CommScope: From Cable Pioneer to Network Infrastructure Giant

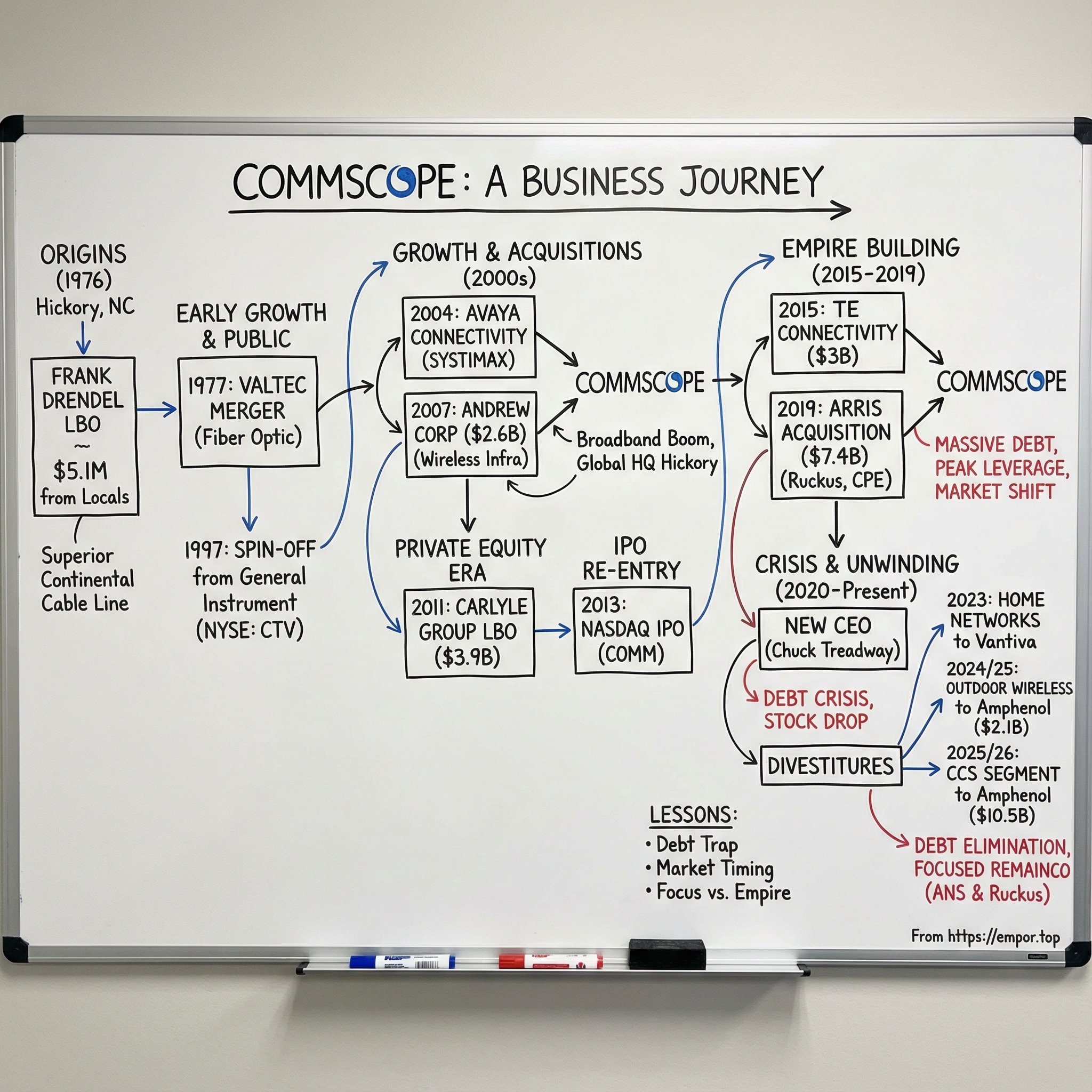

The rain pounded against the windows of CommScope's Hickory, North Carolina headquarters on a humid August morning in 1976. Inside a modest conference room, Frank Drendel, a 32-year-old cable industry veteran with an engineer's precision and an entrepreneur's hunger, signed the papers that would transform a struggling product line into one of telecommunications' most consequential companies. With $5.1 million raised from local investors—textile magnates, furniture barons, and small-town bankers who believed in his vision—Drendel and his partner Jearld Leonhardt had just purchased the CommScope product line from Superior Continental Corporation.

The moment was both an ending and a beginning. For Continental Telephone Company, it meant divesting a money-losing cable division that had generated just $10 million in annual sales. For Drendel, who had been tasked with selling off the very business he now owned, it represented the ultimate insider's play—a leveraged buyout before the term became Wall Street gospel. He engineered the first leveraged buyout in the cable business, knowing the industry was ranked dead last among fifteen suppliers but convinced that "you couldn't keep cable down." As he later admitted with characteristic bluntness: "I needed a damn job!"

Fast forward nearly five decades, and that kitchen-table startup has morphed into something unrecognizable from its origins. In August 2025, CommScope announced the sale of its Connectivity and Cable Solutions segment to Amphenol Corporation for $10.5 billion in cash, a transaction approved by stockholders in October 2025 that is anticipated to eliminate substantially all of the company's debt upon closing. This latest divestiture caps a remarkable unraveling—or perhaps liberation—from the debt-fueled empire building that once defined the company's strategy.

What happened in between reads like a compressed history of American capitalism itself: family dynasties giving way to professional management, regional manufacturers becoming global conglomerates, private equity firms extracting value through financial engineering, and ultimately, the painful recognition that bigger isn't always better. It's a story of coaxial cables and fiber optics, yes, but also of human ambition, miscalculated mergers, and the relentless march of technological change that can transform yesterday's crown jewels into today's stranded assets.

