Allstate: The "Good Hands" in the Age of Algorithms

I. Introduction: A 93-Year-Old Company Fighting for Its Future

Picture the scene: Super Bowl Sunday, 2010. Millions of Americans are watching a man in a black suit get systematically wrecked by the universe.

He’s a tree branch that crushes your hood. He’s the teenage driver who plows into you while texting. He’s every annoying, expensive thing that can happen between your driveway and the grocery store.

And then he looks straight into the camera and says, “That’s Allstate’s stand.”

Mayhem—played by Dean Winters in a campaign created by Leo Burnett Chicago—hit in 2010 and instantly became one of the most recognizable advertising ideas in insurance. But Mayhem wasn’t just great marketing. He was a signal flare. A strategic pivot, broadcast in prime time.

Because in that moment, Allstate—the company that had helped define American auto insurance for nearly 80 years—was getting its lunch eaten. Not by a Silicon Valley upstart. By a cartoon gecko and a relentlessly cheerful cashier named Flo.

Progressive and Geico were winning the modern game: direct-to-consumer, data-driven pricing, and a cost structure that didn’t have to support an army of storefront offices. A J.D. Power report later found that Progressive and Geico accounted for 54% of the growth in auto premiums in 2018—but that outcome wasn’t sudden. It was the culmination of a decade-plus trend. Allstate was still profitable, but it was losing ground every year, watching its future get negotiated away a fraction of a point at a time.

This isn’t just an insurance story. It’s a case study in what happens when a legacy incumbent—one born out of a tire catalog during the Great Depression—realizes the very thing that made it great has become the thing that could kill it.

Allstate’s sacred cow was its exclusive agent model. For generations, that captive distribution force was a moat: loyal, local, and incredibly effective. Then the internet happened. Comparison shopping became a click. The moat turned into an anchor.

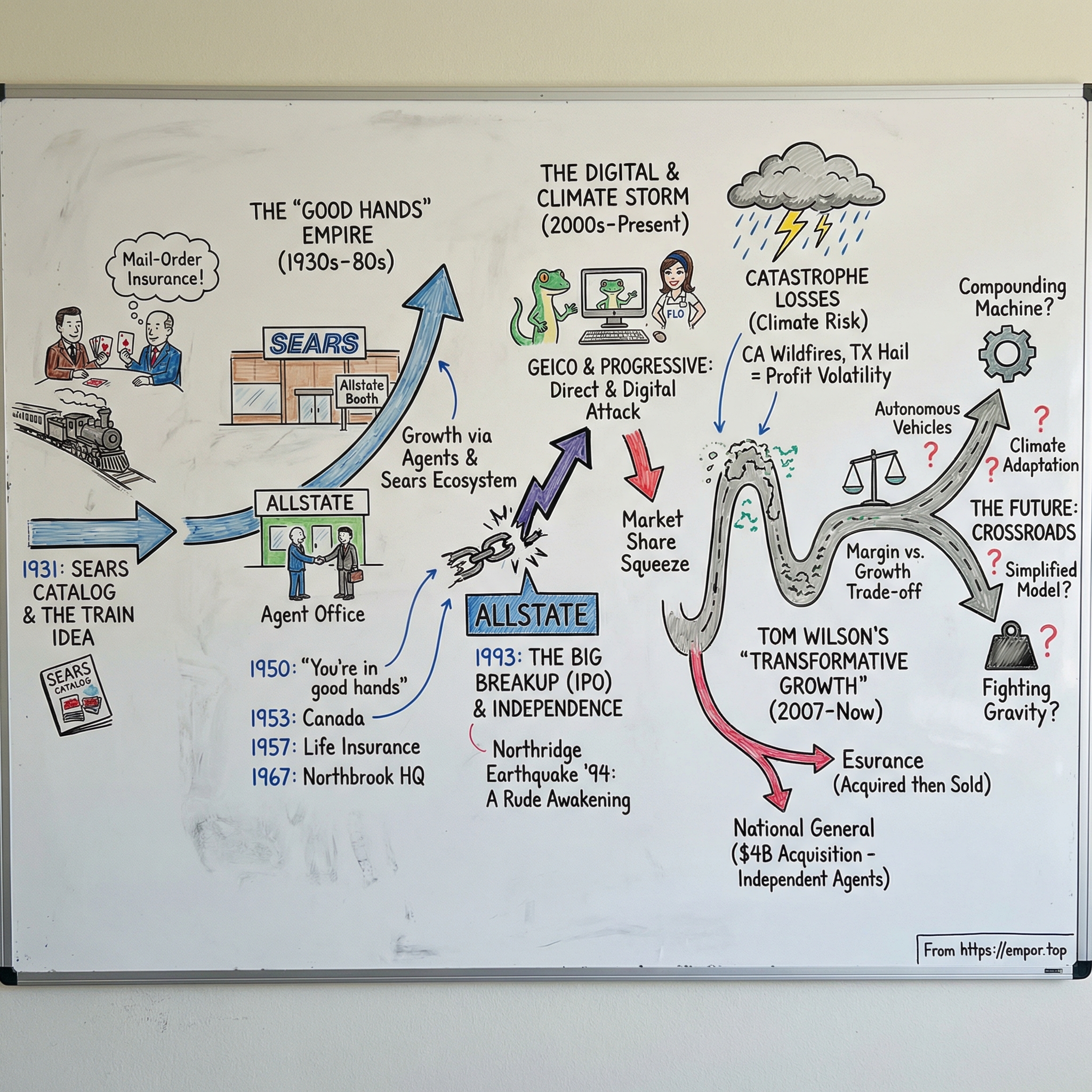

So the story we’re about to tell spans nearly a century: from a Sears boardroom bridge game that accidentally birthed an insurance empire, to the invention of the captive agent, to the stagnant 2000s when that model started to crack. Then comes the Esurance acquisition—more hedge than solution—and finally the radical “Transformative Growth” plan of the 2020s, which boiled down to a single, brutal idea: cannibalize yourself before someone else does.

