Westlake Corporation: The Quiet Giant of Chemicals and Housing

I. Introduction: The Invisible Empire in Plain Sight

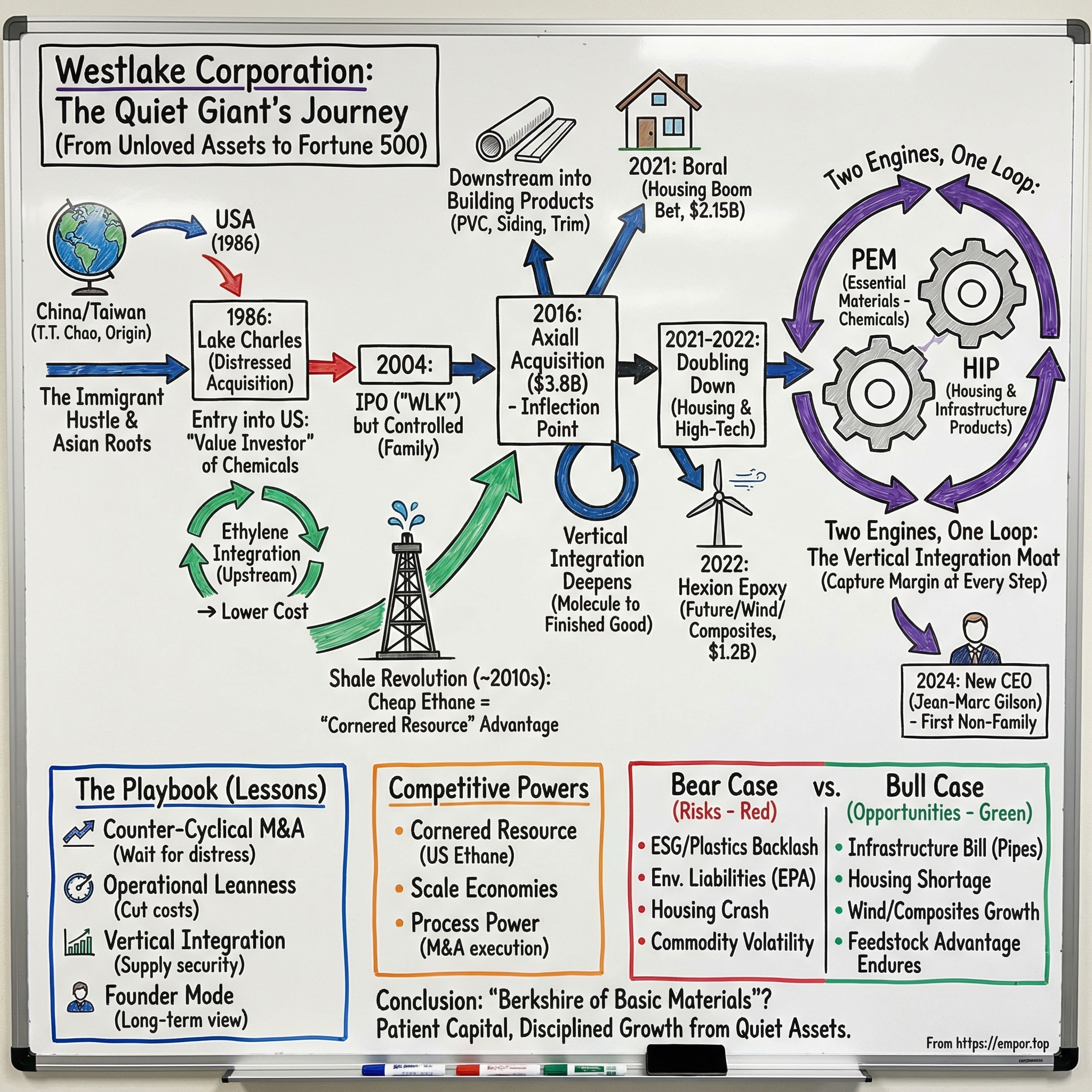

Picture this: you turn on a faucet, and clean water rushes through PVC pipes made by a company you’ve probably never heard of. You look at the vinyl siding that keeps your house sealed against rain and cold. You pass wind turbines on the highway, their blades held together by epoxy resins. The packaging around your groceries, the plastic bottles in your recycling bin, even critical medical devices in hospitals—all of it can trace back, in one way or another, to the same quiet industrial machine headquartered in Houston’s Galleria district.

