Waystar Holding Corp: The Story of America's Healthcare Payment Infrastructure

I. Introduction: The Invisible Backbone

Picture a hospital billing department somewhere in suburban America. It’s 1995. Fluorescent lights buzz over rows of metal desks. Paper is everywhere—manila envelopes packed with diagnostic codes, procedure lists, and patient information.

A billing specialist picks up the phone, calls an insurance company, waits on hold for nearly an hour, and finally learns the problem: one transposed digit in a procedure code. The claim is denied. The whole thing goes back to the top of the stack.

Now jump forward almost three decades. In 2023, U.S. healthcare spending rose 7.5 percent to $4.9 trillion—about $14,570 per person. That’s 17.6 percent of GDP. And every dollar in that ocean of money still has to move: from patient to provider, from insurer to hospital, through a maze of codes, authorizations, eligibility checks, contract terms, and reimbursement rules.

At the center of that maze—mostly invisible to patients, but essential to the system functioning at all—is Waystar Holding Corp.

Waystar sells mission-critical cloud software that helps healthcare organizations get paid. Its platform stitches together the messy, fragmented steps providers have to complete to bill correctly and collect what they’re owed—while also trying to make the payment experience less painful for providers, patients, and payers. Under the hood, it uses internally developed AI and proprietary algorithms to automate the workflows that used to eat up entire teams.

The scale is hard to wrap your head around. Waystar serves about 30,000 clients, representing more than 1 million healthcare providers. It processes over 5 billion healthcare payment transactions a year, including more than $1.2 trillion in annual gross claims across roughly half of U.S. patients.

Pause on that: about half the country’s medical claims touch Waystar’s rails somewhere along the way. When your doctor’s office checks whether you’re covered, when a hospital submits a claim, when a provider figures out what you’ll owe—there’s a very real chance Waystar is the quiet software making that transaction happen.

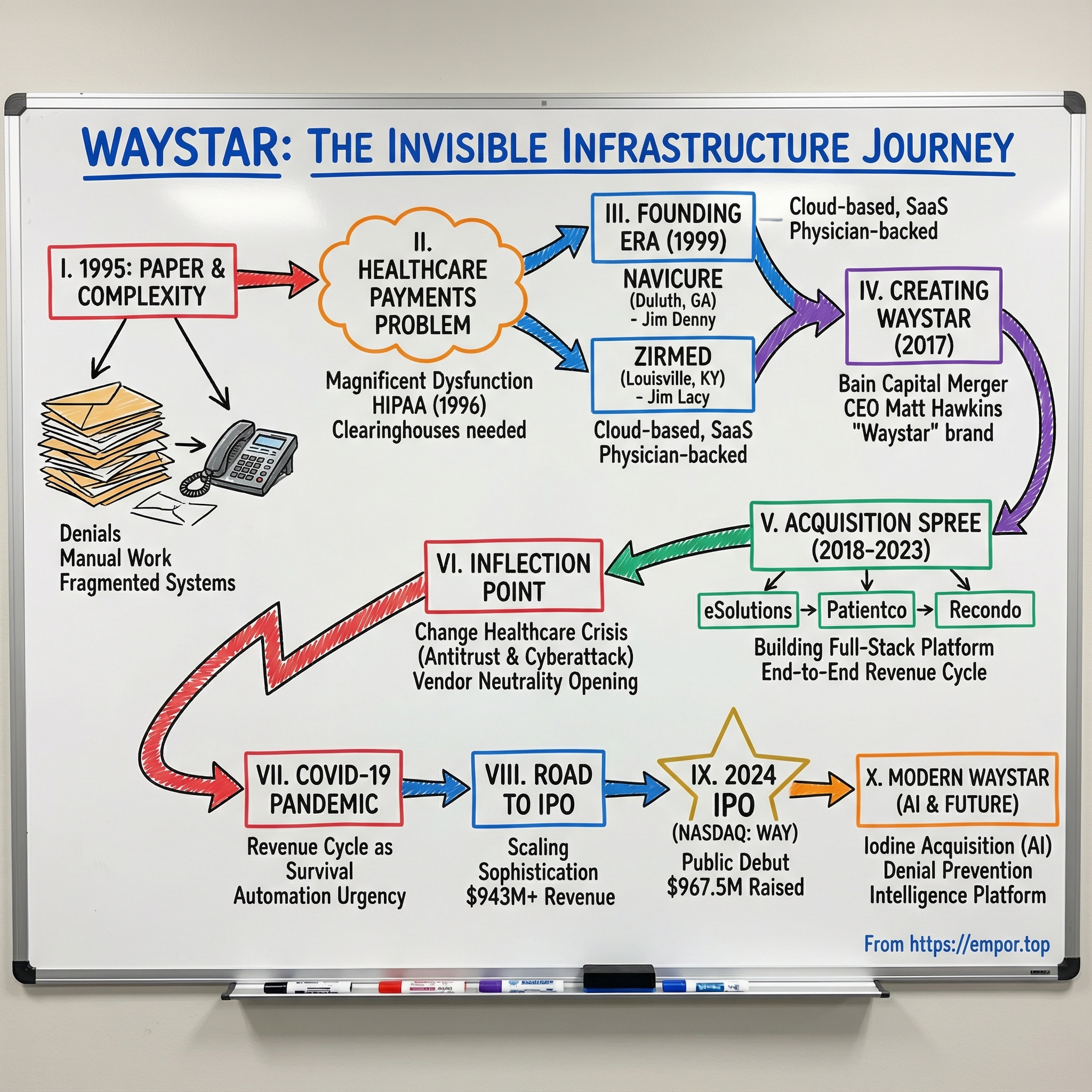

This is how a Louisville software company and an Atlanta healthcare tech firm combined into what became a key piece of America’s healthcare payment infrastructure. It’s a story about consolidation done well, about a competitor’s antitrust crisis creating an opening, about a pandemic that turned revenue cycle into survival, and about selling AI not as hype—but as the next lever in a brutally complex system.

It’s also a story about one of the least glamorous, most essential, and most defensible business models in American tech.

Welcome to the pickaxe business of the healthcare gold rush.

II. The Healthcare Payments Problem: Complexity as a Feature

To understand why Waystar exists, you first have to understand the magnificent dysfunction of American healthcare billing.

One analysis put it bluntly: the U.S. spends about $1 trillion—roughly 22% of total healthcare spend—on administration. In theory, that could be streamlined. In practice, the incentives don’t line up. The federal government only accounts for a relatively small slice of that spend, while the rest is spread across payers, providers, hospitals, and physician groups—each with their own systems, priorities, and politics.

Now zoom in to a single, ordinary doctor visit.

Before you ever sit on the exam table, someone has to confirm your insurance is active, figure out what your plan covers, and estimate what you’ll owe. During the visit, everything that happens gets translated into codes: ICD-10 for diagnoses, CPT for procedures. After the visit, a claim is created, checked for errors, sent to the insurer, tracked, and often corrected and resent. If the claim is denied, it may trigger an appeal. When payment finally arrives, it has to be matched against contracts and expected reimbursement. And if there’s a remaining balance, a patient statement gets generated and collected—hopefully without turning into a months-long customer service saga.

