TowneBank: The Story of Virginia's Hometown Banking Experiment

I. Introduction and Episode Roadmap

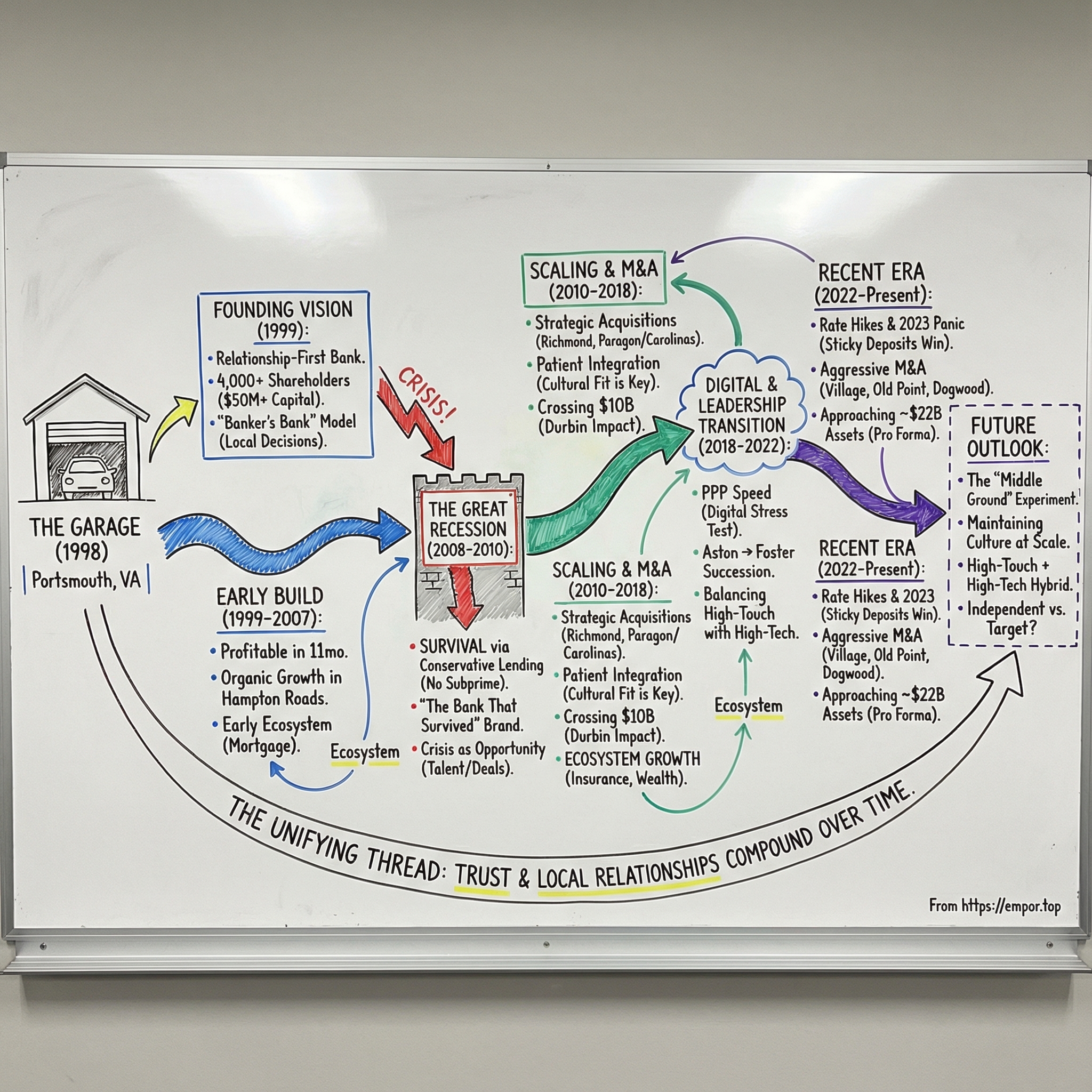

Picture a two-car garage in Portsmouth, Virginia, in the summer of 1998. Around folding tables, a handful of veteran bankers mapped out an idea that most of the industry had already written off: start a new community bank just as consolidation was swallowing Virginia’s hometown institutions. At the center of it was G. Robert “Bob” Aston Jr., a banker who had spent nearly five decades watching relationship banking get squeezed out, merger by merger.

That garage meeting became the seed of TowneBank: a community-first bank built on a few simple convictions. Hire exceptional people. Create a family atmosphere. Stay grounded with local boards. And deliver the kind of service that makes customers feel known, not processed.

The puzzle at the heart of this story is straightforward—and kind of wild. How did a bank founded in 1999—months before the dot-com crash, and two years before the post-9/11 recession—grow from zero deposits into Virginia’s largest bank headquartered in-state, reaching $17.25 billion in total assets as of December 31, 2024? All while countless community banks either vanished or got absorbed by out-of-state giants.

