Urban Edge Properties: The Strip Mall REIT That Rose From Vornado's Shadow

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a Tuesday afternoon in suburban New Jersey. The kind of shopping center you barely notice—until you try to park.

A mom is loading ShopRite bags into the trunk while her teenager darts into T.J. Maxx. A few doors down, patients file into a physical therapy clinic beside a fitness studio. Someone’s grabbing a quick bite, someone’s picking up a prescription, someone’s returning an Amazon package. It’s not glamorous. It’s not trendy. It’s just… constant.

And that’s the point. The landlord behind this “unremarkable” scene is a publicly traded real estate company worth nearly $2.6 billion that most people—even many investors—have never heard of.

Urban Edge Properties trades on the New York Stock Exchange as “UE.” It’s a REIT that acquires, owns, develops, manages, and upgrades shopping centers in and around dense urban communities. Today, it owns nearly 15 million square feet across 84 properties, and it manages more than 5 million additional square feet for others.

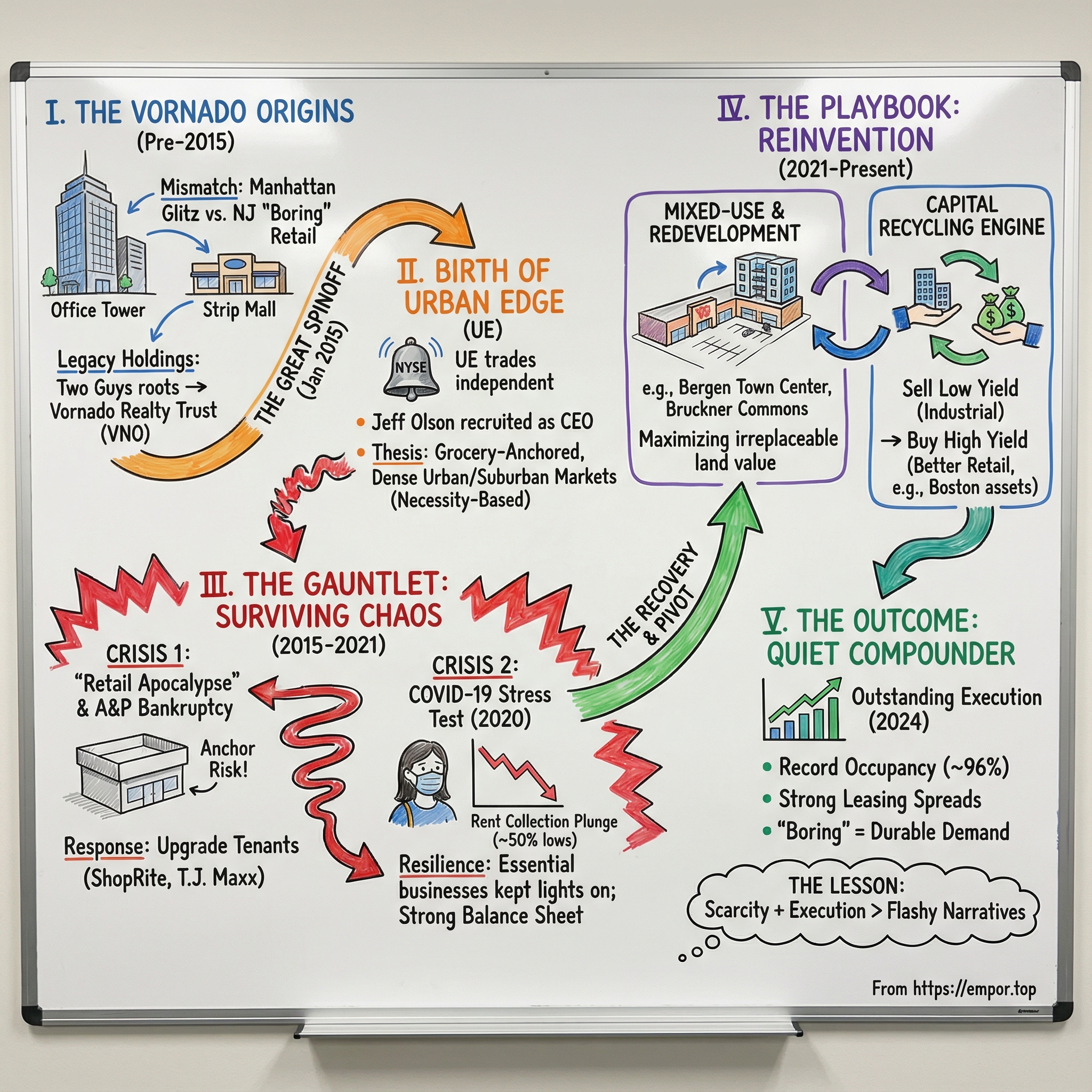

The question that makes this story interesting is deceptively simple: how did a collection of strip malls—spun out of one of the most sophisticated real estate empires in America—become its own billion-dollar public company? And, more importantly, why has it survived and improved while so much of retail real estate has been written off?

To answer that, we have to go back through decades of Northeast retail history, a major corporate separation engineered for tax efficiency, and three moments that could’ve ended the Urban Edge story almost as soon as it began.

In 2015, Vornado spun off its interest in Urban Edge Properties—essentially its shopping center holdings outside Manhattan—to Vornado shareholders. This wasn’t just housekeeping. It was a roughly $2 billion bet that grocery-anchored centers in supply-constrained New York and New Jersey markets could stand on their own, even as the dominant narrative was that Amazon had made physical retail obsolete.

Fast forward to 2024, and Urban Edge delivered what management called a year of outstanding execution. The company grew FFO as adjusted by 8% versus the prior year, and it raised its three-year earnings target a full year ahead of schedule. For a business that spent its early life getting punched by industry-wide chaos, that’s not a small thing.

This story turns on three inflection points. First, the A&P grocery bankruptcy in 2015–2016, which threatened to rip out the anchors of Urban Edge’s portfolio right after the spinoff. Second, COVID-19, the ultimate stress test for any retail landlord. And third, the company’s pivot toward mixed-use development—its bid to turn “just strip malls” into something with a longer runway.

What makes Urban Edge worth an episode isn’t that it’s flashy. It’s what it teaches: about spinoffs, about survival in a hated sector, and about the stubborn, enduring value of controlling irreplaceable land in the hardest places to build.

Let’s dive in.

II. The Vornado Years: Origins & Strategic Context (1960s–2014)

To understand Urban Edge, you have to understand the empire it came from. And that story doesn’t start with glass towers in Manhattan. It starts with televisions and electric fans in post-war New Jersey.

Two Guys was a discount store chain founded in 1946 by brothers Herbert and Sidney Hubschman in Harrison, New Jersey. Fresh out of the Navy, they came across a surplus of RCA televisions and started selling them out of a small lot. That scrappy, roughly 600-square-foot beginning turned into a real retail force.

