Vir Biotechnology: Engineering Antibodies to Fight Pandemics

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

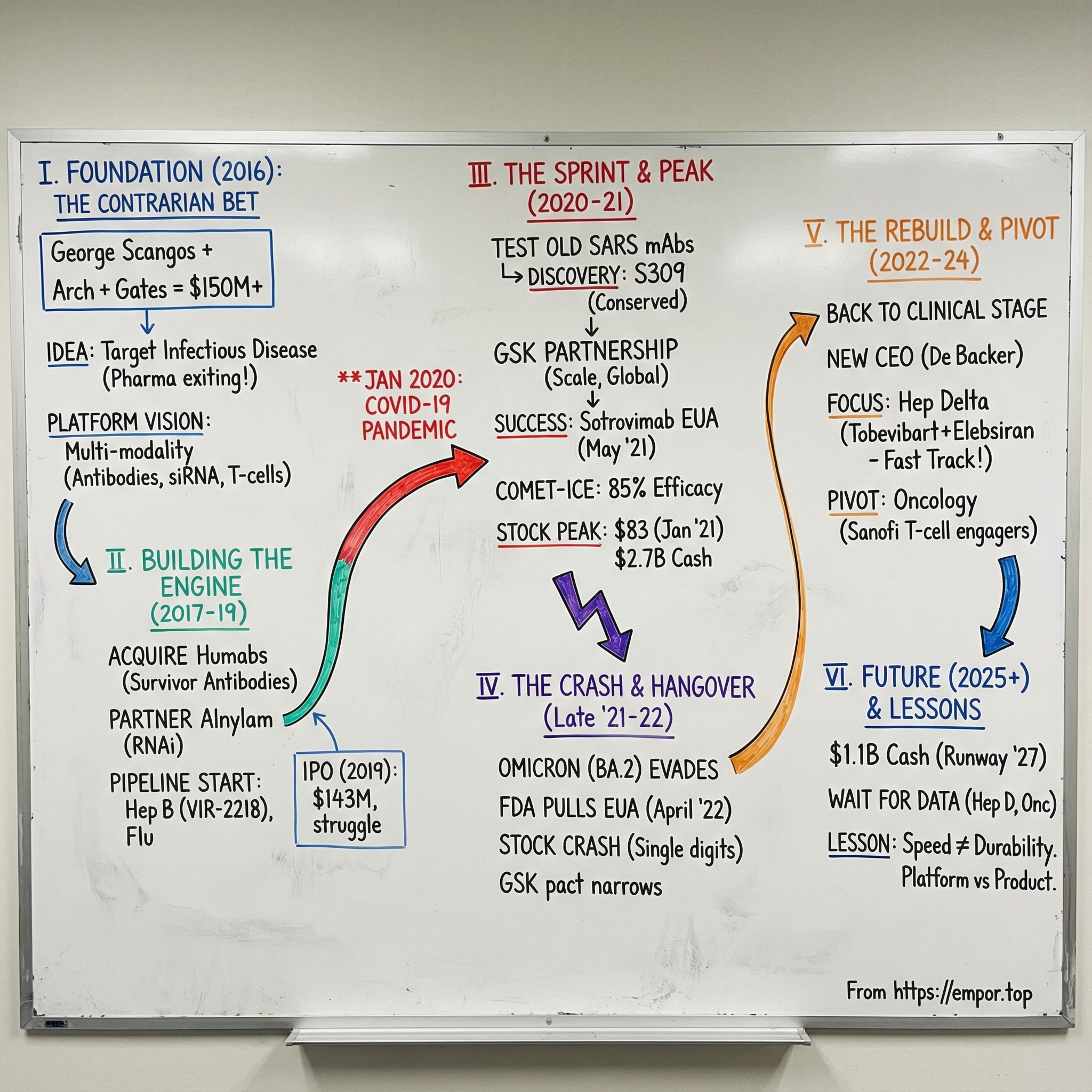

In January 2020, as early reports of a mysterious pneumonia began leaking out of Wuhan, a small biotech in San Francisco was about to get yanked onto the biggest stage in modern medicine. Vir Biotechnology was only four years old. It had been built around a contrarian idea: go after infectious diseases that big pharma had largely walked away from. Within weeks, that thesis would be put to the ultimate test as Vir raced to help develop one of the first monoclonal antibody treatments for COVID-19.

This is a story about timing and science colliding with the brutal economics of drug development. It’s about a veteran biotech CEO who didn’t have to do another hard thing, but chose to build in the least fashionable corner of pharma. It’s about a platform that looked prescient when the world needed speed—and then got humbled by the oldest rule in infectious disease: viruses evolve.

At the center is George Scangos. He’d already run major biopharma companies, including Biogen from 2010 to 2016 and Exelixis from 1996 to 2010. At Vir, he became the founding President and CEO, leading the company through its sprint from startup to pandemic responder and into the tougher, quieter years that followed.

The question we’re really answering is: how did a company founded in 2016 become a key player in the COVID-19 response—and then navigate what happens when the emergency ends? To get there, we’ll unpack what “platform biotech” actually means, how venture-backed science turns into a public company story, how partnerships with giants like GSK get structured, and why infectious disease is simultaneously one of the most important categories on earth and one of the hardest to build a business around.

Vir raised more than $600 million privately, then brought in another $143 million in its 2019 IPO. It helped bring to market an antibody drug for COVID-19 and an Ebola antiviral. At its peak, Vir had $2.7 billion in the bank, partnerships with GSK and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, and a pipeline aimed at hepatitis B and D, influenza, and HIV.

And then the hangover hit. Vir’s stock topped out at an all-time high closing price of $83.07 on January 27, 2021. Today it trades in the single digits—less a verdict on effort than a reminder of how quickly pandemic demand can vanish, and how punishing the market can be to clinical-stage biotechs once the spotlight moves on.

For founders, operators, and investors, Vir is a case study in platform ambition, single-product dependency, regulatory fast lanes versus normal timelines, and what it takes to survive the biotech winter that followed the COVID boom.

II. The Scientific & Market Context: Why Infectious Disease Biotech Was Ignored

To understand why Vir’s founding was so contrarian, you have to rewind to what pharma and biotech looked like in the years leading up to 2016. Infectious disease wasn’t just out of fashion. In many boardrooms, it was effectively written off.

The warning sign was antibiotics. Starting in the 1990s, people began talking about the “dry antibiotic pipeline,” as fewer novel drugs made it through discovery and approval. In the early 2000s, large pharmaceutical companies started exiting the space. By the mid-2010s, it wasn’t a trend anymore. It was a retreat.

