Dentsply Sirona: The Story of Dental Technology's Troubled Giant

I. Introduction: When Two Dental Empires Collided

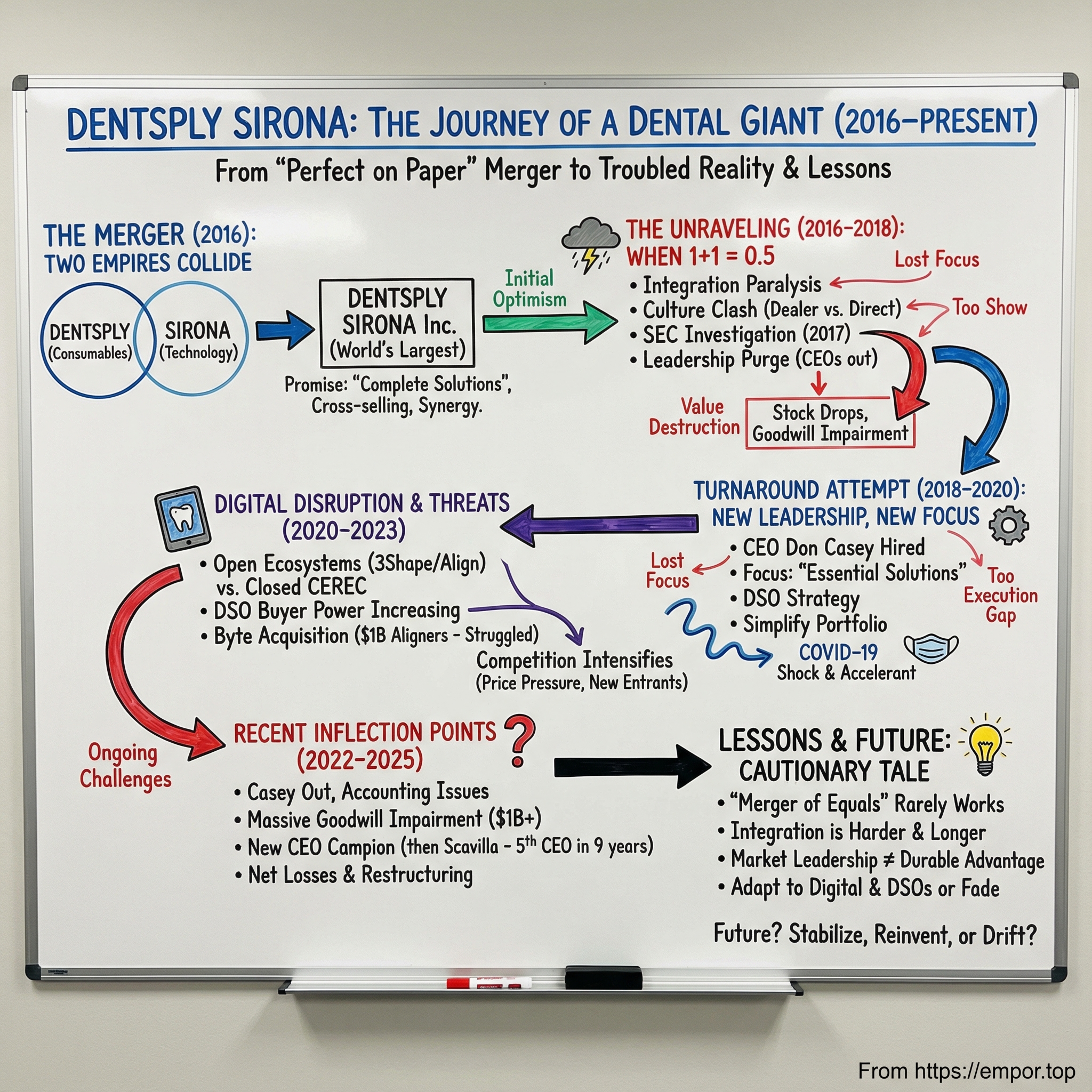

Picture the scene: February 29, 2016. A leap day on Wall Street, and the kind of date bankers love because it feels like history is being made. The merger closes. DENTSPLY International and Sirona Dental Systems officially become DENTSPLY SIRONA Inc.—the world’s largest manufacturer of professional dental products and technologies, spanning everything from everyday consumables to high-end equipment and digital workflows.

The pitch was simple and seductive. Dentsply owned the recurring-revenue basics dentists burn through every day. Sirona owned the future: digital dentistry, premium equipment, the tech-forward systems that could reshape how care gets delivered. Put them together and you don’t just have a bigger supplier—you have a platform. The dental equivalent of an ecosystem, where the products reinforce each other and the customer never wants to leave.

Jeffrey T. Slovin, the newly minted CEO, framed it as a turning point: “With our merger complete, Dentsply Sirona can now focus its efforts on empowering dental professionals to provide better, safer and faster dental care. As The Dental Solutions Company, we will drive long-term growth by being uniquely positioned to deliver innovative solutions.”

On paper, it was elegant: equipment plus consumables equals lock-in. Cross-selling would be natural. Cost synergies would be inevitable. Scale would do what scale always does—make the leader even harder to catch. Analysts cheered the idea of a company that could serve a dentist from chair to crown.

But the story investors thought they were buying in 2016 is not the story that played out.

By the end of 2025, Dentsply Sirona’s market value had fallen to roughly $2.24 billion. The stock was around $11.22, miles below its past peaks. The company cycled through four CEOs, endured SEC scrutiny and accounting issues, and took billions in goodwill impairments. The “merger of equals” that was supposed to be straightforward turned into a nearly decade-long effort to stitch together two organizations that didn’t want to behave like one.

So how did two century-old leaders—each dominant in its lane—combine into a roughly $4 billion revenue giant that seemed to start coming apart almost immediately?

That’s the cautionary tale here: the hidden traps of “mergers of equals,” the brutal difficulty of innovating inside entrenched industries, and the kind of hubris that shows up when market leadership gets mistaken for durable advantage.

This is the story of Dentsply Sirona—and the lessons go far beyond dentistry.

II. The Dentsply Story: From Denture Teeth to Dominant Supplier (1899–2000s)

In 1899, in New York City, three entrepreneurs—Dr. Jacob Frick Franz, John Sheppard, and Dean Osborne—sat down in the office of Lewis Fawcett, Commissioner of Deeds, and incorporated a new business: The Dentists' Supply Company. They set it up for 50 years, put in $10,000 of capital (about $378,000 today), and aimed squarely at a problem that was everywhere in turn-of-the-century dentistry: people were losing teeth, and replacements were crude.

Their early product focus was simple, unglamorous, and enormous: artificial teeth.

