Zions Bancorporation: The Story of the Intermountain West's Banking Powerhouse

I. Introduction: America's Pioneer Bank

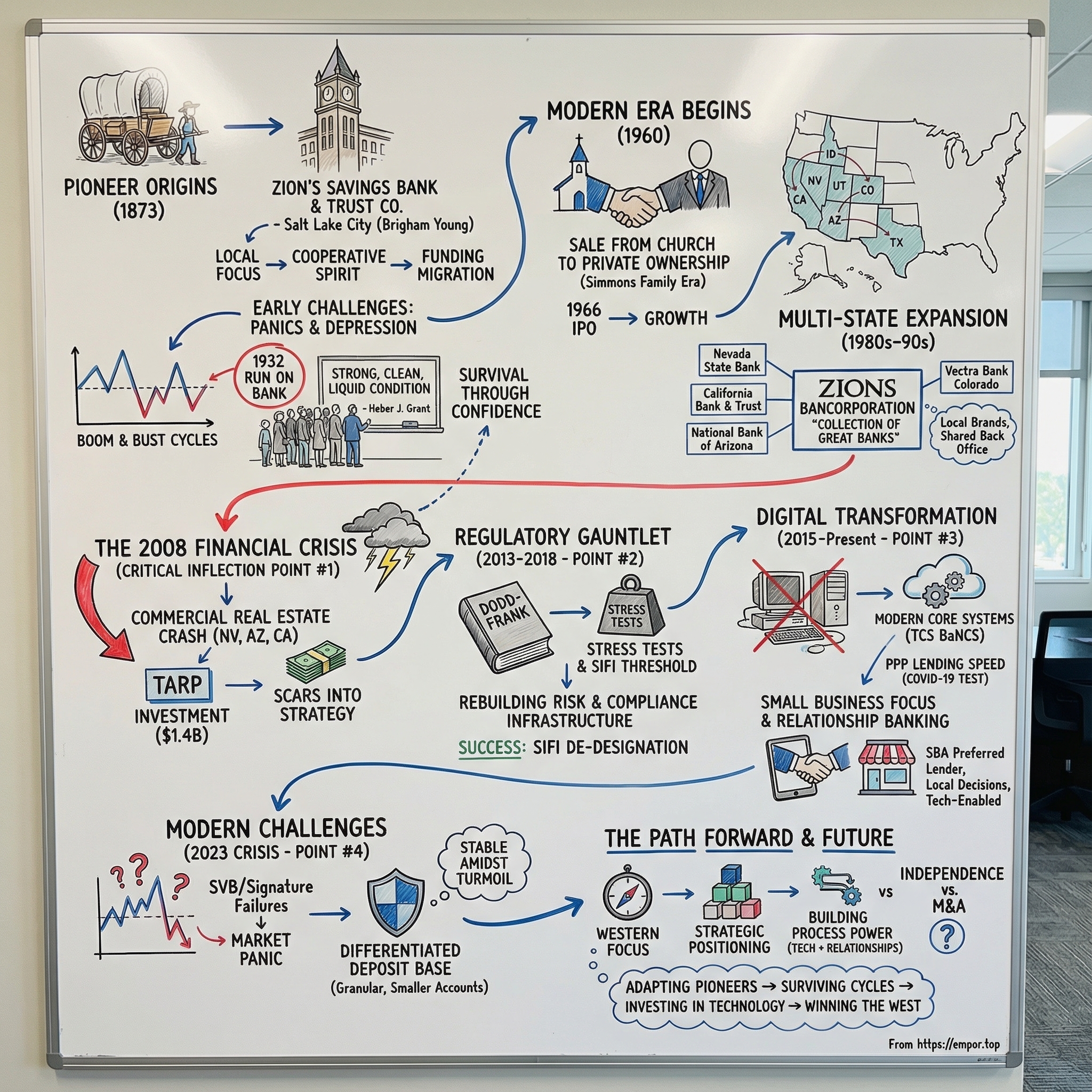

On a sweltering July afternoon in 1873, Brigham Young called twelve of Salt Lake Valley’s most influential citizens into his modest office between the Beehive House and the Lion House on South Temple. The assignment was straightforward and urgent: Utah needed a bank. A place ordinary residents could trust with their savings, a source of local credit, and a financial backbone sturdy enough for a remote territory that was still far from the nation’s centers of capital. Young even had a name in mind: Zion’s Savings Bank and Trust Co.

What came out of that meeting would become America’s oldest financial institution west of the Mississippi. And it would do something most businesses—especially banks—never manage: endure. Panics and depressions. Booms and busts. Wars, recessions, technological revolutions, and wave after wave of new regulation. Through it all, Zions stayed headquartered in Salt Lake City for more than 150 years, growing up alongside the West it helped finance.

Today, Zions Bancorporation is a major financial services company with approximately $89 billion in total assets as of December 31, 2024, and $3.1 billion of annual net revenue in 2024. It operates as a national bank rather than as a bank holding company and does business through seven brands: Zions Bank, Amegy Bank of Texas, California Bank and Trust, National Bank of Arizona, Nevada State Bank, Vectra Bank Colorado, and the Commerce Bank of Washington.

The puzzle that animates this story is simple to ask and surprisingly hard to answer: how did a bank founded by Mormon pioneers to serve an isolated frontier economy become one of America’s most distinctive regional banks—and why did it survive when so many didn’t?

The answer isn’t one magical moment. It’s a chain of pivotal decisions, a few near-death experiences, and several strategic reinventions that unfolded across three centuries. It’s a story of geographic focus as strategy, of leadership continuity and change, of regulatory battles both won and lost, and of a long, expensive technology transformation that’s now trying to carry a bank founded before the telephone into the AI age.

Zions describes itself as a “Collection of Great Banks”—local brand names and local management teams in major Western markets, tied together by a shared platform. And the Intermountain West has been its home territory since before there was a Utah. In hindsight, that bet looks almost obvious: Utah, Idaho, Arizona, Nevada, and Colorado became some of the fastest-growing markets in America.

But the road from handcarts to fintech partnerships was anything but straight.

