AbbVie: From Spinoff to Pharmaceutical Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Overview

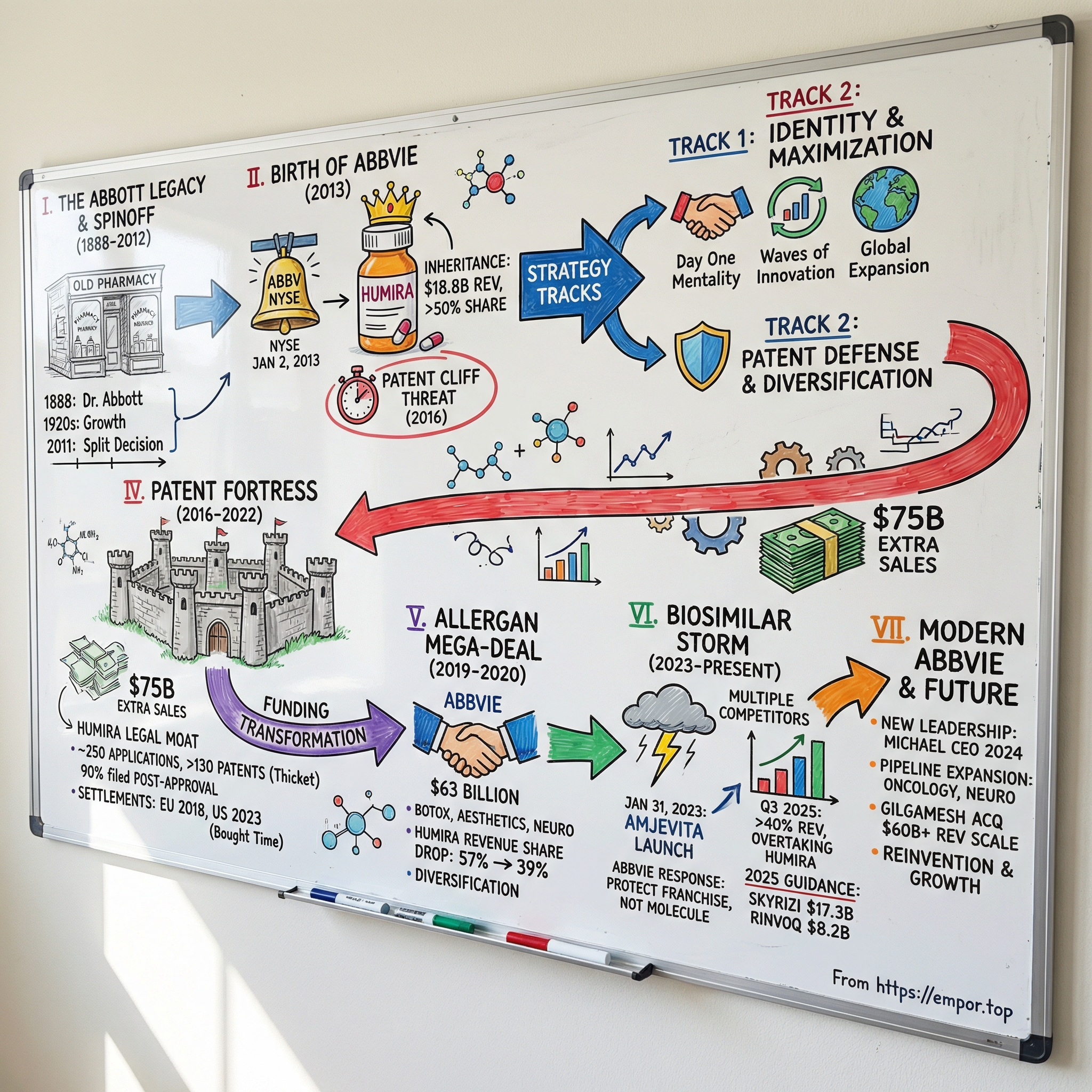

The New York Stock Exchange opened on January 2, 2013 with a fresh ticker lighting up the screens: ABBV. This wasn’t a typical debut. AbbVie wasn’t some scrappy startup going public; it was a brand-new company cut cleanly out of Abbott Laboratories, a healthcare institution more than a century in the making.

Richard Gonzalez—an Abbott lifer, three decades deep—rang the opening bell as AbbVie’s CEO. And while the moment looked celebratory on the surface, the reality underneath was sharper. AbbVie had inherited something extraordinary and dangerous: Humira, the best-selling drug in the world, and a revenue base that leaned on it heavily. The clock on its patent protection was already ticking.

That sets up the question at the heart of this story: how does a company born with one overwhelmingly dominant product avoid getting crushed when the patent runs out? AbbVie didn’t just try to soften the landing. It built a playbook—part law, part science, part dealmaking—that would become one of the most studied (and argued over) strategies in modern pharma.

The ingredients are big and a little unbelievable: a patent defense effort so aggressive it became legend, a $63 billion acquisition that rewired the company’s future, and a deliberate effort to replace its own cash cow before the market could do it for them. What could have been a slow-motion decline instead became a reinvention.

Today, AbbVie brings in over $60 billion in annual revenue on a trailing basis—scale that would have sounded ambitious, if not absurd, when ABBV first appeared on the tape. The company that once looked like “Humira and hope” has pushed new engines to the forefront. In the most recent quarter reported (Q3 2025), Skyrizi and Rinvoq together delivered more than 40% of total revenue, topping Humira’s contribution for the first time.

To understand how that happened, we’re going back to the beginning: from Wallace Abbott’s 19th-century Chicago roots to the modern-day chess match of patents, biosimilars, and blockbuster drug economics. Along the way, we’ll break down how patent fortresses get built—and eventually breached—why the Abbott split created the conditions for outsized value, and how AbbVie used transformational M&A to buy time, diversify risk, and reshape its identity.

