Analog Devices: The Semiconductor Pioneer That Bridges the Physical and Digital Worlds

I. Introduction & Episode Setup

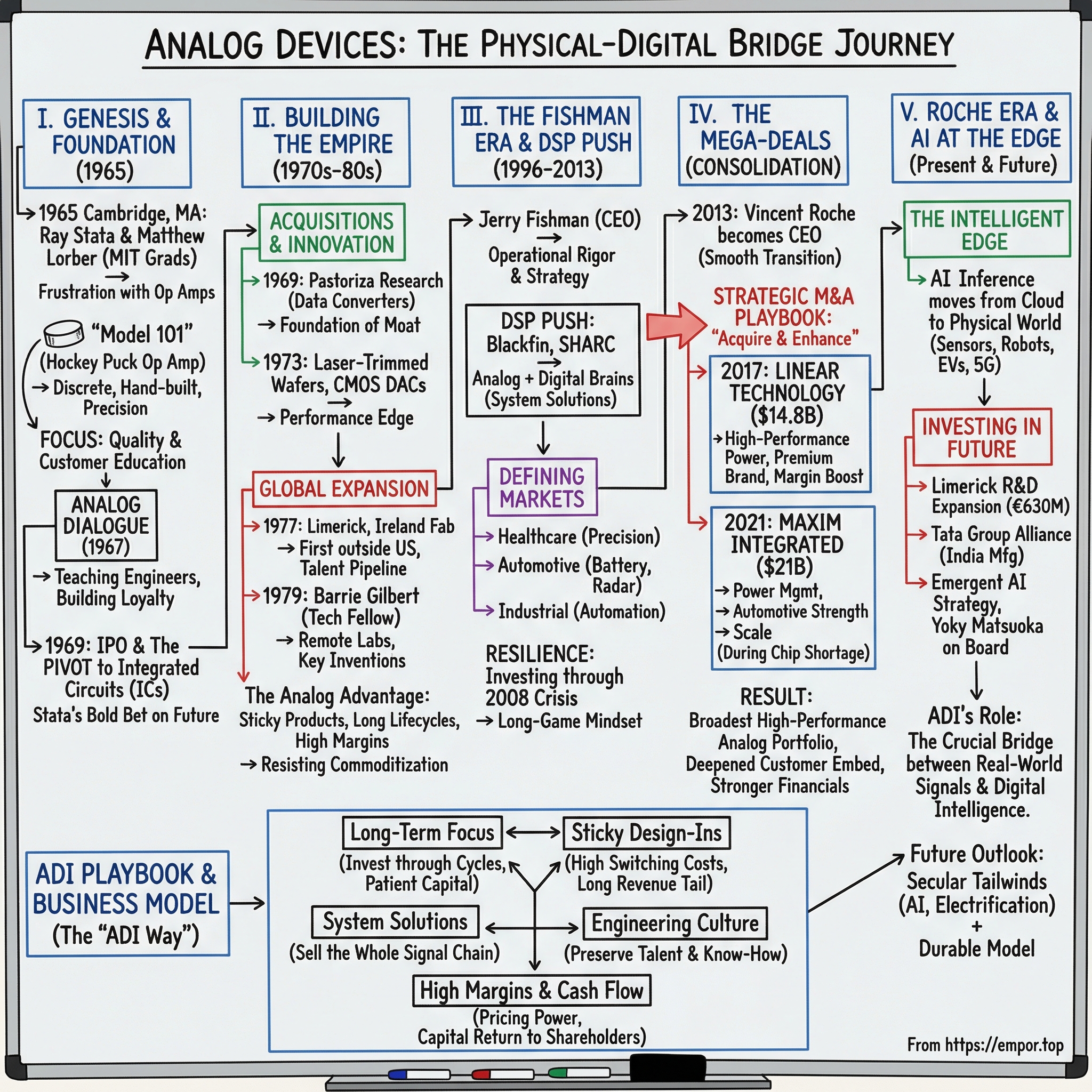

Every sound you hear through a digital speaker, every temperature a car sensor reads, every heartbeat a hospital monitor traces—somewhere in between the messy, continuous reality of the physical world and the clean, binary language of computers, there is a tiny piece of silicon doing the translation. More often than not, that piece of silicon was designed by Analog Devices.

Analog Devices, or ADI, is not a household name. It does not make the phones in your pocket or the laptops on your desk. But it makes the components that allow those devices—and tens of thousands of others—to sense, measure, interpret, and connect to the real world. Think of ADI as the universal interpreter between atoms and bits. Without it, self-driving cars cannot see, 5G towers cannot transmit, and MRI machines cannot image.

The company was founded in 1965 by two MIT graduates in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Six decades later, it has grown into one of the world's premier semiconductor companies, generating $11 billion in revenue in fiscal 2025, serving over 100,000 customers, and employing more than 26,000 people across 35 countries. Its products sit inside everything from industrial robots to electric vehicles, from defense systems to data centers.

The story of ADI is the story of a counter-intuitive bet: that analog—the older, messier, less glamorous cousin of digital—would not only survive the digital revolution, but would become more important because of it. Every digital system needs an analog front end to talk to the physical world. As the world becomes more digitized—more sensors, more connected devices, more AI processing at the edge—the demand for high-performance analog semiconductors only grows.

This is also a story about patience. ADI has navigated semiconductor cycles, dot-com busts, financial crises, and global pandemics. It has made two of the largest acquisitions in semiconductor history—Linear Technology for $14.8 billion and Maxim Integrated for $20.8 billion—and emerged stronger each time. The company has maintained engineering excellence across six decades while industry peers rose and fell around it.

The central question of this piece: How did two MIT engineers build a company that became the indispensable bridge between the physical and digital worlds—and can it sustain that position as artificial intelligence reshapes the semiconductor landscape?

