Workday: The Cloud Crusaders Who Rewrote Enterprise Software

Introduction and Episode Roadmap

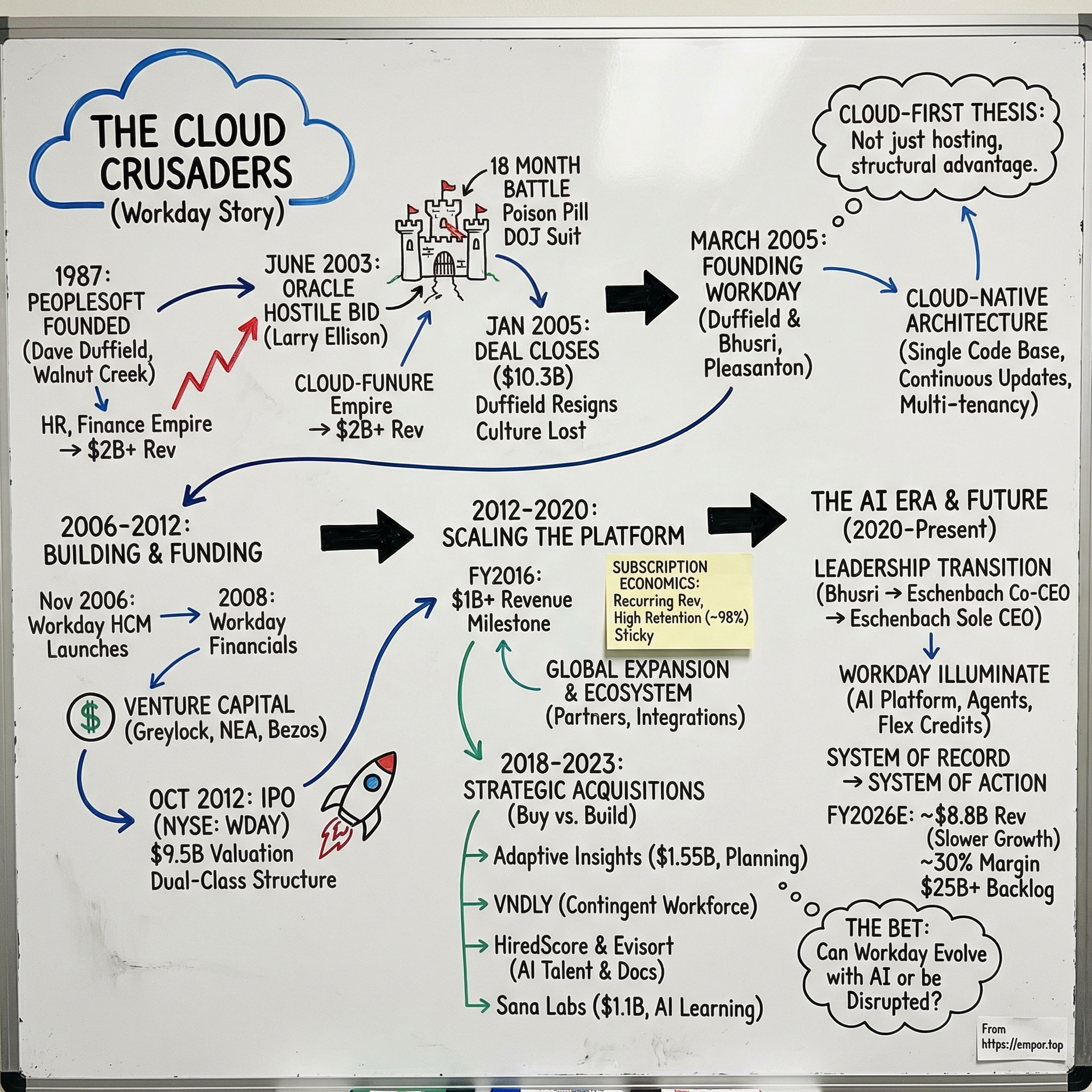

In enterprise software, the most enduring companies often come with something extra: a chip on the shoulder, a grudge, a mission. Workday’s origin has all three. This is a story about a founder who built a giant, watched it get swallowed by a rival, and then came back with a new playbook—cloud-first, subscription-driven, and designed to outmaneuver the very incumbents who thought they’d won.

That founder is Dave Duffield, the engineer-turned-CEO behind PeopleSoft. When Oracle’s takeover finally closed, Duffield and his longtime partner Aneel Bhusri didn’t fade into retirement. They walked out of the wreckage and went right back to work—determined to build the next-generation enterprise suite the way it should have been built all along.

Today, that second act is Workday: a cloud-based platform for human capital management and financial management that serves a huge slice of the world’s largest organizations, including more than 65 percent of the Fortune 500. It has grown into a business generating roughly $8.5 billion a year in revenue—a scale that puts it firmly in the top tier of enterprise software.

What makes Workday so interesting isn’t just the size. It’s the set of forces colliding inside the company.

First, there’s the cloud disruption thesis: if you build natively for the internet, you’re not just hosting old software somewhere new—you’re creating a structural advantage that compounds with every release, every customer, every integration.

Second, there’s the revenge story: Duffield and Bhusri didn’t merely want to start another company. They wanted to prove that the old guard—Oracle, SAP, the on-premise era—had been living on borrowed time.

