Universal Technical Institute: The Story of America's For-Profit Trade School Powerhouse

I. Introduction: When America Stopped Building with Its Hands

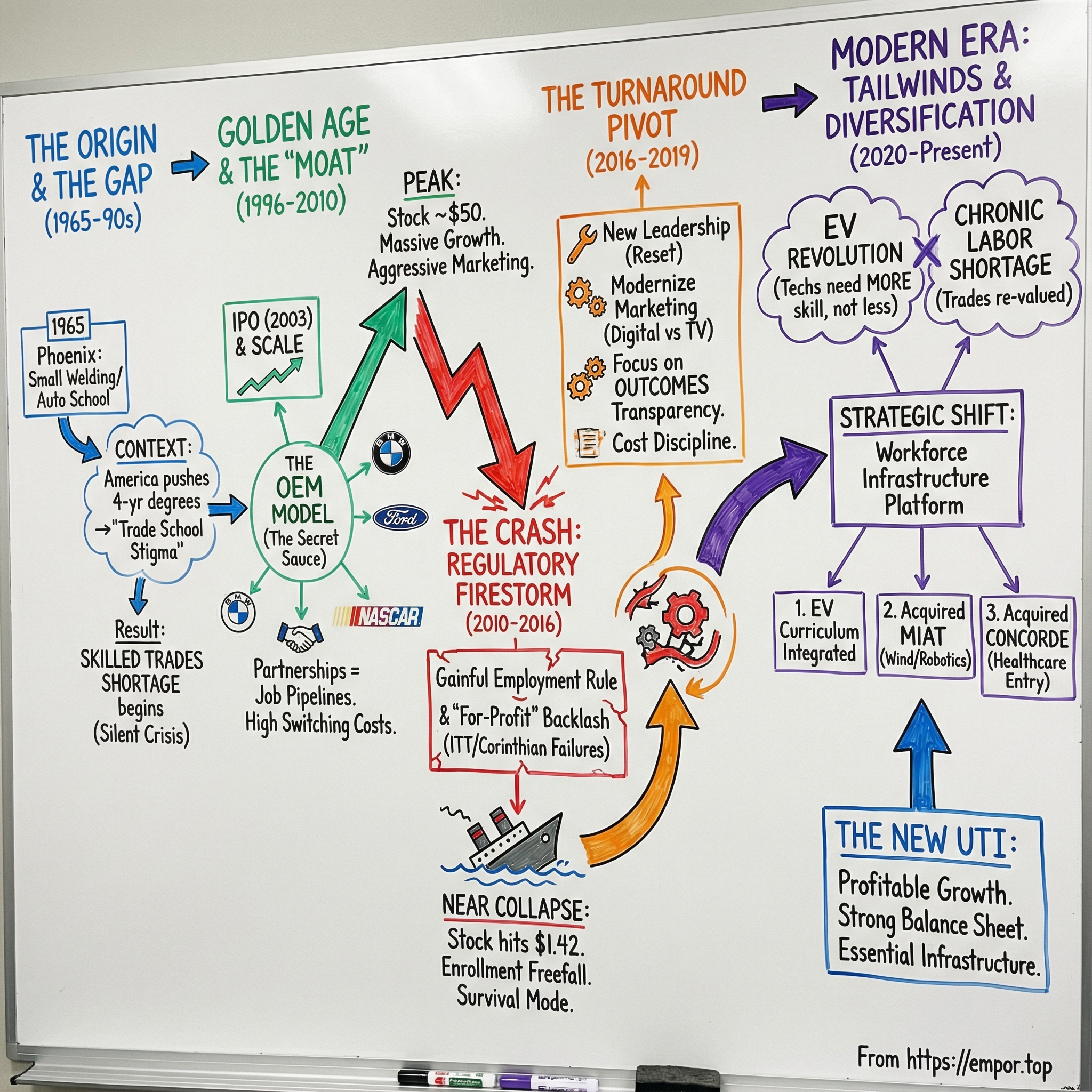

Picture a service bay at a BMW dealership in Scottsdale, Arizona. A 23-year-old technician named Marcus—fresh out of a 12-week, manufacturer-specific program—leans over a BMW i3, laptop open, tracing a fault through the car’s high-voltage system. Three years earlier, he was staring down the familiar fork in the road: pick a four-year college, take on a mountain of debt, and hope a job waits on the other side. Instead, he chose a faster, more direct path into the workforce. Now he’s making about $55,000 a year, with tuition reimbursement helping cover what it cost to get trained, and he spends his days working on some of the most advanced vehicles on the road.

Marcus came through Universal Technical Institute—UTI, if you spend any time around dealerships and repair shops. And UTI’s story sits inside one of the strangest contradictions in the American economy: the country desperately needs technicians—industry estimates call for roughly half a million new automotive techs over the next five years—yet for decades, “trade school” was treated like a fallback. The message was clear: if you were smart, you went to a four-year university; if you didn’t, you worked with your hands.

UTI was founded in 1965 and is headquartered in Phoenix, Arizona. Its stated mission is to serve students, partners, and communities by providing education and support services for in-demand careers. Over time, it has grown into a large, national training platform—one that says roughly 275,000 students have graduated from its campuses.

The question that makes this worth a deep dive is bigger than one company: how did a single Phoenix school turn into a NASDAQ-listed education business with relationships spanning brands like BMW, Tesla, Mercedes-Benz, and NASCAR? And what does UTI’s survival—through the same regulatory and reputational firestorm that took down names like Corinthian Colleges and ITT Tech—tell us about the line between predatory for-profit education and real workforce training?

The timing matters, too. The labor crunch in the skilled trades isn’t theoretical anymore. Demand for automotive service technicians is projected to surge in the years ahead, and broader estimates suggest transportation technician roles could number in the millions over the next five years. At the same time, the EV transition is changing what “being a mechanic” even means: it’s no longer just engines and transmissions, but software, power electronics, and battery systems. And an entire generation is asking—more loudly each year—whether a traditional four-year degree delivers what it promises.

UTI sits right at the intersection of all of it. So let’s trace how it went from a humble welding school to a workforce education powerhouse—and whether its model can hold up as America rediscovers the value of building, fixing, and keeping the modern world running.

II. The Founding Story & Early Years: Phoenix Rising (1965-1990s)

The year was 1965. Lyndon Johnson was in the White House, the Vietnam War was escalating, and in Phoenix, Arizona, a man named Robert I. Sweet decided to start a school.

Universal Technical Institute began as an auto repair training program in a single building, with an initial class of just 11 students. It was modest—almost easy to miss. But Sweet was betting on a shift that was already underway: cars were getting more complex, and the era of the shade-tree mechanic was fading. If vehicles were becoming machines you had to understand, not just tinker with, then training wouldn’t be optional. It would be the job.

The school expanded quickly. In 1968, UTI broadened its offerings with automotive and diesel repair training. The following year, it added air conditioning and heating repair. That mix mattered. Sweet wasn’t just building a “mechanic school.” He was building a place where students could stack practical skills that made them employable in a real shop, in the real world.

Then came a move that, at the time, probably looked like a side hustle—but turned out to be a preview of UTI’s future edge. In 1980, UTI began offering continuing education and training for corporate clients. That same year, it formed a division called the Custom Training Group to provide onsite instruction for corporate technicians. This was UTI stepping out of the classroom and into the employer’s workflow, getting a front-row seat to what manufacturers and dealerships actually needed technicians to know.

