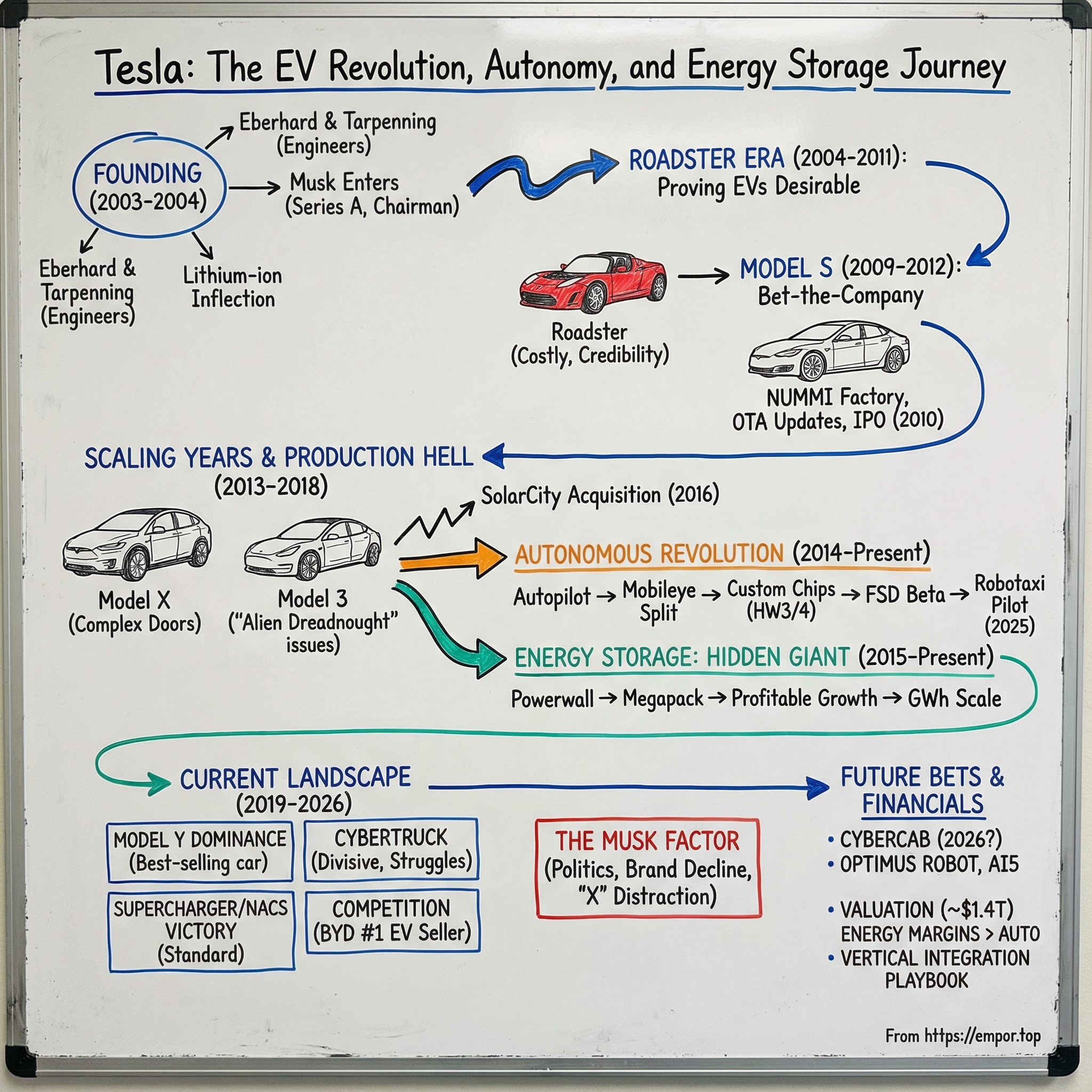

Tesla: The Story of the EV Revolution, Autonomy, and Energy Storage

Introduction

In January 2026, Tesla sits at a market capitalization of roughly $1.4 trillion. It is no longer the world's largest electric vehicle maker by unit sales—that title now belongs to China's BYD. Its vehicle deliveries have declined for two consecutive years. Its brand value has shed more than $15 billion. And yet, the stock trades at multiples that would make any traditional automaker's investor relations team blush. How did a Silicon Valley startup founded in a San Carlos office park become the most valuable automotive company on Earth? And more importantly, does it deserve to be?

The answer requires understanding three businesses wrapped inside one corporate shell: electric vehicles, autonomous driving, and energy storage. Each operates on a different timeline, a different competitive landscape, and a different risk profile. The EV business built the brand and the factories. The autonomy bet is where the trillion-dollar valuation lives. And the energy storage division—quietly, almost stealthily—has become the company's most profitable segment per dollar of revenue.

