Dell Technologies: The Ultimate Private Equity Playbook

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

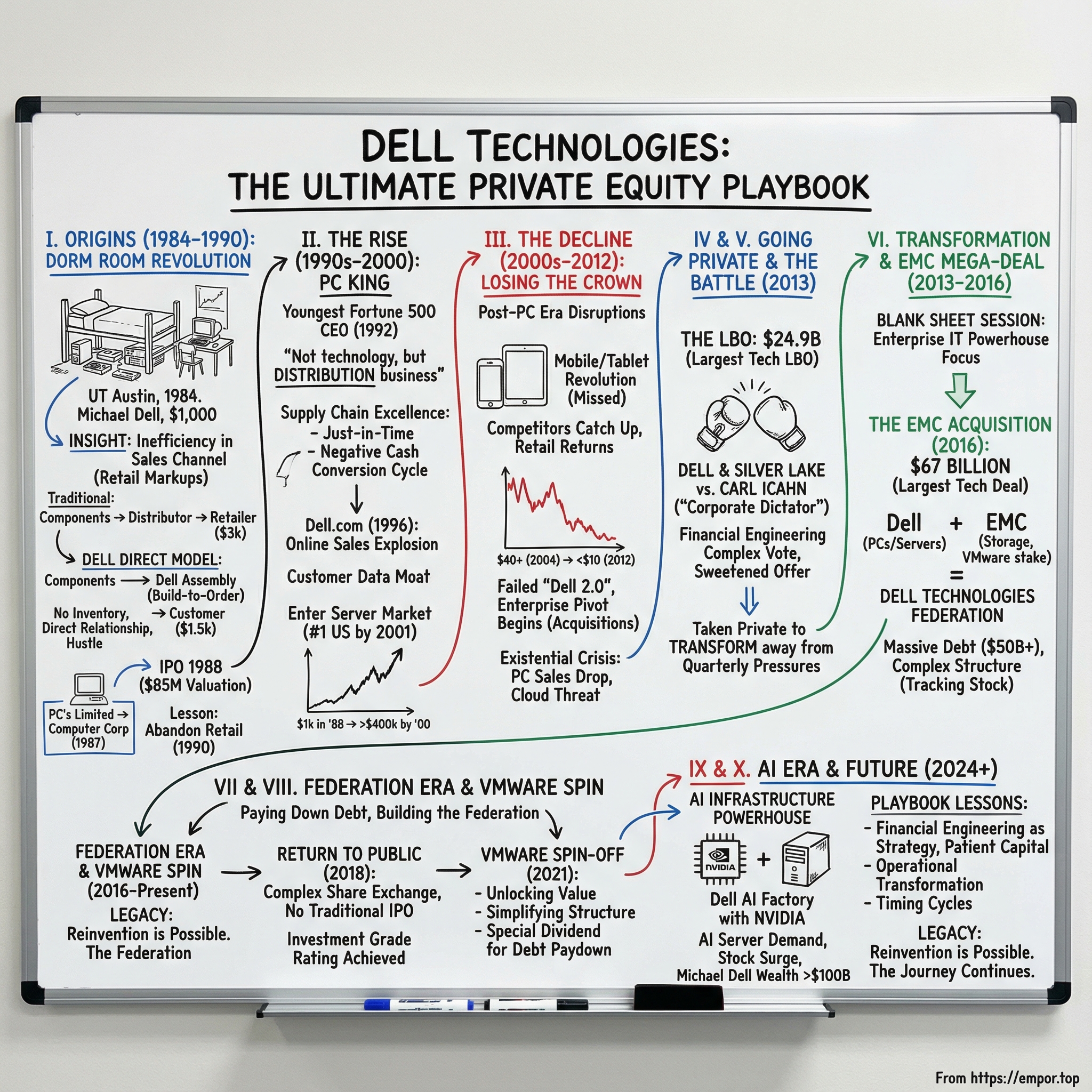

Picture this: it’s September 2013 in Round Rock, Texas. Michael Dell has just done the thing everyone said he couldn’t do.

After months of public, bruising combat with Carl Icahn—who blasted him as a “corporate dictator” pulling off “the ultimate insider trade”—Dell wins. The deal goes through. Dell Computer is no longer a public company. It’s now private again, taken out in a $24.9 billion leveraged buyout, the biggest tech LBO since the financial crisis.

And here’s the real bet: this wasn’t just a financial transaction. Michael Dell was putting his name, his reputation, and essentially his entire fortune behind one conviction—that away from the quarterly earnings spotlight, he could rebuild Dell into something that could actually win in the post-PC world.

What happens next doesn’t just change Dell. It reshapes the private equity playbook.

This is the story of how a college dropout became the youngest Fortune 500 CEO, then watched the ground shift under him as the industry moved on. It’s the story of a comeback built not on a new gadget, but on a reinvention—part strategy, part stubbornness, part financial engineering. And it leads to something almost unthinkable: Dell orchestrating the $67 billion acquisition of EMC, the largest technology acquisition ever.

Along the way, there are activist wars, tracking-stock complexity, and a level of deal-making that can make even seasoned Wall Street pros reach for a whiteboard. By 2023, Michael Dell and Silver Lake were estimated to have earned around $70 billion from the broader move.

The reason the Dell story matters is that it’s rare in tech: a founder doesn’t just disrupt an industry once. He disrupts it, loses the crown when the world changes, and then finds a way to reinvent the company anyway—using the tools of private equity and capital structure as aggressively as he once used the direct-to-customer model.

Four themes will carry us through. First, the direct model: the simple insight that rewired how computers were built, sold, and delivered. Second, the decision to go private—and the fight it ignited. Third, the EMC mega-merger that turned Dell from a PC maker into an enterprise IT heavyweight. And fourth, the financial engineering that made the whole machine work.

Buckle up. This is four decades of tech history told through one company—equal parts innovation, corporate warfare, and high-stakes reinvention.

II. Origins: The Dorm Room Revolution (1984-1990)

January 1984, University of Texas at Austin. Michael Dell is a freshman on the pre-med track—at least, that’s the story his parents believe. Then he hears footsteps in the hallway. Another surprise visit.

So he does what any determined 19-year-old entrepreneur would do: he starts hiding evidence. Computer parts get shoved under the bed, into closets, anywhere they won’t be seen. His parents think he’s tinkering. They’re worried it’s becoming a distraction.

What they don’t realize is that their son isn’t just tinkering. He’s already spotted something most of the computer industry is missing.

Back then, the attention was on the machines: faster chips, bigger hard drives, better specs. Michael’s obsession was different. He was looking at how computers moved from factory to customer—and noticing how much money (and time) got burned along the way.

An IBM PC might sell in a store for around $3,000. Michael realized he could buy the parts, assemble the computer himself, and sell it directly for about $1,500—cheaper, and often better configured for what the customer actually wanted.

The idea was almost offensively simple: cut out the middlemen. No distributors taking a slice. No retail markups. No piles of inventory sitting around getting older, less valuable, and harder to sell. Build the computer after the order comes in, then ship it straight to the customer.

In a world where components depreciated fast, that wasn’t just a clever sales tactic. It was a fundamentally better way to run the business.

By May 1984, with $1,000 in capital, Dell incorporated the company as PC’s Limited. The “factory” wasn’t a factory at all—Michael later described it as “three guys with screwdrivers,” operating out of a condo. But the small scale was the point. This model didn’t require a giant retail footprint. It required speed, customization, and relentless execution.

And Michael moved fast. One early power move: getting a vendor license to bid on State of Texas contracts. Suddenly, this tiny operation could compete for government business alongside companies that looked untouchable.

The growth came almost immediately. Within months, PC’s Limited was doing roughly $50,000 to $80,000 in sales of upgraded PCs and components. Michael was, in effect, running a real company while still “going to class.” That situation doesn’t last long.