The 1980s brought geographic expansion. In 1983, UTI opened a second campus in Houston to train students in automotive and diesel technology. Houston wasn’t a random dot on the map—it put UTI in the orbit of diesel, heavy equipment, and an economy built around machines that have to work. In 1986, UTI added a new building dedicated to its air conditioning technology program. And in 1987, it built out a 14,000-square-foot high-tech facility in Houston to train mechanics for Chrysler, Dodge, and Plymouth dealerships across southern Texas.

That last piece was especially important. It marked UTI’s first manufacturer-specific training relationship—the early version of a playbook that would eventually define the company: embed with brands, tailor curriculum to their standards, and become the place that feeds talent into their service networks.

By 1990, UTI was growing up. Robert Hartman—an 11-year company veteran—was named CEO and, looking ahead, decided the business needed more structure. He added a board of directors to help shape strategy, a sign UTI was moving from founder-led hustle to something more institutional.

The next big leap came at the end of the decade. In early 1998, UTI was recapitalized with an investment from The Jordan Company and senior management to fund the $26.3 million purchase of Clinton Harley Corporation, owner of the Motorcycle Mechanics Institute and Marine Mechanics Institute, better known as MMI. Founded in 1973, MMI had campuses in Phoenix and Orlando, Florida, and it brought something UTI increasingly valued: working relationships with manufacturers like Harley-Davidson, Kawasaki, and Yamaha.

This wasn’t just expansion for expansion’s sake. It was a blueprint: buy complementary schools with real industry ties, then use scale to deepen those relationships and broaden the brand portfolio. Also in 1998, UTI opened a new campus in Rancho Cucamonga, pushing into California and widening its footprint.

By the late 1990s, UTI was no longer a single-building Phoenix school. It had become a multi-campus, multi-program technical education platform—with early manufacturer relationships already taking shape as the foundation for everything that came next.

III. The Private Equity Era & Going Public: Wall Street Discovers Vocational Education (1996-2003)

By the late 1990s, something unusual was happening on Wall Street: investors started paying attention to trade schools.

For years, vocational education had been written off as a slow, unglamorous business—too regulated, too tied to physical campuses, and nothing like the software-style growth investors loved. But a few contrarians looked past the stigma and saw the simple reality underneath: America needed technicians, and community colleges weren’t producing enough of them.

In 1998, UTI was recapitalized with management and investors. The recap wasn’t just about money. It brought tighter governance, more financial discipline, and—most importantly—a mandate to scale. UTI was no longer thinking like a regional training operator. It was starting to think like a national platform.

The early 2000s were about making that ambition tangible. In 2003, UTI announced plans to invest $54.2 million to expand facilities around the country and hire up to 100 new instructors. This wasn’t “steady growth.” It was a pre-IPO buildout—proof to public markets that UTI could add capacity, open campuses, and keep the machine running.

Then came the moment that changed the company’s trajectory. On December 17, 2003, UTI went public at $20.50 per share. The timing worked: for-profit education was hot, investors liked the idea of steady enrollment-driven revenue, and UTI had a story that sounded refreshingly concrete compared to the more speculative education plays that would follow.

That story hinged on something UTI had been quietly building for years: manufacturer relationships that weren’t just partnerships, but pipelines. UTI’s manufacturer-specific advanced training programs—MSAT—gave brands a way to turn students into job-ready technicians trained to the manufacturer’s standards.

The economics were part of the appeal. BMW dealerships, for example, had previously spent as much as $4,000 to train each mechanic, while also pulling experienced staff away from revenue-generating work. Under the UTI model, dealerships would pay the car manufacturer $7,500 per technician for training delivered through UTI. The details varied by program and brand, but the structure mattered: the manufacturer got a scalable training solution, dealers got productive techs faster, students got a credential with real signaling value, and UTI got paid in a way that didn’t rely solely on tuition.

And because these programs were co-developed and embedded into how the brands staffed their dealer networks, they carried a quiet but powerful feature: switching costs. Once a manufacturer invested in curriculum, equipment, and a hiring pathway, replacing UTI wasn’t as simple as choosing a different school.

The IPO gave UTI the fuel to expand fast. In July 2004, it opened a new 160,000-square-foot campus in Exton, Pennsylvania—near Philadelphia—built to accommodate up to 2,000 students and supported by a staff of around 200. To fill those seats, UTI ramped up recruiting, eventually increasing the number of field recruiters to 150.

Also in 2004, the original Phoenix campus moved to a much larger, modern facility in Avondale, Arizona—282,000 square feet—where it offered Automotive Technology II and Diesel Technology II programs.

The buildout continued. In 2005, UTI expanded the Exton campus again with a new 41,000-square-foot facility for diesel and automotive training. It also expanded campuses in Texas, Illinois, Florida, and Rancho Cucamonga, California, and opened new campuses in Sacramento, California, and Massachusetts.

Financially, the market loved what it saw. By 2005, UTI reported revenue of $310.8 million and net income of $35.8 million—results that reinforced the idea that vocational education could be a real, profitable public-company business.

This sprint cemented UTI’s national footprint. But it also introduced a tension that would come back later: when you scale education like a rollout, the pressure to hit enrollment targets rises fast. And once that pressure shows up, marketing spend tends to follow.

IV. The Golden Age: Growth, Partnerships & Market Dominance (2003-2010)

If the post-IPO sprint proved UTI could scale, the years that followed were the payoff. From 2003 through 2010, UTI hit its stride: enrollment climbed, new campuses came online, manufacturer programs multiplied, and the stock traded like this was the clean, industrial version of the for-profit education boom.

The partnership strategy went from “important” to defining. UTI offered Manufacturer Specific Advanced Training through alliances with major names across the industry—brands like BMW, Cummins, Daimler Trucks North America, Ford, GM, Mercedes-Benz, Peterbilt, Porsche, Stellantis (MOPAR), and Tesla.

The template was consistent, and it worked because it aligned incentives. UTI invested in the bays, tools, and instructor training to teach a manufacturer’s systems the right way. The OEM contributed curriculum content and gave the credential real meaning inside its dealer network. And dealers, who were constantly short on talent, hired the graduates. Everyone won—and once that machine was running, it was hard to swap out. Curriculum, equipment, and hiring pipelines don’t move quickly, which created switching costs that quietly protected UTI’s position.

One partnership in particular showed how smart UTI had become about selling the dream, not just the diploma: NASCAR Technical Institute. NASCAR was—and is—an enormous cultural brand. By tying its name to America’s most visible motorsport, UTI earned credibility and attention that regular ads couldn’t buy. Most graduates wouldn’t end up on a pit crew, but they didn’t have to. The point was aspiration. If you could train where NASCAR trained, then a dealership service bay suddenly felt like the first step on a bigger path.

Some of these relationships became multi-decade foundations. UTI’s partnership with BMW, for example, stretched back more than 28 years, and later expanded into EV-focused curriculum to prepare graduates for the complexity of modern vehicles.

Meanwhile, the physical footprint kept growing. With more than 200,000 graduates over its 52-year history, UTI had become the nation’s leading provider of technical training for automotive, diesel, collision repair, motorcycle, and marine technicians. It leaned hard into the idea that its facilities weren’t classrooms—they were working shops, equipped with current technology and built around what employers said they needed.

