Amazon: The Everything Store That Ate the World

Introduction

In the summer of 1994, a thirty-year-old hedge fund analyst drove across the country with his wife, dictating a business plan into a laptop while she steered. He had no product, no warehouse, and no customers. Three decades later, the company he founded processes roughly four hundred million product listings, operates the world's largest cloud computing platform, and employs over 1.5 million people. Amazon's market capitalization has crossed the two trillion dollar mark, making it one of the most valuable enterprises in human history.

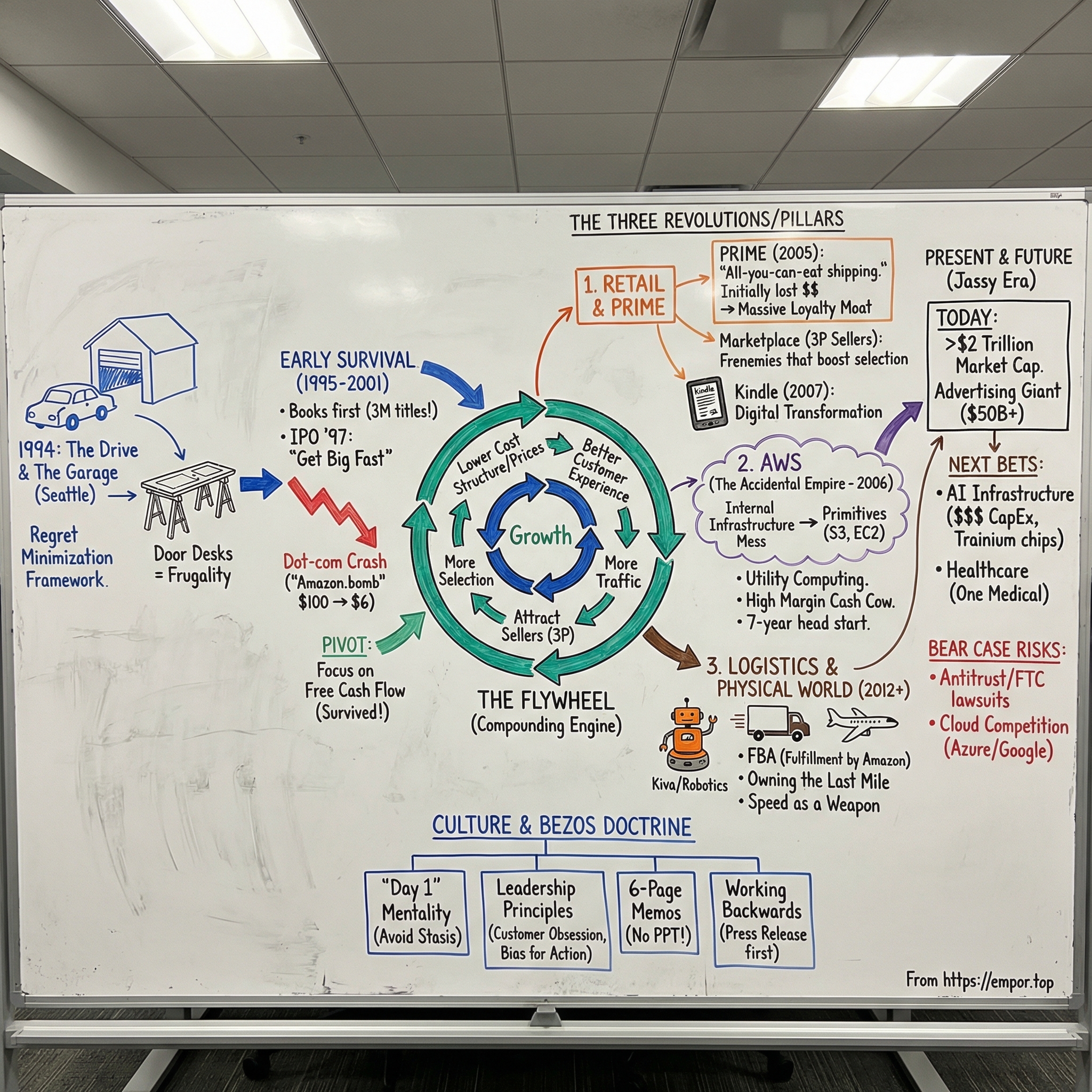

The question this story tries to answer is deceptively simple: how did an online bookstore become the infrastructure layer of modern commerce, computing, and logistics? The answer involves three intertwined revolutions. The first was retail, where Amazon redefined what it means to buy something. The second was cloud computing, where a team inside the company accidentally invented an industry worth hundreds of billions of dollars. The third was logistics, where Amazon built a delivery network rivaling those of sovereign postal services. Each revolution fed the others, creating a flywheel of compounding advantages that competitors have spent decades trying to replicate.

