UnitedHealth Group: The Healthcare Colossus

I. Introduction

In the winter of 2024, a gunman approached the CEO of UnitedHealthcare outside a midtown Manhattan hotel and fired three shots. The CEO, Brian Thompson, died on the sidewalk. In the days that followed, something even stranger unfolded: the alleged killer was turned into a kind of folk hero online—his face screen-printed on T-shirts, his supposed manifesto picked apart by millions. The shell casings left at the scene carried three words: “delay,” “deny,” “depose.” Whatever the legal outcome, the cultural verdict landed fast. America’s largest health insurer had become a lightning rod for the country’s fury over healthcare.

That’s the backdrop for understanding the scale of the company at the center of this story. In 2024, UnitedHealth Group reported about four hundred billion dollars in revenue—making it the seventh-largest company in the world by revenue and the unquestioned heavyweight of American healthcare. It employs or contracts with roughly ninety thousand physicians. It processes claims for around a third of American patients. It runs one of the largest pharmacy benefit managers, one of the biggest health data and analytics platforms, and an insurance business that covers more than fifty million people. No company in U.S. history has sat across so many parts of the healthcare table at once.

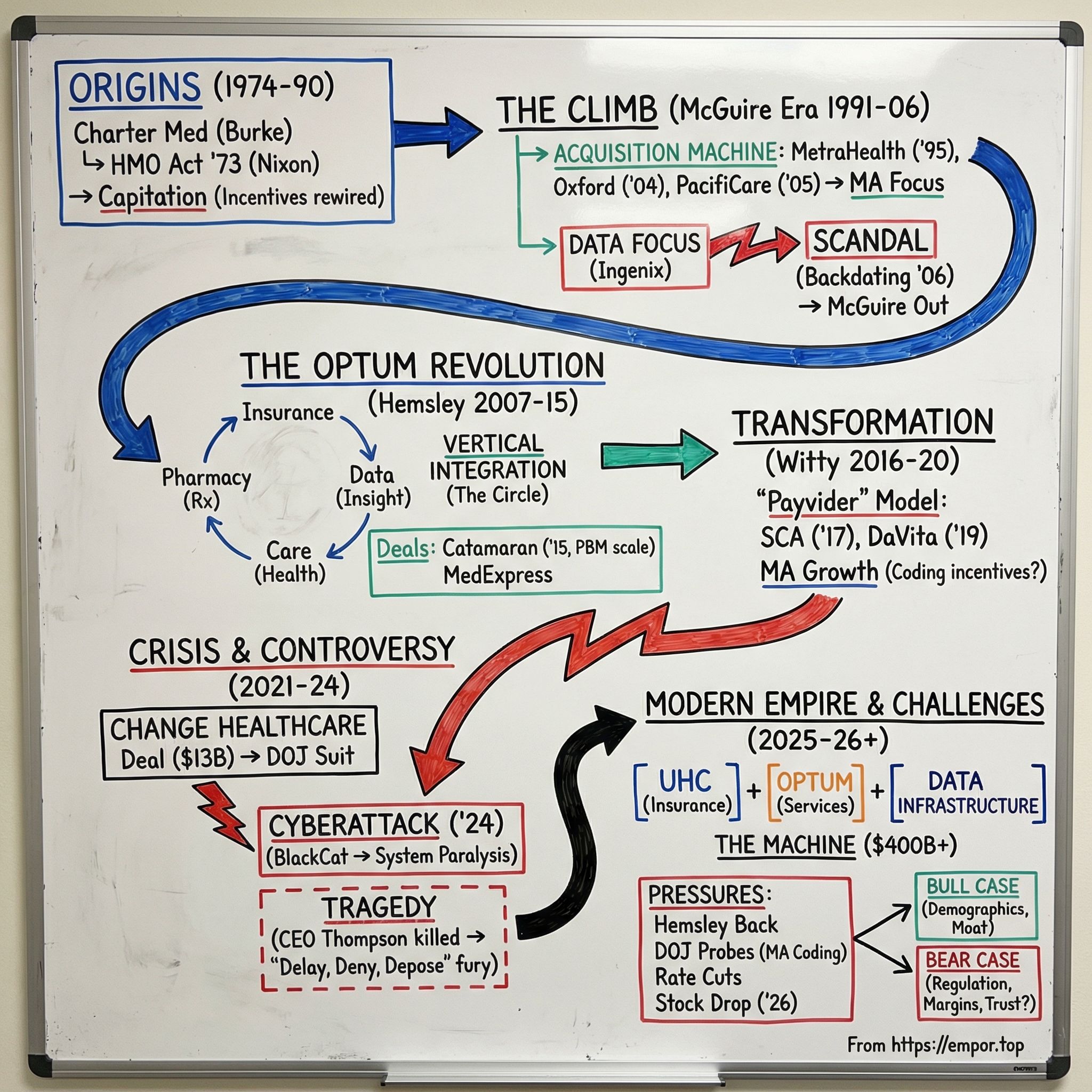

So how did a regional health maintenance organization in Minneapolis grow into this?

The answer is five decades of aggressive expansion and steady consolidation: acquisitions stacked on acquisitions; a deliberate, controversial bet on vertical integration; scandals that would have broken smaller companies; and a regulatory environment that, until recently, mostly let the machine keep running. This is the story of how a scrappy HMO became a half-trillion-dollar empire, why it now faces existential questions about its future, and what it means when one company plays insurer, pharmacy middleman, data broker, and care provider—often in the same transaction.

It begins, like so many American business stories do, with an entrepreneur, a tax incentive, and an idea whose moment had arrived.

II. Origins: The Charter Med Beginning (1974–1990)

In 1974, a young entrepreneur named Richard Burke sat in a small office in Minnetonka, Minnesota, looking at the same math that was starting to terrify Corporate America. Healthcare costs were climbing fast. Employers who offered health insurance watched premiums rise every year, with almost no lever to pull to slow it down. And the engine driving it all was fee-for-service medicine: the more tests, procedures, and visits a provider did, the more they got paid. The system didn’t reward keeping people healthy. It rewarded doing more.