Enrollment climbed past 18,000 students, and Wall Street rewarded the momentum. The stock even hit an all-time high in the mid-2000s—peaking at $48.50 a share on May 13, 2004.

Underneath that growth was an increasingly industrial recruiting engine. UTI ran television ads built around graduate success stories. It cultivated high school relationships and brought counselors and students onto campuses for tours. It recruited veterans and active-duty military looking for a clean transition into civilian work. And it spent heavily to keep the pipeline full—because in a seat-based education business, every graduating class creates the same problem: empty bays that have to be refilled.

That spending mattered, because UTI was also one of the top recipients of revenue tied to federal student aid and military and veterans education programs—exactly the kind of detail regulators and reporters love to interrogate. In 2009, the company devoted 21.1% of revenue, or $77.3 million, to marketing and recruiting.

At the time, it looked like a growth investment. In hindsight, it was also a warning sign: a cost structure that assumed lead generation would always be available, always be affordable, and always stay politically acceptable.

From the outside, the moat looked real. Manufacturer relationships weren’t easy to replicate. Accreditation took time. Campuses required capital. Instructors were scarce. UTI seemed built for sustained dominance.

But the same forces that lifted UTI into the spotlight were setting it up for a harsher kind of attention. And when the mood shifted, that marketing-heavy model would stop looking like an advantage—and start looking like evidence.

V. The Crisis: Regulatory Crackdown & Enrollment Collapse (2010-2016)

Between 2010 and 2016, the for-profit college industry didn’t just hit a rough patch. It got hit with a regulatory and reputational wave that wiped out entire companies.

Some of the biggest names imploded in public. Corinthian Colleges—at one point serving roughly 110,000 students across about 100 campuses—collapsed. ITT Tech shut down all its institutions, leaving tens of thousands of students stranded. Career Education Corporation closed dozens of locations. An industry that had been celebrated as a growth story suddenly looked, to regulators and the media, like a national scandal.

UTI lived through it—but only barely. To understand how, you have to look at the crackdown itself, and also at the uncomfortable reality that UTI was getting judged in the same courtroom as far worse actors.

For-profit higher education had grown explosively. Department of Education figures showed that from 1990 to 2010, enrollment at for-profit colleges jumped about 600%. By the end of that run, nearly 2 million students—around 12% of all postsecondary students—were enrolled in the sector.

That growth brought scrutiny for a reason. By the late 1980s, default rates were surging, and it became hard to ignore that the student loan system was being abused. A GAO investigation found that 74% of the fraud and abuse occurred at for-profit institutions, and that students at those schools accounted for 77% of the defaults.

The Obama administration’s response became a four-word threat hanging over the whole sector: gainful employment. The rule required career programs to show that graduates earned enough to reasonably repay their student debt. If a program failed the metrics, it risked losing access to federal financial aid—essentially an existential event for schools that relied on Title IV.

UTI was pulled into that broader spotlight. The Senate HELP Committee’s report on the industry examined UTI alongside the worst offenders. It noted that Department of Defense Tuition Assistance and Post-9/11 GI Bill funds made up about 2.5% of UTI’s revenue, or $10.9 million. It also pointed out that UTI’s profit had risen quickly—growing from $23.7 million in 2007 to $46.6 million.

Then came the kind of comparison that sticks in headlines. The committee found that a certificate in Automotive Technology at UTI cost $30,895, versus $1,527 at a nearby community college—about twenty times more. It also estimated that roughly 75% of UTI revenue (about $330 million) was derived from federal student aid plus military and veterans education programs. In the middle of a political firestorm about taxpayer-backed loans, those numbers weren’t just financial details—they were targets.

But UTI’s story didn’t fit neatly into the “diploma mill” frame. Its outcomes data, while far from perfect, looked meaningfully better than much of the sector it was grouped with. UTI reported that 36.2% of students who enrolled in 2008–09 had withdrawn by 2010—still high, but well below the 54.1% average among the 30 companies the committee examined. Its default rate fluctuated, but closely tracked broader school default rates, suggesting that many students were getting to work.

UTI also looked different operationally. In 2010, unlike the other companies surveyed, it used an almost entirely full-time faculty—only 3% were part-time. In a sector where heavy reliance on adjunct instructors was often a cost-cutting move that raised quality concerns, that mattered.

And regulation wasn’t the only headwind. The economy itself turned against the model. Vocational schooling tends to be counter-cyclical: when unemployment is high, people go back to school; when jobs are plentiful, they often take work now instead of training for later. As the economy improved, UTI faced a painful combination of weaker demand and harsher oversight, all at once.

Then the floor fell out. Enrollment dropped sharply. The stock followed it down. On October 11, 2016, UTI hit an all-time low of $1.42 a share. A company that once traded near $50 was now priced like a failed experiment.

When your business is built on filling seats in physical campuses, that kind of collapse forces ugly choices. UTI closed unprofitable locations. It cut marketing, which only tightened the enrollment funnel further. Leaders departed. Debt covenants limited flexibility just when the company needed it most.

And yet—UTI didn’t die.

The simplest reason is also the hardest to fake: outcomes. More students finished than at many peers. Graduates found jobs. Employers kept hiring. And the manufacturer relationships UTI had built over decades acted like a stamp of legitimacy that regulators couldn’t easily wave away. When brands like BMW and Mercedes-Benz were actively recruiting UTI grads into their dealer networks, it became harder to sell the idea that UTI was just printing credentials.

That didn’t make UTI immune. But it did give the company something many for-profit schools didn’t have when the crackdown arrived: proof that the training was connected to real work.

VI. The Turnaround Begins: New Leadership & Strategic Reset (2016-2019)

Rock bottom often comes with a kind of clarity. For UTI, the inflection point wasn’t a single regulatory win or a lucky quarter—it was a leadership reset, followed by a brutally honest look at what had stopped working.

On November 27, 2017, Universal Technical Institute brought in Jerome Grant as Chief Operating Officer, reporting to then-President and CEO Kim McWaters. The signal was clear: UTI needed an operator who could rebuild the engine, not just manage the decline.

Grant didn’t come up through the for-profit trade school world. His background was in education and digital transformation. He had launched McGraw-Hill’s higher education services business and helped lead Pearson Higher Education’s early shift to digital. He also spent more than a decade as President of Pearson’s Business and Technology skills division, where he grew the business to more than $425 million in revenue and generated more than $112 million in EBITDA. He knew how to modernize an education business—and how to do it with metrics, systems, and discipline.

In the newly created COO role, Grant was tasked with executing UTI’s next chapter: reignite enrollment, diversify programs, expand industry relationships, and rethink the campus footprint—from the old model of large “destination” campuses toward smaller commuter campuses. In the early days, his focus was intensely practical: work with marketing and admissions to rebuild new student growth in a market that still needed technicians, even if the public narrative had turned toxic.

The first step was diagnosis—and the findings weren’t subtle. UTI’s marketing machine had hardened around broadcast television: expensive, blunt, and increasingly disconnected from how younger students actually discovered and evaluated schools. The enrollment funnel leaked potential students at every stage. And the cost structure still looked like the growth years, even though the company was fighting just to stabilize.