And then there’s the bigger question TowneBank forces us to confront: can relationship banking still win in the age of fintech and megabanks? Can knowing customers by name, making decisions locally, and putting community at the center produce competitive results when banking is increasingly driven by algorithms and national digital platforms?

That’s what we’re going to unpack—through four big themes: contrarian timing, and why uncertainty can be an opening; the “Banker’s Bank” model, where executive officers are the bankers, not just managers; strategic M&A that turned industry stress into expansion; and the compounding power of local relationships in a business that’s become more impersonal every year.

By the end, we won’t just understand how TowneBank got built. We’ll have a clearer view of what its success—and its challenges—suggest about where American banking goes from here.

II. The Virginia Banking Context and Founding Vision (1999-2001)

To understand why Bob Aston was sketching out a new bank in a garage in 1998, you have to understand what had just happened to Virginia banking. The 1990s weren’t just a decade of deals. They were a decade of disappearances.

One industry observer later summed it up simply: “I witnessed the six great Virginia regional banks fall like dominoes during the course of the ’90s.” Not long before, the Old Dominion had been home to names like Crestar, Signet, Central Fidelity, Sovran, Jefferson National, Dominion, and First Virginia—institutions with local boards, local credit decisions, and local accountability.

Back in the early 1980s, Virginia banks—like banks across the country—were profitable, tightly regulated, and geographically rooted. There were familiar fixtures like Virginia National Bank, United Virginia Bank, and Bank of Virginia. Banking was, for better or worse, a local business.

Then interstate banking arrived, and the consolidation wave hit Virginia hard.

In 1984, Virginia National Bankshares merged with First & Merchants to form Sovran Financial. A few years later, in 1990, Sovran merged with Citizens & Southern National Bank—and through the industry’s rapid evolution, that lineage ultimately fed into what became Bank of America by 1998. Crestar, at the time the largest independent bank in Virginia, was acquired by SunTrust in 1998. Other Virginia names were absorbed too—many by out-of-state acquirers—until “Virginia banks” were increasingly Virginia in history only: Sovran flowed into NCNB, then NationsBank, then Bank of America; Crestar into SunTrust; Signet and Bank of Virginia into Wachovia, which later became part of Wells Fargo.

This wasn’t just corporate musical chairs. It was a change in how banking worked on the ground. Local decision-making thinned out. Relationship lending—built on knowing the owner, the family, the industry, the town—started to look more like transaction processing. The small business owner who once could walk into a banker’s office and get an answer the same day was now asked to package a file for a credit committee in Charlotte or Atlanta.

That was the opening Aston saw.

By the time TowneBank was just an idea, Aston had spent 47 years in banking. He’d been president and CEO at Citizens Trust Co., Commerce Bank, and BB&T of Virginia, and served on boards along the way. He was also a UVA Graduate School of Retail Banking alumnus. But the most telling detail is how early it started: he’d been in community banking since high school, beginning at Citizens Trust doing the kinds of jobs that teach you what “service” actually means—getting coffee, running the mail, learning who matters and why.

He knew exactly what Virginia had lost. And he believed it could be rebuilt.

So in 1998, Aston began pulling together what he saw as the best bankers in the market to start something new. As he put it later, “The organization of the bank began in my garage in the summer of 1998.” And crucially, they didn’t just talk—they funded it. They raised more than $50 million from the local community.

The place they were building mattered as much as the model. Hampton Roads isn’t just another metro. The military presence is woven into the economy, accounting for roughly 40% of the region’s gross product. In 2023, direct Department of Defense spending was about $28 billion. Naval Station Norfolk is the world’s largest naval station, and nearly a quarter of the nation’s active-duty military personnel are stationed in Hampton Roads.

That kind of economy produces a specific kind of customer: defense contractors, small businesses serving the Navy, and professionals who value stability and trust. Exactly the sort of clients most frustrated by distant headquarters and centralized decision-making.

On April 8, 1999, TowneBank opened with three offices, backed by start-up capital from more than 4,000 shareholders. From there, it grew from zero deposits and no customers into a bank that, as of today, has reported $14.1 billion in deposits, about 108,000 customers, and roughly $16.9 billion in total assets.

From day one, the “skin in the game” concept wasn’t a slogan—it was the ownership structure. Those thousands of founding shareholders weren’t just looking for a return. They were future customers, community members, and the first wave of advocates for a bank they literally owned a piece of. That alignment—between shareholders, customers, and community—would become one of TowneBank’s defining features.

And that’s the key founding insight: by conventional wisdom, the timing looked awful. But for Aston’s strategy, it was almost perfect. TowneBank wasn’t trying to out-scale the giants. It was trying to serve the customers the giants had—through consolidation—stopped truly serving.

