TTM Technologies: The Story of America's PCB Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a factory floor in Syracuse, New York. It’s December 2025, and construction crews are putting the finishing touches on a 215,000-square-foot manufacturing facility—an investment that amounts to a $130 million bet on the future of American electronics manufacturing. Inside, engineers are preparing to install some of the most advanced printed circuit board production equipment ever deployed on U.S. soil. This plant is being built to produce ultra-high-density interconnect PCBs for the Department of Defense—boards so complex that only a handful of companies on Earth can make them.

The company behind this project is TTM Technologies. This Syracuse expansion is designed to support the mission-critical needs of defense customers, as demand grows for more capability in smaller, lighter, more efficient electronic packages. And there’s a twist: much of the underlying manufacturing know-how traces back to techniques first pushed at scale by smartphones and consumer electronics. Now those commercial innovations are being pulled into the defense industrial base.

That’s the lens for today’s story. TTM is North America’s largest PCB manufacturer, with trailing 12-month revenue of $2.78 billion as of September 2025—and one of the more improbable success stories in modern American manufacturing. Over the last few decades, more than 95% of PCB production moved to Asia. TTM didn’t just avoid getting swept away. It found a way to get bigger, more specialized, and more strategically important.

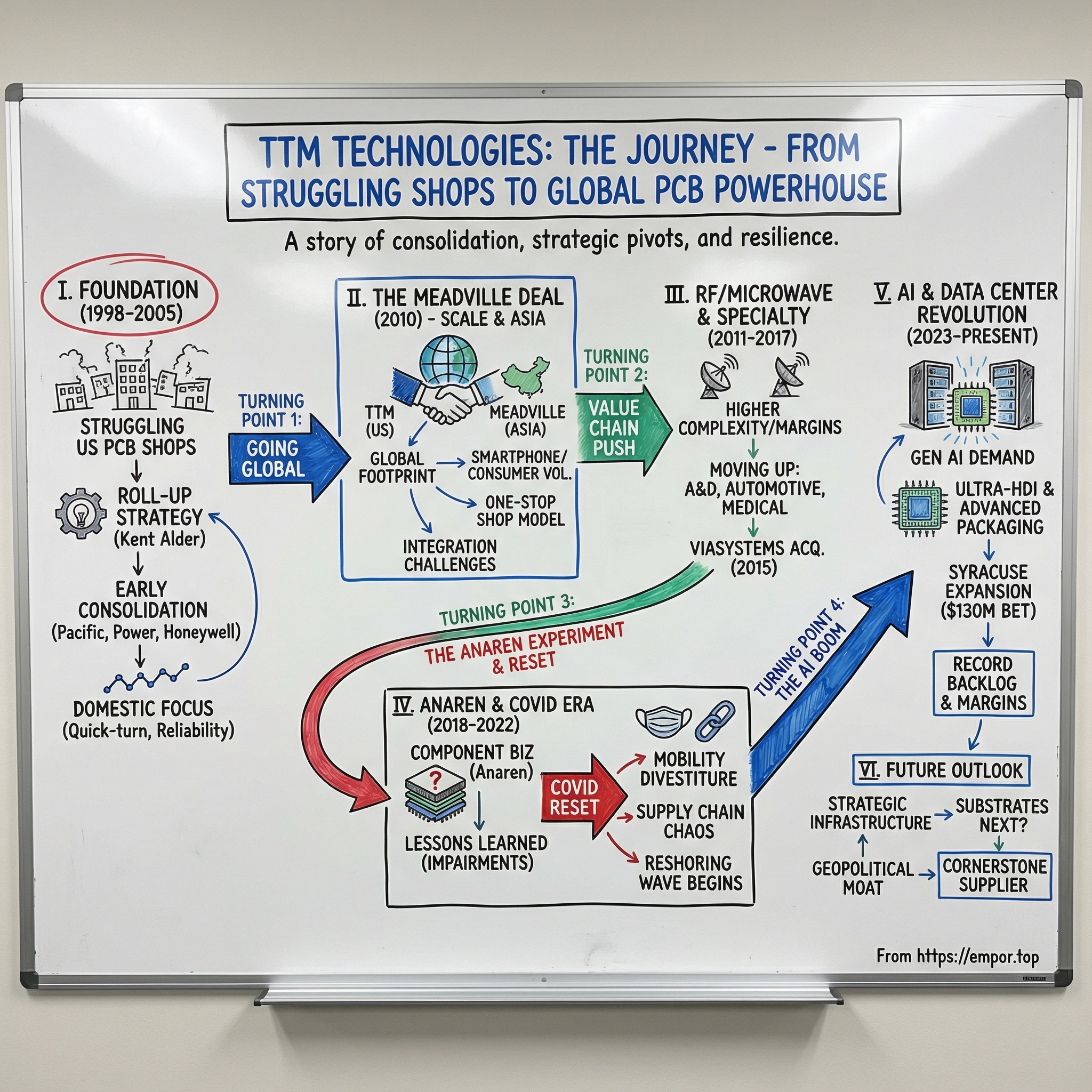

So here’s the question that drives everything: How did a roll-up of struggling PCB shops become the backbone of American high-tech manufacturing? The answer is a mix of disciplined M&A, a deliberate shift away from commodity work toward harder-to-replace technology, and a geopolitical backdrop that turned U.S.-based capacity from an expensive disadvantage into something closer to a national security necessity.

By late 2025, the results were showing up in the numbers. TTM had a record aerospace and defense program backlog of $1.56 billion. Its data center computing segment was also hitting record revenue and had grown to 22% of total sales. And in 2024, revenue grew 9.4%, helped by generative AI demand in Data Center Computing and continued strength in Aerospace and Defense.

This matters now because the world changed around the supply chain. Reshoring stopped being a slogan and started looking like industrial strategy. China+1 became a real procurement mandate. AI infrastructure spending created a surge in demand for high-end boards. And security concerns elevated companies like TTM from “just a supplier” to something much closer to strategic infrastructure.

We’re going to tell this story through five turning points: the Meadville deal that made TTM a global player, the push into RF/microwave that moved it up the value chain, the Anaren acquisition that tested how far vertical integration could go, the COVID-era reset that sharpened the company’s focus, and the AI-driven data center boom that is reshaping TTM’s growth trajectory.

II. The Printed Circuit Board: Foundation of Modern Electronics

Crack open almost any electronic device—your phone, an F-35’s flight computer, an MRI machine, or a server in the data center delivering these words—and you’ll find the same unsung hero: a printed circuit board.

PCBs don’t look like much. Often green, sometimes red or black, they’re easy to dismiss as “just the board.” But they’re the nervous system of electronics: the platform that holds components in place, routes signals, distributes power, and makes the whole machine behave like one coordinated system instead of a pile of parts.