Not long after the founding, a fourth figure joined who mattered just as much as the three names on the paperwork. George H. Whiteley was a ceramicist, and he brought the kind of technical edge that turns a supplier into a brand. He helped develop a patented process that used platinum rings to make teeth more durable and less prone to breaking. It’s an early signal of what would become Dentsply’s defining habit: win with manufacturing quality and repeatability in a field that had long been part craft, part improvisation.

The Dentists’ Supply Company also pushed standardization—specifically, creating a systematic relationship between facial shape, tooth size, and denture tooth form. That sounds academic, but it mattered in practice: it made outcomes more predictable, and it made mass manufacturing possible. This was the template for the next century—take something dentists did in bespoke, inconsistent ways, and industrialize it.

Just as important as what they made was how they sold it. The company leaned early into distribution, and a key partnership with E. de Trey & Sons helped market products across Europe and the United States. In a market made up of thousands of independent dentists, distribution wasn’t a back-office detail. It was the battlefield. If you controlled the channel, you controlled access.

After World War II, demand surged and the company expanded internationally, building manufacturing and research capacity abroad. High American tariffs and a push to gain share overseas—especially in Europe and Australia—pulled them outward. Dentsply was learning to behave like a global operator long before “globalization” became a business buzzword.

The 1950s and 1960s were a fertile period for product innovation. The company introduced the Airotor, an air-powered turbine handpiece that could spin at 2,500 rpm. That leap in speed changed the day-to-day feel of dentistry—faster procedures, more precision, and a clear message to dentists: this company wasn’t just selling supplies, it was shaping the work itself. Around the same era, it developed products and ideas that still echo in modern dental equipment, including the Dentsply Cavitron tooth-cleaning machine and Neolux, which improved the finish of plastic teeth.

In 1969, the company renamed itself Dentsply International, reflecting a shift in identity: the brand name had become more recognized than the corporate name, and the business was no longer just a supplier—it was becoming an institution.

Then came the acquisition engine. Through the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, Dentsply steadily added companies and categories, including LD Caulk Company (1963), Ransom and Randolph Company (1964), and F&F Koenigkramer Company. The biggest move of that era was Amalgamated Dental Industrial in 1976—once a distributor that had helped fuel early growth, and by then a powerhouse that controlled Australia’s largest dental supply chain.

By the late 1980s, Dentsply had refined a roll-up playbook: buy regional players, fold them into a standardized portfolio, use greater scale to drive manufacturing efficiencies, and then use expanded distribution to sell more of everything, everywhere. One milestone came in 1993, when Gendex Corporation acquired Dentsply International Inc. for $590 million—a deal that underscored how valuable the platform had become.

Running underneath all of this was a quietly brilliant business model: razor and razor blades. Dentsply partnered aggressively with dental schools so students trained on Dentsply products from day one. And dentists, like most professionals, tend to stick with what they learned on—especially in consumables where “feel” and habit matter. That created decades of recurring revenue in categories like impression materials, endodontic files, and restorative products.

Even as its roots were in consumables, Dentsply kept moving into higher-value specialties. In June 2011, it acquired Astra Tech—then the world’s third-largest maker of dental implants—from AstraZeneca for $1.8 billion. It was a statement: Dentsply wanted more than steady consumables cash flow; it wanted growth and margin expansion in premium categories.

By the time merger conversations with Sirona began, Dentsply had built an enviable franchise: a global manufacturing footprint, deep relationships through dental schools, and distribution reach into virtually every dental practice in the developed world. Revenue was approaching $3 billion and cash flow was consistently strong.

But the core market was mature, and growth had slowed. Management could see where the energy was going: digital dentistry. And to truly compete there, Dentsply didn’t just need new products. It needed a partner with a credible technology platform.

III. The Sirona Story: German Engineering Meets Digital Dentistry (1877–2000s)

While Dentsply was building its consumables empire in America, a very different story was unfolding in Erlangen, Germany.

Sirona’s roots trace back to 1877, inside a culture that treated manufacturing like a craft and engineering like a point of pride. Precision wasn’t a marketing word here. It was the whole identity. From the beginning, the organization that would eventually become Sirona had one instinct: spot new technology early, then make it real for dentists.

That innovation streak showed up fast. Under the direction of an RGS precision engineer in Erlangen, William Niendorff built an early electric-powered dental drill—then didn’t stop at invention. It moved into industrial production. The pattern was already set: take something novel, make it reliable, and scale it.

Then came an almost unbelievable historical footnote. In 1895, X-rays are discovered. Three days later, RGS co-founder Max Gebbert reaches out to Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, the physician behind the breakthrough. Within months, RGS becomes the first company manufacturing X-ray tubes and related apparatus—producing what’s described as the world’s first commercial X-ray unit. Dentistry had a new superpower, and this company was determined to be the one that packaged it for everyday use.

Over time, Siemens & Halske acquired a majority stake in RGS, bringing the business into one of Europe’s most formidable industrial empires. With Siemens’ backing, the dental operation kept pushing upmarket. In 1956, the Siemens SIRONA dental treatment unit launched—marking the first appearance of the “Sirona” name—and it was followed by a steady cadence of high-end treatment centers and chairs that cemented a reputation for premium equipment. Siemens Reiniger Werke AG established a production facility in Bensheim, Germany, which remained a key site and later became home to Dentsply Sirona’s Center of Innovation.

But the most important leap wasn’t a chair or a handpiece. It was digital.

In September 1985, at the University of Zurich Dental School, Dr. Mörmann placed the first chairside ceramic restoration using the CEREC 1 system—computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing applied directly to restorative dentistry.

CEREC—short for CEramic REConstruction—was a genuine break from the old world. Introduced commercially in 1987, it paired digital scanning with a milling unit, allowing dentists to make restorations from ceramic blocks in a single visit. The pitch sounded almost ridiculous at the time: scan the tooth, design the restoration, mill it right there, and fit it immediately. No physical impressions. No lab turnaround. No second appointment.

And yet, the “crazy” bet turned out to be prophetic. CEREC didn’t just speed things up; it rewired the workflow of restorative dentistry. The platform kept evolving: CEREC 2 arrived in 1994, expanding what could be produced to include inlays, onlays, crowns, and veneers. In 2000, the Windows-based CEREC 3 debuted—another step toward making this feel less like a science project and more like a mainstream tool.

Corporate structure caught up to the technology. On October 1, 1997, Sirona Dental Systems GmbH was established after Siemens decided to sell its dental systems division to a consortium of institutional investors coordinated through Schroder Ventures. The management buyout gave Sirona a singular focus: dental technology, and nothing else.

Through the 2000s, Sirona kept stacking pieces of a digital ecosystem. In 2009 it introduced CEREC AC, a digital impression unit powered by the CEREC Bluecam 3D camera. The company expanded further through a merger with Schick Technologies Inc., and its common stock was listed on NASDAQ under the ticker SIRO.

