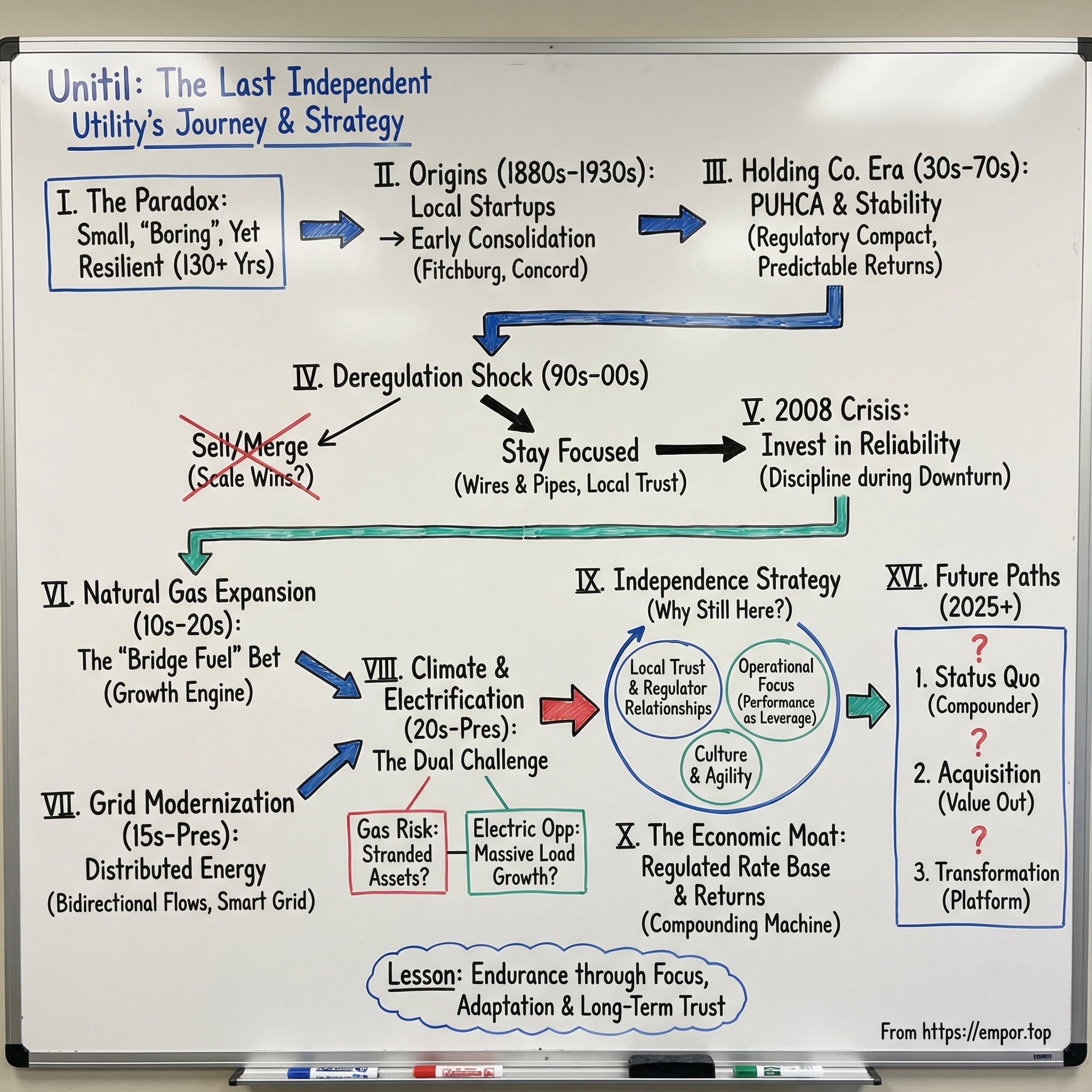

Unitil Corporation: The Story of New England's Last Independent Utility

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a bitter February morning in Concord, New Hampshire. It’s still dark, the temperature is sitting around fifteen below, and the wind is cutting through the bare maples along Main Street. Inside homes across town, thermostats click upward as families huddle in sweaters and socks. And somewhere in a modest brick building downtown, a small team at Unitil Corporation watches the system in real time—load climbing toward the daily peak as the region wakes up and turns on the heat.

Some version of that scene has been playing out for more than 130 years.

Unitil isn’t a household name. With a market cap around $600 million, it’s a speck next to utility giants like NextEra Energy or Duke. It serves about 108,000 electric customers and 86,000 natural gas customers across a patchwork of communities in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Maine. And in an industry built on consolidation—where regional utilities were steadily folded into multi-state behemoths—Unitil has stayed stubbornly, almost defiantly, independent.

That sets up the question at the heart of this story: how has a tiny independent utility survived for 130-plus years while so many others got acquired?

The answer turns out to be far more interesting than the “boring utility” stereotype suggests. This is a story about strategic discipline, deep regulatory relationships, and the counterintuitive ways being small can actually help in a business where everyone assumes scale wins.

Because yes, on the surface, Unitil’s business could not be more mundane. It delivers electrons and natural gas to homes and businesses in small New England towns. The service is invisible when it works—which is most of the time—and only noticed when it fails. Customers don’t choose Unitil; they inherit it by geography. There are no splashy product launches, no viral marketing, no headlines.

But underneath that calm exterior is a survival story. Unitil lived through the trust-busting era of the 1930s, the deregulation turbulence of the 1990s, the financial crisis of 2008, and now the existential pressure test of climate-driven electrification. Each wave crushed or absorbed peers. Each time, Unitil stayed standing.

This is worth studying for three reasons.

First, Unitil is a clean case study in how regulated businesses actually work—where the most important relationship isn’t with the person paying the bill, but with the commission that sets the rules and determines your returns.

Second, it shows how independence can be a strategy, not an accident. In a sector where “sell to the bigger guy” is the default endpoint, Unitil has repeatedly chosen not to.

Third, Unitil sits in the middle of what may be the defining infrastructure transition of our era: the electrification of everything.

New England states are pushing to phase out fossil fuel heating. Heat pumps are replacing oil burners. EVs are showing up in driveways that never had to think about charging load. Rooftops are turning into power plants. For a company that owns both electric wires and natural gas pipes, the questions get sharp fast. What does it mean to be a gas utility when policymakers want to ban gas? What does it mean to be an electric utility when power no longer flows in just one direction?

These aren’t academic debates. They’re being fought in rate cases, regulatory proceedings, and capital allocation meetings right now. For investors, that creates the classic utility paradox: enormous opportunity, because the transition demands decades of infrastructure investment, and real risk, because it can also mean stranded assets, political backlash over bills, and technology shifting faster than regulators can keep up.

So here’s the roadmap. We’re going to start where all utility stories start: with a spark—how electricity came to small New England towns and how the companies that eventually became Unitil were born. Then we’ll follow the industry through consolidation, regulation, and deregulation, and we’ll track the moments when Unitil had the chance to sell and chose not to. Finally, we’ll bring it to the present—grid modernization, distributed energy, electrification, and the uneasy future of natural gas.

Let’s go back to the beginning.

II. The Birth of Electric Utilities & Unitil's Origins (1880s–1930s)

On September 4, 1882, Thomas Edison threw the switch at his Pearl Street Station in lower Manhattan. Lights flickered on for customers like J.P. Morgan and the New York Times, and the world got a glimpse of the future. But for years afterward, electrification was still mostly a big-city novelty: expensive, finicky, and confined to a small radius around each generating station.

The real electrification of America didn’t happen in Manhattan. It happened town by town—especially in places like New England, where mill villages and manufacturing hubs were hungry for cheaper, more flexible power. This was less about lone inventors and more about local operators: practical businesspeople who could raise money from neighbors, get permission from city halls, build a plant, and start stringing wire down streets that still smelled of coal smoke and river water.