At the same time, capital flowed in the opposite direction. Over the second half of the 20th century, investors and pharma companies steadily shifted toward non-communicable, chronic diseases—especially cancer and autoimmune conditions. The underlying belief was simple and disastrously convenient: modern medicine had basically solved infectious disease, so the real growth would be in areas where patients take therapy for months, years, or a lifetime.

The economics reinforced that story. Antibiotics are short-course treatments. You take them for days or weeks, and ideally you stop. Chronic-disease therapies, by contrast, can become recurring revenue streams. One widely cited analysis from the early 2000s found that an injectable antibiotic could be several times less profitable than an oncology drug. Even if you made a great antibiotic, stewardship programs and resistance concerns would often push doctors to hold it back—meaning the better society behaved, the worse your commercial outcome looked.

By the mid-2010s, the data reflected the sentiment. Antibacterials made up only a small slice of venture funding. The share of antibiotics among new FDA approvals had fallen sharply compared to decades earlier. Infectious disease had become the category that everyone agreed was important—right up until it came time to allocate budgets.

And then, in 2018, the retreat turned into a rout. Allergan, Sanofi, and Novartis pulled back from the space, with Sanofi transferring its infectious disease R&D unit to Evotec. That left only a few major players—like Roche (and Genentech) and GSK—with meaningful ongoing research footprints.

Meanwhile, the world kept firing flares into the night sky. SARS in 2003. H1N1 in 2009. MERS in 2012. Ebola’s devastating West African outbreak from 2014 to 2016. Zika sweeping through the Americas in 2015 and 2016. Each one was a reminder that pandemics weren’t medieval history—they were a modern systems risk. But the incentives hadn’t changed. Preparedness had largely been outsourced to the market, and the market was walking away.

This is what people mean when they call it a market failure. The societal value of effective infectious-disease treatments is massive, but the private returns are often minimal. Some analyses went so far as to argue that, on a traditional net present value basis, an antibiotic could be worth close to zero. That’s not a scientific judgment. It’s a business model verdict.

And yet, right as the business case collapsed, the science got interesting.

Monoclonal antibodies had matured from a promising modality into an increasingly reliable toolkit. Researchers were getting better at finding potent antibodies from survivors—people whose immune systems had already beaten an infection—then engineering those antibodies into therapies that could deliver immediate protection. It was “passive immunity”: instead of waiting weeks for a vaccine to teach your body what to do, you could borrow a ready-made immune response, right now.

So by 2016, infectious disease sat at a strange intersection: economically abandoned, repeatedly proven important, and newly enabled by technology. For the few people who understood that combination, the opportunity wasn’t subtle.

What it needed was a team willing to bet on it—plus someone credible enough to convince everyone else to fund the bet.

III. The Founding Story: George Scangos, Arch Venture Partners, and the Dream Team

Vir Biotechnology’s origin story starts with someone who, on paper, had every reason to be done. George Scangos was already a made man in biotech. He’d run Biogen for six years and left at the end of 2016. During his tenure, Biogen’s sales more than doubled, rising from $4.7 billion in 2010 to $10.8 billion. He pulled off a major restructuring, divested the Idec cancer drug division, refocused R&D on neurology and hematology, and oversaw the rollout of six new drugs, including a blockbuster multiple sclerosis therapy.

If he’d chosen to retire at that point, nobody would have blinked.

But Scangos didn’t come back to chase the most fashionable categories—the ones drawing the lion’s share of capital. He came back to bet on infectious disease, the very area the industry was walking away from.

Part of what made that believable was where he came from. Before industry, Scangos was an academic: a professor of biology at Johns Hopkins University. On the way into science, he took an unconventional route—driving out to the University of Massachusetts to explore graduate school and, despite never having taken a microbiology course, ending up earning a PhD in microbiology there in 1977 with Albey Reiner. He later did a postdoctoral fellowship at Yale University with Frank Ruddle, where their work helped create the first transgenic mouse.

That background matters because it points to a pattern: Scangos wasn’t someone who built a career by following consensus. He built it by leaning into hard scientific problems and making big calls when others hesitated.

Vir Biotechnology was established in January 2016 and headquartered in San Francisco, California. It was initially seeded by ARCH Venture Partners, with Robert Nelsen playing a key role. From the start, it wasn’t a lone-founder story—it was built with heavyweight scientific founders, including Klaus Frueh, Louis Picker, Jay Parrish, Larry Corey, and Phil Pang.

The thesis was clear and unusually ambitious for day one: build a platform technology company, not a one-drug wonder. Vir set out to bring multiple approaches under one roof—antibodies, T cells, siRNA, and innate immunity—to tackle a wide range of infectious diseases. That breadth wasn’t an accident; it was the point. If infectious disease was going to be unpredictable—new outbreaks, shifting variants, pathogens that mutate around you—then the company needed more than a single shot.

To fund that kind of scope, Vir launched with serious backing: over $150 million in initial funding commitments from ARCH Venture Partners and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, among others. For the time, that was a striking amount of capital to pour into infectious disease, a category that had been pushed aside in favor of hotter areas like cancer and gene therapy.

The Gates Foundation’s involvement also sent a signal about intent. This wasn’t being framed as purely a commercial play. The foundation had spent years focused on global health problems the market consistently under-served. In Vir, it saw a vehicle to go after diseases like hepatitis B, HIV, and tuberculosis—massive burdens that killed millions but often struggled to attract sustained pharma investment.

As Scangos put it at the time: “The opportunity to lead Vir is one I could not pass up.”

And that’s what made the founding round remarkable. Yes, $150 million was big. But what it really represented was conviction: a belief that pandemic risk was being systematically underestimated, and that the scientific toolkit—especially immune-based technologies—had finally matured enough to do something meaningful about it.

They’d be proven right much sooner than anyone expected.

IV. Building the Platform: The Technology Stack

Vir’s strategy started with a deceptively simple belief: the best antibodies already exist in nature. If someone survives a serious infection, their immune system has already done the hardest part—learning how to neutralize a dangerous pathogen. Vir’s job was to find those rare, powerful antibodies, then turn them into engineered medicines that could be manufactured at scale.

That idea became real in September 2017, when Vir acquired Humabs BioMed SA, a Swiss company built to do exactly this. Humabs specialized in discovering and developing fully human monoclonal antibodies for serious infections—antibodies that had already been “tested” by the human immune system in the wild. The acquisition didn’t just bring a team and a lab. It brought a discovery platform, antibody engineering capabilities, and a pipeline of more than a dozen development candidates, including preclinical programs for hepatitis B, RSV/metapneumovirus, Zika, and dengue.

