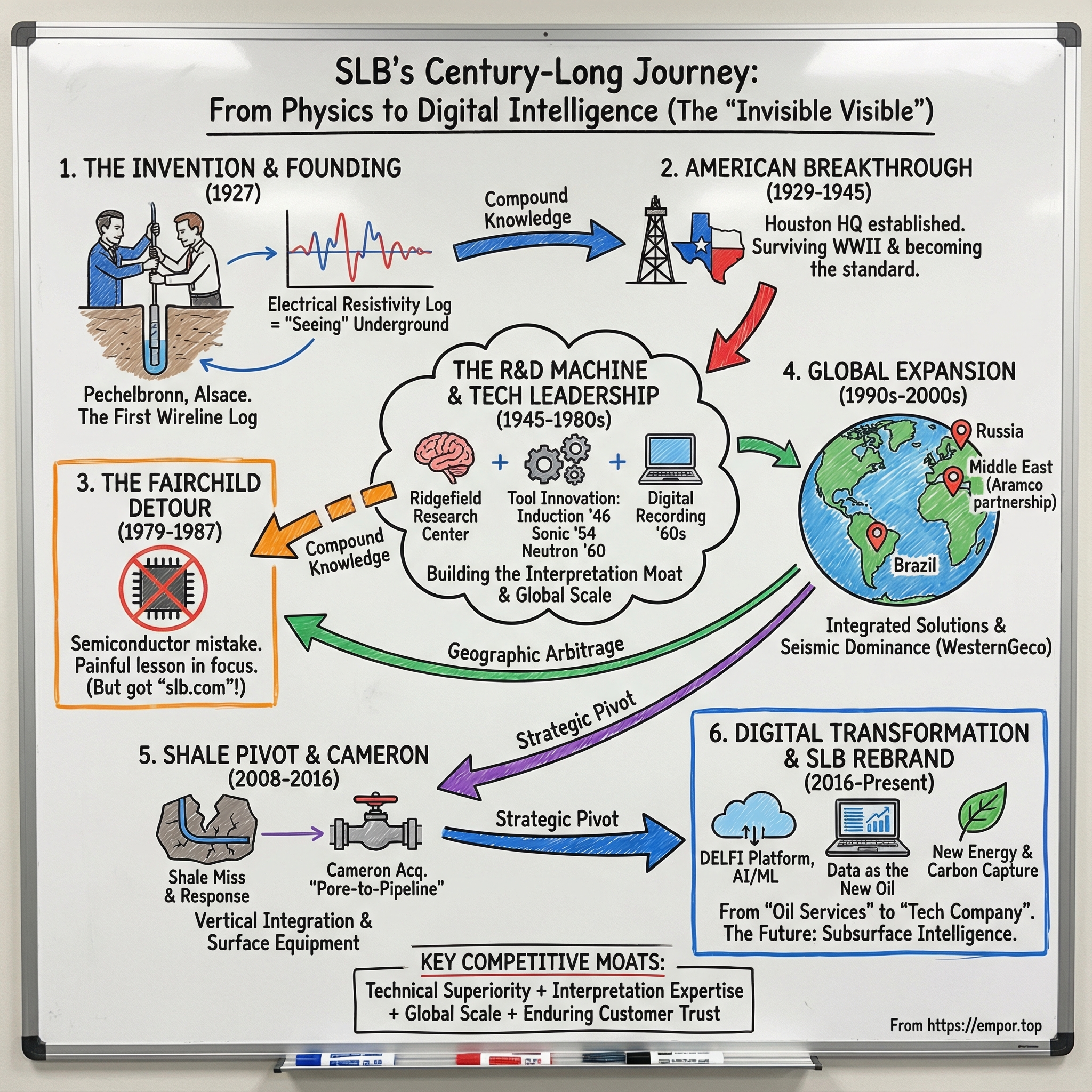

SLB: The Physics of Oil - How Two Brothers Built the World's Largest Oilfield Services Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 1927 in the small oil field of Merkwiller-Pechelbronn in Alsace, France. Two brothers—one a physicist, the other an engineer—lower an electrical sonde down a wellbore. They send a current into the rock and listen for the response. What comes back isn’t just a squiggle on paper. It’s the first time anyone can “see” underground without digging.

The oil industry will never be the same.

Fast-forward to today. SLB sits at roughly a $51 billion market cap and generates more than $36 billion in annual revenue, making it the world’s largest oilfield services company. But the story of how two French brothers from Alsace built that empire isn’t really a story about oil. It’s a story about making the invisible visible—about turning physics into an unfair advantage, and then scaling that advantage across the entire planet.

The Schlumberger brothers didn’t strike oil. They did something more valuable: they built the technology that tells you where oil is before you drill. In a business where a single dry hole can cost a fortune, that difference is everything. Their breakthrough wasn’t merely early—it was so much better that, nearly a century later, the same underlying principle still sits beneath modern oil discovery.

This is a story of technical brilliance meeting perfect timing. Of a European scientific mindset landing in the rough-and-ready world of Texas wildcatters. Of surviving two world wars, repeated boom-bust cycles, and even a spectacularly misguided semiconductor detour. And it’s also a story about reinvention: how a company that began with electrical resistivity measurements evolved into a digital powerhouse running AI models on vast libraries of subsurface data. In 2024, SLB generated $3.99 billion in free cash flow. As of August 2025, its market cap was about $50.07 billion. The numbers move—but the core idea hasn’t: the same physics the brothers proved in the 1920s is still what SLB sells.

Along the way, we’re going to keep coming back to a few big questions. How do you build a technical moat so deep competitors are still struggling to cross it a hundred years later? How do you turn a scientific insight into operational excellence at global scale? And what does it look like to be indispensable to an industry the world says it wants to leave behind?

This is the story of SLB—a company that turned uncertainty into data, and data into power. Because in the oil business, knowing where to drill can be worth more than the oil itself.

II. The Schlumberger Brothers & The Invention

In 1912, Conrad Schlumberger was out in the French countryside running an experiment that, on paper, looked almost trivial: push a current into the ground, measure what comes back, repeat. It had been wet, messy work—wires, electrodes, and instruments fighting mud and weather. But that day the readings did something they weren’t supposed to do. The needle didn’t wander randomly. The field organized itself into patterns: equipotential curves that hinted at shape and structure below the surface.

Conrad realized he wasn’t just measuring electricity. He was measuring geology.

That “aha” wasn’t luck so much as the natural outcome of who he was. Conrad, born in 1878 in Guebwiller in Alsace, came from a family of textile industrialists—people who understood industry, scale, and the value of doing things systematically. But Conrad went the other direction: to physics at the École Polytechnique in Paris, and then into the early world of geophysics. At a time when others were probing the earth with seismic waves and gravity surveys, Conrad became convinced electricity could do something those tools couldn’t: reveal the subsurface in a direct, measurable way.

And then there was Marcel.

Marcel Schlumberger, six years younger, was the builder. Born in 1884 and trained at École Centrale Paris, he was the engineer who could take Conrad’s elegant idea and turn it into something that worked in the field—something you could pack into crates, haul across borders, and operate on a drilling site without it falling apart. Conrad could see the theory. Marcel could ship it, fix it, and sell it.

The breakthrough itself was almost annoyingly simple. Different rocks conduct electricity differently. Water-filled formations tend to conduct well; oil-bearing formations resist. If you could send current into the earth and measure resistivity, you could start distinguishing what was down there. Not with guesses. With data.

Between 1912 and 1926, the brothers turned that concept into a craft, refining it through a string of international trials. They worked Romania’s Ploiești oil fields, chasing the structures that trapped petroleum. They tested in Canada, then Serbia, then farther afield still—each project adding to a growing body of hard-won, practical knowledge about what electrical signals meant in real geology. That experience didn’t just improve their tools. It taught them how to interpret the results, and interpretation was the real product.

Because the industry they were trying to sell to was deeply skeptical. In the 1920s, oil exploration still leaned heavily on surface geology, hunches, and luck. The notion that you could “see” underground with wires and a battery sounded like a parlor trick. When the Schlumbergers showed their apparatus to oilmen, the reaction was often some version of: Interesting… but no.

