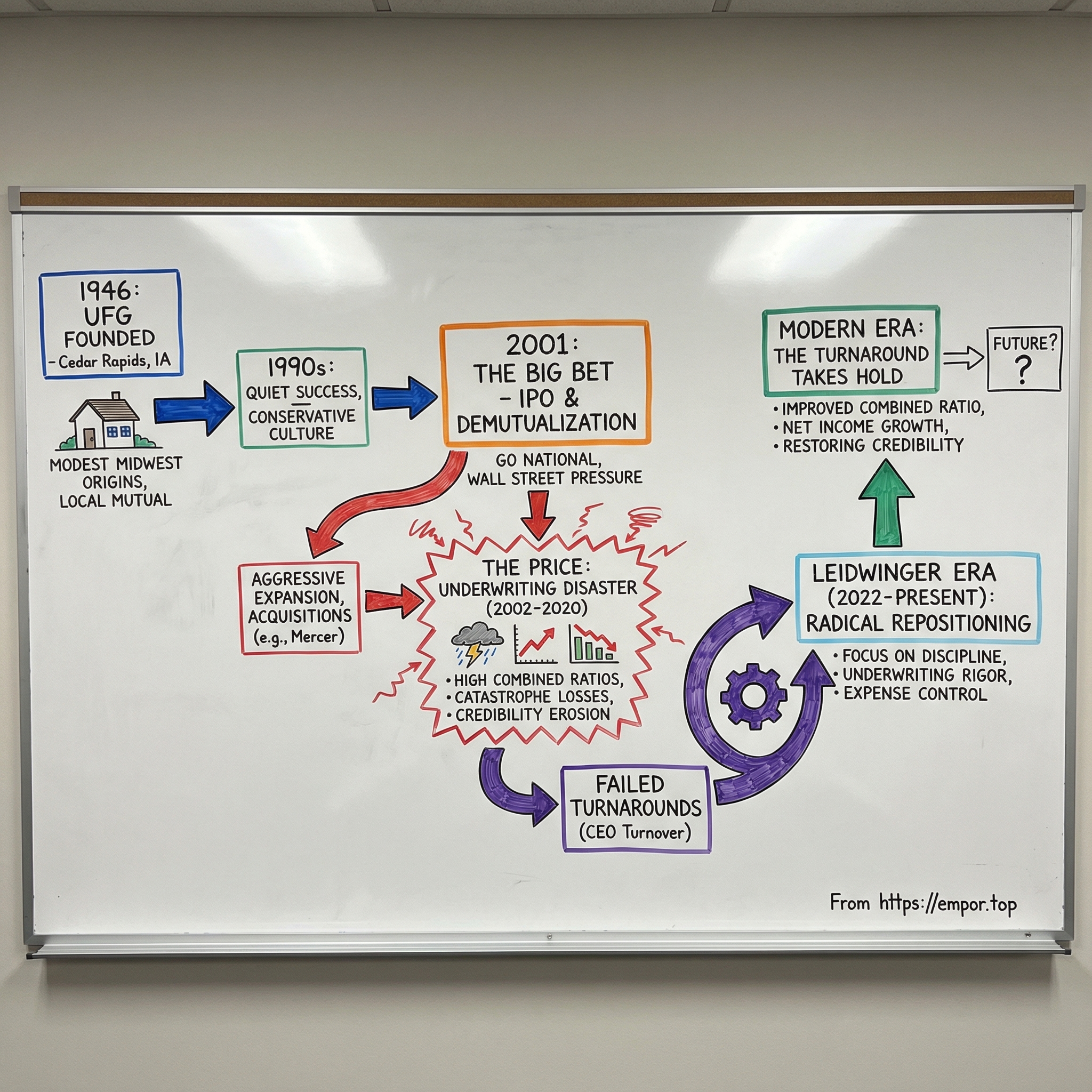

United Fire Group: The Midwest Mutual That Went National (and Paid the Price)

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture Cedar Rapids, Iowa, on a bitter January morning in 1946. In a modest two-story house near downtown, a small group of insurance men opens the doors of a new company. They call it United Casualty Company. The product is simple—auto and liability coverage. The ambition is even simpler: serve Iowa customers with fair, dependable insurance from people who actually understand their world.

That’s the origin story. No grand strategy decks. No “nationwide footprint.” Just a local insurer built for local risks.

Fast forward nearly eight decades and the contrast is striking. That house in Cedar Rapids becomes the headquarters city for United Fire Group, a publicly traded property-and-casualty insurer listed on NASDAQ. UFG is licensed across all 50 states plus D.C., distributes through roughly 1,000 independent agencies, and writes more than a billion dollars a year in premiums. Somewhere along the way, the company didn’t just grow—it changed shape.

And that shape-shift is the whole story.

UFG’s arc has all the classic beats: a conservative, community-rooted insurer; a push to go bigger and broader; years where growth looked like genius—until it didn’t. It went from regional stalwart to national aspirant, from serial acquirer to a company forced into painful retrenchment. And now, after years of bruising results, it’s trying to complete the hardest kind of comeback: the slow, technical, credibility-rebuilding turnaround that insurance demands.

The central tension here is one that shows up across American business: what happens when a company built to serve a community starts optimizing for Wall Street? In insurance, the consequences are amplified because the feedback loop is brutally delayed. When a manufacturer cuts corners, defects show up on the assembly line. When an insurer underprices risk, the mistake can sit quietly for years—hidden in reserves, disguised by assumptions, and temporarily covered up by a few lucky catastrophe seasons. Then the bill comes due. And when it comes, it tends to arrive all at once.