So the turnaround wasn’t one big bet. It was a coordinated set of fixes, pushed through at the same time:

Marketing Transformation: UTI shifted away from broadcast TV toward digital marketing, supported by CRM systems that tracked prospects from first inquiry through enrollment. The goal was simple: stop buying attention broadly and start building a measurable pipeline—improving conversion while lowering acquisition costs.

Outcome Transparency: Instead of treating disclosure like a regulatory burden, UTI leaned into it. Publishing job placement rates and graduate salary information became a way to stand apart from competitors that didn’t want to be pinned down by outcomes.

Campus Rationalization: UTI closed or consolidated underperforming locations. It wasn’t glamorous, but it reduced fixed costs and concentrated investment where the model still worked.

OEM Partnership Deepening: Manufacturer relationships stopped being a nice-to-have proof point and became the core asset around which everything else was built. The message was: this is not generic training—this is a pipeline into real employer demand.

Program Diversification: Expanding welding helped tap a parallel skilled trades shortage and reduced reliance on automotive alone.

By 2019, McWaters was publicly framing the turnaround as real—and durable. She said: "Given UTI's significant transformation over the past two years and the upward trajectory projected for 2020, the company is now well positioned for a new phase of profitable growth. My decision to move into a non-executive role at this time reflects my strong confidence in Jerome Grant and his management team. Jerome served as a principal architect and leader of UTI's transformation effort, which has reshaped the organization's marketing, operational execution and industry engagement and helped drive UTI's turnaround."

That same year, the leadership handoff became official. In October 2019, McWaters retired as CEO effective October 31 and stayed on the Board as a non-executive director. On November 1, 2019, Jerome A. Grant—then Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer—became Chief Executive Officer and joined the Board.

McWaters’ own arc said something about UTI’s internal culture. She spent 35 years at the company, starting as a receptionist in 1984 and rising to President and CEO. UTI didn’t abandon institutional knowledge in a crisis; it kept it close, while bringing in outside expertise—like Grant’s—to modernize how the business ran.

Financially, the recovery was steady rather than dramatic. Debt refinancing extended maturities and eased covenants. Cost discipline improved margins even without rapid top-line growth. By late 2019, UTI had moved from pure survival to cautious forward motion—and it was about to run into a catalyst no one had planned for.

VII. The EV Revolution & Strategic Positioning (2018-2022)

While UTI was rebuilding its internal engine, the automotive industry was entering the biggest transition since the internal combustion engine made the horse obsolete. EVs were moving from novelty to inevitability. Tesla’s Model 3 proved you could sell an electric car at scale. Legacy automakers started committing billions to electrification. Governments began floating, and in some places setting, timelines to phase out combustion engines.

If you trained technicians for a living, that wave looked like it could be existential. EVs have fewer moving parts. They need less routine maintenance. And with over-the-air updates, it became fashionable to ask whether cars would start “fixing themselves.” Was UTI training people for a shrinking job?

UTI’s leadership made a different bet: electrification wouldn’t remove the technician. It would rewrite the job description. High-voltage battery packs require rigorous safety procedures. Power electronics and software-driven diagnostics demand a new kind of troubleshooting skill. And even in the most aggressive EV future, America’s massive installed base of vehicles wasn’t going anywhere overnight. The country would be servicing combustion engines for decades, even as EVs gained share.

So UTI moved early. As consumers, manufacturers, and policymakers converged on a zero-emissions future, the company updated its curriculum to add Hybrid and Electric Vehicle technician coursework, starting at its California campuses. It wasn’t a one-off class—it was positioned as the front edge of a broader EV strategy: expand EV content inside the core Automotive Technology program, push manufacturer-specific advanced training deeper with partners, and develop new training models and partnership opportunities that matched where the industry was heading.

The way they built that curriculum mattered. UTI didn’t design it in a vacuum; it collaborated with an EV Program Advisory Council that included major manufacturers like Ford, Volvo, BMW, and GM, plus employers and industry leaders such as Crown Lift, Southern California Edison, Bosch, and others. The message was clear: this wasn’t academic theory. It was job-aligned training shaped by the companies hiring the graduates.

The BMW partnership showed what that looked like on the ground. Across all seven UTI campuses offering FastTrack, students began learning the new EV curriculum using BMW i3 vehicles supplied by BMW. The training—developed by BMW North America—was built to prepare technicians for high-voltage BMW Group vehicles. Students learned charging modes and settings, how to estimate charging times, how to perform pre-delivery inspections, when to charge a 12-volt battery, how to assess vehicle safety, and how to evaluate whether a given concern required high-voltage qualifications.

BMW’s motivation tracked perfectly with UTI’s thesis. “BMW currently offers four fully electric, and an additional four plug-in hybrid electric vehicles for sale in the U.S. with the expectation that both our electric line-up, and sales will only continue to grow,” said Gary Uyematsu, national technical training manager, BMW of North America. “Our partnership with UTI will not only help ensure that we can meet the need for skilled technicians but also provide the premium level of customer service BMW drivers expect.”

Then came COVID-19—the ultimate stress test for a hands-on training business. Campuses closed. Shop time was interrupted. Students hesitated, unsure whether programs would be delayed or whether it was smarter to take work immediately in an uncertain economy.

But the pandemic also forced progress UTI had already started. Marketing got sharper and more digital. Virtual campus tours helped reach prospects who couldn’t visit in person. Back-office processes that had been stubbornly manual were digitized because they had to be.

At the same time, UTI kept pushing its diversification play. The company completed its acquisition of MIAT College of Technology for $26 million in cash. “On behalf of everyone at UTI, I am excited to officially welcome MIAT’s management, staff, students, faculty, and alumni to the team,” said CEO Jerome Grant. “Completing this acquisition represents an important initial step in executing our growth & diversification strategy. It allows us to further expand our program offerings nationwide into growing fields that we believe will continue to be bolstered by technological advances and the global focus on sustainability.”

MIAT brought programs in aviation maintenance, wind power, robotics and automation, non-destructive testing, HVACR, and welding—fields with their own technician shortages and their own version of the “skills gap” problem UTI knew well. It was a strategic hedge against concentration in automotive, and a deliberate step into energy and industrial technology as the economy electrified.

By 2022, UTI had largely changed what it represented. It wasn’t just a for-profit school trying to outrun a stigma. It was positioning itself as workforce infrastructure—an institution built to produce the technicians the modern economy couldn’t function without.

VIII. Modern Era: Profitable Growth & The New UTI (2022-Present)

On December 1, 2022, UTI closed what it called its most transformative deal yet: a $50 million all-cash acquisition of Concorde Career Colleges. Overnight, UTI moved beyond transportation and the skilled trades and planted a flag in healthcare education—another corner of the economy where labor shortages are chronic and training has to be practical, structured, and job-linked.

Concorde brought real scale. The acquisition included 17 campuses across eight states serving roughly 8,000 students. For the trailing twelve months ended September 30, 2022, Concorde reported unaudited revenue of approximately $200 million and adjusted EBITDA of approximately $17 million.

The strategic logic was straightforward. Healthcare shortages can be as severe as the technician crunch in transportation. The operating model—campus-based, hands-on training with clear pathways into employment—rhymed with what UTI already knew how to run. And the combination turned UTI into something broader than an “auto tech school”: a diversified workforce education platform.

After closing Concorde, the company began operating and reporting as two divisions. One was Concorde, focused on healthcare programs and campuses, led by Divisional President Jami Frazier reporting to CEO Jerome Grant. The other remained Universal Technical Institute, encompassing UTI as well as MIAT College of Technology, Motorcycle Mechanics Institute, Marine Mechanics Institute, and NASCAR Technical Institute.