Third, there’s the subscription economics engine: recurring revenue, high switching costs, and retention that stays incredibly sticky, with gross retention hovering around 98 percent. In enterprise software, that kind of “once you’re in, you rarely leave” dynamic is the closest thing to gravity.

And now, looming over all of it, is the question every software company is being forced to answer: AI. Can Workday evolve from being a system of record into a system that actively helps run the business—through automation, insights, and intelligent agents? Or does it risk becoming the next legacy incumbent, disrupted the way it once disrupted others?

By fiscal year 2025, Workday’s revenue was $8.45 billion, and it had built a subscription backlog north of $25 billion. But the easy growth years are gone. Expansion has slowed from the 30-percent era into the low teens. The stock is well off its peak. And competitors—Oracle, SAP, and increasingly Microsoft—are spending heavily to win the next platform shift.

So this is the full story: the PeopleSoft empire and Oracle’s hostile raid; the founding of Workday and the cloud-first bet; the IPO that turned it into a public-market heavyweight; and the AI-era transition that will decide whether Workday stays a category-defining leader—or becomes the kind of company it was born to replace.

The PeopleSoft Empire and Oracle's Hostile Takeover

To understand Workday, you have to start with PeopleSoft—because Workday was born from its ashes.

Dave Duffield founded PeopleSoft in 1987 out of a spare bedroom in Walnut Creek, California. He was already in his late forties, a veteran of enterprise software who had previously co-founded Integral Systems. He wasn’t the Silicon Valley archetype. No swagger, no “move fast and break things.” Duffield was an engineer’s engineer: methodical, calm, and intensely customer-driven. He had a reputation for picking up support calls himself. He brought his golden retriever to the office. Employees often described PeopleSoft as a family—an odd thing to say about an ERP company, but it was real.

PeopleSoft’s core insight was almost embarrassingly straightforward: HR software was a mess, and organizations would pay a lot for a system that actually worked. Through the 1990s, Duffield turned that wedge into an empire—first dominating HR, then expanding into financials, supply chain, and customer relationship management. By the early 2000s, PeopleSoft was doing more than $2 billion in annual revenue and serving many of the largest organizations in the world. It was widely seen as the number-two enterprise applications vendor behind SAP—and ahead of Oracle’s applications business.

Then Larry Ellison came calling.

On June 6, 2003, Oracle launched a hostile bid for PeopleSoft, initially valuing the company at $5.1 billion, or about $16 per share. The timing was deliberate. Just days earlier, PeopleSoft had agreed to acquire JD Edwards for $1.7 billion—another major ERP vendor. Oracle’s offer wasn’t just aimed at PeopleSoft; it was an attempt to swallow both companies in one move. The industry was stunned. Oracle was famous for databases, not best-in-class applications. So the bid didn’t feel like a strategic merger. It felt like a raid.

PeopleSoft’s board rejected the offer immediately, and what followed became one of the most bruising corporate battles tech had ever seen. For eighteen months, the fight sprawled across boardrooms, courtrooms, and front pages. PeopleSoft rolled out a poison pill so aggressive it bordered on surreal: if a hostile acquirer succeeded, it would trigger refunds to customers worth two to five times what they’d paid for their licenses. That wasn’t just legal maneuvering. It was a flare in the sky: we are not going quietly.

Customers largely agreed. A survey of PeopleSoft and JD Edwards customers found that 95 percent didn’t want the deal. In February 2004, the U.S. Department of Justice sued to block the acquisition, arguing it would reduce competition and raise prices.

Oracle kept tightening the screws, raising its bid from $16 to $21 to $26 a share, then adjusting again as PeopleSoft’s results softened under the pressure of the standoff. Inside PeopleSoft, things got uglier. In October 2004, the board fired CEO Craig Conway, accusing him of misleading analysts about the takeover’s impact. It was a company trying to fight off an attacker while simultaneously tearing out its own leadership.

The end came in December 2004. A federal judge ruled the DOJ hadn’t proven the merger would harm competition. European regulators signed off too. With the legal roadblocks cleared and the siege grinding on, PeopleSoft’s board finally gave in. Oracle’s final offer: $26.50 per share—about $10.3 billion, more than double the original bid. The deal closed in January 2005.

Oracle moved fast after that. Around 5,000 PeopleSoft employees were laid off. Duffield resigned. The culture he’d spent nearly two decades building—the family vibe, the pride in the product, the customer-first identity—was dismantled in weeks.

For Duffield, this wasn’t just losing a company. PeopleSoft was his life’s work. He had built it from nothing and watched it get absorbed into a rival’s empire. But Duffield wasn’t the type to disappear. He was already thinking about what came next—and he had a partner who was thinking the same thing.

Founding Workday: The Cloud-First Vision (2005–2008)

Aneel Bhusri had been PeopleSoft’s chief strategist: younger than Duffield, Harvard Business School–trained, and one of Duffield’s most trusted lieutenants after joining the company in 1993. He also sat on the board of Greylock Partners, giving him a front-row seat to what was starting to look like the next platform shift. From that vantage point, Bhusri watched Salesforce prove something that would’ve sounded almost heretical to enterprise IT just a few years earlier: you could deliver serious business software over the internet instead of installing it on a customer’s own servers.

That wasn’t just a new delivery method. It changed the economics and the relationship. Lower upfront costs. Faster rollouts. Automatic updates instead of endless upgrade projects. And a subscription model that turned one-time license deals into predictable, recurring revenue.

