Weatherford International: The Phoenix of Oilfield Services

I. Introduction: A Corporate Resurrection Story

Picture this: July 2019. In a Houston bankruptcy court, Weatherford’s lawyers file the paperwork that makes it official: the company is going under Chapter 11. The filing would ultimately slash the balance sheet by nearly $8 billion of debt and wipe out the equity of tens of thousands of shareholders. On July 1, 2019, Weatherford International plc and two affiliated debtors each filed voluntary petitions for relief under Chapter 11 in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas. This was a company that had once traded above $50 a share. Now it was effectively worth pennies. One of the biggest oilfield-services bankruptcies in history had begun.

And then, less than two years later, Weatherford did something most companies don’t come back from.

On June 1, 2021, the company announced that Nasdaq had approved its application to relist Weatherford’s ordinary shares under the ticker “WFRD,” effective at the market open on June 2, 2021. In other words: the doors to the public markets swung back open. By July 15, 2024, the stock hit an all-time high since the relisting, reaching $135.00—a very real marker that the comeback wasn’t just a press release.

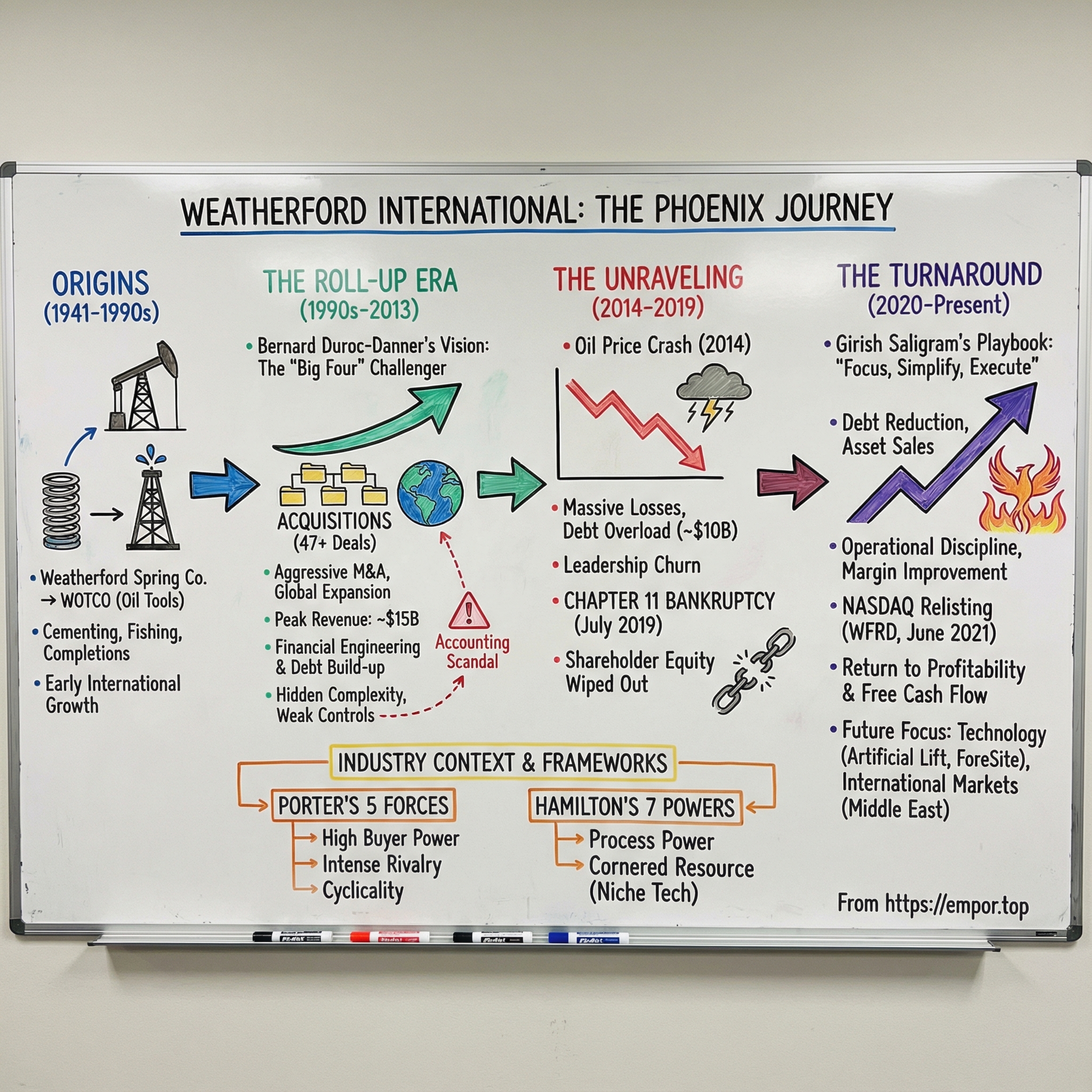

So how does a company go from a $15 billion-revenue giant, to bankruptcy, to a Nasdaq-listed business generating strong cash flows in under five years? Weatherford is a corporate life-cycle story in fast-forward: visionary ambition, an acquisition-fueled empire, financial engineering that didn’t hold up under stress, and then—after the collapse—an almost stubborn return to operational basics.

This also isn’t just one company’s drama. It’s a window into the oilfield-services industry, where the cycle is the boss, pricing power can vanish overnight, and the gap between aggressive growth and reckless leverage is razor-thin. If you want to understand cyclical businesses—how they scale, how they break, and how (sometimes) they rebuild—Weatherford is one of the clearest case studies you’ll find.

Today, the company sits at a fascinating inflection point. In 2024, Weatherford reported revenue of $5.51 billion, up from $5.13 billion in 2023. Under CEO Girish Saligram, it has worked to reshape itself from a bloated, debt-heavy conglomerate into something simpler, more focused, and more profitable. The question now is the one that matters to every turnaround story: is this a phoenix ready to fly again—or a survivor that’s learned to live smaller in a brutally hard industry?

Let’s find out.

