Turning Point Brands: From Big Tobacco Castoff to Niche Tobacco Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a convenience store counter somewhere in the American heartland. Next to the lottery tickets and energy drinks is a small, unassuming display of bright orange rolling papers—stamped with the profile of a French soldier lifted straight out of an 1850s battlefield poster. That brand is Zig-Zag. It’s been part of American smoking culture since before the Civil War.

And the company that controls Zig-Zag in the U.S. today? Most investors couldn’t name it.

Turning Point Brands is a public company, traded under the ticker TPB. In 2024, it generated about $361 million in revenue, up roughly 11% from the year before. By late 2025, its market value had flirted with the billion-dollar mark. Yet it’s still largely invisible—dwarfed in attention by tobacco titans like Altria and Philip Morris, whose market caps live in an entirely different universe.

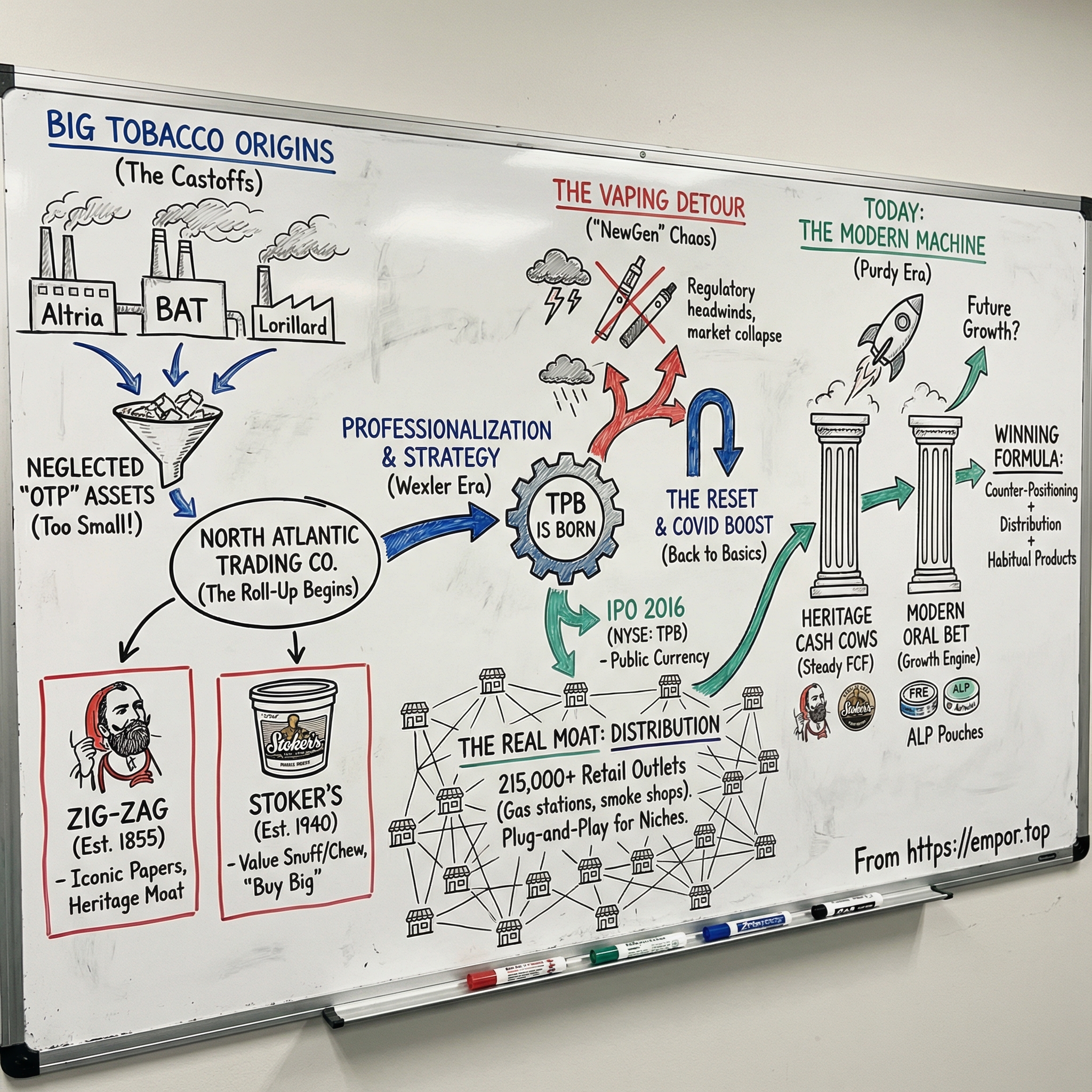

So here’s the central question: how did a twice-discarded bundle of “non-strategic” tobacco assets—the exact stuff Big Tobacco didn’t want—turn into a standalone company producing over $100 million a year in EBITDA?

The answer is wonderfully counterintuitive. While the major tobacco companies narrowed their focus to the biggest, most scalable profit pools—primarily cigarettes—Turning Point leaned into the “small” categories: cigars, moist snuff, chewing tobacco, rolling papers, and smoking accessories. The niches the giants didn’t bother defending became the whole game.

That focus mattered even more as nicotine kept evolving. Cigarettes kept sliding. Smokeless grew. New formats—like pouches—started rewriting the playbook. And Turning Point, because it lived in the corners of the category map, kept finding places to win.

This story is a tour through roll-ups and LBOs, through declining-but-still-profitable markets, through heritage brands that survived because somebody finally treated them like the main event instead of the leftovers. It’s also a case study in capital allocation in mature industries: when to buy, when to sell, when to chase the shiny new thing, and when to walk away.

Today, TPB’s products sit in more than 215,000 retail outlets across North America. Gas stations in Texas, smoke shops in Brooklyn—places where shelf space is everything. And that shelf space is the moat. The majors often can’t justify fighting for these slots because they’re too small to move the needle for a giant. But for a focused specialist, they’re big enough to build a very real business.

A few themes will keep coming up: distribution as destiny in physical retail; the stubborn durability of habitual-consumption products; regulation as both a threat and a barrier to entry; and the constant balancing act between milking cash flows and trying to grow.

If you care about sin stocks, special situations, or just how overlooked businesses quietly compound for years while everyone’s watching the headlines elsewhere, Turning Point Brands has a lot to teach.

II. The Heritage: Brown & Williamson and the Big Tobacco Machine (1950s–2000s)

To understand where Turning Point Brands came from, you have to start in the old tobacco heartland.

In 1894, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, George T. Brown and Robert L. Williamson—brothers-in-law from prominent tobacco families—formed a partnership to make chewing tobacco. They incorporated as Brown & Williamson Tobacco Company in 1906. Early on, B&W wasn’t a cigarette powerhouse. It was a specialist, building its business on products like Bloodhound and other sun-cured and chewing tobaccos—things sold by the plug, the pouch, and the habit.

That specialty focus worked. Through the early 1900s, B&W built real presence in chewing, loose-leaf, and pipe tobacco. One deal in particular became foundational: in 1925, B&W bought the Sir Walter Raleigh pipe tobacco brand, which had been marketed regionally since the 1880s by J.G. Flynt Tobacco Company. B&W took it national. Sir Walter Raleigh became one of the company’s signature names—proof that, even then, distribution and branding were the game.

