Rent-A-Center/UPBD: From Furniture Rental to Fintech Phoenix

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

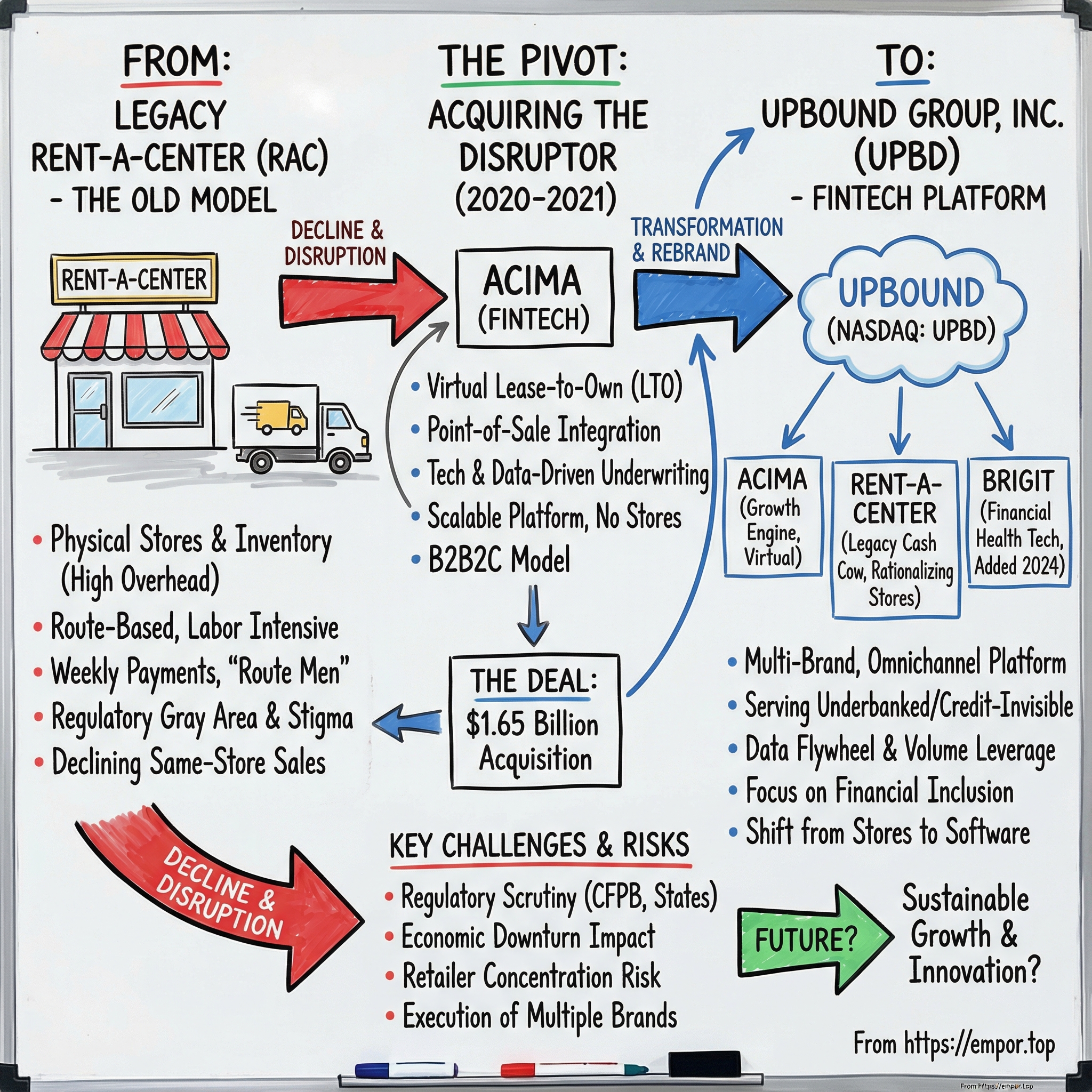

Picture this: it’s December 2020. A battered rent-to-own furniture chain—stores shrinking, reputation bruised, the whole model increasingly questioned—steps to the microphone and announces it’s buying a fast-growing fintech disruptor for $1.65 billion.

Investors didn’t quite know what to do with that. Was this a dying retailer making a desperate swing? Or was it the rare legacy company willing to admit the future wasn’t inside its own four walls?

Because on paper, the mismatch looked obvious. Rent-A-Center was built on storefronts, weekly payments, and a business living in a regulatory gray area. Acima was built to plug into other people’s checkouts, approve customers in minutes, and scale through software—basically everything the old model wasn’t.

Fast forward to today, and the company is Upbound Group, Inc. (NASDAQ: UPBD), positioning itself as a technology and data-driven provider of accessible, inclusive financial solutions. Its operating units include Acima®, Brigit™, and the original Rent-A-Center® brand, facilitating consumer transactions across more than 2,300 company-branded retail units in the United States, Mexico, and Puerto Rico. In full-year 2024, Upbound generated $4.3 billion in total revenue.

This is the story of one of the more unlikely transformations in modern American consumer finance: a company long criticized as a predatory relic trying to reinvent itself as a tech-enabled platform for financial inclusion. The core question is simple: how did a struggling rent-to-own furniture business transform into a lease-to-own fintech platform?

The answer sits at the intersection of inequality, regulation, and a counterintuitive survival strategy: if a disruptor is eating your lunch, sometimes the only move is to buy the disruptor. The market it serves isn’t small, either. The FDIC’s 2023 National Survey found 14.2 percent of U.S. households—about 19.0 million—were underbanked, and another 4.2 percent—about 5.6 million—were unbanked. That’s a massive, persistent population that traditional finance often doesn’t serve well, and it’s the customer base companies like Upbound have built around.

From its origins in Wichita, Kansas to its current life as a multi-brand platform straddling physical retail and digital finance, Upbound’s journey forces a bigger conversation: what does it really mean to “serve” credit-invisible Americans? Where is the line between access and exploitation? And when you wrap an old business model in modern software, do you get a reinvention—or just a faster version of the same thing?

