Xperi Inc.: The Invisible Tech Giant Powering Your Digital Life

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

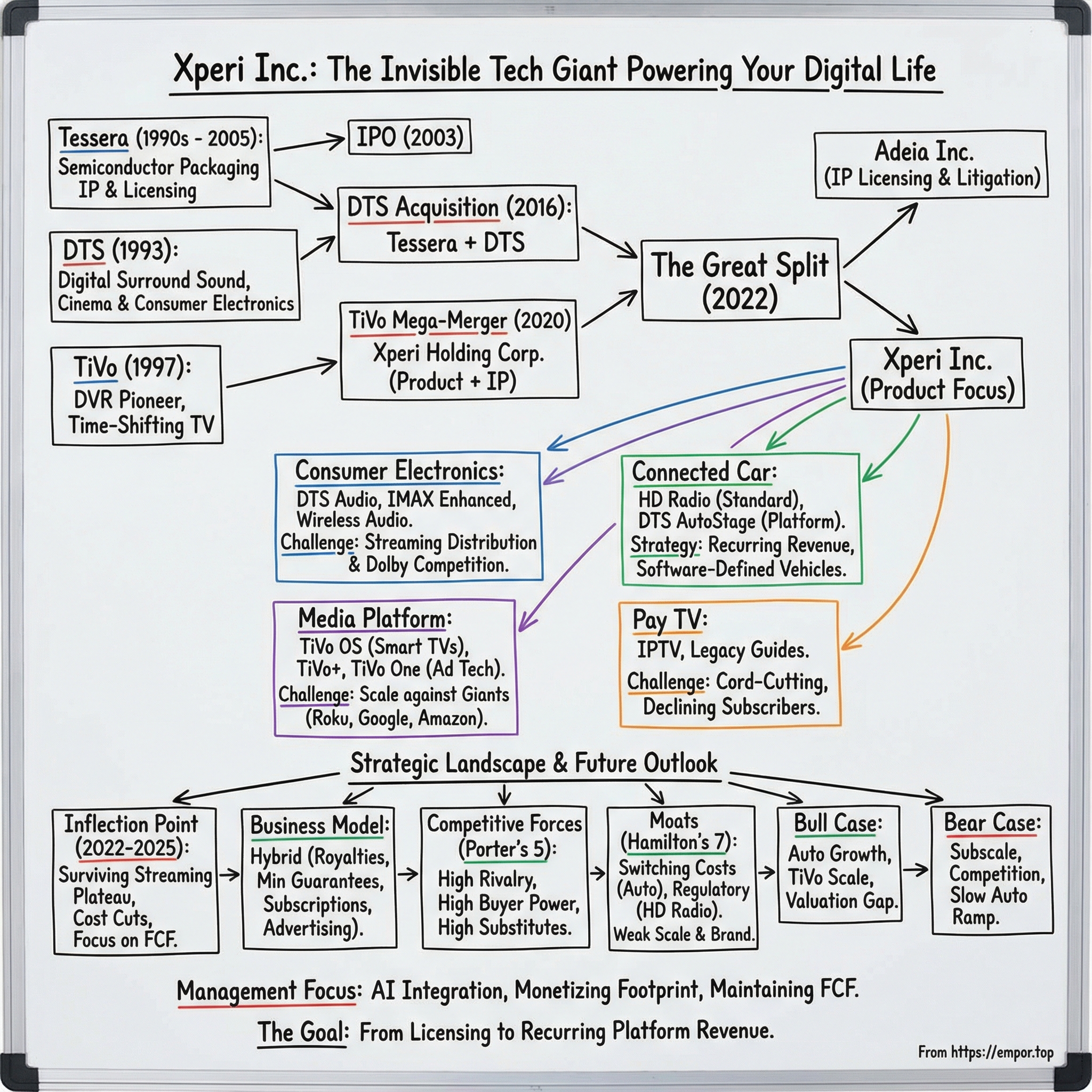

Somewhere in the last hour, you probably bumped into Xperi—without ever seeing the name.

Maybe it was HD Radio turning a fuzzy FM station into crisp digital audio. Maybe it was a movie or game kicking into DTS surround sound. Maybe your smart TV’s “you might like this” recommendations were quietly powered by TiVo’s metadata and discovery engine. Maybe you spotted IMAX Enhanced on a TV box at Best Buy, or your car’s in-dash entertainment loaded content through DTS AutoStage.

That’s the trick with Xperi: it’s everywhere, and almost invisible.

Xperi Inc. is an American multinational technology company headquartered in San Jose, California. It builds the software and platforms that sit inside consumer electronics and connected cars, and it provides media platform technology for delivering video over broadband. The company is organized into four business units—Pay TV, Consumer Electronics, Connected Car, and Media Platform—and its best-known brands are DTS, HD Radio, and TiVo.

Here’s the core paradox: Xperi’s technology shows up in billions of devices worldwide, yet the company trades at a market capitalization under $400 million. How did a business that started as a patent-licensing machine evolve into a behind-the-scenes infrastructure provider for automotive entertainment, streaming, and connected devices—and why does the market value it like it’s running out of road?

Because this isn’t a simple growth story. It’s a survival story—and a transition story. Over three decades, the company has lived through multiple near-death experiences while trying to pull off one of the hardest moves in tech: going from monetizing intellectual property to building and running real products. Along the way, it picked up some of the most iconic names in consumer electronics: Tessera’s semiconductor patents, DTS’s theater-grade sound, and TiVo’s legendary DVR.

Today, Xperi is still in motion. It’s guiding toward 2025 GAAP revenue of $440 million to $460 million, and it’s trying to tilt the business toward recurring platform revenue—especially through TiVo OS, which has reached 4.8 million monthly active users.

Over this episode, we’ll keep coming back to four questions: Why do licensing businesses struggle to become product companies? When do standards turn into moats—and when do they become traps? What do you do when your best-known innovations are behind you, but your technology still matters? And, ultimately, is Xperi deep value… or a value trap?

