Intercontinental Exchange: From Energy Startup to Global Market Infrastructure Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s 1997, and a chemical engineer from Wisconsin walks into a dying energy exchange in Atlanta. The company is bleeding cash. The tech is dated. And the energy trading world still runs on phone calls, fax machines, and relationships—handshake deals brokered by people who know each other’s golf handicaps better than their own P&L.

Jeffrey Sprecher buys the whole thing for about a dollar, plus the promise to take on its debts. Not as a cute legend. As a reflection of what the business was actually worth at the time.

Now jump to today. That one-dollar rescue has become Intercontinental Exchange: a Fortune 500 market infrastructure giant valued at over $100 billion. ICE owns the New York Stock Exchange—maybe the most iconic financial brand on Earth. It helps set the Brent crude benchmark that prices a huge share of the world’s traded oil. It clears an enormous portion of global energy derivatives. It runs major clearinghouses. And, in a twist no one would have predicted from an energy exchange startup, it powers mortgage technology that touches millions of American homebuyers.

So how does a company go from a struggling, almost-empty exchange to owning the NYSE? How did Sprecher build one of the most effective acquisition machines in modern finance—through multiple market cycles—while high-flying rivals like Enron burned down in spectacular fashion? And how do you buy your way across exchanges, clearing, and data without falling into the classic conglomerate trap: complexity, culture clash, and value destruction?

That’s what this story is really about. It’s about spotting digitization opportunities before “digital transformation” became a boardroom cliché. It’s about building network effects in markets that insisted they didn’t need them. It’s about the quiet power of owning the unglamorous layers—clearing, data, and post-trade infrastructure—that make the whole system work. And it’s about a culture that kept its startup sharpness even as it absorbed institutions many times its size.

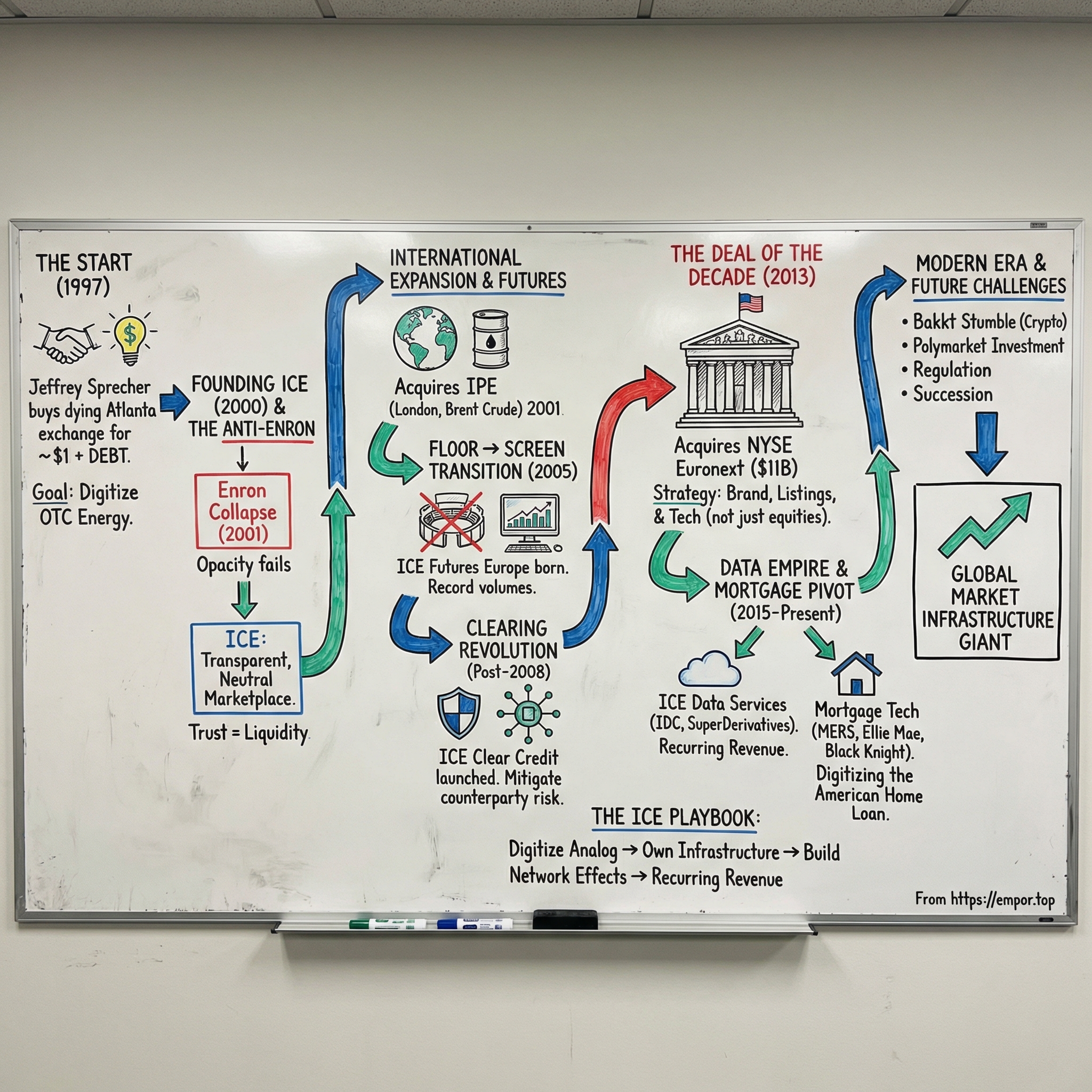

We’ll tell it in three acts. First: ICE’s origins in energy, where it built its core playbook by dragging a phone-and-fax market onto the internet. Second: the empire-building phase, where ICE expands across the Atlantic and, eventually, lands the deal of the decade with the NYSE. Third: the transformation into a broader data and technology platform—one that reaches beyond trading floors into analytics, valuation, and even the mortgage process itself.

II. The Founder's Journey & Pre-ICE Context

Jeffrey Sprecher didn’t set out to remake global finance. He started, in 1983, as a freshly minted chemical engineer from the University of Wisconsin, taking a job at Trane—the heating and air conditioning manufacturer—in La Crosse. The work was about power plant efficiency: steam turbines, cooling systems, the physical math of turning fuel into reliable power. Not glamorous. But it gave him something most future exchange operators never get: an instinct for how energy behaves in the real world.

That matters, because later, when energy got financialized and traders started treating megawatts like just another line item on a screen, Sprecher still thought in constraints—temperature, pressure, geography, and the fact that electricity can’t be stockpiled like barrels of oil. He understood the commodity before it became the instrument.

Then he headed west. In the early 1990s, California was in the middle of a high-stakes experiment: deregulating power markets. Sprecher became president of Western Power Group, developing, owning, and operating large central-station power plants. He was building generation at the exact moment electricity began shifting from a regulated utility product into something you could trade.

And once you could trade it, the market’s biggest weakness became obvious: there was no good way to do it.