Then came the step-change.

In 1927, British American Tobacco reentered the American market by acquiring Brown & Williamson. For BAT—based in London—this was the on-ramp to the world’s biggest, fastest-growing cigarette market. For B&W, it meant capital, scale, and ambition. BAT expanded the company as Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation, and by 1928 and 1929 it had built extensive manufacturing facilities in Louisville, Kentucky. B&W shifted its headquarters there, and from that point forward, it rode the cigarette wave.

Over the decades, B&W developed and acquired a portfolio that became woven into American smoking history. Kool rose to dominate menthol cigarettes. Viceroy, Raleigh, Carlton, and later Lucky Strike (through the American Tobacco Company deal) filled out the lineup. At its peak, B&W held roughly 16 to 18 percent of the U.S. cigarette market—good for third place among American manufacturers.

But the foundation under the entire industry was cracking.

The 1964 Surgeon General’s report tied smoking to lung cancer and lit the fuse for decades of public-health pressure, regulation, and lawsuits. By the 1990s, the threat turned existential: state attorneys general began suing tobacco manufacturers to recover the healthcare costs of smoking-related illness.

That wave crested in 1998 with the Master Settlement Agreement. On November 23, 1998, the MSA was entered into between the attorneys general of 46 states and the four largest U.S. tobacco companies at the time: Philip Morris, R.J. Reynolds, Brown & Williamson, and Lorillard (along with the District of Columbia and five U.S. territories as part of the broader settlement). In exchange for the states dropping their suits, the tobacco companies agreed to sweeping marketing restrictions and to make annual payments to the states in perpetuity. The deal committed the industry to $206 billion to be paid over 25 years.

Just as important as the money was the new rulebook. The MSA clamped down on advertising, marketing, and promotion. It prohibited tobacco advertising that targeted people under 18, eliminated cartoons in cigarette ads, and largely wiped out outdoor, billboard, and public-transit cigarette advertising. It also restricted the use of cigarette brand names on merchandise.

For Big Tobacco, this changed the strategic calculus overnight. With settlement payments looming and marketing constrained, focus became survival. Every management hour, every marketing dollar, every distribution relationship had to be aimed at the core cigarette business—where the volume, the margins, and the stakes were biggest.

And that’s where “Other Tobacco Products,” or OTP, entered the story.

Like its competitors, B&W had accumulated a grab-bag of smaller product lines over the decades: loose-leaf chewing tobacco, moist snuff, rolling papers, cigars, pipe tobacco. They generated profit, but next to cigarettes they were rounding errors. Worse, they demanded attention—manufacturing decisions, brand stewardship, regulatory compliance, sales effort—at exactly the moment the core business needed everything.

So the logic inside the big companies became straightforward: divest the small stuff, focus on cigarettes, and concentrate capital and talent where it mattered most.

What they didn’t fully appreciate was the twist that would eventually create Turning Point Brands: those “non-strategic” assets weren’t bad businesses. They were just the wrong size for giants. For someone smaller—and more focused—they were exactly the right size.

III. The First Carveout: North Atlantic Trading Company (2000s)

The story of Turning Point Brands really begins not in Louisville, but in a New York City office—and with a particular kind of entrepreneur: someone who looked at Big Tobacco’s “other” businesses and saw a portfolio, not a distraction.

That entrepreneur was Thomas Helms, Jr. He wasn’t a lifelong tobacco exec in the traditional sense. He came up through consumer products, starting at Revlon in the 1960s and spending years in sales and marketing before running Revlon’s Etherea Cosmetics and Designer Fragrances Division. But that background mattered. Helms understood brands, shelf space, and repeat purchase behavior—and he realized tobacco’s “Other Products” segment was full of exactly that: loyal customers, habit-driven buying, and underloved brands.

In 1988, he formed what would become National Tobacco Corporation with a simple mission: acquire and operate tobacco brands that the majors no longer considered strategic. Over time, the company ended up anchored in two places at once. Helms stayed in New York City to manage the business. Operations leaned on Louisville, Kentucky, where National Tobacco took over Lorillard’s manufacturing facilities and produced loose-leaf chewing tobacco under various labels.

The big step came in 1997, when National Tobacco acquired North Atlantic Trading Co. Inc. North Atlantic itself had only been around since 1993, created by investors for one main reason: to buy Zig-Zag’s U.S. distribution rights from UST Inc. for $39 million. Funding that deal wasn’t small-ball. To finance the Zig-Zag purchase and restructure debt, National Tobacco put together a $300 million high-yield bond issue and loan package.

And once Zig-Zag was in the mix, it quickly became the crown jewel.

Zig-Zag wasn’t just a product—it was heritage in a little orange pack. The brand was founded in Paris in 1855 by Maurice and Jacques Braunstein. In 1882, the company built the Papeterie de Gassicourt, a cigarette paper production plant near Mantes-la-Jolie. In 1894, they invented a manufacturing process called “interleaving,” where papers stack in an alternating pattern—what gave the brand its name: Zig-Zag.

By 1900, Zig-Zag was winning awards, including a gold medal at the Universal Exposition in Paris. Growth pushed the business to expand again in 1919, opening a new mill in Thonon-les-Bains.

Then there’s the iconography. Zig-Zag’s famous “Le Zouave” logo depicts a French North African soldier, tied to a legend from the Battle of Sebastopol: a Zouave breaks his pipe, improvises by rolling tobacco in paper from a gunpowder bag, and effectively invents the rolling paper in the moment. Whether or not the story is literally true, it doesn’t matter—because in consumer products, mythology is often part of the moat. That soldier has been Zig-Zag’s symbol for more than a century.

In the U.S., Zig-Zag had been a fixture since its introduction in 1938. Under North Atlantic, it became the number-one selling domestic RYO cigarette paper brand. North Atlantic estimated its domestic market share at 49 percent or higher.

This is where the business model snaps into focus. North Atlantic wasn’t trying to invent new nicotine. It was buying entrenched brands in habit-driven categories where “switching costs” are psychological and sensory: taste, ritual, familiarity. Rolling paper users tend to buy what they always buy. Dippers and chewers do too. Even if the category is flat or shrinking, a well-positioned brand can still throw off strong margins—and, with the right distribution, even take share.

Structurally, North Atlantic Trading Company Inc. was a New York City-based holding company overseeing several tobacco-focused subsidiaries. National Tobacco Company, L.P. was the third-largest loose-leaf chewing tobacco company in the United States, with Beech-Nut as its flagship brand. North Atlantic Operating Company, Inc., under an agreement with Bollore, S.A., sold cigarette papers, tubes, loose tobacco, and cigarette-making machines under the Zig-Zag name.

The portfolio went well beyond papers. It included Beech-Nut, a premium chewing tobacco brand dating back to 1897, plus other loose-leaf products. It also included Stoker’s, a brand with roots going back to 1940 that made its name by embracing bigger-bag value—famously, being first to introduce 8 oz. bags.

