Willdan Group Inc.: The Unlikely Journey from California Engineering Firm to Energy Efficiency Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

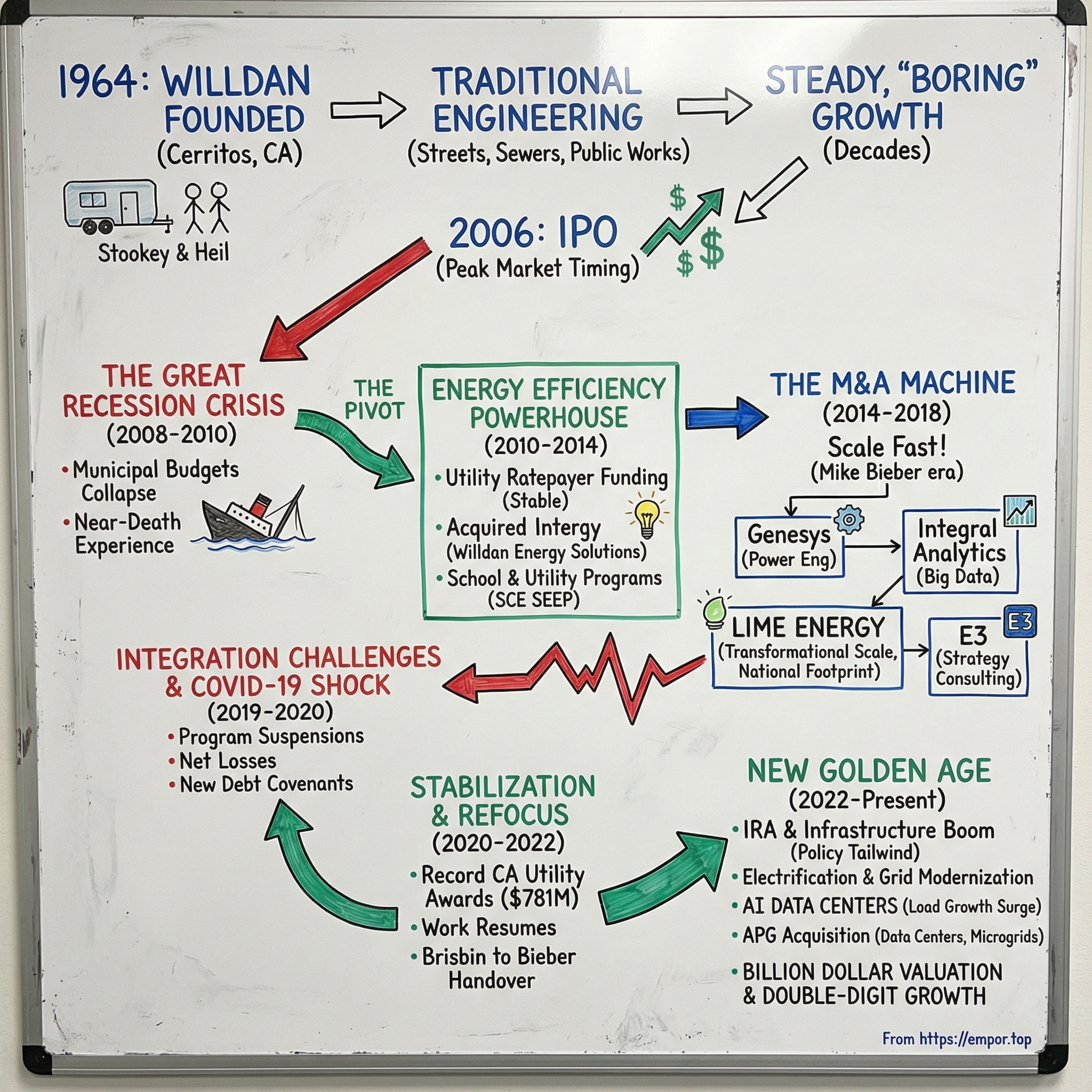

Picture Southern California in 1964. Two engineers, William Stookey and Dan Heil, are trying to get a fledgling consultancy off the ground from a trailer in Dairy Valley, a small community that would later become the City of Cerritos. They mash their names together—Willdan—and start doing the kind of work that keeps cities running: the uncelebrated engineering behind streets, sewers, and public works.

Fast forward six decades. The trailer is long gone, but the company is very much alive. As of December 27, 2024, Willdan had 1,761 employees and annual contract revenue of more than $565 million. By August 2025, its market capitalization sat at roughly $1.22 billion. Not bad for a company most people couldn’t pick out of a lineup.

What makes Willdan worth an episode isn’t that it quietly compounded for sixty years. It didn’t. This is a survival story. A reinvention story. A case study in how a regional municipal engineering firm—about as “steady and boring” as it gets—managed to transform itself into a national player in energy efficiency and grid modernization.

Because Willdan nearly died in the Great Recession. When California cities slammed the brakes on spending, Willdan’s bread-and-butter work collapsed with them. The company responded by betting its future on a pivot into energy efficiency—an industry that barely existed when those founders were drafting plans in that Cerritos trailer. Then came the growth sprint: an M&A spree that, at times, was downright brilliant—and at other times created problems that threatened to undo the whole transformation.

Today, Willdan sits at the crossroads of some of the biggest forces reshaping American infrastructure: the push to decarbonize, the electrification of everything, and a surge in electricity demand—now supercharged by AI data centers. As grids strain and power gets more expensive, “use less” and “use smarter” stop being slogans and start becoming necessities. Willdan sells the picks and shovels for that world: consulting and technical services focused on energy efficiency, grid management, and sustainability.

This is the story of how an unglamorous company doing unglamorous work made itself indispensable to America’s energy future—and what that journey teaches about policy-driven markets, the art of corporate reinvention, and the very real limits of M&A-fueled growth.