Every handoff is a chance for something to break. A missing modifier. An outdated insurance record. A payer policy change that didn’t make it into the billing team’s playbook. And when something breaks, it’s not just annoying—it’s expensive.

A 2024 survey of hospitals, health systems, and post-acute providers by Premier Inc. found that nearly 15% of medical claims submitted to private payers were initially denied. Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care plans were even higher, at 15.7% and 16.7%.

Providers say the trend is moving in the wrong direction. In 2022, 42% of healthcare organizations reported denials were increasing. By 2024, that number had jumped to 77%. More than that, they weren’t just seeing more denials—they were waiting longer to get paid. The Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy has pegged the burden of denied claims at around $260 billion annually.

This mess didn’t happen by accident. It’s the result of decades of regulation layered on regulation, payer-provider negotiations that never fully standardize, and technology built as patchwork—one workaround on top of the last.

HIPAA is a good example of how even the “fixes” can create new infrastructure. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 included administrative simplification provisions that required HHS to set standards for electronic exchange, privacy, and security of health information. The goal was straightforward: make healthcare transactions more standardized and more electronic.

The reality before HIPAA was chaos. Many entities had already moved toward electronic data interchange—but in their own proprietary formats. At the time, there were roughly 400 different formats for electronic health claims in use across the U.S. That kind of fragmentation made software hard to build, expensive to maintain, and nearly impossible to scale.

Standardization helped—but it also created a new, essential role in the ecosystem: the clearinghouse. Clearinghouses translate between nonstandard and standard formats, check for errors, and help claims comply with the rules so they can actually be processed. They sit between providers and payers, quietly making sure the plumbing holds.

And here’s what HIPAA’s architects likely didn’t predict: once a clearinghouse is embedded in the workflow, it becomes incredibly hard to replace. Providers connect it to their EHR, train their staff around it, build reporting and processes around its quirks, and rely on it day after day. Switching isn’t just a vendor decision—it’s operational risk.

That stickiness is why this market exists at all. In healthcare payments, complexity isn’t an accident. It’s the environment. Every new regulation adds steps. Every new insurance product adds edge cases. Every provider merger adds another set of systems to reconcile. And every added layer increases the value of software that can navigate the maze.

This is the landscape ZirMed and Navicure were born into—and the problem Waystar would eventually turn into a platform.

III. The Founding Era: Two Companies, Two Cities

The late 1990s were a hinge moment for healthcare billing. The internet was starting to seep into every industry. HIPAA was pushing the system toward standardized electronic transactions. And across the country, entrepreneurs looked at healthcare’s paper-choked back offices and saw something rare: a problem big enough to build a real company around.

Waystar’s story begins with two of those companies—born the same year, in two different cities, solving the same maddening problem from slightly different starting points.

Navicure traces back to 1999 in Duluth, Georgia, founded by Jim Denny as a clearinghouse for medical claims processing. ZirMed was also established in 1999, in Louisville, Kentucky, founded by Jim Lacy with a focus on revenue cycle solutions. Over the next decade and a half, both would grow—partly organically, partly through acquisitions—until they were meaningful names in healthcare payments long before anyone combined them into Waystar.

The insight behind both businesses was simple: providers were drowning in administrative complexity, and they would pay for software that helped them breathe.

Jim Denny came into the opportunity with a frontline view of what “scale” actually looked like in healthcare transactions. From 1995 to 2000, he held senior management roles at NDCHealth’s Provider Healthcare Transaction Group, where he ran a unit supporting 30,000 providers and processing more than 70 million transactions a year. During his six-year tenure, he led that group to profitability for the first time in its history.

So when Denny founded Navicure in 2000 and became its Chairman, CEO, and President, he wasn’t guessing. He’d watched the machine from the inside—how slow it was, where it broke, and what it would take to make it reliable. That operational discipline, paired with a strong service mindset, became core to how Navicure competed.

ZirMed’s early story had a different flavor—more grassroots, closer to the provider community. In 1999, Louisville physician Dr. Robbins became an early investor in ZirMed and recruited other physicians to invest alongside him. Those were people who didn’t just understand the billing problem intellectually—they lived it. That physician-backed credibility mattered in a market where trust is everything.

A decade later, ZirMed added a very different kind of validation: it partnered with Sequoia Capital in 2009. Sequoia’s involvement signaled that ZirMed wasn’t just a regional healthcare IT vendor—it had a technology approach and growth trajectory that could support something bigger.

Both companies also made a technology bet that looks obvious now, but wasn’t then: they built for the cloud before “cloud” was a default assumption. While many healthcare IT vendors still sold on-premise systems with heavy implementations, Navicure and ZirMed leaned into software delivered over the internet—closer to a subscription relationship than a one-time install.

By the mid-2010s, the results were showing up in the numbers and the reputation.

Navicure recorded its thirteenth straight year of double-digit revenue growth in 2014, finishing the year with $73.8 million in GAAP revenue. Based in Duluth, it positioned itself as a platform that helped providers and other healthcare organizations increase revenue, accelerate cash flow, and reduce costs across claims and patient payments. Navicure pointed to a stronger product portfolio, high retention, and the launch of Navicure Payments as drivers—and it saw momentum inside its own base, with upsell bookings up 17 percent over 2013.

It also earned external credibility. Navicure finished among the top three clearinghouses in KLAS Research rankings for the seventh straight year, in a field of more than a dozen. Client retention in 2014 was 96 percent—right in line with its average over the previous 14 years.

That kind of retention, sustained that long, is the tell. It’s not just that customers were satisfied. It’s that once Navicure was woven into the workflow, ripping it out was risky. Billing isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s how providers keep the lights on.

ZirMed was earning a similar kind of loyalty. In 2017, ZirMed Inc. was ranked #1 by its users for the seventh consecutive year in the Black Book Rankings user survey—another signal that it had locked in product-market fit where it mattered most: with the people actually doing the work.

And that’s the key lesson from this era. Healthcare payments software isn’t primarily a technology sale. It’s a trust sale. Providers are handing over the machinery that turns clinical care into cash. If the claims don’t go out correctly, they don’t get paid. If denials aren’t managed, revenue leaks. For smaller practices running on thin margins, vendor failure isn’t inconvenient—it can be existential.

By the mid-2010s, Navicure and ZirMed were both top-tier clearinghouse players. But the industry was consolidating fast, and “best-in-class” was no longer enough. The real question was scale: who could become big enough—and broad enough—to compete as healthcare payments infrastructure consolidated into a few platforms.

Private equity had the answer.

IV. The Roll-Up Begins: Creating Waystar

By the mid-2010s, the path private equity wanted to run in healthcare payments was pretty clear: take strong-but-still-fragmented players, combine them into something national, unlock scale economics, then use that platform to keep buying.

The Navicure–ZirMed deal followed that script. What made it different was that it was treated less like a financial engineering exercise and more like a build-the-company-for-real integration.