The numbers that followed suggested the bet was working. In fiscal 2024, the company reported revenue of $732.7 million, up 20.6% year over year, with $486.4 million from the UTI division and $246.3 million from Concorde. Net income rose to $42.0 million, and adjusted EBITDA reached $102.9 million. New student starts also climbed, totaling 26,885 for the year.

Fiscal 2025 kept the momentum going. UTI delivered $835.6 million in revenue, up 14% year over year, and said it exceeded the upper end of its previously raised guidance for net income, earnings per share, and revenue. The company also reported double-digit growth in both average full-time active students and new student starts. Adjusted EBITDA came in at $126.5 million, even as UTI absorbed more than $6 million in intentional growth investments tied to new campuses and program expansion.

For the full year 2025, net income was $63.0 million and adjusted EBITDA was $126.5 million, up 22.9% from the prior year.

With growth returning, management started speaking less like a company in recovery and more like one in build mode. It offered forward guidance that separated “baseline” earnings power from what it planned to reinvest: baseline adjusted EBITDA, excluding planned growth investments, was expected to exceed $150 million, while reported adjusted EBITDA was projected between $114 and $119 million, reflecting roughly $40 million of growth investments for new campuses and program launches. UTI framed those investments as deliberate and high-return—pressure on margins now in exchange for capacity and earnings later. Looking further out, the company said it expected to surpass $1.2 billion in annual revenue and approach $220 million in adjusted EBITDA by fiscal 2029.

The regulatory picture also began to thaw. After discussions with the Department of Education, the company satisfied the agency’s requirements under its Provisional Program Participation Agreement, lifting the core growth restrictions on the Concorde division.

Management pointed to the macro tailwinds behind the turnaround. “Fueled by increasing demand for skilled-collar jobs and strategic investments to expand the consolidated UTI brand, results continued to meet or exceed expectations,” Jerome Grant said, adding that strong performance and “a regulatory environment that is increasingly favorable to our mission” supported raising guidance for fiscal 2025.

And in 2025, UTI got to tell a different kind of story than it was telling in 2016. The company marked 60 years of operation, with Grant and his leadership team ringing The Opening Bell of The New York Stock Exchange. “This anniversary milestone is significant for both our rich history and our successful transformation into an American leader in workforce education,” Grant said. “What initially began 60 years ago as a training program with five students is now a multi-division company that educates tens of thousands of students annually.”

Most importantly, the balance sheet no longer read like a company fighting for air. As of September 30, 2025, available liquidity was $254.5 million (cash $127.4 million, short-term investments $41.8 million, and $85.4 million under its revolver), while total debt was $87.1 million. Less than a decade after flirting with collapse and wrestling with covenants, UTI was operating from a position of financial strength.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive: How UTI Actually Makes Money

To really understand UTI, you have to look past the campuses and the branding and into the machine underneath. UTI isn’t quite a college, and it isn’t quite a corporate training company. It’s a hybrid: a campus-based education business that sells a faster, job-linked path into specific careers—and reinforces that promise through deep employer partnerships.

Revenue Composition

Most of UTI’s revenue still comes the old-fashioned way: tuition. But the company also adds revenue through housing, tool sales, and various forms of employer and manufacturer sponsorship.

Operationally, UTI runs as two segments: the UTI division and the Concorde division. Across them, the company offers certificate, diploma, and degree programs. It also runs manufacturer-specific advanced training programs in a few different flavors: student-paid electives delivered on UTI campuses, plus manufacturer- or dealer-sponsored training delivered at campuses and dedicated training centers.

That two-division setup matters for stability. Transportation and skilled trades don’t always move in the same cycle as healthcare, so UTI isn’t betting the whole company on a single labor market staying hot.

The OEM Partnership Model

If UTI has a signature move—its version of the thing no one else can easily copy—it’s Manufacturer Specific Advanced Training, or MSAT.

These programs are built with major brands like BMW, Ford, and GM to train students on that manufacturer’s vehicles, systems, and technologies. Each program is brand-specific, but the broader value to the student is portability: you’re learning modern diagnostic processes and advanced systems that translate across the industry, even if the badge on the curriculum is a specific OEM.

UTI has relationships with more than 30 brands, and MSAT is the clearest way those relationships become an engine, not just a logo wall.

The incentive alignment is the whole point. Manufacturers and dealers get technicians who can contribute faster, without months of ramp-up. Dealers avoid the cost and productivity drag of training from scratch. Students graduate with a credential that signals “job-ready” in a way a generic program often can’t. And UTI benefits twice: it earns tuition and it strengthens partnerships that drive credibility, referrals, and demand.

Student Financing

Like most for-profit education, UTI relies heavily on federal financial aid. That support makes it possible for many students to attend—and it creates a constant regulatory backdrop that the company has to manage carefully.

The military is another meaningful part of the mix. UTI offers military and veteran support services like military-focused admissions representatives, military-only orientations, and dedicated lounge areas for veterans. Many programs are also approved for GI Bill funding.

Unit Economics

The economics of this business look a lot more like running a chain of specialized facilities than like running an online education product.

Campuses have large fixed costs: buildings, bays, equipment, vehicles, and instructors with real-world experience. Once those costs are in place, profitability becomes a capacity game. A campus that’s mostly full can look very healthy; a campus running well below capacity can turn into a problem quickly.

That creates operating leverage in both directions. When enrollment grows, margins can improve fast. When enrollment shrinks, the same cost structure can squeeze you just as quickly. And because enrollment is driven by recruiting, marketing is never just a one-time launch expense—it’s an ongoing input to keep the bays full.

Why This Model Is Hard to Replicate

On paper, UTI is “just” training. In practice, it’s training with a stack of barriers around it:

-

Accreditation: Each UTI campus is accredited by the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges (ACCSC). That status takes years to earn and maintain.

-

Physical Infrastructure: You can’t scale hands-on training without shops, equipment, and vehicles—real capital, not just curriculum.

-

Instructor Talent: Instructors who have industry credentials and can teach effectively are scarce.

-

OEM Relationships: The manufacturer partnerships took decades to build, and they’re not plug-and-play for a new entrant.

-

Regulatory Compliance: Access to Title IV funding requires a compliance apparatus that’s expensive, complex, and hard to stand up quickly.

Comparison to Alternatives

Students do have options. Community colleges can offer similar training for less money, but often with longer time-to-completion and without the same manufacturer-specific signaling. Online bootcamps can teach pieces of technical knowledge, but they can’t replicate lab time and shop experience. Apprenticeships exist, but they’re limited in scale and don’t always come with formal credentials.

That’s the lane UTI has spent decades carving out: faster, employer-aligned training, delivered at scale, with industry brands acting as both validator and distribution.

X. Competitive Landscape & Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

On paper, “starting a trade school” sounds straightforward. In reality, UTI is protected by a stack of friction that’s hard to shortcut.

Accreditation can take years. Building real shop-floor capacity means real capital: bays, lifts, diagnostic tools, late-model vehicles, safety equipment, instructors, and the facilities to run it all. And the relationships that matter most—the OEM pipelines—aren’t something you buy off the shelf. They’re built over time, through curriculum alignment and trust.