This is the story of how Tesla got here, what it got right, what it got wrong, and what comes next.

The Founding Story (2003–2004)

The origin myth of Tesla usually starts with Elon Musk, but it shouldn't. It begins with two engineers named Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning, who in the summer of 2003 incorporated Tesla Motors in Delaware. Eberhard was a serial entrepreneur who'd sold his e-book company, NuvoMedia, to Gemstar-TV Guide for $187 million. Tarpenning, his longtime collaborator, handled the business and financial architecture. They were not car guys. They were tech guys who believed the car industry was ripe for disruption.

Their thesis rested on a single insight: lithium-ion battery technology, driven by consumer electronics demand, had crossed an inflection point. The energy density improvements that made laptops and cell phones practical could, if packaged correctly, make an electric car viable—not the golf-cart-like EVs of the 1990s, but something genuinely desirable. They'd been inspired by the AC Propulsion tzero, a stripped-down electric sports car built in a garage in San Dimas, California. The tzero could do zero to sixty in under four seconds using commodity laptop batteries. It was raw, impractical, and utterly thrilling.

Eberhard and Tarpenning reasoned that if you could put that powertrain into a beautiful body, you could create a halo product—a car that would make people want an EV, not settle for one. They would start at the top of the market, where margins were fat and volumes were low, then use profits and scale to work downmarket. It was the classic Silicon Valley playbook applied to Detroit's domain.

Enter Elon Musk. Fresh off the eBay acquisition of PayPal, where his shares netted him roughly $180 million, Musk was looking for ambitious projects. He'd already been thinking about electric cars—and about AC Propulsion. When Eberhard approached him for funding, Musk led the Series A round with $6.5 million of his own money, becoming chairman of the board and the company's largest shareholder. From day one, the arrangement carried tension. Musk didn't write a check and disappear. He had opinions—about the design, the technology, the strategy. This was not a passive investor.

The founding team also included JB Straubel, a Stanford-trained engineer who would become Tesla's chief technology officer and arguably the most important technical mind in the company's history. Straubel had independently been working on electric vehicle concepts and had pitched Musk on an EV project before connecting with Eberhard and Tarpenning. He would spend the next fifteen years architecting Tesla's battery systems, the technological foundation upon which everything else was built.

The early company operated under what might generously be called "first principles thinking"—the Musk-popularized framework of breaking problems down to their fundamental components rather than reasoning by analogy. In practice, this meant ignoring how Detroit said cars should be built. No dealer networks. No model-year refreshes. Software over hardware. The car as a platform, not a product. These ideas would eventually reshape the industry. But first, they nearly destroyed the company.

The Roadster Era: Proving EVs Could Be Desirable (2004–2011)

Tesla's first car started as a partnership with Lotus. The plan seemed elegant: take the lightweight Lotus Elise chassis, swap out the gasoline engine for an electric powertrain, and produce a few thousand units to prove the concept. In reality, almost nothing about the Elise transferred cleanly. The battery pack was too heavy for the original chassis. The crash structure had to be redesigned. The HVAC system, the electronics, the transmission—everything required rework. By the time Tesla was done, only about seven percent of the Roadster's parts came from Lotus.

The engineering was brutally hard, but the business side was worse. The Roadster's original target price of $85,000 kept climbing as costs ballooned. Each car cost far more to produce than it sold for—Tesla was burning cash at a terrifying rate. The company cycled through leadership drama that would make a soap opera writer blush. Eberhard was pushed out as CEO in 2007 after a bitter clash with Musk over the spiraling costs and timeline. A brief interim CEO, Michael Marks, was followed by Ze'ev Drori, who lasted about a year. Then, in October 2008, Musk took over as CEO himself.

His timing was exquisite—and terrible. The global financial crisis had frozen credit markets, cratered consumer confidence, and made fundraising nearly impossible. Tesla came within days of running out of cash on Christmas Eve 2008. Musk personally put in his last $20 million—money he later said he had to borrow—and convinced existing investors to match it. The round closed on the last possible day.

The Roadster, for all its production pain, accomplished exactly what Eberhard and Tarpenning had envisioned: it made electric cars cool. George Clooney drove one. So did Matt Damon, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and half of Silicon Valley. Tesla produced about 2,450 Roadsters between 2008 and 2012, and while the car lost money on nearly every unit, it generated something more valuable than profit—credibility. It proved that an EV could be fast, beautiful, and aspirational. It proved that batteries could power a real car, not just a science project. And it created a customer base of wealthy, influential early adopters who would evangelize the brand.

