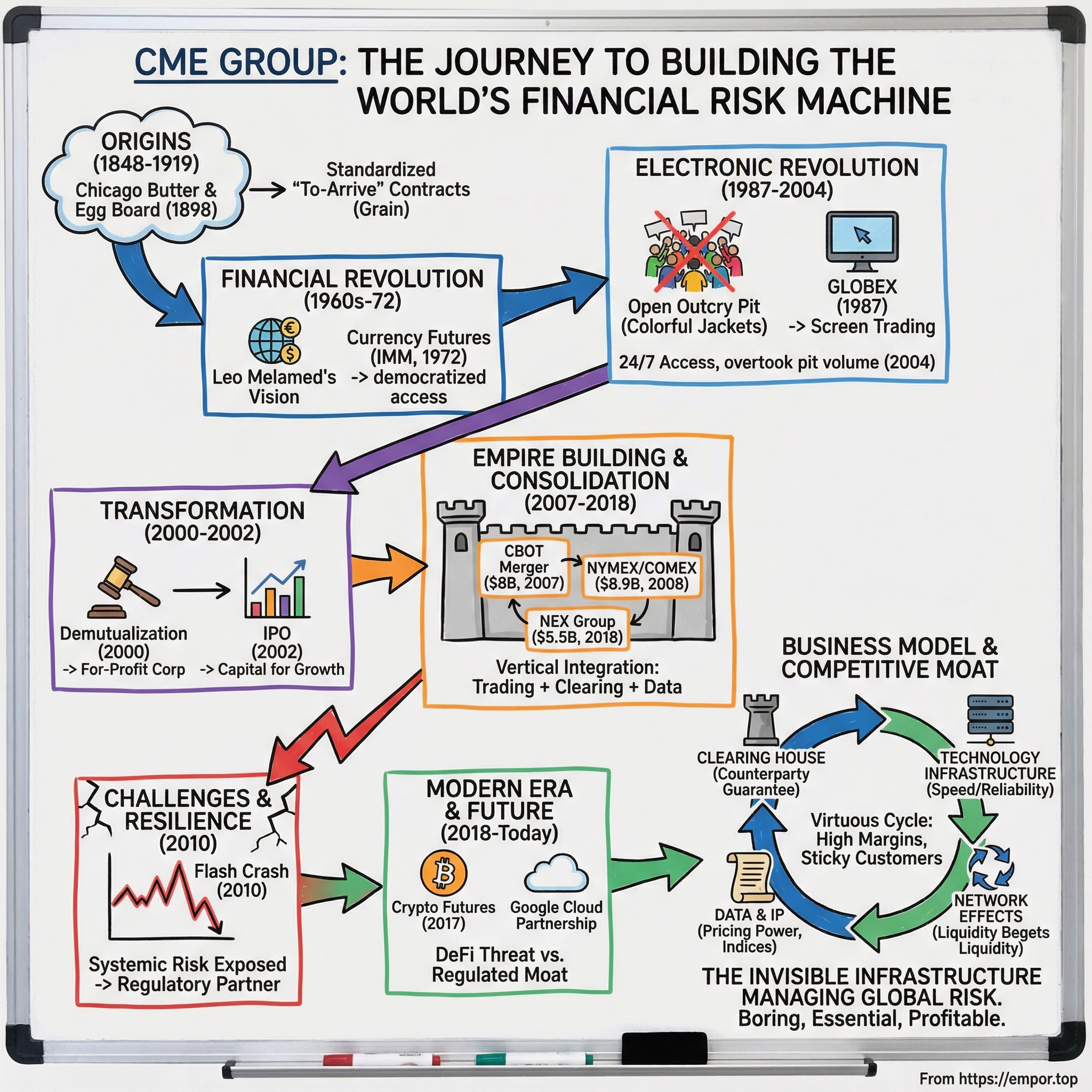

CME Group: The Story of How Chicago Built the World's Financial Risk Machine

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 4:00 AM in Chicago. The city is mostly asleep, but inside a vast electronic marketplace headquartered at 20 South Wacker Drive, the lights are already on. In microseconds, futures and options contracts trade on everything from corn to cryptocurrencies, interest rates to weather risk. A bank in Tokyo hedges its dollar exposure. An oil trader in London locks in next month’s price. A farmer in São Paulo protects a soybean crop against a sudden collapse. Different time zones, different motivations, one shared destination: CME Group.

By late January 2026, CME Group has a market capitalization of roughly $105 billion and processes about 28.1 million contracts per day. Over the trailing twelve months, it’s generated around $6.4 billion in revenue with operating margins near 68 percent. Those are the kind of numbers that make infrastructure investors pay attention—and they’re only the headline.

Because a margin like that is a signal, not just a statistic. For every dollar CME brings in, roughly sixty-eight cents turns into operating profit. Apple, one of the most efficient machines in business history, runs closer to 30 percent. Google tends to land in the high twenties. Even Visa, a titan of transaction processing, sits in the low-to-mid sixties. CME isn’t just profitable. It’s unusually profitable, while running a piece of market infrastructure the global financial system leans on every single day.

So here’s the question that makes the whole story click: how did a regional exchange for butter and eggs become the central risk-transfer engine of modern finance? Why did Chicago—not New York, not London—become the birthplace of so much financial innovation? And how did a business most people never think about end up with something that looks a lot like a financial monopoly?

That’s what this episode is about: standardization turning chaos into trillion-dollar markets; an immigrant who survived the Holocaust and helped reinvent global finance; technology colliding with century-old traditions; and the hidden magic trick at the center of it all—clearing. We’re going from the muddy streets of 1840s Chicago to today’s world of always-on, globally distributed trading, meeting the characters who shaped it, hitting the crises that tested it, and pulling apart the business model behind one of America’s most durable competitive advantages.

II. Origins: Butter, Eggs, and the Birth of Futures (1848–1919)

To understand CME Group, you have to start with Chicago in the mid-1800s. The city wasn’t just growing; it was becoming the switchyard of American commerce, sitting between the farms of the interior and the eaters on the coasts. Grain, livestock, dairy—everything flowed through Chicago on its way east.

And that created a brutal problem: timing.

Farmers harvested on nature’s schedule. Consumers demanded food on theirs. So prices whipsawed. A bumper harvest could flood the market and crush prices. A bad season could send prices soaring and leave buyers scrambling. For the people actually doing the work—planting, hauling, storing, milling—this wasn’t abstract volatility. It was a yearly roll of the dice that could wipe out a farm or a merchant.

What everyone lacked was a way to make a deal today about a price tomorrow.