II. The Oilfield Services Industry: A Primer

Before we zoom in on Weatherford, we need to understand the arena it fights in—because oilfield services might be the most unforgiving “normal” industry on earth. In the good years, it prints money. In the bad years, it can flatten even competent operators in a couple of quarters.

Oilfield services companies are the shadow workforce of the energy world. When an exploration and production company (an E&P) like ExxonMobil or Shell wants to drill and produce a well, it usually isn’t doing every step with its own people and its own gear. It hires specialists who already have the equipment, the crews, the know-how, and the ability to deploy all of it anywhere from West Texas to offshore West Africa.

That’s the lane Weatherford has lived in. Weatherford International plc provides equipment and services for drilling, evaluation, completion, production, and intervention across oil, natural gas, and geothermal wells worldwide. It operates through three segments: Drilling and Evaluation; Well Construction and Completions; and Production and Intervention. In practical terms, that means services like managed pressure drilling, directional drilling, and logging and measurement while drilling—exactly the sort of mission-critical work producers outsource when they want a well built and producing safely, quickly, and at a predictable cost.

A useful mental model is to treat producers like automakers. They decide what to build and where to sell it. Oilfield services companies are the supply chain and the factory tools: the equipment makers, the precision instrumentation, the installation crews, the maintenance team—all bundled together, and on call. They provide everything from drill bits that chew through rock thousands of feet underground, to sensors that read the formation in real time, to “artificial lift” systems that keep oil flowing after natural reservoir pressure fades.

And the economics? Brutal by design.

This is a capital-intensive business: fleets of specialized equipment, global logistics, and highly trained people who can’t be replaced overnight. Then layer in the defining feature of the whole sector—cyclicality. When oil prices fall, E&Ps cut capital spending fast, and oilfield services revenue follows right behind it. The early 2010s showed both ends of that whip-saw: oil was above roughly $125 a barrel in 2012 and stayed strong above $100 until late 2014, before sliding hard and dropping below $30 by early 2016. For service companies, that kind of move doesn’t just hurt pricing; it collapses utilization. Rigs get stacked. Projects get delayed. Negotiating leverage flips overnight.

Within that environment, Weatherford fought in the deep end. Its primary rivals were the global giants often called the “Big Three”: Schlumberger, Halliburton, and Baker Hughes. They compete directly with Weatherford across drilling, evaluation, completions, production, and intervention—often with broader portfolios, bigger footprints, and more staying power when the cycle turns.

Historically, the industry talked about a “Big Four”: Schlumberger, Halliburton, Baker Hughes, and Weatherford. But even at its peak, Weatherford was the smallest of the group by a meaningful margin. Schlumberger—the company Conrad and Marcel Schlumberger started in France back in 1926—grew into the category leader, operating in around 80 countries with about 82,000 employees. Weatherford today has roughly 19,000. That gap matters, because scale buys you a lot in this business: larger R&D budgets, faster tech rollouts, deeper distribution networks, and long-standing relationships with the world’s biggest oil companies.

And yet—despite all that—there’s a structural reason a fourth player could exist at all.

Big oil companies and national oil companies don’t want to be dependent on any single service provider, no matter how good it is. They deliberately maintain multiple vendor relationships to avoid getting boxed in by one company’s pricing or availability. That buyer behavior created a real opening for firms like Weatherford. It’s also the opening Weatherford’s leadership pushed through—first to build a global empire, and later, in a much harsher cycle, to discover just how thin the margin for error can be.

III. Origins & Early Growth (1941–1990s)

Every great corporate saga has an origin story, and Weatherford’s starts in a way only Texas could deliver.

In 1941, Jesse E. Hall Sr. founded the Weatherford Spring Company in Weatherford, Texas—about half an hour west of Fort Worth. It was a straightforward manufacturing shop, best known for making spring brakes for trucks and trailers. But Texas in the 1940s didn’t just run on highways. It ran on oil. And Hall saw that the bigger opportunity wasn’t in what was rolling down the road—it was in what was coming out of the ground.

By 1948, the company had shifted decisively toward the oil patch and rebranded as the Weatherford Oil Tool Company, often shortened to WOTCO. Ownership at that point sat with Jesse Hall, his son Elmer, and partners James E. Berry and Juan A. Perea. Weatherford entered oilfield services by doing the unglamorous work that keeps wells alive: cementing and completion tools. The company even pioneered a technique and equipment for cementing cased-hole wells—important, technical, and absolutely essential. It started by selling to U.S. operators, then quickly found its way into international oil fields. Before long, Gulf Oil was using Weatherford equipment in Venezuela.

Over the following decades, Weatherford kept leaning into the “must-have” parts of the well life cycle. It built a business around completion and cementing tools, and it developed a meaningful presence in “fishing”—the specialized craft of retrieving tools and debris that get stuck downhole. This wasn’t the kind of high-profile, cutting-edge service that made Schlumberger famous. It was the gritty, problem-solving work that operators pay for immediately, because a stuck well can burn money by the hour.

As the Weatherford name spread into Europe, it earned a reputation for reliability in products like scratchers and centralizers—hardware tied to casing cleaning and wellbore control. A significant portion of the business also came from retrieval contracts: removing the junk, tools, and debris that inevitably end up where they shouldn’t, thousands of feet underground. Weatherford kept adding services as it grew, and the oil boom of the 1970s pushed the company to expand and diversify even faster. By the time the petroleum bubble burst in the early 1980s, Weatherford had broadened well beyond its original tool-making roots.

At the same time, other corporate threads were forming off to the side—threads that would eventually get woven into Weatherford’s future.

Energy Ventures (EV) was founded in 1972, initially as an offshore oil and gas explorer and producer. It would evolve over time, and later become part of the Weatherford story through merger.

Then there was Enterra: a diversified energy service and manufacturing business selling products and services to the petroleum exploration, production, and transmission industries worldwide. Its specialties included rehabilitating older pipeline systems and providing tools and services for drilling and servicing both onshore and offshore wells. By the time Enterra later merged with Weatherford, it was viewed as a technology leader within the sector. It expanded internationally in 1988 with the $35 million purchase of CRC Evans. In 1994, it bought Total Energy Services Co. in a deal valued at more than $310 million. Notably, Enterra brought strong cash flow and zero debt.