III. The Early Build: Relationship Banking as Competitive Advantage (2001-2007)

TowneBank reached profitability after just 11 months. For a brand-new bank, that was almost unheard of—de novos often need years to climb out of the startup hole. So what was actually happening here? How did a three-office bank pull off what most people assumed was impossible?

It came down to a business model that wasn’t just “community banking” in the brochure. It was community banking in the org chart.

Local decision-making sat at the center of TowneBank’s strategy, delivered through the leadership of each group’s President and Board of Directors. This wasn’t a slogan. Unlike the megabanks—where a local banker might “own the relationship” but not the decision—TowneBank gave local leaders real authority. Credit calls didn’t have to climb a distant ladder to a regional committee. The person in the room could actually say yes.

That changed the experience for customers immediately. The bank staffed up with experienced local bankers who could bring both expertise and personal attention—and then paired that with local decision-making. Executive officers weren’t just managers overseeing teams; they were the bankers. When a business owner needed a loan, they sat across from someone who could understand the situation and had the power to act.

And that power created speed. Speed that mattered. A Navy contractor needing a credit line to ramp up ahead of a new contract couldn’t wait weeks for approval to travel to another city. A real estate developer chasing a time-sensitive deal needed capital in days, not months. TowneBank’s structure turned responsiveness into a competitive advantage.

Aston credited the culture as much as the model. The “secret sauce,” he said, was simple: be nice to people. “We don't have more money. We don't have more technology. We don't have more employees. We don't really have more of anything, except we've got more really nice people and that is what has built the company.”

Even in those early years, TowneBank started building what would become its broader ecosystem. In 2001, it expanded into mortgage banking through the acquisition of GSH Mortgage. This wasn’t diversification for its own sake. It was an early step toward serving customers across more of their financial lives—creating natural cross-selling opportunities, yes, but also building deeper relationships that made TowneBank harder to replace.

Over time, TowneBank kept its community-banking core while expanding beyond traditional banking into realty, mortgage, and insurance services—an effort to become more useful to customers, not just bigger.

The culture got codified early, too. TowneBank’s mission statement is: “To promote a culture of caring, serving, and enriching the lives of others.” The bank sought teammates who, by their nature, are “givers not takers,” people who find real fulfillment in serving others and who take pride in volunteer work and the philanthropic contributions of the TowneBank Foundation. As Aston put it, that is the “Towne Way.” It’s not the kind of strategy you’d expect to see diagrammed in the Harvard Business Review—but on “Main Street USA,” it made friends and neighbors feel genuinely known.

By 2007, TowneBank had expanded organically across Hampton Roads, proving relationship banking could produce real, competitive results. It had become known as the most successful new bank ever chartered in Virginia, with branches stretching from Williamsburg to Northeastern North Carolina.

This early chapter matters because it answered the first big question: would the model work when times were good? TowneBank showed it could. The next chapter would test something harder—whether it could work when times were terrible.

IV. Surviving the Great Financial Crisis: The Inflection Point (2008-2010)

The 2008 financial crisis was an extinction event for American community banking. From 2008 to 2012, the FDIC shut down 465 banks. In the five years before 2008, only 10 failed. Almost overnight, a business built on trust became a business built on triage.

Hampton Roads didn’t get a pass. Real estate values fell hard. Uncertainty around Navy budgets rattled the region’s economic backbone. Across Virginia and North Carolina, banks that had ridden the housing boom—especially anything tied to speculative development and loose mortgage credit—watched their loan books crack.

TowneBank came out the other side not just intact, but stronger. And the reason wasn’t a clever hedge or a lucky bet. It was embedded in the thing that had looked almost quaint during the good years: relationship banking.

When you actually know your borrowers—when the local president has tracked a business for years, understands how it makes money, and sees how it behaves when things get tight—you underwrite differently. You don’t hand out construction financing to someone you’ve never met because the spreadsheet says the pro forma works. You don’t approve loans you can tell, in plain English, won’t hold up once the music stops.

And in the Great Recession, the music absolutely stopped—especially in real estate. That matters because real estate was the transmission mechanism for a huge share of bank failures. When property values slid and projects stalled, the losses didn’t stay confined to developers; they moved straight onto bank balance sheets. Any serious attempt to explain why banks failed in this era has to grapple with that channel: a severe, extended real estate downturn feeding directly into credit losses.

TowneBank’s relationship-based approach meant it had avoided many of the exposures that detonated elsewhere. Without subprime mortgages imploding on its books, and without a portfolio stuffed with the most fragile construction loans, the bank kept the capital strength it needed to do something most banks couldn’t: stay open for business.