This is the story of that flywheel, the people who built it, and the strategic decisions that turned a money-losing dot-com into the backbone of the digital economy.

Pre-Internet Commerce and the Bezos Origin Story

To understand why Amazon worked, you first have to understand what shopping looked like before the internet. In 1994, American retail was dominated by a handful of giants. Walmart had perfected the art of squeezing costs out of physical supply chains. Sears had ruled the catalog business for a century. Shopping malls were cultural institutions. The idea that people would type a credit card number into a computer screen and wait days for a box to arrive seemed, to most observers, absurd.

Jeff Bezos did not think it was absurd. He was working at D.E. Shaw, a quantitative hedge fund in Manhattan run by the brilliant and secretive David Shaw. Bezos was the youngest senior vice president in the firm's history, and Shaw had tasked him with exploring business opportunities on the internet, which was growing at roughly 2,300 percent per year. Bezos compiled a list of twenty product categories that could be sold online. Books rose to the top for reasons that were almost mathematical: there were over three million titles in print, far more than any physical bookstore could stock. Books were uniform in shape, easy to ship, and relatively inexpensive. Most importantly, customers already knew exactly which book they wanted before they bought it, which meant the browsing experience could be replicated digitally.

When Bezos told Shaw he was leaving to sell books on the internet, Shaw took him on a long walk through Central Park. "That's actually a really good idea," Shaw reportedly told him, "but it would be an even better idea for someone who didn't already have a good job." Bezos went home and applied what he later called the "regret minimization framework." He imagined himself at eighty years old, looking back. Would he regret leaving a lucrative Wall Street career to try this? No. Would he regret not trying? Absolutely. The framework was characteristically Bezos: analytical, long-term, and slightly theatrical.

He and MacKenzie Scott, his wife at the time and a Princeton-educated novelist, drove to Seattle. The city was chosen for its proximity to a major book distributor in Oregon and for Washington state's small population, which minimized sales tax obligations. They set up in a converted garage, where the first desks were literally doors bought from Home Depot and mounted on four-by-fours. It was not an aesthetic choice born of Silicon Valley affectation. Bezos was genuinely frugal, and the door desks became a lasting symbol of the company's cost-consciousness.

Raising money proved difficult. Bezos pitched sixty investors and closed twenty-two of them, raising about a million dollars at a roughly five million dollar valuation. His parents, Mike and Jackie Bezos, invested approximately three hundred thousand dollars of their retirement savings. Mike Bezos later said he was not investing in the internet. He was investing in his son. It was the kind of concentrated bet that, had Amazon failed, would have been a devastating family loss. Instead, that three hundred thousand dollars grew into a stake worth billions.

The Early Years: Survival Mode (1995–2001)

Amazon launched on July 16, 1995, operating out of the Bezos garage. The team had rigged a bell to ring every time someone placed an order. Within the first week, the bell was ringing so often they had to turn it off. In its first thirty days, Amazon shipped books to all fifty states and forty-five countries. There was no advertising budget. Word of mouth and the sheer novelty of buying a book online drove the early traffic.

The early technical infrastructure was held together with duct tape and determination. Servers crashed regularly. The packing tables were the floor. Bezos and his small team would kneel on concrete to pack boxes, and one early employee famously suggested they get knee pads. Bezos replied that what they actually needed was packing tables, a moment that became company lore about solving the right problem rather than patching symptoms.

Amazon went public on May 15, 1997, at eighteen dollars per share, raising fifty-four million dollars. The IPO prospectus was notable for its candor. Bezos wrote the first of his famous annual shareholder letters that year, declaring that "it's all about the long term." He warned investors that the company would prioritize market share and cash flow over quarterly profits, that it would make bold rather than timid investment decisions, and that some of those decisions would not pay off. Wall Street was initially enthusiastic, then increasingly skeptical.

