Bristow Group Inc.: The Story of Offshore Aviation's Survivor

I. Introduction: The Helicopter Company That Refused to Die

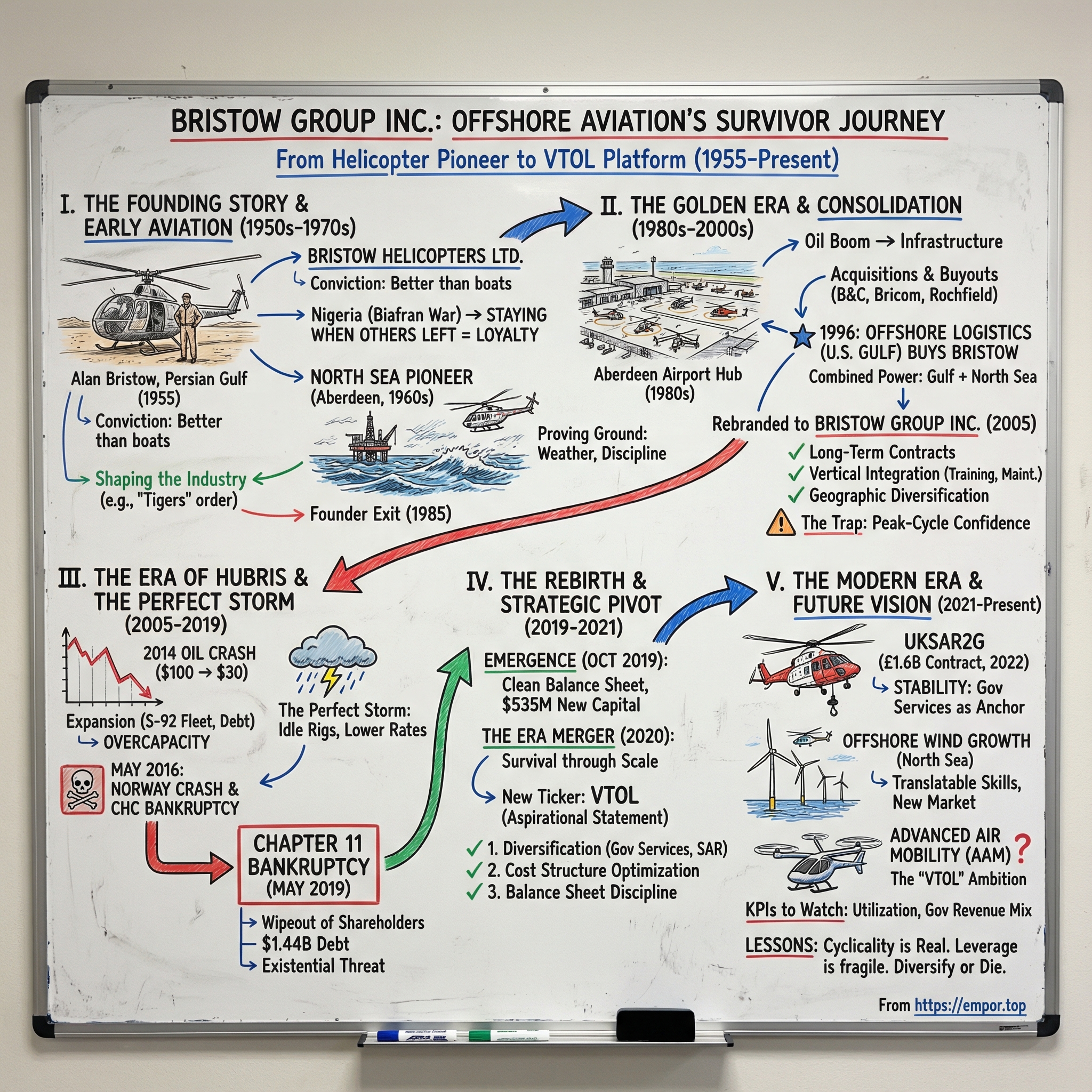

Picture the Gulf of Mexico in the predawn darkness of a November morning in 2018. A Sikorsky S-92 sits on a helipad, rotors winding up into that familiar, rising whine. Inside, a crew of roughnecks double-checks harnesses and gear, bracing for a long flight out to a deepwater platform miles from shore. For decades, some version of this scene played out again and again across offshore oil fields around the world—an industrial routine most people never see, but one that quietly keeps the energy system moving.

The operator of that helicopter was Bristow Group. And by that fall, Bristow wasn’t just moving workers. It was fighting to stay alive. Within six months it would file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, wiping out shareholders and restructuring more than a billion dollars of debt. But the helicopters kept flying. The crews kept showing up. And against the odds, Bristow would come out the other side changed—reborn with a new balance sheet, a new strategy, and even a new stock ticker meant to signal ambitions beyond oil rigs.

Today, Bristow Group Inc. is the world’s leading industrial helicopter transportation provider, with a major presence in the regions that produce offshore energy. It also runs missions like search and rescue and provides aircraft support services for government and civil organizations around the world. The fleet numbers roughly 213 aircraft, built to cover a wide range of mission profiles. With the stock trading around $37 per share, Bristow’s market capitalization is about $1.07 billion. In 2024, the company generated approximately £1.12 billion in revenue (around $1.4 billion), up from the prior year.

Bristow trades under the ticker symbol VTOL—a deliberate choice. It’s management planting a flag: we’re not only the company that ferries oil workers. We want to be a platform for vertical flight itself, spanning offshore energy, government services, offshore wind, and—if the hype becomes reality—advanced air mobility.

This is a story about survival. Bristow rode the offshore boom, overextended during the commodities supercycle, and then nearly got wiped out when oil collapsed. It went through bankruptcy—the humiliating kind that resets everything—and emerged leaner, more disciplined, and determined not to end up at that cliff again. It’s also a story about whether a company born as a critical supplier to the petroleum economy can remake itself for a world that’s trying, however unevenly, to move beyond it.

The investor question sounds simple: is Bristow a survivor built for a new era of growth, or a cyclical commodity business dressed up in forward-looking language? Let’s dig in.

II. The Founding Story & Early Aviation Era (1950s-1970s)

In the scorching summer of 1955, a thirty-one-year-old British pilot named Alan Bristow stood on the sunbaked shores of the Persian Gulf and watched a single helicopter kick up dust as it lifted off—bound for a remote drilling site with oil workers aboard. That helicopter, and the audacious idea behind it, would eventually become the backbone of the world’s largest offshore helicopter operator. But in that moment it was just one man, one aircraft, and a simple conviction: there had to be a better way to reach a rig than a slow, weather-beaten boat ride.