Origins & The Drendel Era (1953-1997)

The roots of CommScope stretch back to 1953, when Superior Continental Cable set up shop in Hickory, a town better known for furniture manufacturing than high technology. Superior Continental Cable was founded in 1953 in Hickory, North Carolina, and in 1961 created a division called Comm/Scope, which developed CATV systems and sold a coaxial cable named CommScope. In 1967, Superior was acquired by Continental Telephone Company, with CommScope becoming a division of Continental.

But the real story begins with Frank Drendel, a Northern Illinois University marketing graduate who had climbed through the cable industry's ranks with the determination of someone who understood both its technical complexity and business potential. Drendel's initial experience came as a cable installer while attending college, working for De Kalb Vogel, a subsidiary of Continental Telephone, where he learned on an SKL-222 system. He became an assistant manager for Allied Video, went into sales for Anaconda Wire and Cable Group, and later became assistant vice-president of operations for Continental Transmission, a large MSO in the United States.

By 1975, the industry was in turmoil. The government had forced telephone companies to divest any co-located cable properties. After divisions of Superior were sold off, CommScope was the only division left—what Drendel defined as merely a "product line" during a time when regulations had tightened on pole attachment, non-duplication, and bringing in distant signals. Continental wanted out, and they tapped Drendel to find a buyer.

The subsequent buyout was a masterpiece of insider knowledge and local relationships. Continental executives told Drendel: "We'll let you buy this business because you've always been straight with us," and carried him on the note so he could outbid other potential buyers. On August 16, 1976, Drendel woke up as owner of a "teeny little company in Hickory" with backing from powerful local families including the Shufords and Boyd Lee George.

The early years demanded both technical innovation and financial creativity. In 1977, CommScope merged with Valtec, a fiber optic manufacturer. This pivotal union led to a significant milestone in 1979 when Valtech donated fiber optic lines and equipment to link the U.S. House of Representatives to C-SPAN studios, enabling the first live broadcast of U.S. Congressional proceedings. This wasn't just corporate philanthropy—it was strategic positioning, demonstrating CommScope's capabilities at the intersection of technology and politics.

In 1980, Valtec sold to M/A-Com Inc. to strengthen both units, with CommScope becoming part of M/A-Com's Cable Home Group and Drendel becoming vice-chairman of the parent company while continuing to head CommScope. In 1983, CommScope established its Network Cable division for computer networks and specialized wire markets. In 1986, the Cable Home Group was sold to General Instrument Corporation.

The General Instrument years proved transformative. Drendel became chairman and CEO of the CommScope subsidiary. In 1988, he led another investor group to buy back a significant interest, though independence lasted just two years before General Instrument, being acquired by Forstmann Little & Co., reacquired CommScope in 1990.

The path to public markets came through corporate restructuring. In 1997, General Instrument split into three independent, publicly traded companies, with its cable operations spun off as CommScope. At this point, CommScope reported annual revenues of $560 million and was the leading coaxial cable provider to cable TV operators. After two decades of ownership changes, management buyouts, and strategic pivots, Frank Drendel's CommScope was finally a standalone public company, ready to pursue its destiny as more than just a cable supplier.

The First Public Company Era (1997-2011)

The late 1990s cable boom transformed CommScope from a regional manufacturer into a national powerhouse. As Americans embraced broadband internet and digital cable television, CommScope's coaxial cables became the physical backbone of the information superhighway. Revenue surged as cable operators raced to upgrade their networks, and CommScope's manufacturing facilities in North Carolina ran three shifts to meet demand.

In 2000, CommScope opened its new global headquarters in Hickory, North Carolina, a gleaming testament to the company's success in its hometown. But Drendel understood that organic growth alone wouldn't sustain CommScope's momentum. The company needed to diversify beyond coaxial cable before technological disruption rendered its core products obsolete.

The first major acquisition came in 2004, fundamentally reshaping CommScope's identity. CommScope acquired Avaya's Connectivity Solutions cabling unit and inherited the SYSTIMAX brand, perhaps best known for its enterprise cabling systems. Avaya's Carrier Solutions, which offered products for switching and transmission applications in telephone central offices and secure environmental enclosures, also became part of CommScope. This acquisition doubled CommScope's size.

The SYSTIMAX acquisition wasn't just about scale—it was about entering the lucrative enterprise market where margins were higher and customer relationships stickier. The acquisition of Connectivity Solutions from Avaya for $250 million in cash plus stock and assumption of liabilities was a major brand in structured cabling for LAN solutions that greatly enhanced CommScope's global position. CommScope finished 2004 with sales of $1.15 billion and net income of nearly $75.8 million.

But the transformational moment came in 2007 with the Andrew Corporation acquisition. Andrew wasn't just another cable company—it was CommScope's gateway into the wireless infrastructure revolution. The pursuit of Andrew had actually begun a year earlier, with CommScope making an unsolicited $1.7 billion bid in 2006 that Andrew's board rejected. Drendel, never one to accept defeat, waited for the contractually required cooling-off period to expire before returning with a better offer.

On June 27, 2007, the companies entered into a definitive agreement under which CommScope would acquire all outstanding shares of Andrew for $15.00 per share, at least 90 percent in cash. The transaction valued at approximately $2.6 billion was expected to be accretive to CommScope's cash earnings per share in the first full year. The purchase price represented a 13% premium over Andrew's 30-day average, 21% over the 60-day average, and 16% over the prior day's close.

The strategic rationale was compelling. Andrew's products included antennas, cables, amplifiers, repeaters, transceivers, as well as software and training for the broadband and cellular industries. The combined company would be a global leader in infrastructure solutions for communications networks. "In-building wireless coverage has been our missing link," explained CommScope president Brian Garrett. The combination would allow cross-selling of Andrew's wireless products with CommScope's enterprise presence and expand broadband connectivity products globally.