II. Founding Context: Mormon Settlement & The California Gold Rush (1850s-1870s)

Zions’ founding date is a clue to how Brigham Young thought about risk, resilience, and timing.

By the early 1870s—roughly twenty-five years after the first Latter-day Saint pioneer company entered the Salt Lake Valley in 1847—Utah Territory had moved past bare survival. Farms were producing. Small businesses were taking shape. New arrivals kept coming. Families were spreading out across the territory. And crucially, a few banks were already operating.

Then trouble started brewing back East. A financial crisis was spreading across the Eastern U.S., and Young saw it as a warning flare. If capital dried up and the national economy turned, Utah couldn’t rely on distant institutions to protect local savings or keep credit flowing. So he pushed his community to do what frontier communities always had to do: prepare for the future with their own tools.

Young’s instincts proved timely. The Panic of 1873 hit that autumn, crushing eastern financial markets and kicking off a depression that would drag on for years. But by the time the shockwaves rolled west, the Saints in Utah already had a dedicated savings bank of their own.

In July 1873, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints established Zion’s Savings Bank & Trust Company to take over the savings department of the Deseret National Bank. That matters, because Deseret National Bank—incorporated in 1868—was Utah’s fourth attempt at creating a national bank. In other words: this wasn’t a casual experiment. It was the next iteration of a community that had been trying, and retrying, to build stable financial infrastructure in an isolated territory.

Banking in Utah Territory came with constraints that eastern financiers didn’t have to think about. It was far from the nation’s major pools of capital, too small to command much attention, and shaped by a tight-knit religious community with its own economic priorities.

Still, the decision moved fast. Four days after Young convened local leaders, the bank was incorporated on July 5, 1873, under the laws of the Utah Territory, with $200,000 in capital stock. Modest on paper, significant in context—Utah wouldn’t become a state for another 23 years.

The bank opened its doors on October 1, 1873. That first day, it gathered $5,876 in deposits from 46 depositors. And the original ledger contains a detail that feels surprisingly modern: five of the first 15 depositors listed were women, and another was a women’s organization—at a time when many financial institutions wouldn’t even allow women to open accounts in their own names.

Brigham Young, president of the LDS Church, served as the bank’s first president. The mission was explicitly tied to building Zion: encourage immigration to Utah and strengthen the church’s financial position. In a letter to a friend in England, Young spelled out both the cooperative spirit and the sales pitch: “This institution is a cooperative one, and we think it is likely to meet with favor. The interest allowed is at a rate of ten per cent per annum, compounded semi-annually.”

That rate was eye-catching, and it came with a message. In an era before deposit insurance, depositors were taking real risk—and the bank had to offer a real premium to attract scarce frontier capital. It was also a mechanism for something very specific: funding Mormon migration. Families could save money for the “emigration of their friends,” building up enough to bring relatives from Europe or from the eastern states.

Even the bank’s physical presence carried symbolism. Its Salt Lake City office on Main Street—along with the clock outside—became part of local history. The building, known as the Eagle Emporium Building, is the oldest existing commercial building in downtown Salt Lake City and the city’s only remaining commercial structure built before the transcontinental railroad was completed. Built for William Jennings, Utah’s first millionaire, it originally housed his mercantile business. Powered by a water wheel, the clock was erected in 1873—a literal marker of time in a town trying to anchor itself to the future.

Those early years locked in patterns that would echo for generations: serving small depositors and local businesses, embedding deeply in the community, and being willing to finance the next wave of western industry for the long haul. Around this period—before and just after the turn of the century—Zions’ financing helped launch or support firms tied to copper mining, railroads, electric power, and gas. Because the bank’s policy included long-term business lending, it became intertwined with the industrial development of Utah in a way few institutions ever manage.

In Utah, “local bank” wasn’t a branding choice. It was the operating system.

III. Statehood, Expansion, & The Western Banking Model (1890s-1960s)

Utah achieved statehood in 1896, and with it, Zion’s moved from territorial improvisation into the formal U.S. banking system. But “official” didn’t mean “safe.” The early twentieth century handed Zions two gut checks: first the Panic of 1907, and then the far more punishing Great Depression.

The Panic of 1907 was the first real jolt to what had otherwise been steady progress. Even so, the long arc kept bending upward: deposits grew from about $2 million in 1901 to roughly $9 million by 1918.

Then came 1932. On the morning of February 15, customers began a run on the bank. Lines stretched out the door and down the street. Inside, tellers got a simple instruction: pay everyone who asks. Over the next two and a half days, depositors withdrew about $1.5 million.

Near the end of the second day, Heber J. Grant—president of both the bank and the LDS Church—made a move that was part reassurance, part challenge. He placed a sign in the bank’s window declaring that the institution was “in a very strong, clean, liquid condition,” that it could “pay off every depositor in full,” and that fear of failure was “without foundation” and “positively foolish.” The effect was immediate. The block-long line began to thin. Within five or six days, many of the same customers returned—this time to redeposit their money.

By the end of the month, deposits exceeded withdrawals. Zions had lived through one of the darkest moments in American banking, not by hiding, but by projecting confidence and proving liquidity in real time.

After World War II, the West changed faster than ever—and Zions changed with it. A major turning point arrived on December 31, 1957, when three institutions—Zion’s Savings Bank and Trust Company (1873), Utah Savings and Trust Company (1889), and First National Bank of Salt Lake City (1890)—merged to form Zions First National Bank. The combined institution opened this new chapter with $109.5 million in deposits. It also made a symbolic break with the past: the long-familiar apostrophe in Zion’s was dropped.

Just a couple of years later, another decision reshaped the bank even more. Leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints decided to divest their banking interests. On April 22, 1960, the Church sold majority control of Zions First National Bank to Keystone Insurance and Investment Company, owned by Leland B. Flint, Roy W. Simmons, and Judson S. Sayre. At the time, the bank had approximately $120 million in deposits.

That handoff—from church control to private ownership—marked the start of Zions’ modern era. And it introduced a name that would define the next sixty years of the institution’s life: Simmons.