That machine is Westlake Corporation. It makes petrochemicals, polymers, and building products that sit upstream of everyday life—the stuff other companies turn into the things you actually buy. Westlake is a Forbes Global 2000 company and the largest producer of low-density polyethylene (LDPE) in the United States. In 2024, it generated $12.1 billion in net sales and employed roughly 16,000 people worldwide. And yet, outside of a few industry circles, it remains almost invisible.

That invisibility is the point. Westlake isn’t a consumer brand. It’s infrastructure—physical, chemical, and economic. And its rise isn’t a Silicon Valley story about blitzscaling or a charismatic founder selling a vision. It’s a story about patient capital, buying when everyone else is selling, and then squeezing value out of heavy industrial assets with discipline bordering on obsession.

Westlake was founded in 1986 by the Chao family, who are now among America’s richest, according to Forbes—but they’ve never played the fame game. No flashy public persona. No constant headlines. Instead, they spent decades doing the unglamorous work: acquiring distressed chemical plants, integrating them, cutting costs, expanding into new links of the value chain, and compounding that advantage year after year.

From one polyethylene plant in Lake Charles, Louisiana, Westlake grew into a global materials giant riding some of the biggest forces in modern industry: America’s shale gas boom, the long-run demand for housing and infrastructure, and the escalating debate over plastics—essential modern material or environmental disaster in slow motion.

So if this is an empire hiding in plain sight, how did it get built?

Let’s start where many great American business stories start: with a family leaving behind everything familiar to chase an opportunity in the United States.

II. Origin Story: The Chao Family and the Immigrant Hustle

Westlake’s story doesn’t start in Texas. It starts in Suzhou, China, a canal-laced city with a history stretching back more than two millennia. Ting Tsung “T.T.” Chao was born there in 1921, at a time when China was lurching from crisis to crisis—political collapse, internal conflict, then the upheaval of World War II.

He studied industrial management at Shanghai University and began his career in railroads. But history had other plans. As the Chinese Civil War reshaped the region and Mao Zedong’s forces took power, the Chao family made a life-defining move. In 1946, they left the mainland for Taiwan, part of the wave of refugees that followed the Nationalists’ retreat.

T.T. was about to do in Taiwan what he would later do in the U.S.: spot a structural advantage early, build patiently, and use partners and capital with ruthless practicality.

Building the Asian Petrochemical Industry

In the mid-1950s, T.T. helped launch Taiwan’s first polyvinyl chloride (PVC) business, backed by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). He became its founding president at just 32 and oversaw its rapid expansion.

It’s hard to overstate what that meant in context. Taiwan in the 1950s was still an agricultural economy, heavily dependent on American aid and protection. There was no meaningful petrochemical base. Plastics manufacturing, as an industry, barely existed. T.T. looked at a relatively new material—plastic—and bet that it would become foundational to modern life.

The plant began producing PVC in 1957, contributing to Taiwan’s industrial development. And over time, T.T.’s reputation grew to match the scale of what he’d built. The Chemical Heritage Foundation would later describe him as “a true pioneer of the petrochemical and plastics industries in Asia,” noting that in the difficult postwar years, he was among the first to build one of Taiwan’s most important plastics businesses.

By 1964, he formed The Chao Group, a privately held petrochemical and plastics conglomerate that worked with multinational partners including Gulf Oil, Mobil, and Sumitomo. He had a knack for joint ventures—pairing local execution with global technology and capital long before “globalization” became a business cliché.

And sometimes those ventures produced surprising cultural artifacts. In 1966, a joint venture with Mattel produced the first Barbie dolls. Before Barbie became an American icon, she was, in a very real sense, molded in a Taiwanese plastics factory connected to T.T. Chao.

Over the decades, his network of partners expanded to include companies like Chevron (through Gulf Oil Chemical), Exxon/Mobil, Mitsubishi, Norsk Hydro, Basell, and others. The through-line wasn’t just dealmaking. It was building durable industrial capability—and doing it in a way that made him indispensable to the people he partnered with.

The Move to America: 1986

By the mid-1980s, T.T. had spent roughly thirty years building petrochemical capacity across Asia. He founded plastics and fabrication ventures across the world, including in the United States, Canada, China, and Hong Kong. Later, he also founded the Titan Group in Malaysia, building the country’s first and largest integrated petrochemical complex in Johor.

But the biggest opening was forming in the United States.

Oil prices collapsed in the mid-1980s, and the American chemical industry went into a brutal downturn. The majors that had once treated chemicals as a nice adjacency suddenly wanted out. Assets hit the market. Sellers got motivated. In heavy industry, that’s when generational fortunes get made.

Where most saw a wreck, T.T. Chao saw a once-in-a-cycle entry point.