At its core, a PCB is a layered sandwich. Thin sheets of copper are laminated onto insulating material, then etched into intricate pathways—traces and planes that act like roads for electricity. Components are mounted onto pads on the outer layers and soldered in place, which both locks them down mechanically and connects them electrically. That simple idea—print the wiring instead of hand-wiring every connection—unlocked reliable, repeatable electronics at scale.

The roots of the PCB stretch back further than most people think. In 1903, German inventor Albert Hanson described flat foil conductors laminated to an insulating board, even imagining multiple layers. Thomas Edison experimented in 1904 with chemical methods of plating conductors onto linen paper. But the modern printed circuit really took shape in the 1930s, when Austrian engineer Paul Eisler, working in the UK, built a radio using a printed circuit. World War II accelerated the underlying manufacturing techniques, and in 1948 the U.S. released the invention for commercial use. It still took time to become mainstream—printed circuits didn’t spread widely through consumer products until the mid-1950s, after the U.S. Army’s Auto-Sembly process helped industrialize how these boards were made.

Fast-forward to today and “a PCB” isn’t one thing. Rigid boards are still the workhorse, but the category has splintered into specialized, increasingly high-performance flavors: flexible PCBs that bend and fold inside tight enclosures; rigid-flex boards that combine durability with compact routing; high-density interconnect (HDI) boards with microscopic features for packing more connections into less space; RF and microwave circuits that can carry high-frequency signals measured in gigahertz; and substrate-like PCBs (SLP) that start to blur the line between traditional boards and chip packaging.

The market is growing, too. The printed circuit board industry is projected to rise from about $81 billion in 2025 to roughly $105 billion by 2030, driven by the same forces reshaping the rest of hardware: AI servers pushing denser HDI designs, electric vehicles adding power electronics and sensors, and 5G infrastructure demanding high-frequency materials.

But here’s the twist—the economic reality of PCBs has always been at odds with their importance. They’re foundational to everything electronic, yet they’ve been treated like commodities for decades. It’s a capital-intensive business where you have to keep reinvesting just to stay in the game. In the commodity segments, margins get squeezed and cycles can be brutal.

Over time, the industry split into two worlds. On one side: high-volume production, dominated by Asia, where the goal is to make huge quantities of nearly identical boards at the lowest possible cost. On the other: high-mix, low-volume manufacturing—North America’s niche—serving customers who need complexity, customization, and speed. Instead of millions of the same board, these customers want small runs, fast turns, and designs that are hard to build and even harder to qualify.

That split—volume in Asia, specialized quick-turn in the West—became the strategic terrain TTM would fight on. And once you see that terrain clearly, you can start to understand how TTM survived an industry collapse that wiped out so many others.

III. The American PCB Industry's Rise and Fall (1950s–1990s)

In 1960, the United States sat at the center of the PCB universe. American manufacturers—Motorola and IBM at the top, plus hundreds of smaller shops—built the circuit boards that powered the Space Race, Cold War defense programs, telecom networks, and the first wave of computing.

This was the golden age of American electronics manufacturing. Big, vertically integrated companies ran tight supply chains. Engineering teams sat close to the factory floor. Iteration cycles were fast because design and production lived in the same places. “Made in USA” wasn’t a branding exercise. It was shorthand for leadership.

Then globalization arrived, and the rules changed.

PCBs are a perfect storm of “critical but price-sensitive.” They’re labor-intensive, capital-hungry, and—especially in the lower-end segments—easy for customers to treat as interchangeable. Taiwan, and later China, combined lower labor costs with aggressive industrial policy and a willingness to build manufacturing capacity at scale. As shipping and communication improved, offshoring stopped feeling risky. It started looking inevitable.

Capital followed the gravitational pull. Investment moved away from U.S. facilities that couldn’t match Asian pricing, and the domestic base began to crack. Through the 1980s and into the early 1990s, shops closed, consolidated, or went bankrupt. The American PCB industry didn’t decline gradually. It got punched in the mouth, over and over, until most of it disappeared.

By the early 2000s, the outcome was stark: the U.S. share of global PCB production had fallen to roughly 4%, down from around 30% a few decades earlier, while China’s share climbed above half. The hollowing-out wasn’t just about PCBs—it mirrored what happened across electronics manufacturing more broadly—leaving only a few pockets of resilience, especially where defense and aerospace requirements effectively demanded domestic supply.

Offshoring wasn’t driven by one factor. It was a stack of reinforcing incentives: labor cost arbitrage, Asian government subsidies, looser or differently structured environmental regimes, and a financial era that celebrated “asset-light” strategies. Closing a domestic plant could lift near-term margins. Wall Street liked that story.

The bigger story—what it meant to push a foundational technology ten thousand miles away—barely registered. Supply chains were “optimized” for cost under an assumption that the world would stay stable, trade would stay open, and logistics would always work. That assumption held for a long time.

And then, slowly, the bill came due.

That’s the landscape TTM was born into: a battered, fragmented industry that most people had written off. And into that wreckage stepped Kent Alder with a contrarian idea. If PCBs were becoming commodity-like at the low end, maybe the move wasn’t to fight for scraps. Maybe the move was to buy the survivors, build scale, and climb into the parts of the market where complexity, speed, and trust mattered—and where customers couldn’t just swap you out for the cheapest bid.

IV. The Roll-Up Begins: Formation and Early Consolidation (1998–2005)

Kent Alder didn’t stumble into the PCB business. He’d spent decades inside it—first as president of Lundahl Astro Circuits in Logan, Utah starting in 1987, then as president and CEO of its successor, ElectroStar, from 1994. When ElectroStar was acquired by the Tyco Printed Circuit Group in 1996, Alder stayed on as a vice president. And then he left with a clear view of what was happening to the industry he knew so well.

He’d watched American PCB manufacturing splinter into hundreds of small, under-capitalized shops—too small to invest in next-generation equipment, too narrow to support big customers consistently, and too geographically concentrated to be resilient. On their own, most of these businesses were fighting a slow, losing battle. But Alder believed that stitched together—under one operating model, with shared capital and a broader customer base—they could become a real competitor again.

TTM Technologies, Inc. was born in 1998 in Redmond, Washington, when Alder acquired Pacific Circuits, Inc. A year later, after TTM acquired Power Circuits, Inc., the company moved to Santa Ana, California. The name wasn’t subtle: TTM stood for “time-to-market.” In a world where Asia could usually win on cost, Alder was betting that speed, responsiveness, and reliability could still win customers—and keep manufacturing closer to home.