By the mid-1990s, energy trading was massive—and painfully primitive. A single deal could take hours of phone calls across multiple counterparties. Price discovery was more scavenger hunt than science; to get a rough read on where natural gas was trading, you might call a dozen firms and still not trust the answer. Confirmations ran on fax machines and overnight couriers. Contracts piled up in paper stacks and took weeks to reconcile. For a market with hundreds of billions of dollars of notional value flowing through it, the tooling looked like it hadn’t been upgraded since the 1950s.

In 1997, Sprecher found a distressed little company in Atlanta: the Continental Power Exchange, or CPEX. It was an early attempt at electronic energy trading, but it was undercapitalized, poorly managed, and built on tech that was already aging out. Sprecher bought it with a simple, contrarian goal: bring over-the-counter energy trading onto the internet.

The price tag became legend—“the one-dollar exchange.” Sprecher has said he doesn’t even remember whether it was literally a dollar or closer to a thousand, but always with the same punchline: he also assumed the company’s debts. The exact number isn’t the point. The point is what he bought: a broken platform, a broken business, and a chance to start over.

And start over he did. The technical recommendation from the team was extreme: scrap everything and rebuild from scratch as an internet-based platform, using Oracle databases and Java. Sprecher said yes. That decision—made in the late 1990s, when “web-based trading” still sounded like a risky experiment—became the technical bedrock for what ICE would eventually run at global scale.

The rebuild hurt. During the transition, the company lost every customer. The staff dropped from about thirty people to just six. It was basically a tiny group in an Atlanta office trying to create the future of trading for an industry that didn’t believe the future had arrived.

For the next few years, Sprecher lived in the wilderness: rewriting the stack, selling the vision, flying around to energy firms and banks, and taking meeting after meeting that ended with a polite no. Phone brokers and floor traders had been doing business the same way for decades, and they had no interest in a screen-based alternative. Banks weren’t convinced an engineer without a Wall Street pedigree could build a credible exchange.

But while the market shrugged, Sprecher kept accumulating the things that actually matter at the beginning of a network: working software, a small team that could ship, and early relationships with the handful of institutions starting to suspect that the internet wasn’t a fad—it was an inevitability.

III. Founding ICE: The Anti-Enron Story

The year 2000 didn’t feel like the start of a new market era. It felt like peak internet mania. The dot-com bubble was still inflating, and Enron was being treated like the future of American business—America’s seventh-largest company, a Wall Street darling, and the loudest voice in energy trading.

Meanwhile, in an unglamorous Atlanta office park, Jeff Sprecher was putting together something that looked, on the surface, almost absurd: a real attempt to build an electronic marketplace that didn’t depend on being the biggest player in the room.

In May 2000, IntercontinentalExchange was formally established. The founding shareholders weren’t just a few early believers—they were some of the largest energy companies and global banks on the planet: Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, BP, Total, Shell, Deutsche Bank, Société Générale, and UniCredit.

This wasn’t a normal funding round. Sprecher wasn’t simply raising money; he was buying commitment. He convinced the most powerful institutions in the market to become equity partners in the exchange—ownership in return for participation. If they owned the rails, they’d run their trains on them.

He gave away roughly 80 percent of the company. Not as an act of surrender, but as strategy. Sprecher understood something that every exchange eventually learns the hard way: technology doesn’t create a market. Liquidity does. A trading platform with great software and no flow is decoration. A platform with flow becomes the default.

Continental Power Exchange contributed its assets—most importantly, the trading technology Sprecher’s small team had rebuilt from scratch—along with its liabilities, in exchange for a minority equity stake. Seven major commodities market participants also acquired equity interests. The logic was clean: align the exchange with its customers so tightly that the network effect could actually ignite.

And at the exact same time, Enron was building the opposite.

EnronOnline wasn’t a neutral venue. Enron’s model was to sit in the middle of every trade—to buy from every seller and sell to every buyer. Enron wasn’t facilitating the market; it was trying to be the market. By 2001, EnronOnline was processing about $2.5 billion a day in transactions, and the story wrote itself: explosive growth, massive reported profits, and analysts cheering on the machine.

But Sprecher saw the weakness. Enron’s design required enormous balance sheet capacity and concentrated counterparty risk inside one firm. If Enron ever wobbled, the whole marketplace wobbled with it—because Enron was the counterparty behind everything. ICE took the opposite stance: it would be a neutral marketplace where buyers and sellers traded directly, and ICE would simply match the transaction and take a fee. Sprecher’s pitch was blunt and calming: “We are Switzerland. We do not compete with you.”

The cultural contrast couldn’t have been sharper. Enron had a massive Houston trading floor, loud ambition, and marketing firepower—spending about $100 million promoting EnronOnline. ICE was a small Atlanta team that could have held an all-hands in a conference room, with essentially no marketing budget at all.

But the biggest difference wasn’t money or swagger. It was information.

Enron benefited from opacity. ICE went the other way and published everything—trades, bids, offers—full transparency for participants. In a market where information advantage had long been the profit engine, that was a radical choice. It was also a trust-building machine.

Then came December 2, 2001. Enron filed for bankruptcy.

A roughly $60 billion company that dominated energy trading collapsed almost overnight. Trades were left hanging. Counterparties suddenly faced exposure to a firm that no longer existed. And the market learned—violently—what concentrated counterparty risk actually feels like.

For ICE, this was the hinge moment. Traders who had been skeptical of electronic markets didn’t suddenly become tech enthusiasts. They became pragmatists. They needed a new venue, fast, and ICE was the credible alternative standing in the right place at the right time with the right structure. Volumes surged, and the upstart that had been fighting for attention against a giant was suddenly a primary destination for energy trading.

Sprecher didn’t celebrate. When asked, he framed Enron’s demise as validation of the marketplace model: transparent, neutral infrastructure beats a system that depends on one firm’s balance sheet and reputation. The lesson, in his view, wasn’t just that Enron had failed—it was that trying to be the market was structurally brittle.

That distinction—build infrastructure, don’t become the counterparty—became the organizing principle for what ICE built next.

IV. International Expansion & The Futures Playbook

Even before the Enron collapse had fully rippled through the market, Sprecher was already looking across the Atlantic. In June 2001, ICE acquired the London-based International Petroleum Exchange, the IPE—Europe’s leading open-outcry energy futures exchange.

This wasn’t some minor bolt-on. Back in 1988, the IPE had launched Brent crude futures, the contract that became the global benchmark for pricing roughly two-thirds of the world’s internationally traded oil. If you controlled Brent, you helped define the reference price for the most important commodity on Earth. For a small, Atlanta-based, internet-first exchange to buy this cornerstone of European energy finance was bold to the point of seeming presumptuous.

And the politics were just as intense as the prize.

Sprecher flew to London to face the IPE’s board and its trading community—people who didn’t just prefer the floor, but treated it as sacred. The IPE pit, near St. Katharine’s docks across from the Tower of London, was a loud, physical ritual: traders in colored jackets shouting, signaling, reading one another’s faces and posture as much as the market. Many had built entire careers on that skillset. A screen wasn’t an upgrade. It was an extinction event.

