TKO Group Holdings: The Ultimate Combat Sports Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Preview

The lights dim at T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas. Twenty thousand fans roar as two fighters step into the octagon. Meanwhile, 3,000 miles away at Madison Square Garden, pyrotechnics explode as a wrestler makes his entrance to deafening cheers. These two scenes—once representing entirely different worlds of combat entertainment—now share the same corporate DNA under TKO Group Holdings, a $21 billion colossus that has fundamentally reshaped the business of fighting as spectacle.

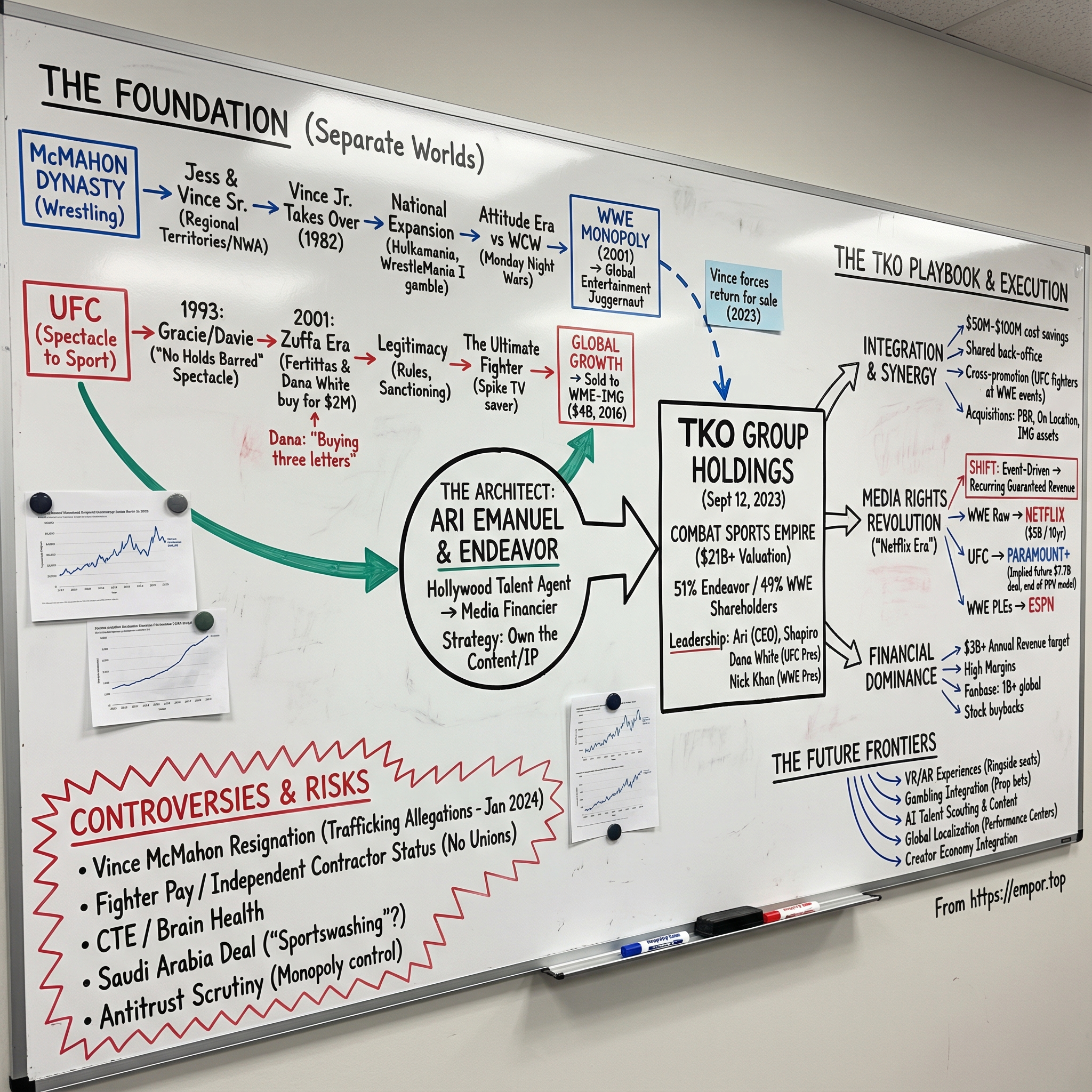

On September 12, 2023, something unprecedented happened in the world of sports entertainment. The Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), which had spent three decades legitimizing mixed martial arts from blood sport to mainstream athletic competition, merged with World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE), the theatrical wrestling empire that had transformed carnival sideshow into global entertainment phenomenon. The resulting entity, TKO Group Holdings, didn't just combine two companies—it united two philosophies of combat entertainment that had spent decades defining themselves in opposition to each other.

The architect of this unlikely marriage? Not a sports executive or entertainment mogul, but Hollywood's most aggressive talent agent turned media financier: Ari Emanuel. Through his company Endeavor, Emanuel orchestrated what industry observers called "the ultimate power play"—bringing together real fighting and scripted drama under one corporate umbrella, creating a combat sports monopoly that controls how the world watches people fight, whether for sport or spectacle.

This is a story that spans three generations of promoters, from smoke-filled wrestling arenas in the 1950s to streaming deals worth billions. It's about how Vince McMahon turned his father's regional wrestling territory into a global entertainment empire, how Dana White transformed cage fighting from political pariah to ESPN primetime, and how a Hollywood talent agency saw an opportunity to own the entire category of combat entertainment.

The numbers tell part of the story: 500+ live events annually reaching 1 billion households across 210 countries, generating nearly $3 billion in annual revenue. But the real story is about power consolidation in an era of fragmented media, the blurring lines between sport and entertainment, and what happens when you combine WWE's theatrical mastery with UFC's athletic legitimacy. As we'll see, TKO isn't just a merger—it's a bet on the future of live entertainment in a world where everything else can be time-shifted, skipped, or ignored.

II. The McMahon Wrestling Dynasty: Building the Foundation (1950s-1982)

In 1953, at Long Beach Memorial Hospital in New York, wrestling promoter Vincent James McMahon watched his father Jess collapse from exhaustion after another marathon booking session. The elder McMahon, then 71, had spent five decades promoting everything from boxing matches to Negro League baseball teams, but it was professional wrestling that captured his imagination in his final years. Jess anchored in Long Island, where he became the first McMahon to promote professional wrestling, at the Freeport Municipal Stadium, establishing a beachhead that would eventually grow into an empire worth billions.

The family's wrestling business started in 1915 when Jess McMahon started promoting wrestling events, but it wasn't until the television age that the McMahons would find their true calling. Vincent James McMahon was born on July 6, 1914, in Harlem, New York to Rose (née Davis) and Roderick James "Jess" McMahon, a successful boxing, wrestling and concert promoter. The younger McMahon inherited his father's promotional instincts but possessed something more: an understanding that television would transform wrestling from a regional curiosity into a national obsession.

McMahon saw the tremendous potential for growth that the professional wrestling industry had in the era following World War II, especially with the development of television and its need for new programming. Similar to boxing, wrestling took place primarily within a small ring and could be covered adequately by one or two cameras. While other promoters feared television would kill live attendance, Vince Sr. embraced it with characteristic bravado: "If this is the way television kills promoters, I'm going to die a very rich man".

In 1953, the pieces came together. Vincent J. McMahon Sr. and his father launched the Capitol Wrestling Corporation (CWC) and soon teamed with a long-time wrestler-turned-promoter named Joseph "Toots" Mondt. Mondt brought technical wrestling knowledge and innovation; McMahon brought business acumen and television connections. Together, they joined the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA), the loose confederation of regional promoters that governed professional wrestling across America.

The NWA operated like a cartel, with each promoter controlling their own territory—a gentleman's agreement that kept the peace and profits flowing. The sport had a more diffuse system, with different promotions "owning" different geographic territories. CWC extended its reach down to the mid-Atlantic. But McMahon and Mondt had bigger ambitions. Vincent J. McMahon and Toots Mondt were very successful and soon controlled approximately 70% of the NWA's booking power, largely due to their dominance in the heavily populated Northeastern United States.

The breaking point came in 1963, centered around one man: "Nature Boy" Buddy Rogers. With his bleached blonde hair and cocky swagger, Rogers was everything the conservative NWA establishment despised—and everything McMahon knew would draw television ratings. McMahon and Mondt had a dispute with the NWA over "Nature Boy" Buddy Rogers being booked to hold the NWA World Heavyweight Championship. Mondt and McMahon were not only promoters but also acted as his manager and were accused by other NWA promoters of withholding Rogers making defenses.