By the early 2010s, the product cadence was relentless: ORTHOPHOS XG 3D for 2D and 3D imaging, the SINIUS treatment center line, the powder-free CEREC Omnicam for color 3D full-jaw acquisitions, and the Schick 33 intraoral sensor.

By 2015, Sirona had built something rare in dentistry: a true technology platform. CEREC was a centerpiece of chairside CAD/CAM. Its imaging systems were widely regarded as best-in-class. And most importantly, once a practice committed to the workflow—and invested heavily in the system—switching wasn’t just expensive. It was disruptive. Training, process, and muscle memory all locked customers in.

The financial profile matched that position: operating margins above 20%, consistent growth, and a customer base that behaved more like a community than a market.

But Sirona’s leaders also understood the tradeoff. They sold capital equipment—big-ticket purchases that practices replaced infrequently. The business could be strong and still feel lumpy. To smooth that curve, they needed either more customers or more categories.

And when they looked across the Atlantic at Dentsply’s consumables engine—products practices reorder constantly—they saw the complement they didn’t have.

Two old-line leaders, each dominant in its niche, each wanting what the other had. The stage was set for a merger that, at least in the pitch deck, looked inevitable.

IV. The Merger Logic: Creating the "Complete Solutions Provider" (2015–2016)

The pitch was irresistible: Dentsply’s everyday consumables—impression materials, prosthetics, endodontic files—paired with Sirona’s high-end digital stack—CEREC systems, 3D imaging, treatment centers—would create the one company in dentistry that could truly do it all. A market leader in supplies plus a market leader in technology. In the press-release version of reality, that meant an unstoppable force and one of the world’s largest, most diversified manufacturers of professional dental products and technologies.

The strategic logic felt airtight. Sell a dentist a CEREC system and you don’t just win an equipment sale—you pull an entire workflow into your orbit. Those dentists would need ceramic blocks and other consumables. Dentsply’s huge commercial footprint could introduce Sirona’s equipment to practices that had never seriously considered it. The combined R&D engine would speed up innovation. Manufacturing synergies would lift margins. Together, they’d offer what rivals couldn’t: a complete, integrated dental solution from chair to crown.

They also sold the merger as a meeting of two long histories. Each side brought more than a century of experience, and together the company would have an R&D platform of over 600 scientists and engineers aimed at developing better dental care.

But the deal mechanics carried a quieter message: this wasn’t an acquisition. It was a “merger of equals,” the kind of structure that sounds diplomatic and often turns into shared-control gridlock. Bret W. Wise, Dentsply’s chairman and chief executive officer, would become executive chairman of the combined company. Jeffrey T. Slovin, Sirona’s president and chief executive officer, would become CEO and join the board.

A split like that is supposed to keep everyone happy. In practice, it can do the opposite. Power gets divided, accountability gets blurry, and hard integration calls start to look like political negotiations between two camps with different instincts, incentives, and definitions of success.

The financial terms reflected the same balancing act. Sirona shareholders would receive 1.8142 shares of Dentsply Sirona for each Sirona share—an exchange ratio that baked in Sirona’s premium valuation, driven by its higher growth and margins, and set correspondingly high expectations for what the combined company would deliver.

On day one, the new organization had about 15,000 employees across more than 40 countries. The spreadsheet assumed they would combine neatly. Real life rarely does.

The cultural gap was big, and it was easy to underestimate. Dentsply was American, commercial and sales-driven, with deep roots in dealer relationships and a culture built around moving product through distribution. Sirona was German, engineering-driven, built around technical excellence and innovation. Dentsply’s world revolved around the channel. Sirona’s revolved around the machine. Those aren’t just different operating styles—they’re different philosophies about how you win.

Slovin, speaking after shareholders approved the merger, struck the confident note everyone wanted to hear: “With the strong support of our shareholders, we are now focused on completing the transaction, successfully integrating the businesses and realizing the combination's full value creation potential.”

Wall Street bought it. Analysts modeled major cost and revenue synergies. The stock responded. The assumption was simple: if you combine two leaders, the whole should be bigger than the parts—1+1 equals 2, maybe even 3.

They were wrong.

V. The Unraveling: When 1+1 Equals 0.5 (2016–2018)

The problems didn’t take quarters to show up. They showed up immediately.

Inside the company, integration quickly turned into paralysis. The sales organization—supposed to be the biggest lever for cross-selling—became the first point of failure. The combined company now had two fundamentally different ways of selling sitting on top of each other: Dentsply’s world of dealer-driven, high-frequency consumables, and Sirona’s world of high-touch, high-ticket equipment that often required demos, training, and service. Incentives didn’t line up. Territories didn’t line up. And instead of a clear playbook, reps ran into confusion: Which products mattered most? Who got credit? Who owned the account?

Meanwhile, the dealer channel that had powered Dentsply for decades started pushing back. Distributors like Henry Schein and Patterson had long relationships with Dentsply on consumables, but many didn’t want to become equipment specialists overnight. Bundles were especially fraught. Dealers complained they couldn’t compete when Sirona’s equipment was also being sold through a direct sales force. What had been framed as “one unified go-to-market” felt, in practice, like being squeezed from both sides.

With the channel tense and the salesforce disoriented, leadership should have stepped in and made hard calls. Instead, the “merger of equals” structure turned most decisions into internal diplomacy. Systems didn’t get unified. Cultures didn’t blend. Strategy discussions became factional negotiations between legacy Dentsply and legacy Sirona. And the synergies that had looked so clean in the model—like the roughly $150 million in cost savings promised by 2018—kept slipping further into the distance.

Then the situation got worse, and it got public.

On August 9, 2017, the company disclosed in a filing that it was cooperating with an SEC investigation. Years later, in December 2020, it said it had reached a settlement. The SEC stated that, “without admitting or denying the findings in the order, Dentsply agreed to cease-and-desist from violations…and to pay a $1 million civil penalty.”

Beneath that timeline was an uglier story. Allegations surfaced that Dentsply Sirona had benefited for years from an illegal, anti-competitive agreement among its three main distributors—together accounting for as much as 90% of its U.S. sales—and that the company failed to disclose the arrangement to shareholders. The arrangement reportedly began at least a decade before the merger and only unraveled in 2017, when one distributor pulled out. Sales then dropped sharply.

This was the moment when old instincts collided with a new spotlight. The legacy Dentsply sales culture—comfortable with distributor relationships and aggressive approaches to revenue—ran headfirst into post-merger scrutiny and the heightened expectations of a newly combined public-market story. Practices that might have survived in calmer circumstances became explosive when investors were already watching for cracks.

In October 2017, those cracks turned into an earthquake. Dentsply Sirona announced the resignations of Bret Wise, the executive chairman; Jeffrey Slovin, the CEO and a director; and Christopher Clark, the president and COO. Mark Thierer stepped in as interim CEO, and Bob Size became interim president and COO.