At the center of it all is Tom Wilson, Allstate’s CEO since 2007 and Chair since 2008. He led the company through the financial crisis, and through an era where severe weather—fueled by climate change—kept rewriting the actuarial tables. Now he’s leading a multi-year transformation to remake how Allstate sells, prices, and operates.

Whether that strategy can turn a 93-year-old ship fast enough to matter—that’s what we’re here to find out.

II. Origin Story: The Bridge Game That Built an Empire (1930-1931)

The year is 1930. America is still dazed from the stock market crash. Bread lines are forming. Trust in the financial system has evaporated. By almost any measure, it’s the worst possible moment to start a new business.

And yet, that’s exactly when Allstate’s story begins.

The founding myth is wonderfully specific: a bridge game on a commuter train. In 1930, insurance broker Carl L. Odell floated an idea to his neighbor, Robert E. Wood: sell auto insurance by direct mail. Not as a gimmick—as a system.

Wood wasn’t just any commuter with a deck of cards. He was the president and board chairman of Sears, Roebuck & Co., a retail machine built on distribution. Sears already mailed merchandise into millions of American homes through its catalog. Odell’s insight was almost embarrassingly obvious once you said it out loud: Sears was already selling the stuff you needed to own and maintain a car—tires, batteries, parts. Why not sell the insurance that protected the car, too?

The channel already existed. The trust was already there. And compared to the traditional broker model, customer acquisition could be dramatically cheaper.

Wood bought it. The proposal went to the Sears board, and they approved it. On April 17, 1931, Allstate Insurance Company officially went into business, offering auto insurance by direct mail and through the Sears catalog.

Even the name carried the Sears DNA. “Allstate” wasn’t crafted in a Madison Avenue brainstorm. In 1925, Sears had run a national contest to name a new tire brand. That tire line became the name of an insurance company that would one day insure millions of households. Corporate history is full of carefully engineered brands; this one was a happy accident that stuck.

Lessing J. Rosenwald became Allstate’s first board chairman, and Odell was named vice president and secretary. The early operation was tiny, run out of Sears’ Chicago headquarters with about 20 employees. By the end of 1931, Allstate had 4,217 active auto policies and $118,323 in premiums. Its first claim? $1.65 to replace a broken door handle.

And despite the economy, the model worked. Allstate turned profitable in 1933, posting $93,000 in earnings after issuing 22,000 policies—helped along by targeted advertising in Sears catalogs. In the depths of the Great Depression, a brand-new insurer found a way to grow.

The Captive Agent Revolution

But selling insurance purely by mail had a ceiling. Unlike tires, insurance often needs explanation—what’s covered, what isn’t, and why it matters. So Allstate started inching toward something more human.

The first Allstate agent reportedly showed up with a card table inside the Sears Roebuck booth at the 1933 Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago. A year later, agents were working out of a growing network of Sears department stores around the country.

This was the pivot that defined Allstate for generations: from pure mail-order distribution to an agent-led model that still piggybacked on Sears’ physical footprint. Yes, commissions were a new expense. But overhead stayed low because Sears already had the space.

And critically, these weren’t independent brokers selling whatever policy paid best. They were “captive” agents, selling Allstate products exclusively. Over time, that exclusivity created a powerful flywheel: loyalty between agent and company, deep local relationships, and a distribution network that was hard for competitors to copy.

As the engine turned, the numbers followed. By 1936, Allstate’s premium volume had reached $1.8 million. Over the next five years, premium revenues more than tripled to $6.8 million on 189,000 active policies.

Then the broader industry got a regulatory tailwind. In 1941, only about a quarter of drivers carried auto insurance. New York passed a law requiring it, and other states soon followed. The legislation expanded the customer base, helping offset the slowdown in auto production and sales during World War II.

For understanding modern Allstate, this origin story matters. The company was born from distribution innovation: find customers where they already are—first in a catalog, then in a store. The captive agent model wasn’t an accident; it was the next logical step.

The twist—the one that sets up everything that comes later—is that distribution moats don’t stay moats forever. When the next wave arrives, they can turn into anchors.

III. The Golden Era: Post-War Boom to the Largest IPO in American History (1945-1995)

After World War II, America hit the accelerator. The economy expanded, suburbs sprawled outward, and car ownership became a defining feature of everyday life. Allstate grew right alongside it—so quickly in the 1950s that it was nearly doubling in size every couple of years—riding the surge in driving and the buildout of the Interstate Highway System after the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act.

This was the perfect environment for an insurer built around the American family car. More cars on the road meant more accidents, more loans, more financial exposure—and, increasingly, more states requiring drivers to carry coverage. Allstate wasn’t creating the wave. It was simply positioned exactly where the wave was breaking.

As the customer base expanded, Allstate broadened what it could sell them. It introduced fire insurance in 1954, then homeowners and life insurance in 1957. Over time, “Allstate” as a brand narrowed: by the late 1960s it was essentially tied to insurance, tires, and car batteries, before becoming insurance-only by the mid-1970s.