On January 24, 1963, the NWA forced the issue. Rogers lost the NWA World Heavyweight Championship to Lou Thesz in a one-fall match in Toronto, Ontario, Canada on January 24, 1963, which led to Mondt, McMahon, and the CWC leaving the NWA in protest, creating the World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF) in the process. The loss was controversial—Rogers had agreed to only a one-fall match instead of the traditional best-of-three, a detail McMahon would later claim invalidated the result.

Rather than accept the NWA's decision, McMahon and Mondt did something unprecedented: they walked away. In early 1963, the CWC pulled out of the NWA and transformed into the World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF), the precursor to current-day WWE, following a dispute over CWC wrestler Buddy Rogers being booked to lose the NWA World Heavyweight Championship to Lou Thesz. They crowned Rogers as their own world champion, claiming he had won a tournament in Rio de Janeiro—a tournament that never actually happened.

The formation of the WWWF represented more than just a business dispute. It was a declaration of independence from the old territorial system, a bet that one promotion could transcend regional boundaries. In the Spring of 1963, McMahon, Mondt and Willie Gilzenberg formed the World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF). Its purpose was to initially be, a governing body for the Northeastern companies.

Within a month of forming the WWWF, reality struck. Rogers, suffering from heart problems, dropped the championship to Bruno Sammartino on May 17, 1963, in a match that lasted less than a minute. Sammartino would hold that title for an astounding seven years, eight months, and one day—a record that still stands. The Italian strongman from Pittsburgh became the face of McMahon's operation, drawing sellout crowds at Madison Square Garden month after month.

Vince Sr. ran his territory differently than his competitors. The WWWF operated in a conservative manner compared to other wrestling promotions of its time; it ran its major arenas monthly rather than weekly or bi-weekly, usually featuring a babyface champion wrestling various heels in programs that consisted of one to three matches. He believed in slow builds, ethnic heroes for his diverse Northeast audience, and maintaining wrestling's legitimacy even as everyone knew it was predetermined.

But Vince Sr.'s conservatism would be tested by his own son. Vincent Kennedy McMahon had grown up estranged from his father, not even meeting him until age 12. Vincent Kennedy McMahon was born on August 24, 1945, in Pinehurst, North Carolina, to Victoria (née Hanner) and Vincent James McMahon, a wrestling promoter. Not long after his birth, his father left the family and took McMahon's older brother, Roderick Jr., with him. McMahon did not see his father again until he was 12 years old.

When they finally connected, young Vince became obsessed with the family business. He graduated from East Carolina University with a degree in business in 1968, and began his tenure in professional wrestling as a commentator for WWE (then called the World Wide Wrestling Federation or WWWF) for most of the 1970s. He worked as an announcer, learning the business from the ground up, all while harboring ambitions his father could never have imagined.

In 1982, the son approached the father with a proposal: he wanted to buy the company. Vince Sr., perhaps sensing his time was ending (he would die of cancer in 1984), agreed to sell—but on harsh terms. The deal between the two McMahons was a monthly payment basis, in which if a single payment was missed, ownership would revert to the elder McMahon and his business partners. Looking to seal the deal quickly, McMahon took several loans and deals with other promoters and the business partners (including the promise of a job for life) in order to take full ownership by May or June 1983 for an estimated total of roughly $1 million.

What Vince Sr. didn't fully grasp was his son's vision. The younger McMahon looked at the territorial system and saw not tradition to be respected, but inefficiency to be exploited. He would later tell Sports Illustrated: "Had my father known what I was going to do, he never would have sold his stock to me".

The generational handoff was complete. Three generations of McMahons had taken wrestling from carnival sideshows to Madison Square Garden. But it would be the third generation—the one who barely knew his father, who grew up outside the business, who saw it with fresh eyes—that would shatter every convention and transform regional wrestling into global entertainment. The foundation was set; the revolution was about to begin.

III. Vince McMahon's Revolution: From Regional to National (1982-2001)

On January 23, 1984, at Madison Square Garden, Vince McMahon Jr. stood backstage watching Hulk Hogan defeat The Iron Sheik for the WWF Championship. The crowd erupted in patriotic fervor as Hogan's theme music blared. McMahon knew at that moment he had found the face of his revolution. The WWF business expanded significantly on the shoulders of McMahon and his babyface hero Hulk Hogan for the next several years after defeating The Iron Sheik at Madison Square Garden on January 23, 1984.

But Hogan was more than just a wrestler—he was a mainstream celebrity, fresh off his role as Thunderlips in Rocky III. McMahon saw something his father never could have imagined: wrestling didn't need to hide what it was. It could embrace its theatrical nature and become something bigger—"sports entertainment."

When he purchased the WWF in 1982, professional wrestling was a business run by regional promotions. Various promoters understood that they would not invade each other's territories. This gentleman's agreement had kept the peace for decades, with each promoter content to run their fiefdom. McMahon looked at this arrangement and saw not tradition, but opportunity.

His expansion began methodically. He began expanding the company nationally by promoting in areas outside of the company's Northeast U.S. stomping grounds and by signing talent from other companies, such as the American Wrestling Association (AWA). McMahon would call promoters, offer to buy their television time slots, and when they refused, he'd go directly to the TV stations with briefcases full of cash. Stories regarding Vince McMahon's aggressive expansion in the mid-80s are legendary – whether it was leaving bags of money on promoters' desks through to buying TV deals out from under them, nothing got in his way.

The territorial promoters were furious, but powerless. Verne Gagne in Minnesota watched as McMahon poached his top star. Just prior to Hogan's title win against the Iron Sheik at Madison Square Garden in January of '84, Hulk was a member of the AWA roster. Hogan was arguably the AWA's most popular wrestler at that time and despite his ever-growing popularity, Verne Gagne refused to reward him with the AWA world title. Gagne was a stubborn man and believed a guy like Hogan with a non-amateur background wasn't worthy of being a world champion. Despite teasing Hogan winning the AWA title a couple of times, Gagne never pulled the trigger. Vince McMahon swooped in a took Hogan to the WWF and almost immediately awarded him the WWF's version of the world championship.

The most audacious move came in July 1984. McMahon had secretly purchased Georgia Championship Wrestling, gaining control of their coveted Saturday night slot on WTBS. In American professional wrestling, the term Black Saturday refers to Saturday, July 14, 1984, the day when Vince McMahon's World Wrestling Federation (WWF, now WWE) took over the timeslot on Superstation WTBS that had been home to Georgia Championship Wrestling (GCW) and its flagship weekly program, World Championship Wrestling, for twelve years. Fans tuned in expecting their usual Southern wrestling and instead got McMahon's New York product. The backlash was immediate and severe, but the message was clear: no territory was safe.

But McMahon's true genius wasn't in destruction—it was in creation. He understood that to go national, wrestling needed to transcend its traditional audience. Enter the Rock 'n' Wrestling Connection, a marriage of professional wrestling and MTV culture that would fundamentally change both industries.

The unlikely catalyst was a chance meeting on a plane between pop star Cyndi Lauper and wrestling manager Captain Lou Albano. Cyndi Lauper and Lou Albano connected on a flight to Puerto Rico in the early 80's, Cyndi's manager was a huge WWE fan and they started casting Lou as Cyndi's "dad" in her music videos. Albano appeared in Lauper's "Girls Just Want to Have Fun" video, creating an organic crossover between wrestling and pop music that McMahon quickly exploited.

For the first WrestleMania, McMahon began cross-promoting with MTV, which aired two wrestling specials. The first one was The Brawl to End It All on July 23, 1984, in which a match from a live Madison Square Garden broadcast was shown on MTV. Wendi Richter, allied with Cyndi Lauper, defeated The Fabulous Moolah, backed by Lou Albano, to win the WWF Women's Championship on the card. At The War to Settle the Score on February 18, 1985, Leilani Kai, accompanied by Moolah, defeated Richter, again accompanied by Lauper, to win the Women's Championship.

These MTV specials weren't just wrestling shows—they were cultural events that introduced the WWF to an entirely new demographic. Young people who had never watched wrestling were suddenly invested in the feuds and personalities. The WWF was no longer regional wrestling; it was becoming a national entertainment brand.

Everything built toward March 31, 1985: WrestleMania, McMahon's ultimate gamble. The event wasn't just ambitious—it was potentially company-ending. McMahon had mortgaged everything, possibly including his house, to fund the closed-circuit television production. With the heightened expense of promoting an event of this magnitude, the WWF was flirting with bankruptcy (some say that Vince had to take a second or third mortgage on his house just to free up the funds he needed). The execution of Wrestlemania became a huge gamble, and failure could have easily spelled the end of the company as we knew it.