Navicure’s founder, Jim Denny, framed the moment as the continuation of what he’d been building for years: SaaS tools that helped “thousands of healthcare organizations from large health systems to solo practices improve their financial results with less effort.” Bain Capital echoed the same thesis from the investor side. Chris Gordon, a Managing Director on Bain Capital Private Equity’s healthcare team, said Denny and his team were “at the forefront of developing innovative solutions” for a reimbursement system that was only getting more complex.

Bain made the first move in 2016, acquiring Navicure. Then, in late 2017, it brought the other half of the combination into place: Bain acquired ZirMed and merged it with Duluth, Georgia-based Navicure in a deal valued at $750 million. In November 2017, the new company launched under a new name: Waystar.

Calling it a merger understates what it demanded. This wasn’t two spreadsheets being added together. It meant integrating two technology stacks, two product interfaces, two customer bases, and two company cultures—without breaking the thing customers depended on to get paid.

That’s why CEO selection mattered so much. Bain partnered with Matt Hawkins to lead the new Waystar. Hawkins came in with a resume that was basically a guidebook for this exact situation: President of Sunquest Information Systems, where he led growth acquisitions and a transformation into a global lab informatics player; before that, operating roles under Vista Equity Partners at Greenway Health, Vitera Healthcare Solutions, and SirsiDynix; and earlier, McKinsey & Company. He held a BS from Brigham Young University and an MBA from Harvard Business School.

More important than the pedigree was the fit. Hawkins brought healthcare software context plus the private-equity operator’s muscle memory: integrate acquisitions, tighten operations, and build toward a credible exit—without losing the customer trust the business runs on.

Bain wasn’t shy about leaning in. Over the course of the integration, it supported management across the usual high-leverage functions—M&A integration, product innovation, channel strategy, and digital marketing—and it emphasized partnership with Denny, who had spent 15 years building Navicure and wanted a buyer with a track record of growing alongside entrepreneurs.

Even the branding decision signaled how they wanted this to work. The company could have kept either legacy name. It chose neither. Hawkins said they considered doing business as ZirMed or Navicure, but “it just didn’t seem right to put one over the other… We thought, let’s create something new and special.” The name Waystar was a line in the sand: this wasn’t one company absorbing another; it was supposed to be a new platform.

Hawkins pitched that platform in end-to-end terms: “a unique position to provide an end-to-end, cloud-based revenue cycle technology platform… preventing problems, streamlining processes, and removing friction in the revenue cycle process.” On day one, the combined business had immediate scale—supporting more than 400,000 providers across hospitals, health systems, and ambulatory organizations, and partnering with leading EHR and practice management vendors. Both legacy companies also arrived with serious credibility, having consistently earned industry recognition, including Best in KLAS awards as top-rated clearinghouse and claims management vendors nationally since 2010.

But scale wasn’t the whole point. The bet was that the value would come from real integration. Not just combining sales teams and cutting redundant overhead, but consolidating the technology into something cleaner, broader, and easier to build on. Bain pushed for patience here: integrate first, rebuild where needed, then accelerate.

That restraint matters because it’s where a lot of roll-ups fail. Stapling companies together can create a bigger org chart, but it rarely creates a better product. Waystar’s early edge was that it aimed to become more than the sum of its parts.

Then came the external validation. In 2019, EQT Partners and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board acquired a majority equity stake in Waystar, valuing the company at $2.7 billion. Bain stayed involved alongside EQT and management for the next chapter.

Less than two years after Waystar’s formation, the message from the market was clear: this wasn’t just a merged clearinghouse. It was becoming durable infrastructure—and now it had the capital and backing to start building aggressively.

The stage was set for the acquisition spree that would turn Waystar from a newly combined company into a full-scale revenue cycle management platform.

V. The Acquisition Spree: Building the Full-Stack Platform

With the ZirMed–Navicure merger complete and fresh capital behind it, Waystar moved into the next phase of the playbook: widen the product surface area, fill the obvious gaps, and turn a great clearinghouse into a platform that could sit across the entire revenue cycle.

Between 2018 and 2023, Waystar executed a steady run of acquisitions. The pattern was consistent: buy a capability it didn’t have, integrate it into the core workflow, then sell it across a customer base that already trusted Waystar with the most mission-critical job of all—getting paid.

By the time it announced its eighth acquisition since 2018, Waystar had already added key pieces like Recondo, eSolutions, and Patientco. The point wasn’t deal volume for its own sake. It was progress toward a simpler, more unified way to move healthcare money.

The most strategically important of the bunch was eSolutions, which Waystar agreed to acquire in 2020. eSolutions brought something Waystar couldn’t easily build overnight: deep Medicare-specific connectivity and expertise. The deal mattered because it helped Waystar unify two worlds providers were used to treating separately—commercial claims on one side, government payers on the other—into a single platform. eSolutions, founded in 1999, had built technology to maximize collections, accelerate cash flow, and reduce administrative burden across many sites of care, with thousands of payer connections and a growing dataset spanning billions of transactions.

That Medicare angle wasn’t a niche add-on. Medicare was already the largest payer in the U.S., and as the baby boomer population aged, more and more provider revenue flowed through Medicare rules, Medicare edits, and Medicare quirks. Historically, providers often had to run commercial and Medicare workflows through different systems. Bringing both under one roof didn’t just reduce vendor count—it reduced the operational friction of managing two parallel billing universes.

Recondo added a different lever: analytics and automation where the pain is loudest. Patient estimation and prior authorization are two of the most frustrating, labor-intensive choke points in revenue cycle. Recondo’s tools helped Waystar reach earlier in the process—before the claim even exists—to prevent avoidable problems that turn into denials and delayed payment later.

Then came Patientco, which pushed Waystar into the patient-facing part of the equation. Waystar agreed to acquire Patientco, a provider of omnichannel patient payments, communications, and engagement software, with the goal of improving how patients receive bills, understand them, and pay them. The logic was straightforward: as the industry shifted toward high-deductible plans, patients became a much bigger “payer.” Providers weren’t just fighting denials from insurers—they were trying to collect meaningful dollars from consumers, without destroying the relationship in the process.

Waystar acquired Patientco for $450 million.

The bigger strategy snapped into focus here. Many vendors chose a side: patient access, or claims, or reimbursement. Waystar wanted to cover both. Combining Patientco’s payments and engagement tools with Waystar’s financial clearance capabilities, AI, and claims data allowed Waystar to offer a more consumer-friendly billing experience while also making it easier for providers to quote, collect, and reconcile payments before and after care.

Patientco wasn’t the only bolt-on. Waystar also acquired Connance, which brought predictive analytics for workflows like propensity to pay and presumptive charity. Together with eSolutions and Recondo, these weren’t random assets—they were pieces of a single story: prevent problems upstream, move claims cleanly through the middle, and make payment downstream less painful.

Every acquisition followed the same integration logic: identify a segment where Waystar was missing a key capability, buy a leader in that niche, fold the product into a unified platform, and use Waystar’s distribution to scale it.