So this is a story about incentives, geography, discipline, and time. It’s about what happens when a company tries to be something it isn’t—and what it takes to become itself again. Because in the end, UFG’s fate hinges on one deceptively simple question: can leadership sustain the rarest discipline in insurance—the willingness to say “no” to business that doesn’t clear the underwriting bar?

For investors, UFG is also a living case study in what Warren Buffett loves about the industry and what he warns about in the same breath: the long tail. In insurance, you can look smart for a long time—right up until you aren’t. And the scoreboard is unforgiving. Keep the combined ratio under 100% and you’re compounding value. Let it stay above 100% and you’re destroying capital one policy at a time.

II. Founding Context & The Mutual Era (1946–1990s)

To understand why United Fire Group worked for so long, you have to remember what the American insurance business looked like in the middle of the 20th century. It wasn’t a handful of national giants blanketing the country with the same product. It was regional by design—built around local economies, local weather, and local judgment.

United Fire & Casualty Company was founded in 1946 in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Over time, through its insurance company subsidiaries, it operated as a property-and-casualty insurer, and it also wrote life insurance and sold annuities. But in those early decades, the company’s edge wasn’t product breadth. It was proximity.

The founders understood a truth that doesn’t show up on a spreadsheet: insurance is intensely local. The risks facing a corn farmer in Iowa aren’t the same as a textile mill in Massachusetts or an oil field in West Texas. You can’t price all of that from a distant headquarters and expect the numbers to behave.

This idea—that geographic concentration creates underwriting expertise—became the foundation of UFG’s early success. Its agents weren’t just selling policies; they were embedded in the communities they served. They knew who ran a tight operation and who cut corners. They knew which businesses took safety seriously, which ones didn’t, and which owners could be trusted when things went wrong. That kind of information never makes it neatly into an application, but it absolutely shows up later in the loss ratio. When you know the character of the risk—not just the category—you make fewer expensive mistakes.

The company’s mutual structure reinforced that cautious, long-term culture. Mutual insurers ultimately answer to policyholders, not public-market shareholders. Policyholders want stable pricing and confidence that claims will be paid—not a growth story. That alignment gave management permission to do the most important thing in insurance, over and over again: say no. No to underpriced business. No to “just this once” exceptions. No to pretending reserves will work themselves out. The playbook was simple and, frankly, boring: write business you understand, hold adequate reserves, invest conservatively, and let time do the compounding.

Across the postwar decades, UFG expanded steadily—first across Iowa, then into neighboring states like Nebraska, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Missouri. It broadened beyond its original auto and liability roots into more commercial lines, building capabilities in areas like workers’ compensation, commercial property, and surety bonds. Distribution stayed agent-driven, centered on independent agencies that valued relationships and fit the company’s conservative underwriting approach.

And UFG wasn’t alone. The Midwest was full of regional insurers that looked a lot like civic institutions. Executives sat on local boards. Employees lived near policyholders. Claims adjusters showed up as neighbors, not anonymous representatives. That closeness created a kind of accountability you can’t manufacture with policies and procedures.

By the 1990s, UFG had become a meaningful regional carrier with a strong reputation and an A.M. Best rating that reflected its conservatism. But the industry around it was changing. Consolidation was accelerating, and national players like State Farm, Allstate, and Travelers were building scale advantages—technology, marketing muscle, and broader risk diversification. For smaller regionals, the choice got sharper: stay local specialists with limited growth, or try to get bigger fast enough to matter.

That tension—between disciplined focus and the pull of expansion—was about to become UFG’s defining battle.

III. Demutualization & The IPO Gamble (1999–2001)

By the late 1990s, demutualization had become a full-on trend in insurance. Big names like Prudential, MetLife, and MONY were converting from policyholder-owned mutuals into shareholder-owned corporations. The pitch was simple: once you’re public, you can tap the capital markets, pay people in stock, and use your shares as acquisition currency.

MetLife’s conversion became one of the era’s headline examples. It issued an enormous number of shares, and it was so sprawling that MetLife later estimated roughly 60 million shares tied to the demutualization went unclaimed. Its IPO priced 202 million shares at $14.25, and in the year after going public, the stock price nearly doubled.

That was the atmosphere UFG was operating in: a roaring market, a consolidating industry, and a clear message that “bigger” wasn’t just better—it was safer.

So UFG made its own leap. In 2001, the company went public on NASDAQ under the ticker UFCS. The IPO wasn’t just a financing event; it was a strategic pivot. Public stock meant capital to pursue acquisitions instead of relying on organic growth. It meant equity compensation to recruit and retain talent. And it meant UFG could play the same consolidation game as larger competitors—pushing beyond its Iowa base with a balance sheet built for buying.

At first, it looked like the right call. The stock held up reasonably well after the offering, and leadership laid out an expansion story that made intuitive sense. Diversify geographically and you’re less exposed to any one region’s catastrophe season. Add product lines and you can cross-sell. Grow scale and, in theory, your expense ratio comes down.

But the most important change wasn’t on a map or in a product catalog. It was in the incentives.

As a mutual, the company’s default setting was restraint. Policyholders didn’t want a “growth strategy”; they wanted stable premiums and confidence that claims would be paid. As a public company, UFG now had a second audience—shareholders—and that audience wanted earnings momentum. Compensation tied more directly to premium volume and stock performance introduced a new kind of gravity. “Is this good business?” was no longer the only question. It now had to share the room with, “Will this help us hit the quarter?”

And here’s the trap: insurance keeps score on a delay. Underwriting mistakes don’t show up immediately the way they do in most businesses. A policy priced too cheaply in the mid-2000s might not fully reveal itself until years later, after claims develop, legal costs stack up, and reserves have to be strengthened. By then, the premium has long since been booked, the growth has already been celebrated, and the people who made the call may be gone.

