Cintas Corporation: From Rags to Fortune 500

Introduction & The Hook

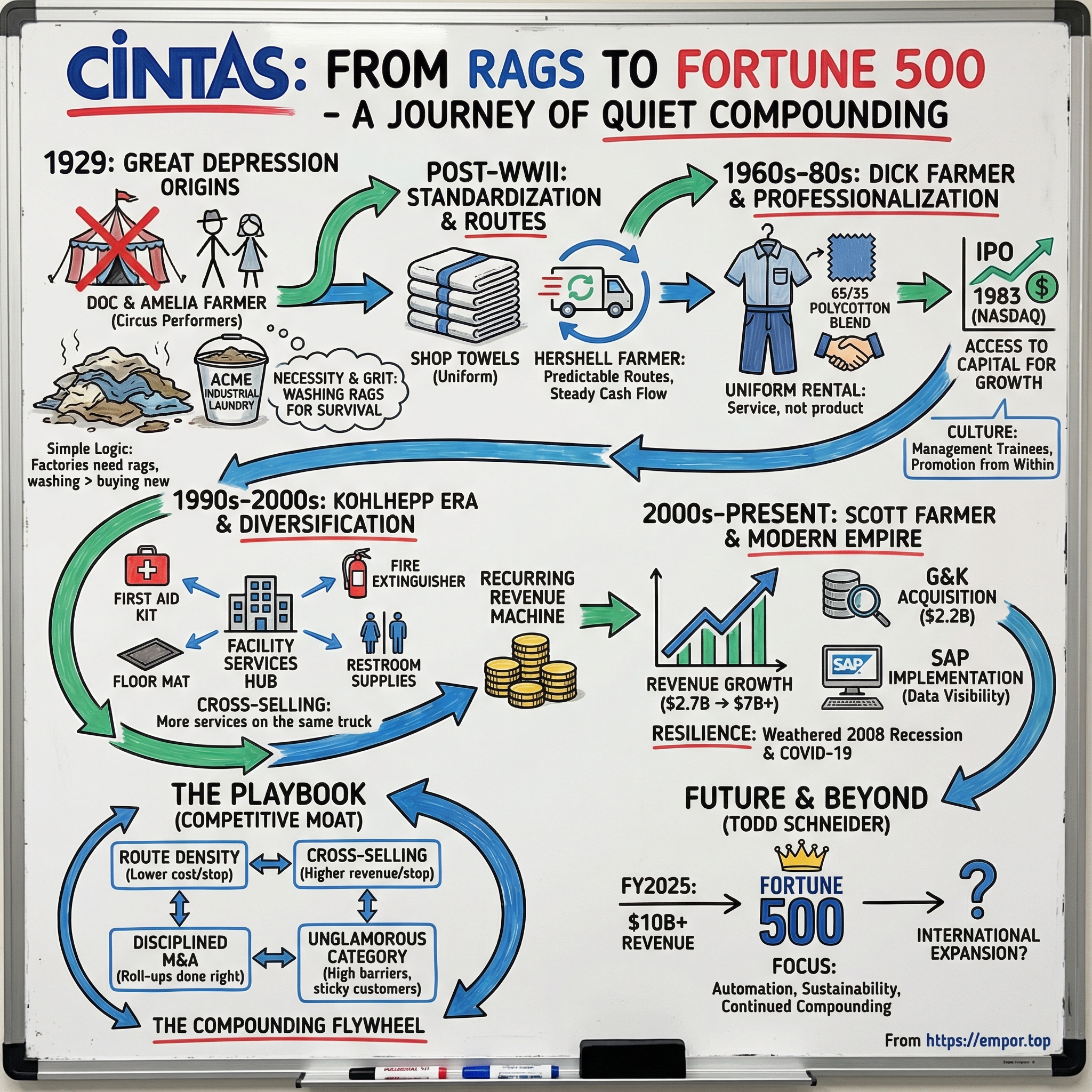

There’s a company headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio that most consumers couldn’t name, yet its fingerprints are all over everyday life. The logo on the technician’s shirt when you get your car serviced. The first-aid cabinet in your office break room. The floor mat at the front door of a neighborhood restaurant. The fire extinguisher that gets inspected, tagged, and put back on the wall like clockwork. With surprising frequency, those details trace back to one enterprise: Cintas Corporation.

In fiscal year 2024, Cintas generated $9.94 billion in revenue, landing it squarely in the Fortune 500. By early 2026, the company was worth roughly $75 billion in the public markets. It traded at a premium multiple, and it produced shareholder returns that would make plenty of household-name tech companies blush. Over the last couple of decades, Cintas has compounded quietly and relentlessly—one of the best-performing large-cap industrials in America, without the hype cycle or the spotlight.

And that’s what makes the story so counterintuitive. Cintas didn’t start with a revolutionary product or a charismatic consumer brand. It started in 1929, the year the market crashed, as the Great Depression began to swallow the country. A husband and wife had just lost their jobs as circus performers. They needed a way to make a living. So they went to factories, collected dirty rags that businesses were throwing away, washed them, and sold them back.

That rag-washing operation—born out of necessity and grit—became a multigenerational family business. It lived through floods, recessions, two world wars, and a global pandemic. Along the way, it evolved into one of the most dominant business-to-business services companies in North America.

The question that makes this worth studying is simple: how did a couple who lost their circus jobs build one of the most powerful B2B service businesses in America?