By the end of the 1980s and into the 1990s, the broader industry had absorbed a hard lesson. The violent swings of the prior two decades—OPEC-driven price spikes, then the brutal crash of 1986—made one thing clear: in oilfield services, the cycle decides who gets to live. And surviving the cycle often requires scale.

That set the stage. Consolidation was coming. And the people who would turn Weatherford from a capable tool-and-services company into an acquisition-driven global giant were about to walk onstage.

IV. The Roll-Up Era: Building an Empire Through M&A (1990s–2000s)

If Weatherford’s story has a central character—part visionary, part villain depending on who’s telling it—it’s Bernard Duroc-Danner. His arrival didn’t just change the company’s strategy; it changed its identity. Under his leadership, Weatherford stopped thinking like a tools-and-services operator and started behaving like a consolidator with a mission: build a global challenger to the industry’s giants.

Duroc-Danner wasn’t a career Weatherford insider. In May 1987, he founded Energy Ventures Inc., or EVI—an oilfield service and equipment company that, by his own account, began with no product lines, no operations, and very limited financial resources. In its first year, EVI generated less than $20 million in revenue. But the ambition was clear from the start: grow through deal-making, roll up capabilities, and use acquisitions to buy scale faster than you could build it.

The pivotal moment came in 1998. A $2.6 billion merger between Weatherford Enterra and EVI created Weatherford International, with Duroc-Danner as CEO. His vision was straightforward and audacious: Weatherford would join the top tier of oilfield services and compete directly with Schlumberger, Halliburton, and Baker Hughes.

It was a classic challenger narrative—less “steady operator,” more “build the fourth network.” Just as Rupert Murdoch launched Fox to take on the established TV giants, Duroc-Danner wanted Weatherford to become a fourth force in oilfield services. The comparison captured both the boldness and the willingness to take risks that defined the era.

And the acquisition machine did not let up. With Duroc-Danner at the helm, Weatherford bought 47 smaller oilfield service providers between July 1998 and August 2011. Over the long arc of his tenure, Weatherford’s growth was driven by hundreds of acquisitions around the world, plus continuous internal development. Along the way, the original public stock (NYSE: EVI) split four separate times, ultimately 32-to-one.

One of the clearest wins from this period was Grant Prideco. After more than a decade of building it through a series of transactions, Weatherford spun out Grant Prideco in 2000 as a dividend to shareholders. At the time, it represented more than a third of Weatherford’s traded market equity value. The value creation was real: in 2008, National Oilwell (now NOV Inc.) acquired Grant Prideco for $7.5 billion.

But the spinoff success didn’t mean the broader roll-up strategy was clean or easy.

Bloomberg data shows that between 1998 and 2011, Weatherford’s 47 acquisitions came with publicly disclosed financial terms for only 29 of them. Those disclosed deals alone totaled more than $6.1 billion, paid through various combinations of cash, stock, and debt. And Weatherford built a reputation in the market for paying aggressively. As University of Houston energy economist Ed Hirs put it: “Weatherford was known for aggressive acquisitions… Weatherford would pay top dollar for these acquisitions. Most of them were funded by debt.”

To be fair, the strategy wasn’t irrational. In the late 1990s and 2000s, major oil companies and national oil companies increasingly wanted “one-stop shop” providers—service companies that could handle multiple parts of the well lifecycle under one umbrella. Consolidation let Weatherford show up with a broader toolkit, win bigger contracts, and expand quickly into key regions like the Middle East, Russia, and Latin America. Between 1999 and 2008, Weatherford grew rapidly through a mix of acquisitions and organic expansion. Part of that plan included developing its asset base with a primary focus on mature fields—an approach that diverged from broader industry trends at the time.

But running alongside the operational expansion was something else: aggressive financial engineering, especially around taxes and corporate structure. Weatherford moved its corporate domicile repeatedly—shifting from the U.S. in 2002 to Bermuda, then to Switzerland in 2009, and later announcing in April 2014 that its board had approved moving its legal domicile again, this time from Switzerland to Ireland. Through these shifts, the company kept its operational office in Houston, Texas.

The mechanics went beyond just where the company said it “lived” on paper. Weatherford also used hybrid financial instruments and structures that transferred revenue from higher-tax jurisdictions like the U.S. and Canada to lower-tax entities in places like Hungary and Luxembourg.

This kind of domicile shopping was designed to reduce the tax bill. And in the 2000s—when oil prices were strong and acquisitions kept compounding growth—it could look like a masterclass in corporate optimization. But it also added complexity, opacity, and risk. Later, it would become tangled up in one of the company’s biggest scandals.

For now, though, the engine was roaring: buy, integrate, expand—repeat. And Weatherford was getting bigger fast.

V. Peak Weatherford: The $15 Billion Giant (2008–2013)

From 2008 to 2013, Weatherford hit its high-water mark—the moment when Bernard Duroc-Danner’s roll-up vision looked not just plausible, but inevitable. Oil was back above $100 a barrel, E&Ps were spending aggressively, and the service ecosystem was booming right along with them.

Weatherford rode that wave hard. Coming out of 2008, it was generating close to $10 billion in revenue, and it kept expanding through 2009 and beyond—growing at more than 20% a year. On paper, it looked like the full-package oilfield services provider customers said they wanted. The portfolio stretched across well construction and production: artificial lift systems that keep mature wells flowing, completion tools, drilling services, wireline evaluation. If there was a major stage in the life of a well, Weatherford had a business line for it.

At its peak, the company had around 60,000 employees operating in more than 100 countries. Weatherford was firmly the fourth-largest oilfield services company in the world—the “Big Four” framing finally made sense. And the stock, split four times over the growth years, minted plenty of paper wealth for early holders.

But the empire had a hidden cost: complexity. Hundreds of acquisitions meant hundreds of systems, cultures, and operating processes—stitched together across continents, often faster than management could standardize them. Buying companies was the easy part. Making them run like one company was the hard part.