The Birth of "Good Hands"

In 1950, Allstate landed one of the most enduring pieces of brand positioning in American business: “You’re in good hands with Allstate.” The slogan was first used that year, and the story behind it has become part of company lore—credited to Davis Ellis, vice president and general sales manager, who helped develop it.

The brilliance wasn’t clever wordplay. It was emotional engineering. Insurance is, at its core, a product people buy because they’re afraid—of crashes, of storms, of losing everything to one bad day. Plenty of competitors leaned into that fear. Allstate did something subtler: it sold relief. Not “bad things might happen,” but “when they do, you’ll be okay.” That reassurance became a moat all its own, one that lasted for decades.

By the early 1970s, Allstate wasn’t just growing—it was carrying real weight inside Sears. In 1973, Allstate generated earnings of $203 million, nearly 30 percent of Sears’s total. What had started as a catalog experiment had turned into Sears’s profit engine.

The Sears Financial Services Experiment

In the 1970s and 1980s, Sears tried to turn that engine into a whole new machine: a financial-services supermarket. It bought Dean Witter in 1981 and created Discover in 1985. The idea was seductive: a customer could walk into a Sears store, buy a dishwasher, invest their savings, get a mortgage, and insure the car that brought them there.

The company even launched the Sears Financial Network, bringing brands like Allstate, Coldwell Banker, and Dean Witter together inside Sears locations. On paper, it looked like the future.

In reality, Sears had a bigger problem: its retail business was starting to crack under pressure from discount competitors. Execution got messy. Focus got diluted. And then the numbers turned brutal. In 1992, Sears posted a $3.9 billion loss—the largest ever from a North American retailer. The crisis changed everything. Allstate, the crown jewel, suddenly looked less like a sibling business and more like trapped value.

The 1993 IPO: Freedom from the Catalog

In June 1993, Sears sold 20 percent of Allstate to the public. The deal raised $2.4 billion—at the time, the largest initial public offering ever in the United States. It wasn’t just a financing event; it was Sears admitting it needed to retreat back to basics.

Mechanically, the IPO sold 89.5 million shares—19.9 percent of Allstate’s common equity—at $27 a share. Allstate, newly capitalized and newly visible to the public markets, went on to post a record 1993 net income of $1.3 billion on revenue of $20.9 billion.

Two years later, in June 1995, the separation became complete. Sears spun off the remaining 80 percent stake, distributing 350.5 million shares of Allstate stock to its shareholders. Sears’s attempt to be both a general merchandiser and a financial supermarket was effectively over. As Sears chairman and CEO Edward A. Brennan put it at the time: “The corporation has kind of reverted to what we were originally, and that's a very, very strong retail competitor.”

For Allstate, independence was a clean break—and a new beginning. But it also marked the top of an era. By the late 1990s, Allstate was a titan—the second-largest property and casualty insurer in America. It also had the defining features of an incumbent at its peak: big, profitable, and expensive to run, built around a vast network of human agents in physical offices.

And just as it stepped out from Sears’s shadow, two competitors were about to rewrite the rules of the entire industry.

IV. The Innovator's Dilemma: When Your Moat Becomes Your Anchor (1995-2010)

This is where the Allstate story turns into a textbook Innovator’s Dilemma.

For decades, Allstate’s captive agents were a distribution cheat code: local offices, familiar faces, relationships built over years. By 1970, the company employed around 6,500 agents. By the 1990s, the network had grown dramatically, and in countless towns, “your Allstate agent” was a real person you could call when something went wrong.

But the moat came with a cost structure baked into the product. Agents aren’t free. Commissions, office space, training, management layers, support staff—the whole machine was expensive. And in insurance, expense doesn’t vanish. It shows up in the premium.

Then the market changed. And the economics of that moat started to look like an anchor.

Enter the Gecko and Flo

Geico had been around since 1936, selling insurance directly to government employees. Its model was simple and brutal: no agent commissions, no storefronts, lower prices. For years, it was a niche approach.

In the 1990s and 2000s, it stopped being niche. Americans got comfortable buying things over the phone, and then online. “Direct” became mainstream.

Berkshire Hathaway had been accumulating Geico shares since the 1970s and bought the company outright in 1996. What followed wasn’t just an acquisition—it was a marketing and scale play. The gecko. “15 minutes could save you 15%.” The pitch was relentlessly clear: we’re cheaper, and switching is easy.

And as that message saturated America, Geico’s direct model let it pile on volume. It ultimately grew to cover more than 28 million cars, positioning itself as the budget-friendly default for comparison shoppers.

Progressive was coming from a different direction. It wasn’t just selling directly. It was changing how the product itself got priced.

The Tiering Revolution

In the early 1990s, Fair Isaac introduced credit-based insurance scores. Over time, they spread across the industry—FICO estimates that roughly 95% of auto insurers and 85% of homeowners insurers use credit-based insurance scores in states where they’re legally allowed for underwriting or risk classification.

Insurers didn’t roll this out with a press release. In the mid-1990s, companies started testing whether credit data could predict claim losses, and they kept it quiet. Fair Isaac and competitors like ChoicePoint pushed the idea forward, and large carriers—including Allstate and Progressive—moved into the world of algorithmic risk.

But Progressive took the logic further than anyone. Instead of broad demographic buckets, it leaned into fine-grained segmentation: credit, driving record, vehicle type, and dozens of other variables, all used to sort customers into hundreds of risk categories. The result was a powerful new capability—Progressive could underprice competitors for the best drivers, scoop up the most profitable customers, and either charge more to riskier drivers or avoid them altogether.