The Humabs approach was elegant and ruthlessly practical. Using its CellClone technologies, Humabs isolated human monoclonal antibodies from memory B cells and plasma cells taken from convalescent patients—people who had recovered. The technology traced back to the laboratory of Professor Antonio Lanzavecchia at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine in Switzerland, one of the world’s top centers for antibody research.

Over time, the antibodies discovered and developed through this platform became foundational to Vir’s infectious-disease ambitions. From Ebola to COVID-19, the company’s ability to translate immune responses into medicines helped build the experience—and, importantly, the financial strength—to keep pushing a broader pipeline forward.

But Vir wasn’t trying to win with antibodies alone. Around the same period, it announced a set of agreements spanning Humabs, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Visterra, and four leading academic research institutions. The message was clear: this wasn’t a single-program biotech. It was a multi-modality engine.

The Alnylam partnership was especially strategic. Alnylam pioneered RNA interference, or RNAi—a way to use small interfering RNA molecules to silence specific genes. For hepatitis B, where the virus can integrate its DNA into liver cells, RNAi offered a promising way to shut down viral protein production in a way that traditional antivirals often couldn’t.

All of this required real capital. By this stage, Vir had secured more than $500 million in financing to build out a pipeline, a technology stack, and a global footprint. The aim was straightforward, even if the execution wasn’t: integrate the best innovations in science and medicine to transform care for people facing serious infectious diseases.

Vir organized its early efforts into three broad arenas: chronic infections like hepatitis B, tuberculosis, and HIV; respiratory diseases like influenza, RSV, and metapneumovirus; and health-care acquired infections.

This is why the “platform” framing matters so much in biotech. Drug development fails constantly. If you only have one clinical asset and it doesn’t work, the company can crater overnight. A platform can’t remove clinical risk—but it can spread your bets across multiple shots on goal, across multiple diseases, using tools that can be reused and improved over time.

Vir also extended its reach through academia. At Stanford University, it licensed artificial intelligence technology designed to mine gene expression data for early diagnostic predictions and target discovery. At Harvard University, it entered a five-year strategic research alliance to foster collaboration and fund innovative infectious-disease research projects—while retaining exclusive access to negotiate licenses.

Put all of that together, and by 2019 Vir had assembled something unusually complete for a young company: an antibody discovery engine through Humabs, RNAi capabilities through Alnylam, T cell engineering expertise, and academic partnerships feeding future innovation.

The platform was ready. What it still needed was the same thing every platform company needs: a defining clinical proof point—or an unexpected crisis that would force the world to find out what it could really do.

V. The First Act: Hepatitis B and HIV Programs (2016-2019)

Before COVID-19 turned Vir into a household name in biotech circles, the company was doing the slow, methodical work that defines most drug development: picking its first real battles, building clinical muscle, and trying to prove the platform in chronic infectious diseases. Hepatitis B was the flagship.

The need was enormous. More than 290 million people live with chronic HBV worldwide, with the majority of cases concentrated in Asia-Pacific and Africa. For a company willing to stay in the fight, that wasn’t just a public-health problem—it was a long-term opportunity.

And scientifically, hepatitis B was still unfinished business. Hepatitis C had its breakthrough moment in 2014, when new antivirals made functional cures a reality. Hepatitis B didn’t follow that script. Existing therapies produced low rates of HBsAg seroclearance, and a sterilizing cure—eliminating all viable HBV replication templates, including covalently closed circular DNA and integrated HBV genome—was not achievable with approved treatments.

Vir’s plan reflected its platform mindset: don’t bet on one mechanism, stack them. A key early piece was VIR-2218, developed through the Alnylam partnership. It became the first siRNA in the clinic to include Enhanced Stabilization Chemistry Plus (ESC+) technology, designed to improve stability, minimize off-target activity, and potentially increase the therapeutic index. It was also the first program from the Vir-Alnylam collaboration to reach human trials. By September 18, 2019, 37 healthy volunteers had received VIR-2218 and 12 had received placebo.

In parallel, Vir placed another big bet in respiratory disease: influenza. VIR-2482 was an intramuscularly administered influenza A-neutralizing monoclonal antibody. In August 2019, Vir initiated dosing in a Phase 1/2 trial. In vitro, VIR-2482 had shown coverage across all major influenza A strains that have arisen since the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. The vision was bold: something that could provide protection that outperforms seasonal vaccines and can potentially be used year after year because of broad strain coverage.

With multiple programs moving into the clinic, Vir did what ambitious platform biotechs eventually have to do: it went to the public markets.

In October 2019, Vir priced its initial public offering of 7,142,858 shares at $20.00 per share, for gross proceeds of about $142.9 million before underwriting discounts, commissions, and offering expenses. The shares began trading on The Nasdaq Global Select Market on October 11, 2019 under the ticker “VIR.”

The reception was not a celebration. Vir priced at the bottom end of expectations, which was also an unwelcome outcome for SoftBank’s Vision Fund, which owned 21% of the company. The IPO valued Vir at $2.2 billion, but the stock slid hard in its first day of trading—opening at $16.15 and closing at $14.02—cutting the company’s market value to roughly $1.5 billion.

Vir said it intended to use the net proceeds to finish its ongoing VIR-2218 Phase 1/2 trial and related manufacturing, advance VIR-3434 through its planned Phase 1 trial, and continue the ongoing Phase 1/2 work for VIR-2482.

So by late 2019, Vir was in a familiar place for a newly public biotech: well funded, scientifically ambitious, and still unproven where it mattered most. The stock traded below the IPO price. Investors remained skeptical about infectious disease. Vir had time, talent, and technology—but no approved products, and years of development ahead.

Then the world changed.

VI. Inflection Point #1: COVID-19 and the Scramble (January-March 2020)

In January 2020, the reports from Wuhan started to harden from rumor into reality. A novel coronavirus was spreading fast. Patients were developing severe pneumonia. And the early signal—before most of the world wanted to accept it—was that this thing was highly transmissible.

For most biotech companies, COVID-19 was pure disruption. Trials would slow or stop. Labs would get constrained. Markets would panic. But for Vir, built explicitly around the idea that infectious disease emergencies don’t wait for your five-year plan, this was the moment where the platform either proved itself or got exposed.

Vir’s scientists quickly latched onto a key technical advantage: SARS-CoV-2 looked a lot like SARS-CoV-1, the virus behind the 2003 SARS outbreak. And thanks to Humabs, Vir already had something rare sitting on the shelf—antibodies isolated from people who’d survived SARS.

So they went straight to the obvious question: could any of those old SARS antibodies neutralize the new virus?

