Incyte: The Phoenix of Delaware

I. Introduction & The "Hook"

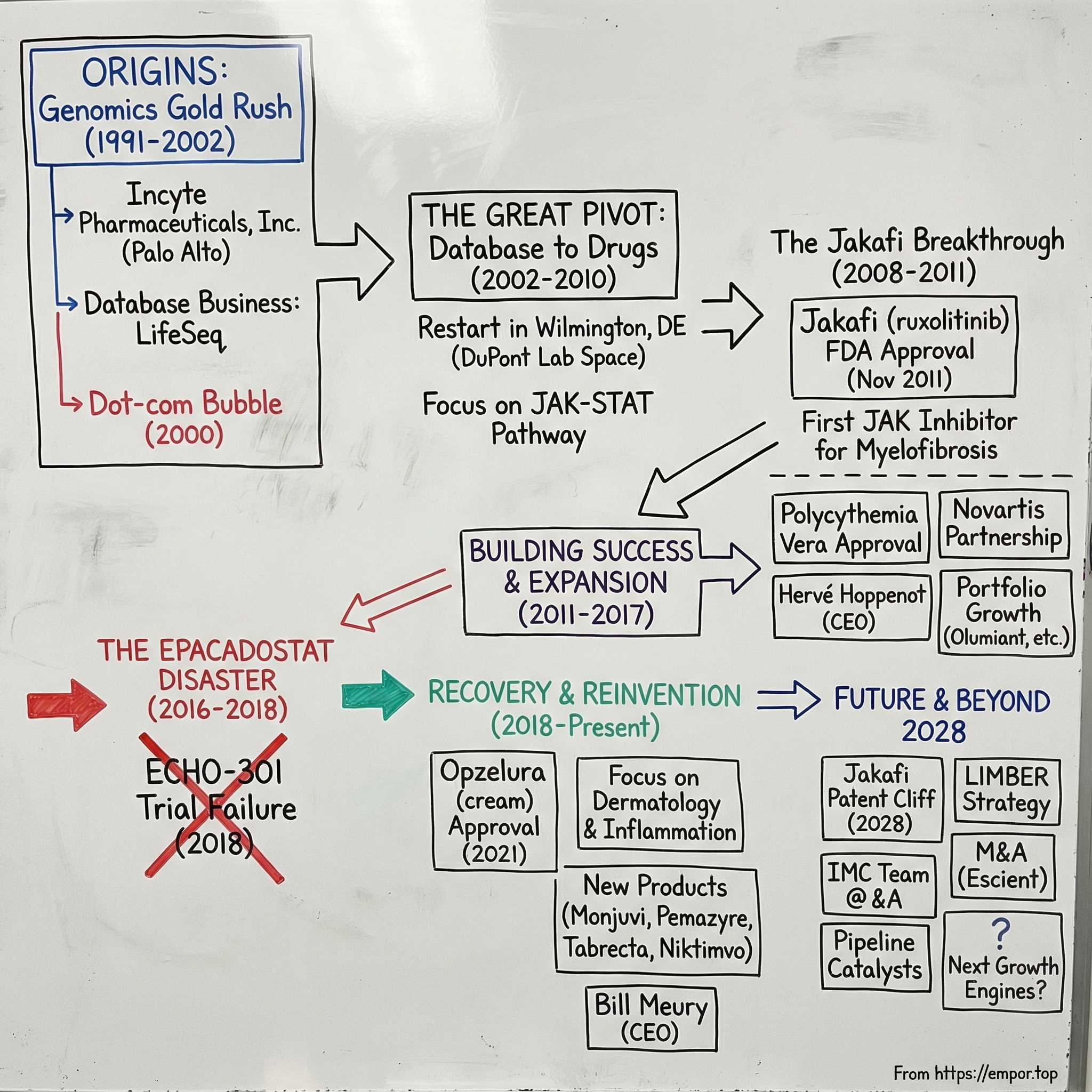

Late 2001. Incyte Genomics is sitting in Palo Alto, watching the floor drop out from under it.

For most of the late ’90s, the pitch was intoxicating: Incyte wasn’t making drugs, it was selling the future. A massive genetic database—subscription access for Big Pharma—positioned as “the Gray’s Anatomy of the 21st century.” If you were building medicine, Incyte would sell you the map.

Then the world changed. As the public Human Genome Project wrapped up in the early 2000s, genomic data stopped being scarce. And when the thing you sell goes from rare to everywhere, the price doesn’t gently decline. It collapses. Practically overnight, Incyte was left holding an enormously expensive asset that fewer and fewer customers wanted to pay for.

What happened next is the opposite of the standard Silicon Valley recovery story.

In 2002, Incyte did something almost unthinkable for a Bay Area genomics company: it left. The company packed up and moved across the country to Wilmington, Delaware—and with that move, it rebuilt itself from the inside out. No “adjacent market” strategy. No quick iteration. No growth hacks. Instead: chemists. Lots of chemists. A full cultural reset—from the land of “move fast and break things” to the DuPont legacy of deep, slow, rigorous chemistry.