Unitil’s footprint traces back to exactly those kinds of communities. Concord, New Hampshire—capital city, regional center—was growing into modern life by the late 1800s. Along the Merrimack River, mills that had once run on waterpower were trying to keep up with changing technology and competition. Fitchburg, Massachusetts, a manufacturing town known for paper and machinery, faced the same pressure: modernize or fall behind. Electricity wasn’t a luxury. It was an industrial upgrade.

So the earliest predecessors of Unitil formed the way almost all early utilities did. Local groups secured exclusive franchises to serve a defined territory, scraped together capital, built generating stations and distribution lines, and then did the slow, unglamorous work of adding customers one at a time. There was no overnight scaling. It was infrastructure, built with patience.

And the economics pushed hard in one direction. A generating plant meant huge fixed costs—equipment, fuel, maintenance—whether you served ten customers or ten thousand. The poles and wires were the same story: expensive up front, cheaper to expand once the backbone was in place. That made each additional customer disproportionately valuable, and it created a natural incentive to grow outward and to combine systems wherever possible.

By the early 1900s, consolidation was already the default move. Small local operators merged with neighbors to spread costs and justify better equipment. In Massachusetts, Fitchburg Gas and Electric Light Company rolled up smaller operations around the Fitchburg area. In New Hampshire, Concord Electric Company pursued similar combinations around the capital region. These weren’t hostile raids; they were practical marriages—utilities trying to become more efficient, more reliable, and more financeable.

Around the same time, the rules of the game came into focus. The basic bargain—what later generations would call the regulatory compact—was simple. Utilities got exclusive rights to serve a territory, meaning a protected monopoly. In return, they accepted oversight: regulated rates, service standards, and the obligation to serve everyone in the franchise area, not just the most profitable customers.

That compact produced a very specific kind of company. Utilities weren’t designed for spectacular upside; they were designed for durability. They gave up the chance at windfall profits in exchange for something investors value just as much in the long run: predictability. Modest, steady returns supported by assets people could not live without.

It also shaped culture. Early utilities weren’t built to “move fast.” They were built to keep the lights on. The people running them tended to be engineers and operators, not celebrity entrepreneurs or Wall Street dealmakers. They planned in decades because their assets lasted decades—and because one bad decision could leave a whole town literally in the dark.

That foundation would end up being incredibly resilient. It helped utilities survive depressions, wars, and technological change. But it came with a tradeoff too: stability can look a lot like inertia. And that tension—between a system designed to be steady and a world that keeps changing—runs straight through Unitil’s story.

By the late 1920s, these small New England utilities looked stable, even prosperous. Then the storm clouds gathered—not an ice storm or a nor’easter, but a financial collapse and a political backlash that would reshape the entire industry.

III. The Holding Company Era & Regulatory Framework (1930s–1970s)

The stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression didn’t just crater demand and confidence. They also exposed something uglier inside the utility business itself.

In the roaring 1920s, financiers had built elaborate holding-company pyramids: companies owning companies owning companies, stacked so high and tangled so tightly that even sophisticated investors couldn’t see what they really owned. At the top sat a small group of promoters controlling enormous utility systems with remarkably little of their own capital at risk.

The poster child was Samuel Insull’s Middle West Utilities empire. When it collapsed in 1932, it didn’t just take down a corporate structure—it wiped out the savings of hundreds of thousands of ordinary investors. The investigations that followed painted a picture that infuriated the public: operating utilities siphoned through inflated “management fees,” intercompany loans priced to benefit the parent, and accounting maneuvers that made the whole machine look healthier than it was.

Washington responded with a sledgehammer. The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935—PUHCA—became one of the most consequential pieces of financial regulation in American history. It forced holding companies to simplify into single, integrated systems and put them under intense Securities and Exchange Commission oversight. The sprawling, multi-layered pyramids of the 1920s didn’t just fall out of favor; they were unwound by law and replaced with utility systems that were cleaner, more geographically coherent, and far easier to regulate.

For small New England utilities, PUHCA was both a set of handcuffs and a shield. It sharply limited the ability of outside financial interests to scoop up local utilities and stitch them into far-flung empires. And it reinforced the power of state commissions—the bodies that set rates and service standards—keeping control close to the communities being served. That basic framework would define the industry for decades.

Unitil took shape in this environment, using a holding-company structure that fit the new rules while gathering a set of operating utilities under one corporate umbrella across New Hampshire and Massachusetts. That structure wasn’t about financial wizardry. It was practical: shared services where it made sense, access to capital markets as a group, coordinated planning—while keeping the operating companies’ legal identities and regulatory relationships intact.

Then came the long, quiet stretch.

From the 1940s through the 1970s, the utility business was—by its nature and reputation—steady. World War II created real constraints: materials were rationed, labor was tight, and demand jumped in places supporting defense production. But the war also clarified utilities’ role as essential infrastructure. Coming out the other side, the postwar boom delivered exactly what regulated utilities love most: predictable growth. Veterans bought homes, suburbs expanded, and those homes filled up with appliances that quietly drove load higher year after year.

This was the era that turned utilities into classic “widow and orphan” stocks—safe, dull, dividend-paying investments that you could tuck away and not think about. Utilities built infrastructure, earned regulated returns on it, and paid those returns out in steadily rising dividends. The whole system was designed for stability, and for a long time it worked.

Inside the companies, that stability hardened into culture. Utilities became hierarchical and conservative. Innovation wasn’t the point; reliability was. Careers were built on operational discipline and the ability to navigate rate cases without surprises. The best utility executives weren’t celebrated for bold vision. They were valued for avoiding mistakes that could end up on the front page—or in front of regulators.

For a small company like Unitil, this was close to ideal. Scale didn’t automatically buy you better economics; regulation largely equalized returns across big and small players. What mattered more was local competence: keeping service reliable, investing prudently, and building credibility with the regulators who ultimately determined what the company could charge and what it could earn. If you did those things well, you didn’t need to be huge to endure.

But the outside world was starting to shift, and the cracks showed up first in energy. The oil shocks of the 1970s shattered the assumption that fuel would stay cheap and plentiful. Environmental opposition made it harder to build big new power plants without a fight. And while Three Mile Island arrived in 1979, the anxiety had been building even earlier: utilities were committing massive capital to long-lived generation assets at the same moment the public was becoming less willing to accept the risks and costs.

Underneath all of it sat a bigger question that policymakers began to ask more loudly: had the natural-monopoly model produced a dependable system—or a complacent one?

That question didn’t fully explode until the 1990s. But once it did, it triggered the most disruptive era utilities had faced since the 1930s. And for Unitil, the comfortable assumptions of the postwar decades were about to be tested.

IV. Deregulation Shockwaves & The Great Utility Consolidation (1990s–2000s)

The Energy Policy Act of 1992 hit utility boardrooms like a starter pistol. For the first time, federal law pushed open the transmission grid to competing power suppliers. It didn’t abolish the old model overnight, but it cracked the foundation of the vertically integrated utility—the one company that owned the power plants, the high-voltage lines, and the neighborhood wires.

The idea was clean and very 1990s: let competition into generation, let markets set prices, and consumers would win. In practice, it meant states began “restructuring” their electric systems, especially in places like the Northeast and California. Regulators tried to unbundle the industry—separating power generation from transmission and distribution—and they encouraged or required utilities to sell off their power plants to independent producers that would compete in newly created wholesale markets.

For a lot of management teams, that wasn’t a strategy shift. It was an identity crisis.

Generation was the glamorous part of the utility business. It was where the big engineering lived, where the huge capital projects lived, where executives could point to something physical and impressive on the horizon. The wires business—distribution and transmission—was the opposite. It was essential, but invisible: poles, transformers, substations, and crews in bucket trucks.

Now the message from policymakers was basically: the future is the unglamorous part.

Utilities responded the way big, regulated companies often do when the ground moves under them: they got bigger. The late 1990s turned into a merger spree as companies tried to bulk up for what everyone assumed would be a tougher, more competitive world. In the Northeast, larger players absorbed smaller neighbors. National Grid, a British utility, began buying its way into the U.S. market. The map started to redraw itself into fewer and fewer, larger and larger names.