Alan Edgar Bristow was born on September 3, 1923. He wasn’t raised for boardrooms. He was born in Balham, South London, spent part of his childhood in Bermuda where his father ran the naval dockyard, then moved back to England and attended Portsmouth Grammar School. The shape of his life—restless, high-risk, impatient with authority—was already set long before he ever signed a contract.

Then World War II sharpened it. As a merchant navy officer cadet, Bristow survived two sinkings, played a part in the evacuation of Rangoon, and was credited with shooting down two Stukas in North Africa. It reads like folklore, but the pattern is unmistakable: danger, improvisation, and a refusal to back down.

In 1943, he joined the Fleet Air Arm as a trainee pilot. He trained with the RAF in Canada on the Fairchild Cornell and North American T6 Harvard, then in 1944 was sent to Floyd Bennett Field in New York to learn the Sikorsky R-4—the first mass-production military helicopter, and a notoriously difficult machine. Two years later, he became the first Briton to land a helicopter on the deck of a naval frigate at sea.

After the war, Bristow’s career didn’t settle down so much as detonate in every direction. He joined Westland Aircraft as its first helicopter test pilot, then was sacked for attacking the company’s sales manager. He went freelance, spraying crops across France, the Netherlands, and North Africa. He was brilliant, combative, and completely uninterested in playing nice with bureaucracy.

He started his own helicopter trading and operating business in 1949. While in Indochina trying to sell Hiller 12A helicopters to French Army forces, he used one of his own helicopters to rescue French soldiers under Viet Minh mortar fire and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Later, he even provided helicopter spotting services for Aristotle Onassis’s pirate whaling fleet in the Antarctic.

Take that in: test pilot, brawler, crop duster, decorated rescuer, and occasional participant in illegal whaling logistics. This was not a man who built companies by carefully following precedent.

The offshore oil opportunity arrived as a practical solution to a practical problem. Oil and gas companies in the Persian Gulf needed to move crews and supplies to offshore rigs, and the existing boat service was too slow. So on June 24, 1955, Bristow established Bristow Helicopters Limited after winning a contract with Shell Oil Company to transport crews and materials offshore. Two years later, a BP contract gave the firm enough footing to purchase its own aircraft: a pair of Westland Widgeons. And with that, Bristow did what he always did—he went looking for the next frontier. Recognizing that few companies could afford helicopters, he chased work globally, soon launching ventures in Iran and Bolivia.

The thesis was elegantly simple. Offshore rigs are reachable by boat or by helicopter. Boats are slow, constrained by sea state, and risky when it comes time to transfer people. Helicopters are fast, flexible, and—if maintained obsessively—safe. Oil companies would pay for that reliability because the alternative wasn’t inconvenience; it was lost drilling time. And lost drilling time was lost money.

In 1960, Bristow made a move that would shape the next decade: he entered Africa by acquiring crop-spraying specialist Fison-Airwork, which already operated in Central Africa. Bristow soon exited crop spraying to focus on oil exploration work in Nigeria for Shell. By the start of the Biafran War in 1967, the company had 11 helicopters committed to the Nigerian effort, based at Port Harcourt. Early in the conflict, Bristow helped evacuate oil workers to the safety of Fernando Po. And even as the war ground on, Bristow maintained operations—reduced, but present—via Lagos and Warri.

That decision mattered. Staying when others pulled out gave Bristow a head start when oil companies returned after the war ended. And for much of the 1970s, Nigeria became Bristow’s biggest profit centre.

This willingness to operate in difficult, dangerous environments became a defining trait. It wasn’t bravado for its own sake. It was a business strategy that created loyalty: if you’ve kept flights running through chaos, customers remember you when it’s time to renew.

Around the same time, Bristow set its sights on the North Sea. In the mid-1960s, it became the second helicopter operator—after BEA Helicopters Limited—to establish operations at Aberdeen. That early position put it in the right place at the right time. Beginning February 17, 1965, Bristow operated the Westland Wessex 60 ten-seat helicopter to support offshore installations. Through the 1970s, it expanded around Aberdeen, building its main oil and gas support hub at Dyce Airport. In 1972, it stationed the first of several Sikorsky S-61N helicopters at Sumburgh Airport to support Shell’s offshore rigs.

The North Sea didn’t just create demand. It forged reputations. As fields like Forties, Brent, and Piper came online, everyone needed reliable helicopter transport across some of the harshest flying conditions in the world—cold, fog, brutal winds, and seas that seemed designed to punish mechanical mistakes. It was a proving ground for both pilots and operators.

Bristow didn’t only scale to meet that demand. It helped shape what the industry would fly. The first Super Pumas for the oil and gas market were introduced in 1982. Bristow worked with Aerospatiale (today’s Airbus Helicopters), in consultation with oil and gas customers, to design a purpose-built commuter helicopter. The specification included baggage stowage behind the cabin, more flexible seating, customized avionics, bigger windows, and improved flotation devices. Once the design was finalized, Bristow ordered 35—at the time, the largest civil helicopter order ever made, a record that still stands. Alan Bristow christened the fleet the Bristow “Tigers.”

By the time he stepped down from active management in 1985, Bristow had built an aviation empire. Bristow Helicopters Ltd expanded across much of the globe outside Russia and Alaska, with major profit centres in the British North Sea, Nigeria, Iran, Australia, Malaysia, and Indonesia. But his departure—after a falling-out with Lord Cayzer, whose family holding company British & Commonwealth was among the shareholders—marked the end of the founder’s era. Bought out by the Cayzers, Bristow retired, and the company’s fortunes later declined alongside the North Sea oil industry.

Still, the founder left behind something more durable than routes and aircraft. He’d embedded a way of operating: relentless focus on safety, maintenance discipline, and customer trust. Those intangible advantages—earned over decades, and paid for in hard lessons—would become the foundation Bristow relied on when the industry turned and the easy years ended.

III. The Golden Era: Riding the Offshore Oil Boom (1980s-2000s)

Aberdeen, Scotland. Winter, 1985. Wind tore in off the North Sea, sleet rattling against the hangars at Dyce Airport. Inside, mechanics worked through the night on the machines that had turned a modest regional airfield into critical national infrastructure. Bristow had become Aberdeen Airport’s largest single employer, growing its local headcount dramatically and operating the bulk of North Sea offshore flights. In 1980 alone, nearly 400,000 passengers and more than 2,300 tons of freight moved through Bristow’s Aberdeen terminal.