That said, the threat isn’t zero. Community colleges could expand vocational programs if they get the funding and urgency. Employers can pull training in-house and skip the school entirely. And over time, technology may let more of the “book” portion move online, lowering the barrier for certain parts of the education experience.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM

UTI’s supplier set isn’t just vendors—it’s people and partners.

Yes, there are equipment makers, and specialized automotive training gear doesn’t come from an infinite number of sources. And curriculum development increasingly happens alongside OEMs, which creates a kind of mutual dependence: UTI needs their systems and standards, and OEMs need UTI’s scale and delivery.

But the real choke point is instructor talent. In 2010, UTI employed an almost entirely full-time faculty, with only 3% part-time. That commitment can support consistency and quality—but it also makes the instructor shortage hit harder. Experienced technicians who can teach are rare, and they have plenty of other options in the industry. When those people get expensive or hard to hire, everyone in the category feels it.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Students): MEDIUM-HIGH

Students aren’t captive customers. They can go to community colleges for less. They can try to get hired and learn on the job. They can come out of military technical training already ahead of the curve. And there are other for-profit schools competing for the same cohort.

That makes price sensitivity real—especially when student debt is part of the decision. UTI earns its tuition when the outcomes are clear: students finish quickly, get placed quickly, and earn wages that make the investment feel rational.

UTI’s counterweight is differentiation. If a student wants an accelerated path and a manufacturer-specific credential that plugs into a dealer network, the menu of true substitutes gets shorter—and buyer power drops.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

The substitutes are everywhere, and many of them are improving:

-

Community colleges can be dramatically cheaper. The Senate HELP Committee highlighted one nearby example: an automotive certificate priced at $1,527 versus $30,895 at UTI. That gap is hard to ignore, even if timelines, intensity, and industry signaling aren’t the same.

-

Employer apprenticeships and internal training are an increasingly serious alternative, especially as the technician shortage pushes companies to build their own pipelines.

-

Military technical training can deliver excellent preparation, with the cost covered for service members.

-

High school vocational programs still exist in some districts, even if the broader trend has been decline.

-

Online learning can cover theory and diagnostics concepts, but it can’t replace hands-on lab time—at least not yet.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM

UTI isn’t alone. Its closest large-scale peer is Lincoln Educational Services (Lincoln Tech), a for-profit vocational education group headquartered in Parsippany, New Jersey, with campuses owned and operated by Lincoln Educational Services Corporation (Nasdaq: LINC).

Lincoln’s roots rhyme with UTI’s: it started in 1946 in Newark, New Jersey, training World War II veterans for civilian careers, including installation and servicing of air conditioning and refrigeration equipment. Today, it competes in many of the same workforce-training lanes—similar mission, similar student profile, smaller scale.

But this isn’t a winner-take-all category. Training is constrained by geography, facilities, and local employer demand. Multiple players can coexist because students don’t relocate as freely as they do for a four-year college, and because programs tend to specialize by campus and region. In practice, rivalry shows up less as price wars and more as a battle of marketing efficiency, employer relationships, and—ultimately—graduate outcomes.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s framework is a useful way to separate “good business” from “durable advantage.” When you run it on UTI, you get a clear answer on where the real power lives—and where it doesn’t.

Scale Economies: MODERATE

UTI has meaningful fixed costs: campus infrastructure, equipment, curriculum development, and a marketing and admissions engine. Spread those costs across more students, and the model gets more efficient. A national footprint can also create marketing leverage—one campaign can support multiple campus markets, and centralized administration can serve the whole system.

But the ceiling on scale is real. Education is delivered locally. A campus in Georgia doesn’t materially lower the cost of running Arizona. You can centralize some functions, but you can’t centralize shop bays.

Network Effects: WEAK

There’s a hint of network effect: alumni placed in dealerships may be more likely to hire other UTI grads, and employers that repeatedly get good hires become tighter partners over time. More graduates can deepen those relationships.

Still, this isn’t a true network effects business where each new user directly increases value for every other user. The flywheel exists, but it’s modest.

Counter-Positioning: HISTORICAL (FADING)

For a long time, UTI had a real counter-position against traditional public options like community colleges: faster programs, more flexible scheduling, and aggressive outreach to students who weren’t being served by the conventional pipeline.

That edge has softened. Community colleges have improved flexibility in some markets, and the for-profit label carries reputational baggage that didn’t weigh as heavily in the mid-2000s. Counter-positioning helped UTI in 2005; it matters less now.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

Once students are in, switching is painful. Credits often don’t transfer cleanly, time is lost, and financial aid can be complicated to unwind and restart. That creates real stickiness mid-program.

On the partner side, OEMs also face switching costs. If a manufacturer has invested in UTI-specific curriculum, equipment alignment, and a credentialing pathway into its dealer network, moving that whole system elsewhere is expensive and disruptive.

But there’s an important caveat: new prospective students have no switching costs. Before enrollment, they can choose any alternative.

Branding: MODERATE

Inside the automotive and diesel world, UTI’s name carries weight—especially with employers. And the association with OEM brands like BMW, Mercedes-Benz, and NASCAR adds legitimacy that generic trade schools don’t always have.

At the same time, for-profit stigma is a headwind with certain students and parents. The sector’s reputation—often earned by bad actors—spills over onto everyone, including schools with better outcomes.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE-STRONG

This is the core of UTI’s power. The company has several resources that are difficult to recreate quickly:

-

Exclusive OEM Relationships: Long-running partnerships with brands like BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Ford, and GM bring curriculum, credentials, equipment, and hiring pipelines that competitors can’t easily replicate on short notice.

-

Accreditation and Regulatory Approval: Each UTI campus is accredited by the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges (ACCSC). New entrants don’t just need a building and instructors—they need years of approvals and compliance infrastructure.

-

Physical Infrastructure: Facilities like the 125,000-square-foot MIAT campus in Canton, Michigan—and the broader network of hands-on campuses—represent capital and time that can’t be matched overnight.

-

Institutional Knowledge: Six decades of curriculum iteration, enrollment optimization, and employer relationship management is accumulated know-how that shows up in execution.

Process Power: MODERATE

UTI has built repeatable systems: recruiting and admissions processes, student support, and the ability to collaborate with OEMs on curriculum and training delivery. Those processes can translate into better outcomes than a newcomer could achieve right away.

But process power rarely stays exclusive forever. A determined competitor can copy systems over time. There’s no secret formula—just execution, investment, and patience.

Power Summary

UTI’s moat is anchored in Cornered Resource—especially OEM relationships, accreditation, and physical infrastructure—with additional support from Scale Economies and Switching Costs. It’s defensible, but not bulletproof. Substitutes and shifting perceptions will always apply pressure, which means UTI has to keep reinvesting in outcomes and partnerships to hold its ground.

XII. The Bear vs. Bull Case: Competing Visions of UTI's Future

The Bull Case

Bulls look at UTI and see a company that’s finally aligned with the direction of the labor market—and supported by macro tailwinds that don’t feel temporary.

Structural Technician Shortage: Start with the simplest driver: there still aren’t enough technicians. The 2022 TechForce Foundation Technician Supply and Demand report showed employed auto technicians recovering to about 733,200, up 4% from the 2020 low. But TechForce still argued the industry was far short of what it would need by the end of 2024—on the order of hundreds of thousands of technicians.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics adds another layer to that story, projecting more than 67,000 automotive technician job openings per year in the U.S. from 2022 to 2032.