Then the wheels came off.

Enron, the energy trader that had sold itself as the cutting-edge future of deregulation, collapsed in 2001 under accounting fraud and allegations of market manipulation. At nearly the same time, the California electricity crisis delivered the nightmare scenario: extreme price spikes, broken market incentives, and rolling blackouts. The industry got a blunt lesson that “competitive power markets” could be volatile—and that when they failed, the political backlash didn’t land on the traders. It landed on the whole system.

The merchant power boom that had inflated asset values in the late 1990s popped hard. Companies that had paid top dollar for divested power plants watched those assets fall in value. Some of the most aggressive buyers and traders ended up in restructuring mode, or worse. The promise that competition would automatically translate into lower bills didn’t hold up everywhere, either. In many places, customers felt like they’d been sold a miracle cure and handed a higher invoice.

It was in this messy, uncertain moment that Unitil faced one of the most consequential questions in its modern history: do you sell, merge, or try to stay independent?

On paper, selling had a lot going for it. The conventional wisdom said scale would matter more now. Bigger utilities could spread compliance costs and back-office overhead across more customers. They could justify larger technology budgets. They could borrow more cheaply. And Unitil, by comparison, was small—serving well under the customer counts of the regional giants forming around it.

But Unitil’s board and management made a different bet. Instead of chasing size, they chose focus.

They leaned into what they were already built to do: deliver electricity and natural gas safely and reliably in a defined set of communities in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Maine. They moved away from generation exposure and toward a pure “wires and pipes” model—own the distribution networks, invest in them, operate them well, and earn regulated returns by doing exactly what regulators want most: keep service reliable and bills justifiable.

That choice rested on a few clear-eyed observations.

First, restructuring didn’t eliminate the distribution monopoly. Customers might be allowed to pick an electricity supplier on paper, but the power still had to travel through Unitil’s system to reach the kitchen light switch. Unitil still held the franchise. It still owned the last-mile infrastructure. And the regulatory compact—the basic bargain of oversight in exchange for stable returns—still applied to that part of the business.

Second, even in a deregulated era, state regulators didn’t stop caring about the fundamentals. If anything, they cared more. When markets get complicated, reliability and customer experience become political issues fast. A utility that ran a tight ship—good service quality, strong storm response, credible planning—could build the kind of trust that pays off over decades of rate cases.

Third, and maybe most importantly, Unitil recognized that the biggest “economies of scale” story was being oversold—at least for distribution. Keeping the lights on is local. A storm crew rolling to a downed line in Concord gets no faster because the parent company owns assets three states away. The work depends on local infrastructure knowledge, local relationships, and operational discipline more than corporate sprawl.

So Unitil narrowed its scope and doubled down on execution. Without the capital and risk profile of power plants, the company could put its investment and attention into the grid it actually controlled: improving reliability, upgrading infrastructure, and strengthening customer service.

When the deregulation dust finally settled, Unitil hadn’t just survived. It had gotten clearer about what it was.

While some larger peers were busy digesting acquisitions, managing impairments, and explaining why the “new world” hadn’t played out as advertised, Unitil kept doing the unglamorous work—quietly serving its communities, case by case, storm by storm. And the decision to stay independent, which could have looked like stubbornness in the moment, began to look a lot more like strategy.

V. The 2008 Financial Crisis & Capital Allocation Discipline (2008–2012)

When Lehman Brothers collapsed in September 2008, utility executives didn’t need a macroeconomics lecture to understand what was coming. Credit was seizing up. Stock prices were falling fast. Big commercial and industrial customers were cutting production, or wondering if they’d survive at all. After a decade of deregulation drama, the industry was staring down another stress test—this time from the financial system itself.

And yet, utilities turned out to be one of the economy’s shock absorbers.

In a recession, people might skip vacations, delay car purchases, and eat out less. But they still turn on the lights. They still cook dinner. In New England, they still need heat. Demand can soften around the edges and bad-debt expense can tick up, but the core reality holds: electricity and gas are not optional. That essential nature gave the whole sector a level of resilience that most industries could only envy.

For Unitil, the crisis didn’t inspire a sudden reinvention. It reinforced the value of the way the company already operated.

Unitil had kept its financial profile conservative: investment-grade credit, moderate leverage, and none of the “clever” financing structures that looked great in boom times and became handcuffs when liquidity disappeared. So when the capital markets began to thaw, Unitil could raise money on reasonable terms. Others—especially companies that had stretched for growth or piled on risk—had a much harder time getting financed at all.

But the crisis also created an opening.

As many larger utilities went into defensive mode—cutting back, delaying projects, hoarding cash—Unitil made a deliberate choice to keep investing. Its distribution networks were mature. Much of the system had been built in the mid-twentieth century, and the stuff that quietly does its job for decades eventually runs out of runway: poles weaken, transformers age, and older equipment becomes harder to maintain. Unitil could either defer replacements and hope nothing went wrong, or it could treat the downturn as a chance to get ahead of the curve.

They chose the second path: accelerate infrastructure upgrades while construction markets were softer and contractors had capacity.

That wasn’t a risk-free decision. Spending more during an economic crisis can spook investors who want caution, not ambition. And in a regulated business, capex only becomes valuable if regulators agree it was prudent and allow it into rate base, so the company can recover the investment over time through customer rates. Unitil had to be disciplined in what it funded, clear in why it mattered, and credible in how it was executed.

The logic was simple, and it’s the kind of flywheel only regulated utilities really get to run: invest to improve reliability, reliability drives customer satisfaction, customer satisfaction shapes the political climate, and the political climate influences regulatory outcomes. In this world, customer satisfaction isn’t a soft metric. It’s a strategic asset—one that shows up later when you’re asking permission to spend more and earn a return on it.

Nowhere is that more obvious than storm response.

New England weather isn’t a backdrop; it’s an operating condition. Ice builds up on lines until they sag or snap. Nor’easters push trees into rights-of-way and turn roadways into obstacle courses for crews. And every so often, a hurricane tracks north and reminds everyone that “inland” doesn’t mean “safe.” When those events hit, customers don’t grade utilities on a curve. They remember how long they were without power, how well they were kept informed, and whether restoration felt organized or chaotic.

So Unitil put money and attention into the kinds of upgrades that never look exciting on a slide, but matter at 2 a.m. during an outage: stronger poles, better vegetation management, redundancy where it made sense, and systems that improved coordination with towns, emergency services, and state officials. Communication improved too—because even when restoration takes time, silence makes everything worse.

None of this generated splashy headlines. That was the point. The goal was fewer outages, shorter outages, and a reputation for competence.

This period also clarified something that Unitil’s leadership had been betting on since the deregulation era: in utility regulation, size isn’t automatically an advantage. State commissions don’t award higher returns because a company serves more customers. They care about whether you’re delivering reliable service, whether your spending is prudent, and whether rates are reasonable.

A small utility that executes well can earn the same returns as a giant—and sometimes navigate more effectively because it’s closer to its communities. Unitil could build relationships and credibility in each jurisdiction it served. Management understood the priorities of regulators in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, and it could adapt to local expectations instead of forcing a one-size-fits-all approach across a sprawling footprint. That kind of regulatory fluency doesn’t show up on a balance sheet, but it compounds over time.

And it would matter even more in the next chapter, when Unitil leaned into a growth strategy that would define the 2010s: expanding its natural gas distribution business.

VI. Natural Gas Expansion: The Bet on Fossil Fuel Transition (2010–2020)

In the early 2010s, the U.S. energy system flipped faster than almost anyone expected. Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling unlocked huge new supplies of natural gas. Prices fell. Utilities and policymakers started talking about gas as a “bridge fuel”: cleaner than coal, available at scale, and reliable in a way wind and solar still weren’t.