The speed and scale of the purge was staggering. Barely 20 months after the merger closed, the top team that had sold the vision was gone. A later regulatory filing didn’t give reasons. But reporting cited an unnamed source saying the shakeup came as the company lagged expected earnings.

Investors responded instantly. After the announcement, the stock fell nearly 7% in a day, dropping from $59.81 to $55.65.

And now the deeper issues were out in the open. The legacy Dentsply business wasn’t a stable cash engine—it was weakening, with market share losses in consumables. Sirona’s innovation machine was no longer running like it had, as CEREC faced intensifying competition from 3Shape and others. Integration complexity had been wildly underestimated. And perhaps most damaging of all, the company no longer had a clean grip on the customer. Dentists saw confusion, not cohesion—and when your workflow and your reputation matter, confusion is a reason to switch.

The Wall Street Journal captured the mood with its blunt framing: “Behind unusual ouster of company's top three leaders: A troubled $14.5 billion merger.”

Activists noticed too. Third Point, led by Dan Loeb, took a stake and demanded change. The premium narrative evaporated as investors began to accept a harder possibility: the synergies weren’t simply late. They might never show up in any meaningful way.

For anyone watching, the lesson was painful and clear. Market leadership in two adjacent categories doesn’t automatically add up to value creation. Integration is a full-contact sport. Culture clashes don’t resolve themselves. And “merger of equals” often means something simpler in practice: no one is truly in charge.

VI. The Turnaround Attempt: New Leadership, New Strategy (2018–2020)

By early 2018, the board had seen enough. On January 17, Dentsply Sirona announced it had hired Donald M. Casey Jr. as CEO and added him to the board, effective February 12.

Casey was a signal that the company was trying to break the cycle. He wasn’t a dental lifer, and he wasn’t tied to either legacy camp. He was a medical-device operator: years at Johnson & Johnson, then a major leadership role at Cardinal Health. From 2012 through 2018, he ran Cardinal Health’s Medical Segment, a huge business built around manufacturing, distribution, and supply-chain execution. Before that, from 2010 to 2012, he led the Gary and Mary West Wireless Health Institute, a nonprofit focused on using technology to lower healthcare costs.

The board framed him as exactly what Dentsply Sirona needed: “After a comprehensive search and careful consideration, our Board unanimously concluded that Don has the right mix of skills, experience and talent to lead Dentsply Sirona to achieve its full potential. Don has deep experience in global manufacturing, product development and distribution of medical devices and technology.”

Casey didn’t arrive with a nuanced theory. He arrived with a blunt diagnosis: “We tried to be everything to everyone and became nothing to anyone.” In other words, the merged company had spent two years trying to keep every customer happy, keep every channel intact, and keep both legacy cultures untouched—and in the process, it had created an organization that couldn’t move fast, couldn’t prioritize, and couldn’t present a clear story to dentists.

So his plan was simplification—less sprawl, more focus. Dentsply Sirona would divest non-core assets and rally around what it called “Essential Dental Solutions.” It would try to rebuild trust with dental practices and, critically, with DSOs—the growing corporate chains like Heartland and Aspen that were starting to behave less like scattered customers and more like institutional buyers. And it would put more weight back behind R&D and digital innovation, because the “future” side of the merger had started to stall.

Execution followed the strategy. The orthodontic business was sold. Other assets were put on the market. The company reorganized to remove duplicate functions, and for the first time since the merger, it started doing the unglamorous work of actual integration instead of just talking about it. Casey also leaned into the DSO shift: these large groups wanted volume pricing, integrated solutions, and data connectivity—needs that, in theory, a scaled player like Dentsply Sirona should have been uniquely positioned to meet.

Then the world changed.

In early 2020, COVID-19 slammed the brakes on dentistry. Practices shut down globally as elective procedures stopped. Dentsply Sirona moved into crisis mode: emergency cost cuts, liquidity preservation, and operational steps to help customers reopen safely.

The pandemic also acted like an accelerant. Digital workflows became more attractive as practices looked for faster, more streamlined, and more contact-conscious ways to operate. Consolidation pressure intensified too, as independent practices struggled and larger DSOs gained leverage.

Casey got the company through the shock without it falling apart. Costs came down. The balance sheet was protected. And when dentistry started to reopen, there was cautious optimism that maybe—finally—the turnaround had a chance.

That optimism wouldn’t last.

VII. The Digital Dentistry Revolution & Competitive Threats

While Dentsply Sirona was still trying to make the merger function, the ground under the industry was moving. The digital wave Sirona helped create didn’t slow down—it sped up. And the more dentistry went digital, the more the company’s most valuable asset, the CEREC ecosystem, started to look less like a moat and more like a walled garden dentists wanted to climb out of.

One of the clearest signals came from an unlikely place: a partnership with a rival.

Dentsply Sirona announced a partnership with 3Shape, the Danish company behind TRIOS intraoral scanners and a fast-growing digital workflow platform. Historically, these two were direct enemies in the scanning and CAD/CAM world. So if they were now willing to work together, something bigger was happening.

Part of that “something” was Align Technology. Invisalign had become the gravitational center of clear aligners, and Align was tightening control over the digital front door: scanning. By closing Invisalign workflows to new scanners on the market—except its own iTero, including excluding CEREC Primescan and 3Shape’s TRIOS4—Align was effectively telling the rest of the industry: if you want the biggest aligner brand, you play by our rules.

Suddenly, old rivals had a shared incentive to create alternatives.

3Shape leaned hard into the message dentists increasingly wanted to hear: openness. As 3Shape CEO Jakob Just-Bomholt put it, “3Shape's goals and solutions are based on an open ecosystem philosophy and on working together with other companies to provide better and more cost-effective solutions that will benefit clinicians and their patients.”

That philosophy was the strategic threat. CEREC’s original magic was that it worked end-to-end—scan, design, mill—inside one tightly controlled system. For years, that lock-in was a feature. But as digital dentistry matured, many clinicians wanted the opposite: the freedom to mix the best scanner with the best design software with the best manufacturing option. In that world, closed systems stop feeling premium and start feeling restrictive.

By 2023, Dentsply Sirona and 3Shape were deepening workflow integrations, aiming to make it easier for practices to connect DS Core, Primemill, and Primeprint with TRIOS scanning through 3Shape Unite. The takeaway wasn’t just that integration was improving. It was that the market was forcing Dentsply Sirona to adapt to an ecosystem where interoperability was becoming table stakes.

At the same time, the company faced another battleground: clear aligners.

Align Technology’s Invisalign had already disrupted traditional orthodontics, and the category was growing fast. Dentsply Sirona’s answer was SureSmile—its own clear aligner platform—and the company looked for a way to accelerate.

In January 2021, Dentsply Sirona announced it had acquired direct-to-consumer aligner company Byte in an all-cash deal worth $1.04 billion. The logic was straightforward: Byte would provide a direct-to-consumer channel and a stronger position in the fast-growing at-home aligner segment. Byte framed its mission as expanding access and affordability through a nationwide network of licensed dentists and orthodontists.