EQT, now Waystar’s majority owner, framed the deal-making as mission-driven. “Our investor group has significant financial resources, which enables us to support the Waystar team in pursuing strategic deals of this nature,” said Eric Liu, Partner and Global Co-Head of Healthcare at EQT. “We are delighted with this combination as it advances Waystar's mission to simplify healthcare payments.”

The economics reinforced why this worked. Waystar’s model blended subscription revenue with volume-based transactions, which gave it both recurring stability and a natural tailwind as customers processed more claims over time. It reported gross revenue retention of 90%, and net revenue retention—meaning the same customers spending more through cross-sell and upsell—of 109%. Put simply: Waystar wasn’t just keeping customers. It was expanding inside them.

By 2023, the company had stitched together what it called an end-to-end revenue cycle platform spanning patient access, charge capture, claims management, denials prevention and recovery, patient payments, and analytics. Waystar started life as a clearinghouse. It was now something much harder to displace: a system woven through the entire process of turning care into cash.

And for investors watching from the sidelines, that acquisition track record told them three things that would matter later: Waystar could source the right deals, integrate them without breaking the core engine, and build a platform with a coherent strategy—not just a pile of products.

VI. The Inflection Point: Change Healthcare's Antitrust Crisis

Sometimes the most important chapter in a company’s story is written by someone else. For Waystar, that chapter began when the U.S. Department of Justice took aim at UnitedHealth Group’s attempt to buy Change Healthcare.

In February 2022, the DOJ—joined by the attorneys general of New York and Minnesota—filed suit in federal court in Washington, D.C., to block what it described as a roughly $13 billion deal. The argument wasn’t subtle: letting the country’s largest health insurer buy one of the most important pipes in healthcare payments would squeeze competition and concentrate power in a market that already wasn’t exactly known for abundance of choice.

To see why regulators cared, you have to understand what Change Healthcare was. It operated the nation’s largest EDI clearinghouse. Clearinghouses are the translation layer of U.S. healthcare: they help get claims from providers to payers, and they help get approvals, denials, and payment information back the other way. They’re not the flashy part of healthcare. They’re the part that makes the whole machine run.

The government’s case centered on vertical integration. If UnitedHealth owned a core clearinghouse, critics worried it could gain access to competitively sensitive data and tilt the playing field—subtly or otherwise—in favor of its own interests. Industry groups piled on. The American Hospital Association, for example, praised the DOJ for stepping in and warned that the merger could create a “massive consolidation of competitively sensitive health care data” under UnitedHealth’s control, potentially distorting decisions about claims processing and denials to the detriment of providers and patients.

In the end, the challenge didn’t stop the deal. In September 2022, the court ruled in favor of the merger and rejected the antitrust arguments. It also ordered Change Healthcare to divest its claims editing business, ClaimsXten, to TPG Capital for $2.2 billion. Shortly after that ruling, the acquisition closed in early October 2022. (The transaction was reported as $7.8 billion at closing, reflecting deal structure and adjustments, even though it was often described as a much larger headline figure during the process.)

But even though the DOJ lost in court, the fight created something that mattered just as much: doubt.

Hospital systems and health plans that had long treated Change as neutral infrastructure started asking uncomfortable questions. Would a competitor’s parent company now sit closer to their claims data? Would product priorities drift toward UnitedHealth’s ecosystem? And if your business depends on getting paid, do you really want the rails owned by the biggest insurer in the country?

That uncertainty was oxygen for Waystar.

Waystar didn’t have to pick a fight. It just had to stand still and be clearly different. It was not owned by an insurer. It could credibly say its incentives were aligned with providers, not with a payer that also competed across care delivery through Optum. For large health systems in particular, that “independent” positioning wasn’t marketing fluff. It was risk management.

This is where the market began to reshuffle. The customer wins weren’t all disclosed publicly, but the broader pattern was visible: the antitrust saga made “vendor neutrality” a board-level conversation, and Waystar was one of the few scaled options that could plausibly take on displaced demand. It was the kind of opening that comes along rarely—a competitor’s stumble that changes buying behavior for years.

Then, in February 2024, those dynamics got supercharged.

A cyberattack hit Change Healthcare and disrupted healthcare operations on a national scale. It interfered with clinical and eligibility workflows, slowed authorizations, and created enormous financial stress for providers waiting on payments. Change Healthcare—now a UnitedHealth subsidiary—was described as the predominant source of more than 100 critical functions that keep the U.S. healthcare system operating. It processes around 15 billion transactions a year, touching 1 in 3 patient records, including eligibility verification, authorizations, prescriptions, claims transmission, and payments.

The breach’s human impact was staggering too. About eight months after the attack, Change confirmed that protected health information for at least 100 million people had been compromised—nearly a third of the U.S. population—making it the largest known breach of protected health information at a HIPAA-regulated entity.

Hospitals felt it immediately. In a March 2024 AHA survey of nearly 1,000 hospitals, 74% reported an impact on direct patient care, including delays in authorizations for medically necessary care. Ninety-four percent said the attack hit them financially, and a third said it disrupted more than half of their revenue. Many said it took weeks to months to resume normal operations after full functionality returned.

UnitedHealth later reported the cost of the ransomware attack had risen to $2.457 billion in its Q3 2024 earnings report.

For providers already uneasy about concentration risk, the cyberattack turned a theoretical concern into a lived experience. Depending heavily on a single clearinghouse had proven not just inefficient, but dangerous. Diversification stopped looking like a strategic preference and started looking like operational insurance.

Waystar didn’t need to say much publicly. The market said it for them. Providers looking for alternatives found a scaled, well-reviewed platform that wasn’t owned by a payer. Whether through active sales motions or inbound urgency from customers spooked by what they’d just lived through, Waystar benefited from the chaos engulfing its largest competitor.

And once again, the invisible infrastructure business proved its point: when the payment plumbing breaks, nothing else works.

VII. COVID-19 and the Healthcare Payment Meltdown

The COVID-19 pandemic didn’t just test hospitals clinically. It tested the financial engine that kept them open.

In March 2020, as the virus spread across America, providers ran into a brutal paradox: ICUs were filling with COVID patients, while operating rooms and clinics went quiet. Elective procedures—the work that typically pays the bills—were canceled almost overnight. In many service lines, patient volumes fell off a cliff, sometimes by half or more.

For revenue cycle, this wasn’t a “tighten the belt” moment. It was an existential one. Hospitals that already lived on thin margins suddenly faced a world where the care they were delivering didn’t come with predictable reimbursement, and the care that did come with predictable reimbursement wasn’t happening. Cash reserves shrank fast. Without help, some organizations were staring down the possibility of closure.

In normal times, revenue cycle management can feel like back-office plumbing. In 2020, it became survival strategy. Every denied claim that could be recovered, every eligibility check that could prevent billing errors, every payment that could be pulled forward from a slow payer—those weren’t operational details anymore. They were lifelines.