Vir’s team obtained SARS-CoV-2 samples and began running them against antibodies recovered from those earlier SARS-CoV-1 survivor blood samples, essentially stress-testing their library against the new threat. The goal wasn’t just to find an antibody that worked. It was to find one that worked across both viruses.

Because if an antibody could hit SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2, it likely wasn’t targeting some flimsy, fast-mutating surface detail. It was targeting something conserved—an evolutionarily constrained part of the virus that can’t easily change without breaking itself. And if you’re building a drug in the middle of a rapidly spreading pandemic, that’s exactly the kind of bet you want to make.

That insight started to crystallize—literally—in April 2020. At Vir’s request, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory used X-ray crystallography to study how these antibodies bound to SARS-CoV-2 at the molecular level. The data helped narrow the field, and Vir ultimately converged on a single candidate: S309.

This was the platform thesis in action. In a matter of weeks, Vir had gone from hearing about a new pathogen to identifying a credible therapeutic candidate. But finding an antibody is not the same thing as getting a medicine into patients. Antibody development at global scale—manufacturing, trials, regulators, distribution—takes capabilities that a clinical-stage biotech rarely has on its own.

So Vir did what good platform companies do when the moment demands it: it partnered.

In April 2020, Vir and GSK entered a collaboration to research and develop solutions for coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2. The partnership was designed to advance antibody candidates VIR-7831 and VIR-7832, and to support additional work aimed at future coronavirus outbreaks.

For Vir, it was a force multiplier. GSK brought manufacturing capacity, regulatory expertise, and worldwide commercial infrastructure—everything required to move from promising biology to real-world deployment. Vir brought the engine: its monoclonal antibody platform and the early scientific lead.

Together, they refined S309 into what became sotrovimab. Sotrovimab was engineered with an Fc LS mutation (M428L/N434S) to enhance binding to the neonatal Fc receptor and extend half-life.

The pace was extraordinary. In roughly three months, the story went from the identification of a novel pathogen, to a viable antibody candidate, to a partnership with one of the world’s largest pharma companies, to a drug engineered for development.

In 2020, Vir moved quickly, leveraging its antibody platform to explore multiple monoclonal antibodies as potential therapeutic or preventive options for COVID-19. Sotrovimab was the first SARS-CoV-2-targeting antibody Vir advanced into the clinic.

And even then, the world’s constraints showed up immediately in the supply chain. At launch in May 2021, sotrovimab’s active pharmaceutical ingredient was produced by WuXi Biologics in China, then shipped to a GSK plant in Parma, Italy to be processed into finished product. A pandemic drug, built through a pandemic-era global relay race.

Investors noticed what was happening. Vir had gone into 2020 as a newly public, still-unproven infectious disease platform trading below its IPO price. As the COVID response snapped into focus, the market began to re-rate the company—not as a speculative science project, but as a rare biotech that had been built for exactly this kind of moment.

VII. The Golden Era: Sotrovimab Success & EUA (2020-2021)

COMET-ICE—short for COVID-19 Monoclonal antibody Efficacy Trial, Intent to Care Early—became the proving ground for Vir’s platform thesis. This was the moment where “we can find antibodies fast” had to turn into “we can keep people out of the hospital.”

The Phase 3 study focused on the patients everyone was most worried about: high-risk people with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, early in their infection, before things tipped into the dangerous phase. It was an ongoing, multicenter, double-blind trial. Nonhospitalized symptomatic patients with at least one risk factor for disease progression were randomized 1:1 to receive a single intravenous infusion of sotrovimab (500 mg) or placebo. The primary endpoint was brutally simple: by day 29, how many had progressed to hospitalization longer than 24 hours or death?

The interim results landed like a thunderclap. Sotrovimab drove an 85% reduction in hospitalization (more than 24 hours) or death versus placebo—the trial’s primary endpoint.

In the prespecified interim analysis of 583 patients, just 3 patients in the sotrovimab arm progressed to hospitalization or death, compared with 21 patients in the placebo arm. In the placebo group, several patients ended up in intensive care, and one died by day 29.

The Independent Data Monitoring Committee didn’t just say, “looks promising.” It recommended stopping enrollment because of profound efficacy. Not for safety. Not for futility. For the best reason there is: the benefit was strong enough that continuing to give placebo to high-risk patients was no longer defensible.

Regulators moved quickly. In May 2021, the FDA granted an Emergency Use Authorization for sotrovimab—an investigational single-dose monoclonal antibody—for treating mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in adults and pediatric patients aged 12 and older (weighing at least 40 kg), with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and at high risk of progression to severe disease, including hospitalization or death.

Then came the scale-up—where most biotech success stories get stuck. But this is where the GSK partnership mattered. GSK and Vir announced U.S. government contracts totaling about $1 billion to purchase sotrovimab. The U.S. government agreed to buy 1.5 million doses, priced at $2,100 per dose. In Europe, GSK and Vir signed a joint procurement agreement with the European Commission to supply up to 220,000 doses.

For Vir, the financial and reputational shift was immediate. It went from a cash-burning clinical-stage biotech to a company with a globally deployed product and meaningful revenue flowing through government agreements. And because of the partnership structure, Vir could participate in the upside while leaning on GSK for manufacturing, distribution, and the operational heavy lifting of serving the world in real time.

The market treated it like a coronation. Vir’s stock hit an all-time high closing price of $83.07 on January 27, 2021.

George Scangos summed up the moment like a CEO who knew exactly what was at stake: “Our distinctive scientific approach has led to a single monoclonal antibody that, based on an interim analysis, resulted in an 85% reduction in all-cause hospitalizations or death, and has demonstrated, in vitro, that it retains activity against all known variants of concern.”

From the outside, it looked like the win was complete. Vir had proven it could respond to a pandemic, that its antibody platform could deliver in the clinic, and that it could partner with a pharma giant to get a drug into patients around the world. And if it could do that for COVID-19, why wouldn’t the same machine work for hepatitis B, influenza, and everything else in the pipeline?

But infectious disease has a habit of pulling the rug out from even the cleanest scientific stories.

VIII. Inflection Point #2: The Omicron Crash (Late 2021-2022)

Omicron arrived in late November 2021, first identified in South Africa. Within weeks it was everywhere—outcompeting prior variants with a speed that made Delta look slow. And as Omicron took over, a brutal reality set in: sotrovimab was starting to lose its edge.

By early 2022, the problem narrowed to a specific version of Omicron: BA.2. GSK and Vir reported that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration amended the Emergency Use Authorization fact sheet for sotrovimab after reviewing the totality of available evidence, including new live-virus data generated by Vir. The FDA’s conclusion was stark: it was unlikely that the sotrovimab 500 mg dose would be effective against Omicron BA.2.