He made the call every ambitious founder eventually faces: he dropped out to focus on the business full-time.

Later, he’d say, “My parents went crazy.” His dad was an orthodontist. His mom was a stockbroker. From their perspective, their son was walking away from stability for the chaos of selling computers. From Michael’s perspective, the personal computer boom was just getting started—and the incumbents were lumbering through it with the wrong system.

As the company grew, the model kept proving itself. By 1987, now operating as Dell Computer Corporation, Dell opened international operations in the UK. It was the beginning of a global push built on the same engine: direct sales, build-to-order, and a tighter feedback loop with customers than any retailer could offer.

In 1988, Dell went public, raising $30 million and hitting an $85 million valuation. Four years earlier, it had been a $1,000 idea and a dorm room full of parts. Now Michael Dell, at 23, was running a publicly traded company.

Then came the test that clarified everything.

In 1990, under pressure from analysts and board members who believed Dell needed a retail presence to “really compete,” the company tried selling through warehouse clubs and computer superstores. It went badly. The second Dell stepped into retail, it inherited all the problems the direct model was built to avoid: inventory risk, slower cycles, weaker customer relationships, and less control over the experience.

So Michael pulled back. Dell abandoned indirect sales and recommitted to direct. “We had to go back to our roots,” he later said. And the lesson stuck: Dell’s advantage wasn’t just building computers. It was the system—how the computers were sold, built, and delivered.

By the end of 1990, Dell had gone from a dorm room hustle to a company doing more than $500 million in revenue. The foundation was in place: a new distribution model, a CEO who understood that the channel could be the strategy, and a market about to explode. The kid hiding computer parts from his parents was building one of the most consequential business models in tech.

III. The Rise: Becoming the PC King (1990s-2000)

Dell’s rise in the 1990s happened so quickly it made the whole industry look flat-footed. In 1992—just eight years after that dorm-room hustle—Dell Computer Corporation landed on the Fortune 500. Michael Dell was 27. The youngest CEO ever to run a Fortune 500 company. Suddenly, the college dropout from Houston wasn’t a quirky upstart anymore; he was a reference point.

But the real edge wasn’t Michael’s age. It was his clarity about what the PC business had become.

In 1993, he stood in front of analysts and said the quiet part out loud: “This isn’t a technology business anymore. It’s a distribution business.”

That line was basically a declaration of war on the way the incumbents thought. IBM, Compaq, and HP still acted like PCs were differentiated machines—won through proprietary engineering, big R&D budgets, and brand. Dell looked at the same market and saw something else: commoditization. Intel made the processors. Microsoft made the operating system. Seagate and Western Digital made the drives. If the guts were increasingly the same, then the winner wouldn’t be the company with the fanciest box. It would be the company with the best system.

So Dell built a system.

The next evolution wasn’t a new product. It was an operating machine that looked less like a traditional tech company and more like world-class manufacturing. Dell pushed just-in-time to an extreme. Instead of piling up components in warehouses, Dell kept inventory light and moved fast. Parts came in, machines went out. The goal was simple: don’t let rapidly depreciating components sit still long enough to become a problem.

That pace created a structural advantage competitors struggled to copy. Dell could price aggressively without getting trapped by old inventory. It could keep specs fresh because the line didn’t have weeks—or months—of yesterday’s parts waiting to be sold. And it tightened cash flow, too, because the direct model meant Dell often got paid by customers before it had to pay suppliers.

Then the internet arrived, and it was like gasoline on a fire.

In 1996, Dell launched Dell.com and leaned into online sales early, using the web not as a marketing brochure but as a core part of the direct engine. Customers could configure the exact machine they wanted, place the order immediately, and track it end-to-end. The computer wasn’t “a Dell.” It was their Dell.

Sales ramped fast. Within 18 months, Dell.com was generating about $1 million a day. By 1999, it was doing around $35 million a day. And the more customers bought direct, the more Dell gained something that its retail-based rivals didn’t have: a direct relationship.

That relationship produced another compounding advantage—data. If you sold through retailers, you often didn’t know who bought your machines, what configuration they chose, when they upgraded, or what support issues they ran into. Dell knew. That information fed better marketing, better service, and better forecasting. It made the system smarter every quarter.

By 2001, Dell reached what many people had assumed would never happen: it became the world’s largest PC vendor, surpassing Compaq. The company that started with “three guys with screwdrivers” now controlled roughly 13% of the global PC market. Michael Dell’s net worth climbed past $16 billion, making him one of the richest people in America before 40.

The competitive landscape during this era reads like a time capsule. Compaq struggled under the weight of retail complexity and would eventually be acquired by HP. Gateway tried to mirror Dell’s approach but added costly retail stores and watched share slip away. IBM, the company that created the PC category, eventually decided the economics weren’t worth it and exited the business—selling its PC division to Lenovo in 2004.

And Dell wasn’t just taking the PC market. The dot-com boom created a massive surge in demand for servers, and Dell applied the same playbook—commodity components, build-to-order, direct sales—to enterprise hardware. By 2001, Dell held the top spot in the U.S. server market as well.

Wall Street, of course, loved the story. Dell’s stock performance became the kind of chart people brought to conferences to make a point. A $1,000 investment at the 1988 IPO would have been worth more than $400,000 by 2000. Dell was generating over $30 billion in annual revenue, and it often posted better margins than competitors despite lower prices—because the real product wasn’t just the PC. It was the model.

By the turn of the millennium, Dell looked untouchable: huge PC share, server momentum, and expansion into adjacent categories like printers, storage, and services. Business schools dissected the direct model. Analysts called the execution flawless.

And that’s what made what came next so brutal.

Because the industry was about to shift again. Only this time, the ground wouldn’t move in Dell’s favor—and the model that had turned Dell into the king of PCs would start to look less like a moat and more like a constraint.

IV. The Decline: Losing the Crown (2000s-2012)

On March 4, 2004, the mood at Dell’s Round Rock headquarters was off. Michael Dell—founder, face of the company, and architect of the direct model—walked into the boardroom and did something almost no one expected: he said he was stepping down as CEO.

He wasn’t leaving the building. At 39, he would stay on as chairman. But day-to-day control would move to Kevin Rollins, his longtime COO. The official line was that it was time for new leadership. The subtext was more complicated. Dell was still on top of the PC world, but Michael could feel the business tightening—PC growth slowing, margins thinning, competitors learning fast. He was trying to get ahead of a storm.

Instead, the storm hit, and Dell didn’t have its hands on the wheel.

In the years that followed, Dell ran into a problem that the direct model couldn’t solve: the center of gravity in computing was moving away from the beige box. The biggest shock came from Cupertino. In 2007, Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone and reframed what “a computer” even was. It wasn’t a tower under a desk or a laptop in a bag. It was a thing in your pocket—always on, always connected, wrapped in software and services that made the hardware feel magical.

Dell responded, but mostly in the way a great hardware company responds when the game turns into something else: it shipped devices. The Aero. The Venue Pro. The Streak, a five-inch in-between gadget that arrived before the world was ready for the form factor—and didn’t give anyone a reason to get ready.

Meanwhile, the real shift wasn’t just the phone. It was the platform. Apple wasn’t selling a handset; it was building an ecosystem. Dell was still thinking in configurations and supply chains.

Then came tablets. Apple launched the iPad in 2010 and, almost overnight, gave consumers a new default device for everyday computing. Dell’s advantage—custom-built machines shipped quickly—mattered less when customers wanted something thin, instant, and designed as a complete experience. Waiting for delivery was no longer a feature. It was friction.