II. The Rent-to-Own Industry Origins & Context

Before there was Rent-A-Center—before “fintech” was even a word—there was a very American problem hiding in plain sight: millions of working-class families couldn’t get traditional credit, but they still needed the basics. A fridge. A washer and dryer. A couch to sit on at the end of a long shift.

Rent-to-own, as the industry came to be known, traces back to J. Ernest Talley—widely regarded as the most influential early architect of the model. In the 1950s, Talley ran an appliance store with a cousin in Kansas. When banks tightened credit, customers who wanted his products simply couldn’t qualify. So Talley tried something different: he rented the items instead.

The logic was simple, and commercially brilliant. If the customer stopped paying, Talley could repossess the merchandise. If the customer kept paying long enough, the merchandise became theirs—and Talley not only moved more product, he earned more than he would have on a normal retail sale. In 1963, he formalized the approach with a rent-to-own chain called Mr. T’s, and by 1974 it had grown to 14 stores.

What Talley built wasn’t just a workaround. It was a clever reframing of risk. Traditional lenders needed a credit history and a legally enforceable debt. Rent-to-own didn’t. It was structured as a series of short-term rental agreements, renewed week to week or month to month. The customer could return the item without a long-term obligation and without a credit ding. The trade-off, of course, was cost: stick with it through the full term and you’d usually pay far more than the retail price.

That structure also landed the industry in a regulatory gray area that mattered as much as the business model itself. These agreements were often treated as rentals rather than credit, which helped them avoid Truth in Lending Act disclosure requirements. The industry’s habit of describing the same product as a “lease” in one context and a “financing option” in another wasn’t accidental—it was a way to live between rulebooks. Later, that ambiguity would become a lightning rod. Early on, it was rocket fuel.

Wichita shows up again here, because it’s also where the Rent-A-Center brand took shape. Thomas Devlin, a former employee of Mr. T’s, saw the demand for renting name-brand products and partnered with W. Frank Barton to found Rent-A-Center in 1973. Devlin had gotten an up-close view of the same friction Talley faced: customers with jobs and paychecks still getting turned away by traditional credit. His answer was the same basic promise, packaged into a scalable chain: take home what you need now, pay over time, own it eventually. Rent-A-Center grew through a mix of company-owned locations and franchisees.

So who was this for? Rent-to-own customers were—and still are—people the mainstream system doesn’t handle well: irregular income, thin credit files, past credit problems, or simply no history at all. That might mean recent immigrants, young adults starting from zero, or families rebuilding after a job loss or a medical bill. And the gaps aren’t evenly distributed. FDIC data shows unbanked rates, while down substantially since 2011, remain much higher for Black, Hispanic, and American Indian or Alaska Native households than for White households.

For the companies, the economics were appealing and punishing at the same time. Margins could be high because the total collected over a lease often dwarfed the wholesale cost of the goods. But the model was operationally intense: deliveries, repairs, swaps, repossessions, and collections—over and over—across thousands of low-dollar agreements. This was a route-based, relationship-heavy business. Your advantage wasn’t an algorithm. It was being local, being present, and being willing to knock on doors.

And from the beginning, rent-to-own carried a perception problem it never really escaped. Consumer advocates saw predation, pointing to implied annual percentage rates that could soar past 100% when compared to retail prices. The industry pushed back with a different framing: these were rentals, not loans, and customers were paying for flexibility and access when credit wasn’t available. That argument—access versus exploitation—never went away. It only got louder as the industry scaled.

III. Rent-A-Center's Rise: The Roll-Up Era (1986–2006)

By the mid-1980s, rent-to-own was no longer a quirky workaround. It was a full-blown retail category—one that could be scaled, copied, and consolidated. And Rent-A-Center’s rise in this era is a little like a business version of a shell game, because the name on the storefront and the company behind it kept changing.

One key figure was Mark E. Speese (born 1957). He entered the rent-to-own world in January 1978 working with the Rent-A-Center brand. After nearly eight years, he and two colleagues left to start a competitor: Vista Rent-To-Own. Speese wasn’t just “the founder” in title—he did the unglamorous work that makes chains actually work: picking locations, negotiating leases, hiring and training, writing the business model and employee handbook, creating advertising, and lining up vendors. Vista opened stores in New Jersey, Puerto Rico, and California.

At the same time, the original Rent-A-Center chain—founded by Thomas Devlin, not Speese—was changing hands. In 1987, Thorn EMI acquired that Rent-A-Center for $594 million. Thorn EMI was a British conglomerate with deep roots in the UK’s rental industry, and it saw the U.S. market as a big growth opportunity.

Meanwhile, Speese kept building. Vista pursued aggressive expansion, including a major move in December 1993 when it acquired an 84-store rent-to-own chain. After that deal, the company rebranded as Renters Choice, Inc.

Then came the capital markets. In 1995, Renters Choice went public on NASDAQ under the symbol RCII. And by 1998, it had grown into the industry’s second-largest player, with 750 stores.

The real plot twist hit that same year: Renters Choice acquired 1,409 Rent-A-Center stores from Thorn Americas, adopted the Rent-A-Center name, and consolidated operations in Plano. The upstart competitor didn’t just catch the incumbent—it bought the brand and the footprint.

The timing mattered. Thorn had separated from the EMI music business in 1996, and on its own it struggled—helped along by an uncomfortable truth for rent-to-own: a strong economy can be bad for the model. When more people qualify for traditional credit, fewer people need to rent a couch one week at a time.

In 2001, Speese became CEO and chairman of the board. He held the CEO role until 2014, and remained chairman after retiring as CEO.

With Speese in charge, Rent-A-Center leaned into the playbook that defined the era: roll-ups. The company kept buying competitors and store clusters, steadily turning a fragmented niche into something closer to a national chain business. In February 2003, Rent-A-Center acquired 295 stores from Rent-Way, Inc. In March 2004, it entered Canada with the acquisition of five stores in Edmonton and Calgary, Alberta. In May 2004, it completed acquisitions of Rainbow Rentals, Inc. and Rent Rite, Inc. And in November 2006, it completed the acquisition of Rent-Way for approximately $600.3 million. Rent-Way was then the number-three player, with 782 stores across 34 states. After that program, Rent-A-Center’s store count climbed to 3,535 locations.