Waystar’s response reflected the speed of the crisis and the value of having infrastructure already in place. Providers needed to bill for scenarios that barely existed weeks earlier. Telehealth visits had to be coded correctly. COVID-related claims came with their own requirements. Government relief programs, including the Provider Relief Fund, created new documentation and compliance work that had to be tracked and done right.

At the same time, the pandemic made the case for automation in a way no sales pitch ever could. Manual, human-heavy processes were suddenly fragile. Billing teams were dealing with staff shortages and burnout, not just complexity. The question shifted from “Should we modernize?” to “How do we keep this running with fewer people and more chaos?”

Waystar’s business model helped it absorb the shock. As utilization fell, volume-based revenue declined too. But subscription revenue provided a stabilizing base. With a mix that was roughly half subscription and half volume-based, Waystar had a built-in hedge: more resilience on the way down, participation in the upside as volumes returned.

When the worst of the disruption passed, the lesson stuck. Providers that survived 2020 didn’t want to be that exposed again. The market came out of the pandemic more digitized, more automation-hungry, and more focused on squeezing friction out of revenue capture—exactly where Waystar’s platform sat.

COVID didn’t invent Waystar’s opportunity. It turned the company’s thesis into urgency: healthcare payments were too essential, too complex, and too labor-intensive to run on brittle workflows and heroic effort.

VIII. The Road to IPO: Scaling and Sophistication

By 2023, Waystar had assembled the ingredients Wall Street wants to see before it blesses a new public company: real scale, real growth, and a business that could tell a credible story about the next decade—not just the last one.

The financial profile had changed dramatically since the 2017 merger. In 2024, Waystar generated $943.55 million in revenue, up 19.28% from $791.01 million the year before. That kind of growth, at that size, is the difference between “interesting” and “institutional.”

At the same time, the customer base was moving upmarket. The largest hospital systems—the top 500 by revenue—aren’t just bigger logos. They’re harder buyers. They demand enterprise-grade security, strict uptime expectations, dedicated support, and the ability to push massive transaction volumes through the platform without drama. Winning those accounts meant Waystar had to mature from a high-performing healthcare IT vendor into something closer to a utility: trusted, audited, always-on.

But the most important shift wasn’t just operational. It was identity.

Waystar began life as a clearinghouse—the translator sitting between providers and payers. Over time, it became a broader revenue cycle management platform. Heading into IPO mode, management pushed the story one step further: Waystar wasn’t just moving transactions. It was becoming an AI and data company built on top of those transactions.

The data advantage wasn’t theoretical. Processing billions of transactions every year creates a feedback loop no early-stage competitor can fake. Every claim submission and payment, every denial and appeal, becomes training material for algorithms designed to predict what will happen next—which claims are likely to be rejected, which payers tend to slow-walk reimbursements, which patient balances are likely to be collected.

Waystar also argued it was operating with a more modern technology foundation than many incumbents. A big slice of the competitive set runs on older systems that can be expensive to connect and painful to change. Waystar’s newer stack helped keep integration work more manageable while leaving the switching costs high once a customer was live—because billing workflows don’t forgive downtime or broken connections.

That fed into an even bigger strategic reframing: moving from charging for transactions to charging for outcomes. A pure clearinghouse business gets paid per claim processed, which can start to feel like a utility with limited pricing power. But a platform that can measurably reduce denials, accelerate cash flow, and improve provider margins can justify premium pricing because it’s selling ROI, not throughput.

And that narrative mattered. Public markets tend to reward “platform plus analytics” companies differently than “transaction plumbing” companies. The underlying work can look similar on the surface, but the valuation logic isn’t.

Behind the scenes, Waystar also had to become public-company ready in all the unglamorous ways. The board added independent directors with public market experience. Governance got tighter. Executive compensation shifted toward long-term equity incentives.

EQT and Bain Capital knew this transition well. As seasoned private equity sponsors, they’d run the IPO playbook many times: professionalize the organization, sharpen the metrics and disclosures, and make sure the company can live on a quarterly cadence without losing the long-term thread.

By late 2023, the question wasn’t whether Waystar could go public. It was when the window would open wide enough to make the leap.

IX. The 2024 IPO and Public Market Debut

By early 2024, the IPO market that had been mostly frozen since 2021 finally started to thaw. Interest rates were still higher than the last decade’s norm, but volatility was easing, investors were getting selective again, and the public markets were once more willing to listen to a business with real scale and a clear story.

Waystar chose its moment.

On June 6, 2024, Waystar Holding Corp. priced its initial public offering: 45,000,000 shares at $21.50 per share. The stock began trading the next day, June 7, on the Nasdaq Global Select Market under the symbol “WAY,” and the offering closed on June 10.

At that pricing, the deal raised roughly $967.5 million in gross proceeds—one of the larger and more closely watched IPOs of the year. J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC, and Barclays led the offering as joint lead book-running managers.

The investor roster signaled confidence. Waystar drew meaningful institutional demand, including interest from cornerstone investors such as funds and accounts managed by Neuberger Berman Investment Advisers LLC and a subsidiary of the Qatar Investment Authority, collectively indicating interest in buying up to $225.0 million of stock at the IPO price.

The first day had a small bit of drama. Waystar priced at $21.50, but opened trading at $21. Around the same time, the company was pointing investors to its momentum: for the quarter ending March 31, it reported $224.8 million in revenue, up 18% from the prior year.

CEO Matt Hawkins framed the logic of going public in plain terms. On CNBC, he said Waystar was excited about the move because it would increase awareness and credibility, improve the company’s capital structure, and support continued investment—especially in areas like generative AI.

The use of proceeds underscored the private-equity playbook behind the curtain. Waystar said it intended to use the net proceeds to repay outstanding indebtedness. Paying down debt didn’t just clean up the balance sheet; it created more flexibility for future acquisitions—important for a company that had grown by building, buying, and then cross-selling into a trusted customer base.

For Bain Capital, the IPO marked a successful exit. For EQT, it was a partial exit—while both sponsors kept meaningful ownership stakes. That detail mattered to public investors: it suggested the people who knew the business best were still along for the ride.

And then came the real transition. As a public company, Waystar entered a new operating rhythm: quarterly earnings calls, analyst questions, SEC disclosures, and constant comparison to peers. The upside was equally real—greater visibility, broader access to capital, and a public stock that could become acquisition currency.

The next test was simple, and unforgiving: could Waystar perform quarter after quarter like the durable infrastructure business it had been pitching in its S-1?

X. The Modern Waystar: AI, Automation, and the Next Decade

Since the IPO, Waystar has been doing what newly public infrastructure companies are supposed to do: keep growing, keep compounding, and keep making the case that the “plumbing” is really an automation and intelligence platform.

By the third quarter of 2025, that story was showing up in the results. Waystar reported revenue up 12% year over year, net income of $30.6 million (and non-GAAP net income of $67.8 million), and profitability that looked more like a mature software company than a transaction processor—an 11% net income margin and a 42% adjusted EBITDA margin. Management also raised its 2025 guidance for both revenue and adjusted EBITDA.