In 1848, eighty-two Chicago merchants came together to form the Chicago Board of Trade, the CBOT. Their breakthrough was almost boring in how practical it was: standardized “to-arrive” contracts. Instead of haggling over one-off deals—this farmer, that buyer, this grade, that delivery window—they created contracts with fixed terms: quantity, quality, delivery place, delivery date. Once a contract is standardized, it becomes interchangeable. And once it’s interchangeable, it can trade.

That’s the alchemy. Standardization created liquidity. A farmer could sell a crop before it was harvested. A miller could lock in input costs months ahead. And a new character could enter the story: the speculator, willing to take the price risk that the producer and buyer didn’t want. The CBOT hadn’t just built a marketplace. It had built a machine for moving risk from those who couldn’t afford it to those willing to price it.

It also beat the alternative—constant bespoke negotiation. Without standard contracts, every transaction was a custom deal, hard to compare, hard to unwind, and hard to enforce. If one side walked away, the other side ate the loss. A standardized market, with margin deposits, made default less likely and trust more scalable. This was financial engineering before anyone had a name for it.

For the next fifty years, the CBOT dominated grain. But Chicago wasn’t only grain. By the 1890s, the city’s warehouses and cold-storage facilities were packed with butter, eggs, poultry, and other perishables—goods the CBOT didn’t handle.

So in 1898, produce dealers reorganized the Chicago Product Exchange into the Chicago Butter and Egg Board. Same core idea, different merchandise: build a central market, standardize the contract, let prices be discovered in the open, and let buyers and sellers hedge. Only now the underlying goods didn’t just fluctuate in price—they could spoil.

Perishables made the need for risk management even more obvious. Eggs don’t wait for you to find the perfect buyer. Butter doesn’t stay perfect forever. Supply was seasonal too: hens laid more in spring and summer than in winter, which meant price swings that could make or break anyone holding inventory. If you could agree today on a price for delivery later, you weren’t just trading—you were stabilizing a business.

In 1919, the members made a defining decision. Butter and eggs were a start, but they were too narrow. The exchange restructured, renamed itself the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, and expanded into other commodities like potatoes and onions. The new name was a mission statement: this wasn’t a specialty board anymore. It wanted to be a real exchange.

Still, for decades, CME lived in CBOT’s shadow. CBOT was the establishment: grain futures, institutional credibility, the aura of being first. CME handled what some sniffed at as “the smelly stuff.” Important products, real businesses—but not the kind that shaped national headlines.

And sometimes, they were too successful at attracting speculation. Onion futures became so controversial that Congress banned them outright with the Onion Futures Act of 1958—still the only commodity-specific trading ban in American history.

By mid-century, CME needed something bigger than potatoes and onions. A new identity. A new product line. And that reinvention would come from an unlikely source: a Polish refugee who wandered into the world of futures while looking for a law clerk job.

III. Leo Melamed and the Financial Revolution (1960s–1972)

Leo Melamed didn’t come up through finance. He came up through survival.

He was born Leibel Melamdovich on March 20, 1932, in Bialystok, Poland, into a Jewish family shaped by learning and ideas. His father taught mathematics. Then, in September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and the ground fell out from under everything. The family fled east to Vilna, Lithuania—one of the last places that still felt, for a moment, like it might be safe. It wasn’t. The Soviets annexed Lithuania in 1940, and the vise started to close.

What happened next is one of those hinge-of-history stories where a single person’s decision changes everything. In the summer of 1940, the Melamdovich family obtained a transit visa from Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese vice-consul in Kaunas. Sugihara issued visas against his government’s orders, hand-signing thousands—sometimes for eighteen hours a day—until his hand cramped. His moral gamble saved an estimated six thousand lives.

With that visa, the family took the long way out: across Siberia by train, to Vladivostok, then to Kobe, Japan, and finally across the Pacific. In 1941 they arrived in the United States and settled on Chicago’s South Side. Leibel was nine. In time, he’d Americanize his name to Leo Melamed.

They arrived with virtually nothing. Melamed learned English, adapted quickly, and built the kind of relentless work ethic you see in people who understand—personally—how fast stability can disappear. He studied at the University of Illinois, graduating in 1952, then enrolled at John Marshall Law School in Chicago.

And then, almost by accident, he walked into the futures business.

Looking for a part-time law clerk job, Melamed answered a want ad from Merrill Lynch, assuming it was a law firm. Instead, he found himself standing on the trading floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. He took a job as a runner, the bottom rung of pit life, sprinting paper orders through the noise and adrenaline. The pay wasn’t great. But the place had a pulse. It hooked him.

He passed the bar in 1955 and practiced law for several years. But the floor kept calling. By 1965 he left law to trade full-time. In 1967, he won a seat on the CME board. Two years later, at thirty-seven, he became chairman.

It was not a triumphant moment for CME.

The onion ban had embarrassed the exchange, and the product lineup—pork bellies, live cattle, frozen orange juice—was real, liquid, and useful, but it didn’t confer prestige. CBOT still towered over CME in volume and reputation. In the popular telling, CBOT was where serious markets lived. CME was where the “other stuff” traded.

Melamed’s big insight was to stop thinking about what CME had been, and start asking what a futures contract could be. If a futures market was a machine for transferring risk, then in theory you could plug in anything with price uncertainty.

He found his “anything” in the slow-motion breakdown of the postwar monetary order.

After World War II, the world ran on Bretton Woods: major currencies pegged to the U.S. dollar, and the dollar convertible to gold at thirty-five dollars an ounce. For decades it delivered stability and helped fuel the postwar boom. But by the late 1960s it was cracking under the weight of U.S. deficits—driven by Vietnam War spending and Great Society programs—alongside European surpluses.

On August 15, 1971, President Nixon suspended dollar-gold convertibility in a televised address. The old rules were gone. Exchange rates began to float, and a new kind of volatility surged through global trade and finance.

To Melamed, it looked familiar. Farmers had weather risk. Food processors had input-cost risk. Now banks, importers, exporters, and governments had currency risk—massive currency risk—and no standardized way to manage it.

So he asked the question that changed everything: if you can hedge wheat, why not hedge the Deutsche mark? If people will speculate on pork bellies, why not the Japanese yen?

The logic was clean. The politics were not. Treating money as a commodity sounded ridiculous to much of the financial establishment. Currency trading, they argued, belonged inside banks and central banks—not in a shouting pit in Chicago.

Melamed needed legitimacy. And he went straight to the source.

He commissioned Milton Friedman—University of Chicago economist, global celebrity, and Nobel laureate in waiting—to write a feasibility study on currency futures. Friedman supported floating exchange rates and market pricing; he loved the idea. His eleven-page paper, “The Need for Futures Markets in Currencies,” laid out the case: better price discovery, lower transaction costs, and a practical hedging tool for a world that had just lost its monetary anchor.