In New England, that revolution arrived with an asterisk. The region didn’t sit on shale fields, and it relied on pipelines from elsewhere. Those pipelines were often tight—especially in winter—so cold snaps could send gas prices surging just when demand for heating and power generation hit the same peak. The rest of the country was swimming in cheap gas. New England, paradoxically, could feel like it was rationing it.

Unitil looked at that landscape and saw something rare in a regulated utility: a real growth lane.

Northern New England still had millions of homes heated by oil—an old regional habit shaped by history, geography, and the simple fact that many neighborhoods never had gas mains to begin with. Heating oil was expensive, volatile, and increasingly out of step with where public opinion was headed. Natural gas offered something homeowners could feel immediately: lower bills, cleaner combustion, and the convenience of a pipe instead of a delivery truck.

So Unitil pushed hard into gas distribution expansion. It extended mains into neighborhoods that had never had service, and it marketed conversions to homeowners who were tired of paying a premium to heat their homes. This was heavy, unglamorous infrastructure work: trenching streets, laying new distribution pipe, installing meters and regulators, and upgrading the facilities needed to feed and control the system. But the payoff was exactly what regulated utilities are built around. Each new customer wasn’t a one-time sale. It was decades of steady, regulated revenue.

The math worked because the business model was designed for it. Unitil could recover prudent investment through rates over time and earn its allowed return on that growing rate base. Customers, meanwhile, often saw savings quickly enough to make conversion feel like an easy decision. And regulators in New Hampshire and Massachusetts generally recognized the consumer benefits of shifting homes from oil to gas, approving mechanisms that supported investment and recovery.

Over the decade from 2010 to 2020, Unitil’s gas business grew meaningfully faster than its electric side. The company added thousands of customers, pushed mains into new areas, and put hundreds of millions of dollars into gas infrastructure. As the rate base grew, earnings per share rose steadily alongside it.

New England’s pipeline constraints even created a strange kind of tailwind. When gas prices spiked at the city gate during cold snaps, Unitil passed those commodity costs through to customers—it didn’t make money on price volatility. But the spikes reinforced the value of having access to gas at all. Customers who had switched from oil watched neighbors deal with deliveries and higher, more unpredictable heating bills, and many felt they’d made the right call.

As the buildout expanded, Unitil’s playbook matured. The company showed up to regulators with detailed engineering plans and cost-benefit work meant to prove the spending was prudent. It ran customer outreach programs to drive conversions. It proposed rate mechanisms that spread the costs of main extensions more broadly, making expansions pencil out in places that otherwise would have been too expensive to reach. And it worked with towns, housing authorities, and local economic development groups that saw gas availability as a practical tool: better housing quality, lower heating costs, and one more selling point for attracting business.

By 2020, natural gas had become a central driver of Unitil’s growth—both in capital investment and in earnings. For a while, it looked like the “bridge fuel” story was playing out exactly as promised: gas replacing oil for heat, displacing coal in power generation, and serving as the dependable backbone while renewables scaled.

But even as Unitil was laying pipe, the political ground started shifting. The same climate movement that once saw gas as an improvement began to ask a sharper question: cleaner than coal is not the same as compatible with a zero-carbon future. Legislatures started debating building electrification. Activists targeted pipeline projects and called for an end to gas expansion altogether.

The bridge, it turned out, might be shorter than anyone wanted to believe.

VII. Grid Modernization & The Distributed Energy Challenge (2015–Present)

On a quiet residential street in southern New Hampshire, a homeowner spreads a solar proposal across her kitchen table. A couple dozen panels on the roof. A battery in the garage. The pitch is simple: produce most of your own power, buy less from the grid, and watch the bill shrink.

Ten years earlier, this would’ve sounded like a boutique project—something for early adopters with money to spare. By the mid-2010s, it started to look like a normal household upgrade, helped along by federal tax credits, state incentives, and the simple fact that New England electricity isn’t cheap.

For Unitil—and every electric utility—this is the moment the twentieth-century playbook stops working as written.

The old system was beautifully straightforward. Big power plants generated electricity. High-voltage transmission moved it across the region. Local distribution wires delivered it to customers. Power flowed one direction, and planning was built around a pretty stable assumption: customers consumed, utilities supplied.

Distributed energy resources blow that up. Rooftop solar turns customers into generators. Batteries let them shift when they buy—or don’t buy—from the grid. Electric vehicles add large, spiky new loads, and in some cases can even send power back through bidirectional charging. Suddenly the grid has to handle two-way flows on infrastructure that was designed for one-way delivery. And the demand a utility uses to plan investments becomes harder to predict, shaped by sunshine, charging habits, and how quickly technology adoption spreads through a community.

New England has leaned into this transition early and aggressively. Massachusetts requires net metering, which credits solar customers for the excess power they export at retail rates. Maine set ambitious renewable targets of its own. And because prices are high, solar can pencil out here sooner than it might in other parts of the country—even before subsidies enter the picture.

That puts utilities in a weird spot. For decades, load forecasting was a disciplined, boring exercise. Now the range of outcomes has widened dramatically. Demand could stay flat as solar offsets consumption. Or it could surge as EVs proliferate and buildings electrify. And it can do both at once: lower midday demand because of solar, higher evening peaks because everyone plugs in and turns on electric heating.

Unitil’s response has been to modernize the grid so it can see—and manage—what’s happening on it.

A big piece of that is advanced metering infrastructure: smart meters that replace monthly snapshots with granular data. That data helps Unitil understand how customers use energy, when distributed generation is exporting power, and where the system is starting to strain.

Alongside that, Unitil has invested in grid automation—sensors and switches that can detect problems and reroute power automatically. It’s the kind of work customers rarely notice when it’s done well, except in the most important way: fewer outages and faster restoration when something goes wrong.

Then there’s the concept that barely existed in the mainstream utility conversation a decade ago: hosting capacity. In plain English, it’s how much rooftop solar and other distributed generation a particular circuit can handle before voltage and power quality problems show up. Unitil has put real effort into mapping that circuit by circuit, because in a distributed world you can’t just say “more solar is good” and hope the physics cooperate.

For a small utility, the hard part is that none of this is optional—and none of it is cheap. Large utilities can spread technology spending and expertise across millions of customers. Unitil has to build many of the same capabilities with a fraction of the scale. One way it’s closed that gap is through collaboration: showing up in regional forums and research initiatives where smaller utilities can share what they’re learning and avoid reinventing the wheel.

But the challenge isn’t just technical. It cuts straight into the business model.

If more customers produce some of their own electricity, what exactly is the utility selling? And if solar customers pay very little toward the grid while still relying on it for nights, storms, and winter, who covers the cost of the infrastructure that makes that backup possible? Those questions have ignited regulatory fights across the country. Solar advocates argue that continued incentives accelerate decarbonization. Utilities warn about a cost shift—sometimes framed as a “death spiral”—where more self-generation pushes more grid costs onto customers who can’t afford solar in the first place.

Unitil has tried to walk a careful line. It has acknowledged the benefits of distributed energy, while pushing for rate designs that allocate the fixed costs of running a safe, reliable grid in a way that doesn’t unfairly burden non-solar customers.

It has also explored performance-based ratemaking pilots—an attempt to align utility incentives with policy outcomes. Instead of only earning returns by putting more capital into the ground, the utility could be rewarded for results: better reliability, smoother integration of distributed resources, progress toward emissions goals.

And this is where Unitil’s size cuts both ways. It doesn’t have the giant in-house research teams of the regional behemoths. But it can be more nimble, testing approaches without the layers of bureaucracy that come with sprawling organizations. Its relationships with regulators are close and local, which can make it easier to have real dialogue about new structures rather than waging war through filings and press releases.

Still, the central question hangs over everything: what is a utility in a world where customers can generate, store, and manage their own energy?

Is it a commodity provider that gets slowly disintermediated? A platform operator coordinating complex flows on a shared network? Or an infrastructure company whose job is to keep the grid dependable—no matter who produces the electrons?

However that question gets answered, Unitil will have to live inside it for decades.