II. The Deep History: From Xerox PARC to Tessera (1990s–2005)

In the early 1990s, the semiconductor industry ran into an uncomfortable truth: Moore’s Law wasn’t just about shrinking transistors. You also had to get signals and power in and out of the chip—reliably, cheaply, and at massive scale. And the unglamorous part of the stack, packaging, was becoming the bottleneck. Traditional wire bonding was starting to look like yesterday’s solution in a world sprinting toward smaller, faster, denser electronics.

That’s the opening Tessera stepped into.

Tessera, Inc. was established in 1990 to focus on semiconductor packaging and interconnect technologies. Its big push was wafer-level packaging—approaches that brought packaging closer to the wafer process itself, helping devices get smaller and perform better.

In the early 1990s, Di Stefano invented what became core chip-scale packaging (CSP) technology. The concept was deceptively simple and incredibly powerful: make the package nearly the size of the silicon die. In practice, it was the kind of step-change that turned “maybe someday” miniaturization into something manufacturers could actually ship at volume—technology that ended up widely used in mobile wireless and memory devices.

But the most important thing about Tessera wasn’t just what it invented. It was how it chose to make money.

Instead of building factories or selling equipment, Tessera built a patent portfolio and licensed its proprietary technology. As miniaturization became the defining trend in electronics, that licensing model turned into a printing press. Tessera wasn’t trying to out-manufacture the semiconductor giants; it was positioning itself so those giants—Intel, Samsung, and many of the major chipmakers—would pay royalties to use the techniques Tessera had locked up.

And Tessera enforced those rights. This was the company’s original operating system: invent, patent, license—and when necessary, litigate.

Xperi Holding Corporation ultimately traces its roots back to Tessera, Inc., founded in 1990 and renamed Tessera Technologies, Inc. ahead of its initial public offering in 2003. That IPO marked the moment the model went from a clever strategy to a full-fledged public-company business.

For a long time, it worked. The industry needed advanced packaging, Tessera held key patents, and royalties flowed.

But the long arc of this story matters: by the mid-2010s, the foundations began to weaken. Patents expired. Competitors found ways around them. And as smartphones consolidated into fewer, more powerful players, the balance of leverage shifted. Tessera needed a new act.

Still, the DNA was set. Tessera had mastered extracting value from intellectual property. The problem was that the next chapters of Xperi’s life would demand something else entirely: building enduring product businesses, not just winning the right to collect tolls.

III. The DTS Audio Acquisition: Entering Consumer Tech (2016)

By 2016, Tessera’s original engine—semiconductor patent licensing—was running out of gas. Revenue had flattened, the most valuable patents were getting long in the tooth, and the path forward was clear in the harshest way possible: either diversify, or slowly fade.

The lifeline came from a company whose origin story includes Hollywood, a secret test run, and a T-Rex.

DTS began in 1990, when entrepreneur and inventor Terry Beard founded Digital Theater Systems Corporation in California to develop digital sound for movies. Beard had previously run Nuoptix, a maker of optical sound recording equipment. And in the mid-1980s, he and Jim Ketcham of Lorimar Pictures started working on digital multi-channel sound that theaters could actually deploy. By 1990, they had a working system—and a set of patent applications to match.

The turning point was as cinematic as the industry itself. In 1991, the team demonstrated the system to Steven Spielberg. He liked what he heard. Universal Studios then let DTS quietly test the technology on release prints of a low-budget horror movie called Dr. Giggles. Only after that trial did the studio sign off on DTS for Spielberg’s upcoming dinosaur blockbuster, Jurassic Park.

In 1993, from its base in Calabasas, California, DTS officially arrived as a challenger to Dolby, launching in theaters with Jurassic Park. When the T-Rex roared in DTS Digital Surround, it wasn’t just louder—it was immersive. DTS quickly became the “other” surround-sound standard: never dethroning Dolby’s dominance, but building real credibility, especially among enthusiasts who argued DTS’s higher bitrates sounded better.

Crucially, DTS wasn’t just about movie theaters anymore. It had expanded into consumer electronics—phones, home theater, and cars—and it had already made a deal that would matter enormously for Tessera’s future. In 2015, DTS acquired iBiquity Digital Corporation, the developer of HD Radio, the North American digital audio broadcast standard. Tessera had also been making its own moves beyond semiconductors, including acquiring FotoNation in 2008 for image enhancement and analysis. But DTS was the big swing.

In September 2016, Tessera Technologies and DTS announced a definitive agreement: Tessera would buy DTS for $42.50 per share, a 28% premium to DTS’s 30-day volume weighted average price as of September 19, 2016. The deal was all-cash, valued at roughly $850 million.

On paper, the story sold itself. Tessera would combine its licensing muscle with DTS’s product licensing and deep customer relationships across mobile, home, and automotive. Management pitched an “expanded, integrated platform” to push “smart sight and sound,” and forecast pro forma 2016 revenue of around $450 million—nearly half coming from product licensing. That was the point: move away from a shrinking semiconductor IP business toward something with more durable, repeatable demand.

In practice, the hard part wasn’t the strategy. It was the humans.

Tessera’s culture was built around patents, enforcement, and negotiations. DTS’s world revolved around engineers, content partners, and shipping technologies that had to work perfectly inside real consumer products. The merger stitched together what critics dismissed as “patent trolls” and “product people”—two tribes with different instincts, incentives, and vocabulary.

In February 2017, Tessera Holding Corporation changed its name to Xperi Corporation. The new name was meant to signal a new chapter. But changing the sign on the building is easy. Getting a company to genuinely evolve is something else entirely.

IV. The TiVo Mega-Merger: Doubling Down on IP (2019–2020)

TiVo was once the most magical word in television. For a brief stretch in the early 2000s, “TiVo it” became a verb—the way “Google it” did for search.

The company started in 1997, incorporated as Teleworld, Inc. by Jim Barton and Mike Ramsay, both veterans of Silicon Graphics and Time Warner’s Full Service Network digital video system. The original plan wasn’t even a DVR. They were aiming at a home network device, until Randy Komisar pushed them toward a sharper idea: record digitized video onto a hard drive and pair it with a monthly service.