Burke’s answer was Charter Med Incorporated—a company built to organize networks of doctors and hospitals into what were then becoming known as health maintenance organizations. The idea wasn’t brand new. Kaiser Permanente had proven versions of prepaid, integrated care decades earlier on the West Coast. But the timing had changed. The HMO Act of 1973, signed by President Nixon, had just given managed care a federal tailwind by requiring many employers to offer an HMO option alongside traditional insurance. Almost overnight, a real market appeared—one with policy support and a clear customer: employers desperate for cost containment.

Minnesota was the right place to start. The state had deep roots in nonprofit healthcare, cooperative institutions, and a regulatory environment more open to experimentation than most. It also had the employer base: headquarters like 3M, General Mills, and Honeywell—big workforces, big benefit budgets, and real incentive to try something new. Add the Mayo Clinic down in Rochester, and the state carried a kind of built-in medical legitimacy.

Burke recruited physicians willing to operate under capitation: a fixed monthly payment per enrolled patient, no matter how many services that patient used. That single change rewired the incentives. Instead of getting paid more for doing more, providers took on financial risk—and suddenly had a reason to focus on prevention, coordination, and avoiding unnecessary care. It wasn’t just a different payment model. It demanded a different way of practicing medicine.

In 1977, Burke renamed the company United HealthCare Corporation, a subtle signal that this wasn’t meant to stay small. Through the late 1970s and early 1980s, United grew the way many future consolidators would: acquisition by acquisition. It bought small HMOs across the Midwest and stitched them into a broader footprint. The playbook was simple and repeatable: acquire a plan with real members, use the larger combined scale to negotiate better provider rates, then centralize the administrative work to cut costs. That basic loop—buy, integrate, standardize—would become one of United’s defining muscles for the next half-century.

In 1984, United went public on NASDAQ under the ticker UNHC. The IPO did two things at once: it raised cash for more deals, and it gave Burke a powerful new currency—public stock—to keep the acquisition engine running. Through the rest of the 1980s, United pushed into more states and more offerings, growing into one of the larger managed care companies in the country. It still sat in the shadow of giants like Kaiser and many Blue Cross Blue Shield plans, but it was moving faster than most of its peers.

Even then, United was separating itself in one particular way: data. In an industry that still relied heavily on paper, intuition, and blunt actuarial averages, Burke invested in information systems that could actually track how care was being used—who the high-cost patients were, which services were driving spending, where utilization looked suspiciously high. In the late 1980s, that was unusual. Later, it would become foundational.

By 1990, United HealthCare was bringing in roughly four hundred million dollars a year. It had a reputation as a disciplined, efficient operator in a fragmented market. But it was still, at heart, a regional business—and the managed care market was about to go national. The executive who would take United from ambitious to dominant was already in the wings.

III. The McGuire Era: Scaling the Mountain (1991–2006)

William McGuire was not a typical insurance executive. He was a physician, trained at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, with a specialty in cardiopulmonary medicine. He practiced in Colorado Springs, ran a small health plan called Peak Health Plan, and joined United HealthCare in 1988 when United acquired Peak. In February 1991, McGuire became CEO. He was forty-two, intensely ambitious, and convinced that managed care didn’t have to remain a regional patchwork. It could be built like a national platform.

His vision sounded simple: make United the biggest, most data-driven health benefits company in America. While much of the industry fixated on local market share and plan design, McGuire fixated on scale, technology, and diversification. He talked about United less like an insurer and more like an information business that happened to sit in healthcare—an idea that would take the rest of the industry years to catch up to.

Under McGuire, the acquisition machine went from steady to relentless. In 1995, United bought MetraHealth Companies for $1.65 billion, with potential earnout payments that could bring the total to $2.35 billion. MetraHealth, a joint venture between Travelers and Metropolitan Life, administered benefits for large employers. The deal effectively doubled United’s membership and gave it a true national footprint. Then, in 1998, McGuire rebranded the company as UnitedHealth Group—a name meant to signal that this was no longer just an HMO, but an expanding set of businesses under one roof.

The late 1990s should have been the moment managed care cemented its dominance. Instead, it became a public relations disaster. The “HMO backlash” was real: patients hated gatekeeping, doctors hated prior authorization, and state legislatures piled on with “patients’ bill of rights” laws. Several competitors buckled. Oxford Health Plans, once a Wall Street darling, nearly collapsed in 1997 after discovering it had drastically underpriced its products. McGuire watched from a distance, then moved when the time was right. In 2004, UnitedHealth bought Oxford for $4.9 billion, adding millions of members and anchoring a stronger presence in the Northeast.

The defining deal of the era came next. In 2005, UnitedHealth acquired PacifiCare for $8.1 billion. PacifiCare was a major player in Medicare managed care, with deep roots in California and the Southwest. More importantly, it strengthened United’s position in what would become Medicare Advantage: the privatized version of Medicare where insurers receive a per-member monthly payment to manage care for seniors. McGuire was early in recognizing where the growth would come from. Employer insurance mattered, but government programs—especially Medicare Advantage—were where the industry’s next decade would be won. Enrollment in Medicare Advantage would surge from roughly five million in 2003 to more than thirty million by 2024, and UnitedHealth positioned itself to be the biggest beneficiary.

But membership wasn’t the real moat McGuire was building. The quieter project—one that would end up shaping everything United became—was data. Through the late 1990s and early 2000s, United poured money into claims processing, analytics, and what it called “health intelligence.” It built Ingenix, a subsidiary that sold healthcare data and analytics to hospitals, employers, and even other insurers. Ingenix mattered as a business, but it mattered more as a strategic weapon: it gave United an unusually detailed map of how healthcare dollars moved through the system. It could spot pricing anomalies, understand utilization patterns, and predict which patients were likely to become catastrophically expensive. In an industry that still ran on blunt averages, United was building a more precise instrument.

And then McGuire’s run ended the way so many empire-building runs do: not with a competitive defeat, but with a governance scandal.

In 2006, the Wall Street Journal reported that UnitedHealth had systematically backdated stock option grants—choosing grant dates that lined up with past low points in the share price. The practice was widespread in corporate America at the time, but the reporting and subsequent investigations portrayed United’s behavior as especially severe. The SEC found that McGuire received backdated options from 1994 through 2005, producing hundreds of millions of dollars in excess compensation. UnitedHealth ultimately had to restate $1.526 billion in cumulative earnings.