That dynamic is deadly for an agent-heavy incumbent. Allstate wasn’t just competing against another insurer. It was competing against a different cost structure and a different pricing engine at the same time.

Insurance companies and industry groups defended the shift to credit-based pricing as it spread, arguing it was a strong predictor of insured losses. Whether customers liked it or not, the market was moving toward data.

The Mayhem Response

Allstate couldn’t win a pure price war without rewriting its own operating model. So it chose a different battlefield: value.

In 2010, it introduced Mayhem—and it wasn’t subtle. Instead of promising savings, Allstate promised consequences. Leo Burnett pitched the character as a kind of Reservoir Dogs doppelganger—“Mr. Mayhem” in client sessions—and soon TV screens filled with a bruised-up man in black calmly narrating disasters as he caused them. Dean Winters’ deadpan physical comedy couldn’t have been more different from the steady reassurance of the “Good Hands” campaign led by Dennis Haysbert.

Mayhem worked because it did something rare in insurance advertising: it made risk feel real. And it repeated the same pointed phrase over and over: “cut rate” insurance. In every spot, the implication was clear. You might save money up front, but when something goes wrong, you could find out exactly what you didn’t buy.

It was brilliant marketing. It also contained an uncomfortable truth: Allstate was signaling it couldn’t—or wouldn’t—match the lowest prices. It would justify its premiums instead.

The problem is that advertising can slow a share loss, but it can’t reverse a structural disadvantage forever. Over time, Geico overtook Allstate to become the nation’s second-largest auto insurer. Progressive—selling online and through independent agents—eventually passed Allstate as well.

Allstate was still profitable. The brand was still powerful. But the ground under the model was shifting. And the next move the company made would show just how seriously it took the threat.

V. Inflection Point 1: The Esurance Acquisition and the Channel Conflict (2011)

Allstate had spent the 2000s watching the direct channel go from “interesting” to “existential.” If customers were going to shop for auto insurance the way they shopped for flights—open a browser, compare prices, click buy—then Allstate’s agent-first machine was going to keep bleeding share.

So in 2011, Allstate made its first big move to meet the internet on its own turf.

On October 7, 2011, the company announced it had secured all required regulatory approvals and closed its acquisition of Esurance and Answer Financial from White Mountains Insurance Group. The price tag was about $1 billion.

Esurance, at the time, was selling policies in 30 states and was coming off a five-year stretch where it doubled policies in force. Allstate, meanwhile, was losing policyholders to the biggest names in online insurance retail—Esurance, Progressive, and Geico. If you couldn’t beat the direct upstarts, the thinking went, buy one.

Tom Wilson, Allstate’s president and CEO, framed it as a way to cover the whole waterfront: the deal “provides immediate incremental growth in customer relationships and makes Allstate the only company serving all four major consumer segments based on their preferences for advice and choice.”

Allstate’s pitch was segmentation by buying behavior. Allstate agencies would serve customers who wanted a local advisor and a familiar brand. Esurance would serve the self-directed, brand-sensitive customer who wanted to buy online. Answer Financial would target shoppers who wanted to compare across carriers. And customers who used independent agents—more brand-neutral—would be served by Encompass.

It was a neat strategic map. It also lit a fuse inside Allstate.

The Agent Reaction

Allstate’s captive agents—its historic moat—saw the acquisition for what it might become: the company building a second front that could undercut them.

Jim Fish, executive director of the National Association of Professional Allstate Agents, didn’t hide the suspicion. He said many agents viewed the acquisition warily, arguing the company had been pushing its direct channel for years but had only recently seen any success. He also said Wilson was under pressure to reverse a decline in policies, and that “morale is at an all-time low.”

Fish’s critique cut both ways: yes, Esurance could boost Allstate’s direct business, but, in his view, it did little to address deeper issues. That’s the core tension you get when a company tries to modernize without breaking the model that still pays the bills.

Strategists have a name for this: channel conflict. If Allstate sold cheaper policies online through Esurance, wouldn’t that cannibalize what agents sold in their offices? And if it didn’t cannibalize, then what exactly was it doing—winning incremental customers, or simply attracting a different, potentially less profitable segment?

Allstate’s answer was to build a wall between the worlds. The company said it would keep Esurance headquartered in San Francisco and Answer Financial in Los Angeles, and, crucially, keep the brands separate. Customers who wanted an agent would go to Allstate. Customers who wanted to click and buy would go to Esurance. No conflict—at least in theory.

The Hedge That Wasn't

In hindsight, the Esurance deal looks less like a solution and more like a hedge: a way to have a seat at the direct table without forcing the agent organization to change.

Esurance did grow, but it never became the kind of scaled, reliably profitable weapon you’d need to take on Geico and Progressive head-to-head. The year before Allstate bought it, Esurance wrote $839 million in premiums. By 2018, that had grown to $1.9 billion. But profitability was elusive: Esurance lost $25 million on underwriting in 2018, after losing $56 million in 2017 and $124 million in 2016.

Policy growth also slowed. From the end of 2012, Esurance’s auto policies grew to 1.5 million from 1 million—less than 50% growth over that period. In the same universe, the Allstate brand sold through agents had well over 20 million auto policies.

And the bigger issue wasn’t Esurance’s absolute size. It was what the separation forced Allstate to do: split attention, split marketing dollars, and delay the hard decision about whether the “Good Hands” brand could compete in a world where the default customer behavior was price-shopping online.

Geico and Progressive kept gaining share. Allstate bought time—but it didn’t buy itself out of the central problem. The agent-heavy cost structure was still there, and it was still too expensive to win a sustained price war in the modern market.