On April 5, 2022, the FDA revised the EUA again, and this time it carried teeth. The revised authorization no longer allowed providers to administer sotrovimab anywhere in the United States. The decision leaned on CDC surveillance showing BA.2 had become the dominant strain in the country.

This wasn’t a gentle phase-out. It was an off switch.

And the whiplash was intense. Sotrovimab’s EUA had been granted off a Phase 3 trial showing an 85% reduction in hospitalization or death. It had been used worldwide, including broadly in the U.S. under emergency authorization. Then, in a matter of months, it went from a marquee pandemic therapy to a drug regulators said no longer made sense to deploy.

The irony was hard to miss. Vir had intentionally gone after an antibody that targeted a conserved region of the virus—the whole bet was that it would hold up as variants emerged. And for a while, it did, retaining in vitro activity against multiple variants of concern. But Omicron was different. With an unusually large number of mutations in the spike protein, it managed to evade even antibodies chosen for durability.

The business impact followed the biology. The GSK-Vir collaboration, announced in April 2020, had produced an FDA emergency authorization roughly a year later. But the commercial window ended up being short. Vir’s stock, which had peaked above $80 in early 2021, fell into the single digits. At one point, the company’s 52-week low hit $4.16.

The partnership also tightened. GSK later narrowed its COVID-19 research collaboration with Vir, retaining rights only to sotrovimab and another experimental treatment under an amended agreement. Vir, meanwhile, would continue efforts to discover and advance next-generation coronavirus solutions independently or with other partners.

Then came the macro headwind. The biotech winter of 2022—driven by rising interest rates and a broad selloff in speculative assets—was the worst possible backdrop for a company suddenly back to being a cash-burning clinical-stage biotech. Vir found itself in a particularly unforgiving spot: its main commercial product had been sidelined, its pipeline programs were still years from approval, and public markets had no patience for “wait for the next readout.”

So what went wrong? It wasn’t one thing—it was the combination. Vir had become heavily dependent on a single product for revenue. When sotrovimab fell, the revenue fell with it, leaving burn rate exposed. The next wave of antibodies wasn’t ready in time. And underneath all of it was the oldest rule in infectious disease: the pathogen gets a vote. Viruses evolve, and what works today can stop working tomorrow.

IX. The Rebuild: Refocusing on Core Programs (2022-2024)

After Omicron, Vir had to do the least glamorous thing in biotech: go back to being a normal clinical-stage company. No emergency authorizations. No once-in-a-generation demand shock. Just a pipeline, a cash pile that suddenly mattered again, and years of trials between promising science and real approvals.

The market didn’t wait around. With sotrovimab no longer authorized in the U.S. as new variants took over—and with the rest of the portfolio still unproven in late-stage studies—Vir’s stock stayed far below its early-2021 highs. The pandemic halo was gone. What remained was the underlying question investors always ask: what’s next that actually works?

Vir also went through a leadership transition. George Scangos, the high-profile CEO who had led Vir from its earliest days through the pandemic sprint, retired in April 2023. On April 3, he stepped down and Marianne De Backer took over as CEO. De Backer came from Bayer, where she led business strategy and development in the pharmaceutical division, after building up its gene and cell therapy efforts. Before Bayer, she spent more than two decades at Johnson & Johnson. Scangos stayed on in an advisory role through June 2 and remained on Vir’s board afterward.

De Backer inherited a company mid-pivot: from pandemic responder back to pipeline builder.

The clearest place to focus was hepatitis B. Vir continued to advance its HBV and HDV portfolio and shared new data at the EASL Congress. In a late-breaker oral presentation from a Phase 2 trial, Vir reported that when VIR-2218—an investigational small interfering RNA—was given for 24 or 48 weeks on top of up to 48 weeks of pegylated interferon alpha, 16% of participants achieved sustained HBsAg loss 24 weeks after the end of treatment.

VIR-2218 also produced dose-dependent reductions in hepatitis B surface antigen. In the 200 mg group, the greatest mean HBsAg reduction at Week 20 was 1.65 log IU/ml. Vir said the Phase 2 results supported further development of VIR-2218 as a potential therapy for chronic HBV infection.

But refocusing isn’t just a slide deck. It’s cuts.

Vir announced an organizational realignment designed to concentrate resources, including phasing out programs in influenza and COVID-19, as well as the company’s T cell-based viral vector platform. The plan also included a workforce reduction of about 25%, or roughly 140 employees. Vir expected to end 2024 with approximately 435 employees—down by about 200 from its peak headcount in the second quarter of 2023.

The company also projected about $50 million in cost savings through the end of 2025 from winding down those programs, with the intent to substantially reinvest those savings into newly licensed programs from Sanofi after the transaction closed.

This was biotech survival in its most honest form: when the easy story ends, you narrow the aperture. Vir’s original platform ambition didn’t disappear—but it tightened into a smaller number of higher-conviction shots.

X. Current State & Recent Developments (2024-Present)

By late 2025, Vir had emerged from the post-Omicron fallout as a more focused clinical-stage company, with two main bets: hepatitis delta (and B) on the infectious-disease side, and oncology T-cell engagers on the biotech-platform side.

Management framed the reset in unusually direct terms: “We enter 2025 with a robust financial position to support our key strategic priorities, including $1.10 billion in cash, cash equivalents and investments and a cash runway into mid-2027.”

On hepatitis delta, Vir’s next major swing was the Phase 3 ECLIPSE registrational clinical program in chronic hepatitis delta, which the company said was on track to begin in the first half of 2025. Tobevibart and elebsiran in chronic hepatitis delta picked up a string of regulatory tailwinds: U.S. FDA Breakthrough and Fast Track designations, plus EMA PRIME and Orphan Drug designations.

Vir argued the underlying data supported the urgency. It said the investigational combination showed rapid and sustained virologic suppression, positioning it as a potential first-of-its-kind approach aimed at a critical unmet need in chronic hepatitis delta. And with multiple designations in hand, the company was clearly signaling it would pursue an expedited path where possible.

At the same time, Vir widened the story beyond viruses. The oncology expansion was a deliberate pivot: Vir signed an exclusive worldwide license agreement with Sanofi for multiple potential best-in-class clinical-stage T-cell engagers, along with exclusive use of the protease-cleavable masking platform Sanofi had acquired from Amunix Pharmaceuticals.

Vir said it was advancing multiple undisclosed dual-masked TCEs against clinically validated targets, with potential applications across a range of solid tumors. These preclinical candidates use the PRO-XTEN™ masking technology, paired with TCEs discovered and engineered using Vir’s antibody discovery platform—an attempt to carry the “platform” identity forward, just into a different therapeutic arena.