Fast forward to today, and Incyte is one of modern biotech’s most improbable reinventions. In 2024, the company generated $4.2 billion in total revenue, up 15% year over year, powered by growth from its key products, including Jakafi and Opzelura. Jakafi, in particular, became the first and only FDA-approved treatment for myelofibrosis—and the first JAK inhibitor approved for any indication.

But this isn’t a straight shot from failure to glory. It’s a story about survival, reinvention, and getting humbled in public. In 2018, Incyte’s ECHO-301 trial failed, and the market reaction was immediate and brutal—more than a 20% drop in a single morning and billions in value wiped away.

Now the clock is ticking again. With Jakafi’s patent cliff approaching in 2028, Incyte is racing toward what you might call its Third Act: proving it can become more than “the Jakafi company” before generics arrive.

Incyte matters right now because it cuts against the fantasy version of biotech—the one where breakthroughs arrive on schedule and hype turns into revenue. This is the other version: the decades-long grind of real drug development, where being right about the science is only part of the job. The rest is surviving long enough for the science to matter.

II. Origins: The Genomic Gold Rush (1991–2001)

To understand Incyte, you have to go back to the biotech fever dream of the 1990s. The Human Genome Project was underway, and the mood in the industry was simple: once we had the full map of human DNA, we’d crack the code of disease. Whoever controlled the data would control the future.

Incyte started right in the middle of that optimism. The company was incorporated in April 1991 under the name Incyte Pharmaceuticals. It was created by Schroder Venture Advisers, a New York venture capital firm, to acquire assets and technology from a St. Louis biotech company called Invitron, which was in liquidation. Even the name was a time capsule: Incyte, a mash-up of “information” and “cybernetics,” basically announcing, from day one, that this was going to be an information company in a biology world.

And that’s exactly what the founders built. Roy A. Whitfield and Randy Scott weren’t trying to invent medicines. They were trying to industrialize gene discovery and package it into something pharma could buy: a massive proprietary genomic database. Think of it as a Bloomberg Terminal for DNA—Big Pharma pays a subscription, logs in, and uses the data to find drug targets faster than their competitors.

Wall Street loved the premise. Incyte became the first genome science company to go public, debuting on November 4, 1993. It sold 2.3 million shares at $7.50 on the American Stock Exchange under the ticker IPI, raising about $17.25 million to pour gasoline on gene discovery and data commercialization.

For a while, the model didn’t just work—it worked spectacularly. Incyte sold annual subscriptions to its database and analytics tools, including access to a product called LifeSeq. Pfizer became its first major subscriber in June 1994, signing a deal valued at $24.8 million. More subscribers followed, and the database itself ballooned. LifeSeq Gold eventually contained transcripts of 120,000 genes, with more than half of them proprietary—meaning, if you wanted that information, you got it from Incyte or you didn’t get it at all. By 2000, more than 20 of the world’s top pharmaceutical companies were paying to be inside the tent.

This was the rarest thing in genomics at the time: a company with real revenue. For eight quarters in 1997 and 1998, Incyte was even profitable. Subscriptions drove most of the business, and at its peak the licensing model generated over $100 million a year.

Then the ground shifted.

The late ’90s weren’t just the era of the Human Genome Project—they were the era of the sequencing arms race. Celera Genomics, led by Craig Venter, went head-to-head with the publicly funded effort and promised to finish faster. The competition made the genome feel like a prize, and everyone chased it as if the finish line would make them rich.

But for Incyte, the finish line was the nightmare scenario.

The closer the world got to a completed human genome, the more inevitable it became that the data—Incyte’s core product—would stop being scarce. Public databases like the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s GenBank kept getting better. More information moved into the open. And once the same raw material could be had for free, it didn’t matter how elegantly you packaged it. Demand started to slip.

Incyte tried to fight the commoditization by spending more—more equipment, more gene hunting, more effort to stay ahead. Financially, the stress showed. The company posted a net loss of $26.8 million in 1999 on $157 million in revenue, with about 80% still coming from database subscriptions. After 1998, profits faded as investment ramped and the business began searching—quietly at first—for what it might become next.

By the third quarter of 2001, Incyte announced plans for a major restructuring. The subscription model that had powered the company was now on life support.

And yet, Incyte wasn’t broke. It still had roughly $500 million in cash—money banked during the genomics boom. What it didn’t have was a clear future.

It’s a brutal lesson about information businesses: a “moat” made of proprietary data can look unassailable, right up until the moment the world decides that information should be ubiquitous. When your advantage is access, you’re always one shift away from being copied, undercut, or simply made irrelevant.

Incyte had survived the gold rush. Now it had to figure out how not to become one of its casualties.

III. The Great Pivot: From Silicon Valley to Chemical Valley (2002)

The rescue didn’t come from another genomics startup. It came from DuPont—about as far culturally from Palo Alto as you can get.