The early playbook was consolidation, fast. Pacific Circuits and Power Circuits merged in 1999. Then, in 2000, TTM went public on NASDAQ under the ticker TTMI. The timing mattered. The IPO hit near the peak of the dot-com era, and that access to public-market capital gave TTM the ammunition it needed to keep buying.

The deals followed. In 2002, TTM acquired Honeywell Advanced Circuits, doubling in size. The next huge step came with the acquisition of Tyco Printed Circuit Group in 2006, which again doubled the business and pushed TTM into a new category—North America’s largest PCB product provider for aerospace and defense.

That Tyco deal is where the strategy starts to look less like a financial roll-up and more like an industrial repositioning. Aerospace and defense is the opposite of commodity PCB work. Programs run for years. Qualification requirements are brutal. Security and compliance aren’t optional. And customers care a lot more about performance and reliability than shaving pennies off a unit cost. It was exactly the kind of market where a U.S.-based manufacturer could still be indispensable.

None of this was easy. Every acquisition came with the messy reality of integration: different systems, different plant cultures, different process controls, and different customer expectations. You had to keep quality high while rewiring the organization underneath it. And in PCBs, where a defect can mean a failed missile test or a grounded aircraft, the margin for error is basically zero.

But the logic kept holding. Scale meant shared overhead. It meant procurement leverage. It meant the ability to invest in better equipment and spread that cost across a much larger revenue base. And it meant a broader customer portfolio, which mattered in an industry that could swing hard with every cycle.

By 2005, TTM had become the largest PCB manufacturer in North America. That sounds like winning—until you remember what “North America” meant in a business that had already migrated to Asia. The question hanging over the company was simple: could it stay relevant as a mostly domestic player, or did it need a global footprint to survive the next phase of the industry?

Alder and his team chose the global path—and that decision set up the most transformative deal in TTM’s history.

V. The Meadville Pivot: Going Global and Quick-Turn (2006–2010)

By 2009, TTM had won the North American title—and discovered how little that protected them. The growth engines of the PCB world were no longer defense avionics and industrial controls. They were smartphones, tablets, and consumer electronics. And those products weren’t just being assembled in Asia; their entire supply chains were being built there too.

Customers were starting to expect a global footprint as table stakes. If you couldn’t support builds in Asia, you were increasingly invisible. Worse, the Asian manufacturers TTM had once thought of as “low-cost commodity shops” were moving up the technology curve, inching into the same advanced territory TTM relied on for differentiation.

So TTM made a decision that would redefine the company: if you can’t beat them, join them.

On April 9, 2010, TTM announced it had completed a business combination with Meadville Holdings Limited’s PCB business. Overnight, this wasn’t just a North American consolidator anymore. The combined company became one of the largest PCB manufacturers in the world, with pro forma 2008 annual revenue of $1.35 billion.

TTM acquired the Hong Kong–headquartered Meadville Printed Circuit Group for $521 million, expanding its footprint in Asia and extending its reach into the kinds of PCBs that powered smartphones and tablets. The transaction was intricate: the equity purchase price was approximately $521 million, paid in a mix of cash and TTM common stock, implying an enterprise value of approximately $936 million.

As part of the deal, TTM issued 36.3 million shares. That dilution was meaningful. But so was the prize.

With Meadville in the fold, TTM roughly doubled in size and gained serious capability in advanced HDI PCBs used in smartphones and tablets—plus a manufacturing base in Asia that could support customers where their production was actually happening.

Meadville, established in the 1980s and headquartered in Hong Kong, had become one of the leading PCB manufacturers based in China, with a focus on high-end products. Its lineup spanned double-sided and multi-layer PCBs, HDI PCBs, and IC substrates. Beyond scale, Meadville marketed a “one-stop shop” model: broad manufacturing capability paired with services that made it easier for customers to move from design to production.

The strategic logic was clean. TTM could now offer an end-to-end, global path: quick-turn prototyping and high-mix, low-volume builds from U.S. facilities, then volume manufacturing from Asian plants when a product hit scale. This East-West split—speed and complexity in the U.S., scale in Asia—became the company’s defining operating model.

“We are excited about the combination as we build upon the success both companies have achieved independently over the years, and we look forward to a bright future together,” said Kent Alder, President and CEO of TTM. “With today’s close, TTM and Meadville have created a stronger, world-class PCB manufacturer with the scale, production capabilities, market breadth and expanded customer service ability to lead in today’s competitive global PCB business.”

Of course, a PowerPoint strategy and a working company aren’t the same thing. Integration meant reconciling different cultures, customer relationships, regulatory environments, and operating philosophies—while keeping quality high in a business where mistakes are expensive and reputations are fragile.

But the deal did what it needed to do: it made TTM global, and it made the company relevant in the center of gravity of electronics manufacturing again.

And once TTM had that global platform, the next question was obvious. Scale and footprint could keep you in the game. But in an industry that constantly tries to commoditize you, the only durable escape is to move up the value chain—into technology segments where fewer companies can compete.

VI. Zastera and RF/Microwave: Moving Up the Value Chain (2011–2014)

The Meadville acquisition gave TTM global scale. But scale, by itself, doesn’t save you from commoditization. The smartphone and tablet supply chain that Meadville plugged TTM into was a knife fight: aggressive competitors, constant price pressure, and margins that could vanish the moment capacity showed up next door.

If TTM wanted durable profitability, it needed a different kind of business—one where customers paid for performance, not just price. That pushed the company toward a corner of the PCB world where the physics are unforgiving and the supplier list is short: radio frequency and microwave.

RF and microwave boards aren’t just “more layers” or “tighter traces.” They have to carry signals at very high frequencies while keeping losses low, noise down, and timing precise. They also have to manage heat, survive harsh environments, and meet reliability standards that leave very little room for mistakes. That’s why these boards show up in defense radar, satellite communications, and other systems where failure isn’t an inconvenience—it’s a mission problem.

And economically, this niche behaves differently. Qualification cycles are long. Materials are specialized. Process control matters. Once a supplier is designed in and proven, they tend to stick. That combination—high technical barriers plus sticky customer relationships—is exactly what TTM needed.

So TTM started building RF and microwave capability through targeted acquisitions and investment. The goal wasn’t simply to add capacity. It was to accumulate the materials expertise, process technology, and engineering talent needed to manufacture high-frequency products reliably—and to help customers design them so they could actually be built at scale.

Right in the middle of this shift, the company’s leadership changed hands. In 2013, Tom Edman succeeded Kent Alder as president. In 2014, following Alder’s retirement, Edman became CEO.

The baton pass mattered because Edman’s resume matched the moment. He brought more than two decades of executive experience across the electronics industry in both the U.S. and Asia, and he most recently led the AKT Display Group at Applied Materials. He also came with a Yale undergraduate degree in East Asian Studies and an MBA from Wharton—an unusual blend of manufacturing depth, global context, and capital discipline.