This was the golden era. Oil prices were volatile, but high enough to keep offshore development charging ahead. The UK Treasury collected billions in petroleum revenue. And Bristow Helicopters sat right in the middle of it—an indispensable link between shore and rig.

But the company Alan Bristow built was about to spend the next decade and a half changing hands. In 1985, Bristow Helicopters was acquired by British and Commonwealth Holdings plc. Three years later, it was sold as part of the Bricom Group via a management buyout. In 1990, Bricom was acquired by Scandinavian investment firm Rochfield. Then in 1991, Bristow went through yet another management buyout, this one led by managing director and chief executive Bryan Collins.

Those deals showed two truths at once: the business was sturdy enough to keep attracting buyers, and fragile enough that it could be tossed around when the cycle turned. When oil prices plunged in 1986, the offshore helicopter sector thinned fast. Bristow survived—and took advantage—acquiring British Caledonian Helicopters in 1987. The industry’s rhythm was already clear: oil drops, weaker operators fall over, and the survivors consolidate.

The pivotal shift came in 1996. Bristow Helicopters was purchased by Offshore Logistics, an American offshore helicopter operator that had previously operated as Air Logistics in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico and Alaska. The deal was structured as a reverse takeover, but the substance mattered more than the paperwork: it created the only helicopter operator with deep positions in both the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea.

Offshore Logistics traced back to Louisiana and to founder Burt Keenan, who started the business in 1969 to support the rapidly expanding offshore oil industry. At first, the company moved people and gear by boat, running down Louisiana’s bayous to the Gulf. But offshore work runs on time, and time is money—so as demand for faster, more reliable crew changes grew, helicopters became the tool of choice.

Offshore Logistics got battered in the oil bust of the 1980s and was forced into restructuring and brutal cost cuts. It sold its corporate office and pared back aviation and marine equipment. The lesson Keenan took from that era was simple: if you’re tied to one basin or one cycle, you’re one downturn away from disaster. Diversification—geographic and operational—wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was survival.

Buying Bristow delivered that diversification in one move. It also brought something harder to quantify: North Sea know-how. The North Sea was the industry’s harshest proving ground, where operators developed tighter safety protocols, more disciplined maintenance procedures, and deeply embedded relationships with oil majors—advantages that took years to earn and were almost impossible to copy quickly. And now, under one roof, the combined business could credibly serve both the Gulf and the North Sea.

By 2001, Offshore Logistics—headquartered in Lafayette, Louisiana—operated one of the largest commercial helicopter fleets in the world through a web of subsidiaries and partly owned affiliates. In 2005, it moved its corporate headquarters to Houston to place itself “in the heart of the international energy industry.” Not long after, it rebranded as Bristow Group, Inc., elevating the Bristow name from a storied subsidiary into the identity of the whole enterprise.

Out of all that consolidation, a recognizable business model took shape.

First: long-term contracts with oil majors. These deals typically ran three to seven years with extension options, giving the company more visibility than you’d expect in such a cyclical industry. Bristow, for example, secured a seven-year contract with Shell Exploration UK. In practice, these weren’t simple vendor arrangements. They were relationships built on a currency that mattered offshore: trust.

Second: vertical integration. Bristow wasn’t just flying; it invested heavily in the support stack—maintenance, parts, and training. Training, in particular, had deep roots. Back in 1961, Bristow Helicopters began training helicopter pilots for the Royal Navy at Redhill Aerodrome in Surrey, and soon picked up more training work with operators in India, Australia, and New Zealand. That line of business expanded again in April 2007 when Bristow Group acquired Helicopter Adventures, a Florida-based flight school that it renamed Bristow Academy. The deal also brought in what was described as the world’s largest civilian fleet of Schweizer aircraft.

Third: geographic diversification. Offshore Logistics operated beyond the U.S. and the UK, with support services across Africa, Asia, the Pacific Rim, and Central and South America. The theory was straightforward: if one region softened, another might hold up.

By the early 2000s, the setup looked ideal. Oil began climbing from the lows of the late 1990s, and offshore drilling pushed into deeper water and more demanding conditions. Bristow’s experience in difficult environments—the North Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, West Africa—positioned it well for that next wave.

And for a moment, it was easy to believe the worst of the oil-price roller coaster had been engineered away. The 1990s had been survived. The map was broader. The contracts were longer.

That confidence would prove dangerous. As oil climbed through the 2000s, Bristow—and the entire offshore helicopter industry—started making bets that assumed the boom was the new normal. It wasn’t.

IV. The Era of Hubris: Expansion and the 2014 Oil Crash Setup (2005-2014)

Houston, Texas. A trading floor, circa 2012. Oil is above $100 a barrel, and it’s been there for years. Energy executives talk about “the new normal”—Chinese demand, declining output from mature fields, the idea that scarcity will keep prices permanently high. For offshore helicopter operators, the message sounds simple: invest now, because the flying will only increase.

Across the industry, that’s exactly what happens. By 2014, the global offshore helicopter fleet swells to roughly 1,800 aircraft—an all-time high—just before an oil glut and new supply send prices into a collapse that takes crude down toward the $30s. In hindsight, this era is a familiar story: peak-cycle confidence turning into peak-cycle capital spending.

It isn’t just more helicopters. It’s a step-change in the kind of helicopters the offshore world is buying. Deepwater fields are farther offshore, harsher, and less forgiving. The industry needs longer range, more payload, higher speed, and the latest safety systems. A new generation arrives right on cue: the Airbus EC225 (now the H225), Sikorsky’s S-92, and Leonardo’s AW139 enter offshore service in 2004 and 2005. By 2014, they’re joined by the “super medium” class—the Leonardo AW189 and Airbus H175—built for exactly these longer, tougher routes.

Bristow doesn’t sit on the sidelines. It leads the modernization wave, leaning hard into the heavy aircraft that can service deepwater operations. In 2013, Sikorsky Aerospace Services announces a 10-year Total Assurance Program agreement with Bristow to support its S-92 fleet. The deal—worth more than $840 million—is a renewal of an existing contract that had run for seven years.

The S-92 is the flagship of Sikorsky’s civil line, certified to stringent FAA and EASA standards. It seats 19 passengers and becomes the workhorse of deepwater offshore. But it comes with a price tag that changes the whole risk profile of the business: each aircraft lists at more than $25 million. Building a meaningful fleet means committing enormous capital.