UFG had stepped onto a path where the rewards arrived fast—and the consequences arrived late.

IV. Aggressive Expansion & The Underwriting Disaster (2002–2013)

In the years after the IPO, UFG leaned hard into a single idea: diversification equals stability. Get out of the Midwest, spread the risk, add new lines, add new states—and smooth out the volatility that comes from being concentrated in one region.

On paper, it sounded like grown-up insurance strategy. In practice, it pulled UFG away from the one thing it had always been best at: underwriting risks it truly understood.

The biggest symbol of that expansion push arrived in March 2011, when United Fire completed its acquisition of Mercer Insurance Group. The logic was explicit in the company’s own announcement: Mercer primarily marketed in six Western and Mid-Atlantic states where United Fire had no appointed property-and-casualty agencies. There was “no overlap” in agency networks, which meant instant reach. Overnight, United Fire could market through more than 1,000 independent agencies and claim it was diversifying weather and catastrophe exposure across a broader footprint.

The terms underscored how serious the bet was. Mercer shareholders received $28.25 per share in cash, for a total transaction value of about $191 million. UFG said it anticipated the acquisition would add to net income and return on equity by 2012.

And internally, this wasn’t framed as a bolt-on. It was framed as a step-change. Mercer, a New Jersey-based insurer, brought UFG into markets where it had essentially no presence. CEO Randy Ramlo, who had been in the role since May 2007, positioned the deal as transformational. Based on 2009 net written premiums, the combined company was expected to rank among the top 50 publicly traded U.S. property-and-casualty insurers, with the business skewing heavily toward commercial lines.

But here’s what that kind of map expansion always hides: underwriting isn’t a spreadsheet exercise. It’s context. It’s local knowledge. It’s knowing what’s normal in a claims environment, what’s dangerous in a court system, which agents consistently bring you good risks, and which ones show up when the market’s soft because they’re shopping the cheapest paper they can find.

Pricing risk in California is not a harder version of pricing risk in Iowa. It’s a different sport. Different catastrophe profiles. Different legal dynamics. Different relationships. Different everything. And the advantage UFG had cultivated over decades in the Midwest—the ability to judge risk with real familiarity—couldn’t be transplanted overnight to New Jersey or Arizona just because the company now had licenses and agencies there.

The first hints showed up quickly in the numbers and in the language used to explain them. In 2011, catastrophe losses piled up. Year-to-date catastrophe losses totaled $71.0 million, and management was careful to point out that, if catastrophe activity had been in line with historical experience—and without Mercer acquisition expenses—results would have looked more like the prior year. The message was: this is temporary noise, not a structural issue.

But the structural issue was already forming.

The real problem wasn’t one storm, or one acquisition, or one unlucky year. It was the gradual cultural drift that followed the strategic drift. The chase for premium volume—now reinforced by public-market expectations and compensation tied to growth—creates subtle pressure. You don’t wake up one day and decide to underwrite badly. You make a little exception. You lean into a new segment because competitors are growing there. You accept risks you don’t fully understand because the top line looks good and the consequences won’t show up until later.

And in insurance, “later” is the whole trap.

As UFG pushed further into unfamiliar markets and accepted business it didn’t have a durable edge in, combined ratios started to creep the wrong way. That’s not a cosmetic KPI. That’s the business model flashing red. When combined ratios live above 100%, the insurer isn’t earning its way to profit—it’s effectively paying customers to take its product, hoping investment income and time will make up the difference.

They won’t. Not for long.

Insurance math is brutally fair: premium inadequacy eventually becomes losses. Keep doing it year after year, and book value erodes—slowly at first, then suddenly.

V. CEO Turnover & Failed Turnaround Attempts (2014–2020)

By the mid-2010s, it was hard to avoid the conclusion: the expansion playbook hadn’t delivered stability. The combined ratio stayed stubbornly high, catastrophe seasons kept landing like body blows, and commercial auto—the line that humbles insurers across the industry—became a recurring source of pain.

UFG’s own messaging started to sound less like a growth story and more like triage. In commentary tied to the company’s 2019 results, CEO Randy Ramlo didn’t try to sugarcoat what was happening. He pointed to commercial auto losses and prior-year reserve strengthening in the Gulf Coast region as drags on profitability, then said the quiet part out loud: “From a profitability standpoint, the fourth quarter was disappointing and an unacceptable end to a year in which we failed to meet expectations and failed to make an operational profit.” The company had pushed double-digit rate increases and used non-renewals to cut away problem accounts, but even with those moves, it couldn’t get commercial auto back to underwriting profitability in 2019.

The financial results matched the tone. In the fourth quarter of 2019, UFG posted a consolidated net loss (including investment gains and losses) of $23.2 million, or 93 cents per diluted share. For the full year, it still reported consolidated net income of $14.8 million, or 58 cents per diluted share—but that was down sharply from 2018’s $27.7 million, or $1.08 per diluted share.

Then 2020 arrived and wiped away any remaining illusion that the problems were contained. For the full year, UFG recorded a net loss of $112.7 million, or $4.50 per diluted share, versus the modest profit the year before. Management attributed the swing primarily to a decline in the fair value of equity securities, higher losses and loss settlement expenses—especially catastrophe losses—along with lower net premiums earned and lower net investment income.