On November 26, 2001, Incyte Genomics named Paul A. Friedman, M.D., its new CEO. Friedman had been President of DuPont Pharmaceuticals Research Laboratories. Alongside him, Incyte brought in Robert Stein, M.D., Ph.D., formerly DuPont Pharmaceuticals’ Executive Vice President of Research and Preclinical Development, as President and Chief Scientific Officer—tasked with overseeing both the legacy database business and the new therapeutic ambitions.

The timing wasn’t accidental. Just two months earlier, in September 2001, Bristol Myers Squibb acquired DuPont Pharmaceuticals for $7.8 billion. That deal didn’t just shuffle logos on buildings—it suddenly freed up a deep bench of veteran drug hunters. And Incyte, sitting on roughly $500 million in cash but staring at a collapsing genomics subscription model, was exactly the kind of platform that could absorb them.

Friedman’s résumé fit the moment. At DuPont, the number of drug candidate compounds nominated for clinical development tripled, reaching 10 in 2000. One of the notable successes from that era was Sustiva, which became a leading medicine for HIV. Before DuPont, Friedman had been Senior Vice President of Research at Merck, and earlier still, an Associate Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology at Harvard Medical School. This wasn’t a “let’s try something new” hire. This was a “we’re betting the company on becoming a real pharma company” hire.

That was the mandate. As Friedman later put it, the board had concluded Incyte wasn’t going to thrive as a tools company. They needed leadership that knew how to discover and develop drugs.

And in Friedman’s view, Incyte had the raw materials to attempt it. In another interview, he explained what made Incyte stand out: it had money in the bank, a huge genomic database, and what he described as the largest intellectual property portfolio among its peers. The data business was dying, but the company still owned a lot of valuable science—and it had enough cash to try a second life.

The headquarters move made the pivot real.

Incyte didn’t just hire DuPont people. It went to DuPont’s backyard. The company set up operations at the DuPont Stine Haskell research facility, renting office space and plugging directly into the local talent pool. Delaware also brought a business-friendly legal environment. But more than anything, the move was a statement: Incyte was leaving Silicon Valley’s “information is the product” mindset and stepping into a world where the product is a molecule, and progress is measured in experiments, not iterations.

Friedman framed the logic as unification—bringing the genomic and proteomic information business, the intellectual property, and a fast-growing drug discovery organization under one Incyte name. The subtext was clearer: the database would stop being the business. It would become an input.

Incyte started putting its new strategy into action quickly. It launched a fully staffed drug discovery program focused on orally active small molecules designed to block the interaction of a specific chemokine with its receptor—an approach aimed at chronic inflammation conditions like rheumatoid arthritis. Around the same time, Incyte announced an agreement to acquire Maxia Pharmaceuticals, a privately held small-molecule drug discovery company in San Diego.

The Maxia deal, completed in 2003 for $42 million, was small by Big Pharma standards—but it mattered. It added chemistry expertise and early drug leads in diabetes, inflammation, and cancer. In other words: more shots on goal, built for the kind of company Incyte was trying to become.

Of course, a pivot like this isn’t a press release. It’s a demolition and rebuild.

Incyte restructured hard. The company’s center of gravity shifted from selling information externally to building medicines internally. That meant layoffs—hundreds of software engineers and bioinformatics specialists were let go. In their place came medicinal chemists, pharmacologists, and clinical development experts. The skill set changed. The cadence changed. The whole definition of success changed.

Friedman would stay in the CEO seat from 2001 to 2014, overseeing the long transformation from a genomics-era data company into a therapeutics company—one that would eventually build a foundation in oncology.

But the most remarkable part of this pivot is not that it happened. It’s what it demanded: intellectual humility and time.

Incyte had been built on the belief that software, data, and algorithms could revolutionize medicine. Now it was committing to something older and less forgiving: chemistry and clinical trials. The genomics assets didn’t disappear, but they were demoted—from product to tool.

And then came the wait. This wasn’t a feature release cycle. From the 2002 pivot to the 2011 approval of Jakafi, nearly a decade would pass. Anyone buying into “New Incyte” had to accept the core reality of biotech: you can do everything right and still not know for years whether the bet worked.

IV. Finding the "Holy Grail": The Discovery of Jakafi (2003–2011)

After the Delaware reset, Incyte needed a target big enough to justify the pivot—and real enough to survive the grind of drug development. They found it in a family of enzymes called Janus kinases, or JAKs. Incyte’s early JAK inhibitor work began around 2003, and the bet was simple to state but hard to prove: if you could safely tune down JAK signaling in humans, you might be able to treat serious diseases driven by immune and inflammatory overactivation.

Here’s the quick mental model. Cytokines are the body’s alarm signals—chemical messages that flare when you’re fighting infection, dealing with inflammation, or responding to cancer. JAKs sit inside the cell as key relays for those signals. When cytokines hit the cell surface, JAKs help pass the message along through the JAK-STAT pathway into the nucleus, switching genes on and off. The JAK family includes JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2, and together they influence a huge range of immune and inflammatory behavior.