The answer isn’t glamorous. There’s no breakthrough invention, no venture-capital rocket ship, no viral consumer moment. Instead, it’s route density economics. It’s disciplined capital allocation. It’s relentless cross-selling. It’s the quiet compounding of recurring revenue. It’s choosing the boring path—and getting paid spectacularly for it.

From circus performers to a billion-dollar empire, through family succession, strategic acquisitions, and one of the most unglamorous business models imaginable, this is the Cintas story.

The Great Depression Origins & Doc Farmer's Vision

Picture Cincinnati in 1929. The Ohio River cuts through an industrial city of smokestacks and factory yards—an economy built on making things, moving things, and getting them out the door. The Roaring Twenties are still echoing through the machinery, right up until they aren’t. The stock market crashes, orders dry up, and jobs vanish. In that whiplash moment, Richard “Doc” Farmer and his wife, Amelia, find themselves in the same position as millions of Americans: suddenly unemployed, staring down the Depression, needing a way to survive.

Doc’s nickname didn’t come from a medical degree. It came from personality—showmanship, hustle, and a knack for making something out of nothing. Those traits had served him well as a circus performer traveling across the Midwest. But when the Depression squeezed entertainment budgets and the circus circuit collapsed, the Farmers had to reinvent themselves fast.

They found their next act not under a tent, but behind Cincinnati’s factories.

In the industrial corridors of the city, Doc and Amelia noticed something everyone else ignored: piles of used, grease-soaked rags—thrown out after a single use. To factory owners, they were trash. To Doc, they were raw material. Inventory. A business hiding in plain sight.

The plan was almost absurdly simple. They would collect the discarded rags, take them back, wash them, and sell them right back to the same businesses that had tossed them. In 1929, they named the operation Acme Industrial Laundry Company—an unglamorous name for an equally unglamorous service. There was no funding round, no formal strategy deck, no safety net. Just a couple, a laundering operation, and the willingness to deal with what others didn’t want to touch.

What made it work, even in the worst economy imaginable, was pure logic. Factories needed rags to wipe machinery, handle oil, and clean up messes. New rags cost money. Throwing used ones away was wasteful. The Farmers offered a cheaper, dependable alternative. It wasn’t a flashy breakthrough—it was a practical solution that saved customers money and produced steady income for the family.

And in hindsight, you can see the DNA of Cintas already there: take a recurring, necessary problem that businesses don’t want to think about, and solve it reliably.

Acme grew slowly through the 1930s, surviving because it kept overhead low and served a need that didn’t disappear just because the economy was in trouble. Then, in the late 1930s, a different kind of catastrophe hit. The Ohio River flooded, and the 1938 Cincinnati flood—one of the worst the city had ever seen—destroyed Acme’s plant. Equipment, inventory, the building itself—ruined.

This is the part where most small businesses end.

Instead, the Farmers rebuilt. Doc and Amelia moved operations to a new plant on Duck Creek Road in Norwood, just north of Cincinnati, and started again from scratch. And in the middle of their own recovery, they did something that says a lot about how they saw the world: they provided day jobs to transient workers riding freight trains from town to town, looking for work in the lingering hardship of the Depression. For the Farmers, taking care of people wasn’t separate from building a business. It was part of how the business worked.

After World War II, America’s industrial machine came roaring back. Acme rode that wave, and the next generation pushed the company forward. Hershell Farmer—Doc and Amelia’s son—took over in the 1940s and began modernizing. The big shift was moving away from laundering whatever rags happened to show up and toward standardized industrial towels and shop towels.

It sounds like a small change. It wasn’t.

Rags were inconsistent—different fabrics, sizes, and conditions every time. Shop towels were uniform. They could be handled more efficiently, managed more predictably, and serviced at higher volume. That transition was Acme’s first real step away from scrappy salvage work and toward a repeatable, scalable service business.

Hershell also leaned into something that would become the backbone of the company: routes. Regular pickup and delivery. The same customers on the same schedule. Soiled towels out, clean towels in. A system built on reliability, relationships, and operational discipline—the kind of work that rarely gets celebrated, but quietly creates durable cash flow.

By the time Hershell’s son was ready to step in, Acme wasn’t a giant. But it was stable. It had customers, routes, and a model that could be replicated.

What happened next would take that foundation and turn it into something far bigger than anyone washing rags in 1929 could have imagined.

Dick Farmer's Transformation: From Family Business to Professional Enterprise

In 1957, a 22-year-old named Richard “Dick” Farmer walked into Acme Industrial Laundry with a fresh degree from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio—and a sense that this business could be much bigger than towels and rags. Acme had twelve employees. It served a small cluster of factories around Cincinnati. It was the kind of steady, unpretentious family operation that could’ve stayed small forever.

Dick didn’t want forever. He wanted scale.

In 1959, just two years after he joined, his father Hershell handed him the reins. Dick looked at what Acme already had—laundering capacity, delivery routes, and relationships with industrial customers—and asked a simple question: what else could ride on the same system?

His answer was uniforms.

Those same factories needed their people dressed for work. Most were buying uniforms outright and handling the headache of cleaning and replacement themselves. Others weren’t providing uniforms at all. Dick saw a service they could sell on repeat: rent the uniforms, pick them up on a schedule, launder them, and return them—clean, folded, and ready. It was the towel route model, upgraded into a bigger, stickier category.

By 1964, the shift was no longer an experiment. The company renamed itself Acme Uniform and Towel Supply, making it clear that uniforms weren’t an add-on; they were the future.