At the time, Bristow’s logic is hard to argue with. Deepwater drilling is booming. The Gulf of Mexico, West Africa, and Brazil all need long-range helicopters that can operate safely in punishing conditions. Older aircraft are being retired. And the contracts with oil majors are long enough—three to seven years, often more with extensions—that you can convince yourself these investments will pay back.

But the trap is already set.

The warning signs are visible if you want to see them. Revenue is concentrated in a handful of powerful buyers. Those long contracts often include provisions that allow renegotiation or cancellation when the cycle turns. And underneath everything sits a single, fragile assumption: oil prices will stay high enough that offshore investment continues.

The industry’s financial structure makes that assumption existential. Helicopters are expensive. Financing is a mix of ownership, operating leases, and long-term debt. And the costs don’t flex much when demand drops: aircraft payments, maintenance reserves, pilot staffing, facilities. When oil companies cut flying, the helicopter operator still has to write the checks.

Worse, the boom encourages everyone to expand at once. Bristow, CHC, PHI, and ERA all add capacity in parallel, each believing they’re prudently meeting demand. Individually, it looks rational. Collectively, it creates overcapacity on a global scale—capacity that becomes lethal the moment the customer base hits the brakes.

When the downturn arrives, the economics snap. With too many heavy helicopters chasing too few hours, lease rates crater. S-92A leases fall from roughly $240,000 a month at the peak in 2014 to around $100,000 to $115,000 a month in the wreckage that follows.

The surplus is staggering. Roughly 20% to 30% of the global offshore fleet becomes excess. Heavy offshore helicopters, once a significant share of new deliveries, shrink to a much smaller slice as the market stops ordering what it can’t profitably use.

From 2010 to 2014, the industry convinces itself it has solved cyclicality: long-term contracts will protect margins, geographic diversification will smooth regional slumps, and the new aircraft will always command premium pricing. In reality, those beliefs are most seductive at the top—and most brittle when the cycle turns.

By the time the trigger arrives, the system is already primed. One shock is all it takes.

And that shock comes in the summer of 2014, when the world realizes it has more oil than it knows what to do with.

V. The Perfect Storm: Oil Crash & Existential Crisis (2014-2019)

The first tremors hit in June 2014. Brent crude, which had lived above $100 a barrel for years, started slipping. By October it was under $90. By December it punched through $60. And in January 2016, it touched $27—an almost unthinkable number for an industry that had been planning its future as if high prices were permanent.

Offshore helicopters don’t sell tickets to tourists. They sell hours to a single customer base: the offshore oil-and-gas machine. So when oil companies began cutting, the helicopter business didn’t just slow down—it hollowed out. Exploration drilling got shelved. Big development projects were deferred. Crew rotations were extended. Flights were consolidated. Bases were closed. Contracts were re-tendered with one demand at the top of the list: lower monthly rates.

That translated into a cascading, very physical decline. Fewer rigs meant fewer helidecks in service. Fewer offshore workers meant fewer seats filled. And every “efficiency” initiative the majors rolled out became a direct hit to Bristow’s core metric: utilization—the share of available flying that actually gets sold. In the U.K., for example, major oil companies extended rotation schedules from two weeks on and two weeks off to three weeks on and three weeks off. Great for cutting costs. Brutal for the number of flights required to keep platforms staffed.

The offshore helicopter industry had survived oil cycles before. Helicopters had supported oil and gas since 1947, when Bell 47s carried exploration crews across the wetlands of southern Louisiana and later out over the water. Boom-and-bust was familiar. But this downturn cut deeper, lasted longer, and collided with something new: a globally expanded fleet built for peak-cycle demand and financed with peak-cycle leverage.

Then came a week that captured the whole crisis in miniature.

On April 29, 2016, an H225 crashed in Norway, killing everyone on board. The shock didn’t stay local. The fleet was temporarily grounded worldwide, and one of the industry’s key workhorses was suddenly sidelined. Less than a week later, on May 5, 2016, CHC—one of the biggest players in offshore helicopter transport—filed for Chapter 11. In seven days, the market absorbed both a tragedy that rattled confidence and a bankruptcy that confirmed the business model was cracking.

As the downturn dragged on, the pressure spread beyond operators to the ecosystem around them. Idle aircraft and high debt loads forced reshuffles in ownership and management across the sector. Between 2016 and 2019, the pain reached the top: CHC, PHI, and Bristow—three of the world’s largest offshore operators—all ended up in Chapter 11, using the court to cut debt and shrink fleets.

For Bristow, 2014 to 2019 was less a single collapse than a slow-motion catastrophe. Management tried to generate cash and buy time. It sold non-core assets. In 2019, Bristow completed the sale of the U.K.’s Eastern Airways and still aimed to sell its stake in Australia’s Airnorth, hoping the two deals would bring in about $230 million combined. It cut staff in multiple rounds. It fought to restructure contracts. It negotiated with creditors.

But the core problem wasn’t operational—it was mathematical.

Bristow had loaded up on debt to build and modernize its fleet at the top of the cycle. When demand fell, the market value of those aircraft dropped, rates reset lower, and the fixed obligations stayed stubbornly fixed. By September 30, 2018, Bristow’s total debt stood at $1.44 billion. In a shrinking market, that kind of leverage turns a downturn into an existential threat.

Even the companies that financed the fleet started breaking. In November 2018, Waypoint Leasing—the world’s second-largest helicopter lessor—entered Chapter 11 itself and was later purchased by a unit of Macquarie Group for $650 million. When lessors can’t survive the rental market, you’re no longer looking at a normal cycle. You’re looking at a system that has seized up.

So when Bristow filed for Chapter 11 on May 11, 2019, it wasn’t a surprise so much as an inevitability. The filing affected North America operations, while overseas operations continued unchanged. The business still had customers, aircraft, pilots, hangars, and decades of operational credibility. What it didn’t have was a balance sheet that could survive the revenue it was now capable of generating. As in most restructurings, the old equity was wiped out.

The process was painful—but it accomplished what ordinary cost cutting couldn’t. Chapter 11 eliminated the debt load that had made survival impossible. It gave Bristow room to right-size the fleet and reset obligations. And it created a cleaner starting point from which to rebuild.

For shareholders who lived through it, it was devastating. For Bristow as an operating enterprise—the flights, the maintenance, the relationships—bankruptcy was a second chance.