The big themes—patent lifecycle management, escaping blockbuster dependency, and corporate reinvention—aren’t just pharma lessons. They’re core strategy lessons, period. So let’s start where all of this really begins: the legacy that made AbbVie possible.

II. The Abbott Legacy & Strategic Separation (1888–2012)

Picture Chicago in 1888: stockyards, railroads, and the rough-edged momentum of an industrial city on the rise. At the corner of Lake and Dearborn, in a small pharmacy, a 30-year-old physician named Dr. Wallace Calvin Abbott kept running into the same problem. The medicines of the day were often liquid, inconsistent, and hard on patients. Dosing could be guesswork, and guesswork isn’t a great operating system for healthcare.

Abbott’s answer was elegantly practical: “dosimetric granules,” tiny pills made to deliver precise, repeatable doses of alkaloid-based medicines. It was pharmaceutical innovation with an industrial mindset—standardization, reliability, scale—decades before that logic became a manufacturing religion in other industries.

From there, the Abbott Alkaloidal Company grew the way the best healthcare businesses tend to grow: by turning scientific know-how into products people actually used. By the 1920s, Abbott Laboratories was producing a widening range of medicines and healthcare staples—from anesthetics to vitamins—and building the muscle to manufacture and distribute at volume.

Over the next century, Abbott expanded again and again, riding waves of medical progress: antibiotics in the 1940s, intravenous solutions in the 1950s, and by the 1990s, a full-blown healthcare conglomerate that spanned pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, nutrition, and medical devices. What began as one doctor’s frustration had become a global enterprise.

But scale can be a blessing and a burden. By 2011, Abbott was fighting very different wars at the same time—heart stents in one arena, infant nutrition in another, diagnostics in another, and biologic drugs in yet another. Each business demanded a different playbook. Devices moved fast and lived or died on hospital relationships and product cycles. Pharmaceuticals moved slowly, requiring huge R&D spending, years of clinical trials, and constant regulatory risk. Trying to optimize all of it under one roof was getting harder, not easier.

That’s where Miles White comes in. White had been Abbott’s CEO since 1999, and he’d spent years weighing what he called the trade-off between focus and diversification. In October 2011, he made the decision that would set up everything that follows: Abbott would split into two companies. The diversified medical products business—diagnostics, devices, and nutrition—would remain Abbott. The research-based pharmaceutical business, including Humira, would become AbbVie.

The logic was straightforward, and it was strategic. The “new Abbott” could pursue its own priorities and investor base, leaning into businesses with different rhythms and capital needs. The pharma company, meanwhile, could be built around the realities of drug development: big R&D bets, long timelines, and the patent cycle that defines the economics of the industry. Separation meant each side could run its own capital structure, incentives, and strategy without constantly compromising for the other.

Richard Gonzalez was the obvious choice to lead AbbVie. He’d joined Abbott in 1977 and rose through the pharmaceutical side, eventually running Abbott’s pharma operations. Trained as an electrical engineer, he was known internally as intensely analytical—someone who wanted to understand the machinery of the business down to the smallest moving part. AbbVie wasn’t going to be run on vibes. It was going to be run on models, probabilities, and a clear-eyed view of what was coming.

And AbbVie got a serious inheritance. It didn’t just receive Humira—already a blockbuster—it also took key R&D programs, manufacturing capabilities, and roughly 21,000 employees. Abbott shareholders received one share of AbbVie for every Abbott share they owned, which meant the new company would start life with a real shareholder base and immediate liquidity.

In hindsight, the split also fit a broader industry shift. Healthcare conglomerates were giving way to more focused entities as companies tried to match structure to strategy. Investors wanted clarity: what kind of business is this, exactly, and what are the risks?

Still, the timing carried a catch. Humira was throwing off massive cash, the kind of cash that can fund a company’s independence and ambition. But everyone close to the story knew the other half of the equation: Humira’s primary patents were headed toward expiration in 2016, just a few years after the spinoff.

So AbbVie didn’t begin life with a clean slate. It began with a gift and a deadline. And that deadline would shape everything the company did next.

III. Birth of AbbVie & The Humira Inheritance (2013–2015)

The New York Stock Exchange bell rang on January 2, 2013, and ABBV officially existed. Richard Gonzalez stood there with a new logo, a new ticker, and a company that looked, at first glance, like a standard corporate spinoff. But AbbVie wasn’t stepping into the market with the usual clean-slate optimism. It was stepping out with a deadline. In just a few years, the primary patents on the product that paid the bills were set to expire.

AbbVie came into the world fully formed from Abbott’s pharmaceutical division—and it came with Humira (adalimumab), an anti-TNF monoclonal antibody that had already become one of the most valuable assets in all of medicine. Humira had been approved by the FDA on December 31, 2002, and by the European Medicines Agency in September 2003. It started as a rheumatoid arthritis drug, then kept widening its footprint, indication by indication, into a platform therapy for inflammatory disease.

In AbbVie’s first year as an independent company, it produced about $18.8 billion in revenue, and Humira made up the overwhelming share. That concentration was the real story. AbbVie wasn’t inheriting a balanced portfolio; it was inheriting a single franchise so large it could distort everything around it. Well over half of company revenue flowed from one molecule—an exposure level that would make any investor nervous, no matter how strong the product looked.

And Humira really was strong. It had already been doing $7.9 billion a year in 2011 under Abbott, and it kept climbing, eventually reaching a peak of $21.2 billion in 2022. That trajectory wasn’t just commercial execution—it was the compounding effect of a drug that worked across multiple diseases, supported by a growing body of clinical evidence and relentless lifecycle management.