And this is where the business changed character. Towels are transactional. Uniforms are operational. Once a company rents uniforms, the provider gets woven into the customer’s day-to-day: sizes, swaps, repairs, new hires, terminations, weekly rhythms. The switching costs become very real. Changing providers isn’t just a purchasing decision—it’s disruption. Dick had found the kind of relationship-based recurring revenue that can compound for decades.

He also wasn’t satisfied with selling uniforms. He wanted to sell better ones.

In the mid-1960s, Dick worked with Celanese Corporation, Graniteville, and Redkap to develop a 65/35 polycotton fabric blend—65% polyester, 35% cotton. It sounds like a small technical tweak, but in industrial laundering it mattered. Pure cotton wrinkled, wore out, and took longer to dry. The blend held its shape, lasted longer through repeated washes, and looked sharper on the job. Workers felt the difference. And Cintas—still Acme at the time—felt it in economics: longer garment life meant fewer replacements and a better business.

Then Dick took the next leap: leaving Cincinnati.

In 1968, he formed a separate entity, the Satellite Corporation, and opened the first location in Cleveland. The structure was intentional. By keeping the expansion effort separate, Dick could push into a new market without putting the core Cincinnati operation at risk. If Cleveland didn’t work, the mothership survived. If it did work, they could bring it together.

Cleveland worked. In 1970, the companies merged, and Acme suddenly had real presence in two major Ohio markets.

In 1972, Dick did something that sounds cosmetic but wasn’t: he renamed the company. “Acme Uniform and Towel Supply” was long, local, and felt like yesterday’s business. According to company lore, the new name—Cintas—was sketched on a napkin. Clean, modern, and non-specific. No rags. No towels. No Cincinnati. Just a brand that could travel.

Around the same time, Dick made another move that helped turn a family business into a professional enterprise: he hired Bob Kohlhepp as the company’s first controller. Kohlhepp brought financial discipline and operational rigor—exactly the kind of adult supervision a fast-growing service business needs. Dick provided the ambition. Kohlhepp made sure it could be executed without breaking the machine.

Together, they built the foundation for what came next: taking this quiet, route-based uniform company and scaling it into something national.

Going Public & Early Expansion Era

By the early 1980s, Cintas had outgrown the comfortable pace of a regional family business. Dick Farmer could see the national opportunity clearly: the uniform rental industry was full of small, local operators—exactly the kind of fragmented landscape where a disciplined consolidator could build a powerhouse. But there was a catch. To buy your way into new cities, you needed capital—more than the business could reliably generate on its own.

Before he ever rang the bell on Wall Street, Dick made a move that would end up being just as important as the IPO. In 1981, Cintas launched its Management Trainee program, a farm system for leadership built the hard way. The pitch to recruits was simple: come learn the business from the ground up. And “ground up” wasn’t a metaphor. Trainees rode routes, worked in plants, handled the unglamorous parts of the operation, and learned what actually made the machine run.

One of the first seven trainees was Scott Farmer—Doc’s great-grandson and Dick’s nephew. And notably, he entered the same way everyone else did. No shortcut into an office. No automatic title. That was a cultural signal: the Farmer name mattered, but it didn’t exempt you from earning credibility. Scott’s arc from trainee to CEO would take decades, and the organization would watch him climb every rung.

Then came the capital.

In 1983, Cintas went public on the NASDAQ. It wasn’t a headline-grabbing IPO—this was a Cincinnati-based uniform and laundry business, not the next Silicon Valley rocket ship. But it gave Cintas something transformational: access to the public markets, and with it, the financial flexibility to accelerate acquisitions. The timing helped, too. The U.S. economy was coming out of the early-’80s recession, businesses were hiring again, and outsourcing “non-core” work—like uniform programs—was becoming an easier sell.

Cintas used that new financial firepower with discipline. In market after market, it bought local uniform rental companies, folded them into its route network, and squeezed out the economics that small operators couldn’t match. Many of these businesses were family-run with aging owners and no clear successor. Cintas showed up as a clean exit—then turned those mom-and-pop routes into pieces of a bigger system.

The biggest early proof point came in 1989 with the purchase of Unitog Company. This wasn’t a tiny tuck-in; Unitog brought real scale and a broader footprint. Integrating it forced Cintas to get good at the hard part of roll-ups: blending operations, aligning cultures, and moving acquired customers onto Cintas’s way of doing things. Those lessons would matter—a lot—because this wouldn’t be the last time Cintas absorbed something large.

Underneath the acquisitions was the real engine: route density.

The math is simple, and brutal. A truck, a driver, and a route cost roughly the same whether you’re making three stops or ten. Every additional customer on an existing route lowers the cost per stop. Lower cost per stop means better margins, and it also means you can price more competitively when needed. Which helps you win more customers. Which improves route density again. It’s a flywheel built out of scheduling, geography, and repetition—and once it starts spinning, it’s extremely hard for smaller competitors to keep up.

During this era, Dick also put words around the culture he wanted to scale. He codified the company’s “Principal Objective,” positioning Cintas as a place built for employee-partners—not just employees. That wasn’t branding fluff. In a route business, the front line is the product. The driver who shows up on time, fixes problems without being asked, and treats the account like it’s his own is the difference between high retention and constant churn. So Cintas invested heavily in training, promoted from within, and pushed ownership thinking deep into the organization.

By the end of the 1980s, the shape of the modern Cintas playbook was visible. Go public to fund growth. Build leaders from the ground up. Buy fragmented competitors. Integrate relentlessly. And stack density on top of density until the economics become self-reinforcing.