So in 1926, they did what serious inventors eventually have to do: they made it a company. In Paris, they founded Société de Prospection Électrique, backing their work with 500,000 francs of capital. The timing mattered. The world was putting cars on roads at a stunning pace, and oil demand was surging. But the industry’s ability to find new reserves was still, in many ways, medieval. There was an opening for something scientific and repeatable.

Their proof arrived in Alsace, right where the story began. On September 5, 1927, Henri George Doll and a small team ran the first wireline electric log at the Diefenbach #2905 well—Rig 7 of the Pechelbronn Oil Company—at Merkwiller-Pechelbronn in Bas-Rhin. By modern standards it was painfully slow. The well was about 500 meters deep, but they logged only part of it, from roughly 130 to 270 meters, taking readings every meter at a pace of about 50 meters an hour.

Then they plotted the results.

And suddenly the subsurface wasn’t a mystery. The log separated layers. It showed boundaries. It pointed to the zones that mattered—including the oil-bearing formations. What had been invisible became legible.

That one run turned a science experiment into a service business. Less than a year later, on July 28, 1928, the oil field owners signed a contract with Schlumberger for 12,000 francs a month—about $2,600 at the time—creating the first sustained well-logging program. The value proposition was immediate and concrete: identify productive intervals, correlate formations between wells, and reduce the chance of drilling right past the pay zone.

And here’s the key: the defensibility wasn’t the sonde. It was the meaning.

In theory, others could copy the idea of lowering electrodes into a well. But turning those squiggles into decisions required deep physics, geology, and—most importantly—experience. The Schlumbergers had spent years building a mental library of resistivity “signatures” across rock types and fluid conditions. That proprietary understanding became their moat, more powerful than any single patent.

By 1928, word of Pechelbronn had started moving through the small, talkative world of petroleum geology. Companies from far beyond France wanted to know about the strange new method that could read rock from inside a well. The brothers knew they had something special. They also knew the oil business rewarded one thing above all: going where the action was.

And in 1929, the center of gravity wasn’t in Europe.

It was America.

III. Breaking Into America & Early Growth (1929–1945)

The message landed in the Paris office on a cold February morning in 1929. Union Oil Company wanted electrical logging—and they wanted it now. Marcel read the telegram, looked up at Conrad, and didn’t need to say much. America was the biggest oil market in the world, and it was obsessed with one thing: certainty. If Schlumberger could deliver that in California and Texas, they wouldn’t just have a few contracts. They’d have the industry.

That fall, in September 1929, a Schlumberger crew ran its first commercial well log in the United States, in Kern County, California. Kern wasn’t just any oil region. It was the beating heart of California’s boom. This was the kind of place where reputations were made fast—and ruined faster. The crew, led by engineer Roger Arps, worked through the night to get the log done, with the sense that they weren’t just logging a well. They were auditioning for the entire American oil patch.

The early days were part breakthrough, part culture shock. Schlumberger’s engineers arrived with Paris training and a belief that if you measured the world carefully enough, it would explain itself. The American wildcatters they met didn’t particularly care about explanations. They cared about whether the bit hit pay.

In one oft-repeated moment, a Schlumberger engineer tried to walk a skeptical group of drillers through electrical resistivity. The foreman cut him off: so this wire can tell me where oil is better than my nose? The punchline wasn’t the banter. It was what happened next. The log correctly warned them off a dry hole that would have been expensive, and the foreman—suddenly very interested in graphs—became one of Schlumberger’s loudest advocates.

The real inflection point came in 1932. Shell Oil, impressed by Schlumberger’s work in Venezuela, invited the company to log wells across California and the Texas Gulf Coast. That mattered because Shell wasn’t buying a clever experiment. Shell was buying a method. In oil, that kind of endorsement doesn’t just create revenue—it creates legitimacy. Doors opened. Phone calls got returned. Schlumberger stopped being “those French guys with the wire” and started being the people you called when you wanted to know the truth about your well.

Credibility still had to be earned one job at a time, in conditions that were punishing even by oilfield standards. Crews worked through East Texas heat with mosquitoes so thick they wore nets while taking measurements. In winter, ice storms turned rigs into skating rinks. But the routine never changed: show up, run the tool, deliver the log. Over and over again, they proved the same point—this wasn’t theory. It was a competitive advantage you could hold in your hand.

That advantage was simple to describe and hard to match. While others leaned on surface geology and luck, Schlumberger’s logs could tell operators where they were about to hit oil, water, or nothing at all. In 1933, the company’s data identified a productive zone that conventional analysis had missed in a well that was about to be written off. The well didn’t just recover—it became a serious producer, and stories like that traveled faster than any sales pitch.

By September 15, 1934, the American business had enough momentum to formalize. Schlumberger created Schlumberger Well Surveying Corporation, based in Houston. The city choice was obvious: Houston was becoming the nerve center of the industry. Conrad served as chairman and Marcel as president, keeping family control while planting their flag right where the deals, the talent, and the rigs were.

Then history intervened.

World War II should have broken the company. It was French. Its people were scattered. Its work, on paper, could be deemed non-essential. And the family itself was hit hard. Conrad had died of a heart attack in 1936 while returning from a business trip to the Soviet Union. During the German occupation, the company’s center of gravity shifted away from Paris—and, effectively, toward Houston.

Henri George Doll, Conrad’s son-in-law and one of the company’s key technical minds, fled to Connecticut and carried the research effort with him. Marcel’s son Pierre took charge of the American operation, keeping it running while Marcel remained in France. René Seydoux, another family member, was imprisoned by the Germans. Schlumberger wasn’t just managing a wartime economy. It was trying to stay whole while being pulled apart.

And yet, in a way only war can engineer, the disruption strengthened Schlumberger’s position in the United States. With European operations suspended and Paris cut off, Houston became the company’s operational anchor by necessity. American engineers—who had once viewed Schlumberger as an outsider—stepped into greater responsibility. The technology itself proved valuable to the broader wartime need for oil, helping locate reserves that fueled military operations.

The forced Americanization solved a problem Schlumberger hadn’t fully been able to solve in peacetime: identity. Before the war, the company could feel like a foreign interloper on Texas soil. After the war, with real authority in Houston and American leadership in the field, Schlumberger wasn’t just tolerated. It belonged. It kept its French scientific edge, but it earned American operational credibility.

When the war ended, Pierre Schlumberger took over the American company with a clear-eyed view of what came next. The future wasn’t France. It was every major oil basin on earth. And the moat couldn’t be just a tool lowered into a well. It had to be the engine behind that tool: research, interpretation, and relentless technical progress.

By 1945, Schlumberger had logged more than 10,000 wells in America alone, and its share of electrical logging had climbed past 70%. It was dominance—but Pierre understood how fragile dominance can be if it rests on a single trick. The post-war industry would demand more than measurement. It would demand answers.

So the company prepared to become something bigger: not just a service provider, but a technology institution. And that next chapter would begin far from any oil field, on a quiet estate in Connecticut that would turn into the most important oil research facility that never drilled a single well.

IV. The R&D Machine & Technology Leadership (1945–1980s)

The property in Ridgefield, Connecticut had once belonged to a railroad baron. Rolling hills, big stone buildings, and the kind of quiet you can hear. It didn’t look like the birthplace of oilfield technology. But when Henri George Doll walked the grounds in 1947, he saw exactly what Schlumberger needed next: a place far from prying eyes, close enough to the Northeast’s universities to recruit talent, and large enough to build a permanent research engine. By 1948, the Schlumberger-Doll Research Center was up and running—and it quickly became the closest thing the oil industry ever had to its own Los Alamos.

Doll wasn’t interested in polishing the existing toolkit. He wanted to expand the very definition of what could be measured in a well. One early obsession captured that mindset: nuclear magnetic resonance logging—the idea that magnetic fields could help identify fluids inside the pore space of rock. Plenty of scientists said it couldn’t be done under the heat, pressure, vibration, and electrical noise of a borehole. Doll’s response was essentially: great, let’s hire the people who say it’s impossible and make them prove themselves wrong.

The culture that formed at Ridgefield was unusual even by the standards of postwar American R&D. PhD physicists and field engineers worked side by side. A morning could be spent on theory; the afternoon on how drilling mud behaves in the real world. Lab coats and coveralls in the same hallway. The unifying principle wasn’t background or pedigree—it was the expectation that you could connect deep science to something that would survive an oilfield beating. Years later, one researcher summed up Doll’s style: he’d walk in, glance at your work, say “Interesting, but why didn’t you consider…,” and then sketch a better approach than you’d spent weeks imagining.