On December 27, 2007, CommScope completed the acquisition for approximately $2.65 billion. Andrew stockholders received $13.50 in cash and 0.031543 shares of CommScope stock per share. CommScope funded the transaction through $2.5 billion in senior secured credit facilities including a $1.35 billion seven-year term loan at LIBOR plus 250 basis points and a $750 million six-year term loan at LIBOR plus 225 basis points.

The timing proved challenging. The global financial crisis erupted just months after the deal closed, credit markets froze, and CommScope found itself carrying significant debt as customers slashed capital spending. Yet even in crisis, CommScope found opportunities. In 2008, the company was chosen to provide the Dallas Cowboys with connectivity for their new stadium starting with the 2009 NFL season, using over 5 million feet of copper and fiber-optic cabling—a high-profile win that showcased CommScope's capabilities in complex venue installations.

By 2010, CommScope had weathered the financial storm but emerged wounded. The company's stock price languished, debt service consumed cash flow, and activist investors circled. The public markets that had once celebrated CommScope's growth story now punished it for excessive leverage and slowing organic growth. The stage was set for the next act: private equity.

The Carlyle Chapter: Going Private (2011-2013)

The boardroom at CommScope's Hickory headquarters buzzed with tension on October 27, 2010. After months of negotiations, strategic reviews, and competing visions for the company's future, the board unanimously approved a deal that would take CommScope private once again. The Carlyle Group would acquire all outstanding shares for $31.50 per share in cash, representing a premium of approximately 36% over CommScope's closing stock price on October 22, 2010, and 39% over the 30-day average. The total transaction was valued at approximately $3.9 billion.

For Frank Drendel, now 66 and having led CommScope for 34 years, the Carlyle deal represented both vindication and transition. "CommScope has made many important advancements in supporting customers with infrastructure solutions over the last 35 years, and I am confident that this combination with Carlyle is a great step forward in our company's progress," said Drendel.

The deal structure revealed classic private equity engineering. Equity financing came from Carlyle Partners V, a $13.7 billion U.S. buyout fund, and Carlyle Europe Partners III, a €5.4 billion European buyout fund, with debt financing provided by J.P. Morgan. Carlyle invested $1.6 billion in equity with the remaining financing coming from $2.5 billion in debt to finance the acquisition and related costs.

The acquisition closed on January 14, 2011. As previously disclosed, Marvin S. "Eddie" Edwards Jr., CommScope's president and chief operating officer, was appointed president and chief executive officer, succeeding Frank M. Drendel, who had served as CEO since founding the company in 1976. Edwards joined the board while Drendel continued as chairman.

The leadership transition marked a generational shift. Edwards, a Tennessee Tech engineering graduate who had joined CommScope in 2005, represented professional management taking over from the founder-entrepreneur. While Drendel remained chairman and maintained significant influence, the operational reins now belonged to Edwards and his team, with Carlyle partners providing strategic oversight.

Under Carlyle ownership, CommScope underwent the typical private equity transformation: aggressive cost cutting, operational streamlining, and preparation for a quick exit. Manufacturing was consolidated, headcount reduced, and every expense scrutinized. The company also refinanced its debt to take advantage of lower interest rates, a move that would prove crucial for the eventual IPO.

The speed of Carlyle's exit surprised even seasoned observers. Just two years after taking CommScope private, Carlyle began preparing for an initial public offering. The private equity firm had succeeded in its financial engineering: margins had improved, debt had been restructured, and market conditions had stabilized enough to attract public investors again.

In October 2013, CommScope commenced an IPO of 38,461,537 shares, with CommScope selling 30,769,230 shares and Carlyle selling 7,692,307. The anticipated price range was $18-21 per share, and the company applied for listing on NASDAQ under the symbol "COMM".

But market realities forced a pricing adjustment. CommScope priced its IPO at $15.00 per share, below the initial range. The shares began trading October 25, 2013 on NASDAQ. CommScope offered 30,769,230 shares while Carlyle sold 7,692,307 shares. The IPO reduced Carlyle's ownership to approximately 77.9%. CommScope raised approximately $433 million net of transaction costs, using proceeds plus cash on hand to redeem $400 million of 8.25% senior notes plus premium and accrued interest.

Led by CEO Eddie Edwards, the senior leadership team celebrated at the NASDAQ MarketSite in Times Square during the Opening Bell ceremony. CommScope re-entered public trading after becoming private in early 2011 following the Carlyle acquisition. The company had come full circle, but with a crucial difference: Carlyle remained the dominant shareholder, maintaining effective control while gradually monetizing its investment.

Building the Empire: Major Acquisitions (2015-2019)

By 2015, CommScope faced an existential challenge. The company had successfully navigated its return to public markets, but organic growth remained elusive. Cable operators were consolidating, reducing the customer base. Wireless carriers demanded lower prices for commodity products. Enterprise customers increasingly chose low-cost Asian manufacturers for basic cabling needs. Eddie Edwards and his team concluded that transformational acquisitions offered the only path to sustainable growth.

The first major move came in January 2015. CommScope agreed to acquire TE Connectivity's Telecom, Enterprise and Wireless businesses in an all-cash transaction valued at approximately $3 billion. The deal strengthened CommScope's position as a leading communications infrastructure provider with deeper resources to meet the world's growing demand for network bandwidth.

The TE Connectivity businesses brought critical capabilities CommScope lacked. The businesses generated annual revenues of approximately $1.9 billion in fiscal 2014, consisting of $1.1 billion from Telecom where it was a world leader, $627 million from Enterprise, and $164 million from Wireless. More importantly, they provided entry into the fiber-to-the-home market just as telecom operators began massive fiber deployments.

