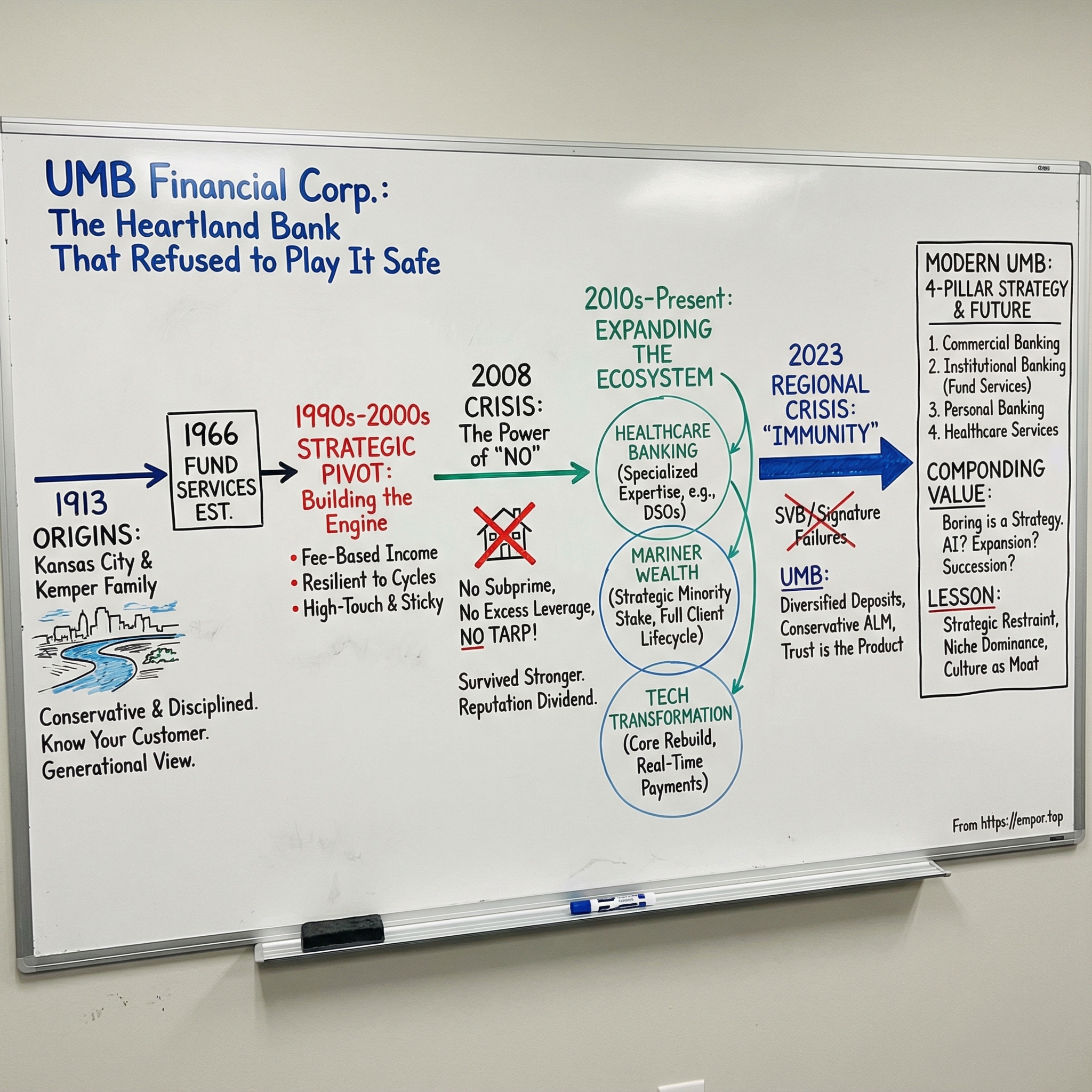

UMB Financial Corp.: The Heartland Bank That Refused to Play It Safe

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture March 2023. The U.S. banking system is lurching into its worst moment since 2008. Silicon Valley Bank collapses in one of the largest bank failures in American history. Signature follows days later. First Republic wobbles. Regional bank stocks get crushed, some dropping by staggering amounts in a single session. Depositors don’t wait around for reassurance—they move money fast.

And in Kansas City, Missouri, a regional bank called UMB Financial watches the chaos unfold and… barely flinches.

While peers scrambled to raise liquidity, tighten lending, and craft calming statements for skittish customers, UMB saw something different: deposits came in. For a bank with a reputation built on conservative lending and steady execution, the moment wasn’t a surprise so much as a stress test it had been preparing for, quietly, for decades.

That’s the mystery we’re unpacking: how did a Midwestern bank headquartered in a city better known for barbecue and jazz than high finance avoid every major financial shock of the last half-century—while also building a fund services business that can stand next to institutions many times its size? And how did a family-controlled bank keep its discipline across four generations when most family enterprises don’t even make it to the third?

The answer runs through cattle loans and custody services. Through a family named Kemper, whose approach to banking bordered on monastic. And through a strategic playbook that’s useful well beyond finance—because it reveals the difference between chasing returns and compounding value.

Today, UMB is the largest publicly traded bank based in Missouri, with banking, institutional, and asset-servicing operations across eight states. It’s organized into three segments: Commercial Banking, Institutional Banking, and Personal Banking. But those labels don’t explain what makes UMB worth studying. The real story is how it got here: a century of strategic restraint, a willingness to ignore the herd, and a culture that treated risk management as a core belief system—not a compliance requirement.

We’re going to trace the arc from R. Crosby Kemper Sr.’s founding vision in 1913 to the present day. We’ll follow the fund services pivot that helped turn a regional lender into a nationally significant custodian. We’ll dig into why UMB came out of 2008 stronger than it went in, and why the 2023 panic barely left a mark. And then we’ll apply a couple of strategic lenses—Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers—to separate what’s impressive from what’s actually defensible.

The themes are surprisingly universal: the power of saying no, the value of boring consistency, and the advantage that comes from going deep instead of going broad. Let’s start at the beginning.

II. Origins: Kansas City and the Kemper Family Legacy (1913–1980s)

To understand UMB, you have to start with Kansas City in 1913—and with the kind of banker who could look at a fast-growing, rough-edged river town and see something more durable than a boom.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Kansas City sat at a geographic sweet spot: where the Kansas and Missouri rivers meet, and where rail lines stitched the agricultural heartland to the industrial East. As the railroads arrived and multiplied, the city became a logistics machine. Cattle moved through. Meatpacking followed. So did the broader ecosystem—farm supply, warehousing, trade. Kansas City wasn’t just growing; it was becoming a hub.

That’s the environment R. Crosby Kemper Sr. stepped into when he founded City Center Bank in 1913. His vision was almost aggressively unglamorous. While plenty of bankers chased the biggest names and the flashiest deals, Kemper built around a quieter idea: know your customers, underwrite with discipline, and measure success in decades, not quarters.

The world around him reinforced that mindset. In an agricultural economy, everybody understood volatility. One bad season could erase years of work. That reality teaches a kind of humility—diversify, don’t overreach, and make sure you can survive the downside. Over time, that sensibility became institutional habit at City Center Bank: conservative underwriting, deliberate growth, and relationships that outlasted any single transaction.