The logic was classic consolidation: more scale meant more purchasing power with manufacturers, more leverage with landlords, and more ability to spread fixed costs across thousands of storefronts. By the mid-2000s, Rent-A-Center dominated the industry with roughly 35% market share by store count.

But the real engine of the business wasn’t the corporate office or even the stores. It was the operational machine in the field—what the industry called “route men.” These employees drove trucks to deliver merchandise, service it, and collect payments. They weren’t just logistics; they were the relationship layer. Payment rates and retention often depended on the trust they built with customers over repeated visits. It was intimate, labor-intensive, and hard to replicate without doing the work. And for a long time, it made Rent-A-Center’s scale feel like a moat.

And yet, even at the peak of the store empire, you can see the faint outline of the next chapter. In 2006, Rent-A-Center launched lease-to-own kiosks inside third-party retail locations under the brand name RAC Acceptance. In January 2014, those kiosks transitioned to the AcceptanceNOW brand. It was a small initiative inside a company still obsessed with its own four walls—but it was the first real signal that distribution might someday matter more than storefronts.

IV. The Decline: Death by a Thousand Cuts (2006–2016)

The decade after the Rent-Way deal was a grind. Rent-A-Center had finished consolidating the category—then the ground shifted under it. What had looked like scale started to look like exposure, and the company began taking hits from every direction at once.

First came the Great Recession. The 2008–2009 downturn landed hardest on the exact households rent-to-own depended on. As jobs vanished and budgets snapped tight, customers fell behind. Collections weakened, write-offs climbed, and same-store sales slid year after year.

And because the Rent-Way acquisition left Rent-A-Center with too many stores stacked on top of each other in certain markets, the “roll-up” era quickly turned into a clean-up era. Between 2007 and 2009, the company closed or merged 282 locations. What was supposed to be rationalization turned into retreat.

Then the scrutiny ramped. Regulation had always been the industry’s pressure point, and it got sharper in this period. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, created in 2010, began taking a harder look at rent-to-own. State attorneys general pursued cases alleging deceptive practices. Rent-A-Center had already felt that heat in California: in 2006, it settled for $7 million in restitution and $750,000 in civil penalties after the state claimed it violated state law by engaging in unfair competition and illegally misrepresenting the price of certain merchandise.

Inside the company, the leadership story started to mirror the business story: unsettled and reactive. Mark Speese retired as CEO at the end of January 2014. CFO Robert Davis took over from January 2014 to January 2017. Speese then returned as interim CEO until January 2018, when he stepped down again and former president Mitchell Fadel took the top job.

A revolving door at the top usually means the same thing: no one agrees on the plan. Should Rent-A-Center double down on the store base? Pivot hard into digital? Find a buyer? While executives debated, consumer expectations kept evolving. Amazon wasn’t doing lease-to-own, but it was retraining customers to expect lower prices and instant convenience—making the weekly-payment, drive-to-the-store experience feel more and more dated.

And then the new wave arrived. Fintech lenders and buy-now-pay-later players like Affirm and Afterpay started offering alternative ways to finance purchases, with sleeker tech and less stigma than rent-to-own. They were growing fast, backed by venture capital, and they didn’t need thousands of storefronts to reach customers.

The stock market saw the direction of travel. Years later, Rent-A-Center’s share price would reach an all-time end-of-day high of $65.50 on June 8, 2021. But in the late 2010s, it was the opposite story: the shares had fallen from pre-crisis highs above $30 into single digits. Activist investors moved in. And over everything hung the question that had once seemed unthinkable for the category leader: was rent-to-own simply dead?

V. The Pivot: Birth of Acima and the Virtual Lease-to-Own Model (2013–2019)

While Rent-A-Center was searching for a path out of its slow-motion decline, a very different kind of lease-to-own business was taking shape in Salt Lake City. And it wasn’t built around stores at all.

Acima was co-founded in 2013 by Aaron Allred, who served as its chief executive officer. The company operated under several brand names along the way, including Simple Finance. It began as “Simple Finance” in 2013, and in late 2016 it rebranded as Acima Credit—a name Allred selected.

The idea behind Acima was simple, and it changed the game: instead of paying for thousands of storefronts, fleets of trucks, and layers of field staff, put lease-to-own right at the checkout counter of retailers that already had the traffic. The customer applies and gets a fast answer. The retailer closes a sale that might otherwise walk out the door. And Acima runs the hard parts—technology, underwriting, and collections—behind the scenes.

Founded in 2013 in Salt Lake City, Acima positioned itself as a lease-to-own financial technology company with a national presence across retail partner locations and e-commerce platforms, spanning a wide range of product categories. Its platform included an underwriting and decision engine, expanding digital payments and communications, and back-end infrastructure designed to support both customers and its retail partners.

This B2B2C model—business to business to consumer—was a fundamental rewiring of rent-to-own. The traditional model was vertically integrated: the company owned the stores, stocked the inventory, and managed the customer relationship end to end. Acima worked like a layer. It partnered with retailers at scale, didn’t own the merchandise, and focused on making approvals fast and operationally manageable across thousands of points of sale.

The growth came quickly. Acima grew annual revenues from $97 million in 2016 to an expected $1.25 billion in 2020—an explosive run in just a few years. For comparison, Rent-A-Center’s revenue base was roughly $2.8 billion around that time, and it was flat to declining. In other words: Acima was becoming a business of real size, fast—exactly as the legacy business was losing momentum.

Acima’s edge was its technology. It built machine learning-based underwriting models that could approve or decline customers in seconds, using data beyond traditional credit scores. As it processed more applications and tracked outcomes, it accumulated proprietary performance data that improved decisioning over time. More retail partners produced more applications. More applications produced better data. Better data improved underwriting. Better underwriting helped win more partners. The flywheel started to spin.