As the market changed, Dell’s competitive position cracked. In 2006, Dell lost its spot as the world’s number one PC maker to HP. Soon after, Lenovo passed Dell in global market share as well. Rivals had improved their supply chains and learned from Dell’s playbook—but they also had something Dell didn’t: a strong retail presence for consumers and a broader portfolio to cushion the blows.

Wall Street noticed. Dell’s stock, which had traded above $40 in 2004, sank below $10 by 2008. The longer-term picture was even harsher: $100 invested in Dell stock in 2008 would be worth about $68 by 2013, while the same money in a technology index would be roughly $138. Growth stalled. Margins compressed. Dell looked like a company built for the last era.

So Michael came back.

In January 2007, he returned as CEO, taking the job he’d handed away less than three years earlier. Internally, it was framed as a reset—a founder stepping in to lead a turnaround. But the challenge wasn’t about execution. Dell could execute. The problem was that the definition of “winning” had changed.

The attempted reinvention became known as “Dell 2.0,” and it came with a bit of identity whiplash. Dell experimented with retail and pushed harder on design, trying to compete in a world where Apple had set the standard. But Dell wasn’t built for that kind of fight. Its retail stores felt like pale echoes of Apple’s, and premium products like the Adamo laptop didn’t turn into a meaningful franchise. Dell was trying to out-Apple Apple, while the thing Dell had been best at—operational excellence in a commoditized market—was becoming less valuable to consumers.

Where Dell did find a path forward was in the enterprise.

Michael recognized that while consumer PCs were getting squeezed, businesses still needed servers, storage, networking, and IT services. Dell started buying pieces that could turn it into a full-stack enterprise provider: EqualLogic in 2007, Perot Systems in 2009, and then Compellent and Boomi in 2010. It was a real strategy: trade the volatility of consumer demand for long-term business relationships and recurring services.

But there was a catch. Doing this transformation in public was like trying to rebuild an airplane mid-flight while a crowd graded every bolt you tightened. Every quarter came with scrutiny, impatience, and second-guessing. Activists and analysts didn’t want a multi-year pivot; they wanted immediate proof.

By 2012, the pressure wasn’t just external—it was structural. PC sales were declining globally for the first time. Smartphones and tablets were cannibalizing laptops. Cloud computing was starting to change how companies thought about servers and data centers. Dell’s consumer business was struggling, morale was slipping, and the company’s narrative had shifted from “category leader” to “yesterday’s winner.”

The headlines followed. Dell went from Wall Street darling to Wall Street punching bag. Analysts floated breakups. Others suggested a sale. The conversation wasn’t about how Dell would grow—it was about whether Dell could stay whole.

And that’s when the idea that would define the next decade started to harden.

Late in 2012, staring at a stock price still under $10, Michael Dell made a founder’s calculation. If the public markets wouldn’t give him the time to remake the company, he’d have to take that time for himself. The same person who took Dell public at 23 was now, at 47, preparing to take it private—setting up the largest technology leveraged buyout in history, and a battle that would decide not just the company’s future, but his legacy.

V. Going Private: The Battle with Carl Icahn (2013)

The leak hit on a Monday night in January 2013. CNBC’s David Faber reported that Michael Dell was in talks to take Dell private, and by Tuesday morning the story had detonated across Wall Street. The rumored price—somewhere in the $13 to $14 range—implied a roughly $24 billion take-private. It would be the biggest leveraged buyout since the financial crisis. More importantly, it signaled something personal: the founder was ready to bet on himself again.

On February 5, 2013, the deal became official. Michael Dell, partnering with Silver Lake, offered $13.65 per share to buy out the public shareholders. The structure made the intent unmistakable. Michael would roll his existing stake and put in additional capital to end up with roughly 75% ownership—about $4.2 billion of his own money at risk. Silver Lake would invest $1.4 billion for the remaining 25%. And in a twist that told you how strategic this was, Microsoft agreed to provide a $2 billion loan—effectively betting that a private Dell, freed from quarterly optics, could become a stronger enterprise partner.

On paper, the offer looked attractive: about a 25% premium to the unaffected stock price. In the real world, it landed like a provocation. Dell stock had been above $17 just six months earlier. And shareholders immediately asked the obvious question: if the company was truly a melting ice cube, why was the founder so eager to own more of it?

That’s where Carl Icahn came in.

Icahn had built a career on showing up when he thought boards were selling shareholders short. He quietly bought into Dell—eventually reaching 8.9%—and then went loud. In March 2013, he attacked the deal as “the ultimate insider trade,” and labeled Michael Dell a “corporate dictator” trying to steal the company.

His core argument was simple: Dell was worth more than this. The enterprise pivot was real, the services business was growing, and the company still threw off billions in cash flow. He pointed to the balance sheet and argued shareholders were being asked to hand over upside right as the turnaround might finally start to show up.

Because this was a take-private, the board formed a special committee to evaluate alternatives. Advised by Evercore, it ran a 45-day “go-shop” period to solicit competing bids. And for a moment, it looked like the process might actually produce a higher price. Blackstone surfaced with a potential offer of $14.25 per share. Icahn proposed something different: a leveraged recapitalization that would keep Dell public while paying shareholders a $9 special dividend.

By early May, the opposition became organized. On May 9, Southeastern Asset Management and Icahn formally teamed up to push alternatives. Southeastern owned about 8.4% of Dell. Icahn disclosed owning 4.52% by May 10, with that stake later rising to 8.9%. Between them, they had enough votes—and enough publicity power—to turn the deal into a street fight.

And Icahn didn’t treat it like a polite disagreement. He turned it into a referendum on governance. In letter after letter, he framed Michael Dell as an insider gaming the system. When the board postponed an early vote, Icahn compared the process to an election in a dictatorship: when the ruling party loses, it just finds a reason to try again.

The decisive showdown was supposed to happen on July 18, 2013. But as the meeting approached, it was clear Michael Dell didn’t have the votes. Approval required a majority of shares not held by Michael Dell or Silver Lake. With major holders like Southeastern and Icahn opposed—and with many retail investors not voting, which under the original terms effectively counted as “no”—the math wasn’t there.

So the board postponed the vote. Then postponed it again. And again. The optics were awful, and the commentary was brutal. Barron’s Andrew Bary famously wrote that, “In an action worthy of Vladimir Putin,” Dell postponed a vote when it became apparent shareholder support was insufficient.

But postponing wasn’t the only move. Dell and Silver Lake sweetened the offer to $13.75 per share plus a $0.13 special dividend, bringing the total to $13.88. And they changed the voting mechanics so that only votes actually cast would count—non-votes would no longer function as “no” votes. They also moved the record date, giving more influence to investors who had bought shares after the deal was announced.

Icahn, predictably, went nuclear: “What’s the difference between Dell and a dictatorship? Most functioning dictatorships only need to postpone the vote once to win.” The line made headlines. It didn’t stop the deal from gaining momentum.

Icahn’s alternative, though, wasn’t just bluster. It had real financial engineering behind it. He lined up $5.2 billion in committed debt financing, including $1.6 billion from Jefferies Finance. Combined with $7.5 billion of Dell’s own cash and $2.9 billion from selling receivables, it would fund $15.6 billion for his plan. Shareholders could tender up to 72% of their shares at $14 each and keep equity in the remaining company. For investors who believed in the turnaround, it was tempting: take cash now, keep a toe in the upside later.

Michael Dell’s counter was brutally straightforward: certainty. His offer was fully financed, backed by Microsoft, and gave shareholders a clean exit. Icahn’s plan, however creative, asked investors to keep riding a PC-heavy company through a transformation that was still more promise than proof.

Even the legal system wasn’t inclined to intervene on Icahn’s terms. Delaware Chancellor Leo Strine Jr. said Icahn had offered no justification for expedited proceedings and no evidence that the special committee wasn’t acting independently or in good faith.

On September 12, 2013, the saga ended. With the revised voting rules and the slightly higher price, shareholders approved the deal.