It also rewired the industry’s beliefs. Long-term contracts no longer felt like real protection. Aggressive leverage no longer looked like smart growth. And diversification away from pure oil-and-gas dependency stopped being a talking point and became a requirement.

When Bristow emerged from bankruptcy in October 2019, the question wasn’t whether the helicopters would keep flying. It was what kind of company would be flying them next.

VI. The Rebirth: Emerging from Bankruptcy & Strategic Pivot (2019-2021)

October 31, 2019. Less than six months after filing, Bristow Group emerged from Chapter 11 with a reworked balance sheet designed to keep the company flying. The speed mattered. Bankruptcies in capital-heavy industries can drag on for years; Bristow’s was over in under five months.

The U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas confirmed the company’s Amended Plan of Reorganization. Bristow emerged as a privately held company, with affiliates of Solus Alternative Asset Management LP, South Dakota Investment Council, Empyrean Capital Partners, LP, Bain Capital Credit, and Oak Hill Advisors expected to collectively own more than half of the equity.

The new Bristow was funded, in large part, by its former creditors. Under the plan, the company received $535 million of new capital from a majority of its secured and unsecured noteholders—$385 million through an equity rights offering, plus a $150 million debtor-in-possession loan that converted into new equity at emergence.

Just as important as the new money was what disappeared. Debt levels were slashed, and the interest burden that had been eating the business alive was removed. Bristow came out with $535 million of new capital and argued it now had the financial flexibility to support its global operations without living on the edge.

Leadership was also being reset. L. Don Miller, who had joined Bristow in 2010 and served in several senior roles, became President and CEO in February 2019. He’d been CFO, ran mergers and integration, and led strategy and structured transactions—experience that suddenly wasn’t academic. It was the job.

But a cleaner balance sheet didn’t fix the underlying vulnerability. Bristow still depended heavily on offshore oil and gas—an end market that had just proven it could stay ugly for years. Without a real strategic shift, the next oil crash would simply rerun the same movie.

That’s why, in January 2020—only three months after emerging—Bristow announced a deal meant to reshape the industry: a merger with Era Group. Both boards approved the transaction unanimously, with closing expected in the second half of 2020. The ownership split was set: Bristow shareholders would own 77% of the combined company, and Era shareholders 23%.

The timing wasn’t an accident. The offshore helicopter sector was still stuck in uncertainty, and Era had become the rare operator that made it through the downturn without filing for Chapter 11. Era’s president and CEO, Chris Bradshaw, attributed that survival to being early and aggressive on cost reductions, squeezing utilization, and hunting for operational synergies.

Bradshaw’s real value wasn’t a slogan—it was credibility. He’d proven, in the same brutal market, that discipline and flexibility could keep a helicopter operator out of court.

And he made the merger’s logic explicit: “Nothing about this merger is counting on a significant recovery in the offshore oil-and-gas market.” The combination, he said, was compelling based on the current level of activity.

That line captured the new philosophy. Instead of wagering on a rebound that might never arrive, Bristow was trying to build a company that could work even when the market didn’t.

The deal closed in June 2020, and the combined company’s common stock began trading under a new ticker: VTOL. It kept the Bristow Group name and remained listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

“The closing of this strategic and financially compelling merger makes Bristow a larger, more diverse and stronger company, better positioned for the future,” Bradshaw said. He framed it as long-overdue consolidation—scale that would help the business navigate a tough market while staying the global leader in helicopter services.

But the “tough market” was about to get tougher. Closing in June 2020 meant the new Bristow walked straight into COVID-19. In April 2020, oil prices briefly went negative—an event that had previously belonged to the realm of theoretical finance and bad jokes. The difference this time was that Bristow’s post-bankruptcy financial structure was built to absorb shocks, not amplify them.

Out of the bankruptcy and the Era merger, a three-part pivot took shape.

First, diversification beyond oil and gas. Bristow remained a global leader in offshore transportation, but it also leaned into search and rescue and aircraft support services for government and civil organizations. Those contracts generated meaningful revenue and cash flow that didn’t swing with crude prices, and the UK Search and Rescue contract stood out as a stabilizing anchor.

Second, cost structure optimization. The merger was built to deliver synergies, with run-rate synergies described at the time as $35 million. The playbook was straightforward: consolidate overlapping facilities, cut corporate overhead, and rationalize the combined fleet.

Third, balance sheet discipline. Bankruptcy had forced the lesson, and management wasn’t eager to forget it. No more aggressive leverage to chase capacity. No more pretending the cycle can’t hurt you if you just sign long enough contracts.

The combined company operated a fleet of 303 aircraft, with most of them owned. That scale made Bristow the world’s largest operator of Sikorsky S-92 and Leonardo AW189 and AW139 helicopters—the modern workhorses of offshore flying.

And then there was that new ticker. VTOL—Vertical Take-Off and Landing—was more than a label. It suggested Bristow saw itself as something bigger than an oil-and-gas shuttle service: a platform for vertical flight, potentially extending to the emerging world of electric aircraft. Whether that ambition would become reality was still an open question. But after bankruptcy, Bristow wasn’t interested in simply surviving the next cycle.

It wanted to change what it was.

VII. The Modern Era & Future Vision: VTOL as Infrastructure (2021-Present)

In July 2022, Bristow got the kind of contract that changes how investors talk about a company.

Bristow Helicopters Ltd was awarded a £1.6 billion, 10-year deal for the Second-Generation Search and Rescue Aviation program—UKSAR2G—by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency, an executive agency of the UK Department for Transport. For a business that had just lived through the whiplash of oil cycles and bankruptcy court, the appeal was obvious: real revenue visibility stretching well into the 2030s, tied to public service rather than crude prices.

UKSAR2G wasn’t a light lift. The scope covered 18 helicopters—nine existing Leonardo AW189s and three existing Sikorsky S-92s, plus six new Leonardo AW139s. It also included fixed-wing aircraft: six King Air planes (the B350, B350ER, and B200) operating out of Doncaster, Prestwick, and Newquay. And there was a small but telling detail: one mobile, deployable Schiebel CAMCOPTER S-100 uncrewed aircraft system—Bristow’s first operational drone deployment.

This wasn’t just “diversification.” It was a mission employees could feel in their bones. Bristow’s UK search-and-rescue team operates from 10 bases across the country, and in the year ending March 31, 2022, it flew 2,747 missions and rescued 1,608 people. After decades of being measured in flight hours and day rates for oil majors, Bristow now had a core franchise centered on saving lives.