Westlake was founded in 1986 when T.T. acquired a polyethylene plant in Lake Charles, Louisiana. On September 12, 1986, the Chao family bought the plant from Occidental Petroleum—a distressed sale as Occidental worked to exit parts of the chemical business. T.T. made the move alongside his sons, James and Albert, and Westlake began producing polyethylene at its first U.S. facility that same day.

It’s easy, looking back, to make this sound inevitable. It wasn’t. In 1986, they weren’t buying a hot asset in a growing category. They were buying into an industry that looked broken.

But the logic was clean. In commodities, cost position is destiny. If you can become the low-cost producer, you can survive downturns that wipe everyone else out—and when the cycle turns, you mint cash. Buying a distressed plant from a motivated seller is one of the fastest ways to get that cost advantage.

And even if the full scale of America’s natural gas advantage was still years away, the Chaos were already leaning into the principle that would define Westlake: when the market panics, they go shopping.

III. The Early Era: The Value Investor of Chemicals (1986–2010)

The Bottom-Feeding Strategy

The American chemical industry of the late 1980s and 1990s wasn’t a growth story. It was a clearance sale.

Big oil companies that had piled into chemicals during earlier booms were now trying to get out. Conglomerates were shedding petrochemical divisions. To most investors, the whole sector looked like yesterday’s economy: cyclical, capital-intensive, and permanently out of fashion.

That was exactly what made it interesting to Westlake.

From the start, the playbook was simple and repeatable: buy distressed assets from motivated sellers, run them lean, improve operations, and hold on long enough for the cycle to do the rest. Value investing, but with pipes and furnaces instead of price-to-earnings ratios.

Westlake began with that first polyethylene plant in Lake Charles in 1986. Then it started building out the part of the chain that mattered even more: ethylene. It brought the Petro 1 ethylene plant online in 1991, followed by Petro 2 in 1997—moves that anchored Westlake not just as a plastics maker, but as a serious producer of the raw building blocks of modern materials.

The shift from making polyethylene to owning ethylene capacity is where you really see the logic. To understand why, you need a quick tour of how the petrochemical value chain actually works.

How the Petrochemical Value Chain Works

Start with natural gas coming out of the ground in places like Texas. It’s mostly methane, but mixed in are valuable “natural gas liquids” like ethane, propane, and butane. Processing facilities strip those liquids out.

For many chemical producers, ethane is the prize. Feed it into a cracker—a gigantic industrial furnace—and you break ethane’s molecular bonds to make ethylene. Ethylene is one of the core molecules of the industrial world. Turn it into polyethylene, PVC, antifreeze, and thousands of other products.

Early on, Westlake bought ethylene from other producers and used it to make polyethylene. That works, but it comes with a tax: you’re paying someone else’s margin. Building its own crackers meant Westlake could capture that margin instead. And later, when it integrated into PVC and building products, it would capture even more—repeatedly, on the same underlying molecule.

This was the core of T.T. Chao’s approach: sustained growth through a mix of acquisitions, expansions, and targeted new builds, all in service of integration. The goal wasn’t to be the most glamorous company in chemicals. It was to be one of the lowest-cost producers—and to earn profit at multiple points along the chain.

The IPO: Going Public While Staying Private

By 2004, Westlake was no longer a small, single-plant operator. It was big enough to tap public markets—but it had no interest in giving up control to do it.

On August 10, 2004, Westlake announced the pricing of its initial public offering: 11.8 million shares at $14.50 per share. Trading began the next day on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “WLK.”

The IPO raised net proceeds of $159.1 million. Westlake used that money the way a disciplined industrial operator would: it redeemed $133 million of its 8-3/4% Senior Notes due 2011 and paid down other debt. Not flashy. Strategic. It strengthened the balance sheet and quietly expanded what Westlake valued most: flexibility for the next deal.

And crucially, the Chao family stayed firmly in charge. As of March 10, 2025, TTWF LP and its general partner, TTWFGP LLC, collectively held 72.3% of Westlake’s outstanding common stock, making it a “controlled company” under NYSE rules.

That structure mattered. Westlake could live through ugly cycles and invest for the long term without being yanked around by quarterly expectations or activist pressure. It could stay patient—right up until it was time to strike.

The Shale Revolution: Fortune Smiles on the Patient

While Westlake was methodically building and integrating along the Gulf Coast, a quiet technology shift was brewing in American energy. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing began unlocking massive shale gas reserves. First came “dry” gas. Then the industry pushed into “wet” gas—fields rich in natural gas liquids, especially ethane.