In November 2003, North Atlantic expanded that smokeless footprint by acquiring Dresden, Tennessee-based Stoker, Inc. for $22.5 million. The deal brought in a brand that positioned itself as value in both chewing tobacco and moist snuff, built around a straightforward promise: “Buy Big. Save Big.” Larger formats, fair pricing, and a loyal customer base that didn’t need to be persuaded—it just needed to be served consistently.

From the outside, this all looked like a sleepy corner of tobacco. But inside the business, it was exactly the kind of machine that investors love: unglamorous, disciplined, distribution-driven, and cash-generative. While the public markets obsessed over cigarettes and headline regulation, North Atlantic quietly built relationships, managed decline with rigor, and assembled the pieces that would eventually become Turning Point Brands.

IV. The Inflection Point: The Standard Tobacco Merger & TPB is Born (2009–2010)

By the late 2000s, the “portfolio” that had been stitched together—National Tobacco, North Atlantic Trading, Stoker’s, and the rest—was throwing off cash, but it still looked like what it was: a collection of acquired businesses living under a messy set of entities. If the owners ever wanted a clean exit, they needed a cleaner company.

That’s where Larry Wexler came in—and why 2009 matters.

Wexler became President and Chief Executive Officer in 2009, but he wasn’t new to the business. He had joined in 2003 and moved through senior operating roles, including Chief Executive Officer and Chief Operating Officer of National Tobacco Company. He also served on the board of the Tobacco Merchants Association. Before all of that, he’d spent five years consulting for emerging market, communication, and financial companies, and—most importantly—he had done 21 years at Philip Morris USA, rotating through key leadership roles across Finance, Marketing, and Sales. His final role there was Senior Vice President, Finance, Planning and Information Services. He earned his undergraduate degree at Yale and his M.B.A. from Stanford.

In other words: Wexler understood how Big Tobacco ran, how it thought, and where it simply wouldn’t bother competing. And he had the finance discipline to turn a patchwork of “other” tobacco assets into a real operating platform.

That platform eventually got a name that made the intent unmistakable. The company had been known as North Atlantic Holding Company, Inc., and in November 2015 it changed its name to Turning Point Brands, Inc.

The rebrand wasn’t just cosmetic. It reflected the internal logic the business had been building toward: a company organized around a few distinct pillars, each with its own loyal customer base, but all sharing the same advantage—distribution.

Zig-Zag Products: Rolling papers, tubes, finished cigars, make-your-own cigar wraps, and related smoking accessories. Zig-Zag is the leading premium rolling paper brand in both the United States and Canada.

Stoker’s Products: Moist snuff tobacco and loose-leaf chewing tobacco. Stoker’s dates to 1940 and grew into the #2 brand in chewing tobacco, while also becoming one of the fastest-growing brands in moist snuff.

Premium Cigars and Other OTP: A collection of cigar brands and other tobacco products.

Around this time, Zig-Zag also started pushing beyond papers into adjacent products where the brand could credibly travel. Introduced in 2009, Zig-Zag MYO Cigar Wraps quickly became the category leader. Made in the Dominican Republic, they gave consumers a way to make their own cigars with a smoother, more flavorful experience. Then in 2010, Zig-Zag entered the non-tipped cigarillo market with cigarillos made in the Dominican Republic using a blend of Dominican, Nicaraguan, and Honduran tobaccos—along with a range of flavors designed to broaden appeal.

Underneath all of it was a simple strategic insight: “Other Tobacco Products” was wildly fragmented. Dozens of small manufacturers. Lots of brands with real followings. Not much sophisticated consolidation. A focused acquirer could buy overlooked assets at reasonable prices, simplify overhead, run everything through shared distribution, and build leadership positions in niches the majors would never waste time defending.

And the three-pillar structure did something else that mattered: it diversified the cash engine. Zig-Zag could ride make-your-own demand during economic stress and, increasingly, benefit from cannabis legalization. Stoker’s was a value brand taking share in moist snuff. Cigars brought exposure to a different set of consumption habits altogether.

This was the moment the business stopped being “the leftovers” and started looking like a strategy.

V. The Roll-Up Strategy: Acquisitions & Category Dominance (2011–2016)

With Larry Wexler in the CEO seat and the business finally organized around clear pillars, TPB leaned into what it did best: buying the “small stuff” other companies didn’t want, then running it like it mattered.

The playbook was simple and repeatable. Find overlooked brands in categories everyone labeled “in decline.” Buy them at sane prices. Plug them into TPB’s existing sales and distribution machine. Cut duplicated overhead. Then manage the brands for steady cash, not moonshots.

That worked because the underlying economics of “Other Tobacco Products” were better than most outsiders assumed. Moist snuff and premium rolling papers carried meaningfully higher gross margins than cigarettes. The products were small, high-value, and easy to ship and stock. And the customer behavior was incredibly sticky—driven less by marketing and more by ritual, taste, and habit.

Which brings us to the real engine of the company: distribution.

TPB’s products are sold in more than 215,000 retail outlets across North America. That footprint wasn’t something you could conjure with a good pitch deck. It took years of building relationships with convenience store chains, smoke shops, mass retailers, and independents—then proving, week after week, that TPB could keep shelves stocked and help retailers earn margin dollars. Once you have that kind of reach, every new product you add can ride the same rails.

Stoker’s was the perfect example of how TPB used that system to win. In 2008, Stoker’s expanded into a value-oriented 12 oz. moist snuff tub—an unusually large format for the category. It wasn’t fancy. It was direct. A Great Dip at a Fair Price. And it worked: the tub grew faster than the overall moist snuff category after launch, because it spoke to a customer who didn’t want to trade brands for a coupon—they wanted more product for their money.

That success also showed how TPB competed. It didn’t try to out-Copenhagen Copenhagen or out-Skoal Skoal. It offered a credible product with a sharper value proposition and packaging that fit heavy-use behavior. As consumers faced pressure—first during the Great Recession, and later as cigarette prices kept rising—the value lane got wider, not narrower.

And crucially, TPB understood a truth that a lot of investors miss: a category can shrink and a company can still grow. If you can take share and push price, you don’t need the whole market to expand. You just need your corner of it to get stronger.

Private equity ownership during this stretch—Ares Management and GCP Capital Partners among others—fit the strategy. These were investors comfortable with unglamorous, cash-producing businesses, and they had a clear endgame in mind: keep compounding the platform, then find an exit when the story was clean enough for public markets.

By the mid-2010s, TPB had put real shape around what used to be a pile of leftovers: leading positions in niche categories, a distribution network that reached hundreds of thousands of retail points, and a team that knew exactly how to operate in tobacco’s unsexy corners.

The only question left was the big one: how do you turn a quietly cash-generative roll-up into a real standalone company?

VI. Going Public: The 2016 IPO and Independence

On May 10, 2016, Turning Point priced its initial public offering. The next day, it began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker TPB.

For a company that had spent years inside the private equity playbook, the IPO was a line in the sand. Public markets meant permanent capital, more visibility, and—just as important in roll-up land—a publicly traded stock that could be used as acquisition currency.

Larry Wexler framed it the way operators always do when they finally get out from under private ownership: flexibility. The IPO, he said, created a foundation for the company going forward, pairing new financial capacity with continued investment in the salesforce, regulatory infrastructure, and product development—setting TPB up to grow both organically and through future deals.