And it wasn’t confined to the old rent-to-own categories. Acima expanded beyond furniture and appliances into tires and auto parts, mattresses, home improvement, and other durable goods—embedding itself into checkout flows where customers weren’t looking for “rent-to-own,” they were just looking for a way to buy.

The people building Acima also looked nothing like the traditional rent-to-own executive bench. Jason Hogg served as Executive Vice President at Acima and is the sole inventor of the Acima Ecosystem. Before that, he was CEO of Blackstone’s B2R Finance, Global CEO of Aon’s Cyber Solutions, and held executive roles at American Express and MBNA. He’s also known for founding the fintech platform Revolution Money—Steve Case’s first outside investment—which American Express acquired in 2010. Hogg stayed at Amex afterward, where he launched and ran the Amex Serve and Walmart Bluebird platforms.

Put it together and you can see why this mattered. Rent-A-Center had been trying to modernize a store-based machine. Acima was building a modern platform from day one. This wasn’t a furniture rental company that happened to use software. It was a technology company that happened to facilitate merchandise financing.

VI. The Transformational Deal: Rent-A-Center Acquires Acima (2020–2021)

By early 2018, Rent-A-Center had cycled through leaders and strategies, and it brought back a familiar operator to steady the wheel: Mitch Fadel.

Fadel wasn’t an outsider with a slide deck. He’d joined Rent-A-Center in 1983 through a store management training program, moved up fast, and spent the next three decades inside the machine. He’d run districts, led regions, and eventually held senior roles including President and Chief Operating Officer. From 1992 to 2000, he served as President and CEO of a Rent-A-Center subsidiary—Rent-A-Center Franchising International, Inc., formerly known as ColorTyme, Inc.—a major franchise business in the rent-to-own world. He also served as a director for more than a decade.

In other words: Fadel knew stores. He knew the route-man model. He knew what it took to run a tight operation when the “customer experience” included delivery trucks, service calls, and collections.

But by the time he returned as CEO, he also knew something else: the future couldn’t be a rerun of the past.

That realization showed up first in a smaller, strategic move. In August 2019, Rent-A-Center acquired Merchants Preferred, a nationwide provider of virtual lease-to-own services. The goal wasn’t just to buy revenue—it was to build muscle. After the acquisition, Rent-A-Center rolled out Preferred Lease, an integrated retail partner offering that combined AcceptanceNOW’s staffed, in-store lease-to-own model with Merchants Preferred’s virtual approach.

Call it the warm-up act. Because Acima was the headliner.

On December 20, 2020—right in the middle of COVID-era disruption—Rent-A-Center announced it would acquire Acima Holdings for $1.65 billion. The deal included $1.273 billion in cash and about 10.8 million shares of Rent-A-Center stock, valued at roughly $377 million at the time.

To finance it, Rent-A-Center lined up $1.825 billion in debt financing from J.P. Morgan Securities LLC, HSBC Securities (USA) Inc, and Credit Suisse. The company said it expected the transaction to close in the first half of 2021 and pitched the move as a leap toward becoming a “premier fintech platform” across both traditional and virtual lease-to-own.

Then it happened fast. On February 17, 2021, Rent-A-Center announced it had completed the acquisition.

The pitch for the combined company was straightforward: pair Acima’s virtual decisioning and retail-partner reach with Rent-A-Center’s platform and footprint—what the company described as combining Acima with its Preferred Dynamix platform—so retailers and consumers could access “frictionless” lease-to-own across e-commerce, digital, and mobile channels.

“We're thrilled to be part of a Rent-A-Center team that's modernizing LTO to serve the estimated over 60 million unbanked and underbanked consumers in the United States,” said Aaron Allred.

Strategically, you can see why the bet made sense. Rent-A-Center brought scale, capital, regulatory relationships across all 50 states, and a legacy business that still generated cash. Acima brought the thing Rent-A-Center couldn’t seem to build on its own: modern underwriting, real technology leverage, and a retailer network that could expand without adding stores.

Together, the vision was an omnichannel lease-to-own platform: physical when needed, virtual when preferred.

But the skepticism was just as real. Rent-A-Center was a Plano, Texas-based retailer with deep roots in the old rent-to-own playbook. Acima was a Salt Lake City tech company built for speed and partnerships. Their models were almost mirror images.

Fadel’s wager was that those differences weren’t fatal—they were the point. The market had been punishing Rent-A-Center for what it lacked. Buying Acima was the fastest way to change the story.

VII. The Transformation Unfolds (2021–Present)

By 2023, the company decided it couldn’t keep telling a “Rent-A-Center” story when the business was becoming something else.

On February 23, 2023, Rent-A-Center, Inc.—the parent of Rent-A-Center®, Acima®, and other consumer brands—announced a new name: Upbound Group, Inc. An omni-channel platform company, it said, built to help a broader range of consumers access flexible financial solutions. A few days later, on February 27, 2023, the company began trading under a new ticker: NASDAQ: UPBD.

“Two years ago, Rent-A-Center, Inc. closed on its acquisition of Acima Holdings, almost doubling the size of the company and dramatically changing both organizations,” CEO Mitch Fadel said. “We are now a unified, multi-brand platform company that includes more than just the Rent-A-Center business. We are thrilled to launch Upbound, a new enterprise brand and operating structure that will better serve our business and mission.”

The rebrand didn’t create the shift—it acknowledged it. Acima was now the growth engine. The legacy Rent-A-Center stores were increasingly the cash-generating base that helped fund what was working.

You can see it in the latest performance snapshot. In the fourth quarter of 2024, Acima’s revenue grew 14.4% year-over-year, and full-year revenue grew more than 17% to about $2.3 billion. Over the same period, Rent-A-Center revenue fell by roughly $15 million year-over-year, driven by store franchising and consolidation. Same-store sales were relatively flat in the fourth quarter, and Rent-A-Center ended the year with 111 fewer locations than at the end of 2023.

That store rationalization has been the quiet drumbeat behind the transformation. From a peak of more than 3,500 stores in the mid-2000s, the company now operates roughly 2,300 locations—and the trajectory has continued downward through franchising, consolidation, and selective closures. The economics are hard to argue with: virtual lease-to-own doesn’t come with real estate, inventory sitting on shelves, or fleets of trucks.