About a decade ago, cheap, natural gas–derived ethane began flowing in volume from these shale formations to U.S. chemical makers. For the first time since the 1990s, gas-based feedstock in the United States was reliably cheaper than the oil-based raw materials used by many producers in Asia and Europe.

The impact was enormous. Ethane—key feedstock for making ethylene—saw its price fall sharply between 2008 and 2012. Costs dropped, profits surged, and the U.S. became one of the most advantaged petrochemical regions in the world, second only to the Middle East.

Now look at Westlake’s positioning. It had spent years building ethylene and polyethylene capacity in Louisiana, right where this wave of cheap feedstock would hit first. While competitors overseas wrestled with higher-cost oil-based inputs, Westlake was sitting on what amounted to a cornered resource: access to some of the cheapest ethylene feedstock in the developed world.

U.S. ethylene prices have generally remained discounted versus international prices, giving Gulf Coast producers a long-term cost advantage and supporting continued capacity expansion.

In other words, the unglamorous strategy worked. Westlake bought and built patiently, stayed integrated, stayed solvent, and then got handed one of the biggest structural tailwinds in global chemicals.

And it still wasn’t done.

IV. Inflection Point: The Axiall Acquisition (2016)

The Setup: Cash Rich but Commodity Bound

By 2015, Westlake was throwing off cash thanks to the shale boom. But it had a problem that money alone couldn’t solve: it was still, at its core, a commodity chemicals business. When oil moved, margins moved. When demand softened, prices fell. A huge portion of Westlake’s fate was still tied to cycles it couldn’t control.

So the next move was obvious, and hard: go downstream. Don’t just sell PVC resin. Sell the products people actually install—pipes, siding, trim—the things that end up in American homes and tend to carry steadier, stickier margins.

The Target: Axiall Corporation

Axiall was a near-perfect fit.

It was a major manufacturer and marketer of chlorovinyls and aromatics. And thanks to its earlier acquisition of Royal Group Technologies, Axiall also had a meaningful building products footprint: piping and siding, window profiles, decking, fencing—the very categories that would pull Westlake closer to end markets.

Axiall itself was the product of a big bet. Georgia Gulf had become Axiall after completing a roughly $2 billion acquisition of PPG Industries’ chlor-alkali and derivatives business in 2013. But the combination wasn’t humming. Integration was rough, the balance sheet was strained, and pressure on management kept mounting.

Westlake looked at that mess and saw what it always looked for: an asset that was strategically valuable, operationally improvable, and available because someone else had lost patience.

The Drama: Hostile Turned Friendly

In spring 2016, Axiall announced it was considering strategic alternatives. Westlake pushed in.

Axiall wasn’t exactly eager at first, and Westlake didn’t wait around. It pursued a proxy contest to replace Axiall’s board—essentially saying, “Work with us, or we’ll take this decision out of your hands.”

That pressure worked. On May 20, Axiall’s CFO told Westlake’s CFO that the company had reopened its data room and asked Westlake to submit a revised proposal by June 3.

A few weeks later, the standoff resolved. On June 10, 2016, Westlake Chemical Corporation and Axiall announced a definitive agreement: Westlake would buy Axiall for $33 per share in an all-cash deal, valuing the business at about $3.8 billion on an enterprise basis, including debt and certain liabilities. This time, it was friendly—unanimously approved by both boards.

The Transformation

Westlake closed the acquisition on August 31, 2016. Overnight, it became the third-largest chlor-alkali producer and the second-largest PVC producer in North America. Westlake projected the deal would be accretive to earnings in the first year and targeted about $100 million in annual cost synergies.

But the real prize wasn’t just scale in chemicals. It was what came with Axiall: Royal Building Products, one of North America’s leading manufacturers of vinyl siding, trim, and mouldings.

This is where the strategy clicks. Royal had been paired with upstream PVC through prior consolidation—raw material feeding finished goods. With Axiall inside Westlake, that vertical integration didn’t just remain intact. It deepened. Westlake could increasingly make the molecules, make the resin, and sell the final product—capturing margin at multiple steps instead of stopping at the factory gate.

The market initially wasn’t sure what to make of it, and plenty of shareholders worried Westlake had paid too much. But the logic of the move became hard to ignore as the business grew sharply in the year after.

More than anything, Axiall proved what Westlake had been building toward for thirty years: the patience to wait for the right moment, the nerve to go hostile if it had to, and the operational discipline to turn a complicated industrial mash-up into a tighter, more integrated machine.