II. Founding & Early Years: Engineering Infrastructure for Growing California (1964–2000s)

1964 was a pretty perfect year to start a company that sold “the stuff cities need.” California was in the middle of a historic growth spurt. People were pouring in. Subdivisions were popping up across Southern California. And every new community needed the basics—roads, water, sewers, building departments that could keep up, and engineers who could make sure everything actually worked.

That’s the world William Stookey and Dan Heil stepped into when they founded Willdan. Their model was simple, and at the time, unusually focused: provide outsourced engineering services to municipalities, especially the newly urbanizing cities that were growing faster than their budgets and staffing could handle.

The pitch was essentially: you don’t need a full in-house engineering department. You need the function of one. Willdan could be the outsourced city engineer—reviewing building plans, running inspections, designing infrastructure, and handling the technical work that keeps a city from slowly breaking down.

From the beginning, the company aimed squarely at public agencies with practical, mission-critical services like building and safety and civil planning. Over time, that client base broadened to include federal and local governments, school districts, public utilities, and some private industry work. But the core stayed consistent: small to mid-sized clients—the ones too small to justify big internal teams, and often too small to attract the largest competitors.

For decades, that model just worked. Willdan built its reputation the unsexy way: by being reliable, competent, and present when a city needed answers fast. The work wasn’t glamorous—no one’s writing breathless profiles about plan checks or sewer capacity calculations—but it was steady, recurring, and essential.

As the company matured, it expanded across the Southwest and widened its service menu: civil and structural engineering, disaster recovery, and districting services. One notable chapter came out of California’s hard-earned earthquake lessons, including work designing seismic retrofits for California Department of Transportation bridges after earthquake-related collapses.

Willdan’s growth was methodical. It added geotechnical engineering, transportation planning, and even financial consulting for public agencies. By the early 2000s, it had grown well beyond that Cerritos trailer into a real regional player serving municipalities across California and neighboring states.

Then came the decision that quietly set up the next act: going public.

On November 21, 2006, Willdan Group announced an initial public offering of 2.9 million shares at $10.00 per share. Two million shares were issued by the company, and 900,000 shares were sold by a selling stockholder. Willdan planned to use net proceeds of about $16.9 million for working capital and general corporate purposes, including possible acquisitions.

In hindsight, the timing was both exquisite and awful. Exquisite because they raised capital near the market’s peak. Awful because the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression was already gathering speed.

The company had been growing steadily: $58 million of revenue in 2004 became $67 million in 2005, and through the first nine months of 2006 it was on track for about $80 million—another year of similar growth. At the IPO price, Willdan was valued at roughly 16 times 2006 earnings, a reasonable multiple for a consistently growing professional services firm.

But even then, the vulnerability was obvious. As one analyst warned at the time, the big risk was concentration: if California took a serious downturn, Willdan would feel it first—and hardest.

That risk was about to show up in spectacular fashion.

III. The Great Recession Crisis: Near-Death Experience (2008–2010)

The financial crisis didn’t just rattle California. It broke it. Home prices fell hard from their mid-2006 highs into 2009. The stock market cratered. Trillions of dollars in household wealth evaporated.

And for Willdan, that macro pain quickly became a very specific problem: the people who paid its bills were cities. California cities.

When municipal budgets collapsed, “nice-to-have” projects disappeared overnight. New construction stalled. Public works departments froze spending, then started cutting staff. The same cities that had relied on Willdan to design infrastructure and keep projects moving were suddenly fighting just to keep the lights on.

This was the downside of the concentration risk the company had carried for decades. The very focus that made Willdan efficient—California, public agencies, core municipal services—now put the whole company in the blast radius. Revenue that had been steadily rising began to fall. Margins tightened. Debt covenants started to matter in the most frightening way: not as a line item, but as a clock.

Willdan faced the classic crisis question: do you slash costs and wait it out, or do you change the company while you’re still standing?

The leadership team chose change. CEO Thomas Brisbin, who joined in April 2007—just after the IPO—steered the company toward a new engine of growth and stability. That decision would end up defining his tenure: over time, revenue grew more than sixfold, but it started with one uncomfortable realization in 2008. The old model, on its own, could no longer be trusted to survive the next downturn.

The opening came from an unexpected place. Even as budgets were getting shredded, California was pushing forward on energy policy. Utilities were required to spend ratepayer funds on energy efficiency programs—money earmarked to help customers use less energy. In a recession, that funding stream didn’t behave like city tax revenues. It had rules, regulatory oversight, and a mandate.

But it also needed operators. Someone had to design and run the programs.

In 2008, Willdan bought Intergy Corporation and later renamed it Willdan Energy Solutions, giving the company a foothold in energy efficiency and utility program management.

This was the bet: use Willdan’s credibility with public agencies and its engineering discipline as a bridge into a different kind of infrastructure work—one funded by utility ratepayers instead of municipal budgets, and one with the potential to be more resilient when the economy turned.

It wasn’t a gentle evolution. Willdan’s people knew plan checks, inspections, and sewer systems. Now they were stepping into a world of incentives, program rules, and utility regulators—and trying to learn it fast enough to keep the company alive.

IV. The Pivot: Becoming an Energy Efficiency Company (2010–2014)

To understand why Willdan’s pivot into energy efficiency worked, you first have to understand what “energy efficiency” actually means as a business. This wasn’t a charity effort or a nice sustainability add-on. In California, it was a regulated market with real budgets and real accountability—and it existed because the state essentially willed it into existence.

Investor-owned utilities in California run energy efficiency programs funded by ratepayers, under the watch of the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). The CPUC works with the utilities, other portfolio administrators, and vendors to design programs and measures meant to push the market toward more efficient technologies—using that ratepayer funding to do it.