The celebrity integration was unprecedented. Celebrity guests included former heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali as referee, baseball player/manager Billy Martin as ring announcer, and musician-actor Liberace as timekeeper. But the masterstroke was Mr. T, the star of The A-Team and Rocky III, teaming with Hulk Hogan in the main event. "The whole WWE universe rested on his back, and we didn't even know it. . . this whole company was on Mr. T's back," Hogan told WWE.com.

It was the inaugural WrestleMania that took place on March 31, 1985, at Madison Square Garden in New York City, New York. The attendance for the event was 19,121. The event was seen by over one million viewers through a closed-circuit television, making it the largest PPV showing of a wrestling event on closed-circuit television in the United States at the time.

WrestleMania's success changed everything. The territorial system was effectively dead. Within two years, McMahon had either bought out or driven out of business most of his major competitors. The 1980s "Wrestling Boom" peaked with the WrestleMania III pay-per-view at the Pontiac Silverdome in 1987, which set an attendance record of 93,173 for the WWF for 29 years until 2016.

But success brought scrutiny. In 1993, McMahon faced his greatest challenge yet when the federal government indicted him on charges of distributing steroids to wrestlers. In 1993, Vince McMahon found himself on trial for distribution of steroids to his talent in the United States vs. Vince McMahon case that shook the foundation of the WWF promotion. The trial threatened to destroy everything McMahon had built, but in 1994, he was acquitted of all charges.

The steroid trial forced a shift in the WWF's presentation. The larger-than-life musclemen gave way to smaller, more athletic performers. Business declined through the mid-1990s as a new competitor emerged: Ted Turner's World Championship Wrestling, built on the foundation of the old Jim Crockett Promotions that McMahon had failed to fully destroy.

By 1996, WCW was beating WWF in the television ratings, led by former WWF stars like Hulk Hogan and Randy Savage. The Monday Night Wars had begun, with both companies airing head-to-head on Monday nights. For 84 consecutive weeks, WCW's Monday Nitro defeated WWF's Monday Night Raw in the ratings. McMahon was losing the war he had started.

The solution came from desperation and innovation. As the Monday Night War continued between Raw Is War and WCW's Nitro, the WWF would transform itself from a family-friendly product into a more adult-oriented product, known as the Attitude Era. The era was spearheaded by WWF VP Shane McMahon (son of owner Vince McMahon) and head writer Vince Russo. 1997 ended with McMahon facing real-life controversy following Bret Hart's controversial departure from the company, dubbed as the Montreal Screwjob. This proved to be one of several founding factors in the launch of the Attitude Era as well as the creation of McMahon's on-screen character, "Mr. McMahon".

McMahon transformed himself into television's greatest villain, the evil "Mr. McMahon" character who feuded with working-class hero "Stone Cold" Steve Austin. The product became edgier, more violent, more sexual. Parents were horrified; teenagers were enthralled. By 1998, the WWF had reclaimed the ratings crown.

The end came suddenly. McMahon later came out victorious against Ted Turner's World Championship Wrestling (WCW) in the television ratings in the Monday Night War after an initial 84-week television ratings loss to WCW and afterward acquired the fading WCW from Turner Broadcasting System on March 23, 2001, with an end to the Monday Night War. On April 1, 2001, Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW) filed for bankruptcy leaving WWF as the last major wrestling promotion at that time. McMahon later acquired the assets of ECW on January 28, 2003.

For less than $5 million, McMahon bought his only remaining competition. The boy who barely knew his father had completed the conquest his grandfather could never have imagined. Professional wrestling in America was now a monopoly, and Vince McMahon was its emperor.

The journey from 1982 to 2001 was more than a business expansion—it was a complete reimagining of what wrestling could be. McMahon had taken a regional territory and transformed it into a billion-dollar global entertainment conglomerate. He had survived federal prosecution, defeated a billionaire competitor, and fundamentally changed how America consumed popular culture. The revolution was complete, but as we would soon see, maintaining an empire would prove just as challenging as building one.

IV. The UFC Story: From Spectacle to Sport (1993-2016)

November 12, 1993. McNichols Sports Arena, Denver, Colorado. A skinny Brazilian in a white gi stands across from a Dutch kickboxer with a ponytail. The crowd of 7,800 doesn't know what to expect. Neither, really, do the fighters. This is UFC 1, and in 26 seconds, a teeth-flying head kick to a downed opponent will announce the arrival of a new kind of violence to American television screens.

The Ultimate Fighting Championship was founded in 1993 by Rorion Gracie, business executive Art Davie, and the Semaphore Entertainment Group (SEG). But the genesis went deeper than a business partnership. Art Davie proposed an eight-man single-elimination tournament called "War of the Worlds" to John Milius and Rorion Gracie. This idea was inspired by the "Gracies in Action" video series, produced by the Gracie family of Brazil, which showcased Gracie jiu-jitsu students defeating martial artists from various disciplines such as karate, kung fu, and kickboxing in Vale Tudo matches. The tournament aimed to feature martial artists from different disciplines competing in no-holds-barred combat to determine the best martial art, replicating the excitement Davie saw in the videos.

Davie was a salesman with a dream; Rorion was a Brazilian jiu-jitsu master with a legacy to protect. In 1978, Rorion Gracie moved to Southern California where he worked as an extra in movies and television. Attempting to spread Jiu-Jitsu culture, he laid some mats in his garage in Hermosa Beach and invited people he met to try the sport. The Gracies had been proving their art's superiority in Brazil for decades through "Vale Tudo" (anything goes) matches. Now Rorion wanted to showcase it to America.

The problem was finding fighters. Davie searched far and wide for recognizable martial arts superstars like kickboxing champion Ernesto Hoost, only to be turned down over and over again. Fighters were just too used to their own set of rules, more comfortable in the world they knew than the unknown UFC represented at the time. Established martial artists took one look at the concept—no rules, no weight classes, no time limits—and ran the other way.

Rorion said he picked Royce to represent the family's art because of his skinnier and smaller frame, to show how a small person can defeat a bigger opponent using jiu-jitsu. It was a calculated choice. Rickson, the family champion, would have dominated too easily. On top of that, Rorion found out that Rickson had stolen two students from the Gracie academy and was teaching them over his garage. So it came down to money. Family politics and marketing strategy aligned: Royce, at 175 pounds, would be David to everyone else's Goliath.

WOW Promotions and SEG produced the first event, later retroactively named UFC 1, at the McNichols Sports Arena in Denver, Colorado, on November 12, 1993. The production was chaotic. The octagon—that now-iconic eight-sided cage—was a last-minute invention. Rorion Gracie and Art Davie were opposed to using a traditional roped ring for their event, fearing that fighters could escape through the ropes during grappling or fall off and injure themselves, as evidenced by old Vale Tudo footage. SEG's executives agreed and also wanted to visually distinguish their event from professional boxing and wrestling. Various ideas were considered, including a roped ring surrounded by netting, a moat with alligators, a raised platform with a razor-wire fence, electrified fencing, men in togas, and netting that could be lowered from the ceiling by a pulley. Ultimately, Jason Cusson designed an arena with eight sides surrounded by a chain-link fence, creating the trademarked Octagon, which became the signature setting for the UFC.

The first fight set the tone. Sumo wrestler Teila Tuli charged kickboxer Gerard Gordeau. Within seconds, Gordeau's kick sent Tuli's teeth flying—literally flying—into the crowd. In the first fight in UFC history, Dutch kickboxer Gerard Gordeau sent Hawaiian sumo Telia Tuli's teeth flying with a kick, and Gordeau ultimately landed in the hospital with an infection from the teeth fragments which ended up embedded in his foot. The referee, not knowing what else to do, stopped the fight. The crowd was stunned. This wasn't wrestling. This wasn't boxing. This was something else entirely.

Royce Gracie methodically worked through the bracket. In his first match, Gracie defeated journeyman boxer Art Jimmerson. He tackled him to the ground using a baiana (morote-gari or double-leg) and obtained the dominant "mounted" position. Mounted and with only one free arm, Jimmerson conceded defeat. Against Ken Shamrock in the semifinals, Royce showed the world what ground fighting could do, securing a rear naked choke on a man who outweighed him by 40 pounds. In the finals, he choked out Gordeau, refusing to let go even after the tap—a message that Brazilian jiu-jitsu had arrived.

The event was a modest success on pay-per-view, but politically, it was a disaster. Senator John McCain saw the replays and launched a crusade, calling it "human cockfighting". State after state banned the sport. Cable companies dropped it. By 1997, the UFC was essentially underground, relegated to Indian casinos and states without athletic commissions. SEG, the ownership group, was hemorrhaging money.