Bob Kohlhepp Era & Professional Management

In 1996, Dick Farmer stepped back from the CEO role and became chairman of the board. Day-to-day leadership moved to the person who’d been helping engineer Cintas’s rise for more than two decades: Bob Kohlhepp.

The handoff worked because it wasn’t abrupt. Kohlhepp had joined the company years earlier as its first controller and steadily climbed, learning every lever that made the model work. If Dick was the entrepreneur with the instinct for where to go next, Kohlhepp was the builder—the one who could turn ambition into repeatable execution.

Under Kohlhepp, Cintas began to look less like “a uniform company” and more like a platform for servicing facilities. The groundwork was already forming. In 1995, Cintas expanded its uniform services into Canada with the acquisition of Cadet Uniform Service Ltd, crossing its first international border. With Kohlhepp in the CEO seat, the bigger shift was what happened next: Cintas started adding adjacent services that could ride on the same routes.

In 1997, Cintas entered the first aid and safety business. On paper, that might sound like a leap. In practice, it was the same playbook, applied to a new category.

Think about what Cintas already had: drivers walking into the same customer locations week after week, relationships with the office managers and plant supervisors, and trucks already making the trip. Adding first aid kits, safety supplies, and compliance-related services didn’t require building a new salesforce from scratch or reinventing operations. It meant putting more value on the same stop. And because the most expensive part of the service—the visit to the customer’s door—was already paid for, the incremental economics could be incredibly attractive.

That idea—that the route network wasn’t just a delivery system, but a distribution platform—became the core lens for diversification. New services had to fit the model: serve the same customer base, be deliverable alongside existing routes, and make the overall relationship harder to unwind. If it checked those boxes, it could scale. If it didn’t, Cintas wasn’t interested.

By 2002, the company crossed $2 billion in annual revenue. For a business that had been a twelve-person operation in the late 1950s, the milestone was less about bragging rights and more about what it proved: Cintas had become a machine.

Kohlhepp helped refine that machine into a disciplined acquisition and integration process. Find targets. Evaluate their routes, customers, and density. Buy at valuations that made sense. Then integrate fast—moving operations onto Cintas systems and standards. To many acquired customers, the transition could feel almost invisible on the surface. The same weekly rhythm continued. But behind it was a larger organization with tighter logistics, more services to sell, and more operational consistency.

This era also pushed Cintas toward what it would eventually call “total facility management”—the idea that one provider could handle a long list of non-core needs: uniforms, towels, mats, restroom supplies, first aid, safety, fire protection, document management. For customers, the appeal was obvious: fewer vendors, fewer headaches, more accountability. For Cintas, the value was strategic. The more services a customer bought, the less likely they were to leave. Switching from one uniform provider is a hassle. Switching half a dozen services at once is a project. Each added service made the relationship more embedded—and the moat deeper.

At the center of it all was what Kohlhepp understood better than most: Cintas wasn’t really in the uniform business. Or the first aid business. Or the safety business.

Cintas was in the recurring revenue business.

Nearly everything it offered was structured as an ongoing service—weekly pickups and deliveries, regular restocking, scheduled inspections. Customers didn’t “buy” uniforms; they entered a rental program. They didn’t just purchase first aid supplies; they signed up for replenishment. That subscription-like structure produced visibility and predictability that most industrial companies never get—and it set the stage for the premium valuation Cintas would earn over time.

Scott Farmer's Leadership & Modern Empire Building

When Scott Farmer became CEO in July 2003, he brought something no outside hire could manufacture: four generations of context and two decades of lived experience inside the machine. As Doc Farmer’s great-grandson—and one of the original Management Trainees—Scott had come up the hard way. He’d ridden routes, worked in plants, led sales teams, and learned the culture at the level where it actually gets tested: on Monday morning, when the truck has to leave on time and the customer expects clean uniforms.

So when he took the top job, he wasn’t inheriting a business he needed to “learn.” He was inheriting a system he already knew how to push.

And push it he did. Scott presided over the most important growth stretch in Cintas history. When he stepped into the CEO role, the company generated $2.69 billion in annual revenue. Eighteen years later, when he handed off the job, Cintas had passed $7 billion. That growth came from three compounding engines: winning more customers, disciplined pricing, and acquisitions—done at a pace and scale that reshaped the company.

Even before Scott officially held the CEO title, Cintas was already accelerating. In 2002, it acquired Omni Services, a uniform rental player, along with several first aid companies: Petragon, American First Aid, and Respond Industries. The logic was consistent with everything Cintas had built since the 1960s: expand the route footprint, deepen relationships, and add products that could ride along on existing stops.

That same year, Cintas entered fire protection with the acquisition of Kamp Fire Equipment, a distributor of fire safety products and services. It was a natural extension of the route model. Fire extinguishers need inspections. Emergency lighting needs checks. Systems need maintenance. Those aren’t one-time purchases—they’re recurring visits. And recurring visits are what Cintas is built to do.

The deals kept coming. In 2015, Cintas acquired Zee Medical from McKesson Corporation for approximately $130 million, strengthening its first aid and safety business. Zee brought a large customer base and established routes in a category that had become central to Cintas’s cross-selling strategy. The more services Cintas could reliably deliver to the same customer, the more embedded it became—and the harder it was to replace.