The warning signs started flashing before the oil market ever turned. By 2010, Weatherford was posting quarterly losses as large as $110 million. It returned to profitability in 2011, but the underlying issues didn’t go away. In the second quarter of 2012, Weatherford reported an $849 million loss, driven by a write-down of assets it had previously bought. It was the largest loss in the company’s history at the time—an admission, in accounting form, that some of the dealmaking simply hadn’t created the value the strategy promised.

And here’s the detail that matters most: even as oil marched back toward $100 a barrel in the first half of 2014, Weatherford was still losing money. The company’s last profit came in the third quarter of 2014.

That should have been impossible. In this industry, $100 oil is supposed to lift most boats. Weatherford’s couldn’t rise, because the weight was self-inflicted: operational sprawl, integration drag, and a balance sheet built for good times.

Then came the scandal that made the cracks impossible to ignore.

The SEC announced that Weatherford agreed to pay a $140 million penalty to settle charges that it inflated earnings through deceptive income tax accounting. Two senior accounting executives also agreed to settle charges tied to the scheme. According to the SEC’s order, Weatherford fraudulently lowered its year-end provision for income taxes by roughly $100 million to $154 million per year to better align reported results with projections and analyst expectations.

The SEC found that, between 2007 and 2012, Weatherford issued false financial statements that inflated earnings by more than $900 million, violating U.S. GAAP. The misstatements touched the numbers investors care about most—net income, earnings per share, the effective tax rate, and other key financial metrics. The underlying problem wasn’t just bad judgment; it was weak internal controls. Weatherford didn’t have accounting systems robust enough to properly identify and account for income taxes across a sprawling multinational structure.

The fallout was severe. Weatherford had to restate its financial statements three times in 2011 and 2012. And because management had repeatedly touted its favorable effective tax rate as a competitive advantage, the restatements didn’t just correct math—they shattered credibility. Investors were left with the impression that the carefully engineered tax structure was far more successful than it actually was.

The mechanics were less “brilliant fraud” and more “end-of-quarter panic.” Executives made post-closing adjustments to force the company’s tax rate into the range it had promised publicly, even when real operations couldn’t support it. When Duroc-Danner told analysts the effective tax rate would be 17%, the accounting got bent until the numbers said 17%.

And that wasn’t the only regulatory fire. The SEC also alleged that Weatherford and its subsidiaries falsified books and records to conceal improper payments, as well as commercial transactions with Cuba, Iran, Syria, and Sudan that violated U.S. sanctions and export control laws. Regulators said Weatherford lacked effective internal accounting controls to monitor risks of improper payments and to prevent or detect misconduct. The company reaped more than $59.3 million in profits from business obtained through improper payments, and more than $30 million in profits from improper sales to sanctioned countries. Swiss-based Weatherford agreed to pay more than $250 million to settle those charges.

By the time the dust settled, the picture was unmistakable: a company where the drive to become a global powerhouse had outrun the unglamorous essentials—controls, integration discipline, and governance. Peak Weatherford wasn’t just the top of the mountain. It was also the moment the base started giving way.

VI. The Unraveling: When Everything Goes Wrong (2014–2019)

If Peak Weatherford was the intoxicating high, 2014 to 2019 was the brutal hangover. The cycle turned, the company was already off-balance, and suddenly there was nowhere to hide.

Oil prices didn’t just drift lower; they fell off a cliff. Brent and WTI dropped about 60% between June 2014 and January 2015—one of the fastest, most violent collapses in modern oil history. A surge in U.S. shale supply met slowing demand growth, and Saudi Arabia chose to keep production high to defend market share instead of cutting to stabilize prices. The result was a global glut that deepened through 2015 and into 2016. Oil that had been above roughly $100 a barrel until late 2014 sank to under $30 by January 2016.

For healthy oilfield services companies, that kind of move is painful. For Weatherford—already dealing with integration sprawl, weak controls, and a heavy debt load—it was devastating.

Losses piled up in ugly, headline-grabbing bursts: about $475 million in the fourth quarter of 2014, $1.2 billion in the fourth quarter of 2015, and $1.8 billion in the third quarter of 2016. The stock price told the same story, sliding from $15.49 at the start of 2014 to $5.62 by the end of 2016. As one observer put it, “Over time, the institutional investor base became increasingly frustrated with the company's performance.”

In November 2016, Duroc-Danner stepped down. He retired, took the title chairman emeritus, and left behind a company that was still structurally trapped: too much debt, too little profitability, and a competitive position that kept eroding as customers squeezed pricing and shifted work to stronger operators.

Weatherford’s leadership reshuffle began immediately. In November 2016, the company named Krishna Shivram interim CEO and Robert Rayne chairman of the board. Then, in March 2017, Weatherford appointed Mark A. McCollum as president and chief executive officer and added him to the board. The company also announced William E. Macaulay as chairman of the board of directors.

McCollum came from Halliburton and walked into a job defined by triage. His playbook centered on selling non-core assets to reduce debt and narrow Weatherford’s focus toward areas like drilling equipment and digital services. One of the bigger moves came in December 2017, when Weatherford sold its hydraulic fracturing and pressure pumping business to Schlumberger for $430 million.

But the math was unforgiving. Years of acquisition-driven expansion had left Weatherford with a debt burden that asset sales couldn’t meaningfully outrun. This was a company with roots in Texas going back to 1941 that had grown into the nation’s fourth-largest oilfield services provider—and accumulated roughly $10 billion in debt along the way. Despite being headquartered in Switzerland, incorporated in Ireland, and operating out of Houston, the underlying fact was simple: Weatherford hadn’t turned a profit since the third quarter of 2014.

By early 2019, the endgame was approaching. Management described a company facing a “turbulent and uncertain future”: leverage above 10.0x EBITDA, a share price stuck below $1.00 for an extended period, and a looming liquidity shortfall. Weatherford was effectively a penny stock after being delisted from the New York Stock Exchange. Its market value had collapsed to about $367 million—tiny next to roughly $7.6 billion of debt.