So when Sprecher made it clear that the endgame was electronic trading, the response was immediate and furious. Floor traders threatened strikes and protests. One trader told the Financial Times that Sprecher would “destroy 400 years of tradition.” The outrage wasn’t really about tradition, of course. It was about livelihoods and identity—and the uncomfortable reality that electronic markets don’t just change how trading happens. They change who gets to do it.

But Sprecher had a different audience too: the owners of the IPE, largely major energy companies. They were watching what was happening across derivatives markets—including at LIFFE—and they could see where this was going. Electronic trading meant longer hours, faster execution, broader participation, and global access. The question wasn’t whether the floor would lose to the screen. The question was who would manage the transition—and whether the IPE would lead it or be dragged into it.

ICE didn’t try to flip a switch overnight. It ran a classic adoption wedge: put electronic trading next to the floor and let the incentives do the work. Screens could trade beyond pit hours. That meant Asia could participate in Brent at times when the London building was dark. At first, the electronic session was a sideshow. Then it started to grow. Then it became the main event. By early 2005, electronic volume had surpassed floor volume.

In February 2005, ICE made the call that everyone warned them not to make: it fully transitioned the IPE crude and refined oil markets—including Brent and Gasoil futures—to electronic trading. The last day on the floor was raw. Traders wore black armbands. Cameras captured the final moments. Some veterans openly wept. It felt like a funeral for a way of life.

And then something important happened: the market didn’t die. It expanded.

Within weeks, volume on the electronic platform was higher than the floor had ever handled. The operation that became ICE Futures Europe went on to produce eighteen consecutive record years of trading activity—a result that turned all those painful decisions into a blueprint.

With that proof in hand, ICE shifted from insurgent to consolidator. In 2007, it acquired the New York Board of Trade, NYBOT, for $1 billion—bringing iconic “softs” contracts like sugar, coffee, cocoa, and cotton into the empire. These were some of America’s oldest futures markets, with roots going back to the 1800s, still relying on floor-based habits that looked increasingly out of place in a global, electronic world. ICE applied the same formula: digitize, optimize, and open the market to anyone, anywhere.

More acquisitions followed, including the Winnipeg Commodity Exchange and Creditex, a credit derivatives broker. The pattern was becoming clear: buy an important market with entrenched liquidity, modernize the plumbing, and scale it globally.

But the real strategic leap in this era wasn’t just buying exchanges. It was building and owning clearing.

ICE Clear Europe, launched in 2008, became the first new clearing house in London in over a century. Clearing is the unglamorous machinery that makes markets trustworthy: it steps between buyer and seller, guarantees performance, and manages default risk. It’s also the place where the lessons of Enron become institutional memory. When counterparty risk explodes, clearing is how you contain the blast radius.

Owning clearing meant ICE didn’t just run the marketplace—it controlled what happened after the trade, too. And it created a deep network effect: as more products cleared through ICE Clear Europe, it became more efficient for members to consolidate risk management and margin in one place. That kind of infrastructure is hard to replicate and even harder to dislodge.

In November 2005, ICE went public, listing at $26 per share and roughly a $2 billion market cap. The IPO showed just how powerful this model could be: despite being only a few years old, ICE was already posting operating margins north of 50 percent. By June 2006, it joined the Russell 1000.

The company that had once dwindled to six employees and zero customers was now one of the most profitable businesses in finance. And Sprecher—having proved he could buy tradition, digitize it, and make it grow—was starting to look at a target that would make everything so far feel like the opening act.

V. The NYSE Acquisition: The Deal of the Decade

On the morning of December 20, 2012, a headline hit that rewired the map of global markets. Intercontinental Exchange announced it would buy NYSE Euronext in a stock-and-cash deal valued at about $8.2 billion. The New York Stock Exchange—an institution more than two centuries old, and the most recognizable symbol of American capitalism—was about to be owned by a twelve-year-old company from Atlanta that most people couldn’t have picked out of a lineup. It felt like watching a startup buy a national monument.

The twist is that ICE had already tried to get this exact prize. Just eighteen months earlier, ICE and Nasdaq teamed up on an unsolicited bid for NYSE Euronext worth about $11 billion. Regulators blocked it over fears of a stock listings monopoly, and NYSE CEO Duncan Niederauer dismissed the offer as “strategically unattractive.” Now Sprecher was back, solo, with a friendlier offer at a lower headline price—and Niederauer was supporting it. What changed wasn’t the asset. It was the situation.

Between those two attempts, NYSE Euronext had taken a beating. A proposed merger with Deutsche Börse—announced as a roughly $10 billion combination—was stopped by European regulators in February 2012, largely over derivatives concentration concerns. The company was left bruised and in limbo. Equity trading volumes were still stuck around where they’d been in 2007, even as electronic market-making squeezed spreads and dark pools siphoned flow. The exchange that once embodied financial power was starting to look more like a museum: iconic, important, and increasingly hard to grow.

Sprecher didn’t show up with a grand vision to “transform” the NYSE. He showed up with a plan and a scalpel.

The offer gave NYSE Euronext shareholders choices: $33.12 in cash per share, or 0.2581 ICE shares, or a mix of $11.27 in cash plus 0.1703 ICE shares. The all-cash option was a hefty premium to the prior day’s close, and the overall deal skewed about two-thirds stock and one-third cash. When the acquisition finally closed on November 13, 2013—after regulators on both sides of the Atlantic signed off—the total value had effectively climbed to around $11 billion as ICE’s stock rose.

But the real strategy wasn’t in the spreadsheet. It was in what Sprecher openly said he wasn’t buying.

ICE wasn’t paying up to “fix” NYSE cash equities trading—a brutal, low-margin business where competition and speed had pushed profits toward zero. Instead, ICE wanted three things.

First: LIFFE, the London derivatives exchange, which would give ICE a powerful position in European interest-rate and commodity derivatives.

Second: the NYSE listing franchise and brand—prestige that companies still paid for, because a NYSE listing isn’t just market access, it’s a signal.

Third: technology and infrastructure that could be reused across ICE’s growing footprint.

Then came integration—and ICE did something unusual for an Atlanta-born consolidator. Instead of trying to steamroll a 220-year-old institution with startup culture, Sprecher protected the parts that made it valuable. ICE kept dual headquarters in Atlanta and New York, with the New York team anchored in the iconic building at 11 Wall Street. Sprecher stayed on as chairman and CEO. Niederauer became president. And the relationships—listed companies, market participants, the ecosystem around the NYSE—were treated as untouchable. ICE understood that the NYSE wasn’t just systems and contracts. It was trust, history, and a brand that still carried real pricing power.