The science helped explain why Humira became so expansive. It targets tumor necrosis factor-alpha, or TNF-alpha, a major driver of inflammation. When TNF-alpha is overactive, the immune system essentially stays in attack mode, fueling diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and psoriasis. Humira dampens that signal. The breakthrough wasn’t only that it worked—it was that the same mechanism applied across joints, skin, and the gut, letting AbbVie keep expanding where the drug could be used.

Gonzalez knew exactly what the spinoff really was. AbbVie had world-class commercial and manufacturing infrastructure, real R&D capability, and the cash flow of a giant. But strategically, it was living on a single pillar. The job wasn’t just “run a pharma company.” It was: protect Humira for as long as the law allowed, and build the next revenue engine before the market forced the issue.

So the early agenda ran on two tracks.

One track was identity. AbbVie needed to stand on its own—its own culture, systems, and narrative—without the Abbott umbrella. Gonzalez pushed a “Day One” mentality: act like a company that still has to prove itself, even if the numbers say you’ve already arrived.

The other track was maximization. While Humira still had exclusivity, AbbVie leaned into expansion—new indications, broader global reach, and deeper penetration. By the time AbbVie launched, Humira had approvals in more than 87 countries and was being used by more than 843,000 patients worldwide. And there was still room to grow.

Internally, AbbVie organized the plan around “waves of innovation.” The first wave was straightforward: push Humira as far as it could go. The second wave was about follow-on immunology products—therapies that could keep patients in the franchise once Humira’s moat started to shrink. The third wave was bigger: new therapeutic areas that could reduce dependence on any single drug.

From the outside, the first years looked almost effortless. The machine Abbott built kept running: manufacturing stayed stable, the sales force didn’t miss a beat, and doctors saw the same product with a different company name at the top of the label. It felt seamless.

But inside AbbVie, the clock didn’t stop. Quarter after quarter, the same question dominated: what happens after Humira? Analysts asked about biosimilars. Strategy sessions circled the patent timeline. AbbVie might have looked like one of the richest new companies in pharma, but it carried a threat most companies never face: an existential shock scheduled on the calendar.

And the way AbbVie decided to deal with that shock—especially how it chose to defend Humira—would become one of the most controversial and closely studied patent strategies in modern pharmaceutical history.

IV. The Patent Fortress Strategy: Humira's Legal Moat (2016–2022)

By early 2016, AbbVie’s North Chicago headquarters was thinking less like a drug company and more like a litigation command center. Humira’s core patents were rolling toward their expiration window, and every major biosimilar player was circling. Richard Gonzalez and his team weren’t guessing what would happen next. They were preparing for it—line by line, filing by filing, courtroom by courtroom.

What AbbVie built around Humira wasn’t a single wall. It was layers. Over time, the company filed roughly 250 U.S. patent applications tied to Humira and ended up with more than 130 granted patents. The density of it all was so unusual that the industry gave it a name: a “patent thicket.” And crucially, most of that thicket didn’t come from Humira’s original discovery. Around 90% of the patents were filed after the drug was approved in 2002.

That matters because it’s not how most drug protection looks. In the standard pharmaceutical arc, a company patents the molecule, gets a finite window of exclusivity, and then eventually faces generic or biosimilar competition. Even successful products usually have a manageable set of patents—maybe a handful, maybe a couple dozen. AbbVie’s approach was different in both scale and structure: it multiplied the number of legal choke points a competitor would have to clear before it could sell a Humira biosimilar.

Each patent covered a different slice of the product and how it’s used: formulations, dosing regimens, manufacturing processes, delivery devices, and methods of treatment in specific patient populations. Many patents were linked through terminal disclaimers, and the portfolio included a large share of patents described as non-distinct or duplicative variations—meaning challengers couldn’t just win one big case and be done. They’d have to keep winning, over and over, across a sprawling map.

When Humira’s primary composition-of-matter patent expired in December 2016, that was supposed to be the beginning of the end. Instead, it became the beginning of the real strategy. AbbVie didn’t need one unbreakable patent. It needed enough patents that breaking through became a slow, expensive grind.

So when biosimilar manufacturers began the legal process, AbbVie responded with volume. In litigation after litigation, it put dozens of patents on the table—often 60 to 80 at a time. For a would-be entrant, it created an ugly decision tree: try to design around the patents, fight through them in court for years at enormous cost, or settle.

Many chose to settle. AbbVie reached agreements with biosimilar makers including Amgen, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, and Fresenius Kabi. The structure was consistent: competitors could enter Europe starting in October 2018, but they would hold off on the U.S. until 2023. That split wasn’t accidental. The U.S. was where Humira’s economics were most powerful, and AbbVie effectively traded earlier European competition for extended U.S. exclusivity.

Those extra years were not a rounding error. They were a windfall—estimated at about $75 billion in sales that likely would have been exposed much earlier under a more typical patent timeline. The filings, the legal bills, the years of negotiating: it was all expensive. It was also wildly profitable.

The strategy drew predictable backlash, and not just in op-eds. A coalition of Humira purchasers sued AbbVie, arguing that the patent thicket violated antitrust laws. AbbVie’s defense was straightforward: it was using the patent system as it exists, and U.S. patent law doesn’t set a cap on how many patents a company can hold. The courts agreed. In June 2020, Judge Manish Shah of the Northern District of Illinois dismissed the case. The Seventh Circuit affirmed in August 2022, with Judge Frank Easterbrook writing the opinion, concluding that a large number of patents on a single product, by itself, does not violate antitrust law.