CommScope financed the transaction through cash on hand and up to $3 billion of incremental debt, with financing commitments from J.P. Morgan, BofA Merrill Lynch, Deutsche Bank and Wells Fargo. Upon completion, CommScope's net debt to 2014 pro forma adjusted EBITDA ratio was expected to total approximately 4.0x to 4.5x—aggressive but manageable leverage by industry standards.

The integration proceeded smoothly. Pro forma net sales for the 12-month period ended June 30, 2015 were approximately $5.3 billion with adjusted EBITDA of approximately $1 billion. The company now held approximately 9,800 patents and patent applications with R&D investment over $200 million annually. The newly-acquired BNS businesses operated as a separate segment with David Redfern continuing as leader reporting to COO Randy Crenshaw.

But Edwards wasn't finished. Later in 2015, CommScope acquired Airvana, a privately held company specializing in small cell solutions for wireless networks. While smaller than the TE Connectivity deal, Airvana represented a strategic bet on network densification as carriers prepared for 5G deployments.

These acquisitions, however, paled in comparison to what came next. On November 8, 2018, CommScope announced its most ambitious deal yet: the acquisition of Arris International for $7.4 billion. The transaction completed on April 4, 2019, doubling CommScope's size with combined revenues of approximately $11.3 billion.

The Arris acquisition represented more than just scale—it was a transformational bet on convergence. CommScope acquired Ruckus Networks and ICX Switch, two companies Arris had recently acquired from Broadcom, with Arris and Ruckus becoming brands of CommScope. Former Arris CEO Bruce McClelland assumed the role of CommScope chief operating officer.

The strategic logic appeared compelling. The deal would better position CommScope for favorable industry trends, more than double its addressable market to over $60 billion, expand product offerings and R&D capabilities, and deliver immediate cost savings rising to at least $150 million annually within three years. "After a comprehensive evaluation of our business and the evolving industry, we are confident that combining with ARRIS is the best path forward," said Edwards. "CommScope and ARRIS will bring together complementary assets and capabilities for end-to-end solutions neither company could achieve alone".

The financing structure revealed both ambition and risk. The Carlyle Group reestablished an ownership position through a $1 billion minority equity investment. CommScope financed the remainder through cash on hand, existing credit facilities and approximately $6.3 billion of incremental debt with commitments from J.P. Morgan, BofA Merrill Lynch and Deutsche Bank. This pushed CommScope's total debt load to unprecedented levels, with net leverage jumping above 5x EBITDA.

Wall Street's reaction was swift and brutal. CommScope shares dropped more than 18% on announcement over concerns about the heavy debt burden, though CEO Edwards reassured investors that the company had successfully managed leverage from past acquisitions. The integration began promisingly, with CommScope realigning into four segments to capture synergies.

By December 2019, CommScope had realigned its business following the April completion of the $7.4 billion Arris acquisition that greatly expanded its portfolio. The deal combined Arris' position as a major cable industry supplier of CPE, video and broadband infrastructure with CommScope's fiber and network infrastructure portfolio. Arris also brought Ruckus Networks and ICX Switch from recent Broadcom acquisitions.

But storm clouds were gathering. The COVID-19 pandemic erupted just months after the deal closed, disrupting supply chains and customer spending patterns. More fundamentally, CommScope had badly misjudged the trajectory of the cable industry. Cord-cutting accelerated, reducing demand for set-top boxes. Cable operators delayed network upgrades. Enterprise customers postponed installations. The synergies that justified the deal's massive debt load failed to materialize on schedule.

By late 2020, CommScope's board concluded dramatic action was needed. The empire built through aggressive acquisitions was about to be systematically dismantled.

The Great Unwinding: Debt Crisis and Divestitures (2020-Present)

On October 1, 2020, CommScope announced that Charles Treadway would succeed Eddie Edwards as the company's new president and CEO. The company also announced that Bud Watts would replace Frank Drendel as chairman, with Drendel being named chairman emeritus. The leadership transition sent a clear message: CommScope needed a turnaround specialist, not a builder.

Chuck Treadway arrived with a mandate to fix what many considered unfixable. He most recently served as CEO of Accudyne Industries from 2016 to 2020, where he drove significant revenue growth and margin expansion with strategic focus, product innovation, improved sales and marketing efforts, and disciplined execution. His appointment came as CommScope's debt load had become existential, with interest payments consuming cash flow and limiting strategic flexibility.

"I'm excited to join CommScope, a company with a legacy of innovation," said Treadway. "I have great respect for all CommScope has accomplished and for the team's relentless focus on delivering for customers while aggressively managing costs during challenging times. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of reliable network connectivity".

Behind the diplomatic language, Treadway faced brutal math. CommScope's debt exceeded $9 billion while EBITDA had declined. The company's leverage ratio approached dangerous levels that threatened covenant breaches. Rating agencies had downgraded CommScope's debt deep into junk territory. Without dramatic action, bankruptcy loomed as a real possibility.

Treadway launched "CommScope NEXT," a comprehensive restructuring that would fundamentally reshape the company. The initiative focused on getting the company back on solid financial footing through an evaluation of CommScope's full portfolio. The process included extensive M&A activity with proceeds going toward lowering CommScope's towering debt.

The first major move was initially intended as a spin-off. CommScope announced plans to separate its Home Networks business as an independent public company, allowing each entity to focus on its distinct market opportunities. But market conditions and investor skepticism forced a pivot. In October 2023, CommScope sold its home networks division to Vantiva for a 25% stake in Vantiva, effectively removing the struggling CPE business from its books while maintaining some upside participation.

The divestiture accelerated in 2024. On July 18, 2024, CommScope announced the sale of its Outdoor Wireless Networks and Distributed Antenna Systems businesses to Amphenol for approximately $2.1 billion in cash. "This transaction allows CommScope to increase focus and strengthen its CommScope NEXT priorities," said Treadway.