So when Oracle finally closed the PeopleSoft acquisition in January 2005, Duffield and Bhusri didn’t take a long victory lap into retirement. In March—barely two months later—they incorporated Workday. The speed told you everything. They weren’t shopping for an idea. They already had the blueprint.

The plan was audacious: build an enterprise-grade system for HR and financial management entirely in the cloud, from scratch. Not “hosted.” Not retrofitted. Cloud-native.

In 2005, that was still a leap. Most enterprise IT leaders looked at the cloud like a security nightmare. CRM data was one thing; HR and finance were something else entirely. Payroll. Benefits. Employee records. The general ledger. Putting that information on servers you didn’t own, run by a company you didn’t control, felt reckless. Duffield and Bhusri were betting that fear would fade—and that the operational advantages would win. Continuous updates. Lower total cost of ownership. Real-time analytics. Access from anywhere, including the mobile world that was about to explode.

Duffield funded the first $15 million himself, and Greylock came in alongside him. They set up shop in Pleasanton, California—PeopleSoft’s old home turf. It was practical, because so many PeopleSoft veterans lived nearby. And it was symbolic, too: a quiet statement that the story wasn’t over. They began recruiting former PeopleSoft engineers—people who knew enterprise HR and finance down to the plumbing—and plenty of them had their own reasons for wanting another shot after the Oracle takeover.

Workday’s first product, Workday Human Capital Management, launched in November 2006. Early on, it focused on core HR—employee records, org structures, benefits administration. But the more important part was what sat underneath. The architecture was built to expand. The team used an object-oriented data model designed to be extended over time, and they made a defining decision: every customer would run on a single code base. No forks. No “special” versions. Everyone on the latest release.

That choice sounds obvious now, but it wasn’t then. It meant Workday could ship improvements continuously, and customers didn’t get trapped in the on-premise nightmare of upgrade cycles that took years, cost fortunes, and often broke whatever had been customized along the way. Instead of treating upgrades like traumatic events, Workday could make them a normal part of the product.

The first customers were mid-sized companies willing to take a calculated risk on a new platform from a team with a reputation. Flextronics, the electronics manufacturer, was one of the early wins. Each implementation became another proof point that cloud-based enterprise software could handle messy, real-world complexity at scale. By 2008, Workday had enough credibility to start aiming higher—toward the large enterprises that would eventually define the company.

And this is the strategic core of the Workday bet: architecture as destiny. Oracle and SAP’s flagship systems were designed in the 1980s and 1990s for on-premise deployment. They ran in customer data centers, were deeply customized per client, and were updated through painful, multi-year upgrade projects. Retrofitting that world for the cloud—something both incumbents would attempt—was like trying to turn an aircraft carrier into a speedboat. You could add a web interface and call it “cloud,” but the underlying complexity didn’t go away.

Workday started with a blank sheet. Multi-tenancy, continuous delivery, and modern web standards weren’t add-ons—they were the foundation. The payoff wouldn’t be fully obvious in the early years, but the advantage was real. And once it started compounding, it would be hard to catch.

Building the Product Suite and Raising Capital (2008–2012)

By 2008, Workday had done something that still felt slightly insane in enterprise IT: it proved you could run core HR in the cloud and not have it fall apart. The next step was the bigger prize. If Workday wanted to be more than “the HR cloud company,” it had to move into the financial backbone of the enterprise—the general ledger, planning, and the system CFOs live in every day.

Workday Financial Management launched with the same cloud-native DNA as HCM, but aimed squarely at the CFO: real-time visibility, more automation, and a system designed to change as the business changed. Strategically, this mattered because financials weren’t just another module. They were the gateway to the full ERP budget.

Then came the curveball that, weirdly, strengthened Workday’s hand: the 2008 financial crisis. CFOs and CIOs went into spending triage mode. Traditional on-premise ERP came with a brutal upfront bill—licenses, hardware, armies of consultants, and years of implementation risk. Workday’s subscription model reframed that pain into something far more palatable: a predictable operating expense. The crisis didn’t make enterprise sales easy, but it made “pay over time, get updates automatically” sound a lot less like a gamble and a lot more like common sense.

To fund the push, Workday raised serious capital. In April 2009, it announced a $75 million round led by New Enterprise Associates. In October 2011, it added another $85 million, bringing total capital raised to $250 million. The investor list signaled that Workday was no longer an interesting experiment—it was becoming a platform bet: Greylock, NEA, Bezos Expeditions, T. Rowe Price, and Morgan Stanley.

By spring 2012, the traction was hard to ignore. Workday had 310 customers, spanning mid-sized companies and massive global enterprises. And in enterprise software, customer logos don’t just represent revenue—they represent permission. Every time a big company bet its HR or finance stack on Workday, it made the next prospect a little less afraid of switching.

Because switching was the whole point, and it was never casual. Moving off Oracle or SAP meant months of implementation work, data migration, and change management. But once customers made the leap, they tended to stay. Satisfaction and stickiness—rather than sunk-cost lock-in—became the foundation of Workday’s economic model.

That’s where the subscription model really changed the game. The old world ran on perpetual licenses: a massive upfront payment, then annual maintenance fees. The vendor got paid either way, upgrades were traumatic, and incentives skewed toward selling the next deal—not making customers successful. Workday flipped it. Customers paid annually, typically tied to employee count or the breadth of modules. If Workday didn’t keep delivering value, the customer could walk at renewal. So Workday built its business around customer success and relentless product improvement—because it had to.