Under Edman, TTM leaned harder into differentiation. The company invested in advanced capabilities, kept pursuing strategic acquisitions, and continued reshaping its customer mix toward markets that valued reliability, performance, and long program lives.

In 2015, TTM acquired Viasystems Group, Inc. for $950 million. The deal expanded TTM’s presence in aerospace and defense and marked its entry into automotive.

Automotive fit the same pattern TTM was increasingly drawn to: tough qualification requirements, long product lifecycles, and a willingness to pay for quality and consistency. And as cars packed in more electronics—on the path toward electrification and autonomy—the PCB content per vehicle was only going one direction.

By 2017, the arc was clear. TTM was no longer just a consolidator with global footprint. It was steadily climbing into higher-reliability, higher-complexity segments—backed by RF/microwave capability in North America and volume manufacturing in Asia.

But Edman wasn’t done. He had an even bigger swing in mind—one that would test how far TTM could stretch beyond boards, and whether “moving up the stack” into complete RF solutions would be a masterstroke or an adjacency trap.

VII. The Component Business Experiment: Anaren Acquisition (2018)

Anaren, Inc. wasn’t a PCB shop. It was something closer to the next layer up the stack: a U.S. manufacturer of high-frequency radio and microwave electronics. Founded in 1967 and headquartered in Syracuse, New York, Anaren built RF microelectronics, components, and assemblies for aerospace and defense customers, plus telecommunications.

In 2018, TTM bought it—and this was the biggest swing the company had taken to date.

TTM acquired Anaren for $775 million in cash, subject to customary closing adjustments. When the deal closed, TTM said the combined company would have delivered pro forma 2017 revenue of $2.9 billion. But the headline wasn’t just size. It was ambition. TTM was trying to evolve from “the company that makes the board” into a company that could help design, build, and ship RF subsystems that sit on top of that board.

The pitch was clean on paper: pair TTM’s manufacturing scale and PCB expertise with Anaren’s RF design talent and portfolio of proprietary RF components and subsystems for Aerospace & Defense and Networking/Communication. The timing also looked right. TTM expected rising spend on advanced radar in defense, and a wave of 5G infrastructure buildout on the commercial side.

“We expect that integrating our manufacturing strength with Anaren's RF engineering talent will enable us to deliver superior value-added solutions to our customers in Aerospace & Defense and our broader commercial markets. We also believe that the combination will result in meaningful synergies created by complementary capabilities that will benefit the customers and employees of both companies,” said Tom Edman, CEO of TTM.

Anaren had changed hands not long before. Veritas Capital acquired it in 2014 for $383 million, and four years later TTM paid $775 million. That jump in price signaled what TTM believed it was buying: not just revenue, but hard-to-build RF capability—and maybe, as with many competitive processes, some urgency in the bidding.

TTM also came in with a classic integration promise: $15 million in pre-tax, run-rate cost synergies expected within two years, and an expectation that the deal would be immediately accretive to non-GAAP earnings.

Historically, Anaren’s DNA was deeply defense-oriented. Early contracts included a microwave landing system for jetliners funded by the U.S. Department of Defense under FAA supervision, wideband microwave tracking receivers used in direction-finding systems, and DFD and ESM devices designed to help jets and ships detect, identify, and evade enemy radar. The Cold War arms race had been the company’s core growth engine.

But once the deal closed, the hard part started. Moving from “boards” to “complete RF solutions” wasn’t just a product expansion—it was a business-model expansion. Anaren’s world had more R&D content, more direct engineering-to-engineering customer engagement, and competitive dynamics that didn’t map neatly onto PCB manufacturing. Integration wasn’t only about aligning plants and systems. It required a real cultural shift.

Then the external catalysts that were supposed to make the math sing didn’t cooperate. The 5G buildout moved more slowly than many expected. Geopolitical tensions made the telecom market messier. And COVID disrupted timelines across the industry, including the integration itself.

By 2024, the story showed up in accounting. In the third quarter of 2024, TTM recorded a $44.1 million goodwill impairment charge related to the RF&S Components segment. In the fourth quarter of 2024, it recorded another $32.6 million impairment charge tied to the same segment.

Those impairments were the company’s way of admitting the deal hadn’t delivered what the original thesis promised. That doesn’t mean Anaren had no value—its RF expertise still broadened what TTM could offer—but it did underline a lesson that shows up again and again in industrial strategy: vertical integration is seductive, and it’s risky. Adjacent businesses can look perfectly complementary in a deck, yet still demand different muscles to run day-to-day.

TTM took the message. The next phase of its strategy would tilt back toward what it did best—core manufacturing strengths and differentiated PCB technology—rather than trying to become something entirely new in one leap.

VIII. COVID, Supply Chain Chaos, and the Reshoring Wave (2020–2022)

When COVID-19 hit in early 2020, TTM was already moving. The company was in the middle of one of the biggest strategic pivots since Meadville—shrinking its exposure to the most volatile parts of electronics and doubling down on the markets where trust, reliability, and long program lives matter.

In January 2020, TTM announced a definitive agreement to divest its Mobility business unit—specifically, four manufacturing plants in China—for $550 million in cash.

This wasn’t just portfolio pruning. Mobility was tied heavily to the cellular handset supply chain: seasonal, brutally cyclical, and constantly pressured on price. Selling it was designed to do three things at once: reduce exposure to that roller-coaster market, shift the company’s mix toward longer-cycle segments (with Aerospace & Defense remaining the largest end market after the deal), and free up capital for investment in the businesses TTM believed had real staying power.

In 2019, Mobility generated $556 million in revenue, $14.8 million in non-GAAP operating income, and $90.5 million in adjusted EBITDA. But the bigger takeaway was what the sale signaled: TTM was prioritizing Aerospace & Defense and Data Center Computing—segments with higher barriers to entry, tougher qualification requirements, and customers who value continuity more than the lowest bid.

Then the world changed.

The pandemic didn’t just disrupt supply chains; it rewired how customers thought about them. Having production capacity ten thousand miles away, concentrated in one country, stopped looking like “efficient globalization” and started looking like single-point-of-failure risk.

Overnight, TTM’s U.S. manufacturing footprint became more valuable—not because it was cheaper, but because it was there. Defense customers, who had always pushed for domestic sourcing, felt vindicated. Commercial customers started asking questions that would have sounded paranoid a few years earlier: What happens if the next shock closes ports again? What if U.S.-China relations deteriorate further? What if Taiwan becomes the flashpoint everyone fears?