The crisis also opened doors that simply don’t exist in normal times. Failed banks meant the FDIC needed healthy acquirers. Strong bankers from collapsing institutions suddenly became available. And customers—business owners, families, nonprofits—found themselves asking a basic question: if my bank can disappear, where do I put my money now?

TowneBank’s standing as “the bank that survived” became valuable local currency. In a region shaken by closures and mergers, conservative underwriting and local decision-making stopped looking old-fashioned and started looking like the point.

There was another stabilizer, too: Hampton Roads’ military-heavy economy. Defense-related activity didn’t evaporate the way homebuilding and speculative real estate did. The relationships TowneBank had built with defense contractors, Navy-adjacent businesses, and the professionals who served them tended to hold up better than the boom-era lending that took down so many competitors.

So by 2010, while others were still sorting through crisis wreckage, TowneBank was in position for the next phase of its evolution—shifting from proving the model to scaling it.

V. The Serial Acquisition Machine: Building Scale (2010-2015)

Coming out of the crisis, TowneBank faced a new kind of reality. The relationship model had worked—better than worked. But the post-2008 world rewarded something else too: scale. Technology got more expensive. Compliance got heavier. And competing against bigger banks meant you couldn’t just be better; you also had to be big enough to keep up.

So TowneBank made a pivot that would define the next era. It stopped relying primarily on organic growth and started building a repeatable acquisition playbook.

A series of deals expanded both its footprint and its credibility. Acquisitions like James River Bankshares and Monarch Financial Holdings weren’t just about buying branches—they were about entering and deepening markets. Richmond, especially, mattered. It wasn’t only the state capital; it was Virginia’s business hub, and it had been missing a truly independent hometown banking presence since the consolidation wave had swept the old giants away.

In 2014, TowneBank acquired Franklin Financial Corporation for approximately $275 million, pushing deeper into the Richmond market. Then in 2015, it merged with Monarch Financial Holdings, Inc. for approximately $220 million—another step toward building density and relevance across Virginia.

But what really separated TowneBank wasn’t the fact that it acquired banks. It was how it absorbed them.

TowneBank’s approach was unusually patient. Instead of rushing to slap on a new sign and centralize everything, it tended to keep local leadership in place, preserve customer relationships, and convert systems gradually. The presidents and bankers who knew the market didn’t get shoved aside—they often stayed on, becoming regional leaders inside TowneBank, bringing their customer books and their local knowledge with them. In a business where trust is the product, that continuity mattered.

And just as important: TowneBank’s discipline showed up in the deals it didn’t do. Cultural fit was treated as non-negotiable. If a target didn’t align with TowneBank’s relationship-first philosophy, it wasn’t worth the paper math—no matter how “attractive” it looked on a spreadsheet. That restraint helped the bank avoid the integration blowups that haunt so many serial acquirers.

At the same time, TowneBank was quietly building a second engine alongside the bank: insurance. Over the years, Towne Insurance grew through acquisitions—27 of them since 2001—and by 2024 it was delivering growth through strong retention, organic momentum, and what the company described as best-in-class service. It also became a practical extension of TowneBank’s ecosystem strategy, with regional insurance offices moving into TowneBank financial centers to encourage collaboration across insurance, banking, and wealth management.

Put it all together, and the point of this era comes into focus. This wasn’t acquisition-for-acquisition’s-sake. It was TowneBank buying the scale it needed to keep relationship banking viable—funding modern infrastructure, meeting rising regulatory demands, and staying competitive, without giving up the local, human model that made the franchise work in the first place.

VI. The Carolinas Expansion and Geographic Strategy (2014-2018)

TowneBank’s biggest test of whether relationship banking could truly scale didn’t happen in Hampton Roads. It happened a state south, in North Carolina—where the fastest-growing markets in the region were already crowded with ambitious banks and national giants.

The bet was simple, and risky: take a model built on local trust and decision-making, and prove it could travel.

That’s why the Paragon deal mattered so much. In 2017, TowneBank and Raleigh-based Paragon Commercial Corporation announced a definitive merger agreement that would bring TowneBank into Charlotte and Raleigh—two of the fastest-growing metros in the country—and create what they described at the time as a roughly $9.7 billion community bank.

Paragon wasn’t a random target. Paragon Commercial Corporation, the parent of Paragon Bank, had built its own brand around a “private banking experience” for businesses, professionals, executives, and entrepreneurs. It was founded in 1999, the same year TowneBank opened its doors, and it operated with the same kind of high-touch, highly responsive service TowneBank believed in. In other words, it wasn’t just expansion. It was a cultural match.

Paragon’s CEO called the two institutions “mirror images” in their business models and community commitment—a merger framed not as consolidation, but as two like-minded franchises joining forces.

On January 26, 2018, TowneBank completed the merger with Paragon. The deal had been valued at $323.7 million as of April 2017.