Kansas City also gave that approach room to work. The city didn’t end up as a one-industry company town. It grew into a more diverse regional economy, and that diversity rewarded bankers who actually understood the specifics—how a business made money, where its risks hid, what could go wrong. Local knowledge wasn’t a slogan; it was an edge against faraway banks making decisions from a distance.

Out of that came a Kemper philosophy that would shape the institution for generations. Conservatism wasn’t treated as timidity—it was treated as strategy. Banking wasn’t about swinging for the fences; it was about avoiding the blowups while compounding steady returns. Expertise mattered more than size. And the time horizon was generational: make decisions your grandchildren won’t have to apologize for.

As the business grew, the structure evolved. In 1971, City Center Bank was incorporated as United Missouri Bancshares. That consolidation marked a shift from a single-city institution to a broader regional strategy. The Kempers began acquiring smaller banks across Missouri and, eventually, into neighboring states—but the playbook didn’t change. No overpaying to “win” a deal. No stretching to fit mismatched cultures. No loosening standards just to chase growth.

In 1994, the company took on a new name: UMB Financial Corporation. Dropping “Missouri” mattered. It was a signal that the bank’s ambitions were widening beyond the state line—and that some of what it was building could compete on a national stage. It wasn’t a reinvention so much as a reframing: the roots stayed put, but the map got bigger.

The most telling part of this era is, in many ways, what didn’t happen. The 1970s and 1980s brought deregulation, speculation, and then the savings and loan crisis that wiped out thousands of institutions. Plenty of banks chased hot money, made concentrated real estate bets, and discovered—too late—that leverage doesn’t forgive mistakes. UMB largely stayed the course: steady, profitable, and stubbornly boring.

Family governance was a big reason. With the Kempers deeply involved, UMB wasn’t forced into the same quarterly, momentum-driven decision-making that pushed other banks to take on risks they didn’t fully control. They could say no to deals that looked great in year one but dangerous by year five. They could invest in capabilities that took time—people, systems, compliance—without needing an immediate payoff.

And that set the pattern that would define UMB’s reputation: cycles of excess, followed by crisis, followed by UMB coming through intact—and often stronger. The question wouldn’t be whether the pattern existed. It was already baked into the culture. The question was whether that culture could hold as the bank scaled, markets changed, and leadership eventually transitioned. That test was coming.

III. The Strategic Pivot: Building the Fund Services Engine (1990s–2000s)

By the early 1990s, UMB’s leadership was staring at a problem that every regional bank had, whether they admitted it or not: traditional banking was getting commoditized. Deregulation had turned up the heat. National banks were pushing into regional markets. Pricing got tighter, relationships got harder to defend, and the old formula—gather deposits, make loans, live off the spread—felt less like a moat and more like a treadmill.

So UMB asked a sharper question: if the core of banking is becoming a race to the bottom, where can a conservative, operationally excellent institution win without taking swing-for-the-fences risk?

The answer had been sitting in the business for decades. UMB Fund Services had been established in 1966, making it one of the earliest independent fund administrators in the country—and today it manages more than $80 billion in assets across mutual funds, hedge funds, venture capital funds, exchange-traded funds, and more. What changed in the 1990s wasn’t that fund services appeared out of nowhere. It’s that UMB began treating it as a true growth engine, not a side business.

The insight was simple and, at the time, contrarian: fund administration rewarded the exact strengths UMB had been compounding for generations—process discipline, regulatory seriousness, and long-term client relationships. And unlike lending, it didn’t require tying up large amounts of balance sheet capital.

In plain terms, lending can be great, but it’s a business where you put money at risk to earn a spread—and you’re always one credit cycle, one rate shock, or one overconfident underwriting decision away from pain. Fund services is different. You’re providing the operational plumbing—fund accounting, custody, compliance reporting, investor servicing—and getting paid fees for doing it well. If you become embedded in how a manager runs their fund, you don’t get swapped out lightly. The switching costs are real, because the “product” is the day-to-day functioning of their business.

That’s why the pivot mattered. Fund services offered higher-margin, lower-capital-intensity revenue, with stickier relationships than most traditional banking products. And it offered something else UMB loved: resilience. Fee income from servicing didn’t disappear the moment loan demand softened. It gave the company a counterweight to the credit cycle.

Of course, the strategy wasn’t just about economics—it required a cultural leap. Relationship bankers were trained to think in transactions: originate, price, close. Fund servicing is the opposite: relentless operational accuracy, client retention, and expanding the scope of what you do for the customer over time. Success looks like fewer surprises, not bigger wins. That meant different talent, different incentives, and a different definition of “growth.”

UMB leaned into a high-touch model, assigning dedicated teams to clients and building relationships designed to last for decades, not quarters. That approach wasn’t flashy, but it fit the Kemper style perfectly: earn trust through consistency, then keep it through execution.

The move into alternatives proved especially well-timed. As hedge funds and private equity expanded through the 1990s and 2000s, managers needed administrators who could handle complex structures, illiquid valuations, and increasingly demanding regulatory requirements. The biggest custodian banks often felt too slow and bureaucratic for smaller, fast-moving firms. Smaller administrators could be nimble, but many didn’t have the technology or scale to grow with their clients. UMB found the middle ground: sophisticated enough for complexity, stable enough to inspire confidence, and responsive enough to feel like a partner.

And it invested accordingly. UMB Fund Services put money into proprietary technology platforms aimed at streamlining operations and giving clients timely access to data. That created a compounding loop: better systems enabled better service, better service won more clients, and more clients funded more investment.

For anyone trying to understand UMB’s strategic DNA, this era is the tell. The company didn’t try to outgun the giants at being a universal bank. It looked for white space where its existing strengths would matter more than sheer size—and then it committed early.

The fund services engine would go on to provide stable, scalable fee income through cycle after cycle, turning UMB into something more than “just a bank.” But before the full payoff became obvious, the strategy faced its harshest proving ground: the global financial crisis—when the value of a long-practiced ability to say “no” suddenly mattered more than all the cleverness on Wall Street.

IV. Surviving the Financial Crisis: The Power of "No" (2007–2010)

In the run-up to 2008, the easiest way to look smart in banking was to say yes.

Yes to subprime mortgages that could be bundled, sliced, and sold as if risk had been engineered away. Yes to leveraged lending with thin protections. Yes to complex derivatives and off-balance-sheet structures that boosted returns—right up until they detonated. Yes to balance sheets funded with short-term money that vanished the moment confidence cracked.

The banks that said yes the loudest posted the biggest numbers… and then produced the most spectacular failures. Some disappeared. Some were absorbed. Others survived only because the government stepped in.

UMB said no.

Not because it predicted the precise shape of the collapse, but because it didn’t need to. “No” was the default setting. The Kemper-era habits—know the customer, understand the downside, underwrite like you’ll own the risk through a full cycle—weren’t branding. They were operating system. And in 2008, that operating system mattered more than any one product line.