All of that required money, and it required patience. Schlumberger had already laid the corporate groundwork in 1956 by creating Schlumberger Limited as a holding company—structure for global growth, and a cleaner way to keep research central while operations expanded. Then came the big moment: on February 2, 1962, Schlumberger Limited listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Going public changed the scale of what they could fund. It also introduced a new antagonist: quarterly pressure.

Pierre Schlumberger’s answer was to set a rule that protected the heart of the company: R&D would not fall below 3% of revenue, regardless of market conditions. When downturns hit and others cut research to protect margins, Schlumberger kept spending. Sometimes more than competitors thought was rational. Pierre believed the opposite: in a cyclical industry, your advantage is built when everyone else is forced to pause.

And the output of that machine came fast. The induction log, introduced in 1946, could measure resistivity without direct electrical contact—critical once oil-based muds became common. The Laterolog followed in 1949, delivering focused resistivity measurements that could pick out thin productive zones that older tools smeared into the background.

Then the portfolio started to stack, one capability on top of another. The Sonic log arrived in 1954, using sound to infer porosity and rock strength. The Formation Density Log came in 1959, using gamma ray scattering to estimate bulk density. The Neutron Log followed in 1960, detecting hydrogen and helping indicate hydrocarbons. The point wasn’t any single tool. It was what happened when you combined them: a well went from being a dark hole in the ground to a set of measurable properties you could interpret, compare, and act on. By the mid-1960s, a Schlumberger logging run could tell you more about a formation than surface work could ever reliably infer.

In 1960, Schlumberger took a step that widened the business from “tell you what’s there” to “help you change what happens next.” Dowell Schlumberger—half owned by Schlumberger and half by Dow Chemical—brought pumping services into the fold: acidizing, fracturing, cementing. With Schlumberger’s diagnostics and Dowell’s ability to intervene, they could increasingly do both: identify problems and fix them.

By 1970, Schlumberger’s wireline position had become almost absurd: more than 70% global market share in electrical logging. It wasn’t magic, and it wasn’t just first-mover advantage. It was three moats reinforcing each other.

First: the tools. Schlumberger equipment was more accurate, more reliable, and consistently a generation ahead. Competitors like Halliburton and Dresser Industries could introduce alternatives, but Schlumberger had already moved on.

Second: the interpretation. A log wasn’t the product—the meaning of the log was. Schlumberger employed an army of analysts, built charts and methods that became industry standards, and effectively taught customers how to think in the company’s language. Oil companies weren’t just buying measurements; they were buying Schlumberger’s ability to turn signals into decisions.

Third: global scale. By 1975, Schlumberger operated in more than 100 countries. A field lesson in Nigeria could influence a workflow in the North Sea. A tool designed for Venezuela could be adapted for Canada. Knowledge traveled through the organization, and the more wells they touched, the smarter they became. Regional competitors couldn’t replicate that compounding feedback loop.

That same system pulled in talent. Graduates from places like MIT and Stanford often chose Schlumberger over the majors because the cutting-edge work was happening inside the service company, not just the operators. Training was a core competency, too. The internal program known as “Schlumberger School” rotated engineers through the field and through research, keeping practical pain points flowing back to the labs—and new ideas flowing back to the rigs.

One story captures the tone. In 1968, a young engineer named Andrew Gould—who would later become CEO—presented a new logging tool prototype to a review committee. A senior engineer looked it over and said, essentially: good. Now make it work in extreme heat, extreme pressure, and assume the customer will drop it off the platform at least once. That blend of elegant physics and practical brutality was the Schlumberger signature.

Then computing arrived, and it changed everything. The 1970s were the decade logging moved from analog squiggles to digital data, and Schlumberger had been preparing for years. They started experimenting with digital recording in 1962. In 1969, they introduced the Cyber Service Unit, the first computerized logging unit, able to process data at the wellsite and deliver interpretation in real time. While competitors were still shipping paper charts back to town, Schlumberger was running algorithms at the rig.

By 1980, the research operation had grown to more than 2,000 scientists and engineers across multiple centers. The patent portfolio passed 3,000 active patents. Annual R&D spending was nearing $200 million—more than many competitors brought in, period. Schlumberger had become the technology backbone of oil.

And that’s when Pierre Schlumberger looked at the broader technology landscape and saw what he believed was the next platform shift—one that would either transform the company, or nearly break it: semiconductors.

V. The Fairchild Semiconductor Detour (1979–1987)

“Gentlemen, the future of oilfield services is silicon.” In 1979, Schlumberger CEO Michel Vaillaud stood in front of the board and made the case for what would become the most controversial move in the company’s history. Every logging tool, every downhole sensor, every piece of equipment they shipped into the field was getting more computerized by the year. Schlumberger could keep buying chips like everyone else—or it could own the source.

His proposal: buy Fairchild Semiconductor.

Fairchild wasn’t just another chipmaker. It was the chipmaker—the company that helped invent Silicon Valley. Founded in 1957 by the “Traitorous Eight” who walked out of Shockley Semiconductor, Fairchild had produced the first commercial integrated circuit. Its alumni went on to build Intel, AMD, and National Semiconductor. By 1979, Fairchild was struggling. But the technology base, the engineering pedigree, and the aura were still there.

Schlumberger paid $425 million—its biggest acquisition ever at the time. The strategic logic sounded clean: tools were becoming computers; computers needed chips; oilfield tools needed chips that could survive brutal environments; therefore, owning semiconductor capability could become the next moat. On paper, it looked like Schlumberger was simply extending its R&D machine into the next platform shift.

In reality, it was the start of a slow-motion wreck.

The culture clash hit immediately. Schlumberger was built around field reliability: gear that could be dropped, soaked, shaken, and still deliver data. Fairchild lived in the world of clean rooms, microscopic tolerances, and manufacturing yields. One visiting Schlumberger executive reportedly looked around Fairchild’s San Jose facility and asked, “Why do you need such a clean room? Our tools work covered in drilling mud.” It wasn’t just a joke—it was a preview of how far apart these two worlds were.

Then came the management churn. Over five years, Schlumberger cycled through three Fairchild CEOs, each with a different idea of what the company should be: double down on memory chips, pivot to microprocessors, become a contract manufacturer for others. Meanwhile, Japanese semiconductor firms were taking share with better quality and lower prices. And Fairchild’s own boom-and-bust cycle made oil’s volatility look almost calm. Schlumberger had built its empire on compounding knowledge in one domain. In semiconductors, the ground shifted under your feet every product cycle.

And yet—even inside a disaster—there were strange, durable sparks.

Fairchild’s work on smart cards, originally aimed at things like telephone cards, later proved useful in secure data handling and transmission. Its early work with charge-coupled devices fed into downhole imaging concepts—ways to visually inspect conditions inside a well. And perhaps the most unintentionally prophetic move of all: Schlumberger became an early commercial user of ARPAnet, the precursor to the internet, and in 1987 registered slb.com astonishingly early in the .com era. On May 20, 1987, Schlumberger Limited registered slb.com, making it the 75th .com domain ever issued. While much of the industry still leaned on telex, Schlumberger engineers were already moving information as data packets.

None of that changed the financial reality. The bleeding was relentless. From 1979 to 1987, Fairchild piled up losses exceeding $1 billion. The semiconductor unit consumed cash and, worse, management attention—while contributing nothing to Schlumberger’s core oilfield mission. In oil terms, it was a dry hole that kept demanding more capital.

In 1987, newly installed CEO D. Euan Baird finally pulled the plug. Schlumberger wrote down much of Fairchild’s value and sold the remainder to National Semiconductor, taking a reported loss of $220 million on the sale. In total, the Fairchild episode cost Schlumberger roughly $1.5 billion—one of the largest corporate write-offs of its era.

The lesson wasn’t subtle. First: being great at one kind of high technology doesn’t mean you can win in another. Oilfield services and semiconductors both required brilliant engineers, but the markets, timelines, and competitive dynamics couldn’t have been more different. Second: diversification without adjacency destroys value. Schlumberger’s edge came from deep expertise, not from collecting impressive-sounding businesses.

Most importantly, the detour forced Schlumberger to answer a question it hadn’t needed to ask when it was winning so decisively: what business are we really in?