The Roadster era also established Tesla's relationship with crisis. The company nearly died multiple times—from engineering setbacks, cash shortfalls, and internal politics. This pattern of existential risk followed by last-minute salvation would repeat itself throughout Tesla's history, creating a corporate culture that thrives on urgency and treats survival as a competitive advantage.

Model S: The Bet-the-Company Moment (2009–2012)

In August 2006, while the Roadster was still years from production, Musk published a blog post titled "The Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan (just between you and me)." The plan was disarmingly simple: build a sports car, use that money to build an affordable sports car, use that money to build an even more affordable car. Step two was the Model S.

The Model S represented a fundamentally different ambition. The Roadster was a proof of concept built on someone else's chassis. The Model S would be a ground-up design—a full-size luxury sedan that Tesla would manufacture itself. This required a factory, a supply chain, a service network, and a level of capital expenditure that dwarfed anything the company had attempted.

The factory came from an unlikely source. In 2010, Tesla acquired the former NUMMI plant in Fremont, California—a joint venture between Toyota and General Motors that had closed during the recession. Toyota, which had invested $50 million in Tesla as part of a broader partnership, sold the massive facility for roughly $42 million. A factory that had cost over $1 billion to build was now Tesla's for the price of a mid-rise apartment building in Manhattan. The deal included much of the existing equipment, giving Tesla a manufacturing footprint that would have taken years and billions of dollars to replicate.

The Model S launched in June 2012, and the reviews were rapturous. Motor Trend named it Car of the Year—the first time the award had gone to an electric vehicle. Consumer Reports gave it a 99 out of 100, calling it possibly the best car they had ever tested. The praise wasn't qualified with "for an electric car." It was simply a great car that happened to run on electricity. The 17-inch touchscreen, the over-the-air software updates, the flat battery pack that lowered the center of gravity and created a massive front trunk—these weren't compromises forced by electrification. They were advantages.

Two innovations from the Model S era deserve particular attention because they transformed the automotive industry. The first was over-the-air software updates. Before Tesla, the idea that a car could improve after purchase was almost unheard of. Tesla pushed updates that added new features, improved performance, and even extended range—turning the Model S into a product that got better over time rather than depreciating from the moment it left the lot. The second was the direct sales model. Tesla sold cars through company-owned stores and online, bypassing the franchise dealer network that had controlled American car sales for a century. This triggered legal battles in dozens of states, with entrenched dealer lobbies fighting to protect their turf. Tesla won some and lost others, but the precedent was set.

The IPO came in June 2010, before the Model S launched, with Tesla raising $226 million at $17 per share. It was the first American car company to go public since Ford in 1956. The stock price has since been split multiple times, and those original shares, if held, would represent a return of roughly 250x—one of the greatest IPO investments of the last two decades.

The Scaling Years: Model X, 3, and Production Hell (2013–2018)

If the Model S proved Tesla could build a great car, the next chapter would test whether it could build a great car company. The Model X, Tesla's first SUV, launched in September 2015 and immediately revealed the tension between Musk's design ambitions and manufacturing reality. The falcon wing doors were engineering marvels—complex double-hinged mechanisms with ultrasonic sensors that could detect ceiling height and adjacent vehicles. They were also a manufacturing nightmare. Each door contained more moving parts than most car companies put in an entire vehicle. Quality problems plagued early production, and the Model X ramp took far longer than planned.

But the Model X was always a sideshow. The main event was the Model 3—the car that would determine whether Tesla could transition from a niche luxury automaker into a mass-market manufacturer. Priced from $35,000, the Model 3 was supposed to bring electric vehicles to the middle class. When reservations opened in March 2016, the response was staggering: 325,000 orders in the first week alone, representing roughly $14 billion in potential revenue. Nothing like it had happened in automotive history.

Then came what Musk would later call "the most excruciating period" of his career. Production hell. Tesla had bet on an extremely automated production line at Fremont—robots doing everything, humans barely involved. The theory was that this "alien dreadnought" would leapfrog traditional manufacturing. The reality was that the robots couldn't handle many assembly tasks reliably. Battery module production at the new Gigafactory in Nevada bottlenecked catastrophically. In the third quarter of 2017, Tesla produced just 260 Model 3s against a target of 1,500.

What followed was a period of corporate crisis management that has entered business school lore. Musk essentially moved into the factory, sleeping on the floor and working twenty-hour days. A tent was erected in the parking lot to house an additional assembly line—a literal canvas structure producing cars in the California sun. Engineers were pulled from other projects and thrown at the problem. The highly automated line was partially de-automated, with humans replacing robots for tasks the machines couldn't master.