UMB navigated the crisis with the same conservative approach to risk it had practiced for generations. Its relationship-first model and disciplined underwriting kept it away from the worst landmines.

And what UMB didn’t have in 2007 is what made the difference: no meaningful exposure to subprime mortgages or the securitized products built on top of them, no big derivatives book full of positions people couldn’t explain, no dependence on fragile short-term funding, and no outsized bet on overheated commercial real estate. The balance sheet looked—by the standards of the era—almost boring.

That “boring” showed up where it counted. UMB maintained strong capital through the crisis and was one of the few regional banks that did not need to take funds from the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP).

That independence bought real freedom. Banks that took TARP faced restrictions and scrutiny, and they carried a permanent asterisk in the minds of customers and recruits: you needed help. UMB didn’t have that stain. It could keep making decisions on its own timetable, with its own flexibility, while others were negotiating survival.

So when the crisis forced competitors to retrench—selling assets, shrinking loan books, cutting staff—UMB had room to play offense. In every panic there’s a flight to perceived safety, and after 2008, businesses and institutions started asking questions they hadn’t bothered with before: Where were you when things went bad? How do you manage risk? Will you still be here a decade from now?

UMB had unusually clean answers.

That strength also let the bank expand while the industry was still in triage. In 2010, UMB acquired certain assets and deposits of Prairie State Bank & Trust and assumed certain liabilities of the failed institution, widening its presence in key markets.

And then came the deal that pointed to what UMB was building next. On March 1, 2010, UMB completed its acquisition of Marquette Financial Companies of Minneapolis. Marquette—previously known as Marquette Savings Bank—was a federally chartered thrift with operations in banking, municipal lending, and asset-based lending. For UMB, it significantly expanded both geographic reach and, more importantly, healthcare banking capabilities.

That’s what’s notable about the Marquette move: it wasn’t a panicked grab for growth, and it wasn’t a government-assisted rescue. It was a deliberate purchase of specialization—capabilities UMB believed would matter for decades. The timing helped, of course. Post-crisis uncertainty and depressed valuations tend to concentrate minds on selling. But the logic wasn’t “cheap assets.” It was “the right capabilities.”

The payoff from all of this is hard to capture in a single metric, but it’s real. Crisis performance creates a reputational dividend—trust that compounds. After 2008, when clients and counterparties re-ranked their list of “safe hands,” UMB moved up.

And for investors, the crisis settled an important question. UMB’s conservatism wasn’t just a charming cultural artifact, or a trade-off that meant slightly less excitement in the boom years. It was a survival mechanism—one that preserved capital when others were destroying it, and created optionality when competitors had none.

The open question, as the economy healed and memories faded, was whether that discipline could persist—through growth, leadership transitions, and the next wave of temptation to reach for yield.

V. The Mariner Wealth Advisors Deal: Expanding the Ecosystem (2020)

By 2020, UMB had already proven two things: it could survive the moments that broke other banks, and it could build fee businesses that didn’t depend on taking more balance-sheet risk. But another shift was underway. Wealth management—helping high-net-worth individuals and families manage, grow, and protect their money—was consolidating fast. Independent RIAs were rolling up smaller firms, private equity was pouring into the category, and the winners increasingly looked like the ones with enough scale to invest in talent, technology, and a broader suite of services.

UMB responded with a move that fit its personality: meaningful, strategic, and deliberately not flashy. In 2020, UMB Financial Corporation took a strategic minority stake in Mariner Wealth Advisors, one of the largest and fastest-growing registered investment advisory firms in the U.S. It was UMB’s way of expanding into wealth management without trying to become a national RIA overnight.

The structure mattered as much as the headline. This wasn’t an acquisition. By taking a minority position, UMB got exposure to the growth of wealth management while sidestepping the biggest hazards of buying an entire firm—full integration risk, culture clashes, and the capital demands that come with a transformative purchase. The partnership let each side keep its own identity, while still creating pathways for referrals and deeper client relationships.

Mariner had built momentum through a mix of organic growth and acquisitions of independent advisory practices. The partnership gave Mariner access to banking products and services that could strengthen its client offering. And UMB gained something it couldn’t easily manufacture: a scaled wealth platform with established advisory capabilities and relationships.

The rationale was straightforward. UMB already served commercial businesses, fund managers, and affluent families—exactly the kinds of clients who often need sophisticated wealth planning. Instead of building everything from scratch, or betting the franchise on a big buyout, UMB could plug into a proven operator and make wealth management part of its broader value proposition.

Zoom out and you can see the ecosystem logic. A business owner might use UMB for commercial banking, rely on UMB Fund Services to run their investment fund, and turn to Mariner for personal wealth management. Each connection makes the next one more likely—and once a client’s financial life is spread across that many touchpoints, the relationship becomes harder to unwind. Switching costs stop being a feature of one product and start becoming a feature of the entire relationship.

The timing was also classic UMB. The deal happened in 2020, when COVID-19 was injecting uncertainty into markets and stress-testing every finance business model. But disruption has a way of accelerating long-term trends. Digital delivery mattered more. Operational scale mattered more. And UMB again showed a willingness to make a long-term bet in an unsettled moment—similar to how it used the post-2008 environment to position for what came next.

For investors, the Mariner investment sent a clear signal. UMB wasn’t content to be a traditional regional bank with a nice fee-income sidecar. It was deliberately assembling a diversified financial services mix—commercial banking, fund services, wealth management, payments—so growth wouldn’t have to come from any single lever, and so weakness in one area wouldn’t threaten the whole.

Of course, minority stakes come with their own trade-offs. You can’t force integration. Referrals don’t happen just because they look good on a slide. Incentives and culture have to line up, and part of the outcome depends on variables UMB can’t fully control—Mariner’s execution, industry competition, and whatever the market decides to do next. The bet was that the partnership would be strong enough to create real pull-through, even without full ownership.

VI. The Healthcare Banking Specialization: Domain Expertise as Moat (2010s–Present)

If you wanted to pick a banking vertical that could compound for decades, healthcare would be high on the list. Demographics keep demand marching upward. Regulation creates real barriers to entry. The cash flows are weird enough that generalist lenders routinely misread them. And once you’re embedded in a practice’s financial life—loans, treasury, payments, growth plans—switching becomes painful.

UMB saw that early and made healthcare a priority. Not with a single splashy announcement, but with something much more consistent with its culture: patient capability-building over years.

UMB Healthcare Services, a subsidiary of UMB Bank, focuses on financial services designed for the healthcare industry. That includes health savings accounts (HSAs), healthcare financing solutions, and specialized banking products for medical practices and healthcare organizations. Over time, UMB built a reputation as one of the leading healthcare-focused banking providers in the U.S.

The 2010 Marquette acquisition mattered here. It brought in capabilities and talent that helped UMB accelerate. But the real story is what happened after the deal closed: UMB kept investing and kept narrowing its understanding of how healthcare businesses actually work.

That meant learning the specific financing needs of medical practices—how revenue cycle timing differs by specialty, what it takes to finance medical equipment, how real estate fits into ambulatory surgery centers, and how working capital behaves inside dental service organizations (DSOs). Healthcare lending looks like commercial lending on the surface. In practice, it’s its own discipline.