The company expanded aggressively beyond books into music, DVDs, electronics, and toys. The internal motto was "Get Big Fast," which was literally printed on employee badges. Revenue climbed from just under sixteen million dollars in 1996 to over a billion dollars by 1999. But losses were mounting even faster. Amazon was burning cash building warehouses, hiring engineers, and subsidizing free shipping promotions.

Then the dot-com bubble burst. Between its peak in late 1999 and its trough in late 2001, Amazon's stock fell roughly ninety-five percent, bottoming near six dollars per share. Barron's ran a cover story titled "Amazon.bomb." Lehman Brothers analyst Ravi Suria issued a series of reports arguing the company would run out of cash. Bezos kept the Barron's cover framed on his office wall.

What saved Amazon was a pivotal decision to focus relentlessly on free cash flow rather than reported earnings. Bezos and CFO Warren Jenson restructured the company's capital, negotiated better terms with suppliers, and slashed unprofitable initiatives. Amazon turned its first quarterly profit in Q4 2001, earning just five million dollars on over a billion in revenue. It was a rounding error financially but an earthquake psychologically. The company that everyone had written off was alive, generating cash, and ready for what came next.

The Platform Revolution: Marketplace and Prime (2002–2007)

In the early 2000s, Bezos made a decision that horrified many of his own executives: he opened Amazon's website to third-party sellers. The logic was counterintuitive. Why would Amazon invite competitors to sell right next to its own products, sometimes at lower prices? The answer lay in what Bezos called the flywheel. More sellers meant more selection. More selection attracted more customers. More customers attracted more sellers. The cycle would accelerate continuously, and Amazon would take a cut of every transaction.

The internal resistance was fierce. Retail executives who had spent years negotiating supplier deals saw their hard-won margins being undercut by garage sellers on the same product page. Bezos overruled them. He argued that if Amazon did not cannibalize its own business, someone else would. The numbers eventually vindicated him. Third-party sellers grew from a negligible share of Amazon's merchandise to more than sixty percent of all units sold on the platform. Amazon collected fees on every transaction without bearing inventory risk, transforming its economics.

The second major platform bet was Amazon Prime, launched in February 2005. The idea came from a lower-level employee named Charlie Ward, who proposed an all-you-can-eat annual shipping subscription. The finance team modeled it out and concluded it would lose money. The shipping costs alone, they argued, would overwhelm the seventy-nine dollar annual fee if customers actually used it. Bezos loved the idea precisely because of that risk. He believed that once customers paid for unlimited free shipping, they would consolidate their purchasing on Amazon, dramatically increasing lifetime value.

He was right, but the initial losses were staggering. Heavy Prime users were ordering so frequently that shipping costs far exceeded their subscription fees. What the models had underestimated was the behavioral shift. Prime members did not just buy more from Amazon. They stopped shopping elsewhere almost entirely. Prime became the most successful loyalty program in retail history, eventually growing to over two hundred million members worldwide. Each member spent roughly two to three times more annually than non-Prime customers.

Behind the scenes, Amazon was building Fulfillment by Amazon, known as FBA. This service allowed third-party sellers to ship their inventory to Amazon's warehouses, where Amazon would store, pick, pack, and ship orders on their behalf. FBA solved two problems simultaneously. It gave small sellers access to Amazon's logistics infrastructure, making their products Prime-eligible. And it filled Amazon's warehouses more efficiently, improving utilization rates and spreading fixed costs across a larger volume. FBA transformed Amazon from an online retailer into a logistics platform, a distinction whose full implications would take years to unfold.

AWS: The Accidental Empire (2002–2010)

The story of Amazon Web Services begins not with a grand strategic vision but with frustration. In the early 2000s, Amazon's engineering teams were spending months on projects that should have taken weeks. The problem was infrastructure. Every time a team wanted to build a new feature, they had to provision servers, configure databases, and manage networking, all from scratch. The internal technology stack was a tangle of monolithic systems that resisted change.

In 2003, Bezos issued a mandate that became legendary in software engineering circles. Every team at Amazon had to expose its data and functionality through service interfaces. There would be no other form of communication between teams: no direct database access, no shared memory, no back doors. Every interface had to be designed from the ground up to be externalizable. In other words, every internal service had to be built as if outside developers might use it someday. The mandate was enforced with the threat of termination. It was brutal, disruptive, and transformative.