VIII. Climate, Electrification, & the Death Spiral Question (2020–Present)

When COVID hit in 2020, it didn’t just change where people worked. It changed how the grid was used. Office buildings went quiet while homes became offices, classrooms, and daylong heating zones. Utilities had to adjust to a load shape that suddenly leaned more residential. At the same time, supply chains snarled and basic infrastructure work got harder to schedule, harder to staff, and more expensive to complete.

Then the policy environment shifted even faster.

The Biden administration came in during 2021 with the most aggressive federal climate posture the U.S. had ever taken. And in 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act put enormous incentive dollars behind clean energy, electric vehicles, and building electrification. In the Northeast, states didn’t wait around. Massachusetts and Maine pushed their own emissions mandates forward, tightening timelines and raising ambition.

For Unitil, this collided head-on with the bet it had just spent a decade making.

The company had invested hundreds of millions of dollars expanding natural gas distribution—assets meant to last for generations. Pipes in the ground are not software. They’re built on 40- to 50-year assumptions. But now, policymakers were openly imagining a future where fossil-fuel heating gets phased out and replaced by electric heat pumps powered by renewables.

That’s how “stranded assets” stopped being an academic phrase and started sounding like a balance-sheet threat.

If parts of the gas system become underutilized long before the end of their intended life, someone still has to pay for what was built. Is it shareholders, who invested under the premise of regulated cost recovery? Is it customers, who could face higher rates as fewer people remain on the system? Is it taxpayers, via subsidies and transition programs? The answer won’t come from a single announcement. It will come from years of rate cases, legislative debates, and regulatory precedent—exactly the kind of slow-moving process that makes uncertainty feel even sharper.

The pressure is most visible in Massachusetts, where building electrification policies have begun restricting or prohibiting new gas connections in certain contexts. Maine has set ambitious heat pump installation targets. Even New Hampshire, historically less aggressive on climate policy, isn’t insulated from the broader regional direction or the gravitational pull of federal incentives.

And here’s the twist: the same policies that threaten Unitil’s gas expansion are a growth engine for its electric business.

If buildings move from oil or gas to heat pumps, electricity demand climbs—especially in winter, when New England already runs tight. If EVs replace internal combustion cars, the grid takes on a whole new category of load. The big-picture implication is staggering: widespread electrification could require the electric system to expand dramatically, potentially on the order of multiples of today’s capacity, over time. That’s not a normal capex cycle. That’s an infrastructure buildout on the scale of a generation.

For Unitil, that reframes the company’s future. Electric demand growth has been flat to modest for years—efficient appliances, better insulation, and solar all put pressure on sales. Electrification flips the script. For the first time in decades, the “wires” business could be staring at sustained growth that feels more like the postwar boom than the modern era. And in regulated utility math, growth in required infrastructure means growth in rate base, which is the engine that ultimately drives earnings and dividends.

Unitil has been preparing for that possibility in practical, unglamorous ways. It’s studying what widespread EV charging would do to local feeders and substations—because the grid doesn’t experience EV adoption as a national trend; it experiences it as a handful of neighborhoods that suddenly need far more capacity at 6 p.m. It’s modeling heat pump adoption and what it means for winter peak demand, including the risk that the system’s hardest hour shifts and intensifies as more heating becomes electric. And it’s working with policymakers and regulators on what “electrify everything” means in the real world: timelines that aren’t wishful thinking, funding mechanisms that don’t collapse under backlash, and rate designs that encourage adoption without blowing up affordability.

Because that’s the tightrope. Actually, it’s three tightropes at once.

Climate advocates want speed and see hesitation as obstruction. Affordability advocates see rising bills and ask, reasonably, who this transition is really for. Investors want clarity: if you’re going to push the system toward electrification, what happens to the gas assets that were built under yesterday’s policy assumptions, and will the company be allowed to recover what it prudently invested?

Recent rate cases have brought those tensions to the surface. Unitil has gone in asking for higher rates to fund reliability work, infrastructure upgrades, and preparation for new load. Consumer advocates have pushed back, arguing customers can’t absorb increases—especially in an inflationary environment. Regulators sit in the middle, weighing prudence, timing, and public tolerance. And the details matter: allowed returns, recovery mechanisms, which projects get approved, and how quickly costs can be put into rates.

So the story here isn’t that Unitil is doomed, or that it’s guaranteed to prosper. It’s that the old twentieth-century equilibrium—slow demand growth, predictable planning, and long-settled assumptions about gas—has started to give way. In its place is a more dynamic system with bigger stakes: more technology change, more political attention, and more upside if the company can navigate the transition without losing the trust of regulators and customers along the way.

IX. The Independence Strategy: Why Unitil Still Exists

Walk into the headquarters of most utility holding companies and you’ll see it immediately: scale made physical. Big campuses. Big staffs. Big layers of management. Unitil’s home base tells a different story. It’s plain, compact, and functional—less corporate monument, more place where people come to run a system.

That contrast leads to the obvious question. In a sector that spent decades consolidating into multi-state giants, why is Unitil still here?

Start with the gatekeepers: regulators. In a regulated monopoly, you can’t just buy a utility the way you buy a software company. State public utility commissions have real authority, and they don’t approve deals unless they can be convinced customers will clearly benefit. Any buyer would have to run the gauntlet in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Maine—answering hard questions about service quality, local jobs, storm response, and whether a new parent company would stay focused on these communities once the paperwork was signed. That scrutiny adds time, uncertainty, and political risk. Even if a deal is theoretically “good,” it’s not always worth the hassle.

Then there’s the simple math. Unitil often trades at a premium to book value, reflecting that investors see it as a well-run set of regulated assets with strong local relationships. An acquirer would have to pay up, then persuade regulators to approve the transaction, then do the integration work—while trying to find synergies that are far from guaranteed in a business where many costs are already local and operational. For a strategic buyer that already has a Northeast footprint, the overlap can make the payoff even murkier.

Unitil has also behaved like a company that wants to remain independent. Management and the board have put governance in place that makes a hostile deal harder, including staggered board terms and shareholder rights provisions. They’ve cultivated a shareholder base that tends to like what Unitil offers: focus, steadiness, and dividends. And the better they operate, the less appealing they become as a target—because strong performance supports that premium valuation.

Independence isn’t just defensive, though. It’s part of the strategy.

Utilities live and die by regulatory relationships, and those are intensely local. Unitil’s leadership understands the personalities, priorities, and politics in each of its states. It can tailor how it shows up—how it communicates, how it plans, how it frames spending—based on what those regulators and communities actually care about. A distant parent company might try to standardize processes across a larger empire. That can create efficiency on paper, but it can also create friction where it matters most.

Operationally, Unitil leans on performance as its calling card. The company points to strong reliability, customer service, and restoration response relative to regional peers—exactly the metrics that shape public sentiment and, eventually, regulatory outcomes. In a monopoly business, reputation is not branding. It’s leverage.

And then there’s culture. An independent utility can move faster inside its own walls, run pilots without fighting internal bureaucracy, and respond to local events without waiting for corporate approval from another state. The work stays personal: crews restore power for people they might run into at the grocery store. That kind of accountability is hard to manufacture at giant scale.

Of course, the counterargument is real. Shareholders could benefit from an acquisition premium—an immediate payout instead of the slow accumulation of dividends and gradual appreciation. Small utilities also tend to have thinner trading volume and less analyst coverage, which can leave them underappreciated at times. A buyer offering a meaningful premium could make a compelling case.

Unitil’s answer has been consistent: independence can be the premium. By keeping operations tight, investing prudently, and navigating regulation skillfully, the company argues it can deliver returns that stand up well against bigger peers. Shareholders get a growing dividend and long-term compounding, without betting on a one-time exit.

That ties into what you might call the “forever company” mindset. If you assume you’re not selling, you plan differently. Management can make long-horizon investments without worrying about how they’ll look in a near-term deal process. Employees can build careers without the constant threat of reorgs. Regulators and communities get continuity, which matters a lot in a business built on trust.