The model is straightforward. Regulators require utilities to help customers use less electricity and gas. But utilities aren’t built to execute that work themselves. They don’t have teams that can show up at a school, audit a campus, recommend equipment upgrades, manage contractors, and then document the savings in a way regulators will accept. So they hire specialists—third-party implementers—to run the programs.

California was the perfect place for this to become a real industry. The state had already spent decades treating efficiency like an energy resource in its own right. Over more than 50 years, California kept per capita energy use essentially flat while the rest of the country rose by about a third. That didn’t happen by accident. It came from policy, incentives, and program design—exactly the kind of environment where an execution-oriented services firm could build a durable business.

For Willdan, the appeal was obvious. First, the funding source—ratepayer charges—was more stable than city budgets, and far less exposed to the kind of fiscal cliff that nearly wiped the company out in the recession. Second, Willdan already knew how to sell to public-sector institutions and how to deliver technical work with compliance requirements attached. Third, energy efficiency programs demanded what Willdan had always been good at: project management, engineering judgment, and getting complicated work done on time.

One of the early proving grounds was education. Willdan Energy Solutions contracted with Southern California Edison (SCE) to help reduce energy use in public and private schools. SCE’s Schools Energy Efficiency Program (SEEP), with an initial budget of $4 million, targeted pre-kindergarten through secondary schools, private colleges and universities, and vocational schools—funding high-efficiency lighting retrofits and other energy-saving upgrades.

These programs became Willdan’s on-the-job training for an entirely new kind of infrastructure work. The company learned how to run energy audits, manage retrofit installations, navigate utility incentive paperwork, and—most importantly—deliver savings that could be measured and verified. And in this market, each successful program didn’t just generate revenue. It built credibility. It made the next bid easier to win.

By 2014, the pivot had real momentum. Willdan had proven it could compete in energy efficiency—but it also realized something else: organic growth wasn’t going to reshape the company fast enough. If Willdan wanted national scale, it needed an accelerant.

That’s where corporate development entered the story. In December 2014, Michael A. Bieber joined Willdan as Senior Vice President of Corporate Development. He came from Tetra Tech, where he had spent more than 18 years in leadership roles.

“A key aspect of our growth strategy includes the pursuit of selective tuck-in acquisitions that can expand our geographic footprint, broaden our service offerings and improve our competitive position. Having completed more than 50 acquisitions over the past seven years, all in the E&C industry, Mike’s knowledge and accomplishments across the technical and consulting services landscape are virtually unmatched.”

Bieber’s arrival was a tell. Willdan wasn’t just pivoting anymore. It was getting ready to buy its way to scale—and to become, for better and worse, an acquisition machine.

V. The M&A Machine: Rolling Up the Energy Services Industry (2014–2018)

Mike Bieber arrived at Willdan with a playbook honed at Tetra Tech, one of the industry’s most aggressive consolidators. From March 2007 to December 2014, he ran Tetra Tech’s mergers and acquisitions and investor relations functions, overseeing more than 50 acquisitions.

At Willdan, his mandate was simple: don’t just pivot into energy—scale it, fast. The energy efficiency services world was a patchwork of smaller firms, each with a handful of utility relationships, a regional footprint, and a niche they defended fiercely. That fragmentation wasn’t a problem. It was an invitation. If Willdan could assemble the right pieces, it could go from “California energy contractor” to “national utility partner” in a few years instead of a few decades.

In 2015, Willdan acquired 360 Energy Engineers and Abacus Resource Management, adding capabilities in Energy Service Company work and Energy Savings Performance Contract services.

In 2016, Willdan acquired New York City–based Genesys Engineering, P.C., adding power engineering services to the mix—an early bet on where the grid was heading, toward distributed generation and microgrids.

The Genesys deal mattered for another reason: geography. It gave Willdan a real foothold in New York, the second-largest energy market in the country after California. And it gave Willdan technical depth in power engineering that would only become more valuable as electrification accelerated.

“Since joining Willdan in 2014, Mike has spearheaded the M&A activity that has expanded our energy efficiency services capabilities, and has significantly contributed to our strong growth in revenue, earnings and cash flow.”

In July 2017, Willdan acquired Integral Analytics, Inc. (IA), a big data analytics firm whose software helps investor-owned utilities and smart city managers handle the headaches of a modernizing grid—more rooftop solar, more electric vehicles, more distributed complexity, and more need for smarter planning.

Then came the deal that defined this whole era.

On October 3, 2018, Willdan Group and Lime Energy announced that Willdan had signed an agreement and plan of merger to acquire all outstanding shares of Lime Energy. The total purchase price was $120 million in cash, subject to customary holdbacks and adjustments.

Willdan pegged the price at roughly ten times its estimate of Lime Energy’s anticipated 2018 Adjusted EBITDA, and expected Lime Energy to generate about $145 million of revenue in 2018. Lime Energy designed and implemented direct install energy efficiency programs for utilities—boots-on-the-ground work aimed at commercial customers, where energy savings come from upgrading existing equipment and installing new, more efficient systems.

Lime Energy—founded in 1997 and formerly known as Electric City Corp.—brought more than just revenue. The company had delivered energy efficiency programs for 10 of the 25 largest electric utilities and five of the 10 largest municipal utilities in the U.S. And when the transaction closed on November 9, 2018, it expanded Willdan’s geographic footprint into the southeastern and mid-Atlantic U.S. while diversifying its utility customer base.

This was the transformational moment. Lime didn’t just add another service line. It gave Willdan national scale—almost overnight. But it also raised the stakes. Willdan had never integrated a business this large, and it needed real financing firepower to pull it off.

The new credit facility provided for up to a $90 million delayed draw senior secured term loan, subject to certain conditions (including completion of the Lime Energy acquisition), and a $30 million senior secured revolving credit facility, each maturing on October 1, 2023.