VI. The Data Pivot: Arity and the Telematics Revolution (2016)

Allstate was still trying to untangle its distribution knot—agents versus apps—when it started placing a very different bet. Not on a new brand, but on a new raw material: data.

Insurance pricing has always been a kind of educated guess. For most of the industry’s history, carriers priced you using proxies: your age, your credit score, your ZIP code, your past claims. Those signals can be useful, but they’re still indirect. The obvious question is: why guess how someone drives when you could actually see it?

That’s the promise of telematics. And Allstate had already been working in the space for years. Arity had been trailblazing telematics since 2014, then officially spun out inside The Allstate Corporation on November 10, 2016—built on Allstate’s existing telematics expertise.

Tom Wilson didn’t position Arity as just another internal analytics team. He created a stand-alone unit: a telematics business he expected to grow rapidly, collecting driving data and selling analytics products to third parties.

The idea was elegant and a little unsettling in its simplicity. Instead of building a pricing model around who you are, build it around what you do behind the wheel. Arity focuses on using telematics data to understand driving behavior, identify distracted driving, detect collisions, and more. In the company’s own words, it’s a mobility data and analytics business aimed at making transportation smarter, safer, and more useful.

Beyond Internal Use

What made Arity strategically interesting wasn’t just that it existed—it was that Allstate wanted it to operate beyond Allstate.

When Allstate announced Arity in 2016, its initial focus was familiar in the industry: helping insurers run usage-based insurance programs, where drivers opt in to tracking through an app in exchange for potential discounts for good driving. But Arity’s business model expanded. Over time, Allstate’s Arity began selling access to driving data and analytics to third parties.

Arity says it has collected more than a trillion miles of driving data since its founding, at a pace of more than a billion miles a day, sourced from tens of millions of drivers in the U.S. The company also describes ArityIQ as “the world’s largest driving behavior database tied to claims,” built from data on more than 40 million drivers. In another statement, Arity says its data comes from 50 million active driver connections across all 50 states.

This is the swing: if Arity could become a shared data layer for auto insurance—powering underwriting and pricing not just for Allstate, but across the industry—that’s a different kind of advantage than an agent network or an ad campaign. It’s infrastructure.

The bigger vision was to push insurance from reactive to proactive: less about writing a check after a crash, and more about pricing risk from real-world behavior.

The Privacy Controversy

Of course, collecting and monetizing this much driving data comes with baggage.

In addition to telematics programs, Arity runs a targeted advertising business that allows companies to use driving data for ad targeting. Arity even claims it has amassed “the world’s largest driving behavior database for targeted advertising.” That framing pulls telematics out of the “safer roads” narrative and into a much more sensitive conversation about privacy and consent.

And the implications don’t stop at ads. As telematics gets more sophisticated, it changes the economics of insurance itself. The old system depended on a lot of averaging—low-risk drivers, in effect, helping subsidize high-risk drivers. The more precisely you can measure risk, the more that cross-subsidy breaks down. Drivers who opt out of sharing data may end up paying more. Drivers who opt in and look “safe” in the data can pay less.

For Allstate, Arity was both opportunity and hedge. Even if the fight for market share in traditional auto insurance stayed brutal, owning a meaningful piece of the industry’s data infrastructure could become valuable on its own—and could reshape what “moat” even means in the age of algorithms.

VII. Inflection Point 2: The "Transformative Growth" Plan (2019-2021)

By 2019, Tom Wilson had been CEO for twelve years. He’d watched market share slip away, tried the Esurance hedge, invested in telematics—and the core problem still hadn’t budged. Allstate was running a modern pricing and marketing war on a legacy cost structure.

So Wilson went bigger. Allstate bundled a set of sweeping moves under a single banner: the “Transformative Growth Plan.” The message was simple: stop tiptoeing around the future and start reorganizing the company for it.

A central piece was the most public admission yet that the Esurance experiment wasn’t the answer. Allstate said it would phase out the Esurance brand and move online sales under the Allstate name. Customers would still be able to buy home, renters, auto, and life policies online—just not from Esurance.

The Death of Esurance

Executives framed the decision as a way to expand customer access, reduce costs, and improve the overall offering. Retiring the money-losing Esurance brand, they said, would also free up meaningful dollars for marketing and for agent compensation.

Allstate spelled out the logic in plain terms: by 2020, consumers would be able to “select a method of interaction without restrictions,” and therefore “it will no longer be necessary to utilize both the Allstate and Esurance brands for direct sales and the Esurance brand will be phased out in 2020.”

This was the pivot. Eight years earlier, Allstate had paid about $1 billion for Esurance specifically to compete in the direct channel without setting its own agents on fire. Now it was shutting Esurance down and putting the Allstate brand—the “Good Hands” brand—directly into the online, price-competitive arena.

That choice also risked reopening the original wound: channel conflict. If customers could buy Allstate directly online, how would Allstate’s captive agents react if the online pricing undercut what they could offer in their offices?

Wilson made the stakes explicit: “Our competitors have increased their advertisement. We cannot let our historic brand dwindle away,” he said.

The National General Acquisition

Then, just seven months after announcing Esurance’s end, Allstate made an even bolder move. The company agreed to acquire National General Holdings for approximately $4 billion in cash, or $34.50 per share, with the transaction expected to close in early 2021 pending regulatory approvals and other customary conditions.

Wilson framed it as a distribution unlock: “Acquiring National General accelerates Allstate's strategy to increase market share in personal property-liability and significantly expands our independent agent distribution,” he said. Allstate added that the acquisition would increase personal lines premiums by $4.0 billion and lift market share by more than 1 percentage point to 10%.