The government-services push didn’t stop with the UK coastline. On August 2, 2022, Bristow acquired British International Helicopter Services Limited (BIH). BIH was part of an 18-year partnership with the UK Ministry of Defence in the Falklands, with its current 10-year contract having begun in April 2016. Bristow also landed a 10-year deal from the Netherlands Defence Materiel Organisation to provide search-and-rescue helicopter capacity to the Netherlands Coastguard, combining operations from bases in Curacao serving the Dutch Caribbean region.

The common thread across these government contracts is what Bristow had been missing at the top of the cycle: long duration—often a decade—stable pricing structures, and highly credible counterparties.

If government services are the stabilizer, offshore wind is the growth narrative—and the most intriguing part of Bristow’s attempted reinvention. The bet is intuitive: as offshore wind farms multiply, someone has to move technicians, tools, and parts safely and quickly to turbines far out at sea. That increasingly looks like a helicopter job.

The UK numbers underline why this gets attention. By 2025, the country had over twelve thousand wind turbines totaling 32 gigawatts of installed capacity—split evenly between onshore and offshore. And the government committed to expanding offshore capacity to 60 gigawatts by 2030, including 5 gigawatts from floating wind.

The broader North Sea region is one of the world’s premier offshore wind theaters, helped by relatively shallow waters, strong wind patterns, and close proximity to ports and industrial demand. In 2012, cumulative offshore wind installation in the region was around 4.5 gigawatts. By 2021, that figure had grown to 27.8 gigawatts.

For Bristow, the attraction is that the playbook mostly transfers. The same aircraft categories can serve turbines. The same safety culture matters. The same maintenance and dispatch discipline applies. And Bristow’s decades of North Sea operating experience—earned the hard way—can translate directly.

But it’s not a perfect one-for-one substitute. Oil platforms run continuously and drive constant, high-volume crew rotations. Wind turbines are serviced more intermittently, often by smaller teams. That difference can mean a different revenue profile: less predictable, potentially lower-margin, and likely more competitive.

Against that backdrop, Bristow’s recent financial performance helps ground the story in reality. In its Q3 2025 results, the company reported total revenue of $386.3 million and net income attributable to the company of $51.5 million, or $1.72 in diluted EPS, for the quarter ended September 30, 2025. Adjusted EBITDA for the quarter was $67.1 million. Management updated its outlook to 2025 Adjusted EBITDA of $240–$250 million and 2026 Adjusted EBITDA of $295–$325 million, and reiterated approximately 27% year-over-year Adjusted EBITDA growth for 2026.

The drivers weren’t mysterious: a steadier Government Services business, focus on production-support activity within Offshore Energy Services, and diversification across geographies. By segment, Offshore Energy Services revenue rose 5.4%, Government Services increased 7.6%, and Other Services climbed 25.5%.

Then there’s the most futuristic—and most uncertain—piece of the story: advanced air mobility.

Bristow has made clear it wants a seat at the eVTOL table when that market arrives. Its subsidiary Bristow Arabia Aircraft & Maintenance Services and Saudi Arabia’s The Helicopter Company disclosed an agreement to work together on AAM initiatives in the Kingdom. Bristow has also described tentative agreements for substantial numbers of AAM aircraft from multiple manufacturers, including uncrewed hybrid cargo drones and electric-powered short- or vertical-takeoff aircraft for cargo or passenger transport.

Is that real, or is it narrative?

The honest answer is that it’s still too early to call. eVTOL aircraft remain largely in development, and certification and scaled commercial deployment are still years away. Bristow’s potential advantages—existing infrastructure, maintenance capability, and long experience working with regulators—could matter a lot if and when the market shows up. But it’s not a thesis to buy the stock on today.

Which brings us back to the ticker: VTOL. It was never meant to be subtle. It’s an aspirational statement that Bristow wants to be more than “the oil helicopter company.” Whether that ambition turns out to be prescient—or premature—will only become clear over time.

VIII. The Business Model & Competitive Analysis

To understand Bristow, you have to understand the machine it operates inside of. Offshore helicopter flying is a brutal mix of aviation and heavy industry: high fixed costs, strict regulation, and customers who buy in bulk and negotiate like it’s their job—because it is. The upside is that once you’re embedded, you can become mission-critical. The downside is that when the cycle turns, the floor can fall out fast.

Two lenses help make sense of it: Porter’s Five Forces (how the industry behaves) and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers (whether Bristow has durable advantages).

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: HIGH barriers, but bankruptcy showed vulnerabilities

On paper, this is a hard industry to break into. Offshore-capable helicopters cost tens of millions each. Regulatory approvals from the FAA, EASA, and national aviation authorities are slow and exacting. Offshore work demands specialized training, safety systems, and a track record that oil majors and governments trust.

But the wave of bankruptcies in the late 2010s proved a painful point: these barriers keep out new competitors; they don’t protect incumbents from the cycle. When oil crashes, the threat isn’t a startup with shiny helicopters. It’s your own balance sheet.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM

The supply side is concentrated. Sikorsky, Leonardo, and Airbus dominate the offshore-capable market. That gives manufacturers meaningful leverage—there aren’t many substitutes when you need a specific class of aircraft with specific certifications.

Bristow’s counterweight is scale. With a large global fleet, it can negotiate support and service programs that smaller operators can’t. But even with that leverage, Bristow can’t just “switch suppliers” the way a software company switches vendors. Fleet choices are multi-decade commitments.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

This is the industry’s structural pressure point. In offshore energy, the buyers are oil majors and large independents—sophisticated, price-sensitive, and powerful. When they want rates lower, they have multiple ways to get there: rebid contracts, consolidate providers, renegotiate terms, and reduce flying demand operationally.

You saw that in the U.K. when major operators extended worker rotation schedules from two weeks on/two weeks off to three weeks on/three weeks off. It sounds like an HR tweak. For a helicopter operator, it’s fewer passengers, fewer flights, and less revenue—without a matching reduction in fixed costs.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM, evolving

For many missions, the helicopter is still the only tool that works. Deepwater assets far from shore can’t be reliably served by boats without sacrificing speed and flexibility.

But “substitute” doesn’t have to mean replacing crew transport. It can mean stripping away adjacent, high-value tasks. Drones are increasingly used for surveying, inspection, and monitoring—work that used to require manned flights. Uncrewed systems can carry sensors, operate autonomously, and stay in the air longer. Over time, that can reduce demand for certain helicopter hours, especially around inspection of pipelines and wind turbines.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM after consolidation

The sector was forced into consolidation by pain. Between 2016 and 2019, CHC, PHI, and Bristow—three of the largest offshore operators—each went through Chapter 11 to cut debt and shrink fleets. That reset improved pricing discipline because fewer overlevered players were dumping capacity just to survive.