II. The MIT Genesis Story (1965)

In 1965, the semiconductor industry was barely a teenager. Intel would not exist for another three years. The integrated circuit had been invented just six years earlier. Most electronics companies were building discrete transistors and vacuum tube replacements. Into this nascent landscape stepped two young MIT graduates with a very specific vision: Ray Stata and Matt Lorber.

Raymond Stuart Stata was born in 1934 in the small farming community of Oxford, Pennsylvania—about as far from Silicon Valley glamour as one could get. He earned both his bachelor's and master's degrees in electrical engineering from MIT, where the Instrumentation Laboratory was pushing the boundaries of what electronics could measure and control. After graduating, Stata went to work at Hewlett-Packard, not because he wanted a corporate career, but because he wanted to learn how a great technology company actually operated. It was a deliberate apprenticeship.

Matt Lorber, his MIT classmate and apartment-mate, shared the same entrepreneurial itch. Before founding Analog Devices, the two had already taken one swing. They started a company called Solid State Instruments, building on their experience in MIT's labs. Within a year, it was acquired by Kollmorgen's control division. The payout was modest, but the experience was invaluable. Through their work building instruments for Kollmorgen, Stata and Lorber spotted an emerging market for modular operational amplifiers—the fundamental building blocks that allow electronic systems to amplify, filter, and condition analog signals.

The operational amplifier, or op amp, is one of the most important inventions in electronics history. In simple terms, it takes a weak electrical signal—say, the tiny voltage produced by a temperature sensor—and makes it large enough for other circuits to work with. In 1965, op amps were bulky, expensive, and sold primarily to the test and measurement market. Stata and Lorber saw an opportunity to build better ones.

Their first product was the Model 101 op amp: a hockey-puck-sized module that found its way into oscilloscopes, voltmeters, and laboratory instruments. It was not revolutionary in concept—other companies made op amps too—but it was well-engineered and reliable. More importantly, Stata and Lorber were building a company around a philosophy that would define ADI for decades: obsessive focus on signal fidelity. In the analog world, every microvolt matters. A data converter that introduces even tiny errors can ruin a measurement, corrupt an audio signal, or miscalibrate an industrial process. ADI's founding DNA was precision.

The Cambridge and Boston ecosystem provided fertile ground. MIT was a factory for electrical engineering talent. Route 128, the highway circling Boston, was America's original technology corridor—predating Silicon Valley as a hub for defense electronics and instrumentation companies. ADI could recruit world-class engineers, collaborate with university researchers, and sell to a local customer base of defense contractors and instrument makers.

The company grew quickly. In 1967, just two years after founding, ADI published the first issue of Analog Dialogue, a technical journal aimed at engineers. This was a brilliant move that cost almost nothing but built enormous credibility. Analog Dialogue was not marketing fluff—it contained genuine technical content about signal processing, data conversion, and circuit design. Engineers kept copies on their desks and referenced them for years. It positioned ADI not just as a vendor but as an authority. The publication continues to this day, making it one of the longest-running corporate technical journals in the electronics industry.

By 1968, sales had reached $5.7 million—impressive for a three-year-old analog components company. The following year, ADI went public, floating shares on the stock market in 1969. The IPO was a milestone, but Stata was already thinking bigger. He understood that the real opportunity was not in selling individual op amps but in building an ever-expanding portfolio of analog signal processing components—converters, amplifiers, references, sensors—that engineers would design into their systems. Once designed in, these components were extraordinarily sticky. Switching costs were enormous because changing a key analog component meant redesigning entire circuit boards, re-qualifying the system, and risking subtle performance degradation.

This insight—that analog components create deep customer lock-in through design-in stickiness—would become one of ADI's most powerful competitive advantages. It meant that revenue was not won through price wars but through engineering partnerships. Win the design, win the revenue stream for the life of the product. And in industrial and automotive markets, product lives can stretch five, ten, even twenty years.

For investors, this founding period established the template that would compound value for six decades: precision engineering as the core competency, technical authority as the brand, and design-in relationships as the business model. It was a formula that would prove remarkably durable.

III. Building the Analog Empire (1970s–1990s)

The 1970s and 1980s were the decades when ADI transformed from a small op amp maker into a genuine analog empire. The expansion was methodical, guided by Stata's long-term vision and an engineering culture that prized innovation over quick profits.

The first major move came early. In 1969, ADI acquired Pastoriza Research, a small company that specialized in integrated circuits for converting analog signals to digital form. This was prescient. Data converters—the chips that translate continuous real-world signals into the ones and zeros that computers understand—would become the cornerstone of ADI's business. Think of them as the Rosetta Stone between the physical and digital worlds. Every digital audio system, every medical imaging device, every radar system needs data converters. And the quality of the conversion—measured in resolution, speed, and accuracy—determines the quality of the entire system. ADI bet early that being the best in data conversion would be a franchise business.

In 1973, the company achieved two technical firsts that cemented its engineering reputation. ADI became the first company to ship laser-trimmed wafers—a manufacturing technique that dramatically improved the precision of analog chips by using lasers to fine-tune resistor values on the silicon. The same year, it launched the industry's first CMOS digital-to-analog converter, opening up lower-power applications. These were not splashy consumer product launches. They were quiet technical milestones that mattered enormously to the engineers who specified components for high-performance systems.

Ray Stata took on the roles of both CEO and chairman in 1973, a dual position he would hold for over two decades. His leadership style was distinctive: deeply technical, strategically patient, and unusually focused on organizational learning. In fact, Stata would later write influential articles about the "learning organization" concept, arguing that a company's ability to learn faster than its competitors was its ultimate sustainable advantage. At ADI, this manifested as a culture where engineers were given time and resources to pursue deep technical problems, even when the commercial payoff was uncertain.