Then came the next evolution—one that pushed Upbound beyond merchandise financing entirely.

On December 12, 2024, Upbound announced it had entered into a definitive agreement to acquire Brigit, a financial health technology company, for total consideration of up to $460 million in cash and shares of Upbound common stock.

Brigit launched nationally in 2019 with a mission tied closely to financial inclusion. Built on proprietary artificial intelligence and machine learning-powered cash flow insights, its core product is a direct-to-consumer Instant Cash advance product. Upbound said Brigit had saved users $1 billion in overdraft fees since inception, and positioned the deal as a way to expand a technology-driven suite of solutions for underserved consumers.

The acquisition closed on January 31, 2025. After the close, the combined company said it was serving approximately four million active customers, including Brigit’s more than one million active paying subscribers and almost one million free subscribers.

Strategically, it’s a clear statement of intent. Upbound is betting that what it’s learned serving credit-constrained customers can travel—away from couches and refrigerators, and into financial wellness products like earned wage access, credit building, and budgeting tools, delivered through a subscription model rather than a merchandise lease.

VIII. The Controversy & Regulatory Landscape

The ethical debate around rent-to-own and lease-to-own has never really been settled. If anything, the closer these products get to “mainstream fintech,” the louder the question gets: is this access—or is it exploitation dressed up as flexibility?

That debate became very real on July 26, 2024, when the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau filed suit against Acima Holdings, LLC, Acima Digital, LLC, and Acima’s founder and former CEO, Aaron Allred. The CFPB framed Acima as a point-of-sale “lease-to-own” provider—online and in-store—that was, in practice, pulling consumers into expensive obligations they didn’t fully understand.

The CFPB’s allegations went straight at the heart of the industry’s long-running gray area. It claimed Acima’s agreements could leave many customers paying more than 200% of a product’s retail price. It also alleged Acima marketed its product as “credit” in some contexts, while calling it a “lease” in others—misleading consumers about what they were signing up for and, the CFPB argued, attempting to sidestep consumer protection rules that apply differently to leasing products versus credit products.

The legal list was long and serious: alleged violations of the Consumer Financial Protection Act, the Truth in Lending Act, the Fair Credit Reporting Act, and the Electronic Fund Transfer Act. The CFPB also tied its claims to the sheer scale of the business, alleging issues connected to as many as five million financing agreements entered into since 2015.

Acima didn’t respond with a quiet settlement or a carefully worded apology. It went on offense. Acima filed its own lawsuit against the CFPB in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, seeking to stop what it described as an illegal attempt by the Bureau to expand its authority and override the state-by-state regulatory framework that has governed lease-to-own for decades.

Then, in March 2025, the CFPB voluntarily dismissed its case with prejudice, after the agency and Acima had fully briefed a motion to dismiss. Dismissal with prejudice matters: the CFPB can’t simply bring the same claims again. Upbound CEO Mitchell Fadel responded with a victory-lap tone, saying, “We welcome and appreciate the CFPB's recognition that it was appropriate to dismiss its lawsuit and finally bring this longstanding matter to an end.”

Context matters here, too. The dismissal fit a broader pattern: it was the latest in a series of enforcement actions brought under former CFPB Director Rohit Chopra that the agency later dropped. For Upbound, the timing—amid a change in administration—couldn’t have been better.

But “better” doesn’t mean “safe.” Regulatory risk still hangs over the category. State attorneys general remain active, and state rules are still the day-to-day reality of compliance. In November 2023, for example, Rent-A-Center paid Massachusetts $8.75 million to settle claims of unfair and deceptive business practices, and agreed to stop filing criminal complaints against customers for missed payments.

So the core tension is still there, unchanged. Lease-to-own can look like a lifeline: a customer gets a refrigerator or a bed when traditional credit is closed to them. It can also look like a trap: a family ends up paying far more than retail for something they needed yesterday. Which story feels “true” often depends on which customer you’re talking about—and what, exactly, they were told at the point of sale.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

To understand Upbound, you have to hold two very different machines in your head at the same time—because it’s operating both.

The Legacy Rent-A-Center Store Model is the classic rent-to-own playbook. The company buys furniture, appliances, and electronics, then rents them out on weekly or monthly agreements. Customers usually have a few paths: keep paying until they own it, use an early purchase option for less than the full term, or return the item without penalty. The trade-off for that flexibility is price. Over a full term—often around a year to a year and a half—total payments can land at two to three times the retail price.

That flexibility isn’t free for the company, either. This model is capital-intensive and operationally heavy. Rent-A-Center has to fund inventory up front, carry the cost of real estate, staff the stores, run delivery vehicles, and maintain a collections operation that never stops. Gross margins can look great on paper—often 60% or higher—but the overhead required to run the system eats a lot of it. The stores can still throw off meaningful cash, but growth gets harder when foot traffic keeps sliding.

The Acima Virtual Model flips the structure. Acima doesn’t run stores and it doesn’t stock shelves. Instead, it sits inside a partner retailer’s checkout flow. A customer applies at the point of sale, Acima underwrites them instantly, and if approved, Acima buys the merchandise from the retailer. The retailer gets paid immediately, and Acima collects the lease payments from the customer over time.

The cost structure changes with the model. Acima doesn’t have to carry store leases or fleets of trucks. Its main capital requirement is funding the lease portfolio—the merchandise it purchases for active leases. The technology platform is largely fixed cost, which means it gets more powerful as volume grows: more transactions, more data, more efficiency.

That’s the logic behind newer initiatives like the Acima marketplace. It grew by 60% in Q4 2024, though from a small base. Today it’s still only a low single-digit percentage of GMV, with expectations to reach mid-single digits in 2025 and potentially move into double digits over time.

In both models, one feature matters more than almost anything else: the 90-day early purchase option. It’s the pressure-release valve. It gives customers a way to get to ownership early at a modest premium, instead of riding the lease all the way to the expensive end of the curve. That makes it central not just to customer experience, but to regulation and public perception too—because it’s the cleanest answer to the criticism that lease-to-own is only “fair” if you can’t escape the full-term price.