Then there was the buyer itself—because the buyer was changing.

DSOs weren’t just growing; they were rewiring purchasing power. The American Dental Association reported that the share of dentists affiliated with a DSO rose from 8.8% in 2017 to 10.4% in 2019, and to 13% in 2023. Depending on the metric—dentists versus offices—and the source, estimates for DSO penetration in the U.S. ran higher, with forecasts pointing to a materially more consolidated market in the years ahead.

The directional shift mattered more than any one percentage point: dentistry was moving from thousands of independent, relationship-driven purchases toward fewer, larger, procurement-driven decisions.

That change cut both ways for Dentsply Sirona. Large DSOs wanted volume pricing, integrated solutions, and data connectivity. They were sophisticated buyers with leverage, and they would switch vendors for better economics or better workflows. The dealer model that had powered Dentsply’s consumables dominance for decades looked less inevitable in a world where big accounts wanted direct relationships and standardized systems. The company found itself straddling two eras: legacy dealer commitments on one side, and DSO demands on the other.

And just as the market consolidated at the top, it was commoditizing at the bottom.

Chinese manufacturers were gaining share, especially in developing markets, and improving quickly. The pitch was brutally effective: “good enough” products for a fraction of the price. As quality climbed and these players moved upmarket, Dentsply Sirona faced the question that haunts every premium incumbent: when the gap narrows, what exactly are customers still paying for?

The company wasn’t just fighting integration problems anymore. It was fighting a market that was becoming more open, more consolidated, and more price-competitive—all at the same time.

VIII. Recent Inflection Points & Current State (2020–2025)

The post-COVID stretch delivered a short-lived bounce—then more chaos. As practices reopened, pent-up demand pulled forward big equipment purchases in 2021 and 2022. But the “everyday” side of the business didn’t snap back as cleanly. Consumables lagged as patient visits stayed uneven, and the global supply chain did what it did to everyone: chips became scarce, imaging production got squeezed, and inflation pushed manufacturing costs up just as customers were getting more price-sensitive.

And then, in April 2022, the board cut ties with Don Casey—effective immediately—before it even had a permanent replacement lined up. Casey had been brought in as the steady, outside operator to finally make the merger work. Four years later, he was out.

Not long after, an even more damaging thread surfaced: Dentsply Sirona was under investigation for alleged securities fraud. The company said its audit committee found no evidence of intentional wrongdoing or fraud by Casey or former CFO Jorge Gomez. But it also said both men violated the company’s code of ethics and business conduct. The company had already told the SEC it was investigating the use of incentives to sell products to distributors in the third and fourth quarters of 2021.

The internal review also turned up accounting problems tied to China. According to the investigation, employees there processed returns and/or exchanges in ways that didn’t match what distributor agreements and sales contracts allowed. The company said it planned to restate its third-quarter 2021 report and its 2021 annual report.

Then came the kind of accounting line item that tells you how far expectations have fallen. Dentsply Sirona announced it expected to record a $1–1.3 billion goodwill impairment charge for the first nine months of 2022, pointing to macro forces like a higher cost of capital, cost inflation, unfavorable currency impacts, and increased supply chain costs.

By late summer, the company had a new leader. On August 28, 2022, Dentsply Sirona named Simon D. Campion—formerly an Executive Vice President and the President of BD’s Interventional segment—as CEO and a board member.

Board chairman Eric K. Brandt introduced him as “a high-integrity, transformational leader” with deep operational experience and a record of driving growth. Campion’s resume fit the moment: when BD acquired C. R. Bard in 2017, he helped lead integration work, and later ran BD’s Interventional segment—about $4.2 billion in 2021—through a broader integration.

Campion came in as an outsider and said as much. He told interviewers he saw “several opportunities” at Dentsply Sirona, and believed his background in enterprise transformation, customer-centricity, and innovation could help the company become “more efficient and more competitive” while sharpening its innovation agenda.

He also promised urgency. “The actions we are planning follow our comprehensive review of the business and will enable Dentsply Sirona to improve its execution, build a winning portfolio, return to growth, and generate consistent returns,” he said, describing a new operating model meant to drive “overdue organizational integration” and stronger accountability. The company said the plan was expected to deliver at least $200 million in annual cost savings over the next 18 months.

One symbol of what “overdue integration” actually meant: the company had been running 14 different ERP systems. Campion made collapsing that mess into one—via a global implementation of SAP S/4HANA—a centerpiece of its enterprise digitalization. “We want to make it easier for customers to do business with us,” he said, while emphasizing that pushing digital dentistry forward would remain a constant focus.

But the numbers showed how hard it was to stabilize the business in reality. In 2023, net sales were $3,965 million, up 1.1% from 2022, while the company posted a net loss of $132 million. In 2024, net sales fell to $3,793 million, down 4.3% from 2023, and the net loss widened to $910 million. A huge driver was non-cash impairment charges: $870 million net of tax in 2024 tied to goodwill and other intangible assets.

Meanwhile, that $1 billion Byte purchase—the big swing at direct-to-consumer aligners—was being substantially written down and reworked. Dentsply Sirona said it would refocus Byte around treatments with expanded in-person dentist oversight. It would not reinstate the at-home Byte Aligner Systems and Impression Kits, though it would continue supporting non-contraindicated Byte Aligner patients already in treatment.

And then, in July 2025, another reset. Dentsply Sirona announced that Simon Campion would leave on July 31, 2025. Daniel Scavilla—most recently President and CEO of Globus Medical—would take over as CEO effective August 1.

Another CEO transition. The fifth CEO in nine years since the merger.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive & What Makes Dental Different

If you want to understand why Dentsply Sirona has struggled to turn size into momentum, you have to understand the market it sells into. Dentistry looks like healthcare from far away, but up close it behaves like its own ecosystem—with its own rules, relationships, and friction.

Dentsply Sirona develops, manufactures, and markets dental equipment, cloud-enabled solutions, dental products, and other healthcare consumables. It runs through four segments: Connected Technology Solutions, Essential Dental Solutions, Orthodontic and Implant Solutions, and Wellspect Healthcare.

Here’s the first defining feature of the industry: it’s wildly fragmented. In the U.S. alone, there are more than 200,000 dentists, and most work in small, independent practices. These are highly trained professionals who tend to build brand preferences early—often in dental school—and then stick with what they trust. They rely heavily on reps and peers, and they’re skeptical of changes that might disrupt their clinical workflow.

That fragmentation creates an unusually “high-trust, high-touch” selling environment. Relationships matter. Familiarity matters. And once a dentist has a product they like—especially for things that are tactile and technique-driven—it can be very hard to dislodge.