The OWN and DAS sale closed on January 31, 2025. Proceeds were used to pay transaction fees and repay all outstanding amounts under the asset-backed revolving credit facility, partially repay 4.750% Senior Secured Notes due 2029, and fully repay 6.000% Senior Secured Notes due 2026. The deal effectively transferred the entire former Andrew Corporation product portfolio to Amphenol, undoing CommScope's landmark 2007 acquisition.

But the biggest bombshell came in August 2025. CommScope announced it had entered into a definitive agreement to sell its Connectivity and Cable Solutions segment to Amphenol for approximately $10.5 billion in cash. The sale is expected to close within the first half of 2026, subject to customary closing conditions including regulatory approvals and shareholder vote.

The CCS divestiture represents the ultimate unwinding. The business generated about $2.8 billion in net sales in 2024, driven by data center demand to support generative AI buildouts—making it CommScope's largest and most profitable segment. CommScope expects net proceeds after taxes and expenses of approximately $10 billion. After repaying all debt and redeeming preferred equity held by Carlyle, the company plans to distribute significant excess cash to shareholders as a dividend within 60-90 days following closing.

The much smaller CommScope that will remain consists of Access Network Solutions (ANS) and Ruckus. But CEO Chuck Treadway did not slam the door on future moves when asked if the CCS deal was final, diplomatically noting CommScope will focus on running the business while continuing to invest in ANS and Ruckus.

What remains is a shadow of the empire Eddie Edwards and Frank Drendel built. ANS generated about $360 million in net sales in 2024, while the Ruckus-led NICS business generated $1.05 billion. Combined, these businesses represent less than 20% of CommScope's peak revenues. Yet freed from crushing debt, they may finally have room to breathe, innovate, and grow organically—something the debt-laden conglomerate could never achieve.

Technology & Product Evolution

CommScope's technological journey mirrors the broader evolution of communications infrastructure, from analog to digital, copper to fiber, wired to wireless. Each transition challenged the company to cannibalize existing products while investing in uncertain futures—a delicate balance that determined success or failure.

The company's origins in coaxial cable seem quaint in today's fiber-optic world, yet coax remained surprisingly resilient. The CATV systems of the 1970s evolved into hybrid fiber-coax (HFC) networks that still deliver broadband to millions of homes. CommScope's innovations in coaxial cable—better shielding, lower signal loss, weather resistance—enabled the cable TV revolution that transformed American media consumption.

The 1983 formation of CommScope's Network Cable division marked the company's first major technological pivot. The establishment of the Network Cable division marked strategic expansion into producing cables for computer networks and specialized wire markets, a key step in diversification. As businesses networked their computers, CommScope's structured cabling became the nervous system of the corporate world.

The 2004 SYSTIMAX acquisition brought enterprise-grade capabilities that transcended basic connectivity. SYSTIMAX wasn't just cable—it was an ecosystem of products, software, and services that managed the physical layer of enterprise networks. The brand commanded premium pricing because IT managers trusted it for mission-critical installations where downtime meant millions in losses.

The Andrew Corporation acquisition in 2007 catapulted CommScope into wireless infrastructure at the perfect moment. As smartphones proliferated, wireless carriers needed massive network densification. Andrew's base station antennas, remote radio heads, and transmission lines became essential components of the 4G buildout. CommScope's engineers learned to optimize radio frequency performance, manage passive intermodulation, and design products that could withstand extreme weather on cell towers.

The shift to 5G presented both opportunity and challenge. The technology required new spectrum bands, massive MIMO antennas, and small cells deployed deep into neighborhoods. In October 2020, CommScope acquired the patent portfolio for virtual radio access networks (vRAN) from Phluido, specializing in RAN virtualization and disaggregation, positioning itself for the software-defined future of wireless networks.

But CommScope's most prescient technology investments came in fiber optics. While the company's roots were in copper, management recognized fiber's inevitability. The TE Connectivity acquisition brought world-class fiber connectivity capabilities just as hyperscale data centers exploded in size and complexity. Every Google search, Netflix stream, and Zoom call ultimately depends on the kind of high-density fiber connections CommScope manufactures.

The data center opportunity proved particularly transformative. As cloud computing concentrated computing power in massive facilities, the internal connectivity requirements grew exponentially. CommScope's high-density fiber panels, pre-terminated solutions, and automated infrastructure management systems became critical for data center operators managing millions of connections. The company claims its solutions are deployed in most of the world's largest data centers.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated every digital trend CommScope had bet on. Remote work drove enterprise network upgrades. Video streaming stressed broadband networks. 5G deployments accelerated to handle surging mobile data. Data centers expanded at unprecedented rates. Yet ironically, CommScope's debt burden prevented it from fully capitalizing on these tailwinds.

Recent innovations focus on convergence and intelligence. In May 2025, CommScope launched its XPND modular fiber termination platform featuring interchangeable panels and cassettes, allowing service providers to customize configurations and expand capacity as needed. Products increasingly incorporate sensors, software, and analytics that transform passive infrastructure into intelligent systems that self-monitor, predict failures, and optimize performance.

The DOCSIS 4.0 transition represents CommScope's latest technological battleground. ANS saw revenues soar 65% to $322.5 million driven by record deployments of DOCSIS 4.0 amplifiers, nodes and licenses. Sales included Full Duplex amplifiers for Comcast's DOCSIS 4.0 upgrades. CommScope also won a deal for Extended Spectrum DOCSIS amps for Charter Communications and is developing products powered by unified silicon from Broadcom supporting both FDX and ESD flavors of DOCSIS 4.0.

Playbook: Lessons from CommScope

CommScope's journey offers a masterclass in both strategic success and cautionary failure. The company's playbook reveals timeless lessons about growth, debt, and the dangers of empire building in cyclical industries.