The paper cost CME $7,500. Its real value was that when bankers, regulators, and skeptics asked, “Who do you think you are?” Melamed could answer, “Milton Friedman thinks we’re right.” That’s a very different conversation.

On May 16, 1972, CME launched the International Monetary Market, the IMM, with futures on seven currencies: the British pound, Canadian dollar, Deutsche mark, French franc, Japanese yen, Mexican peso, and Swiss franc. It was the first futures exchange for financial instruments—period.

At first, it was awkward. Volume was thin, spreads were wide, and plenty of people didn’t understand what they were looking at. Banks were skeptical. Regulators were cautious. Some days the IMM floor felt empty compared to the thundering grain pits across town.

But the macro reality didn’t care about anyone’s skepticism. Through the 1970s, currency volatility became a fact of life, driven by inflation, oil shocks, and geopolitical upheaval. And once that volatility showed up on corporate income statements, demand for hedging showed up on the trading floor.

The IMM was only the beginning. In 1976, CME introduced Treasury bill futures, bringing standardized hedging to interest rates. In 1981 came Eurodollar futures, based on LIBOR, which would become a foundational instrument for managing short-term interest rate exposure. And in 1982, the exchange launched S&P 500 index futures, giving investors a way to hedge—or express a view on—the entire stock market with a single trade.

Two decades after the category was born, Nobel laureate Merton Miller called financial futures “the most significant innovation of the past two decades.” He wasn’t being poetic. Financial futures didn’t just add a new product line. They rewired how risk moved through the global economy.

And they elevated CME from a second-tier commodity exchange into something far bigger: essential infrastructure.

But Melamed wasn’t done. He had another revolution coming—one that would collide head-on with the very pits that made him.

IV. The Electronic Revolution: Building Globex (1987–1992)

By the mid-1980s, the Chicago pits were legend. Hundreds of traders crammed into octagonal rings, wearing bright jackets that telegraphed which firm they belonged to, screaming bids and offers in the open-outcry system. It was loud, physical, and weirdly beautiful.

It was also a moat.

On the floor, locals had real advantages that never showed up in the rulebook. They could see who was leaning which way, sense when a big order had entered the pit, and react in a heartbeat. If you weren’t there—if you were a customer placing orders by phone—you were always a step behind. The trading floor wasn’t just where prices were made. It was a club, and the club had no interest in making membership less valuable.

To an outsider, it looked like pure chaos: a basketball-court-sized room full of people shouting numbers and flashing hand signals all at once. But to people who grew up in it, it was an operating system. Gestures meant buy or sell, quantity, price. A good trader could track multiple conversations, triangulate intent, and jump in at exactly the right moment. Proximity itself became information, and information became money.

Leo Melamed looked at that whole world and saw the next bottleneck.

In 1987, he proposed something that sounded like science fiction to a lot of his own members: a fully electronic futures market, accessible from terminals anywhere in the world, running beyond the hours of the pits. He called it Globex—Global Exchange.

The vision was simple: if futures were going to be the world’s risk-transfer engine, they couldn’t be constrained by a physical room in Chicago that opened and closed on a local schedule. Computer-based trading was still young. The commercial internet wasn’t a thing yet. Most serious finance still moved by phone. But Melamed had already watched one revolution—financial futures—go from “ridiculous” to indispensable. He was betting on the next one.

The hardest part wasn’t the tech. It was politics.

CME’s membership was full of floor traders who understood exactly what an electronic market implied. Many had paid huge sums for seats. Their skills were built for the pit: reading the crowd, managing chaos, executing with speed that came from being physically present. A screen threatened to turn that advantage into a memory. Why would customers pay wide spreads and brokerage commissions if they could hit bids and offers directly?

Melamed had to persuade members to vote for a future that would eventually shrink the very world that made them powerful. So he sold it as an extension, not a replacement: Globex would handle trading when the floor was closed, opening Asia and Europe without touching the core daytime business. It was a carefully chosen argument—true enough to pass, and vague enough to give skeptics a reason to say yes.

The technology still had to work. CME partnered with Reuters to build the first version. The bar was brutal: it had to be fast enough to feel real, reliable enough to trust with real money, and robust enough to serve traders across time zones. It took five years. Then, on June 25, 1992, Globex went live—widely recognized as the first electronic futures trading system. For the first time, you could trade CME contracts from a booth at the exchange, or from a desk thousands of miles away.

At first, it was a slog.

Floor traders largely ignored it. Many customers didn’t trust it. Early sessions were thin, with wider spreads and the occasional glitch—exactly the kind of evidence critics needed to say, “See? Screens can’t replace pits.” But Globex wasn’t trying to win the whole day on day one. CME focused it on after-hours trading, when the floor couldn’t help customers anyway. That gave the system room to mature without forcing a head-on civil war inside the building.

Then the world caught up.

By the late 1990s, electronic markets weren’t a novelty; they were becoming an expectation. In September 1998, CME rolled out the second generation of Globex, based on a modified version of the NSC trading system rather than Reuters’ technology. It was faster, steadier, and built for scale. At the same time, the internet was rewiring what customers assumed should be possible. If you could do banking on a screen and trade stocks online, why not futures?

And there was pressure from abroad. European exchanges—especially Germany’s Eurex—were going fully electronic and taking share. That threat forced the U.S. futures world to stop treating screens as optional.

The proof arrived in milestones. Electronic volume climbed through the early 2000s, and on October 19, 2004, Globex recorded its one billionth transaction. The pits didn’t vanish overnight, but the center of gravity had shifted. By the mid-2000s, most CME trading was happening electronically, and the floor was starting to look less like the engine and more like the museum.

What changed wasn’t just convenience. It was who could participate, and on what terms. A hedge fund in Singapore could trade S&P 500 futures with the same access to the market as someone standing in Chicago. Geography stopped mattering. Friction fell. Volume surged.

And for CME, the business itself began to change shape. The exchange wasn’t just renting space for humans to shout in. It was running a technology platform, and platform economics kicked in: more users created more liquidity, which attracted more users, which drove more volume. Globex became the inflection point—taking CME from a powerful regional marketplace to a global, always-on franchise that could scale far beyond the limits of any physical trading floor.

V. Demutualization and Going Public (2000–2002)

For more than a century, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange ran as a nonprofit mutual. If you owned a seat, you weren’t just a customer. You were an owner. You voted on the rules, you benefited from the economics, and you helped govern the place.

That structure made a ton of sense when the exchange was essentially a physical venue—a set of pits, a rulebook, and a community that policed itself. But by the late 1990s, it was turning into a competitive handicap. The world was moving toward faster markets, bigger technology budgets, and global access. CME’s decision-making process was still built for a clubhouse.