National General, headquartered in New York City, was a specialty personal lines insurance holding company serving a wide range of customer segments through a network of approximately 42,300 independent agents for property-casualty products.

Strategically, this filled the hole in Wilson’s channel map. Allstate now had all three major distribution lanes under one roof: captive agents (the traditional Allstate model), direct sales (what Esurance had been, now under the Allstate name), and independent agents (via National General). The National General acquisition alone brought about 42,300 independent agents, in addition to the 10,100 Encompass and Allstate brand independent agents.

On January 4, 2021, Allstate announced it had closed the $4 billion acquisition. The company said the deal advanced its plan to grow personal lines insurance and increase market share by 1 percentage point.

Exiting Life Insurance

The Transformative Growth plan wasn’t only about how Allstate sold insurance. It was also about what kind of company Allstate wanted to be.

On November 1, 2021, Allstate announced it had closed the sale of Allstate Life Insurance Company (ALIC) and certain subsidiaries to entities managed by Blackstone for total proceeds of $4 billion, inclusive of Blackstone’s approximately $2.8 billion purchase price.

“Allstate's strategy is to increase personal property-liability market share and expand protection offerings to customers. This sale redeploys capital into highly attractive property-liability and protection service businesses and reduces interest-rate exposure,” Wilson said.

Financially, the shift was substantial. The sale of ALIC—along with the previously announced sale of Allstate Life Insurance Company of New York to Wilton Re—reduced assets by approximately $34 billion to $99 billion and liabilities by approximately $33 billion to $72 billion as of June 30, 2021. The transactions also resulted in a GAAP book loss of approximately $3.8 billion in the first quarter of 2021, while generating approximately $1.7 billion of deployable capital.

The strategic logic was clear: life insurance and annuities are capital-intensive and highly sensitive to interest rates. Property and casualty—especially auto—is where scale, data, and distribution are the real weapons. Wilson was narrowing the company’s focus and betting the future on winning that fight.

VIII. The Current State: Execution and Results (2022-2026)

By the mid-2020s, the Transformative Growth plan was no longer a slide deck or a press release. It was the operating system. The question became simple: after years of painful trade-offs—killing Esurance, buying National General, slimming down the company—did it actually show up in the results?

Financial Performance

In 2024, Allstate reported total revenue of $64.1 billion, up 12.3% from the year before. Net income for the year was $4.6 billion—a sharp reversal from a loss in 2023—with adjusted net income of $4.9 billion and a 26.8% return on equity. The momentum carried into early 2025: in the first quarter, revenue rose to $16.5 billion, up 7.8% year over year.

But for an insurer, the headline number that tells you whether the machine is working isn’t revenue. It’s underwriting.

In 2024, Allstate posted an underwriting profit of $1.8 billion, alongside a combined ratio of 94.3%—a major improvement from 104.5% in 2023. And in the quarter ending September 2025, the combined ratio was reported at 80.10%, down from 91.10% in the prior quarter.

The combined ratio is the industry’s bluntest truth serum: it measures whether the company is paying out less in claims and expenses than it’s collecting in premiums. Under 100% means the insurance business is profitable on its own. Over 100% means it’s losing money on underwriting and leaning on investment returns to make up the difference. By that yardstick, the shift from 2023 to 2024 wasn’t a small tweak—it was a turnaround.

The operating model changes showed up elsewhere, too. Auto market share increased from 9.3% to 10.2% since 2019, and homeowners share also rose. Allstate said it reduced its expense ratio by 6.7 points since 2018, driven by digitization, real estate optimization, and changes to its go-to-market model.

Market Position

According to NAIC data, Allstate Insurance Group recorded $35.6 billion in private passenger auto premiums and held 10.2% market share.

That still leaves Allstate in a familiar spot: a heavyweight, but not the heavyweight. The ten largest auto insurers in the U.S. are State Farm, Progressive, Geico, Allstate, USAA, Farmers, Liberty Mutual, Travelers, AAA (Auto Club Exchange), and American Family.

State Farm remains the giant, with $65.9 billion in premiums and 18.9% market share. Progressive wrote $56.8 billion and held 16.7%. Berkshire Hathaway’s group (including Geico) wrote $41.3 billion for 11.6%.

So yes, Allstate stabilized after years of erosion. But it’s still chasing leaders that built their scale advantage during the exact period Allstate was trying to reinvent itself.

Protection Services: The Diversification Play

One of the more underappreciated parts of Allstate’s strategy has nothing to do with auto pricing models or agent channels. It’s the quiet build-out of “protection” beyond traditional insurance.

A key moment came with SquareTrade, a consumer protection plan provider that distributes through many of America’s major retailers. Allstate acquired the privately held company for approximately $1.4 billion from a group of shareholders including Bain Capital Private Equity and Bain Capital Ventures, with the transaction expected to close in January 2017.

By 2024, Protection Plans revenue reached nearly $2.0 billion. Allstate said policies in force grew 60% since 2019 to 160 million, with adjusted net income of $157 million.

The strategic point is straightforward. If the long-term arc of driving is fewer accidents—whether from better safety tech or, eventually, autonomy—then the auto insurance profit pool shrinks. Protection services like device protection, identity protection, and roadside assistance are Allstate’s hedge against that future: a way to keep selling “peace of mind,” even if the car stops being the center of it.