Meanwhile, the politics got loud. In a 2021 House hearing, Humira’s patent strategy became a bipartisan punching bag. Gonzalez defended the logic that’s long been pharma’s core argument: today’s profits fund tomorrow’s innovation—“The products that are on the market today pay for the products of the future.” At the same time, he also suggested that the patent office’s willingness to grant overlapping patents was part of the problem, an implicit acknowledgment that the system itself had created the conditions for this kind of play.

Whatever you thought of the tactics, the results were undeniable. In 2021, Humira generated $20.7 billion in sales and was widely described as the world’s most lucrative drug. Each year without U.S. biosimilar competition wasn’t just another good year—it was cash flow on a scale that could change the company’s trajectory.

And that’s the key: the patent fortress didn’t just protect Humira. It bought AbbVie time to transform. As 2022 closed and U.S. biosimilar entry finally approached, the thicket had done what it was built to do. It delayed the storm long enough for AbbVie to fund major moves—most notably the Allergan deal—and to prepare the next generation of growth with drugs like Skyrizi and Rinvoq.

V. The Allergan Mega-Deal: Transformation Through Acquisition (2019–2020)

By the time AbbVie’s Humira fortress had bought them breathing room, Richard Gonzalez knew what that extra time was really for: a second act. Because even with every patent and settlement in place, the ending was still the same. Eventually, the U.S. market would open, biosimilars would arrive, and Humira’s dominance would start to erode. AbbVie needed a new base of earnings before that happened.

On June 25, 2019, the answer arrived in the form of a headline-sized deal: AbbVie would buy Allergan for about $63 billion.

Allergan was already famous for living by the deal. Under CEO Brent Saunders, it had been aggressively reshaped through acquisitions and divestitures, and it still carried the scars of the collapsed Pfizer merger in 2016. But what mattered to AbbVie wasn’t Allergan’s corporate drama. It was Allergan’s product mix—and how cleanly it solved AbbVie’s biggest strategic problem.

In 2018, Humira produced around $20 billion in sales and represented roughly 57% of AbbVie’s total revenue. That’s not just concentration; that’s dependence. Gonzalez described the logic with disarming clarity: “Essentially, Humira is buying the assets that will replace it in the long term.”

The terms were designed to make the bet big, but palatable. Allergan shareholders would receive 0.8660 AbbVie shares and $120.30 in cash for each Allergan share, a sizable premium to get the deal across the finish line. When Allergan put it to a vote in October 2019, the result wasn’t close: 99.64% of shareholders approved.

Strategically, Allergan wasn’t a doubling down—it was a hedge. AbbVie’s crown jewel was immunology. Allergan brought an entirely different engine room: Botox, both therapeutic and cosmetic; eye care products like Restasis; gastrointestinal treatments; and a central nervous system portfolio that included Vraylar and Ubrelvy. There was little product overlap and a lot of diversification. Crucially, it wasn’t diversification into “more Humira-like risk.” In aesthetics—especially Botox—biosimilar-style competition wasn’t the same looming cliff.

The math behind the story was simple. Fold Allergan into the mix, and Humira’s share of AbbVie’s revenue fell from about 57% to roughly 39%. AbbVie wasn’t suddenly immune to the patent cycle. But it would no longer be a one-franchise company living on borrowed time.

Getting to closing, though, meant surviving the regulatory gauntlet. The Federal Trade Commission took a close look at overlaps and potential competition. Under the consent agreement, AbbVie and Allergan agreed to divest Allergan’s exocrine pancreatic insufficiency drugs, Zenpep and Viokace, to Nestlé. They also transferred brazikumab—an IL-23 inhibitor in development for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis—back to AstraZeneca. That last requirement was a reminder of how tightly the government scrutinizes future competition, not just today’s revenue: AbbVie was being required to give up a pipeline asset in an adjacent space.

The deal officially closed on May 8, 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic was upending healthcare systems worldwide. With Allergan folded in, AbbVie’s annual revenue base rose to roughly $48 billion—a step-change in scale that put it firmly in the top tier of global pharma.

Markets didn’t cheer at first. The day after the announcement, AbbVie’s stock dropped—investors worried about debt, integration risk, and whether AbbVie was paying too much for growth. AbbVie insisted it wasn’t buying growth; it was buying durability. The company projected more than $2 billion in annual pre-tax synergies by year three, and those targets were ultimately met. Financing included $38 billion in commitments from Morgan Stanley and MUFG Bank.

Even the human details signaled who would run the combined company. Saunders was initially expected to join AbbVie’s board, but he ultimately passed, choosing new ventures over a subordinate role. AbbVie also didn’t try to mash everything into one monolith. It kept distinct business units—particularly for aesthetics versus traditional pharmaceuticals—aiming to preserve what made Allergan’s brands valuable while still capturing back-office and operational efficiencies.

In the end, the Allergan deal wasn’t a trophy acquisition. It was AbbVie’s strategic escape hatch: a way to turn Humira’s last protected years into a broader platform—one with cash flows that didn’t all depend on a single molecule, and enough optionality to face the biosimilar era with something other than hope.

VI. Navigating the Biosimilar Storm (2023–Present)

January 31, 2023 finally arrived—the day the clock AbbVie had been staring at for a decade started chiming out loud. In Thousand Oaks, California, Amgen shipped the first U.S. supply of Amjevita, its biosimilar to Humira. After years of settlements and delays, the U.S. market was officially open, and the most protected blockbuster in modern pharma was about to meet competition.