Marianne De Backer put the company’s posture succinctly: “2024 was a year of transformation for Vir Biotechnology as we successfully defined and executed on our renewed strategic direction, focusing our resources on our most promising programs in infectious diseases and oncology.”

Not everything was rebuilt in-house. Vir’s HIV efforts continued through partnerships, including its collaboration with the Gates Foundation on broadly neutralizing antibodies aimed at an HIV cure.

Financially, Vir continued to emphasize liquidity. As of June 30, 2025, it reported $892.1 million in cash, cash equivalents and investments, plus $95.2 million in restricted cash and cash equivalents.

The stock, though, told you what kind of company the market believed Vir had become. The latest closing price was 5.47, with a 52-week high of 14.45—less “pandemic hero” pricing, more “prove it again” pricing.

So if you’re evaluating Vir now, the question isn’t whether the company can move fast in a crisis. COVID already answered that. The question is whether this streamlined version of Vir can turn its platform into repeatable wins—first in hepatitis, and now in oncology—where the timelines are longer, the competition is brutal, and there’s no emergency authorizing your way past the usual grind.

XI. Business Model Deep Dive: How Platform Biotechs Work

To really understand Vir, you have to understand the strange business it’s in. A clinical-stage biotech doesn’t work like a normal company, because for most of its life it isn’t selling anything. It’s buying time—time in labs, time in manufacturing slots, and above all, time in clinical trials—while trying to turn uncertainty into proof.

The basic arc is discovery, development, and then, only if everything goes right, commercial.

Discovery is where you find a candidate that looks like it can do something meaningful in biology. Development is where you try to prove it in humans, step by step: Phase 1 tests safety, Phase 2 looks for early signals the drug works, and Phase 3 is the big, expensive attempt to show real efficacy at scale. Only after a successful Phase 3 can a company ask regulators for approval. And only after approval can you start building durable, predictable revenue.

That timeline drives the entire capital structure. For years—often a decade or more—biotechs spend heavily with little or no product revenue. They survive on investor funding because investors are effectively underwriting the probability that one or more programs will eventually work. That’s why these companies raise so much money, and why late-stage clinical trials loom so large: a single pivotal study can cost well into the nine figures.

This is also why partnerships matter so much, and why they’re often existential rather than optional. The GSK-Vir relationship is a clean example of how the economics usually work. In an amended version of their agreement, Vir retained the ability to advance next-generation solutions coming out of certain collaborative coronavirus vaccine and antibody programs, with Vir paying GSK tiered low- to mid-single digit royalties.

That structure is common in biotech: upfront payments when the deal is signed, milestone payments if specific clinical or regulatory goals are hit, and royalties if a product reaches the market and sells. For the biotech, a partner can bring cash, credibility, development expertise, and manufacturing capacity. For big pharma, the trade is access to innovation without having to invent everything internally.

Regulatory pathways also shape the business model, and not all approvals are created equal. The route Vir took with sotrovimab—the Emergency Use Authorization—was designed for speed in a public health emergency. It can get a therapy to patients fast, but it comes with built-in fragility. When the facts change, the authorization can change, too. Traditional approval through a full BLA (Biologics License Application) is slower, but it’s the route that typically supports a more stable commercial product life.

Then there’s manufacturing, which is its own bottleneck. Antibodies aren’t pills you can press by the millions on short notice. Sotrovimab, like other biologics, is made in living cells—specifically Chinese hamster ovary cells—and it can take roughly six months to produce. That long cycle time turns supply into a strategic constraint, especially when demand spikes unexpectedly, as it did during COVID.

Put all of this together and you get the appeal—and the trap—of the platform biotech thesis. If drug development is a probabilities game, then building a platform that can produce multiple shots on goal is a rational response. It’s diversification against a brutal base rate: around 90% of drugs that enter clinical trials never make it to approval. A platform can improve your odds by letting you reuse tools, data, and know-how across programs. But it also demands more capital, more operational complexity, and more patience—exactly the things the public markets tend to run out of right when you need them most.

XII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

To get a clear-eyed view of Vir’s position, it helps to step back from the drama of COVID and run two classic lenses: what the industry structure does to everyone in the space, and what—if anything—Vir can build that lasts.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-High. The barriers are real: you need serious capital, rare scientific talent, clinical and regulatory know-how, and years of execution before you have anything to sell. But biotech is also a machine that keeps producing new challengers. Venture funding seeds fresh startups, academic labs spin out new approaches, and big pharma can always decide a category is strategic again. In something like hepatitis B, new entrants show up regularly—with different mechanisms, new data, and sometimes genuinely better shots.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Clinical-stage biotechs lean heavily on outside partners, especially contract research organizations and contract manufacturers. And for biologics, manufacturing capacity is a constant choke point. You can have a great antibody and still be limited by who can make it, when, and at what scale. A good example came in January 2022, when Omicron started knocking out competing antibodies and demand for sotrovimab surged. Vir and GSK responded by adding manufacturing capacity, including working with Samsung Biologics in South Korea. It was a reminder that supply chain constraints can cap even a “winning” product.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High. In pharma, the biggest buyers—governments, insurers, pharmacy benefit managers—have leverage. Sotrovimab made this visible in real time: huge government procurement contracts, negotiated pricing, and demand that could turn on policy decisions as much as clinical data. More broadly, payers increasingly insist on evidence of value, and that pressure makes premium pricing harder to sustain.

Threat of Substitutes: Very High. This is the force that never goes away for Vir. In COVID, sotrovimab wasn’t just competing with other antibodies (like Regeneron and Eli Lilly). It was competing with vaccines for prevention and with small-molecule antivirals like Paxlovid and molnupiravir for treatment. Ultimately, the FDA withdrew authorization for all monoclonal antibodies used to treat COVID; only antivirals like Paxlovid, Veklury, and Lagevrio remained on the market. In hepatitis B, the substitute threat shows up differently: multiple companies are chasing functional cures using completely different approaches, so a “good” therapy can be quickly boxed in by a better one.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense. Vir is fighting in categories where the stakes are enormous and the competition is relentless. In hepatitis B, heavyweight players like GSK and Janssen Biotech (Johnson & Johnson) bring deep antiviral experience and global distribution. Meanwhile, focused biotechs like Arbutus Biopharma and Brii Biosciences push the frontier with narrower, faster-moving HBV programs. The result is a crowded race where differentiation matters and timelines are unforgiving.

Hamilton’s Seven Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: Limited. Scale helps in biologics manufacturing, but it doesn’t create winner-take-all outcomes. Multiple antibody or antiviral products can coexist—if they’re clinically competitive.