On January 31, 1962, the company went public on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol VNO. At its peak, Two Guys operated more than 100 locations nationwide. The stores were an early version of the big-box idea—part Walmart-before-Walmart, part Costco-before-Costco, and part community hub. You could buy almost anything. Many locations even included full-sized supermarkets, competing with chains like A&P and ShopRite.

In 1959, the company made another pivotal move: it acquired the Vornado appliance brand. The retail chain wouldn’t last forever, but the name would.

Discount retail, though, is a knife fight. By the late 1970s, competitors like Kmart were rising, and Two Guys started to slide. Then came the insight that changes everything: the stores weren’t the valuable part of the business. The land was.

In late 1980, real estate investor Steven Roth—through his company, Interstate Properties, Inc.—moved in after concluding that the real value sat beneath the aisles and checkout lanes. The company began liquidating the Two Guys retail operation, closing stores that were already bleeding; the chain had posted a $20 million loss in the first half of 1981.

This is the moment Roth truly enters our story—and then essentially dominates it for the next four decades. In 1980, Interstate acquired an 18% stake in Vornado. In 1981, it took control after winning a proxy fight and shut more stores as the retail business unwound.

Roth became one of the most formidable operators in the industry. He served as Chairman of the Executive Committee beginning in April 1980, became Chairman of the Board in May 1989, and held the CEO role from May 1989 through May 2009, before being reappointed CEO on April 15, 2013. Along the way, outlets like Barron’s and Institutional Investor repeatedly recognized him and his track record.

But the core of the Roth playbook was simple: if the operating business is mediocre but the real estate is great, you don’t fight to save the business—you turn the real estate into the business. After the retail stores were sold off, the company evolved into Vornado Realty Trust, a real estate owner and manager built around valuable commercial sites.

Over the 1990s and 2000s, Roth pushed Vornado far beyond its strip-center roots and into the heart of New York City. In 1997, in its first major move outside the strip-mall world, Vornado bought seven Midtown office buildings totaling 4 million square feet from Bernard H. Mendik for $656 million. A year later, it bought 20 more Manhattan office buildings for $1.7 billion, including One Penn Plaza.

By 2016, Vornado owned more than 50 New York City properties spanning 23.5 million square feet, making it the city’s largest commercial landlord. It became synonymous with trophy assets and big, ambitious bets: 666 Fifth Avenue, Penn Plaza, and the broader Penn District vision. The company’s identity became urban, high-profile, and capital-intensive.

And yet, sitting in the background the whole time were the legacy shopping centers—grocery-anchored strip malls and suburban retail properties that Vornado still owned largely because of where it started. Vornado drew criticism for being spread across too many sectors, and the disconnect became harder to ignore: these two businesses were together for historical reasons, not because they made each other better. There were no real operating synergies.

By the early 2010s, the mismatch was glaring. Vornado investors wanted Manhattan office and urban street retail—not grocery-anchored centers in places like Hackensack. The strip malls diluted the story, absorbed attention, and needed leadership that woke up every day thinking about leasing a ShopRite, not redeveloping a trophy tower. The stage was set for a clean separation.

And that’s why the Vornado parentage matters for Urban Edge. It wasn’t just a pile of properties—it was a portfolio shaped by decades of dealmaking, with a level of retail operating discipline and tenant relationships that a standalone company could build on. Most importantly, it included locations that are painfully hard to replicate in the New York and New Jersey metro area—land that had quietly become the real prize.

III. The Great Spinoff: Birth of Urban Edge (2014–2015)

Corporate spinoffs can be glorified dumpster drops—companies sweeping the awkward leftovers into a new ticker and hoping investors won’t notice. But the good ones do the opposite. They take a business that doesn’t fit, give it its own leadership and balance sheet, and let it finally be valued on its own terms.

That’s what Vornado set out to do. The company announced that its board approved spinning off its subsidiary, Urban Edge Properties, by distributing all of Urban Edge’s outstanding common shares to Vornado’s shareholders. After the distribution, Urban Edge would stand alone as an independent, publicly traded REIT on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol “UE.”

The structure was straightforward. Shareholders of record at the close of business on January 7, 2015 received one share of UE for every two shares of Vornado they owned. What showed up inside the new company wasn’t a rounding error. Urban Edge held interests in 79 strip shopping centers, three malls, and one warehouse park—more than 15 million square feet spread across ten states and Puerto Rico, with the heaviest concentration in New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania.

The distribution was designed to be tax-free for U.S. federal income tax purposes. That detail mattered. It meant shareholders could receive Urban Edge shares without an immediate tax bill—making it easier for the market to judge the new company on performance, not on the friction of the transaction.

And this wasn’t a slapdash carve-out. Vornado brought in Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley as exclusive financial advisors, with Sullivan & Cromwell as legal counsel. Heavy hitters like that don’t guarantee success, but they do signal intent: Vornado was treating this like a carefully engineered separation, not a clearance sale.

On January 16, 2015, “regular way” trading began for Urban Edge on the NYSE under “UE.” Vornado, already in the S&P 500, stayed put. Urban Edge landed in the S&P MidCap 400 and joined the Retail REIT sub-industry index—exactly where a strip-center landlord belonged.

But the paperwork and the index changes weren’t the hard part. The hard part was turning a portfolio into a company. And in a spinoff, the single most important variable is who’s holding the wheel.

Urban Edge’s board brought in Jeff Olson. Jeffrey S. Olson became Chairman and Chief Executive Officer on December 29, 2014, and he joined as a Trustee earlier that month. He wasn’t a Vornado lifer who had grown up in the Penn Plaza world. He was recruited for a specific job: take this orphaned retail portfolio and build an independent public REIT around it.

Olson’s resume was built for exactly that assignment. He had been CEO of Equity One from 2006 until September 1, 2014, and then joined Vornado to work on the separation. Before that, he ran major regions at Kimco Realty from 2002 to 2006. Even earlier, he covered REITs on Wall Street as an analyst at Salomon Brothers, CIBC, and UBS, and started out in finance and accounting roles at The Mills Corporation. In other words: he understood investors, he understood operators, and he understood shopping centers.

That mattered because the early market reaction was, at best, cautious. The unspoken question was obvious: why would anyone want the boring strip malls?

Urban Edge’s answer was a thesis, not a vibe. This wasn’t about department stores or fashion-forward retail. It was grocery-anchored, necessity-based shopping centers in dense urban and inner-suburban markets—places with real demand and real barriers to building anything new. It was the retail of daily life: groceries, pharmacies, fitness, urgent care, quick-service food, and the services people still need in person.

Still, day one was brutal in its own way. Urban Edge had to operate a portfolio of nearly 80 properties while building the infrastructure of a public company—finance, IT, HR, reporting, and a culture that wasn’t just “Vornado, but smaller.”

And even after the separation, the Vornado shadow didn’t disappear overnight. Steven Roth served as a Trustee of Urban Edge from 2015 to 2023, giving the new company continuity and oversight while Olson and his team established their own identity.

For spinoff-watchers, Urban Edge had the ingredients you want to see: a clean strategic rationale, a tax-efficient structure, serious execution on the transaction, and leadership with the right operating and public-market instincts. Now it had to prove the most important part—that these “boring” centers could hold up when retail stopped being boring and started being a blood sport.