The solution wasn’t another asset sale or a clever refinance. It was a reset.

Under the restructuring agreement, Weatherford would eliminate about $5.8 billion of its $7.5 billion in long-term debt. The price was brutal: existing shareholders were essentially wiped out, and the unsecured noteholders would take roughly 99% of the equity.

On July 1, 2019—the “Petition Date”—Weatherford International plc, Weatherford International Ltd., and Weatherford International, LLC filed voluntary petitions for Chapter 11 in the Southern District of Texas. The company kept operating as a debtor-in-possession while the restructuring moved through court. On September 11, 2019, the bankruptcy court confirmed the plan (as amended). And on December 13, 2019, Weatherford emerged from Chapter 11 after completing the reorganization.

Coming out, the capital structure was radically different. The company’s unsecured senior and exchangeable senior notes—about $7.6 billion—were cancelled under the plan. Weatherford said it had reduced roughly $6.2 billion of outstanding funded debt, put in place $2.6 billion of exit financing, added a $195 million letter-of-credit facility, and had about $900 million of liquidity.

For shareholders, it was total loss. For Weatherford the operating company, it was something else: a second chance.

The only question was whether anyone could turn that chance into a comeback.

VII. The Turnaround: Girish Saligram's Playbook (2020–Present)

Emerging from bankruptcy is one thing. Fixing the company you’ve just rescued is another. And for Weatherford, the months after Chapter 11 didn’t feel like a clean new beginning. They felt like more turbulence—right when the world was about to throw the industry one more gut punch.

In June 2020, Weatherford announced a shake-up at the top: CEO Mark A. McCollum resigned, along with CFO Christian Garcia. The company named Karl Blanchard—then vice president and chief financial officer—as interim CEO.

The timing was brutal. COVID-19 had triggered another oil-price collapse, and suddenly the “second chance” balance sheet didn’t look like enough of a cushion. A recent SEC filing warned that the oil crash had created a financial crisis that could push Weatherford toward another default—and even another bankruptcy. As one critique of the moment put it: Weatherford had emerged at the wrong time with too much debt. It exited Chapter 11 with roughly $2.7 billion of debt after shedding about $6.7 billion—an enormous reduction, but not one built for a fresh, historic demand shock.

Then came the real turning point: a leadership choice that signaled Weatherford wasn’t going to out-finance its problems anymore. It was going to out-operate them.

Weatherford’s Board announced that effective October 12, 2020, Girish K. Saligram would become President and Chief Executive Officer, and also join the Board. Saligram had previously served as Chief Operating Officer at Exterran Corporation. As Chairman Charles M. Sledge said at the time, Saligram was “a seasoned leader with extensive international experience… and a deep understanding of the oil and gas sector,” positioned to lead Weatherford forward.

Saligram’s resume read like a blueprint for operational discipline. Before Weatherford, he served at Exterran as COO and, after joining in 2016, as President, Global Services. Before Exterran, he spent 20 years at GE in roles of increasing responsibility across global industrial businesses, including General Manager, Downstream Products & Services for GE Oil & Gas. Earlier, he ran GE Oil & Gas Contractual Services out of Florence, Italy. And before his oil-and-gas years, he spent 12 years inside GE Healthcare across engineering, services, operations, and commercial roles.

In other words: not a roll-up architect. Not a financial engineer. An operator.

Saligram’s thesis was simple enough to fit on a whiteboard: “Focus, simplify, execute.” Where Duroc-Danner had built an empire by adding businesses, Saligram set out to build a business by removing distractions. Portfolio rationalization meant exiting unprofitable regions and shedding non-core assets. The strategic focus narrowed to areas where Weatherford actually had differentiation—especially artificial lift systems and key well construction capabilities.

And then came the symbolic milestone—the moment Weatherford proved it was no longer stuck in corporate limbo.

On June 1, 2021, Weatherford announced Nasdaq had approved its application to relist its ordinary shares under the ticker “WFRD,” effective at the market open on June 2. Saligram framed it as a return to the public markets with confidence in Weatherford’s “operating posture and commercial profile,” and a belief the company could create sustainable profitability.

The relisting mattered. But the real proof had to show up in the operating results.

By 2024, management was talking less about survival and more about execution—safety, margins, and cash. In Weatherford’s year-end commentary, Saligram acknowledged softer activity in Latin America and a more cautious tone in a few geographies during the fourth quarter, but described 2024 as a year of “new operational highs,” including the best safety record in the company’s history, margin expansion, and solid cash generation. He emphasized that margins and cash flow were the cornerstone of Weatherford’s strategy, and said the company believed it was well-positioned to generate strong cash flow in 2025 while targeting EBITDA margins in the high 20s over the next few years.

The numbers backed up the narrative shift. In 2024, Weatherford reported revenue of $5.513 billion, up from $5.135 billion in 2023. Operating income increased to $938 million from $820 million. Net income rose to $506 million from $417 million. Cash flow from operations was $792 million, and adjusted free cash flow was $524 million.

Profitability improved, too: adjusted EBITDA margin expanded by 197 basis points for the year, reaching 25.1%.

And Weatherford wasn’t just generating cash—it was starting to give it back. In the fourth quarter of 2024, the company repurchased about $49 million of shares and paid $18 million in dividends. Across 2024, since launching its shareholder return program earlier in the year, Weatherford repurchased roughly $99 million of shares and paid $36 million in dividends, for total shareholder returns of $135 million. On January 29, 2025, the Board declared a cash dividend of $0.25 per share.

Meanwhile, the balance sheet—once the company’s Achilles’ heel—kept getting lighter. Weatherford reduced gross debt by more than $1 billion since Q4 2021, and by the end of 2024 its net leverage ratio stood at 0.49x.

That’s the essence of the comeback. Five years earlier, Weatherford was running leverage above 10x EBITDA and headed into Chapter 11. Now it was operating with conservative leverage, producing consistent cash flow, and returning capital to shareholders.

The story stopped being “the bankruptcy.” It became “the turnaround.”