The international expansion began in 1977 when ADI opened its first manufacturing plant outside the United States, in Limerick, Ireland. This was not just any plant—it was the first semiconductor fabrication facility in Ireland. The decision to go to Ireland was driven by access to a well-educated workforce, favorable tax policies, and proximity to European customers. The Limerick operation would grow over the following decades into one of ADI's most important strategic centers, eventually becoming the company's European regional headquarters.

In 1979, ADI made another cultural statement by naming Barrie Gilbert as its first Technology Fellow—the highest technical honor the company could bestow. Gilbert, a brilliant circuit designer, had invented the Gilbert cell, a mixing circuit used in virtually every radio-frequency system in the world. By creating a Technology Fellow track, ADI signaled that engineers could achieve the same status and recognition as executives without moving into management. This was critical for retaining top analog designers, who were (and remain) among the scarcest human resources in the semiconductor industry. Designing analog circuits is part science, part art. Unlike digital design, which can be heavily automated with software tools, analog design requires deep intuition about how electrons actually behave in silicon. It takes years to develop expertise, and great analog designers are irreplaceable.

By 1982, the numbers told a story of steady compounding. ADI had grown to $156 million in sales, with over 200 products serving 15,000 customers. At the company's annual meeting that year, Stata made a bold prediction: ADI would become a billion-dollar company within eight years. He was off by a few years—the cyclical nature of semiconductors made linear predictions hazardous—but his confidence was grounded in the structural dynamics he understood better than almost anyone.

The data converter business, in particular, never commoditized the way many semiconductor categories did. The reason is fundamental to analog physics. Digital chips can be designed using automated tools and manufactured at ever-smaller process nodes, following Moore's Law. But analog chips operate in a domain where shrinking transistors actually makes things harder. Smaller transistors are noisier, less linear, and more susceptible to manufacturing variations. Building a world-class 24-bit analog-to-digital converter requires deep knowledge of mixed-signal design, process technology, packaging, and testing that cannot be easily replicated. It is one of the few areas in semiconductors where experience compounds rather than depreciates.

This is why analog margins stayed high while digital commodity chips raced to the bottom. ADI's gross margins consistently exceeded 60%—sometimes approaching 70%—because customers were paying for performance that only a handful of companies in the world could deliver. The switching costs, the design-in stickiness, and the irreplaceable nature of analog expertise created a business that looked more like a luxury goods franchise than a typical semiconductor operation.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, ADI continued to expand its product portfolio into new areas: accelerometers, gyroscopes, temperature sensors, and digital signal processors. The company adopted what would later be called a "fab-lite" strategy—owning some manufacturing capacity for its most critical processes while outsourcing commodity production to foundries. This gave ADI the flexibility to control quality on its highest-value products while avoiding the enormous capital expenditure burden that eventually crushed many competitors.

The three decades from founding to the mid-1990s built the foundation that everything else rests on: a dominant position in data conversion, a culture of engineering excellence, deep customer relationships across industrial, automotive, and defense markets, and a financial profile that threw off cash through cycles. It was a slow burn, not a rocket ship—but slow burns in analog semiconductors tend to compound into extraordinary businesses.

IV. The Fishman Era & Digital Signal Processing Push (1996–2013)

On a Thursday morning in March 2013, the semiconductor world lost one of its most respected leaders. Jerald G. Fishman, who had served as ADI's CEO for seventeen years, died of an apparent heart attack at the age of 67. The tributes that poured in from across the industry spoke not just to his business acumen but to a leadership style that was unusually direct, disciplined, and deeply committed to engineering culture.

Jerry Fishman had joined ADI in 1971 in product marketing, just six years after the company's founding. He was raised in Flushing, New York, attended the prestigious Bronx High School of Science, and earned his bachelor's in engineering from City College. While working full-time at ADI, he accumulated three more degrees: a master's in engineering from Northeastern, an MBA from Boston University, and a law degree from Suffolk University. The breadth of his education was a clue to his management philosophy—he believed deeply in understanding every dimension of the business, from circuit design to patent law to capital allocation.

When Fishman took the CEO role from Stata in 1996, ADI was already a successful analog company. But Fishman saw that the future required ADI to bridge analog and digital more explicitly. His signature strategic move was the aggressive push into digital signal processors, or DSPs. A DSP is a specialized microprocessor designed to perform mathematical operations on digitized signals—things like filtering noise from audio, compressing video, or processing radar returns. ADI developed three families of DSPs—Blackfin, SHARC, and TigerSHARC—that found homes in audio processing, military communications, and industrial automation.

The DSP bet was a calculated extension of ADI's core mission. The company's analog front-end chips converted real-world signals into digital data. The DSPs then processed that data. By offering both pieces of the puzzle, ADI could sell complete signal chains rather than individual components, increasing its content per system and deepening customer relationships. It was a classic "more of the value chain" strategy, executed with ADI's characteristic emphasis on high performance rather than high volume.

Fishman also oversaw ADI's foray into MEMS (microelectromechanical systems) technology—tiny mechanical structures etched into silicon that could function as accelerometers, gyroscopes, and microphones. ADI's MEMS accelerometers found their way into automotive airbag systems, where they detected the sudden deceleration of a crash and triggered bag deployment. For a time, ADI was one of the leading MEMS suppliers in the world. But the MEMS business proved challenging. Consumer applications demanded ever-lower prices, and ADI eventually sold its consumer MEMS operations to InvenSense in 2013, choosing to focus on the higher-margin industrial and automotive MEMS applications where precision mattered more than cost.

This willingness to exit businesses that did not fit ADI's high-performance model was a hallmark of Fishman's tenure. He was ruthlessly disciplined about where ADI could and could not win. Electronics Business magazine named him CEO of the Year in 2004, recognizing not just ADI's financial performance—revenue more than doubled during his watch and the share price grew more than threefold—but his strategic clarity.