And Willdan didn’t stop there—even though Lime alone would have been enough work for most teams.

The acquisition of The Weidt Group in March 2019 added energy engineering for new construction and a strong presence in the Upper Midwest. In July 2019, Willdan entered a $200 million expanded credit facility to fund future acquisitions, and also announced its acquisition of Onsite Energy Corporation, adding industrial-sector clients to its energy efficiency services.

Then, on October 30, 2019, Willdan announced that it had acquired Energy and Environmental Economics, Inc. (E3), in a stock purchase that closed on October 28. E3 had more than 70 employees across offices in San Francisco, Boston, and New York.

E3 wasn’t a field-operations business. It was a high-status, data-driven energy analysis and strategy consulting firm—known for advising utilities and regulators. Buying E3 signaled something important: Willdan didn’t just want to run programs. It wanted to help shape them.

By late 2019, the transformation was hard to argue with. Willdan had gone from roughly $80 million of revenue around the time of its IPO to nearly $400 million, with offices across the country and relationships with major utilities. The pivot into energy efficiency had worked—spectacularly.

But speed cuts both ways. An acquisition spree can build a company fast, and it can also hide problems until they’re too big to ignore. Willdan’s new risks—balance sheet strain, integration complexity, and the challenge of stitching together very different businesses—were about to become very real.

VI. Navigating Integration Challenges (2019–2020)

The acquisition sprint of 2018 and 2019 left Willdan with the classic consolidator’s hangover: integration. It’s one thing to buy capabilities and customer relationships on paper. It’s another to stitch together different cultures, systems, and operating rhythms—without breaking what you just paid for. Move too fast, or integrate too loosely, and the deals that were supposed to create value can quietly start destroying it.

And the challenge wasn’t theoretical. Willdan was now running a growing portfolio of utility programs across multiple states, while trying to standardize processes and bring newly acquired teams into a single operating model. The question was simple: could the company digest everything it had just eaten?

Then came a shock no integration plan had a section for: COVID-19.

“This quarter we witnessed both the initial slowdown related to the unprecedented impact that Covid-19 has had on the economy, as well as record cash flows from operations,” said Tom Brisbin, Willdan’s Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. “We experienced a negative impact on our small business Direct Install programs because, under government restrictions relating to Covid-19, these programs were ordered to suspend temporarily.”

The hit showed up fast. For the first quarter of 2020, Willdan reported consolidated contract revenue of $106.0 million and a net loss of $8.2 million, compared with $91.8 million of revenue and a net loss of $0.4 million in the first quarter of 2019.

The pain was concentrated in the part of the business that simply couldn’t be “Zoomed.” Direct install programs depend on technicians entering commercial buildings to swap equipment and complete upgrades—exactly the kind of in-person work government restrictions shut down. Programs were suspended across the country, and uncertainty became the day-to-day operating environment.

Willdan responded the way a company with fresh debt and recent acquisition baggage has to respond: protect the balance sheet. On May 6, 2020, it amended its credit agreement to gain more flexibility under its debt covenants. The amendment temporarily changed the interest rate for borrowings under the company’s credit facilities and put restrictions in place—no share repurchases, limits on certain acquisitions, and limits on borrowings under the delayed draw facility. Along with availability under its revolving credit facility, it created a liquidity cushion against surprises.

Cost controls tightened. Cash preservation became the priority. And the surprising part was what didn’t happen: despite the suspensions, contracts weren’t being terminated and budgets weren’t being pulled. The work wasn’t disappearing—it was stacking up.

By year-end, Willdan said it was down 3% on net revenue from 2019 and about 12% below budget. But the bigger takeaway was this: no contracts had been canceled and no budgets reduced. In every case, the work was delayed, not deleted.

Even more important, Willdan used the chaos to land new business. In 2020, it won a record amount of new work. After two years of negotiation, the California investor-owned utilities awarded Willdan six energy efficiency contracts totaling $781 million—about 88% of what the company bid on.

“I’m excited to announce that Willdan has signed a total of $781 million in new California Investor Owned Utility Contracts this year. These six contracts are three to five years in duration, and on a weighted average basis, represent approximately $150 million per year in incremental contract revenue on average over the next three to five years if we successfully execute the work.”

In the middle of a pandemic—when competitors were pulling back—Willdan was loading the pipeline. Those California awards weren’t just a win; they were a signal that Willdan’s post-pivot identity had become real and bankable. And they set the company up to come out of 2020 with something rare: not just survival, but momentum.

VII. Stabilization & Strategic Refocus (2020–2022)

As COVID restrictions eased into 2021, the work that had been frozen in place started moving again. Willdan’s suspended programs restarted, and the company’s teams went back to doing the most basic thing its energy business depends on: showing up in person.

“On June 28th we restarted the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power commercial direct install program, which was our largest contract and the last program suspended due to Covid-19. In late July, the California Public Utility Commission approved our three contracts with Southern California Edison. We now expect all seven of our new California Investor-Owned Utility contracts to ramp over the next year.”

It wasn’t just a restart; it was a reset. Willdan came out of the pandemic in better shape than many of its peers. The big California awards were beginning to ramp. The integration work from the acquisition spree was moving from chaos to cadence. And the policy backdrop—the thing that had made the pivot possible in the first place—was only getting more supportive.

“We had a strong fourth quarter, well ahead of our internal plan, which provides us a nice ramp into the year,” said Tom Brisbin. “All of our areas of business are currently improving, we have record levels of funded backlog, and we expect to achieve significant growth in revenue and earnings in 2022.”

But stabilization wasn’t only operational. It also came with a leadership handoff. After 16 years steering Willdan through its most defining era—near-death in the recession, the pivot into energy, then the high-wire act of scaling through acquisitions—Brisbin began transitioning the company to its next chapter.