Icahn still claimed a kind of victory—because the price did rise, and shareholders ended up with more than the original terms. Michael Dell, meanwhile, made it clear he saw Icahn as a tourist, not a partner. He later said Icahn “didn’t own a share of the stock until after the deal was announced” and had no long-term intentions for the company or the people inside it.

The final package valued Dell at $24.9 billion, the largest technology LBO in history. For Michael Dell, it was a massive personal risk and a shot at rebuilding the company away from public-market impatience. For Silver Lake, it was a chance to run a founder-led transformation at enormous scale.

And now they finally had what they came for: time, control, and a capital structure built for reinvention. The question was what they’d do with it.

VI. The Private Years: Transformation & EMC (2013-2016)

The transformation started almost as soon as the company went dark.

In October 2013, weeks after the buyout closed, Michael Dell pulled his senior team into Round Rock for what he called a “blank sheet” session. The point was to reset the operating system. “Forget everything you know about quarterly earnings,” he told them. “We’re now playing a completely different game.”

Sitting with them was Egon Durban, the Silver Lake partner newly added to Dell’s board. Durban wasn’t there to run a standard private-equity script of trimming costs and calling it a turnaround. He’d helped engineer the Skype turnaround and its eventual $8.5 billion sale to Microsoft. His presence sent a message: Dell and Silver Lake weren’t buying time to defend the old business. They were buying time to rebuild the company.

The strategy that came out of those early sessions was blunt. Dell would stop pretending it could be a consumer darling in a post-iPhone world. The new goal was to become the core technology partner for big organizations modernizing their IT for the cloud era. That meant servers and storage, yes—but also security, orchestration, analytics, and the software glue that made modern data centers actually work.

The dealmaking that followed was fast and targeted. In 2014 alone, Dell picked up StatSoft for advanced analytics, Cloudify for cloud orchestration, and a string of smaller assets that didn’t dominate headlines but filled real holes in the portfolio. They weren’t buying “growth.” They were assembling capabilities—piece by piece—so Dell could show up to enterprise customers as more than a box seller.

But even that flurry of acquisitions was just the warm-up.

Behind the scenes, through 2014 and into early 2015, Michael Dell and Durban were exploring something so large it barely sounded possible for a newly private company loaded with buyout debt: acquiring EMC.

EMC was the heavyweight of enterprise storage—an industry pillar with a market cap north of $50 billion. It also owned about 80% of VMware, the virtualization company that many people believed was more valuable than EMC itself. EMC was led by Joe Tucci, a CEO with a near-mythic reputation in enterprise tech. And it was under pressure, with activist investor Elliott Management pushing for major changes, including the possibility of breaking the company apart.

Michael Dell and Tucci first talked seriously in the spring of 2015, in the kind of setting where big corporate ideas often begin: a conference where both were speaking, a quiet moment between sessions. The question on the table was simple, almost casual: what if they combined forces?

What followed was anything but casual—months of negotiations and structuring work that turned into one of the most complex transactions tech had ever seen. EMC wasn’t a single business; it was a federation that included RSA Security, Pivotal, and Virtustream. VMware was publicly traded, with its own shareholder base and governance realities. Any deal had to deliver clear value to EMC shareholders without blowing up the very structure that made EMC work.

On October 12, 2015, the industry got the answer. Dell—alongside Silver Lake and MSD Partners—announced an agreement to buy EMC for $67 billion, the largest technology acquisition in history. EMC shareholders would receive $24.05 per share in cash, plus VMware tracking stock valued at roughly $9 per EMC share. Big number, even bigger mechanics.

The financing was just as dramatic. Dell was taking on close to $50 billion of additional debt for the purchase, on top of the roughly $11 billion it already had. This wasn’t “bet the company.” It was bet the company, the capital structure, and the founder’s legacy—on the idea that the combined business would have the scale and breadth to matter in the next era of enterprise computing.

The strategic logic was straightforward. Together, Dell and EMC would create a roughly $74 billion enterprise technology leader spanning hybrid cloud infrastructure, storage, servers, and a broader set of capabilities from security to data analytics. EMC brought credibility with the largest enterprise customers, a dominant storage position, and—most importantly—control of VMware, the software layer sitting at the center of modern data centers.

Still, nothing about closing this deal was guaranteed. Regulators around the world had to sign off, including China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), which had a reputation for turning major tech approvals into endurance tests. EMC shareholders had to approve a structure that included tracking stock, something many investors disliked on principle. And operationally, Dell would need to integrate two enormous organizations with different cultures and go-to-market motions—all while carrying unprecedented leverage.

Then came an early signal that the sheer size and complexity of the deal might actually protect it: the go-shop period produced no superior offer. No rival bidder stepped in. In a strange way, that quiet was validating. There were very few buyers on earth who could even attempt something like this.

Through 2016, approvals started to stack up. The European Union cleared the acquisition on February 29, 2016. But the real suspense was China. If MOFCOM delayed too long—or refused—this entire transaction could unravel.

On July 19, 2016, EMC shareholders voted. The results weren’t close: 98% of voting shares supported the deal, representing 74% of outstanding shares. Tucci put his stamp on it: “This combination creates an enterprise solutions powerhouse.”

And on September 7, 2016, it finally closed. Dell Technologies was born.

What emerged wasn’t a single monolithic company, but something closer to a holding-company ecosystem—Dell’s version of EMC’s federation. Dell Technologies now included Dell (PCs and servers), Dell EMC (storage), VMware (virtualization), Pivotal (cloud software), RSA (security), SecureWorks (managed security), and Virtustream (cloud services). The idea was coordinated autonomy: keep each business sharp in its category, but create leverage through shared customers, shared distribution, and cross-selling.

Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase, captured what Dell hoped to become for the world’s largest enterprises: a long-term infrastructure partner. He noted JPMorgan’s roughly $9 billion annual technology spend and said the bank chose partners carefully. He added that he’d known Michael Dell for 30 years and praised his character and leadership, saying he was “thrilled for Michael and the new company.”

In three private years, Dell had gone from a struggling PC maker under public-market pressure to the owner of one of the most important enterprise portfolios in tech. The strategy had changed. The scale had changed. The stakes had definitely changed.

Now came the unforgiving part: making a federation work, proving the logic of the biggest tech acquisition ever, and paying down a debt load that left little room for mistakes.

VII. Dell Technologies Era: Building the Federation (2016-2021)

The first reality check came in the balance sheet.

When the EMC deal closed, Dell Technologies was carrying roughly $55 billion of total debt—an amount that would make even hardened buyout veterans swallow hard. At the first all-hands for the newly combined company, Michael Dell didn’t try to sugarcoat it. Yes, the leverage was real. But, he argued, so was the payoff: Dell now had the broadest end-to-end enterprise portfolio in the industry.

The way Dell tried to make that portfolio work was unusual—especially for a merger this big. Instead of smashing EMC into Dell and hoping the cultures magically blended, Dell leaned into a “federation” model: keep the major businesses distinct, give them room to run, but tie them together commercially. VMware stayed publicly traded with its own CEO and board. RSA kept its security focus. Pivotal kept pushing cloud-native software. The point wasn’t to turn everything into one brand. It was to keep each unit sharp, while using Dell’s distribution muscle to sell the whole bundle.

Egon Durban’s fingerprints were all over this era. The Silver Lake partner brought a kind of operating discipline that’s easier to impose in private equity than in a typical public company. The message internally was consistent: performance would be measured, synergy would be tracked, and capital would have to earn its keep. This wasn’t “let’s buy our way into the future.” It was systematic value creation under a microscope.