V. Doubling Down on Housing and High-Tech (2021–2022)

The COVID Context

The COVID-19 pandemic created one of the strangest economic whiplashes in modern history. Lockdowns hit industrial demand hard. Then the rebound arrived—supercharged by fiscal stimulus and record-low interest rates—and housing took off. People left dense cities for more space. Homeowners poured money into renovations. The market for anything that went into a house suddenly felt endless.

At the same time, the global supply chain cracked. Materials that had always been “available” became scarce, delayed, or wildly expensive. In that environment, chemical and building products companies that depended on third parties were exposed. Companies with integrated supply—who could feed their own plants and keep products flowing—had a real edge.

Westlake, with operations spanning from feedstock to finished building products, was set up for exactly this kind of moment.

The Boral Acquisition: Betting on the Housing Shortage

In 2021, Westlake completed the acquisition of Boral Limited’s North American building products businesses for $2.15 billion. The deal brought in a portfolio of brands across premium roofing, siding, trim and shutters, decorative stone, and windows—exactly the categories that move when housing and renovation activity is hot.

Boral’s North American building products businesses employed about 4,600 people across 29 manufacturing sites in the United States and Mexico, and generated more than $1 billion in revenue in the fiscal year ended June 30, 2020.

“This transaction effectively doubles the size of our portfolio in the high-growth North American building products segment,” said Westlake President and CEO Albert Chao.

The logic was straightforward: the U.S. has a structural housing shortage measured in the millions of homes. Rates can rise, the cycle can cool, and projects can pause—but the need doesn’t disappear. Eventually, homes still get built and repaired. And when they do, they need roofing, siding, windows, and pipe—products Westlake now made in far greater breadth.

“The North American building products segment, based on market analysis for new construction and remodel and repair, is expected to grow by approximately 15% during the next three years.”

The Hexion Epoxy Acquisition: A Bet on the Future

Then came a curveball—one that signaled Westlake wasn’t just leaning into housing. It was also moving up the value chain.

In February 2022, Westlake completed the acquisition of Hexion Inc.’s global epoxy business for approximately $1.2 billion. Rebranded as Westlake Epoxy, the business focused on specialty resins, coatings, and composites used across a wide range of industries.

This was a meaningful shift. Epoxy is not a basic commodity in the way PVC or polyethylene is. It’s a performance material—more specialized, more engineered, and often sold into end markets where reliability and specifications matter as much as price.

Hexion’s epoxy business served end uses that were both high-growth and tied to “sustainability” themes, including wind turbine blades and lightweight automotive structural components. In the twelve months ended September 30, 2021, it generated about $1.5 billion in net sales.

Why wind turbines? Because modern blades are massive, and their strength comes from composite structures held together with epoxy systems. As renewable energy capacity expands, so does demand for the materials inside the hardware.

“Lightweighting is a critical feature for the manufacture of structural components for automobiles and for renewable energy, particularly the composite blades used by wind turbines, and epoxies are key ingredients for these sustainable products. The industries served by Westlake Epoxy are very attractive.”

The business operated globally across three continents, with eight manufacturing facilities and five research and development labs in Asia, Europe, and the United States.

VI. The Current State: Two Engines, One Loop

The Business Today

Today, Westlake runs on two big engines: Performance and Essential Materials (PEM), and Housing and Infrastructure Products (HIP).

PEM is the chemicals machine. It produces ethylene, polyethylene, styrene, propylene, and other core petrochemicals—the foundational molecules that power a huge share of modern manufacturing.

HIP is where those molecules turn into real-world stuff. This segment makes PVC and then pushes it further downstream into the products you actually see: vinyl siding, trim, decking, railing, stone veneer, and—most importantly—pipe.

What makes the model feel almost unfair is the loop between the two. Westlake starts with natural gas from American shale plays, cracks it into ethylene, turns that into plastics like polyethylene and PVC, and then manufactures PVC into finished building products. Those products end up with customers like Home Depot and Lowe’s, and in the hands of professional contractors.

Every time the material moves to the next step, Westlake keeps more of the economics for itself—margin that, in a less integrated world, would be handed off to suppliers or middlemen. The company can effectively profit multiple times as the same basic feedstock becomes a higher and higher value product.

In pipe, that integration shows up in a very literal way. As the second-largest PVC pipe manufacturer in North America, Westlake produces a broad range of pipe and fittings, including rubber gasketed, solvent weld, and restrained joint. And these aren’t “nice-to-have” products. They go into municipal water and sewer systems, residential plumbing, water wells, mining, and agricultural and turf irrigation—quiet, essential infrastructure that keeps daily life running.