The answer wasn’t “chips.” It wasn’t even “technology,” broadly defined. Schlumberger was in the business of understanding what’s happening underground—turning reservoirs into information, and information into decisions. Everything else had to serve that mission, or it was a distraction.

Ironically, some of Fairchild’s byproducts did come back around decades later—just not as the grand strategic platform Vaillaud imagined. Smart card work informed security ideas. Semiconductor experience fed into rugged sensing. And slb.com became a small but telling symbol of something Schlumberger would eventually become: a company that treated information as seriously as it treated physics.

The bigger shift was organizational. After Fairchild, Schlumberger didn’t stop investing in R&D—it doubled down. From 1987 into the early 1990s, R&D spending ran 37% higher than before Baird took over. But now it came with a sharper mandate: oilfield problems only. No more glamorous detours.

What emerged on the other side, heading into 1988, was a leaner, more disciplined Schlumberger—still ambitious, still research-driven, but newly aware that technical excellence only matters when it’s pointed at the right target. And with that focus restored, the company turned to the next frontier that did fit its strengths: taking its playbook global, and expanding aggressively into the international markets where the future of oil was moving.

VI. Geographic Expansion & The International Playbook (1990s–2000s)

In January 1991, the call came in the middle of the night, Moscow time: the Soviet Union was breaking apart. If Schlumberger wanted to work in Siberia, they needed to move—fast. Within two days, a team was on a plane to Tyumen, the administrative hub of Russia’s oil country. Schlumberger became one of the first Western oilfield services companies on the ground in the former Soviet Union, kicking off an international expansion that would reshape both the company and the industry around it.

The push overseas wasn’t a sudden whim. It was a contrarian bet about where the next decades of oil would come from. While much of the industry stayed fixated on mature American fields, Schlumberger’s leadership saw the center of gravity moving outward—to deep water, deserts, and permafrost. The next giant barrels weren’t going to be easy barrels, and that mattered. In places where geology was brutal and infrastructure was thin, technical advantage could outrun local incumbency.

Schlumberger had always been international in footprint. What changed in the 1990s was the intent. This was no longer “we can work anywhere.” It became “we are going to be essential everywhere that matters.” Their playbook hardened into something repeatable: enter early—often during uncertainty, when competitors hesitated—win a flagship project, then turn that credibility into a long-term operating position, especially with national oil companies.

Russia was the purest version of the strategy. In 1991, the oil system the Soviets built was wobbling. Equipment was dated, production was sliding, and the rules of business were blurry at best. The risks were real: unclear laws, currency controls, and the ever-present fear that a deal could be rewritten by politics. Most Western companies waited for stability. Schlumberger walked into the turbulence.

They understood something subtle about frontier markets: technical competence becomes political capital. When Schlumberger’s horizontal drilling technology helped Lukoil lift production by 40% in a mature Siberian field, they didn’t just win a contract. They won trust. Soon, Russian oil executives were pushing for Schlumberger technology to be included in projects with Western majors—because using Schlumberger reduced the chance of failure, and failure in a fragile system had consequences far beyond a quarterly result.

At the same time, Schlumberger was building something else: a seismic empire. In 1986, Schlumberger bought 50% of GECO, the Geophysical Company of Norway, and by 1988 they owned it outright. That set up a merger with Merlin Geophysical (Seismic Profilers), which Schlumberger had acquired the year before. Then in 1991, they acquired PRAKLA-SEISMOS. Around this period, Schlumberger also pioneered the use of geosteering to plan the drill path in horizontal wells.

These weren’t random bolt-ons. Seismic is where exploration starts—the best way to reduce uncertainty before you ever drill. By owning seismic acquisition and processing, and combining it with their core strength in well logging and interpretation, Schlumberger could sell something bigger than a service line. They could sell an integrated picture of the subsurface, from first survey to drilled well. In 2000, that strategy culminated in WesternGeco, created by merging the Geco-Prakla division with Western Geophysical. Schlumberger held a 70% stake in what became the world’s largest seismic contractor.

In the Middle East, the challenge looked different. Here, the resource base and the capital were never the limiting factors. Relationships were. National oil companies like Saudi Aramco and ADNOC could buy technology from anyone. What they wanted—what they carefully screened for—were partners who understood that in the Gulf, trust is an asset you build slowly, in person, over years.

So Schlumberger invested in people as aggressively as it invested in tools. They built training centers in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, teaching local engineers how to run equipment and, just as importantly, how to interpret what the measurements meant. They hired locally at scale—by 2000, more than 80% of Schlumberger’s Middle East workforce was regional. And in 1998, when a Saudi engineer became the first Arab to run Schlumberger’s Middle East operations, it wasn’t just a staffing decision. It was a signal: Schlumberger wanted to be seen less as a contractor and more as a long-term institution in the region.

That relationship-first approach paid off when Saudi Aramco moved to develop the Shaybah field in the Empty Quarter—one of the most challenging oil projects ever attempted. Drilling there meant punishing heat and unstable formations that could collapse without warning. Aramco chose Schlumberger as its primary service provider. Schlumberger delivered, and Shaybah became a cornerstone reference point: proof that Schlumberger could execute at the edge of what oilfield engineering would tolerate.

Not every move landed cleanly. In 1999, Schlumberger and Smith International formed a joint venture, M-I L.L.C., to create the world’s largest drilling fluids company, with Smith owning 60% and Schlumberger 40%. But the structure ran straight into a legal tripwire: a 1994 antitrust consent decree barred Smith from selling or combining its fluids business with certain other companies, including Schlumberger. The U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., found both Smith International Inc. and Schlumberger Ltd. guilty of criminal contempt, fined each company $750,000, and placed each on five years’ probation. They also agreed to pay a total of $13.1 million, representing full disgorgement of the joint venture’s profits during the period of contempt.

For Schlumberger, it was a rare public black eye—and an important reminder that sophistication in the field doesn’t protect you in a courtroom. The episode forced a more cautious approach to deal structure and antitrust risk in the years that followed.

Meanwhile, the expansion kept widening—not just geographically, but in capability. WesternGeco, with Schlumberger’s 70% stake, gave the company seismic reach from the Arctic to deep water. In Latin America, Brazil became a proving ground for extreme engineering. Pre-salt discoveries in the Santos Basin required drilling through massive salt layers, a challenge that demanded both specialized tools and relentless iteration. Schlumberger established a research center in Rio de Janeiro, hired Brazilian engineers, and developed salt-focused drilling technologies. By 2005, they were involved in virtually every major pre-salt project.

By the time the industry approached the late 2000s, the results of the strategy were unmistakable. By 2007, international operations generated more than 70% of Schlumberger’s revenue—and an even higher share of profits. Competitors remained tied to the whipsaw economics of North American land drilling. Schlumberger had built a portfolio spread across national oil companies, long-cycle developments, and the world’s most technically demanding basins.

And the real advantage wasn’t just that they were global. It was how they went global. Schlumberger consistently entered during turmoil—Russia during Soviet collapse, the Middle East during the Gulf War, parts of Africa during political transitions. In those moments, assets were cheap, competitors were cautious, and governments were hungry for expertise. By the time stability returned, Schlumberger wasn’t an outsider trying to get in. They were already embedded.

They also learned the hard way that technology alone doesn’t win abroad. You needed cultural fluency, political navigation, and patience measured in decades. Schlumberger was playing the long game—and by 2008, they looked perfectly positioned for what should have been their next great wave: the shale revolution.

Instead, they missed it.

VII. The Shale Revolution Response & Cameron Acquisition (2008–2016)

George Mitchell had been fracturing shale in Texas for 17 years before anyone at Schlumberger truly treated it like the future. By 2008, the Barnett Shale was already producing more than 5% of America’s natural gas. And yet inside Schlumberger, the prevailing view was that horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing were a marginal play for marginal operators.

It would turn into one of the costliest misreads in the company’s history.

The irony is that Schlumberger wasn’t blindsided by the science. It had helped build the toolkit that made shale work—logging while drilling, geosteering, formation evaluation. But the company had tuned those tools for deepwater and international megaprojects, where a single well could cost $100 million and perfection mattered more than pace.

Shale was the opposite. It was manufacturing. Thousands of wells that might cost a few million dollars each, drilled by independents who didn’t want the most elegant solution—they wanted the fastest one that worked. In that world, “good enough, right now” beat “best-in-class, later.”