IV. The Holding Company Revolution & Multi-State Expansion (1970s-1990s)

Roy W. Simmons was the kind of leader the twentieth-century West produced in bulk: self-made, relentless, and allergic to excuses. He was born January 24, 1916, in Portland, Oregon. By age eight, he’d lost his mother. Not long after, he lost his father too. Work wasn’t a virtue in Simmons’ world; it was the only option.

He started in insurance, but in 1940 he found his way into banking as a teller at First National Bank in Layton, Utah—and he rose fast. In 1949, he became the youngest state banking commissioner in the United States after being appointed to the role in Utah. He left that post in 1952 to organize the Bank of Utah in Ogden, and then moved into consumer finance as president of Lockhart Company in Salt Lake City.

Then came the pivotal moment. In 1960, Simmons and two partners bought controlling stock in Zions First National Bank from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Three years later, Zions and Lockhart merged to form Zions Bancorporation, and Simmons was soon elected chairman and CEO. He would run Zions Bancorporation and Zions First National Bank from 1964 until 1990, later retiring as chairman in 2002. He died on May 9, at age 90.

His tenure was an era of expansion with a clear throughline: grow steadily, stay disciplined, and build a bank that matched the scale of the West itself. Under Simmons, Zions expanded statewide and grew from about $150 million in assets in 1964 to more than $3 billion by 1986. In January 1966, Zions became a public company through an initial public offering—and it has paid a cash dividend to shareholders every year since.

But Zions’ most distinctive move was still ahead. Banking laws were changing, and the old rules that kept banks boxed inside state lines began to loosen. As out-of-state acquisitions became possible in the 1980s—especially in states with reciprocity laws—Zions built a strategy around the new reality. Zions Utah Bancorporation, later shortened to Zions Bancorporation in 1987, began to push beyond Utah, starting with Nevada and then Arizona. Alongside that shift, the next generation of leadership was coming into view: Harris H. Simmons was promoted to president of Zions Bank in 1986.

The first out-of-state step set the tone. In 1985, Zions purchased Nevada State Bank in Las Vegas. A year later it entered Arizona with the acquisition of Mesa Bank. By the mid-1990s, the pace picked up: in 1996, Zions expanded into Colorado and New Mexico by acquiring Aspen Bancshares, which operated Pitkin County Bank and Trust, Valley National Bank of Cortez, and Centennial Savings Bank.

The 1990s became a sprint. In March 1997, Zions acquired 27 branches in Arizona, Idaho, Nevada, and Utah from Wells Fargo. In July 1997, it acquired Tri-State Bank of Idaho. In September 1997, it acquired Vectra Banking Corporation and Tri-State Finance Corporation of Colorado for a total of $200 million.

What made this expansion unusual wasn’t just the geography. It was the structure.

Zions didn’t buy banks to erase them. It bought them and kept them local—names, leadership teams, community presence—while centralizing the machinery behind the scenes. The pitch was simple: let bankers make decisions close to their customers, but run the back office like a larger institution. Distinct local brands on the front end; shared infrastructure on the back end. That “collection of great banks” model became the company’s signature.

Then, in 1999, Zions took a swing that could have turned it into a very different company. It bid for First Security Corporation—an acquisition that would have been transformational. But Zions lost out to Wells Fargo after the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission required Zions to restate prior years’ results due to how it accounted for acquisitions. The deal died. The ambition didn’t.

Even without First Security, Zions emerged as the largest bank headquartered in Utah. And the episode left a mark internally. LeeAnne Linderman, who later retired as Zions’ director of retail banking, recalled that in meetings afterward, leadership didn’t dodge the loss. Simmons, she said, took full responsibility for the demise of the deal. “Any employee who has ever seen Harris speak understands his authenticity,” she said. “He tells it like it is.”

For Zions, the lesson was blunt: the multi-state strategy was real, the stakes were rising, and the bank was now operating on a national stage where execution—and accounting—had to be just as sharp as ambition.

V. The 2008 Financial Crisis: Near-Death and TARP (2008-2013)

CRITICAL INFLECTION POINT #1

When the 2008 financial crisis hit, it didn’t hit Zions evenly. It hit where Zions lived.

By design, the company had built itself around the fast-growing Southwest—Nevada, Arizona, and California. In the boom years, that concentration looked like foresight. In the bust, it turned into a magnifying glass. Housing collapsed hardest in exactly those places, and Zions’ book carried a heavy load of commercial real estate loans that started going delinquent.

The affiliate strategy suddenly had a dark side. Nevada State Bank was effectively at ground zero of the crash. California Bank & Trust was staring at serious commercial real estate stress. And because the pain was clustered, healthier pockets of the franchise couldn’t easily “average out” the damage.

So Zions did what many banks swore they wouldn’t do—until they had to. On October 27, 2008, it accepted a $1.4 billion investment from the U.S. government through the Troubled Asset Relief Program. Call it TARP. Call it a bailout. Either way, it was a lifeline—and it bought time.

Repayment took years, and it came in chunks. In March 2012, Zions repaid $700 million of the original $1.4 billion. By that point, the Treasury said it had also received $253 million in dividends, and it still held warrants to buy Zions common stock—extra upside the government expected to sell later. Zions still owed the remaining $700 million until September 26, 2012, when it redeemed the final TARP shares at full face value.

Harris Simmons, chairman and CEO, framed it as a turning point. The repayment, he said, would let the bank refocus on growing the business—while continuing to unwind the expensive funding and capital structures the crisis had forced into place.

But the bigger change wasn’t financial. It was cultural.

The crisis burned concentration risk into Zions’ operating DNA. Michael Morris, the bank’s chief credit officer, later said Zions systematically reduced commercial real estate exposure as a share of its total portfolio—from 33% in 2008 to 23% “today”—specifically to lower credit risk after the Great Recession.

In the end, the government made money on Zions. That was a vindication of the rescue on paper. For shareholders, it was still a brutal era—dilution, constrained returns, and years of cleanup. But the scars became a playbook. And fifteen years later, when the next banking panic arrived, Zions would be facing it with a very different set of instincts.