In a healthy body, that alarm system turns on, does its job, and then quiets down. In certain diseases, it doesn’t. The signal gets stuck on “loud,” and the result is chronic inflammation, immune dysfunction, and tissue damage. A JAK inhibitor, in that framing, isn’t a sledgehammer. It’s the volume knob—turning down overactive cytokine signaling by suppressing the intracellular relay.

The “holy grail” indication that made the promise tangible was myelofibrosis, a rare and brutal blood cancer within a broader category called BCR-ABL1–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. These diseases involve abnormal clonal growth of blood-forming stem cells and can lead to complications like thrombosis, bleeding, and progression to acute leukemia. Myelofibrosis patients often suffer from progressive splenomegaly—an enlarged spleen—and a punishing symptom burden: fatigue, itching, bone pain, and more.

Then came the key scientific unlock: researchers discovered an activating mutation in the JAK2 gene. Suddenly, the biology wasn’t just “inflammation is complicated.” There was a specific signaling pathway that looked like it was jammed open. And if JAK2 was part of the problem, then inhibiting JAK signaling could plausibly address both the underlying disease behavior and the symptoms that were wrecking patients’ lives.

Incyte’s team developed ruxolitinib—first known as INCB18424—a potent inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2, and the first drug in its class to enter clinical trials. Early results were encouraging. Patients saw reductions in spleen size, and many reported meaningful symptom improvement—exactly the kind of real-world benefit that makes an experimental mechanism start to feel like a medicine.

But there was a problem. Clinical trials are expensive, and by 2009, Incyte was running low on runway. The company had made it through the pivot; now it faced the classic biotech moment where the science might be right, but the balance sheet might not be.

So Incyte made a deal that would define the company’s economics for years.

In November 2009, Incyte signed a Collaboration and License Agreement with Novartis. Novartis received exclusive rights to develop and commercialize ruxolitinib outside the United States for hematologic and oncology indications, along with certain back-up compounds. Incyte kept exclusive U.S. rights—meaning it would build its commercial future around the American market, while a pharma giant took the rest of the world.

The deal brought immediate oxygen: an upfront and immediate milestone payment totaling $210 million, plus eligibility for additional milestone payments that could reach roughly $1.1 billion.

This is the kind of trade biotech CEOs replay in their heads for the rest of their careers. The Novartis partnership gave Incyte the resources to finish the pivotal trials and push ruxolitinib across the finish line. But it also meant giving up a massive portion of the upside—forever.

You can see the counterfactual in the later numbers. In a recent fiscal year, Incyte reported $2.7 billion in Jakafi sales, plus $418 million in royalty revenue. Novartis, selling ruxolitinib outside the U.S., recorded $1.9 billion in annual sales. If Incyte had somehow held worldwide rights, you can do the mental math: the drug’s global annual revenue would be far larger on Incyte’s income statement. But “somehow” is doing a lot of work in that sentence. Without Novartis’s capital and global execution, ruxolitinib’s story might have ended as a promising compound that never became a product.

Two years later, Incyte got the moment it had been building toward since the move to Delaware.

On November 16, 2011, the FDA granted full approval to ruxolitinib (Jakafi) for intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis, including primary myelofibrosis, post–polycythemia vera myelofibrosis, and post–essential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis.

It was a milestone for patients and a turning point for the industry: the first drug ever approved for myelofibrosis, and the first JAK inhibitor approved for any indication.

The clinical results that supported approval weren’t subtle. In the pivotal data, a far larger share of ruxolitinib-treated patients achieved at least a 35% reduction in spleen volume compared with placebo or best available therapy. Symptom relief followed the same pattern: substantially more patients saw at least a 50% reduction in total symptom score compared with placebo.

For Incyte, it was the end of the decade-long “are we really doing this?” phase. The company that had once sold genomic subscriptions was now launching its first drug—and graduating from an R&D-heavy organization into a commercial biopharma.

And Jakafi wasn’t just a single victory. It introduced a powerful idea that would shape everything that came next: a pipeline in a product. One molecule, one mechanism, many possible diseases that share the same underlying biology. Ruxolitinib started as a myelofibrosis drug. Incyte’s bigger ambition was to make it a platform.

V. The Golden Era & The "Echo" Chamber (2013–2017)

With Jakafi throwing off real, growing cash, Incyte entered what felt like a golden era. The drug didn’t just meet expectations—it kept earning the kind of follow-on wins that turn a breakthrough into a franchise.

On December 4, 2014, the FDA approved ruxolitinib for polycythemia vera in patients who had an inadequate response to, or were intolerant of, hydroxyurea. Compared with myelofibrosis, this opened the door to a meaningfully larger population—and it gave Incyte a second engine on the same molecule. The “pipeline in a product” idea wasn’t theory anymore. It was the company’s business model.

And in the years that followed, Jakafi kept expanding. In May 2019, its U.S. label broadened again to include steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease. Then, in September 2021, it expanded further to cover chronic graft-versus-host disease after failure of one or two lines of systemic therapy.