During this period, Tesla also completed its controversial acquisition of SolarCity, the solar panel installation company chaired by Musk's cousin, Lyndon Rive. The $2.6 billion all-stock deal in November 2016 was widely criticized as a bailout of a money-losing company with deep ties to Musk. Shareholders later sued, and in 2022, a Delaware court sided with Musk, though the case highlighted governance concerns that persist. The acquisition, however, laid the groundwork for Tesla's energy business, bringing solar panel technology and energy storage expertise under one roof.

By mid-2018, Tesla had clawed its way to producing 5,000 Model 3s per week—the threshold Musk had publicly committed to. The company turned profitable in the third quarter of 2018 and has remained so, with occasional dips, ever since. The Model 3 ramp proved that Tesla could manufacture at scale, but it also exposed the company's tendency to overpromise on timelines and the enormous human cost of Musk's management style.

The Autonomous Revolution and FSD Journey (2014–Present)

In October 2014, Tesla introduced Autopilot—a suite of driver-assistance features including adaptive cruise control and lane keeping. The hardware came from Mobileye, an Israeli company specializing in computer vision for vehicles. The system was impressive for its time, but the relationship soured quickly. Mobileye's leadership grew uncomfortable with how aggressively Tesla marketed the technology, particularly after a fatal crash in May 2016 involving a Model S on Autopilot in Florida. Tesla and Mobileye parted ways.

What followed was one of the most consequential technology bets in automotive history. Rather than partnering with another supplier, Tesla decided to build its own autonomous driving hardware and software stack from scratch. The company hired chip designer Jim Keller—who had previously designed AMD's Zen architecture and Apple's A-series processors—to create a custom AI inference chip optimized for self-driving. The resulting Hardware 3 chip, introduced in 2019, delivered roughly twenty-one times the performance of the Nvidia-based Hardware 2.5 it replaced, at a similar cost. It was a stunning achievement for a car company to design silicon that could compete with the world's leading chipmakers.

Tesla's approach to autonomy differs fundamentally from competitors like Waymo. While Waymo uses lidar, radar, and pre-mapped geofenced areas, Tesla relies exclusively on camera-based computer vision—what the company calls "vision-only." The argument is that humans drive with two eyes and a brain, so a computer with eight cameras and a neural network should be able to do the same. This is either brilliant first-principles reasoning or dangerous hubris, depending on whom you ask.

The technology has evolved through multiple hardware generations—HW1 through HW4, with AI5 expected in mid-2027. Tesla's Full Self-Driving software, sold as a $12,000 option or $199 monthly subscription, has been in supervised beta testing with customers since late 2020. As of early 2026, it requires the driver to remain attentive and ready to take over at all times.

Musk's timeline promises on autonomy have been spectacularly wrong. He predicted a million robotaxis on the road by 2020. Full autonomy by 2021. Revenue-generating unsupervised driving by 2023. Each deadline passed without delivery. "I'm telling you there's a damn wolf this time," Musk said at one point, acknowledging his credibility problem.

But in 2025, something genuinely shifted. Tesla launched a robotaxi pilot program in Austin, Texas, initially with human safety drivers aboard. By January 2026, the company removed the safety monitors entirely—marking the first time Tesla vehicles operated on public roads with no one but the passenger inside. The fleet remains small, with approximately thirty-one active vehicles in Austin and fewer than 150 in the Bay Area. Chase vehicles initially followed the robotaxis but have reportedly been discontinued. The service falls far short of Musk's projections of hundreds of cars in Austin and over a thousand in the Bay Area by end of 2025, but it represents a genuine milestone. Waymo, the current market leader, serves roughly 450,000 paid rides per week across six cities—a gap that underscores how far Tesla still has to go.

Energy Storage: The Hidden Giant (2015–Present)

While the world fixated on Tesla's cars and Musk's tweets, something remarkable happened in the energy division. It became a real business—and arguably the company's best one.

Tesla's energy story began in 2015 with the Powerwall, a home battery that could store solar energy or provide backup power during outages. The Powerpack followed for commercial applications, and eventually the Megapack—a shipping-container-sized unit designed for utility-scale grid storage. Each product generation improved on energy density, cost, and manufacturability.

The inflection came in 2024. Tesla deployed 31.4 gigawatt-hours of energy storage that year, more than doubling the 14.7 GWh from 2023. Revenue from energy generation and storage hit $10.1 billion, up 67 percent from $6 billion the prior year. The gross margin on energy products reached 26.2 percent—meaningfully higher than the automotive segment's 18.4 percent. By 2025, those margins expanded further to over 30 percent. Energy storage has quietly become Tesla's most profitable division per dollar of revenue.