And the policy backdrop began to tilt, too. Trade tensions and tariffs made imported PCBs more complicated. National security concerns around foreign electronics supply chains moved from white papers to procurement conversations. Even initiatives like the CHIPS and Science Act—aimed primarily at semiconductors—helped create momentum for rebuilding more of the broader electronics ecosystem at home, including boards.

TTM used that moment to push further into defense electronics. In 2022, the company acquired Telephonics Corporation from Griffon Corporation for approximately $330 million in cash.

Telephonics, founded in 1933, builds intelligence, surveillance, and communications solutions across land, sea, and air domains, supplying the U.S. and allied defense customers. TTM said it expected about $12 million in pre-tax, run-rate cost synergies by the end of 2024.

Strategically, Telephonics was “moving up the value chain” in Aerospace & Defense—but with the scars from Anaren still fresh. Instead of trying to reinvent the company, it broadened TTM’s defense footprint in a way that fit the direction of travel: more complete subsystems, including radar, Identification Friend or Foe (IFF), and communications solutions—built around the same core requirement that underpins so much of TTM’s differentiated business: reliability, security, and trust.

By the end of 2022, the shape of the new TTM was hard to miss. The company had exited a volatile, low-margin mobility business. It had reinforced its commitment to Aerospace & Defense with Telephonics. And it had positioned itself as a trusted domestic supplier at exactly the moment when “where it’s made” started to matter again.

Reshoring, in practice, still moved slower than the rhetoric. For many applications, the economics of Asian manufacturing remained overwhelming. But for mission-critical, security-sensitive electronics, domestic capability wasn’t a nice-to-have—it was a procurement requirement. In those lanes, TTM’s U.S. footprint could command real pricing power.

The pandemic years were still messy on the ground: labor shortages, material inflation, and volatile customer demand. But strategically, they clarified the mission. TTM came out of the chaos with a sharper identity—and a stronger position in the parts of the market that were becoming more important, not less.

IX. The AI/Data Center Revolution and Advanced Packaging (2023–Present)

Then came generative AI—and with it, the biggest demand shock for advanced circuit boards in decades.

Starting in 2023, the industry’s center of gravity swung hard toward data centers. Training and serving large language models meant building out enormous fleets of GPU-accelerated servers: dense racks pulling huge amounts of power, throwing off serious heat, and pushing signal integrity to its limits. And every one of those systems depends on PCBs that are no longer “just boards.” They’re high-layer-count, high-performance platforms that have to move data fast, manage thermals, and stay reliable under punishing loads.

That demand showed up quickly in TTM’s results. Revenue grew 9.4% in 2024, driven by generative AI in Data Center Computing and continued strength in Aerospace and Defense. The company also highlighted a record aerospace and defense program backlog of $1.56 billion and record revenue in data center computing, which had grown to 22% of total revenue.

“We delivered a strong quarter with revenues and non-GAAP EPS above the high end of the guided range. Revenues grew 14% year on year due to demand strength in our Aerospace and Defense, Data Center Computing and Networking end markets, the latter two being driven by generative AI,” said Tom Edman, CEO of TTM.

The timing of the AI wave couldn’t have been better for a company already leaning into high-end, security-sensitive electronics. The proposed Syracuse facility is positioned as a key contributor to the domestic microelectronics ecosystem, with a footprint planned to be adjacent to—and at least as large or larger than—TTM’s existing 160,000-square-foot RF/microwave and microelectronics facility in Syracuse. TTM expects the new site to bring disruptive capability for domestic production of ultra-HDI PCBs supporting national security requirements, and it has described it as the highest-technology PCB manufacturing facility in North America.

TTM is building the facility on approximately 23 acres adjacent to its existing production operation in the Town of DeWitt in Onondaga County. The company expects to invest up to $130 million and create an additional 400 good-paying jobs, bringing its Central New York workforce to 1,000. It will also receive a $30 million grant from the Department of Defense for the expansion.

The build moved from vision to concrete reality in 2024, with foundations, partial roofing, and elevator shafts completed. By February 2025, the steel erection phase was expected to be complete, with focus shifting to pouring concrete for the interior buildout and equipment installation.

This Syracuse project stands out because it’s not another acquisition—it’s one of TTM’s most significant organic investments in years. The facility is expected to be one of the largest PCB manufacturing sites in North America, designed around an advanced, highly optimized process intended to shorten lead times, speed delivery, and expand domestic capacity for ultra-HDI PCBs.

Operationally, momentum carried into 2025. Net sales in the second quarter of 2025 were $730.6 million, up from $605.1 million in the second quarter of 2024. Third quarter net sales were $752.7 million, compared to $616.5 million a year earlier. TTM also reported Q2 2025 gross margin of 20.9%, as strategic investments in HDI manufacturing and long-term contracts improved margin visibility.

And looming behind the whole AI buildout is the industry’s “holy grail”: substrates.

As semiconductor packaging evolves toward advanced 2.5D and 3D configurations, the substrate—the thin, ultra-precise interconnect layer between chip and board—becomes more critical, more complex, and more valuable. This is where the line between traditional PCBs and semiconductor packaging starts to blur, and where the best economics in the interconnect world tend to live.

TTM had been laying groundwork here for years. In 2019, it acquired intellectual assets and technology from i3 Electronics, Inc®, expanding its solutions offering to include substrate-like PCB (SLP) technologies.

But this is also where competition gets brutal. Asian leaders like Unimicron and Ibiden dominate high-volume substrates, with Unimicron reporting trailing 12-month revenue of $4 billion as of September 2025. TTM’s angle isn’t to out-Asia Asia on commodity scale. It’s to win in specialized, defense-relevant applications where location, trust, and qualification barriers matter—and where some pure-play Asian competitors simply can’t play.

Meanwhile, the AI infrastructure buildout kept pressing forward. Hyperscalers continued to announce massive data center investments, GPU shipments remained strong, and the hardware roadmaps kept getting more complex. The implication for TTM is straightforward: more AI compute means more demanding boards, more premium content per system, and more customers looking for suppliers that can actually deliver.

For investors, the question is whether TTM can turn that tailwind into durable, high-quality growth—capturing a meaningful share of the upside while keeping capital allocation disciplined, and avoiding the classic trap in manufacturing: expanding capacity only to watch margins get competed away.

X. The Business Model Deep Dive

TTM today runs the business through two primary segments: Printed Circuit Boards and RF&S Components. The PCB segment is the engine room. It contributes the majority of revenue and covers everything from the boards themselves to the services that surround them—layout design and simulation, plus testing.

Across those segments, TTM manufactures PCBs and radio-frequency and specialty (RF&S) components for a set of end markets that look a lot like a map of “things that can’t fail.” In 2023, aerospace and defense made up 45% of revenue. Medical and industrial contributed 17%, automotive 16%, data center computing 14%, and networking 8%.