McGuire was forced out in October 2006. His settlement with the SEC, finalized in December 2007, required him to return roughly $468 million, including the first executive clawback under Section 304 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. A separate class-action lawsuit led by CalPERS and other institutional investors recovered $895 million from UnitedHealth and another $30 million from McGuire personally. He was barred from serving as an officer or director of any public company for ten years. The man who turned United into a national powerhouse left in disgrace—though with enough remaining wealth to buy a Major League Soccer franchise and to fund one of the world’s premier butterfly collections.

The board handed the company to Stephen Hemsley, a former Arthur Andersen managing partner who had joined UnitedHealth in 1997 as chief operating officer. Hemsley was McGuire’s opposite: quiet, methodical, and intensely operational. Where McGuire was the strategist and dealmaker, Hemsley was the integrator—the person who made the acquisitions actually function as one company. His job was immediate and unforgiving: stabilize UnitedHealth, repair trust with regulators and investors, and decide what this machine would become once the scandal stopped dominating every headline.

What came next wasn’t a retreat.

It was an expansion into something much bigger.

IV. The Optum Revolution: Vertical Integration Playbook (2007–2015)

Picture a whiteboard in a Minneapolis conference room around 2009. On one side: the old, straight-line model of health insurance. Employers pay premiums. Insurers pay claims. Providers deliver care. A chain of handoffs where everyone complains about the person upstream.

On the other side: a circle. Insurance connected to pharmacy benefits, data, care management, clinics, and the software that runs hospital billing. The lines run both ways. Every interaction throws off more information, which improves the next decision, which shapes the next interaction.

That circle was the blueprint for Optum.

It didn’t arrive as a single lightning-bolt idea. UnitedHealth had been collecting the pieces for years. Ingenix housed the data and analytics. A growing pharmacy operation managed drug benefits. Care management programs tried to steer members toward the right care at the right time. Under McGuire, those were separate businesses living under one corporate roof. Under Stephen Hemsley, they became a strategy: build a healthcare services company that could stand on its own, sell to the whole industry, and still have UnitedHealthcare as its anchor customer.

In 2011, Hemsley pulled those operations into a single entity and gave it a name: Optum. It broke into three parts. OptumHealth focused on care delivery and population health. OptumInsight—essentially the next chapter of Ingenix—sold data analytics, consulting, and technology to health systems, health plans, and government agencies. OptumRx ran the pharmacy benefit manager.

Even the branding was a strategic choice. “Optum” created daylight between these businesses and UnitedHealthcare the insurer. Hospitals and rival health plans might hesitate to buy services from an insurance company that competed with them. Buying from a health services and technology vendor felt different—even if the parent company was the same.

The logic was hard to ignore. Health insurance, by design, is a thin-margin business. It’s heavily regulated, intensely competitive, and difficult to differentiate for long. But the businesses around insurance—the ones that process, route, influence, and measure care—can earn higher margins and scale faster. Optum let UnitedHealth build that higher-value layer, with a built-in customer base massive enough to get the flywheel turning.

The clearest signal came in 2015, when UnitedHealth bought Catamaran for $12.8 billion and vaulted OptumRx into the top tier of pharmacy benefit managers. PBMs sit in the middle of prescription drugs: negotiating with manufacturers, shaping formularies, and processing enormous volumes of claims. The Catamaran deal didn’t just add lives. It gave UnitedHealth a new kind of leverage—negotiating power with drug companies that a standalone insurer simply couldn’t match.

That same year, UnitedHealth bought MedExpress, an urgent care chain, and made its first big step into owning care sites directly. The bet was simple: if you can guide members to clinics you run, you can capture economics that used to go to independent providers—and you can standardize care in ways that should, in theory, reduce waste.

Critics called it a conflict of interest. Supporters called it aligned incentives. The truth is, it was both.

Competitors saw the direction of travel and panicked accordingly. If UnitedHealth could be the insurer, the pharmacy middleman, the analytics vendor, and the care provider, then everyone else needed their own version of the stack. The industry reorganized. CVS bought Aetna in 2018. Cigna bought Express Scripts the same year. The wave wasn’t just about size; it was about owning more links in the chain so you couldn’t be squeezed by the company that did.

For investors, it was easy to see why this was so powerful. Optum became the growth engine and the margin engine. It was also a data engine: serving more clients created more claims and clinical information, which improved the analytics, which made the services more valuable, which attracted more clients. UnitedHealth was starting to look less like an insurer with some side businesses and more like a healthcare infrastructure company—one that could sell picks and shovels to the whole market while still controlling one of the biggest payers in it.

But the same structure that made Optum so valuable created the question that never quite went away: can one company own so much of the healthcare value chain without the incentives getting tangled?

If Optum’s analytics and consulting arm helped a hospital optimize billing and coding, and UnitedHealthcare then decided what to pay, whose interests were really being served? UnitedHealth argued the divisions operated independently, with strict information barriers and compliance walls. Skeptics saw a single empire learning the entire system from the inside—and getting to influence it at multiple points.

V. The Healthcare Services Transformation (2016–2020)

Andrew Witty arrived at UnitedHealth with a résumé that didn’t look like anyone else’s in the company’s history. He was born in Nantwich, England, joined Glaxo as a management trainee after graduating from the University of Nottingham in 1985, and climbed all the way to CEO of GlaxoSmithKline—one of the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies. In 2012, he was knighted for services to the British economy. When he joined UnitedHealth’s board in 2017, then stepped into the Optum CEO role in 2018 and became company president in 2019, it was more than a leadership change. It was a signal: UnitedHealth was thinking bigger than managed care.

Witty’s rise marked a pivot in ambition. UnitedHealth no longer wanted to be the nation’s biggest insurer that also owned a fast-growing services arm. It wanted to build the kind of care delivery footprint that could rival the traditional healthcare system—and then use it to prove a controversial idea: that an insurer-owned provider network could actually deliver better outcomes at lower cost. Analysts had a name for this: the “payvider” model. UnitedHealth’s bet was that the future belonged to companies that could combine the money side and the medicine side under one roof.

The dealmaking followed that logic.

In 2017, Optum bought Surgical Care Affiliates for $2.3 billion, picking up a nationwide network of ambulatory surgery centers—where an increasing share of procedures were moving as medicine shifted away from hospital stays and toward lower-cost outpatient settings. Owning those sites gave UnitedHealth another lever: direct control over where surgeries happened, and a way to push care out of high-cost hospital operating rooms and into facilities it could run and standardize.