During the 2008 financial crisis, Fishman made a decision that exemplified long-term thinking in a cyclical industry. While competitors slashed R&D spending to protect short-term margins, ADI maintained its research investment. The logic was simple but required courage: analog product cycles are long, often five to seven years from initial concept to volume production. Cutting R&D during a downturn meant losing an entire generation of products that customers would need when the economy recovered. Fishman bet that the downturn was temporary but the products would be permanent. He was right. When demand snapped back in 2010 and 2011, ADI had a fresh portfolio of products ready to ship while competitors scrambled to catch up.

Throughout this era, ADI competed fiercely with Texas Instruments, the other analog giant. TI had greater scale and a broader product line, but ADI consistently won on performance. In high-end data conversion, precision amplifiers, and specialized signal processing, ADI's parts were simply better. The two companies carved out different strategic positions: TI pursued breadth and manufacturing scale, while ADI pursued depth and performance leadership. Both strategies proved viable, and both companies generated extraordinary returns for shareholders.

Fishman's sudden death left a void, but also a well-prepared successor. Vincent Roche, who had been ADI's president since 2012, stepped into the CEO role. He inherited a company with roughly $2.6 billion in revenue, industry-leading margins, and a dominant franchise in high-performance analog. But the biggest chapters in ADI's growth story were still ahead.

V. The Linear Technology Mega-Deal (2016–2017)

In the summer of 2016, Vincent Roche placed the biggest bet of his career. ADI announced it would acquire Linear Technology Corporation for approximately $14.8 billion, creating what both companies described as "the premier analog technology company." It was the kind of deal that either cements a CEO's legacy or destroys it.

To understand why this deal mattered so much, you need to understand Linear Technology. Founded in 1981 by Robert Swanson, Linear was the analog semiconductor industry's closest equivalent to Hermès—a smaller, extraordinarily profitable company that served discerning customers with the highest-quality products and never, ever competed on price. Swanson had led Linear as CEO since its founding, building a culture of fanatical engineering precision and financial discipline.

Linear's financial profile was the envy of the semiconductor industry. The company routinely posted gross margins above 75%—a number that would make most luxury goods companies jealous. Its operating margins exceeded 40%. The secret was focus: Linear concentrated on power management, data conversion, and signal conditioning products for industrial and automotive markets where performance, reliability, and longevity mattered far more than price. Customers paid premium prices because Linear's products were genuinely superior, and switching to a cheaper alternative meant risking the integrity of the entire system.

The strategic rationale for the acquisition was compelling. ADI dominated data converters and amplifiers. Linear dominated power management—the chips that regulate, convert, and distribute electrical power within electronic systems. Together, they could offer customers the most comprehensive suite of high-performance analog products in the industry. An engineer designing a new industrial controller or automotive sensor system could source virtually every analog component from a single supplier, simplifying procurement and ensuring compatibility.

The financial engineering was ambitious. ADI funded the deal with a combination of approximately 58 million new shares, $7.3 billion in new long-term debt, and balance sheet cash. The company went from a position of roughly $7 per share in net cash to $22 per share in net debt, a leverage ratio of 3.8 times. For a company that had operated conservatively for decades, this was a bold departure. But the math worked because Linear's prodigious cash flow generation meant the debt could be paid down rapidly.

The deal closed on March 10, 2017, after securing all regulatory approvals, including clearance from China's Ministry of Commerce—the final and most uncertain hurdle. Linear Technology shareholders received $46 per share in cash plus 0.2321 shares of ADI stock for each Linear share, valuing the combined enterprise at approximately $30 billion.

Robert Swanson joined ADI's board of directors, providing continuity and a bridge between the two engineering cultures. Integration planning had been largely completed before closing, allowing the combined management team to move directly into execution. Vincent Roche remained as CEO, and the key challenge was not strategy but culture. Both ADI and Linear had strong, engineer-centric cultures, but they were different in texture. Linear was famously insular and self-sufficient; ADI was more collaborative and outward-facing. Merging these cultures without losing the engineering talent that made both companies exceptional was the critical management task.

One of the most important integration decisions involved distribution. ADI consolidated its global distribution volume under Arrow Electronics, streamlining the channel and giving the combined company more leverage in negotiations with distributors and customers. This was operationally complex but financially significant, reducing channel costs and improving visibility into end-demand.

The acquisition transformed ADI's financial profile. Combined revenues exceeded $5 billion, and the power management portfolio from Linear added a major new growth vector. More importantly, it gave ADI a broader offering that increased its relevance to customers designing complex systems. When you sell a customer ten different components instead of three, the relationship becomes deeper, stickier, and more profitable.

For investors watching ADI's acquisition strategy, the Linear deal established a template: acquire a high-quality analog company with complementary products, pristine margins, and deep customer relationships. Integrate carefully, preserve the engineering culture, and use the combined scale to drive operating leverage. This playbook would be repeated—at even larger scale—just a few years later.

VI. The Maxim Integration Gambit (2020–2021)

In July 2020, with the world reeling from a global pandemic and semiconductor supply chains in disarray, Vincent Roche announced ADI's second mega-acquisition in four years: Maxim Integrated Products, in an all-stock deal valued at approximately $21 billion. It was audacious timing and an audacious strategic statement.

Maxim Integrated, founded in 1983 by Jack Gifford, had grown into a $2.3 billion-revenue analog company with particular strength in power management, interface chips, and sensor products for the automotive, industrial, and data center markets. Like Linear before it, Maxim was a high-margin analog specialist with a loyal customer base and a deep engineering bench. The fit with ADI was immediately apparent to industry observers, even if the scale of the deal raised eyebrows.