Now layer in the purchase cycles. Most dental equipment is a long-term commitment. Chairs, imaging systems, CAD/CAM units—these can last a decade or more. Switching isn’t just writing a check. It means staff retraining, new service relationships, new software, and real workflow disruption. For decades, that’s made the dealer network the kingmaker, with reps playing an outsized role in what practices buy and what brands they stay loyal to.

Against that backdrop, Dentsply Sirona’s portfolio is broad:

The Connected Technology Solutions segment offers imaging equipment, motorized dental handpieces, treatment centers, and other instruments; and intraoral scanners, 3D printers, and mills, as well as CEREC, a full-chairside economical restoration of esthetic ceramic dentistry offering.

The Essential Dental Solutions segment provides motorized endodontic handpieces, files, sealers, irrigation needles, and other tools for root canal procedures; restorative products; curing light and dental diagnostic systems; ultrasonic scalers and polishers; and dental anesthetics.

The Orthodontic and Implant Solutions segment offers SureSmile, a clear aligner solution that includes whitening kits and retainers; VPro, a high frequency vibration technology device; dental implant products; digital dentures; crown and bridge porcelain products; bone regenerative and restorative solutions.

The Wellspect Healthcare segment offers intermittent urinary catheters under the LoFric brand and irrigation systems under the Navina brand.

This is where the merger’s original promise comes back into focus. The integration dream was to sell a complete digital workflow—CEREC systems, mills, and the materials that run through them—like one seamless package. In theory, that’s how you get “ecosystem” lock-in.

In reality, dentistry doesn’t like being told there’s only one right way to work. Dentists want choice. They want to mix-and-match components, pick the scanner they love, the lab they trust, the materials they prefer. Bundling can quickly feel less like convenience and more like coercion—anti-competitive, restrictive, and designed for the vendor’s margins, not the clinician’s outcomes. And even when the company tried to unify workflows, data integration often lagged. Systems still didn’t talk to each other smoothly, and the friction showed up where it hurt most: in the day-to-day experience of the practice.

The financial profile reflects that tension. Gross margins have generally sat in the mid-to-high 50s, with equipment typically higher than consumables. But operating margins have compressed into the low-to-mid teens—well below the 20%+ profile Sirona delivered pre-merger. R&D has hovered around 5% of revenue, a level that invites an uncomfortable question for any company selling itself as a technology leader: are you investing like one? And returns on capital have been dragged down not just by integration costs, but by the very visible evidence of value destruction—massive goodwill impairments that effectively admitted the merger was worth far less than the price paid.

X. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

In most corners of dentistry, the walls are still high. You need regulatory clearances (FDA in the U.S., CE Mark in Europe). You need manufacturing know-how that’s hard to fake. And you need distribution and service relationships that usually take years to earn.

But in the fastest-moving parts of the market—software, scanning, and parts of digital workflow—those walls are getting shorter. 3D printing is lowering the capital required to get into production for certain applications, and software can scale without building factories. And as DSOs grow, they create a very different kind of “front door” into the industry: win one corporate buyer, and you can roll out across hundreds of offices without ever playing the traditional dealer-and-rep game.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Supplier power is generally limited. Dentsply Sirona is vertically integrated in many areas, and most consumables rely on inputs that are relatively commoditized. There are pockets where concentration matters—specialty materials like zirconia, for example—but overall, suppliers aren’t the ones setting the terms.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH (INCREASING)

This is the force that’s changed the most, and it’s still moving.

For decades, dentistry’s customer base was thousands of independent practices. That fragmentation kept buyer power low; one dentist couldn’t demand much from a global manufacturer. But DSOs are steadily turning scattered demand into centralized purchasing. These are professional procurement organizations, built to negotiate price, standardize supplies, and swap vendors if they don’t like what they’re getting.

As ADA chief economist Marko Vujicic put it, “Our updated data show higher rates of dentist affiliation with DSOs as well as less dentists in solo practice and more in groups.”

Add in government payers in parts of Europe pushing down reimbursement, plus online price transparency making it easier to shop around, and the direction is clear: the leverage is shifting toward the buyer.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Substitution in dental isn’t usually “a different brand.” It’s a different way of doing the work.

Clear aligners have taken meaningful share from traditional orthodontics. 3D printing threatens to replace milling in certain lab and in-office applications over time. AI-driven diagnostics could reduce demand for some imaging workflows, or at least compress differentiation. And on the edge of the market, “do-it-yourself” dentistry solutions are popping up—clinically controversial, but competitively real.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Competition is brutal, and it’s everywhere:

- Equipment: Planmeca, KaVo Kerr (Envista), A-dec, Carestream

- Consumables: Ivoclar Vivadent, 3M, GC Corporation, Kulzer

- CAD/CAM: 3Shape, Align Technology, Straumann

Dentsply Sirona has long benefited from being early in CAD/CAM and digital dentistry. But the economics attracted a crowd. Cosmetic procedures grew. Digital workflows expanded. And over the last decade, more capable competitors piled in—some competing on innovation, some on openness, and plenty on price.

The end result is predictable: price pressure rises, differentiation erodes, and even the category leader finds itself playing defense.

Overall Assessment: The industry is getting less attractive. Buyer power is climbing, rivalry is intense, and the premium parts of the market are no longer protected by “first mover” advantage. Scale still matters—but it isn’t automatically turning into profitability.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE (WEAKENING)

In consumables, scale still helps. Big factories and big purchasing volumes should mean lower unit costs. But it hasn’t been enough to stop margin pressure as competition tightens and pricing gets more transparent. And on the equipment side, the advantage isn’t really “scale” at all—it’s precision manufacturing and service, which don’t get dramatically cheaper just because you’re bigger. Even R&D, where scale should compound, hasn’t translated into a clear innovation lead.

Network Effects: WEAK

Dentistry isn’t social-media-like. Most dentists operate independently, and the industry historically hasn’t had true network effects. Digital dentistry could change that—shared data, workflow standards, software ecosystems, communities that learn from each other. But Dentsply Sirona hasn’t captured that flywheel in a meaningful way, while competitors like 3Shape have been building more connective tissue through open workflows and platform-style thinking.

Counter-Positioning: NONE (VICTIM OF)

This is where the company gets boxed in. Dentsply Sirona is the incumbent everyone else positions against: 3Shape with openness versus CEREC’s historically closed ecosystem; Chinese manufacturers pitching “good enough” at roughly half the price; clear aligner players sidestepping traditional lab workflows entirely. The company doesn’t have a business model advantage here that competitors can’t mimic—it’s mostly defending legacy positioning while others redefine the game.

Switching Costs: MODERATE (DECLINING)

Switching costs still exist, especially in equipment. Buying a new system means capital outlay, training, and workflow disruption, and that friction is real. Consumables loyalty can be even more habit-driven—dentists stick with what feels right in their hands. But the direction is negative: younger dentists are more willing to switch, expect interoperability, and don’t have decades of muscle memory tied to one brand. DSOs accelerate that trend by standardizing across networks—and they’ll swap vendors if the economics or the workflow is better.