Then came the deal that defined Scott Farmer’s legacy: the 2017 acquisition of G&K Services for $2.2 billion, the largest transaction in Cintas history. G&K, headquartered in Minneapolis, was a major uniform rental competitor with operations across the U.S. and Canada. The impact wasn’t subtle. It added route density in markets where Cintas already had scale, improving unit economics almost immediately. It brought a wave of new customer relationships that could be introduced to the broader Cintas portfolio. And it removed a serious competitor in an industry where scale advantages don’t just accumulate—they compound.

Of course, buying is the easy part. Integrating is where roll-ups go to die.

Cintas had spent decades refining a repeatable playbook: move customers onto Cintas systems, retrain frontline teams, standardize service, and rationalize overlapping routes. But G&K tested that muscle at a level Cintas had never attempted. By most accounts, the integration went smoothly. Within two years the acquired operations were fully absorbed, and the expected synergies were achieved ahead of schedule. That’s not just execution—that’s institutional capability.

Acquisitions were only part of the story. Under Scott, Cintas also modernized its operational core with a comprehensive SAP implementation. For a company tracking uniforms from procurement to sizing to weekly pickup, laundering, repair, and eventual retirement—across millions of garments and thousands of routes—the data problem is enormous. SAP brought visibility and control: better inventory management, more efficient operations, and sharper insight into where to optimize routes and where to cross-sell. In other words, it made the machine run tighter—and it made the sales engine smarter.

Scott also had to lead through two major shocks that could’ve broken a less durable model.

The Great Recession of 2008–2009 hit Cintas where it’s most sensitive: employment. When customers lay off workers, they need fewer uniforms, and Cintas feels it fast. But the company’s recurring relationships and broader service mix added resilience. Customers might shrink their programs, but they rarely ripped them out entirely. Cintas weathered the downturn, and as weaker competitors struggled or disappeared, it emerged positioned to take share.

Then COVID-19 arrived in 2020, and the disruption looked different. Whole categories of customers—restaurants, hotels, factories—shut down temporarily. But the crisis also created urgent demand for other products and services: sanitization supplies, personal protective equipment, temperature screening stations, and enhanced cleaning. Cintas moved quickly, using its distribution network to deliver what customers suddenly couldn’t operate without. In a strange way, the pandemic validated the deeper truth of Cintas: the uniforms were never the whole business. The real asset was the route-based platform—an infrastructure built for frequent, trusted, on-site service that could adapt when the world changed overnight.

The Business Model & Competitive Moat

To understand why Cintas has earned a premium valuation for so long, it helps to stop thinking of it as a “uniform company.” Cintas is a recurring-revenue distribution platform—one that happens to deliver uniforms, first aid supplies, fire protection services, floor mats, and restroom products. That framing matters, because it points you to the real source of its outsized returns: a route-based machine that gets more profitable the more it gets used.

Start with route density—the single most important idea in the entire model.

Picture a Cintas truck pulling out of a processing plant early in the morning. The driver has a set route: a list of customer stops to hit that day. Most of the cost of that route is fixed. The truck costs what it costs. The driver costs what they cost. The trip takes roughly the same time and burns roughly the same fuel whether the driver makes eight stops or fifteen.

But the economics are completely different.

With more customers packed into the same geography, the cost per stop drops, while revenue per route climbs. Every new customer added to an existing route tends to be high-margin revenue, because the expensive infrastructure—plants, trucks, drivers, scheduling—was already there. This is why Cintas cares so much about density, why it buys competitors, and why it works so hard to win “the next account” near accounts it already has. It’s not just growth. It’s margin expansion disguised as growth.

That’s also why scale is such a weapon in this industry. A small regional operator with a few hundred accounts in a metro area just can’t match the unit economics of a giant with thousands of accounts in the same footprint. Cintas can invest more in technology, training, and service consistency, price aggressively when it needs to, and still generate better margins. The math doesn’t negotiate. It rewards the incumbent that already has the dense route network.

Then layer in the part most people underestimate: Cintas doesn’t “sell” uniforms. It rents them.

A typical customer signs a multi-year service agreement. Cintas supplies the garments, delivers them weekly, launders them professionally, repairs them, replaces them, and manages the inventory. The customer isn’t buying a pile of shirts and pants—they’re outsourcing an operational system. The customer gets predictable service and avoids the headache of purchasing, tracking, and maintaining uniforms internally. Cintas gets subscription-like revenue that repeats week after week. And investors get what markets love: visibility, predictability, and cash flows that look a lot steadier than you’d expect from an industrial company.

Now add the accelerant: cross-selling.

A customer might start with uniforms, but Cintas is visiting the location constantly. The route driver builds relationships. Over time, Cintas can add floor mats at the entrance, restroom supplies in the bathrooms, first aid replenishment in the break room, fire extinguisher inspections for compliance. Each add-on increases revenue per stop while barely changing delivery costs, because the truck is already there. And each add-on raises switching costs. Switching one service is annoying. Switching five or six services at once becomes a full-blown project—one most customers would rather avoid.

One stat captures just how much of Cintas’s growth isn’t about stealing share, but about expanding the category: around sixty percent of new business comes from customers who weren’t in a rental program at all. These are companies buying uniforms outright, washing them in-house, or not running a formal program. Cintas is converting non-consumers into subscribers, which is a much bigger opportunity than simply swapping one vendor for another.

The market penetration numbers tell the same story. Cintas estimates it serves about one million of the roughly sixteen million businesses in North America. That’s a small slice of the potential universe, and it’s why—even though Cintas is already enormous—it can still grow like a company with plenty of runway.