The endgame snapped into focus in 2014. ICE spun off Euronext in an IPO that valued the European exchange operator at roughly 1.9 billion euros. Europe got what it wanted: a standalone European exchange, no longer under American ownership. ICE kept what it actually came for: the NYSE and LIFFE, with LIFFE rebranded as ICE Futures Europe. It was corporate surgery at its cleanest—buy the whole package, then separate and return the pieces you don’t need, while keeping the core assets that compound for decades.

And then Sprecher made a decision that revealed just how well he understood symbolism as strategy. He kept the NYSE trading floor open.

This is the same executive who had digitized everything else he touched. The IPE floor in London? Closed. The NYBOT floor in Manhattan? Closed. ICE’s playbook was screens, not shouting. But the NYSE floor wasn’t just an operating model. It was theater, and the kind that sells. The opening bell, the cameras, the blue jackets, the façade at 11 Wall Street—those weren’t inefficiencies to optimize away. They were part of the product. Companies pay a premium to list on the NYSE in part because of that ritual and recognition. Sprecher didn’t just buy an exchange. He bought an icon—and he knew better than to modernize it out of its value.

VI. Building the Data Empire

The roots of ICE’s data ambitions went back further than most investors noticed. In 2003, ICE formed a data subsidiary on a simple insight: as markets moved from voices on phones to orders on screens, the exhaust of trading—every bid, offer, and print—would become a product of its own. Market participants didn’t just need execution. They needed pricing, risk tools, and audit-ready records. The open question was whether ICE could turn that constant stream of information into a business that scaled.

The defining bet came in late 2015, when ICE won a bidding war against Nasdaq and Markit for Interactive Data Corporation in a deal valued at about $5.2 billion, paid in a mix of cash and ICE stock. Interactive Data, or IDC, wasn’t famous outside finance, but it sat in the critical path of how the industry understood value. Thousands of institutions subscribed to its fixed income evaluations, reference data, real-time feeds, infrastructure services, and analytics.

IDC’s superpower was pricing the stuff that didn’t trade. Think of a municipal bond from a small county in Nebraska. It might only change hands a few times a year, which makes the “last trade” price nearly meaningless for daily portfolio marks. IDC built models to estimate a fair value every day anyway, using a wide set of signals—rates, spreads, comparable trades, and broader economic indicators. For mutual funds, pension funds, and insurers sitting on huge books of less-liquid bonds, that kind of daily valuation wasn’t a nice-to-have. Regulators and auditors effectively made it table stakes. And when a product is table stakes, customers don’t churn.

Around the same time, ICE also bought SuperDerivatives, which provided derivatives valuation and risk analytics. Then, in June 2016, ICE rolled these pieces together under an expanded ICE Data Services umbrella—combining exchange data, valuations, analytics, and software from the NYSE, SuperDerivatives, and IDC. This wasn’t a logo swap. It signaled a real shift: ICE was building a second engine alongside trading—one based on subscriptions.

That matters because transaction revenue and subscription revenue behave very differently. Exchanges make money when people trade, which means results can surge in volatile markets and soften when things get quiet. Data, valuations, and analytics get paid for every day, in every market mood, because institutions need them continuously—whether they’re trading actively or barely trading at all. More predictability means steadier cash flows and, typically, a business the market is willing to value more highly.

By the late 2010s, ICE’s data revenues had grown past $2 billion annually, with operating margins approaching 60 percent. The company that began as an energy trading upstart was starting to look like a data business that also happened to own major exchanges. Sprecher had clearly internalized what Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters had long demonstrated: in modern finance, the information layer can be as valuable—or more valuable—than the transactions underneath it.

The competitive landscape was, and still is, formidable. Bloomberg dominates with hundreds of thousands of terminals and more than $10 billion in annual revenue. S&P Global controls critical infrastructure like ratings and indices. LSEG, after buying Refinitiv, commands an enormous data footprint. But ICE has something structurally different: it produces data at the source of price discovery. Every trade on an ICE exchange, every cleared position, and—eventually—every step in a mortgage workflow generates first-party data. Competitors can aggregate, normalize, and repackage, but they can’t recreate origination. In a world full of secondhand information, that “data from the rails” advantage may be ICE’s most underappreciated asset.

VII. The Clearing Revolution & Risk Management

When Lehman Brothers collapsed on September 15, 2008, it didn’t just take down a storied investment bank. It exposed how alarmingly fragile the plumbing of global finance had become. Watching from Atlanta, Jeff Sprecher saw catastrophe, yes—but also confirmation of a belief he’d carried for years: bilateral derivatives markets were a maze of hidden, poorly managed counterparty risk.

Here’s the core problem in plain English. Before the crisis, banks made enormous numbers of over-the-counter derivatives trades directly with one another. Each trade created a promise: I owe you if X happens, you owe me if Y happens. Multiply that across thousands of contracts, dozens of counterparties, and years of maturities, and you get a web so dense that nobody can see the true exposure until it’s too late.

So when Lehman failed, the panic wasn’t just “Lehman is gone.” It was “What does Lehman owe me? What do I owe others because Lehman is gone? And who’s going to fail next when everyone tries to unwind at once?” In markets built on confidence, not knowing is enough to freeze everything.

Central clearing is the antidote. A clearinghouse steps into the middle of every trade—becoming the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer. Instead of a tangled chain of Bank A owing Bank B owing Bank C, everyone faces the clearinghouse. The clearinghouse nets exposures, marks positions, collects margin, and maintains a waterfall of financial safeguards designed to absorb losses if a member defaults. In effect, it turns a messy network of private promises into a managed system.

And in 2008, that difference wasn’t theoretical. While Wall Street was scrambling to map exposures, cleared markets kept operating. The clearing model did what it was built to do: contain a failure rather than spread it. For Sprecher, it became the most persuasive argument he could make—because the market had just watched the alternative nearly break the world.

Then came the regulatory tailwind. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 pushed standardized OTC derivatives toward mandatory central clearing. A huge portion of what had been privately negotiated, opaque risk between banks would now need to move into regulated clearinghouses. The rules were changing. The question became: who would own the pipes?

Sprecher’s move was classic ICE: don’t wait for customers to choose you—make them partners in choosing you. The principal backers for ICE Clear Credit were the same institutions most scarred by the crisis: Bank of America, Barclays, Citi, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, and UBS. Each invested $35 million for a stake, and ICE agreed to share profits with them. The pitch was almost too direct to be anything but effective: you’re going to have to clear these trades somewhere. Wouldn’t you rather own part of where they clear?

ICE’s credit default swap clearing business launched in March 2009—barely six months after Lehman. By the end of that year, ICE was clearing about $10 trillion in notional CDS volume. The very banks that had once been wary of central clearing now had both a risk-based reason and an economic reason to make it work.

Over time, ICE built a global clearing footprint. Today, it operates six central clearing houses: ICE Clear U.S., ICE Clear Europe, ICE Clear Singapore, ICE Clear Credit, ICE Clear Netherlands, and ICE NGX. And clearing doesn’t monetize like an exchange floor where revenue rises and falls with trading activity. It throws off multiple streams: fees on trades cleared, fees on margin tied to open positions that stick around, and investment income on the collateral members post. That last piece becomes especially meaningful when rates are higher, because a clearinghouse can be sitting on a very large pool of cash and securities.