That mix isn’t an accident; it’s the result of years of steering away from the most commoditized work. Aerospace and defense comes with long product cycles, painful qualification requirements, and a strong preference for domestic manufacturing. Data center computing—supercharged by AI—has surged into a major pillar. Together, they represent the core of what TTM is trying to be: a high-reliability, high-complexity supplier where performance and trust matter as much as cost.

TTM’s position in defense has been meaningful for a while. As of 2017, it was the largest supplier of PCBs to the U.S. military, primarily as a subcontractor. By 2020, the company had about 1,600 customers, and its five largest original equipment manufacturer customers (not in order) were Huawei, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Raytheon, and Bosch.

The company’s footprint is built to support that strategy. TTM currently has 15 specialized and integrated facilities—7 in the U.S. and 8 in China and Hong Kong—totaling approximately 4.3 million square feet of manufacturing space.

That geography reflects the strategic duality TTM has lived with ever since Meadville: domestic capacity for defense, quick-turn, and security-sensitive programs; Asian capacity for higher-volume commercial production. It’s less “either/or” than “both/and”—the ability to follow customers across regions while still keeping critical work close to home when it has to be.

The quick-turn advantage is one of the company’s most practical differentiators. When customers need prototypes or low-volume production in days instead of weeks, proximity and responsiveness matter. North American manufacturers have leaned into this niche, and TTM has made it a centerpiece: rapid iteration, small batches, and engineering support that high-volume Asian players can’t always match.

Technologically, TTM is also one of the leading global manufacturers in the HDI PCB market, known for a broad portfolio across telecommunications, aerospace, and defense. The heart of that capability is high-mix, low-volume execution and deep process expertise in sequential lamination and microvia manufacturing. Put simply: these are the techniques that enable dense, complex boards—and they’re hard to do consistently at high yield. TTM’s pitch is that it can take a program from design through fabrication and assembly, then scale production across its global footprint as needed.

But none of this is a free lunch, because the PCB business is famously capital-intensive. Staying competitive means constant reinvestment in equipment, materials handling, and process development. When end markets swing—and they always do—overcapacity shows up quickly, and margins can get squeezed just as fast.

Even so, the company has shown that mix and execution can move the needle. In the fourth quarter of 2024, adjusted EBITDA was $108.7 million, or 16.7% of sales, compared to $80.9 million, or 14.2% of sales, in the fourth quarter of 2023.

That improvement is the strategy becoming visible in the financials: more differentiated work, better positioning, and tighter operations. The harder question is durability—because sustaining margin expansion in this industry requires TTM to keep doing three things at once: stay ahead on technology, keep improving the customer mix, and run the factories with relentless discipline.

XI. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

Breaking into advanced PCB manufacturing isn’t like opening a new machine shop. In the segments that actually matter to TTM—Aerospace and Defense, medical devices, and advanced telecom—the barriers are steep by design. A modern, advanced PCB facility can cost $100 million or more. And even after you’ve written that check, you still have to earn your way onto the approved vendor lists, which can take years of qualification work and relationship-building.

Aerospace and defense adds another layer of friction. ITAR compliance, security requirements, and customer qualification processes create a maze that’s hard to shortcut. Once you’re in, you tend to stay in—because no one wants to re-qualify a new supplier unless they have to.

Still, the threat isn’t zero. Chinese government subsidies have a track record of creating manufacturing capacity fast, across industry after industry. That kind of state-backed competition is real—even if it’s structurally disadvantaged in the most security-sensitive programs where “trusted” status matters as much as technical capability.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Even the best PCB manufacturer is only as good as its materials. TTM depends on specialized inputs—copper foils, laminates, and high-frequency substrates—sourced from a relatively concentrated group of suppliers. In certain categories, especially high-frequency laminates, there just aren’t many viable alternatives.

TTM’s scale helps: it can negotiate better than a small shop can. But when advanced materials get tight, leverage shifts quickly toward the supplier, and flexibility shrinks right when customers are demanding more capacity.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

On the other side of the table, TTM sells to customers who know exactly what they’re doing. Large OEMs—names like Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon—have sophisticated procurement teams and strong incentives to push pricing down, especially when the product starts to look even slightly interchangeable. Many can also dual-source, which gives them negotiating power even when they’re happy with TTM’s performance.

The counterweight is switching costs. In aerospace, defense, and other high-reliability applications, once TTM is designed into a program, replacing it can become slow, expensive, and risky. That stickiness provides real protection. But buyers rarely give up leverage entirely—they’ll keep the possibility of multi-sourcing on the table as a constant pressure valve.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

For most electronics, there’s still no true substitute for a PCB. It remains the default, proven way to connect components, route signals, and distribute power.

The longer-term question is whether the boundary shifts. Advanced packaging and substrate technologies are evolving fast, and in some architectures they can absorb functions that used to live on the board. Chiplet designs and more sophisticated substrate packaging blur the line between “PCB” and “semiconductor packaging”—not an immediate replacement, but a meaningful directional threat over time.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

The rivalry is brutal, because this is a global industry with capable players everywhere. On the PCB side, TTM competes with manufacturers like Unimicron Technology, Sanmina Corporation, Shennan Circuits, and WUS Printed Circuit. In RF systems and defense electronics, the competitive set includes BAE Systems, Mercury Systems, Cobham, and Thales Group.

In high-volume production, Asian competitors often have the edge on scale and cost. So the fight shifts to where TTM can differentiate: technology, speed, location, and certifications. Commodity segments devolve into price wars. Advanced applications offer more breathing room—but even there, any moat tends to be temporary unless you keep investing and staying ahead.

XII. Strategic Analysis: Hamilton's 7 Powers

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

TTM is the largest PCB manufacturer in North America, but it’s still a mid-sized player next to the Asian giants. It ranks among the world’s top five PCB manufacturers by revenue, yet the gap in global scale is real. The good news is that scale still buys you meaningful advantages—better purchasing leverage, the ability to spread R&D and overhead across more volume, and the resources to keep investing through cycles. The catch is that this isn’t a winner-take-all market. You don’t need to be the biggest company on Earth to win the customers TTM cares about. In many cases, regional scale is enough.

2. Network Economies: NONE

There are no network effects in PCB manufacturing. A circuit board doesn’t become more valuable because other people are also buying circuit boards. Each customer relationship stands on its own, and each order has to be earned on performance, price, and reliability—not on adoption momentum.