The sport that had started as spectacle was dying as spectacle. But it would be reborn as sport.

Enter the casino money. After the long battle to secure sanctioning, SEG stood on the brink of bankruptcy, when Station Casinos executives Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta and their business partner Dana White approached them in 2000, with an offer to purchase the UFC. A month later, in January 2001, the Fertittas bought the UFC for $2 million and created Zuffa, LLC as the parent entity controlling the UFC.

Dana White's origin story has become legend. A Boston kid who moved to Vegas, failed as a boxer, succeeded as a boxercise instructor to wealthy housewives, and became friends with Lorenzo Fertitta when they were both at Bishop Gorman High School. When White heard the UFC was for sale, he called Lorenzo. In 2001, Dana White was instrumental in persuading the Fertitta brothers, who were already prominent businesspeople in Las Vegas, to purchase the UFC. They acquired the UFC for $2 million and eventually transformed it into the world's premier MMA organization, acquiring rival promotions like Pride FC, WEC, and Strikeforce.

What they bought was essentially nothing. White said that when he and the Fertittas acquired the UFC, all they received was the brand name "UFC" and an old octagon. The previous owners had stripped the company's assets to avoid bankruptcy, so much so that the UFC.com website had been sold to a company named "User Friendly Computers". "I had my attorneys tell me that I was crazy because I wasn't buying anything. I was paying $2 million and they were saying 'What are you getting?'" Lorenzo Fertitta revealed to Fighters Only magazine, recalling the lack of assets he acquired in the purchase. "And I said 'What you don't understand is I'm getting the most valuable thing that I could possibly have, which is those three letters: UFC. That is what's going to make this thing work. Everybody knows that brand, whether they like it or they don't like it, they react to it'".

The Fertittas had something SEG never did: political connections and deep pockets. With ties to the Nevada State Athletic Commission (Lorenzo Fertitta was a former member of the NSAC), Zuffa secured sanctioning in Nevada in 2001. They worked with athletic commissions to create unified rules: rounds, time limits, weight classes, forbidden techniques. The blood sport was becoming a legitimate sport.

But legitimacy didn't equal profitability. The UFC did not immediately have success after the Zuffa takeover, and by 2004 the Fertittas had invested over $40 million into the company without attaining significant growth or reaching profitability. The Fertittas were bleeding money—$44 million in the red by some accounts. Dana White had an idea: a reality show.

White, alongside the Fertittas and television producer Craig Piligian, developed the idea of an MMA-based reality series, The Ultimate Fighter, as an attempt to create interest in the sport. They pitched it to everyone. Nobody wanted it. Finally, Spike TV agreed, but with conditions: the UFC had to pay for production. It was their last roll of the dice.

The Ultimate Fighter premiered in January 2005. The season finale, featuring Forrest Griffin vs. Stephan Bonnar in what many call the most important fight in UFC history, drew massive ratings. The fight was a bloody war that had viewers calling their friends, telling them to turn on the TV immediately. The sport had found its mainstream moment.

From there, growth was exponential. They acquired rival promotions: Pride FC from Japan in 2007, giving them stars like Rampage Jackson and Anderson Silva. WEC in 2010, bringing in lighter weight classes. Strikeforce in 2011, adding Ronda Rousey and Daniel Cormier. Each acquisition eliminated competition and added talent. The UFC strategy was simple: be the only game in town.

By 2016, the Fertittas had built a global empire. The UFC was in 150 countries, had a roster of over 500 fighters, and was pulling in hundreds of millions in revenue. The sport that politicians had tried to ban was now sanctioned in all 50 states, including New York, which had held out until 2016.

As first reported by TMZ, the Ultimate Fighting Championship was sold for $4 billion to talent agency WME-IMG in the single biggest transaction in sports history. Zuffa, led by siblings Lorenzo and Frank Fertitta, purchased the failing fight promotion for just $2 million in 2001. Under their steady hand, the company became a worldwide phenomenon, spreading the gospel of combat to fans in more than 150 countries.

The journey from 1993 to 2016 was one of transformation. What began as a spectacle to determine which martial art was superior became a sport that combined them all. The "no holds barred" marketing gave way to "mixed martial arts." The human cockfighting became "the fastest growing sport in the world." Royce Gracie's gi was replaced by board shorts and four-ounce gloves. The carnival became corporate.

But through all the changes, one thing remained constant: people wanted to know who would win in a real fight. That primal question, the one that Art Davie and Rorion Gracie set out to answer in a Denver arena in 1993, still drove millions of viewers to watch two people step into an octagon and find out. The Gracies had wanted to prove their martial art was the best; they ended up creating a new one entirely.

V. Endeavor's Master Plan: The Path to TKO (2016-2023)

Ari Emanuel doesn't look like a typical Hollywood power broker. At 5'7" with a shaved head and intense eyes, he looks more like a UFC fighter than the CEO of a talent agency. But that fighter's mentality—inherited from his Israeli father who was in the Irgun resistance—would prove essential to transforming a boutique talent agency into an entertainment empire worth billions.

Endeavor is headed by CEO Ari Emanuel and executive chairman Patrick Whitesell. Emanuel's journey to becoming one of the most powerful men in entertainment began in 1995 when he left ICM to start Endeavor with three other agents. Prior to founding Endeavor, Emanuel was a partner at InterTalent and senior agent at ICM Partners (ICM). The agency grew steadily, but Emanuel had bigger ambitions than just representing actors.

The transformation began in 2009. William Morris Agency (WMA) and the Endeavor Talent Agency announced that they were forming William Morris Endeavor, or "WME". Endeavor executives Ari Emanuel and Patrick Whitesell were widely seen as the architects of the merger and quickly became the Co-CEOs of WME. It was a bold move—merging with one of Hollywood's oldest agencies—but it was just the beginning.

Emanuel's philosophy was different from traditional Hollywood thinking. In 2011, Emanuel was quoted in a Financial Times profile about the company saying, "We built a culture where people are rewarded for taking risks." That risk-taking culture would drive a series of increasingly audacious acquisitions.

The first major move came in 2013. On December 18, 2013, WME and Silver Lake announced the acquisition of IMG for $2.4 billion. WME's Ari Emanuel and Patrick Whitesell took over as co-CEOs. IMG wasn't just any company—it was the global leader in sports marketing, fashion events, and athlete representation. Suddenly, WME wasn't just representing movie stars; it was managing Wimbledon, New York Fashion Week, and the careers of the world's top athletes.

But Emanuel's masterpiece acquisition came in 2016. On July 9, 2016, Zuffa, LLC, the parent company of Ultimate Fighting Championship, was sold to a group led by WME-IMG, its owner Silver Lake Partners, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, and MSD Capital, for $4.025 billion, the largest-ever acquisition in the sports industry. The deal was audacious even by Emanuel's standards. A talent agency buying a sports league? It had never been done before.

WME/IMG has represented the UFC for more than a decade as well as UFC stars including Ronda Rousey, giving it a ringside seat to the growth of the organization's appeal in recent years. WME/IMG co-CEO Emanuel has developed a strong relationship with UFC president White, which surely played a role in driving the deal. Emanuel saw what others didn't: content was king, and owning content was better than just representing the people who made it.

The UFC acquisition wasn't without challenges. The sport was still controversial, still violent, still struggling with its image. But Emanuel believed in the power of live sports in an era of streaming and time-shifting. "We've been fortunate over the years to represent UFC and a number of its remarkable athletes," said WME/IMG co-CEOs Ariel Emanuel and Patrick Whitesell. "It's been exciting to watch the organization's incredible growth over the last decade under the leadership of the Fertitta brothers, Dana White and their dedicated team. We're now committed to pursuing new opportunities for UFC and its talented athletes to ensure the sport's continued growth and success on a global scale."

Emanuel kept Dana White as president, understanding that White's authenticity and connection to fans was irreplaceable. UFC president Dana White will continue in his role after the deal is completed. UFC chairman-CEO Lorenzo Fertitta will step down from day-to-day operations, but Fertitta and his brother, Frank Fertitta III, will retain a passive minority interest in UFC.

The strategy was working. Under Endeavor's ownership, the UFC continued to grow, securing bigger media deals and expanding internationally. But Emanuel wasn't done. He took Endeavor public in 2021, finally achieving the IPO that had been pulled in 2019 due to market conditions. The parent company of WME, IMG and a range of content assets yanked its previous IPO at the 11th hour in 2019. Market conditions and other factors would have stymied its chances, the company concluded. The IPO market overall has rebounded strongly in the meantime, and Endeavor also resolved a protracted struggle with the Writers Guild of America over packaging. Endeavor led a group of private investors in a $4 billion acquisition of the UFC in 2016.