The credit analysts noticed. In December 2020, AM Best revised the outlooks to negative from stable and affirmed the Financial Strength Rating of A (Excellent) and the Long-Term Issuer Credit Ratings of “a” for UFG’s P/C subsidiaries operating under an intercompany pooling agreement led by United Fire & Casualty Company. AM Best also revised the outlook to negative from stable while affirming UFG’s Long-Term ICR of “bbb.” The explanation was blunt: the company’s underwriting and operating results had been too volatile, driven by challenging conditions in commercial auto liability and ongoing exposure to catastrophe and weather-related losses.

The stock market delivered its own verdict. UFG shares had once closed as high as 47.65 on August 1, 2018. But as underwriting losses piled up and confidence drained away, the stock sank to single digits. And the damage wasn’t just on the chart—it was in the balance sheet. Book value kept sliding; at the end of 2020, the company reported book value of $32.93 per share, down $3.47 per share, or 9.5%, from December 31, 2019.

There was one moment of clarity amid the turmoil: UFG chose focus over complexity. In March 2018, its subsidiary United Fire & Casualty Company completed the sale of United Life Insurance Company to Kuvare US Holdings for $280 million in cash. The divestiture turned UFG into a pure property-and-casualty company—and it freed up enough capital that the board approved a special cash dividend of $3.00 per share, expected to total about $75 million, payable August 20, 2018 to shareholders of record as of August 3.

Ramlo’s tenure had real milestones. Under his leadership, UFG grew headcount from 667 to 1,091, increased net written premiums from $501 million to $941 million, and raised book value from $27.63 to $35.05. The Mercer acquisition in 2011 and the exit from life insurance in 2018 were defining strategic moves.

But this is insurance. In the end, legacies don’t get written in press releases or premium volume. They get written in loss development, reserve adequacy, and whether the combined ratio stays under 100%. And by the time Ramlo’s final years were over, the story the numbers told was unmistakable: UFG still hadn’t found a way back to consistent underwriting profitability.

VI. The Kevin Leidwinger Era & Radical Repositioning (2022–Present)

In February 2022, UFG signaled that the long era at the top was ending. President and CEO Randy Ramlo announced he would retire later that year, closing out a run that had begun in May 2007. In his statement, Ramlo framed it as a handoff moment: after 15 years as CEO, it was time for a new leader to take the business—and the culture—into whatever came next.

The board didn’t promote from within this time. It went outside Cedar Rapids and hired Kevin Leidwinger, an insurance executive with more than 30 years in the industry. UFG announced that Leidwinger would join on Monday, August 22, 2022, stepping into the CEO role Ramlo had spent months preparing to leave.

Leidwinger arrived with a very specific kind of credibility: big-company commercial insurance operations. Before UFG, he was President and Chief Operating Officer of CNA Commercial in Chicago. Earlier in his career, he spent many years at Chubb Commercial Insurance in casualty, liability, and underwriting management roles. In other words, he wasn’t coming in to “discover” the math of commercial lines. He’d lived in it.

His early messaging was deliberately steady—less reinvention, more fundamentals. He emphasized UFG’s history and talked about a familiar set of priorities: long-term profitability, strong agency relationships, diversified growth, and continuous innovation.

Then the numbers reminded everyone how hard this turnaround still was.

For 2023, UFG reported net premiums written of $1.1 billion, up 8.4% from 2022. But the profitability story lagged badly. The GAAP combined ratio came in at 109.3%, driven by a 74.4% loss ratio and a 34.9% underwriting expense ratio. The underlying combined ratio was 97.1%, with an underlying loss ratio of 62.2%, a catastrophe loss ratio of 6.2%, and prior year reserve development of 6.0%.

A 109% combined ratio is the kind of figure that doesn’t require interpretation: it means UFG was paying out more in claims and expenses than it brought in through premiums. And the composition mattered. The loss ratio included a 6.0% hit from reserve strengthening tied to excess casualty business, along with adverse pressure from social inflation in liability lines for accident years 2016–2019.

AM Best responded in August 2023. It downgraded the financial strength rating of UFG’s P&C subsidiaries to A- (Excellent) from A (Excellent), and cut the long-term issuer credit rating to “a-” (Excellent) from “a” (Excellent). It also downgraded UFG’s long-term ICR to “bbb-” (Good) from “bbb” (Good). The one small relief: the outlook moved to stable from negative.

UFG’s response didn’t try to spin the moment as anything other than a reset in progress. The company pointed to a long list of actions already underway: re-engaging distribution partners and restoring responsible growth in core commercial, expanding surety, specialty and assumed reinsurance, reshaping underwriting to deepen expertise for small business and middle market customers, reducing its catastrophe footprint across the portfolio, and bringing greater actuarial rigor to the organization. It also highlighted expense actions aimed at sustainably lowering the expense ratio—while still funding investments in technology, analytics, and talent.

VII. Modern Era: The Turnaround Takes Hold (2024–2025)

By 2024, the work started showing up where it matters in insurance: the combined ratio. For the full year, UFG posted a 99.2% combined ratio—an improvement of 10.1 points from 2023’s 109.3%. That move wasn’t one lucky quarter. Management pointed to improvement across the components of the loss ratio, and the year finished with an underlying loss ratio of 57.9%, a catastrophe loss ratio of 5.4%, no prior-year reserve development, and an underwriting expense ratio of 35.9%. The underlying combined ratio improved to 93.8%.

The income statement finally followed. Net income rose to $62.0 million. Net investment income climbed 37.5% to $82.0 million, a meaningful tailwind in a business that lives and dies by the partnership between underwriting and the portfolio. Premiums also grew—net written premiums increased 15% to $1.2 billion. And book value per share ticked up by $1.76 to $30.80 at year-end 2024.