VIII. Technology, Innovation & Competitive Positioning

If Weatherford’s turnaround is about discipline, its next chapter is about differentiation. It can’t outspend Schlumberger or out-muscle Halliburton on scale. So it has to win by being better in the pockets of the market where performance and reliability matter—and where customers will pay for it.

One of those pockets is artificial lift. Weatherford’s Artificial Lift Solutions business positions the company as a lift and optimization specialist: the teams and tools operators bring in when they want to squeeze more production out of a field, extend well life, and keep the whole system running with fewer surprises. In mature basins, artificial lift isn’t optional. Reservoir pressure declines, the easy barrels disappear, and production increasingly depends on hardware, software, and field execution working together.

Weatherford’s offering spans the classic workhorses—reciprocating rod pumps, the “nodding donkeys” you see across Texas—and other systems like progressing cavity pumps. The strategic point isn’t that these tools are new. It’s that the installed base is enormous, the operating environments are unforgiving, and the best providers differentiate through uptime, optimization, and the ability to tailor lift to the well’s stage in its life cycle.

That’s where the company’s digital push comes in. Weatherford’s transformation narrative increasingly centers on ForeSite, its production-optimization platform. This is the bridge from “we sell equipment” to “we help run your field better”—using real-time analytics and physics-based modeling to spot uplift opportunities, extend run life, and reduce wasted interventions.

Weatherford has pointed to a case where ForeSite delivered roughly $18 million in annual savings for a Fortune 500 producer, based on improvements in efficiency, equipment uptime, and production. The results were strong enough that the customer ordered a broader rollout across U.S. and international operations. In Weatherford’s description, the savings came from a mix of personnel efficiency, longer equipment run-life, and additional revenue from wells transitioning more quickly from natural flow to artificial lift.

Another niche where Weatherford sees momentum is managed pressure drilling, or MPD—technology and services designed to precisely control pressure in the wellbore, especially in complex formations where conventional drilling can invite costly problems. The company has highlighted Modus, its MPD offering, as being deployed across multiple regions, with demand for MPD packages and managed pressure wells expected to support future growth.

And then there’s the sustainability layer. As operators face mounting pressure to reduce emissions, Weatherford is positioning parts of its portfolio around helping customers lower the energy intensity of production. That includes carbon management services and technologies aimed at reducing emissions while keeping output stable—an important messaging shift for an oilfield services company that wants to stay relevant in a world that’s trying to decarbonize without turning the lights off.

Put it all together, and you get the shape of the new Weatherford: a company trying to pair its legacy strengths in production and well construction with more software, more automation, and more “measurable outcomes” for customers—while also committing to net-zero emissions by 2050 and investing in digital transformation.

IX. The Broader Industry Context & Future Outlook

To understand where Weatherford can go next, you have to zoom out to the industry it serves—because oilfield services is not the same game it was in Weatherford’s peak years. The rules have tightened. Customers are more disciplined. And the easy growth that came from “drill more wells, everywhere” is gone.

Weatherford now operates in 75 countries, and as of Q2 2025 it generated about 80% of its revenue outside the U.S. That international footprint isn’t an accident; it’s the center of gravity. The Middle East and North Africa region is the company’s biggest market, contributing 44% of Q2 2025 revenue.

That’s a very deliberate bet. North American shale has become a knife fight: more commoditized work, more vendors chasing the same budgets, and constant pricing pressure. International markets—especially the Middle East—tend to look different. Contracts are longer. Customer relationships, often with national oil companies, are stickier. And the work mix can support better pricing and more predictable demand.

But “international” doesn’t mean “stable.” Weatherford expected international revenue to decline by mid-single digits in 2025, driven primarily by two problem areas: Mexico and Russia. The company anticipated a meaningful drop in activity in Mexico that would weigh on 2025 revenue. And in Russia, sanctions and foreign-exchange volatility have added friction and uncertainty, also contributing to revenue declines.

Against that backdrop, Weatherford’s 2025 revenue guidance was $5.10 billion to $5.35 billion—essentially signaling a year where execution and mix matter more than headline growth.

Over all of this hangs the biggest macro force in energy: the transition. For oilfield services, it’s both a long-term threat and a near-term reality check. If oil demand declines over time, the total addressable market eventually shrinks. But that “eventually” matters. The transition is likely to take decades, and in the meantime the world still runs on legacy fields that need constant maintenance. In that environment, Weatherford’s focus—artificial lift, production optimization, and getting more out of mature wells—fits the direction of travel. If operators spend less on frontier exploration and more on maximizing existing assets, the companies that keep those wells producing efficiently don’t disappear. They become more essential.

X. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Breaking into oilfield services at real scale is close to impossible. You need massive capital for equipment, labs, and field infrastructure, plus the ability to move people and gear across the globe on short notice. And you’re not just competing against other contractors; you’re competing against incumbents with deep R&D budgets, mature operating systems, and relationships that have been built well-by-well over decades.

Those relationships are the moat. Major operators and national oil companies don’t hand mission-critical work to someone new just because they’re cheaper. They want a track record, safety performance, certifications, and proof you can execute when things go sideways at 12,000 feet. The one caveat: new entrants can still show up in narrow lanes. Niche specialists can win a sliver of the market, and tech startups can disrupt specific service lines without trying to become “the next Schlumberger.”

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Suppliers—steel, chemicals, equipment manufacturers, and specialized components—can gain leverage when supply chains tighten. But the big service companies have enough scale to negotiate, multi-source, and push back. Supplier power matters, but it isn’t what decides winners and losers in this industry.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

This is the industry’s core problem. The customer base is concentrated, sophisticated, and ruthless about procurement. Oil majors, national oil companies, and large independents routinely multi-source the same service lines, and they know exactly how to pit providers against each other—especially when activity slows.