Amgen’s launch strategy also exposed the strange logic of American drug pricing. Amjevita came in two versions: one with only a small list-price discount and another with a much deeper cut—5% and 55% off Humira’s roughly $80,000 wholesale list price. That’s a huge spread for the same medicine, but it made sense in a system where rebates, formularies, and middlemen often matter more than the sticker price. Even at the steeper discount, the price was still more than double what Humira cost when it first launched.

And Amjevita wasn’t alone for long. Over the course of 2023, at least eight adalimumab biosimilars entered the U.S. market. The long-promised “price collapse” did come in some places, but it was slower and messier than many people expected.

For AbbVie, this wasn’t a surprise so much as the moment of truth. The patent fortress had done what it was built to do: delay the storm. Now the company had to prove the second half of the strategy—transitioning away from Humira without blowing a hole in the income statement.

Instead of racing biosimilars to the bottom on price, AbbVie leaned into the realities of how U.S. healthcare actually works. Payers had already set their 2023 formularies, and many initially kept Humira in a preferred position. At the same time, AbbVie executed the move it had been preparing for: shifting patients to newer immunology drugs, Skyrizi and Rinvoq—products with their own patent runways stretching well into the 2030s. The goal wasn’t to defend every last Humira prescription. It was to keep patients inside the AbbVie ecosystem.

The financial picture looked exactly like a cliff—until you zoomed out and saw the landing gear. Humira’s U.S. business fell sharply, and global Humira sales dropped 55.7% year over year. By 2024, Humira brought in $9 billion for the full year, down from its $21.2 billion peak.

But AbbVie’s internal mantra—“protecting the franchise, not the molecule”—wasn’t just a slogan. Skyrizi became the new anchor. In 2024, it generated $11.7 billion in revenue, up more than 50% year over year, making it AbbVie’s largest product. Rinvoq added $6.0 billion, also up more than 50%. Together, they delivered nearly $18 billion in 2024 revenue, rapidly filling the gap Humira left behind. By Q3 2025, the shift was even more visible: Skyrizi reached $4.7 billion in quarterly revenue (up 47% year over year) and Rinvoq hit $2.2 billion (up 35%). Combined, they made up more than 40% of AbbVie’s total revenue that quarter—overtaking Humira decisively.

As the transition held, AbbVie grew more confident. During 2025, the company raised its revenue guidance three times, ultimately projecting $60.9 billion for the year. It expected Skyrizi to reach $17.3 billion and Rinvoq about $8.2 billion—together cresting $25 billion in 2025 sales. And management pushed its longer-term view higher too, raising its 2027 outlook to more than $31 billion combined for Skyrizi and Rinvoq—about $4 billion above prior guidance—with Skyrizi projected at over $20 billion and Rinvoq over $11 billion.

Meanwhile, Allergan’s aesthetics business did what AbbVie bought it to do: provide ballast. Botox continued to produce around $6 billion a year, helped by its manufacturing complexity and brand strength, especially in cosmetic use. That said, aesthetics wasn’t immune to the broader economy. In 2024 and 2025, that segment faced softer demand, with global sales slipping modestly as consumers pulled back.

By late 2024, the first phase of the biosimilar era had a clearer shape. Humira still held about 30% of the adalimumab market—better than many expected, but nowhere near the monopoly it once was. The bigger takeaway wasn’t that Humira finally declined. Everyone knew it would. The takeaway was that AbbVie had made the cliff survivable: delay the drop long enough to build the replacement, diversify the base, and then manage the handoff with discipline when the gate finally opened.

VII. The Modern AbbVie: Culture, Innovation & Strategy (2020–Today)

Once the Humira transition plan was in motion, AbbVie faced the next inevitability: leadership succession.

In February 2024, the board unanimously chose Robert A. Michael to succeed Richard Gonzalez as CEO, effective July 1, 2024. Gonzalez shifted to executive chairman. Then, in February 2025, the board elected Michael to take on the additional role of chairman effective July 1, 2025—at which point Gonzalez was set to fully retire from the board. It was the clean handoff AbbVie could afford to make only because the company had already proven it could live beyond Humira. By the end of Gonzalez’s tenure, AbbVie’s market capitalization had grown from $54 billion at the 2013 spinoff to over $300 billion. Revenue nearly tripled. Adjusted diluted EPS rose from $2.93 to $11.11.

Michael represented continuity, but not stasis. He was a 32-year Abbott and AbbVie veteran who began in Abbott’s financial development program, earned an MBA from UCLA Anderson, and worked his way through leadership roles across pharmaceuticals, aesthetics, diagnostics, diabetes care, and nutrition. After the 2013 spinoff, he built AbbVie’s first financial planning organization and helped shape the diversification strategy designed to absorb Humira’s loss of exclusivity. As CFO starting in 2018, and later as COO, he became one of the architects of AbbVie’s post-Humira financial reset—returning the company to peak revenue within two years of the U.S. patent expiration, something many analysts had written off as unrealistic.

That evolution shows up in how AbbVie looks and feels today. Roughly 55,000 employees operate across a much wider map than the immunology-heavy Humira era: immunology, neuroscience, oncology, aesthetics, eye care, and women’s health. And the Allergan integration—adding about 17,000 employees—became one of AbbVie’s defining managerial tests. Instead of forcing a single culture onto the combined company, AbbVie blended the organizations, borrowing what worked from both.

For investors, though, the most important cultural signal is simpler: what the pipeline is producing now, and what it might produce next.

In 2025, AbbVie stacked up notable approvals. Rinvoq earned its ninth U.S. indication, with FDA approval for giant cell arteritis—making it the first oral JAK inhibitor for adults with GCA. Emrelis (telisotuzumab vedotin) was approved as the first treatment for previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer with high c-Met protein overexpression. Epkinly (epcoritamab) received expanded approval for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma.