Whether that independence is sustainable forever is still an open question. Grid modernization and electrification require capital, technology, and talent—demands that can strain smaller organizations. Policy could evolve in ways that reward larger, more diversified utilities. The next decade will test whether agility and local credibility can keep beating raw scale.

But up to now, Unitil has pulled off something rare in modern utilities: it has stayed small, stayed local, and stayed independent—by making that choice work.

X. Business Model Deep Dive & Economic Moats

To understand how Unitil makes money, you have to understand the deal at the center of every regulated utility. It’s simple in concept and nuanced in practice: the company spends money to build and maintain essential infrastructure, and regulators let it earn a fair return on that investment—so long as the spending was necessary and prudent.

Everything starts with rate base. Think of it as the utility’s earning engine: the poles and wires, transformers, substations, gas mains, meters, and other physical assets that make up the distribution network. Regulators value that infrastructure largely on original cost, minus depreciation. Then they decide what return Unitil is allowed to earn on the capital supporting that rate base.

Here’s what that means in plain terms. If Unitil has a rate base of $600 million and an allowed return on equity of 9.5%, it’s permitted to earn roughly $57 million on the equity slice of that investment, assuming a typical utility capital structure. Customer rates are then set to cover the full stack: day-to-day operating costs, depreciation, taxes, and the allowed return on invested capital.

Once you see that, you see the core driver of almost every regulated utility’s long-term value: rate base growth. Every mile of new gas main, every substation upgrade, every smart meter installation can expand rate base. Expand rate base, and—if regulators agree the spending was justified—you expand the earnings stream the company is allowed to collect over time.

That “if” is where the real work lives.

Utilities don’t get to declare their own returns. They ask for them through rate cases: formal regulatory proceedings where Unitil lays out its costs, investments, and financing mix and argues for new rates that support a target return. Then the cross-examination starts. Consumer advocates, large customers, and commission staff challenge assumptions, question spending, and push for lower returns or slower recovery. The commission weighs it all and issues an order that sets the terms for the next period.

This is why regulatory relationships function like a moat. Rate cases are technical, but they’re also trust-based. A utility that has built credibility—by planning well, operating reliably, communicating clearly, and not playing games—usually has an easier time defending investments than one seen as wasteful or combative. Unitil’s long history in small, tight-knit service territories, and its emphasis on operational execution, is an advantage here.

The mix of customers matters too. Residential customers tend to be more expensive to serve per unit of energy delivered: more meters, more calls, more billing complexity. But they’re also sticky and predictable, with usage patterns tied to weather and seasons. Commercial and industrial customers are efficient to serve because load is concentrated, but they can be more sensitive to rates and economic cycles.

Weather adds another layer. Warm winters can reduce gas throughput and pressure revenues even while the system’s costs don’t fall in tandem. Major storms can drive restoration costs higher and create reputational and regulatory risk if outages drag on. Utilities use various adjustment mechanisms to dampen some of this volatility, but no one escapes New England weather entirely.

Then there’s operating leverage—the quiet amplifier in the model. The grid and the gas system are mostly fixed-cost businesses. Once the infrastructure exists, additional usage and additional customers can be very profitable. But the reverse is also true: if load erodes, the costs don’t disappear with it. That’s why electrification is so attractive to an electric utility (new load can support lots of investment and earnings growth), and why distributed generation and aggressive conservation can create real tension (lost load can squeeze the economics quickly).

For investors, this is why utilities are often owned less like growth stocks and more like compounding income machines. What matters is the dividend: how reliable it is and whether it grows over time. Unitil has paid an unbroken dividend since becoming a holding company, steadily increasing it as earnings expanded.

Underneath all of that is capital structure. Because utility cash flows are relatively stable, regulators generally allow a meaningful amount of debt in the financing mix. Debt is cheaper than equity, which can lower customer costs and improve overall economics. But too much leverage invites credit downgrades, higher borrowing costs, and less flexibility just when the company needs to fund major infrastructure programs. Unitil has aimed to stay investment-grade by keeping leverage at moderate levels, preserving room to finance what comes next.

If you want the scoreboard for how Unitil is doing, two numbers matter more than almost anything else: how fast rate base is growing, and what allowed returns regulators are granting. Strong rate base growth with constructive allowed returns is the recipe for durable earnings and dividend growth. Flat investment or weakening regulatory outcomes, on the other hand, is what turns a utility from a steady compounder into a stagnating bond proxy.

And in Unitil’s case, those metrics don’t just describe financial performance. They tell you whether the company’s biggest strategic balancing act—modernizing the electric system while navigating an uncertain future for gas—is working.

XI. Competitive Dynamics & Strategic Positioning

In most industries, “competition” means stealing customers, cutting prices, and shipping a better product. Utilities don’t work like that. In a regulated monopoly, you don’t win by taking market share. You win by earning trust—in rate cases, in reliability metrics, and in the day-to-day experience customers and communities have when something goes wrong.

That’s the arena Unitil competes in, and it’s a crowded neighborhood.

Around Unitil are much larger players with deeper benches and bigger balance sheets. Eversource Energy—built from the mergers that created Northeast Utilities and NSTAR—serves millions of customers across Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire. National Grid, the British-owned giant, runs major electric and gas systems in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Liberty Utilities, part of Canadian infrastructure company Algonquin Power & Utilities, has picked up several New England properties and has been an active buyer when assets come on the market.

These companies aren’t fighting Unitil for the same households. Customers don’t choose their distribution utility. But the competitive dynamics still show up in three important places.

First: regulation is a comparative sport. A commission doesn’t evaluate Unitil in a vacuum. Outcomes in a peer’s rate case can shape expectations in the next case—what spending looks “reasonable,” what level of return feels “fair,” and how aggressively commissions push back on costs. Service quality metrics get compared the same way. If a neighboring utility is restoring outages faster or running fewer interruptions, that becomes an uncomfortable benchmark.

Second: growth is geographic. New housing developments, commercial expansions, and industrial projects don’t go out to bid between utilities. They land inside someone’s territory. If your footprint happens to sit in the path of growth, you get the load. If it doesn’t, you don’t. That reality makes service territory—something that sounds static—one of the biggest long-term strategic variables.

Third: the “competition” can be for permission. Utilities increasingly need approval for modernization programs, new rate designs, and capital plans tied to electrification. A larger peer that successfully gets a new mechanism approved can effectively set a precedent—and raise the bar for everyone else.

Unitil’s positioning has long leaned into what being small can do well. Its service territories are concentrated enough to build real local knowledge: the circuits that routinely get hammered by storms, the neighborhoods where load is growing fastest, the towns that care most about undergrounding, the industrial customers whose operations can’t tolerate flicker. That focus can translate into tighter planning and faster execution. And it can make decision-making simpler—fewer layers, fewer competing internal priorities.

Most importantly, it gives Unitil an argument regulators actually value: performance. Reliability metrics like outage frequency and restoration time, plus customer satisfaction, become more than operational scorekeeping. They’re evidence. When Unitil asks to invest, it’s effectively saying: we’ve shown we can spend prudently and operate well; let us keep doing it.

There’s also a threat in the background that many people forget still exists: municipalization.

Across the U.S., some communities choose to run their own electric utilities instead of relying on investor-owned companies. Municipal utilities serve roughly 14% of U.S. electricity customers, and they can sometimes offer lower rates because they’re nonprofit and can access tax-exempt financing. When bills spike or trust erodes, the idea of taking service public can go from fringe to headline surprisingly fast.

Unitil has largely avoided becoming a municipalization target by keeping rates reasonable and staying visibly connected to its communities—management that shows up locally, crews who live in the towns they serve, and a relationship that feels less like a distant corporate brand and more like a regional institution. But it’s still a reminder of the real underlying reality of the regulatory compact: a utility’s right to operate depends on public tolerance, not just legal paperwork.

Then there’s a very different kind of pressure: technology.