IX. Analysis: The Bull Case, Bear Case, and Competitive Dynamics

The Bull Case

The optimistic read on Allstate starts with a simple observation: the big, painful pivot actually appears to be showing up in the numbers. The Transformative Growth plan wasn’t just a reorg; it was a cost and underwriting reset. Allstate lowered its expense ratio, clawed back market share, and returned to profitability. In the third quarter of 2025, the underlying auto insurance combined ratio was 86.0—an improvement of 6.0 points from the same quarter a year earlier.

The second pillar is distribution. For most of its history, Allstate was essentially a single-lane road: captive agents. Now it’s a three-lane highway. Captive agents for customers who want advice and a relationship. Independent agents via National General for shoppers who want choice and comparison. And direct sales under the Allstate brand for everyone who just wants a quote on their phone. In a market where buying behavior is half the battle, that flexibility matters.

Third is Arity. If insurance is moving from proxies to proof—less “who are you?” and more “how do you actually drive?”—then owning a massive telematics dataset starts to look like real leverage. Arity has marked the milestone of collecting more than a trillion miles of driving data. It became its own mobility data and analytics company in 2016, with a mission to make transportation smarter, safer and more useful for everyone. The strategic bet is that as telematics becomes table stakes, Arity becomes more than an internal tool; it becomes an asset with value outside Allstate’s own policies.

And finally, there’s Protection Services. While the industry obsesses over auto combined ratios, Allstate has been quietly building a second engine in protection plans. With 160 million policies in force, that segment has reached meaningful scale and gives Allstate a growth path that isn’t entirely hostage to the next cycle in auto pricing.

The Bear Case

The skeptical view starts where most customers start: price and claims experience. Allstate is often expensive, and it has a reputation among some customers for a frustrating claims process. Those two things are toxic in a category where switching is easy and shopping is constant. Even after years of investment, Allstate still has to prove it can sustainably compete with the cost structures and pricing machines of Geico and Progressive.

Then there’s the competitive reality check. Geico—long the volume-growth monster of the industry—swung hard the other direction. Between 2021 and 2023, it intentionally gave up market share, shedding six percentage points and falling behind peers. But in 2024, it posted the third-lowest combined ratio among major players, 70 percent, signaling that the pullback wasn’t a stumble; it was a deliberate return to underwriting discipline. It’s also a reminder that Berkshire Hathaway, guided by Warren Buffett’s philosophy, will happily trade growth for profitability—and can afford to do that longer than most.

Progressive, meanwhile, remains the most dangerous competitor in the category because it’s not just an insurer; it’s a compounding machine built on pricing precision. “On that front, Progressive is the industry leader,” said industry analyst Seifert. Progressive’s early and sustained investment in telematics—once viewed as gimmicky by plenty of the industry—has matured into a real advantage in underwriting and distribution. If Allstate’s goal is to become a modern insurer, Progressive is the benchmark, and it’s still moving.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: Intense. The top of the market is crowded and unforgiving. State Farm’s lead over Progressive has narrowed in recent years, and together they control more than a third of the U.S. car insurance market. This is a zero-sum fight: when one carrier grows, another usually shrinks.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate to High. Switching costs are low. Customers can compare quotes online in minutes and change carriers with little friction. That’s why advertising is so relentless across the industry: retention is hard, and acquiring the next policyholder is expensive.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low. Insurers don’t face major supplier power in the classic sense.

Threat of Substitutes: Emerging. Over the long arc, autonomous vehicles, ride-sharing, and changing mobility patterns could reduce demand for personal auto insurance. The timing is uncertain, but the direction of pressure is clear.

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate. Regulation creates meaningful barriers, but digital distribution has lowered the practical cost of getting to customers. InsurTech startups have drawn significant venture capital, even if scaling profitably remains the hard part.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Framework

Scale Economies: Allstate has scale, but so do its biggest rivals. Scale helps in claims processing, analytics, and marketing, but it’s not a knockout punch when everyone at the top is huge.

Network Effects: Traditional insurance has very limited network effects. Arity is the exception: if more data improves prediction and better prediction attracts more users, a real network effect can form.

Counter-Positioning: This was the original sin of the agent era. Geico and Progressive were built to be cheaper by avoiding the agent-heavy structure, and Allstate couldn’t match them without detonating its own distribution model. Much of the last decade has been Allstate trying to unwind that trap.

Switching Costs: Low for single policies. Higher for bundled customers who have home and auto together, but still modest. Bundling helps, but it doesn’t lock people in the way a true switching-cost business would.

Brand: “You’re in Good Hands” is still one of the most recognizable slogans in American business, and it still signals trust. The open question is whether trust converts into pricing power in a world where the customer journey begins with a comparison site sorting by cheapest.

Cornered Resource: Historically, the cornered resource was the captive agent network—hard to replicate, locally embedded, and incredibly effective in its era. Today, the more interesting cornered resource is data, especially driving behavior data through Arity.

Process Power: This is the path to a durable edge. If Allstate can fuse sophisticated pricing, multi-channel distribution, and efficient claims handling into a system that runs better and cheaper over time, that operational “how” becomes difficult for competitors to copy quickly—even if they can copy features.

X. The Climate and Autonomous Driving Question: Existential Threats

Catastrophe Losses

Allstate’s transformation hasn’t been happening in a vacuum. At the exact moment the company was trying to modernize distribution and cut costs, the ground truth of the business was getting harsher: the weather.

In 2023, Allstate reported $5.64 billion in catastrophe losses—an 81% jump from the year before—driven largely by hurricanes and wildfires. This isn’t a one-off bad year. It’s part of a pattern where “catastrophe” is starting to look less like an exception and more like a recurring line item.