Strategically, Paragon did two things at once. First, it gave TowneBank real entry into the Research Triangle and Charlotte—markets with strong growth and deep pools of middle-market business. Second, it pushed TowneBank over a line that changes the economics of banking.

At the end of 2017, TowneBank reported total assets of $8.52 billion. Pro forma for the Paragon merger, it would have been about $10.5 billion. That $10 billion threshold is a milestone, but it comes with a catch: it triggers Durbin Amendment limits on debit interchange fees. For TowneBank, that meant an estimated hit of $8 million or more in annual revenue. Scale, it turns out, isn’t free.

Operationally, TowneBank took a characteristically relationship-first approach to integration. After the merger, it operated in Raleigh, Charlotte, and Cary as Paragon Bank, a division of TowneBank. Robert C. Hatley, Paragon’s former President and CEO, stayed on as President and CEO of the Paragon Division—continuity by design, to protect customer trust and keep local leadership truly local.

This was the Carolina experiment in full: recruit bankers with real relationships, keep decision-making close to the customer, and let regional leaders adapt the model to the market—without diluting the culture that made it work in the first place.

By 2018, TowneBank wasn’t just a Hampton Roads success story anymore. It was a multi-state regional franchise, with the kind of scale that forced a new question: could a relationship bank still win as banking became more digital, more regulated, and more expensive to run?

VII. The $10B+ Transformation and Digital Challenge (2018-2022)

Crossing $10 billion in assets changed TowneBank’s world in ways that were both immediate and sneaky. The immediate part was the Durbin Amendment: debit interchange fees got capped, and TowneBank faced roughly $8 million a year in lost revenue that now had to be earned somewhere else. The sneakier part was identity. At $10B-plus, you’re no longer a scrappy community upstart—you’re a regional bank. The question became: could TowneBank scale up without sanding off the very edges that made it TowneBank?

Then the pandemic hit, and the relationship model got its biggest real-time stress test.

In 2020, TowneBank processed more than $1 billion in Paycheck Protection Program loans. The speed was the story. In just 13 days, the bank processed nearly 5,000 PPP applications totaling over $1 billion, supporting more than 117,000 jobs in its communities. And the urgency was real: the SBA quickly announced the initial $349 billion in funding had been exhausted.

PPP wasn’t just “good customer service.” It was TowneBank’s thesis, under pressure, working in the wild. When small businesses were scrambling for lifelines, TowneBank’s bankers didn’t have to start from scratch. They already knew the owners. They already understood the businesses. And that familiarity translated into action—fast.

But COVID also forced an uncomfortable truth into the open: relationships still mattered, but customers now expected those relationships to be available through a screen. Face-to-face banking didn’t disappear, but it stopped being the default. So TowneBank leaned harder into technology—mobile banking, digital mortgage applications, and upgraded treasury management tools—trying to build a better digital experience without turning the bank into something impersonal.

That blend—high-touch banking delivered through higher-tech channels—became the defining balancing act of this era.

The acquisition engine kept running, too. In 2022, TowneBank acquired Farmers Bankshares, Inc. for approximately $56 million, and completed the deal in January 2023. Farmers brought additional presence in Western Tidewater, reinforcing TowneBank’s Hampton Roads stronghold. The transaction included $277.89 million in loans, $244.89 million in securities, and $514.57 million in deposits.

And while the bank was adapting to new economics and new customer behavior, it was also facing something even harder to engineer: leadership succession.

The founding generation that had built TowneBank from Bob Aston’s garage was approaching the handoff. TowneBank announced Billy Foster as CEO successor, effective January 1, 2023. Aston framed the choice in cultural terms, saying, “Billy’s extraordinary leadership style is deeply rooted in the Towne culture of caring that serves as the foundation of our long-term success.”

By the time the transition arrived, William I. Foster III was President and CEO, and Brian K. Skinner was Executive Vice President and CFO. TowneBank had always sold itself on people and culture. Now it had to prove that culture could survive the ultimate test: continuing without the founder at the center of everything.

VIII. Recent Era: Rate Environment and Strategic Positioning (2022-Present)

The Federal Reserve’s rapid rate hikes starting in 2022 rewrote the rules for every regional bank. For TowneBank, it created a familiar kind of test: when the environment shifts fast, does a relationship-driven model bend—or break?

That question got very real in March 2023. Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic collapsed in quick succession, and the shockwave hit the entire sector. Overnight, everyone cared about the same things: deposit concentration, the share of deposits that were uninsured, and the unrealized losses sitting in securities portfolios.

This was the moment TowneBank’s deposit franchise had been built for. The “relationship deposit” idea—sometimes dismissed as old-school—suddenly looked like a competitive advantage you could feel in real time. When customers know their banker, trust the institution, and use multiple products, they’re less likely to run at the first sign of a headline.