What shipped in early 1999 changed TV forever. TiVo was one of the first two DVRs to hit the market, arriving around the same time as ReplayTV. And once consumers got a taste of pausing live television, rewinding to catch what they missed, and skipping through commercials, there was no going back. TiVo didn’t just build a product—it rewired expectations.

But TiVo ran into a brutal reality: the companies that controlled distribution could copy the magic. Cable and satellite providers baked DVR functionality into their own set-top boxes and bundled it into existing service plans, often cheaper than buying a standalone TiVo. TiVo’s brand stayed iconic, but its leverage eroded, and the company had to evolve to survive.

By 2016, that evolution had led TiVo to become primarily a patent-licensing operation. On April 29, 2016, Rovi Corporation acquired TiVo Inc. for $1.1 billion. The combined company operated under the TiVo name and held over 6,000 pending and registered patents.

There’s an irony here that feels almost too perfect. Rovi was the renamed successor to Macrovision—the company best known for copy protection on VHS tapes. So TiVo, the hardware pioneer that taught the world to time-shift television, ended up inside a business that specialized in monetizing intellectual property, and then lent its famous brand to the whole enterprise.

By the time Xperi came calling in late 2019, the Rovi-era TiVo was already thinking about splitting itself into separate product and IP businesses to unlock value. Instead, it chose a different route: merge.

Xperi Corporation and TiVo Corporation announced a definitive agreement to combine in an all-stock transaction representing roughly $3 billion of combined enterprise value. The pitch was ambitious: a leading consumer and entertainment technology business, paired with one of the industry’s largest IP licensing platforms spanning entertainment and semiconductor intellectual property. After closing, Xperi shareholders would own about 46.5% of the combined business and TiVo shareholders about 53.5%.

On paper, the thesis was clean. Put DTS audio together with TiVo’s video and discovery capabilities, then stack both on top of an enormous patent base. The combined company would have more than 10,000 patents and patent applications, and enough licensing reach to feel unavoidable across the entertainment stack.

The merger closed on June 1, 2020. The combined entity operated as Xperi Holding Corporation, positioning itself as one of the world’s largest IP and product licensing companies.

And then reality hit—fast.

COVID-19 landed right in the middle of integration, forcing remote work at the exact moment the company needed tight coordination and trust. Instead, the combined business found itself managing two separate licensing operations, product groups selling into overlapping customer sets, and a sprawling collection of brands that could confuse even people who lived and breathed the industry.

V. The Great Split: Product vs. IP (2020–2022)

Within months of closing the TiVo merger, Xperi’s leadership ran into an uncomfortable truth: Wall Street hates conglomerates—especially the kind that mixes real products with a litigation-flavored licensing engine. The “sum-of-the-parts” story wasn’t lifting the stock. It was weighing it down.

The answer was hiding in plain sight, borrowed from the same idea TiVo had been toying with before the merger: split the company in two, and let each half stand on its own.

In 2022, Xperi Holding Corporation’s board approved the details and timing of a spin-off that would separate the product business from the IP licensing business. Shareholders would receive shares of the new Xperi Inc. in a pro rata dividend distribution. The company set the spin for around October 1, 2022, and, once completed, the remaining business would retain no ownership interest in Xperi Inc.

They made a bit of theater out of it. Xperi Inc. rang the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange to mark its debut as an independent, publicly traded company. Later that same day, Adeia Inc.—the newly renamed IP licensing business—rang the closing bell at the Nasdaq MarketSite.

The separation created two distinct companies:

Xperi Inc. (NYSE: XPER) - The product company, retaining DTS audio technologies, HD Radio, TiVo OS/platform operations, and the consumer-facing technology businesses.

Adeia Inc. (Nasdaq: ADEA) - The IP licensing operation, keeping the patent portfolios and litigation-driven licensing revenues.

And Xperi Inc. needed a leader who could credibly sell “products” as the main event—not the side dish. That leader was Jon Kirchner. Before Xperi, he had been Chairman of the Board at DTS starting in 2010 and served as its CEO beginning in 2001. Under his leadership, DTS grew from a small startup into a global player, generating more than $190 million in licensing revenue.

Now Kirchner took the helm of the newly independent, product-focused Xperi Inc. The mission was as clarifying as it was unforgiving: build a durable product business around legacy brands, in markets that don’t hand out second chances.

Was this a clean slate—or just rearranging deck chairs? The market’s initial reaction leaned skeptical. Xperi Inc. inherited names with real history, but also the nagging perception that their best days were behind them. And the split removed the safety net. No more patent fortress to fall back on. If Xperi was going to win, it would have to win the hard way: by shipping, integrating, and earning its place in the next generation of devices.

VI. The Automotive Pivot: HD Radio & Connected Car (2015–Present)

While TiVo’s consumer decline grabbed the headlines, a very different story was quietly playing out in the dashboard. HD Radio—a technology most drivers couldn’t name if you put it on a quiz—became standard equipment across much of the North American auto industry.

The foundation was laid by iBiquity, the company behind HD Radio. Formed through the merger of USA Digital Radio and Lucent Digital Radio, iBiquity was a privately held intellectual property business based in Columbia, Maryland, backed by investors spanning technology, broadcasting, manufacturing, media, and finance. In 2002, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission selected iBiquity’s system as a digital audio broadcasting method for the United States.

HD Radio’s pitch was straightforward for listeners and powerful for broadcasters: FM and AM stations could transmit clear digital audio alongside their existing analog signals. And it wasn’t just about fidelity. The technology also enabled “multichannel” broadcasts—HD2 and HD3 subchannels—giving stations more room to program additional content without needing new frequencies.

Automotive turned out to be the perfect wedge. In September 2005, HD Radio entered the vehicle market as an option in BMW’s 2006 7 Series and 6 Series models, which BMW Group called “one of the most significant advances in radio broadcasting history” at the time. Over the years that followed, it went from novelty to expectation. Today, HD Radio comes standard in all BMW models in the U.S.