Underneath the headline numbers, you can see the engine working the way Waystar wants it to. Net revenue retention came in at 113%, a sign that existing customers were buying more, not less. Subscription revenue grew 14%, while volume-based revenue grew 10%—a healthy mix that keeps the model resilient while still benefiting when claims and payments flow. And the customer base continued to “enterprise up.” In Q3, the number of clients generating more than $100,000 in trailing twelve-month revenue rose to 1,306, up 11% year over year.

Then came the biggest post-IPO swing: Iodine Software.

In July 2025, Waystar announced a definitive agreement to acquire 100% of Iodine Software from shareholders led by Advent International for a total enterprise value of $1.25 billion. Waystar positioned it as its largest deal since going public—and its most significant bet yet on AI. The pitch was clear: use Iodine’s capabilities to help prevent denials, reduce manual work, and improve provider financial performance, while also being immediately accretive to gross margin and adjusted EBITDA margin.

When the acquisition closed, Waystar framed the combination in data terms: pair one of healthcare’s largest financial datasets with one of the largest clinical datasets. Iodine brought more than 1,000 hospitals and health systems as clients, which Waystar said expanded its total addressable market by over 15% and created new cross-sell opportunities.

Strategically, Iodine plugged a specific hole. Waystar had long been strongest around the claim itself—clean submission, denial management, payment posting, patient payments. Iodine lives earlier, in what management described as the “mid-cycle”: the stretch between care delivery and claim submission where clinical documentation determines how the claim will be coded and whether it will be paid. Or put more bluntly: this is where money is won or quietly leaked before a claim ever leaves the building. “Iodine joining Waystar brings together comprehensive clinical and financial intelligence on a single AI-powered platform—a unique differentiator in the market,” said CEO Matt Hawkins.

With Iodine included, Waystar said the combined company processes more than 6 billion annual healthcare payment transactions, covering one-third of all inpatient discharge clinical encounters in the U.S., along with more than 160 million patient encounters and 1.5 billion medical concepts that drive AI-powered insights.

The next decade’s opportunity is basically a list of healthcare’s most hated workflows—ripe for automation.

Prior authorization is at the top of that list: a daily grind of forms, phone calls, and payer rules that creates delays and burns labor. Denials are another. About 41% of providers now face denial rates of at least 10%, and an analysis of more than 441 million claim remits shows denials trending upward, putting billions of dollars at risk each year.

Regulation, unusually, is also helping. CMS interoperability rules are pushing more data sharing between payers and providers, increasing the value of platforms that can aggregate and interpret that data. And price transparency requirements are forcing providers to give patients more accurate estimates before care—exactly the kind of workflow Waystar has been building through its patient estimation and financial clearance products.

For 2025, management guided to total revenue of $1.085 billion to $1.093 billion, with adjusted EBITDA of $451 million to $455 million.

After years of building the rails, then building the platform on top of the rails, Waystar’s next act is trying to make those rails smarter: fewer denials, less human labor, and faster, more predictable cash flow. In U.S. healthcare, that’s not just a feature. It’s the product.

XI. The Competitive Landscape and Market Dynamics

For all the chaos in healthcare billing, the vendor landscape is surprisingly concentrated. At the top end of revenue cycle management, it looks a lot like an oligopoly: a few scaled platforms running an enormous share of the nation’s claims and payments, with a long tail of niche vendors filling in gaps.

Waystar’s most direct heavyweight rival is Change Healthcare—now inside UnitedHealth Group’s Optum division—offering many of the same core services in claims and revenue cycle. UnitedHealth’s acquisition of Change in 2022 is what made the competitive picture feel different overnight. This wasn’t just one vendor buying another. It was the country’s largest insurer owning a major piece of the payment rails.

That ownership structure is the source of the industry’s awkward tension. For providers, Change Healthcare is no longer just a software company. It’s infrastructure controlled by an organization that may be on the other side of the negotiating table, and in some cases competing through Optum’s footprint in care delivery. So when a hospital or physician group chooses a clearinghouse or RCM partner, they’re not only weighing features and pricing. They’re also deciding how comfortable they are routing sensitive financial workflows through a platform owned by a payer.

Waystar’s positioning lives in that discomfort. It has historically been strongest in ambulatory, where it has about 9% market penetration, and it also competes in the hospital market, where its penetration is around 4%. It was formed from ZirMed and Navicure in 2017 and spent years under sponsor ownership—first Bain Capital, then EQT—building scale, broadening the platform, and getting “public-company clean.”

Zoom out, and the prize is massive. The revenue cycle management market is often estimated at roughly $130 billion. One way to triangulate that is to start with healthcare spend: CMS tracks total hospital and ambulatory expenditures, with long-range estimates around $1.5 trillion for hospitals and $1 trillion for ambulatory and other outpatient services. If revenue cycle management captures roughly 4% to 6% of those dollars, you land in the neighborhood of a $125 billion market.

That structure creates a push-pull for Waystar.

On one hand, a market dominated by a few scaled platforms can be rational. There are only so many buyers, switching is risky, and everyone understands that uptime and trust matter more than flashy product launches.

On the other hand, Optum’s vertical integration brings advantages that don’t show up in a typical feature checklist—especially the ability to pair RCM capabilities with insurance-side data and distribution. Waystar can’t replicate that ownership position, so it competes by being the credible independent alternative. Its pitch is simple: it doesn’t sell insurance, it doesn’t operate a payer, and it doesn’t have competing incentives. It only makes money when providers get paid, faster and more accurately.

The Change Healthcare cyberattack poured gasoline on that narrative. It exposed the operational risk of concentration and pushed diversification up the priority list. After living through a national disruption, many providers became more serious about redundancy—either running multiple clearinghouses or making sure they have viable backup capabilities. That shift doesn’t just benefit Waystar; it benefits independent players broadly. But Waystar is one of the few with enough scale to be a true second rail.

Competition is also creeping in from a different direction: fintech. Companies that already understand payments see healthcare as an adjacent opportunity, and JPMorgan’s acquisition of InstaMed put a well-capitalized player on the board. The catch is that healthcare payments aren’t “just payments.” They’re payments wrapped in eligibility, coding, payer rules, denials, and a web of connections that incumbents like Waystar have spent decades building.

In other words, the market may be huge—but the barriers are real. In healthcare revenue cycle, the winners aren’t the ones with the slickest checkout flow. They’re the ones providers trust to keep cash moving when everything else is going wrong.

XII. Playbook: Business and Strategic Lessons

Waystar’s rise from a regional Louisville software business to a publicly traded piece of healthcare infrastructure leaves a surprisingly clear set of lessons for operators and investors.

The first is that roll-ups only work when the product gets better. Plenty of private equity consolidations stop at the org chart: stitch together revenue, centralize costs, declare “synergies,” and move on. Waystar’s consolidation worked because Bain Capital and management put real effort into integration—actually unifying technology platforms, not just combining sales teams. That patience mattered. Rebuilding and rationalizing the tech stack is slower than a spreadsheet merger, but it’s what creates a platform customers will bet their cash flow on.