VI. Regulatory Gauntlet: Dodd-Frank, Stress Tests & The $50B Threshold (2013-2018)

CRITICAL INFLECTION POINT #2

Zions had barely finished cleaning up 2008 when the next wave hit—this time from Washington.

Dodd-Frank redrew the map for American banking. Under the law, any institution above $50 billion in assets could be treated as “systemically important” and pulled into a new world of enhanced supervision: annual stress tests, “living wills,” and higher capital and liquidity expectations. For the megabanks, that was the point. For regionals like Zions, it was a shock.

As Al Landon, an adjunct professor at the University of Utah’s David Eccles School of Business, put it: Dodd-Frank dropped the “big bank” threshold to $50 billion and effectively grouped banks like Zions together with institutions measured in the trillions. “That’s a huge range,” he said. Zions was at the small end of it—and suddenly had to play by rules designed for the biggest players in the country.

Then came the stress tests. And Zions didn’t just struggle—it stood out.

In the Federal Reserve’s review of 30 large, tier-1 institutions, Zions was the only bank that didn’t meet the minimum capital standards under the hypothetical “severely adverse” scenario. While 29 of 30 banks stayed above the key threshold through the Fed’s nine-quarter projection window, Zions’ Tier 1 common equity ratio dipped well below where it needed to be.

The result wasn’t just embarrassing. It was destabilizing—because Zions’ own internal models told a very different story.

“Our own models produced significantly different results,” Harris Simmons said on a conference call after the results. He insisted that under a truly severe downturn, even with no access to capital markets, Zions would remain “comfortably above” the required minimum for Tier 1 common equity relative to risk-weighted assets.

The bank pointed to what drove the gap: the Fed’s assumptions hit Zions with significantly higher projected commercial real estate losses, significantly greater risk-weighted assets, and lower projected revenue before provisions. And the details were painfully familiar: commercial real estate was again the villain. CRE loans alone were estimated to account for more than half of total losses in the Fed’s scenario.

In 2014—the first year Zions participated in the full CCAR exercise—it received a quantitative objection after falling below the minimum. In 2015, it improved, but only barely. Zions’ projected minimum Tier 1 common ratio came in just a hair above the standard, and analysts called it another disappointment, reinforcing the sense that the bank was stuck in the penalty box.

But Zions didn’t just try to model its way out. It pushed for rule changes.

A multi-year lobbying effort built toward a broader political shift: raising the asset threshold for the strictest oversight. The Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act—signed into law on May 24, 2018—lifted Dodd-Frank’s enhanced-prudential threshold, ultimately moving it far above where Zions sat.

And Zions went further still. The Financial Stability Oversight Council voted to grant an application by Zions Bank, N.A. to no longer be treated as a SIFI under section 117 of Dodd-Frank. Zions was the first bank to apply under that section—and the first to receive approval.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, who chaired the FSOC, laid out the argument in plain language: Zions had limited capital markets activity, minimal “fire sale” risk, a relatively simple operational structure, and was already heavily supervised. In the council’s view, Zions did not pose a meaningful threat to U.S. financial stability.

In the moment, it felt like liberation. But the bigger story is what the gauntlet forced Zions to become. The bank had to build the governance, risk infrastructure, and operational discipline to survive in a regulatory regime built for giants. And that work—painful, expensive, and often maddening—set up the next reinvention.

Because once you’ve rebuilt your bank to satisfy the Fed’s models, the natural question becomes: what else can you rebuild?

VII. Digital Transformation & Technology Leadership (2015-Present)

CRITICAL INFLECTION POINT #3

Once the regulatory gauntlet forced Zions to rebuild its risk and compliance muscles, management turned to a different kind of existential threat: the technology stack.

In 2013, Zions made a decision that would shape the next decade—replacing its core banking systems. The bank chose Tata Consultancy Services and its TCS BaNCS platform with a clear goal: standardize and centralize the plumbing across the enterprise, enable straight-through processing, and give the organization a single, unified view of customers rather than scattered snapshots trapped in different systems.

The scope was enormous, and the rollout came in stages. Zions tackled it in three phases: a consumer loan software upgrade completed in 2017; construction and commercial loan software that launched in 2019; and then the deposit platform, which went live in July.

It didn’t go the way the neat PowerPoint version always promises. The transformation took roughly three times longer than expected and cost more than originally planned. The board also structured the program with funding gates along the way rather than writing one blank check up front—forcing the project to prove progress before moving to the next phase.

And there was another problem: time. Technology doesn’t sit still while you modernize it. Between the second and third phases, Zions invested more than expected in things like APIs and data streaming—plumbing that customers never see, but that determines whether a bank can move fast in the modern world.

To make the new core workable, Zions also had to simplify the business itself. Years of acquisitions had left the company with multiple platforms servicing loans and deposits across seven regional brands. The transformation became a forcing function: Zions cut its deposit products from about 500 down to roughly 100 and standardized processes across branches and loan operations. At a high level, Harris Simmons said, it pushed the company to operate “as a single organization as opposed to a series of fiefdoms.”

Management framed it as more than maintenance. “We are making investments in technology that are game-changing, long-term and foundational,” said President and Chief Operating Officer Scott McLean. He argued that Zions, as a regional bank, had the financial capacity and management focus to do what many peers avoided: fully confront the burden of legacy systems—and come out with a technology position competitors would struggle to match.

Then came a real-world stress test no one planned for.

When COVID hit, the federal government launched the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program, essentially asking banks to stand up a massive, rules-heavy lending program almost overnight. Zions implemented the program and began providing relief in three days—an agility moment that made the years of core work feel less like a cost center and more like insurance. As of May 10, 2020, Zions said it had processed and obtained approval for 40,483 PPP loans totaling $7.05 billion, originated across its affiliate banks in 11 western states. The loans were heavily skewed toward the smallest employers: more than two-thirds went to businesses with fewer than ten employees, and most were for relatively small dollar amounts.

Inside the company, the takeaway was straightforward: modernization wasn’t just about efficiency—it was about speed.