Branding: MODERATE

The brand is still known. In many product categories, “Dentsply” has the kind of recognition that comes from decades in dental schools and operatories. But the premium promise has been weakened by post-merger execution problems—especially service and integration issues that customers actually feel. And Sirona, once a clean premium technology brand, has been blurred by the combination.

Cornered Resource: WEAK

There’s no single patent fortress here that locks competitors out. Dealer relationships matter, but they’re not exclusive. The engineering culture that once made Sirona distinctive has been disrupted, and that’s not something you can easily reconstitute with org charts. The closest thing to a cornered resource is the CEREC installed base—but its power fades as workflows become more open and switching becomes less intimidating.

Process Power: MODERATE (DECLINING)

There is real manufacturing excellence in parts of the portfolio. But at the company level, integration has hurt process efficiency—systems, teams, and decision-making haven’t consistently operated like one machine. Innovation processes haven’t looked best-in-class, and quality and service issues after the merger have chipped away at reputation.

Overall Power Position: What’s left looks like a company running on advantages that used to be stronger—scale in consumables and switching costs in equipment—while failing to build new, durable power. Dentsply Sirona is still the market leader, but too often it feels like leadership by inertia, not leadership by momentum. And that makes it vulnerable from multiple directions at once.

XII. The Bear Case vs. Bull Case

Bear Case: "Value Destruction Continues"

The dark view starts with a simple claim: the merger didn’t just fail to create value—it damaged both franchises. A decade of messy integration, revolving-door leadership, and stop-start strategy has chipped away at competitive position, morale inside the building, and trust with customers. In that world, market share doesn’t come back easily. The reputation hit becomes self-reinforcing.

Then there’s digital. If you believe the platform battle has already been decided, Dentsply Sirona is on the wrong side of it. 3Shape’s pitch—an open ecosystem that plays nicely with everyone—fits what many modern practices want. Align Technology, meanwhile, sits at the center of clear aligners, with iTero shaping the scanning workflow. Dentsply Sirona ends up fighting on multiple fronts at once, mostly in reaction mode.

Buyer power is also moving the wrong direction. As DSOs grow, purchasing shifts from relationships to procurement. Large groups can demand price concessions, standardize products across hundreds of offices, and switch vendors if the deal isn’t compelling. That same shift undermines the traditional dealer model that helped build Dentsply’s consumables dominance, as more volume moves toward direct, enterprise-style negotiations.

At the low end, the pressure keeps rising. Chinese manufacturers have followed a familiar playbook: start in developing markets, improve quality fast, then move upmarket until “good enough” becomes a real option everywhere. If that continues, premium positioning gets harder to defend—and price becomes the battlefield.

And some of the company’s biggest bets haven’t helped. Byte, the roughly $1 billion swing at direct-to-consumer aligners, has already been substantially written down and repositioned. Add it all up and the bear case is brutal: management has had nearly a decade since the merger and still hasn’t produced a durable turnaround.

Finally, the constraints. Debt limits flexibility. Multiple CEO changes signal a board still searching for the right path. And the stock sitting at multi-year lows isn’t just bad luck—it’s the market saying it doesn’t believe the fix is close.

Bull Case: "Turnaround Underway, Undervalued"

The optimistic view starts with what hasn’t changed: Dentsply Sirona is still the only scaled player that spans consumables, equipment, and digital technology. If dentistry keeps consolidating, that breadth could matter more, not less. DSOs, especially, may prefer fewer vendor relationships, cleaner standardization, and a partner big enough to support them across geographies and categories. Dentsply Sirona can at least make that “one-stop shop” pitch credibly.

The bull case also argues the company is finally doing the unglamorous work it avoided for years. Campion’s push to unify systems—like the move toward a single SAP implementation—and restructure the organization is painful, but necessary if the company wants to execute consistently. As Campion put it: “Our ability to innovate is critically important to us. I also believe the fact that we can provide a dental practice of any shape, size or affiliation with a single source for the vast majority of their dental products is a competitive advantage.”

There are also tangible customer relationships that support the “scaled partner” thesis. One example is PDS Health, whose network includes over 1,600 dentists across more than 580 dental practices in the United States, aligned around access to Dentsply Sirona innovations.

Financially, the bulls point to the ballast: consumables. Even if growth is muted, the consumables business can generate steadier cash flow than big-ticket equipment, and that can underpin valuation. On the equipment side, the installed base is aging, and replacement cycles eventually arrive.

And on digital, the story is that the company is adapting. DS Core is positioned as a cloud-based workflow platform, and CEREC on DS Core brings CEREC design into the browser, reducing reliance on local CAD software. It’s built on the established CEREC system, which produces more than 8 million crowns annually. Just as importantly, interoperability has expanded: 3Shape TRIOS scans can flow into the DS Core/CEREC workflow via 3Shape Unite.

If you believe those operational fixes and product shifts are real—and that the market is over-penalizing the company for its past—then today’s stock price could represent a deep discount to historical multiples and a sum-of-parts view. In that framing, activist involvement or strategic interest could provide a floor. And the underlying demand picture for dentistry still isn’t broken: aging populations need care, and emerging markets continue to grow.

The Realistic Case:

The middle view is less dramatic and, for most investors, more useful: this is a slow-growth, lower-margin dental equipment and consumables business with a challenged competitive position. The valuation reflects that. Whatever the marketing says, this isn’t a high-multiple tech company.

A turnaround is possible, but it requires unusually clean execution in an environment that isn’t getting easier. The best plausible outcome is stabilization: hold share, grow roughly with the market, and expand margins modestly—on the order of a few hundred basis points—over several years.

That probably won’t make it an exceptional investment. But at the right price, with the right expectations, it could be a workable one for patient, value-oriented investors.

XIII. Lessons & Playbook

1. "Merger of Equals" Almost Never Works

The compromise leadership structure—Dentsply’s CEO as Chairman, Sirona’s CEO as CEO—set the tone for everything that followed. Power was split, accountability got fuzzy, and every hard integration decision turned into a negotiation between camps. Successful mergers need one clear leader with the authority to make unpopular calls and actually combine the businesses. “Equals” may protect egos in the moment, but it often destroys value over time.

2. Distribution Channel Conflicts Are Real

You can’t just stack two go-to-market machines on top of each other and hope they harmonize. Dentsply was built on dealers. Sirona sold high-end equipment through a direct model. After the merger, the company never fully answered the uncomfortable question: who owns the customer? Dealer vs. direct. Volume vs. margin. You can try to straddle both, but eventually the channel conflict shows up in missed targets, confused reps, and resentful partners.