To bulls, this isn’t just a “hot jobs market” blip. It’s demographic. Experienced technicians are aging out faster than new ones are coming in.

EV Transition Creates Opportunity: Electrification, in this view, isn’t a threat—it’s an upgrade to UTI’s value proposition. High-voltage systems raise the bar on safety and specialization. Hybrids demand technicians who can handle both worlds: traditional mechanical systems and electric powertrains. Complexity becomes a reason to train, not a reason to skip training.

Cultural Shift Toward Trades: The four-year college default path is losing its monopoly on prestige. Student debt is under a microscope, and “learn a skill, get paid” is sounding less like a fallback and more like a plan. As the technician shortage has dragged on, it’s also notable that TechForce has reported more students pursuing automotive technician training for a second year in a row. Layer on the auto industry’s shift toward electrification, and the job starts to look more like working in high-tech systems than turning a wrench in a greasy bay—which can be a meaningful recruiting unlock for young people.

Proven Operational Excellence: Bulls point to the turnaround itself as evidence. UTI rebuilt marketing, stabilized operations, and integrated acquisitions—things that sound straightforward until you watch how many companies can’t do them under pressure.

Financial Strength: The balance sheet is no longer a constraint. As of September 30, 2025, UTI reported $254.5 million in available liquidity and $87.1 million of total debt. Compared to the covenant-stressed days of the mid-2010s, that’s a different category of optionality.

Growth Trajectory: Management’s long-term targets reinforce the bullish narrative: by fiscal 2029, UTI expects to surpass $1.2 billion in annual revenue and approach $220 million in adjusted EBITDA.

The Bear Case

Bears don’t deny the turnaround. They argue the story is still fragile—because the same industry dynamics that nearly killed UTI once can come back in different forms.

Regulatory Risk Never Disappears: For-profit education is a political lightning rod. A change in administration can tighten rules quickly, including versions of gainful employment. State attorneys general can be aggressive. And the sector has a contagion problem: one scandal elsewhere can trigger scrutiny everywhere, even for operators with better outcomes.

Community College Competition: Bears come back to the uncomfortable truth the Senate HELP Committee highlighted years ago: public alternatives can be dramatically cheaper. If community colleges expand vocational capacity—an idea with bipartisan appeal—UTI has to keep proving that speed, structure, and employer pathways justify the premium.

Demographic Headwinds: In many regions, the 18–24 population is shrinking. That means UTI needs to win a bigger share of a smaller pool, pull more students from older demographics, or keep expanding into new program categories and geographies.

Economic Sensitivity: The demand curve cuts both ways. When jobs are plentiful, some prospects skip school and take paychecks now, which can pressure starts. In recessions, enrollment can rise—but so can default risk and regulatory attention.

EV Transition Could Reduce Long-Term Demand: The same electrification wave bulls celebrate has a bearish long-game argument. EVs have fewer moving parts and, in some cases, less routine maintenance. More functionality shifts to software. Even if the transition period is rich with retraining needs, a steady-state EV fleet could mean fewer technician hours per vehicle over time.

Margin Pressure: UTI is investing heavily to grow, and that shows up in near-term profitability. Reported adjusted EBITDA is projected between $114 million and $119 million, reflecting about $40 million of growth investments for new campuses and program launches. The bet is that those investments pay back. Bears underline the obvious: not all expansions do.

OEM Concentration Risk: Manufacturer relationships are one of UTI’s greatest assets—but they’re also points of dependency. If a major partner like BMW walked away, the impact would be meaningful, both operationally and reputationally.

XIII. Key Metrics to Watch

If you want to track whether UTI’s momentum is real—and whether it’s sustainable—three metrics do most of the work.

1. New Student Starts (Growth & Quality)

New student starts are the top of the funnel for everything that follows. Each start becomes tuition revenue over the life of a program, so when starts rise, future revenue usually follows. They also tell you whether marketing is working, whether the brand is resonating, and whether the company is filling its fixed-cost campus footprint efficiently.

But starts aren’t just about volume. Quality matters. Students who persist and complete drive full tuition and stronger outcomes; students who withdraw early can turn expensive recruiting into sunk cost.

In fiscal 2025, UTI reported average full-time active students of 24,618 (up 10.5% year over year) and total new student starts of 29,793 (up 10.8%).

Watch for: quarter-to-quarter direction, performance versus guidance, how starts split between the UTI and Concorde divisions, and any hints about conversion rates and withdrawals.

2. Graduate Outcomes (Placement Rates and Starting Wages)

In a business like this, outcomes aren’t a nice-to-have. They’re the product.

Strong placement rates signal that employers still want the graduates and that the curriculum matches what the market needs. Starting wages matter just as much, because they determine whether the student’s ROI feels real—and whether regulators view the programs as meeting “gainful employment” expectations.

Outcomes also feed the next cohort. When graduates land good jobs, the school’s reputation compounds. When they don’t, you see it in reviews, complaints, and eventually in enrollment.

Watch for: placement rates by program, starting wage trends versus prior cohorts, and any regulatory commentary tied to outcomes or compliance.

3. Adjusted EBITDA Margin (Operational Efficiency)

Adjusted EBITDA margin is the clearest snapshot of how efficiently UTI is running the machine: how much of each revenue dollar is left after operating costs. Improving margins usually mean better marketing efficiency, better campus utilization, and tighter cost discipline. Shrinking margins can point to competitive pressure, softer enrollment, or investment spending that isn’t paying back—yet.

UTI also asks investors to separate “baseline” profitability from “reported” results. The company said baseline adjusted EBITDA, excluding planned growth investments, was expected to exceed $150 million. That distinction matters: it’s the difference between what the business can generate today and what it’s choosing to reinvest for tomorrow.

Watch for: margin trends by division, marketing cost per start, and how management bridges baseline versus reported EBITDA over time.

XIV. Lessons & Playbook

For Founders & Operators

Build moats through exclusivity: UTI’s OEM partnerships weren’t a marketing gimmick. They were built over decades—through co-developed curriculum, equipment investment, and trust—and they became hard to replace. The playbook here is simple: find the relationships that can become structurally exclusive in your industry, then earn them over time. The payoff often shows up long after the first dollars go out the door.

Survive regulatory cycles through transparency: When an industry comes under attack, the instinct is to go quiet. UTI’s survival suggests the opposite can be smarter. If your outcomes are real, publish them and let them stand up to scrutiny. If they aren’t, treat transparency as the forcing function to fix the product—because regulators, reporters, and customers are going to ask anyway.

Turnarounds require brutal honesty: UTI didn’t get better by tweaking around the edges. The reset worked because leadership treated the situation like a full-system failure—marketing, funnel conversion, campus footprint, and cost structure—and rebuilt it accordingly. In a true turnaround, incrementalism is often just a slower way to lose.

Ride macro waves: Electrification could have made UTI feel obsolete overnight. Instead, the company reframed itself around what the wave demanded: new technician skills, new safety standards, new curricula, and new employer urgency. Big shifts don’t just create threats; they create new categories of winners. The difference is whether you reposition early enough to be one of them.

Unit economics eventually matter: In the boom years, growth could paper over a lot. In the downturn, the math became unforgiving. UTI’s move from growth-at-all-costs to disciplined, outcomes-driven operations is a reminder that unit economics aren’t optional—they’re just patient. You can ignore them for a while, but you can’t ignore them forever.