The investor pitch was straightforward and, in hindsight, pretty on-brand for TPB: this was a portfolio of habitual-consumption products with steady cash flow, a capital-light operating model that didn’t require heavy reinvestment, and leadership positions in small categories where pricing power still existed. Add in a fragmented competitive landscape, and you had a company built to keep consolidating.

But the market didn’t exactly roll out the red carpet.

In 2016, tobacco was already radioactive for many institutions. And TPB’s focus—rolling papers, chewing tobacco, value moist snuff—could feel like a throwback. Even the industry label, “Other Tobacco Products,” sounded like a bucket for leftovers, not a place to build a durable public company.

Still, for investors willing to look past the stigma, TPB could point to something tangible: a stable of recognizable brands—Zig-Zag, Beech-Nut, Stoker’s, Trophy, Havana Blossom, Durango, Our Pride, and Red Cap—throwing off meaningful earnings. In the periods it highlighted ahead of the offering, the business was generating tens of millions in adjusted EBITDA—real cash-producing power for a company most people had never heard of.

And that’s where the public-company logic started to click. If you could reliably generate cash, you could return it—through dividends and buybacks—while still leaving room to pay down debt and keep shopping for bolt-on acquisitions.

Even the regulatory burden that scared off newcomers cut both ways. FDA oversight, state licensing, age-verification rules, and MSA-related obligations made tobacco harder to enter and harder to disrupt, which effectively protected incumbents with established brands and distribution.

So TPB arrived on the public markets as something rare: a focused operator in a forgotten corner of a declining industry—built less on hype than on shelf space, repeat purchase behavior, and the quiet compounding of cash.

VII. The Vaping Pivot: NewGen & the Cannabis Bet (2016–2020)

Almost as soon as TPB became a public company, management made a move that—at the time—looked not just sensible, but inevitable. If cigarettes and legacy tobacco were in long, slow decline, then the obvious question was: what comes next?

TPB’s answer was to create a new segment called NewGen, designed to house the company’s bets on newer, less-mature categories—alternative nicotine products and adjacent “smoking ecosystem” products. Over time, that bucket came to include things like vaporizers, CBD, edibles, and other newer formats that sat just outside TPB’s traditional comfort zone.

The strategic logic was easy to understand. TPB already had what most upstarts didn’t: distribution relationships, retail know-how, and a team fluent in regulation. And in the second half of the 2010s, vaping wasn’t a niche—it was a rocket ship. JUUL, in particular, was rewriting the consumer-growth playbook in real time. In parallel, cannabis legalization was expanding state by state, and CBD products were exploding into mainstream retail. For a company that owned Zig-Zag, the idea of extending into cannabis-adjacent accessories felt like a natural extension of what customers were already using the brand for.

TPB didn’t just dip a toe. It started building infrastructure.

In one of its headline moves, Turning Point Brands, Inc. (NYSE: TPB), a leading provider of Other Tobacco Products ("OTP"), today announced that it has acquired related assets of Vapor Supply, VaporSupply.com and some of its affiliates. Vapor Supply is a leading B2B e-commerce marketing and distribution platform servicing vapor stores. Additionally, the company manufactures and markets proprietary e-liquids under the DripCo brand and operates eight company-owned stores in the Oklahoma market area.

"This acquisition further demonstrates TPB's continued commitment to the vaping segment. As a founding member of the Vapor Technology Association, TPB takes seriously the fight to protect this burgeoning industry for the many adult consumers and small businesses who depend on using and selling these products."

From there, NewGen grew into a real operating effort, not a slide in a deck: VaporBeast on the B2B side, VaporFi on the retail side, and a mix of proprietary e-liquid and device brands. For a moment, it looked like TPB had pulled off the hardest trick in consumer products—taking an old-world distribution advantage and using it to win in something new. NewGen grew to meaningful revenue and started to look like a credible diversification away from traditional OTP.

Then came 2019, and the ground shifted under the entire category.

"Vaping headlines dramatically disrupted our third-party vaping distribution business starting in mid-August. While third-party vaping saw a step function down in the quarter, we produced strong quarterly performance in the Smokeless and Smoking segments. We have proactively taken steps to address weakness in the third-party vaping distribution business," said Larry Wexler, President and CEO.

The vaping market ran headfirst into a perfect storm: an FDA crackdown on flavored products and a torrent of negative publicity around lung injuries—later attributed primarily to illicit THC products. Consumer demand snapped. Retailers pulled back. And an industry that had been growing at breakneck speed suddenly felt radioactive.

For TPB, the pain hit hardest in third-party vaping distribution—where it served as a wholesaler to independent vape shops. That part of the model was especially exposed to regulatory whiplash and sentiment swings. The NewGen segment that had been built for growth now needed restructuring.

The cannabis-adjacent push ran into its own version of the same problem. On paper, CBD looked like a tailwind, and legalization made smoking accessories feel like a rising tide. In practice, the regulatory patchwork around CBD—and the broader industry’s quality-control issues—made execution far messier than the thesis suggested. The opportunity was real, but the rules weren’t stable and the product landscape was chaotic.

What TPB learned, the hard way, was something that sounds obvious only in retrospect: great distribution doesn’t automatically make every adjacency work. TPB’s core strength was running established brands in mature categories with relatively predictable rulebooks. Vaping and CBD were different animals—fast-moving, innovation-driven, and constantly reshaped by regulation and headlines. And those capabilities didn’t naturally match the company’s DNA.

VIII. COVID & The Pandemic Paradox (2020–2021)

Then came March 2020, and the world changed overnight—in ways that proved unexpectedly favorable for Turning Point Brands.

Tobacco retail was deemed essential. While much of the economy went dark, convenience stores, tobacco shops, and grocery stores stayed open. TPB’s products didn’t disappear into a lockdown supply shock; they stayed right where they’d always been: behind the counter, within arm’s reach.

Almost immediately, the pandemic pushed consumer behavior in directions that just happened to line up with TPB’s core strengths.

Make-Your-Own Surge: Stuck at home and watching budgets, more people turned to rolling their own cigarettes. That’s Zig-Zag’s home turf—papers, tubes, and the accessories that make the habit easy.

Trading Down: Economic uncertainty pushed value to the center of the nicotine universe. Stoker’s, built around the promise “A Great Dip at a Fair Price,” benefited as consumers became more price-conscious and the value tier widened.

Reduced Competition: Smaller players—especially in newer categories like vaping—were more fragile. Cash got tight. Supply chains broke. Some competitors simply couldn’t keep product moving. TPB, with more scale and more stability, had an opening to take share and keep shelves filled.

And you can see it in the numbers the company reported quarter after quarter during that stretch. In early 2020, TPB posted a first quarter that came in ahead of its own expectations, with revenue rising to about $108 million and adjusted EBITDA jumping to roughly $28 million. In the second quarter, the momentum continued: revenue climbed to around $123 million and adjusted EBITDA rose to about $30 million, again ahead of guidance. Zig-Zag was the headline—one quarter saw growth north of 70%—but the broader point was that the core business was suddenly firing on all cylinders.

The market noticed. After the initial pandemic panic, TPB shares surged from around $20 at the lows to above $50 by mid-2021—a move that surprised a lot of investors who’d written the company off as a sleepy roll-up in a declining industry.