Andy Jassy, a Harvard MBA who had been Bezos's shadow, or technical advisor, took charge of a skunkworks project to build standardized infrastructure services. The key insight was what Bezos called "primitives," basic building blocks of computing that could be combined in any way a developer needed. Storage became S3, launched in March 2006. Compute became EC2, launched in August 2006. These were not products in the traditional sense. They were raw capabilities, priced by the hour or the gigabyte, available to anyone with a credit card.

The launch was met with near-total indifference from the enterprise technology world. Established players like IBM, Oracle, and Sun Microsystems dismissed it as a toy for hobbyists. They could not imagine serious businesses running on shared infrastructure managed by a bookstore. But startups saw it immediately. A two-person team could now spin up server capacity that previously required a million-dollar capital expenditure. Dropbox was built on S3. Netflix migrated its entire streaming infrastructure to AWS. Instagram ran on AWS when it was acquired by Facebook for a billion dollars with just thirteen employees.

The strategic implications were enormous. AWS gave Amazon a seven-year head start on Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud Platform, both of which launched meaningful competitors only around 2010 and 2012 respectively. By the time the enterprise world realized that cloud computing was not a fad but a fundamental shift, AWS had already built the deepest feature set, the largest customer base, and the most mature operational practices in the industry.

Think of AWS as a utility company for computing. Just as you do not build your own power plant to run a factory, AWS argued that you should not build your own data centers to run software. The analogy was simple, but the execution was phenomenally complex. AWS had to guarantee near-perfect uptime, handle security at massive scale, and continuously lower prices even as demand exploded. By 2025, AWS was generating over one hundred thirty billion dollars in annualized revenue with operating margins consistently above thirty percent. It had become, by some measures, the most valuable business unit inside any company in the world.

The Kindle and Digital Transformation (2007–2013)

Jeff Bezos watched Steve Jobs unveil the iPod in 2001 and felt something close to dread. The iPod did not just sell hardware. It pulled an entire industry, music, into Apple's ecosystem. If Apple or someone else did the same thing with books, Amazon's core business would be disintermediated. The company that owned the reading device would own the customer relationship, and Amazon would be reduced to a commodity supplier.

Bezos decided Amazon had to build its own reading device, even though the company had zero hardware experience. He established Lab126, a secret hardware division in Cupertino, California, practically in Apple's backyard. The name was a reference to the letters A and Z, the first and twenty-sixth letters of the alphabet, bookending the company's ambition. The team was led by Gregg Zehr, a former Palm engineer, and operated with unusual autonomy.

The first Kindle launched on November 19, 2007, priced at three hundred and ninety-nine dollars. It sold out in five and a half hours. The device itself was ungainly by modern standards, with a keyboard, an odd angular design, and an e-ink screen that could not display color. But it had one killer feature: built-in free cellular connectivity. Readers could buy and download a book in under sixty seconds, anywhere, without connecting to Wi-Fi or a computer. Bezos understood that reducing friction to zero was more important than industrial design.

The real disruption was the pricing. Amazon sold most Kindle bestsellers at nine dollars and ninety-nine cents, often below what it paid publishers. This was classic Bezos: lose money on the transaction to win the customer relationship. Publishers were furious. They saw Amazon using predatory pricing to establish a monopoly on ebook distribution. The conflict escalated when five major publishers conspired with Apple to impose an "agency model" that would let publishers set their own prices. The Department of Justice investigated and ultimately sued Apple and the publishers for price-fixing in 2012. Apple was found liable; the publishers settled. It was a strange outcome: Amazon, the alleged bully, emerged as the beneficiary of an antitrust action.

The Kindle also spawned Kindle Direct Publishing, which allowed any author to publish and sell ebooks directly on Amazon. KDP democratized publishing in ways that traditional houses found deeply threatening. Self-published authors could earn seventy percent royalties compared to the industry-standard fifteen percent from traditional publishers. Within a few years, KDP authors were dominating certain genre categories, and a handful of self-published writers were earning millions annually. The Kindle was never just a device. It was a platform that restructured the economics of an entire creative industry.