The same dynamic that created space for a fourth player also cuts against everyone’s margins. Customers don’t want to depend on one vendor, but they also don’t want to pay premium prices for work they view as interchangeable. Real pricing power shows up only in highly specialized, mission-critical services—where performance, reliability, and risk reduction matter more than day rates.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Substitution in oilfield services doesn’t look like a single product replacing another. It shows up as shifting techniques: different completion designs, different drilling approaches, different well architectures. Some E&Ps also bring certain services in-house. And technology keeps changing the menu—electric versus hydraulic systems, automation, and alternative workflows that can reduce the need for traditional service intensity.

Over the long run, there’s a bigger substitute looming: the energy transition itself. A world that uses less oil and gas is a world that demands fewer oilfield services.

Competitive Rivalry: VERY HIGH

Competition here is relentless. The majors fight for global share, and regional specialists fight to defend their home turf. When oil prices fall, it turns into a price war fast: utilization drops, fleets sit idle, and vendors cut pricing to keep crews working. Many service lines are commoditized, which makes differentiation hard and the race-to-the-bottom dynamics very real.

Only in the last few years—after so much industry-wide financial pain—has discipline improved at all, and even that can disappear with the next cycle.

Overall Assessment: Oilfield services is structurally tough. Buyer power is high, rivalry is extreme, and cyclicality amplifies every mistake. To win, you need scale, real technology differentiation, or defensible niche leadership. Weatherford’s entire comeback strategy is built around living inside those constraints, not pretending they aren’t there.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale helps in R&D, manufacturing, and regional infrastructure. But oilfield services scale is inherently “local.” You can’t easily share a rig in Texas with a job in Saudi Arabia, and you can’t teleport crews across continents without cost and friction. Schlumberger captures scale advantages best; Weatherford has less of that cushion.

2. Network Economies: LOW

This isn’t naturally a network business. There are early hints of data-driven network effects as platforms like ForeSite collect performance information across installations, but it’s still nascent and unlikely to create a true winner-take-all dynamic.

3. Counter-Positioning: LIMITED

There aren’t many radically different business models available in oilfield services. Startups can be nimble, but they don’t have the relationships or footprint to take on integrated incumbents. In Weatherford’s case, bankruptcy forced a kind of counter-positioning: simplifying and narrowing focus while others still carried broader sprawl. But it wasn’t some clever strategic gambit—it was survival.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE

Switching costs exist, but they aren’t absolute. Once equipment is installed, workflows are set, and crews are trained, customers have inertia—especially under long-term contracts. But if the price gap is big enough, or performance slips, customers will move. Switching costs vary by service line: they tend to be higher in artificial lift, where systems are deeply integrated, and lower in more commoditized work like cementing.

5. Branding: LOW-MODERATE

This is B2B, so the “brand” is really reputation: safety record, execution, reliability, and technical capability. Weatherford’s bankruptcy damaged that reputation, and rebuilding trust takes time. Still, branding isn’t a primary competitive advantage in this market; performance is.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Weatherford does have assets that are hard to replicate quickly: proprietary technology and patents in areas like artificial lift and managed pressure drilling, long-standing relationships with national oil companies, specialized talent, and established operational footholds with logistics infrastructure. None of this is magical, but it is real—and it takes time to build.

7. Process Power: MODERATE-HIGH

This is the heart of Saligram’s plan. In a business where many offerings blur together, operational excellence becomes a competitive weapon: project execution, supply chain reliability, safety culture, and the discipline to do the boring things well, every time. Weatherford’s margin expansion under the new regime is the clearest proof that process improvement is showing up in results.

Weatherford's Current Power Assessment: Weatherford’s edge today is primarily Process Power, supported by Moderate Cornered Resource in specific niches like artificial lift. The turnaround works only if that operational discipline holds—because the industry itself doesn’t give out many structural advantages for free.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

The turnaround story has real weight because it’s built on operations, not optics. Under Saligram, Weatherford’s improvements read less like financial engineering and more like the hard, repeatable stuff: tighter execution, simpler decision-making, and a company that’s been right-sized for today’s market instead of yesterday’s ambitions.

The bull case also leans heavily on where Weatherford still has genuine strength. Artificial lift and well construction aren’t sexy, but they’re essential—and they become more valuable as fields age. Mature assets need optimization, not hype. That’s where Weatherford’s integrated lift offering and ForeSite platform fit: less “sell equipment,” more “keep wells producing, longer, with fewer surprises.”

Geography helps, too. International markets—especially the Middle East—tend to reward long-term relationships and steady execution more than North American shale’s constant churn. The Middle East and North Africa region made up 44% of Q2 2025 revenue, and longer-duration contracts with national oil companies can provide a level of visibility the industry rarely offers.

And then there’s the balance sheet—the scar tissue that became an advantage. Post-bankruptcy, Weatherford has kept leverage conservative. With a net leverage ratio of 0.49x, it has far more flexibility than the old Weatherford ever did. That doesn’t make it immune to the cycle, but it does mean the company isn’t forced into desperate refinancing games the moment oil turns south.

Put it all together and you get a final bull-case kicker: credibility is returning. The stock’s recovery since the relisting reflects a market that’s starting to believe the new operating model. If Weatherford continues to execute, it could re-rate over time. And in a consolidating industry, a leaner, focused Weatherford could also show up on the M&A radar.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with the obvious truth: oilfield services is still a structurally punishing industry. Buyer power is high, pricing can feel commoditized, and cyclicality turns small mistakes into big problems. Even strong operators can struggle to deliver consistent returns across the cycle.

Then there’s the macro overhang no one in the sector can fully escape: the energy transition. Even if oil and gas demand declines slowly over decades, the uncertainty alone can compress valuations and keep large pools of institutional capital on the sidelines.

Weatherford also remains the smaller player versus Schlumberger and Halliburton in many markets, and that scale gap can translate into an innovation gap over time. Bigger peers can spend more on R&D, roll out technology faster, and absorb downturns with less pain. If the technology frontier shifts quickly, Weatherford can’t afford to be late.

Reputation is another lingering drag. Bankruptcy doesn’t just wipe out shareholders; it leaves a memory. Trust—especially with major operators—takes years to rebuild, and some customers may stay cautious about concentrating critical work with a company that recently needed court protection to survive.