The unit economics, in the end, come down to behavior. Customers who pay to term generate the most revenue, but they’re also the ones paying the highest effective rates. Customers who pay early produce lower margins, but also lower regulatory risk. Defaults are the third outcome—and those losses have to be absorbed by the portfolio.

Looking ahead to 2025, Upbound expected gross profit to be relatively flat year-over-year, with the improvement story coming from better loss rates and operating leverage. The emphasis is straightforward: keep underwriting disciplined, keep scaling the platform, and let efficiency do the work.

That’s the real edge in the Acima model: volume leverage. Once the retailer integration is done and the underwriting engine is built, each incremental transaction requires very little additional investment. The platform doesn’t need a new store to grow—it just needs more checkouts to run through. And as those transactions stack up, the fixed costs get spread thinner, and the returns on capital get better.

X. Strategic Positioning & Competitive Landscape

To understand where Upbound fits, start with the size of the prize. The U.S. rent-to-own market was estimated at about $12 billion in 2023, and multiple forecasts expect it to grow meaningfully over the rest of the decade. The exact projections vary depending on the analysis, but the direction is consistent: this isn’t a niche that’s quietly disappearing. It’s a category with real demand, driven by the same structural reality that created rent-to-own in the first place—millions of consumers who still can’t access traditional credit on reasonable terms.

Within that market, Upbound gets squeezed from several angles at once.

The most direct head-to-head competitor is Progressive Leasing (PROG Holdings, NYSE: PRG). PROG completed its spin-off from Aaron’s on December 1, 2020 and began regular-way trading on the New York Stock Exchange under “PRG.” Progressive isn’t competing on some adjacent product. It’s competing on the same core idea Acima is built on: point-of-sale, virtual lease-to-own at scale. PROG describes itself this way: “Since pioneering virtual lease-to-own in 1999, we have continued to be the leading point-of-sale lease-to-own solution in the United States.”

And they’re big. PROG offers lease-purchase solutions through more than 30,000 retail partner locations across 46 states, plus the District of Columbia, including e-commerce merchants. That makes it a true peer competitor—similar model, similar distribution strategy, and comparable scale.

Then there’s Aaron’s Company (NYSE: AAN), the other side of that split. Aaron’s competes primarily with the legacy Rent-A-Center store business. It operates traditional rent-to-own stores and has pushed a hybrid strategy that combines roughly 1,050 physical locations with a growing digital commerce presence. The pitch is intuitive: a showroom still matters for certain customers, especially in a category where trust and immediacy can beat slick UX. Purely digital rivals don’t get that advantage.

Upbound also has to keep an eye on the broader consumer finance wave. Buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) companies like Affirm and Klarna compete for the same retail spend, even if they usually play a bit higher up the credit spectrum. BNPL’s growth has been rapid, but the category tends to struggle with truly subprime customers—exactly where lease-to-own has historically lived.

Upbound’s CFO Fahmi Karam has framed it less as a knife fight and more as a sequencing effect. “We view the BNPL space as complementary to us,” he said. “We don't necessarily compete with them today. As we expand with Upbound into potentially other financial products, we'll start seeing a little bit more competitive nature with that industry… the next natural step is to have lease-to-own.”

But the biggest strategic risk isn’t another lease-to-own player. It’s the partner. If a major retailer decided to build lease-to-own financing in-house, Upbound could lose distribution overnight. The competitive landscape includes names like Upbound Group, Aaron’s Company, and FlexShopper Inc., but the power sits with whoever controls the checkout. If Walmart or another major retail partner internalized the product, it could materially shrink Acima’s addressable market.

That’s why Upbound’s advantages matter. It brings scale across both physical and virtual channels, proprietary underwriting data built from millions of transactions, established retailer relationships, and regulatory licenses across all 50 states—friction that makes it harder for smaller entrants to copy the model quickly, and harder for even large players to replicate without serious investment.

XI. Competitive Analysis Framework

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High. The software itself isn’t magic. With enough capital, a new player can build underwriting, payments, and a decent checkout flow. The real friction shows up everywhere else: navigating a state-by-state regulatory patchwork, winning retailer trust, and funding a lease portfolio at scale. New entrants can appear, but breaking in meaningfully is a longer, heavier lift than it looks.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low. The underlying products—furniture, appliances, electronics—are widely available, so manufacturers don’t have much leverage. And on the funding side, capital providers compete to finance lease portfolios, which gives companies like Upbound options.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Medium. For consumers, switching isn’t really a thing once you’re in an active lease. And for many credit-constrained customers, alternatives are limited. Retailers are the tougher counterpart: they can shop providers, negotiate economics, and push on take rates. If a giant retailer like Walmart wanted to dictate terms—or build a solution in-house—that power is real.

Threat of Substitutes: High. Credit cards, subprime lenders, and BNPL players that keep expanding down-credit all compete for the same transaction. Even cash is a substitute, at least in theory. And for the most financially stressed consumers, payday and title lenders are still in the mix—different product, same customer pressure.

Competitive Rivalry: High. This is a knife fight. Progressive Leasing is a direct rival with a similar model and scale. Retailer take-rate competition keeps tightening. And the race is now fought in underwriting quality, fraud detection, mobile experience, and speed at checkout. The prize is the best retail partners—and everyone knows it.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework:

Scale Economies: Strong (★★★★☆). Acima gets leverage from being big. The platform has meaningful fixed costs, and every incremental transaction spreads those costs thinner. Scale also helps on funding: a larger lease portfolio can translate into better capital terms. Even retailer acquisition gets cheaper over time as relationships and integrations compound.

Network Effects: Moderate (★★★☆☆). The flywheel is real, just not as explosive as a pure marketplace. More retailers create more applications and more outcomes data. That data improves underwriting. Better underwriting makes the product more attractive to retailers. Repeat usage adds another layer of benefit, but it’s not a “winner-take-all” dynamic.