This part is easy to underestimate until you’ve lived it. Healthcare revenue doesn’t behave like most commercial cash flows. A manufacturer ships a product and gets paid on standard terms. A medical practice bills an insurer and then deals with denials, appeals, and adjustments that can drag out for months. A generalist banker sees receivables aging and gets nervous. A specialist knows which claims are likely to pay, which represent real collection risk, and how that should change underwriting and structure.

UMB built teams around that reality. Its healthcare banking group includes professionals with deep healthcare finance experience, including people who’ve worked as healthcare administrators, revenue cycle specialists, and industry analysts. That expertise shows up in the details: how loans are structured, how covenants are calibrated, and how risk is assessed against the actual operating rhythms of a practice.

The hiring strategy was the point. UMB didn’t ask generalist commercial bankers to “pick up” healthcare through the occasional deal. It hired specialists who could speak the industry’s language—physician groups thinking about practice management, sponsors pursuing healthcare rollups, hospital finance leaders focused on capital planning. In a relationship business, being able to understand the client is often the difference between winning and being tolerated.

Over time, the healthcare banking division grew into a meaningful contributor within commercial banking. UMB expanded its healthcare lending capabilities across equipment financing, real estate loans for medical facilities, and lines of credit that support practice acquisitions and growth.

And once you get traction in a specialty vertical, the flywheel kicks in. Reputation drives inbound deal flow, not because you’re always the cheapest lender, but because you’re the lender that “gets it.” More deal flow builds more pattern recognition. That improves underwriting and speeds up execution. Better execution earns better economics and deeper relationships. Then the cycle repeats.

Dentistry—specifically DSOs—became a clear illustration of that playbook. The dental services industry has consolidated rapidly, with DSOs acquiring private practices at an accelerating pace. UMB positioned itself as a leading lender to DSOs, providing acquisition financing, working capital facilities, and other banking services that supported their growth strategies. As capital flowed into dental consolidation, operators needed banking partners who understood the acquisition model, the integration realities, and the regulatory specifics of dental care. UMB aimed to be that partner—early, consistently, and at scale.

For investors, this is niche dominance in its most bank-friendly form. The know-how is hard to replicate quickly because it’s built through years of reps and specialized talent. The relationships are sticky because healthcare operators don’t casually swap out a bank that truly understands their cash flows and risk profile. And the market itself is large, growing, and continuously generating financing needs as healthcare spending rises and consolidation continues.

VII. Technology Transformation: The Digital Banking Rebuild (2015–Present)

At most regional banks, the technology story is a slow-moving tragedy. Decades of acquisitions leave behind a patchwork of core systems. Everyone knows modernization is necessary. Almost no one wants to touch it. So banks bolt shiny new digital features onto aging infrastructure, “buying time” while the technical debt quietly piles up—until the whole stack becomes harder to change than to live with.

UMB took the harder route. And it’s one of the clearest examples of how its long-term mindset shows up in practice.

Over the past decade, UMB made significant technology investments because it saw digital capability as table stakes, not a nice-to-have. That meant a multi-year transformation: upgrading core banking systems, improving digital customer interfaces, and building stronger data and analytics capabilities. It was expensive and disruptive by nature—but the goal was simple. Run the bank more efficiently, serve customers better, and create a platform that could support new products without duct tape.

Core banking replacements are about as unforgiving as projects get. The core is where every transaction runs, every account balance lives, and every downstream system connects. Swapping it out while the bank stays open is often compared to changing an airplane engine mid-flight. Even that metaphor doesn’t quite do it justice, because in banking the “engine” touches everything, all the time, with regulators and customers watching.

The pressure to modernize has only increased as legacy platforms became harder to maintain, harder to secure, and slower to update. Modern cores—often cloud-based—can be more flexible and scalable, with a better cost structure over time. But the migration risk is real. Plenty of banks start core conversions and then retreat: costs balloon, timelines slip, or the operational risk gets too scary.

So why could UMB do what many peers wouldn’t?

First, governance and time horizon. A core conversion can compress profitability for years, and at many public banks that’s a great way for a CEO to get fired. UMB’s family stewardship made it easier to tolerate short-term pain for long-term capability. Second, balance sheet conservatism. A bank that hasn’t been stretched by risk-taking has more room to invest. Third, proof from inside the company: UMB’s fund services business already relied on sophisticated systems and had shown what modern infrastructure could enable.

That fund services capability also pushed UMB to invest in proprietary platforms—technology that supports complex accounting, reporting, and compliance requirements. Those systems weren’t just “IT projects.” They were competitive weapons, helping UMB hold its own against much larger custodian banks and increasingly capable fintech specialists.

UMB’s tech strategy also wasn’t purely build-everything-yourself. It leaned on a disciplined framework: build, buy, or partner depending on what the capability actually meant. For core infrastructure—things that define the customer experience and the bank’s ability to execute—UMB invested in owned or deeply integrated solutions. For narrower, specialized needs—certain payment features, specific compliance tooling—partnering could deliver best-in-class capabilities without surrendering the customer relationship.

Payments are where this becomes especially visible. For commercial clients, moving money quickly and cleanly isn’t a perk. It’s the job. Real-time payments have become a key capability, especially as businesses come to expect faster settlement and more immediate cash visibility. The FedNow Service, launched in 2023, added a new real-time rail through the Federal Reserve system, and banks that can support instant payments gain an edge in treasury management.

UMB positioned itself as an early adopter of real-time payment infrastructure because it fits the company’s broader posture: compete on reliability, service quality, and operational excellence—not on being the cheapest provider in the market.

Treasury and payments infrastructure is also one of the strongest forms of lock-in a bank can create. When a client’s cash management workflows, payment files, approvals, and reporting are deeply integrated into how they operate, switching banks stops being an annoyance and starts being a project with real business risk. That’s switching cost in its most practical form: not contractual, but operational.

And then there’s the compounding effect. Modern platforms can handle growth without hiring in lockstep. Automation cuts the manual work that consumes staff time and creates errors. Better data and analytics improve risk management and make service more responsive. Done right, technology doesn’t just make the bank look modern—it creates operating leverage, where the business can grow faster than its cost base.

For investors, the only technology story that matters is whether it shows up in outcomes: better efficiency, stronger customer retention, and the ability to keep pace with competitors without permanently sacrificing profitability. The evidence at UMB has suggested progress—but there’s no finish line here. The more durable advantage isn’t any single system upgrade. It’s whether the organization can sustain a culture of continuous improvement long after the “transformation” slide deck disappears.

VIII. The Regional Banking Crisis and UMB's Immunity (2023)

On March 8, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank announced a $1.8 billion loss on its securities portfolio and said it planned to raise more capital. Within 48 hours, the bank was gone. Customers pulled $42 billion in a single day, regulators seized the institution, and the second-largest bank failure in American history was complete. Signature Bank followed within days. First Republic staggered on for weeks before collapsing in May.

It was a stress test most people didn’t think the system could still fail. After 2008, the story went like this: regulation made banks safer, deposit insurance and Federal Reserve backstops would stop runs, and digital banking would make customers more “sticky.” In March 2023, those assumptions didn’t so much collapse as reveal their missing footnote: everything works—until confidence breaks, and withdrawal speed becomes measured in taps, not days.