That didn’t mean TowneBank was immune to the same forces reshaping deposits everywhere. As rates rose, customers shifted money into interest-bearing accounts. Noninterest-bearing deposits declined 2.06% to $4.25 billion, and they represented 29.46% of total deposits at December 31, 2024.

Financially, TowneBank kept moving forward. For the year ended December 31, 2024, earnings were $161.76 million, or $2.15 per diluted share, up from $153.72 million, or $2.06 per diluted share, in 2023. Excluding certain items affecting comparability, core earnings (non-GAAP) for 2024 were $163.65 million, or $2.18 per diluted share.

Higher rates also helped the core engine: net interest margin. Net interest margin was 2.99% and taxable equivalent net interest margin was 3.02%, up from the prior-year quarter’s net interest margin of 2.83%.

Then, in 2025, TowneBank hit the gas on M&A again.

On April 1, 2025, TowneBank completed its merger with Village Bank and Trust Financial Corp. and its subsidiary, Village Bank. The deal strengthened TowneBank’s position in the Richmond MSA. TowneBank’s $120 million acquisition of Midlothian-based Village Bank brought the combined company to approximately $17.8 billion in total assets, with $14.9 billion in deposits and $12.1 billion in loans.

A few months later, TowneBank followed with another move back in its home territory. On September 1, 2025, it completed its merger with Old Point Financial Corporation, including the merger of Old Point National Bank into TowneBank. The company described the strategic prize clearly: a high-quality core deposit franchise that deepened TowneBank’s position in Hampton Roads.

And then came the biggest swing.

On August 19, 2025, TowneBank and Raleigh-based Dogwood State Bank announced a definitive merger agreement for TowneBank to acquire Dogwood. The strategic logic was geographic—and ambitious: accelerate TowneBank’s march down the fast-growing Interstate 85 corridor, extending the story from Richmond into the Carolinas and into the upstate region of South Carolina. The announcement also outlined a meaningful expansion of TowneBank’s presence across Raleigh, Greensboro-Winston Salem, Greenville, and Charlotte, plus a broader footprint along the Eastern North Carolina coast—from the Outer Banks down through Morehead City, Greenville, Fayetteville, and Wilmington—and a new location in Charleston, South Carolina.

Under the merger terms, Dogwood common shareholders will receive a fixed exchange ratio of 0.700 shares of TowneBank common stock for each outstanding share of Dogwood common stock. That implied a value of $25.04 per Dogwood share, or approximately $476.2 million.

As described, the transaction—valued at $491.2 million with a value-to-tangible common equity ratio of 223.7%—was the sixth-largest and third-most expensive U.S. bank M&A deal of 2025.

Dogwood shareholders approved the merger at a special meeting on December 3, 2025. The companies expected the deal to close early in the first quarter of 2026, subject to customary closing conditions.

By this point, TowneBank had clearly entered a new weight class. With total assets of $19.68 billion as of September 30, 2025, it was one of the largest banks headquartered in Virginia.

And the operating momentum showed up in the numbers, too. In the third quarter of 2025, total revenue was $215.67M, up 23.58% year over year, and tax-equivalent net interest margin reached 3.50%. Loans held for investment were $13.38 billion, an increase of $1.97 billion, or 17.23%, compared to September 30, 2024.

IX. The TowneBank Ecosystem: More Than Just Banking

TowneBank doesn’t really behave like a typical regional bank that just takes deposits and makes loans. Over the years, it’s built an entire bench of affiliated businesses designed to meet customers wherever money gets complicated: Towne Wealth Management, Towne Insurance Agency, Towne Benefits, TowneBank Mortgage, TowneBank Commercial Mortgage, Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices RW Towne Realty, Towne 1031 Exchange, LLC, and Towne Vacations.

That list can sound like a grab bag until you look at it through TowneBank’s lens. This isn’t diversification for its own sake. It’s an ecosystem strategy: surround the core banking relationship with adjacent services, deepen trust, and make the relationship stickier over time.

Insurance is the clearest example of how meaningful that second engine has become. On an annual basis, the insurance segment’s gross revenue surpassed its $100 million target in 2023, coming in at $109.46 million. In 2025, it continued to grow: Towne Insurance revenue was $31.7 million in Q1 2025 (up from $30.1 million in Q1 2024) and $30.9 million in Q2 2025 (up from $29.6 million in Q2 2024). The insurance segment also posted a compound annual growth rate of 11.7% from 2018 to 2024, supported by 27 acquisitions since 2001. TowneBank notes that Towne Insurance is the largest bank-owned insurance company in the country.