Most importantly, clearing creates one of the strongest moats in financial services. Starting a new clearinghouse isn’t just a software problem. It’s a regulatory gauntlet. It’s capital requirements. It’s governance. And it’s the near-impossible task of convincing enough major participants to move together to create a viable marketplace.

But the real lock-in is even simpler: switching. If a bank has thousands of open positions at ICE Clear, it can’t casually “try a competitor” the way it might test a new trading venue. Moving a portfolio of cleared derivatives is operationally complex, legally messy, and risk-manager nightmare fuel. Once you’re embedded, you tend to stay embedded.

This is the ICE pattern at its most powerful: build the neutral infrastructure, make it indispensable, and then let the network effects do what marketing never can.

VIII. The Mortgage Technology Pivot

While Silicon Valley obsessed over blockchain and robo-advisors in the mid-2010s, Jeff Sprecher started fixating on something far less fashionable: the American mortgage.

From his vantage point, it looked like an industry stuck in amber. The basic workflow of getting a mortgage hadn’t meaningfully changed since the 1970s. It still took roughly 45 to 60 days, cost about $8,000 per loan to originate, and produced mountains of paperwork. In a world where you could trade massive volumes of energy derivatives in milliseconds, buying a home still meant sitting at a table with a notary and a stack of documents that few people truly read cover to cover.

ICE’s entry point wasn’t a consumer-facing app or a shiny fintech brand. It was infrastructure.

In 2016, ICE acquired the Mortgage Electronic Registrations System, or MERS. It wasn’t a headline-grabbing deal, but it was foundational. MERS tracked the servicing rights and beneficial ownership of around 60 percent of U.S. mortgages—about 75 million loans. It was the industry’s system of record for who owned what in an $11 trillion market. Homeowners rarely knew it existed. Lenders, servicers, and investors couldn’t function without it.

In 2019, ICE followed with Simplifile, which digitized a different bottleneck: recording mortgage documents with county governments. That sounds trivial until you zoom out. The U.S. has roughly 3,600 recording jurisdictions, each with its own rules, forms, fees, and procedures. Some could accept e-recordings. Others still required paper delivered by courier. Simplifile had spent years building the connections and integrations county by county—the kind of slow, unglamorous network build that’s painful to recreate and incredibly hard to displace once it’s in place.

Then came the keystone acquisition: Ellie Mae, bought in 2020 for $11 billion from Thoma Bravo. Ellie Mae’s Encompass platform was used by more than 3,000 lenders and supported the origination of roughly 40 percent of all U.S. mortgages. Encompass ran the workflow end to end—applications, credit, document generation, underwriting, compliance, and closing. With MERS for ownership tracking, Simplifile for county recording, and Ellie Mae for origination, ICE wasn’t collecting random mortgage assets. It was assembling a full, digital mortgage lifecycle.

The biggest swing came next. In September 2023, ICE completed its $11.9 billion acquisition of Black Knight, whose systems were used by many of the country’s largest mortgage servicers. The Federal Trade Commission challenged the deal on antitrust grounds, arguing ICE would control too much of the mortgage technology stack. ICE agreed to divest certain overlapping assets, and the transaction ultimately closed. With Black Knight’s servicing technology and analytics added to the portfolio, ICE Mortgage Technology now touches nearly every step of the mortgage journey—from application, to closing, to servicing, and into secondary market activity.

ICE has been clear about what it’s trying to do. The company wants to shrink the mortgage timeline from about two months to roughly two weeks, and cut origination costs from around $8,000 to about $2,600 per loan. It has pegged the total addressable market at $14 billion and described the opportunity as still early in a long analog-to-digital conversion. Today, the mortgage technology segment brings in roughly $2 billion in annual revenue, about 22 percent of ICE’s total net revenue.

And ICE is investing to make this a durable pillar, not an experiment. In January 2025, it bought the 52-acre Merrill Lynch Deerwood Park North campus in Jacksonville for $42 million, with total investment expected to exceed $100 million. The site is set to become the mortgage technology division’s headquarters, retaining more than 1,500 jobs and adding another 500. That same year, United Wholesale Mortgage—the nation’s largest mortgage lender—signed a long-term agreement to license ICE’s MSP servicing system for in-house operations, a meaningful signal that the stack was gaining traction with the biggest players.

Of course, mortgages come with an obvious cyclical problem: when rates rise, refinancing dries up and originations slow, which means fewer loans moving through the system. But Sprecher’s view is that the cycle actually strengthens the long-term thesis. When volumes fall, lenders get squeezed—and cost-cutting stops being optional. If ICE can make the process faster and cheaper, downturns become selling seasons. Each quarter of weak volume is another quarter where institutions feel forced to modernize, setting the platform up to benefit when the rate cycle eventually turns.

To critics, the pivot looks like a strange detour—an exchange operator wandering into housing finance. Sprecher sees the same story he’s been telling since the beginning. Mortgages are another massive market with outdated workflows, fragmented participants, and an urgent need for digitization. The playbook doesn’t change: build the rails, make yourself essential, and earn recurring revenue from an ecosystem that can’t operate without the infrastructure underneath it.

IX. Playbook: The ICE Way

Over a quarter century, ICE has refined a playbook so consistent it feels less like strategy and more like muscle memory. Plenty of companies talk about “digital transformation.” ICE just keeps doing it—market by market, cycle by cycle—with a discipline that can look almost boring from the outside. That boringness is the edge.

First: digitize the analog.

Energy trading in 2000 was phones and faxes. The IPE in 2005 was open-outcry pits. Credit derivatives after 2008 were a web of bilateral promises. Mortgages in 2020 were paperwork and handoffs. In each case, ICE took an industry that relied on manual workflows and turned it into software.

The nuance is how it did it. Sprecher rarely tried to win through confrontation. He won by making the electronic alternative so obviously better that resisting became expensive. More hours, more transparency, faster execution, lower friction, better capital efficiency—benefits participants could feel immediately. People didn’t switch because ICE told them to. They switched because staying put meant falling behind.

Second: acquire with a purpose—and don’t drift.

ICE has done more than twenty major acquisitions, totaling over $40 billion. That kind of deal volume usually ends in an overextended empire, messy integrations, and a confused strategy. ICE’s version has been unusually coherent. The deals tend to land in one of three buckets: expand liquidity and network effects through exchanges, control post-trade infrastructure through clearing, or monetize information and workflow through data and technology. The pattern isn’t “buy growth.” It’s “buy the next piece of the system.”

And the integration approach is as standardized as the deal thesis. ICE moves quickly to identify synergies—often aiming at a meaningful slice of the acquired cost base—and it works to migrate technology onto its infrastructure on an 18-month timeline. But it protects what matters most in a network business: customer trust and participation. Cost saves are valuable; lost customers are catastrophic. ICE behaves like a company that has internalized that difference.