Meanwhile, in Stanford, Connecticut, another empire was facing its own succession crisis. Vince McMahon had built WWE into a global entertainment juggernaut, but by 2022, at age 76, scandal was catching up with him. The controlling shareholder of WWE stepped down as CEO and chairman of the board last July amid a scandal over sexual misconduct and board investigation over payouts to women. His daughter Stephanie and former CAA agent Nick Khan took over as co-CEOs.

But McMahon wasn't ready to let go. On January 6, 2023, he shocked the wrestling world. Former WWE CEO Vince McMahon is planning a return to the pro-wrestling promotion in order to sell off the company. Former WWE CEO Vince McMahon is planning a return to the pro-wrestling promotion in order to explore a sale of the company. Using his controlling stake, he forced his way back onto the board. As first reported by the Wall Street Journal, McMahon has informed WWE he will be electing himself to the board, as well as Michelle Wilson and George Barrios, former WWE co-presidents and directors. McMahon, who retains majority voting power at WWE through his shares in the company, plans to be named executive chairman, pending board approval, which was not given during a previous move made to reinstate McMahon.

McMahon's message was clear: "WWE is entering a critical juncture in its history with the upcoming media rights negotiations coinciding with increased industry-wide demand for quality content and live events and with more companies seeking to own the intellectual property on their platforms. The only way for WWE to fully capitalize on this opportunity is for me to return as Executive Chairman and support the management team in the negotiations for our media rights and to combine that with a review of strategic alternatives."

The wrestling world was stunned. According to the Wall Street Journal today, McMahon expressed a desire to return to the company in a letter to the board last month and said he would refuse to support or approve any media-rights deal or sale unless he has direct involvement as executive chairman. He said he received bad advice from people close to him last year to step down, the WSJ reported, citing people familiar with his comments.

Within days, the drama intensified. Just days after announcing his return, McMahon's daughter, Stephanie McMahon, resigned as co-CEO and chairman of the board of WWE, leaving former talent agency exec Nick Khan as the sole CEO. McMahon, who was simultaneously named chairman of the board, had said just days before that "WWE has an exceptional management team in place, and I do not intend for my return to have any impact on their roles, duties or responsibilities."

Emanuel saw opportunity in the chaos. He had been circling WWE for years, understanding that combining it with UFC would create unprecedented synergies. Both were live entertainment properties. Both appealed to similar demographics. Both were perfect for the streaming age where live content commanded premium prices.

The negotiations were complex. McMahon wanted to maintain some control. Other bidders were interested—Comcast, Disney, Netflix. But Emanuel had advantages. He understood talent and personalities. He wouldn't be scared off by McMahon's baggage. Most importantly, he could offer something unique: a merger, not just an acquisition.

On April 3, 2023, the deal was announced. Endeavor Group Holdings and sports entertainment powerhouse WWE made things official on Monday, unveiling a definitive agreement to form a new, publicly listed company consisting of two "iconic, complementary" global sports and entertainment brands: UFC and WWE. Endeavor will hold a 51 percent controlling interest in the new company, with existing WWE shareholders owning a 49 percent interest. The new company will be led by Endeavor CEO Ari Emanuel as CEO, who will also continue in the same role at the remaining Endeavor business, which includes talent agency WME and the likes of IMG. WWE executive chairman and majority shareholder Vince McMahon will serve as executive chairman of the newly created firm, while Mark Shapiro will be president and chief operating officer of both Endeavor and the new company. Dana White will continue in his role as president of UFC, with WWE CEO Nick Khan holding the same president title as White but at WWE.

Emanuel's thesis was simple but powerful: "This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to bring together two leading pureplay sports and entertainment companies," says Endeavor CEO Ari Emanuel of the new "$21 billion-plus" juggernaut. The synergies were obvious. Endeavor, which also owns WME-IMG, saw its top execs keen to argue purchasing the UFC in 2016 for $4 billion as part of an aggressive push into content ownership had paid off well and investors could expect the same as WWE was now absorbed into the mix. Lublin predicted the UFC and WWE merger will secure $50 million to $100 million in annual operating synergies, in part by following the earlier acquisition model for UFC, which delivered $70 million in cost synergies and similarly integrating WWE into Endeavor's global infrastructure.

The formation of TKO Group Holdings on September 12, 2023, represented more than just a business combination. Established on September 12, 2023, the public company was formed by a merger between Endeavor subsidiary Zuffa—the parent company of mixed martial arts promotion Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC)—and the professional wrestling promotion World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE). TKO is led by CEO Ari Emanuel and president Mark Shapiro, both of Endeavor; Dana White and Nick Khan retained their roles as CEOs of UFC and WWE respectively upon the merger, while WWE co-founder Vince McMahon served as an executive chairman until resigning from the company in January 2024 amid a sex trafficking scandal.

The merger was historic for another reason: The merger marked the first time that WWE has not been solely and primarily majority-controlled by the McMahon family, which founded the company and owned it for over 70 years. Three generations of McMahon control had ended, replaced by a Hollywood talent agent who saw the future of entertainment differently.

At the close of the deal, Endeavor held a 51% stake in TKO Group Holdings, with WWE's shareholders having a 49% stake, valuing WWE at $9.3 billion. This marked the first time that WWE had not been majority-controlled by members of the McMahon family. The valuation was stunning—WWE alone was worth more than double what Endeavor had paid for the entire UFC just seven years earlier.

Emanuel's vision was clear: When the merger was first announced in April 2023, Emanuel stated that it would "bring together two leading pureplay sports and entertainment companies" and provide "significant operating synergies". McMahon stated that "family businesses have to evolve for all the right reasons", and that "given the incredible work that Ari and Endeavor have done to grow the UFC brand — nearly doubling its revenue over the past seven years — and the immense success we've already had in partnering with their team on a number of ventures, I believe that this is without a doubt the best outcome for our shareholders and other stakeholders."

The path from talent agency to combat sports empire had been unconventional, but that was Emanuel's style. Where others saw conflict between real fighting and scripted entertainment, he saw complementary assets. Where others saw reputational risk in McMahon's scandals, he saw a motivated seller. Where others saw separate industries, he saw one unified market for combat entertainment. The master plan had worked. The only question now was what Emanuel would do with his new empire.

VI. The TKO Playbook: Integration and Expansion (2023-Present)

The first 100 days of TKO Group Holdings proved Emanuel's thesis correct. The marriage of UFC and WWE is complete: Endeavor and WWE announced the close of their deal to create TKO Group Holdings, merging the wrestling entertainment company and MMA leader UFC. The hope is that by tag-teaming as a unified force, UFC and WWE together will become stronger than they could be separately.

The integration began immediately. In addition Emanuel serving as TKO's CEO, the new company's management team comprises Mark Shapiro as president and COO (who continues as president and chief operating officer of Endeavor); CFO Andrew Schleimer (previously UFC's chief financial officer); and chief legal officer Seth Krauss, who continues as chief legal officer of Endeavor. Dana White is now CEO of UFC, and Lawrence Epstein remains senior executive VP and COO of UFC. Nick Khan continues at WWE in the role of president (after serving as CEO) and will have a seat on TKO's board.

The leadership structure was carefully designed to maintain operational independence while capturing synergies. White and Khan ran their divisions like CEOs of separate companies, maintaining the distinct cultures and fan bases. But behind the scenes, the integration machine was humming. According to Endeavor, the TKO deal will result in an estimated $50 million to $100 million in annualized run-rate cost synergies, including by migrating WWE to Endeavor's back-office infrastructure. The cost-savings target presumably will also include layoffs at UFC and WWE but the companies have not announced details about job cuts at this point.

The synergies weren't just about cutting costs. In addition, TKO will "leverage Endeavor's expertise" in areas including domestic and international media rights, ticket sales and yield optimization, event operations, global partnerships, licensing and premium hospitality "to drive revenue growth," the companies said. TKO's combined sponsorship team could now offer brands access to both UFC's male-skewing, 18-34 demographic and WWE's broader family audience. A single advertiser could reach fight fans on Saturday nights and wrestling families on Monday nights.

The numbers validated the strategy quickly. TKO (WWE and UFC) had a revenue of $2.804 billion for 2024 and a net income of $6.4 million. For the fourth quarter of 2024, TKO reports a revenue of $642.2 million and a net income of $47.5 million. WWE had a revenue of $1.398 billion in 2024 while UFC's revenue was $1.406 billion. The company was firing on all cylinders, with Adjusted EBITDA increased 55%, or $442.1 million, to $1.251 billion, due to an increase of $518.1 million at WWE and an increase of $45.3 million at UFC, partially offset by an increase of $121.3 million in corporate expenses.