The incumbents saw what was happening and moved, but slowly and imperfectly. Oracle rolled out Fusion Applications, positioned as the next-generation suite that would unify the best of PeopleSoft, JD Edwards, and Oracle’s own apps—but it didn’t arrive until 2011, years after the original promise. SAP, rather than building cloud HCM from scratch, acquired SuccessFactors in 2011 for $3.4 billion. Different strategies, same message: Workday’s thesis was right, and the giants were chasing.

And the numbers started to tell the story investors love. Revenue climbed from $25.2 million to $68.1 million to $134.4 million across three consecutive fiscal years. Losses were real—$47.3 million in the first half of fiscal 2012—but this was the classic SaaS trade: spend aggressively to win the market, then let recurring revenue do what recurring revenue does. The only open question was whether the public markets would buy into that bet too.

The IPO and Public Market Debut (2012)

On October 12, 2012, Workday hit the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker WDAY. The IPO was priced at $28 a share. By the closing bell, it had rocketed up 74 percent to $48.69—after climbing as high as 83 percent intraday. All in, the first-day pop put Workday’s value at nearly $9.5 billion when you included unexercised stock options.

Workday sold 22.75 million Class A shares and raised $637 million. It was the biggest U.S. tech IPO since Facebook just five months earlier—and unlike Facebook’s famously messy debut, Workday’s was clean, confident, and loud. Investors weren’t just buying a company. They were buying a thesis: the cloud had arrived in the most conservative corner of software, and it was coming for the core.

The obvious question was why the market was willing to pay up for a business that was still losing money. The answer was the subscription engine Workday had been building from the start. Every new customer wasn’t a one-time license sale; it was the beginning of a long relationship, with revenue that tended to recur, expand, and compound over time. Retention was already strong—north of 95 percent even in the early years—and the opportunity ahead was massive. HR and finance software was a huge global market, and most of it was still running on legacy on-premise systems that were expensive to maintain and painful to upgrade. Workday was selling into a generational transition, with a product designed for the new world.

Then there was the governance structure—quietly, one of the most important details of the whole IPO. Workday went public with a dual-class setup: Class A shares for the public carried one vote each, while the Class B shares held by Duffield and Bhusri carried ten votes per share. Critics hated it then and still do today. Supporters argue it protects long-term decision-making. But for Duffield, it wasn’t an abstract corporate-finance debate. He’d watched PeopleSoft get taken over against his wishes. This time, founder control wasn’t a preference. It was a scar tissue strategy.

And the moment carried a lot of emotional weight. Seven years after PeopleSoft was absorbed into Oracle, its spiritual successor was now a public company flirting with a $10 billion valuation. Duffield, at seventy-two, had pulled off something almost unheard of in enterprise software: building a second multi-billion-dollar company from scratch. For the PeopleSoft alumni who’d followed him to Pleasanton, it felt like validation—and maybe even a little vindication.

But the story wasn’t over. Going public didn’t end the fight. It just moved Workday into a bigger arena, with quarterly scrutiny, higher expectations, and two giants—Oracle and SAP—now fully awake and coming for the cloud crown.

Scaling in the Public Markets (2012–2020)

After the IPO, Workday entered the part of the story where great SaaS companies either prove the model… or get exposed by it. Workday proved it.

Revenue kept climbing, year after year, until it cleared a psychological and strategic milestone: more than $1 billion in annual revenue in fiscal 2016. Workday announced it like a flag planted on a new continent, and it mattered for more than bragging rights. It took PeopleSoft almost a decade to reach that mark. Workday got there in roughly ten years from founding—and it got there on recurring subscription revenue, not one-time license deals. In the public markets, that difference isn’t accounting trivia. It’s the entire bet.

That growth didn’t come from quick wins. It came the hard way: long, high-stakes enterprise sales cycles and even longer implementations. These were six-to-twelve-month courtships, followed by rollouts that could take a year or more. But once a Fortune 500 company finally made the leap, the relationship tended to be durable. A big customer could mean tens of millions a year in subscription fees, and with retention consistently above 95 percent, Workday wasn’t just adding revenue—it was stacking it, renewal after renewal.

The company also expanded its product footprint without losing its discipline. In 2016, Workday launched a cloud-based student information system, pushing beyond corporate HR and finance into higher education. It was a logical adjacency: universities had many of the same administrative needs as large companies, and the sector had been chronically underserved by modern enterprise software. The student system didn’t just open a new lane of growth; it also deepened Workday’s position with higher-ed customers that already trusted Workday for HR and financial management.

Of course, the incumbents didn’t stand still. Oracle finally began shipping its cloud applications suite in earnest, and SAP’s SuccessFactors gained momentum. They both had a built-in advantage Workday couldn’t replicate: massive installed bases running legacy on-premise systems, creating a ready-made pool of customers to “move to the cloud.” But that advantage cut both ways. Those cloud offerings often felt like legacy software wearing a cloud costume—ported, not reinvented. Workday kept hammering the same point it had from day one: architecture matters. If you built for the cloud from the start, you didn’t just run somewhere different—you worked differently.

And then there was the ecosystem—one of the most underappreciated levers in enterprise. No company runs HR and finance on an island. Workday had to integrate into messy reality: payroll providers, identity systems, analytics tools, procurement platforms, industry-specific software. So Workday invested heavily in APIs, integrations, and a partner network that could implement and extend the product. By the late 2010s, the biggest systems integrators—Deloitte, Accenture, PwC, KPMG—had built dedicated Workday practices. That created its own compounding machine: more partners meant more implementation capacity, which supported more customers, which attracted still more partners.