Third: build businesses where the flywheel gets heavier as it spins.

Every major ICE segment has the same underlying physics. More participants on an exchange improves liquidity and price discovery, which attracts more participants. More products cleared through a clearinghouse improves netting and capital efficiency for members, which pulls in more flow. More mortgages moving through a workflow platform generates better data and more standardized processes, which makes the platform more useful, which draws in more users. These aren’t just moats. They’re moats that can widen over time.

Fourth: own the unglamorous layer.

The flashy part of markets is execution—the trade. ICE’s most durable power has often come from what happens after the trade: clearing, settlement, data, and workflow. Those layers are regulated, operationally embedded, and sticky. Once a firm’s risk management and compliance processes are built around your plumbing, ripping it out isn’t a vendor change. It’s a high-risk internal overhaul. That creates a kind of lock-in that’s hard to buy and even harder to attack.

Fifth: turn volatile activity into recurring revenue.

Trading fees rise and fall with market volume. Data subscriptions pay every day. Clearing economics grow with open interest, not just daily churn. Software licenses renew. Over time, ICE has deliberately increased the share of the business that behaves more like subscriptions than tolls. By 2025, recurring revenues made up well over half of ICE’s total, shifting the company’s profile from “cyclical exchange operator” toward something closer to a mission-critical enterprise platform—still tied to markets, but less dependent on any single quarter’s trading mood.

Finally, there’s culture—lean, integrated, and allergic to bloat.

Despite being a Fortune 500 company, ICE has kept an operating style that feels closer to an Atlanta startup than a Wall Street institution. Sprecher is known for flying commercial. There’s no obsession with executive perks. And structurally, ICE runs as an integrated company, not a loose holding vehicle. Technology built for one market gets reused in another. Clearing and risk expertise informs how they think about adjacent workflows. Data created in one part of the system becomes a product in another.

That’s the ICE way: build the rails, make them essential, and keep stacking businesses on top that get stickier—and more valuable—the longer customers stay.

X. Modern Era & Future Challenges

The Bakkt saga is ICE’s most visible stumble—and maybe its most useful one. Launched in 2018 with real fanfare, Bakkt was meant to do for bitcoin what ICE had done for energy and derivatives: take a chaotic market and wrap it in institutional-grade infrastructure. The flagship idea was physically settled bitcoin futures. Jeff Sprecher even installed his wife, Kelly Loeffler, as CEO—a choice that drew attention and skepticism in equal measure.

But the market didn’t cooperate. Bakkt’s bitcoin futures never attracted the kind of volume needed to make an exchange business work. The institutions ICE expected to show up largely didn’t—at least not through this channel, and not yet. Then Bakkt broadened into a consumer app in 2020 that tried to be several things at once: crypto wallet, payments product, and loyalty-program hub. Instead of ICE’s usual surgical focus, it felt like a grab bag.

When Bakkt went public via SPAC in 2021 at a $2.1 billion valuation, the story was priced for a breakout. It never came. By 2024, the stock had lost the vast majority of its value.

The takeaway was crisp. ICE’s playbook is lethal in mature markets that need modernization: markets with real institutional participants, clear rules, and proven demand. It’s far less reliable in markets where the participants, the regulation, and even the product definition are still in flux. Crypto in 2018 wasn’t energy in 1999. In Bakkt, ICE tried to institutionalize a market before institutions were ready to meet it there.

Since then, ICE has looked more cautious—and more like itself. In October 2025, the company announced an investment of up to $2 billion in Polymarket at an $8 billion valuation, along with plans to distribute Polymarket’s event-driven data through ICE’s existing data infrastructure. Instead of building a prediction market from scratch and praying liquidity would appear, ICE backed the category leader and plugged it into its distribution machine. It echoed the original ICE approach: align with what’s already working, then scale it with better rails.

Then, on January 8, 2025, ICE acquired the American Financial Exchange, or AFX—an electronic exchange for direct lending and borrowing among American banks and financial institutions. AFX operates AMERIBOR, an interest rate benchmark based on the actual unsecured borrowing costs of more than 1,000 American banks that together represent about a quarter of U.S. banking sector assets. ICE said the deal wasn’t expected to materially affect 2025 financials or its capital return plans. But strategically, it was pure vintage ICE: find a real market with real participants, then apply technology, distribution, and infrastructure to make it bigger and stickier.

Meanwhile, the competitive map hasn’t gotten any friendlier. CME Group is still the heavyweight in financial futures, especially interest rates and equity index derivatives. Nasdaq keeps pushing hard in exchange technology and market surveillance. London Stock Exchange Group, supercharged by its Refinitiv acquisition, is a major force in data and analytics. Deutsche Börse controls Eurex and substantial European clearing infrastructure. These are not competitors you out-innovate with a single product launch.

And the threats aren’t only other exchanges. Cloud giants like Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure are building deeper financial services capabilities that could, over time, reduce the friction of launching new market and data offerings. Banks continue to internalize more flow through internal crossing networks and systematic internalizers, keeping trades off public venues. Geopolitical fragmentation is also pushing countries toward domestic market infrastructure instead of relying on global platforms—an underappreciated ceiling on how far “one global set of rails” can stretch.

Mortgage technology is ICE’s most obvious near-term pressure point. Higher interest rates have pushed origination volumes well below peak levels, which compresses the transaction-based revenue that moves through the platform. ICE’s counterargument has been consistent: downturns force modernization. When lenders are squeezed, cost reduction stops being an initiative and becomes survival. ICE still frames the long-term revenue opportunity as billions above current levels, but the cycle dictates how quickly the platform can compound.

One area that could surprise to the upside is environmental markets. ICE already runs the leading emissions trading venue in Europe, including benchmark EU Emissions Allowance contracts. As carbon pricing regimes expand and tighten—across the EU, the UK, and parts of Asia—this has the ingredients of another ICE-style franchise. Carbon markets need the same things every major commodity market needs: price discovery, clearing, data, and compliance infrastructure. ICE already has all four.

Underneath all of this, the technology agenda keeps moving. ICE has continued investing in cloud migration, artificial intelligence, and machine learning across the company. The applications are practical: more dynamic clearing risk models that can stress-test portfolios faster, better detection of anomalous trading behavior, and more automation in mortgage underwriting that could compress decisions dramatically. ICE has also explored 24/7 trading for tokenized securities—an idea that, if it ever becomes mainstream, would stretch the concept of a “trading day” and blur the boundary between traditional and digital market infrastructure.

Finally, there’s the question every founder-led company eventually faces: succession. Sprecher has been the strategic architect for ICE from day one, and his mix of engineering pragmatism, financial discipline, and focus on network effects is deeply imprinted on how the company operates. President Ben Jackson has become increasingly prominent publicly, and ICE has a deep bench of divisional leadership. Still, replacing a founder after more than twenty-five years is never a routine handoff. For investors, it’s a watch item—not because ICE lacks talent, but because culture and judgment are part of the moat, and those are harder to transfer than any asset on the balance sheet.