If the full-year numbers showed progress, the fourth quarter hinted at a shift in trajectory. The quarter’s combined ratio came in at 94.4%, the lowest in 11 quarters. Leidwinger credited the improvement to earned rate increases outpacing loss trends, plus tighter underwriting discipline that was showing up in better frequency outcomes.

But he didn’t declare victory. “While 2024 marked a return to underwriting profitability for UFG, our work is far from finished.”

Then came the kind of quarter that, for a turnaround, changes the conversation.

In Q3 2025, UFG reported net income of $39.2 million ($1.49 per diluted share), up $19.4 million versus the prior year period. Adjusted operating income was $39.5 million ($1.50 per diluted share), up $18.4 million.

The combined ratio dropped again—down 6.3 points to 91.9%. That’s not “better.” That’s legitimately exceptional underwriting in P&C. The quarter broke down to an underlying loss ratio of 56.0%, a catastrophe loss ratio of 1.3% on relatively light catastrophe activity, no prior-year reserve development, and an underwriting expense ratio of 34.6%. The underlying combined ratio improved to 90.6%. Net written premium increased 7% to $328.2 million.

Book value per share rose $4.42 to $35.22 as of September 30, 2025, compared to year-end 2024. Adjusted book value per share increased $2.70 to $36.34 over the same period. Return on equity was 12.7% as of September 30, 2025.

Management pointed to the familiar drivers—continued rate achievement, favorable frequency trends, and favorable large loss experience—and framed the result plainly: the best third-quarter combined ratio in nearly 20 years, while also delivering a third-quarter record in net written premium.

Meanwhile, the investment engine kept strengthening as higher rates worked their way through the portfolio. Net investment income was $26.0 million for Q3 2025, up $1.5 million, with income from the fixed-maturity portfolio increasing by $3.2 million due to portfolio management actions and reinvestment at higher yields. UFG said it expected the fixed-maturity portfolio to generate more than $80 million of annualized fixed-maturity income, with potential upside as reinvestment continues.

The ratings agencies, long a pressure point for UFG, reflected the improved trajectory without getting ahead of themselves. A.M. Best affirmed the group’s A- (Excellent) financial strength rating and “a-” (Excellent) long-term issuer credit ratings, with stable outlooks. Best cited UFG’s solid regional franchise and long-standing agency relationships, while noting management’s continued focus on catastrophe and weather exposure—and that recent results had benefited from earned rate increases and catastrophe losses coming in below historical averages.

And with confidence returning, capital started flowing back to shareholders more visibly. In December 2025, UFG’s board declared a quarterly cash dividend of $0.16 per share, payable December 19, 2025, to shareholders of record as of December 5. The company emphasized the continuity: this marked its 231st consecutive quarterly dividend, a streak going back to March 1968.

In the market, UFCS shares were no longer priced like a company in triage. The stock traded at $36.63 and had risen sharply over the prior year. After a long stretch where UFG’s story was defined by reserve pain, catastrophe volatility, and credibility loss, the company finally had something it hadn’t had in years: results that could speak for themselves.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

UFG’s path—from a conservative Midwest insurer, to an ambitious public-company roll-up, to years of ugly surprises, and now a real attempt at recovery—has a lot to teach. Especially in a business where the results of today’s decisions don’t fully show up until years later.

Lesson 1: The perils of misaligned incentives

Demutualization didn’t just change UFG’s ownership structure. It changed what the company was optimizing for. As a mutual, management ultimately answered to policyholders who wanted steady pricing and certainty that claims would be paid. As a public company, UFG also had to answer to shareholders who wanted growth and earnings momentum.

That shift isn’t inherently “bad.” It’s just different. But in insurance, it’s dangerous when the scoreboard is delayed. If compensation and expectations start leaning on premium volume, the pressure to say yes rises—yes to thinner margins, yes to unfamiliar risks, yes to the account that doesn’t quite fit but helps the top line.

And unlike most industries, you don’t get immediate feedback. A factory that ships defects hears about it fast. An insurer that underprices a long-tail liability risk might not feel the pain until claims develop years later. By then, the premium is booked, the growth has been celebrated, and the hole shows up as reserve strengthening and credibility loss.

Lesson 2: Geographic expansion requires local expertise

UFG’s original advantage was local knowledge. It wasn’t just “we write commercial insurance.” It was: we understand these towns, these contractors, these drivers, these buildings, these weather patterns, and these agents.

That kind of underwriting edge doesn’t travel well.

The Mercer deal is a perfect illustration. On paper, it was “diversification.” In reality, it dropped UFG into markets where competitors had spent decades building relationships, data, and instincts. In insurance, pricing isn’t a formula you can copy-paste from Iowa to New Jersey or California. It’s an accumulation of experience—how claims really behave, how courts really work, how risks are actually managed in the field. You can buy licenses and agency appointments quickly. You can’t buy institutional memory.

Regional carriers can expand, but they have to do it carefully. “We’ll figure it out” is one of the most expensive sentences in the industry.

Lesson 3: Underwriting discipline beats growth—every time

In insurance, a combined ratio under 100% isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s survival. Above 100% you’re losing money on the product itself. Do that long enough and you’re not “growing,” you’re melting book value.

The easiest time to lose your discipline is when the market is soft and everyone’s competing on price. Keeping volume up starts to feel like the job. But that’s exactly when the seeds of future reserve problems get planted.

The superpower is saying no—no to underpriced business, no to the risk you don’t understand, no to the account that only looks good because the market is being irrational. That takes a culture where underwriting standards are protected, not negotiated.

Lesson 4: In insurance, culture isn’t “soft”—it’s the operating system

The temperament that makes great underwriters—skeptical, detail-obsessed, comfortable disappointing someone—often clashes with the temperament that drives growth—optimistic, relationship-heavy, deal-oriented.