The regional banking crisis hit so hard because the failures shared a few brutally modern traits: deposit bases that were too concentrated, large unrealized losses on securities as interest rates rose, and withdrawals that could cascade instantly through online banking and social networks.

Silicon Valley Bank was the cleanest example. Its deposits were overwhelmingly tied to the venture ecosystem—startups, VC firms, and employees who all talked to one another. Those deposits were invested in long-duration securities that fell in value as rates climbed. And the bank had no meaningful hedging against interest-rate risk. Once concerns surfaced, the panic didn’t spread through branches. It spread through group chats. The run was over in hours.

UMB Financial Corporation was relatively unaffected. Analysts pointed to a diversified deposit base, conservative asset-liability management, and strong liquidity. Deposits held steady during the worst of the stress, and the stock proved more resilient than many regional bank peers.

Why didn’t this wave hit UMB the same way? Not because it predicted SVB’s specific failure, and not because it got rescued. It was because UMB’s playbook—built over decades—was almost perfectly designed for a moment when the banking business reverted to its oldest rule: trust is the product.

Start with deposits. UMB didn’t depend on one tight-knit, high-velocity customer segment. Its deposits came from commercial clients across industries, fund services relationships, personal banking customers, and institutional accounts. That mix matters. When fear hits, concentration becomes a transmission mechanism. Diversification becomes a circuit breaker. And in 2023, the flight to quality actually flowed UMB’s direction as depositors looked for institutions they believed would still be standing tomorrow.

Then there’s asset-liability management. UMB didn’t load up on the kind of concentrated duration exposure that turns rising rates into a balance-sheet headline. Its securities portfolio was positioned more conservatively, and interest-rate hedging was in place. The same boring balance sheet that might have looked like it was leaving money on the table when yields were low proved its worth when rates moved fast.

Finally, there was the reputational buffer. UMB’s commercial and fund services clients weren’t meeting the bank for the first time in a crisis. They’d lived through cycles with it and understood the culture. That familiarity doesn’t eliminate fear, but it slows the stampede—especially compared to institutions where customers were essentially there for a specific ecosystem, a specific rate, or a specific moment in time.

After the dust settled, regulators proposed stricter capital and liquidity requirements for regional banks. Depositors, newly sensitized, moved money toward institutions perceived as “too big to fail.” The crisis also reignited consolidation talk and sharpened a question that’s been hovering over the industry for years: what does the future look like for mid-sized banks in a world where runs can be instant and regulation keeps rising?

For UMB, the episode was another reputational win. Stability became a sales asset. Commercial clients and institutional counterparties didn’t just want services—they wanted a banking relationship that had demonstrated it could take a punch.

And as in past downturns, turbulence created opportunity. When banks come under pressure, talent looks for safer platforms. Customers look for new homes. UMB was positioned to benefit from both—not as a lucky bystander, but as the kind of institution that had spent a century building optionality for moments like this.

For investors, 2023 reinforced the central point about UMB: conservative culture creates compounding value, but you don’t always see it in the good years. You see it when the system gets stressed and the difference between “good enough” risk management and institutional discipline becomes existential. The open question is the same one that keeps returning in UMB’s story: can that discipline hold—through growth, competition, and generational change—without getting diluted?

IX. Modern UMB: The Four-Pillar Strategy (2020s–Today)

To understand UMB today, it helps to stop thinking about it as a regional bank with a few add-ons. The more accurate picture is an ecosystem: multiple businesses that feed one another, deepen relationships, and diversify the company away from relying on any single source of earnings.

At the corporate level, UMB Financial Corporation reports three business segments: Commercial Banking, Institutional Banking, and Personal Banking. Commercial Banking covers lending, deposits, and treasury management for business clients. Institutional Banking houses fund services, asset management, and healthcare services. Personal Banking includes consumer deposits, residential lending, and private wealth management. Those are the reporting lines. The strategy underneath them is the real story.

Commercial Banking is still the foundation. It’s the relationship engine that connects UMB to the businesses that form the core of its customer base. But UMB has tried to avoid competing purely on price by leaning into verticals where expertise actually matters—healthcare, institutional clients, transportation—areas where a banker who understands the operating model can structure better deals, move faster, and earn better economics. Treasury management is the glue here. When UMB is running a client’s cash management workflows, approvals, and reporting, the relationship becomes much more than a loan. It becomes operational infrastructure—and that creates real switching costs.

Fund Services, inside Institutional Banking, has become big enough that it would be a meaningful standalone company. This is the fee engine: fund administration, custody, and related services that generate significant non-interest income. The client base spans mutual funds, ETFs, private equity funds, and hedge funds, with particular strength in alternatives. Over the past decade, assets under administration have grown substantially, powered by a mix of organic wins and the broader expansion of alternative investments. UMB has held its place as one of the largest independent, non-custodian bank fund administrators in the U.S.—a niche where scale, process, and trust matter more than branch count.

Healthcare Services is a two-part story: the specialized healthcare banking effort we covered earlier, and the HSA administration business. The banking side focuses on lending and financial services tailored to medical practices and healthcare organizations. The services side includes administering health savings accounts—an area that has grown into a larger contributor to fee income as HSAs have become more common. It’s a good example of UMB’s broader pattern: find a category where complexity and regulation create friction, then build the capabilities to operate there with consistency.

Payments and treasury management cut across everything. For commercial and institutional clients, payments are not a feature—they’re a daily dependency. UMB’s investments in modern treasury platforms and real-time payments infrastructure are designed to make it easier for clients to integrate UMB into their operations. And as payment speed and systems integration become bigger differentiators, that capability becomes another way the bank can win relationships and keep them.

Geographically, UMB has expanded well beyond Kansas City, with banking operations across eight states in the Midwest, Mountain West, and Southwest. It’s been selective rather than sprawling—adding presence where it can serve existing clients with multi-state operations or where its specialty capabilities travel well. The goal hasn’t been to “paint the map.” It’s been to grow in places where UMB can plausibly offer something better than a generalist regional bank.

That discipline shows up in the company’s posture on growth more broadly. Management has consistently emphasized profitable growth over fast growth—fewer big leaps, more repeatable execution in businesses where UMB believes it has an advantage.

Then there’s leadership. Mariner Kemper, a member of the founding Kemper family, has served as Chairman and CEO of UMB Financial Corporation, continuing multi-generation family involvement in the bank. Under his tenure, UMB has maintained its conservative risk culture while pushing further into fee-based businesses like fund services and healthcare services.

That continuity is both a strength and a question mark. The Kemper influence has historically reinforced long-term thinking and a willingness to say no. But every family-controlled institution eventually has to prove that the culture outlives any one person—or even any one generation. Succession, governance, and cultural drift are not abstract risks; they’re the natural gravity of time.

Financially, UMB has typically performed in the top tier of regional banks, with returns on equity often ahead of peer averages. And as technology investments have started to translate into productivity, the company’s efficiency ratio has improved—an early sign of operating leverage from the rebuild we discussed.