Counter-Positioning: Strong (★★★★☆). Banks generally can’t—or won’t—serve this segment in a profitable way given constraints and incentives. Many BNPL players struggle as you move into lower credit tiers. And the most interesting twist is internal: the legacy store model can’t compete economically with Acima’s virtual model, but Upbound owns both. That lets it optimize the portfolio instead of getting disrupted from the outside.

Switching Costs: Weak (★★☆☆☆). Retailers face some friction in switching—integrations, training, process changes—but it’s not prohibitive. Consumers can also move between providers over time. There’s some stickiness from repeat behavior, but not true lock-in.

Branding: Weak (★★☆☆☆). In a B2B2C model, the retailer’s brand is what the customer sees and trusts. Acima is often invisible. Upbound’s rebrand helps at the corporate level, especially in distancing from the Rent-A-Center stigma, but consumer brand power isn’t the core advantage here.

Cornered Resource: Moderate (★★★☆☆). Upbound’s biggest “resource” is informational: proprietary performance data from millions of lease transactions. That improves decisioning in ways a new entrant can’t shortcut quickly. Add in established retailer relationships—sometimes with exclusivity—and the reality that operating across all 50 states requires regulatory infrastructure that isn’t trivial to replicate.

Process Power: Strong (★★★★☆). This is where years of repetition matter. Underwriting that actually works at scale, collections that don’t implode, fraud systems that keep up, and the operational wiring to run across physical and virtual channels—those are accumulated capabilities, and they’re hard to copy fast.

Overall Assessment: Upbound’s position is defensible because several powers stack together: Scale Economies, Process Power, and Counter-Positioning do the most work. But no single advantage is overwhelming, which means the moat is real—just not permanent.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

Acima’s growth runway still looks long. Today it operates across more than 15,000 active retail partner locations and e-commerce platforms. If you believe the distribution footprint can expand to 50,000 or even 100,000+ locations over time, then the story isn’t about squeezing a mature business—it’s about a platform that’s still early in penetration across categories.

The customer base isn’t going away. Nearly 20 million U.S. households are underbanked, using nonbank products to cover basic financial needs. That’s not a fad; it’s a structural feature of the economy. Income volatility, credit score scarring, and immigration dynamics keep replenishing the pool of people who need alternatives to traditional credit.

The data flywheel compounds. Every application and payment adds to Acima’s underwriting and loss-performance dataset. Over time, that can create a reinforcing loop: better decisioning drives better approvals and better outcomes, which produces more data, which improves decisioning again. In that world, scale isn’t just size—it’s underwriting advantage, and competitors without similar volume can end up with structurally worse loss rates.

The “old” business funds the “new” one. Bulls don’t see the shrinking Rent-A-Center store base as dead weight; they see it as a cash generator that can bankroll investment in Acima and support share buybacks. And the existing footprint still comes with real optionality—customer relationships, local presence, and tangible assets that can soften the downside.

Regulatory clarity could actually help. Lease-to-own has lived in ambiguity for decades. If states or the federal government set clearer rules of the road, it could legitimize the category and raise barriers to entry—turning compliance from a threat into a moat.

"Acima's momentum continued, as it delivered over 17% growth this year on both GMV and revenue, while generating its largest-ever adjusted EBITDA."

The Bear Case:

Regulation is still the big overhang. Yes, the CFPB lawsuit was dismissed, but that doesn’t eliminate the underlying uncertainty. A different administration, a different theory of the case, or a different regulator could push to treat lease-to-own more like credit—pulling it deeper into Truth in Lending-style requirements and potentially changing the economics.

This customer gets hit first in a downturn. As CFO Fahmi Karam put it, "Inflation has hit our customers extremely hard," and Upbound’s core customers are often the ones without access to traditional loans or credit cards. In a recession, they’re typically first to lose hours or jobs, and last to recover—exactly the wrong macro sensitivity for a business built on consistent payment performance.

Retailer concentration is real risk. Walmart is the name everyone points to, but the broader point matters more: whoever controls the checkout controls the distribution. If major retailers decide they’d rather own lease-to-own economics than share them, they could try to build it themselves—and the market available to Acima could shrink quickly.

Reputation can cap the multiple. A meaningful slice of institutional capital won’t touch rent-to-own or lease-to-own on ESG grounds, viewing the model as inherently exploitative. Even if the business performs, that structural buyer reluctance can keep valuation constrained.

Tech advantage may be less durable than it looks. Progressive Leasing is a capable, scaled competitor. And underwriting improvements aren’t protected like patents; they can be matched, copied, and iterated on. Over time, differentiation can compress into pricing pressure with retailers.

And finally: the legacy operation can still pull focus. Running a declining physical retail fleet takes time, talent, and capital. If management attention gets split for too long, the “cash cow” can start to look more like a drag on the very platform it’s supposed to fund.

XIII. Key Metrics to Track

If you want to know whether Upbound is truly becoming a platform company—and not just telling a better story—three metrics will usually give you the clearest signal.

1. Acima GMV Growth Rate. Gross merchandise value flowing through Acima is the cleanest read on the health of the growth engine. It reflects both how many retail partners Acima is winning and how much volume it’s driving inside the partners it already has. If GMV is rising, the platform is expanding its reach at the checkout. If it’s not, the transformation stalls.

2. Blended Lease Portfolio Loss Rates. This is the reality check. Loss rates compress underwriting quality, macro conditions, and collections performance into a single number. If losses climb, either the customer is under stress or the approval box is getting too loose. If losses fall, it suggests the machine is getting smarter, tougher, or both. The whole bet is that Upbound can grow without paying for it later in charge-offs.

3. Segment Profit Margins (Acima vs. Legacy RAC). Ultimately, the shift only matters if it improves returns. That means Acima’s margins have to hold up or expand as it scales, while the legacy Rent-A-Center stores stay profitable even as the footprint shrinks. Watching the mix shift and margin direction in each segment is how you tell whether the platform is actually creating value—or just replacing one kind of revenue with another.