The Roll-Up Strategy: When It Works and When It Doesn't

CommScope perfected the infrastructure roll-up: acquire complementary businesses, cut costs through consolidation, and cross-sell products to expanded customer bases. The strategy worked brilliantly when acquisitions were digestible (SYSTIMAX), strategically essential (Andrew), or financially disciplined (TE Connectivity). It failed catastrophically when CommScope overreached with Arris, paying peak multiples for a declining business while loading up on debt just before a market downturn.

The lesson: roll-ups require more than financial engineering. Successful consolidation demands operational excellence, cultural integration, and timing. CommScope excelled at the first, struggled with the second, and catastrophically failed at the third with Arris.

Private Equity Dynamics: Multiple Buyouts, Different Playbooks

Carlyle's involvement with CommScope reveals private equity's evolution. The 2011 buyout followed the classic LBO playbook: buy an undervalued public company, cut costs, refinance debt, and exit quickly through an IPO. The 2013 IPO succeeded because Carlyle's operational improvements were real and sustainable.

But Carlyle's return in 2018 as a minority investor in the Arris deal showed private equity's new model: provide flexible capital to public companies making transformational acquisitions. This "private equity lite" approach offers upside with limited downside—Carlyle invested $1 billion but avoided responsibility for CommScope's subsequent struggles.

Debt as a Double-Edged Sword

Leverage amplified CommScope's returns during growth periods but nearly destroyed the company when markets turned. The company's debt journey reads like a morality tale: modest leverage for strategic acquisitions (Andrew) enabled growth, while excessive leverage for empire building (Arris) created an existential crisis.

The key insight: debt capacity isn't just about coverage ratios and EBITDA multiples. It's about business quality, market cycles, and strategic flexibility. CommScope's infrastructure products generated steady cash flows that could support moderate leverage. But high leverage removed all margin for error just when technological disruption and market consolidation demanded maximum flexibility.

Market Timing: Riding Waves vs. Creating Them

CommScope succeeded when it rode secular trends: cable TV expansion in the 1980s, enterprise networking in the 1990s, wireless buildout in the 2000s, and data center growth in the 2010s. The company failed when it tried to create its own destiny through sheer scale, believing that size alone would generate synergies and pricing power.

The Conglomerate Discount

Markets consistently undervalued CommScope's diverse portfolio, applying a "conglomerate discount" that assumed the whole was worth less than its parts. This discount reflected real challenges: difficulty managing diverse businesses, unclear strategic focus, and limited synergies between units. The current break-up validates what activists long argued: CommScope's businesses were worth more apart than together.

Managing Technological Disruption

CommScope navigated multiple technological transitions—copper to fiber, analog to digital, wired to wireless—by embracing cannibalization. The company accepted that new technologies would destroy old revenue streams and invested accordingly. This forward-looking approach worked until CommScope became so leveraged that it couldn't afford to invest in the next generation of technologies.

Capital Allocation in Cyclical Industries

Infrastructure spending is inherently cyclical, driven by carrier capital budgets, technology upgrade cycles, and macroeconomic conditions. CommScope's capital allocation failed to account for this cyclicality, using peak EBITDA to justify debt levels that became unsustainable in downturns. The lesson: in cyclical industries, balance sheets must be structured for the trough, not the peak.

Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's 5 Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW to MODERATE

The infrastructure market presents significant barriers to entry. Manufacturing requires specialized equipment, extensive capital investment, and decades of process refinement. More importantly, customer relationships take years to build—carriers and data center operators won't risk critical infrastructure on unproven suppliers. However, Chinese manufacturers have successfully entered commodity product segments, and software-defined networking threatens to commoditize hardware over time.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

While raw materials like copper and plastic are commodities, specialized components require sophisticated suppliers. CommScope depends on companies like Broadcom for silicon, Corning for optical fiber, and various chemical companies for specialized polymers. These suppliers have some pricing power, particularly during shortage periods, but CommScope's scale provides negotiating leverage.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

CommScope's customer concentration creates significant vulnerability. The top carriers and hyperscale data center operators command enormous purchasing power. Verizon, AT&T, Charter, and Comcast can demand price concessions, extended payment terms, and customized products. The consolidation of cable operators and wireless carriers has only intensified this pressure.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE to HIGH

Technological substitution represents an constant threat. Fiber replaces copper. Wireless substitutes for wired. Software-defined networks reduce hardware dependency. While CommScope has successfully navigated past transitions, each new technology wave threatens existing revenue streams. The company must continuously innovate or face obsolescence.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

CommScope faces formidable competitors across every segment. Corning dominates optical fiber. Prysmian leads in cables. Chinese manufacturers like Huawei and ZTE offer integrated solutions at aggressive prices. The industry suffers from overcapacity in commodity products while facing shortages in cutting-edge technologies. Price competition is fierce, and differentiation increasingly difficult.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: STRONG but DECLINING

CommScope's manufacturing scale once provided significant cost advantages. Large production runs, automated factories, and global sourcing created per-unit cost advantages smaller competitors couldn't match. However, the divestiture of major business units eliminates much of this scale advantage. The remaining businesses lack the volume to justify world-class manufacturing investments.

Network Economies: WEAK

Unlike consumer technology companies, CommScope doesn't benefit from network effects. Additional customers don't make the product more valuable to existing customers. B2B infrastructure products are evaluated on technical specifications and price, not ecosystem benefits.

Counter-positioning: WEAK

As an incumbent, CommScope cannot counter-position against established competitors. The company's strategies—scale, vertical integration, broad portfolio—represent industry conventional wisdom rather than revolutionary approaches. Start-ups and Chinese competitors better execute counter-positioning by offering radically lower prices or innovative business models.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Technical specifications, certifications, and operational integration create moderate switching costs. Carriers can't easily switch vendors mid-deployment. Data centers standardize on specific connectivity systems. However, these switching costs provide temporary protection rather than permanent moats. New deployment cycles offer opportunities for competitors to win business.