And the 2026 setup looked even busier. AbbVie reported positive Rinvoq data in vitiligo and planned to submit in alopecia areata, with hidradenitis suppurativa and systemic lupus erythematosus readouts anticipated during the year. Pivekimab sunirine, an antibody-drug conjugate for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, was under FDA review. Tavapadon, a once-daily oral treatment for Parkinson’s disease, had been submitted for regulatory review. Management expected Rinvoq’s new indications to add roughly $2 billion to peak-year sales—exactly the kind of incremental expansion that keeps a franchise compounding long after the initial launch.

AbbVie also kept placing smaller, targeted bets to widen the funnel. In early 2025, it agreed to acquire Gilgamesh Pharmaceuticals for up to $1.2 billion, adding bretisilocin—a novel short-acting serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonist in development for major depressive disorder. It was a clear signal of growing ambition in neuropsychiatry, building on the earlier Cerevel acquisition that brought multiple neuroscience candidates into the portfolio.

Even as the company scaled, it leaned into the “North Chicago hometown” identity that traces back to Abbott. Since 2013, the AbbVie Foundation provided $283 million in grants to more than 265 organizations. The $40 million donation to build the Neal Math and Science Academy in North Chicago wasn’t just philanthropy—it doubled as a long-term investment in the community and the future talent pipeline around its headquarters.

Financially, the message was steadier: rewards now, confidence later. The board declared an increase in the quarterly dividend from $1.64 to $1.73 per share beginning February 2026, about 5.5% growth. After the Q3 2025 report, AbbVie raised its 2025 adjusted diluted EPS guidance range to $10.61–$10.65. Management reaffirmed expectations for high single-digit compound annual revenue growth through 2029.

Under Michael, the strategy was framed around three pillars: scientific leadership in core therapeutic areas, operational excellence driven by digital transformation, and sustainable growth through balanced portfolio management. But the real shift is more visceral than that. This is no longer a company built around one molecule and a defensive perimeter. AbbVie now runs a portfolio that spans small molecules, biologics, antibody-drug conjugates, and an expanding pipeline across multiple modalities—moving from survival mode into something closer to an offensive posture, where it can go looking for the next category rather than protecting the last one.

VIII. Playbook: Lessons in Pharmaceutical Strategy

Zoom out from the courtroom drama, the pipeline charts, and the $63 billion headline, and the AbbVie story starts to read like a strategy case study with unusually high stakes. This wasn’t just a company trying to keep a blockbuster alive. It was a spinoff trying to outrun a countdown clock—and doing it with a mix of legal engineering, portfolio design, and disciplined execution.

The result is a playbook that’s both instructive and, depending on your perspective, a little unsettling.

The Art of Patent Lifecycle Management

AbbVie treated intellectual property the way it treated R&D: as a long-running program, not a one-time event. Instead of relying solely on Humira’s original patents, the company kept filing throughout the product’s life—layering protections around formulations, manufacturing methods, dosing schedules, delivery devices, and specific uses.

The combined effect was the “patent thicket” we just walked through: not one decisive shield, but dozens of overlapping tripwires. For biosimilar manufacturers, that created a brutal “freedom to operate” problem. Even if you could navigate around some patents, clearing all of them—or even just enough of them—became slow, expensive, and uncertain.

This is where the controversy lives. Critics saw the strategy as turning a system meant to reward invention into a mechanism for delaying competition. AbbVie’s counterargument was simpler: it played the rules as written. The broader lesson, for anyone running a pharma business, is unavoidable: patent strategy isn’t a legal afterthought. It’s a core operating capability, and it can buy you years that are worth tens of billions.

Managing Blockbuster Dependency and Diversification Timing

Humira was a gift and a trap. The cash flows were enormous, but the dependency was existential. AbbVie’s key insight was that you don’t diversify after the cliff. You diversify while the blockbuster is still printing money.

That’s what made the timing of Allergan so consequential. AbbVie did the deal in 2019, when Humira was still dominant and the company could act from strength, not panic. It used the good years to pay for the next era. That’s a lesson that travels well beyond pharmaceuticals: if one product or one customer accounts for most of your business, the moment you feel safe is usually the moment you should be funding your escape plan.

The Delay-Switch-Innovate Playbook

Once you understand AbbVie’s sequence, the Humira story stops looking like a single tactic and starts looking like a coordinated campaign.

First: delay. Not forever, just long enough. The legal strategy wasn’t about preventing biosimilars in perpetuity—it was about pushing U.S. competition out to 2023 so AbbVie could prepare a replacement base.

Second: switch. Before biosimilars arrived, AbbVie began moving patients toward newer immunology drugs—Skyrizi and Rinvoq—so the revenue didn’t have to die with Humira.

Third: innovate. Switching only works if the next products are strong enough to earn their place. AbbVie’s newer drugs weren’t just “Humira, but slightly different.” They gave physicians and patients a reason to move before they were forced to.

The lesson here isn’t “copy AbbVie’s patents.” It’s that if you’re going to face a cliff, you need a sequence—and you need to start early enough that the sequence can actually work.

Balancing Shareholder Returns with Drug Pricing Criticism

AbbVie also ran straight into the uncomfortable reality of pharma: the strategies that create the most shareholder value often create the most public anger. Humira became a symbol—not just of medical progress, but of how drug pricing and exclusivity can play out in the U.S. system.

AbbVie’s posture was pragmatic. It defended pricing and patent protection as the engine that funds future innovation, and it leaned on patient assistance programs to blunt the sharpest edges. The broader takeaway is that pharmaceutical companies don’t operate in a purely economic market; they operate in a political one. Long-term durability requires maintaining a social license to operate, because profit maximization without legitimacy eventually invites reform.