The core issue was governance. In a mutual, power is distributed across members with very different incentives. Big institutions wanted lower fees, more liquidity, and better electronic execution. Many floor traders wanted to protect the advantages that came from being physically present—advantages that translated into real money. Market makers wanted one set of rules; speculators wanted another. International participants pushed for more coverage outside U.S. hours.

Trying to move anything meaningful through that mix was slow, political, and exhausting. And the biggest initiative of all—serious, ongoing investment in world-class electronic infrastructure—was especially hard. In a mutual, the people voting on huge capital projects are often the same people being asked to pay for them, and not everyone believes they’ll personally see the upside.

There was another issue too: the mutual model blurred the line between marketplace operator and marketplace participant. Members weren’t just setting the rules. They were trading under them. Regulators had long been uneasy with that “regulated and regulator at the same time” dynamic, and the broader market infrastructure world was drifting toward separating commercial operations from governance and oversight.

CME’s way out was demutualization: converting from a member-owned nonprofit into a shareholder-owned, for-profit company. In November 2000, CME became the first major U.S. financial exchange to do it.

The mechanics were complex, and intentionally so. Seat holders didn’t just lose their stake—they received it in a new form. Individuals and entities with trading privileges became equity owners. More than 95 percent of the Class A common stock and all of the Class B common stock went to people or entities that had held memberships. CME also adopted a dual-class structure that preserved key member benefits, like trading privileges and fee discounts, while still creating a corporate structure that could raise capital and operate with a more conventional board-and-shareholder model. Politically, that dual-class setup mattered: it was how CME got enough members comfortable enough to vote yes.

Strategically, the shift was straightforward. As a for-profit company, CME could act like a modern business: invest aggressively, pursue growth, and eventually use stock as currency. And the new posture showed up quickly. In 2001, CME recorded trading volume of more than 411.7 million contracts—up 78 percent from the year before. Some of that reflected the moment: the dot-com unwind and the aftermath of September 11 drove demand for hedging and risk transfer. But the organizational change mattered too. Decisions got faster. Big investments became easier to justify.

Then came the next step: the public markets.

In December 2002, CME Holdings went public through an IPO on the New York Stock Exchange—another first for a major U.S. exchange. It didn’t just raise capital. It changed what CME was. From that point on, management’s job wasn’t primarily to balance the competing desires of member-traders. It was to build long-term enterprise value for shareholders.

That shift created tension, but it also created clarity. Technology projects that would have died in committee could now be judged like any other investment. Pricing could be optimized for the health of the overall platform, not just for the preferences of insiders. And, crucially, CME now had something it had never had before: a publicly traded stock that could be used as a strategic weapon.

CME didn’t just change itself—it helped write the modern exchange playbook. In the years that followed, demutualization spread across the industry, with exchanges like the New York Stock Exchange, Nasdaq, and the London Stock Exchange moving in the same direction. CME had cracked the code first. And with a new structure, a new mandate, and a new currency, it was ready for its next phase: consolidation.

VI. Empire Building: The Great Consolidation (2007–2018)

Once CME had a public stock, a global electronic platform, and a for-profit mandate, the next move was almost inevitable: buy scale.

In an electronic market, scale isn’t bragging rights. It’s the product. The more contracts you list, the more activity you attract. The more activity you attract, the tighter the spreads get. The tighter the spreads get, the more activity you attract. And if all those contracts clear through the same clearinghouse, customers get something even more valuable than liquidity: capital efficiency.

That’s where cross-margining comes in, and it’s worth making it concrete. Imagine a bank is long Treasury futures and short equity index futures. Those positions can naturally offset in a downturn: rates fall, Treasury prices rise, stocks fall. If one clearinghouse sees both sides, it can reduce the total margin the bank has to post. If two different clearinghouses see only half the picture, they can’t. So the exchange with the broadest, most diverse set of products doesn’t just offer more things to trade—it offers a lower cost of doing business. And that’s incredibly sticky.

This is the economic engine behind CME Group’s acquisition spree.

The centerpiece was the merger with the Chicago Board of Trade, the crosstown rival that had been the older, bigger, more established exchange for most of their shared history. On October 17, 2006, CME announced it would acquire CBOT in a deal initially valued around $8 billion. Strategically, it was clean: CME was dominant in financial futures; CBOT was powerful in agricultural products and Treasury contracts. Put them together, and you’d have a single platform and a single clearinghouse spanning most of what global institutions actually needed to hedge.

But the path to that marriage wasn’t gentle. Intercontinental Exchange, ICE—based in Atlanta and run by Jeffrey Sprecher—came in with a hostile counterbid. A bidding war followed, and the price climbed. By the time it was done, the deal valued CBOT at about $11.9 billion, roughly 25 percent above CME’s original offer. CBOT shareholders received 0.375 shares of CME Group Class A stock for each share of CBOT, plus a one-time cash dividend of $9.14 per share, about $485 million in total.

The deal closed on July 12, 2007. The combined company took the CME Group name.

The impact was immediate and structural. Two exchanges that had competed for more than a century now offered customers a single clearinghouse across interest rates, equity indices, currencies, agricultural commodities, and Treasuries. For institutions, the big win wasn’t marketing. It was margin. If you could offset risk across product lines and post less collateral, you could run more exposure with the same balance sheet. That advantage didn’t just attract volume—it made leaving expensive.

Then CME Group went for what it still lacked: energy and metals.

In August 2008, as the global financial crisis was spiraling and markets were seizing up, CME completed its acquisition of the New York Mercantile Exchange and its subsidiary COMEX for about $8.9 billion in cash and stock. NYMEX was the center of gravity for crude oil, natural gas, and refined products. COMEX was the key venue for gold, silver, and copper. In one move, CME filled its biggest product gaps and became the home of the major futures categories under one roof.

That deal also landed at exactly the moment the world re-learned why centralized clearing mattered. The crisis exposed how dangerous opaque, bilateral risk could be—especially in derivatives. As over-the-counter exposures destabilized the system, regulators moved toward more standardization and more clearing. In the U.S., Dodd-Frank later required many OTC derivatives to be cleared through central counterparties. CME Group, now armed with a broader product set and a massive clearing operation, was positioned to capture the shift. The same crisis that crushed much of finance expanded CME’s opportunity.

After NYMEX and COMEX, the next moves looked smaller, but they followed the same playbook: consolidate liquidity, expand the clearing net, and eliminate standalone islands of volume.

In December 2012, CME Group bought the Kansas City Board of Trade for $126 million in cash, adding hard red winter wheat and absorbing one of the last independent grain exchanges.