International expansion became the next frontier. Early on, Workday was primarily an American success story. But global enterprises wanted one system that could handle HR and finance across dozens of countries—each with its own labor laws, tax rules, reporting standards, currencies, and languages. Making that real was painstaking, unglamorous work. Country by country, Workday had to earn the right to say, “Yes, we can run this globally.” But once it could, the addressable market widened dramatically.

By fiscal 2020, Workday’s annual revenue was around $3.6 billion. The company that started as a post-PeopleSoft response to Oracle had become a full-fledged enterprise platform. Losses narrowed as the subscription base scaled, and a clearer path to sustained profitability started to emerge.

But scaling alone wasn’t going to define the next chapter. To keep expanding, Workday would need new products, new capabilities, and eventually, a new kind of ambition—one that would pull it toward acquisitions, platform expansion, and the early shape of its AI strategy.

Strategic Acquisitions and Platform Expansion (2018–2023)

Workday’s organic growth engine was strong. But by the late 2010s, the mission was getting bigger than what you could ship purely through internal roadmaps. If Workday wanted to own more of the enterprise “back office,” it needed to pull key capabilities into the platform faster—and the fastest way to do that was acquisition.

The defining deal of this era was Adaptive Insights. Workday announced the acquisition in June 2018 and closed it in August, paying $1.55 billion. Adaptive was a cloud planning and analytics business with nearly 4,000 customers and about $107 million in trailing revenue, growing around 30 percent. It had been lining up for its own IPO when Workday stepped in with an offer reportedly about double what the public markets were expected to pay.

The strategic logic was clean: Workday Financial Management was built for recording what already happened—transactions, close, reporting. Adaptive was built for what happens next—budgeting, forecasting, scenario planning. Put them together and you get a closed loop: actuals flowing straight into plans, and plans feeding back into how the business operates. Workday eventually renamed the product Workday Adaptive Planning in 2020, and it became a core pillar of the finance suite rather than a sidecar add-on.

In November 2021, Workday made another targeted bet, acquiring VNDLY for $510 million. VNDLY focused on external workforce management: contractors, freelancers, and other contingent labor. That mattered because the “workforce” was no longer synonymous with “employees,” but most traditional HCM systems still acted like it was. VNDLY helped Workday customers see and manage the blended reality—full-time plus contingent—in one place.

After that, the thesis widened and the pace picked up, especially as AI started shifting from buzzword to buying criteria. In early 2024, Workday acquired HiredScore, an AI-powered talent orchestration platform founded by Athena Karp. HiredScore applied AI to match candidates to roles, surface internal mobility opportunities, and help reduce bias in hiring.

Later in 2024, Workday announced the acquisition of Evisort, an AI-powered document intelligence company founded by a team from Harvard Law and MIT. Evisort could read and extract meaning from contracts, invoices, and other unstructured documents—pulling key terms, flagging risk, and triggering workflows. The deal was estimated at $250 to $300 million.

And then came the biggest swing: in September 2025, Workday announced a definitive agreement to acquire Sana Labs for about $1.1 billion. Sana was a Swedish AI company behind Sana Learn and Sana Agents, blending learning management, content creation, and AI-driven automation. The announcement landed at Workday Rising 2025, and CEO Carl Eschenbach called it “transformational”—a signal that Workday saw AI and enterprise knowledge as a new platform layer, not just features sprinkled on top.

Step back, and you can see the shape of the strategy. Workday wasn’t trying to remain a narrow best-of-breed HR-and-finance vendor. It was trying to become a broader enterprise platform: plan the business, run the finance core, manage the full workforce (including contingent), understand contracts and documents, and increasingly automate routine work through AI.

That ambition comes with a classic risk: platforms can overreach. Try to be everything to everyone, and you end up great at nothing. But Workday’s retention suggested customers were voting for the integrated approach—even if certain modules weren’t always the absolute best standalone product in their category.

The build-versus-buy decision also revealed a pragmatic truth about the moment Workday was in. To keep up—especially in AI—shipping everything in-house wasn’t enough. Specialized startups were moving faster in narrow domains, and buying proven capability was often quicker and more predictable than building from scratch. Workday’s acquisition spree was, in a way, an admission of how quickly the market was evolving—and how determined it was not to get caught flat-footed.

The AI Era and Leadership Transition (2020–Present)

From 2020 onward, Workday’s story has been shaped by two forces moving in tandem: a planned handoff at the top, and a push to make AI central to what the product is—not just what it does.

The leadership shift started in 2020, when Workday promoted Chano Fernandez to co-CEO alongside Aneel Bhusri. Fernandez, a Spanish-born executive who had led Workday’s European business, brought a sharper go-to-market lens to balance Bhusri’s product and strategy instincts. But the arrangement didn’t last. In December 2022, Workday said Fernandez would be replaced as co-CEO by Carl Eschenbach, a Sequoia Capital general partner who’d been on Workday’s board since 2018. The plan was clear: Eschenbach would ultimately take the CEO role, and Bhusri would move to executive chair.

Eschenbach was a very particular kind of choice. Before Sequoia, he spent fourteen years at VMware and rose to president and COO—exactly the sort of resume you want if your next chapter is “scale, efficiency, and enterprise execution.” At Sequoia, he’d had a wide-angle view across enterprise software. Bringing him in wasn’t just a personnel change; it was a signal that Workday’s next phase would put operational discipline and market expansion on equal footing with product innovation.