As Scott Smith put it, Zions believed it would be a competitive advantage because every bank would eventually have to leave “mainframe-centric worlds.” Zions, he argued, had carried the burden early. For years, about half of its technology investment had been tied up in the core transformation. With that heavy lift largely behind them, the logic went, those dollars and that attention could shift from replacement to innovation—while competitors were still “kicking the can down the trail.”

Or, in Harris Simmons’ simpler framing: “So much of the transactional part of the business is taking place via phones, devices and the internet. We’re intent on, and committed to, doing that well.”

VIII. The Small Business & Commercial Banking Franchise

Zions’ modern identity revolves around a deceptively simple idea: win the small and mid-sized businesses of the Intermountain West. Not by trying to outspend the megabanks, but by becoming the bank that actually understands how local companies operate—and can move at their speed. Along the way, the bank has built a reputation that shows up in customer survey awards for small and middle-market banking, plus a strong standing in public finance advisory and Small Business Administration lending.

A big piece of that is SBA “preferred lender” status. In plain terms, it’s a badge the SBA gives to banks that have proven they can serve small businesses well. It also comes with real operating leverage: preferred lenders can approve loans, close them, and handle most servicing with less back-and-forth—so decisions happen faster.

And Zions isn’t just participating in SBA lending; it’s leading it in key home markets. In fiscal year 2024, Zions Bank ranked No. 1 in SBA 7(a) loan approvals in both the Boise and Utah Districts. SBA data also shows that in 2024, Zions Bank helped Utah and Idaho businesses expand in ways that supported job creation and job retention—868 new jobs and 1,544 retained. The borrowers, importantly, weren’t just giant local players. Average loan sizes were relatively modest: $191,275 in Idaho and $241,856 in Utah. Zions’ share was meaningful too, with its approvals representing more than 19% of 7(a) loans in the Boise District and 15% of the 1,154 7(a) loans in the Utah District during the last fiscal year. The bank also continued to market SBA loans to Utah and Idaho businesses owned by women and people of color.

This is where Zions’ relationship model becomes more than a slogan—it becomes a defense. For many small businesses, banking isn’t a one-click commodity. They need local knowledge, industry fluency, and quick answers. That’s a hard combination for centralized megabanks to deliver consistently, and it’s exactly the kind of day-to-day complexity fintech point solutions often avoid. Zions’ affiliate structure is designed to keep decision-making close to customers while still giving bankers the capital base and technology platform of a roughly $90 billion institution.

As Starks put it, “The story of Zions’ evolution is story of Utah’s evolution. I’ve learned over the years and in my career, if there’s anything really important taking place in the community, Zions is either leading or supporting that effort in a major way.” The bank’s fingerprints are everywhere.

IX. Modern Challenges & The 2023 Banking Crisis (2020-Present)

CRITICAL INFLECTION POINT #4

When Silicon Valley Bank collapsed in March 2023, Zions found itself in the blast radius. The fear wasn’t subtle: investors looked at “regional bank” tickers, assumed the worst, and hit sell.

Zions’ stock got caught in that wave. It dropped sharply as markets opened, trading was briefly halted amid the volatility, and by the end of the day the shares were still down materially. The message from the market was clear: guilt by association.

Management’s response was just as clear: Zions was not SVB, and it wasn’t Signature.

CEO John Turner Anderson pointed to the traits that made the failed banks uniquely fragile in a fast-rising-rate environment. Silicon Valley Bank and Signature, he said, had grown at extreme speed and built deposit bases concentrated in large, uninsured accounts—technology clients in one case, cryptocurrency in the other. Zions didn’t look like that. Its deposits were spread across roughly 1.4 million accounts, with balances that were overwhelmingly smaller than the typical SVB account. In a bank run, that granularity matters. It makes the institution harder to stampede.

And in the weeks after the panic, that argument started to look less like spin and more like signal. Executives said deposit trends stabilized after quarter-end. They also said Zions added more than 7,000 accounts between March 7—when the crisis atmosphere began to thicken—and March 31, totaling $629 million in new balances. At the same time, Zions emphasized another post-2008 scar turned into policy: it had spent more than a decade steadily reducing exposure to credit risk in commercial real estate, trying to avoid the same kind of concentrated pain that nearly broke it during the Great Recession.

The reputational fight wasn’t only against the market. It was against narratives. “We’re on record saying that we felt the Moody’s downgrade was inconsistent with the financial condition of our company,” Abbott said. And the bank tried to show confidence in the most concrete way possible: regulatory filings showed Zions executives buying shares during the selloff, close to $2 million in total, which Abbott confirmed after The New York Times reported it.

In that sense, the 2023 panic validated Zions’ conservative rewiring since 2008. But it also underscored a hard truth about modern banking: even if your balance sheet is built for the storm, the storm can still hit your stock.

Then, in late 2025, Zions faced a very different kind of test—one that didn’t come from depositors, but from credit. In a Thursday regulatory filing, the bank disclosed it believed there were misrepresentations by certain borrowers tied to its California Bank & Trust unit. Zions recorded a $60 million loss provision and a $50 million charge-off in its third-quarter results. Around the same time, Western Alliance Bancorp alleged fraud against a borrower in a separate lawsuit—another reminder that in commercial banking, risks don’t always announce themselves as macroeconomic cycles. Sometimes they show up as one bad counterparty.

Analysts largely treated Zions’ issue as contained. Raymond James called the disclosure a “one-off credit hiccup,” not a broader sign of systemic deterioration.

And the quarter’s results reinforced that view of a bank still generating solid earnings power. Zions reported third-quarter 2025 net earnings applicable to common shareholders of $221 million, or $1.48 per diluted common share, compared with $204 million, or $1.37 per diluted common share, in the third quarter of 2024.

Harris H. Simmons, Chairman and CEO of Zions Bancorporation, said, “We’re pleased with the Company’s core earnings,” pointing to growth in pre-provision net revenue, an improved net interest margin versus the prior year period, and higher customer-related noninterest income after adjustments.

The pattern is the throughline of the modern era: Zions keeps getting pulled into industry-wide storms—by regulation, by technology, by panic—and then has to prove, again, that its fundamentals are built to hold.