Even so, the work is still awarded through competitive tenders. Regional operators—particularly in Africa and the Middle East—can show up with lower cost structures and compete hard on price. So rivalry is calmer than the worst years, but it never disappears.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: YES—meaningful but not decisive

Bristow’s fleet—roughly 213 aircraft today, and larger when combined with Era—creates real operating leverage: maintenance efficiency, parts inventory, training infrastructure, and the ability to shift aircraft across geographies as demand changes. Scale also helps when you’re trying to be the “default” provider for a global customer.

But these scale benefits are capped. In any given region, an operator with a smaller fleet can still run a tight operation. Scale helps, but it isn’t a knockout punch.

Network Economies: LIMITED

There are hints of network effects in maintenance and training—bigger fleets justify deeper parts pools and broader training capabilities. But it’s not the kind of network effect where each additional customer makes the service inherently more valuable to everyone else. This is still, at its core, a contract services business.

Counter-Positioning: NO

Much of Bristow’s post-bankruptcy playbook—diversifying into government services, positioning for offshore wind, keeping a modern fleet—can be replicated by competitors with capital and execution. There’s no obvious structural reason rivals can’t follow the same road.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Switching costs exist, and they’re mostly about trust. Offshore flying is safety-critical, reputationally sensitive, and operationally complex. Customers don’t love changing operators because they’re not just buying aircraft—they’re buying procedures, training standards, dispatch discipline, and confidence in how the operator behaves when something goes wrong.

At the same time, switching is not impossible. Procurement departments rebid contracts, and price pressure can overwhelm comfort. So the stickiness is real, but it’s not permanent.

Branding: MODERATE

The Bristow name still means something—decades in the North Sea, long relationships with majors, and a reputation built around safety and reliability. But this is not consumer aviation. Brand helps open doors and win credibility; it doesn’t by itself guarantee renewals.

Cornered Resource: YES—selectively

Some assets are genuinely scarce. Government contracts can be exclusive for long periods—UKSAR2G being the clearest example, a £1.6 billion, 10-year program. Prime bases and heliport access in constrained locations can also be hard to replicate. And certain regulatory approvals and government operating footprints take years to establish.

These aren’t universal across the business, but where Bristow has them, they’re meaningful.

Process Power: YES—built over decades

This is Bristow’s deepest advantage. The hardest thing to copy isn’t a helicopter model—it’s an operating system. Safety management, maintenance discipline, pilot training, standard operating procedures, emergency response readiness, and the culture that holds it all together.

Bristow’s U.K. search and rescue work illustrates it. The Maritime and Coastguard Agency awarded Bristow the UK Search & Rescue helicopter contract in 2013, transitioning a mission previously handled by the Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force, and HM Coastguard. By the year ending March 31, 2022, the team operating from 10 bases flew 2,747 missions and rescued 1,608 people. That level of performance is not something you bolt on overnight.

A competitor can buy similar aircraft. It can’t easily buy fifty years of hard-earned operational maturity in North Sea weather.

Conclusion: Real but limited moats

Bristow does have advantages: scale, meaningful switching friction, a handful of genuinely scarce contracts and locations, and strong process power. But the Achilles heel remains the same one that nearly killed it: commodity exposure. When offshore energy demand contracts, even the best operator feels it.

Diversification—especially into government services—reduces that vulnerability. It doesn’t eliminate it.

IX. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

At this point, Bristow comes into focus as the kind of company investors argue about in opposites. On one side: a post-bankruptcy survivor with a steadier contract base and a new growth lane in offshore wind. On the other: a capital-intensive operator still tethered, in large part, to the oil cycle that nearly killed it.

Here’s what each side is really saying.

The Bull Case

1. Offshore oil production remains essential for decades

For all the energy-transition headlines, global oil demand has continued to rise. And offshore production—especially deepwater—still represents some of the more economical barrels left to develop. The basic claim behind the bull case is blunt: the world won’t move off hydrocarbons fast enough to make offshore aviation irrelevant within a typical investment horizon.

2. Offshore wind represents a massive growth market

Offshore wind is the most natural “next customer” for an offshore helicopter operator. In the U.K. alone, another 47.3 gigawatts are in early planning stages. If proposed projects are built out, by the 2030s the U.K.’s nameplate capacity is expected to reach roughly 79 gigawatts. Bristow’s argument is that its North Sea operating experience—and the muscle memory of running safety-critical missions in harsh weather—translates. The work isn’t identical to oil and gas, but the operational DNA is close.

3. Post-bankruptcy balance sheet is clean

The reorganization reset the company’s financial structure. Bristow emerged with $535 million of new capital, and management has emphasized more conservative financial policies after learning the hard way what leverage does to a fixed-cost business in a downcycle. In the bull framing, this is the difference between “cyclical” and “fatal.”

4. Consolidation created improved pricing power

A decade ago, the offshore helicopter world had too many aircraft and too many operators chasing the same shrinking set of hours. The bankruptcies of CHC, PHI, and Bristow—and Bristow’s merger with Era—helped shrink the field. The optimistic read is that fewer weakened players dumping capacity means better pricing discipline, more rational fleet sizing, and real synergy capture to spread the cost of running an air carrier over a larger base.

5. Government services provide stability

This is the most concrete piece of the “new Bristow” story. The Government Services segment is designed to be the ballast—work that keeps paying when oil doesn’t. The UKSAR2G contract alone represents £1.6 billion of contracted revenue over ten years, backed by a government counterparty and insulated from oil price volatility.

6. Valuation appears reasonable

With the stock around $37 per share and a market cap of roughly $1.07 billion, Bristow isn’t priced like a high-growth story. Bulls look at a company generating around $1.4 billion in annual revenue with improving margins and see room for upside if management keeps executing and diversification keeps compounding.

The Bear Case

1. Oil & gas faces secular decline

The transition may be uneven, but it’s not imaginary. Capital is flowing into renewables, and European oil majors are increasingly cautious about long-cycle offshore spend. Bears don’t need offshore oil to disappear tomorrow. They just need it to grind down over time, taking helicopter demand with it.