Then came the deal that put HD Radio inside Xperi’s orbit. On September 2, 2015, iBiquity announced it would be acquired by DTS for $172 million—bringing HD Radio’s broadcast platform together with DTS’s audio technology and industry relationships.

DTS was explicit about the playbook: automotive penetration. When it announced the acquisition, the company pointed to how deeply HD Radio had already pushed into OEM programs. Every one of the 36 major auto brands serving the U.S. market offered HD Radio on at least some vehicles, often as standard equipment. And by 2014, the technology was built into roughly a third of cars sold in the U.S.

By 2024, though, Xperi’s automotive opportunity had grown far beyond “digital radio.” The bet shifted from simply being in the tuner to becoming part of the connected car’s entertainment layer. At CES 2025, DTS said its DTS AutoStage platform had been integrated into more than 10 million vehicles across 146 countries, including more than six million vehicles in North America using both DTS AutoStage and HD Radio. AutoStage is positioned as a connected-car entertainment platform that blends traditional broadcast with IP-delivered content into a single, unified experience.

The momentum shows up in HD Radio’s own scale, too: the North American standard for digital radio has now been implemented in more than 100 million vehicles. And major OEMs have continued to adopt the broader platform—Ford Motor Company, for instance, is incorporating DTS AutoStage into certain North American vehicles starting with the 2024 Lincoln Nautilus.

This is also where Xperi’s economics start to look very different from consumer electronics. In cars, “winning” doesn’t mean you ship next quarter. Design wins can take three to five years to appear in production vehicles, and once the tech is designed in, it tends to stay for the life of the model—often seven years or more. That creates visibility and stickiness, but it also demands patience, because the revenue arrives long after the press release.

Xperi has said it increased its footprint goal for DTS AutoStage to more than 15 million cars, producing over $20 million in revenue. Connected car is the company’s clearest growth prospect—but it comes with a built-in lag: the gap between excitement about design wins and the slow, steady reality of revenue recognition.

VII. Streaming & Smart Home: TiVo OS & Platform Business (2020–Present)

After the split, Xperi inherited a famous name—and a hard problem: what do you do with TiVo when you no longer own the patent tollbooth that helped keep the lights on?

The bet became TiVo OS: a white-label smart TV operating system meant for the manufacturers who don’t have a Tizen or a webOS of their own, but also don’t want to hand the whole living room over to Roku, Amazon, or Google. If you’re a TV brand, the OS isn’t just software. It’s your relationship with the viewer. It’s the home screen. It’s content discovery. And, increasingly, it’s where advertising and data value gets captured.

That’s the wedge TiVo is pitching into.

In Europe, TiVo OS has been rolling out through OEM partners. Smart TVs Powered by TiVo are available across 15 European countries, spanning 17 TV brands including Bush, Daewoo, Digihome, Panasonic, Sharp, Telefunken, and Vestel. At IFA 2024, TiVo planned to showcase the OS across six of those already-live partners—less a splashy launch than a signal that the platform is getting real distribution.

The value proposition is aimed at a very specific gap in the market. At the top end, Samsung has Tizen and LG has webOS. At the low end, many manufacturers simply license Roku or Android TV and call it a day. But for mid-tier brands, that “easy button” can come with a long-term cost: when you adopt someone else’s platform, you often give up a meaningful chunk of the economics—especially ad revenue—and you weaken your direct connection to the customer.

Xperi also started pushing TiVo OS back into the U.S. TiVo announced it would enter the American television market with Sharp Home Electronics Company of America, with the first Sharp Smart TV Powered by TiVo expected to be available to U.S. consumers as soon as February 2025. The TV is positioned as a premium set—Ultra High Definition, High Dynamic Range, a 55" QLED screen, Dolby Atmos, and three HDMI ports—designed to reinforce Sharp’s quality reputation while introducing TiVo’s software layer to U.S. living rooms.

Underneath all of this is the monetization engine Xperi actually cares about: advertising. TiVo Platform Technologies said its TiVo One cross-screen advertising platform reached more than 4 million monthly active users a little over a year after launch, positioning TiVo as incremental reach for advertisers—audiences that are net-new, not just a reshuffling of the same viewers across the same big platforms.

And TiVo OS itself has been spreading. Xperi has said it’s been adopted by dozens of TV brands and is reaching consumers in more than 40 countries, with particularly strong growth in the UK, where smart TVs Powered by TiVo are available at four of the nation’s top five consumer electronics retailers.

But the battlefield here is unforgiving. In the U.S., TiVo isn’t just competing with other “TV OS” offerings. It’s competing with entire ecosystems: Samsung and LG’s in-house platforms, Vizio (in the process of being acquired by Walmart), and the scale players—Roku, Google (Android TV/Google TV), Amazon (Fire TV), and Xumo, the Comcast-Charter streaming joint venture.

On the pay TV side, Xperi has also been leaning on IPTV as legacy cable continues to shrink. TiVo ended the year with 1.9 million IPTV subscribers, and Kirchner expected that to reach 2.4 million by the end of 2024.

Which leaves the question hanging, and it’s the one investors keep circling back to: can TiVo become a true platform business in a world dominated by giants with distribution, data, and ad-tech at massive scale—or is it a beloved legacy brand trying to punch above its weight?

VIII. IMAX Enhanced & Premium Audio: The Content Play (2018–Present)

In a world crowded with home theater logos and “certified” badges, Xperi went looking for a shortcut to meaning—something consumers would instantly recognize. It found one in IMAX, the brand that’s basically shorthand for “this is what the director wanted you to feel.”

In September 2018, Xperi (through DTS) and IMAX launched IMAX Enhanced, a certification and licensing program for the next generation of home entertainment. The pitch was simple: pair IMAX digitally re-mastered 4K HDR content with DTS audio technologies, and then make sure the devices that play it—TVs, AV receivers, sound systems, and more—actually meet performance standards set by IMAX and DTS engineers, along with Hollywood technical specialists.