Logistics Innovation and the Physical World (2010–2020)

In 2012, Amazon paid seven hundred and seventy-five million dollars to acquire Kiva Systems, a robotics company that made small orange warehouse robots capable of lifting shelving units and carrying them to human pickers. At the time, the acquisition seemed expensive for a company that made warehouse equipment. In retrospect, it was one of the most consequential acquisitions in Amazon's history.

Kiva robots, rebranded as Amazon Robotics, transformed fulfillment center operations. Instead of workers walking miles per shift through vast warehouses to find items, the shelves came to them. This cut the time required to process an order from over an hour to roughly fifteen minutes. Amazon deployed hundreds of thousands of robots across its fulfillment network, and crucially, it pulled Kiva's products off the market, denying competitors access to the same technology.

The broader logistics build-out was staggering in scale. Amazon constructed over a thousand facilities globally, including massive fulfillment centers, sortation centers, delivery stations, and air hubs. The company leased a fleet of cargo aircraft under the Amazon Air brand, beginning in 2016. It built a 1.5-million-square-foot air hub at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. It began contracting its own ocean freight capacity. Step by step, Amazon was replacing its dependence on UPS, FedEx, and the United States Postal Service with a proprietary logistics network.

The motivation was both economic and strategic. Shipping costs were Amazon's single largest expense category, running into the tens of billions annually. Every dollar saved on logistics dropped directly to the bottom line. But the deeper game was control. Owning the delivery network meant Amazon could guarantee delivery speeds that no third-party carrier would match. Prime Now, launched in 2014, offered one-hour delivery in select cities. Same-day delivery expanded to cover most major metropolitan areas. Each acceleration of delivery speed raised customer expectations, which in turn made it harder for competitors without similar infrastructure to keep up.

Amazon's physical retail experiments were more mixed. The acquisition of Whole Foods in 2017 for thirteen point seven billion dollars gave Amazon nearly five hundred upscale grocery stores overnight. Amazon Go, the cashierless convenience store concept launched in 2018, was a technical marvel: computer vision and sensor fusion allowed customers to grab items and walk out, with charges applied automatically. But Go stores never achieved the scale that would have justified their enormous per-store technology investment, and Amazon quietly scaled back the concept. The lesson was instructive: Amazon's logistics dominance did not automatically translate into physical retail success.

For investors, the key insight was that Amazon was spending over ten billion dollars per year on logistics research and capital expenditure, building an asset that would be nearly impossible for any competitor to replicate. The fulfillment network was not just a cost center. It was becoming a revenue-generating platform through services like FBA, Amazon Shipping, and Supply Chain by Amazon, which offered end-to-end logistics to third-party sellers from factory to doorstep.

The Platform Economy and Advertising Emergence (2015–Present)

Sometime around 2015, Amazon quietly became one of the largest advertising companies in the world. The shift happened almost by accident. Brands selling on Amazon's marketplace were desperate for visibility among millions of competing listings. Amazon began offering sponsored product placements, display ads, and eventually video advertising. The business grew from negligible revenue to roughly fifty billion dollars annually by 2024, making it the third-largest digital advertising platform behind Google and Meta.

The beauty of Amazon's advertising business lies in its margins and its data. Unlike Google or Meta, where advertising intent must be inferred from searches or social behavior, Amazon knows exactly what customers are buying. An ad shown to someone actively browsing for running shoes converts at rates that search and social ads cannot match. Advertising revenue flows at margins estimated above fifty percent, making it one of the most profitable segments inside the company, even more profitable per dollar than AWS.

Alexa, Amazon's voice assistant launched in 2014 inside the Echo smart speaker, represented a very different kind of bet. Bezos envisioned voice as the next major computing interface, and he invested billions in building Alexa's capabilities. The Echo became a cultural phenomenon, selling over a hundred million units. But the business model never materialized as hoped. People used Alexa to set timers, play music, and check the weather. They did not use it to shop. By the mid-2020s, the Alexa division was reportedly losing billions per year, and Amazon undertook significant restructuring of the team. The device was a consumer hit but a commercial disappointment, a rare example of Amazon investing heavily in a platform that failed to generate sustainable economics.

Internationally, Amazon invested aggressively in India, pouring billions into the market to compete with Flipkart, which Walmart acquired in 2018 for roughly sixteen billion dollars. India represented the last major e-commerce market without an entrenched dominant player, and Amazon saw it as a once-in-a-generation opportunity. In China, however, Amazon retreated. Its marketplace never gained traction against Alibaba and JD.com, and Amazon shut down its Chinese marketplace operations in 2019. The China failure was a humbling reminder that Amazon's playbook was not universally exportable.