But even as Jakafi grew into the defining product of the company, Incyte was already looking past it—because in oncology, standing still is a slow death.

At the same time, the entire cancer world was tilting toward something that, for a moment, seemed like the next revolution: immuno-oncology. Merck’s Keytruda (pembrolizumab) and Bristol Myers Squibb’s Opdivo (nivolumab)—the PD-1 inhibitors—were producing jaw-dropping results in diseases like melanoma and lung cancer.

The pitch was clean and compelling. Tumors survive, in part, by putting the immune system to sleep. PD-1 drugs “release the brakes,” waking T cells back up so they can attack. The problem was that, for all the hype, they didn’t work for everyone. Only a subset of patients responded. So the industry turned into a single, frantic question: what can we combine with PD-1 to make it work in more people?

Incyte believed it had a prime candidate: epacadostat, an investigational inhibitor of an enzyme called IDO1 (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1). Mechanistically, epacadostat was designed to block IDO1 by competitive inhibition, without interfering with IDO2 or tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO). The promise was that shutting down IDO1 could help reverse tumor-associated immune suppression—making checkpoint inhibitors hit harder.

Early signals added fuel. In single-arm studies in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma, epacadostat combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors showed proof-of-concept. Response rates looked better than what you’d expect from checkpoint inhibitors alone, and the market did what it always does in a hot cycle: it extrapolated.

Wall Street loved this story. Jakafi made Incyte credible and self-funded. Epacadostat made it feel inevitable. If epacadostat could expand the universe of Keytruda responders, the commercial opportunity wasn’t incremental—it was enormous. Incyte’s valuation swelled accordingly, and the company started to get talked about less as “the Jakafi company” and more as a would-be kingmaker in the most fashionable corner of oncology.

By 2017, the drug was deep in the combination frenzy: epacadostat with pembrolizumab (Keytruda) in multiple cancers with Merck, and epacadostat with nivolumab (Opdivo) with Bristol Myers Squibb.

And that set the stage for the moment everything would come down to.

ECHO-301—Incyte’s Phase 3 trial of epacadostat plus Keytruda in first-line melanoma—became one of the biggest binary readouts biotech investors had circled for 2018. Years of promising early-stage data were about to meet the only judge that matters: a randomized Phase 3 trial.

The tension was almost perfect storytelling. Incyte already had its miracle molecule. But miracles don’t last forever—patents expire, competition arrives, and the world moves on. Epacadostat was supposed to be the proof that Incyte could do it again.

For a stretch, the market treated that outcome as a when, not an if. And the entire company’s long-term narrative started to hinge on a single set of results.

VI. The Crash: The Failure of ECHO-301 (April 2018)

The morning of April 6, 2018, arrived with the weight of billions of dollars riding on a single announcement.

An external Data Monitoring Committee had reviewed the pivotal Phase 3 ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252 trial—epacadostat plus Merck’s Keytruda in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma—and delivered the verdict no one wanted to hear: it wasn’t working.

The study failed to meet its primary endpoint. Epacadostat didn’t improve progression-free survival versus Keytruda alone. Worse, the second primary endpoint, overall survival, wasn’t expected to reach statistical significance either. On the committee’s recommendation, the trial was stopped.

In plain language: the combination didn’t beat the standard. The “partner drug” thesis—in the biggest test that mattered—collapsed.

And the data didn’t leave much room for interpretation. Progression-free survival was essentially identical between the arms: a median of 4.7 months for epacadostat plus pembrolizumab versus 4.9 months for placebo plus pembrolizumab, with a hazard ratio of 1.00. Overall survival pointed in the wrong direction numerically, too, with a hazard ratio of 1.13—favoring the control arm.

The market reacted instantly. In early trading, Incyte’s shares fell nearly 22%, dropping from the prior day’s close of $83.07 to around $65. By the end of the day, the stock was still down more than 20%, wiping out billions of dollars in market value in a matter of hours.

The pain didn’t stay contained to Incyte’s ticker.

Merck—and rival Bristol Myers Squibb—had bet real time and attention on epacadostat through major clinical collaborations, pulled in by promising single-arm results. As recently as the prior September, an update showing an overall response rate of 56% for Keytruda plus epacadostat had helped cement the narrative that ECHO-301 was a near-formality. Instead, the randomized data delivered the industry’s least favorite sentence: in melanoma, at least, it didn’t live up to expectations.

The shockwaves hit the broader IDO inhibitor field immediately. NewLink Genetics, another company developing an IDO-targeting therapy, announced within hours that it would review its clinical programs in light of the ECHO-301 results. Even with a different approach, NewLink acknowledged what everyone was thinking: this was bad for the entire category. Its shares dropped by nearly 43% that same Friday.