Great insurers keep those forces in balance. Struggling insurers let one side win.

Leidwinger’s emphasis on deepening underwriting expertise is a tell: UFG is trying to rebuild the muscle that prevents bad business from getting written in the first place. The workforce actions—cutting headcount while investing in underwriting, actuarial, and claims capability—fit that same idea. This isn’t just about costs. It’s about who has the authority in the room.

Lesson 5: Turnarounds take years in insurance

Insurance turnarounds don’t look like tech turnarounds. You can’t ship a new product and declare the pivot complete. Bad years linger. Policies written at inadequate rates take time to run off. Claims develop slowly. Reserve actions for old accident years can drown out real progress in the current book.

That’s why you should be careful about declaring victory after one good quarter.

UFG’s improvement—moving from a 109% combined ratio in 2023 to 99% in 2024, and then to 91.9% in Q3 2025—required a lot of unglamorous execution: earned rate increases, walking away from business through non-renewals, tightening underwriting, improving claims outcomes, and keeping expenses under control. The only thing that proves a turnaround in insurance is consistency through time.

Lesson 6: Float is both asset and liability

Insurance companies collect premiums now and pay claims later. That gap creates float—capital you can invest while you wait for claims to be paid. Buffett’s framing is famous: money that doesn’t belong to you, but you get to invest.

But float only compounds if underwriting is at least breakeven. If your combined ratio is consistently over 100%, float isn’t a gift—it’s effectively debt with a cost.

UFG’s growing investment income matters, especially with higher rates flowing through the portfolio. But it matters most because underwriting has started to work again. Trying to “invest your way out” of chronic underwriting losses is how insurers end up desperate—right before the next bad year finishes the job.

IX. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

1. Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Property and casualty insurance is a knife fight. There are dozens of credible competitors, and many of them are bigger, better funded, and better known.

The national giants—State Farm, Allstate, Progressive, Travelers—get scale advantages everywhere that matters: marketing spend, technology budgets, and the simple fact that a massive book of business can absorb volatility more easily. Regionals like Selective, Donegal, and UFG fight with different weapons: agent relationships, service, and the ability to make good local decisions quickly.

The problem is that insurance is closer to a commodity than most people realize. Policies may look different on paper, but buyers—especially commercial buyers—mostly experience insurance through price, claims handling, and whether their agent trusts the carrier. That keeps the market brutally competitive.

Then you layer on the cycle. In hard markets, prices rise and discipline returns. In soft markets, carriers chase premium, standards slip, and the whole industry pretends the math will work out. That cycle rewards patience and punishes ego.

This is where UFG’s positioning gets tricky. It’s too small to outspend or out-scale the giants, but it’s also not a tiny niche carrier with an obvious specialty moat. That means UFG can’t rely on structure to win. It has to rely on execution—underwriting, claims, and expense discipline that’s just better than peers.

2. Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM

Starting an insurer isn’t like launching an app. You need real capital, real reserving, and a rating that convinces customers and agents you’ll still be standing when claims come due. Regulators add another hurdle: licensing and compliance are state-by-state, slow, and expensive. And distribution matters—building an agency network takes time and trust.

InsurTechs like Lemonade and Root proved that technology can lower parts of the barrier, especially in distribution and user experience. But they also proved the harder point: the core difficulty hasn’t changed. Pricing risk accurately is still the whole game. Better interfaces don’t fix bad underwriting.

3. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

UFG’s key “suppliers” are reinsurers and people—actuaries, underwriters, and claims professionals.

Reinsurance is a global market with many players, which limits any one reinsurer’s leverage. Talent is more competitive, but still manageable—especially compared with the cost structures of coastal insurance hubs. The real constraint isn’t supplier power so much as the need to keep attracting and retaining the kind of disciplined underwriting and claims expertise that makes the whole model work.

4. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

On the commercial side, buyers have gotten smarter. Brokers and consultants run competitive processes, push carriers to sharpen pencils, and switch markets when they see meaningful savings. Relationships matter, but not enough to prevent churn when pricing spreads get wide.

Independent agents amplify this buyer power. Agents represent multiple carriers, and they decide who gets a shot at the submission and who gets the best opportunities. So UFG isn’t just competing for end customers—it’s competing for attention and trust inside the agency channel.

That’s why the mid-market focus matters. Large accounts are dominated by sophisticated procurement and broker leverage. Small accounts skew heavily toward price. The middle market is where relationships and service can still move the needle—if you deliver consistently.

5. Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

Big companies can self-insure, form captives, or use alternative risk transfer tools like catastrophe bonds and industry loss warranties for certain exposures. But for most small and mid-sized businesses, traditional insurance isn’t optional—it’s required by law, lenders, or customers. In practice, substitutes exist, but they’re mostly reserved for larger, more sophisticated buyers.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

1. Scale Economies: WEAK for UFG

Scale is real in insurance. The biggest carriers spread fixed costs across enormous premium bases, invest more in technology and data, and absorb volatility with less drama.

At roughly $1.2 billion of premiums, UFG is meaningful—but it’s not operating on the same playing field as the mega-carriers writing tens of billions. And because it distributes through independent agents, it can’t build the kind of proprietary distribution scale that a direct model can.

2. Network Effects: NONE

Insurance doesn’t get more valuable because more people buy it. A larger book helps diversification, but that’s not a network effect in the Hamilton sense. Each policy is still its own transaction.

3. Counter-Positioning: POTENTIALLY EMERGING

InsurTech tried to counter-position on “we’re digital, therefore better,” and a lot of them ran into the same wall: underwriting losses.