The Meta-Lesson: Strategic Coherence

More than any single decision, AbbVie’s edge was coherence. The patent strategy bought time. The Allergan acquisition bought diversification. The R&D focus built the replacements. The patient transition protected the franchise.

Each move would look risky in isolation—aggressive litigation, a massive acquisition, a deliberate shift away from a cash cow. Together, they formed a single, consistent answer to the same question AbbVie was born with: what happens when Humira finally loses exclusivity?

AbbVie’s story is often told as the story of one drug. The better version is that it’s the story of a company that refused to let one drug be its destiny.

IX. Bear vs. Bull Case Analysis

AbbVie’s future still splits the investing world into two camps. Not because the numbers are hard to read, but because the story behind those numbers can be read two very different ways: either AbbVie pulled off a rare reinvention, or it simply bought time—and time eventually runs out in pharma.

Bear Case: The Gathering Storm

The bear view starts with a blunt premise: Humira wasn’t the last patent cliff. It was just the first one AbbVie had to survive in public. Skyrizi and Rinvoq are the new pillars, but they won’t be immune forever. And the very tactics that extended Humira’s life could come back to haunt the entire industry. Patent reform proposals aimed at patent thickets and terminal disclaimer strategies threaten to make “delay” a weaker lever the next time around—closing off the playbook that, for Humira, helped protect an enormous amount of revenue.

Then there’s the balance sheet. AbbVie has been paying down the debt it took on to buy Allergan, but the burden still matters. With interest rates no longer at rock-bottom levels, debt service is real money—cash that could otherwise go into R&D, business development, or simply cushioning the next downturn.

Bears also point to execution risk in exactly the areas AbbVie is counting on most. Immunology is brutally competitive, with Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly, and a steady stream of biotech challengers pushing new mechanisms and new data. In a market that’s more fragmented than the Humira era ever was, assuming Skyrizi and Rinvoq can compound into something Humira-like may be too rosy.

Layer on top of that the political and economic backdrop. U.S. pricing scrutiny keeps ratcheting up, and the Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare negotiation provisions are seen by many as the start of a longer trend, not the end of one. Allergan’s aesthetics business provides diversification, but it’s also more cyclical than prescription immunology and faces the emergence of competing neurotoxins. And, in the longer run, bears worry about platform disruption: cell and gene therapies, precision medicine, and AI-enabled discovery shifting the center of gravity away from the kinds of drug franchises AbbVie has historically dominated.

Bull Case: The Transformation Vindicated

The bull case is basically the opposite framing: AbbVie didn’t just survive Humira’s loss of exclusivity. It used Humira’s final protected years to build a sturdier company.

Start with diversification. AbbVie is no longer “Humira and hope.” The revenue base is spread across multiple meaningful franchises, with no single product above roughly a fifth of total revenue. In 2024, Skyrizi delivered $11.7 billion, Rinvoq brought in $6.0 billion, Botox added another $6.0 billion, and even a declining Humira still produced $9 billion. That mix looks a lot less fragile than the one AbbVie debuted with in 2013.

Bulls also see the next-generation immunology franchise as a real growth engine, not just a patch. Management has projected more than $31 billion in combined Skyrizi and Rinvoq revenue by 2027. And unlike Humira’s broad anti-TNF mechanism, these drugs are positioned as more targeted therapies with expanding indications. Skyrizi has been gaining share in inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and both products have patent runways stretching well into the 2030s.

Scale is the other advantage bulls keep coming back to. A company doing more than $60 billion in trailing revenue has more shots on goal: it can fund a deeper pipeline, run more trials, and absorb the inevitable failures that come with drug development. And AbbVie has plenty of near-term pipeline catalysts: additional Rinvoq indications like vitiligo and alopecia areata, tavapadon for Parkinson’s disease, pivekimab for rare cancers, and bretisilocin from the Gilgamesh deal for depression. Add in AbbVie’s track record integrating Allergan—while other pharma giants have stumbled on big mergers—and the bull argument becomes that this is a company that can execute at scale.

Leadership continuity rounds it out. The transition from Richard Gonzalez to Robert Michael was deliberate and orderly, and bulls credit Michael as one of the key architects of AbbVie’s post-Humira reset—particularly the speed with which the company returned to peak revenue after U.S. Humira exclusivity ended.

Framework Analysis

From a Porter’s Five Forces perspective, AbbVie plays in an industry with enormous barriers to entry—regulation, R&D costs, and complex manufacturing see to that. Supplier power is moderate, but specialized biologics manufacturing adds real constraints. Buyer power is rising as payers consolidate and government negotiation expands. Substitutes exist, but biosimilars and competing modalities take time and capital to build. Rivalry, meanwhile, is intense, because the prize for winning a category is massive. AbbVie’s scale helps it compete, but the direction of travel—toward greater buyer power—remains a structural headwind.

Through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, AbbVie’s durable advantages have historically come from scale economies (spreading R&D and commercial infrastructure across a large base), switching costs (clinical familiarity and patient inertia), and process power (biologics manufacturing expertise that’s harder to replicate than it looks). Humira’s patent fortress functioned as its own kind of protection too—but one that may be less repeatable if the legal and regulatory environment tightens.

KPIs That Matter Most

If you’re trying to decide which thesis is winning in real time, two indicators matter more than almost anything else.

First: Skyrizi and Rinvoq combined quarterly revenue growth. It’s the cleanest signal of whether AbbVie’s handoff away from Humira is still compounding—and whether management can credibly reach its 2027 target.

Second: new product revenue as a share of total revenue. That’s the “future replacing the present” metric. It tells you whether AbbVie is building a broader bench, or just concentrating again—this time around a different pair of drugs.