And in November 2018, CME Group bought London-based NEX Group for $5.5 billion. This one mattered not just for products, but for the shape of the company. NEX owned BrokerTec, a dealer-to-dealer fixed-income trading platform with a major role in U.S. Treasury cash bond trading, and EBS, a major foreign exchange spot trading venue. With NEX, CME wasn’t just the place you went to hedge risk in derivatives—it gained a footprint in the underlying cash markets too. That pulled CME further into the full trading lifecycle: spot execution, derivatives hedging, and clearing and settlement.

Along the way, CME also made a quieter, very modern infrastructure move: getting closer to the indexes that powered its flagship contracts.

In 2010, CME purchased 90 percent of Dow Jones & Company’s financial-indexes business, which fed into the S&P Dow Jones Indices joint venture. In 2013, CME acquired the remaining interest for $80 million, bringing its stake to 27 percent. This wasn’t just about owning a nice, capital-light data business. It was about strategic alignment. Some of CME’s most heavily traded products—like E-mini S&P 500 futures—are built on those benchmarks. Having an ownership stake in the index provider tied CME more tightly to the reference prices its franchise depended on.

By 2018, the consolidation arc had largely played out. CME Group now operated four exchanges—CME, CBOT, NYMEX, and COMEX—plus two major cash-market platforms. It spanned interest rates, equity indexes, foreign exchange, energy, metals, agriculture, and more. Each acquisition widened the moat: more products, more liquidity, more netting efficiency, more reasons to keep everything in one place.

At that point, the question stopped being “Can CME win?” and became something more unsettling: what happens when the world’s risk-transfer engine gets too central to ignore?

VII. The Flash Crash and Market Infrastructure (2010)

At 2:32 PM Eastern on May 6, 2010, U.S. markets did something they weren’t supposed to be able to do.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average was already sliding on fears around European sovereign debt—Greece’s crisis was moving from headline to reality—when the floor seemed to drop out. In minutes, the Dow fell nearly a thousand points, then the biggest intraday point drop ever recorded. Roughly a trillion dollars of market value evaporated. Procter & Gamble, a blue-chip so steady it’s practically a bond in equity form, briefly printed at a penny. Accenture hit zero. And then, as abruptly as it started, the tape reversed. Within about twenty minutes, most of the losses were gone. The whole episode spanned roughly thirty-six minutes.

If you were watching a Bloomberg that afternoon, it felt like the laws of finance had been suspended. Prices that are supposed to represent a collective, rational consensus started throwing off outputs that looked like corruption in the data: forty-dollar stocks at a penny, then back near forty again. Machines did what they were programmed to do. Some momentum-driven algorithms sold into the decline, pushing it harder. Others saw the instability and backed away, which meant liquidity vanished exactly when the system needed it most. The result was a kind of cascade failure—one of the most sophisticated marketplaces ever built, suddenly behaving like it was brittle.

And sitting near the center of that feedback loop was CME Group—specifically, Globex, and specifically, the E-mini S&P 500 futures contract.

The E-mini is one of the most liquid instruments in the world and a primary way institutions hedge U.S. equity exposure. Because futures and stocks are tied together by arbitrage, what happens in the E-mini doesn’t stay in the E-mini. If futures drop sharply, programs sell baskets of stocks to keep prices aligned; that stock selling then feeds back into futures; and in a fast market, that loop can reinforce itself in seconds.

It took five years to identify the human catalyst regulators eventually focused on: Navinder Singh Sarao, a self-taught trader working from his parents’ house in Hounslow, a suburb of West London. His father ran a corner shop. His mother worked multiple part-time jobs. Nothing about the origin story screams “global market event.”

Sarao’s tool was a strategy known as spoofing. He placed huge sell orders in the E-mini—at times more than 20 percent of the visible sell interest—without intending to execute them. The goal wasn’t to sell. The goal was to make other people think someone was selling. Those “phantom” orders created the illusion of overwhelming supply, nudging prices down and pulling real sellers into the market. Then, as participants reacted, he could buy at cheaper prices—and cancel the orders that had helped push the market there.

He did it with what regulators described as “dynamic layering”: placing four to six exceptionally large sell orders just above the market and then automatically modifying them again and again to keep them from being hit as the market moved. Spoofing, but automated and scaled—run from a bedroom on custom software.

On the day of the flash crash, Sarao placed at least eighty-five spoof orders, and replaced or modified them more than nineteen thousand times. Regulators later said the combined value of his orders was roughly $200 million—around a quarter of the E-mini sell side at the time. And in a detail that would become uncomfortable for the exchange, CME had sent Sarao three warnings about his trading behavior that very morning, raising questions later about where surveillance ends and enforcement begins.

The CFTC ultimately concluded that Sarao didn’t single-handedly “cause” the flash crash—there were multiple contributors, including a large mutual fund sell order and the way algorithms cascaded through the dislocation—but that he was “at least significantly responsible” for the order book imbalances that made everything worse. The legal nuance mattered. The takeaway didn’t: a lone trader in suburban London helped amplify a trillion-dollar market event by manipulating a critical futures market.

What followed permanently changed U.S. market plumbing.

In an ironic twist, Globex held up relatively well. CME’s automated circuit breakers paused E-mini trading for five seconds when prices moved too far, too fast—a tiny window, but enough to interrupt the free fall. The New York Stock Exchange didn’t have an equivalent mechanism, and many of the most absurd prints happened in individual equities. That mismatch pushed regulators and exchanges to build coordinated cross-market protections: circuit breakers that work across venues, and “limit up/limit down” bands that stop trades from executing at prices too far from recent levels. Those safeguards are still in place and have been triggered multiple times since, including during the COVID-19 market panic in March 2020.

Sarao eventually pleaded guilty to one count of electronic fraud and one count of spoofing. In January 2020, he was sentenced to one year of home confinement with no jail time, a leniency tied to his cooperation with prosecutors and a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome. He was ordered to pay roughly $38 million in penalties and disgorgement, though much of his trading profits had been lost in bad investments.

The flash crash is remembered as a freak event. But for CME, it was also a preview of a new job description. When markets go electronic and interconnected, the exchange isn’t just a venue. It’s part of the stability system. And the bigger and more central CME became, the more that responsibility stopped being theoretical.

VIII. Modern Era: Crypto, Competition, and the Future (2018–Today)

In 2021, CME Group quietly closed most of its remaining physical trading pits, including the storied grain pits that had operated since the nineteenth century. They’d been shuttered since March 2020 due to COVID-19, and the pandemic simply accelerated what Globex had already made inevitable. The change was more than operational—it was cultural. A century and a half of shouting, hand signals, and human choreography gave way to screens, algorithms, and data centers. The pits where Leo Melamed started as a runner, where fortunes were made and lost in seconds, where financial futures first fought their way into legitimacy—went silent.