The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 compressed what might have been a decade of e-commerce adoption into a matter of weeks. Amazon's revenue surged from two hundred and eighty billion dollars in 2019 to three hundred and eighty-six billion in 2020. The company hired over four hundred thousand workers in a single year. But the pandemic also exposed vulnerabilities: supply chain disruptions, warehouse safety controversies, and the challenge of managing a workforce that had grown faster than any organization in peacetime history.

Culture, Leadership, and the Bezos Doctrine

Amazon's internal culture is unlike anything else in corporate America, and understanding it is essential to understanding the company's performance. The cornerstone is what Bezos called the "Day 1" mentality. Day 2, he wrote in his 2016 shareholder letter, is stasis, followed by irrelevance, followed by excruciating decline, followed by death. The antidote is to treat every day as if the company were still a startup: customer-obsessed, skeptical of proxies, eager to adopt external trends, and willing to make high-velocity decisions.

Amazon codified its culture into fourteen Leadership Principles that govern hiring, promotion, and decision-making. These are not the vague platitudes that adorn most corporate walls. They are operational mandates. "Customer Obsession" comes first: leaders start with the customer and work backwards. "Bias for Action" means speed matters, and most decisions are reversible, so perfectionism is the enemy. "Have Backbone; Disagree and Commit" means employees are expected to challenge ideas they find flawed, even if doing so is uncomfortable, but then commit fully once a decision is made.

The "two-pizza team" concept dictated that no team should be larger than what two pizzas could feed, roughly six to ten people. This kept teams small, autonomous, and accountable. Combined with the service-oriented architecture mandate from the early 2000s, it meant Amazon operated less like a single company and more like thousands of small startups sharing a common infrastructure.

Amazon's memo culture is legendary. PowerPoint presentations are banned in senior meetings. Instead, teams write six-page narrative documents that are read in silence at the start of every meeting. The practice forces clarity of thought: you cannot hide behind bullet points and animations when you must write complete sentences and paragraphs. Bezos believed this produced better decisions because it required authors to think through their logic fully before presenting it.

The "Working Backwards" process extended this philosophy. Before building a new product, teams wrote a mock press release and a frequently asked questions document describing the finished product as if it already existed. If the press release was not compelling, the product was not worth building. This inverted the typical corporate process, which starts with technology capabilities and searches for applications. Amazon started with the customer experience and worked backwards to the technology.

The cultural controversies are equally important. Investigative reporting, particularly from The New York Times in 2015, painted a picture of a relentlessly demanding workplace where employees were encouraged to critique each other, where work-life balance was seen as a weakness, and where the pressure to perform was crushing. Warehouse conditions drew even harsher scrutiny: reports of workers urged to meet punishing productivity quotas, injuries at rates above industry averages, and inadequate climate control in extreme heat. Amazon has contested many of these characterizations and invested billions in warehouse safety and worker wages, but the reputational damage has been real and ongoing.

Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

The most enduring business framework to emerge from Amazon is the flywheel, a concept Bezos reportedly sketched on a napkin in the early 2000s. Lower prices drive more customer visits. More visits attract more sellers. More sellers increase selection. Greater selection improves customer experience. Better experience drives more visits. The cycle compounds over time, and each revolution of the flywheel makes the next one easier. What makes the flywheel powerful is that every element reinforces every other element. Competitors cannot attack one piece without confronting the entire system.

Amazon's approach to capital allocation is the second major lesson. For nearly two decades after its IPO, Amazon reported minimal profits. Critics called it a charity, a nonprofit run for the benefit of consumers. In reality, Amazon was generating enormous free cash flow and reinvesting virtually all of it into growth. Bezos understood that in a winner-take-most market, the rational strategy is to invest every available dollar into building scale advantages before competitors can respond. The willingness to sacrifice near-term earnings for long-term market position was not recklessness. It was a deliberate strategy enabled by a shareholder base that Bezos had carefully cultivated to think in decades rather than quarters.