IV. The Retail Apocalypse: Surviving the Amazon Era (2015–2020)

Urban Edge was born into chaos. In its first years as a standalone company, the loudest story in real estate was simple: retail was dying. E-commerce was surging, department stores were losing relevance by the month, and mall shutdowns were becoming a national sport. From 2015 through 2020, bankruptcies tore through household names—Toys “R” Us, Sears, Payless ShoeSource, Gymboree—and landlords everywhere learned the difference between “leased” and “safe.”

Urban Edge’s bet was that its centers weren’t the kind of retail Amazon could simply erase. Grocery-anchored shopping centers live on weekly routines, not weekend splurges. You can’t deliver a haircut, a dental cleaning, or a workout through a box on the porch. So from the start, the tenant mix skewed toward what people still had to do in person: groceries, pharmacies, services, and the everyday errand economy.

Then the first existential test showed up almost immediately.

On July 20, 2015, The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company—A&P—filed for bankruptcy again. In restructuring circles, a second trip through Chapter 11 sometimes gets nicknamed “chapter 22,” and in A&P’s case the timing was brutal: this came less than five years after its prior Chapter 11 filing at the end of 2010.

For Urban Edge, A&P wasn’t just another struggling retailer in the news cycle. It was a grocery anchor across multiple properties—exactly the kind of tenant the whole “necessity-based” thesis depended on. A&P’s filing listed more than $1 billion in assets and liabilities. And even after years of decline, it still had a major Northeast footprint through brands like Pathmark, Superfresh, Waldbaum’s, Best Cellars, and The Food Emporium—roughly 300 stores in total.

This is the nightmare scenario for a grocery-anchored landlord, especially one barely six months removed from its spinoff. Grocery stores are traffic engines. They pull people onto the property several times a week, and those trips spill over into the nail salon, the quick-service restaurant, the pharmacy, the off-price store. Lose the anchor and you don’t just lose rent—you risk breaking the entire ecosystem.

A&P’s deterioration had been visible. The company’s turnaround plan called for big capital improvements, but it only managed to spend about half of the roughly $500 million it had projected. Sales were sliding fast—down about 6% year over year in 2014, and the trend continued into 2015. The result was swift: A&P filed in July 2015 and closed its last store that November.

Urban Edge’s response is where you start to see the operating playbook that would define the company. Management didn’t treat the empty boxes as a death sentence. They treated them as a chance to upgrade. The company moved to backfill former A&P spaces with stronger grocers—names like Stop & Shop, ShopRite, and Whole Foods—turning a portfolio-level threat into a portfolio-level improvement.

That pattern—crisis, then upgrade—kept repeating. When a legacy retailer failed, Urban Edge leaned into uses that were harder to digitize and more durable in dense neighborhoods. Off-price concepts like T.J. Maxx and Marshalls. Fitness operators like Planet Fitness and UFC Gym. Healthcare and medical tenants—urgent care, physical therapy, dental—moving into spaces where yesterday’s retail simply couldn’t survive.

What the so-called retail apocalypse really revealed was a split. The most vulnerable retail—commodity goods sold in easily-shipped boxes—was getting hollowed out. But necessity-based, service-oriented, and experiential tenants were consolidating into the best locations, and they needed landlords who could keep centers relevant and well-leased. Urban Edge had built its strategy around that reality before it became obvious.

By the end of 2019, after five years of retail upheaval, the company’s core thesis was still standing. The portfolio was holding up, the operating metrics were moving in the right direction, and the centers were, in many cases, stronger than what Urban Edge inherited at the spinoff.

And then, just as the industry started to catch its breath, the next shock hit.

Then the pandemic arrived.

V. COVID-19: The Ultimate Stress Test (2020–2021)

March 2020 brought the kind of stress test retail landlords don’t model for. Overnight, governors across the Northeast ordered non-essential businesses to shut their doors, and the basic mechanism of the business—tenants open, customers shop, rent gets paid—stopped working.

By April 27, 2020, Urban Edge had collected 56% of April base rent and monthly tenant expense reimbursements. Only 55% of its gross leasable area was open for business—and measured by annualized base rent, it was worse: just 46% of the portfolio’s rent was being generated by tenants that were even operating.

Sit with what that means. In a matter of weeks, more than half the rent base effectively went dark. For a REIT—built to pay out cash flow and valued on the reliability of that cash flow—this wasn’t a bad quarter. It was a threat to the whole machine.

Urban Edge responded with one of the most painful signals a REIT can send: it suspended its quarterly dividend.

Management was explicit about why. With COVID-19 creating massive uncertainty, the company temporarily stopped distributions and said the board would monitor results and, later, intended to reinstate a regular quarterly dividend. That move preserved cash, but it also risked the trust of income-focused shareholders who owned UE for the yield and stability.

At the same time, CEO Jeff Olson leaned hard on the other half of the story—the balance sheet. He said the company’s “strong balance sheet,” roughly $1 billion of liquidity, and “low leverage structure” positioned Urban Edge to make it through. He pointed to a portfolio anchored by “high-volume, value and essential retailers,” and a financing setup built around property-level, non-recourse mortgages.

This structure mattered. Urban Edge went into the pandemic with substantial cash and a large pool of unencumbered properties—assets not pledged to any lender. And aside from its line of credit, its debt was largely made up of separate non-recourse mortgages tied to specific properties. In plain English: if one center became a problem, the damage could be contained to that asset. It was resilience by design, and in 2020, design started to look like foresight.

The recovery showed up in rent collections first—slowly, then more convincingly:

- As of August 4, 2020, the company had collected 72% of second-quarter base rents and 73% of July base rents.

- As of November 3, 2020, it had collected 86% of October gross rent, 83% for the third quarter, and 77% for the second quarter.

- As of February 12, 2021, it had collected 93% of fourth-quarter 2020 gross rent, improving from 89% and 81% at the earlier third- and second-quarter reporting points.

That climb—from the mid-50s in April to the low-90s by year-end—didn’t happen by accident. Restrictions eased. Tenants reopened. PPP helped many small businesses stay alive. And Urban Edge did the messy work in the middle: negotiating deferrals, restructuring leases, deciding when to support tenants who were genuinely broken versus pushing back on tenants using the crisis as cover.

Financially, the hit was real. Same-property net operating income, including properties in redevelopment, fell 16.6% versus the fourth quarter of 2019 and declined 14.1% for the full year. The company said the results were negatively impacted by rental revenue deemed uncollectible—$6.1 million for the quarter and $30.9 million for the year—primarily due to the pandemic. That “uncollectible” label is the bluntest kind of accounting: rent you will never see, tied to tenants that couldn’t make it and spaces that would have to be re-leased and reimagined.

COVID also exposed a split inside retail real estate. Urban Edge evaluated its tenant categories and believed roughly 42% of its annualized base rent came from essential businesses. Those tenants—grocery, pharmacy, and other needs-based services—kept the lights on. The pain concentrated elsewhere: gyms that stayed closed for months, restaurants constrained by capacity rules, and discretionary retailers dependent on foot traffic.