While Schlumberger stayed pointed at complex international work, Halliburton and Baker Hughes went all-in on North American land. They built hydraulic fracturing fleets, locked up sand and logistics, and wrapped the Permian, Eagle Ford, and Bakken in an operational machine designed for repetition. By 2014, Halliburton’s North American revenue had surpassed Schlumberger’s for the first time in decades. For a company used to being the default leader, it was a warning light.

Then came the wake-up call everyone in oil services heard at once. In November 2014, Halliburton announced it would acquire Baker Hughes for $34.6 billion. If it worked, the combined company would be a shale powerhouse—especially in pressure pumping, the fastest-growing part of the services stack. Schlumberger CEO Paal Kibsgaard later admitted, “We were slow to recognize the permanence of the shale transformation.”

Schlumberger’s response wasn’t to chase Halliburton into a brute-force fracking arms race. Instead, it made a different bet: vertical integration. On August 26, 2015, Schlumberger Limited and Cameron announced a definitive merger agreement to combine in a stock-and-cash transaction valued at about $14.8 billion. Cameron shareholders would receive 0.716 Schlumberger shares plus $14.44 in cash for each Cameron share, valuing Cameron at $66.36 a share—a 56% premium based on the companies’ closing share prices.

Cameron wasn’t a random target. It made the physical hardware that sits at the surface and controls the well: blowout preventers, wellheads, trees, valves. In other words, the equipment that complements Schlumberger’s subsurface brain. Kibsgaard pitched the combination as “pore-to-pipeline”—one company that could go from characterizing a reservoir to building the systems that bring hydrocarbons safely to the surface. Together, the companies would have had 2014 revenue of $59 billion, creating what Schlumberger framed as the industry’s first complete drilling and production systems provider.

And there was a second layer of strategy. Halliburton and Baker Hughes were trying to win by combining similar services and taking share in a business that could become commoditized. Schlumberger was trying to win by moving up the stack—toward equipment, systems, and outcomes. The company expected pretax synergies of about $300 million in the first year and $600 million in the second.

But the real brilliance was timing.

By August 2015, oil prices had collapsed from over $100 per barrel in 2014 to under $50. Cameron’s stock was down about 40% from its peak. Schlumberger was using a strong balance sheet to buy premium assets in a downturn, when competitors were retrenching and valuations were compressed.

The deal also gave Schlumberger a cleaner on-ramp to shale. Cameron’s pressure-control and surface systems were essential for the high-pressure, high-volume reality of unconventional drilling and completion. By buying Cameron, Schlumberger gained exposure to the shale machine without trying to build a massive fracturing fleet from scratch.

Integration mattered, too. Schlumberger didn’t want Cameron as a standalone hardware unit. It wanted Cameron as part of an end-to-end system. The OneSubsea joint venture—where Schlumberger already owned 40% through a 2013 deal with Cameron—became a platform for subsea integration. And more broadly, the company started tying surface equipment and downhole measurements into unified workflows, using digital models to optimize entire production systems rather than individual components.

At the same time, the Halliburton–Baker Hughes deal was buckling under its own weight. The Department of Justice raised concerns across numerous product lines. By April 2016, Halliburton abandoned the merger and paid Baker Hughes a $3.5 billion breakup fee.

The contrast couldn’t have been clearer. Halliburton pursued a horizontal merger that reduced competition and triggered prolonged regulatory resistance. Schlumberger pursued vertical integration that expanded capability—and it closed the Cameron acquisition in April 2016 with relatively limited regulatory friction.

Cameron also revealed something deeper about what Schlumberger wanted to become. This wasn’t just a service company trying to win more jobs. It was a technology company trying to own the full system. Service companies sell hours and equipment. Technology companies sell outcomes.

That mindset shaped what came next. Schlumberger pushed digital deeper into Cameron’s installed base, adding sensors, connectivity, and software layers to equipment that had historically been mechanical. The shale era had proven that technology could turn “impossible” resources into repeatable production. Now Schlumberger’s question shifted: if physics and computation could unlock shale, what else could they unlock?

For Schlumberger, the next answer would come from a place that once nearly broke it—Silicon Valley.

VIII. Digital Transformation & The SLB Rebrand (2016–Present)

In early 2022, Schlumberger’s executive team sat in Houston staring at a world that suddenly felt upside down. Tesla was worth more than ExxonMobil. Software companies were being valued like gravity didn’t apply to them, while oil service firms traded like yesterday’s business. ESG money was fleeing anything that looked, sounded, or smelled like “oil.”

CEO Olivier Le Peuch’s message was simple: if Schlumberger wanted to control its future, it couldn’t let the market keep defining it as a cyclical oilfield contractor. The company had to be understood—internally and externally—as what it had been quietly becoming for years: a technology company built around the subsurface.

The transformation didn’t start in 2022. But 2022 was the moment Schlumberger made it official. The company rebranded to “SLB,” dropping the long name that had defined it for nearly a century. It wasn’t about modern design or shorter URLs. It was a signal of intent: SLB wanted to be associated with data, automation, and engineering outcomes—not just oil.

The logic behind the shift was hiding in plain sight. For decades, Schlumberger had been collecting more subsurface information than anyone on earth—seismic surveys, well logs, production histories, reservoir models. It was an extraordinary advantage, but also an underused one. Too much of that knowledge lived in disconnected systems, legacy databases, and, yes, physical archives. The value wasn’t in having the data. The value was in making it usable.

That’s what the digital push was really about. In 2017, Schlumberger launched DELFI, a cognitive exploration and production environment built for the cloud. The ambition wasn’t to sell another piece of software. It was to make subsurface intelligence portable—so a team in Nigeria could work with the same tools and the same models as a team in the North Sea, and so geologists in Brazil could collaborate in real time with colleagues in Houston.

DELFI was also designed to be deliberately open. It ran across the major cloud providers—Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, and Amazon Web Services. In an industry known for closed ecosystems and proprietary formats, SLB was signaling that the platform mattered more than the lock-in. If the future was going to be data-driven, the winning system would be the one that could ingest anything, run anything, and output decisions fast.

By 2024, the digital strategy started to pull the rest of the portfolio into orbit. In April, SLB announced it would acquire ChampionX in an all-stock transaction. ChampionX shareholders would receive 0.735 shares of SLB common stock for each ChampionX share, and would own about 9% of SLB after closing. The point wasn’t simply to add another product line. ChampionX brought artificial lift and production chemicals—exactly the kind of production infrastructure that becomes far more valuable when it’s connected, instrumented, and optimized with software.

This is where SLB’s reinvention becomes easiest to picture. Sensors in the field feed operating data into DELFI. Models look for patterns humans miss. And when conditions change—when scale starts to build, when chemistry needs to be adjusted, when production can be stabilized—the system can recommend action immediately. SLB described it as moving toward autonomous optimization: fewer manual interventions, faster decisions, better recovery.

The digital shift also fit neatly with the other big force reshaping the industry: the energy transition. In 2020, Schlumberger launched Schlumberger New Energy to focus on lower-carbon technologies. It wasn’t a promise to abandon oil and gas. It was an acknowledgment that SLB’s core competency—understanding the subsurface—translated into new markets. Carbon capture and storage required the same geological confidence as exploration. Geothermal demanded the same drilling and completion expertise. Lithium extraction drew on similar production know-how.

SLB’s approach was pragmatic. The company believed hydrocarbons would remain essential for decades, but it also recognized its customers were under relentless pressure to reduce emissions. So the pitch became: help operators produce more efficiently and with lower intensity now, while building serious capabilities that could matter in a lower-carbon future.

That dual strategy showed up in areas like methane detection. Using tools like satellite imagery, drone surveys, and fixed sensors, SLB could help identify leaks at field scale. And the same analytics mindset—pattern recognition, prediction, optimization—could be applied to reducing emissions as naturally as it could be applied to optimizing production.

By the time the “SLB” name appeared, the company was already changing from the inside. It invested heavily in software talent and built remote operations centers where experts could monitor and support work around the world. From Houston, teams could help adjust drilling parameters in the North Sea, troubleshoot equipment issues in Nigeria, or refine production plans in Brazil. The capability became especially valuable during COVID-19, when travel restrictions made the old model—fly people to the rig, solve it on site—suddenly brittle.