Second: network effects can exist in B2B, even if they’re not the viral kind. Waystar becomes more valuable as it connects more providers to more payers. More providers make it a more compelling integration target for payers. More payer connections make it more useful to providers. It’s not social media, but it does compound: more connectivity, more data, more reasons to standardize on the platform.

Third: Waystar won by showing up early to major transitions and staying positioned as they unfolded. HIPAA pushed claims from paper toward electronic standards. High-deductible plans made patients a bigger “payer,” pulling revenue cycle closer to consumer payments and engagement. And now AI is creating a new wedge—not as a shiny demo, but as a way to prevent denials, reduce manual work, and predict outcomes in a system built on exceptions.

Fourth: mission-critical beats “nice-to-have” almost every time. Providers can delay a CRM refresh. They can’t delay getting paid. Revenue cycle is infrastructure, and infrastructure businesses tend to be resilient through cycles because switching is risky and downtime is unacceptable. That’s where the stickiness comes from—not clever pricing, but operational necessity.

Finally, there’s an M&A lesson that’s easy to say and hard to execute: buy with intent. Waystar’s acquisition strategy wasn’t about collecting logos. It was about identifying capability gaps, acquiring leaders in those niches, integrating them into the workflow, and then scaling adoption through cross-sell. The deals had a job to do, and the platform got broader and more cohesive as a result.

For healthcare founders, the meta-lesson is almost counterintuitive: the biggest outcomes often come from infrastructure, not flashy front-end applications. If you can sit at a chokepoint—claims, eligibility, authorization, payments—and earn trust there, you don’t just build a feature. You build something the system quietly can’t function without.

XIII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

On paper, a clearinghouse or revenue cycle platform sounds like “just software.” In practice, it’s a long, bruising crawl through domain complexity. You need deep knowledge of payer rules, thousands of payer connections built over years, integrations into the major EHR systems, regulatory certifications, and—most importantly—trust earned by not breaking when a provider’s cash flow is on the line. New entrants can write code, but they can’t fast-forward a decade of payer relationships and operational credibility. HIPAA compliance, state-specific rules, and payer certification requirements raise the floor even higher.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Waystar’s main “suppliers” are engineering talent and cloud infrastructure. Great healthcare software engineers aren’t cheap, but Waystar’s scale and stability help it compete for them. And while it relies on hyperscalers like AWS, Azure, and GCP, cloud compute is largely a commodity. Neither input has the kind of chokehold that would let suppliers dictate terms.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

Buyer power is real because providers have consolidated. The biggest health systems are sophisticated procurement machines, and they negotiate hard. But they’re also constrained by reality: switching clearinghouses and RCM platforms is painful and risky. It means retraining staff, redesigning workflows, rebuilding integrations, and accepting the possibility of disrupted revenue in the middle of the changeover. Because revenue cycle is mission-critical, most providers are less interested in saving a little money than they are in avoiding a disaster.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-LOW

Providers can, in theory, build pieces of revenue cycle in-house. In reality, that’s expensive, difficult to maintain, and far from a core competency for clinical organizations. Some large provider-payer pairs also establish direct connections, but those don’t scale across the thousands of payer relationships an average health system needs. New approaches like blockchain-based healthcare payments get talked about, but they’re unproven in the real-world mess of U.S. reimbursement. Ironically, the system’s complexity acts like its own moat: meaningful simplification is what would enable substitutes, and that’s not a trend anyone is betting on.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM-HIGH

This is an oligopoly, and it behaves like one. Competition clusters around a small set of scaled players—Waystar, Change Healthcare under Optum, and other meaningful platforms like R1 RCM and Availity. Rivalry is intense, but it’s not pure price warfare, because differentiation matters: breadth of platform, reliability, service, and—especially post-Change acquisition—whether the vendor is independent from payer ownership. The wild card is Optum’s vertical integration with UnitedHealth, which creates advantages that a standalone software company can’t fully replicate and makes the competitive landscape inherently asymmetric.

XIV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG

Waystar runs an infrastructure business with heavy fixed costs: building the platform, maintaining thousands of payer connections, and meeting ever-rising security and compliance requirements. But once that machinery is in place, every additional claim and transaction pushes the unit cost down. At Waystar’s scale—processing more than $1.2 trillion in annual claims—smaller competitors simply can’t spread those costs nearly as efficiently.

Network Effects: MODERATE-STRONG

Waystar benefits from a very real, very practical two-sided network effect. The more providers that run through Waystar, the more attractive it becomes to payers because one connection reaches more of the market. And the more payer connections Waystar maintains, the more valuable it becomes to providers because coverage is broader and workflows are simpler.

There’s also a data flywheel layered on top: more transactions create more training data, which can improve AI-driven tools like denial prediction and revenue optimization. It’s not a pure social-network effect, but in healthcare payments, “more connected” and “more informed” compounds.

Counter-Positioning: HISTORICAL

Waystar’s early bet on cloud-based SaaS gave it an advantage over legacy on-premise vendors that couldn’t flip their delivery model quickly. That counter-positioning mattered during the transition years. Today, with cloud now table stakes, the advantage is less distinctive than it once was.

Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

This is the core of the moat. Waystar is deeply integrated into major EHR ecosystems like Epic, Cerner, and Meditech, which means it’s embedded directly in the workflows that determine whether a provider gets paid. Teams learn Waystar’s screens, reports, and operational routines. The organization builds processes around it.

Replacing a clearinghouse isn’t like swapping out a normal software tool. It can take months of implementation, parallel runs, testing, and risk-management planning—because the downside of a bad cutover isn’t inconvenience. It’s disrupted cash flow. Waystar’s 95%+ gross revenue retention is the real-world proof that these switching costs are not theoretical.

Branding: MODERATE

In healthcare IT, brands aren’t built through consumer advertising—they’re built through reputation, references, and reliability. Waystar’s strong performance in KLAS research and Black Book rankings gives it credibility with the committees that decide what runs the revenue cycle. That said, it’s not the kind of brand that wins deals on name alone; it amplifies a strong product rather than replacing it.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

Waystar’s dataset—fed by more than $1.2 trillion in annual claims—is a meaningful asset, especially as the company leans harder into AI. Its payer and EHR relationships are also difficult to replicate quickly. But this isn’t a patent-protected monopoly. A determined, well-capitalized competitor could assemble similar connections and data over time. It’s hard, but not impossible.

Process Power: MODERATE

Waystar has built repeatable muscle in areas that matter: integrating acquisitions without breaking the core engine, running customer success at high retention levels, and steadily extending the product. Those capabilities make the strategy work. They’re not the moat by themselves, but they’re the operating system that keeps the moat from eroding.

Summary: Waystar’s moat comes primarily from Switching Costs + Scale Economies + Network Effects. Together, they create serious barriers and a lot of inertia in Waystar’s favor. But it’s not untouchable—given enough time, capital, and commitment, a competitor could still mount a credible challenge.