And the commercial engine really was formidable. By 2017, Dell had more than 140,000 employees across 180 countries. Its salesforce could walk into a Fortune 500 account and credibly offer the full stack—from employee laptops at the edge, to servers and storage in the data center, to virtualization and security layers around it. A CIO didn’t need to stitch together five vendors. Dell wanted to be the vendor.

But the federation only mattered if the math worked. The debt had to come down.

Dell attacked it with near-single-minded focus. In its first post-close update, the company highlighted $5.8 billion of debt paydown already completed after the EMC merger. The business threw off billions in annual cash flow, and a huge portion of that went straight to deleveraging. Over time, the number added up: by 2018, Dell said it had paid down close to $20 billion from peak levels.

Then the thing that was supposed to simplify the deal started causing its own headaches: VMware tracking stock, DVMT.

The tracking stock was designed to give EMC shareholders a way to participate in VMware’s upside without forcing a full VMware sale. In practice, it became a constant irritant. DVMT routinely traded at a meaningful discount to VMware’s actual stock, and holders hated it. The structure was complicated, it created governance questions, and it left investors feeling like they were holding a shadow of the real asset.

And that opened the door for a familiar voice.

Carl Icahn, who’d lost the 2013 war over taking Dell private, showed up again—this time building a position in DVMT and pushing for better terms. The rhetoric came right back, too: Icahn argued that Dell was using financial engineering to disadvantage DVMT holders.

Michael Dell’s response was bold and very on-brand: turn the problem into a transaction.

In July 2018, Dell announced it would eliminate the tracking stock by exchanging it for a new class of Dell common stock—effectively taking Dell public again, but without a traditional IPO. Under the proposal, DVMT holders could receive 1.3665 shares of Dell Class C stock per share, or elect $109 in cash per share, subject to an overall cash cap of $9 billion. Dell emphasized that the cash option represented a sizable premium to DVMT’s pre-announcement trading price.

The move worked because the financing was engineered into the structure. VMware’s board approved an $11 billion cash dividend to all VMware shareholders, with Dell’s portion coming to roughly $9 billion—cash that could help fund the transaction.

Icahn fought it at first, as expected, arguing the offer still didn’t fully capture value. But Dell approached this round differently than 2013: a more formal process, a more defensible premium, and a clearer set of choices for investors.

Shareholders approved the deal in December 2018. The cash election was heavily utilized—elections were made for 181,897,352 shares, or 91.2% of the outstanding Class V shares—signaling just how much holders wanted out of the tracking-stock complexity. Dell ultimately paid $14 billion in cash and issued 149,387,617 shares of Class C common stock to complete the exchange. DVMT stopped trading before the market opened on Dec. 28, 2018, and Dell’s Class C shares began trading under the ticker DELL on Dec. 26, 2018.

After five years, Dell was public again—but on its own terms. The stock opened around $46 a share, putting a roughly $16 billion market capitalization on the public float, even as the real story remained the much larger enterprise value once you included the debt.

Operationally, Dell could point to results while it was rewriting the cap table. By 2019, the company was generating more than $90 billion in annual revenue. It held the top global position in servers and was pushing for share gains across storage and converged infrastructure.

The federation pitch also held up in the field. Dell could sell a cohesive modernization project: Dell servers, EMC storage, VMware virtualization, RSA security, and services to stitch it together. Rivals had gaps. HP had split itself in two. IBM was still trying to find its footing in a changing market. Cisco had strength in networking, but not the full compute-and-storage stack. Dell’s breadth was the differentiator it kept coming back to.

By 2020, Dell had reduced debt dramatically—down from a peak near $60 billion to under $35 billion—while still funding the business. And as the balance sheet improved, ratings followed: Dell achieved investment grade ratings from Moody’s and S&P, a milestone that lowered borrowing costs and widened its financing options.

The reputation shift inside the enterprise was just as important. Dell—the company many people still associated with low-cost PCs—was now showing up in massive infrastructure decisions. The pitch wasn’t cheap hardware. It was: we can be your long-term platform partner.

But success created a new kind of pressure. By 2021, VMware—the crown jewel from EMC—was worth more than Dell Technologies’ own market value. Owning 81% of a public company while being public yourself created governance friction, valuation discounts, and endless investor debates about structure. Dell’s board started weighing the next move: a VMware spin-off to simplify the story and unlock value.

The federation had been built to win the transformation. Now Dell was considering taking it apart—at least at the top—to make the next chapter possible.

VIII. The VMware Spin & Modern Dell (2021-Present)

The announcement landed on April 14, 2021, and it caught even longtime Dell watchers off guard. After spending years telling the world that EMC—and by extension VMware—was the foundation of Dell’s enterprise future, Dell Technologies said it would spin off its 81% stake in VMware to shareholders.

On the surface, it looked like a strategic U-turn. Why give up the crown jewel?

Michael Dell’s explanation was simple and very Dell: simplify. Sometimes the fastest way to unlock value isn’t to add another layer of strategy—it’s to remove a layer of structure.

The mechanics were intricate, but the end state was clean. Dell completed the spin-off of its 81% equity ownership of VMware through a special dividend of 30,678,605 shares of VMware Class A common stock and 307,221,836 shares of VMware Class B common stock distributed to Dell’s stockholders of record as of 5:00 p.m. ET on October 29, 2021. In connection with the distribution, each share of VMware Class B common stock converted into one share of VMware Class A common stock. Dell Technologies stockholders received 0.440626 of a share of VMware Class A common stock for each share of Dell Technologies common stock held as of 5:00 p.m. ET on October 29, 2021.

But the real lever in the deal wasn’t the share math. It was cash.

VMware paid a special cash dividend of $11.5 billion to its shareholders. Dell’s portion was $9.3 billion, and Dell used it to pay down debt. This was the key: Dell could separate from VMware and, at the same time, use the transaction to accelerate its deleveraging and strengthen its credit profile.

The rationale had been building for years. First, the ownership structure had turned into a governance headache. Being the 81% owner of a public company meant constant conflict questions and constant minority-shareholder scrutiny. Second, VMware’s valuation carried baggage from the relationship—investors worried Dell could extract value from VMware. And third, Dell’s own valuation took a hit from the complexity. The market struggled to price a company that was both an operating business and the controlling owner of another major public company.

After the spin, Dell hit a milestone that had once seemed impossible when the EMC deal closed: investment grade. Dell Technologies received investment grade corporate family ratings from all three major credit rating agencies, lowering borrowing costs and widening its financing options. The company that had taken on nearly $60 billion of debt in the EMC era now had the balance sheet credibility of a mature, stable enterprise infrastructure provider.

Dell and VMware didn’t walk away from each other entirely. They kept a commercial agreement designed to preserve the most valuable parts of the relationship—co-development of solutions and alignment on sales and marketing. Michael Dell remained chair and CEO of Dell Technologies, and also chair of VMware’s board, holding influence while letting the two companies operate with more independence.

The market’s reaction was positive but not euphoric. Dell’s stock moved up from its pre-announcement range as investors recalibrated, then settled as the debate took shape. One camp argued Dell had given up its most valuable asset. The other argued the company had finally done what it needed to do: remove the structural discount and let Dell be valued like a real operating enterprise.

Then the timing turned out to be exceptional.

Not long after Dell simplified its structure and improved its balance sheet, the AI wave hit enterprise computing like a freight train. And Dell—still one of the world’s most embedded infrastructure suppliers—was positioned to benefit.

In May 2024, Dell’s partnership with Nvidia snapped the company’s story into a new frame. On stage at Dell Technologies World, Nvidia founder and CEO Jensen Huang leaned into the metaphor that quickly became the headline: AI “factories.” Dell would help enterprises build the infrastructure to train and deploy AI models, end to end. “We now have the ability to manufacture intelligence,” Huang said during his on-stage conversation with Michael Dell.