Zig-Zag’s position strengthened in measurable ways, too. In the U.S., it gained share in the tracked retail universe, rising to about one-third of the market and marking its seventh straight quarter of year-over-year share growth, according to MSAi. In paper cones—pre-rolled papers ready to be filled—Zig-Zag held the top spot in the measured channel, with share north of 40% in early 2021. Those cones mattered because they sat right at the intersection of two trends: convenience and cannabis. As legalization expanded and consumers looked for an easier ritual, cones became an on-ramp, and Zig-Zag was already there.

Another accelerant was e-commerce. With more shopping shifting online, TPB’s digital investments started to matter in a way they hadn’t before. Direct-to-consumer became more viable, and the company could reach customers without relying entirely on physical retail traffic.

But the pandemic boom carried an obvious shadow: sustainability. How much of this demand was a true step-change versus a temporary spike? When the world reopened, would make-your-own drift back down? And after the stock’s run, was the market pricing in a new normal that might not last?

IX. The Post-Pandemic Reckoning & Strategic Reset (2021–2023)

The hangover hit in 2021 and rolled straight into 2022. As restrictions eased and life snapped back toward normal, TPB ran into the cruelest math in business: comparing “normal” quarters to the once-in-a-generation surge of 2020 and 2021.

“Our first quarter results were in-line with our expectations as we continued to grow our market share for both Zig-Zag and Stoker's while navigating a difficult consumer and regulatory environment to drive profitability in each of our segments, including NewGen. Sales decreased 6 percent from the previous year driven by a 37 percent decline in NewGen sales but showed double-digit growth excluding NewGen,” said Yavor Efremov, President and CEO, Turning Point Brands.

Wait—Yavor Efremov?

Yes. TPB was changing leaders at the exact moment it was changing gears.

Larry Wexler—the architect of TPB’s modern era, from the 2009 platform-building through the 2016 IPO and the COVID boom—stepped back. He served as President and Chief Executive Officer from 2009 until his retirement in January 2022, and he remained on the board.

Efremov took the reins, but the tenure didn’t last long. In October 2022, the company appointed Graham Purdy as Chief Executive Officer. Purdy had been TPB’s Chief Operating Officer since 2019, and he wasn’t an outsider brought in to “transform” the business. He was a builder from inside the walls.

Since joining TPB in 2004, Purdy had cycled through leadership roles, including President of the New Ventures Division and Senior Vice-President, Sales. He oversaw two of TPB’s most successful brand extensions—Zig-Zag Cigar Wraps and Stoker’s MST—and built the company’s sales organization around a performance management system that helped TPB win where it always wins: at the shelf. Before TPB, he spent seven years at Philip Morris USA in senior sales and sales management positions.

His promotion read like a signal to the market: less experimentation, more execution. After the expansionary NewGen chapter, TPB was going back to operational fundamentals.

The reset showed up in a handful of concrete choices.

NewGen Restructuring: To make the vape business easier to see—and to stop mixing unrelated products into a segment that was already volatile—TPB moved certain non-vape sales and related costs out of NewGen and into the core reporting segments. Wild Hemp sales moved into Zig-Zag, where TPB reports its other smoking products. FRE nicotine pouch sales moved into Stoker’s, where TPB reports its other smokeless products. Both were marginal contributors to overall results. The effect was simple: Nu-X operations were absorbed into other reporting segments, and NewGen increasingly became what investors assumed it was all along—primarily proprietary vape products and the vape distribution business.

Core Focus: Management recommitted to the original formula: let Zig-Zag and Stoker’s do what they do best—generate dependable profits through brand strength and distribution.

Modern Oral Opportunity: Even as TPB pulled back from the chaos of traditional vaping, it began positioning FRE, its nicotine pouch brand, as a better-aligned growth bet—modern oral, but still adjacent to the company’s core smokeless competence.

At the same time, the operating environment got tougher. Inflation pushed up costs across tobacco leaf, packaging, and transportation. Consumers started to feel it too, as stimulus faded and interest rates climbed.

Then there was the regulatory cloud hanging over the entire sector. FDA proposals to ban menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars weighed on investor sentiment broadly. TPB wasn’t as exposed to menthol cigarettes as the biggest players, but in tobacco, regulatory uncertainty doesn’t stay neatly contained—it changes how the market values everything.

So this stretch became less about big swings and more about discipline: execute in the core, manage costs, streamline what wasn’t working, and keep the company positioned for whatever the next demand shift would be.

X. Today & The Modern Business Model (2024–Present)

As 2024 unfolded into 2025, Turning Point Brands hit another inflection point—but this one didn’t come from rolling papers or value moist snuff. It came from a category that barely existed a few years ago and is now rewriting the nicotine landscape: modern oral nicotine pouches.

Graham Purdy, President and CEO, put it plainly in the company’s 2024 results:

"We were pleased with our fourth quarter and full year 2024 results and the momentum we are seeing across the organization. We believe Zig-Zag remains on a sustainable growth trajectory with Stoker's MST continuing to grow market share. In Modern Oral, combined sales were $11.2 million for the quarter. FRE sales more than quadrupled versus year-ago and grew 26% sequentially, and we are excited by the successful launch of ALP during the quarter."

In 2024, TPB generated $360.66 million in revenue, up about 11% from $325.06 million the year before. Earnings rose to $39.81 million, up 3.5%. Profitability held up too: adjusted EBITDA for the full year reached $104.5 million, up 12%, with Q4 adjusted EBITDA of $26.2 million on $93.7 million in net sales.

By this point, the company’s operating structure had essentially hardened into two core segments—still anchored in its heritage, but now with modern oral pulling the growth narrative forward.

Zig-Zag Products: Rolling papers, tubes, finished cigars, MYO cigar wraps, and related accessories. Over the past decade, Zig-Zag expanded beyond classic papers into cigar wraps, hemp papers, and paper cones. In 2022, TPB also entered into an exclusive distribution agreement for CLIPPER lighters in the U.S. and Canada, adding a high-frequency accessory to the same retail footprint.

Stoker’s Products: Moist snuff tobacco, loose-leaf chewing tobacco, and—now the critical addition—nicotine pouches under FRE and ALP. Stoker’s traces its heritage back to 1940. It built its reputation as a value-driven workhorse brand, growing to the #1 position in chewing tobacco and remaining one of the fastest-growing brands in moist snuff. The portfolio also includes Beech-Nut, launched in 1897.

Then there’s the part of the story that would’ve sounded improbable even a few years ago: TPB’s modern oral growth is tied not just to product-market timing, but to a high-profile media partnership.

Turning Point Brands announced the launch of ALP nicotine pouches, a product co-founded by Tucker Carlson, following a pre-order phase the company said exceeded expectations. ALP is sold, marketed, and distributed through ALP Supply Co LLC, a newly formed 50/50 joint venture between the Tucker Carlson Network and Turning Point Brands.

The partnership drew attention—and controversy. Carlson’s involvement brought instant reach to a large conservative audience, and it also invited scrutiny that most tobacco brands never have to deal with. But whatever you think of the brand affiliation, TPB’s reported results made clear it was moving real product.