Inside Incyte, the retrenchment started right away. The company stopped enrollment in six trials combining epacadostat with Keytruda and Opdivo. It discontinued enrollment in four pivotal studies pairing epacadostat with Keytruda in bladder, kidney, and head and neck cancers. Two trials combining epacadostat with Bristol Myers Squibb’s Opdivo also stopped enrolling.

Just like that, years of momentum turned into a cleanup operation.

And the lesson was as old as biotech, even if the hype cycle made it feel new: mid-stage data can seduce you. An uncontrolled Phase 2 study of epacadostat plus Keytruda had shown what looked like a massive progression-free survival benefit in melanoma, and that result fueled much of the confidence heading into ECHO-301. After April 6, it was hard to call it anything other than a mirage.

For investors and industry observers, ECHO-301 became a case study in confirmation bias. Small samples, single-arm trials, and a red-hot immuno-oncology narrative had turned possibility into assumed inevitability. Then Phase 3—randomized, controlled, unforgiving—snapped the story back to reality. Even a roughly $20 billion company could trade like a penny stock when a binary readout went wrong.

On the call that Friday, CEO Hervé Hoppenot tried to steady the ship. He pointed to the underlying strength of the business, especially Jakafi’s growth, and to an upcoming regulatory decision for baricitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. But the larger truth was unavoidable: whatever Incyte had been in the market’s imagination, it was now back where it started.

It was “the Jakafi company” again—and its immuno-oncology dreams had just been reduced to rubble.

VII. The Second Act: Dermatology & The Patent Cliff (2019–Present)

After ECHO-301, Incyte was forced into a very practical, very uncomfortable question: what do you do when nearly everything flows through one product—and you can already see the day its exclusivity ends?

The answer has been a two-part strategy. First: extract more value from ruxolitinib through new formulations and additional uses. Second: build new pillars, both by advancing internal programs and by buying assets that can matter on the other side of Jakafi.

The most elegant move was also the most counterintuitive: take the company’s flagship oral JAK inhibitor and make it a skin drug.

In September 2021, ruxolitinib cream—Opzelura—was approved in the United States for mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. It was the first topical JAK inhibitor approved in the U.S. Then, in July 2022, the FDA approved Opzelura for vitiligo.

That second approval mattered even more strategically. Opzelura became the first and only FDA-approved product for repigmentation in nonsegmental vitiligo—an area where patients had lived for years with basically no approved options. Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disease marked by patches of depigmented skin caused by the loss of melanocytes. Overactivity in JAK signaling is believed to contribute to the inflammation involved in the disease. In the U.S. alone, more than 1.5 million people are diagnosed with vitiligo.

Commercially, Opzelura also represented a deliberate shift in Incyte’s business model. Jakafi is a rare hematology drug: relatively small patient numbers, high price per patient, and deep specialty prescribing. Opzelura is dermatology: large populations and a volume game. By 2024, Opzelura reached $508 million in net revenue, up 50% year over year, and Incyte guided to $630–$670 million for 2025.

Incyte also went shopping to strengthen what comes next.

In early 2024, the company expanded its position in tafasitamab through a MorphoSys transaction. On February 5, 2024, Incyte announced an asset purchase agreement with MorphoSys AG that granted Incyte exclusive global rights to tafasitamab, a humanized Fc-modified CD19-targeting immunotherapy marketed in the U.S. as Monjuvi and outside the U.S. as Minjuvi. Incyte paid $25 million for rights it didn’t already own. It had been working with MorphoSys on tafasitamab since 2020. The drug is approved for a form of relapsed lymphoma and has been in advanced testing for other blood malignancies.

A few months later, Incyte made another move—this time to deepen its inflammation and dermatology pipeline. In May 2024, it acquired San Diego-based Escient Pharmaceuticals for $750 million. The deal brought in two oral candidates: EP262, being developed for inflammatory skin conditions, and EP547, in two Phase 1 trials for itching associated with kidney and liver diseases. Together, they reinforced the portfolio behind Opzelura.

But underneath every new label expansion and acquisition is the same looming deadline: the Jakafi patent cliff.

Incyte received pediatric exclusivity, adding six months to the expiration for all ruxolitinib patents and extending Jakafi’s patent expiry through December 2028. Patent protection is expected to end around 2028 in major markets, opening the door to generics and the pricing pressure that comes with them. Jakafi’s patents are expected to be open to challenges from March 22, 2028. Based on its patents and exclusivities, the estimated generic launch date is March 22, 2029.

That matters because Jakafi is still the engine. As patent protection begins to fall away starting in 2028, the company could face a sharp decline in revenue as generic competitors enter. Analysts have projected a potential revenue gap of up to $3 billion by 2028 tied to that expiration.

Incyte’s response is a life-cycle management push with a name that makes the ambition explicit: LIMBER—Leadership in MPNs and GVHD BEyond Ruxolitinib. The goal is to extend ruxolitinib’s usefulness and defend the franchise as long as possible, including work on a once-daily formulation and novel ruxolitinib-based combinations with new targets.

And as the company headed into this next phase, leadership changed at the top.