The competitive landscape reinforces all of this. The uniform rental industry has three large players—Cintas, Aramark’s uniform division, and UniFirst—and then a long tail of smaller regional operators. New entrants face a brutal setup cost: processing plants, garment inventory, trucks, hiring, training, sales coverage, scheduling systems—long before they can serve routes profitably. And even after they launch, they run into the chicken-and-egg problem at the heart of the model: you need route density to earn good margins, but you need scale and time to build route density.

Finally, customer switching costs make the whole machine even stickier.

Uniform rental isn’t like changing a commodity supplier. Cintas is tracking sizes for employees, managing inventory across lockers and locations, coordinating weekly schedules, handling repairs and replacements, and keeping the program consistent as people get hired, leave, or change roles. Switching means re-measuring employees, reissuing garments, resetting delivery rhythms, and taking on the risk that service reliability drops. For most customers, the disruption isn’t worth whatever modest savings a competitor promises.

That’s the moat in plain terms: dense routes that get cheaper as they grow, recurring contracts that behave like subscriptions, and a widening bundle of services that turns “a uniform vendor” into an embedded operating partner.

Todd Schneider & The Future

In 2021, Scott Farmer retired as CEO, but he didn’t disappear. He stayed on as executive chairman. And his successor wasn’t some outside savior brought in to “shake things up.” It was Todd Schneider—someone Cintas had been growing for the job for decades.

Schneider joined the Management Trainee program straight out of college in 1989, the same internal proving ground that had shaped Scott Farmer a decade earlier. Over the next thirty-two years, he moved through the roles that actually matter in a route-based business: sales management, general management, regional leadership. By 2018, he was Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer. When he became CEO, he wasn’t learning Cintas. He was Cintas.

That choice said a lot about how the board viewed the moment. Cintas could have gone hunting for a CEO with a totally different résumé—someone from big tech, or a sprawling industrial conglomerate. Instead, it picked continuity. Not because the company lacked imagination, but because its leadership believed the playbook still had plenty of runway: keep densifying routes, keep layering on services, keep executing, and keep the culture intact.

So far, the numbers have backed that up. For the twelve months ending May 2025, Cintas generated $10.34 billion in revenue, up 7.75 percent year over year. In fiscal second quarter 2026, reported in December 2025, revenue reached $2.8 billion—up 9.3 percent—with 8.6 percent organic growth. The company also posted gross margin of 50.4 percent, an all-time high, and raised its full-year fiscal 2026 guidance to $11.15 to $11.22 billion in revenue, with earnings per share expected between $4.81 and $4.88. That’s not a company idling. That’s the compounding machine doing what it’s built to do.

Cintas also kept stacking milestones that reinforce just how big it’s become. It has been included on the Fortune 500 list for six consecutive years starting in 2018, and nothing about its trajectory suggests that streak is ending soon.

Capital allocation under Schneider has followed the familiar Cintas rhythm: reinvest in the core, pursue selective acquisitions, and return meaningful cash to shareholders through dividends and repurchases. In March 2025, Cintas paid a quarterly dividend of $158.1 million, a 14.9 percent increase over the prior year’s payout.

Meanwhile, the company has kept pushing the operational edge—the unsexy work that, in this business, creates real separation. Cintas has invested heavily in automation and digital capabilities across its processing plants, where garments are sorted, laundered, inspected, and staged for delivery at massive scale every week. More automation means lower labor intensity and more consistent output. Route optimization software helps tighten delivery schedules, reducing fuel costs and letting drivers cover more stops per day. Customer-facing tools make it easier for businesses to manage accounts online—adjusting orders, tracking deliveries, and getting the kind of transparency modern buyers expect.

Sustainability has also moved from “nice to have” to strategic priority. When your business runs fleets and industrial laundries, environmental impact isn’t abstract. It’s operational reality—and it increasingly matters to customers and regulators. Cintas has invested in water recycling systems at processing plants, a transition to more fuel-efficient vehicles, and waste reduction initiatives aimed at extending garment life and keeping textiles out of landfills.

The most interesting open question, though, may be geography. Cintas still generates the overwhelming majority of its revenue in the United States, with a meaningful but relatively modest presence in Canada. Similar uniform rental and facility-services models exist elsewhere—especially in Europe, where companies like Rentokil Initial and Elis operate at scale—but Cintas has historically been cautious about expanding beyond North America. Whether that caution holds, or gives way to a more ambitious international push under Schneider or whoever follows him, could end up being one of the defining strategic decisions of the next decade.

Playbook: The Cintas Way

Every great compounder runs a playbook. Cintas’s just happens to be built out of trucks, laundry plants, and weekly routines. When you study what it consistently got right—and why competitors keep struggling to copy it—you end up with lessons that apply far beyond uniforms: any recurring-revenue business, any route-based service model, any company trying to allocate capital without getting distracted.

The first lesson is family control paired with professional management. The Farmer family guided Cintas through multiple generations, which gave the company something most public companies don’t have: continuity. But the family didn’t try to do everything themselves. Dick Farmer brought in Bob Kohlhepp and trusted him with real authority. The Management Trainee program created a steady pipeline of people who didn’t share the last name, but could still rise to the top. The result wasn’t a dynasty or a bureaucracy—it was a hybrid: long-term cultural stewardship with professional operators running the machine.

The second lesson is the advantage of being unglamorous. Cintas will never be a social-media darling. No one waits for “uniform rental day” the way they wait for a new phone. And that’s a competitive advantage. Boring industries don’t attract hordes of well-funded copycats. The barriers to entry aren’t clever branding or a nicer UI; they’re physical and expensive—plants, trucks, garment inventory, and the operational know-how to run dense routes week after week. Software can help, but it can’t replace the infrastructure. Quiet categories with steady demand and real barriers tend to produce the kind of cash flow that compounds for decades.