X. Strategic Positioning & The Path Forward

Leadership continuity has been one of Zions’ quiet superpowers. Harris H. Simmons has served as Chairman since 2002 and as President and Chief Executive Officer since 1990—an almost unheard-of run in an industry where CEOs are often rotated in and out with the credit cycle.

Simmons’ influence hasn’t been limited to Zions’ headquarters. He has chaired the American Bankers Association and is a member of the Financial Services Roundtable. In Utah, he’s also been deeply embedded in civic life—serving as chairman or president of organizations including the Utah Symphony, the Utah Foundation, the Salt Lake County Zoo, Arts and Parks Campaign, the Economic Development Corporation of Utah, and the Utah Board of Higher Education.

But the bigger point isn’t the résumé. It’s what he chose to do with the power and the runway.

As regulation tightened and customer behavior moved to phones and browsers, Simmons took a hard look at the very structure that had made Zions distinctive: its decentralized model. Over time, he pushed the organization toward more standardization and streamlining. He later went a step further by shedding the consolidated bank’s holding company. And he greenlit the kind of core-systems modernization that most banks postpone for as long as they can—an overhaul that became one of the most ambitious technology projects in large U.S. banking. “He’s a leader that leans into the really tough decisions,” said Scott McLean, Zions Bancorp.’s president and chief operating officer.

Now, you can see succession planning moving from theory to reality.

Paul Burdiss joined Zions Bancorporation in 2015 as Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, holding that role until he moved into his current position at Zions Bank. His career spans more than 35 years in financial services, including roles at SunTrust Bank and Comerica.

When Burdiss shifted roles, Simmons announced his successor: Nathan Callister, then Executive Vice President and Executive Director of Commercial Banking at Zions Bank. Before Zions, Callister worked at Wells Fargo Bank, where he served as Executive Vice President and Market Executive for Commercial Banking in Idaho. He’s a BYU and University of Southern California graduate, and—like many Zions leaders—has been active in community affairs.

XI. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

By now, the pattern should feel familiar: Zions keeps coming back to the same bet—stay focused on the West, win with relationships, and let scale show up behind the scenes. In the third quarter of 2025, that playbook produced net earnings applicable to common shareholders of $221 million, with total assets of $88.53 billion as of September 2025. The point isn’t that those numbers are “impressive.” The point is that they’re the output of a business model that’s been refined through crisis, regulation, and reinvention.

Start with the engine room: net interest margin. Zions makes most of its money the classic bank way—earning the spread between what it pays depositors and what it charges borrowers. A NIM of 3.28% in Q3 2025 signals a bank that’s still getting paid for taking credit and duration risk, even in a competitive deposit market. And because Zions is relatively asset-sensitive, higher rates can be a tailwind: loans tend to reprice faster than deposits. But it’s never automatic. As deposit competition heats up, funding costs climb, and that spread can narrow fast.

Then look at what the bank chooses to lend against. Zions’ portfolio is built around commercial and industrial lending, commercial real estate, small business banking, and consumer loans—exactly the categories you’d expect from a bank that wants to be embedded in the day-to-day life of Western companies. The post-2008 scar tissue shows up here too. Zions has deliberately pushed down its commercial real estate concentration over time, trying to avoid getting trapped again by one asset class in one geography. CRE is still meaningful, but the posture is visibly more cautious than it was heading into the Great Recession.

You can see the broader earnings power in other recent metrics as well. In early 2025, the bank reported a net interest margin of 3.12% and an annual return on tangible common equity of 13.9%. And the value creation story isn’t just in quarterly profits—management also pointed to tangible book value growing 17% year-over-year, a signal that the franchise has been compounding equity rather than simply surviving.

Finally, there’s the structure that makes Zions feel different in the market: the affiliates. Keeping local brands buys trust, community identity, and continuity—things that matter when your customers are business owners, not just account numbers. But it also comes with real friction: seven brand identities mean more marketing spend, more management overhead, and more operational complexity than a single national brand would carry. The core banking overhaul was, in part, an attempt to get the best of both worlds—local faces out front, standardized products and processes underneath.

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Regional banking is a knife fight. In every Zions market, it goes up against the national giants—JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo—plus sharp regional players like Western Alliance and a dense network of credit unions that benefit from tax advantages. Then there’s the fintech swarm: point solutions in payments, treasury management, and lending that can skim the most profitable parts of the relationship. For Zions, the main defense is the same one it’s leaned on for generations: keep the primary relationship, and the products tend to follow.

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

A banking charter is still a moat—regulation makes it hard to start a bank the old-fashioned way. But technology has changed what “entering banking” even means. Neobanks like Chime have shown you can reach millions of customers without branches, and the fintech ecosystem increasingly turns traditional banks into back-end utilities. And looming over the whole category is Big Tech: companies with massive customer bases, distribution, and data that could decide to get serious about financial services at any time.

Supplier Power: LOW-MODERATE

A bank’s key input is deposits, and the 2023 turmoil made clear how quickly competition for them can spike. On the infrastructure side, big technology vendors—especially core banking providers—have leverage because switching is expensive and painful. And the scarcest supplier of all is talent: engineers, data specialists, and risk professionals are in demand everywhere, and regionals like Zions are competing not just with other banks, but with tech companies too.

Buyer Power: MODERATE-HIGH

For consumers, digital banking has made switching easier. The friction that used to come with moving accounts keeps shrinking. Commercial clients are different: operating accounts, treasury management setups, and credit relationships create real stickiness. Small businesses also tend to value speed, expertise, and continuity over squeezing out the last basis point. Still, the internet has turned pricing into a comparison sport, and customers can shop more easily than ever.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Banks no longer have a monopoly on lending or payments. Non-bank lenders, private credit funds, and online platforms can step in where banks used to be the default. Payment processors like Square, Stripe, and PayPal have carved out transaction revenue that once ran through banks. And Big Tech’s push into finance—Apple’s savings account, Google Pay, Amazon lending—shows how the relationship can get disintermediated. For larger customers, direct access to capital markets adds another escape hatch: when the company gets big enough, it can sometimes bypass the bank entirely.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Zions has real regional scale in the Intermountain West, but it doesn’t enjoy the unit-cost advantages of a national giant. At around $89 billion in assets, it sits in an in-between zone: big enough to carry serious fixed costs—especially in risk, compliance, and technology—but not big enough to spread those costs like a trillion-dollar bank can. That’s why the multi-year technology overhaul matters so much. It’s essentially a wager that better infrastructure can deliver “big bank” efficiency without needing “big bank” size.