The manufacturing infrastructure tells the scaling story. Tesla operates three Megapack factories—two in Nevada and one in Shanghai—with a combined annual production capacity of approximately 83 GWh. The Shanghai facility, which began production in early 2025, is still ramping toward its designed 40 GWh annual capacity. In late 2025, Tesla introduced the Megablock system, combining four 5 MWh Megapack 3 units into a single 20 MWh solution.

For the first nine months of 2025, energy division revenues grew 27 percent year-over-year, contributing 23 percent of Tesla's total profit while accounting for just 13 percent of revenue. For the full year 2025, energy revenue reached nearly $12.8 billion, up another 27 percent.

Why does this matter for investors? Grid-scale energy storage is growing faster than the EV market, faces less direct consumer brand risk, benefits from government incentives including manufacturing credits worth $756 million to Tesla in 2024 alone, and requires less capital per unit of revenue than car manufacturing. If Tesla's automotive business faces a prolonged sales downturn, energy storage provides a high-margin, fast-growing hedge. It also creates an ecosystem lock-in: utilities that deploy Tesla Megapacks are likely to standardize on Tesla's software and monitoring platform for decades.

The Cybertruck, Model Y Dominance, and Product Evolution (2019–Present)

The Model Y, which began deliveries in early 2020, executed the Tesla playbook flawlessly. Take a proven platform—in this case, the Model 3—add a crossover body that sits higher and offers more cargo space, and price it to own the fastest-growing segment in the auto industry. By 2023, the Model Y was the best-selling car in the world—not the best-selling EV, the best-selling car, period. It outsold the Toyota Corolla, the perennial champion.

In early 2025, Tesla launched the Model Y "Juniper" refresh with updated front and rear design, improved suspension, a rear touchscreen for passengers, and ventilated front seats. The Launch Series variant started at $61,630. Then in October 2025, Tesla unveiled the more affordable Model Y Standard at $39,990, alongside a Model 3 at $36,990. These were not the compact "Model Q" that analysts had speculated about. Instead, Tesla cost-reduced the existing Model Y by removing the panoramic glass roof, using cloth seats, downgrading the headlights, and deleting ambient lighting. It was a pragmatic, if inelegant, approach to affordability—shaving about $5,000 off the previous entry price while maintaining the familiar form factor.

The Cybertruck, by contrast, has been Tesla's most divisive product. Unveiled in November 2019 with a cracked "unbreakable" window and a sub-$40,000 starting price promise, it finally entered production in late 2023 at a starting price of $60,990. The stainless steel exoskeleton and aggressive styling generated fierce opinions—and significant manufacturing challenges. By 2025, the truck was in trouble. Sales plunged 48 percent to just 20,237 units. Used Cybertrucks piled up on dealer lots, with average listing times stretching to 75 days and prices falling 55 percent year-over-year. Tesla reportedly stopped accepting Cybertrucks as trade-ins. SpaceX and xAI began absorbing unsold units for internal fleet use—transactions that conveniently counted as sales on Tesla's books.

The next-generation Roadster, announced years ago as a "technology showcase" with a potential SpaceX cold-gas thruster package, remains in perpetual "coming soon" status. It has become something of a running joke among Tesla watchers—an aspirational halo car that exists primarily in press releases and reservation deposits.

The Supercharger Network and NACS Victory (2012–Present)

If there is one strategic asset that even Tesla's harshest critics acknowledge as brilliant, it is the Supercharger network. Tesla began building it in 2012, when the EV charging landscape was essentially nonexistent. The decision to spend billions on proprietary charging infrastructure—while simultaneously designing and manufacturing cars—seemed like capital allocation madness. It turned out to be a masterstroke.

By January 2026, the Tesla Supercharger network comprises over 35,600 stalls across North America, representing a 52.5 percent share of all DC fast-charging infrastructure. The network maintains a reported 99.95 percent uptime—a reliability figure that the patchwork of third-party CCS chargers cannot approach.

The real victory, however, was not building the network but making it the standard. Beginning in May 2023, automakers began announcing adoption of Tesla's North American Charging Standard, now formalized as SAE J3400. Ford went first, followed by General Motors, Rivian, Volvo, Hyundai, Kia, BMW, Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, Honda, Toyota, and eventually Stellantis in November 2025. As of early 2026, Mitsubishi is the only major holdout. Every other manufacturer has either shipped vehicles with NACS ports or committed to doing so.