On December 8, 2023, Tom Brisbin notified the Board of Directors of his intention to retire from his position as CEO effective December 29, 2023. Tom will retain his role as Chairman of the Board and will act as the company's part-time consultant to ensure a smooth transition. Willdan's President, Mike Bieber, will succeed Tom as CEO and will become a Board Member effective December 30, 2023.

“I’d like to commend Tom for his leadership and commitment to our company over the past 16 years,” Mike Bieber commented. “I’m proud of what we’ve built at Willdan, and even more excited about where we’re headed. We are building a leading company that transitions communities to clean energy and a sustainable future.”

Brisbin’s tenure was the kind most CEOs never get—because most never face the kind of stakes he did. He walked in right after the IPO, watched the core business buckle in the Great Recession, and then made the bet that reinvented the company. By the time he handed over the keys, Willdan wasn’t a regional municipal engineering firm anymore. It was a national energy services platform with a much bigger ceiling.

And now Bieber—the dealmaker who helped assemble that platform—was in the top seat, inheriting a company about to collide with the next wave of policy-driven demand.

VIII. The IRA and Infrastructure Boom: A New Golden Age? (2022–Present)

In August 2022, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act into law—the most significant climate legislation in U.S. history. It wasn’t a single program so much as a giant toolkit: grants, loans, tax credits, and incentives designed to accelerate clean power, cleaner vehicles, more efficient buildings, and domestic clean manufacturing, while also pushing investment toward environmental justice.

In total, the IRA aimed nearly $400 billion of federal support at clean energy, with a stated goal of cutting U.S. carbon emissions by roughly 40% by 2030.

For Willdan, the timing was almost uncanny. The company had spent the prior 15 years building the exact muscle the IRA now rewarded: energy efficiency, building electrification, grid modernization, and renewable integration. Willdan didn’t need to invent a new business to chase the wave. It just needed to catch it.

California alone underscored how big the moment was. The prior energy efficiency proceeding established energy efficiency portfolios for 2024–2027 totaling $4.3 billion, with another $4.6 billion forecasted for 2028–2031—massive, multi-year commitments to the work Willdan already knew how to deliver.

But the real shift was that California was no longer the whole story. The IRA pushed money outward—into states, utilities, cities, school districts, and commercial markets across the country. And thanks to years of acquisitions, Willdan had already built a national footprint to meet that demand where it landed.

This surge also lined up with a bigger set of trends reshaping the grid. Electrification was becoming the core currency of the energy transition, with electricity’s share of final energy consumption projected to exceed 50% by 2050. That kind of future doesn’t work on today’s infrastructure. It requires modernization, resiliency, and better planning—exactly the terrain where firms like Willdan get called in.

At the same time, energy efficiency was re-emerging as the “first fuel”—the fastest, cheapest way to manage load growth. That’s a direct tailwind for Willdan’s bread-and-butter programs.

And then came the new accelerant: AI data centers. As artificial intelligence scaled, so did the electricity required to power and cool the compute. Suddenly, “load growth” wasn’t a slow-moving forecast. It was an urgent problem, and it showed up as a demand signal for the same work Willdan had been building toward: efficiency, electrical engineering, and grid upgrades.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration projected sustained growth in electricity consumption, marking the first three-year growth streak in nearly two decades.

Willdan didn’t sit still. On March 3, 2025, the company acquired Alternative Power Generation, Inc. (APG), an electrical engineering and construction management firm, in a stock purchase. APG added expertise in data center substation design and construction management, microgrids, EV charging stations, and renewable energy projects for commercial customers. In 2024, APG generated approximately $37 million in revenue.

“APG's deep electrical engineering expertise and commercial relationships will bolster our existing capabilities,” said Mike Bieber, Willdan’s CEO. “Together, we are expanding our solutions to data centers and other commercial electric loads, enhancing our ability to serve the evolving energy landscape.”

Contract wins followed. Alameda County, California, selected Willdan for a $97 million contract to design and implement energy and infrastructure upgrades.

The energy savings performance contract covered electrification of major HVAC systems, solar PV generation, EV charging stations, and other efficiency, deferred maintenance, and decarbonization upgrades across 24 sites—reducing annual carbon emissions by approximately 1.7 metric tons of CO2e. Willdan also provided consulting to help the County identify outside funding sources that could further reduce out-of-pocket costs.

The financials started to reflect the momentum. For fiscal year 2024, Willdan reported contract revenue of $565.8 million, up 10.9%, net revenue of $296.3 million, up 9.9%, net income of $22.6 million (up from $10.9 million), and Adjusted EBITDA of $56.8 million, up 24.2%.

By the quarter ending October 3, 2025, Willdan reported revenue of $182.01 million, up 15.01%. That brought trailing twelve-month revenue to $651.93 million, up 12.90% year over year.

In Q3 2025, the company reported EPS of $1.21, well ahead of estimates, and revenue of $94.97 million. Contract revenue increased 15% year over year to $182 million, net revenue grew 26% to $95 million, organic growth came in at 20%, and net income rose 87% to $13.7 million.

With results like that, the guidance moved up. Willdan repeatedly raised its targets for fiscal year 2025, and now expected net revenue between $360 million and $365 million, with adjusted diluted EPS between $4.10 and $4.20 per share.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive: How Willdan Actually Makes Money

Willdan Group, together with its subsidiaries, sells professional, technical, and consulting services across the United States. But despite all the talk about electrification and grid modernization, the company is still, at its core, a services business with a simple structure: two segments—Energy, and Engineering and Consulting.

Let’s unpack each one.

The Energy Segment

This is where the growth is—and where the modern Willdan story really lives. The Energy segment delivers energy solutions for businesses, utilities, state agencies, municipalities, and nonprofits. In practice, that can look like almost anything that helps reduce energy use or manage the grid: audits and surveys, program design, planning, demand reduction, benchmarking, design engineering, construction management, performance contracting, installation, measurement and verification, and increasingly, software and data analytics for long-term planning.

