadline-driven execution. On January 28, 2026, it reported Q2 fiscal 2026 results, with revenue of $5.4 billion, up 6.2% year over year, and adjusted EPS of $2.62, up 11.5%. Management raised full-year guidance, now calling for about 6% revenue growth and 9% to 10% adjusted EPS growth. Interest income on client funds rose 13% to $309 million, helped by higher balances and better yields, while adjusted EBIT margin expanded 80 basis points to 26%.

On the product front, ADP kept folding recent acquisitions into a tighter platform story. In November 2025, it launched the ADP Workforce Suite, an integrated workforce management offering built on the WorkForce Software acquisition completed in October 2024. The suite brings time and attendance, scheduling, leave management, and employee communications together across ADP’s HCM platforms.

In January 2026, ADP acquired Pequity, a compensation management platform, adding data-driven tools for compensation planning. Around the same time, ADP announced an embedded integration of Thatch’s ICHRA (Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangement) platform into RUN Powered by ADP, giving small-business customers a more direct path into the growing ICHRA market.

Meanwhile, ADP’s role as an economic bellwether continued to draw attention. Its National Employment Report for December 2025 showed private-sector employment rising by 41,000 jobs, following a revised decline of 29,000 in November. The report emphasized that job creation was essentially flat in the back half of 2025 and that pay growth was trending downward.

In the market, the stock reflected those softer labor signals. ADP traded near 52-week lows, roughly in the $247 to $260 range, down from a 2025 high near $330. Morgan Stanley lowered its price target to $274 from $311 while keeping an Equal Weight rating.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music