2. Another oil crash could devastate the company

This is the scar tissue talking. The 2015-era crash pushed almost every major offshore helicopter operator into Chapter 11. High fixed costs and commodity-linked demand haven’t gone away. A sustained oil environment below $40 would threaten to replay the same pressures that built from 2015 to 2019.

3. Offshore wind competition may be fierce

Wind sounds like the obvious adjacency, but it won’t necessarily be a profit pool. Local operators can compete aggressively, and for some servicing, shipborne transfer vessels can be substitutes. Even if wind grows fast, the worry is that margins could be structurally lower than legacy oil-and-gas flying.

4. eVTOL is years away and may not require Bristow

The advanced air mobility narrative is still speculative. Certification timelines, infrastructure needs, and real customer demand are all uncertain. And even if eVTOL becomes real, it’s not guaranteed incumbent helicopter operators win; new entrants—possibly tech-driven—could own the market.

5. Customer concentration creates vulnerability

Bristow still depends heavily on a handful of major oil and gas customers. In a contract business, losing one major award isn’t just a revenue hit—it can throw off fleet planning, base utilization, and staffing across an entire region.

6. Labor and supply chain challenges persist

Operationally, Bristow has also faced the unglamorous realities of aviation logistics. The company has said it expects spare parts shortages affecting the Sikorsky S-92 to last at least until the end of the year, and supply chain issues have left significant portions of the S-92 fleet unserviceable while waiting on critical parts. Over time, that pressure can force fleet shifts and constrain capacity in ways that are hard to model from the outside.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

If you follow Bristow, two KPIs tell you whether the story is getting better—or reverting to type.

1. Fleet Utilization Rate

Utilization is the heartbeat. It measures how much of the fleet’s available flying is actually sold. When utilization rises, pricing power and margins tend to follow. When it falls, the fixed costs stay put and the math gets ugly quickly. Management regularly discusses it on earnings calls.

2. Government Services Revenue as Percentage of Total

This is the simplest proxy for diversification. A higher mix of government services generally means more stable cash flows that don’t swing with crude. UKSAR2G moved the mix in the right direction; the next test is whether Bristow can win more long-duration, government-backed work.

A useful secondary indicator: offshore wind revenue growth. It’s still small in the context of the whole company, but the direction—and the pace—matters for whether “VTOL as infrastructure” becomes substance instead of branding.

X. Epilogue: Lessons & Reflections

The Bristow story is, in many ways, a case study in how industrial services companies break—and how a few manage to rebuild.

Lesson 1: Cyclicality is always underestimated—until it isn’t

At the top of a boom, downturns feel like short interruptions. From 2010 to 2014, oil around $100 a barrel made aggressive expansion look prudent, even conservative. Then the crash came, and what followed wasn’t a bad quarter or a rough year. It was a long stretch where offshore spending stayed depressed and the industry was forced into years of caution and under-investment. Business models built for the peak rarely survive a prolonged trough.

Lesson 2: Leverage doesn’t just amplify returns. It amplifies fragility.

Debt-funded growth is intoxicating when utilization is high and contracts are rolling in. But in fixed-cost, capital-heavy businesses, leverage turns a demand shock into a solvency crisis. Bristow didn’t fail because it forgot how to fly. The aircraft kept operating safely. It failed because the balance sheet couldn’t endure the revenue the market was now willing to provide. The investor question to ask is always the ugly one: what happens if revenue drops sharply and stays down for years?

Lesson 3: Chapter 11 can reset the math—even if it destroys the equity

For legacy shareholders, Bristow’s 2019 bankruptcy was a wipeout. But for the operating company—the people, the contracts, the aircraft, the reputation—Chapter 11 was a way to cut obligations down to something survivable. Bristow filed in May 2019 and emerged in October, with a restructured balance sheet that allowed it to keep flying and start rebuilding. The enterprise that came out was fundamentally healthier than the one that went in.

Lesson 4: Diversification is easy to promise and hard to win

Every commodity-exposed operator talks about reducing dependence on the cycle. Bristow had to actually do it—by bidding, winning, and then executing on work that looks nothing like oil crew change. Government services, in particular, demanded credibility, compliance, and consistent performance under scrutiny. The UKSAR2G contract wasn’t a gift. It was won in competition, including against CHC.

Lesson 5: Brand and capability show up on the scoreboard

In 2006, Offshore Logistics rebranded as The Bristow Group—an American company adopting the name of a British acquisition. That’s unusual, and it says something. “Bristow” carried a reputation built over decades in the North Sea and other high-consequence environments. In this business, where customers buy safety systems and operational trust as much as they buy flight hours, that kind of brand equity isn’t marketing. It’s an asset.

The Future Question

So can Bristow navigate the energy transition?

The company is trying to straddle two worlds: serving traditional offshore hydrocarbon production while building a foothold in renewables and government services. It has the aircraft, people, and maintenance backbone to do either. But the uncertainty is real. If offshore oil stays strong, Bristow’s core business remains valuable. If oil turns down again and offshore wind grows more slowly—or becomes a low-margin, fiercely contested market—the pressure returns.

That’s what makes the ticker VTOL such a sharp symbol. It’s a bet that Bristow’s future is broader than oil: vertical flight as infrastructure, across missions and industries. Whether it pays off will depend on execution, the pace of market change, and how transferable seven decades of offshore operating muscle memory really is.

Alan Bristow, who died in 2009, might not recognize the company that carries his name today. The Persian Gulf beachhead is history. The North Sea is still important, but it’s no longer the whole story. And the biggest, most visible contract isn’t moving oil workers—it’s flying search-and-rescue for the UK.

But the core would feel familiar. The flying is still done in unforgiving conditions. The safety standards are still non-negotiable. And the mission—reliable vertical transportation where failure isn’t an option—hasn’t changed.

That continuity may be Bristow’s most durable asset. Ownership structures change. Markets swing. Technologies evolve. But the need to move people and equipment to difficult places—offshore platforms, remote installations, disaster sites—doesn’t go away.

Bristow survived oil crashes, corporate reshuffles, bankruptcy, and a global pandemic. It entered 2026 leaner, more diversified, and more financially conservative than the company that nearly broke in 2019. Whether that’s enough to thrive is still an open question.

For investors, the question isn’t whether Bristow has real capabilities—it does. The question is whether those capabilities are priced correctly against the risks, and whether management can keep the discipline that the last cycle forced upon it.

The offshore helicopter industry has spent years flying through turbulence. Bristow made it through. Now comes the harder part: proving it can do more than survive.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music