And Urban Edge’s geography cut both ways. New York and New Jersey were hit early and hard, with some of the strictest shutdowns in the country. But the same density that made the first wave brutal helped the recovery once reopening and vaccination took hold—because the underlying demand never left. People still needed groceries. They still needed prescriptions. They still needed nearby, convenient places to run life’s errands.

In the end, the pandemic did something important for Urban Edge’s narrative: it stress-tested the “grocery-anchored, necessity-based” thesis under extreme conditions—and it held. Enclosed malls languished. Urban street retail got crushed as offices emptied out. But neighborhood centers with essential anchors recovered faster, because in a crisis, convenience stops being a preference and becomes a requirement.

By the end of 2021, Urban Edge had survived the shock, stabilized the business, and reinstated the dividend. The immediate question was no longer whether the company would make it. It was what this experience would push the company to become next.

VI. The Post-COVID Pivot: Reinvention & Mixed-Use (2021–2023)

COVID forced a reckoning across commercial real estate. For Urban Edge, it also crystallized a strategic insight: even the best strip centers can only take you so far. If you control irreplaceable land in the New York metro, the highest and best use might not stop at retail.

That led to a mixed-use pivot. Urban Edge began looking at certain properties less like shopping centers and more like future neighborhoods—places that could support housing on top of (or next to) the retail that already worked.

One of the clearest expressions of that ambition was Bergen Town Center. Urban Edge announced plans for a 456-unit multifamily development with first-class amenities, underground parking, and co-working space, located within walking distance of the retail center—designed to feel like a self-contained community where residents could live, shop, dine, and spend time without getting back in the car.

At the same time, the move exposed a practical question: should a retail REIT actually become a multifamily developer?

In Bergen County, New Jersey—where land is scarce and zoning is complicated—the value opportunity was obvious. But the execution risk was real. Urban Edge ultimately chose a more disciplined path: it moved to sell a piece of Bergen Town Center—slated for redevelopment into more than 450 apartments—rather than build it themselves.

The plan for the Forest Avenue site was laid out in two phases, including a 166-unit phase and a 260-unit phase, with four floors of residential space over two or three levels of parking. And instead of taking on the full residential development burden, Olson said the company was weighing options like selling the parcels outright or forming a joint venture. The buyer pool, he noted, was large and included reputable multifamily developers who shared Urban Edge’s view that the site was one of the best residential development opportunities in Bergen County.

That decision told you a lot about how Urban Edge wanted to evolve. The company would push into higher-value uses—but it didn’t need to prove it could do everything in-house. Residential development demands a different toolkit than running shopping centers, and Urban Edge chose to monetize the land value while letting specialists take the construction risk.

Meanwhile, the company’s broader redevelopment engine kept getting bigger and sharper. A great case study is Bruckner Commons, a 22-acre retail center in the Bronx. Urban Edge expected to invest about $80 million into the asset. The point wasn’t just to “freshen it up.” It was to run the full playbook: invest capital where it’s accretive, drive rent growth through renewals and new leases, upgrade the tenant mix, and improve a center that sits in one of the Bronx’s most significant retail hubs, with roughly 700,000 people living within three miles.

Even Puerto Rico emerged as a surprising area of momentum. As the island rebounded from Hurricane Maria and the pandemic—helped by strong tourism and infrastructure investment—Urban Edge leaned in. In late 2021, the company committed $14 million to redevelop a 122,000-square-foot former Kmart box, tied to a new lease with Sector Sixty6, a family-oriented entertainment center. The venue included an arcade, bowling, the largest go-kart track in the Caribbean, a ropes course, and a Golden Corral restaurant—exactly the kind of “you can’t download this” tenant that fills a big box with real foot traffic.

By this point, redevelopment wasn’t a side project. Urban Edge had $162.6 million of active redevelopment projects underway, with $89.5 million of estimated remaining costs to complete. Management expected these projects to generate roughly a 15% unleveraged yield. In plain terms: the company believed it could create far more value by upgrading what it already owned than by buying fully stabilized properties at market pricing.

The flywheel showed up beautifully at Briarcliff Commons. The turning point was signing Uncle Giuseppe’s for a 37,000-square-foot space, anchoring the center alongside Kohl’s. Uncle Giuseppe’s, a gourmet grocer with multiple locations in New Jersey and New York, was built with two main entrances that activated a previously underused rear parking field. When it opened in February 2022, foot traffic rose 62% compared to 2019. That surge justified a full renovation—new sidewalks, landscaping, updated facades—and it helped pull in a stronger lineup of tenants like First Watch, Chop’t, Crumbl Cookie, and Chick-fil-A.

This is the compounding effect Urban Edge was chasing: land the right anchor, invest behind it, upgrade the mix, drive traffic, raise rents, and repeat.

The macro trend helped too. As remote and hybrid work reshaped where people spent their days, the “urbanization of the suburbs” accelerated—especially in dense corridors between Washington, D.C. and Boston. Centers that could serve as convenient, everyday hubs in affluent, supply-constrained suburbs became more valuable, not less.

Leasing momentum started reflecting that demand. During one quarter, the company executed 29 new leases, renewals, and options totaling 402,000 square feet. New leases totaled 123,000 square feet, and on a same-space basis those new deals produced an average cash spread of 44%. Across new leases, renewals, and options, same-space deals generated an average cash spread of 21%.

Those kinds of spreads were the tell. This wasn’t just a post-COVID bounce. It was evidence that Urban Edge’s centers—when actively repositioned—could capture meaningfully higher rents than the prior generation of tenants ever paid.

For investors, this period proved something important: Urban Edge wasn’t just surviving retail’s chaos anymore. It was evolving—using redevelopment and selective mixed-use moves to turn “boring” strip centers into higher-value, higher-growth real estate.

VII. Financial Engineering & Capital Allocation (2015–Present)

REITs are financial animals unlike almost any other public-company structure. They’re built to pay out cash, and in exchange for that tax-advantaged model, they’re required to distribute at least 90% of taxable income as dividends. The tradeoff is obvious: you don’t get to hoard capital. So if you want to grow, capital allocation isn’t a side quest. It is the game.

For Urban Edge, that game has increasingly been about capital recycling—selling what no longer fits, buying what does, and upgrading the portfolio faster than the market expects.

In 2024, the company acquired $243 million of assets at a 7.2% capitalization rate and sold $109 million of non-core assets at a 5.2% capitalization rate. One of the headline buys came late in the year: on October 29, 2024, Urban Edge acquired The Village at Waugh Chapel for $126 million at an initial 6.6% cap rate. It’s a grocery-anchored center in Gambrills, Maryland, in a highly educated and affluent trade area within 20 miles of Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and Annapolis.

Why does that cap-rate spread matter? Because in simple terms, selling lower-yielding real estate and buying higher-yielding real estate can lift earnings without needing heroic assumptions. If you can repeatedly trade out of assets the market is valuing richly and into assets the market is discounting, you don’t just “rotate the portfolio.” You manufacture accretion.