The strategic logic followed the same principles as the Linear deal but addressed different gaps in ADI's portfolio. Where Linear had brought power management expertise for industrial and communications applications, Maxim brought particular strength in voltage regulators, battery management systems, and automotive power products. The combination created a company with over $9 billion in trailing revenue on a pro forma basis and a formidable position across the analog semiconductor landscape.

The market share arithmetic told the story concisely. Before the deal, ADI's analog revenue was approximately $5.1 billion and Maxim's was roughly $1.9 billion. Combined, they commanded about 12.4% of the global analog market—still behind Texas Instruments at roughly 16.6%, but closing the gap meaningfully. More importantly, the combined company's product breadth meant it could compete with TI on a wider front while maintaining the performance leadership that justified ADI's premium pricing.

The deal closed on August 26, 2021, after navigating a complex regulatory approval process that spanned more than a year. Maxim shareholders received 0.63 shares of ADI common stock for each Maxim share, making it a pure stock transaction that avoided adding debt to the balance sheet—a deliberate contrast with the heavily leveraged Linear deal. ADI had learned from the first mega-acquisition and chose a more conservative financing structure for the second.

Former Maxim CEO Tunç Doluca and former Avago Technologies CFO Mercedes Johnson joined ADI's board, bringing additional semiconductor industry expertise to the governance structure. ADI committed to $275 million in annual cost synergies within 24 months of closing, a target the company expected to reach ahead of schedule.

Integrating Maxim during the COVID era presented unique challenges. Supply chain disruptions were everywhere. Customers were double-ordering components out of fear of shortages. Lead times stretched to six months or longer for some products. Managing this chaos while simultaneously integrating a $21 billion acquisition required exceptional operational discipline. By most accounts, ADI executed the integration well, avoiding the customer disruptions and talent losses that plague many semiconductor mergers.

The combined entity now employed over 26,000 people across 35 countries, with more than 10,000 engineers and 62 design centers. This engineering density was a strategic asset in itself. Analog semiconductor innovation comes from human expertise, not from algorithmic design tools. Having the largest and deepest bench of analog engineers in the world, working across the broadest product portfolio, created compounding advantages in knowledge sharing, customer support, and new product development.

With two massive acquisitions completed in four years, ADI had transformed itself from a $3.5 billion company into an $11 billion revenue powerhouse. The question for investors shifted from "Can they integrate?" to "What does the combined company look like at maturity?" The answer was coming into focus: a high-performance analog platform with unmatched breadth, serving the highest-value applications across industrial, automotive, communications, and healthcare markets—with margins that reflected the irreplaceable nature of what it sold.

VII. The Vincent Roche Era & AI at the Edge (2013–Present)

Vincent Roche's path to the CEO office was unusual for a semiconductor executive. Born and raised in Ireland, he joined ADI in 1988 at the company's Limerick operations—the same facility that had been Ireland's first semiconductor fab when it opened in 1977. He rose through the ranks not as a finance executive or a sales leader but as someone who deeply understood both the technology and the customer applications. When Fishman died suddenly in March 2013, Roche stepped into the CEO role first on an interim basis, and then permanently. He became chairman of the board in 2022, following Ray Stata's retirement from that position after nearly five decades.

Under Roche, ADI has navigated one of the most volatile periods in semiconductor history. The post-COVID boom of 2021-2022 saw extraordinary demand as every industry simultaneously tried to digitize. Then came the inevitable correction. Fiscal year 2024 (ending November 2024) saw revenue decline to $9.4 billion as customers worked through bloated inventories accumulated during the shortage. It was painful—a 23% year-over-year drop—but ADI maintained operating margins above 40% even through the trough, demonstrating the resilience of its business model. Companies with commodity products see margins collapse during downturns. ADI's held firm because its products are specified into systems where performance, not price, is the primary selection criterion.

The recovery was emphatic. Fiscal 2025 delivered $11 billion in revenue, up 17% from the trough, with growth across all end markets. Industrial and communications led the recovery, but automotive and consumer contributed as well. Adjusted operating margins reached 43.5% by the fourth quarter, and the company generated $4.3 billion in free cash flow—an extraordinary 39% of revenue. ADI returned virtually all of it to shareholders through a combination of $2.2 billion in share repurchases and $1.9 billion in dividends.

Roche's most articulated strategic vision is what ADI calls the "Intelligent Edge." The idea is straightforward but powerful: as artificial intelligence moves out of massive data centers and into the real world—into factories, vehicles, hospitals, and power grids—it needs high-performance analog semiconductors to connect AI processors to physical reality. An AI model running in a self-driving car is useless without precise analog sensors to see the road, measure speed, and monitor battery health. An AI-powered industrial robot needs analog signal chains to control motors, measure forces, and communicate with other machines.

This is ADI's structural bull case for the next decade. The more AI proliferates at the edge, the more analog silicon is required. And not just any analog silicon—the demanding latency, precision, and power requirements of edge AI applications play directly to ADI's strengths in high-performance data conversion and signal processing.

The company has backed this vision with significant capital investment. In May 2023, ADI announced a €630 million investment to build a new R&D and manufacturing facility at its Limerick, Ireland campus. The new 45,000-square-foot facility is expected to triple ADI's European wafer production capacity, supporting next-generation signal processing innovations for industrial, automotive, and healthcare applications. The investment was planned as part of the EU's Important Projects of Common European Interest initiative and was expected to create 600 new jobs in Ireland, adding to ADI's existing 1,500-person Irish workforce.