The third lesson is the power of optionality. AWS was not in Amazon's original business plan. It emerged from solving an internal problem and recognizing that the solution had external value. Prime started as a shipping convenience and evolved into a media platform, a grocery delivery service, and a pharmacy benefit. The common thread is that Amazon builds capabilities first and finds applications later, a posture that generates options whose value only becomes apparent over time.

Perhaps the most underappreciated lesson is Amazon's approach to failure. The Fire Phone, launched in 2014 at full flagship pricing with a gimmicky 3D display, was a disaster. Amazon took a one hundred and seventy million dollar writedown and discontinued the product within a year. But the team and technology behind the Fire Phone were redirected into building Alexa and the Echo, which became one of the most successful consumer electronics launches of the decade. Bezos repeatedly argued that a company's willingness to fail is directly proportional to its ability to innovate. If the cost of failure is career-ending, employees will only pursue safe bets. If failure is treated as a learning investment, the range of experiments expands dramatically.

Analysis: Bear vs. Bull Case

Amazon's competitive position is best understood through the lens of structural advantages and emerging threats. Using Michael Porter's Five Forces framework, the picture is nuanced. Supplier power is low: Amazon's scale gives it enormous negotiating leverage with manufacturers and content providers. Buyer power is moderate: individual consumers have little bargaining power, but large enterprise AWS customers can and do negotiate aggressively. The threat of new entrants is low in established segments like e-commerce logistics and cloud computing, where the capital requirements are measured in tens of billions of dollars. The threat of substitutes is moderate: social commerce through platforms like TikTok Shop represents a genuine alternative discovery and purchasing channel. Competitive rivalry is intense across every segment: Walmart in retail, Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud in cloud computing, and Google and Meta in advertising.

Through the lens of Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers framework, Amazon's most formidable power is scale economies. Its fulfillment network, AWS infrastructure, and advertising platform all exhibit declining unit costs as volume grows. Network effects operate in the marketplace, where more buyers attract more sellers and vice versa. Switching costs are meaningful in AWS, where customers build deeply integrated architectures that are expensive to migrate. Counter-positioning was critical in AWS's early years: established enterprise IT vendors could not offer cheap, self-service cloud computing without cannibalizing their lucrative on-premise businesses.

The bear case centers on several interconnected risks. Regulatory exposure is the most visible. The FTC's antitrust lawsuit, alleging that Amazon maintained monopoly power through practices that raised rivals' costs and deterred discounting, is scheduled for a bench trial beginning in early 2027. Separately, Amazon settled an FTC dark patterns case in September 2025 for two and a half billion dollars related to deceptive Prime enrollment and cancellation practices. The European Union has pursued its own investigations into Amazon's use of third-party seller data. A materially adverse antitrust ruling could force structural changes to the marketplace model.

AWS faces intensifying competition. Microsoft Azure has been growing faster in percentage terms, fueled by its integration with OpenAI's models and its enterprise sales relationships. Google Cloud turned profitable and is investing heavily in AI infrastructure. Amazon has responded with its custom Trainium chips and the Bedrock platform for generative AI, but the risk is that the AI era reshuffles cloud market share in ways that the previous decade of workload migration did not.

The bull case is equally compelling. Amazon's advertising business continues to grow at over twenty percent annually with margins that improve the company's overall profitability profile. Healthcare, through Amazon Pharmacy and the One Medical acquisition, represents a trillion-dollar addressable market where Amazon's logistics and technology advantages could be transformative. Logistics-as-a-service, where Amazon sells its delivery capabilities to non-marketplace merchants, is an emerging revenue stream with enormous potential.

The Jassy era poses a leadership question. Andy Jassy, who succeeded Bezos as CEO in July 2021, has proven himself operationally by leading the most successful business unit in company history. His early tenure focused on cost discipline, reducing headcount, and improving margins after the post-pandemic hiring surge. Whether he can match Bezos's ability to identify and incubate transformative new businesses remains an open question.

For tracking Amazon's ongoing performance, investors should focus on two key metrics. First, AWS revenue growth rate, because it reflects both the health of cloud computing adoption broadly and Amazon's competitive position specifically. In Q3 2025, AWS grew at 20.2 percent year over year, re-accelerating to its fastest pace since 2022. Second, operating income margin for the overall company, which reveals whether Amazon's high-margin businesses like advertising and AWS are successfully offsetting lower-margin retail operations. The trajectory of this margin tells you whether Amazon is a retail company that happens to have a cloud division, or a high-margin technology platform that happens to sell physical goods.