The bigger story, though, has been what CME chose to build next.

Its most consequential modern bet has been cryptocurrency derivatives. CME launched Bitcoin futures in December 2017, and the reaction from traditional finance ranged from skeptical to offended. Crypto, many argued, was a speculative sideshow that didn’t belong on an institution that styled itself as core market infrastructure. But CME’s leadership saw a familiar setup. Just like currencies in the early 1970s, a new, wildly volatile asset class had arrived—and the largest institutions in the world were going to need a regulated way to hedge it. Ethereum futures followed in February 2021. These weren’t novelty listings. They were the exchange doing what it has done at every major inflection point: turning chaos into standardized risk transfer.

By 2025, that bet looked less like experimentation and more like a franchise. In August, CME set a record with 411,000 daily crypto contracts traded, up 230 percent from the prior year, representing about $14.9 billion in value. Average daily open interest that month reached 335,200 contracts worth $31.6 billion, up 95 percent year over year. In September, notional open interest hit a record $39 billion, with more than 1,010 large open interest holders active across crypto products—evidence that this wasn’t just retail froth or a single burst of volume, but deepening institutional participation.

CME broadened the lineup too. Solana futures launched in March 2025 and XRP futures followed in May. Solana futures reached $1 billion in open interest faster than either Bitcoin or Ethereum futures had at launch—a sign of how quickly the institutional crypto derivatives stack was maturing, and how quickly CME’s distribution engine could scale new contracts once customers trusted the rails.

Then came the obvious question: if crypto trades all the time, why shouldn’t CME?

In October 2025, CME announced plans to offer around-the-clock crypto futures and options trading beginning in early 2026, pending regulatory approval. The design is nearly continuous, with only a two-hour weekly maintenance window. The goal is to eliminate “CME gaps”—those awkward price discontinuities that appear when CME’s futures market closes for the weekend while spot crypto keeps trading. For institutions, those gaps create basis risk and make hedges less precise. Closing the gap—literally—should tighten the relationship between CME futures and the broader crypto market and make the product feel more like true infrastructure.

Of course, CME isn’t alone in seeing the opportunity. Competition has been escalating fast. Coinbase acquired Deribit for $2.9 billion and launched its own twenty-four-hour futures trading for U.S. customers. Cboe planned to launch continuous Bitcoin and Ethereum futures in late 2025. Decentralized venues like dYdX and GMX have kept growing too, offering perpetual contracts without the regulatory overhead of traditional exchanges.

But CME’s edge is the one it’s been compounding for decades: trust at institutional scale. Regulated futures, standardized contracts, and central clearing—with CME Clearing stepping in as the counterparty—are not “nice to haves” for pension funds, asset managers, and sovereign wealth funds. They’re the entry ticket. Many of these institutions can’t touch offshore perpetual swaps or unregulated venues, no matter how liquid or cheap they look. CME doesn’t just sell a product. It sells permission.

Beyond crypto, the other defining move of this era has been CME’s partnership with Google Cloud. Announced in November 2021 as a ten-year deal, it included a $1 billion investment from Google in CME Group—an unusually loud vote of confidence from a tech giant that doesn’t hand out strategic capital lightly.

The partnership has two layers. The first is straightforward but massive: CME is migrating its technology stack to the cloud, spanning trading systems, risk, data, analytics, and client-facing applications. By late 2025, the migration was well underway, and CME pointed to improved developer productivity, reduced technical debt, and early work on ultra-low-latency cloud performance. Google even built a dedicated private cloud region and a co-location facility in Chicago tailored to CME’s requirements—because in market infrastructure, geography and latency are still very real physics.

The second layer is more ambitious. In March 2025, CME and Google Cloud announced a tokenization pilot using Google Cloud Universal Ledger, a distributed ledger system designed for wholesale payments and asset tokenization. CME completed the first phase of integration and testing, began direct testing with market participants later in 2025, and targeted a commercial launch in 2026. If it works, the implication is simple and profound: collateral could move with far less friction. Today, when a bank posts collateral to the clearinghouse, that capital is effectively parked. Tokenized collateral could make that value more portable and more responsive—opening the door to faster movement of collateral, potentially real-time settlement dynamics, and less capital stuck in the pipes.

The numbers across the modern era reflect a business that keeps getting more essential. In 2022, CME Group reached record average daily volume of 23.3 million futures and options contracts. That record was broken again in 2025, when average daily volume rose to 28.1 million contracts, up 6 percent from 2024. The second quarter of 2025 stood out: average daily volume hit 30.2 million contracts and revenue reached $1.7 billion, up 10 percent year over year. The first quarter had already set records for revenue, operating income, and earnings per share, with total revenue exceeding $1.6 billion. For the trailing twelve months ending September 2025, revenue was approximately $6.4 billion, with market data revenue setting a record at $203 million in the third quarter. CME was expected to report fourth-quarter and full-year 2025 results on February 4, 2026.

IX. Business Model & Competitive Moats

To really understand CME Group, you have to understand something most people never see: the plumbing of global finance. When a pension fund in Norway wants to hedge oil exposure, a Japanese insurer needs to manage dollar risk, or a grain elevator outside Chicago wants to lock in corn prices for next spring, they all need a marketplace they can trust. CME is that marketplace. And its business model is simple: take a small toll every time risk changes hands.

The best analogy is a toll bridge. CME doesn’t trade for its own account. It doesn’t bet on oil or the S&P 500. It runs the bridge that everyone else has to cross, and it charges a fee for every crossing. That’s why it’s such an attractive business compared to proprietary trading. CME’s revenue depends on how much trading happens, not which way markets move. Up or down, boom or bust, the contracts still need to trade. In fact, CME often does best when the world feels least stable, because volatility drives both hedging and speculation. It’s counter-cyclical in a way that makes it unusually resilient.

Under the hood, CME’s revenue comes from a few big streams. The largest is transaction and clearing fees: a small fee on each side of each trade, plus a clearing fee for standing behind the trade and guaranteeing settlement. Then there’s market data—real-time and historical prices sold to traders, banks, data vendors, and analytics platforms—which topped $200 million per quarter in 2025 and has steadily become more valuable as finance becomes more data-driven. And there’s connectivity and co-location: firms pay for ultra-fast access to CME’s matching engines, and some pay even more to place their servers close to CME’s data centers, shaving off microseconds of latency. The magic here is operating leverage. Once the platform is built, processing one more contract costs almost nothing—so incremental volume largely turns into profit.

CME’s moats stack on top of one another, and that’s what makes the position so hard to attack.