Branding: WEAK in commodity products, MODERATE in specialized solutions

The CommScope brand carries weight in technical circles but lacks broader recognition. Products like SYSTIMAX and Ruckus command some premium, but most infrastructure products are evaluated on specifications and price rather than brand. Customers care about reliability and performance, not logos.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

CommScope's patent portfolio, with over 15,000 patents and applications, provides some protection. Customer relationships, particularly with tier-one carriers, represent valuable assets. The installed base of products creates replacement and upgrade opportunities. However, none of these resources are truly unique or irreplaceable.

Process Power: MODERATE but ERODING

Decades of manufacturing experience created process advantages in quality, cost, and delivery. CommScope's engineers solved complex problems in radio frequency management, fiber optic connectivity, and network reliability. But the divestiture of major businesses transfers much of this process knowledge to Amphenol, leaving the remaining CommScope with diminished capabilities.

Bear vs. Bull Case

Bear Case:

The bear case for CommScope starts with simple math: even after divestitures, the company faces a challenging financial position. The smaller "RemainCo" must compete against larger, better-capitalized competitors while managing the complexities of separation. The ANS business depends heavily on cable operators who face secular decline from cord-cutting and wireless substitution. DOCSIS 4.0 deployments provide temporary relief, but the long-term trajectory points toward fiber, where CommScope has limited presence after selling CCS.

Customer concentration amplifies these risks. Comcast and Charter control ANS's fate. If either delays network upgrades or switches suppliers, CommScope's revenues would collapse. The company lacks bargaining power against these giants, who can demand price concessions that destroy margins. Meanwhile, competition intensifies as companies like Harmonic and Casa Systems target the same opportunities with innovative solutions.

Technology transitions threaten both remaining businesses. Virtualized networks reduce hardware dependency. Open RAN standards commoditize wireless infrastructure. Cloud-native architectures bypass traditional connectivity products. CommScope must invest heavily in R&D to remain relevant, but lacks the scale to match larger competitors' innovation spending.

The Ruckus business faces its own challenges. Enterprise WiFi is increasingly commoditized, with cloud-managed solutions from Cisco, Aruba, and others offering superior economics. The high-margin controller business erodes as customers shift to subscription models. Ruckus's technology leadership has diminished, and the brand lacks the investment needed to recapture its innovation edge.

Macroeconomic headwinds compound these structural challenges. Rising interest rates increase capital costs for customers. Economic uncertainty delays enterprise upgrades. Geopolitical tensions disrupt supply chains and increase component costs. Every external shock hits harder when a company lacks financial flexibility.

Most concerningly, CommScope's repeated restructurings have damaged employee morale and customer confidence. Talented engineers have departed for competitors. Key customers diversify suppliers to reduce CommScope dependency. The company's reputation has shifted from innovation leader to distressed asset—a perception that becomes self-fulfilling as opportunities disappear.

Bull Case:

The bull thesis rests on transformation: CommScope emerges from its restructuring as a focused, debt-free company positioned in attractive niches. The ANS business, despite its challenges, occupies an essential position in cable network evolution. Cable operators must upgrade their networks to compete with fiber—they have no choice. DOCSIS 4.0 represents a multi-billion dollar opportunity over the next five years, and CommScope's dominant position in amplifiers and nodes makes it irreplaceable.

The evidence already supports this thesis: ANS revenues soared 65% to $322.5 million driven by record DOCSIS 4.0 deployments. Comcast's aggressive upgrade timeline pulls forward demand that analysts had expected to materialize slowly. Charter's commitment to Extended Spectrum DOCSIS creates additional opportunity. International markets remain largely unpenetrated, offering geographic expansion potential.

The Ruckus business, while challenged, maintains strong positions in specific verticals. Educational institutions trust Ruckus for campus-wide deployments. Hospitality chains depend on its solutions for guest WiFi. Smart city initiatives leverage its outdoor wireless capabilities. These niche positions generate recurring revenue through refresh cycles and technology upgrades.

Data center growth provides unexpected tailwinds. While CommScope sold its connectivity products, the remaining businesses benefit from edge computing trends. Distributed data centers need wireless connectivity, network management, and access solutions—all areas where CommScope competes. The AI boom drives demand for any product that enables faster, more reliable connectivity.

Financial engineering creates additional upside. The company's dramatic deleveraging removes interest expense that consumed cash flow. Management can finally invest in product development rather than debt service. The simplified structure reduces overhead costs. Some analysts project the remaining businesses could generate EBITDA margins exceeding 25% once restructuring completes.

The strategic flexibility afforded by a clean balance sheet opens new possibilities. CommScope could acquire complementary technologies at reasonable valuations. Partnerships become possible without debt covenant restrictions. The company might even become an acquisition target itself, with strategic buyers paying premiums for its market positions.

Market sentiment often overshoots in both directions. CommScope traded at excessive valuations during its empire-building phase, then collapsed to distressed levels during its restructuring. The pendulum may swing back as investors recognize the value in focused, debt-free infrastructure businesses with essential market positions.

Grading & Final Thoughts

Acquisition Strategy: C+

CommScope demonstrated both brilliance and folly in its acquisition approach. The SYSTIMAX and Andrew deals were masterstrokes—strategically sound, financially disciplined, and well-integrated. The TE Connectivity acquisition made strategic sense despite its size. But the Arris deal was a disaster that nearly destroyed the company. Size became an end in itself rather than a means to strategic advantage. The grade reflects this mixed record: excellent tactical execution undermined by catastrophic strategic overreach.