Then came the bigger move. In 2019, UnitedHealth acquired DaVita Medical Group for $4.3 billion. DaVita Medical Group operated hundreds of clinics and employed thousands of physicians across markets like California, Colorado, Washington, and Florida. The deal brought roughly thirty-five thousand physicians and other providers into Optum’s orbit and made it one of the largest physician employers in the country. It also pulled UnitedHealth deeper into value-based care, where providers are rewarded for outcomes, not volume. In that world, prevention and coordination aren’t just good medicine—they’re good economics. And if the insurer and the provider are the same company, the incentives can, at least in theory, finally point in the same direction.

By 2019, Optum crossed one hundred billion dollars in annual revenue. That milestone mattered because it showed where the company’s center of gravity was shifting. UnitedHealthcare—the insurance arm—was still bigger. But Optum was growing faster, earning higher margins, and increasingly driving the story investors told about UnitedHealth. Wall Street started to view it less like an insurer with some ancillary businesses and more like a healthcare platform that also happened to sell insurance.

The technology push accelerated alongside the acquisitions. UnitedHealth invested heavily in data analytics, machine learning, and predictive modeling. It sat on claims data for more than a hundred million Americans—an asset that could be used to see patterns in utilization, identify high-risk patients earlier, and design interventions before costs exploded. And Optum didn’t keep those capabilities in-house. Through OptumInsight, it sold analytics and consulting services to hospitals, health systems, and even competing insurers. That expanded Optum’s reach—and extended UnitedHealth’s informational footprint across the industry.

The most consequential move of this period, though, was the deepening focus on government programs—especially Medicare Advantage, where private insurers administer Medicare benefits for seniors. UnitedHealth leaned into the product: it attracted members with extra benefits like dental, vision, and gym memberships that traditional Medicare typically didn’t include. By 2020, it served roughly seven million Medicare Advantage members, the largest MA plan in the country. The business model was attractive. CMS paid insurers a risk-adjusted, per-member monthly fee, and plans that could manage care efficiently kept the difference. UnitedHealth’s combination of analytics, care management, and a growing ability to control the provider side made it exceptionally strong at that game.

But that same strategy also set up the next wave of controversy. Medicare Advantage payments hinge on diagnosis codes: the sicker your members look on paper, the more CMS pays. That creates an enormous incentive to make sure every condition is captured and documented—what the industry calls “coding accuracy” and critics call “upcoding.” UnitedHealth’s in-home health assessment program, which sent clinicians to visit members and conduct comprehensive evaluations, became especially effective at surfacing previously undocumented diagnoses. Whether that was better care, better paperwork, or financial engineering would become one of the defining questions of UnitedHealth’s next chapter.

VI. The Change Healthcare Saga and Peak Controversy (2021–2024)

On a January morning in 2021, Optum announced it would acquire Change Healthcare for about thirteen billion dollars. The significance was immediate to anyone who understood how healthcare actually works in America: Change wasn’t a hospital chain or an insurer. It was infrastructure. The financial plumbing. Its systems routed claims, payments, and clinical information across the system—processing roughly fifteen billion transactions a year and touching about one in three patient records in the country. Hospitals used it to get paid. Pharmacies used it to run prescriptions. Insurers used it to adjudicate claims. If you wanted a clearer picture of where power sat in healthcare, you couldn’t ask for a better one.

The Department of Justice saw the same thing and sued to block the deal in February 2022. The argument wasn’t subtle: if UnitedHealth owned the pipes, it could see what flowed through them—including competitors’ sensitive claims data—and potentially use that visibility to compete more effectively on the insurance side. The government’s case boiled down to trust. Could you really believe a company this large would keep airtight firewalls between Change’s data and UnitedHealth’s own insurance and services businesses?

UnitedHealth offered a concession, promising to divest Change’s claims editing business, ClaimsXten, to address competitive concerns. In September 2022, a federal judge sided with UnitedHealth, ruling the government hadn’t shown the merger would substantially lessen competition. The deal closed soon after.

Then the DOJ’s fears came true in a way no one had modeled—not through competitive abuse, but through catastrophe.

On February 21, 2024, a ransomware group called BlackCat, also known as ALPHV, broke into Change Healthcare’s systems using stolen credentials for a Citrix remote access portal that did not have multi-factor authentication. The attackers encrypted key systems and siphoned off huge volumes of sensitive patient data. The breach ultimately affected about 192.7 million people, making it the largest healthcare data breach in U.S. history.

What made it so brutal wasn’t just the privacy damage. It was the operational shock. Change processed a significant share of the country’s pharmacy claims and electronic payments. When those systems went dark, pharmacies couldn’t reliably confirm coverage, hospitals couldn’t submit claims, and providers couldn’t get paid. A survey found that seventy-four percent of hospitals reported direct impacts on patient care, and sixty percent said it took anywhere from two weeks to three months to get back to normal. Small practices and rural hospitals—places without deep cash reserves—were hit especially hard, because a few weeks of delayed reimbursement can be the difference between making payroll and closing the doors.

UnitedHealth said it advanced about $4.7 billion to providers to help keep the system from seizing up. It also paid a twenty-two-million-dollar ransom—only for BlackCat to dissolve and for another group, RansomHub, to surface claiming it still had the stolen data.

On May 1, 2024, Andrew Witty testified before Congress and faced the question that cut through everything: how did a company of this size, sitting at the center of so much healthcare infrastructure, fail to implement something as basic as multi-factor authentication? By September 2024, UnitedHealth reported $2.457 billion in total costs tied to the attack.

The breach didn’t just expose a security failure. It put a spotlight on a structural one. If a single company’s systems could paralyze healthcare payments across the country, what did that say about consolidation? Had UnitedHealth become too central—too essential—too dangerous to fail? Critics of the Change deal argued they’d been proven right. Defenders countered that any platform this big would be a target, no matter who owned it.

And then, in early December, the story took a darker turn.

On December 4, 2024, Brian Thompson, the fifty-year-old CEO of UnitedHealthcare, was walking toward the New York Hilton Midtown for the company’s annual investor day when a masked gunman shot him at close range. Thompson died on the sidewalk. Five days later, police arrested Luigi Mangione, a twenty-six-year-old from a wealthy Baltimore family, at a McDonald’s in Altoona, Pennsylvania. Authorities said he had a 3D-printed pistol and a suppressor. The cartridge casings at the scene were engraved with “delay,” “deny,” and “depose”—words linked in the public imagination to insurance claim denials. Manhattan prosecutors charged Mangione with first-degree murder in furtherance of terrorism.