By Q2 2025, TPB reported net sales up 25.1% year-over-year to $116.6 million. Modern Oral net sales surged to $30.1 million—up 651% year-over-year—and represented 26% of total net sales.

The company also highlighted a changing financial profile alongside the growth push: net debt of $98.8 million, and FY25 guidance calling for adjusted EBITDA of $115 to $120 million and Modern Oral sales of $125 to $130 million.

Momentum continued into Q3 2025, when TPB reported revenue of $119 million, above several published estimates cited at the time. EPS came in at $1.27 versus a forecast of $0.78.

Zooming out, TPB is trying to win in a category that many analysts now expect to become enormous by the end of the decade—on the order of $10 billion in manufacturers’ revenue. Against that backdrop, the company has pointed to a long-term goal of double-digit market share, and its 2025 trajectory is being used internally as proof that the target isn’t just aspirational.

What’s also notable is how TPB is approaching the pouch market. It’s not a single-brand bet.

FRE is built for brick-and-mortar. It’s designed to win the old TPB way: chain accounts, shelves, and repeat purchase. ALP leans hard into a digital-first, direct-to-consumer strategy. Together, they create a dual-channel approach—two different customer acquisition engines, under the same corporate umbrella.

In one quarter, management described Modern Oral as the standout, with sales surging to $22.3 million, driven by FRE and ALP. FRE’s push into brick-and-mortar—now in chains like 7-Eleven—paired with ALP’s direct model, gave TPB a new kind of advantage: not just distribution breadth, but distribution diversity.

To chase that opportunity, TPB has been investing far more aggressively than its historically capital-light model would suggest:

"In order to best position the company to capitalize on this multibillion dollar opportunity, we have made and will continue to make significant investments in the business in refining our route to market strategy to prioritize white pouch while continuing to generate strong cash flow from our heritage brands. Key investment initiatives include reallocating sales and marketing resources, increasing the headcount of our sales force, improving our online presence, ramping up investment in chain accounts and developing U.S. Manufacturing. We have been particularly encouraged by our ability to identify and onboard new sales talent."

That’s the bet, stated clearly. TPB is still milking cash from the heritage engine—Zig-Zag and Stoker’s doing what they’ve always done—but it’s now willing to spend to build something bigger. If modern oral keeps growing the way management expects, this is the category that could turn Turning Point from a steady niche compounder into something that looks, and trades, more like a growth company.

XI. Strategic Analysis: Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you’re thinking, “Could a smart entrepreneur just start a new tobacco brand and take share?”—the industry has a very clear answer: not easily.

First, there’s regulation. The cigarette business in particular became dramatically harder to enter after the 1998 settlement era. Incumbents paid enormous sums, and, as Forbes put it, “In lieu of a share of the damages for past misdeeds, newcomers must pay deposits into escrow accounts to cover potential tort claims.” That kind of rulebook isn’t just paperwork—it’s a wall.

Then come the practical barriers: FDA oversight, state and local licensing, age-verification systems, and Master Settlement Agreement escrow obligations. Even if you can clear all of that, you still have to earn distribution. Convenience store chains, tobacco shops, and mass retailers don’t hand over shelf space to unknowns. Those relationships are built over years, and they’re defended hard.

And finally, there’s the most underrated barrier in tobacco: habit. If someone has dipped the same brand for twenty years, that isn’t a casual preference—it’s ritual. That inertia protects incumbents in a way most consumer categories can’t replicate.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

On paper, tobacco leaf and rolling paper look like commodities—and in many ways, they are. TPB sources tobacco for its smokeless products and paper for Zig-Zag from multiple suppliers, without a single point of failure.

Quality still matters, and that gives better suppliers some leverage, especially in categories where consistency drives repeat purchase. But overall, TPB doesn’t appear beholden to any one supplier that can dictate terms or meaningfully squeeze the business.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Retail is where the leverage lives.

Large chains—big convenience store operators, Walmart, Walgreens, grocery—control massive amounts of shelf space. They can negotiate hard on margins, placement, and promotional support.

But TPB isn’t selling commoditized, low-margin staples. In categories like rolling papers, moist snuff, and cigars, retailers earn attractive margin dollars compared to cigarettes, which gives them a reason to keep these products stocked and visible. And TPB’s relationships aren’t only with giants; the company also sells through smaller independents and tobacco specialists, which helps balance the equation.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

This is the force that never stops moving.

Cigarettes get pressured by vaping, nicotine pouches, heated tobacco, and quitting. Moist snuff and chewing tobacco face a similar squeeze from pouches, snus, and other smokeless formats. Rolling papers have their own dynamic: they can be used for tobacco, but they sit right next to cannabis consumption as legalization expands. And broadly, cannabis itself competes for the same “vice” wallet share in certain moments and occasions.

TPB’s strategy here has been less “defend the old world” and more “own a piece of the new one.” Zig-Zag can benefit from cannabis legalization. FRE and ALP are direct exposure to modern oral nicotine. The company is trying to position across the substitution wave—not pretend it isn’t happening.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Competition in tobacco is intense where the prize is big—and calmer where the market is fragmented.

In moist snuff and chewing tobacco, TPB goes up against heavyweight portfolios from Altria (Copenhagen, Skoal), Swedish Match (now Philip Morris International), and Swisher. These companies have deeper pockets and scale advantages. TPB’s way through is focus: leaning into lanes like value-priced moist snuff where the majors have less incentive to fight as aggressively.

In rolling papers and cigar wraps, the rivalry is real but more manageable. Zig-Zag competes with brands like Republic Tobacco’s JOB and E-Z Wider, Imperial Brands’ Rizla, and HBI International’s RAW. Still, Zig-Zag’s leadership position is well-established, and in a category this habit-driven, leadership tends to be sticky.

Premium cigars are different again: the market is highly fragmented, with hundreds of small players. That fragmentation limits any single competitor’s ability to dominate—and creates exactly the kind of “too small for giants” environment where TPB has historically been comfortable.

XII. Strategic Analysis: Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: MODERATE

TPB gets real, if unspectacular, scale benefits in the places you’d expect: paper manufacturing and moist snuff production. The bigger advantage is distribution density. Once you’ve already built the relationships, the sales coverage, and the logistics, adding another brand to the route is relatively cheap on an incremental basis.

But this isn’t Altria. TPB doesn’t have the kind of scale that automatically crushes input costs or overwhelms shelf space. Scale helps—but it’s not the company’s defining edge.

Network Effects: NONE

There’s no network effect here. A Zig-Zag customer doesn’t get a better experience because more people buy Zig-Zag. This is classic consumer packaged goods: brand, distribution, and repeat purchase—not a platform.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

This is the big one.

TPB’s sweet spot is exactly where Big Tobacco doesn’t want to play. The majors have strategic, regulatory, and reputational reasons to avoid leaning into categories like rolling papers, value moist snuff, and other small OTP niches. They carry the full weight of tobacco regulation and public scrutiny, but they’re too small to meaningfully move the needle for a giant.

Put yourself in a boardroom at Altria or Philip Morris. Management attention goes to cigarettes, heated tobacco, and the biggest growth pools in modern nicotine. Nobody is getting promoted for winning an extra point of share in rolling papers.