Network Effects: None. A drug doesn’t get better because more people use it. Outcomes are patient-by-patient.

Counter-Positioning: Moderate. Vir’s early bet—staying in infectious disease while big pharma backed out—was classic counter-positioning. COVID briefly flipped the table and pulled pharma attention back in. That made Vir’s advantage feel less permanent than it did in 2016.

Switching Costs: Low-Moderate. Doctors switch when the data changes. Patients switch when efficacy changes. Sotrovimab’s collapse during Omicron made this painfully obvious: when it stopped being the right answer, usage dropped fast.

Branding: Weak. In prescription drugs, brand matters far less than safety, efficacy, and guidelines. Clinical evidence wins.

Cornered Resource: Potentially Strong. This is the most plausible place Vir can be defensible. The Humabs antibody library, the institutional knowledge built from studying survivor immune responses, and the company’s antibody discovery and engineering expertise aren’t things a new entrant can replicate overnight. Humabs is widely recognized for its pioneering role in discovering, engineering, and advancing human monoclonal antibodies for infectious diseases, and its team has published extensively in major peer-reviewed journals including Science, Nature, and Cell.

Process Power: Developing. The promise of a platform is that it gets better with every program: faster discovery, smarter engineering, fewer dead ends, cleaner handoffs into development. Vir’s COVID response showcased speed. Whether that speed becomes repeatable advantage in hepatitis and oncology is still unproven.

The Verdict: Vir’s best shot at durable advantage is cornered resources—its antibody library, accumulated immune-response data, and specialized talent—and possibly process power if the platform produces repeatable wins. But the industry structure is brutal: intense rivalry, powerful buyers, and constant substitutes. Even with great science, infectious-disease biotech is a hard business.

XIII. The Investment & Founder Perspective: Lessons from Vir's Journey

Vir’s arc is a useful reality check for anyone building, operating, or investing in platform biotech. It shows what happens when big science meets the unforgiving mechanics of markets, regulation, and viral evolution.

For Founders:

The capital cushion matters. Vir didn’t start with a small seed round and a single lottery ticket. It launched with more than $150 million in initial funding commitments, enough to acquire Humabs, build real infrastructure, and run multiple programs in parallel. In biotech, companies often don’t fail because the idea was wrong; they fail because they run out of money before they can prove they’re right.

Speed can be a real advantage, but only if you’ve prepaid the cost. Vir’s COVID sprint looked like overnight success: a new virus appears, and within about three months there’s a major partnership and a credible therapeutic candidate moving forward. But the speed wasn’t magic. It came from having the Humabs discovery engine, academic relationships, and a build-versus-buy mindset already in place before the crisis arrived.

Single-product dependency is the quiet killer. Vir talked like a platform company—and in many ways, it was. But economically, it became heavily dependent on sotrovimab. When Omicron BA.2 made that product unusable in the U.S., the revenue disappeared and the company snapped back into “cash burn + clinical timelines” mode. Diversification isn’t just an R&D philosophy; it’s what keeps your business model from collapsing when biology changes.

Partnerships are accelerants, not free lunches. The GSK partnership is a perfect example of why founders partner: it helped sotrovimab reach patients at global scale. But the trade-offs are real—shared economics and less control. Under the revised agreement, Vir can advance certain next-generation coronavirus vaccine and antibody programs independently, but it will pay GSK low-to-mid single-digit royalties for sole rights to those previously shared programs.

Timing always includes luck. Preparation is controllable; the world is not. Vir built for infectious disease years before anyone expected a coronavirus pandemic. In 2020, that preparation met a once-in-a-century opportunity. You can’t schedule that moment—but you can build in a way that lets you capitalize on it if it arrives.

For Investors:

Valuing clinical-stage biotech is valuing uncertainty. These companies are essentially options on future approvals. Small changes in perceived probability of success, competitive landscape, or commercial window can swing valuations dramatically. Vir’s move from an $83 peak to single digits wasn’t a normal business cycle. It was the math of uncertainty repricing in public.

Biotech is catalyst-driven by design. The stock doesn’t move on quarterly “execution” the way a software company might. It moves on clinical readouts, regulatory actions, and partnerships. For Vir, that means watching things like Phase 3 hepatitis delta progress, hepatitis B combination therapy results, and whether the oncology programs translate from platform promise into human data.

Platforms don’t eliminate risk; they redistribute it. Platform companies can give you more shots on goal, but they demand more capital and patience, and they still need proof points that convert “capability” into approved products. Single-asset biotechs are simpler—and more binary. Vir built a platform, then learned the hard way what happens when the market treats you like a one-product company.

Management quality shows up most when the story breaks. “Having the opportunity to bring life-saving medications to patients around the world has been the greatest privilege of my career,” Scangos said in a statement. The COVID scramble and the post-Omicron reset were both stress tests. The throughline is that experienced leadership matters most when the company has to make painful choices: cut programs, preserve cash, and keep the core thesis alive long enough to earn another chance at proof.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case & Future Scenarios

The Bull Case:

Hepatitis delta is the clearest near-term prize. Vir’s tobevibart and elebsiran combination has picked up multiple regulatory designations that can accelerate development and signal how serious the unmet need is in chronic hepatitis delta. If the regimen can deliver functional cure rates that are meaningfully better than what’s available today, Vir has a shot at a real commercial product—not just promising data.

Hepatitis B is the bigger, long-game opportunity. The global chronic hepatitis B burden remains enormous, with roughly 296 million people infected worldwide. A true functional cure—one that lets patients stop lifelong antiviral therapy—would be a breakthrough for global health and, if achieved, a major business in its own right.

The platform has already shown it can perform under pressure. COVID-19 didn’t end the way Vir hoped, but the sprint still demonstrated something rare: the company can identify, engineer, and advance antibody therapies quickly when a new pathogen appears. In a world where infectious disease threats keep emerging, that muscle memory matters.

The balance sheet buys time. Management’s message has been consistent: “We enter 2025 with a robust financial position to support our key strategic priorities, including $1.10 billion in cash, cash equivalents and investments and a cash runway into mid-2027.” In biotech, time is a strategic asset—it’s what lets you run Phase 3 programs without immediately running back to the market.

Oncology also gives Vir a second act. The Sanofi T-cell engager licensing deal expands Vir beyond infectious disease, bringing in new modalities and new potential indications. It’s diversification, and it reduces the risk of the company being defined by any single disease area again.

And then there’s valuation. With the stock far below its pandemic-era highs—and, at times, trading below cash value per share—the market appears to be assigning very little value to the pipeline. If Vir delivers credible Phase 3 progress, the repricing could be meaningful.