3. Market Leadership Doesn't Guarantee Returns

Being number one in share doesn’t protect you if your competitive position is quietly slipping. Dentsply Sirona had scale, but scale isn’t the same thing as Helmer-style Power. Without durable advantages, you don’t have a moat—you have a bigger target. And scale without power can turn into something worse than weakness: you become the largest company losing share.

4. Integration Takes 2-3x Longer Than Expected

Especially when you’re integrating across countries, cultures, and business models—and selling through a complex B2B commercial engine. Systems don’t match. Processes don’t line up. Incentives collide. People resist. The spreadsheet makes synergies look inevitable; reality makes them optional, delayed, and sometimes unattainable.

5. Technology Transitions Are Existential

Dentistry’s shift from analog to digital has been playing out for more than two decades, and transitions like that are rarely gentle on incumbents. Legacy profit pools make it hard to cannibalize yourself, even when you know you should. And platform battles—open versus closed ecosystems—don’t just shape product features. They decide who gets to be the default workflow for years. Sirona built a closed system; the market increasingly rewarded openness.

6. Watch for These Warning Signals:

- When management changes 3x in 5 years, the problem is structural, not personal

- When “synergies” start showing up as “restructuring charges,” the integration story is breaking

- When market share declines despite leadership position, competitive power is eroding

- When activist investors keep coming back, value destruction isn’t a one-off—it’s a pattern

7. Industry Evolution Lessons:

As DSOs consolidate the buyer base, negotiating power shifts dramatically toward customers. Younger practitioners behave differently: they’re less loyal to legacy brands, expect interoperability, and resist lock-in. Meanwhile, global competition keeps rising as quality gaps close. And in markets like this, “good enough” at half the price wins more often than premium incumbents want to believe.

XIV. Epilogue: What Does the Future Hold?

Near-term (2025-2026):

In the near term, the backdrop is still tough. Equipment demand stays soft as higher interest rates and broader macro uncertainty make big capital purchases easier to delay. So management’s agenda is likely to look familiar: margin improvement, operational execution, and the slow, grinding work of running the company tighter than it has in years.

At the same time, the real strategic question doesn’t go away. The digital platform buildout continues, and the company has to prove that DS Core is more than a product launch—that it can become a sticky workflow hub that dentists and DSOs actually want to live inside, and that third parties want to build on. If there’s room to buy missing pieces in software or AI, small M&A to fill portfolio gaps is the obvious move.

And, of course, there’s leadership. Daniel Scavilla takes over in August 2025, coming from Globus Medical with a reputation for operational transformation in orthopedic devices. The question is as stark as it is unfair: will the sixth CEO since the merger finally deliver sustainable improvement?

Medium-term (2027-2030):

If the consolidation wave continues, DSO penetration likely climbs toward 30-40% of the U.S. market. That could be a tailwind—large organizations might prefer fewer vendors and value integrated solutions. Or it could be a headwind, with procurement teams using scale to demand concessions and squeeze margins.

Meanwhile, the platform war gets sharper. Open ecosystems keep gaining ground, and closed workflows get harder to defend. On the cost side of the market, Chinese manufacturers push more aggressively into developed countries, bringing price pressure with them.

That combination keeps “strategic alternatives” on the table: a break-up into separate equipment and consumables businesses, a sale to private equity, or some form of partnership with a technology player looking for a path into healthcare.

Long-term Questions:

In 20 years, does “dental equipment company” still mean what it means today—or does it blur into something closer to a healthcare IT company with hardware attached? Does AI meaningfully reduce the need for human dentists in certain workflows, or just change how they work? Can Dentsply Sirona reinvent itself into a modern platform business, or is it destined to trade as a permanent value trap? And if reinvention is possible, what would it actually take to restart growth and restore real innovation momentum?

The Biggest Surprises:

The surprises are, in hindsight, the most unsettling parts of the story: how quickly market leadership eroded after the merger; how badly integration went, and how long it stayed broken; how an industry that looked stable from the outside turned out to be in the middle of a real technology shift. And maybe most of all: that neither activist pressure nor five management changes managed to fix the core issues.

For Founders:

Cultural integration is the hardest part of M&A, and it’s the part the spreadsheet can’t model—ignore it and the deal will collect interest in the form of years of distraction. Market leadership is fragile, not permanent, and it has to be defended with constant reinvestment. And sometimes 1+1 really does equal less than 2.

For Investors:

Multiples compress for reasons. “Mean reversion” is not a strategy. Turnarounds usually take longer and deliver less than the pitch suggests. Industry structure analysis—like Five Forces—often matters more than any single management team’s optimism. And when you keep hearing “this time is different,” it usually isn’t.

XV. Key Metrics to Track

If you’re tracking Dentsply Sirona as an investor, there are countless line items you can get lost in. But two tell you, quickly, whether the company is actually getting healthier—or just rearranging the deck chairs.

1. Organic Revenue Growth (excluding FX and M&A)

This is the cleanest read on whether dentists and DSOs are choosing Dentsply Sirona because they want to, not because currency moved in their favor or a deal temporarily inflated results. When organic growth is consistently positive, it suggests the franchise is stabilizing. When it’s negative, it’s a warning that competition and customer churn are still winning. In 2024, organic sales fell 3.5%. That’s not noise. That’s the core business shrinking, and it’s a trend that has to reverse.

2. Adjusted Operating Margin Trajectory

Margins are where the merger either finally pays off—or where you get confirmation that it never will. Today’s operating margin range, roughly 10–15%, sits far below the 20%+ Sirona delivered before the merger. That gap is the “integration opportunity” everyone talked about in 2016, still sitting on the table. If margins expand, it’s evidence that the unglamorous work—systems consolidation, operational discipline, a coherent go-to-market—is starting to stick. If they don’t, it usually means the competitive environment is too intense, the organization is still too messy, or both.

Top Resources for Further Learning:

- Dentsply Sirona investor presentations (2016-2024)—watch how the language and promises evolve

- SEC filings and restatement documents (2017-2018, 2022)—understand the accounting issues

- 3Shape company strategy materials—study the disruptor playbook

- "The Innovator's Dilemma" by Clayton Christensen—the concepts apply perfectly to CEREC's platform challenges

- Industry consolidation reports from the ADA and dental trade publications—understand the DSO transformation

The Dentsply Sirona story still isn’t finished. Nearly a decade after the merger that was supposed to build a dental technology powerhouse, the company has kept searching for steady leadership and a strategy that holds up in the real world.

The lesson isn’t that mergers are bad, or that dentistry is uniquely hard. It’s that size doesn’t solve execution. “Merger of equals” doesn’t create clarity. And scale without real competitive power can quietly turn a market leader into a company playing defense.

Whether Dentsply Sirona ultimately finds its footing or continues to drift, the journey is already a case study in what happens when integration authority is unclear, culture clashes are left to fester, and moats erode faster than management admits. For business builders and investors alike, it’s a story worth watching.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music