Mortgage adds another on-ramp into the franchise, and another reason for customers to stay. Residential mortgage banking income was $13.56 million in the second quarter of 2025, compared to $13.42 million in the second quarter of 2024. Loan volume rose as well, to $671.47 million in Q2 2025 from $626.98 million in Q2 2024.

Then there’s Towne Vacations, the property management division—an unusual business for a bank, but one that throws off diversified fee income. In Q2 2025, Towne Vacations generated net income of $15.6 million, up from $14.3 million in Q2 2024, and it operated across North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland, Tennessee, and Florida.

The real magic is how these pieces reinforce one another. If you’re a business owner with operating accounts at TowneBank, insurance through Towne Insurance, a mortgage through TowneBank Mortgage, and wealth managed by Towne Wealth Management, you’re not just a “customer.” You’re woven into a web of relationships. Each additional service becomes another thread—another reason not to move, another reason to pick up the phone and call your Towne banker first.

That strategy has coincided with strong compounding over time. TowneBank’s earnings growth CAGR was 22.7% from FY2000 to FY2024, and as of June 30, 2025, its 10-year total shareholder return was 178%. Multiple revenue streams—banking, insurance, mortgage, property management, and wealth—create more ways to grow than a plain-vanilla bank has available.

But there’s a tradeoff. Once you build a mini-conglomerate, you invite a classic question: does the market actually give you credit for the parts, or does it discount the whole because it’s harder to analyze? For TowneBank, that “conglomerate discount” question hangs over the ecosystem strategy—and it matters if you’re trying to understand what the company should trade for.

X. Competitive Landscape and Market Position

In Hampton Roads, TowneBank still sits on top. It holds just over a quarter of the region’s deposit market share, and it’s the hometown default for a lot of businesses that want decisions made locally, by people they actually know.

But the list of challengers has changed. The bank now staring up from the #2 position is Truist—North Carolina-based, newly massive, and the product of the 2019 SunTrust-BB&T megamerger. That’s the modern competitive reality in a single snapshot: TowneBank is fighting giants that keep getting bigger.

Which puts TowneBank in an unusual lane. It’s too large to be a classic community bank, but not large enough to compete nationally with the Bank of Americas and Wells Fargos of the world. Call it a “super-regional in the making”—a positioning that comes with real advantages, and very real exposure.

On the strength side, TowneBank has stayed #1 in deposit market share in Hampton Roads, and it’s earned plenty of external validation along the way. It’s been ranked on Forbes’ Best Banks list for seven consecutive years, and Forbes placed it at #9 on its 2022 Best Banks in America list—top among competitors in Virginia and North Carolina—using a framework that looks at growth, credit quality, and profitability. It has also been named one of the Best Banks to Work For by American Banker, ranking #1 among Virginia-based financial institutions and #7 among banks with $10 billion or more in assets.

But awards don’t win accounts. The day-to-day competitive battle is more practical.

Against the megabanks, TowneBank wins with the stuff big institutions struggle to deliver consistently: speed, relationships, and local decision-making. For a middle-market company, that can mean faster credit answers, bankers who understand the local economy, and access to real expertise without having to be a Fortune 500 client.

Against fintechs, TowneBank’s pitch is breadth and integration. A digital-first lender might be great at one product. TowneBank can offer the whole stack—commercial lending, treasury management, insurance, and wealth planning—wrapped around one relationship.

The pressure point is the middle ground. TowneBank can’t outspend the megabanks on technology. And it can’t always match the clean, frictionless digital experience that the best fintechs are built around. As expectations shift—especially for younger customers—the relationship model doesn’t disappear, but it has to keep proving it can be both high-touch and high-tech.

XI. Business Model Deep Dive and Unit Economics

To see why TowneBank has worked—and where the pressure points are—you have to look at the mechanics. Relationship banking isn’t just a vibe. It creates a very particular kind of P&L.

TowneBank runs the company through three main segments: Banking, Realty, and Insurance. Banking is the core—commercial and retail accounts, loans, treasury services, the daily operating relationship. Realty is the home-and-property side of the house: residential real estate services, mortgage banking, and title insurance. Insurance is the third leg: property and casualty insurance, benefits consulting, and risk management services.

In a bank like TowneBank, everything starts with the deposit franchise, because deposits are the raw material. When you have stable, relationship-based deposits, you can fund loans cheaper, hold the line on pricing, and keep your margin healthier when the cycle turns. You can see that in the recent net interest margin trend: net interest margin reached 3.17% in Q1 2025, up 15 basis points from the prior quarter and 42 basis points year over year. By Q3 2025, the bank reported a 3.50% tax-equivalent net interest margin.

The other pillar is credit. TowneBank’s calling card has long been conservative underwriting, and the recent numbers reflect that. Nonperforming assets were 0.04% of total assets, and the allowance for credit losses was 1.08% of loans—signals of a bank that’s still treating risk like something to be managed, not maximized.