The public response was startling. Instead of a wave of sympathy for an executive killed in public, social media filled with rage at insurers—and, in many corners, a kind of admiration for the alleged shooter. Mangione’s face showed up on merchandise. A manifesto attributed to him, attacking the profit motives of the insurance industry, spread widely. Whatever you think of the crime, the reaction revealed something executives across healthcare had either missed or refused to see: the anger wasn’t abstract. It was personal.

For all the controversy, UnitedHealth’s 2024 results showed the sheer momentum of a four-hundred-billion-dollar machine. Revenue rose to $400.3 billion, up eight percent year over year. But earnings told the other side of the story. Net income fell to $14.4 billion from $22.3 billion in 2023—a steep drop driven by cyberattack costs, rising medical utilization, and mounting pressure across the Medicare Advantage business.

VII. The Modern Empire: Scale, Scope, and Strategy

To understand UnitedHealth Group in 2026, it helps to stop thinking of it as a single company. It’s three interlocking businesses—each powerful on its own, and together something closer to a healthcare operating system.

First is UnitedHealthcare, the insurance arm. With roughly fifty million medical members across commercial plans, Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid, it’s the largest health insurer in America by enrollment. In 2024, the insurance operation generated $298.2 billion in revenue—so large it would rank as a major Fortune 500 company on its own. Commercial coverage, sold mainly through employers, accounts for around thirty million members. Medicare Advantage adds another seven to eight million seniors. Medicaid managed care serves about seven million low-income Americans. This is the front door: the customer acquisition engine. It brings people into the system—and their healthcare spending flows through everything else UnitedHealth owns.

Second is Optum, the services empire, now at about $253 billion in annual revenue across three divisions. OptumHealth is where UnitedHealth’s “payvider” ambition becomes real. It operates one of the country’s largest physician groups, employing or affiliating with about ninety thousand physicians across roughly twenty-two hundred locations, and it serves 4.7 million patients in value-based care arrangements. It also runs ambulatory surgery centers, urgent care clinics, and home health operations—expanding further after the LHC Group acquisition in 2023 and the Amedisys deal, which closed in August 2025 after a long antitrust fight that required divesting 164 locations across nineteen states.

OptumRx is the pharmacy benefit manager. In 2024, it generated $133.2 billion in revenue, managing drug benefits for tens of millions of people and negotiating rebates with pharmaceutical manufacturers. OptumInsight is the “brains and tools” unit: data analytics, technology services, and consulting for hospitals, health plans, and government agencies. It’s the smallest division by revenue at $18.8 billion, but it sits in an unusually influential position—because it helps run the back office of American healthcare.

The third business is the least visible, but arguably the most important: the data and technology infrastructure tying everything together. UnitedHealth’s databases hold claims information on more than a hundred million Americans. Its analytics can forecast which patients are likely to be hospitalized, which treatments are likely to work best, and which providers deliver care most cost-effectively. And because UnitedHealthcare and Optum are intertwined, that information can move through the system in feedback loops that are hard for non-integrated competitors to match. An OptumHealth physician treats a UnitedHealthcare member. The claim becomes data. The data refines the algorithms. The algorithms shape care management. Better management can improve outcomes and lower costs, which can improve insurance margins. It’s a cycle—virtuous, or vicious, depending on where you sit.

Internationally, the story has been far less triumphant. UnitedHealth pushed into Brazil, the United Kingdom, and other markets through the 2012 acquisition of Amil and subsequent deals. But those businesses never reached the scale or profitability of the U.S. operation, and UnitedHealth has been retrenching—selling international assets and refocusing on the American market, where its integrated model has the clearest edge.

For years, the financial trajectory looked like a clean growth narrative. Revenue climbed from $242 billion in 2019 to $400.3 billion in 2024—roughly a ten percent compound annual growth rate. Then 2025 forced a reset. Full-year results, reported in January 2026, showed profit falling to $12.1 billion, the lowest since 2018. The adjusted medical care ratio rose to 88.9 percent—nearly eighty-nine cents of every premium dollar going straight out the door to pay for care. And the company warned that 2026 revenue would decline by about two percent, which would be its first contraction since 1989.

The reasons weren’t a single shock so much as pressure from every direction: Medicare Advantage rate pressure from CMS, which proposed a near-zero rate increase for 2027; rising utilization as patients who delayed care during and after the pandemic came back into the system; and the ongoing aftershocks and costs of the Change Healthcare breach. UnitedHealth said it would exit 109 counties and lose 1.3 to 1.4 million Medicare Advantage members in 2026, including a full exit from Vermont. For the first time in decades, it looked like the era of effortless, uninterrupted expansion might be over.

VIII. Power and Politics: The Regulatory Battlefield

In January 2026, Stephen Hemsley—back in the CEO chair after an eight-month return tour—sat in front of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and did something you almost never hear from the head of a health insurer: he conceded the temperature in the room. UnitedHealthcare, he said, would voluntarily eliminate and rebate its profits on individual Affordable Care Act marketplace plans for 2026.

For a company that built its empire by mastering the rules, this wasn’t charity. It was triage. Because by 2026, UnitedHealth wasn’t facing one investigation or one bad headline. It was facing pressure from every side of the political and regulatory map at once.

The biggest and most consequential front is Medicare Advantage. In February 2025, the Department of Justice opened a civil probe into allegations that UnitedHealth inflated diagnosis codes to drive higher risk-adjusted payments from the federal government. Then the stakes rose. In May 2025, the Wall Street Journal reported that federal prosecutors were interviewing former employees about billing practices, suggesting the inquiry had broadened into criminal territory.

At the center of the scrutiny is a program UnitedHealth has talked about for years as a care improvement tool: in-home health assessments. Nurses visit Medicare Advantage members, perform comprehensive evaluations, and document conditions. The government’s theory is simple: those visits systematically surfaced diagnoses that increased CMS payments. Government estimates said the assessments produced an average of $2,735 in additional federal payments per visit—adding up to $8.7 billion in additional payments in 2021 alone.