Management leaned into that point in its own words, highlighting what it called a strong track record. Over the prior sixteen months, the company said it had acquired more than $550 million of assets at about a 7% cap rate, funded in part through roughly $427 million of dispositions around a 5% cap rate—and signaled it expected to keep pushing that playbook in 2025.

The clearest example of the strategy came a year earlier, with a pair of acquisitions that effectively planted a flag in Greater Boston. On October 23, 2023, Urban Edge closed on the $309 million acquisition of Shoppers World and Gateway Center, two large-format, high-quality centers in the Boston area. Shoppers World totals 752,000 square feet and is anchored by names like Best Buy and Nordstrom Rack, plus a deep bench of TJX concepts—T.J. Maxx, Marshalls, HomeSense, and Sierra Trading. Gateway Center, at 640,000 square feet, is anchored by Target, Costco, and Home Depot.

These weren’t small “one more property” deals. They were scale deals—assets that gave Urban Edge critical mass in Boston, the northern bookend of its broader D.C.-to-Boston corridor strategy. Just as importantly, they fit the company’s post-COVID identity: big, necessity-and-value-driven centers where strong anchors create durable traffic and leave room for leasing and redevelopment upside.

On the other side of the ledger, Urban Edge funded that growth by selling assets that were either non-core or better monetized at the prevailing market price. In the same period, the company closed on the sale of two properties and one property parcel for an aggregate sales price of $318 million. Those dispositions totaled 1.5 million square feet and included the East Hanover Warehouses portfolio, Freeport Commons, and a CubeSmart self-storage facility. The biggest piece was East Hanover: on October 20, 2023, Urban Edge sold its 1.2 million-square-foot industrial portfolio in East Hanover, New Jersey for $217.5 million, representing a 4.9% cap rate on forward NOI.

That’s the arbitrage in one sentence: sell industrial at premium valuations and rotate into retail where yields are higher because the sector still carries scars from the “retail apocalypse” narrative. Urban Edge wasn’t arguing industrial was bad. It was arguing the price was too good—and that its own retail opportunities, in the right locations, offered better forward returns.

Even the tax plumbing was part of the discipline. The company said the proceeds from selling East Hanover and Freeport Commons were used to partially fund the Shoppers World and Gateway Center acquisitions, and that they were structured as part of a 1031 exchange—allowing Urban Edge to defer capital gains by rolling proceeds into like-kind property instead of paying taxes and shrinking the reinvestment pool.

The other half of capital allocation is the balance sheet—because none of this works if you’re constantly refinancing under pressure.

As of December 31, 2024, Urban Edge reported limited debt maturities through December 31, 2026: $23.7 million in 2025 and $116 million in 2026, totaling $139.7 million, or about 9% of outstanding debt. The company also reported roughly $900 million of liquidity. The practical takeaway is that when interest rates surged in 2022 and 2023, Urban Edge wasn’t staring down a wall of maturities that forced bad decisions. It had time—and time is negotiating leverage.

The dividend, too, shows the same rhythm: cautious when it has to be, and raised when earnings support it. On February 11, 2025, the Board of Trustees declared a regular quarterly dividend of $0.19 per common share, an indicated annual rate of $0.76 per share. Management framed it as a 12% increase, driven by higher earnings and taxable income.

And then there’s the long tail of the spinoff itself: the Vornado connection. Steven Roth served as a Trustee of Urban Edge from 2015 to 2023. His departure from the board in 2023 marked a real milestone—nearly nine years after the spinoff—as the company continued to establish itself fully outside Vornado’s orbit.

Zooming out, the key point for investors is this: Urban Edge isn’t trying to win by being a passive collector of rent checks. The value creation has been operational and intentional—redevelopment, leasing execution, and a steady drumbeat of sell-to-upgrade, buy-to-grow capital recycling that reshapes the portfolio over time.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape & Market Position

Urban Edge competes in a crowded world of retail REITs. The difference is that most of its peers try to win with scale and diversification, while Urban Edge tries to win by owning the hardest-to-replicate corners of one specific map: the dense, supply-constrained markets from Washington, D.C. to Boston, with a heavy emphasis on New York and New Jersey.

In the public markets, the shopping-center REIT bench is deep. Names like Regency Centers, Kimco Realty, Brixmor, SITE Centers, Kite Realty, Acadia Realty Trust, and Federal Realty all compete for the same things that matter most in this business: the best locations, the strongest anchors, and the tenants that can actually pay through cycles. Even Simon, while primarily known for malls, is part of the broader competitive gravity in retail real estate.

The giants make for useful contrast. Regency is one of the biggest grocery-anchored landlords in the country, with a portfolio that runs into the hundreds of properties and tens of millions of square feet, spread across many markets so no single region dominates the earnings base. Kimco is even larger—hundreds more centers, a massive footprint, and the kind of scale that lets it fund redevelopment, court national tenants, and keep its cost of capital competitive through almost any cycle.

Next to that, Urban Edge is clearly smaller and more concentrated. It was only formed in 2015, and it remains a niche player relative to the national platforms. But in retail real estate, being “small” isn’t automatically a disadvantage if what you own is scarce.

That’s the core of Urban Edge’s positioning. Its centers sit in dense, built-out communities where the combination of land scarcity, zoning constraints, and regulatory friction makes new retail development extremely difficult. In many New Jersey towns and New York’s outer boroughs, the entitlement process alone can be enough to kill a new project. Add environmental complexity and neighborhood opposition, and “just build a competing center” becomes more theory than reality.

Those barriers cut both ways, though. The same forces that protect Urban Edge from new supply also make operations expensive. Property taxes are high. Labor is costly. Regulations are complex. Politics can be unpredictable. In a market like this, you don’t get paid simply for showing up—you get paid for executing.

From the tenant’s point of view, that execution matters because the Northeast doesn’t offer endless high-quality options. A national retailer trying to expand in these markets can’t just pick from a menu of new shopping centers. There are only so many well-located, well-anchored centers with the right access, parking, and co-tenancy. When you control one of those nodes, you can attract better tenants and, in the right environment, push rents in ways that are harder in markets where new supply is always one zoning meeting away.

The competitive threats are still real. E-commerce remains a substitute for plenty of retail categories, even if it’s less disruptive for grocery, services, and experiential uses. And rivalry for the best assets and tenants is intense—both from other public REITs like Federal Realty, Regency, and Kimco, and from private buyers willing to pay up for quality in supply-constrained markets.

That brings us to the strategic question hanging over Urban Edge: scale. Urban Edge owns about 75 properties totaling roughly 17 million square feet of gross leasable area—meaningfully smaller than peers like Kimco or Regency. That can limit negotiating leverage with the biggest national tenants, constrain operating efficiencies, and make access to capital more sensitive to how the market feels about the stock at any given moment.

But smaller also means focused. Urban Edge can concentrate management attention on a tighter geography, know its municipalities and tenant ecosystems deeply, and pursue transactions that might be too small to matter for a mega-REIT. And rather than trying to be a consolidator, it has largely played a selective game—targeted, accretive acquisitions in the corridor where it believes its market knowledge and redevelopment capabilities give it an edge.