On February 1, 2024, Eschenbach became Workday’s sole CEO. Bhusri shifted into the executive chair role, focused on long-term direction, strategic counsel, and innovation. Notably, the transition was steady—no drama, no whiplash—at a time when enterprise customers can get skittish if they sense instability at the vendor they trust with payroll and the general ledger.

Meanwhile, the AI arc had been quietly forming for years. Workday’s early machine learning features—like Workday Skills Cloud, which maps and understands skills across the workforce, and Workday Talent Insights, which helps managers spot development opportunities and retention risks—were valuable, but they were evolutionary. They improved existing workflows without fundamentally changing the relationship users had with the system.

The bigger leap came with Workday Illuminate. Illuminate wasn’t positioned as a single feature or a standalone product. It was presented as an AI platform—a way to embed agents across the Workday suite so the software could move beyond being a system of record, where people enter data and pull reports, into a system of action, where AI can surface insights, recommend next steps, and carry out tasks.

In May 2025, Workday introduced seven new Illuminate agents spanning contingent workforce sourcing, contract intelligence, document-driven accounting, frontline worker management, and employee self-service. Then at Workday Rising in September 2025, it announced another wave aimed at performance reviews, workforce planning, financial close, and cost analysis. Alongside the agents, Workday rolled out Workday Flex Credits: a commercial model that lets customers buy a pool of credits and apply them across different agents and capabilities. The intent was simple—make it easier to try AI, scale what works, and avoid forcing customers into rigid, one-feature-at-a-time purchasing decisions.

This AI push also reinforced the acquisition and ecosystem moves Workday was already making. It tied directly into the Sana Labs acquisition and into a broader data strategy, including Workday Data Cloud, built in collaboration with Databricks, Salesforce, and Snowflake, so customers could blend Workday data with external sources for deeper analytics. Workday also announced an integration between its Agent System of Record and Microsoft Entra Agent ID, positioning Workday as a governance layer for managing and controlling AI agents in the enterprise.

Financially, Workday performed like a company entering a more mature stage: healthy, steady, and increasingly margin-focused. Fiscal year 2025 revenue reached $8.45 billion, up 16 percent, with subscription revenue of $7.72 billion. Through the first three quarters of fiscal 2026, growth held around the low teens, with subscription revenue guidance of $8.82 billion for the full year. Non-GAAP operating margins expanded into the high twenties to around 30 percent, reflecting the operating leverage that shows up when a subscription business scales and growth moderates. Operating cash flow topped $2.4 billion in fiscal 2025, and free cash flow was projected at $2.65 billion for fiscal 2026.

One of the more telling indicators was backlog. Total subscription revenue backlog reached $25.96 billion at the end of Q3 fiscal 2026, up 17 percent year over year—faster than recognized revenue growth. In other words, demand and bookings looked stronger than the growth rate suggested, hinting that revenue could stabilize, and potentially pick up, as backlog converts over time.

Workday’s installed base also continued to look like a fortress. The company had more than 75 million users under contract, and gross revenue retention stayed around 97 to 98 percent—extraordinary stickiness in a category where switching is expensive, risky, and disruptive. Net revenue retention sat just above 100 percent, pointing to modest but consistent expansion inside existing customers through additional modules and growing user counts.

Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

Workday’s rise isn’t just a great enterprise-software narrative. It’s also a practical playbook—both for operators building companies and for investors trying to understand what really drives enduring value.

The power of founder-led revenge. Duffield and Bhusri didn’t start Workday because a spreadsheet told them to. They started it because Oracle had taken something they’d spent years building, and they were determined to prove there was a better way. That kind of personal motivation is easy to dismiss as drama, but it can be an unfair advantage. It creates urgency, attracts people who want to run through walls, and hardens a culture around execution. The takeaway isn’t that anger is required to build something great. It’s that deep personal stakes tend to produce a level of endurance and focus that “good opportunity, nice market” rarely does.

Cloud-native versus retrofitted architecture matters. This is the structural lesson at the center of the Workday story. Oracle and SAP had the customers, the distribution, and decades of enterprise credibility. Workday had a blank sheet of paper. But that blank sheet turned into compounding advantage. Multi-tenancy lowered the cost to operate and support the product. Continuous delivery meant the product improved without customers enduring upgrade hell. A single code base meant every improvement benefited everyone. Incumbents could copy pieces of this, but fully matching it would have required breaking with their legacy architectures—and by extension, disrupting the very customers who paid the bills. This is the innovator’s dilemma in its most literal form.

Subscription economics create compounding machines. Workday is a clean example of why great SaaS businesses can feel almost inevitable once they hit scale. When gross retention stays extremely high, the base doesn’t decay much. When net retention sits above 100 percent, the base expands even before you add new customers. And because subscription revenue is recognized over time, the income statement lags reality: bookings strength can take a while to show up, and bookings weakness can take a while to show up too. That lag creates resilience—but it can also create blind spots. If you’re analyzing the business, you can’t stop at reported revenue. You have to watch backlog and bookings, because that’s where the future is hiding.

Customer success is the real sales engine. In enterprise SaaS, the initial sale gets you in the building. Renewals and expansions are what build the company. Workday invested early in making customers successful, and the payoff shows up in retention that borders on “hard to believe” for software this mission-critical. The most persuasive sales pitch Workday can ever have is a credible customer telling another credible customer: this worked, and we’d never go back.