Meanwhile, in siding and trim, Westlake Royal Building Products is the largest extruder of cellular PVC components in North America.

The Leadership Transition

In July 2024, Westlake hit a milestone that would have sounded unlikely for most of its history: it named a non-family CEO.

Jean-Marc Gilson became President and Chief Executive Officer, making him the second CEO of Westlake—and the first from outside the Chao family. He also serves as President and Chief Executive Officer and a Director of Westlake Partners’ general partner.

“I am honored and humbled to become the second, and first non-family, CEO of Westlake,” Gilson said. “I have long admired Westlake as a best-in-class company at the forefront of delivering life-enhancing products through innovation in essential materials and building products.”

Albert Chao, who had served as CEO for 20 years, framed the shift as planned and intentional: “Having served as the CEO of Westlake for the last 20 years, now is the right time to implement our succession plan.”

With the transition, Albert Chao became Executive Chairman of the Westlake Board of Directors. James Chao, the prior Chairman, became Senior Chairman of the Westlake Board of Directors.

Gilson came to Westlake with deep experience in global materials and family-owned enterprise. Before joining, he served as President, Chief Executive Officer, and Representative Director of Mitsubishi Chemical Group Corporation from April 2021 to April 2024. Before that, from September 2014 through December 2020, he was CEO of Roquette Frères, a family-owned leader in plant-based ingredients.

Recent Financial Performance

In 2024, Westlake reported net sales of $12.1 billion. Net income was $677 million, excluding “Identified Items,” and EBITDA was $2.3 billion, also excluding “Identified Items.”

Net income fell from 2023’s $1.1 billion, with management attributing the decline mainly to lower average selling prices—especially in PEM—against a backdrop of weak global industrial and manufacturing activity.

As Gilson put it: “While earnings in our PEM segment were lower compared to 2023 due to lower average sales price as a result of weak global industrial and manufacturing activity, we made important progress during 2024 to improve our cost structure through productivity enhancements.” He also noted demand signals moving in the right direction late in the year: compared to the prior-year period, fourth quarter sales volume grew in each segment, led by 7% sales volume growth in HIP.

VII. The Playbook: Lessons for Builders and Investors

Counter-Cyclical M&A: The Discipline to Wait

The most distinctive feature of Westlake’s strategy is how comfortable it is looking “inactive” for long stretches—building cash, running the plants well, and letting the cycle turn—until the moment to buy finally arrives. The 1986 plant purchase from Occidental came in the middle of an industry collapse. The 2016 Axiall deal landed when Axiall was under strain and the market had soured on the story. And in 2021, Westlake bought Boral’s North American building products as Boral pulled back from the region.

Pulling this off takes two things that are surprisingly rare at scale: real balance-sheet capacity and the restraint to not spend it just because you can. Plenty of public companies feel compelled to “do something” and end up paying peak-cycle prices. Westlake has made a habit of doing the opposite—waiting until sellers are motivated and the odds are tilted in its favor.

Operational Leanness

The Chao family’s low-profile style shows up in the way Westlake runs. Industry observers have long pointed out that Westlake tends to carry lower selling, general, and administrative costs than peers. No flashy HQ built to impress visitors. No executive lifestyle becoming a distraction. The culture points back to the same place, again and again: operate tightly, control costs, keep the assets productive.

Vertical Integration as Moat

Vertical integration at Westlake isn’t just about saving a few points of margin. It’s about control.

When supply chains seize up—whether from the 2021 Texas freeze or broader global logistics breakdowns—the integrated players are the ones who can keep material moving. If you make your own key inputs, you’re less exposed to shortages, price spikes, and the scramble to secure allocation. In a world where disruptions are no longer “once a decade” events, that kind of supply security becomes a competitive advantage you can feel in real time.

Founder Mode in Public Markets

Westlake is public, but it isn’t run like a typical public company. With 72.3% of common stock controlled by the Chao family through TTWF LP, it qualifies as a “controlled company” under New York Stock Exchange rules.

The practical effect is simple: Westlake can think in decades, not quarters. When Albert Chao pushed ahead with the Axiall acquisition despite early skepticism from the market, he didn’t have to manage the usual short-term threats—an activist campaign, a boardroom revolt, a strategy reversal to appease a noisy shareholder base. The controlling ownership structure lets the company keep making long-horizon bets, in the same spirit that shaped T.T. Chao’s multi-decade buildout of petrochemicals across Asia.