For investors, the key distinction versus the peer set is simple: Urban Edge is concentrated where others are diversified. Regency and Kimco spread risk across dozens of markets; Urban Edge concentrates it in one of the most supply-constrained regions in the country. That can amplify both upside and downside. If the region performs and Urban Edge executes, scarcity becomes a tailwind. If costs spike, politics shift, or the local economy weakens, there’s less geographic diversification to cushion the blow.

In other words, Urban Edge isn’t trying to outmuscle the giants. It’s trying to out-position them—by owning irreplaceable land, in places where “competition” often means fighting over the same limited set of existing centers, not building new ones.

IX. The Leadership & Culture Question

Leadership in real estate is easy to dismiss. The buildings are the assets; the leases are the contracts; the rent checks show up—or they don’t. But in a REIT like Urban Edge, where the whole strategy depends on redevelopment, leasing execution, and disciplined capital allocation, management isn’t window dressing. It’s the difference between a portfolio that drifts and one that compounds.

Jeff Olson’s path to the CEO seat reads like someone who decided early that he wanted to understand the business from every angle. He started in an entry-level finance role in real estate, then went looking for a graduate program that would let him keep working while leveling up. He chose Johns Hopkins Carey Business School’s part-time Real Estate and Infrastructure program, earning a Master of Science in Real Estate. He also holds a B.S. in Accounting from the University of Maryland and was previously a Certified Public Accountant.

More importantly, his professional background gives him a rare dual fluency: operator and capital markets. He ran major regions at Kimco Realty, one of the category’s giants, and served as CEO of Equity One from 2006 to 2014. Before that, he covered REITs as an analyst at Salomon Brothers, CIBC, and UBS. That combination tends to produce a specific kind of leader: someone who cares about the plumbing—lease terms, tenant health, redevelopment yields, balance sheet risk—because he knows exactly how the market will price the results.

You can hear that voice in how he talks about the business. After 2023, Olson put it this way:

"2023 was a year of outstanding execution for Urban Edge," said Jeff Olson, Chairman and CEO. "Across the company, our team delivered exceptional results, ending the year especially strong as highlighted by our financing, leasing and capital recycling activity in the fourth quarter. We also simplified our business by selling our warehouse portfolio and acquiring two of the highest quality shopping centers in Boston in an accretive transaction. We remain encouraged by the continued demand from retailers in our markets and the record low levels of new supply helping to drive rental rates in our portfolio."

That’s very on-brand for Urban Edge: direct, specific, and centered on controllables. Earnings calls tend to live in the operational details—leasing spreads, tenant mix, redevelopment progress, capital recycling—rather than big, promotional narratives. The company’s guidance posture has generally been conservative, with a bias toward underpromising and then delivering.

Culture is harder to measure than rent per square foot, but at Urban Edge it matters more than it does at most REITs—because the company is small. With only 109 employees, there’s nowhere to hide. A leasing decision, a redevelopment timeline, or a tenant negotiation doesn’t disappear into a corporate maze. It shows up in the numbers.

Urban Edge has also tried to formalize what it wants that culture to be. The company says it adheres to principles of excellence at all levels of the organization to nurture an environment of trust, accountability, and respect, and that it is committed to sound corporate governance to strengthen board accountability and promote the long-term interests of shareholders. And externally, it has been named one of the best places to work in New Jersey by NJBIZ Magazine for a third consecutive year.

The leadership bench underneath Olson reflects the same “lean but serious” approach: Mark J. Langer as EVP & CFO, Robert C. Milton III as EVP & General Counsel, Scott Auster as EVP & Head of Leasing, and Jeff Mooallem as EVP & COO. It’s a compact team with clear lanes—and importantly, the lanes map directly to the levers that matter in this business: capital, legal structure, leasing, and operations.

That structure also signals a broader philosophy. Urban Edge’s decision-making looks conservative, but not timid. The company will take redevelopment risk, but it has generally avoided speculative development. It will sell assets when pricing is attractive instead of hanging on out of nostalgia. And even when it’s actively deploying capital, it has kept meaningful liquidity buffers—because in real estate, the fastest way to lose the game is to get forced into a decision on someone else’s timeline.

The pandemic was the clearest window into how the company communicates with shareholders under pressure. Management didn’t blur the bad news. It reported rent collections frequently and with real granularity, even when the numbers were ugly. That kind of transparency builds credibility, and in a sector where trust can disappear in one bad quarter, credibility is an asset of its own.

X. Current State & Recent Developments (2024–Present)

By late 2025, Urban Edge looked less like a post-spinoff survivor and more like a mature operator hitting its stride—still facing the normal execution grind of retail real estate, but no longer fighting for credibility quarter by quarter.

That tone came through clearly when the company reported results for the quarter and year ended December 31, 2024 and issued its initial outlook for 2025.

“The fourth quarter capped an outstanding 2024 for Urban Edge,” said Jeff Olson, Chairman and CEO. “FFO as Adjusted increased by 8% for the year to $1.35 per share, allowing us to achieve our three-year earnings target - announced at our April 2023 Investor Day - one year ahead of plan. Growth was driven by new rent commencements, record leasing activity and accretive capital recycling.”

The headline story was occupancy and momentum. Same-property leased occupancy ended the year at 96.6%, up from both the prior quarter and the prior year. Consolidated leased occupancy was 96.8%, also up. And the most telling number was in the smaller spaces—the “shops” between the anchors—where leased occupancy rose to 90.9%, up materially year over year. Those are the deals that require the most day-to-day work, and they’re often the first place you see whether a landlord is actually winning on leasing.

At these levels, 96.8% is essentially full. In a functioning retail portfolio you don’t want to run at 100% forever—you need some vacancy to reshuffle tenants, upgrade the mix, and push rents. What matters is that Urban Edge was filling space while still preserving the ability to keep repositioning.

That operating strength also showed up in same-property NOI, which grew 7.4% in the fourth quarter of 2024. And in an example of how quickly sentiment can swing around a REIT when the quarter lands cleanly, Urban Edge reported EPS of $0.24—well above the forecast.

For 2025, the company guided to net income of $0.32 to $0.37 per diluted share, FFO of $1.36 to $1.41 per diluted share, and FFO as Adjusted of $1.37 to $1.42 per diluted share. It also expected same-property NOI growth, including properties in redevelopment, of 3.0% to 4.0%. In other words: not a victory lap, but a continuation of steady compounding.

One of the biggest drivers of visibility was the signed-not-open pipeline. As of December 31, 2024, the company had signed leases that hadn’t yet commenced rent that were expected to generate an additional $25 million of future annual gross rent—about 9% of 2024 NOI. Roughly $7.8 million of that was expected to hit in 2025. That’s the kind of backlog landlords love: growth that’s already contracted, just waiting to turn on.