Platform versus best-of-breed is a strategic choice, not a right answer. Over time, Workday has moved from “HR in the cloud” to a broader platform that spans HCM, financials, planning, workforce management, and now AI. The upside is obvious: integration, cleaner data, fewer vendors, and fewer seams for the organization to trip over. The downside is just as real: specialists can out-innovate you in narrower categories. Workday’s bet is that, in the enterprise, integration and coherence win because fragmentation is the tax everyone is trying to escape. So far, the stickiness of the customer base and the durability of demand suggest the bet has been more right than wrong.

The dual-class structure reflects hard-won experience. Dual-class shares are controversial for good reason. But Workday’s structure wasn’t an academic governance experiment—it was a direct response to trauma. Duffield lived through what it feels like to run a public company that can’t stop a hostile acquirer. Dual-class control gave Workday insulation to make longer-term bets without constantly managing quarterly pressure or activist risk. Whether that freedom has always been used perfectly is debatable. But the underlying logic is clear: it’s a governance choice shaped by history, not theory.

Analysis: Bear Case versus Bull Case

The Bull Case

Workday’s bull case starts with a simple idea: it’s the category leader in a market that’s still mid-migration. Yes, a lot of HR and finance has moved to the cloud. But a meaningful slice of the global enterprise base is still running legacy, on-premise systems. Every one of those deployments is a future replacement cycle—and Workday is often on the shortlist when that cycle finally begins.

That opportunity is amplified by the dynamic that makes enterprise SaaS so powerful: switching cuts both ways. It’s hard to win a Workday deal because implementing core HR or the general ledger is painful. But once Workday is in, it’s just as painful to rip out. Gross retention in the 97 to 98 percent range isn’t just a nice KPI; it’s evidence that customers aren’t merely tolerating the product. They’re building their operating model on top of it.

AI is the potential accelerant. If Workday Illuminate delivers what it’s pitching—agents that automate routine HR and finance work, pull signals out of messy, unstructured data, and make the system feel less like a database and more like a co-pilot—then AI becomes a new reason for existing customers to expand. The Sana Labs acquisition and the Flex Credits model both point to a management team trying to package AI in a way enterprises can actually buy, pilot, and scale.

Zooming out, Workday also benefits from several of Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers. Switching costs are the clearest. Migrating off Workday is the kind of multi-year, high-risk project CIOs avoid unless they absolutely have to. There’s also a lighter—but real—ecosystem effect: as adoption grows, the partner network deepens, implementations get more standardized, and the platform becomes easier to live on. And then there’s counter-positioning, the original advantage: Workday was cloud-native from the start, while incumbents had to protect legacy cash cows. That edge has narrowed as Oracle and SAP have improved their cloud suites, but it still matters in how quickly Workday can ship, update, and operate on one code line.

The Bear Case

The bear case is just as straightforward: the company is getting bigger, and the growth is slowing. Workday has moved from the 30-plus percent era to low-teens growth in fiscal 2026. Some of that is inevitable math. But some of it reflects a very real question: how much greenfield is left at the top end of the market?

Workday has penetrated more than 65 percent of the Fortune 500. That’s a flex—but it also means the easy logos are gone. From here, growth has to come from harder paths: expanding internationally, moving deeper into the mid-market, and selling more modules into existing customers. All three can work, but none are as fast as landing a fresh, marquee enterprise.

Competition is also getting sharper. Oracle has poured resources into its cloud applications suite and can pull customers through a migration pipeline powered by its installed base. SAP SuccessFactors remains a serious HCM rival. Microsoft is an increasingly credible threat via Dynamics 365 and its proximity to enterprise workflows—plus its unique advantage with LinkedIn data. And in AI, the competitive set widens beyond ERP: Workday is now measured against horizontal AI platforms and fast-moving specialists that don’t have to support a broad suite.

Through Porter’s Five Forces, you get a mixed picture. Barriers to entry are high—building enterprise-grade HR and finance software is hard, and selling it is harder. But large enterprise buyers have real bargaining power, especially when they can credibly run competitive bake-offs. The longer-term risk is substitution: AI-native systems that don’t just modernize ERP, but route around it. That’s not tomorrow’s problem, but it’s the kind of platform shift that can sneak up on incumbents. Supplier power is generally modest, though reliance on major cloud infrastructure providers like AWS and Azure does introduce some concentration risk.

The stock has reflected the market’s ambivalence. Trading around $210 in early 2026, Workday was well below its all-time high of $307 from February 2024. A Goldman Sachs downgrade to Neutral in January 2026 pointed to a crowded HCM market and slower-than-hoped AI monetization. The consensus price target of $278 suggests upside—but it also quietly admits the core truth here: outcomes depend on whether Workday can turn AI into real, repeatable expansion revenue, not just compelling demos.

The KPIs That Matter

If you’re tracking Workday from here, two metrics carry the most signal.

First: subscription revenue backlog growth. It’s the closest thing to a forward-looking dashboard for bookings momentum and the future revenue curve. When backlog is growing faster than reported revenue—as it has recently—it suggests demand may be healthier than the headline growth rate implies.

Second: gross revenue retention. This is the load-bearing wall of the model. Workday’s retention in the 97 to 98 percent range is exceptional for software this mission-critical. But if that starts to slip, it’s not a rounding error—it’s an early warning that the product is losing grip, competition is finding cracks, or customers are no longer seeing enough value to keep expanding their relationship.