XIV. The Road Ahead

The big question hanging over everything is whether Acima can graduate from “fast-growing platform” to “scaled cash machine.” Can it get to $2 billion or more in revenue while sustaining EBITDA margins north of 20%? Management commentary and the current trajectory suggest it’s within reach over the next couple of years, but it won’t happen automatically. It depends on three things that sound simple and are hard in practice: adding more retailer partners, driving more volume inside the partners it already has, and keeping underwriting tight enough that growth doesn’t turn into tomorrow’s losses.

Then there’s the question Upbound can’t quite answer out loud yet: what’s the endgame for the Rent-A-Center store fleet? Management hasn’t put a number on it, but the vector is obvious—more franchising, more consolidation, fewer company-operated stores. Whether that stabilizes around 1,500 locations, shrinks to 1,000, or eventually winds down far further is still uncertain. What isn’t uncertain is the direction.

Brigit is the clearest signal that Upbound wants to become something bigger than lease-to-own. Upbound expects that within the next four years, about two-thirds of revenue and Adjusted EBITDA will come from its virtual and digital platforms. That’s not a tweak to the model. It’s a reshaping of the company’s center of gravity—toward a technology platform that still happens to operate some physical retail along the way.

Brigit also widens the product canvas. Earned wage access, credit-building tools, budgeting and financial wellness—these are adjacent needs for the same customer base Upbound already serves. If executed well, they could deepen relationships and improve lifetime value. The catch is execution risk: running one platform business is hard; running multiple product lines well, without diluting focus, is harder.

International expansion is another wildcard. Upbound’s Mexico segment operates around 130 stores today, and the broader logic is tempting: large underbanked populations, real demand for access products, and less saturated competitive landscapes in some markets. But global growth comes with real complexity—regulation, fraud dynamics, underwriting calibration, and operational differences that don’t copy-and-paste from the U.S.

And finally, the returns story will be shaped by capital allocation. Upbound has choices: reinvest more aggressively into Acima, pursue more acquisitions, buy back shares, or pay down debt from the dealmaking era. Those trade-offs will matter as much as the growth itself—because in a business like this, how you deploy cash is often the difference between a good transformation and a great one.

XV. Lessons for Founders & Investors

Upbound’s arc—stores to software, “rent-to-own” stigma to fintech ambition—lands a few lessons that travel well beyond this one company.

Legacy businesses can acquire their way to relevance. The standard script says incumbents don’t buy disruptors; disruptors bury incumbents. Rent-A-Center’s acquisition of Acima broke that script. The move worked because management got clear-eyed about what the legacy business still had that mattered—capital, regulatory infrastructure, and deep knowledge of this customer—and what it didn’t: a modern growth model, modern technology, and the talent to run both.

Serving the underbanked is hard but durable. Financial exclusion in America has proven stubborn. That’s the opportunity and the trap. If you can serve credit-invisible consumers in a way that’s both profitable and resilient, you have a market with real staying power. But you also inherit the challenges that keep most mainstream institutions away: messy data, volatile customer economics, and nonstop regulatory attention.

Platform models beat owned-inventory models. Acima made a simple point with big implications: plugging into someone else’s checkout scales better than building your own storefront empire. Intermediating a transaction—if you can underwrite and collect—tends to be more capital-efficient than owning inventory, leasing real estate, and running trucks. Upbound’s entire transformation is basically a case study in that shift.

Regulatory risk is real but can create moats. This category lives under a permanent cloud of “what if the rules change?” That uncertainty scares off casual entrants and forces anyone serious to build real compliance capabilities. The irony is that the same scrutiny that threatens the business can also protect it—because navigating fifty different sets of state rules is not a weekend project.

Cultural transformation is the hardest part of M&A. A Salt Lake City fintech doesn’t naturally fuse with a Plano retail operator. Keeping Acima’s leadership and continuing to run it from Salt Lake City signaled that Upbound understood what it was buying. If you smother the culture that created the growth, you don’t “integrate” the asset—you dissolve it.

Markets misunderstand transition stories. For long stretches, Upbound traded at low multiples even while its highest-value segment was growing quickly. That’s common in transformations: investors can anchor on what a company was, not what it’s becoming. When the mix shift is real—and sustainable—patient capital often gets paid as perception catches up to the new business.

XVI. Epilogue: Escaping the Gravity of Legacy

The transformation from Rent-A-Center to Upbound Group still isn’t finished. As of late 2025, the company continues to run a meaningful legacy store base, continues to operate under a regulatory cloud that can shift with politics and enforcement priorities, and still has to prove that Acima can keep growing without letting losses creep up as the economy tests its customers. And with Brigit now in the mix, Upbound added yet another integration challenge—and another big bet that it can expand beyond “financing a purchase” into “managing a financial life.”

Still, it’s hard not to be struck by how far the company has already moved. In the late 2010s, Rent-A-Center looked like a business in slow retreat: too many stores, too much stigma, and too little growth. Today, Upbound is telling a different story—one built around software, underwriting, and distribution through other people’s checkouts, aimed at the same customers mainstream finance still underserves. Even the market’s framing changed along the way, from a declining retailer trading like a problem to solve to a platform business with a new kind of upside.

Zoom out, and the arc says as much about America as it does about one company. Economic inequality didn’t create rent-to-own, but it made it durable. Traditional finance didn’t intend to exclude tens of millions of households, but its incentives and rules often do. And every time a new “inclusive” product shows up, the same tension returns: are we building a bridge for people who’ve been left out, or are we simply monetizing the fact that they don’t have better options?

So the question that hangs over Upbound isn’t just whether the strategy was clever. It’s whether it’s truly transformative. Did the company escape the gravity of legacy rent-to-own—or is it still tethered to that past in ways that will eventually snap back into view?

The next few years will answer that, not the press releases. Acima’s growth trajectory, Brigit’s integration, the direction of regulation, and the strength of the consumer economy will decide whether this is a lasting reinvention or a well-executed detour.

What’s already clear is the audacity of the move: a struggling furniture rental company betting its future on buying its fintech disruptor—and, at least so far, making it work. Whether it keeps working is the essential question.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music