Those two measures, more than headline earnings or one-off guidance changes, will ultimately determine whether AbbVie’s reinvention becomes a durable new era—or a temporary escape from the last cliff.

X. Epilogue: The Next Chapter

The office where Richard Gonzalez once planned AbbVie’s Humira endgame now belongs to Robert Michael. And the terrain outside the window has changed. AbbVie spent its first decade learning how to defend a single molecule. Now it operates like a real platform company—immunology and neuroscience alongside oncology, aesthetics, and whatever comes next.

The transformation is real. But the challenge hasn’t disappeared. It’s just evolved.

As AbbVie looks toward 2030, the competition won’t come only from the usual Big Pharma peers. A new wave of biotech companies is showing up with different tools: AI-assisted discovery, more specialized biology, and modalities like cell therapy and precision medicine that can rewrite what “best-in-class” even means. In immunology, the bar keeps moving from “works broadly” to “works precisely,” as newer mechanisms aim for better outcomes with fewer tradeoffs.

The rules around defense may shift, too. Post-Humira, the patent system is under a brighter spotlight. Legislative proposals that target patent thickets and the terminal disclaimer system are aimed directly at the kind of playbook AbbVie used to extend Humira’s run. If those reforms land, future lifecycle strategies may have to be tighter and more selective—more clearly rooted in meaningful innovation, less in sheer volume. The irony is hard to miss: the company that proved how powerful the old system could be may be one of the reasons the system changes.

So what would “great” look like for AbbVie in 2030? The optimistic version is straightforward: Skyrizi and Rinvoq keep compounding, the neuroscience portfolio produces therapies that actually change the course of diseases like Parkinson’s and depression, and the pipeline graduates multiple new franchises—not just one more replacement for the last one. In that scenario, revenue pushes toward $80 billion, and the company finally achieves what it has been chasing since day one: no single product dominating the whole story.

And the bigger lessons travel well beyond pharma.

For founders, AbbVie is proof that your starting position isn’t your destiny. A company can be born with a ticking clock and still build something durable—if it confronts reality early and invests ahead of the curve.

For investors, it’s a reminder that concentration risk is as real as it looks on a pie chart—but also that execution can bend outcomes that seem predetermined.

For healthcare stakeholders, AbbVie embodies the industry’s central tension: the same strategies that funded the next wave of innovation also delayed lower-cost access for millions. That tradeoff isn’t a side plot. It’s the policy debate that will keep shaping what’s allowed, what’s rewarded, and what’s possible.

AbbVie’s arc—from spinoff to pharmaceutical powerhouse—ultimately comes down to reinvention. It recognized that survival would require transformation, then proved it could execute through controversy, competition, and a once-in-a-generation patent cliff. More cliffs will come. The competition will get tougher. But if the last thirteen years established anything, it’s that AbbVie doesn’t wait for the terrain to become safe. It learns how to cross it.

XI. Recent News

AbbVie’s Q3 2025 update showed a company that’s still gaining momentum after the Humira handoff, not just surviving it. Net revenues came in at about $15 billion, and management raised full-year 2025 adjusted diluted EPS guidance to $10.61–$10.65—about $0.10 above the prior range. It also lifted full-year 2025 revenue guidance to $60.9 billion, the third upward revision of the year, citing broad-based overperformance across the portfolio.

The headline drivers were still Skyrizi and Rinvoq. In Q3 2025, Skyrizi delivered $4.7 billion in revenue, up 47% year over year. Rinvoq added $2.2 billion, up 35%. AbbVie nudged its 2025 Skyrizi outlook up by $200 million to $17.3 billion and kept Rinvoq at roughly $8.2 billion. Longer term, management raised its combined 2027 outlook for the pair to more than $31 billion—about $4 billion higher than before—signaling continued confidence that the new immunology franchise can outgrow the Humira era rather than merely replace it.

The pipeline kept moving too, with several tangible wins and several near-term shots on goal. The FDA approved Rinvoq as the first oral JAK inhibitor for giant cell arteritis, marking its ninth U.S. indication. Emrelis was approved for previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer with high c-Met protein overexpression, and Epkinly’s label expanded in follicular lymphoma. Looking ahead, pivekimab sunirine remained under FDA review for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm, and tavapadon was submitted for regulatory review in Parkinson’s disease. Positive data in vitiligo set Rinvoq up for additional filing activity in 2026, with alopecia areata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and systemic lupus erythematosus readouts expected during the year.

Leadership changes, meanwhile, stayed exactly as scripted. Robert Michael became CEO on July 1, 2024, and then stepped into the chairman role on July 1, 2025, succeeding Richard Gonzalez, who is set to fully retire from the board. AbbVie also raised its quarterly dividend by about 5.5% to $1.73 per share beginning February 2026. The next earnings report—covering Q4 2025 and full-year 2025 results—is scheduled for February 4, 2026.

On the deal front, AbbVie agreed to acquire Gilgamesh Pharmaceuticals for up to $1.2 billion, adding bretisilocin, a candidate in development for major depressive disorder. With the transition away from Humira largely executed and new growth engines scaling, management reaffirmed its expectation for high single-digit compound annual revenue growth through 2029.

XII. Links & Resources

- AbbVie Investor Relations

- AbbVie Pipeline Overview

- AbbVie Q3 2025 Financial Results

- AbbVie Full-Year 2024 Financial Results

- AbbVie CEO Robert Michael Biography

- Seventh Circuit Humira Antitrust Decision (2022)

- SEC EDGAR – AbbVie Filings

- ClinicalTrials.gov – AbbVie Studies

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music