Here’s the clean way to think about the model. Utilities have regulatory mandates to help customers use less energy. They often don’t have the people, the tools, or the operational muscle to execute those programs at scale. So they outsource the work to specialists like Willdan—who design the program, sign up customers, do the technical audits, manage the installation work, and then document the results in a way regulators will accept.

Willdan says that over its history it has implemented more than 100 utility programs and served about 230,000 customers nationwide across categories like commercial businesses, healthcare, hospitality, data centers, warehouses, grocery, and education.

The revenue streams are exactly what you’d expect for this kind of work: program management fees, incentives tied to hitting energy savings targets, and compliance and documentation services. Most contracts run for multiple years, which helps with visibility. And once a utility has an implementer embedded in its processes—systems, reporting, field operations, regulatory documentation—switching isn’t painless. That stickiness matters.

One example: Willdan was selected to design and implement SDG&E’s Small Commercial Energy Efficiency Program. It’s a three-year, $42 million program serving small businesses with peak demand under 20 kilowatts, combining energy efficiency and demand response. Willdan has been providing energy efficiency and resource procurement programs in Southern California since 2008, so it’s not a cold-start relationship.

The Engineering and Consulting Segment

This is the original Willdan—the outsourced city engineer model that started back in 1964. The Engineering and Consulting segment provides services like building and safety, city engineering, code enforcement, plan review and inspection, disaster recovery, geotechnical and earthquake engineering, planning and surveying, contract staff support, program and construction management, structural engineering, transportation and traffic engineering, and water resources.

It’s less flashy than Energy, but it tends to be steady. Client retention is strong because cities and public agencies don’t switch providers lightly—especially for work tied to permitting, inspections, compliance, and ongoing public works support. This segment also includes district administration, financial consulting, and federal compliance services, serving a wide range of public-sector clients, including cities, counties, water districts, school districts, universities, state and federal agencies, utilities, commercial and industrial firms, and tribal governments.

And yes, there’s cross-selling. A city that uses Willdan for engineering can also hire Willdan to upgrade municipal buildings for efficiency. A utility that hires Willdan for programs can also pull it into related engineering support as grid and infrastructure needs expand.

Revenue Visibility and the Backlog

One of Willdan’s quieter strengths is visibility. Multi-year contracts—especially utility programs—create a baseline of work you can actually plan around. Backlog, meaning contracted work not yet recognized as revenue, is the tell.

Willdan’s ability to keep winning large awards—like a $330 million, five-year agreement with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, alongside other major wins with the California Public Utilities Commission and National Grid—shows that, even as the market grows more competitive, it continues to land and hold meaningful relationships.

The Margin Challenge

But there’s a catch—and it’s the catch in almost every services business: margins are constrained by people. Willdan is labor-intensive, and historically it’s been a thin-margin operation. Operating margins were 7% in 2004 and 2005.

Scale and better execution can improve margins over time, but this will always be a company that needs engineers, project managers, and technical staff to deliver the work. There is operating leverage here, but it isn’t software-style leverage. The business can get better—it just can’t escape the physics of being built on labor.

X. Industry Dynamics & Competitive Landscape

Willdan operates in a crowded neighborhood—and that’s true whether you define the market as “energy efficiency program implementation” or the broader universe of infrastructure, engineering, and utility-facing consulting.

On the pure-play energy efficiency side, you’ll see names like CLEAResult and Franklin Energy show up again and again. Ameresco is another important competitor, especially in energy solutions and performance contracting. Then there’s a long list of adjacent specialists and consulting firms—Cadmus, Weston Solutions, TRC, ICF, NV5 Global, and others—who can compete for pieces of the same work depending on the contract.

And hovering above all of them are the giants: Tetra Tech, AECOM, Jacobs, Stantec, Black & Veatch. These firms offer massive breadth and can overlap with Willdan’s offerings whenever a utility or public agency wants a “one-stop shop” that combines engineering, planning, and program delivery.

What’s striking is how fragmented this landscape remains. That fragmentation isn’t an accident—it’s a feature of how the industry works:

Complexity and regulatory nuance: Every state has different energy policies. Every utility has its own program structures. And the regulators who oversee all of it have their own requirements and reporting standards. Winning is less about having the flashiest pitch deck and more about knowing the rules—and executing them without mistakes.

Relationship-driven sales: Yes, there are formal RFPs. But the real currency is trust. Track record matters. References matter. And once an implementer is embedded in a utility’s workflows—reporting, compliance, field operations—switching becomes painful.

Low capital requirements, high expertise requirements: You don’t need factories to start an energy services firm. But you do need people who understand engineering, policy, and program management—and those teams take years to build.

That said, “low capital” also means new entrants can show up. The sector keeps getting reshaped by new competitors, partnerships, and M&A as firms try to stitch together scale, geography, and specialized capabilities.

You can see the competitive overlap in real contracts. Southern California Edison has contracted with Willdan for its Commercial Energy Efficiency Program (CEEP), serving SCE’s commercial customers with monthly maximum demand greater than 20 kW across its service territory. Meanwhile, SCE’s Higher Education Efficiency Performance program is implemented by CLEAResult for California Community Colleges, the University of California system, and California State Universities.

Two different implementers, same utility, different slices of the market—proof that the opportunity is big enough to support multiple winners, as long as they can deliver reliably and navigate the complexity.