The pitch was straightforward: enterprises were staring at a complicated build—GPUs, servers, storage, cooling, power, networking, software orchestration, deployment tooling—and they didn’t want to duct-tape it together themselves. Dell wanted to be the turnkey provider, taking decades of enterprise relationships and operational execution and turning it into a packaged path to AI adoption. The Dell AI Factory with NVIDIA offered a full stack of AI solutions from the data center to the edge, aimed at letting organizations deploy AI at scale.

Investors took notice. Dell’s shares surged after results showed demand lifting for infrastructure tied to AI workloads. That move had a very visible side effect: Michael Dell’s net worth crossed $100 billion, pushed higher as Dell’s stock jumped to a record high. In March 2024, Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index put him into the ultra-exclusive $100 billion club.

And the VMware decision had another, unexpected tailwind. When Broadcom acquired VMware for $61 billion in 2023, the separation set Dell up to benefit from value that continued to compound as AI demand accelerated. Michael Dell also received Broadcom shares after the VMware deal, and those appreciated further as the market chased the AI buildout.

By this point, Dell Technologies barely resembled the company people associated with the 1990s—or even the hardware-and-services transformer of the 2010s. “We’re on a mission to bring AI to millions of customers around the world,” Michael Dell said. “Our job is to make AI more accessible. With the Dell AI Factory with NVIDIA, enterprises can manage the entire AI lifecycle across use cases, from training to deployment, at any scale.”

Dell kept pushing forward. In 2025, it announced next-generation AI solutions with Nvidia’s Blackwell architecture. It also highlighted partnerships that pointed beyond boxes—like the work with ServiceNow around “AI factories,” aimed at delivering more complete, enterprise-ready solutions.

Looking at Dell from the other side of the VMware spin, the arc is almost hard to believe. A PC pioneer loses the crown. A founder takes the company private under activist fire. Then he leverages the private years to swing at the biggest tech acquisition ever—loads the balance sheet, builds a federation, pays down the debt, simplifies the structure again, and walks into the AI infrastructure boom with enterprise distribution already in place.

And at the center of it all is still Michael Dell—now 60—running the company he started as a teenager, but with a very different set of tools than the ones he used in that dorm room: scale, capital structure, and the hard-earned ability to keep reinventing before the world forces it.

IX. Playbook: The Financial Engineering Masterclass

The Dell story isn’t just a comeback arc. It’s a case study in how capital structure can be as decisive as product strategy. Over and over, Dell used financial design—sometimes elegantly, sometimes controversially—to buy time, create options, and unlock value that the market couldn’t or wouldn’t price in.

The throughline is simple: Dell didn’t just try to run a better business. It tried to build a better financial machine around that business.

The Direct Model as Financial Innovation

The original direct model wasn’t only a clever way to sell PCs. It was a working-capital advantage disguised as a sales strategy.

While rivals like Compaq and HP carried months of inventory, Dell squeezed the cycle so tightly that it often got paid by customers before it paid suppliers. In a world where component prices dropped fast, this wasn’t a nice-to-have. It meant Dell avoided owning melting inventory and, instead, effectively financed itself with supplier terms.

At its peak, Dell’s cash conversion cycle hit negative 36 days—meaning customer cash sat on Dell’s books for more than a month before supplier bills came due. On a business doing around $30 billion in annual revenue, that translated into roughly $3 billion of free float at any given time: an interest-free loan from the supply chain that could be poured into growth, pricing, acquisitions, or simply surviving downturns better than everyone else.

Going Private: The Transformation Catalyst

The 2013 take-private wasn’t just leverage. It was a deliberate removal of constraints.

Public markets want clean narratives and quarter-to-quarter proof. Dell needed the opposite: room to spend, to shift mix, to be temporarily “messy” while it moved from consumer PCs to enterprise infrastructure. Paying a premium to go private bought something that never appears in the merger model: permission to think in years instead of quarters.

The structure reinforced credibility. Michael Dell rolled his equity and added capital, keeping massive skin in the game. Silver Lake brought capital and operating intensity, with Egon Durban on the board. And Microsoft’s $2 billion loan wasn’t a favor—it was a strategic bet that a stronger Dell could become an even more important enterprise partner.

The EMC Acquisition: Debt as a Weapon

Then came the swing that made the whole saga feel unreal: using roughly $50 billion of new debt to buy EMC.

In 2016, it looked reckless on the surface. PCs were in decline. Cloud providers were building their own infrastructure. And Dell was already carrying buyout leverage. But Dell and Silver Lake were making a scale argument: in a fragmented enterprise world, breadth would matter, and owning the center of the data center—servers, storage, virtualization, security—would create an advantage that was hard to dislodge.

Debt wasn’t treated as a burden. It was treated as the cost of assembling an enterprise portfolio that could justify the risk.

And critically, Dell didn’t try to blend everything into one giant organism. The federation model—keeping key businesses distinct—was part strategy, part value preservation. VMware stayed public and independently valued, giving Dell both transparency and flexibility.

The Tracking Stock Innovation

The most “Dell” piece of the whole EMC deal might have been the VMware tracking stock, DVMT.

Dell needed to give EMC shareholders something liquid, but full cash would have been too expensive and a traditional stock deal would have pushed Dell back into public markets before it was ready. DVMT became the workaround: a security that gave holders economic exposure to VMware while Dell itself stayed private.

It wasn’t popular. It was complicated, it traded at a discount, and it created years of governance friction. But it did what it was built to do: it made the EMC deal financeable, created a bridge back to public markets, and kept Dell in control of the timeline.

Managing Complexity Through Financial Structure

Dell’s broader move wasn’t just “more deals.” It was segmentation by design.

Different businesses inside the federation had different growth rates, margin profiles, and capital needs. Keeping them distinct made it easier to allocate investment, measure performance, and decide what to keep, fix, or eventually unwind.

The debt plan followed the same logic. Dell focused heavily on paying down leverage, but it didn’t do it mindlessly. It refinanced when windows opened, extended maturities when it could, and used major transactions—like dividends tied to VMware—to accelerate deleveraging without starving the core business. Over time, the result was dramatic: the company moved from roughly $57 billion of debt to under $20 billion while still investing and executing.

Market Timing as a Core Competency

What’s easy to miss is how contrarian the sequencing was.

Going private in 2013, right as the industry narrative was turning against PCs and toward cloud. Buying EMC in 2016, when enterprise IT was seen as slow and unglamorous. Returning to public markets in 2018 through a structure designed to avoid a traditional IPO. Spinning VMware in 2021—then watching infrastructure become valuable again as AI demand surged.

Each move was criticized in real time. In hindsight, the rhythm looks deliberate: make the hard structural changes when expectations are low, then surface simplicity and optionality when markets are ready to reward it.

The Power of Patient Capital

Silver Lake’s role is also part of the playbook. This wasn’t a quick flip. The Dell transformation took time, and the partnership worked because incentives were aligned: founder-led control paired with private equity discipline.

By 2023, various estimates suggested Michael Dell and Silver Lake earned around $70 billion from the broader Dell investment. Not because they found a clever spreadsheet trick—but because they used structure to survive the messy middle long enough for the strategy to compound.

Creating Multiple Options for Value Realization

Dell repeatedly engineered optionality.

Tracking stock created a future path back to the public markets. Owning VMware created choices: dividends, partial monetization, or an eventual spin. The federation structure kept assets separable, so individual businesses could be sold, spun, or restructured without destabilizing the whole company.

That flexibility reduced risk. And it kept Dell from ever having just one “make-or-break” exit door.

The Dividend of Simplification

The final move in the playbook was recognizing when complexity had outlived its usefulness.

Once the transformation had taken hold and deleveraging was real, Dell started unwinding the structures that had enabled the journey. Spinning VMware eliminated persistent governance and valuation friction. Achieving investment grade reduced financing costs and made the story legible again. At a certain point, the best financial engineering wasn’t adding another layer—it was removing one.