But TKO wasn't just about combining two existing properties. Emanuel had bigger ambitions. In October 2024, the expansion accelerated dramatically. On October 23, 2024, it was announced that TKO Group would acquire several businesses from Endeavor, including sports and event management firm IMG (aside from "businesses associated with the IMG brand in licensing, models, and tennis representation, nor IMG's full events portfolio"), On Location Experiences (a luxury hospitality agency focused on major sporting events), and Professional Bull Riders (PBR), for $3.25 billion in an all-stock deal expected to close in 2025. Shapiro stated that Silver Lake Partners had requested the divestment of certain Endeavor assets as part of its planned buyout of the company, and that Endeavor had approached TKO Group with an offer. He explained that TKO was interested in league ownership and "businesses that can power our current sports ecosystem", while the company stated that it would "[expand] TKO's operational footprint in the fast-growing premium sports market and enables direct participation in the upside from partner leagues and events".

The acquisition of On Location was particularly strategic. The company specialized in premium hospitality packages for major sporting events—Super Bowls, Olympics, World Cups. Now TKO could offer VIP experiences not just at WrestleMania and UFC pay-per-views, but across the entire sports ecosystem. IMG's inclusion brought the world's premier sports marketing agency into the fold, creating opportunities for athlete representation and event management that went far beyond fighting.

Professional Bull Riders might have seemed like an odd addition, but it fit perfectly into TKO's vision. PBR had a passionate fanbase, toured similar markets, and appealed to overlapping demographics with both UFC and WWE. More importantly, it was another form of live combat entertainment—man versus beast instead of man versus man.

The international expansion was aggressive. In 2025, TKO announced plans to form a boxing promotion known as Zuffa Boxing, and would acquire other sports and entertainment assets from Endeavor as part of its sale to Silver Lake Partners, including Professional Bull Riders (PBR), hospitality agency On Location Experiences, and assets from IMG. The launch of Zuffa Boxing represented TKO's attempt to consolidate the fragmented boxing industry, leveraging UFC's promotional expertise and WWE's production capabilities.

Cross-promotion opportunities emerged organically. UFC fighters appeared at WWE events. WWE superstars sat cageside at UFC fights. The companies co-promoted "TKO Takeover" events that featured all their properties. Brock Lesnar, who had been both UFC Heavyweight Champion and WWE Champion, became the symbol of the merger—a living bridge between the two worlds.

The operational integration went deeper than most realized. UFC adopted WWE's merchandise strategies, dramatically expanding their product lines. WWE learned from UFC's digital engagement tactics, improving their social media presence. Both benefited from shared data on fan behavior, optimizing everything from ticket pricing to concession sales.

The corporate structure reflected the ambitions. TKO together boasts more than 1 billion fans around the world, reaching viewers in 180 countries, and producing more than 350 annual live events. These weren't just numbers—they represented leverage in every negotiation, from media rights to venue deals to sponsorship agreements.

One unexpected benefit was talent development. WWE's Performance Center in Orlando became a resource for UFC fighters working on their promotional skills. UFC's training facilities helped WWE wrestlers improve their legitimate fighting techniques, making their performances more realistic. The cross-pollination created better athletes and entertainers on both sides.

The regulatory environment proved favorable. Unlike traditional sports leagues, neither UFC nor WWE had players' unions or collective bargaining agreements. Fighters and wrestlers remained independent contractors, giving TKO maximum flexibility in talent management and cost control. This structure, controversial as it was, enabled rapid decision-making and integration.

Leadership dynamics evolved as the integration progressed. While Emanuel remained the strategic visionary, Shapiro emerged as the operational architect. His experience running IMG gave him unique insights into managing diverse sports properties. "TKO delivered record financial performance in 2024 at both UFC and WWE, reflecting the strength of our IP, the dynamic audiences we serve, and the industry-best team of people we've assembled," said Ariel Emanuel, Executive Chair and CEO of TKO. "In the year ahead, we will be focused on securing long-term U.S. domestic media rights agreements for UFC as well as WWE's Premium Live Events; integrating IMG, On Location and Professional Bull Riders into our portfolio; creating even more compelling live events; and executing our robust capital return program for shareholders".

The market responded enthusiastically. Looking ahead, revenue is forecast to grow 12% p.a. on average during the next 3 years, compared to a 9.3% growth forecast for the Entertainment industry in the US. TKO was outperforming not just its peers but the entire entertainment sector.

The integration wasn't without challenges. Cultural differences persisted—UFC's authenticity-obsessed culture sometimes clashed with WWE's theatrical traditions. Some UFC purists resented the association with "fake" wrestling. Some WWE fans worried their product would become too violent, too real. But the financial results silenced most critics.

By early 2025, TKO had become something unprecedented: a vertically integrated combat sports conglomerate that controlled how the world watched people fight, whether real or scripted. The playbook—operational integration, international expansion, strategic acquisitions, cross-promotion—had worked better than even Emanuel had imagined. The only question now was how much bigger TKO could grow before it ran out of combat sports to consolidate.

VII. Media Rights & The Netflix Era

VII. Media Rights & The Netflix Era

January 6, 2025. Intuit Dome, Los Angeles. The pyro explodes, the crowd roars, and for the first time in 31 years, Monday Night Raw isn't on cable television. This marks a major programming shift as Raw leaves linear television for the first time since its inception 31 years ago. It's streaming on Netflix, and the wrestling world has officially entered a new era.

The Netflix deal wasn't just transformative—it was seismic. World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) just scored a 10-year, $5 billion Netflix deal beginning Jan. 2025, making the deal valued at $500 million per year for 10 years, or a whopping $5 billion commitment by the streamer. For context, WWE's current five-year deal for US rights to "Raw" with NBCUniversal is worth approximately $250 million-$260 million per year. Netflix had essentially doubled the value overnight.

The deal structure revealed Netflix's commitment to live sports. Netflix has the option to opt out after the initial five years and to extend for an additional 10 years. But more importantly, as part of the agreement, Netflix will also become the home for all WWE shows and specials outside the U.S. as available, inclusive of Raw and WWE's other weekly shows – SmackDown and NXT – as well as the company's Premium Live Events, including WrestleMania, SummerSlam and Royal Rumble.

The debut was a resounding success. Netflix (NYSE: NFLX) and WWE®, part of TKO Group Holdings (NYSE: TKO) today announced that the debut episode of RAW on Netflix got off to a strong start, with the Monday night program capturing 4.9M Live+1 views* globally. The inaugural event on Netflix averaged 2.6 million households (Live+SD) in the US, according to VideoAmp, which is 116% higher than RAW's average 2024 US audience of 1.2 million households, and higher than any other Monday Night RAW broadcast in the past five years.

Mark Shapiro captured the significance: "It marries the can't-miss WWE product with Netflix's extraordinary global reach and locks in significant and predictable economics for many years." The deal "fundamentally alters and strengthens the media landscape dramatically expands the reach of WWE and brings weekly live appointment viewing to Netflix."

But WWE wasn't putting all its eggs in one basket. While Netflix got Raw and international rights, ESPN's new direct-to-consumer service will include all of WWE's live premium events beginning in 2026; ESPN will also simulcast select events on its linear networks. ESPN is paying TKO's WWE an average of $325 million per year for five years. This represented another massive increase, as NBCUniversal's Peacock had previously paid $180 million per year over five years for the package.

The ESPN deal was strategic for different reasons. "We are proud to reinforce the 'E' in ESPN at such an exciting juncture in its direct-to-consumer journey," Mark Shapiro, president and chief operating officer of TKO, said in a statement. "WWE Premium Live Events are renowned for exactly the type of rich storytelling, incredible feats of athleticism and can't-miss, cultural tentpole experiences that have become synonymous with ESPN. Through our UFC relationship, we have experienced firsthand how transformational an ESPN presence can be, and we know this will be an exceptional partnership at a time of great innovation for both companies."

The UFC's media rights evolution was equally dramatic. After years with ESPN, where the promotion had helped establish ESPN+ as a legitimate streaming platform, TKO orchestrated a stunning pivot. Paramount Skydance on Monday announced a seven-year media rights agreement with TKO Group under which Paramount+ will become the exclusive home of all UFC events in the U.S. — pulling the mixed martial arts events from ESPN.