First is liquidity network effects. In derivatives, liquidity begets liquidity. Traders want the deepest pool, because depth means tighter bid-ask spreads and lower execution costs. Once a contract becomes the default venue on CME, it’s brutally hard for a rival to pull that activity away—even with lower fees—because leaving is expensive in the one way traders care about most: execution. That’s why flagship contracts like the E-mini S&P 500 and interest rate futures have stayed so anchored to CME. Eurodollars eventually gave way to SOFR after the LIBOR transition, but the center of gravity didn’t leave CME. Even the most meaningful challenge in recent history—ICE taking some share in energy—required years of sustained effort and massive investment.

Second is clearing, the quiet superpower. CME Clearing steps in as the counterparty to every cleared trade, effectively standing between buyer and seller and guaranteeing performance on both sides. That removes counterparty credit risk, which matters enormously when a single failure can ripple through the system. Clearing also enables cross-margining: if a customer holds positions across rates, equities, and commodities, CME can recognize offsets and reduce the total margin required. That is real balance-sheet relief. Moving that activity to another venue often means giving up those efficiencies—an institutional-grade switching cost that’s hard to justify.

Third is regulation. Derivatives exchanges are among the most regulated businesses on earth. You can’t just spin one up in a garage. Approval takes time, compliance is expensive, and the bar only got higher after 2008. In a twist that benefits incumbents, the post-crisis push toward more cleared and standardized derivatives expanded CME’s opportunity while raising the hurdles for anyone trying to compete head-on.

Fourth is data and benchmark status. CME’s prices don’t just reflect markets—they define them. WTI crude oil on NYMEX isn’t merely a traded contract; it’s the reference price used by producers, refiners, airlines, and governments to structure agreements worth staggering sums. Once the world uses your price as the benchmark, your position stops being a product feature and starts being part of how the global economy measures itself. That kind of moat doesn’t fade easily.

X. Playbook: Lessons in Market Infrastructure

CME Group’s 128-year journey—from butter and eggs to Bitcoin futures—is a case study in how to build a business that becomes harder to replace the more the world relies on it. A few lessons jump out, and they travel well beyond exchanges.

First: standardization is the cheat code. Before the early futures markets, agricultural commerce was a mess of one-off deals. Every transaction required negotiation over quality, quantity, delivery location, delivery date, and price. Standard contracts flipped that dynamic. Once the terms were fixed, the contract became interchangeable. Once it was interchangeable, it could trade. And once it could trade, liquidity could form—and liquidity is what turns a marketplace into infrastructure.

CME kept replaying that move. Currency futures in 1972. Interest rate futures in 1976. Equity index futures in 1982. Bitcoin futures in 2017. Different eras, different assets, same core maneuver: take something volatile and hard to hedge, wrap it in a standard contract, and let the market do what markets do. The exchange that defines the standard usually becomes the default venue, and the default venue tends to keep the liquidity.

Second: demutualization is a governance unlock. The mutual model was great when an exchange was a physical room and a local community. But once the business became global, electronic, and technology-intensive, a member-owned structure started to behave like a brake. Too many stakeholders, too many competing incentives, and too much resistance to investments that might help the platform while hurting specific insiders. Moving to a for-profit shareholder structure gave CME faster decision-making, access to capital, and the ability to use stock as strategic currency. The fact that most major exchanges followed the same path is the strongest validation you can get.

Third: own the full stack. Vertical integration—trading, clearing, and data—made CME much tougher to attack than an exchange that only runs a matching engine. A competitor can try to undercut on fees or build a slicker front end, but institutional customers care about the whole lifecycle: execution, risk management, margin efficiency, and trusted settlement. Clearing is the center of gravity. It brings capital requirements, regulatory complexity, and cross-margining benefits that don’t copy easily. It’s also where switching costs quietly compound.

The most subtle lesson, though, is change management. CME didn’t just make disruptive moves; it staged them. Melamed sold Globex as after-hours “extension” before it became the main event. Demutualization didn’t erase member value overnight; it converted it into shares and preserved key privileges through a dual-class structure. Crypto wasn’t framed as a cultural surrender to a new world—it was framed as CME doing what it has always done: taking volatility and turning it into standardized, cleared risk transfer. Again and again, CME found ways to pull threatened stakeholders along rather than daring them to fight a war it couldn’t afford.

XI. Analysis & Investment Case

CME Group is one of the cleaner stories in financial services: a toll road on global risk, with a business model that tends to work no matter which direction markets move. But it’s not a free lunch, and the “why it works” matters just as much as the headline margins.

Start with the bull case. CME sits in an unusually strong position across multiple derivatives categories, and that strength reinforces itself. Liquidity attracts liquidity. The deeper the market, the tighter the spreads. The tighter the spreads, the more people trade. And because so much of that activity flows through CME’s clearinghouse, customers get margin efficiencies they can’t easily recreate anywhere else. That combination—network effects plus clearing—makes competitive displacement incredibly hard.

Zoom out and the demand backdrop is supportive too. Derivatives volumes tend to grow over time as the global economy gets more complex, new asset classes emerge, and regulation nudges more risk onto standardized, cleared markets. And CME has the kind of operating leverage that infrastructure businesses dream about: once the platform is built, the incremental cost of another contract is tiny. So when volumes rise, earnings usually rise faster.

If you run CME through Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers, the durability becomes easier to name. The company benefits from network economics (liquidity begets liquidity), switching costs (clearing relationships and cross-margining that customers don’t want to give up), scale economies (near-zero marginal cost per additional contract), and often counter-positioning (it’s hard for rivals to mimic the same integrated stack without disrupting their existing business). Many companies have one true “power.” CME arguably has four or five, and that goes a long way toward explaining why the economics look so extreme.

Porter’s Five Forces tell a similar story. Supplier power is limited; CME’s key inputs are talent and compliance, not scarce raw materials controlled by someone else. Customer power is real but bounded. Yes, the biggest banks and trading firms matter. But when it comes to listed derivatives in CME’s flagship products, there just aren’t many places with comparable liquidity and clearing. New entrants face a brutal combination of regulatory hurdles, capital requirements, and the cold-start problem of building liquidity from scratch. The most interesting force is substitutes: crypto-native venues and decentralized finance can offer alternative structures for certain products, but they don’t come with CME’s regulatory standing or institutional trust. Rivalry exists—ICE, Cboe, and Nasdaq all compete in specific pockets—but in the core futures markets, liquidity dynamics tend to turn competition into “winner take most.”

Now the bear case. The biggest existential risk is regulatory: if policymakers ever forced true interoperability between clearinghouses—essentially weakening CME’s ability to concentrate margin and net risk inside its own clearing ecosystem—that would strike directly at one of the company’s most powerful moats.