It wasn’t a small, niche rollout, either. The program launched with heavyweight partners, including Sony, Sony Pictures, Paramount, and Sound United brands like Denon and Marantz. The goal was to create a premium tier for “immersive sight and sound” at home—something that could cut through the sameness of modern TVs and soundbars.

And it did, at least in moments where distribution showed up. IMAX Enhanced content is now streaming on Disney+, and for the first time, movies available in IMAX Enhanced on Disney+ feature IMAX Enhanced sound with DTS:X.

But this is also where you can see Xperi’s biggest structural problem: premium audio isn’t just a technology contest. It’s an ecosystem contest—and Dolby has built the ecosystem.

Dolby Atmos’s advantage over DTS:X isn’t that it exists. It’s that it’s everywhere. It’s installed in multiplexes, supported across a broad range of home theater hardware, and widely offered by major streaming platforms, including Netflix, Disney+, and Apple TV+.

DTS:X, by comparison, has a smaller footprint. It shows up with major AV receiver makers like Denon, Marantz, Yamaha, and Sony, and it’s present on many Blu-ray releases. But on streaming, where most consumers now experience premium audio, DTS:X support is far more limited—essentially confined to Disney+ and Sony Pictures Core (formerly Bravia Core), and even then largely under the IMAX Enhanced banner.

That imbalance hangs over everything Xperi is trying to do in premium content tech. DTS was founded to compete with Dolby for surround-sound supremacy, famously breaking through when Steven Spielberg chose DTS for Jurassic Park, and then expanding into consumer hardware by 1996. And yes, plenty of enthusiasts still argue DTS can sound better, in part because it encodes at higher bit-rates.

But this is the recurring lesson of Xperi’s story: technical merit doesn’t guarantee market power. In standards-driven businesses, distribution and default settings beat “better” more often than engineers want to admit.

IX. The Inflection Point: Surviving the Streaming Plateau (2022–2025)

Post-split, Xperi hit a harsh reckoning: the business was suddenly easier to understand—and harder to excuse.

In 2024, Xperi generated $493.69 million in revenue, down from $521.33 million the year before. The company still reported a loss, but it was much smaller than in 2023.

That slide wasn’t the result of one bad bet. It was the combined weight of three problems happening at once: pay TV subscribers continuing to fall, consumer electronics licensing that could be strong one quarter and soft the next, and new growth initiatives—especially in platforms—taking time to ramp.

By Q3 2025, the pressure was showing up clearly in the numbers. Revenue for the quarter ending September 30, 2025 was $111.63 million, down 16% year-over-year. Over the last twelve months, revenue totaled $453.96 million, a decline of 10.74% from the prior year.

And then came the part every turnaround eventually reaches: cost cuts.

In its Q3 2025 earnings report, Xperi said it would eliminate roughly 250 jobs over the next few months as part of a broader restructuring. The company approved the plan on November 1, 2025, framing it as a move to improve cost efficiency and align operations with long-term strategy and current market conditions. The layoffs were expected to roll through the first half of 2026.

The scope was meaningful: about 250 employees, or roughly 15% of the workforce, with the company targeting $30 million to $35 million in annual savings by the end of 2026.

The pain was most visible in pay TV. In Q3 2025, the segment’s revenue fell 39% compared with Q3 2024—an acceleration of a decline that had been expected, but still hit hard.

Even with that backdrop, management tried to keep the narrative anchored on what was still working—especially the TiVo One media platform. TiVo One reached 4.8 million monthly active users, and Xperi reported TiVo One ARPU of $8.75, calculated as a trailing four-quarter average at quarter-end. Management reiterated its target of reaching $10 ARPU for TiVo One in Q4 2025.

"By the end of the third quarter, we achieved nearly all of our strategic growth goals for 2025," said Jon Kirchner, chief executive officer of Xperi. "We reached 4.8 million monthly active users on the TiVo One platform, added our tenth TiVo OS partner, and signed a number of new monetization partnerships."

And despite the turbulence, the company held the line on its outlook. Xperi reiterated its 2025 annual revenue guidance of $440 million to $460 million, along with an adjusted EBITDA margin target of 15% to 17%.

X. The Business Model Deep Dive

By now, you can see why Xperi is so hard to value. It isn’t one business. It’s four businesses riding four different curves, with four different “clocks” for how revenue shows up.

Pay TV is still the biggest contributor, but it’s also the most obviously melting ice cube. This is the legacy world of program guides, DVR licensing, and operator relationships—revenue that can be predictable, but trends down as cord-cutting keeps grinding. The bright spot is IPTV, where some regional operators are still upgrading and modernizing, giving Xperi a partial offset even as the old model shrinks.

Consumer Electronics is DTS in living rooms: audio licensing to device makers, IMAX Enhanced certifications, and DTS Play-Fi wireless audio. The catch is that this segment doesn’t behave like a smooth subscription business. It can be choppy, because it’s tied to large licensing deals and contractual structures like minimum guarantees. Xperi felt that firsthand when the Panasonic minimum guarantee arrangement expired—revenue didn’t gently taper; it dropped, and the comparison showed up immediately.

Connected Car is the growth story, but it plays out on automotive time. HD Radio generates per-vehicle royalties across North American production, and DTS AutoStage tries to expand the opportunity from “a better radio tuner” into a broader in-cabin entertainment platform. The direction is clear; the monetization is still early, and design wins don’t instantly translate into reported revenue.

Media Platform is the prove-it segment. It includes TiVo OS licensing and advertising, TiVo+ as the streaming service layer, and connected TV advertising through TiVo One. The bet here is straightforward: take the installed base and turn it into a scaled advertising business. The question is whether Xperi can build that kind of platform economics without the distribution advantage of the giants it’s up against.

Put it together and the model becomes a blend: per-unit royalties (HD Radio and DTS), minimum guarantees (especially in consumer electronics), recurring subscriptions (IPTV), and emerging advertising (TiVo One). Strategically, everything comes back to the same tension: Xperi is trying to transition from classic licensing checks to recurring platform and advertising revenue—without losing the cash flow that’s been paying the bills.