UFG’s potential counter-position is almost the opposite—an explicitly disciplined regional carrier that’s willing to shrink or walk away from business rather than chase premium. That message can resonate with agents and customers who value stability. But it’s not a durable advantage yet. It becomes real only if the company sustains the discipline when the cycle turns soft again.

4. Switching Costs: LOW-MEDIUM

Commercial accounts have some friction: tailored coverage, institutional knowledge, and a claims relationship can create hesitation. But switching still happens all the time, especially when pricing gaps appear.

Personal lines are even more fluid—many consumers will move for modest savings. Agency relationships help retention, but they’re not exclusive. Agents can, and do, move business.

5. Branding: WEAK

UFG isn’t a household name. That’s not fatal in commercial insurance—brand matters less than rating, relationships, and performance—but it limits differentiation. The A.M. Best A- rating provides credibility, yet many competitors can say the same.

6. Cornered Resource: NONE

There’s no exclusive distribution channel, proprietary dataset, or unique underwriting method here that competitors can’t pursue too. UFG’s assets are real—relationships, history, franchise value—but they aren’t cornered resources in the strict sense.

7. Process Power: DEVELOPING

This is the one “power” that could become meaningful. If Leidwinger and his team can build an organization that consistently prices risk better, selects better accounts, manages claims better, and keeps expenses in line, UFG can earn returns that look like a moat—even without one.

But process power has a high bar: it has to survive the cycle. Lots of insurers look brilliant in hard markets. The test is whether discipline holds when competitors start cutting price and agents start shopping aggressively.

Management’s stated goal of delivering 15% ROE over time signals confidence that the process is improving. The market will ultimately decide whether that confidence is earned—based on years of steady underwriting results, not a handful of strong quarters.

Conclusion: In Hamilton’s framework, UFG doesn’t have structural moats. Its best path is to keep building operational excellence—real process power in underwriting and claims—paired with disciplined capital allocation. If UFG compounds from here, it won’t be because the competitive landscape got easier. It’ll be because the company got better at playing the game than its size would suggest.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Framework

The Bull Case

The optimistic case for UFG is straightforward: after years of underwriting wounds, the turnaround finally looks like it has crossed from “promising” to “real.” The company is producing underwriting profit again, and it’s doing it while still growing premiums—something UFG struggled to balance for a long time.

Leadership is a big part of that story. Kevin Leidwinger didn’t come up through a small regional carrier; he came from large commercial insurance organizations at CNA and earlier at Chubb. That background shows up in where he’s pushing: deeper underwriting expertise, more actuarial rigor, and tighter claims management. Those aren’t abstract buzzwords for UFG. They’re direct answers to the company’s historical failure modes. And, importantly, the cultural message has changed from “grow” to “earn the right to grow.”

The market is helping too. Commercial lines have remained in a firmer pricing environment, which gives UFG room to push rate increases that can outpace loss trends. That breathing room matters in insurance because it buys time for better underwriting and claims practices to compound.

Then there’s the investment side. With the fixed-maturity portfolio generating more than $80 million annually, investment income is no longer a footnote. It becomes a meaningful stabilizer that can reinforce underwriting gains, especially if rates stay elevated.

Valuation is the other lever. UFG spent years priced like a company that couldn’t be trusted—because, for a while, it couldn’t. If the market becomes convinced that today’s results are durable, not cyclical luck, the upside isn’t just higher earnings; it can also be a re-rating of the multiple.

And if underwriting stays consistently below 100% combined ratio, capital return becomes more than symbolism. UFG has paid 231 consecutive quarterly dividends for a reason: it values that identity. Sustained profitability makes that streak easier to defend.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with a harsher truth: even a well-run UFG is still swimming in a brutal pool.

The company doesn’t have a structural moat. Insurance is highly competitive and often commoditized. If competitors decide to cut price, they can. Without the scale, brand power, or distribution advantages of the largest carriers, UFG has to win the hard way—by executing better, year after year, through the full market cycle. That’s possible, but it’s a high standard.

Climate and catastrophe exposure remains a real threat. Severe Midwest weather—derecho storms, floods, hail—has been a recurring source of volatility for UFG, and management can’t negotiate with the atmosphere. Even with better portfolio management, one ugly year can dominate the income statement.

Scale is another constraint. National carriers can spend more on technology, data, and distribution. UFG’s independent agent model has relationship strengths, but it doesn’t have the same built-in efficiency as direct distribution. That matters over the long run.

Turnarounds also come with execution risk that never fully goes away in insurance. A single bad catastrophe year, or one unexpected reserve charge, can erase years of progress in the eyes of investors—and sometimes in actual book value. The margin for error is thin.

And then there’s the cycle. Hard markets don’t last forever. When pricing eventually softens, that’s when discipline gets tested for real. Plenty of insurers look fixed in good markets and break again when competition returns.

Distribution is evolving too. Direct digital channels continue to gain share, especially in personal lines. UFG is focused on commercial business, but long-term channel shifts can still reshape the industry landscape and the relevance of agency-driven carriers.

Finally, UFG is still a “show me” story. After roughly fifteen years of disappointment, skepticism doesn’t vanish after a few strong quarters. The stock can remain discounted until the company proves, through time, that this isn’t another temporary upswing.

What to Monitor: Key Performance Indicators

If you’re tracking whether UFG’s turnaround is truly durable, three metrics tell you the most.

1. Combined Ratio — The non-negotiable. Staying under 100% is survival; sustainably landing in the mid-to-high 90s is what starts to look like a real franchise again. Catastrophe volatility will always move quarters around, so what matters most is the trend—and how results hold up when catastrophe activity normalizes or pricing gets less friendly.