Network Economies: WEAK

Banking isn’t a classic network business. Zions can build some network-like pull through treasury management tools and B2B payment rails, where integration and usage reinforce the relationship. And, in tight-knit Western markets, reputation can compound through referrals. But that’s not the same thing as true network effects where every new user makes the product structurally better for all users.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK

There’s nothing about Zions’ relationship-banking approach that a national bank couldn’t replicate if it truly wanted to. The affiliate structure is a strategic choice, not a protected fortress. Where Zions does get some counter-positioning is against pure digital players: a branch footprint and banker-led service can still matter when you’re dealing with operating accounts, cash flow timing, payroll, and credit decisions. The risk is obvious, though—every year, technology gets better at mimicking “personal,” and the advantage narrows unless Zions keeps raising its game.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG

This is the closest thing Zions has to a durable power. Commercial relationships are sticky because they’re woven into the customer’s operations: treasury management setups, payment workflows, operating accounts, covenants, lines of credit, and the human relationships that smooth the rough edges when something breaks. For small businesses, switching isn’t just annoying—it can be genuinely disruptive. Consumers can move more easily, but even there, direct deposit, bill pay, and auto-pay routines create enough friction to slow churn.

Branding: MODERATE

Zions’ affiliate brands have earned real trust in their home markets. Names like Zions Bank, Nevada State Bank, and California Bank & Trust carry decades of local credibility. But banking brand power has a ceiling. Most customers aren’t willing to accept meaningfully worse rates or terms just because they like a logo. Trust matters; premium pricing, usually, doesn’t.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

The most tangible resource advantage is the deposit franchise in fast-growing Western markets. Distribution still matters in banking, and branch networks in the right metros are expensive to build and slow to replicate. Add in management and underwriting expertise in regional industries—mining, energy, agriculture, and increasingly technology—and you get a real, practical edge. It’s valuable. It’s not untouchable.

Process Power: MODERATE

Process power is where Zions has been trying to compound its hard-earned lessons. A credit culture built over 150 years, a relationship model that keeps decisions closer to customers, and a modernized core that lets the bank operate more like “one organization” all add up to an advantage versus peers still tangled in legacy systems. But process power is never permanent. In banking, yesterday’s best practice turns into tomorrow’s baseline faster than anyone wants.

Overall Assessment:

Zions has moderate moats—strongest in switching costs and in the cornered resource of a sticky deposit base across attractive Western markets. It’s not a wide-moat business. But it is a defensible franchise, and its path forward is clear: keep building process power through technology while protecting the relationship model from two directions at once—scale-heavy national banks on one side and fast-moving digital disruptors on the other.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

Zions looks like a regional bank built for the right ZIP codes. The Intermountain West has been one of the country’s most consistent growth engines, and states like Utah, Idaho, Arizona, Nevada, and Colorado have combined faster-than-average population gains with business-friendly environments. Just as important, the economic base in many of these markets has broadened over time—less tied to a single resource cycle, more anchored in services and technology—giving Zions more ways to win than the old boom-or-bust West.

The tech bet is also starting to look less like a cost and more like an edge. After years of painful core modernization, management has argued that a much larger share of technology spend can now go toward new capabilities instead of keeping legacy systems alive. The PPP moment during COVID was the proof point: Zions stood the program up in days, at a speed many banks couldn’t match, because the underlying plumbing was finally getting modern.

Then there’s the deposit franchise—tested, loudly, in 2023. While the market lumped all regionals together, Zions’ deposit base behaved very differently from the concentrated, uninsured profiles that doomed banks like SVB and First Republic. With roughly 1.4 million accounts and generally smaller balances, the franchise is harder to stampede. In the middle of the panic, Zions said it added accounts and balances—exactly what you’d expect from a relationship bank in a moment when trust suddenly matters again.

Put those pieces together and you get the classic bull setup: a bank with improving fundamentals that still often trades like the market hasn’t fully forgiven the category. If regional bank consolidation accelerates, Zions could benefit as weaker competitors merge, shrink, or exit. And if rates stay higher, Zions’ relatively asset-sensitive balance sheet can help sustain earnings power. In that world, the “collection of great banks” model—local relationships on top of a shared platform—starts to look like a durable way to compete against both megabanks and fintech point solutions.

Bear Case

The same focus that makes Zions distinctive is also its biggest risk: concentration. If the West gets hit—by a real estate downturn, a tech slowdown, or even region-specific shocks like drought—Zions doesn’t have a Midwest or Southeast franchise to offset it. And the demographic growth that makes these markets attractive is also an invitation for competition. The national banks want the same customers, and digital players can target them without building branches.

Scale is the other structural headwind. As banking becomes more software-driven, the gap between institutions that can spend endlessly on technology and those that can’t may widen. Zions has modernized its core, but “finished” isn’t a concept in bank technology. Staying competitive requires constant reinvestment, and the industry leaders operate with budgets that can make a regional bank’s roadmap feel like a rounding error.

Fintech pressure lands right on Zions’ strengths. Payments, treasury management, and small business lending are precisely where new entrants try to unbundle profit pools. And while Zions has reduced commercial real estate concentration since 2008, CRE is still meaningful, with office-related stress an ongoing source of uncertainty. Add in the fact that interest rate sensitivity can flip from tailwind to headwind—rate cuts in a recession could compress margins—and you have a model that can look very different depending on the macro.

Even the branch network cuts both ways. Physical presence supports relationship banking, but it’s expensive, and customer behavior keeps shifting online. That makes efficiency a lingering question. If pricing power is limited and banking remains a commodity in many products, the path to better returns often runs through cost discipline—yet the bank also has to keep spending to stay technologically relevant. And with a depressed stock price, using equity as acquisition currency gets harder, reducing strategic optionality right when the industry could be entering a new wave of consolidation.