Epilogue: The Next Chapters

Amazon's next S-curves are beginning to take shape. Healthcare is the most ambitious. The One Medical acquisition, completed in 2023 for roughly three point nine billion dollars, gave Amazon a network of primary care clinics. Combined with Amazon Pharmacy and the company's logistics infrastructure, the pieces exist for a vertically integrated healthcare experience. Whether Amazon can navigate the regulatory complexity and institutional inertia of American healthcare remains to be seen.

Artificial intelligence represents both opportunity and existential uncertainty. Amazon has committed to investing over one hundred billion dollars annually in capital expenditure, with the vast majority directed toward AI and cloud infrastructure. Its custom Trainium chips are designed to reduce dependency on Nvidia and lower the cost of training and running AI models. Project Rainier, a massive compute cluster of hundreds of thousands of Trainium chips, is among the largest AI training installations in the world. The question is whether Amazon's AI capabilities will be competitive with those of Microsoft and OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and the growing ecosystem of open-source alternatives.

Internationally, India remains the highest-stakes battleground. Amazon has invested billions into the market and competes fiercely with Flipkart and the rising Reliance JioMart. Southeast Asia and Latin America offer additional growth vectors, but each market presents unique challenges in logistics infrastructure, regulatory frameworks, and local competition.

If one were advising Amazon's leadership, the obvious areas to double down on would be AI infrastructure and logistics-as-a-service, the two capabilities most likely to generate durable competitive advantages in the coming decade. The most difficult question would be what to kill: Alexa in its current form consumes billions in investment with no clear path to returns, and the physical retail experiments beyond Whole Foods have yet to demonstrate scalable economics.

Amazon began as a bet that the internet would transform commerce. It evolved into a bet that infrastructure, whether for shipping packages or running code, could be offered as a service to the world. The company's impact on how people buy, how businesses operate, and how software gets built is difficult to overstate. Whether that impact has been net positive for society, for workers, for small businesses, and for competitive markets, is a question that regulators, journalists, and citizens continue to debate. The company itself shows no signs of slowing down.

Recent Developments

Amazon reported Q3 2025 results on October 30, 2025, delivering net sales of one hundred and eighty point two billion dollars, up thirteen percent year over year. AWS generated thirty-three billion dollars in quarterly revenue, growing at 20.2 percent, its fastest pace since 2022. The advertising segment produced seventeen point six billion dollars, growing twenty-two percent. Operating income reached an all-time high.

On the cost side, Amazon raised its full-year 2025 capital expenditure guidance to one hundred and twenty-five billion dollars, with management signaling that spending would increase further in 2026 to fund AI infrastructure. The company's AWS backlog reached two hundred billion dollars, providing substantial revenue visibility.

In September 2025, Amazon settled an FTC lawsuit over deceptive Prime enrollment and cancellation practices for two and a half billion dollars, including one and a half billion in customer refunds and a one billion dollar civil penalty. The separate, broader FTC antitrust case alleging monopolistic practices in the marketplace business is now scheduled for trial in early 2027.

In January 2026, Amazon announced layoffs affecting approximately sixteen thousand employees, with senior vice president Beth Galetti citing the need to reduce organizational layers and increase ownership. This followed earlier reductions of roughly fourteen thousand positions in October 2025. The company's Q4 2025 earnings are expected on February 5, 2026, with consensus revenue guidance between two hundred and six billion and two hundred and thirteen billion dollars.

Bank of America named Amazon its top mega-cap pick heading into 2026, citing expected profit growth from AI deals, AWS expansion, and adoption of Amazon's custom Trainium AI chips.

Further Reading

Brad Stone's "The Everything Store" (2013) and its sequel "Amazon Unbound" (2021) remain the definitive accounts of Amazon's history and Bezos's leadership. Bezos's annual shareholder letters from 1997 through 2020 are essential primary sources, remarkable for their consistency of vision and clarity of strategic thinking. For AWS specifically, the oral histories collected by the Computer History Museum and published interviews with Andy Jassy provide valuable context on the cloud computing origin story. The FTC's complaint and Amazon's response filings in the ongoing antitrust case offer detailed insight into the marketplace practices under scrutiny.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music