In September 2024, ADI extended its geographic reach further through a strategic alliance with the Tata Group in India. The memorandum of understanding with Tata Electronics, Tata Motors, and Tejas Networks covered potential semiconductor manufacturing at Tata's new fab in Gujarat, as well as collaboration on electronic components for electric vehicles and network infrastructure. While still in the exploratory phase, the partnership reflected ADI's recognition that supply chain diversification—particularly away from concentration in any single geography—had become a strategic imperative.

In October 2025, ADI announced another supply chain move, agreeing to sell its manufacturing facility in Penang, Malaysia to ASE Technology Holdings. The deal, structured as a long-term supply agreement with co-investment from both parties, allowed ADI to maintain production continuity while shifting to a more asset-light model for its back-end operations. The transaction was expected to close in the first half of 2026.

R&D spending remained a priority throughout this period. In fiscal 2024, ADI invested $1.97 billion in research and development—nearly 19% of revenue—even during the inventory correction. This willingness to invest through downturns, echoing Fishman's playbook during 2008, reflected a conviction that analog product cycles are too long to allow gaps in the innovation pipeline. The payoff comes in subsequent years, when new products designed during the downturn reach production and capture demand in the recovery.

Looking at ADI under Roche's decade-plus of leadership, the company has roughly tripled in revenue, executed two of the largest acquisitions in semiconductor history, maintained elite margins through a brutal cycle, and positioned itself at the intersection of analog semiconductors and AI. The Irishman who joined as an engineer in Limerick has proven to be one of the more effective semiconductor CEOs of his generation.

VIII. Financial Performance & Business Model Analysis

To truly understand ADI's financial engine, it helps to start with a simple question: Why are analog semiconductor companies so profitable? The answer reveals why ADI's business model is structurally different from—and arguably superior to—most technology companies.

In digital semiconductors, performance improvements come primarily from shrinking transistors (Moore's Law) and can be replicated by any company with access to a leading-edge foundry. Competition is fierce, products commoditize quickly, and margins compress. In analog, the opposite dynamics prevail. Shrinking transistors actually makes analog design harder, not easier. Performance comes from design expertise accumulated over decades, proprietary process technologies, and deep understanding of how specific customer systems work. Products have lifecycles measured in decades, not quarters. And because each analog chip is tailored to specific performance requirements—noise, linearity, bandwidth, power consumption—there are thousands of niches rather than a few winner-take-all markets.

This is why ADI's gross margins have consistently hovered in the 60-65% range, and why the fiscal 2025 expansion to 61.5% from 57.1% during the trough year represented a return to normalcy rather than an anomaly. Gross margin in analog semiconductors is primarily a function of product mix and pricing power, both of which ADI controls through engineering superiority and deep customer relationships.

Fiscal 2025 showcased the full power of the model at scale. Revenue of $11 billion generated operating cash flow of $4.8 billion and free cash flow of $4.3 billion. That 39% free cash flow margin is among the highest in the semiconductor industry and rivals the best software companies. The capital allocation was disciplined: ADI returned 96% of free cash flow to shareholders, splitting it between dividends ($1.9 billion, at $0.99 per share quarterly) and share repurchases ($2.2 billion).

The end-market diversification provides resilience that investors often underappreciate. ADI reports revenue across four segments: Industrial (the largest, typically 45-50% of revenue), Automotive (roughly 25-30%), Communications (15-20%), and Consumer (5-10%). No single customer represents a disproportionate share of revenue—the 100,000-plus customer base means ADI is not beholden to the spending cycles of any individual company. When automotive demand weakens, industrial or communications may be strengthening. This portfolio effect smooths the cycles that torment more concentrated semiconductor companies.

The fab-lite manufacturing model deserves attention. ADI owns and operates its own fabrication facilities for its most critical and proprietary process technologies—the analog and mixed-signal processes where it has genuine manufacturing know-how that differentiates the product. For less critical production, it uses external foundries. This hybrid approach gives ADI control where it matters most while keeping capital expenditure at manageable levels—typically 4-6% of revenue, far below the 15-25% that leading-edge digital fabs require.

The two mega-acquisitions dramatically expanded ADI's financial scale while improving its margin structure. Linear Technology's legendary profitability lifted the combined company's margins, and the cost synergies from both deals fell largely to the bottom line. The debt incurred for the Linear deal was paid down rapidly thanks to the combined entity's cash generation, and the Maxim deal's all-stock structure avoided adding leverage entirely.

For those tracking ADI's performance going forward, two metrics deserve particular attention. First, free cash flow margin: this single number captures ADI's ability to convert revenue into cash, reflecting pricing power, operational efficiency, and capital discipline. Sustained free cash flow margins above 35% would indicate the business model is intact and the acquisitions are delivering as expected. Second, revenue growth by end market: because ADI serves long-cycle industrial and automotive customers, watching the mix and growth rate across these segments reveals whether the company is gaining or losing share in its most strategically important markets. These two KPIs—free cash flow margin and end-market revenue growth—are the vital signs of ADI's financial health.

IX. Playbook: The ADI Way

After six decades, certain patterns have emerged that constitute a distinct strategic playbook. Understanding these patterns is essential for evaluating whether ADI's past success can continue.

The most obvious pattern is long-term thinking in a cyclical industry. Semiconductors are notorious for boom-bust cycles driven by inventory buildups and corrections, macroeconomic fluctuations, and demand shifts. Most semiconductor companies manage to these cycles—hiring during booms, firing during busts, cutting R&D when revenues fall. ADI has consistently resisted this pattern. From Stata's founding philosophy through Fishman's 2008 decision to maintain R&D and Roche's similar choice during the 2024 correction, the company has invested through downturns. This requires management credibility with the board and shareholders, a strong balance sheet to absorb temporary margin pressure, and conviction that the long product cycles in analog make steady investment the only rational strategy.