To be clear, this isn’t a UnitedHealth-only issue. The GAO and the HHS Inspector General have repeatedly found that Medicare Advantage plans, as a category, tend to code diagnoses more intensively than traditional Medicare—leading to excess payments. But UnitedHealth is the largest player in the space, which makes it both the biggest beneficiary and the easiest target. The company’s position has been consistent: its coding is accurate, it follows CMS guidelines, and the assessments catch real conditions that would otherwise go unmanaged.

Another active front is mental health parity—and this one carries a particular kind of reputational weight. In April 2024, the Ninth Circuit revived a class-action lawsuit alleging UnitedHealth applied tougher standards to mental health claims than to comparable medical and surgical claims, violating the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. In May 2024, Minnesota fined the company $450,000 for similar violations at the state level. And earlier, UnitedHealth reached a federal settlement totaling $15.6 million, including $13.6 million paid directly to members whose mental health claims had been wrongfully denied—described as the first DOJ enforcement of the parity law against a health insurer.

Then there’s prior authorization, the policy lever that may generate more day-to-day hatred than any other part of the modern insurance system. Prior auth is how insurers ration utilization: before certain procedures, scans, or drugs are covered, a doctor has to ask permission. UnitedHealth relies on it heavily as a cost-control tool. Doctors and patient advocates argue it delays care, forces clinicians into bureaucratic battles, and sometimes results in harmful denials. They also point to the administrative drag: an estimated $35 billion a year in industry-wide costs.

After Brian Thompson was murdered, the words engraved on the shell casings—“delay,” “deny,” “depose”—became a blunt slogan for that entire grievance. And legislators responded the way they usually do when a policy problem catches fire publicly: with bills. Multiple states introduced measures to restrict prior authorization, and CMS proposed federal rules aimed at faster turnaround times and more transparency.

Hovering above all of it is the question that makes regulators most uneasy, because it doesn’t fit neatly into the usual boxes: antitrust. UnitedHealth’s model depends on vertical integration, which means it increasingly competes with the same organizations it also serves. OptumInsight can sell analytics to a hospital that negotiates rates with UnitedHealthcare. OptumRx can manage pharmacy benefits for members of other insurers. Even if every compliance wall holds perfectly, the conflict-of-interest concern is structural, not hypothetical.

The DOJ’s failed attempt to block the Change Healthcare deal showed how hard it is to prove antitrust harm in healthcare, where the “consumer welfare” framework struggles to capture a system built on intermediaries, opaque pricing, and cross-subsidies. But the political weather has changed. In January 2026, the Senate Judiciary Committee released a report—based on a review of fifty thousand pages of UnitedHealth records—that zeroed in on aggressive Medicare Advantage coding practices.

And finally, there’s a newer kind of power Washington is still learning how to regulate: data. With Change Healthcare folded into Optum, UnitedHealth sits on information that touches a vast share of U.S. healthcare transactions. That data is commercially valuable, but it’s also strategic intelligence—signals about competitors’ pricing, operations, and patient mix. UnitedHealth says it maintains strict information barriers between business lines. Whether those barriers are truly airtight, and whether they can stay that way as the company’s data footprint keeps growing, is the kind of question existing antitrust law isn’t really designed to answer.

IX. Playbook: The UnitedHealth Method

Strip away the controversy and the politics and you’re left with a strategy that’s been remarkably consistent for decades: build advantages that are hard to unwind in a business where the rules change, the margins are thin, and the regulators are always watching. The same moves that powered UnitedHealth’s rise also explain why it attracts so much scrutiny now.

The centerpiece is vertical integration. Most insurers live in a narrow lane: collect premiums, build networks, pay claims. UnitedHealth decided that wasn’t enough. It pushed up and down the stack—into physician groups and clinics, into pharmacy benefits, into analytics, and into the claims and payments rails that keep the system moving. That breadth creates economies of scope: the ability to reuse the same data, software, and operational playbooks across multiple businesses. When UnitedHealthcare designs a Medicare Advantage plan, it isn’t starting from scratch. It can lean on OptumHealth’s clinical footprint to anticipate utilization, OptumRx’s pharmacy data to shape formularies, and OptumInsight’s tools to run the admin engine behind it. A less integrated competitor either has to build those capabilities, buy them, or rent them—often from Optum.

The real moat, though, is data and analytics. UnitedHealth processes information tied to more than a hundred million Americans. That scale makes patterns visible that no single hospital system, physician group, or regional insurer can reliably see—how risk shifts, which interventions actually reduce admissions, where costs are spiking, which providers deliver care more efficiently. And it feeds on itself: more members and more transactions create more data, which improves the models, which improves pricing and care management, which helps win more business. It’s one of the closest things healthcare has to a network effect.

Then there’s government programs expertise—the growth engine hiding in plain sight. Medicare Advantage, Medicaid managed care, and dual-eligible populations have been among the fastest-growing corners of the insurance market, propelled by demographics and policy design rather than the economic cycle. UnitedHealth got there early and built specialized muscles—risk adjustment, care management, and regulatory compliance—that take years to develop. Its scale in Medicare Advantage, at roughly a quarter of the national market, reinforces itself: it can negotiate with providers from a stronger position, compete on star ratings, and design supplemental benefits with more confidence about the economics.

Another underrated advantage is the acquisition and integration machine. Over five decades, UnitedHealth has done deal after deal—from MetraHealth to Amedisys—without the kind of repeated integration blowups that plague most serial acquirers. The rhythm is familiar: buy a business with a capability you want, migrate it onto your platforms, cross-sell across the rest of the portfolio, and squeeze costs through scale. That discipline is part of why the company kept compounding even as healthcare lurched through backlash cycles, policy changes, and scandals. The most visible disruption in recent years, the Change Healthcare situation, wasn’t a classic integration failure so much as an external shock: the cyberattack.

Capital allocation has been similarly methodical. UnitedHealth has returned a large share of operating cash flow to shareholders through dividends and buybacks while still funding acquisitions and internal investment. The dividend has risen for more than a decade, and steady repurchases have reduced the share count over time, boosting per-share results. That predictability is a big reason UnitedHealth became a staple holding for major institutions.

And finally, the part of the playbook that explains the backlash: UnitedHealth has repeatedly been willing to push right up to regulatory boundaries. It expands into adjacent markets—pharmacy benefits, physician practices, healthcare data and payments—where the incentive conflicts are obvious and the scrutiny is inevitable, but the rules don’t clearly forbid the move. The pattern has often been to move first, build scale, and then fight or negotiate from a position of strength.