On June 26, 2025, Incyte announced that its Board unanimously appointed Bill Meury as President and CEO and a member of the Board. He succeeded Hervé Hoppenot, who retired after 11 years with the company and served as an advisor to the CEO through the end of the year. Lead Independent Director Julian Baker was elected Chairman of the Board.

Hoppenot’s tenure is the bridge between Incyte’s “Jakafi company” identity and whatever comes next. Over the last decade, Incyte grew into a multibillion-dollar business with a commercial portfolio that’s now six therapies wide. Anchored by Jakafi, that lineup includes fast-growing Opzelura, lymphoma drug Monjuvi, and the PD-1 inhibitor Zynyz, among others—helping drive $4.2 billion in sales last year.

Now the mission is clear, and it’s unforgiving: build a second engine before the first one runs out of road.

VIII. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

Incyte’s story is a reminder that biotech isn’t one business. It’s a bundle of businesses stitched together—science, capital markets, manufacturing, regulation, and timing. When it works, it looks like genius. When it doesn’t, it can look like hubris. Three lessons keep showing up.

The "Pipeline in a Product" Strategy

Jakafi is the cleanest example of how one molecule can become an entire company. Ruxolitinib started in myelofibrosis, then expanded into polycythemia vera, acute graft-versus-host disease, and chronic graft-versus-host disease. And then Incyte pulled off the clever lifecycle move: keep the same underlying engine, change the form factor, and open a new market with ruxolitinib cream for atopic dermatitis and vitiligo.

Each new approval did two things at once. It extended the commercial life of the franchise, and it reduced the feeling that Incyte was betting everything on a single, narrow rare disease.

But there’s a trap embedded in the elegance. When your “pipeline” is really multiple uses of the same compound, you’re still concentrated—just in a more sophisticated way. You’re building breadth across indications, but you’re also stacking your future on the same underlying intellectual property. When Jakafi’s protection ends, that protection doesn’t fade gradually across a dozen unrelated products. It drops out from under the whole hematology franchise at once.

Geographic Arbitrage: The US Rights Gambit

The Novartis partnership is a classic biotech trade: cash and certainty now, upside later—except the “later” upside is permanently capped.

By selling ex-U.S. rights, Incyte kept the U.S. business, where pricing and margins are strongest, and it bought the time and resources to get ruxolitinib approved. In 2009, that wasn’t a finance optimization. It was oxygen.

But the cost is visible in hindsight. Under the agreement, Novartis built the international ruxolitinib franchise while Incyte built Jakafi at home. In a recent year, Incyte booked $2.7 billion in Jakafi sales plus $418 million in royalty revenue, while Novartis recorded $1.9 billion in sales outside the U.S. That’s the trade made tangible: Incyte got to become a commercial company, but it also agreed to share the global spoils forever.

For anyone evaluating deals like this, the real question isn’t “Is this good or bad?” It’s “Is this necessary?” Sometimes, like it likely was for Incyte in 2009, it’s the difference between finishing the race and running out of cash a mile from the line. Other times, companies reach for the partnership because it’s easy, not because it’s required—and they wake up years later realizing they sold more of the future than they intended.

Binary Risk: The ECHO-301 Lesson

If you want a single exhibit for why biotech behaves differently than almost any other sector, it’s ECHO-301. One Phase 3 readout didn’t just disappoint—it rewrote Incyte’s narrative overnight and vaporized more value than many companies ever achieve.

The takeaway isn’t that biotech investing is irrational. It’s that biotech outcomes are lumpy, and the lumpy outcomes dominate everything. That’s why position sizing and diversification aren’t “nice to have” risk management tools here. They’re survival tools.

And underneath the market mechanics is the more uncomfortable lesson: confirmation bias is a drug, too. Epacadostat’s early data in single-arm studies looked like the missing puzzle piece for checkpoint inhibitors. The whole field leaned into the story. Then the randomized Phase 3 trial showed the combination didn’t beat the standard of care. In retrospect, what looked like signal was noise.

Single-arm trials can mislead. Small sample sizes can seduce. And in biotech, the only thing more dangerous than being wrong is being confidently wrong—because the bill comes due all at once.

IX. Analysis: Power & Strategy

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Cornered Resource (Primary): For most of the last decade, Incyte’s moat has been straightforward: intellectual property. The patents around ruxolitinib and JAK inhibition gave the company real protection, real leverage, and the ability to price Jakafi like the specialty oncology franchise it is. That’s how you get to billions in revenue off a single molecule. But this power comes with an expiration date. As the 2028 patent cliff approaches, the very thing that made Incyte so valuable starts to decay—because patents aren’t a flywheel. They’re a countdown clock.

Counter-Positioning (Weak): Incyte’s early wedge was convenience. Instead of an injectable biologic, doctors could prescribe an oral pill. That matters in real life: easier administration, fewer barriers, faster adoption. The problem is that this edge doesn’t stay exclusive. Today, other players—GSK, Pfizer, and others—have their own oral JAK inhibitors. Once everyone has an oral option, “oral” stops being a strategy and becomes table stakes.