The acquisition philosophy is equally distinctive. ADI does not acquire to cut costs or eliminate competitors. It acquires to enhance its product portfolio and deepen its relevance to customers. Both Linear Technology and Maxim Integrated were high-quality companies with complementary products, strong margins, and engineering cultures that ADI respected. The integration approach in both cases was careful and deliberate—preserving engineering teams, maintaining product lines, and focusing on operational synergies rather than gut-wrenching restructurings. This "acquire and enhance" philosophy has worked because ADI has chosen targets that were already excellent businesses, not turnaround projects.

Why do analog companies make such attractive acquisition targets? The answer lies in the nature of the products. Analog chips have long lifecycles, sticky customer relationships, and high margins. When you acquire an analog company, you are buying a stream of design wins that will generate revenue for years to come. The products do not become obsolete every two years like digital processors. And the engineering talent—the scarcest resource in analog—comes with the deal. As long as you do not alienate those engineers, the value persists.

ADI's approach to building switching costs is worth studying. Rather than relying on proprietary interfaces or lock-in tactics that antagonize customers, ADI creates switching costs through system-level integration. When ADI sells a complete signal chain—sensor front-end, data converter, DSP, and power management—to an automotive customer, the entire system is qualified as an integrated solution. Replacing any single component means re-qualifying the entire system, a process that can take months and cost millions. This is organic lock-in that customers accept because the integrated solution genuinely works better than a mix-and-match alternative.

The distribution strategy reflects customer intimacy at scale. With 100,000-plus customers, ADI cannot provide hands-on engineering support to every buyer. Instead, it segments its customer base and uses a combination of direct sales for the largest accounts, specialized distributors for mid-tier customers, and online channels for smaller buyers. The consolidation under Arrow Electronics after the Linear acquisition created a more efficient channel structure that maintained customer service while improving economics.

Perhaps the most underrated element of the ADI playbook is engineering culture preservation through mega-mergers. Most large acquisitions in technology destroy engineering culture. The acquirer imposes its processes, the acquired company's best engineers leave, and within a few years, the innovative capacity that justified the premium price has evaporated. ADI has avoided this fate—so far—by respecting the engineering traditions of its targets. Linear Technology's Milpitas design center, Maxim's portfolio-level expertise, and ADI's own legacy teams continue to operate with meaningful autonomy, united by shared standards but not homogenized into a single mold.

The competitive moat that results from all of this—decades of accumulated analog design expertise, a proprietary process technology library, deep customer relationships, a broad and complementary product portfolio, and a culture that attracts and retains the world's best analog engineers—is a textbook example of what Hamilton Helmer would call "cornered resource." The resource in question is human expertise, and it cannot be replicated by throwing money at the problem.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Competitive Analysis

The Bear Case

Every investment thesis deserves rigorous skepticism, and ADI has legitimate vulnerabilities that investors should weigh carefully.

China represents the most immediate geopolitical risk. An estimated 20-25% of ADI's revenue comes from Chinese customers, and in September 2025, China's Ministry of Commerce launched an anti-dumping investigation into U.S. analog IC imports—specifically targeting interface and gate-driver chips from companies including ADI. The investigation alleged dumping margins exceeding 300% on some product categories and demanded that U.S. companies submit detailed cost and pricing data. If the probe results in punitive tariffs or restrictions, ADI could lose a significant portion of its Chinese revenue, with limited ability to redirect that demand to other geographies in the short term. This is not a hypothetical risk—it is an active proceeding with a target conclusion date of September 2026.

Cyclical risk is inherent to the semiconductor business, and ADI is not immune. The 2024 inventory correction demonstrated that even a premium analog franchise can see revenue drop 23% in a single year. While ADI's margins held up better than most, the revenue volatility creates uncertainty around capital allocation timing and can temporarily compress valuation multiples. There are already whispers in the industry about the possibility of double-ordering during the current recovery—customers placing inflated orders to secure supply—which could set up another correction in late 2026 or 2027.

The serial acquisition strategy carries integration risk that compounds with each deal. ADI has now absorbed two massive companies in four years. While both integrations appear successful by most metrics, the organizational complexity of managing a $11 billion, 26,000-employee company with three distinct heritage cultures is substantial. Each acquisition adds complexity to product lines, customer relationships, and internal processes. There is a limit to how much organizational metabolism can absorb.

Texas Instruments remains a formidable competitor with meaningful scale advantages. TI operates the most advanced 300mm analog fabrication facilities in the world, giving it a structural cost advantage on high-volume products. TI's revenue is roughly 50% larger than ADI's, and its strategy of bringing manufacturing in-house allows it to undercut competitors on price in commodity analog categories. While ADI competes on performance rather than price, TI's manufacturing scale gives it the ability to gradually move upmarket and compete more directly with ADI's product lines.

The Bull Case

The secular tailwind from AI at the edge is real and potentially transformative. Every AI inference engine deployed in a factory, vehicle, medical device, or communications network needs analog semiconductor content to interface with the physical world. Industry analysts estimate that edge AI could drive high-single-digit-to-low-double-digit annual growth in high-performance analog demand for the next five to seven years. ADI's product portfolio—spanning data conversion, signal processing, power management, and sensors—is uniquely positioned to capture this demand.

ADI's competitive position through the lens of Michael Porter's Five Forces is unusually strong. Supplier power is moderate (ADI has diversified its manufacturing base). Buyer power is limited by switching costs and the small share of total system cost that analog components represent. The threat of new entrants is low because analog design expertise takes decades to build. The threat of substitutes is minimal because analog functions cannot be digitized away—they are fundamental to physics. Rivalry is intense but disciplined, with ADI and TI as the clear leaders in a market that is growing faster than most semiconductor segments.