It worked spectacularly for years. It also built up the political risk that now hangs over the entire model.

X. Bull versus Bear Case

The Bull Case

The argument for UnitedHealth starts with a force that doesn’t care about Washington, quarterly guidance, or public sentiment: demographics. Every day, a huge cohort of Americans ages into Medicare. And every one of those new seniors is a potential Medicare Advantage member. UnitedHealth has been building for that moment for two decades. It has the biggest footprint in MA, deep experience with risk adjustment and star ratings, and the scale to offer supplemental benefits that smaller plans struggle to fund. Even if CMS tightens payment rates, UnitedHealth is positioned to take share in a market that keeps expanding.

The second pillar is the integrated model—the thing that makes UnitedHealth so hard to compare to a normal insurer. In Hamilton Helmer terms, this is process power stacked on top of scale economies. UnitedHealth doesn’t just write policies. It owns or controls pieces of the care journey: clinics and physician groups, the pharmacy benefit manager, the analytics, and now even more of the claims and payments plumbing. Competitors have tried to assemble similar stacks, but it’s brutally hard. CVS built a payer-plus-pharmacy-plus-retail story with Aetna and later bought Oak Street Health, yet integrating everything into a smooth operating system has been messy. Cigna has PBM scale through Express Scripts but doesn’t have anything close to OptumHealth’s care delivery footprint. Humana and Elevance remain far more payer-centric. The challenge isn’t only buying the parts—it’s coordinating them. Running an organization of this scope means aligning tens of millions of members, a massive physician network, and a pharmacy operation at industrial scale. That capability takes years to develop, and it doesn’t come in a box.

Third is cash. Even in a year full of bad headlines, UnitedHealth still threw off enormous operating cash flow—about $24.2 billion in 2024. That kind of internal funding matters. It lets the company keep investing, keep buying, and keep returning capital to shareholders, while still absorbing shocks—like the multibillion-dollar cost of the Change Healthcare cyberattack—without tipping into a balance-sheet crisis.

Step back and the competitive structure looks, if not comfortable, at least defensible. Insurance is difficult to enter because of licensing, capital requirements, and network rules. Healthcare services are difficult to enter because of provider recruitment, technology platforms, and data advantages that compound over time. Provider supplier power is partially muted when you own more of the provider layer yourself. Buyers are fragmented—millions of members and thousands of employers. And the most discussed “substitutes,” from Big Tech disruption to a single-payer overhaul, are real possibilities but not immediate realities.

The Bear Case

The bear case isn’t that UnitedHealth is badly run. It’s that the world around it is turning—fast—and the company is now big enough that every one of those turns becomes existential.

The first and most direct threat is regulation, especially in Medicare Advantage. The DOJ’s scrutiny of coding practices has escalated to the point where it could force real changes in how risk adjustment works, potentially pulling back a major profit lever not just for UnitedHealth, but for the category. At the same time, CMS has been signaling tougher economics. The proposed near-zero Medicare Advantage rate increase for 2027 didn’t just rattle executives—it wiped out a massive amount of industry market value in a day, a reminder that Washington can reprice this business overnight. UnitedHealth’s expectation that it will lose 1.3 to 1.4 million MA members in 2026 could end up looking like a one-year adjustment. Or it could be the first visible crack in the growth engine.

The second threat is politics, powered by culture. The backlash after Brian Thompson’s murder didn’t create skepticism of insurers—but it amplified it, and it gave lawmakers cover. Prior authorization reform, once a niche policy fight, has moved into the mainstream in multiple states. Congressional scrutiny has intensified. In that environment, even “voluntary” concessions, like Hemsley’s marketplace profit move, start to look less like one-off gestures and more like the cost of doing business under a spotlight.

Third is the basic math of insurance margins. The medical care ratio has moved the wrong way—rising from 83.2 percent in 2023 to 85.5 percent in 2024 to 88.9 percent in 2025. The higher that number goes, the more premium dollars are simply passed through to pay for care, leaving less for administrative costs and profit. Small changes here translate into enormous dollars at UnitedHealth’s scale. If utilization stays elevated and pricing can’t keep up, the pressure becomes structural. And management’s own outlook pointed to that reality: 2026 guidance implied meaningfully lower earnings per share than the company generated in 2024.

Fourth is operational fragility—exposed, in the worst possible way, by Change Healthcare. The detail that stuck with people wasn’t just “ransomware happened.” It was that stolen credentials and missing multi-factor authentication helped take down a system processing billions of transactions. That’s not a typical cybersecurity story. That’s a governance story, and it raises a harder question: when you own critical infrastructure for the entire healthcare system, the tolerance for failure approaches zero.

Finally, there’s the long-horizon disruption risk. Helmer’s idea of counter-positioning is the uncomfortable one here: a fundamentally different entrant could build a healthcare offering that feels simpler, more modern, and less burdened by the reputation of traditional insurance. Amazon’s moves with One Medical and PillPack are still small relative to UnitedHealth’s scale, but they’re a reminder that consumer-facing platforms can choose their moment—and once they commit, they can move fast.

Key Metrics to Watch

If you want the simplest dashboard for whether UnitedHealth is steadying itself or sliding into a tougher era, two indicators matter more than the rest.

The first is the medical care ratio: how much of every premium dollar goes out the door to pay medical claims. It’s the cleanest read on utilization, pricing discipline, and cost trend all at once—and the recent deterioration is the clearest warning sign that the old margin structure is under strain.

The second is Medicare Advantage membership. MA has been UnitedHealth’s most important growth engine for more than a decade. Losing 1.3 to 1.4 million members in 2026 could prove to be a temporary pullback in response to rate pressure. Or it could mark the beginning of a longer, more structural shift in the company’s government-programs franchise. Which one it is will shape the entire investment story from here.

XI. Epilogue: The Future of American Healthcare

UnitedHealth Group sits in a strange, uneasy place in America’s healthcare system. It’s big enough that you can’t ignore it, and embedded enough that you can’t easily replace it. It runs critical infrastructure, it insures tens of millions of people, and it employs or affiliates with a vast physician network. The Change Healthcare attack made the point in the most painful way possible: when something breaks inside UnitedHealth, it doesn’t stay inside UnitedHealth. It ripples out to pharmacies, hospitals, small clinics, and patients—fast.