That’s also why customer concentration matters so much. A handful of big relationships can swing results. When a major deal rolls off—like Panasonic’s minimum guarantee did—the impact isn’t theoretical. You see it in the next quarter.

The encouraging part is that the cash flow story has started to stabilize. Free cash flow came in at $2 million, the second consecutive quarter of positive free cash flow. Cash and cash equivalents ended the quarter at $97 million, up $2 million from the prior quarter.

XI. Competitive Landscape & Strategic Position

Zoom out, and Xperi’s competitive set looks almost unfair. It isn’t fighting one rival. It’s fighting several—each in a different arena, each with a different kind of advantage.

Audio Technology: Dolby is the heavyweight. It has Atmos, Vision, and something even harder to replicate: decades of being the default “premium” badge consumers recognize and studios design around. That brand and ecosystem show up in how the market values Dolby. DTS, meanwhile, still has real credibility—especially with enthusiasts—but it’s disadvantaged where it matters most today: broad streaming support and everyday brand pull outside home theater circles.

Automotive Infotainment: This is a stack war. Qualcomm increasingly owns the compute layer. Harman (Samsung) sells integrated end-to-end systems that can bundle audio, infotainment, and software into one OEM-friendly package. NXP and Texas Instruments are entrenched across semiconductors and connectivity. Xperi’s edge is specific and meaningful—HD Radio is the only FCC-approved digital radio standard in North America—but the risk is structural: as OEMs adopt more integrated, one-stop platforms, standalone radio licensing could get squeezed to the margins.

Smart TV Platforms: Here, scale is the whole game. Roku leads in North America. Amazon Fire TV and Google’s Android TV fight for position, while Samsung and LG defend their own walled gardens with proprietary platforms. TiVo OS is aimed at the manufacturers caught in the middle—brands that want a modern smart TV experience and platform economics without handing the keys to Big Tech. The problem is that TV platforms reward the biggest players disproportionately: more scale brings more content leverage, more ad demand, better recommendations, and more distribution.

HD Radio: This is one of Xperi’s clearest moats on paper. HD Radio is the sole FCC-approved digital broadcast standard for AM/FM in the U.S., and it’s widely built into vehicles from major automotive brands. The question isn’t whether the standard is real—it is. The question is whether broadcast radio, as a consumer habit, stays relevant as streaming becomes the default audio experience.

Where Xperi wins: when it can embed itself into standards and production cycles—HD Radio in cars, audio tech inside devices—where switching costs and long OEM timelines create stickiness. It also benefits from deep technical know-how and the lingering halo of the TiVo brand.

Where Xperi struggles: wherever ecosystems and default distribution matter most. Platform giants lock in users, content partners, and advertisers at a scale Xperi can’t match. And without massive consumer marketing power, it’s hard to turn “better tech” into “must-have demand.”

XII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Xperi is competing in markets where the default winners are either massive ecosystems or entrenched standards. Dolby leads in premium audio with deeper studio relationships and broader platform support. In smart TV platforms, Roku, Amazon, and Google operate at a different scale entirely. And across consumer electronics, more manufacturers are trying to pull key capabilities in-house instead of paying ongoing licensing fees.

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM

The technical and commercial hurdles are real—building a credible audio format, getting it adopted, and qualifying it for automotive programs takes time and expertise. But “hard” doesn’t mean “protected.” Open-source efforts can reshape the economics fast. Google’s emerging Eclipsa Audio, developed with Samsung under the Alliance for Open Media, is a reminder that a well-funded coalition can push the industry toward “good enough and free,” especially if it comes bundled into existing platforms.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Xperi doesn’t depend on physical manufacturing. Its constraints are talent, R&D capacity, and content and distribution relationships—competitive, yes, but not typically single-point bottlenecks that can hold the company hostage.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

The buyers are concentrated and sophisticated. Automotive OEMs have scale and long procurement cycles. Consumer electronics manufacturers are fighting for margin. Streaming services can simply choose which formats they bless—and once a platform picks a standard, it becomes very hard for an alternative to break in. In that kind of environment, large customers can and do push pricing and terms.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

Substitutes are everywhere: proprietary audio approaches like Apple Spatial Audio and Sony 360 Reality Audio, integrated platform bundles that make standalone licensing feel redundant, and the ever-present “good enough” baseline that comes at no incremental cost. The biggest substitute pressure is structural: streaming has effectively standardized around Dolby Atmos, which makes DTS alternatives harder to justify unless there’s a specific distribution channel—like IMAX Enhanced—creating demand.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

1. Scale Economics: WEAK

Xperi operates without the volume advantage of the category leaders. In licensing and platform businesses, scale isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s the engine that spreads R&D and sales costs, attracts partners, and funds the next cycle of adoption. Xperi has to play the same game with a smaller base.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

Xperi benefits from a quieter kind of network effect: institutional adoption. Once HD Radio is designed into a vehicle platform, it tends to stay. TiVo’s metadata and discovery can improve with usage. But these are not viral, consumer-driven network effects; they don’t naturally snowball into runaway winners.

3. Counter-Positioning: WEAK

Xperi isn’t attacking incumbents with a model they can’t follow. More often, it’s trying to defend and extend positions in categories where larger players can offer similar functionality—then bundle it, subsidize it, or make it the default.

4. Switching Costs: STRONG

This is the clearest moat. Automotive design cycles can run three to five years before a feature reaches production, and once it’s in, ripping it out is expensive and disruptive. Certifications like IMAX Enhanced and DTS:X also create real friction: manufacturers invest time and engineering effort to qualify a product, and they don’t want to redo that work unless the payoff is obvious.