Capital Allocation: D

This is CommScope's greatest failure. Management consistently prioritized growth over financial sustainability, using peak EBITDA multiples to justify unsustainable debt levels. They failed to maintain balance sheet flexibility for market downturns or technological disruptions. The repeated need for financial restructuring reveals systematic capital allocation failures. Only Treadway's recent divestitures prevent an F grade.

Operational Execution: B-

CommScope excelled at running its core businesses. Manufacturing efficiency was world-class. Product quality remained high. Customer service generally satisfied demanding clients. The company successfully integrated multiple acquisitions operationally, even if financial integration failed. The grade would be higher, but repeated restructurings disrupted operations and damaged employee morale.

Strategic Vision: B

Management correctly identified major industry trends: enterprise networking growth, wireless densification, data center expansion, and network convergence. CommScope positioned itself in attractive markets with secular tailwinds. The vision was sound—the execution was flawed. The company understood where the industry was heading but misjudged its ability to capture value from these trends while carrying excessive debt.

Management: C+

A tale of three leaders. Drendel (A-) built a successful company through vision and determination, though he stayed too long. Edwards (C-) grew the company but overleveraged it with Arris. Treadway (B+) is cleaning up predecessors' mistakes with pragmatic restructuring. The aggregate grade reflects this mixed performance: moments of brilliance offset by critical errors in judgment.

The Ultimate Lesson: Infrastructure Is Essential but Structure Matters

CommScope's journey teaches that owning essential infrastructure doesn't guarantee success. Financial structure matters as much as market structure. The company owned critical assets in attractive markets but destroyed value through excessive leverage and poor capital allocation. The best businesses in the world can't overcome bad balance sheets.

Epilogue & What's Next

As rain falls again on Hickory, North Carolina—nearly fifty years after Frank Drendel's leveraged buyout—CommScope faces an uncertain but oddly promising future. The company that once aspired to become the "everything store" of network infrastructure will soon be a focused specialist with two businesses generating perhaps $1.5 billion in combined revenue.

The numbers tell a story of dramatic shrinkage. From peak revenues exceeding $11 billion, CommScope will operate at barely 15% of its former size. From 30,000 employees, perhaps 5,000 will remain. From a sprawling portfolio spanning every aspect of network infrastructure, two narrow segments survive. By conventional measures, this represents corporate failure.

Yet destruction often precedes creation. The RemainCo, freed from crushing debt and stripped of distractions, might rediscover the entrepreneurial spirit that Frank Drendel brought to that kitchen table in 1976. ANS and Ruckus, while challenged, occupy defensible niches with real customer needs. A focused CommScope could innovate in ways the bloated conglomerate never could.

The infrastructure megatrends that drove CommScope's expansion remain intact. Data consumption grows exponentially. Networks require constant upgrades. The physical layer of the internet needs continuous investment. Someone must manufacture the products that enable digital transformation. The question isn't whether these markets will grow, but who will capture the value.

Chuck Treadway has proven remarkably effective at dismantling the empire others built. But can he build something new from the pieces that remain? When asked if the CCS sale was CommScope's final step, Treadway diplomatically noted the company will focus on running the business while continuing to invest in ANS and Ruckus. That careful non-answer suggests more changes may come.

The private equity playbook might repeat once more. With CommScope's valuation depressed and its balance sheet soon to be cleaned, the company could attract financial buyers seeking undervalued assets. The remaining businesses, properly managed and modestly leveraged, could generate attractive returns. The cycle of buyout, restructuring, and exit would begin anew.

Alternatively, strategic buyers might see opportunity in CommScope's focused positions. A larger technology company could acquire CommScope to secure cable network access or enterprise wireless capabilities. The patents, customer relationships, and technical expertise might be worth more to a strategic buyer than CommScope could realize independently.

Or perhaps—and this seems most intriguing—CommScope might surprise everyone by thriving as a smaller, focused company. Not every business needs to be a giant. Not every success requires empire building. Sometimes, the best strategy is to do a few things exceptionally well rather than many things adequately.

The transformation from $5.1 million buyout to $10.5 billion divestiture spans multiple business cycles, technological revolutions, and ownership structures. It encompasses triumph and failure, vision and hubris, creation and destruction. Through it all, CommScope's products quietly enabled the communications revolution that transformed modern life.

Frank Drendel, now chairman emeritus at age 81, watches his life's work being systematically unwound. One wonders what he thinks as Amphenol acquires the businesses he spent decades assembling. Does he see failure in the dismantling of his empire, or wisdom in acknowledging that times change and companies must adapt?

The answer might lie in CommScope's original mission: connecting people through communications infrastructure. That mission remains valid whether the company is worth $10 billion or $1 billion, whether it employs 30,000 or 3,000. The tools change—copper to fiber, hardware to software, products to services—but the need for connection endures.

As CommScope enters its sixth decade, its greatest challenge isn't technology or competition or market dynamics. It's answering a fundamental question: What does it mean to be CommScope in an age when the empire is gone, the debt is repaid, and the future is unwritten?

The rain has stopped in Hickory. Tomorrow will bring new challenges, new opportunities, and perhaps new ownership. But tonight, in the quiet after the storm, CommScope endures—smaller, humbler, but still essential to the networks that bind our modern world together. Whether that's enough for long-term success remains to be seen. But after nearly fifty years of boom and bust, growth and retrenchment, triumph and near-disaster, survival itself represents a kind of victory.

The story of CommScope isn't over. It's merely entering its next chapter, one that will be written by new leaders facing new challenges in new markets. The empire may be gone, but the need for network infrastructure remains. And somewhere in Hickory, North Carolina, engineers still come to work each day, designing and building the products that make modern communications possible.

That, perhaps, is Frank Drendel's true legacy: not the empire he built or the wealth he created, but the simple, essential fact that CommScope continues to connect the world, one cable, one antenna, one network at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music