This is a profound competitive moat. Tesla's charging connector is now the USB-C of the EV world—the universal standard that everyone else must adopt. Non-Tesla vehicles charging on the Supercharger network generate revenue for Tesla while simultaneously validating its ecosystem. The network effect is powerful: more chargers attract more EV buyers, who create more demand for chargers, which justifies more investment. And Tesla controls the entire stack—the hardware, the software, the billing, and the user experience.

Competition, China, and Global Markets (2018–Present)

For years, Tesla operated in a competitive vacuum. Traditional automakers dismissed electric vehicles as compliance cars—loss leaders built to satisfy California emissions mandates, not to make money. That era is over.

The most formidable challenge comes from China. BYD, backed by Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway since 2008, delivered 2.26 million electric vehicles in 2025—a 28 percent increase that vaulted it past Tesla as the world's largest EV seller. BYD's advantage is ruthless cost efficiency. In Europe, the BYD Dolphin Surf starts at £18,650, less than half the price of a Tesla Model 3. BYD manufactures its own batteries, its own chips, and increasingly its own factory equipment. It is the closest thing to a vertically integrated Tesla equivalent, but with labor costs a fraction of Tesla's and a home market of 1.4 billion people.

Tesla's European sales tell a sobering story. Registrations fell 28 percent in the first eleven months of 2025, with Germany down 48 percent and France down 38 percent. The decline reflects multiple factors: an aging product lineup, the Musk political backlash resonating particularly strongly in Europe, and increasingly competitive offerings from Volkswagen, BMW, and the Chinese entrants.

The Shanghai Gigafactory, which opened in 2019 with record-breaking speed, remains Tesla's most efficient plant and produces roughly half of all Tesla vehicles globally. But it also represents geopolitical exposure. US-China tensions, potential tariffs, and regulatory unpredictability create risk that investors cannot easily quantify. The Berlin Gigafactory, which opened in 2022, has ramped more slowly than Shanghai and faced environmental protests, permitting delays, and production challenges.

The competitive landscape now includes Rivian, which produces compelling trucks and SUVs but struggles with manufacturing scale; Lucid, which makes a technologically impressive sedan but sells in tiny volumes; and the traditional OEMs—Ford, GM, Hyundai, BMW—who are spending tens of billions on electrification. None has yet matched Tesla's combination of software sophistication, charging infrastructure, and manufacturing efficiency. But the gap is narrowing.

The Musk Factor: Leadership, Politics, and Brand (2018–Present)

No analysis of Tesla is complete without grappling with the Elon Musk question. He is simultaneously the company's greatest asset and its most significant risk factor. His vision, engineering intuition, and ability to attract talent are genuine competitive advantages. His management style—demanding, confrontational, prone to public eruptions—has driven extraordinary results and extraordinary turnover.

The inflection point came in October 2022, when Musk completed his $44 billion acquisition of Twitter, rebranding it as X. Running the world's most valuable car company while simultaneously overhauling a social media platform stretched even Musk's famously elastic attention span. But the deeper damage came from Musk's political activities.

During the 2024 election cycle, Musk donated approximately $277 million to support Donald Trump's presidential campaign. After Trump's inauguration in January 2025, Musk assumed a leading role in the Department of Government Efficiency, a cost-cutting initiative that became a lightning rod for controversy. Protests erupted outside Tesla showrooms across the country as part of the "Tesla Takedown" movement. A Morning Consult poll found that 32 percent of US buyers would not consider purchasing a Tesla—a five-percentage-point increase from the prior year.

The brand damage was quantifiable. According to Brand Finance, Tesla's brand value declined $15.4 billion, or 36 percent, in 2025—a third consecutive annual drop. Tesla fell from eighth to ninety-fifth in the Axios Harris poll of America's most visible companies. The partisan split was stark: roughly 70 percent of Republicans viewed Musk favorably, while more than 80 percent of Democrats held unfavorable views. For a company that built its brand on environmental consciousness and attracted a disproportionately progressive customer base, this represented a fundamental realignment.

Musk eventually acknowledged the issue obliquely, stating at the Qatar Economic Forum that he would "spend a lot less" on political campaigns going forward. He purchased approximately $1 billion in Tesla stock in September 2025, a vote of confidence that helped steady the share price. But the question lingers: how much of Tesla's valuation premium depends on Musk, and what happens when the person most responsible for the company's success is also most responsible for its reputational challenges?

Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

Tesla's playbook offers several lessons that transcend the automotive industry. The first is vertical integration as competitive advantage. While the rest of the auto industry outsourced to Tier 1 suppliers, Tesla brought critical capabilities in-house—battery cells, power electronics, software, and eventually silicon design. This created higher upfront costs but enabled faster iteration, better integration, and higher margins at scale. When the semiconductor shortage crippled the auto industry in 2021, Tesla rewrote firmware to work with available chips and kept production running while competitors idled factories.

The second lesson is the software-defined vehicle. Tesla treats the car as a computing platform that happens to have wheels. This enables over-the-air updates, data collection from millions of vehicles for training autonomous driving models, and a recurring revenue stream through subscriptions like FSD and Premium Connectivity. No traditional automaker has successfully replicated this model despite years of trying.

The third is direct distribution. By selling directly to consumers, Tesla captures the entire margin that would otherwise go to dealers, controls the customer experience, and sets prices without negotiation. This model has been partially adopted by Rivian, Lucid, and some traditional OEMs for their EV lines, validating Tesla's approach.

The fourth lesson is harder to replicate: the power of narrative. Tesla's stock has consistently traded at valuations that reflect not current earnings but a vision of the future—autonomous driving, robotics, energy transformation. Musk's ability to articulate that vision and attract believers has provided Tesla with a cost of capital that no traditional automaker can match, enabling investment in long-duration projects that would otherwise be impossible.

The fifth and most sobering lesson is the danger of key-person dependence. Tesla's strategy, culture, capital allocation, and public perception are all inextricably linked to one individual. This creates a fragility that no amount of engineering excellence can fully compensate for.

Financial Analysis and Current State

Tesla's financial picture in early 2026 reflects a company in transition. Full-year 2025 revenue declined to $94.8 billion from $97.7 billion in 2024. Vehicle deliveries fell 8.6 percent to 1.63 million units, marking the second consecutive annual decline and the steepest drop in the company's history as a public company. In Q4 2025, net income plunged 61 percent to $840 million.

The automotive segment tells the story of a maturing business under pressure. Revenue declined as Tesla cut prices to defend market share, compressing margins. The elimination of the $7,500 federal EV tax credit under the new administration removed a significant demand lever, particularly for price-sensitive buyers. The Model Y refresh and the affordable Model Y Standard helped stabilize unit volumes, but the product lineup remains narrow compared to competitors offering dozens of EV models across segments.

The energy business provided the counterpoint. Full-year 2025 energy revenue reached roughly $12.8 billion, up 27 percent, with gross margins exceeding 30 percent. Energy storage contributed 23 percent of Tesla's total profit despite representing just 13 percent of revenue. This margin differential is the most important financial trend at Tesla and one that the market is only beginning to price.

Total gross margin for Q4 2025 exceeded 20.1 percent, the highest level in more than two years, suggesting that the worst of the price-war-driven margin compression may have passed. Tesla ended the year with a substantial cash position, though capital expenditure demands remain heavy as the company builds Megapack factories, prepares for Cybercab production, and invests in AI compute infrastructure.

The valuation debate remains the most contentious in public markets. At $1.4 trillion, Tesla trades at roughly 15 times revenue—a multiple that reflects expectations for autonomous driving, robotics, and energy storage that are years from full realization. As a pure automotive company, the valuation is indefensible. As a platform company with optionality across AI, energy, and transportation, it is at least arguable. The two KPIs that matter most going forward: energy storage gross margin (which reveals the profitability trajectory of Tesla's best business) and FSD miles driven between human interventions (which measures the actual progress toward autonomy that justifies the trillion-dollar premium). These two metrics, tracked quarterly, tell an investor more about Tesla's future value than any earnings-per-share figure.

The Future: AI, Robotics, and Beyond

Tesla's roadmap for 2026 and beyond reads like science fiction, which is both the attraction and the risk. The Cybercab, Tesla's purpose-built robotaxi with no steering wheel or pedals, is scheduled to begin production at Giga Texas in April 2026. Musk has set a target of two million units per year at a price point under $30,000 per vehicle. But Musk himself has tempered expectations, acknowledging that initial production will be "agonizingly slow" given that "almost everything is new." The Cybercab will launch on HW4 hardware, with the next-generation AI5 chip delayed to mid-2027.

The Optimus humanoid robot represents the most speculative bet in Tesla's portfolio. Musk has described a future in which millions of Optimus units perform factory labor, household tasks, and eventually serve as caregivers—a vision that would address the $45 billion industrial robotics market and potentially much more. Pricing targets of $20,000 to $30,000 per unit have been discussed, though production remains in early stages. Low-volume production for use in Tesla's own factories was slated for late 2025, with broader availability tentatively planned for 2026.