VIII. Competitive Analysis: Powers and Frameworks

Porter's Five Forces

Supplier Power: LOW

Westlake has spent decades pushing upstream so it doesn’t have to depend on anyone else for the basics. It operates its own ethylene crackers in Louisiana and Kentucky, turning ethane from American natural gas production into the ethylene that feeds the rest of the system. That means less time negotiating for allocation and pricing—and more time running the plants.

Buyer Power: MEDIUM

Customers like Home Depot and Lowe’s are massive, sophisticated buyers, and they know exactly what leverage scale gives them. But Westlake sells into categories where “good enough” isn’t good enough—you need consistent quality, steady supply, and the ability to deliver at national scale. In PVC pipe especially, the supplier base is concentrated, which limits how easily buyers can swap in alternatives.

Threat of New Entrants: VERY LOW

To compete head-on with Westlake at the core of its business, you’d have to build an ethylene cracker. That’s a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar project before you even get to the harder part: permitting, safety systems, operational know-how, and reliability at scale. This is an industry where experience compounds and mistakes are expensive. The barriers are enormous.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH (Long-term concern)

This is the question that hangs over the entire plastics ecosystem: what happens if the world moves away from virgin PVC and polyethylene? In the near term, substitutes are limited—many applications still need performance, durability, and cost that alternatives struggle to match. But the direction of travel is clear: regulation is tightening, and customer expectations are shifting. Westlake’s move into epoxy through the Hexion acquisition gives it a foothold in materials tied to “sustainability” end markets, even as scrutiny on traditional plastics increases.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Commodity petrochemicals are a knife fight. Supply comes on, demand softens, and pricing moves fast. Polyethylene in particular is brutally cyclical. Westlake doesn’t escape that reality—but it doesn’t have to play it like everyone else. Its integration and U.S. feedstock advantage support a lower cost position, which can be the difference between struggling through downturns and using them to build even more share.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

Cornered Resource: Access to North American Ethane

This is Westlake’s foundational edge: cheap ethane from U.S. shale. Ethane is the key feedstock for making ethylene, and North America has it in abundance at costs many global competitors can’t touch.

That gap matters. European and Asian producers often rely on naphtha, an oil-based feedstock that’s typically more expensive. Some, like INEOS, have gone so far as to invest in specialized ships just to haul American ethane across oceans. Westlake doesn’t need ships. Its Gulf Coast footprint sits right on top of the resource.

Scale Economies

Westlake’s scale shows up in the unglamorous but decisive places: fixed costs, purchasing, logistics, and plant utilization. As the largest LDPE producer in the U.S. and one of North America’s leading PVC producers, it can spread overhead across huge volumes—and then compound that advantage as it integrates further downstream.

Process Power

There’s a reason Westlake keeps winning the same way. The Chao family built an organization that knows how to buy complicated, often distressed industrial assets—and then make them work. Axiall is the proof point: a difficult integration, promised synergies, and the cost takeout delivered. Doing that once is hard. Doing it repeatedly, across cycles, becomes a kind of institutional capability that’s difficult for competitors to copy.

IX. Bear Case vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

ESG and Plastics

The biggest long-term overhang on Westlake is the growing political and social backlash against plastics. PVC, in particular, draws scrutiny because it’s chlorine-based and difficult to deal with cleanly at end of life. If regulators move from “encouraging” change to mandating it—tight restrictions on certain applications, strict recycled-content rules, or tougher permitting—Westlake’s core markets could face real disruption.

Environmental Liabilities

Westlake also carries the kind of environmental risk that comes with operating large chemical sites for decades.

In 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced findings from a long-term air monitoring study around Westlake’s Calvert City, Kentucky operations. The EPA determined emissions of ethylene dichloride were driving elevated cancer risk, and said Westlake’s Calvert City operations were the main source of ethylene dichloride emissions in the area.

EPA documents also stated that 96 percent of reported EDC emissions in Calvert City came from the Westlake facility and that, based on 2020 data, the facility was the single-largest source of EDC air emissions in the United States.

Separately, in 2022, five Westlake subsidiaries agreed to make upgrades and perform compliance measures estimated to cost $110 million to resolve allegations of Clean Air Act violations at facilities in Louisiana and Kentucky, and the companies paid a $1 million civil penalty.

Taken together, these issues create both near-term risk—compliance costs, penalties, potential litigation—and long-term risk in the form of tighter operating constraints and reputational pressure.

Housing Crash

Westlake has intentionally become more of a housing and construction play. That cuts both ways. If rates stay high and new construction rolls over, the Housing and Infrastructure Products segment will feel it. The company has effectively bet that the U.S. housing shortage is a stronger force than the normal cycle—but the cycle can still hurt in the meantime.