XI. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-Low

It doesn’t take a factory or a pile of capital to start an energy services firm. But it does take time—time to learn the regulatory maze, time to build delivery muscle, and time to earn trust with utilities that don’t like surprises. New entrants can absolutely show up. The hard part is scaling fast enough, and reliably enough, to win and keep the big programs.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low

In this business, the “suppliers” are people: engineers, project managers, field teams, and technical specialists. The labor market is competitive, and certain skill sets in energy efficiency and utility program delivery can be tight. But it’s not a single-source input. Willdan’s edge here is less about locking up talent and more about being a known destination in the niche, which helps recruiting and retention.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Medium-High

Utilities are large, sophisticated buyers. They run formal RFP processes, compare bidders aggressively, and push hard on pricing. They also have alternatives. The twist is what happens after the ink dries: once a program is live, switching is messy. Disrupting field operations, reporting systems, and regulatory documentation midstream is risky, so incumbents often gain leverage over time.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium

The cleanest substitute is a utility deciding to do more of this work in-house—but most don’t, because it requires specialized capabilities and constant execution. Another substitute is technological change: better software, more automation, maybe even AI-driven program design and customer targeting. And then there’s the biggest substitute of all in policy-driven markets: if rules or priorities change, funding can change with them.

Competitive Rivalry: Medium-High

This is a crowded arena with multiple competent players, and competition shows up most brutally during procurement. Price pressure is real. The way out is execution: hitting savings targets, managing programs cleanly, and avoiding compliance mistakes. In a market like this, “doing the job well” isn’t table stakes—it’s differentiation.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: Limited

Willdan is still selling human effort at scale. There are benefits to size—spreading overhead, building repeatable processes, and deploying teams across more programs—but it’s not a business where doubling revenue automatically transforms the cost structure.

Network Economics: Not Applicable

One utility hiring Willdan doesn’t inherently make Willdan more valuable to another utility in the way a true network does.

Counter-Positioning: Weak

Willdan benefited from being early and serious about the pivot while some traditional engineering firms stayed put. But the model itself isn’t forbidden knowledge. Large competitors can build or buy similar capabilities if they decide the market is worth it.

Switching Costs: Moderate-Strong

This is the heart of Willdan’s defensibility. Once it’s embedded in a utility program—processes, reporting, compliance routines, field operations—the idea of swapping implementers becomes a risk event. Nobody wants to be the one who broke a program that regulators are watching.

Branding: Weak

This is not a consumer brand game. Reputation matters, but it’s reputation with a small set of buyers who care about track record, references, and reliability—not name recognition.

Cornered Resource: Moderate

Long-term utility relationships, regulatory know-how, and experienced teams aren’t impossible to find—but they’re hard to assemble in one place. E3, with its credibility in analysis and regulatory work, strengthens this resource because it makes Willdan more than just an implementer; it makes it part of the conversation upstream.

Process Power: Moderate

There’s real institutional learning here: how to design programs that work, how to run implementations at scale, how to document savings in ways regulators will accept, and how to keep the machine running across multiple geographies. A determined competitor can replicate that, but it takes time—and time is usually the bottleneck.

Overall Assessment: Willdan’s advantage isn’t a towering moat. It’s the kind of defensibility that wins in regulated, relationship-heavy services markets: switching costs, trust, and accumulated know-how. It’s more “sticky incumbent” than “winner-take-all”—but in a growing market, that can still compound into something meaningful.

XII. The Bull Case vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

Multi-Decade Policy Tailwind: Climate goals aren’t going away. The IRA funds incentives and programs through the end of the decade, and state-level mandates keep getting tighter. Under a business-as-usual path, the U.S. was projected to cut greenhouse gas emissions by about a quarter to a third by 2030 versus 2005 levels. With the IRA, projections rise into the low-30s to mid-40s. Either way, hitting those targets takes exactly the kind of on-the-ground execution Willdan sells: energy efficiency programs, electrification, grid planning, and implementation.

New Growth Vectors: A few years ago, “AI data centers” weren’t a meaningful line item for most infrastructure consultants. Now they’re a major driver of load growth—and they pull demand behind them for substations, interconnection studies, efficiency, and grid upgrades. Add EV infrastructure and building electrification, and the addressable market expands well beyond traditional utility efficiency programs. The backdrop is simple: electricity demand is rising, and some projections point to roughly a 50% increase by 2050. Modernizing the grid stops being optional.

Established Market Position: Willdan enters this wave with a national footprint, embedded utility relationships, and a track record of delivering programs at scale. Its recent operating performance reflects that strength, including meaningful earnings growth and margin improvement—highlighted by a sharp year-over-year increase in earnings per share.

Management Has Learned from Mistakes: This company has been stress-tested—by the Great Recession, by aggressive M&A, and by the operational whiplash of COVID-era program suspensions. The upside of those scars is discipline. Surviving messy chapters can create a more resilient organization, especially in a business where execution and credibility are everything.

Undervalued Relative to Growth: If Willdan can keep producing double-digit organic growth while expanding margins, a bullish investor would argue the market still isn’t fully pricing in how big this policy-and-load-growth moment could be.

The Bear Case:

Policy Dependence: This business rides regulated budgets and public priorities. What government and regulators support, they can also revise. A change in administration, state budget pressure, or shifting regulatory emphasis could shrink program funding. Increased reliance on government-related work—and the scheduled end of certain tax deductions—could also weigh on earnings growth if the company can’t offset it elsewhere.

Labor-Intensive Model: Willdan sells expertise and execution. That means people. Hiring, retaining, and deploying specialized talent is expensive, and it naturally caps margin expansion. Scale helps, but it doesn’t turn this into a software margin profile.

Competition Intensifying: The same tailwinds lifting Willdan are drawing more attention from deep-pocketed firms. If giants like AECOM or Tetra Tech decide to lean in harder, they have the resources to compete aggressively on price and breadth.

Client Concentration: Big utility contracts are wonderful—until one gets rebid, reduced, or lost. Dependence on a relatively small number of major customers means a single non-renewal can hit results disproportionately.