For Investors

Stigmatized sectors offer opportunity: When UTI hit $1.42 a share in October 2016, the market wasn’t pricing a nuanced story. It was pricing an entire category as guilty. That’s where opportunity can hide: when sentiment becomes a blanket judgment, differentiated operators can get dragged down with the worst actors.

Look for structural tailwinds: The technician shortage isn’t a fad driven by a single business cycle. It’s demographics, complexity, and an economy that still runs on machines that need to be serviced. Companies positioned at the center of that kind of structural demand get a very different growth backdrop than companies trying to manufacture demand from scratch.

Management matters in turnarounds: UTI’s reversal wasn’t accidental. The leadership change and the operational overhaul were the story. In distressed situations, the question isn’t just “is the asset cheap?” It’s “does the team know how to rebuild the machine?”

Regulatory risk requires premium discount: For-profit education will always carry political and regulatory sensitivity. Even operators with better outcomes can get caught in a sector-wide crackdown. That risk deserves to live in the valuation—because it can return quickly, and it can be existential.

The Contrarian Take

Not all for-profit education is predatory. UTI’s record on graduate outcomes—completion, placement, and earnings—helped separate it from the worst offenders when the sector was under siege. As faith in the default four-year path weakens, trade education looks less like a backup plan and more like essential infrastructure. In that framing, schools like UTI aren’t exploiting the economy. They’re keeping it running.

XV. What's Next: UTI's Path Forward

With the turnaround working and the portfolio now spanning both skilled trades and healthcare, UTI’s next chapter is less about survival and more about controlled expansion. The company has said it expects, pending regulatory approval, to open at least two and up to five new campuses a year and to launch roughly 20 new programs annually across both divisions.

That plan sits inside what management calls its “North Star Strategy” Phase II: keep widening the map and keep widening the catalog. The near-term roadmap is straightforward—new campuses in underserved markets, new programs aimed at emerging skill shortages, and continued work to fully integrate acquisitions.

Concorde is the clearest proof point for why UTI thinks this can work outside transportation. Concorde operates 17 campuses across eight states and online, offering programs in allied health, dental, nursing, patient care, and diagnostic fields. And the labor-market backdrop is familiar: nursing shortages, like technician shortages, have been severe and persistent.

There’s also a longer-horizon question that hangs over the whole “future of mobility” narrative: AI and autonomy. Will autonomous vehicles eliminate technician jobs? Probably not anytime soon. If anything, increased complexity during the transition is likely to raise the bar for service and diagnostics, not remove the need. The real risk is further out—if autonomy ever reaches a steady-state where vehicles require significantly less human service. It’s not a near-term operational concern, but it’s the kind of slow-burn uncertainty investors should keep in view.

Finally, there’s the unclaimed territory: international expansion. For now, UTI remains entirely domestic, even as technician shortages show up worldwide. Regulatory complexity, cultural differences in vocational education, and the capital demands of campus-based training have kept global ambition limited. Still, it’s an obvious question for a company that’s built a repeatable model and now has the balance sheet to think bigger.

“Today’s company is stronger, more diverse and more resilient as a result of our successful North Star strategy,” said Mr. Grant. “We are realizing our fullest potential as an industry training partner, and I am confident our market position will continue to grow as we reach even more students in new geographies.”

XVI. Final Reflection: America's Skilled Trades Renaissance

UTI’s story is really America’s story: the long decline—and possible renaissance—of the skilled trades. For decades, the country steadily devalued work done with hands instead of keyboards. Guidance counselors steered capable students away from vocational paths. Shop class vanished from high school schedules. The unspoken message was simple: college meant success; trades meant settling.

Now the bill is due. The technician shortage has become one of the industry’s defining problems. Vehicles stay on the road longer, repair complexity keeps rising, and service departments can’t hire fast enough. In many markets, even routine work takes far longer than it should, not because the parts don’t exist, but because the people who know how to install them safely and correctly are in short supply. Turnover only compounds the issue—when experienced techs leave, there aren’t enough trained replacements behind them.

And yet, something is changing. For the second year in a row, more students have been pursuing automotive technician training. The cultural assumption that every student must take on a four-year degree—no matter the cost, no matter the fit—has started to crack. The trades are being reintroduced not as a fallback, but as a path: skill, paycheck, progression.

UTI stands to benefit from that shift. But the bigger point is that the country needs institutions like UTI to work. Transportation doesn’t move, healthcare doesn’t function, manufacturing doesn’t scale, and infrastructure doesn’t hold without trained technicians—and that workforce is exactly what America has been underbuilding for a generation.

Whether UTI captures the full opportunity will still come down to execution, competition, and the regulatory environment. But the opportunity itself isn’t going away. Fixing the skilled trades pipeline is structural work, and the demand for it will persist regardless of which organization gets the credit.

Sixty years after Robert Sweet welcomed 11 students into a small Phoenix building, UTI has become something he likely never could have mapped out: a publicly traded workforce education company training tens of thousands of students a year, partnered with major manufacturers, and positioned right at the intersection of labor shortages, electrification, and the rethinking of higher education.

The next sixty years will bring pressures Sweet never had to contend with—electrification, software-defined vehicles, automation, demographic shifts, and new forms of competition. But the last decade proved something important: UTI can take a hit that would have killed most companies in its category, and find its way back. It nearly died in 2016. It didn’t. And the things that helped it survive—outcomes tied to real jobs, relationships that actually matter, and a renewed operational discipline—are still the foundation today.

For investors, the real question isn’t whether UTI will face challenges. It will. The question is whether it has the resilience, relationships, and leadership to keep adapting fast enough. After six decades—and a near-extinction event—that answer looks more credible than it used to.

Top Resources for Further Reading

-

UTI's Annual Reports & 10-Ks (2003–present) – The most direct record of UTI’s evolution: strategy shifts, risk factors, enrollment dynamics, and management’s own commentary, available at investor.uti.edu

-

Senate HELP Committee Report: "For-Profit Higher Education: The Failure to Safeguard the Federal Investment and Ensure Student Success" (2012) – The document that captures the mood—and the mechanics—of the crackdown that nearly wiped out the sector

-

TechForce Foundation Technician Supply & Demand Reports – Clear, year-by-year tracking of the technician pipeline and where the shortfalls are compounding

-

Bureau of Labor Statistics: Automotive Service Technicians Outlook – The baseline government forecast for job openings and long-term demand

-

"The Case for Trade School" - The Atlantic – A readable look at why the culture is reconsidering the four-year default, and what’s pulling people back toward the trades

-

UTI Investor Presentations (2017-2025) – The turnaround narrative straight from the company: what changed, what they prioritized, and how they framed the rebuild

-

Chronicle of Higher Education Coverage – Reporting and analysis that places UTI inside the broader story of for-profit education, regulation, and student outcomes

-

"Shop Class as Soulcraft" by Matthew Crawford – A deeper, more philosophical argument for why skilled work matters—and why society lost the plot for a while

-

Automotive News Archives – Industry coverage of OEM relationships, dealer dynamics, and how technician hiring pressures have changed over time

-

Industry Trade Publications (Ratchet+Wrench, Motor Age) – The view from the shop floor: what employers are struggling with, what they’re paying for, and what skills they’re actually demanding

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music