So TPB’s advantage doesn’t require it to outspend or outmuscle the giants. It simply requires the giants to keep acting like giants—focused on the markets that matter at their scale. TPB embraces what they flee, and that creates a durable wedge.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

Tobacco habits are sticky. Taste, ritual, routine—these become personal, and they don’t change easily. A long-time Copenhagen dipper or a Zig-Zag loyalist isn’t making a fresh decision every time they walk into a store. They’re repeating a pattern.

The caveat is price. If the gap gets wide enough, some consumers will switch, especially in value segments. But within normal pricing bands, loyalty tends to hold.

Branding: STRONG

TPB’s brands aren’t just recognizable—they’re encoded into the culture.

Zig-Zag is the flagship. It’s iconic packaging, deep heritage, and real meaning in the communities that use it. That kind of brand equity is hard to manufacture quickly, and even harder to dislodge once it’s tied to identity and ritual.

Stoker’s is a different kind of brand strength: value and authenticity. “A Great Dip at a Fair Price” is simple, credible, and consistent with how the product is positioned and bought. Premium cigar brands add their own version of this—heritage and legitimacy matter to enthusiasts, and those attributes take years to earn.

Cornered Resource: WEAK

TPB doesn’t have a proprietary lock on tobacco leaf, paper, or some secret input. The closest thing to a cornered resource is the brands themselves—Zig-Zag and Stoker’s can’t be duplicated—but that advantage is already captured under branding.

Process Power: MODERATE

There’s also a quiet competence moat: decades of operating know-how in niche tobacco. Distribution relationships that were built over years don’t appear overnight. Manufacturing consistency in papers and moist snuff, regulatory muscle memory, and sales execution all add up to a real process advantage—just not an unassailable one.

Primary Power: Counter-Positioning + Branding

If you had to boil TPB’s defensibility down to two things, it’s these: counter-positioning and branding.

The majors largely stay away, and the brands that TPB owns have the kind of heritage and loyalty that make customers repeat-buy with minimal friction. And importantly, they reinforce each other: Zig-Zag and Stoker’s are powerful partly because they’ve spent decades in niches where Big Tobacco didn’t bother to show up and fight.

XIII. The Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Thriving in Decline: TPB is a reminder that a shrinking category doesn’t automatically mean a shrinking business. If you can take share, push price, and run costs with discipline, profits can rise even while the total market quietly contracts. The trick is picking the right lane inside the decline—either be the brand that consolidates the category, or be the value player that wins when consumers trade down.

The Niche Advantage: There’s real strategic safety in being too small to matter to giants, but big enough to matter to you. In an Altria boardroom, rolling papers aren’t a growth initiative; they’re a rounding error. That indifference becomes TPB’s shield. The big players don’t defend hard in the corners—so specialists can build durable leadership there.

Distribution as Moat: In this business, the advantage isn’t an algorithm. It’s access. TPB sells through more than 215,000 retail outlets across North America, and that reach is built the slow way: years of sales coverage, retailer trust, reliable service levels, and the mundane competence of keeping shelves full. A new entrant can create a product fast. They can’t replicate a distribution web like this overnight.

Capital Allocation in Mature Industries: When you’re not chasing hypergrowth, the real game becomes: what do you do with the cash? Dividends, buybacks, debt paydown, or reinvestment? TPB’s story shows the balancing act—return capital when the core is stable, and spend when the opportunity truly fits, like modern oral. The dividing line is simple to say and hard to execute: invest in adjacencies that genuinely leverage what you already do well, not ones that just sound adjacent on a slide.

Regulatory Navigation: Tobacco’s regulatory burden is constant, expensive, and unavoidable. But it’s also a moat. FDA requirements, state licensing, age-verification rules, and MSA compliance make the category hard to enter and hard to operate casually. TPB has lived inside that rulebook for years, and that institutional muscle matters—especially when newer competitors discover that “great product” isn’t enough if you can’t clear the compliance hurdles.

The Adjacency Trap: NewGen is the cautionary chapter. The logic behind vaping and CBD was understandable, but execution is where adjacency theses go to die. Those markets demanded different capabilities—faster innovation cycles, more volatility, and a far messier regulatory environment. TPB spent capital and management attention without getting the payoff it hoped for. The lesson isn’t “never expand.” It’s “make sure the skills that made you great still apply.”

Private-to-Public Transition: The IPO didn’t just change ownership; it changed the tempo. Public-company life means quarters, guidance, analyst models, and constant narrative management—very different from private equity’s longer planning horizon. TPB has mostly handled the shift by keeping its operating discipline intact while building the investor-communication muscle that public markets demand.

Vice Investing: Tobacco comes with a built-in stigma tax. ESG-driven capital often won’t touch it, which narrows the buyer base and can keep valuations depressed. That’s a risk—fewer natural shareholders—but it can also create opportunity when the market’s moral discount becomes larger than the business risk.

Roll-Up Dynamics: TPB shows what roll-ups look like when they work: buy overlooked brands at sensible prices, integrate them into an existing distribution and operating platform, cut redundant overhead, and let cash flows compound. The difference between value creation and value destruction is discipline—reasonable multiples, real synergies, and no ego-driven dealmaking.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

Bull Case:

Durable Category Leadership: Zig-Zag’s number-one position in rolling papers and Stoker’s share gains in moist snuff aren’t a marketing trick. They’re the product of decades of shelf space, habit, and brand equity surviving consolidation, regulation, and recession after recession.

Pricing Power Offsetting Volume Declines: Tobacco is one of the rare categories where “I’ll just switch” often doesn’t happen. Even when volumes drift down, TPB can often take price and protect revenue because the customer is buying a ritual, not a generic commodity.

Modern Oral Transformation: Nicotine pouches are the real swing factor. Analysts expect the category to approach $10 billion in manufacturers’ revenue by the end of the decade. If FRE and ALP can carve out meaningful share, TPB stops being just a steady niche compounder and starts to look like a company with an actual growth engine.

Cash Generation Supporting Returns: TPB’s model has historically thrown off real cash, which gives it options: return capital through dividends and buybacks, pay down debt, or keep consolidating smaller categories. That flexibility matters in mature industries.

Cannabis Tailwind for Zig-Zag: As cannabis legalization spreads, the “rolling” ecosystem grows with it—papers, cones, wraps, accessories. Zig-Zag is already a default choice for many consumers, which makes legalization less a reinvention and more a widening of the same playing field.

Regulatory Disruption Could Benefit TPB: A menthol cigarette ban wouldn’t eliminate nicotine demand. It would redirect it. That kind of shock can push consumers into cigars, roll-your-own, and smokeless formats—exactly the corners where TPB has lived for years.

Valuation: For investors willing to own tobacco exposure, the appeal is the mismatch: modest multiples relative to cash generation, with a plausible upside scenario if modern oral keeps scaling.

Bear Case:

Secular Category Decline Accelerates: The long-term demand problem is real. Youth tobacco use continues to fall, and as today’s users age out, there’s no guarantee the next generation replaces them. If the decline steepens, pricing can only carry the story for so long.

Regulatory Risk: The FDA can always change the rules—flavored cigar restrictions, tighter nicotine regulation, new marketing limits. In tobacco, the rulebook is never final, and regulatory headline risk can hit valuations even before it hits revenue.