For investors, this “four-pillar” idea—commercial banking, fund services, healthcare services, and payments/treasury—creates two benefits at once. Diversification: different businesses respond to different cycles. And synergy: each relationship can lead to another, and the more touchpoints UMB has with a client, the harder it is to displace. The open question is the tension at the heart of UMB’s identity: can an institution built to protect the franchise through discipline also compound fast enough in a more competitive, higher-expectation era for regional banks?

X. Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Put UMB into Porter’s Five Forces, and a pattern jumps out: this is a bank that has tried to compete where the rules of the game are winnable. Not because competition disappears, but because the forces are more containable when you pick the right battlegrounds.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Banking is heavily regulated, and regulation is a moat. Getting a charter means winning regulatory approval, showing you have experienced management, and putting up real capital. Then you still have to build the unglamorous machinery—technology, compliance, risk management, operations—that takes years to assemble. True de novo entrants are rare, and most “new” banks are really acquisitions wearing a fresh coat of paint.

Fund services raises the bar even higher. This is a business that has consolidated because small providers struggle to keep up with the cost of technology and the ever-tightening compliance burden. On top of that, it’s relationship-driven: fund managers want a partner with a track record, not a promise. It’s hard to break in when trust and operational proof matter as much as features.

Fintech is the wildcard—but it’s not a simple “fintech eats banks” story. Consumer banking and some parts of payments have been disrupted. The B2B world UMB plays in—commercial banking relationships, complex fund administration, regulated institutional workflows—has been slower to flip. The barriers here aren’t just software. They’re risk management, credibility, and the ability to operate under regulatory scrutiny without breaking.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

For banks, the main “suppliers” are depositors. Deposits are competitive, but UMB’s funding base is diversified enough that no single depositor group can dictate terms.

Vendors matter too. Core systems, payment rails, security tooling—technology providers can have leverage, especially when switching costs are high. But the market for most banking technology is competitive, which limits how much pricing power any one vendor can sustainably hold.

The tightest constraint is talent. Specialized expertise—especially in fund services and healthcare banking—is scarce. That’s where UMB’s culture and reputation become a practical advantage: they help attract and retain people who want stability, process discipline, and long-term relationships instead of constant reinvention.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

In commercial banking, buyers have options. Sophisticated borrowers can shop terms, and “plain vanilla” lending is often priced like a commodity.

UMB tries to blunt that pressure by not being a generalist everywhere. If a client needs healthcare-specific knowledge or institutional-grade fund services, the field narrows. Add in treasury management—where UMB can become embedded in how a business moves money, approves payments, and sees cash—and switching becomes less about rate shopping and more about operational disruption.

That’s the heart of the relationship model: clients don’t only buy money. They buy reliability, speed of execution, and judgment when things get messy.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

Substitutes for traditional bank lending have real momentum. Direct lending funds, private credit, and other non-bank platforms compete for commercial borrowers and can move quickly, sometimes with fewer constraints than regulated banks.

But substitutes often can’t replicate the full relationship bundle. They can provide credit, but they typically can’t provide the same combination of deposits, treasury management, payments infrastructure, and ongoing banking services that tie a client’s daily operations to the institution.

In fund services, substitutes exist but are narrower. A large asset manager can bring administration in-house, but that means building specialized teams and absorbing technology and compliance costs. Some technology platforms can automate slices of administration, but complex alternatives still demand expertise—especially around valuation and regulatory reporting—where humans remain part of the product.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH but Segmented

Rivalry in banking is brutal for the commodity stuff: basic deposits, standard commercial loans, anything where differentiation collapses into price.

UMB’s approach has been to lean into segments where differentiation is more real. In alternatives-focused fund services, the competitive set is smaller and more specialized. In healthcare banking, industry knowledge and relationship depth can matter more than a marginal pricing difference. In treasury management, integration and service quality can outweigh the lowest bid—because what clients really want is fewer errors and fewer surprises.

The takeaway from Porter is straightforward: UMB has tried to avoid fighting on every front. It has chosen where to compete—and just as importantly, where not to. That focus is the strategy. It’s an admission that you can’t be the low-cost provider, the technology leader, and the premium relationship bank all at once, so you’d better pick a lane and build advantages that actually compound.

XI. Strategic Analysis: Hamilton's Seven Powers

Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers is a useful lens here because it forces a hard question: what, exactly, makes UMB difficult to compete with over time? Not “good.” Not “well run.” Durable.

Applied to UMB, the answer is: real power exists—but it’s concentrated in specific parts of the business, especially fund services. This isn’t a company with a single, overwhelming superpower. It’s a company that has stacked several quieter advantages in the niches it chose to play in.

1. Scale Economies: STRONG in Fund Services

In fund administration, scale matters in a very bank-like way: the biggest costs are fixed. Regulatory compliance, technology infrastructure, specialized operations teams—once you’ve built the machinery, every additional client rides on top of it at a lower incremental cost.

That’s why UMB’s fund services business benefits from classic scale economies. The platforms, controls, and talent base are largely fixed investments that can support more funds and more complexity over time. And as the client base grows, the economics improve, which funds further investment. The loop reinforces itself: scale enables investment, investment improves capability, capability attracts clients, and those clients add scale.

Traditional banking has some scale benefits too, but they’re less structural. Taking deposits and making loans doesn’t compound cost advantage the way a services-and-technology-heavy operation can.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

UMB doesn’t have the clean, mathematical network effects of a consumer platform where every new user directly increases value for all other users.

But there are softer network dynamics. In fund services, being known as a provider that can handle complex alternative structures tends to attract more alternative managers. That cluster deepens expertise, makes delivery better, and strengthens reputation—which attracts the next wave of clients. In commercial banking, industry clusters (healthcare is the obvious example) create referral gravity: advisors, operators, and management teams tend to circulate within a relatively tight ecosystem.

These aren’t Visa-style network effects, but they do create reinforcing feedback loops.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE-STRONG

UMB’s posture has long been different from the dominant banking playbook, especially in the years leading up to 2008. While many larger banks leaned into transaction volume, yield chasing, and complexity, UMB leaned into relationship banking, specialization, and conservative risk.

That was real counter-positioning in the 2000s. It could look like underperformance in boom times—until the boom ended, and the same “restraint” turned into survival and trust.

The lingering question is whether this remains as distinctive going forward. If the industry has truly internalized the lesson and moved toward more conservative behavior, UMB’s differentiation shrinks. If it hasn’t—as history suggests it often hasn’t—then UMB’s cultural default still functions as strategic separation.

4. Switching Costs: STRONG in Fund Services, MODERATE in Banking

Switching costs are where UMB’s fund services business starts to look like a fortress.

A fund administrator isn’t a vendor you casually rotate. They handle fund accounting, NAV calculation, investor reporting, regulatory compliance, and the operational plumbing that makes the fund run day to day. Over time, the administrator becomes deeply integrated with a manager’s systems and workflows. Changing administrators means migrating data, rebuilding integrations, retraining staff, and accepting real operational risk during the cutover. Most managers only make that move when service is unacceptable or their needs change dramatically.