The numbers were staggering: The seven-year term, which begins in 2026, has an average annual value of $1.1 billion, with an overall value of $7.7 billion. This represented more than double what ESPN had been paying, as UFC's broadcast rights deal with Disney's ESPN, which has been paying an average of around $500 million annually over five years, expires at the end of 2025.

But the real revolution was in distribution strategy. As part of the agreement, UFC and Paramount will move away from UFC's existing pay-per-view model — and instead, the events will be available at no additional cost to Paramount+'s U.S. subscribers. Dana White confirmed the historic nature of the change: "This historic deal with Paramount and CBS is incredible for UFC fans and our athletes. For the first time ever, fans in the US will have access to all UFC content without a pay-per-view model, making it more affordable and accessible to view the greatest fights on a massive platform."

The end of pay-per-view represented a fundamental shift in combat sports economics. For decades, the biggest fights had commanded premium prices—$79.99 for a UFC numbered event, sometimes more for boxing superfights. That model, which had generated billions in revenue over the years, was being abandoned for the certainty of guaranteed rights fees.

David Ellison, Paramount's new CEO following the Skydance merger, understood the stakes: "UFC is a unicorn asset that comes up about once a decade". He emphasized the strategic importance: "Paramount's advantage lies in the expansive reach of our linear and streaming platforms. Live sports continue to be a cornerstone of our broader strategy -- driving engagement, subscriber growth, and long-term loyalty, and the addition of UFC's year-round must-watch events to our platforms is a major win."

The international strategy was equally aggressive. While WWE had given Netflix global rights outside the U.S., UFC was taking a more fragmented approach. Paramount intends to explore UFC rights outside the U.S. as they become available in the future. This created opportunities for local partnerships and regional optimization.

The streaming wars had fundamentally changed the economics of combat sports. Traditional pay-per-view, which required fans to make individual purchase decisions for each event, was being replaced by subscription models that provided predictable revenue streams. UFC events are desirable for streamers because they take place year-round — keeping fans paying for monthly subscriptions with less incentive to cancel seasonally than with other sports. There are 43 live events annually, consisting of 350 hours of live programming.

The shift reflected broader changes in media consumption. Acquiring rights to "Raw" solidifies Netflix's push into live programming, with the streamer having just tested the waters with livestreaming of late. But with "Raw," Netflix will have a live program that runs weekly year-round. This wasn't just about individual events anymore—it was about creating sticky content that kept subscribers engaged month after month.

TKO's media rights portfolio post-2026 would be unprecedented: WWE Raw on Netflix globally, UFC on Paramount+ in the U.S., WWE Premium Live Events on ESPN, and various other arrangements internationally. The company had effectively spread its bets across every major streaming platform, ensuring that regardless of who won the streaming wars, TKO would emerge victorious.

The Netflix era represented more than just new distribution channels. It marked the moment when combat sports fully embraced their destiny as premium streaming content. "This deal is transformative," added Mark Shapiro, president and COO of WWE parent company TKO. "It marries the can't-miss WWE product with Netflix's extraordinary global reach and locks in significant and predictable economics for many years."

The implications were profound. No longer would success be measured solely by pay-per-view buys or television ratings. Now it was about subscriber acquisition, monthly active users, and reducing churn. The fighters and wrestlers who could move those metrics would become the new stars. The old model of sporadic superfights was giving way to consistent, year-round content production.

As 2025 progressed, the results spoke for themselves. TKO Group Holdings beat Wall Street expectations in its first quarter earnings report, with the WWE's new media rights deal with Netflix, strong live event performance at UFC and WWE, and significant growth in partnerships at both brands helping the company set itself up for what it hopes will be a strong 2025. The company reported revenues of $1.3 billion, with net income of $166 million and adjusted EBITDA of $417 million, all substantial improvements from a year ago. The company also raised its full year 2025 guidance to revenue of between $3.005 billion to $3.075 billion, from $2.930 billion to $3.000 billion.

The media rights revolution had delivered exactly what Emanuel and Shapiro had promised: predictable, growing revenue streams that transformed TKO from an event-driven business into a content platform. The Netflix era wasn't just about where people watched—it was about reimagining what combat sports could be in the streaming age.

VIII. Financial Performance & Market Position

The numbers tell a story of dominance. When TKO Group Holdings reported its 2024 results, the financial community took notice. The company had delivered on every promise made during the merger, exceeding guidance and demonstrating the power of its integrated model.

The company reported revenues of $2.804 billion for 2024 and a net income of $6.4 million. For the fourth quarter of 2024, TKO reports a revenue of $642.2 million and a net income of $47.5 million. WWE had a revenue of $1.398 billion in 2024 while UFC's revenue was $1.406 billion. Adjusted EBITDA increased 55%, or $442.1 million, to $1.251 billion, due to an increase of $518.1 million at WWE and an increase of $45.3 million at UFC, partially offset by an increase of $121.3 million in corporate expenses.

The balanced contribution from both divisions validated the merger thesis. UFC and WWE weren't just coexisting—they were thriving together, each pulling its weight while benefiting from shared infrastructure and expertise.

Looking at the longer trajectory, the transformation was even more impressive. In 2022, before the merger, the combined pro-forma revenue of UFC and WWE was $2.43 billion with net income of $351.8 million. By 2024, revenue had grown to $2.80 billion, representing 67% growth from 2023 alone. The acceleration was undeniable.

The growth drivers were multifaceted. Media rights, obviously, were exploding. The Netflix deal for Raw, the upcoming Paramount+ agreement for UFC, and ESPN's acquisition of WWE Premium Live Events represented billions in guaranteed revenue over the coming years. But it wasn't just about the big deals.

Sponsorship revenue was surging. UFC sponsorships grew 28% year-over-year, while WWE partnerships increased 20%. Brands that might have hesitated to associate with either property alone were eager to access TKO's combined reach. A single partnership could now include octagon branding, wrestling ring presence, and activation across hundreds of live events annually.

Live event performance exceeded all expectations. TKO hosted more than 500 events in 2024, with record-breaking gates becoming routine. UFC 300 generated the highest gate in MMA history. WrestleMania 40 set new merchandise records. Even smaller events were selling out arenas that had struggled to fill seats in previous years.

The merchandise evolution was particularly striking. WWE had always been a merchandising machine, but under TKO, UFC was learning those lessons rapidly. Fighter-specific merchandise lines, limited edition collectibles, and crossover products were driving per-fan spending to unprecedented levels.

Digital engagement metrics painted a picture of a young, engaged audience that advertisers coveted. Social media following across TKO properties exceeded 2 billion. YouTube views topped 50 billion annually. The company wasn't just producing events—it was creating content that lived forever online, generating revenue long after the live gate closed.

The debt structure remained manageable despite the aggressive expansion. TKO carried approximately $2.5 billion in debt, but with EBITDA exceeding $1.25 billion annually, the leverage ratio of 2x was conservative by entertainment industry standards. The company had ample flexibility for further acquisitions or capital returns to shareholders.

Capital allocation reflected confidence. TKO announced a $2 billion share buyback program, signaling management's belief that the stock remained undervalued despite strong performance. The company also instituted a modest dividend, appealing to income-focused investors who might not typically consider entertainment stocks.

The international opportunity remained largely untapped. While TKO generated approximately 30% of revenue outside the United States, comparable sports properties often exceeded 50% international mix. The upcoming international rights negotiations for both UFC and WWE represented billions in potential incremental revenue.

The comparison to traditional sports leagues was increasingly favorable. The NFL generated approximately $18 billion in annual revenue with 32 team owners to satisfy. TKO was approaching $3 billion with complete control over its talent and venues. The efficiency gap was closing rapidly.

Margin expansion told the operational excellence story. Through the elimination of duplicate functions, negotiating power with vendors, and technology investments, TKO had expanded EBITDA margins from the mid-30s to over 40%. Every dollar of revenue was generating more profit than ever before.

The talent cost structure remained TKO's secret weapon. Unlike major sports leagues with collective bargaining agreements guaranteeing players 48-50% of revenue, TKO's independent contractor model meant talent costs remained under 20% of revenue. This structural advantage seemed increasingly valuable as media rights exploded.

Analysts were taking notice. Wall Street consensus called for 12% annual revenue growth over the next three years, compared to 9.3% for the broader entertainment industry. Some bulls argued the estimates were too conservative, given the locked-in media rights increases and untapped sponsorship potential.

The recurring revenue transformation was perhaps most important for valuation. In 2019, before the WWE's Fox deal and UFC's ESPN agreement, both companies were heavily dependent on volatile pay-per-view revenue. By 2024, over 80% of revenue was contractually guaranteed through multi-year agreements. The business model had shifted from entertainment company to media property.