Tesla’s Powerwall and solar products help customers rely less on the grid. Smart thermostats like Google’s Nest help customers shape demand and cut usage. These aren’t “competitors” in the traditional sense, but they can reduce load growth, shift peaks, and change what customers expect from their energy experience. And the companies building those products have brand power and customer relationships that utilities generally don’t.

Unitil’s posture has been to integrate rather than fight. Smart meters give the company better visibility into how the system is actually being used. Grid automation improves reliability and speeds restoration. Instead of treating technology as an enemy trying to disintermediate the utility, Unitil positions itself as the platform that makes all of it work safely—because even the most advanced rooftop-and-battery setup still depends on the grid for backup, stability, and interconnection.

That’s what differentiation looks like in a commodity service. Not flashy features, but competence customers can feel: fewer outages, faster restoration, clearer communication when things break, and a community presence that’s credible when the next rate case arrives.

The investor question, though, is the hard one. As larger peers pour money into modernization and customer experience, can a small utility keep up? Can Unitil fund the technology transition without scale, and can local relationships and operational focus continue to offset the advantages of being a multi-billion-dollar giant?

The next decade of electrification is where those answers get written.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Michael Porter’s framework is a helpful way to sanity-check Unitil’s position. Not because Unitil “competes” the way a normal company does, but because it shows where pressure can realistically come from in a regulated monopoly—and where it can’t.

Threat of New Entrants: Essentially zero. The barriers aren’t just high; they’re structural. To serve customers, a would-be competitor would need state approval to operate in territory that’s already assigned to an incumbent utility. And even if a regulator entertained the idea, the economics are absurd. Nobody is going to finance a duplicate set of poles, wires, and gas mains running down the same streets. Unitil’s franchise is, for all practical purposes, locked in.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Most of what Unitil buys—transformers, poles, cable, meters—comes from a handful of established vendors, and much of it is interchangeable enough that no single supplier can permanently dictate terms. Contractors are similar: competitive most of the time, tight when everyone is building at once. The catch is timing. In the current wave of grid investment, industry-wide constraints have shown up in very real ways, like transformer shortages that delay projects and raise costs. That’s less about suppliers having lasting leverage and more about the entire sector bumping into the same bottlenecks at the same time.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Weirdly high, just not at the individual level. A single customer can’t negotiate rates and can’t switch to another distribution utility. But customers still matter enormously because they vote—and because public utility commissions are built to represent the public interest. Consumer advocates show up in rate cases. Legislators respond when bills spike. Commissioners feel political pressure when increases look excessive. So while customers don’t bargain at the meter, they absolutely exert leverage through the regulatory process.

Threat of Substitutes: Rising. Rooftop solar, batteries, and microgrids are the closest thing utilities have to a real substitute. In theory, a customer with enough generation and storage could leave the grid entirely, though most don’t because it’s expensive and the grid is valuable insurance. The more common shift is partial substitution: customers stay connected but buy fewer kilowatt-hours while still relying on the system for nights, winter, storms, and backup. That’s the version that creates the hardest tension for the utility model—revenue pressure without a matching decline in the cost of maintaining the network.

Competitive Rivalry: Low in the traditional sense, because Unitil doesn’t fight anyone for customers. But there’s still a form of rivalry, and it shows up where utilities actually win and lose: in front of regulators. Commissions and stakeholders compare rates, reliability, storm performance, and operational efficiency across peer utilities. If you’re seen as lagging, you invite tougher scrutiny and less favorable outcomes. If you’re seen as well-run, you earn credibility that matters in the next filing.

Put it together and the picture is broadly favorable for an incumbent like Unitil. Entry threats are negligible. Supplier pressure is real but episodic. Customer power exists, but it’s mediated through politics and trust. Substitutes are the biggest structural challenge, especially as distributed energy spreads.

And the framework also explains the fundamental trade: this protection caps the upside. The same regulatory system that keeps competitors out also limits the ability to earn extraordinary returns. Utilities give up the chance at spectacular margins in exchange for something far rarer in business—stability you can plan around. Whether that’s attractive depends on what an investor wants the rest of their portfolio to do.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Hamilton Helmer’s framework from 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy is a useful way to separate “temporary good execution” from “durable advantage.” When you run it on Unitil, a pretty clear picture emerges: most of the classic Silicon Valley-style powers don’t apply, and the ones that do are deeply tied to regulation and local trust.

Scale Economies: Limited. Yes, utilities have some scale benefits. You can spread certain fixed costs—systems, compliance, back-office functions—across more customers. But those gains flatten out faster than people assume, especially in distribution where the work is inherently local. Unitil is already large enough to operate efficiently as a distribution utility, and going from “regional” to “national” doesn’t magically make a line crew roll faster or a substation upgrade cheaper.

Network Effects: Minimal. Utility networks are physical networks, not demand-side networks. Adding a customer in Concord doesn’t increase the value of service for a customer in Fitchburg. The grid becomes larger, but it doesn’t become more valuable because more people are on it in the way a marketplace or social network does.

Counter-Positioning: Not really applicable. Counter-positioning is what happens when a new entrant adopts a business model the incumbent can’t copy without hurting itself. In a regulated monopoly, there are essentially no meaningful “new entrants” to the core distribution business, and the business model itself is largely defined by statute and commission rules. Everyone plays on the same field.

Switching Costs: Absolute for physical service, softer at the edges. Customers can’t switch to another electric or gas distribution utility; the wires and pipes are the wires and pipes. But customers can switch away from the service in other ways—install solar, add a battery, move to heat pumps, or choose an alternative fuel. And there’s a more consequential kind of “switching” that doesn’t come from individual customers at all: regulators and lawmakers can change the rules, allow municipalization, or reshape what the utility is allowed to earn. In utility land, the real switching risk is political.

Branding: Moderate, and it shows up in the only place that matters. Utilities don’t get premium pricing because they have a beloved brand. But reputation is real currency in rate cases and regulatory proceedings. A utility known for reliability, responsive storm restoration, and straight answers tends to earn goodwill that can influence outcomes over time. Unitil’s operational track record and community presence function like a brand advantage, even if they don’t look like one on a billboard.

Cornered Resource: This is the main event. Unitil’s core power is the regulated monopoly franchise: the exclusive right to serve a defined territory, backed by law and overseen by regulators. You can’t replicate it, and in practice you can’t compete it away. It’s the asset underneath the assets, because it’s what grants access to customers and the opportunity to earn regulated returns on infrastructure investment.

Process Power: Moderate. Running a utility well is a bundle of repeatable, hard-earned processes: operating and maintaining aging infrastructure, coordinating storm response, interconnecting distributed resources safely, managing customer service, and navigating regulatory proceedings with credibility. Unitil’s experience in its specific service territories—and its ability to execute without drama—adds up to real process power. It’s not flashy, but it’s hard to copy quickly.

The Verdict: Unitil is a classic Cornered Resource business, reinforced by brand reputation and process know-how. That also frames the real strategic tension. The franchise is extremely durable—but its value depends on what society asks the grid (and the gas system) to be. If electrification accelerates, the electric franchise becomes more valuable. If distributed generation and behind-the-meter tech meaningfully reduce reliance on the grid, that value can erode at the margin. And the gas franchise faces the sharpest question of all as climate policy evolves.

The 7 Powers lens makes Unitil’s situation feel both safer and more fragile at the same time: protected from conventional competition, but exposed to the one force that can rewrite everything—the political and regulatory system that created the franchise in the first place.

XIV. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

Every investment thesis is really a bundle of bets. The fastest way to understand Unitil is to lay those bets out—what has to go right, what could go wrong, and which assumptions matter most.

The Bull Case:

Electrification is the biggest growth opportunity utilities have seen in decades. In New England, every home that swaps oil or gas for a heat pump, every driveway that adds an EV, and every business that electrifies equipment adds demand to the grid. If the region follows through on its climate goals, the system may need to expand dramatically—potentially doubling or even tripling capacity over time. For a regulated utility, that isn’t just “more sales.” It’s years of new substations, feeders, transformers, and upgrades that flow into rate base.