Operationally, there’s also the question of “what’s next.” Margin improvement can’t come forever from cost cutting and simplification. If much of the low-hanging fruit is already captured, future gains have to come from sustained pricing, mix, and execution—harder levers to pull.

Finally, concentration risk is real. Heavy exposure to international markets can be a feature, but it’s also a vulnerability: political instability, sanctions, and currency swings can hit results quickly. Weatherford has specifically flagged Russia as an area where sanctions and FX volatility create friction and uncertainty, contributing to revenue declines.

And the biggest bear argument is the one that haunts every service company: the cycle always comes back. The balance sheet is healthier, but a prolonged oil-price collapse would still stress the model. In this industry, another crash is less a question of “if” and more “when.”

Key Metrics to Monitor

If you want a clean dashboard for whether the turnaround is holding, these are the signals that matter most:

1. Adjusted EBITDA Margin: This is the clearest read on whether Weatherford’s operational discipline is sticking. Management has targeted EBITDA margins in the “high 20s” over the next few years. Full-year 2024 came in at 25.1%. The direction matters more than any single quarter.

2. Free Cash Flow Generation: Positive, consistent free cash flow is what separates a real turnaround from a temporary upswing. In 2024, adjusted free cash flow was $524 million. The key test is whether it stays meaningfully positive even when revenue gets choppy.

3. International vs. North America Revenue Mix: Weatherford’s strategy leans toward higher-margin international work, particularly in the Middle East. A mix that continues to skew international generally supports the bull case. A shift back toward North America, or weakness in core international markets, raises harder questions.

Secondary signals: market share in artificial lift, renewal and expansion with major customers, and safety performance—which, in this business, is often the best proxy for whether the culture of execution is real.

XII. Epilogue & Reflections

Weatherford’s story lands because it isn’t just an oilfield-services drama. It’s a clean case study in a tension every cyclical, capital-intensive business eventually faces: you can engineer the numbers for a while, but you can’t engineer your way around operations forever.

Bernard Duroc-Danner was, by most accounts, a gifted dealmaker. He recognized the consolidation wave early and built Weatherford into something customers could actually buy from as a “one-stop shop.” He expanded the footprint globally. He squeezed the tax structure through a series of corporate domicile moves. For a long stretch, the scoreboard seemed to reward it: more revenue, a bigger profile, and a seat at the table with the industry’s giants.

But deals aren’t a substitute for a unified operating system. When you bolt together hundreds of businesses, you don’t just inherit products—you inherit processes, cultures, IT stacks, accounting practices, and risk. Weatherford never built the management infrastructure to make all of that run like one company. Complexity piled up. Execution frayed. And when the accounting scandal surfaced—executives pushing adjustments to force results to match expectations—it wasn’t just a compliance failure. It was a signal that the pressure to perform had outpaced the organization’s ability to perform.

Bankruptcy did what years of “restructuring plans” couldn’t: it made simplification non-negotiable. Reducing more than $7 billion of debt was the financial reset. But the real change came after—under Girish Saligram—when the company shifted from expansion as an identity to execution as a discipline. Focus on what Weatherford actually does well. Cut distractions. Improve delivery. Protect margins. Generate cash.

There’s also a broader energy-transition takeaway hiding in plain sight. The Weatherford that went into Chapter 11 couldn’t reliably make money even when oil was around $100 a barrel. The Weatherford that emerged learned how to generate cash in a world with oil in the $70s. That doesn’t erase long-term transition risk, but it complicates the simplistic story that everything tied to fossil fuels is destined to become unprofitable. In a world that still depends on legacy production for decades, services that optimize existing wells can remain economically essential—especially when they’re run with discipline.

Could the cycle break Weatherford again? In this industry, it’s never wise to say “never.” Cyclicality is structural, and downturns have a way of exposing whatever a company is still pretending is fine. But compared to 2019, Weatherford now has two advantages it didn’t then: conservative leverage and a tighter operating model. Those don’t make it immune. They just give it time—time to respond instead of time running out.

And then there’s the part that doesn’t show up in a leverage ratio. Tens of thousands of people lived through the collapse: layoffs, uncertainty, customers second-guessing commitments, the stigma that comes with a bankruptcy headline. The comeback wasn’t just a financial recap. It was a human grind—employees who stayed, rebuilt trust job-by-job, and helped an 80-plus-year-old company earn its way back to health. That may be the most remarkable part of the whole Weatherford story.

XIII. Recommended Resources

If you want to go deeper on Weatherford—and on the oilfield-services world that shaped it—here are a few places to start.

Essential Reading: - The Frackers by Gregory Zuckerman is the fastest way to understand the shale revolution that rewired the economics of the entire services sector. - Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power by Steve Coll is a great lens on how the biggest customers think—and why that mindset makes “buyer power” so crushing in this industry. - The Prize by Daniel Yergin is still the definitive sweep of oil’s boom-and-bust history, which is really the backdrop for every chapter of Weatherford’s story.

Primary Sources: - Weatherford’s 10-K filings from 2010–2024 are the story in real time. Read them in sequence and you can literally watch the tone shift: confidence, complication, crisis, and then discipline. - The bankruptcy court filings are dense, but they’re the clearest look at how the 2019 restructuring actually worked—especially if you’re curious about who got paid, who got wiped out, and why. - Earnings call transcripts—particularly Saligram’s from 2021 onward—are where the turnaround comes into focus in management’s own words: what they chose to prioritize, what they walked away from, and how they measured progress.

Industry Context: - Energy Information Administration (EIA) reports are the cleanest baseline for oil-market fundamentals and the cycle’s broader direction. - Schlumberger annual reports are a useful benchmark for how the category leader talks about technology, margins, and global mix. - Journal of Petroleum Technology (JPT) is a solid ongoing read for what’s changing technically—especially in drilling, completions, and production optimization.

Weatherford really did rise from the ashes. Whether it becomes a durable compounder or simply a smarter survivor is the open question. Either way, as a case study in hubris, cyclicality, and operational comeback, it earned its spot in the business history canon.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music