There’s also product-cycle risk. Interest rate futures have historically been one of CME’s biggest engines, but that business is sensitive to the rate environment. When rates are stable and volatility is low, hedging demand can fall, as it did in the years after 2008 when central banks pinned short-term rates near zero.

Crypto cuts both ways. It’s a growth vector, but it’s also an ecosystem with unique reputational and operational hazards. A major hack or fraud elsewhere in crypto could spill over into public perception, even if CME’s own market is regulated and centrally cleared.

And then there’s the Google Cloud migration. Strategically, it makes sense. Operationally, it’s a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar transformation of critical market infrastructure. The upside is meaningful, but so is execution risk.

On competition, ICE deserves the most attention. Under Jeffrey Sprecher, it has built a formidable exchange and data empire—including the New York Stock Exchange—and it competes directly with CME in energy and, increasingly, in parts of fixed income and data. Cboe is another serious player, particularly in options and volatility where its VIX franchise is a standout. The distinction, though, is breadth and integration: neither can match CME’s cross-asset portfolio paired with a deeply embedded clearing operation.

For investors tracking CME’s health, two KPIs matter more than almost anything else. The first is average daily volume, the cleanest read on activity, share, and the overall volatility environment. The second is revenue capture per contract, a proxy for pricing power and product mix. Put them together and you can explain most of the income statement: volume times revenue per contract, across trading days. If either metric starts to slide in a sustained way, that’s usually the first signal of something deeper—whether it’s competitive pressure, mix shift, or a change in how the market is choosing to express and hedge risk.

XII. Epilogue & Reflections

Run a simple thought experiment: what if CME Group just disappeared overnight?

The answer is uncomfortable. Banks, corporations, farmers, pension funds, and governments wouldn’t lose a nice-to-have trading venue. They’d lose one of the main ways modern finance manages uncertainty. Oil producers wouldn’t have a centralized place to hedge output. Airlines would struggle to lock in fuel costs. Pension funds would have fewer tools to manage interest rate exposure across enormous fixed-income portfolios. Benchmarks that entire industries rely on—energy, metals, grains—would lose their primary price-discovery engine, forcing producers and consumers back into fragmented, opaque negotiation. Commerce wouldn’t stop. But it would get more expensive, more volatile, and more fragile fast.

That gets to the real point: CME isn’t really in the exchange business. It’s in the trust business.

It writes the standardized rules. It publishes transparent prices. It guarantees settlement through clearing. It operates inside a regulatory perimeter that lets institutions participate at scale. That’s what allows two strangers—on opposite sides of the planet, with different legal systems, different time zones, and different incentives—to make a binding financial commitment and sleep at night. And that kind of infrastructure isn’t something you spin up with a slick interface, a whitepaper, or even a smart contract. It took more than a century of scars: world wars, market crashes, technology shifts, and regulatory reinvention.

Chicago’s role in all of this wasn’t accidental either. The city’s position at the center of American agriculture created the original need for futures markets. Its culture—pragmatic, engineering-minded, obsessed with getting the deal done—helped push the evolution from physical commodities to financial derivatives to electronic markets. And it produced both the intellectual architecture and the institutional muscle: economists like Milton Friedman, Merton Miller, and Eugene Fama at the University of Chicago, and practitioners who turned theory into markets that actually worked.

At the close of 1999, the former editor of the Chicago Tribune named Leo Melamed “among the ten most important Chicagoans in business of the 20th Century.” In 2017, the Emperor of Japan awarded him the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star—the highest honor bestowed on an individual—for his achievements in initiating financial futures markets worldwide. The symmetry is hard to miss: a refugee saved by a Japanese diplomat, honored decades later by Japan for building markets that reshaped global finance. Melamed retired from CME Group’s board in May 2018, but the world he helped create is still running, trade by trade, in microseconds.

And now CME is staring at another inflection point.

The Google Cloud partnership and tokenization initiative could change how collateral moves and how settlement works. Around-the-clock crypto trading is blurring the edges between traditional finance and digital assets. Artificial intelligence is reshaping surveillance, risk management, and analytics. The company that started by helping egg dealers manage spoilage risk is now building infrastructure for a financial system that never sleeps.

So the question for the next decade isn’t whether CME is important. It’s whether its moats are permanent features of market structure—or temporary advantages waiting to be routed around by new technology. History tilts in CME’s favor. Again and again, it has been the disruptor, not the disrupted: financial futures, electronic trading, crypto derivatives. Whether that pattern holds in an era of decentralized finance and AI is the most important open question hanging over one of America’s most consequential businesses.

XIII. Recent News

By the end of 2025, CME Group was doing what it almost always does when markets stay busy: it put up records. Average daily volume for the year came in at 28.1 million contracts, up 6 percent from 2024. The second quarter was the peak, with average daily volume reaching 30.2 million contracts alongside revenue of $1.7 billion. Market data kept compounding into a meaningful business of its own too, with third-quarter market data revenue topping $203 million. CME was set to report fourth-quarter and full-year 2025 earnings on February 4, 2026, and analysts expected Q4 diluted earnings of $2.72 per share, about 8 percent higher than the year before.

Crypto was the loudest growth story inside those results. In 2025, daily trading volume across CME’s crypto derivatives jumped 230 percent year over year, and notional open interest hit $39 billion in September. CME kept widening the product shelf—Solana futures arrived in March and XRP futures followed in May—and then leaned into the obvious operational reality of the asset class. With crypto trading nonstop, CME announced plans to move to twenty-four-seven crypto futures and options trading in early 2026, pending regulatory approval.

The Google Cloud partnership moved from headline to execution. CME completed the first phase of integration and testing for Google Cloud Universal Ledger, aimed at tokenization and wholesale payments. Direct testing with market participants was planned for late 2025, with a commercial launch anticipated in 2026. At the same time, the broader cloud migration continued, and CME pointed to gains in developer productivity and early work on ultra-low-latency performance—because in markets, shaving time off the pipe still matters.

And in a small, very Chicago coda: CME Group became the first-ever jersey patch sponsor for the Chicago White Sox. Not a financial milestone, but a telling one—this is a company that runs global market infrastructure in microseconds, and still chooses to plant its flag back home.

XIV. Links & Resources

- CME Group Investor Relations

- CME Group reports record annual ADV of 28.1 million contracts in 2025

- CME Group tokenization initiative with Google Cloud

- CME Group to launch 24/7 crypto futures and options trading in early 2026 (pending regulatory approval)

- Leo Melamed biographical sketch

- 2010 flash crash (Wikipedia)

- How CME Group is building on Google Cloud

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music