5. Branding: MIXED

TiVo is still famous—but increasingly as a memory rather than a forward-looking platform. DTS has credibility with enthusiasts, but it’s not the mainstream “default” in the way Dolby is. And Xperi itself, as a corporate name, is effectively invisible to consumers—which limits how much it can pull demand through the market.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

After the Adeia spin-off, the patent fortress is smaller. What remains is meaningful expertise in audio processing, broadcast technology, and metadata—valuable, but not entirely unique. The standout exception is HD Radio’s regulatory position: it remains the only FCC-approved digital broadcast standard for AM/FM in the U.S., which is a genuine advantage in automotive.

7. Process Power: WEAK

There’s no clear sign that Xperi has a unique operating system—some proprietary way of executing that competitors can’t copy. It doesn’t manufacture, and from the outside, it’s hard to argue it has distinctly superior processes in R&D or go-to-market compared with much larger rivals.

Overall Assessment: Xperi has moats, but they’re narrow. Its real defensibility comes from switching costs in automotive programs and HD Radio’s unique regulatory position. What it lacks—scale economics, broad network effects, and mass-market brand power—is exactly what typically separates platform winners from everyone else.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Automotive is massive, and Xperi is well-positioned. Xperi has raised its DTS AutoStage footprint goal to more than 15 million cars, with the platform already producing over $20 million in revenue. Design wins with BMW, Ford, and other major OEMs can become durable revenue as those vehicles actually reach driveways. And if Xperi can expand from one-time HD Radio royalties into recurring AutoStage software subscriptions, the economics get a lot more interesting.

Software-defined vehicles create a real recurring revenue opening. As cars start to behave more like smartphones—over-the-air updates, app-like experiences, subscription features—the entertainment layer turns into sticky infrastructure. That’s the kind of layer that can keep paying for years, not just once at the factory.

TiVo OS has a credible “anti-Big Tech” lane. For regional TV manufacturers, picking an OS isn’t just a technical choice—it’s choosing who owns the home screen and the economics behind it. Some may prefer TiVo’s positioning as an “unbiased” alternative to Roku, Amazon, and Google. TiVo OS has been adopted by dozens of TV brands and reaches consumers in more than 40 countries, giving Xperi at least a fighting chance at distribution.

The valuation looks detached from the underlying assets. With a market cap under $400 million and nearly $100 million in cash, Xperi trades for less than 1x revenue—far below the kind of multiple Dolby commands. If the business stabilizes, or if TiVo’s platform monetization starts to show up consistently, the stock doesn’t need perfection to re-rate.

HD Radio is a regulatory moat. Being the FCC-approved digital broadcast standard for AM/FM in North America gives Xperi a built-in royalty stream tied to automotive production. Broadcast radio may be a long-term decliner, but decline in the auto fleet tends to play out over many years, not quarters.

Management looks like it’s pulling levers that matter. The company beat analysts’ EPS expectations by 14 cents per share. Restructuring and cost discipline, sharper focus on growth areas, and back-to-back quarters of positive free cash flow are the kinds of signals investors look for in a turnaround.

The Bear Case

Xperi is subscale in winner-take-most markets. These categories concentrate brutally. Roku and Amazon Fire TV are gatekeepers in streaming. Dolby is the default in premium audio. In platform-style businesses, being “pretty good” is rarely enough, and second-tier players often get squeezed out.

Dolby Atmos has effectively won the streaming standard war. On major streaming platforms, Atmos is everywhere. DTS:X support is limited—basically to Disney+ and Sony Pictures Core. If streaming is the primary way consumers experience premium audio, DTS is fighting uphill with fewer allies.

TiVo may not have a realistic path to platform scale. Roku has more than 80 million active accounts, and Amazon and Google can bundle TV platforms into much bigger ecosystems. TiVo OS, even at 4.8 million monthly active users, is still tiny in a market where distribution scale drives content leverage, ad demand, and default placement.

Automotive revenue arrives slowly, and time isn’t free. Design wins can take three to five years to turn into meaningful production revenue. While Xperi waits, it still has to fund product development and compete against better-capitalized players—and the market can shift under its feet before those wins pay out.

The R&D burden is heavy for a company this size. Audio formats, TV platforms, and in-car systems all require ongoing investment just to stay relevant. Xperi doesn’t have the R&D scale of Dolby, Qualcomm, or the platform giants, which means it has to pick its bets carefully—and hope the industry doesn’t force it to fight on too many fronts at once.

The corporate whiplash is a red flag. Multiple rebrands and restructurings, plus a complicated lineage (Tessera to Xperi Corporation to Xperi Holding to Xperi Inc.), can read less like reinvention and more like instability—an organization constantly changing shape without building a clean, durable narrative.

HD Radio’s consumer pull is still questionable. Even with deep automotive penetration, HD Radio never became a consumer brand. And if listening keeps shifting toward streaming and podcasts, the long-term relevance of broadcast radio—and the royalties attached to it—faces real uncertainty.

XIV. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

The licensing-to-product trap is real. Tessera built a highly profitable IP licensing business, but the skills that win in patent licensing don’t automatically translate to building great products. Buying DTS and TiVo brought real technology and valuable brands—but it also brought different cultures, different customer expectations, and different definitions of success. Xperi is a reminder that M&A can look perfectly logical in a slide deck and still break down in execution.

Standards only matter when they become defaults. DTS may be comparable to—maybe even better than—Dolby in raw audio quality. But Dolby won what matters: broad adoption across streaming services, gaming consoles, and mobile devices. In standards businesses, technical excellence is table stakes. Distribution is the moat. Being right matters less than being everywhere.

Conglomerate discounts are not a theory—they show up in the stock. Public markets tend to reward focus and punish complexity. The Xperi/Adeia split was an admission of that reality. But the painful part of this story is timing: the market imposed the discount for years before the company fully embraced the need for clarity. For founders, the question isn’t just “can we own multiple businesses?” It’s “will investors ever value them that way?”

Customer concentration turns a single contract into a cliff. When one minimum guarantee arrangement—like Panasonic’s—rolls off and revenue falls sharply, the problem isn’t a bad quarter. It’s a fragile model. Resilience usually comes from breadth: more customers, more end markets, and more revenue types so one renegotiation doesn’t change the whole trajectory.