On the portfolio front, Urban Edge kept executing the corridor expansion it had been building toward. On October 29, 2024, it acquired The Village at Waugh Chapel for $126 million at a 6.6% capitalization rate. The center is grocery-anchored and sits in Gambrills, Maryland—positioned within 20 miles of Washington, D.C., Baltimore, and Annapolis—squarely inside the same dense, high-income geography the company has been targeting all along.

At the same time, the portfolio was still doing what retail portfolios always do: evolving, shedding the past, and making room for what comes next. One example was Sunrise Mall, where Urban Edge reached an agreement with Macy’s to terminate its lease effective March 31, 2025—another step toward advancing the company’s plans for the property.

In the public markets, the stock reflected the usual REIT cross-currents—interest rates, sentiment, and expectations—more than any single quarter’s leasing stats. Shares traded within a 52-week range of $15.81 to $23.85. As of October 2025, the stock price was $20.48, implying a market capitalization of $2.58 billion, and the dividend yield was about 3.28%.

The shareholder base, too, looked different than it did at the spinoff. Many original Vornado shareholders who received UE stock in the distribution either sold quickly or held only if it fit their REIT exposure. Over time, the base shifted toward the natural long-term owners for a company like this: REIT specialists, income-oriented investors who value the dividend, and value buyers underwriting a gap between public-market price and the underlying real estate.

XI. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

If you run Urban Edge through Michael Porter’s Five Forces, you get a clearer picture of what’s structural in this business—and what’s execution.

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In Urban Edge’s core markets, new retail supply is incredibly hard to create. The practical blockers aren’t just money. It’s zoning, land scarcity, environmental review, community process, and timelines that can stretch for years. When those frictions stack up, existing centers start to look less like “one of many” and more like protected franchises.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

The truly scarce input here is the land in the right places—and Urban Edge already owns it. Most of the rest is replaceable. Construction and service vendors compete for work, and while costs can swing with the cycle, Urban Edge isn’t dependent on any single supplier the way a manufacturer might be.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Tenants): MEDIUM

Tenants have options, especially national chains that can play landlords against each other. But that leverage has limits in dense, high-income corridors where there simply aren’t infinite high-quality sites with the right traffic, parking, access, and co-tenancy. Regional and local tenants generally have less negotiating power, and once a store is built out and running, moving is expensive and disruptive—even if the lease eventually expires.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM

E-commerce is still the shadow over all retail. But Urban Edge is concentrated in categories that don’t migrate cleanly online: groceries, healthcare, fitness, and services. The pandemic made that distinction feel less theoretical. People can shift how they shop, but they still need places to go for the essentials.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

This is where it gets brutal. Urban Edge competes with well-capitalized peers like Kimco, Regency, and Federal Realty, plus private equity buyers chasing the same quality assets and the same tenants. And from a tenant’s perspective, many shopping centers can look interchangeable. So the fight becomes: who has the better location, who can offer the best economics, and who’s the easiest to do business with.

Net Assessment: Shopping centers are not a structurally “great” industry—tenants have leverage, and the product can feel commodity-like. Urban Edge’s edge isn’t the model. It’s the map: scarce sites in places where new supply is painfully difficult, and where the right properties can hold their ground through cycles.

XII. Strategic Frameworks: Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s “7 Powers” framework asks a simple question: what, if anything, gives a company a durable edge that competitors can’t just copy?

Scale Economies: WEAK

There are real, but limited, scale benefits in this business. A larger platform can spread corporate overhead across more rent-paying square footage, run centralized leasing and property management more efficiently, and sometimes negotiate a bit harder with vendors. But compared to industries where scale drives dramatically lower unit costs, these advantages are incremental.

Network Effects: NONE

Shopping centers don’t get stronger because the landlord owns more shopping centers. There are some weak co-tenancy dynamics—one great anchor can lift the rest of the roster—but that’s property-level, not a network effect that compounds across the company.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK

Urban Edge isn’t doing something the giants can’t do. Grocery-anchored centers, active asset management, redevelopment, even selective mixed-use—those are playbooks available to any well-capitalized competitor. The barrier isn’t the idea. It’s getting the right sites and executing well.

Switching Costs: MEDIUM

For tenants, moving is painful. They’ve sunk money into build-outs, built routines and customer habits, trained staff, and integrated the location into their local marketing. That creates meaningful friction. But it’s not permanent protection—leases roll, and tenants will relocate if the economics or the trade area shift.

Branding: WEAK

Consumers don’t show up because a center is “owned by Urban Edge.” The brand matters more in the B2B sense: does the landlord have a reputation for being responsive, reasonable, and good at keeping the property healthy? That helps at the margin, but it’s not a consumer-facing magnet.

Cornered Resource: MEDIUM-STRONG

This is where Urban Edge has its clearest power. The company controls real estate in dense, supply-constrained corridors, where “just build another center” is often impossible due to land scarcity, zoning, and entitlements.

In other words, the advantage isn’t that Urban Edge is the smartest landlord. It’s that it owns pieces of land—specific corners, specific parcels, with existing infrastructure and approvals—that other landlords simply can’t recreate. If you want exposure to certain retail nodes in the New York and New Jersey metro, there aren’t infinite alternatives.

Process Power: WEAK-MEDIUM

There’s some process advantage in being good at the grind: leasing relationships, redevelopment reps, municipal know-how, and the repeatable playbook of upgrading centers over time. But it’s not an unbreakable system. In a company this size, a lot of the edge still lives in people—and people can leave.

Conclusion: Urban Edge’s moat is primarily Cornered Resource—scarce, hard-to-replicate locations—supported by moderate Switching Costs. That’s a very real advantage in real estate, but it’s not enough on its own to guarantee market-beating returns. The difference between “good” and “great” still comes down to execution.

XIII. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

THE BULL CASE:

Location, Location, Location. Urban Edge controls retail sites in some of the densest, highest-income, hardest-to-build markets in the country. In the DC-to-Boston corridor—especially in New York and New Jersey—land is scarce, entitlements are hard, and meaningful new retail supply is limited. These properties aren’t interchangeable; in many towns, they’re the few viable retail nodes that can actually exist.

Mixed-Use Optionality. The redevelopment pipeline—especially the ability to layer residential onto retail—creates embedded upside that doesn’t always show up in today’s earnings. Every well-located center with excess land, parking, or underused boxes is effectively an option on future NOI growth if zoning, partners, and capital line up.

Retail Resurgence. Physical retail isn’t back to being trendy, but it has stabilized—particularly in necessity-based categories. The retail apocalypse cleared out weaker tenants and weaker locations. What’s left is a more rational environment where good centers can lease space, push rent, and stay relevant through tenant mix upgrades.

Demographic Tailwinds. The DC-to-Boston corridor includes some of the most educated, highest-income populations in the U.S. In retail real estate, that matters because high incomes and density translate into more frequent trips, stronger sales productivity, and deeper demand for services that can’t be shipped in a box.

Valuation. At various points, Urban Edge has traded below estimated net asset value. If you believe the underlying real estate would fetch stronger pricing in private-market transactions than the public market implies, the stock offers a potential re-rating lever that doesn’t require the business model to change—just sentiment and proof of execution.