Lessons for Future Financial Engineers

The Dell playbook offers a few durable lessons. Financial engineering works best when it serves strategy, not the other way around. Complexity can be a tool during transformation, but it eventually becomes a tax. Patience and aligned incentives matter more than winning an argument about valuation. Timing matters—being right too early can look identical to being wrong. And the strongest structures create options, not traps.

The market ultimately validated the approach. By 2023, Dell’s enterprise value exceeded $150 billion. Michael Dell’s net worth surpassed $100 billion. Silver Lake’s returns ranked among the best in modern private equity. Even Carl Icahn, despite losing the big battles, made money along the way.

Dell didn’t just survive the post-PC era. It turned reinvention into a repeatable method—and in the process, wrote one of the most consequential financial-engineering playbooks in tech history.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Competitive Analysis

Bull Case: The AI Infrastructure Powerhouse

The bull case for Dell starts with a pretty basic reality: if companies are serious about AI, they need infrastructure. And most enterprises don’t want to become full-time data center architects just to get models into production. Dell lives in that gap—where deep customer relationships, battle-tested infrastructure, and an ecosystem of partners can turn “we want AI” into something that actually runs.

Start with position and access. Dell is the world’s number three AI server vendor and has been growing share at a double-digit pace. And Dell’s installed base matters: it sells to 98% of the Fortune 500. In enterprise buying, being already inside the building is an advantage you can’t fake. When a CIO decides to stand up GPU clusters, there are only a few viable paths: attempt a build-it-yourself integration job, rent it from a cloud provider, or buy from someone who ships, supports, and stands behind the whole stack. Dell is one of the short-list vendors in that third category.

The Nvidia partnership is the accelerant. Yes, anyone can buy Nvidia GPUs in theory. In practice, supply is the constraint, and engineering support is the differentiator. Dell gets priority allocation and co-development help, and it can deliver systems tuned for Nvidia’s newest platforms quickly. When Nvidia introduced its Blackwell architecture, Dell was positioned to ship configured systems immediately.

Economically, AI infrastructure is a very different product than a “normal” server refresh. AI servers carry much higher average selling prices and typically better margins, and the deployments pull more services along with them because they’re harder to design, stand up, and manage. The replacement cycle can also compress, because AI hardware and software stacks evolve fast and performance gaps matter.

Dell’s enterprise DNA is also a real edge. Competitors like Super Micro Computer can win deals on speed and price, but big enterprises tend to value reliability: global support, predictable supply chain execution, and systems that won’t surprise you in production. If you’re a bank training models for risk or a hospital running imaging workflows, downtime and misconfiguration aren’t inconveniences—they’re unacceptable.

The storage angle often gets missed in the AI hype, but it’s fundamental. Training data, checkpoints, logs, inference output—AI is a storage-and-data-movement problem as much as a compute problem. Dell’s EMC-built storage portfolio gives it a credible “whole system” story, and the company says a large share of its all-flash array customers also buy servers from Dell. That kind of portfolio pull-through is exactly what Dell bought EMC for.

And then there’s services. Dell has about 60,000 services professionals who can design, deploy, and manage these environments. That’s revenue, sure—but it’s also stickiness. When Dell helps you build the thing, it’s much harder to rip Dell out later.

Bear Case: The Commodity Trap Returns

The bear case starts with the uncomfortable version of the truth: Dell isn’t inventing the core breakthroughs. Nvidia makes the GPUs. Intel and AMD make the CPUs. Samsung and Micron make the memory. Dell’s value is integration, procurement, manufacturing, and support—important, but not impossible to replicate.

The biggest strategic threat is the cloud. AWS, Microsoft, and Google can offer AI infrastructure as a service, and for many enterprises, renting capacity is simpler than buying, housing, powering, and staffing an on-prem cluster. If AI workloads standardize over time, the hyperscalers’ scale economics and developer gravity become hard for anyone selling boxes to fight.

And if that sounds familiar, it should. Dell dominated PCs when buying and managing PCs was complex. As the category standardized and value shifted elsewhere, the advantage shrank. If AI infrastructure follows the same arc—high complexity early, then commoditization—Dell’s differentiation could compress right when expectations are peaking.

Competition is also coming from every direction at once. Super Micro is taking share in AI servers by moving fast and pricing aggressively. HPE has comparable enterprise relationships and is pushing hard into AI. Lenovo has global scale and manufacturing reach. Newer players like CoreWeave are offering “GPU-as-a-service” without a hardware purchase at all.

Debt is a subtler risk, but it’s still there. Dell’s leverage is far healthier than in the EMC aftermath, but the company still carries around $20 billion in net debt. In a higher-rate world, that interest load matters. If AI spending slows or price competition squeezes margins, the financial cushion shrinks faster than most people expect.

There’s also a structural innovation gap. Dell spends roughly 3% of revenue on R&D, far below the cloud giants and semiconductor leaders. That doesn’t mean Dell can’t win—it means Dell is less likely to own proprietary technology that forces pricing power. In an ecosystem where value is pooling around Nvidia on one side and cloud platforms on the other, the integrator role can be profitable, but it can also be vulnerable.

Finally, valuation can become its own risk. Dell’s multiple has been supported by AI expectations. If those expectations normalize—because growth slows, competition intensifies, or margins disappoint—the stock can re-rate quickly.

Competitive Landscape: The Battle for AI Infrastructure

AI infrastructure is a knife fight happening in multiple arenas at once. Different competitors are strong in different parts of the stack, and enterprises increasingly buy “solutions,” not individual components.

HPE (Hewlett Packard Enterprise) is Dell’s closest mirror. Like Dell, it sells servers, storage, and services into the enterprise. Where HPE has taken a different tack is the push toward as-a-service with GreenLake, offering cloud-like consumption models on-premises. If customer preference shifts decisively toward consumption-based buying, HPE’s positioning could resonate.

Lenovo brings scale and manufacturing efficiency, plus enterprise credibility from its IBM server assets. It also has strength in Asia that Dell doesn’t match. But geopolitical constraints can limit where Lenovo can win, especially with sensitive customers.

Super Micro Computer is the nimble disruptor. It’s fast, customizable, and price-competitive, which matters in a market where customers are racing to get GPUs into racks. But it doesn’t have Dell’s global support footprint or long-standing enterprise relationships, and corporate governance and accounting concerns have added uncertainty.

Pure Storage and NetApp are key storage competitors. They sell modern storage platforms that can be attractive for AI data pipelines. What they lack, relative to Dell, is the ability to walk in with an integrated server-plus-storage story under one umbrella.

The Cloud Giants (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) are both rivals and customers. They compete by making hardware ownership optional. At the same time, they buy huge volumes of infrastructure for their own data centers. Dell has to thread a needle: serve the hyperscalers without handing them a playbook to replace Dell everywhere else.

The ODMs (Original Design Manufacturers) like Quanta and Wistron are the longer-term pressure. They already build a lot of what the cloud runs on, and they’ve been creeping toward direct enterprise sales with lower-cost offerings—typically with far less service and support.

The Crucial Differentiators

In a market like this, Dell’s case rests on a handful of differentiators that actually matter in enterprise buying:

- Portfolio breadth: Dell and HPE can sell a full bundle, from endpoints to servers to storage to services

- Global support: Dell’s services footprint is a real moat in regulated, mission-critical environments

- Supply chain execution: scale and relationships can mean better availability when components are constrained

- Enterprise trust: long relationships create switching costs that don’t show up on a spec sheet

- Financial stability: investment grade and strong cash flow matter when customers are betting their infrastructure roadmaps

- Partner ecosystem: Nvidia, Intel, AMD, and Microsoft partnerships shape how fast Dell can ship validated solutions

The Verdict

This debate comes down to one question: does AI infrastructure stay complex long enough for Dell’s integration-and-services engine to matter, or does it slide toward commodity economics the way PCs did?