Zoom out and the trend is even clearer. In 2024, there were 27 separate weather and climate disasters in the U.S. that each caused at least $1 billion in damage, nearly matching 2023’s record. Together, they caused at least 568 direct or indirect fatalities and roughly $182.7 billion in total cost—making 2024 the fourth-costliest year on record.

For insurers, this is the uncomfortable shift: climate change isn’t a future scenario. It’s already rewriting the loss curve. In the first quarter of 2025, Allstate’s net income applicable to common shareholders fell more than 52% to $566 million, primarily because the company took a record $3.3 billion in gross catastrophe losses.

The industry’s response has been blunt: raise premiums, tighten underwriting, and, in some cases, stop writing new business in the riskiest places. For Allstate, that environment creates both danger and opening. The danger is obvious—misprice risk and you can light years of profit on fire. The opening is more subtle: in a world where weather volatility is the norm, the winners are the companies that can price accurately, move quickly, and not get trapped insuring yesterday’s reality at yesterday’s rates.

The Autonomous Vehicle Question

Then there’s the longer-term existential question that hangs over every auto insurer: what happens when cars stop crashing?

Autonomous vehicles have been “five years away” for a decade. But the direction of travel is still the same: more automation, fewer human-error accidents, and a gradual shift in how mobility works—especially as ride-sharing and fleet ownership expand. If and when autonomous driving becomes widespread, the personal auto insurance market won’t just get more competitive. It will get smaller.

Tom Wilson has been explicit about preparing for that kind of disruption, including pressure from driverless cars and services like Uber. And this is where Allstate’s push into Protection Services starts to look less like diversification for its own sake and more like future-proofing. If auto premiums eventually fall dramatically as accidents decline, Allstate needs other “peace of mind” products—identity protection, device protection, warranties, and similar offerings—to carry more of the company’s weight.

It’s a hedge against a future that may arrive slowly, and then all at once.

XI. Key Metrics for Investors

If you’re trying to figure out whether Allstate’s transformation is actually working, two metrics tell you more than almost anything else:

1. Combined Ratio (Underlying and Recorded)

The combined ratio is insurance’s clearest report card. It’s the loss ratio (claims paid divided by premiums earned) plus the expense ratio (operating expenses divided by premiums earned). Below 100% means the core insurance operation is profitable. Above 100% means it’s losing money on underwriting and relying on investment income to fill the gap.

In the third quarter of 2025, Allstate’s underlying auto combined ratio was 86.0. “Underlying” is the cleaner signal: it strips out catastrophes and prior-year reserve adjustments so you can see what the machine is doing in a normal operating environment. The recorded combined ratio, by contrast, includes those items—and in an era of severe weather, it can swing hard from quarter to quarter.

So investors should watch both. The underlying number tells you whether pricing discipline and operating efficiency are improving. The recorded number tells you what actually happened, including how much catastrophe risk showed up in the quarter.

2. Policies in Force Growth

For years, Allstate’s story was simple and painful: policy counts were shrinking. Now the company has moved back into growth. Policies increased 1.3%, as a 23.0% jump in new business was partly offset by lower customer retention.

That push-and-pull matters. Any insurer can grow quickly by cutting prices and writing risk aggressively—but that kind of growth usually shows up later as underwriting losses. The real test is sustainable growth: bringing in new customers and keeping existing ones, while still pricing for profit.

XII. Conclusion: Did They Turn the Ship in Time?

Allstate’s last two decades are a clean case study in the innovator’s dilemma—and the rare incumbent that eventually decided to fight it head-on.

For much of the 2000s and 2010s, the verdict looked grim. The captive-agent model that built Allstate into a giant also locked in a high-cost structure. As insurance shopping moved online and customers learned to treat auto coverage like a commodity, that structure became a handicap. Esurance was supposed to be the answer—a way to compete in direct without detonating the agent channel—but it functioned more like an expensive hedge. Market share kept sliding.

Then came the Transformative Growth plan in 2019, and with it, a different posture. Not “optimize the old machine,” but rebuild it. Retiring the Esurance brand. Buying National General to scale into independent agents. Exiting life insurance and annuities. Driving down the expense ratio. These weren’t cosmetic changes. They were the kind of moves that admit, quietly but unmistakably: the old playbook isn’t coming back.

And it did start to show up in the results. Profitability returned, underwriting improved, and the company stopped the long drift backward. Allstate posted an underwriting profit of $1.8 billion in 2024, a sharp reversal from the red ink of the year before. The question now isn’t whether Allstate can change. It’s whether it changed enough—and fast enough—to win against Progressive’s pricing machine, Geico’s lower-cost model, and State Farm’s sheer scale.

The most telling comparison might be the one Allstate can’t escape: Sears. At its peak in 2011, Sears had 2,705 stores. By December 2025, only five remained open in the U.S. Sears didn’t—or couldn’t—cannibalize its legacy model, and competitors that had no nostalgia for department stores finished the job. Allstate at least chose self-disruption over denial, even when it meant picking fights with its own channels.

Tom Wilson has now led the company for nearly two decades, and the transformation has carried his fingerprints: the National General deal, the sale of the life and annuity businesses, the shift to a distributed workforce, and the push toward simpler, more connected “protection” beyond traditional auto and home.

Whether the “Good Hands” brand stays strong in an era defined by algorithms, climate volatility, and the long arc toward autonomy is still the open question. But unlike Sears, Allstate has shown it’s willing to tear down what made it great in order to stay in the game.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music