Valuation: The stock has traded at a meaningful premium to industry averages on an earnings multiple basis. That premium can work when execution is flawless and growth stays strong—but it also leaves less room for error if expectations cool.

Execution Risk: Running multiple large programs across many geographies demands operational precision. Delivery issues, compliance mistakes, or customer disputes can ripple into reputation damage, contract losses, and margin pressure.

Key Metrics to Monitor:

For investors tracking Willdan’s ongoing performance, two KPIs matter most:

-

Net Revenue Growth (Organic): This is the cleanest read on underlying momentum, excluding acquisitions. Willdan reports net revenue separately from contract revenue to remove subcontractor pass-through costs. Organic net revenue growth is the signal that the engine is truly getting stronger.

-

Funded Backlog: This is future visibility—contracted work not yet recognized as revenue. Rising funded backlog suggests strong demand and sales execution. Falling backlog is often an early warning that the pipeline is thinning.

XIII. Lessons for Founders, Operators & Investors

Willdan’s sixty-year journey leaves a handful of lessons that travel well beyond energy efficiency:

On Survival: Sometimes the biggest innovation is admitting your old model won’t make it—and changing anyway. In the financial crisis, Willdan could have clung to municipal engineering and waited for California budgets to heal. Instead, leadership took a riskier path: they bet the company on energy efficiency, a market they were still learning. That bet didn’t just create growth. It kept Willdan alive.

On Timing: Policy waves create outsized opportunities for the companies positioned to ride them. California’s energy efficiency mandates in the 2000s, the IRA in 2022, and the AI-driven surge in electricity demand each opened a new window. The pattern is consistent: being ready when the wave hits matters more than trying to predict it perfectly.

On M&A: The hard part isn’t buying companies—it’s absorbing them. Deals can deliver instant scale, but value only shows up if integration is disciplined and patient. “Since joining Willdan in 2014, Mike has spearheaded the M&A activity that has expanded our energy efficiency services capabilities, and has significantly contributed to our strong growth in revenue, earnings and cash flow.” The flip side is just as real: one bad acquisition can erase years of progress.

On Market Selection: Boring, regulated markets can be incredibly lucrative. Utility programs aren’t flashy. Energy efficiency doesn’t come with consumer hype. But stable funding, sticky relationships, and a growing need for execution create a business that can compound—quietly, and for a long time.

On Competitive Advantage: In B2B services, relationships plus execution usually beat brand and technology. Willdan doesn’t win because it’s famous. It wins because it’s trusted, it knows the regulatory maze, and it can deliver at scale without creating problems for the utility and the regulator. That kind of credibility takes years to build—and it’s not easy to copy.

On Resilience: Surviving near-death experiences leaves scar tissue—and sometimes that scar tissue becomes a capability. Willdan lived through the 2008 crisis, then navigated COVID-era shutdowns of in-person programs. That experience builds an organization that knows how to protect liquidity, keep customers close, and keep operating when the plan stops working.

XIV. Epilogue: What's Next for Willdan?

As 2025 winds down, Willdan is in a place that would’ve sounded impossible back when it was fighting for survival in 2009: demand is rising, policy is supportive, and the company has real momentum. The IRA is still pushing money into the system. State efficiency mandates are getting tighter, not looser. Electrification keeps pulling load onto the grid. And AI data centers have turned “future demand” into a near-term scramble.

Contract wins are stacking up. Financial performance has been strong. The question now isn’t whether Willdan can play in this world. It’s whether it can keep winning without repeating the mistakes that almost derailed the story before.

A few strategic questions loom over the next chapter:

Can they maintain discipline while growing? The temptation is obvious: lean into the tailwinds, bid bigger, buy more, grow faster. But professional services firms don’t usually break because demand disappears. They break because execution slips—because they scale headcount, systems, and management processes too slowly for the work they’ve promised to deliver.

Will technology disrupt the consulting model? AI and automation are already changing how audits get done, how customers are targeted, how programs are designed, and how savings are measured and verified. That can be a threat if Willdan treats it like an add-on. It can also be a weapon if it uses technology to deliver faster, cheaper, and with fewer compliance errors—the things utilities and regulators care about most.

Have they learned enough about M&A to do it better? Willdan is buying again, and the APG acquisition in March 2025 looked like a more focused, capability-driven move than some of the earlier “scale at all costs” years. But acquisitions don’t fail at signing. They fail in the digestion. The risk never goes away—it just changes shape.

Can they expand margins while staying competitive? This will always be a people business. Willdan can get more efficient, standardize delivery, and improve utilization—but it can’t escape the basic physics of selling skilled labor. The long-term test is whether it can keep improving execution and productivity while still investing in the talent needed to win the next generation of work.

And that brings us to the investor question hanging over everything: is Willdan a long-term compounder, or a cyclical policy play?

The bull case says Willdan is positioned for a multi-decade buildout—decarbonization, grid modernization, electrification, and load growth—and that it can compound through disciplined organic growth with selective, well-integrated acquisitions. The bear case points to the flip side of the same coin: dependence on regulated spending, intensifying competition, and the reality that services businesses rarely earn “perfect execution” valuations for long.

The truth is probably messier than either narrative. Willdan isn’t a monopoly. But it does have real advantages in a market where relationships, credibility, and regulatory fluency matter. It isn’t immune to policy shifts, but the underlying direction of travel—toward a more electric economy—looks durable. And it isn’t cheap, but growth with visibility almost never is.

What’s not up for debate is the transformation itself. From a trailer in Cerritos to a billion-dollar company working at the center of America’s energy transition—that’s an unlikely arc, and one that says a lot about how “boring” businesses quietly become essential.

The next chapter is being written now. Whether it’s as dramatic as the last sixty years remains to be seen.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music