Competitive positioning seemed unassailable. In MMA, Bellator had been absorbed, PFL remained subscale, and ONE Championship was regional. In professional wrestling, AEW had plateaued after initial growth, Impact was irrelevant, and international promotions remained local. TKO didn't just lead its categories—it essentially owned them.

The platform economics were compelling. The cost to produce an incremental UFC or WWE event was relatively fixed, but the revenue opportunity—through gates, sponsorships, and media rights—scaled dramatically. Every new event added was increasingly profitable.

Technology investments were paying dividends. TKO's proprietary data platform tracked every fan interaction, from ticket purchases to merchandise to streaming behavior. This first-party data was becoming invaluable for sponsors and media partners seeking to understand the combat sports audience.

The demographic profile remained advertiser-friendly despite the violent content. UFC skewed heavily male 18-34, the most coveted and hardest-to-reach demographic in media. WWE's broader family appeal meant women and children balanced the overall TKO audience. Few properties could claim such demographic diversity.

Looking forward, the financial trajectory seemed clear. With media rights locked in through the end of the decade, sponsorship growth accelerating, and international expansion just beginning, TKO was positioned to reach $5 billion in revenue by 2030. For a company that didn't exist before 2023, it was a remarkable growth story.

But the financials only told part of the story. The real achievement was strategic: TKO had transformed two businesses that were once considered niche into mainstream entertainment properties worth more than most traditional sports franchises. The financial performance validated the vision, but the market position—essentially monopolistic control over how the world watches combat sports—was priceless.

IX. Power, Politics & Controversy

The boardroom at TKO headquarters fell silent on January 26, 2024. Ari Emanuel had just received word that Vince McMahon, executive chairman of the company formed just four months earlier, was resigning effective immediately. The scandal that had been brewing finally exploded. A former WWE employee, Janel Grant, had filed a federal lawsuit against McMahon, WWE, and former executive John Laurinaitis, alleging sex trafficking, sexual assault, and physical abuse.

The lawsuit was devastating in its details. Grant alleged McMahon had used his position to coerce her into a sexual relationship, shared explicit materials with other WWE employees, and promised career advancement in exchange for sexual favors. Coming just months after McMahon had forced his way back into WWE specifically to orchestrate the TKO merger, the timing couldn't have been worse.

McMahon's resignation statement was terse: "I stand by my prior statement that Ms. Grant's lawsuit is replete with lies, obscene made-up instances that never occurred, and is a vindictive distortion of the truth. However, out of respect for the WWE Universe, the extraordinary TKO business and its board members and shareholders, I have decided to resign from my executive chairmanship and the TKO board of directors, effective immediately."

The end of the McMahon era was stunning in its swiftness. For over 70 years, a McMahon had controlled professional wrestling's dominant company. Three generations of family leadership, from Jess to Vincent Sr. to Vince Jr., disappeared in a single press release. The man who had built WWE into a global empire, who had survived federal prosecution and countless controversies, was gone.

But TKO barely missed a beat. The stock dipped briefly, then recovered. The business structure Emanuel and Shapiro had built didn't depend on McMahon's presence. If anything, his departure removed a potential liability. Corporate sponsors who might have been uncomfortable with McMahon's presence could now engage without reservation.

The contrast with another board addition was stark. The same day WWE and Netflix announced their deal in January 2024, another bombshell dropped: Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson was joining TKO's board of directors. Johnson also secured full ownership of "The Rock" trademark, which WWE had held for decades. The symbolism was powerful—out with the controversial old guard, in with one of Hollywood's most bankable and beloved stars.

"Being on the TKO Board of Directors, and taking full ownership of my name, 'The Rock,' is not only unprecedented, but incredibly inspiring as my crazy life is coming full circle," Johnson said in a statement (via ESPN). "At my core, I'm a builder who builds for and serves the people, and [TKO CEO] Ari [Emanuel] is building something truly game-changing. I'm very motivated to help continue to globally expand our TKO, WWE, and UFC businesses as the worldwide leaders in sports and entertainment."

The Rock's addition wasn't just ceremonial. His social media reach exceeded 400 million followers. His Hollywood connections were unmatched. His ability to bridge wrestling's past with TKO's future was invaluable. When he appeared at WWE events, ratings spiked. When he promoted UFC fights, mainstream media paid attention.

But controversy wasn't limited to WWE's executive suite. The Saudi Arabia relationship remained contentious. WWE's multi-year agreement to produce premium events in the Kingdom, reportedly worth over $50 million per event, drew consistent criticism from human rights organizations. The murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Saudi Arabia's human rights record, and the concept of "sportswashing" haunted every WWE event in Riyadh.

TKO's response was purely pragmatic. The Saudi events were among the most lucrative on the calendar. The Kingdom was investing heavily in sports—from golf to soccer to boxing—and TKO wanted its share. When critics complained, executives pointed to WWE's global reach and argued they were bringing entertainment to fans worldwide.

Labor issues simmered constantly. The independent contractor classification that gave TKO such financial flexibility also drew regular scrutiny. Fighters and wrestlers had no union, no collective bargaining rights, no guaranteed healthcare or retirement benefits. Several lawsuits challenging the classification worked through the courts, though none had succeeded in forcing change.

Former UFC fighter Leslie Smith's attempt to organize fighters had failed. WWE wrestlers who spoke publicly about forming a union found their pushes mysteriously stalled. The message was clear: TKO's business model depended on maintaining the status quo, and the company would fight aggressively to preserve it.

The antitrust question loomed larger as TKO's dominance grew. The company controlled an estimated 90% of the professional wrestling market and 85% of MMA. Every acquisition—from the IMG assets to the planned boxing ventures—raised questions about monopolistic practices. So far, regulators had shown little interest, but that could change with a different administration or a particularly aggressive state attorney general.

Cultural controversies were constant. UFC's Dana White was filmed slapping his wife at a New Year's Eve party in 2023, yet faced no professional consequences. Fighters regularly made inflammatory statements on social media. Wrestlers were caught in scandals ranging from drug abuse to domestic violence. The violent nature of the content attracted a certain type of performer, and managing their behavior was an ongoing challenge.

The CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) issue haunted both divisions. While UFC fighters absorbed real brain trauma, WWE wrestlers suffered countless concussions from "worked" moves gone wrong. The NFL's multi-billion dollar settlement over brain injuries served as a warning. TKO maintained that participants knew the risks, but lawsuits from former fighters and wrestlers alleging long-term brain damage were inevitable.

Political dynamics added complexity. UFC had become increasingly associated with conservative politics. Dana White spoke at Donald Trump rallies. Fighters regularly expressed right-wing views. Meanwhile, WWE tried to maintain its family-friendly, apolitical stance, though the McMahon family's close ties to Trump complicated that narrative.

The streaming platforms brought their own political pressures. Netflix faced criticism for platforming WWE content that some considered misogynistic or violent. ESPN dealt with staff complaints about promoting UFC events where fighters had made controversial statements. The corporate partners wanted the content but not the controversy.

Regulatory challenges varied by market. Some countries restricted combat sports broadcasting. Others required local partners or content modifications. WWE had to edit its content for certain Middle Eastern markets. UFC events were banned entirely in some jurisdictions. The patchwork of global regulations complicated TKO's international expansion.

The performance-enhancing drug issue never fully disappeared. Both UFC and WWE had drug testing programs, but skeptics questioned their rigor. When fighters or wrestlers showed dramatic physical transformations, steroid speculation was immediate. The balance between allowing performers to look superhuman while maintaining credibility about drug testing was delicate.

The blurring lines between real and scripted created unique controversies. When Conor McGregor threw a dolly at a bus full of UFC fighters, was it a real incident or promotion for his upcoming fight? When WWE wrestlers broke character on social media, was it genuine emotion or sophisticated storytelling? The ambiguity that made the content compelling also made accountability difficult.

Despite all these challenges, TKO's position seemed unshakeable. The controversies that might sink other companies barely dented TKO's business. Fans seemed to separate their love of the content from their feelings about the executives. Sponsors valued the reach more than they feared the headlines. Media partners needed the ratings and subscribers.

In many ways, TKO had become too big to fail. The ecosystem—from vendors to venues to media partners—depended on TKO's success. Thousands of jobs, billions in economic impact, and entire television schedules relied on UFC and WWE content. The controversies were the price of doing business at this scale.

Emanuel's approach to controversy was distinctly Hollywood: all publicity is good publicity. As long as the events sold out, the content delivered ratings, and the stock price climbed, the controversies were manageable distractions. In an attention economy, being talked about—even negatively—was better than being ignored.