The business model started evolving too. SLB pushed further into performance-based contracts, where it could be paid based on outcomes like production, rather than simply on equipment deployed or time billed. The appeal is obvious: it aligned incentives. SLB only won when the operator won—and it also rewarded SLB’s main advantage, which was increasingly its ability to squeeze better decisions out of data faster than anyone else.

By 2024, the numbers helped make the story credible. SLB’s digital and integration business was growing at double-digit rates with operating margins over 30%. Revenue rose 10% year over year, adjusted EBITDA increased 12%, and free cash flow reached $3.99 billion. For investors, that mix—growth, margin, and cash—looked a lot more like a technology company than a classic oilfield services firm.

And that’s the wager SLB is making now. Not that oil disappears tomorrow—it won’t. But that the scarcest resource in energy is shifting from hydrocarbons to certainty: better understanding of what’s underground, better control of complex systems, and better use of data at scale. In the 1920s, the Schlumberger brothers made the subsurface legible with electricity. In the 2020s, SLB is trying to make it programmable.

The question is whether the market will follow them there.

IX. Business Model & Competitive Moats

Walk into a modern drilling operations center and the scene is almost always the same: walls of screens, real-time feeds, engineers scanning curves and dashboards as if they’re running air traffic control. Look a little closer and you’ll notice something else—whether you’re in Houston, Aberdeen, or Abu Dhabi, a lot of what you’re looking at is powered by SLB. That kind of ubiquity doesn’t happen by accident. It’s the outcome of a business model built with the same mindset as a downhole tool: engineered, iterated, and designed to be hard to replace.

At a high level, SLB is organized around the life of a field. The company operates through four divisions: Digital & Integration, Reservoir Performance, Well Construction, and Production Systems. Together, they span field development and hydrocarbon production, carbon management, reservoir interpretation and data processing, and the services and equipment used to drill, complete, and improve wells. Any one of these segments could be a large standalone business. The advantage comes from how tightly they fit together.

Digital & Integration is the “brain.” This part of SLB doesn’t just sell software licenses—it sells a way of working. When an operator uses DELFI to plan wells or manage subsurface models, they’re plugging into workflows shaped by decades of SLB domain expertise. And once a company runs planning, interpretation, and collaboration through the same environment, switching becomes painful. It’s not just a contract you cancel. It’s data you have to migrate, teams you have to retrain, and real operational risk you take on in the middle of drilling campaigns. In oil, disruption is expensive—and that makes inertia a feature.

Reservoir Performance is where SLB’s original DNA still shows. This division includes wireline logging, testing, and stimulation—the core technologies that tell you what the rock is, what fluids are in it, and how it will behave when you try to produce it. The moat here isn’t only hardware. It’s interpretation. Plenty of companies can build tools that measure something downhole. Far fewer can reliably turn those measurements into decisions under pressure, across basins, across decades, and across messy real-world conditions. SLB’s advantage is the compounding library of “what this signal meant last time,” accumulated from a century of jobs.

Well Construction is the muscle: drilling services, measurements, and fluids—the work that turns a plan into a physical wellbore. This is where scale stops being a brag and starts being a weapon. Operating across more than 100 countries means SLB has seen almost every failure mode: unstable shale, lost circulation, high pressure, extreme temperature, corrosive environments. And when a team hits a problem in one basin, the company can often pull a solution from another. That’s a quiet network effect: lessons learned in one place become a playbook everywhere else.

Production Systems—supercharged by Cameron—covers what happens after the hole is drilled: completions, artificial lift, surface equipment, and the systems that control production. This segment captures SLB’s shift from selling individual services to selling a coordinated system. The pitch isn’t “here’s a piece of equipment.” It’s “here’s a production setup that works together”—and increasingly, one that can be instrumented, monitored, and optimized using digital workflows.

What makes this structure powerful is the portfolio effect. The four divisions don’t behave the same way across cycles. Digital & Integration tends to be higher margin and less capital intensive. Production Systems can be heavier on manufacturing and long-term projects, but it often produces steadier, contract-driven cash flow. Reservoir Performance and Well Construction are more exposed to activity swings, but they’re also the customer touchpoints that generate data, insight, and future pull-through for everything else.

Then there’s geography—one of SLB’s most underrated moats. The company’s international exposure isn’t just a footprint; it’s a stabilizer. When North American shale slows, production enhancement in the Middle East can accelerate. When one region stalls under politics or budgets, another can be in expansion mode. That ability to redeploy people and equipment—chasing returns across borders—is not just risk management. It’s how SLB keeps its machine running through cycles that break more domestically concentrated competitors.

But the strongest advantage might be the least visible: relationships that have been maintained for decades. For the largest national oil companies, SLB isn’t simply a vendor they rotate every year. It’s often a long-term technical partner. That trust is built the hard way—through thousands of jobs where the equipment worked, the interpretations held up, and the execution didn’t fail when the stakes were high.

All of that creates a subtle but powerful flywheel. Every well logged adds to SLB’s interpretation base. Every optimization job improves workflows. Every deployment generates operational feedback that feeds back into tools, models, and training. More work produces more learning; more learning produces better outcomes; better outcomes win more work. That cycle is difficult to copy because it requires global scale, deep technical credibility, and time.

This is why even strong competitors tend to run into the edges of SLB’s ecosystem. A startup can invent a clever tool, but it usually can’t deploy it broadly or support it across the world. A regional champion can execute locally, but it can’t compound learnings globally. And large peers like Halliburton or Baker Hughes can compete fiercely in individual service lines, but matching SLB’s end-to-end integration—subsurface interpretation through to production systems—remains a different challenge entirely.

It also changes how SLB gets paid. The company’s leverage comes from value, not day rates. When SLB can credibly argue it will improve recovery, reduce nonproductive time, or stabilize production, the conversation shifts away from “how much per tool” and toward “how much is this outcome worth.” That’s where pricing power comes from in oilfield services: not being cheaper, but being safer—and more productive.

The model has also been getting more recurring over time. Software, maintenance, and longer-term production arrangements can be less tied to pure drilling activity than classic service work. The more SLB’s offering looks like ongoing optimization rather than one-off jobs, the more it behaves like a through-cycle technology provider instead of a pure cyclical contractor.

Underneath it all is the same philosophy that has defined the company since Ridgefield: keep investing in the edge. SLB’s R&D intensity remains a meaningful commitment, and the spending doesn’t only happen in labs. The field itself is a massive, distributed experiment—thousands of deployments, constantly generating feedback about what breaks, what works, and what can be improved. That learning velocity is hard to replicate with centralized R&D alone.

And the talent system reinforces it. SLB still recruits petroleum engineers, but increasingly it also recruits software, data science, and AI talent—people who want to work on complex physical systems with global consequence. The problems are messy, high-stakes, and real. That’s a draw.

Put it together, and SLB ends up in a rare position. It’s not the cheapest provider. It’s not always the most specialized at a single narrow task. But it is the company that can connect the chain—exploration to production, surface to reservoir, data to decisions—at global scale.

Which brings us to where this starts to matter beyond oil. The more the world talks about carbon storage, geothermal, and subsurface energy systems, the more SLB’s core competency keeps showing up: measuring, modeling, and manipulating what’s underground. In that sense, the company’s moat isn’t just defensive. It’s portable.

And that portability is what makes the next question so interesting: if SLB’s advantage is the subsurface, how far can it stretch—before the industry, and the world, asks it to do something bigger than oil?

X. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

The room in Palo Alto was packed with venture capitalists and startup founders—an unusual crowd for an oilfield-services CEO. But when former SLB CEO Andrew Gould started talking about building moats that last a century, it got quiet.

“Everyone talks about disruption,” he said. “But Schlumberger has been the disruptor for ninety-seven years. Let me tell you how.”

Lesson 1: Technical Excellence Creates Compound Advantages

The Schlumberger brothers didn’t just invent electrical logging. They built a learning system that got smarter every time it touched a well. Each job added data. Each formation refined interpretation. Over decades, that advantage didn’t grow linearly—it compounded.

For founders, the takeaway is simple: build products that improve with use. Your tenth customer should get meaningfully more value than your first because you’ve learned from the first nine. That doesn’t happen by accident. It requires deliberate mechanisms to capture knowledge and feed it back into the product. At SLB, what looked like “overhead”—interpretation standards, training, and later digital workflows—was the moat being poured in real time.