The robotaxi network expansion plans are ambitious: beyond Austin and the Bay Area, Tesla intends to launch in Dallas, Houston, Phoenix, Miami, and Las Vegas. Musk has stated a goal of covering roughly a quarter to half of the United States by end of 2026. Whether regulatory approvals, software reliability, and fleet scaling can meet this timeline remains an open question. The Cybercab's lack of manual controls means it cannot operate with a safety driver backup, making regulatory clearance particularly critical.

Through the lens of competitive strategy, Tesla's position reflects several of Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers. The Supercharger network and NACS standard represent network economies—each new user increases the value for all users. Tesla's manufacturing expertise and vertical integration create process power—cost advantages rooted in organizational knowledge that competitors cannot easily replicate. The brand, despite recent damage, retains cornered resource characteristics in the form of billions of miles of real-world driving data feeding FSD neural networks, a dataset no competitor can purchase or replicate. The bear case centers on counter-positioning risk—Tesla's all-in bet on camera-only autonomy may prove inferior to lidar-based approaches, and the company's political entanglements may permanently shrink its addressable market. Key-person dependency on Musk adds execution risk that institutional frameworks struggle to mitigate.

Using Porter's Five Forces: supplier power is moderate and declining as Tesla increasingly manufactures its own components; buyer power is increasing as competition intensifies and Tesla's brand premium erodes; the threat of substitutes is low in EVs but rising in autonomy as Waymo, Cruise, and Chinese players advance; the threat of new entrants is moderate, dampened by massive capital requirements; and competitive rivalry is intensifying rapidly, particularly from BYD, which matches Tesla's vertical integration at lower cost.

Epilogue and Reflections

What Tesla got right was seeing further ahead than anyone else. When Eberhard and Tarpenning founded the company in 2003, lithium-ion battery costs were approximately $1,000 per kilowatt-hour. Today they hover around $100. Tesla bet that the cost curve would bend, and it did. The company bet that software would define the driving experience, and it does. It bet that charging infrastructure would determine EV adoption, and NACS becoming the industry standard validates that thesis completely.

What Tesla got wrong—or at least, what it got wrong repeatedly—was timing. Every major promise has been delivered late, from the Roadster to the Model 3 ramp to Full Self-Driving. The gap between Musk's projections and reality has become a structural feature of Tesla's relationship with investors, creating cycles of hype and disappointment that the stock price absorbs with remarkable resilience.

The cost of being early is real. Tesla spent billions building a charging network before EVs reached mass adoption. It invested in battery manufacturing when lithium-ion cells were expensive and unreliable. It bet on autonomy when the technology was a decade from viability. These investments created lasting competitive advantages, but they also consumed capital, burned out employees, and created expectations the company has struggled to meet.

As Tesla enters 2026, the question is whether the company can execute on multiple simultaneous bets—robotaxis, humanoid robots, energy storage scaling, affordable vehicles—while managing a brand crisis, intensifying competition, and the unique governance challenges of its CEO's extracurricular activities. The next chapter of this story will be written by the interplay between technology delivery and market patience. For now, Tesla remains what it has always been: a company that inspires both the most ambitious bull cases and the most devastating bear cases in public markets—often simultaneously, and often for the same reasons.

Recent Developments

In the final weeks of January 2026, several developments shaped the Tesla narrative. The Q4 and full-year 2025 earnings report, released on January 28, confirmed the second consecutive annual sales decline, with deliveries falling to 1.63 million vehicles. Net income dropped 61 percent in the fourth quarter to $840 million. However, total gross margin reached its highest point in over two years, and the energy storage division delivered another strong quarter, pushing full-year energy revenue to nearly $12.8 billion.

The robotaxi program crossed a significant milestone as Tesla began operating vehicles in Austin without safety monitors or chase cars, transitioning from supervised to fully unsupervised operation. The fleet remains small, but the technological and regulatory precedent is meaningful. Musk reiterated plans to expand to additional cities and to begin Cybercab production in April 2026.

BYD officially surpassed Tesla as the world's largest EV seller for 2025, delivering 2.26 million battery-electric vehicles compared to Tesla's 1.63 million. The gap of over 600,000 units reflected BYD's rapid growth in China, Europe, and emerging markets, while Tesla contended with brand challenges and an aging lineup.

The Model Y Standard, launched at $39,990 in October 2025, began gaining traction as Tesla's most affordable offering, though early sales data suggested that buyers in the sub-$40,000 segment were highly price-sensitive and the elimination of the federal EV tax credit weighed on demand.

Tesla's market capitalization stood at approximately $1.44 trillion, making it the world's tenth most valuable company—a valuation that continues to embed substantial expectations for businesses that remain in early stages of commercialization.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music