XV. Bull vs. Bear Case and Investment Framework

Bull Case:

The simplest version of the bull case is that Waystar is wired into a part of healthcare that keeps getting bigger. As the population ages and medicine gets more expensive, more dollars flow through claims, eligibility checks, denials, and patient collections—and Waystar gets a chance to touch more of that traffic year after year.

Layer on industry structure, and the story gets even better. Revenue cycle is still consolidating, and Waystar has already proven it can buy the right capabilities, integrate them, and then scale them across an existing customer base. If that continues, Waystar doesn’t just grow with the market—it can take share as the market compresses into fewer, broader platforms.

The other major lever is the shift from transactions to intelligence. Claims processing is valuable, but it can start to look like a utility. Denial prediction, revenue optimization, and clinical documentation insights are a different category: higher margin, more differentiated, and easier to price around measurable outcomes. If AI and automation keep working their way deeper into provider workflows, Waystar’s total addressable market expands from “moving claims” to “improving cash flow.”

And then there’s the part public investors love most: predictability. A sticky customer base, plus net revenue retention above 100%, means a meaningful chunk of growth can come from customers already on the platform—buying more modules, expanding usage, and standardizing more workflows on Waystar over time. In a world of staffing shortages and margin pressure, the pitch isn’t luxury software. It’s automation that keeps the revenue engine from stalling.

Finally, patients are paying more of the bill than they used to, thanks to the spread of high-deductible plans. That turns patient payments into a larger and more important surface area for providers—and for Waystar. And if the system’s regulatory and reimbursement complexity keeps rising, it doesn’t hurt Waystar. It strengthens the value of software that navigates the maze.

Bear Case:

The bear case starts with the most asymmetric competitor in the space: Optum. UnitedHealth’s scale and vertical integration create options Waystar doesn’t have—bundling, aggressive pricing, and packaging RCM alongside other Optum services. Even if providers prefer an “independent” vendor in principle, that preference may weaken if budgets tighten and Optum can win on price.

There’s also a long-term disintermediation risk. If healthcare data exchange becomes more standardized and payers and providers connect more directly, the clearinghouse layer could matter less. Even without full disintermediation, the core clearinghouse function can face commoditization pressure over time, which would push Waystar to prove that its platform and analytics are the real product—not just the pipes.

Macro risk matters too. A downturn can slow hospital purchasing decisions, delay platform upgrades, and reduce new logo wins. Waystar’s revenue is sticky, but the growth narrative relies on continued expansion inside customers and continued adoption by larger systems.

And while Waystar is betting heavily on AI, competitors can buy or build similar tools. Tech giants like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have all shown interest in healthcare. If they choose to push deeper into the infrastructure layer, the competitive landscape could shift quickly—and the “AI moat” may prove less durable than bulls expect.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Two metrics warrant particular attention for monitoring Waystar's ongoing performance:

-

Net Revenue Retention Rate: Currently at 113%, this metric captures both customer retention and expansion. If it falls toward or below 100%, it signals either churn problems or exhaustion of cross-sell opportunities. Sustained NRR above 110% validates the platform strategy.

-

Number of $100K+ Clients: Currently 1,306 and growing 11% year-over-year, this metric indicates enterprise penetration and customer quality. Large customers are stickier and offer greater expansion potential. Deceleration in this metric would signal market saturation or competitive losses.

XVI. Epilogue: The Invisible Infrastructure

In the annals of American business, some companies become famous by changing how we live—the Apples and Amazons that put devices in our pockets and boxes on our doorsteps. Others build something quieter: they become so essential, so deeply embedded in critical systems, that you only notice them when they’re missing.

Waystar sits firmly in that second category. No patient schedules an appointment thinking about Waystar. No doctor orders a test with Waystar in mind. But behind the scenes—behind insurance verification, claim submission, payment posting—software like Waystar is often what makes the transaction actually happen.

That invisibility is both a constraint and a superpower. Waystar won’t ever enjoy the consumer brand halo of a Nike or the cult status of a Tesla. But it also doesn’t live and die by consumer whims. And while healthcare is heavily regulated, Waystar isn’t the kind of front-page, consumer-facing tech platform that attracts nonstop cultural and political attention.

The bigger lesson in Waystar’s story is almost annoyingly simple: sometimes the best businesses are the boring ones. Healthcare payments aren’t glamorous. Revenue cycle conferences don’t create viral moments. But companies that sit at a chokepoint—where money has to pass through, every day, no matter what—can build something unusually durable.

From here, the future can break a few different ways. Waystar could keep running the playbook: expand the product suite, keep earning larger enterprise customers, and keep compounding with the healthcare market. It could get bought by a larger healthcare IT player that wants revenue cycle capabilities—Epic, Oracle Health, or another strategic buyer with adjacent assets. Or it could see real pressure from AI-native competitors that try to redesign revenue cycle from the ground up.

What doesn’t seem likely is irrelevance. The complexity of American healthcare payments isn’t fading. If anything, the forces that made Waystar valuable in the first place—an aging population, ever-expanding compliance requirements, and persistent healthcare cost growth—suggest the market for revenue cycle software will be around for decades.

Matt Hawkins bet on that thesis when he stepped in to lead the combination of Navicure and ZirMed into Waystar in 2017. Under his leadership, Waystar sold a majority stake to EQT and CPPIB in 2019 and went public on Nasdaq in 2024.

And with nearly a billion dollars in annual revenue, industry-leading retention, and a public-market debut that validated the “invisible infrastructure” story, it’s hard to argue that the bet didn’t work.

The rails keep running. The claims keep moving. And most people will never know the name of the company helping make it happen.

XVII. Further Reading and Resources

Essential Documents:

-

Waystar S-1 Filing (SEC, 2024) – The clearest primary-source view of how Waystar makes money, what risks it carries, and what it believes the market opportunity really is.

-

CMS National Health Expenditure Data – The official scoreboard for U.S. healthcare spending, and the simplest way to anchor just how large the payments universe is that Waystar sits inside.

-

KLAS Research Healthcare IT Rankings – Independent vendor evaluations that show how revenue cycle tools perform in the real world, where reliability and service matter as much as features.

-

Bain Capital Waystar Case Study – A sponsor’s-eye narrative of the Navicure–ZirMed combination and the platform-building strategy that followed.

-

DOJ vs. UnitedHealth/Change Healthcare Case Documents – The legal record behind the merger that reshaped the competitive landscape—and triggered serious questions about neutrality in the clearinghouse layer.

-

AHA Reports on Claims Denials – A provider-industry perspective on how denial rates and administrative friction have been trending, and why “getting paid” has become a technology problem.

-

Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA) Resources – Deep, practical material on revenue cycle operations and benchmarks, useful for understanding what Waystar’s products are actually trying to improve.

Books for Context:

-

An American Sickness by Elisabeth Rosenthal – A grounded explanation of how U.S. healthcare became so expensive and administratively tangled in the first place.

-

The Innovator's Prescription by Clayton Christensen – A framework for thinking about disruption in healthcare, and why it so often moves slower than you expect.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music