Lesson 2: Geographic Arbitrage in B2B Markets

SLB’s international expansion wasn’t just about chasing revenue. It was a capability factory. Tools hardened in the North Sea could command premium pricing in easier basins. Lessons from Russian permafrost carried into Canada. Trust built with Saudi Aramco became a credential across the region.

The playbook is counterintuitive: go hard places early, when competition is low and customers are hungry for competence. Build solutions under extreme conditions. Then take those battle-tested capabilities into calmer markets, where they feel like overperformance customers are happy to pay for. It’s the opposite of “start easy, then expand,” but it builds defensibility from day one.

Lesson 3: Surviving Commodity Cycles Through Diversification

When oil prices collapsed in 2014, SLB’s stock fell sharply too. But the company stayed profitable through the downturn and kept generating cash. The reason wasn’t luck—it was diversification: across geographies, across service lines, and across customers. When North American drilling slowed, other regions and production-focused work carried more of the load. When exploration budgets tightened, optimization and production systems mattered more.

In cyclical industries, the lesson is to build a portfolio that naturally hedges itself. Don’t let the boom convince you to concentrate everything in whatever is hottest. Surviving the bust is the price of admission to see the next boom.

Lesson 4: Vertical Integration Versus Partnership

SLB’s Fairchild Semiconductor bet showed what happens when vertical integration isn’t adjacent. Cameron showed what happens when it is. Cameron’s products complemented SLB’s subsurface strengths and served overlapping customers. Fairchild lived in a different universe, with different economics and competitive clocks.

A useful framework: integrate when the combination creates unique value (when 1+1 can become 3). Partner when you simply need access (when 1+1 stays 2). And never integrate just to “capture supplier margin.” That’s one of the cleanest ways to buy yourself a problem.

Lesson 5: R&D Investment Through Downturns

SLB’s habit of investing through downturns is one of its most durable advantages. When competitors cut engineering teams, SLB used the moment to push its technical lead—hiring talent others were forced to let go and continuing to fund the next generation of tools and workflows.

For venture-backed companies, the translation is: raise when you can so you can invest when others can’t. For profitable companies, it’s simpler and harder: protect R&D as a principle, not a leftover. When the cycle turns down, the temptation to cut is overwhelming. That’s exactly why the advantage is available.

Lesson 6: Building Switching Costs in B2B

SLB doesn’t rely on handcuffs like extreme long-term contracts. It makes switching operationally painful. That stickiness tends to come from three places: workflow integration (the software becomes how the work gets done), accumulated data (history lives in the system), and human capital (teams are trained around the tools and methods).

If you’re building SaaS, this is the north star: don’t just win on features. Win on becoming the system of record. Features can be copied. A deeply embedded workflow is much harder to rip out.

Lesson 7: The M&A Strategy That Works

SLB has done hundreds of acquisitions, but the best ones follow a consistent logic: buy capability, not capacity. Acquire something that expands what you can do or how fast you can do it, not just more of the same. Integrate the technology aggressively, and be honest about whether the deal actually fits the mission.

A simple filter helps: only buy if it meaningfully accelerates your roadmap, unlocks customers you can’t otherwise reach, or strengthens your position against a real competitive threat. Everything else is usually a distraction wearing a suit.

Lesson 8: Family Control to Public Company Transition

For decades, the Schlumberger family maintained control even after going public, which enabled long-term thinking while still tapping public markets for capital. But the real success wasn’t the structure—it was that the family built an institution that could outlast family involvement. The culture became the continuity.

For founders, the lesson is two-sided: if you need long-term control to execute a long-term plan, be intentional about governance. But also invest in building something that can survive you. Ownership fades; culture endures.

Lesson 9: When to Disrupt Yourself

SLB was late to fully embrace how permanent shale would be, and it didn’t become “digital-first” overnight. But when it moved, it moved with force—reorganizing around software, building platforms, and reframing itself for a future that includes energy transition technologies.

The lesson is to watch for platform shifts that turn “impossible” into “inevitable.” Horizontal drilling did that for shale. Cloud computing did that for global collaboration. AI is doing it for automation. When that kind of shift arrives, don’t tiptoe—because your competitors won’t.

Lesson 10: Building for Century-Long Relevance

SLB has lived through world wars, repeated oil crashes, and major technology transitions. The throughline is how it defines itself: by capability, not by application. “Understanding the subsurface” travels. “Finding oil” doesn’t.

For founders trying to build something that lasts, that distinction matters. Define the mission broadly enough to evolve, but narrowly enough to stay coherent. SLB isn’t really a company about oil services; it’s a company about making the underground measurable, modelable, and actionable. That’s why it can keep showing up in new chapters.

The final takeaway from SLB’s century-long run is that technical excellence is only the start. The real edge comes from nurturing it into a system—one that learns faster than competitors, survives cycles, and keeps finding new places to apply the same core capability. In a world obsessed with disruption, there’s still a lot of power in building something that endures.

XI. Analysis & Investment Case

Picture an investment committee at a major sovereign wealth fund. Energy is back on the agenda. The portfolio manager pulls up SLB’s chart: still well below its 2022 high, even after a stretch of strong cash generation. “This is either the opportunity of the decade,” she says, “or we’re missing something fundamental about transition risk.”

Both can be true. Let’s look at the case from each side.

The Bull Case: Underinvestment Meets a Company Built for Hard Barrels

The arithmetic of oil is brutally simple. Global demand is around 100 million barrels a day. Existing fields decline every year. So even if demand never grows again, the world still has to replace millions of barrels per day annually just to stay flat.

But capital hasn’t followed that reality. Upstream investment is still materially below the last cycle’s highs. That gap—between what the world needs and what the industry is spending—tends to show up in one place first: oilfield services.

SLB’s pitch is that it’s positioned for exactly this kind of environment. Its growth has been driven by international markets, where projects are larger, longer-cycle, and where most of the remaining reserves sit. In its full-year results, international revenue rose 12%. Well Construction and Production Systems grew as well, with Production Systems up strongly, helped by subsea-related momentum. The takeaway isn’t the exact mix of percentages—it’s that SLB’s center of gravity is where global development spending is most likely to persist.

There’s also a strategic shift embedded in those results: SLB has been leaning harder into production and recovery. Instead of living and dying by drilling booms, it’s trying to build a steadier business around improving output from assets that already exist. The logic is straightforward. A huge share of wells produce below their potential, and operators have every incentive to squeeze more out of what they already drilled—especially in a world where new projects are slower to approve and harder to finance. In that world, optimization is not a “nice to have.” It’s a budget line that survives.

The ChampionX acquisition is meant to accelerate that move. Artificial lift and production chemicals are not flashy, but they sit right in the middle of day-to-day production performance. Pair them with SLB’s existing equipment, services, and digital workflows, and SLB’s goal is to offer something closer to a full production optimization platform than a collection of point products. SLB expected the transaction to close before the end of 2024, and it anticipated $400 million of annual pretax synergies within three years through revenue growth and cost savings.

If you buy the story, the bigger upside isn’t even the cost cuts. It’s what happens when SLB can sell integrated solutions instead of individual components—especially as more field operations become instrumented, connected, and managed through software.

That’s where digital becomes more than a buzzword. Digital revenue is attractive because it carries far higher incremental margins than traditional services. If digital becomes a larger share of the mix, you can get operating leverage that looks unusually “tech-like” for an industrial company. And that’s exactly the re-rating SLB is trying to earn.

Finally, there’s balance sheet optionality. With investment-grade ratings and more than $3 billion in annual free cash flow, SLB has the ability to invest through downturns, buy assets when others are forced sellers, and still return capital. Management’s plan to return $7 billion over 2024–2025 is intended to signal confidence that the cash engine is durable, not a one-year spike.

The Bear Case: Peak Demand, the Shale Blind Spot, and the Cost of Complexity

The existential question for oil services is simple: what if the long-term demand curve rolls over faster than expected?

EV adoption is rising. Renewables keep getting cheaper. Carbon policies keep tightening in major economies. If oil demand peaks around 2030—one of the more aggressive but widely discussed timelines—the entire sector risks becoming a shrinking pie. In that world, even the best operator can be fighting gravity.