The historical pattern says infrastructure eventually commoditizes. The counterpoint is that AI’s pace of change—and the operational complexity of deploying it safely inside enterprises—may keep the “systems integrator” role valuable for longer than skeptics expect.

Dell doesn’t need to own the whole market. It needs to stay relevant, keep execution tight, and earn its share as the market expands—while preparing for the day the industry’s center of gravity shifts again.

For investors, owning Dell is a bet that enterprise AI adoption won’t be purely cloud-based, that hybrid and on-prem deployments will remain important, and that Dell’s execution, support, and distribution can translate the AI boom into durable cash flow. It’s not a risk-free bet. But Dell’s entire history is essentially one long argument that the company knows how to survive transitions—and occasionally, how to turn them into an advantage.

XI. Epilogue: Lessons & Legacy

Walk through Dell’s headquarters in Round Rock, Texas, and the company’s history isn’t subtle. It’s on the walls: a relic from the earliest machines assembled from parts, the memento from the 1988 IPO, reminders of the go-private fight, and the EMC deal that rewired the whole company. You don’t get a journey like this without leaving artifacts behind.

Michael Dell, now 60, is still at the center of it. In a recent interview, he put the whole arc in one sentence: “Technology is about enabling human potential. That’s been true since I started the company, and it’s still true today.” The products change. The market changes. The capital structure definitely changes. But the mission he’s pointing to has stayed remarkably consistent.

The reason the Dell story sticks isn’t because it’s neat. It’s because it’s messy, high-stakes, and rare: a founder builds a category-defining company, watches the world shift away from his advantage, and then uses an entirely different set of tools to remake the business anyway.

The Ultimate LBO Success Story

By any reasonable measure, the Dell LBO belongs in the history books. A $24.9 billion take-private became the launching pad for an enterprise that, in later years, was valued well north of where it started. Estimates have put the value created for Michael Dell and Silver Lake at around $70 billion by 2023—numbers that start to look less like “good private equity returns” and more like “once-in-a-generation outcomes.”

But the more interesting part isn’t the magnitude. It’s what the deal proved.

Dell showed that private equity could work in technology at enormous scale—if you treated it as a transformation engine, not a cost-cutting exercise. It also challenged the usual fear around leverage in fast-moving markets. Dell carried a debt load that looked dangerous in an industry famous for brutal cycles and rapid obsolescence. And yet, through cash flow, discipline, and a portfolio shift toward enterprise infrastructure, it made the leverage survivable—and eventually manageable.

This was not “LBO theory” playing out on a chalkboard. This was the theory surviving contact with reality.

What This Means for Tech PE and Take-Privates

Before Dell, big tech LBOs were viewed as almost self-evidently reckless. Too much change, too much disruption risk, too many ways to get blindsided. After Dell, the question shifted from “Can this be done?” to “What does it take to pull it off?”

A few requirements stand out.

First, operational competence matters as much as the financing. Silver Lake wasn’t just a check. It brought a tech-specific playbook, and Egon Durban’s involvement reflected that this was meant to be actively guided, not passively owned.

Second, real transformations take longer than the traditional private equity timeline. Dell didn’t just disappear for a couple of years and reappear “fixed.” It went private in 2013, closed EMC in 2016, engineered its way back to public markets in 2018, and kept simplifying into the VMware spin in 2021. That’s not a quick flip. That’s a decade-long rebuild.

Third, founder leadership wasn’t incidental—it was structural. Michael Dell’s credibility with customers, employees, and lenders mattered. His willingness to risk his own fortune wasn’t symbolism; it aligned incentives and made the bet legible to everyone else involved.

The Dell precedent has helped legitimize founder-led take-privates as a serious strategic move, not just a governance stunt. But it also highlights how punishing these deals can be: the activist war, the governance fights, the complexity, the risk of getting timing wrong. Financial engineering can create a path. It can’t create an outcome by itself.

The Power of Long-Term Thinking

Dell’s most durable advantage in the 2010s wasn’t a product feature. It was time horizon.

Public markets demanded clean, immediate proof. Activists demanded near-term value. Dell’s leadership built around multi-year decisions that looked uncomfortable up close. Buying EMC when “hardware is dead” was the conventional wisdom. Keeping VMware separate instead of integrating everything into one blob. Spinning VMware later to simplify the story and accelerate deleveraging.

In each case, the choice wasn’t “obvious.” It was patient.

It also throws competitor decisions into sharper relief. HP split itself. IBM shed major hardware businesses over time. Those moves may have made sense in their moments, but they often reduced future flexibility. Dell generally chose the opposite instinct: assemble capabilities and keep options open, even when the market wasn’t rewarding the strategy yet.

Could This Playbook Work Again?

Could another company run the Dell playbook? In principle, yes. The ingredients are repeatable: a market in transition, a misunderstood asset, patient capital, and the willingness to endure short-term ugliness for long-term positioning.

But in practice, the exact Dell sequence is hard to recreate.

Debt markets shift. Regulators shift. The pace of technology shifts. And the biggest reason it worked for Dell is the one nobody can copy: it was contrarian at exactly the right moments. Going private when sentiment was collapsing. Buying a giant enterprise franchise when many investors wanted pure software stories. Holding the structure together long enough for the underlying strategy to show up in cash flow and relevance again.

The next great transformation probably won’t look like Dell. It will rhyme with it.

The Human Story

For all the talk of leverage, tracking stock, and capital structure, the story underneath is human: a founder who didn’t just win once, but refused to accept that the first act was the only act.

It’s also a story of organizations living through reinvention—employees adapting to constant change, customers choosing stability in suppliers, partners betting on the long arc. Dell the company didn’t transform by spreadsheet alone. It transformed because thousands of people executed through ambiguity, quarter after quarter, year after year.

Michael Dell’s personal arc mirrors the business. He went from dorm-room hustler to Fortune 500 CEO to the leader of the biggest tech LBO of its era. And even as his wealth ballooned, the thing that kept showing up in the story wasn’t extravagance—it was persistence.

The Legacy

Dell’s lasting legacy isn’t only that it made a lot of money. It’s that it proved reinvention is possible at scale.

A PC pioneer that lost the crown became an enterprise infrastructure heavyweight. A company written off as yesterday’s news found a role again—now, as an enabler of AI-era computing. Dell didn’t escape the forces that reshape tech. It survived them, adapted to them, and occasionally used them.

It also demonstrated something that’s easy to say and hard to execute: financial engineering and operational excellence aren’t enemies. Done well, they’re complements. The direct model was a business model innovation and a working-capital advantage. The LBO created space for a portfolio shift. The EMC deal created breadth. The VMware spin simplified governance and accelerated debt paydown.

The structures weren’t the point. The structures bought time, options, and freedom of motion.

Looking Forward

None of this guarantees the future. AI demand could cool. Cloud providers could pull more workloads away. New architectures could disrupt today’s infrastructure stacks. Supply chains and geopolitics could get harsher, not easier.

But the safest bet in the Dell story has never been a specific product cycle. It’s the pattern: when the ground moves, Dell tends to move with it—sometimes late, sometimes painfully, but rarely passively.

And Michael Dell still doesn’t sound like someone writing an epilogue. He sounds like someone still playing the game.

For investors, founders, and operators, the takeaway isn’t that transformation is easy. It’s that transformation is possible—but only if you’re willing to pay its price: years of uncertainty, unpopular decisions, and the discipline to keep going when the narrative turns against you.

The teenager hiding computer parts from his parents didn’t just build a company. He built a machine that learned how to reinvent itself. And that, more than any deal size or stock price, is the real lesson of Dell.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music