The Bear Case:

The runway can shrink faster than it looks. “Mid-2027” sounds comfortable until you remember what Phase 3 costs. Vir’s Research and Development expenses in the second quarter of 2025 were $97.5 million. If spending stays elevated, the company could still find itself needing additional capital before the key readouts that would justify better terms.

Competition in hepatitis B is real and well-funded. GSK’s antisense oligonucleotide, bepirovirsen, developed with Ionis, is being pursued as a functional cure. And that’s just one example. Multiple players are chasing the same patient population with different mechanisms, and the winner won’t be decided by ambition—it’ll be decided by data.

Clinical trial risk is the tax everyone pays in biotech. The odds are brutal: around 90% of drugs that enter clinical trials never reach approval. Vir doesn’t have a deep bench of late-stage assets, so each major readout carries outsized weight. A Phase 3 miss wouldn’t just be disappointing—it could be existential for the stock.

The market backdrop hasn’t been friendly to small-cap biotech. Investor attention has shifted toward other sectors, and broad weakness in biotech compresses valuations and makes financing more difficult, even for companies with strong science.

And the platform thesis still needs a second proof point. Sotrovimab proved Vir could move fast, but it also showed how quickly infectious-disease success can evaporate when a virus evolves. Vir still has to demonstrate it can produce durable, approvable products in hepatitis—and translate its platform into oncology without years of false starts.

Finally, the commercial gravity of infectious disease hasn’t changed. The same economics that pushed big pharma out—pricing pressure, shorter treatment courses, and episodic demand—are still there. Even great medicines can be hard to turn into great businesses.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor:

For investors tracking Vir’s ongoing performance, two KPIs matter most:

-

Clinical trial enrollment and data readouts: The timeline for the Phase 3 ECLIPSE program, interim and final hepatitis data, and early oncology dose-escalation results will decide whether Vir’s reset is turning into real, approvable products.

-

Cash runway and quarterly burn rate: With $892 million in cash as of mid-2025 and quarterly operating expenses running around $100 million-plus, the path toward any future financing—and the leverage Vir has when it gets there—is worth watching.

XV. Epilogue: The Bigger Picture

Vir Biotechnology’s story is bigger than one chart on one ticker. It’s a lens on pandemic preparedness, on the weird economics of medical innovation, and on what it actually takes to keep infectious-disease progress moving when there isn’t an emergency on the front page.

Start with the uncomfortable truth: the market failed on preparedness. For decades, public health experts warned that a pandemic wasn’t a question of if, but when. Yet investment in infectious disease kept sliding. It’s not because the need disappeared—infectious threats never went away—it’s because the incentives didn’t line up. Deaths from infectious diseases fell dramatically after antibiotics were introduced at scale in the 1940s, and that success helped create a dangerous illusion: that we’d solved the problem. The risk is that this progress stalls, or reverses, unless the economics get re-imagined.

Vir was, from the beginning, a bet on that underpriced risk. COVID-19 validated the premise—and turned it into a once-in-a-generation commercial opportunity—but it also revealed the trap. In infectious disease, biology can erase your product’s advantage overnight. Viral evolution doesn’t care about your revenue projections.

And still, the antibody engineering revolution that powered Vir’s rise didn’t stop when sotrovimab hit Omicron. The core idea—finding potent antibodies in people who recovered, then engineering them into manufacturable medicines—remains one of the most powerful tools modern immunology has produced. 2020 proved we can respond fast. The harder question is how you keep the world investing in that capability during the quiet years between outbreaks.

Vir also ended up as a case study in the platform company model. It showed the promise: real infrastructure built ahead of time, multiple programs moving in parallel, and a rapid COVID response that would have been impossible for a single-asset biotech. It also showed the peril: theoretical diversification can still collapse into practical dependence on one product when the moment arrives.

What worked in Vir’s pandemic response: - Having platform infrastructure in place before crisis - Moving with exceptional speed on scientific discovery - Partnering effectively with big pharma for manufacturing and distribution - Targeting conserved epitopes for variant resilience (even though it ultimately wasn’t enough)

What didn’t work: - Commercial dependency on a single product - Underestimating the speed and extent of viral evolution - Not having next-generation candidates ready when the first-generation product stopped working

If there’s a single takeaway for the next pandemic—and there will be a next one—it’s that private companies can build astonishing scientific capabilities, but they struggle to keep those capabilities funded and “warm” without help. Sustained infectious-disease innovation likely needs public investment, reworked incentives, and commercial models that don’t assume every breakthrough behaves like a chronic-disease blockbuster.

It’s also worth pausing on the human element. In 2020, scientists at Vir, Humabs, and partner institutions worked at a pace that’s hard to sustain and harder to forget. Investigators enrolled high-risk patients. Manufacturing teams scaled production through supply-chain chaos. Regulators reviewed data on compressed timelines. Whatever happened later, sotrovimab was real medicine delivered to real people at a moment when the world desperately needed options.

Vir’s stated mission is simple and almost impossibly large: “A world without infectious disease.” It’s not fulfilled—missions like that never are on schedule. But the work continues: in hepatitis B and delta, in partnerships aimed at an HIV cure, and in the platform capabilities that might matter most the next time a new pathogen shows up.

And it’s a reminder of the mismatch at the heart of biotech: drug development demands patience that capital markets rarely reward. The path from early VIR-2218 trials to anything resembling a hepatitis B functional cure is measured in years. Investors who bought at $83 expecting a clean, linear story learned the hard way that biology doesn’t do linear. Investors who stay for Phase 3 data are choosing uncertainty—but also choosing the only way biotech value is actually created.

Vir Biotechnology’s story isn’t finished. Whether the next chapter is a breakthrough in hepatitis, a credible oncology expansion, a major partnership, or an eventual acquisition, Vir remains an ongoing experiment in what it takes to build sustainable infectious-disease biotech. The outcome matters not just to shareholders, but to the millions of patients living with diseases the industry deprioritized—and to the world that will eventually need pandemic readiness again.

XVI. Further Learning & Resources

Primary Sources: - Vir Biotechnology SEC filings (S-1, 10-K, 10-Q) — SEC.gov - COMET-ICE Phase 3 trial publication — New England Journal of Medicine - Vir investor relations materials — investors.vir.bio

Scientific & Technical: - VIR-2218 clinical trial publications — Journal of Hepatology - Humabs BioMed antibody discovery publications — Nature, Science, Cell - Herbert Virgin’s research publications — Google Scholar

Business & Strategy: - GSK–Vir partnership press releases — company websites - Biotech sector analysis — BioPharma Dive, Endpoints News - Pandemic preparedness policy reports — Center for Strategic & International Studies

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music