SLB also has a very specific vulnerability: North America. The region is a large portion of global production, but a smaller portion of SLB’s revenue. That’s partly by design—SLB built its modern machine around international and offshore work—but it also means underexposure to shale, the industry’s most flexible, short-cycle source of supply. While SLB has made moves to address this, it remains less prominent in some of the most shale-centric service lines, like pressure pumping and land drilling, where competitors have historically had scale advantages.

Then there’s capital intensity. Even an “asset-light” narrative in oilfield services has limits. Equipment wears out. Technology refreshes. Manufacturing and service infrastructure must be maintained. If maintenance and growth capex remain meaningful, the gap between reported free cash flow and “through-cycle” free cash flow becomes a point investors debate—especially in a business where downturns can arrive suddenly.

Geopolitics is another real overhang. SLB operates where the oil is, and the oil is often in unstable places. That diversification is strategically valuable—until a sanctions regime, conflict, or political shift makes a market inaccessible or uneconomic. When a meaningful slice of revenue is tied to high-risk countries, investors tend to apply a discount because the downside can be abrupt.

And finally: competition doesn’t stand still. National oil companies have incentives to internalize more capability. Chinese service firms are improving and competing on price. Cloud and AI providers are increasingly present in energy workflows. SLB’s moats are real—but the bear case argues they are gradually eroding, especially at the digital layer where big tech has structural advantages.

Valuation and Multiples Analysis

At current prices, SLB looks inexpensive versus its own history and versus broad-market valuation levels. The market is effectively pricing in some combination of: lower margins, lower growth, or a shorter runway for oilfield services as a whole.

One plausible explanation is simply that the entire sector has been de-rated—partly because of ESG-driven capital flows and partly because investors don’t want to own long-duration oil exposure. If that’s what’s happening, then a company with strong cash generation and improving mix can look like a contrarian setup.

Competitive Positioning versus Peers

Against Halliburton, SLB’s advantage is the international footprint and the breadth of its integrated offering, particularly in digital. Halliburton is stronger in North American land intensity; SLB is built to win where projects are long-cycle and technically demanding.

Against Baker Hughes, the contrast is portfolio shape. Baker Hughes has more exposure to areas like turbomachinery and LNG that can look “transition-adjacent.” SLB’s argument is that its services-plus-systems approach, strengthened by Cameron, produces stronger returns through the core of the oil and gas value chain.

Against NOV, SLB looks less like a pure equipment cycle and more like a blended services, systems, and software company—more recurring pull-through, less dependence on a single category of capex.

The Next Decade: Three Scenarios

Scenario 1: Higher for Longer (40% probability)

Oil demand grows through 2035, service intensity rises, and SLB benefits from both volume and mix. Revenue compounds at high single digits, margins expand, and the stock re-rates. Total return: 300%+ over 10 years.

Scenario 2: Managed Transition (40% probability)

Oil demand plateaus around 2030 but remains elevated. SLB grows modestly, while carbon management and new energy initiatives become meaningful contributors. Returns are solid but not explosive. Total return: 150% over 10 years.

Scenario 3: Rapid Disruption (20% probability)

A faster-than-expected demand shock hits the core business, and new energy efforts don’t scale quickly enough to offset the decline. Valuation compresses and earnings fall. Total return: -30% over 10 years.

Put together, that yields a probability-weighted outcome that the committee can argue compares favorably to broader market expectations—if you’re willing to accept commodity sensitivity and policy risk.

The Investment Decision

SLB is a complicated investment in the most honest way. It’s a technology leader inside a cyclical industry. It’s a cash generator that still lives under the shadow of energy transition narratives. And it’s trying to be valued like a systems-and-software company while being judged like a traditional oilfield contractor.

It’s not built for investors who need smooth growth or who can’t own hydrocarbons on principle.

But for investors who believe oil and gas will remain essential for decades, who see value in technical differentiation, and who can tolerate volatility, SLB offers a particular kind of setup: a business with real competitive advantages, meaningful cash flow, and a valuation that suggests the market is still treating it like a melting ice cube.

The ultimate question isn’t whether oil has a future. It’s whether investors can separate their feelings about fossil fuels from the economics of a company that increasingly sells certainty, efficiency, and optimization—no matter what molecule happens to be flowing through the pipe.

XII. Epilogue & Reflections

If you stand in the old Pechelbronn field in Alsace—where this story began—you can still find the memorial marking the site of the first electric well log. The rigs are gone. The field was abandoned long ago, the oil drained out decades back. But what was born here didn’t run dry. The conviction that you can see through rock, that information can be more valuable than hydrocarbons, and that applied physics can rewrite an industry—those ideas are still at work.

So what would Conrad and Marcel Schlumberger think of SLB today?

They would recognize the essence immediately: measure what others can’t, interpret it better than anyone, and turn uncertainty into something you can act on. But the scale would feel almost absurd. Their early electrical readings—carefully taken, meter by meter—have evolved into a global machine that blends sensors, computing, and software into something closer to an operating system for the subsurface.

They might also be surprised that the company is still standing. The oilfield is a graveyard of once-great names. Some were acquired, others merged, others simply faded as the cycles turned and technology moved on. And yet SLB not only survived—it became the default. A company that started with two brothers and a voltmeter grew into a global institution, operating across more than 100 countries and employing over 100,000 people.

The deepest lesson in that arc isn’t really about oil. It’s about compound knowledge.

Every well logged added to an internal library of patterns and outcomes. Every failure became a lesson embedded into tools, workflows, training, and interpretation. Over time, SLB didn’t just accumulate technology; it accumulated understanding. And unlike a patent, that kind of asset doesn’t expire. It compounds.

That’s also why SLB’s story rhymes with some of the great B2B technology companies. Like Oracle or SAP, it built dominance by becoming embedded in how the work gets done. Like ASML or Synopsys, it sits at a chokepoint: a set of capabilities the rest of the industry can’t simply wish away. And like Dassault Systèmes or Ansys, it built a business around turning physics into models that engineers can use to make decisions.

But SLB has its own distinct playbook. It shows that hundred-year moats are possible if you treat reinvestment as a rule, not a nice-to-have. It shows that global diversification—often dismissed as unfocused—can be exactly what makes a company resilient enough to keep investing through the down cycles. And it shows that a family-founded company can transition into professional management without losing the cultural thread, as long as the thread is anchored in something real: technical excellence, field discipline, and a bias toward learning.

Then there’s the paradox of the present moment. The energy transition adds weight to everything SLB does, because the same competencies that helped find and produce hydrocarbons can also be used to store carbon, drill geothermal wells, and manage subsurface energy systems. The uncomfortable implication is that some of the companies best equipped to build parts of a lower-carbon future are the ones most associated with the high-carbon past.

Looking forward, the questions get sharper. Can a company built in the age of oil redefine itself for a world trying to use less of it? Can Western technology leadership hold up against rising national champions elsewhere? Can an industrial services business earn software-like valuation characteristics? The answers will shape SLB’s next chapter—and offer a template for any incumbent trying to evolve without losing its edge.

This story also says something about innovation itself. The Schlumberger brothers didn’t start out to build an empire. They started with a specific problem: how do you see underground without digging? That kind of grounded ambition—solve a real problem for real customers, then keep iterating—turned out to be more durable than any grand, abstract vision. In an era that celebrates disruption for its own sake, SLB is a reminder that relentless, practical progress can be just as revolutionary.

And through all of it, the human element never goes away. This company was shaped by people making hard calls in imperfect conditions: rebuilding through war, investing through downturns, admitting when a strategy was wrong, and pivoting when the industry changed underneath them. Leadership mattered when the company needed courage more than cleverness.

For investors and operators, SLB’s history reads like a long case study in capital allocation through cycles: when to buy in a downturn, when to cut distractions, when to protect R&D, and when to return cash. The wins are instructive. The mistakes—especially the Fairchild detour—are instructive, too.

As SLB heads into its next century, one question hangs over everything: will subsurface expertise remain a superpower in a world building more above-ground energy? SLB’s own history argues yes—not because oil lasts forever, but because the underlying capability travels. The company has already reinvented itself multiple times: from analog logs to digital data, from measurement to intervention, from tools to systems, from services to software. The energy transition is another reinvention—bigger, messier, and more politically charged than anything before it, but not outside the company’s pattern.