Through Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers framework, ADI exhibits at least four of the seven powers. Counter-positioning: ADI's fab-lite model and performance-first strategy differ fundamentally from TI's scale-driven approach, and TI cannot easily mimic ADI's model without abandoning its own. Cornered resource: the world-class analog engineering talent that ADI has accumulated over six decades is genuinely scarce and irreplicable. Process power: decades of accumulated know-how in analog design, mixed-signal integration, and customer application engineering create a capability that cannot be reverse-engineered from the outside. Switching costs: system-level design-ins create organic lock-in that persists for the life of customer products.

The financial trajectory supports the bull case. ADI's free cash flow generation—$4.3 billion in fiscal 2025—gives it enormous flexibility to invest in R&D, pursue strategic acquisitions, return capital to shareholders, and weather cycles. The planned price increases taking effect in February 2026—reportedly 10-30% on selected products, following TI's own price hikes—should further support margins and demonstrate pricing power.

The critical supplier dynamic deserves emphasis. In many of ADI's end markets—automotive safety systems, medical imaging, military communications, 5G infrastructure—the analog components ADI provides are not optional. They are specified into systems where failure is not acceptable. This gives ADI pricing power that far exceeds its share of total system cost. When an analog chip represents 0.1% of a car's bill of materials but 100% of its airbag sensor functionality, the customer will pay whatever ADI charges.

XI. Epilogue: The Future of the Physical-Digital Bridge

Ray Stata is ninety-one years old. He still sits on the board of the company he founded sixty years ago in a Cambridge apartment. What would he make of today's ADI?

The company he started with a hockey-puck-sized op amp now generates more revenue in a single quarter than it did in its first two decades of existence. The Limerick facility he opened as a bold international bet in 1977 is now the anchor of a €630 million European expansion. The engineering culture he and Fishman built survived two mega-mergers that would have destroyed lesser organizations. And the fundamental insight that animated the founding—that bridging the analog and digital worlds is a franchise business—has proven more durable than anyone could have predicted in 1965.

The next frontier is AI inference at the edge, and ADI is positioning itself squarely in the path of that wave. As AI models move from cloud data centers into physical systems—autonomous vehicles, smart factories, precision agriculture, remote healthcare—every one of those systems will need high-performance analog silicon to sense, measure, and interact with reality. The data must be converted, the signals must be processed, the power must be managed. These are the same problems ADI has been solving for sixty years, now in service of a technology that did not exist when the company was founded.

The energy transition presents another secular opportunity. Electric vehicles need sophisticated battery management systems, power conversion electronics, and motor control—all areas where ADI's products are already designed in. Renewable energy installations require precise measurement and control of power flows. Grid modernization demands the kind of high-reliability, high-precision sensing that ADI has specialized in for decades.

Can ADI finally overtake Texas Instruments as the world's largest analog semiconductor company? The gap has narrowed significantly with the Linear and Maxim acquisitions, but TI's manufacturing scale and broader product line provide a buffer. Perhaps the more relevant question is whether market share ranking matters when both companies are growing and the overall analog market is expanding. ADI has never needed to be the biggest to be the most profitable.

The enduring lesson of Analog Devices is that in a world obsessed with the next digital breakthrough, the physical world has not gone away. It still needs to be sensed, measured, interpreted, and controlled. The companies that do this well—with precision, reliability, and decades of accumulated expertise—occupy a position in the technology stack that is as essential as it is underappreciated. The bridge between atoms and bits is not glamorous. But it is indispensable.

XII. Recent News

The most significant recent development is ADI's strong fiscal 2025 performance, which confirmed the cyclical recovery from the inventory correction trough. Fourth-quarter revenue of $3.08 billion showed year-over-year growth across all end markets, and full-year revenue of $11 billion represented a 17% increase over fiscal 2024. The company guided first-quarter fiscal 2026 revenue to $3.1 billion, signaling continued momentum into the new fiscal year.

In October 2025, ADI and ASE Technology announced a strategic collaboration under which ASE would acquire ADI's Penang, Malaysia manufacturing facility. The transaction, expected to close in the first half of 2026, includes a long-term supply agreement and co-investment to expand capabilities. The deal reflects ADI's ongoing optimization of its manufacturing footprint toward an asset-lighter model for back-end operations.

China's Ministry of Commerce continued its anti-dumping investigation into U.S. analog IC imports, launched in September 2025. The probe targets interface and gate-driver chips and has demanded detailed cost and pricing data from U.S. semiconductor firms. The investigation's expected conclusion in September 2026 represents a material overhang for ADI and other U.S. analog companies with significant China exposure.

ADI announced price increases of 10-30% on selected products, effective February 2026, following similar moves by Texas Instruments. The pricing actions reflect both the recovery in end-demand and the industry's broader shift toward protecting margins after the 2023-2024 downturn.

Wall Street responded favorably to these developments. Multiple analysts raised price targets following the fiscal 2025 results, with Cantor Fitzgerald setting a $350 target and maintaining an Overweight rating, citing early-stage AI demand as a multi-year growth driver.

XIII. Links & Resources

- Analog Devices Investor Relations: investor.analog.com

- Analog Dialogue Technical Journal: analog.com/en/analog-dialogue.html

- Ray Stata's biography and writings: raystata.com

- ADI Fiscal 2025 Annual Report: investor.analog.com/financial-info/annual-reports

- Linear Technology Acquisition Press Release (March 2017): investor.analog.com

- Maxim Integrated Acquisition Completion (August 2021): investor.analog.com

- €630 Million Limerick Investment Announcement (May 2023): analog.com

- Tata Group Strategic Alliance (September 2024): investor.analog.com

- ASE Strategic Collaboration (October 2025): analog.com

- China Anti-Dumping Investigation Coverage: Tom's Hardware, Bloomberg

- Semiconductor Industry Association Reports: semiconductors.org

- MIT Innovation Ecosystem Resources: professional.mit.edu

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music