The third lesson is the roll-up strategy—done with discipline. The uniform rental industry was fragmented, and that fragmentation was a gift. But roll-ups are where plenty of companies blow themselves up: they overpay, integrate slowly, lose the culture, and end up with a mess instead of a platform. Cintas built a repeatable acquisition and integration process, kept valuation standards tight, and used its culture to absorb acquired teams rather than getting diluted by them. The G&K Services deal tested this at the highest level, and Cintas executed it cleanly enough to become a modern example of how to integrate at scale.

The fourth lesson is culture as a real competitive edge. Cintas’s employee-partner mindset, its promotion-from-within philosophy, and its training discipline show up where it matters most: at the customer’s door. In this business, the route driver isn’t a back-office function. They are the product. A competitor can match your price, but it’s much harder to match thousands of frontline interactions delivered with consistency, pride, and accountability. Treat your workforce like interchangeable labor, and you get interchangeable service.

The fifth lesson is capital allocation, consistently boring in the best way. Across leadership teams, Cintas kept a clear pattern: invest in the core, buy adjacent capabilities that fit the route model, and return cash to shareholders. It didn’t chase flashy, off-strategy “transformations.” It didn’t lean on the balance sheet for financial theatrics. It stayed focused on returns. That restraint is rare, and it’s a big part of why the company has compounded the way it has.

The sixth lesson is converting one-time transactions into recurring revenue. Cintas didn’t invent subscriptions—but it industrialized them long before software made the concept fashionable. Renting uniforms instead of selling them turned a purchase into a relationship: predictable revenue, high retention, and natural growth as the customer hires more employees. Plenty of modern businesses obsess over metrics like retention and recurring revenue; Cintas built those dynamics into physical operations decades earlier.

The final lesson is density before expansion. Cintas didn’t try to cover the whole map immediately. It dominated locally, expanded methodically, and only pushed outward once a market had enough route density to produce strong unit economics. That patience is the foundation of the model. In route businesses, being everywhere isn’t the goal. Being dense is.

Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

The optimistic thesis for Cintas is built on a few simple, powerful ideas. The biggest is runway. With about one million customers out of roughly sixteen million businesses in North America, Cintas is large—but it’s nowhere close to saturating its market. And because around sixty percent of new business comes from companies that weren’t in a rental program at all, growth isn’t just a share battle. Cintas is converting “do it yourself” customers into recurring-service customers, riding the long-term trend of outsourcing work that no one wants to manage in-house.

Then there’s the easiest kind of growth: selling more to the same stop. The average Cintas customer uses fewer than two of the company’s service lines. That leaves plenty of room to layer on first aid, fire protection, restroom supplies, mats, and other services over time. The beauty is that the economics get better as the bundle gets bigger. The truck is already pulling up. Adding another service line can raise revenue per customer with relatively little incremental cost.

Pricing power is another underappreciated strength. Cintas has repeatedly shown it can pass through higher labor, fuel, and input costs without seeing customers flee. In part, that’s because the service is operationally embedded. Switching isn’t just picking a cheaper vendor; it’s changing routines, deliveries, garment tracking, and compliance schedules. For most customers, the disruption isn’t worth the modest savings.

Put through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, Cintas shows multiple “powers” working at once. Scale economies show up in route density—bigger networks tend to run at structurally better margins than smaller ones. Switching costs are real, because uniforms and compliance services get woven into daily operations. Counter-positioning matters too: a full-service offering is hard for specialists to match without building an entirely different set of capabilities. And process power comes from decades of learning how to integrate acquisitions without breaking service.

Porter’s Five Forces lands in a similar place. New entrants face steep upfront costs—processing capacity, garment inventory, trucks, and the operational know-how to run dense routes. Buyer power is limited because customers are typically small relative to Cintas, and switching is painful. Supplier power is moderate: Cintas has options, and suppliers can’t easily replace a customer of that scale. Substitutes exist—companies can buy uniforms instead of renting—but the convenience and consistency of outsourcing is the point. Rivalry is real, but among the top players it has generally stayed rational.

The Bear Case

The clearest risk is macro sensitivity. Cintas’s revenue ultimately tracks employment at customer sites. When businesses lay people off, they need fewer uniforms and fewer service visits. That dynamic showed up during the Great Recession and again in the early months of COVID-19. The model is resilient, but it’s not immune. A deep, prolonged downturn would hit the top line.

Labor is a second structural pressure point. Cintas employs tens of thousands of route drivers, plant workers, and technicians—jobs that can be made more efficient, but not fully automated. In a tight labor market, wage inflation can squeeze margins. Cintas can offset some of that with pricing and productivity, but labor remains a persistent cost risk.

Valuation is the most immediate investor-facing concern. With a forward price-to-earnings ratio above 38, Cintas is priced for continued excellence—steady growth, solid margins, and clean execution. If growth slows, margins compress, or a major integration stumbles, the stock doesn’t have much room for disappointment. When the market pays a premium, it also sets a premium bar.

Finally, competition could get less cooperative. The failed attempt to acquire UniFirst in early 2025—where Cintas offered $275 per share, a 62 percent premium, and was rebuffed—was a reminder that consolidation isn’t guaranteed. And while the physical barriers to entry are formidable, parts of the customer experience—ordering, billing, and account management—could be vulnerable if competitors bring better technology-enabled workflows to market.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you want a quick dashboard for whether the Cintas machine is still compounding the way it should, two measures do most of the work.