3. Counter-Positioning: EMERGING

This may be TTM’s most important emerging advantage. Being a “trusted American supplier” creates a lane that certain Chinese competitors simply can’t enter, regardless of their technical capability. Security concerns, geopolitics, and reshoring pressure all tilt demand toward suppliers with U.S.-based capacity and the right compliance posture. But it’s not a permanent force of nature. If tensions ease or policy support fades, the advantage could shrink.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

In aerospace, defense, and medical, switching suppliers is slow and painful. Qualification cycles can take 6 to 18 months, and once a board is designed into a program, it becomes embedded in test processes, documentation, and manufacturing workflows. That creates real stickiness. The switching costs are highest in defense and other safety-critical applications, where requalification is expensive, time-consuming, and carries real risk.

5. Branding: LOW

TTM doesn’t have consumer brand power, because it doesn’t sell to consumers. Nobody buys a smartphone—or funds a fighter jet—based on who made the PCB. What does matter is reputation inside the customer: among OEM engineers and procurement teams who remember who hit the schedule, who held yield, and who didn’t create a painful quality incident. That helps win programs, but it doesn’t usually create outsized pricing power by itself.

6. Cornered Resource: LOW-MODERATE

TTM has some proprietary processes and IP in RF and advanced technology, and it benefits from accumulated engineering know-how. But talent can walk out the door. The more durable angle is that U.S. manufacturing capacity—especially for advanced, security-sensitive work—is getting scarce enough to look like a quasi-cornered resource. Certifications and security clearances add another barrier that competitors can’t instantly replicate.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

A lot of TTM’s advantage is operational. Over time, it has built deep manufacturing know-how and process discipline, and its quick-turn capability depends on an organization that can move fast without breaking quality. The integration of design support, engineering, and manufacturing adds value that pure-play, low-touch manufacturers can struggle to match. That said, none of this is magical. Given enough time and capital, competitors can copy process improvements—especially in the less differentiated parts of the market.

Overall Power Assessment:

TTM has moderate competitive power, anchored in switching costs, emerging counter-positioning, and regional scale. Its strongest footing is in aerospace and defense, advanced technology, and quick-turn applications. Its soft spot remains the commodity, high-volume, price-sensitive work where the industry tends to compete margins down. The strategic mandate is clear: keep climbing the value chain, and make the most of geopolitical tailwinds while they’re still blowing.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

The bull thesis is that TTM is catching a rare alignment of tailwinds—and it happens to sit right where they intersect.

Start with geography and politics. Reshoring and “friend-shoring” don’t just make for good speeches; they create real demand for domestic, trusted manufacturing capacity, especially in defense and other security-sensitive programs. Add in the AI data center buildout, which is pushing the industry toward ever more complex, high-layer-count boards. Layer on rising defense spending in a world that feels less stable by the quarter. In that environment, a supplier that can deliver advanced HDI, RF, and increasingly substrate-like capability—while also meeting U.S. security and qualification requirements—has a real shot at sustained, higher-quality growth.

If that plays out, the payoff isn’t only revenue growth. It’s mix improvement and margin expansion, because the most defensible parts of TTM’s portfolio are the ones with the highest technical barriers and the stickiest customer relationships. Bulls also point to continued consolidation: TTM can keep acquiring, or it could eventually become an attractive acquisition target itself as a scaled, strategically relevant platform.

That optimism has shown up in market commentary. Analysts raised price targets to $65, pointing to TTM’s leadership in AI infrastructure. The same notes also flagged the obvious execution risks—new-facility ramp inefficiencies and the possibility of further goodwill impairment. In other words: the upside case depends on TTM converting demand into durable margins, not just shipping more boards.

Supporters would argue the company is already proving it can do that. TTM said it is having the strongest first half of any year in its history when you look at revenue growth and margins together, and it’s doing it with a solid balance sheet to support future growth.

Then there’s valuation. Compared to semiconductor equipment or advanced packaging companies—businesses with overlapping end markets and many of the same tailwinds—TTM trades at a much lower multiple. Bulls see that gap as an opportunity: if margins expand and the company keeps executing, the stock could earn a multiple re-rating.

Bear Case:

The bear case starts with a simple claim: even great execution can’t fully escape a structurally hard industry.

PCB manufacturing is capital-intensive and cyclical. Pricing pressure never goes away, and commoditization is always trying to creep up the stack. Customer concentration can amplify the swings—one delayed program, one design loss, or one procurement shift can dent revenue and squeeze margins. And in high-volume production, Asian competitors still have the scale and cost structure that’s difficult to match.

Bears also question how much reshoring is real versus rhetorical. Many customers still optimize for cost, and for a lot of commercial electronics, the economics of Asian manufacturing remain compelling. On the AI side, the risk is that what looks secular may still be cyclical. If hyperscaler spending slows, demand can soften quickly—and capacity expansions that looked smart at the peak can become painful on the way down.

Technology is another long-term worry. As advanced packaging evolves, some functionality that used to live on traditional PCBs could migrate closer to the chip, potentially disintermediating parts of the board ecosystem. Meanwhile, U.S. environmental and labor costs can make domestic manufacturing tougher over time, especially if policy support fades or demand mix shifts back toward price-sensitive work.

Finally, there’s execution risk—because TTM’s strategy has included big bets. Its M&A track record is mixed, and the Anaren integration is the cautionary example: adjacencies can look perfect on paper and still underdeliver in practice.

Put all that together, and the valuation argument can flip. The stock may be cheap not because it’s overlooked, but because the market is pricing in those structural challenges. In that framing, “cheap” isn’t a catalyst—it’s a warning label.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Two metrics, in particular, tell you early whether the bull or bear narrative is winning.

First, Aerospace & Defense backlog trends. The $1.56 billion A&D program backlog is unusually valuable because it provides visibility before revenue shows up in reported results. If backlog grows, it’s a sign the most defensible part of the business is strengthening; if it stalls or shrinks, it’s often an early warning.

Second, data center computing revenue as a percentage of total. At 22% of revenue, this tracks how exposed TTM is to the AI infrastructure wave—and whether it’s actually capturing that demand. Sustained growth supports the bull case. A slowdown could mean the market is cooling, competition is biting, or TTM is getting displaced where it matters most.

XIV. Lessons for Founders and Investors

The "Boring But Critical" Opportunity

TTM is a reminder that some of the most important companies in the economy are essentially invisible. Outside the electronics world, almost nobody knows the name. Yet TTM’s boards sit inside defense systems, data center hardware, and medical devices—the kind of gear that has to work, every time. Businesses like this rarely get celebrated, but they can compound for a long time because they sit underneath everything that does get the headlines.

Consolidation as Strategy

When Kent Alder founded TTM, he looked at a fragmented, struggling industry and didn’t see a graveyard—he saw a roll-up. Consolidation can work when scale actually matters and when the integration is real, not just financial engineering. TTM’s best acquisitions weren’t just about getting bigger; they were followed by the unglamorous work of standardizing operations and capturing the synergies that justified the deal in the first place.