In traditional banking, switching is easier—but not frictionless. A commercial client can move loans and deposits with work, but it’s doable. Where switching costs spike is treasury management: once a company has integrated payment workflows, approvals, reporting, and cash visibility into a bank’s platform, switching becomes a project, not a decision. That creates meaningful stickiness, even if it’s not as absolute as fund administration.

5. Branding: MODERATE

UMB isn’t a household name, and it doesn’t need to be. Its brand operates where it matters: among commercial clients, fund managers, and healthcare operators who care less about advertising and more about whether the institution is dependable.

The reputation for conservative management, resilience through crises, and relationship-oriented execution creates a trust premium. In financial services, that trust can translate into retention, referrals, and occasionally pricing power—because clients aren’t just buying a product, they’re buying confidence that the provider won’t disappear at the wrong moment.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK-MODERATE

UMB’s closest thing to a cornered resource is governance and culture—specifically, Kemper family stewardship enabling long-term thinking and consistency in risk posture.

It’s not an uncopyable asset in the way a patent might be, and it’s not immune to drift. But it is relatively rare in public banking, where quarterly incentives can push decision-making toward short-term optimization.

Specialized talent in fund services and healthcare is also a quasi-cornered resource—valuable, but ultimately mobile.

7. Process Power: STRONG

Process power is the most “UMB” advantage of all: the accumulated routines, judgment, and operational muscle memory that make the institution run better than a competitor can replicate quickly.

Decades of fund administration experience, ingrained underwriting discipline, specialized healthcare pattern recognition, and client service execution add up to real institutional capability. A competitor might hire individuals, but copying the system—the way work gets done, the way risk gets evaluated, the way exceptions get handled—takes years of repetition and refinement.

That’s process power: it’s embedded, cultural, and hard to buy.

Overall Assessment: UMB’s competitive power comes primarily from switching costs + process power + scale economies (in fund services), with counter-positioning and branding as meaningful reinforcements. It’s not the kind of dominance you see in a category-defining tech platform—but within UMB’s chosen niches, it’s enough power to protect above-normal returns for a long time.

XII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The UMB story isn’t just a banking case study. It’s a set of principles about how to build an enduring business in a competitive, temptation-filled industry—where one bad decision can wipe out a decade of progress.

The Power of Strategic Restraint

What you don’t do can matter as much as what you do. UMB’s most important decisions were often refusals: staying away from subprime lending, excessive leverage, and financial engineering dressed up as innovation. In the moment, saying no can look like leaving money on the table. Later, when the cycle turns, it looks like the thing that kept you alive—and kept your competitors from eating your lunch while they were busy repairing their balance sheets.

Niche Dominance Over Broad Mediocrity

UMB could have tried to become everything to everyone and fight money-center banks on their terms. Instead, it picked arenas where focus and operational excellence actually win: fund services, healthcare, and targeted commercial segments. That choice didn’t just create growth. It created stickier customers, more defensible economics, and a clearer reason to exist than “we also offer loans.”

Culture as Competitive Advantage

The Kemper family’s conservative philosophy wasn’t a slogan. Over time, it became an institutional asset—a way of making decisions, hiring people, and managing risk that’s hard for competitors to copy quickly, even if they want to. Culture is slow to build, fragile once you have it, and incredibly valuable when it consistently steers you away from mistakes other firms keep repeating. For investors, it’s also one of the hardest things to evaluate from the outside—and one of the most predictive.

The Compounding Value of Boring

Consistency wins. Over decades, steady returns beat flashy returns that come with periodic disasters. A business that compounds at solid returns year after year will often outperform one that alternates between boom-time heroics and bust-time survival. The deeper point isn’t the exact number—it’s that avoiding catastrophic drawdowns preserves the ability to keep investing, keep hiring, and keep earning trust when others are forced into retreat.

Specialization as Moat-Building

In banking, specialization is underrated because money looks interchangeable. But industry knowledge isn’t. Deep expertise in healthcare finance or complex fund administration creates real defensibility: better underwriting, better service, better referrals, and processes that don’t travel easily to a generalist competitor. For many businesses, the path to durable advantage isn’t being broadly good—it’s being exceptionally good in a place that rewards expertise.

Technology as Offense, Not Just Defense

UMB’s willingness to take on a core banking overhaul—expensive, disruptive, and operationally risky—reflects a mindset most banks struggle to adopt: technology isn’t just a cost of staying relevant. Done right, it’s a growth enabler. Modern platforms can create operating leverage, improve service, and make it easier to launch and support new products without piling on complexity.

Managing Cyclicality Through Diversification

UMB didn’t bet the franchise on a single earnings engine. By building fee-based businesses like fund services and HSA administration alongside traditional lending, it created ballast. When credit demand weakens or spreads compress, fee income can keep the machine steady. This is portfolio construction at the company level: build counterweights so one cycle doesn’t dictate your fate.

Capital Allocation Discipline

UMB’s dealmaking pattern tells you how it thinks: act when others are constrained, and stay patient when prices are rich. The Marquette acquisition during the post-2008 period and the Mariner partnership during the uncertainty of 2020 both reflect that mindset—willingness to move when the environment is unsettled, paired with restraint when “easy growth” is being bid up. In the long run, capital allocation may be the highest-leverage skill in leadership, because it determines what your business becomes.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The bull case for UMB is really a story about compounding—multiple businesses reinforcing one another, and a risk culture that keeps the whole machine intact when the cycle turns.

First, fund services still looks like the cleanest runway. Alternative investments—private equity, hedge funds, real assets—keep growing, and as those structures get more complex, the operational burden doesn’t go down. It goes up. That complexity is exactly what creates demand for a sophisticated, trusted administrator, and it’s where UMB has deliberately built depth.

Second, healthcare banking is positioned behind tailwinds that don’t depend on perfect macro timing. An aging population pushes demand higher over decades. Consolidation in medical practices continues. Financing needs don’t disappear; they evolve. In a vertical where expertise and relationships matter, UMB’s advantage can compound the way specialist franchises do: each deal builds pattern recognition, each relationship drives referrals, and over time “we do healthcare” becomes “we’re who you call.”

Third, consolidation in regional banking can create opportunity for the banks that don’t get shaken out. When competitors are forced to sell, shrink, or merge, the survivors inherit customers, talent, and share—often without having to take heroic risk. UMB’s crisis performance has repeatedly positioned it to be one of those survivors, and potentially a buyer when the timing is right.

Fourth, the technology rebuild has the potential to translate into operating leverage. Modernizing core systems and digital capabilities is painful upfront, but the payoff is simple: the ability to grow without adding costs in lockstep. If that continues to show up in productivity and efficiency, it becomes an underappreciated earnings driver.

Fifth, there’s a valuation argument. Banks with durable fee income, strong risk management, and a history of surviving stress tend to earn premium valuations—when the market believes the quality is real. If investors continue to re-rate “boring but safe” higher after 2023, UMB could benefit not just from earnings growth, but from the multiple it trades at.