That’s why the debate around the company is so charged. The tension between profit and public health isn’t new in American business, but in healthcare the stakes are unusually literal. Cost control can mean fewer unnecessary tests. It can also mean delayed treatment. The public fury that followed Brian Thompson’s killing wasn’t just about one tragedy; it was a raw signal of how many Americans experience insurers as obstacles, not as partners in care. Fair or not, that perception is now a governing reality. It shapes what lawmakers feel safe proposing, what regulators choose to pursue, and how every corporate decision gets interpreted.

Technology adds another layer of uncertainty. Done right, AI could make care management more proactive—finding people headed toward crisis before they land in the emergency room. Telehealth could extend Optum’s clinical reach to communities where access is scarce. But the same tools could also level the playing field. If the next decade makes data more portable and analytics more commoditized, UnitedHealth’s information advantage shrinks—and the door opens for new entrants with fewer conflicts and a cleaner brand, from retail chains to tech companies to new public-sector platforms.

And then there’s the question that never fully goes away: single payer. A Medicare-for-All system would wipe out the private insurance market as we know it. But it wouldn’t necessarily wipe out UnitedHealth’s capabilities. Optum’s services—claims routing, analytics, pharmacy infrastructure, care delivery—could still exist as contractors to a government payer. The more plausible near-term path is messier: bigger public programs, tighter rules, and more pressure on how insurers make money. That world doesn’t end the industry. It squeezes it.

In that world, value-based care becomes UnitedHealth’s strongest argument for why its model should be allowed to exist at all. If it can show that combining insurance, data, and care delivery truly improves outcomes and lowers costs, then vertical integration looks less like an extraction machine and more like a redesign of incentives. The results so far have been uneven. Some Optum programs point to real improvements; others haven’t meaningfully slowed the underlying cost curve.

What isn’t in dispute is the scale of what UnitedHealth has built: a company that touches how Americans get covered, where they seek care, how providers get paid, and how the system measures itself. Whether that concentration of power ends up serving patients or hurting them—whether it’s the future of healthcare or a step too far—won’t be decided on earnings calls. It’ll be decided by regulators and legislators, by court rulings and policy shifts, and by the lived experience of patients trying to navigate a system that remains, for all its sophistication, punishingly expensive and painfully hard to use.

XII. Recent News

The biggest jolt in UnitedHealth’s recent story came in May 2025, when the company abruptly changed leaders. Andrew Witty, CEO since February 2021, stepped down on May 13, citing personal reasons. He left behind a company that, on his watch, had grown from about $257 billion to roughly $400 billion in annual revenue. The timing was hard to miss: a day later, the Wall Street Journal reported that the DOJ had expanded its Medicare Advantage investigation to include potential criminal scrutiny. Stephen Hemsley—the former CEO who ran UnitedHealth from 2006 to 2017 and had stayed on as chairman—returned to the corner office, with a compensation package that included $60 million in stock options.

When UnitedHealth reported full-year 2025 results in January 2026, the numbers showed how quickly the narrative had turned. Profit fell to $12.1 billion, the lowest in seven years, and the adjusted medical care ratio climbed to 88.9 percent. Management also delivered a rare warning: 2026 revenue was expected to fall about two percent, which would be the first contraction since 1989. Even the earnings outlook signaled a new era—guidance of more than $17.75 per share for 2026, down sharply from the $27.66 of adjusted EPS the company posted in 2024.

Medicare Advantage, long UnitedHealth’s most important growth engine, was where the pressure felt most immediate. CMS proposed a 0.09 percent headline rate increase for Medicare Advantage for 2027—effectively a cut once medical inflation is considered. After the announcement on January 27, 2026, UnitedHealth’s stock sank about twenty percent in a single day, wiping out roughly $80 billion of market value. From a peak above $630 in November 2024, the shares fell to around $287 by late January 2026—down more than fifty percent from their all-time high.

The company also said it would pull back from the market directly: exiting 109 counties and losing an estimated 1.3 to 1.4 million Medicare Advantage members in 2026, including a full withdrawal from Vermont. And on the provider side, cracks widened. Thirty-two health systems dropped various UnitedHealthcare Medicare Advantage plans across 2024 and 2025. HealthPartners, one of those systems, alleged that UnitedHealthcare’s denial rates were “up to ten times higher than other insurers.”

Hemsley’s return came with a clear attempt to lower the political temperature. In January 2026 testimony before Congress, he said UnitedHealthcare would voluntarily eliminate and rebate its profits on individual ACA marketplace plans for 2026. Meanwhile, the DOJ investigation into Medicare Advantage coding practices continued, with reports that it had widened to include Optum Rx billing and physician reimbursement practices.

Even the company’s long-running deal drama finally resolved, but not cleanly. The Amedisys acquisition—announced in June 2023—closed in August 2025 only after a DOJ settlement required UnitedHealth to divest 164 locations across nineteen states, representing about $528 million in annual revenue. Separately, Amedisys was fined $1.1 million for filing a false pre-merger notification with the FTC.

XIII. Links and Resources

- UnitedHealth Group annual reports and SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, proxy statements) at sec.gov

- Congressional Budget Office reports on Medicare Advantage risk adjustment and payment accuracy

- Government Accountability Office studies on Medicare Advantage coding intensity

- Senate Judiciary Committee report on UnitedHealth’s Medicare Advantage practices (January 2026)

- House Energy and Commerce Committee hearing transcripts, including Andrew Witty’s May 2024 testimony on the Change Healthcare cyberattack and Stephen Hemsley’s January 2026 testimony on healthcare affordability

- Department of Justice filings in the Change Healthcare merger challenge

- American Hospital Association reporting on how the Change Healthcare cyberattack affected providers

- HHS Office of Inspector General reports on Medicare Advantage upcoding and payments

- An American Sickness by Elisabeth Rosenthal (healthcare industry incentives and consolidation)

- The Price We Pay by Marty Makary (healthcare pricing and transparency)

- Kaiser Family Foundation data on Medicare Advantage enrollment, payments, and market structure

- Hamilton Helmer, 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy

- Michael Porter, Competitive Strategy and related healthcare competition frameworks

- Acquired.fm podcast archives for adjacent episodes and industry context

- STAT News and Fierce Healthcare for ongoing coverage of UnitedHealth and regulatory developments

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music