First: organic revenue growth. It strips out acquisitions and currency and gives you the cleanest read on new customer wins, cross-selling, pricing, and retention. Cintas has typically delivered mid-to-high single-digit organic growth; a sustained step down would matter.

Second: gross margin. It reflects how well Cintas is balancing labor, fuel, garment costs, and plant efficiency against its pricing discipline. Gross margin has reached all-time highs above 50 percent. The key question going forward isn’t just whether margins can expand further, but whether Cintas can hold those levels as costs move and competition evolves.

Power Analysis & Lessons

Run Cintas through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework, and you don’t get a company propped up by one lucky advantage. You get a business reinforced by multiple, overlapping moats.

Start with scale economies, because in Cintas’s world, scale isn’t a brag—it’s math. The denser the routes in a given market, the lower the cost to serve each stop. Add customers close together, and the truck drives fewer empty miles, the plant runs fuller, and the cost per delivery drops. Smaller competitors can work harder, they can be friendlier, they can even cut price. But they can’t change the physics. Route density is a structural advantage, and once it’s built, it tends to deepen over time.

Next are switching costs. When Cintas becomes your provider, it isn’t just dropping off clean uniforms. It’s managing sizing for every employee, handling repairs and replacements, keeping weekly schedules consistent, and maintaining the compliance rhythm customers depend on. In some cases, it’s also tied into payroll and documentation workflows. That creates something stronger than a contract: operational lock-in. Even when an agreement is up for renewal, the real barrier to leaving is the disruption of changing the system.

Third is counter-positioning. Cintas isn’t a specialist—it’s a bundled, full-service platform. Uniforms, first aid, fire protection, restroom services, facility supplies: one relationship, one set of routes, one company accountable. Specialists can be excellent at a single thing, but the bundle changes the game. A uniform-only player can’t suddenly become a credible fire protection inspector. A first-aid supplier can’t magically build a uniform plant network. To match Cintas, a competitor usually has to build entirely new business lines, with new capabilities and new infrastructure—and most can’t justify the economics to do it.

Then there’s process power, and it might be the most underappreciated of the group. Cintas has spent decades getting good at the part that breaks most roll-ups: integration. Finding targets, pricing them, converting customers, consolidating routes, standardizing service, retaining frontline talent—Cintas built that muscle through repetition. You can’t buy that capability off the shelf, and you can’t hire it in a single executive. It’s institutional knowledge, earned the hard way, and it’s a real advantage over less practiced acquirers.

The lesson for entrepreneurs is almost annoyingly straightforward: the most durable businesses are often the least exciting. Find a service that companies need but don’t want to manage. Deliver it reliably. Make it recurring. Build density. Acquire with discipline. Compound quietly.

It’s not glamorous, and it will never go viral. But nearly a century after Doc Farmer washed his first rag in Cincinnati, the same basic model is still doing what great businesses do best: earning trust, embedding into operations, and compounding.

Recent News

Cintas came into 2026 running well operationally, but it also got a very public reminder that consolidation takes two willing parties.

In January 2025, Cintas submitted a proposal to acquire UniFirst Corporation for $275 per share in cash, valuing the deal at roughly $5.3 billion—about a 62 percent premium to where UniFirst had been trading. UniFirst is the third-largest uniform rental company in North America, and on paper the fit was obvious: more route density, more customers, and an even stronger scale advantage in a business where scale is the whole game. But UniFirst’s board rejected the offer. After multiple attempts to engage, Cintas announced it had ended discussions. CEO Todd Schneider said the company wasn’t able to engage substantively with UniFirst on key terms.

On the Street, the tone stayed constructive. In January 2026, Wells Fargo upgraded Cintas to Overweight and named it a top pick in business and information services for the year, with a $245 price target. By late January 2026, the stock was trading around $195, with a market capitalization of about $74.5 billion.

And the fundamentals kept backing up the “compounding machine” narrative. In fiscal second quarter 2026, revenue reached $2.8 billion, up 9.3 percent year over year, including 8.6 percent organic growth—one of the strongest organic growth rates Cintas had delivered in years. Gross margin hit 50.4 percent, and management raised its full-year guidance to $11.15 to $11.22 billion in revenue. On January 20, 2026, Cintas also announced its latest quarterly cash dividend, extending its long-running pattern of returning cash to shareholders.

Links & Resources

If you want to go deeper on Cintas—what it says about itself, how the industry works, and the strategy frameworks that help explain its moat—these are good places to start.

Cintas Corporation Investor Relations: Cintas’s investor relations site is the primary source for annual reports, quarterly presentations, SEC filings, and earnings call transcripts. It’s where you’ll find the most direct view of how management talks about the business, performance, and priorities.

Cintas Corporate History: Cintas also maintains a corporate history timeline on its website, covering the company from Doc Farmer’s founding to the present. It includes key milestones and photos that add texture to the story.

Industry Analysis: Industry research from firms like IBISWorld can help you understand the uniform rental and broader facility services market—how big it is, what’s driving growth, and why scale and route density shape competition.

Family Business Succession: If the multi-generational arc is what hooked you, look for academic case studies on Cintas’s succession planning. They offer a useful lens on how the Farmer family maintained continuity while still making room for professional management.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy is the framework used in the moat analysis. Michael Porter’s Competitive Strategy is the classic source for the Five Forces framework referenced in the bull and bear case.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music