Epilogue: If We Were CEOs

Running Workday in 2026 means leading a company that already won the first war—cloud versus on-premise—and now has to win the second: turning AI from a feature into the new operating system for how work actually gets done.

The first priority would be execution on the agent strategy. Workday Illuminate has to graduate from impressive demos to repeatable, measurable outcomes customers can point to: hours saved, cycle times cut, better decisions made. The Sana Labs acquisition was a big, expensive bet at $1.1 billion, and it can’t just produce good keynote moments—it has to translate into capabilities customers adopt broadly and renew eagerly. Flex Credits is the right kind of packaging because it lowers the “try it” barrier, but the product has to earn the expansion by delivering real value fast.

Next: international. Workday still leans heavily on North America, which means Europe and Asia-Pacific remain the clearest runway. The work is unglamorous—localizations, regulatory requirements, payroll and finance realities that vary country by country—but each country you truly support becomes a durable wedge. Done well, it’s not just growth; it’s a moat, because global readiness is slow to build and hard to copy quickly.

Then there’s the mid-market. Workday’s DNA is Fortune 500: powerful, configurable, and priced like mission-critical infrastructure. But the mid-market—companies in that roughly 1,000 to 10,000 employee range—is far larger and increasingly cloud-ready. Winning here likely means a different playbook: simpler packaging, faster implementations, and a go-to-market motion that doesn’t assume year-long rollouts. It’s a strategic stretch, but it’s also one of the few levers that can materially broaden the customer base without relying solely on taking share at the very top.

On M&A, Sana tells you Workday is willing to pay up for AI. That can work—but only with ruthless integration discipline. The next targets should be chosen less for buzz and more for platform fit: AI-driven workforce planning, real-time financial intelligence, or employee experience layers that naturally attach to Workday’s systems of record. The goal is to pull capabilities into the core so they compound across the suite, not to collect disconnected products that consume attention and dilute the roadmap.

Zooming out, the long-term vision is pretty clear. In the future enterprise, AI agents do the routine work—processing invoices, scheduling interviews, drafting reports, flagging compliance risks—so people can spend more time on judgment, creativity, and relationships. If Workday can make that future feel real, safe, and governable inside the largest organizations in the world, the next decade could be as consequential as the last.

Workday was born out of the wreckage of a hostile takeover and already rewrote the rules of enterprise software once. The only question left is whether it can pull off the same kind of reinvention again—this time with AI as the platform shift.

Recent News

Workday’s fiscal 2026 has looked less like a reinvention and more like steady, disciplined execution. Through the first three quarters, revenue was about $7 billion, with subscription revenue up 14 percent. Management nudged up full-year subscription guidance to $8.82 billion, lifted its non-GAAP operating margin target to 29 percent, and projected free cash flow of $2.65 billion—signals that Workday is leaning harder into operating leverage as the business matures.

At the same time, the company has been trying to put real speed behind its AI story. In May 2025, Workday introduced seven new Illuminate agents—aimed at areas like contract intelligence, contingent workforce sourcing, and automating pieces of accounting. Then, at Workday Rising in September 2025, it rolled out another set of agents for performance management, the financial close, and workforce planning. That announcement was paired with its biggest AI bet yet, the $1.1 billion Sana Labs acquisition, plus new partnerships with Databricks, Salesforce, and Snowflake as part of the Workday Data Cloud initiative.

Leadership-wise, the handoff has stayed calm. Carl Eschenbach entered 2026 with two years under his belt as sole CEO, with Aneel Bhusri in the executive chair role. There haven’t been headline-grabbing departures or abrupt strategy shifts—the kind of noise that can make enterprise customers nervous.

In the market, though, investors have been harder to convince. The stock traded around $210 in early 2026, about 30 percent below its February 2024 peak of $307. Goldman Sachs downgraded Workday to Neutral in January 2026, pointing to a crowded HCM market and what it saw as a slower ramp in AI monetization. Analysts’ consensus target of $278 suggested there was room to run—but sentiment stayed cautious, waiting for proof that AI isn’t just product announcements, but a growth lever that shows up in renewals, expansions, and bookings.

Then there’s the wildcard: Elliott Management. In September 2025, Elliott disclosed a stake of nearly 4 percent—right around the Sana Labs announcement. Elliott’s playbook in enterprise software is well known: push for tighter operations and more shareholder-friendly capital allocation. Its presence adds a new pressure point inside the Workday story, and it could accelerate moves toward margin expansion or changes in how Workday returns capital.

Links and Resources

- Workday Investor Relations and SEC filings: investor.workday.com

- Workday Newsroom (product announcements and press releases): newsroom.workday.com

- Stanford Graduate School of Business case study on Oracle’s hostile takeover of PeopleSoft

- Harvard Law School case study: Oracle v. PeopleSoft (David Millstone, Guhan Subramanian)

- The Register: “20 Years Since Oracle Bought Two Software Rivals in One” (January 2025)

- Josh Bersin: “Workday Acquires Sana to Transform Its Learning Platform” (September 2025)

- Workday Rising 2025 keynote and product announcements

- Futurum Group analysis of Workday Illuminate agents and the Sana acquisition

- Gartner and Forrester reports on the cloud ERP market

- Workday developer resources and API documentation: developer.workday.com

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music