Commodity Price Volatility

Even with all its integration, Westlake can’t escape the reality that a large part of the business is still commodity chemicals. The PEM segment moves with global supply and demand, and pricing is ultimately set by forces management can’t control.

The Bull Case

Infrastructure Investment

If you want a clean, multi-year demand driver for Westlake, start with water infrastructure. The U.S. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act included billions of dollars aimed at replacing lead water pipes with alternatives like PVC. Westlake also recently introduced a molecular oriented PVC (PVCO) pipe product, which it says has a lower manufacturing carbon footprint than other water main materials. If lead-pipe replacement becomes a sustained national priority, it could translate into years of steady pipe demand.

Housing Shortage

The structural case for Westlake’s housing bet is simple: the U.S. is short several million homes. Rates can delay projects, but they don’t eliminate the underlying need. When the build cycle eventually normalizes, those homes still require the same basic inputs—pipe, siding, trim, roofing, windows—many of which now sit inside Westlake’s portfolio.

Wind Energy and Composites

The Hexion epoxy acquisition gives Westlake a lever tied to the renewable buildout. As turbines get larger, blades get longer—and composites become even more critical. Westlake Epoxy manufactures and develops specialty resins, coatings, and composites for end uses like wind turbine blades and lightweight automotive structural components, which are both positioned as high-growth and sustainability-oriented markets.

Feedstock Advantage Endures

Westlake’s cost advantage still starts with American ethane. In 2023, U.S. exports of ethane and ethane-based petrochemicals reached an all-time high of 21.6 million metric tons, driven by growth in domestic ethane production. As long as U.S. shale continues producing abundant natural gas liquids, Westlake’s core “cornered resource” advantage—cheap, available ethane—remains intact.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

For investors following Westlake, two KPIs matter more than almost anything else:

-

EBITDA margin by segment - This is the simplest read on whether Westlake is executing: staying efficient in PEM while building steadier, higher-quality earnings in HIP. When the segments diverge, it tells you where the story is strengthening—or where it’s cracking.

-

HIP segment volume growth - HIP is the strategic bet. Watching volumes, not just revenue, helps separate real demand from price swings. If volumes hold up or grow through the cycle, the downstream shift is doing what it was supposed to do.

X. Conclusion: The Berkshire of Basic Materials?

Calling Westlake “the Berkshire Hathaway of basic materials” isn’t perfect, but it’s a useful lens. Like Berkshire, Westlake has been built with patient capital and a long time horizon. It has tended to buy when others are forced to sell. It has kept its balance sheet strong enough to act in down cycles. And it has spent decades proving that “boring” industries can produce extraordinary outcomes—if you’re disciplined about price, operations, and staying power.

At the center of the story is Ting Tsung “T.T.” Chao (1921–2008), born in Suzhou, China, who became a pioneering leader in petrochemicals and plastics across China, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, North America, and beyond. Westlake was his American bet—a wager that distressed assets, run well and integrated intelligently, could become an enduring industrial franchise. His sons, James and Albert—now Senior Chairman and Executive Chairman, respectively—took that foundation and scaled it into a Fortune 500 giant.

None of this comes without risk. Environmental scrutiny is real, especially for legacy chemical sites. Housing can turn fast, and Westlake has intentionally tied more of its future to construction and renovation cycles. And the long-term debate over plastics—what should be made, how it should be recycled, and what regulation will demand—will shape the industry’s economics for years.

But the opportunity set is just as clear. Infrastructure spending supports demand for pipe and essential materials. The U.S. housing shortage continues to pull on building products over time, even when rates disrupt the cycle. And the renewable energy transition is creating new markets for performance materials like epoxy in applications such as wind turbine blades.

For nearly forty years, the Chao family compounded an edge by doing three things exceptionally well: navigating commodity cycles without overextending, executing complex acquisitions when assets were mispriced, and squeezing lasting value out of heavy industrial operations that others had written off. Whether Westlake can keep that cadence under its first non-family CEO, Jean-Marc Gilson, is the next chapter.

What’s already clear is the footprint Westlake has left on modern life. The pipes in your walls. The siding on the house down the street. The materials inside the packaging you throw away and the infrastructure you never think about. Westlake built a quiet empire by doing the unglamorous work—turning molecules into materials, and materials into the physical world around us.

Sources and Further Reading: - The Prize by Daniel Yergin (for context on the oil and petrochemical industry) - Westlake Corporation SEC filings and investor presentations - American Chemistry Council reports on the shale gas revolution - EPA documentation on Calvert City air quality monitoring

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music