Scale compounds in platform businesses—against you, if you don’t have it. TiVo isn’t competing with scrappy upstarts. It’s competing with Roku, Amazon, and Google—companies with bigger balance sheets, deeper content relationships, and oceans of user data. Platform economics reward the leaders and starve the followers. Second place isn’t just uncomfortable; it can be unsustainable.

Turnarounds can wear a company out. Xperi has lived through pivot after pivot: semiconductor IP to consumer tech, standalone to the TiVo merger, integrated conglomerate to spin-off, licensing-first to product-first. Each shift takes a toll—management attention gets split, employees lose the thread, and resources get consumed just getting to the next starting line. The durable advantage isn’t constant reinvention. It’s a coherent strategy that survives disruption without rebuilding the company every few years.

XV. Epilogue & What's Next

“The first quarter marked the entry of the TiVo One ad platform into the North American market through updates to our video-over-broadband device footprint and the launch of Sharp TVs powered by TiVo,” said Jon Kirchner, chief executive officer of Xperi. “We are very pleased with the expanded rollout and adoption of our monetization platform, driving our installed base to 2.5 million monthly active users primarily in Europe. Feedback on the products from our TV and broadband operator partners, as well as from end users, has been extremely positive.”

If you’re looking for the next lever Xperi might pull, it’s AI—but it’s early. At CES 2025, DTS Clear Dialogue, a new on-device solution that uses AI-based audio processing to make dialogue easier to hear on TVs, won three technology and innovation awards from industry-leading publications. Beyond that, the roadmap is familiar: voice assistants, better personalization and recommendations, and in-car AI experiences. The catch is just as familiar, too—Xperi is chasing these openings in a world where tech giants are spending billions to own them.

Kirchner also pointed to the next chapter in connected car: turning footprint into monetization. “Importantly, as we have now built meaningful scale, we have initiated collaboration with several leading audio media companies to monetize this unique and highly valuable footprint. The intended partnership between Xperi and audio media companies will seek to launch targeted advertising trials on the AutoStage platform in the U.S. and U.K.”

Key metrics to watch: 1. TiVo One Monthly Active Users — The leading indicator that matters most. If MAUs keep climbing past five million, it strengthens the case that TiVo is becoming a real platform. If growth stalls, the ad model never reaches the scale it needs.

-

Connected Car Revenue Recognition — Automotive is slow-cook by design. The real tell isn’t press releases about design wins; it’s whether quarterly connected car growth starts showing those wins landing as revenue.

-

Free Cash Flow — Xperi has now delivered positive free cash flow in consecutive quarters. Whether it can keep doing that determines if it can fund the next phase—or if it’s forced into permanent triage.

Potential outcomes: - Steady-state niche player: Xperi holds its ground, anchored by HD Radio and automotive, and settles into a stable-but-unloved profile around roughly $450 million in revenue—modest cash flow, low multiples, little fanfare.

-

Acquisition target: At current valuations, Xperi’s HD Radio position, automotive relationships, and TiVo brand could look like a bargain to the right buyer—whether that’s a strategic player looking to deepen its in-car stack, or private equity looking for durable cash flow.

-

Continued struggle: If the platform bets don’t scale fast enough, and the legacy businesses keep shrinking, the math can get unforgiving. In that scenario, existential pressure builds over the next three to five years.

Final reflections:

Xperi’s story is what happens when you build in industries where “good” isn’t enough—where standards, distribution, and default placement decide the winners. TiVo invented the DVR and became a verb, then watched cable companies copy the feature and streaming make the whole category feel like history. DTS put the Jurassic Park roar into theaters, then saw Dolby become the streaming default. Tessera’s patents helped enable the smartphone era, then ran into the simplest law of all: patents expire.

What’s left is a company with real technology, real brands, and real revenue—yet one that’s constantly fighting uphill against competitors with more scale, more leverage, and more control of the ecosystem. It powers billions of devices and still gets valued like a rounding error.

So the ending—at least for now—is still unwritten. For investors, Xperi is either deep value or a value trap, and the difference comes down to timing: can the platform and automotive initiatives compound before the legacy segments fall away? For founders, it’s a case study in how hard it is to evolve from licensing to products—and how unforgiving platform economics can be.

The company that taught the world to pause live TV now has to prove it can unpause itself.

XVI. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form References:

-

Xperi Inc. Investor Relations — SEC filings, earnings transcripts, and investor presentations are the most direct window into the company’s strategy, operating metrics, and how management explains the business.

-

"The Innovator's Dilemma" by Clayton Christensen — A useful lens for understanding how TiVo could invent the DVR category and still get disrupted by the very ecosystem it helped reshape.

-

"7 Powers" by Hamilton Helmer — The competitive advantage framework referenced in this story, and a strong template for pressure-testing any business that lives or dies on moats.

-

Dolby Laboratories Investor Materials — The cleanest comparison point: how the category leader describes its ecosystem strategy, and why the market rewards it so differently.

-

Trade Publications: CE Pro, Automotive News, Streaming Media Magazine — The on-the-ground reporting that tracks shifts in connected car, home theater, and streaming platform wars—where Xperi’s wins and losses actually show up.

-

Patent Litigation Databases — To understand Xperi’s lineage, you have to follow the lawsuits and settlements; the IP history is part of the operating history.

-

TiVo Oral History and Early DVR Innovation Coverage — Sources like IEEE Spectrum capture the technical breakthroughs, product decisions, and early-era context that made TiVo iconic.

-

HD Radio Alliance Materials and iBiquity History — Background on how HD Radio became the U.S. digital broadcast standard and how it spread through automakers and broadcasters.

-

Equity Research Reports — Coverage from firms like Raymond James, Rosenblatt, and B. Riley for modeling assumptions, segment breakdowns, and the questions public-market investors keep asking.

-

Podcasts/Interviews with Jon Kirchner — The best way to hear the strategy in plain language, beyond the constraints of quarterly earnings calls.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music