Bear Case

The bear case starts with the reality that regional banking is a harder business than it used to be. Regulation keeps rising, technology expectations keep rising, and interest rates can expose balance-sheet mistakes quickly. After 2023, additional regulatory costs could weigh most heavily on mid-sized banks—big enough to be scrutinized, not big enough to spread the burden as easily as the giants.

Fund services also won’t stay a quiet niche forever. Large custodian banks are investing aggressively in alternatives. Meanwhile, technology platforms are automating parts of administration that used to require expensive human work. Even if UMB keeps winning business, pricing pressure could intensify and squeeze margins.

Geography is another risk. UMB has expanded, but it still has meaningful exposure to Kansas City and the broader Midwest. If that regional economy weakens, credit quality and growth could feel it more than a truly national bank would.

Succession is a softer but important variable. The Kemper family influence has been central to UMB’s discipline and identity. Any generational transition raises the possibility—subtle or sharp—of cultural drift. In banking, culture isn’t window dressing; it’s a risk system. If it changes, outcomes can change with it.

And even with smart investment, scale matters in technology. Money center banks can spend more and spread that spend over a much larger base. UMB can compete, but it has to choose its battles—and there will be areas where it simply can’t match the breadth of the largest players.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking UMB going forward, three KPIs are especially telling:

-

Fund Services Assets Under Administration Growth — This is the clearest read on whether the alternatives bet is still working. Strong, sustained growth suggests UMB is winning share and riding category expansion. A sustained slowdown can be an early sign of competitive pressure or maturation.

-

Efficiency Ratio Trend — This is where the technology story becomes real. If modernization is creating operating leverage, the efficiency ratio should improve over time. If it stalls or reverses, it suggests cost inflation and competitive investment needs are eating the gains.

-

Net Interest Margin Relative to Peers — Fee income matters, but UMB is still a bank. NIM versus peers is a practical scorecard for balance-sheet management—whether conservatism is protecting the franchise without chronically sacrificing earning power. Consistent relative strength, especially through rate volatility, would reinforce the core UMB claim: discipline isn’t just safer, it’s strategically smarter.

XIV. Epilogue: What's Next for UMB?

One of the most intriguing “next moves” for UMB sits right at the intersection of its most unusual asset and the broader direction of finance: embedded services. Through fund services, UMB already works with some of the most sophisticated investment managers in the industry. And those clients increasingly don’t want a menu of disconnected vendors. They want fewer partners who can handle more of the stack—administration, custody, reporting, data, and the banking rails that sit underneath it all. Whether UMB can turn those relationships into a broader ecosystem play is still unproven. But the option is there, and it’s a natural extension of what UMB has spent decades building: trust plus operational integration.

Geographic expansion is the more classic regional-bank question—and the tradeoff is real. Expand faster, and you can pick up growth, diversify the balance sheet, and follow clients as they spread across states. But the faster you expand, the harder it gets to preserve the thing UMB actually competes on: relationship culture and disciplined underwriting. Expand too slowly, and you protect the culture, but you may leave opportunities on the table as competitors consolidate and customers re-evaluate where they want to bank. If UMB’s history is any guide, it will keep choosing the deliberate path. The unknown is whether the market will let “deliberate” be fast enough.

The wealth management buildout via the Mariner partnership is also still early. The logic is obvious on paper: referrals, fuller-wallet relationships, and a more complete financial-services offering for business owners and affluent clients. But minority stakes don’t produce synergy automatically. This only becomes a true growth driver if the relationship turns into repeatable execution—real cross-referrals, product collaboration, and a client experience that feels integrated instead of adjacent.

Then there’s AI, which has the potential to reshape banking in a way that’s both mundane and profound. Not in the sci-fi sense, but in the “who runs operations better” sense. Credit underwriting, fraud detection, customer service, compliance workflows—these are all areas where AI can compress cost, speed up decisions, and reduce errors. Banks that deploy it well can gain meaningful advantages. Banks that lag may find their cost structures and service levels drifting out of range.

UMB has pointed to interest in using AI, especially to improve customer service and operational efficiency. And the fit is especially strong in fund services, where the work is data-heavy, compliance-intensive, and operationally complex. If AI can improve automation and analytics there without sacrificing control, it could strengthen the very engine that already differentiates UMB.

The most uncertain variable, though, is the most human one: succession and governance. Kemper family involvement has been central to UMB’s identity and risk posture for generations. Whether that culture holds as family involvement evolves isn’t something you can model cleanly. It’s something institutions either manage successfully—or slowly lose without noticing until the first big mistake arrives.

Finally, industry consolidation is still hanging over everything. UMB could use its strength to buy weaker competitors when the timing is right. It could be pressured, eventually, to sell to a larger institution looking for a foothold. Or it could remain what it has long preferred to be: independent, selective, and built to survive cycles others don’t. The company’s posture has historically leaned toward independence, but banking has a way of forcing choices when economics and regulation shift.

If there’s one enduring lesson in UMB’s story, it’s that boring, disciplined, specialized banking isn’t a lack of ambition. It’s a strategy—one that the industry periodically rediscovers the hard way. 2008 was one reminder. 2023 was another. The next crisis, whenever it comes, will either validate the same model again or expose the limits of it.

What’s clear is that UMB enters its next chapter with a rare combination: real fee-based capabilities, a conservative balance sheet, and a culture that has historically treated risk management as identity, not optics. Whether those advantages compound into the next decade will depend on execution, competitive intensity, and, above all, whether UMB can preserve the discipline that made it different in the first place.

XV. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—past the headline numbers and into the machinery that shaped UMB—these are the best places to start:

UMB Financial Corp. Annual Reports (last 5 years) — The chairman’s letters are where the strategy actually shows up: what management is optimizing for, what it refuses to chase, and how it thinks about risk when it isn’t forced to.

"The Kemper Legacy: 100 Years of Banking" (Company History) — A company-authored history that fills in the human context behind the culture: family governance, formative decisions, and why “conservative” became a feature, not a constraint.

Kansas City Fed Research on Regional Banking — Useful grounding on the Midwest banking environment, regulatory realities, and how regional banks fit into the broader economy.

Fund Services Industry Reports (Coalition Greenwich, Fitch) — A clearer picture of the competitive landscape in fund administration: who the major players are, what’s driving growth, and where the pressure points are.

American Banker’s Regional Bank Rankings — A quick way to see how UMB stacks up against peers, and how “performance” looks when you compare strategies across the same cycle.

Harvard Business Review: "The Discipline of Business Strategy" — A great framework for understanding UMB’s defining trait: focus, tradeoffs, and the compounding advantage of knowing what you won’t do.

"The House of Morgan" by Ron Chernow — Not about UMB, but essential for understanding the deeper tradition UMB fits into: relationship banking, reputation, and trust as the real balance sheet.

BIS Papers on Banking Regulation Post-2008 — For the policy layer: how regulation changed after the crisis, and why that shift matters for the economics of mid-sized banks.

UMB Investor Days and Conference Presentations — The most direct window into how management explains the business, what it’s prioritizing, and how it frames opportunities like fund services and healthcare.

Federal Reserve Financial Stability Reports — A broader view of the risks that periodically reprice the entire banking system—and the backdrop for why UMB’s “boring” choices can end up being the most valuable.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music