And crucially, a lot of that growth is policy-driven. State mandates and federal incentives are designed to push electrification forward. If regulators are serious about decarbonization, the grid has to be ready for it. The traditional utility bargain—invest in essential infrastructure and recover costs through rates, with a fair return—has a straightforward way to extend into the energy transition.

Unitil’s small size can also be an asset. In a sector that still consolidates, a well-run, independent utility with constructive regulatory relationships can be attractive to a larger buyer. If Unitil’s board ever chose to sell, investors could see an acquisition premium—especially if the market continues valuing high-quality regulated assets.

Then there’s the “moat” Unitil has been quietly compounding for decades: trust with regulators and communities. In a business where outcomes are negotiated in proceedings and politics, credibility matters. A utility that shows up prepared, communicates clearly, and performs well in storms often earns more constructive engagement—better dialogue, smoother approvals, and less skepticism when it asks to invest.

Funding helps too. Federal programs like the Inflation Reduction Act and various state initiatives are putting real money behind modernization, efficiency, and clean-energy enabling infrastructure. To the extent Unitil can tap those programs, it can reduce the burden on customer rates while still advancing the capital plan that grows rate base.

Operational performance is the other pillar of the bull case. Reliability, customer satisfaction, and storm response aren’t vanity metrics; they become evidence in rate cases and a buffer against political pressure, including the occasional flare-up of municipalization talk. A track record of competence is harder to attack—and harder for a newcomer or distant acquirer to replicate quickly.

Finally, there’s the dividend. Unitil has a long history of paying and growing it. If it continues to compound earnings through steady rate base growth, it can keep attracting the kind of long-term income investors who prize consistency and gradual increases.

The Bear Case:

The biggest risk is that Unitil’s natural gas buildout arrives at exactly the wrong point in history. The company invested heavily in gas distribution in the 2010s—assets designed to last for decades. If policy and consumer behavior shift faster than expected toward electrified heating, parts of that system could become underutilized long before the end of their useful lives. That’s the stranded-asset problem: the pipes remain, the costs remain, but the customer base paying for them shrinks. And while regulation is designed around cost recovery, the treatment of potentially stranded gas infrastructure is uncertain—and could land painfully on shareholders, customers, or both.

Scale is the second big concern. Grid modernization isn’t a one-time upgrade; it’s an ongoing technology transformation. Larger utilities can spread investments in analytics, automation, cybersecurity, and customer platforms across millions of accounts. Unitil has to build many of the same capabilities with a much smaller customer base. If the technology bar rises quickly, the risk is not that Unitil can’t modernize at all, but that it becomes more expensive per customer—and harder to justify in rate cases.

Then there’s the region itself. New England has faced slower population and economic growth than much of the country for years. If that continues—aging demographics, outward migration, limited industrial expansion—Unitil’s organic growth can stay constrained, and electrification may be more substitution than expansion: swapping oil and gas for electricity, without creating much net economic activity.

Politics is another pressure point. As utilities invest more to harden the grid and enable decarbonization, customer bills can rise. Consumer advocates and elected officials have become more vocal, and rate cases can turn into proxy battles over affordability and trust. If that backlash intensifies, commissions may limit increases, compress allowed returns, or slow cost recovery—even as policy still demands more infrastructure investment.

Climate also makes the operating environment harder. New England has always been rough on systems, but more volatile weather can mean more damage, more restoration expense, and more expectations for hardening and resilience. Those costs can climb faster than the regulatory process can absorb, especially in the middle of public frustration over bills.

And finally, investors may conclude the whole exercise isn’t worth the concentration risk. Bigger, more diversified utilities can spread regulatory, weather, and technology risk across broader territories and larger balance sheets. Unitil doesn’t have that diversification, and in a turbulent transition, that can matter.

Synthesis:

The core tension is simple: does Unitil’s focus and local edge beat the advantages of scale during a once-in-a-century infrastructure transition?

Bulls see electrification as so large and so mandated that even a small utility with strong relationships can thrive—especially one that has a reputation for operational discipline. Bears see three compounding risks: a shrinking long-term role for gas, rising per-customer modernization costs, and a political environment that may not tolerate the bill impacts of building what policy demands.

What to watch comes down to a few variables: how quickly electrification actually shows up in winter peak demand, how regulators treat gas investment as policy shifts, and whether Unitil can keep winning constructive rate outcomes while maintaining public trust on affordability.

XV. Current State & Recent Developments (2023–2025)

Over the past couple of years, the utility industry has been forced to run the business while the ground is moving under it. Unitil has dealt with the same pressures as everyone else—higher costs, equipment shortages, and louder politics—while still pushing forward on the investments that set up the next decade.

The first shock has been inflation. After the pandemic, the price of doing basic utility work went up fast: materials, labor, and contractor services all got more expensive. For a company whose job is to steadily rebuild and expand long-lived infrastructure, that matters. It puts pressure on project budgets and forces real choices about pacing—what gets done now, what gets sequenced later, and how to stay disciplined without falling behind on reliability.

Then there’s the supply chain. It’s hard to modernize a grid if you can’t get the hardware. Transformers have been the clearest example, with lead times stretching out as demand for electrical equipment outstripped manufacturing capacity. That doesn’t just slow growth projects; it can become a reliability issue. Unitil has had to plan around those constraints—reworking schedules and getting more creative about how it maintains system readiness when the parts pipeline is unpredictable.

Against that backdrop, rate cases have been front and center. To keep investing and to reflect higher costs, Unitil has sought rate increases. And those requests have landed in a tougher environment. Consumer advocates have been more aggressive, pointing to household budgets already strained by inflation and pushing back hard on bill impacts. The resulting outcomes have been a balancing act: enough recovery to support infrastructure work, tempered by affordability concerns. That tension is real—and it’s exactly where regulatory skill matters most.

On the ground, the capital program has kept moving. Unitil has continued to fund grid modernization and reliability work, with an eye toward electrification. Smart meter deployment has advanced, expanding the data visibility needed to manage distributed energy and changing load patterns. Substation upgrades and circuit automation have strengthened reliability. On the gas side, the company has kept investing in maintenance and safety programs even as long-term policy debates create uncertainty about how big the gas system should ultimately be.

Management has framed its approach as balance: keep both electric and gas systems strong today, while preparing for an increasingly electric future. Unitil has acknowledged the policy uncertainty around natural gas, but it has also emphasized two practical points: much of the gas infrastructure still has decades of service life left, and customers still need reliable heating fuel while the transition plays out in real time, not just in legislation.

For shareholders, the market story has been dominated by interest rates. Unitil’s stock has generally moved with the broader utility sector, which has been highly sensitive to Federal Reserve policy. When rates rose to fight inflation, utilities took valuation pressure because they compete with bonds for income-focused investors. As rate expectations have shifted, those valuations have shifted with them.

Through it all, Unitil has continued its pattern of steady dividend increases. The payout ratio has stayed in a typical regulated-utility range, leaving room to keep funding capital investment while still returning cash to shareholders.

One more constraint has been people. The labor market has been tight, especially for skilled roles like line work. The industry’s aging workforce—already a concern—has seen faster retirements, and replacing that experience isn’t quick. Unitil has responded with training programs, competitive compensation, and succession planning aimed at protecting the company’s operational bench.

Stepping back, the picture is straightforward. Unitil has remained financially sound and operationally solid, dealing with the same inflation, supply constraints, and policy uncertainty facing the whole sector. Its response has been steady and competent—focused on keeping the system reliable now while building the capabilities it will need for the transition ahead.

XVI. The Future: What's Next for Unitil?

Standing at the end of 2025 and looking ahead, Unitil has a few plausible paths—and they don’t just differ in outcomes. They differ in identity. The decisions made over the next decade will determine whether Unitil keeps proving that “small and local” can win, whether it cashes out into a larger platform, or whether it tries to reinvent what a utility can be.