XV. Key Metrics & What to Watch

Net Interest Margin (NIM): This is the heartbeat of a traditional bank. Zions’ NIM was 3.28% in Q3 2025, helped by a more favorable rate environment. The tell going forward is whether deposit costs keep creeping up. If the margin expands, it usually means Zions is holding pricing power. If it compresses, competition for deposits or a shifting rate backdrop is squeezing the spread.

Efficiency Ratio: The clearest scoreboard for whether all that technology spending is paying off. Zions has aimed to move from the mid-60s toward the high 50s over time. This ratio is simply non-interest expense divided by revenue—lower is better. The story to watch is operational leverage: are the modern systems actually letting the bank grow without adding the same amount of cost?

Non-performing Assets Ratio: The early-warning light on credit. It stood at 0.50% of total loans in Q4 2024, which suggests problems were still contained. But this is the metric that can turn before earnings do, especially if the economy softens. And after the recent fraud-related charge-off, investors will be looking hard for any sign it’s more than a one-off.

Return on Tangible Common Equity (ROTCE): The bottom-line “are we creating value?” measure. Zions posted 13.9% in early 2025, with a long-run goal of sustaining 15% or better. Through cycles, this is the metric that tells you whether the franchise is truly earning its keep—or just surviving.

XVI. Epilogue: What's Next for Regional Banking?

The existential question hanging over Zions—and every peer in its weight class—is simple: is there a future for a roughly $90 billion regional bank?

Historically, the industry has offered two obvious answers. One is to scale up through mergers until you’re big enough to spread technology and compliance costs like the giants do. The other is to specialize so deeply in a niche that size matters less. Zions is trying to thread a needle between them: relationship banking, rebuilt on top of a modern technology stack. The wager is that “local and personal” doesn’t have to mean “expensive and slow,” as long as the plumbing underneath is strong enough.

Smith captured the mood this way: We are now entering growth markets where we expect that we're going to be able to acquire banks at a rate that we haven't seen in, okay, well over a decade.

But even if the M&A window opens, there’s a deeper generational question that will shape everything: will Gen Z and Gen Alpha value local banking relationships at all? The instinctive answer is no. Digital natives expect instant account opening, transparent pricing, and an app that works. They don’t want “their banker.” They want their problem solved.

And yet commercial banking is where that logic breaks down. A small business owner who needs working capital next week isn’t just clicking “add to cart.” A real estate developer juggling draws, inspections, and timelines isn’t looking for a chatbot. A manufacturer dealing with international receivables isn’t shopping for a pretty interface. These are messy, high-stakes workflows where speed matters, judgment matters, and context matters. Technology can make those relationships faster and cleaner—but it rarely replaces them outright.

That’s why Zions has kept insisting that even in an era of nonstop digital transacting, the business is still built around people. Harris Simmons has argued that branches—and the teams inside them—create connections that extend beyond financial products and into the fabric of the communities they serve. In other words: the app can win the transaction, but the relationship can still win the customer.

The ownership question, though, is still open. Will Zions remain independent? Its Western footprint and deposit base are exactly the kind of assets a larger bank could covet. Private equity has also shown growing interest in banking assets. Zions’ long leadership continuity has helped it stay its own company. But succession—by definition—creates moments when the industry starts to ask whether that independence is a permanent identity or just the current chapter.

Then there’s the West itself. Climate and the resource economy will shape risk in ways traditional bank models weren’t built to price. Water scarcity, wildfire exposure, and the energy transition can create real credit pressure, especially in agriculture and other resource-dependent sectors. At the same time, they can create new demand: infrastructure investment, clean energy projects, and modernization across everything from utilities to real estate.

So what does “winning” look like by 2030? In Zions’ own framing, it’s a technology-enabled relationship bank that can generate strong through-cycle returns, build leading share in small business and commercial banking across growing Western markets, and keep strategic options open—whether that means staying independent or becoming valuable enough to command a premium.

And that brings the story full circle. Zions Bancorporation is a uniquely American institution: pioneers, boom-and-bust cycles, and reinvention across generations. From Brigham Young’s July 1873 meeting to a bank trying to compete in the AI era, it has survived by adapting to whatever the era demanded—without abandoning the idea that geography and relationships can still be strategy. Whether that formula can last another 150 years depends on what Zions chooses to build next.

XVII. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper, these are the best places to hear the story in the bank’s own voice, see how regulators and journalists framed the inflection points in real time, and understand the broader forces reshaping regional banking.

Top 10 References:

- Zions Bancorporation Annual Reports (2008, 2013, 2018, 2024) - The clearest record of what changed, when it changed, and how management explained it.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City: "The Future of Regional Banks" research papers - Great context on why regionals are squeezed between megabanks, fintech, and regulation.

- American Banker coverage of the 2023 banking crisis - A useful day-by-day view of how the panic spread and how banks responded.

- Zions investor presentations (especially post-2018) - Where the strategy gets packaged: technology, business mix, and the “collection of great banks” logic.

- "The Banker's New Clothes" by Anat Admati & Martin Hellwig - A solid foundation for understanding bank capital and why it matters in every crisis.

- FDIC Historical Banking Statistics - The long lens: failures, consolidation, and how the U.S. banking map has changed over time.

- Utah and Intermountain West economic development reports - Helpful for understanding the growth dynamics Zions is betting on.

- McKinsey & BCG reports on digital banking transformation - Broad industry benchmarks for what “modernizing a bank” actually entails.

- The Financial Brand coverage of Zions' core transformation - A closer look at the guts of the technology journey and what it took to execute.

- Bank Director magazine: Small business banking issue - Good reporting on why small business banking works when it’s done well—and why it’s hard to copy.

Historical Sources: - "Banking in the American West" by Lynne Pierson Doti and Larry Schweikart - Leonard Arrington's work on Mormon economic history - Zions Bank 150th Anniversary History Book (available through Zions Bank) - FDIC case studies on bank failures during 2008-2009

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music