Vaping/Pouches Cannibalize Traditional Tobacco Faster: Pouches and other modern formats could accelerate substitution away from moist snuff and other legacy products. If that shift happens faster than TPB’s own pouch business can grow, the core could erode quicker than expected.

Modern Oral Execution Risk: This is a brutal arena. Philip Morris (ZYN), British American Tobacco (Velo), and other well-capitalized players have the resources to fight for shelf space, pricing, and marketing. TPB’s ambition of double-digit share is not guaranteed—especially in a category many expect to consolidate into a small handful of dominant brands by 2030.

Retailer Consolidation Pressure: As convenience store chains get bigger, they gain leverage. More leverage usually means tougher negotiations, more promotional demands, and tighter margins.

Debt and Investment Burden: Winning in modern oral takes spending—sales force, marketing, online capabilities, and potentially U.S. manufacturing. That’s a different posture than TPB’s historically capital-light model. And the balance sheet matters here: total gross debt as of June 30, 2025 was $300.0 million.

ESG Investor Avoidance: Tobacco still carries a stigma discount. Many ESG-focused funds simply won’t own it, which narrows the shareholder base and can keep multiples lower than fundamentals alone might justify.

Competition from Cannabis: Cannabis doesn’t just expand the Zig-Zag ecosystem—it can also steal “vice occasions” from tobacco. In some markets, that substitution could shrink the total addressable spend.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Volume Trends by Category: Price can mask a lot. The clearest signal is unit volume in rolling papers, moist snuff, and cigars. If volume declines deepen meaningfully and persist, that’s the industry tide pulling harder.

Modern Oral Market Share: The thesis increasingly hinges on FRE and ALP becoming more than “promising.” TPB has talked about a double-digit share goal in pouches; progress toward that—through management commentary and third-party category data—will determine whether modern oral is a side business or the future of the company.

Pricing Realization vs. Volume Trade-off: Watch the balance: how much price TPB takes, and what it costs in volume. The best outcome is the classic mature-category play—modest volume declines, more than offset by pricing—without triggering a consumer exodus.

XV. Epilogue & Looking Forward

So where does Turning Point Brands go from here? From the outside, it looks like a niche tobacco company with a couple of heritage cash cows. From the inside, it’s a business with multiple levers—and a leadership team trying to decide how hard to pull each one.

One path is the simplest: stay the course. Keep harvesting steady cash from Zig-Zag and Stoker’s, invest in modern oral without lighting the P&L on fire, and return excess capital through dividends and buybacks. It’s a strategy built for durability. The trade-off is obvious too: it’s hard to capture the market’s imagination with “steady.”

Another path is to treat modern oral like the main event. Double down on FRE and ALP with accelerated investment in marketing, manufacturing capacity, and distribution. Accept lower near-term profitability in exchange for a real shot at meaningful share in the fastest-growing part of the nicotine universe. If it works, TPB’s identity changes. If it doesn’t, it’s an expensive lesson.

A third option is the one TPB knows best: keep consolidating. The “Other Tobacco Products” world is still fragmented, and there are always overlooked brands looking for a better home—whether in traditional categories or adjacent ones. Done well, M&A would let TPB do what it has done for years: buy under-managed assets, plug them into its distribution rails, and squeeze out steady returns. But roll-ups only work with discipline, and tobacco is not the place to get sloppy with price.

Then there’s the cleanest ending: an exit. TPB’s mix of stable cash flows, defensible niche positions, and real distribution reach could be attractive to private equity. A strategic buyer might also value the same things—especially if it wanted exposure to OTP without building it from scratch. That path crystallizes value, but it also closes the loop on the public company story.

And finally, there’s the wildcard that’s been orbiting Zig-Zag for years: cannabis. As legalization continues to evolve, Zig-Zag has a natural right to play in the broader “rolling” ecosystem. Going harder here could create upside, but it comes with the same problem TPB ran into before: regulatory uncertainty and a moving target of what’s allowed, where, and how it can be marketed.

Hanging over all of these choices is the generational question that every tobacco company eventually faces: what happens as today’s users age out? Moist snuff users have historically skewed middle-aged and male. Rolling papers skew younger, but that audience has its own shifts in consumption and preference. The long-term answer for the industry is either to slow the decline in legacy categories or to transition successfully into products that fit modern behavior.

Modern oral may be that bridge. Nicotine pouches have drawn consumers who largely rejected cigarettes but still want nicotine—often with a cleaner, more discreet ritual. If TPB can build durable positions in that category, it doesn’t just add growth; it extends relevance.

At the same time, the competitive and regulatory landscape keeps moving. Harm-reduction narratives continue to gain traction, with smokeless alternatives often viewed as less harmful than cigarettes. And the FDA’s actions around reduced-harm pathways signal that regulation may eventually create clearer lanes for certain non-combustible products—even if the details remain uncertain and slow.

There are also broader global dynamics in tobacco: developing markets that can offset decline in the U.S., shifting regulations, and changing consumer preferences. TPB has stayed primarily U.S.-focused, but international expansion remains an option—though it would be a meaningful strategic step, not a casual bolt-on.

What makes TPB’s story stick isn’t just the products. It’s the pattern. Big Tobacco discarded these assets because they were too small to matter. TPB made them the whole point—and built a real public company by obsessing over niches, distribution relationships, and brands with stubborn staying power.

For investors, that’s the appeal and the tension. TPB is an unloved, regulated, stigmatized business that still generates real cash—plus it now has a genuine option on a category transformation through modern oral. Whether that bet becomes the next chapter or the next cautionary tale is still open. But the core machine is there: shelf space, repeat purchase behavior, and brands that, for the right customer, are less a choice than a ritual.

The French soldier on the Zig-Zag pack has been staring out from convenience store counters for well over a century. The world around him has changed—lawsuits, regulation, vaping, legalization, pouches. But the lesson he represents hasn’t: in habit-driven markets, strong brands and strong distribution can outlast almost anything.

XVI. Resources for Further Reading

Primary Sources: - Turning Point Brands SEC Filings (10-K, 10-Q, Proxy Statements) - The most direct window into the business: segment performance, strategy shifts, risk factors, and what management actually says when it has to sign its name to it - FDA Tobacco Regulations & Deeming Rules - The rulebook that shapes everything from product approvals to marketing limits and enforcement risk

Industry Context: - "Golden Holocaust" by Robert Proctor - A sweeping history of the tobacco industry and the long arc of how science, policy, and corporate behavior collided - "Barbarians at the Gate" by Bryan Burrough & John Helyar - The classic LBO narrative; not about tobacco, but essential for understanding the mindset and mechanics behind private-equity-era playbooks like TPB’s - Tobacco Reporter Magazine and Convenience Store News - Trade-level reporting on distribution, category trends, and what’s actually happening at the counter

Strategic Frameworks: - Michael Porter's "Competitive Strategy" - The original blueprint for Five Forces thinking - Hamilton Helmer's "7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy" - A practical lens for spotting advantages that can hold up over time - Joel Greenblatt's "You Can Be a Stock Market Genius" - A sharp guide to spinoffs, neglected companies, and the kinds of “weird” situations where hidden value often lives

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music