XI. Analysis & Investment Case

ICE brings in about $8 billion a year in net revenue, and it comes from three very different engines. Just over half is still the core exchange business—futures, options, and cash equities. About a quarter comes from Fixed Income and Data Services: subscriptions, valuations, and analytics. And the remaining slice comes from Mortgage Technology, where ICE earns software and transaction fees across the mortgage lifecycle.

For investors, the real story isn’t the top line. It’s the mix.

A decade ago, ICE looked like a classic exchange operator: great business, but earnings that could swing with volatility and trading volumes. Today, more than half of ICE’s revenue is recurring—data subscriptions, clearing-related revenue, and software licenses that renew whether markets are calm or chaotic. That move from “paid when people trade” to “paid because people must operate” is the biggest quality upgrade in ICE’s financial history—and a big part of why the company now gets talked about less like a cyclical exchange and more like market infrastructure.

The profitability follows from that position. Exchange margins have stayed consistently above 50 percent, and the data and mortgage businesses have been moving in the same direction as they scale. Free cash flow conversion has run at roughly a third of revenue—around $3 billion a year—which helps explain how ICE has managed an unusual balancing act: returning more than $15 billion to shareholders through dividends and buybacks since the NYSE deal, while also spending more than $40 billion on acquisitions. Most companies pick one lane. ICE has been able to drive both.

Recent results show the machine still has torque. In the third quarter of 2025, ICE posted record adjusted EPS of $1.71, up 10 percent year over year, on net revenues of $2.4 billion. Expenses were held to $1.2 billion, a reminder of how much operating leverage is baked into the model once the platform is built. Across full-year 2025, ICE set record trading volumes in commodities, energy, and interest rate markets, with futures and options average daily volume up 14 percent for the year and a notable jump in December. The fourth quarter 2025 earnings report—scheduled for February 5, 2026—was expected to continue that theme. And if you zoom out, the point is consistency: quarter after quarter, ICE has shown it can deliver, even as the mix shifts and different segments take turns leading.

The balance sheet is the tradeoff. ICE carries meaningful debt, largely because it built this company through big, deliberate swings—Ellie Mae and Black Knight being the clearest examples. Management has emphasized deleveraging, and investment-grade credit ratings keep its funding costs favorable. The debt looks manageable against ICE’s cash flow, but it does put a governor on near-term deal size. Until leverage comes down further, it’s more reasonable to expect tuck-in acquisitions and partnerships than another NYSE-scale move.

The bull case is the cleanest version of the ICE story: long runway, compounding advantages. Markets keep digitizing. Clearing continues to expand, pushed by regulation and pulled by capital efficiency. Data becomes more valuable as the world fragments and compliance demands rise. And mortgages remain a giant, inefficient workflow that is still early in its analog-to-digital transition. ICE itself has argued the addressable markets across its businesses exceed $100 billion a year, with ICE still holding only a single-digit share—meaning there’s room to grow without needing heroic assumptions. Add in optionality around carbon markets, newer market formats like prediction markets, and potential expansion of mortgage tech beyond the U.S., and you get upside that doesn’t have to be “core” to matter.

The bear case is real, and it’s not one thing—it’s many things. Regulation is the obvious one. Exchanges and clearinghouses are quasi-utilities, and when they look too dominant or too profitable, governments tend to intervene. That can show up as divestitures, fee pressure, or rules like interoperability that weaken network effects. Technology disruption is another: cloud-native competitors can start cheaper, and distributed ledger ideas still hang around as a possible path to settlement models that reduce the role of traditional intermediaries. Market structure changes matter too: more private-market funding means fewer IPOs, direct listings can reduce the traditional listing funnel, and passive investing reshapes volume and liquidity patterns. And then there’s leadership risk. Sprecher, born in 1955, has been the architect from day one; succession at a founder-led infrastructure company is rarely a simple baton pass.

If you put frameworks on it, ICE has multiple durable “powers.” Network effects show up in exchanges and clearing—more participants create better liquidity and better netting, which attracts more participants. Switching costs are massive in clearing and mortgages, where ICE becomes embedded in risk systems and operational workflows. Scale economies are real in data, where the heavy lift is collecting and processing information once, then selling it to many. And there’s a historical counter-positioning angle: early on, ICE’s electronic-first model let it do things legacy exchanges couldn’t do without cannibalizing their own floor-based economics.

A Porter's Five Forces view lands in a similar place. Clearing is brutally hard to enter—capital, regulation, and the liquidity bootstrapping problem keep most would-be challengers out. ICE has strong pricing power in benchmark products like Brent, where substitutes are limited. Supplier power is low because ICE controls most of its core infrastructure. Substitutes vary, but for clearing and benchmark data they’re generally limited. Rivalry is intense—CME, Nasdaq, LSEG, Deutsche Börse—but it’s mostly rational rivalry among a handful of giants with differentiated strongholds.

The valuation question, then, becomes one of identity: is ICE an exchange, a data company, or a fintech platform? A sum-of-the-parts approach can make a case for meaningful value—exchange comps for the exchange business, more software-like multiples for data, and fintech-adjacent thinking for mortgage tech once the cycle normalizes. But the integrated model may be worth more than a simple add-up, because the cross-segment data and distribution advantages are hard for pure plays to replicate.

At around 24 times forward earnings, the stock trades at a premium to the broader market—fairly reflecting quality and durability—but it doesn’t obviously bake in a full rebound in mortgage activity or a step-change in data growth. Shareholder returns add a steady floor: roughly a 1.5 percent dividend yield, plus ongoing buybacks that have reduced the share count by a couple percentage points a year.

If you’re monitoring the story quarter to quarter, two metrics are especially revealing.

First: recurring revenue growth. It’s the cleanest signal that ICE’s transformation—from volatility-driven transaction income to infrastructure-like subscriptions and workflow revenue—is continuing. Mid-single-digit growth is fine, but faster growth would signal real acceleration, especially in mortgage technology as the rate cycle eventually turns.

Second: open interest across ICE’s clearinghouses. Open interest is the stock of outstanding positions, and it tends to be stickier than daily volume. It drives clearing economics even when markets are quiet, and rising open interest often reflects genuine adoption rather than churn. Together, recurring revenue growth and clearing open interest tell you whether ICE’s flywheel is spinning faster—or simply coasting.

XII. Epilogue & Lessons

Stand on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange today and it still feels like the center of gravity for global capitalism—traders in jackets, cameras, the opening bell, the whole ritual. And yet the company that owns this two-century-old institution didn’t even exist when Google was founded. That mismatch is the point. ICE is one of the clearest modern examples of how a business can start in the unglamorous corners of an industry, compound quietly, and then end up owning the most iconic asset in the category.

Jeff Sprecher saw something that most people in markets either forget or never learn: trading is not the product. Trust is. Information is. Risk management is. Liquidity is. Matching buyers and sellers is the easy part—software can do that. The hard part is building a venue that participants believe in, where prices are credible, exposures are controlled, and the market is deep enough that everyone can get done what they need to get done. ICE didn’t win by being louder or flashier. It won by building the infrastructure layer beneath modern finance and making it indispensable.