Technology Treadmill

In capital-intensive manufacturing, “standing still” is just a slower form of going backwards. TTM’s arc—from quick-turn to RF/microwave to advanced HDI—shows what it takes to stay relevant as segments commoditize and customer requirements ratchet up. The Syracuse expansion fits that pattern. It’s not growth for growth’s sake; it’s the kind of investment you make because the market keeps moving, and you either build the capability or you eventually lose the work.

Geopolitics as Moat

National security concerns reshaped the economics of TTM’s U.S. footprint. What used to look like a cost disadvantage became a selling point: trusted, domestic capacity. But it cuts both ways. When policy and procurement preferences support your model, the payoff can be huge. When your advantage depends on that support, you’re also exposed to policy risk—what politics rewards, politics can also reverse.

The Adjacency Trap

The Anaren deal is a clean case study in why adjacencies are so tempting—and so dangerous. Vertical integration sounds great in a strategy deck, but in practice it often means stepping into a different business with different economics, different customer expectations, and a different culture. TTM learned that the hard way, and the lesson shows up in what came after: a sharper emphasis on the company’s core strengths rather than trying to become something entirely new overnight.

Cyclicality and Timing

PCB manufacturing has always swung between overcapacity and shortage. That’s the nature of a capital-heavy industry tied to volatile end markets. Surviving—and winning—in that environment takes patience, a balance sheet that can handle downturns, and the ability to tell the difference between a cyclical dip and a permanent loss of relevance. TTM’s endurance through multiple downturns is, in many ways, the quietest proof that discipline matters.

The Reshoring Debate

There’s still a gap between reshoring as a narrative and reshoring as a measurable reality. Announcements are easy; sustained volume is harder. TTM is positioned to benefit where domestic sourcing is truly required, but it’s worth staying skeptical about how fast and how broadly “Made in America” shifts from talking point to default behavior.

Hidden Champions

TTM also fits a broader investing pattern: hidden champions that make modern life possible without ever becoming household names. Their products don’t get marketed to consumers, but they’re everywhere—in smartphones, defense platforms, and hospital equipment. For founders, it’s a lesson in building durable relevance in the supply chain. For investors, it’s a reminder that some of the most attractive opportunities are the ones you only notice if you’re willing to look behind the glossy brands and into the infrastructure underneath.

XV. Epilogue: What's Next for TTM?

In September 2025, TTM announced a leadership transition. Edwin Roks, Ph.D. was appointed the company’s new President and CEO, effective September 2, 2025. He succeeded Thomas T. Edman, who had led TTM as CEO since 2014 and retired as previously disclosed.

Roks arrived with deep operating experience across aerospace, defense, and industrial electronics. Most recently, he served as CEO of Teledyne Technologies Incorporated until April 2025. At Teledyne, he was credited with helping drive growth in digital imaging, pushing technology advancement across the portfolio, and integrating the company’s largest acquisitions—exactly the kind of pattern recognition that matters at TTM, where strategy has often been as much about execution as vision.

This moment also marked the closing of an older chapter. Kent Alder founded TTM in 1998, starting with a small operation and scaling it into a global electronics manufacturing leader. Along the way, he established the company’s cultural foundation—integrity, honesty, clear communication, and performance excellence—and pushed the roll-up strategy that gave TTM the scale to survive an industry that didn’t want mid-sized, undercapitalized players. Alder retired from the board in May 2025, ending an era that began with one acquisition and turned into a platform.

Looking forward, the biggest prize—and the biggest test—remains substrates and substrate-like technology. That’s where the value in the interconnect world is migrating, and where the most formidable competitors are Asian packaging giants with years of head starts. The Syracuse facility should offer early evidence of how far TTM can push the frontier domestically, but winning here won’t be a one-cycle story. It will require sustained investment, high-yield execution, and the patience to climb a learning curve that is expensive even when it’s going well.

M&A is still on the table too. TTM could keep acquiring, pulling in capability in advanced packaging or RF systems. It could also become the one being acquired—a strategically attractive asset for a larger player that wants domestic manufacturing capacity and deep defense credentials. The company has shown more discipline in capital allocation in recent years, but in an industry that keeps consolidating, strategic combinations remain a live possibility.

And then there’s the question hanging over the entire thesis: is the U.S. manufacturing renaissance real, or is it mostly narrative? The answer is probably somewhere in the messy middle. The tailwinds are real—national security, supply chain risk management, and customers that increasingly want geographic diversity. But so are the counterforces: the economics of Asian manufacturing are still hard to beat in many commercial applications. TTM’s future won’t be decided by a sweeping reshoring wave. It will be decided by whether its differentiated positioning—trusted, fast, and capable at the high end—stays scarce and valuable.

Technology won’t pause, either. Glass substrates, 3D printing, new materials, and evolving packaging architectures will keep reshaping what “interconnect” even means over the next decade. If TTM stays at the frontier, it stays relevant. If it falls behind, the industry will not wait for it to catch up.

So what could create the next true inflection point—something on the scale of Meadville, RF, or the COVID reshoring reset? It could be geopolitics, if escalating tensions accelerate domestic sourcing requirements. It could be technology, if a breakthrough makes today’s leading processes obsolete. It could be M&A, if a transformative deal changes the company’s scope again. You can’t predict which one will happen. You can only build a company positioned to benefit when it does.

That’s why TTM is such a fitting final note for the hardware renaissance. When engineers design the next generation of defense systems, data centers, and medical devices, they still need someone to turn those designs into physical reality—on time, at yield, and at the level of reliability the mission demands. It’s unglamorous work, invisible to end consumers, and often underappreciated by markets. But it’s essential. And over more than two decades, TTM has shown it can do it—and keep doing it—through technology shifts, industry cycles, and the slow return of manufacturing to the strategic center of the world.

XVI. Outro & Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—into the mechanics of the PCB industry, the geopolitics behind reshoring, and the technology arc that’s blurring the line between boards and packaging—these are the best places to start.

Top 10 Resources:

- TTM Technologies investor presentations and 10-K filings (2005–present)

- IPC (Association Connecting Electronics Industries) industry reports

- "Chip War" by Chris Miller (semiconductor ecosystem context)

- Prismark Partners PCB industry market research reports

- "The New Grand Strategy" by Mark Zachary Taylor (reshoring and industrial policy)

- Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) reports on supply chain security

- SemiAnalysis and semiconductor industry newsletters (for advanced packaging context)

- MIT Industrial Performance Center papers on U.S. manufacturing competitiveness

- "The Printed Circuit Assembler" – Industry trade publication and historical archives

- Paul Eisler biography from AT&S (PCB invention history)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music