2. Prior Year Reserve Development — This is where old mistakes resurface. Adverse development means the company is still paying for business it wrote years ago. UFG’s 2023 reserve strengthening tied to older casualty years is a reminder of how long the tail can be. Multiple quarters of neutral or favorable development is one of the clearest signals that the bad vintages are finally rolling off.

3. Return on Equity — The simplest scorecard that captures the whole machine: underwriting plus investment income, all measured against the capital base. UFG’s 12.7% ROE shows real progress, and management’s longer-term target of 15% provides a clear benchmark for what “fully fixed” is supposed to look like.

Secondary indicators worth watching include: - Underlying loss ratio (should trend toward the mid-50s, excluding catastrophes and reserve development) - Expense ratio (should gradually move lower as discipline and efficiency improve) - Premium growth vs. industry (growth, but never purchased with bad pricing) - Book value per share (steady compounding is the cleanest proof of value creation) - A.M. Best rating (holding “A-” remains critical to competing in the market)

XI. Epilogue: The Future of United Fire Group

UFG’s transformation—from a community-rooted insurer to a public-company expansion story, to a long stretch of underwriting pain, and now back toward disciplined execution—has played out over most of a century. And today it sits in a familiar place for any insurance turnaround: the numbers have started to cooperate again, but the only thing that can turn “improvement” into “trust” is time.

Strategically, the company looks clearer than it did for years. The posture is essentially: be a focused regional carrier, with national reach only where it actually has an edge. The center of gravity is commercial business—supported by surety, specialty lines, and assumed reinsurance. Personal lines have become less important as UFG leans into the parts of the market where relationships, underwriting expertise, and consistency still matter.

The other bet is modernization. UFG has continued investing in technology, with a new policy administration system approaching implementation and stronger data and analytics capabilities designed to sharpen risk selection and pricing. But insurance has a stubborn truth that no software can erase: technology can help you see and process information faster, but it doesn’t replace judgment. The difference between a good insurer and a bad one still comes down to whether the organization has the discipline to price risk correctly—and walk away when it can’t.

The existential variable is climate. The question isn’t whether UFG can handle a bad storm season. It’s whether a Midwest-focused carrier can profitably live with severe convective storms as weather patterns shift over decades. UFG has taken concrete actions to improve its catastrophe profile—reducing exposure in certain hurricane-prone geographies, improving deductible structures, and using portfolio management to shape risk. Even so, core exposure to Midwest weather volatility remains part of the franchise. If loss trends keep worsening, UFG may face an uncomfortable choice: shrink the footprint further, or accept a structurally more volatile earnings profile.

There’s also the open question of what UFG becomes in the industry’s consolidation cycle. The company could be an acquisition target for a larger regional or national carrier that wants Midwest presence and established independent agency relationships. It could also try to play offense and acquire smaller carriers or mutuals looking for an exit. But after a long period where capital was precious, the warning label on big acquisitions is obvious: growth can be bought quickly; underwriting control can’t. If UFG takes the acquirer path, it has to do it with a level of restraint the company didn’t always show in the past.

The bigger question goes beyond UFG and hits the whole category: can mid-sized regional P&C insurers survive long-term? They’re in an awkward competitive middle—too small to match the scale, technology budgets, and marketing power of national giants, but too large to hide in a tiny niche. They also face pressure from new distribution models that can shift buyer behavior faster than traditional carriers like.

The answer can still be yes, but only with one non-negotiable: underwriting discipline. Insurance has always punished companies that confuse premium volume with profit. The regionals that endure are the ones that protect their underwriting culture, invest in expertise, and resist the temptation to chase growth simply because the market is asking for it.

For investors, that’s the lens. UFG can be a compelling value story if the operational improvements prove durable, but the market won’t fully forgive the past based on a few strong quarters. In insurance, a franchise isn’t built on momentum. It’s built on years of consistent execution—especially when the cycle turns.

In the end, UFG’s future won’t be decided in Cedar Rapids boardrooms. It will be decided in thousands of individual calls: which risks to write, at what price, with what terms, and with what willingness to say no. In this business, those decisions compound. And over time, they write the only ending that matters.

XII. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—into UFG specifically, and into the insurance business that shaped (and punished) its choices—these are the best places to start:

-

UFG Annual Reports (2018–2024) — The CEO letters are where the turnaround is most clearly narrated in real time: what went wrong, what changed, and what management believes will actually stick. Available at ir.ufginsurance.com.

-

"The Essays of Warren Buffett" by Lawrence Cunningham — The cleanest explanation of what makes insurance such a compounding machine when it’s run well, and such a value destroyer when it isn’t: float, underwriting discipline, and the delayed scoreboard.

-

"Against the Gods" by Peter Bernstein — A broader history of how modern society learned to measure, price, and transfer risk. It’s not “about insurance,” but it makes the whole industry’s role feel inevitable.

-

A.M. Best Rating Reports — If you’ve ever wondered why ratings matter so much in commercial insurance, Best’s methodology and commentary lay it out: capitalization, reserve strength, underwriting performance, and catastrophe exposure.

-

NAIC Annual Statements — The statutory filings are where the real plumbing lives. They’re dense, but they reveal details you won’t get in SEC reports, including reserve development patterns over time.

-

Insurance Journal and Business Insurance — Two of the better windows into day-to-day industry reality: pricing cycles, regulation, catastrophe trends, and who’s actually gaining or losing share.

-

"Seeking Wisdom: From Darwin to Munger" by Peter Bevelin — A useful mental-model toolkit for thinking about uncertainty, incentives, and second-order effects—basically the things that decide whether an insurer is compounding quietly or accumulating future regret.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music