ICE’s timing was also a superpower. When it began pulling energy trading onto the internet around 2000, “fintech” wasn’t a category. Cloud computing wasn’t an enterprise default. The smartphone era hadn’t arrived. The tech ICE used wasn’t magical; it was usable. What mattered was that Sprecher applied it to massive, analog markets at the moment they were ready—sometimes reluctantly—to change. Once liquidity begins to concentrate on an electronic venue, the advantage compounds in a way competitors can’t easily undo. Anyone trying to take share runs into the same brutal reality: how do you persuade participants to leave a liquid market for an empty one? Liquidity is the asset, and it’s the hardest one to manufacture.

Then there’s ICE’s acquisition record—rare not because it’s aggressive, but because it’s coherent. ICE didn’t buy companies just to get bigger. It bought to complete networks. Each deal either deepened liquidity, pushed ICE further down the stack into clearing and post-trade, expanded the data layer, or digitized another massive workflow like mortgages. The pattern is consistent enough that you can almost predict the next move: not random diversification, but another piece of the system that makes the whole platform stickier and more defensible.

A few lessons from the ICE story travel well beyond exchanges.

First, timing often beats technical brilliance. ICE used mainstream tools—Java, databases, the internet—and aimed them at markets that were still running on phones and fax machines. The innovation wasn’t the technology. It was the moment and the market choice. Many companies fail not because their product is bad, but because they’re too early or too late. ICE was early enough to build the network, and late enough that the market could actually adopt.

Second, own the boring infrastructure. Clearing, settlement plumbing, reference data, valuation services, mortgage workflows—these don’t make for glamorous headlines. They also tend to be where competition is weakest and switching costs are highest. Few founders dream of building a clearinghouse. Even fewer want to integrate with thousands of county recording offices. ICE built moats in places most people ignored.

Third, let network effects do the heavy lifting. ICE didn’t build its franchises through massive marketing budgets. It didn’t need to. Once a market hits critical mass, liquidity becomes the marketing. Every additional participant improves the experience for the next participant. Over two decades, that flywheel becomes extremely hard to stop.

Fourth, keep startup discipline even when you’re the incumbent. ICE’s frugality and integrated operating model aren’t cute cultural quirks; they’re strategic defenses against bureaucracy. It’s one thing to build a fast, focused company. It’s another to keep it fast after you’ve bought the NYSE, built global clearinghouses, and layered in data and mortgage platforms. ICE has tried—successfully more often than not—to stay lean where large institutions usually get soft.

Fifth, have the patience to run the same playbook for a quarter century. ICE didn’t reinvent itself every few years to stay interesting. It kept stacking advantages: digitize, acquire liquidity, own post-trade, monetize data, repeat. In a world trained to chase the next shiny opportunity, that kind of consistency is a competitive advantage.

The Bakkt episode is the necessary counterweight. Even great playbooks have edges. ICE’s approach works best where there’s already a real market with real participants who desperately need better infrastructure. It’s far less effective when the market itself is still being defined and demand is still speculative. Knowing where your strategy fails is part of what makes the rest of it work.

So what comes next for market infrastructure? The borders keep shifting. Big tech is deeper in financial services. Banks keep internalizing flow. New market formats—prediction markets, tokenized securities, potentially 24/7 trading—keep probing the edges of today’s structure. Artificial intelligence will reshape how risk is measured and how decisions get made. The landscape a decade from now will not look like the landscape today.

But the most durable part of the ICE story is also the simplest: it owns the pipes. No matter what form markets take—public or private, centralized or distributed—transactions still need to clear, risk still needs to be managed, and participants still need trusted data. ICE has spent decades positioning itself at the center of all three. The plumbing will need maintenance long after the plumber retires. And ICE owns the pipes.

XIII. Recent News

ICE entered 2026 with real operational momentum. Full-year 2025 trading volumes hit records across nearly every major product category, with futures and options average daily volume up 14 percent year over year. The finish was especially strong: December average daily volume jumped 19 percent, and ICE set all-time highs across commodities, energy, and interest rates.

Financially, the machine kept humming. Third quarter 2025 adjusted earnings per share reached a record $1.71, up 10 percent year over year, on net revenues of $2.4 billion. Recurring revenue grew 5 percent, continuing the steady shift toward more predictable, subscription-like income. The fourth quarter 2025 earnings call, scheduled for February 5, 2026, was expected to reflect continued strength in exchanges and data, while mortgage technology worked through the same rate-sensitive environment affecting the broader housing market.

On the strategy front, 2025 brought a few moves that fit the ICE pattern: expand the rails, then monetize the flow. In January, ICE acquired the American Financial Exchange, bringing AMERIBOR—a credit-sensitive interbank benchmark—into the portfolio. AMERIBOR is used by more than 1,000 American banks. The deal wasn’t expected to materially move the financials, but it extended ICE’s reach into interbank lending and benchmarks, another slice of infrastructure that tends to get stickier over time.

Then came the most surprising headline of the year. In October 2025, ICE announced an investment of up to $2 billion in Polymarket at an $8 billion valuation. Prediction markets were emerging as a meaningful new category, and ICE didn’t try to brute-force a new platform into existence. Instead, it backed the category leader—an approach that looked like a direct lesson from Bakkt. The deal also included plans to distribute Polymarket’s event-driven data through ICE’s existing data infrastructure, putting ICE Data Services’ reach to work in a new kind of market data product.

Mortgage technology, meanwhile, kept building institutional adoption even with originations under pressure. United Wholesale Mortgage, the nation’s largest mortgage lender by volume, signed a long-term agreement to license ICE’s MSP servicing system for in-house servicing. Bright MLS also announced an integration of ICE Mortgage Technology’s Paragon Connect into its broader technology ecosystem. The signal in both deals was the same: even when the market slows, the push to modernize doesn’t stop—it often accelerates.

And ICE kept investing accordingly. Its planned investment of more than $100 million into the Jacksonville campus, internally dubbed Project Paper Company, underscored long-term confidence in mortgage digitization. The facility is expected to retain more than 1,500 existing jobs and add 500 new positions over seven years—management’s way of saying this opportunity is measured in decades, not quarters.

XIV. Links & Resources

If you want to go deeper, here are the primary sources and a few great reads that provide context on electronic trading and modern market structure:

- ICE Investor Relations and SEC Filings

- ICE Q3 2025 Earnings Release

- ICE Full Year 2025 Volume Statistics

- UWM Selects ICE Mortgage Technology

- Intercontinental Exchange on Wikipedia

- "Dark Pools" by Scott Patterson — a fast, inside look at the rise of electronic trading

- "Flash Boys" by Michael Lewis — a narrative tour through high-frequency trading and market structure

- "The Man Who Solved the Market" by Gregory Zuckerman — the story of how data-driven finance went mainstream

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music