Switching Costs (Moderate): In myelofibrosis and other rare blood cancers, stability is precious. If a patient is doing well on Jakafi, physicians are often hesitant to rock the boat. Switching therapies can introduce new side effects, new monitoring burdens, and real clinical risk in a fragile population. That creates retention. But it doesn’t fully protect the franchise—because competition tends to show up first in new starts, not in the installed base.

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of Substitutes (High): The JAK landscape is no longer a one-company story. A dozen JAK inhibitors have been approved for clinical use, including ruxolitinib, pacritinib, fedratinib, tofacitinib, baricitinib, abrocitinib, filgotinib, oclacitinib, peficitinib, upadacitinib, deucravacitinib, and delgocitinib. That’s a crowded shelf. Jakafi faces pressure from newer JAKs in adjacent indications—and the ultimate substitute, generics, sits just over the horizon.

Power of Buyers (Increasing): In the U.S., Pharmacy Benefit Managers increasingly decide what gets covered, what gets restricted, and what gets squeezed on price. That dynamic matters most in big-population markets—exactly where Incyte is trying to go with Opzelura. Dermatology is less like rare oncology, where access tends to be more direct, and more like consumer-scale healthcare, where formulary positioning can make or break growth. Incyte has to thread the needle: price for value, but not so high that access collapses.

Competitive Rivalry (Intense): Incyte is fighting in two of the most competitive arenas in medicine: oncology and inflammation. The competitors aren’t scrappy startups. They’re global pharma companies with deep pockets, established commercial teams, and massive R&D engines. In this environment, “good science” is necessary—but not sufficient.

Bull and Bear Cases

The Bull Case: Opzelura keeps compounding into a true dermatology franchise. Additional indications for ruxolitinib cream—hidradenitis suppurativa and prurigo nodularis—expand the market and reinforce that the topical move wasn’t a one-off trick, but a repeatable platform. Management has said it expects at least 18 key milestones in 2025, including four new product launches. Meanwhile, pipeline assets like axatilimab (now approved as Niktimvo) and povorcitinib begin to matter financially, creating real revenue streams that can stand beside Jakafi rather than living in its shadow. In this version of the story, Incyte reaches the patent cliff with multiple engines already running.

The Bear Case: The core risk is simple: the cliff arrives before the bridge is finished. As generic ruxolitinib appears in 2028–2029, Jakafi revenue falls sharply—potentially by 50% or more. Opzelura growth slows under the combined weight of competition and pricing pressure. And the pipeline, which has to do the heavy lifting, either stumbles in late-stage trials or disappoints commercially. In that world, Incyte doesn’t disappear—but it shrinks into a subscale biopharma, with less cash to fund the very R&D that could have saved it.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For investors tracking Incyte, two numbers tell you, week by week, whether the story is bending toward bull or bear:

-

Jakafi Net Product Revenue Growth Rate: This is the speedometer on the legacy engine. If growth decelerates, it can signal saturation, competitive erosion, or the limits of life-cycle management. If it holds up, it buys time—time is the most valuable asset Incyte has before 2028.

-

Opzelura Net Product Revenue and Patient Starts: This is the clearest read on diversification. Opzelura doesn’t just need to grow; it needs to prove it can scale into a billion-dollar-plus franchise. Incyte’s 2025 guidance of $630–$670 million gives a clean benchmark: the company has set the bar. Now it has to clear it.

X. Conclusion

Incyte’s story runs across three decades, two corporate identities, and multiple lives that most companies never get the chance to live. It rode the genomics gold rush, survived the dot-com crash, bet the company on a cross-country pivot, struck gold with Jakafi, got publicly humbled by ECHO-301, and is now sprinting toward a patent cliff it can’t negotiate with.

The transformation from Incyte Genomics to Incyte Corporation is still one of biotech’s clearest reinvention stories. This company was founded in 1991 to build a genomic database—essentially an information business. But when data became cheap and abundant, it had the clarity to admit the model was dying, the discipline to rebuild around chemistry and clinical development, and the patience to wait nearly a decade for the pivot to pay off.

Now, the hard part is back. With only a few years until Jakafi faces generic competition, Incyte is doing what amounts to a rebuild in motion. Opzelura has to keep scaling in dermatology. The pipeline has to turn from “promising” into “proven.” And the acquisitions have to land as durable foundations, not expensive detours.

The broader lesson is the one Incyte has lived in real time: in biotechnology, you can be right about the science, wrong about the timing, and catastrophically wrong about the hype. JAK inhibition worked. Genomics subscriptions didn’t. IDO inhibition, in the end, didn’t deliver.

As outgoing CEO Hervé Hoppenot said, “I am proud to retire at a time when Incyte has the strongest management team, internal R&D pipeline and commercial portfolio ever.” The question that remains—the one that will define this Third Act—is whether that portfolio is strong enough to carry the Phoenix of Delaware through 2028 and beyond.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music