Dividend Yield. Urban Edge’s dividend yield is 4.03%. For investors who want income, a 4%+ yield can be compelling—especially if it’s supported by improving operations rather than financial engineering.

Insider Alignment. Management owns meaningful stock, and Olson’s compensation is tied to shareholder returns. In a business where capital allocation is the whole game, aligned incentives matter.

THE BEAR CASE:

E-Commerce Secular Decline. Online retail keeps taking share. Even grocery—Urban Edge’s strongest category—faces more delivery competition over time from Instacart, Amazon Fresh, and Walmart+.

Interest Rate Sensitivity. REITs often trade like bond proxies. Higher rates can pressure valuations and raise financing costs. Rate volatility also makes redevelopment and development underwriting harder, because your cost of capital can change faster than your leasing assumptions.

NY/NJ Headwinds. The region is expensive: high taxes, heavy regulation, and union labor costs. Population growth has lagged faster-growing Sun Belt markets, and COVID-era outmigration could prove more durable than investors want to assume.

Scale Disadvantage. Urban Edge is smaller than the megacap shopping-center REITs. That can limit its ability to win the biggest acquisitions, command the deepest national tenant relationships, or access capital markets as cheaply and consistently as the giants.

Development Risk. Mixed-use is attractive on paper, but residential development is not the same business as operating shopping centers. It introduces execution risk, longer timelines, and the possibility that management attention gets spread too thin.

Concentration Risk. Geographic and tenant concentration cuts both ways. A regional recession, regulatory shock, or major anchor bankruptcy would hit Urban Edge harder than a more diversified peer.

Limited Growth Runway. In supply-constrained markets, there may be fewer large external growth opportunities. If acquisitions are scarce and redevelopment slows, organic growth from rent escalators and leasing spreads may not match higher-growth REIT categories.

Commodity Business. At a fundamental level, shopping centers can still be a commodity business. Without clear differentiation, returns can erode through competition for tenants, rising costs, or shifts in retail demand—even in good locations.

XIV. Key Metrics & What to Watch

If you’re tracking Urban Edge as an investor, don’t get lost in the noise. This business usually tells you the truth through a handful of operating indicators—metrics that show whether the portfolio is getting stronger, whether pricing power is real, and whether the balance sheet is staying out of the way.

Primary KPI: Same-Store NOI Growth

This is the cleanest read on portfolio health. Same-store NOI bakes together the things management can actually control: rent growth, occupancy, tenant mix, and operating expenses. For 2025, Urban Edge guided to 3.0%–4.0% same-store NOI growth. If the company can deliver steady mid-single-digit growth over time, the strategy is working. If this metric stalls out or turns negative, it’s usually a sign that vacancy, concessions, or costs are winning.

Secondary KPI: Leasing Spreads

Leasing spreads show whether Urban Edge has real pricing power when leases roll. They measure the change between what a tenant used to pay and what the new tenant (or renewing tenant) is willing to pay for the same space. Urban Edge reported average cash spreads of 44% on new leases. When spreads stay strong, it often means the portfolio has embedded upside that hasn’t fully flowed into NOI yet. When spreads compress, it’s the first warning that demand is softening or that the “easy” rent resets are behind you.

Watch List:

- Occupancy rates (a healthy portfolio generally stays above 95% consolidated)

- Development pipeline yields (double-digit unleveraged returns are the bar for taking construction risk)

- FFO per share growth (the clearest way to see if execution is turning into per-share compounding)

- Dividend coverage ratio (you want FFO comfortably above the dividend, with room for volatility)

- Debt maturities and interest rates (refinancing discipline matters more when rates are higher)

- Cap rates on acquisitions and dispositions (the story to watch is whether the company keeps selling lower-yielding assets and buying higher-yielding ones)

XV. Epilogue & Final Reflections

So what does Urban Edge tell us about retail real estate in the 2020s?

First: “retail is dead” was never the full story. What died was a certain kind of retail—overbuilt, easily digitized, and dependent on discretionary trips. What held up, and in many markets actually strengthened, was the retail of daily life: groceries, pharmacies, services, off-price, and everything people still need close to home. The pandemic was supposed to be the final push toward an all-online future. Instead, it reminded everyone that for a big chunk of the economy, physical presence isn’t nostalgia. It’s infrastructure.

Second: spinoffs really can create value—when they’re done for the right reasons and executed with discipline. Vornado didn’t just dump a mismatched portfolio. It separated two different strategies that wanted different leadership, different investor bases, and different capital decisions. Urban Edge got the chance to be judged on its own merits, and Vornado got a cleaner story. That’s the spinoff promise when it works.

Third: even in “boring” real estate, execution is the product. A shopping center doesn’t run itself. Anchors fail. Tenant categories shift. Zoning fights happen. Capital markets turn. Urban Edge’s story is what happens when a team treats the work as a craft: lease aggressively, reinvest where it pays, recycle capital when the market hands you an advantage, and keep the balance sheet strong enough that you’re not making decisions under duress.

What would it take for Urban Edge to become a true compounder? Not a one-time pop, but year after year of per-share growth—driven by leasing spreads turning into NOI, redevelopment creating value, and capital recycling staying disciplined. The bar is simple and unforgiving: keep growing without taking the kind of risk that can erase a decade of progress in a single cycle.

As for what comes next, there are a few plausible endings. Urban Edge could keep doing what it’s been doing: stay public, keep upgrading the portfolio, and compound slowly for shareholders willing to be patient. It could become a target for a larger shopping-center REIT that wants deeper exposure to the Northeast. Or it could wind up in private hands, where redevelopment timelines and volatility matter less than long-run value creation.

But the real punchline is the one you noticed in that New Jersey parking lot at the beginning. The unglamorous places—the ShopRite run, the T.J. Maxx stop, the urgent care visit—aren’t just errands. They’re recurring demand. And in markets where land is scarce and new supply is hard, that demand can turn “unremarkable” strip centers into something quietly powerful: billions of dollars of irreplaceable real estate.

In this corner of the market, boring isn’t a flaw. It’s the feature.

XVI. Further Reading & Resources

Essential Company Documents: - Urban Edge Properties filings on SEC.gov (10-Ks, 10-Qs, proxy statements) - Vornado’s 2014–2015 spinoff paperwork (including Form 10 and S-11 materials) - Urban Edge Investor Day decks and presentations (uedge.com)

Industry Research: - Green Street Advisors research for third-party views on shopping-center REITs and NAV - Nareit (National Association of REITs) data and primers on REIT structure and sector trends - CoStar Group market reports for retail leasing and pricing context in NY/NJ and the broader corridor

Academic Context: - The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs (why street-level commerce works—or doesn’t) - The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein (the policy history behind suburbs, zoning, and who gets to live where) - MIT Center for Real Estate research on the future of retail real estate

Peer Company Filings: - Kimco Realty (KIM) investor presentations and supplemental packages - Regency Centers (REG) annual reports and supplemental disclosures - Federal Realty Investment Trust (FRT) quarterly supplementals

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music