Capital allocation is equally straightforward: stay well-capitalized, pay a regular dividend, and keep enough dry powder to grow—both organically and through acquisitions. TowneBank’s total risk-based capital ratio was 15.65%, comfortably above regulatory requirements.

Then there’s the tradeoff you can’t escape with relationship banking: it costs more to run. The executive officer model, the local boards, the community presence—those are real expenses, and they show up in the efficiency ratio. The good news is that TowneBank has been pushing it in the right direction, with its core efficiency ratio improving from 68.84% in FY2024 to 65.55% in Q1 2025.

Finally, because TowneBank has leaned back into acquisitions, the M&A math matters. Management expects the Dogwood acquisition to be approximately 8.0% accretive to 2027E earnings per share with fully phased-in cost savings. For the Old Point acquisition, TowneBank expects approximately 10% accretion to earnings per share once cost savings are fully implemented.

For long-term investors, two metrics tell you whether the story is staying on the rails:

Net Interest Margin (NIM): The spread between what TowneBank earns on loans and investments and what it pays for deposits and other funding. The margin has been expanding in the current rate environment, but what matters next is whether TowneBank can manage deposit costs as competition for deposits stays intense.

Non-Performing Assets / Total Assets: At 0.04%, this is exceptionally low—and it’s a window into the bank’s underwriting discipline. If this starts rising meaningfully, it’s often the earliest signal that the relationship model is being stretched, or that credit is turning faster than expected.

XII. Playbook: What Made TowneBank Work

If you strip away the quarterly reports and the branch maps, TowneBank’s story resolves into a handful of repeatable moves—principles that apply well beyond banking.

Timing paradox: TowneBank was born into uncertainty, and that turned out to be the edge. In 1998, starting a new community bank looked backwards. But consolidation and looming volatility created openings in three directions at once. Talent opened up as good bankers got displaced by mergers. Customers opened up as businesses were pushed into one-size-fits-all service models. And positioning opened up because a bank willing to bet on relationships, right when everyone else was betting on scale, stood out immediately.

Aligned incentives: Those more than 4,000 founding shareholders weren’t just a source of capital—they were the early customer base and the early ambassadors. When the people funding the bank also live in the community and plan to bank there, you get a different kind of accountability. And when board members are also customers and partners in the local economy, decisions tend to reflect long-term reputation, not short-term optics.

Counter-positioning against structural constraints: TowneBank’s advantage wasn’t that megabanks forgot about relationships—it’s that they’re structurally bad at delivering them consistently. Centralized credit boxes, standardized products, and efficiency-driven decision chains make it hard for a giant institution to empower local bankers the way TowneBank does. This isn’t a moral argument. It’s an architecture argument: certain organizational designs simply can’t behave like a relationship bank, even if they want to.

Disciplined M&A with cultural fit requirements: TowneBank’s acquisition strategy worked because it wasn’t just a hunt for assets—it was a hunt for fit. The discipline showed up in the deals it walked away from. Turning down “good on paper” targets that didn’t align culturally protected the thing that makes integrations succeed in banking: trust, continuity, and people who want to stay.

Ecosystem strategy: By surrounding the core banking relationship with insurance, mortgage, wealth, and real estate services, TowneBank made itself more useful and harder to replace. The value isn’t just cross-selling. It’s switching costs created through genuine integration—more touchpoints, more shared context, and more reasons a customer keeps calling the same team.

Crisis as opportunity: TowneBank repeatedly treated disruption as a recruiting and market-share moment. In 2008 and again in 2023, stress in the system pushed customers to ask who felt safe, and pushed talent to ask where they could still do their best work. TowneBank benefited from both—and the brand “the bank that survived” compounded.

Geographic focus: Even as it grew, TowneBank largely avoided the temptation to sprawl. It built density in connected markets—Hampton Roads, Richmond, and then down into the Carolinas—where local knowledge and relationship networks can actually reinforce each other. In relationship banking, focus isn’t just strategy. It’s how the model stays real.

XIII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

TowneBank competes in a knife fight—just with nicer suits.

On one side are the megabanks like Bank of America and Wells Fargo, with national brands, massive technology budgets, and the ability to price aggressively when they want a relationship. On another are the regionals—Truist, Atlantic Union Bank, and others—fighting for the same middle-market companies and the same team of proven commercial bankers. Then there are fintechs, picking off individual products with slicker UX and faster onboarding. And credit unions, using tax-advantaged economics to offer consumers better rates and cheaper fees.

TowneBank’s edge in this rivalry is the thing it has always sold: depth of relationship, speed of local decision-making, and a broader set of services that can wrap around a customer. But none of that is set-and-forget. Relationship banking only stays a moat if you keep earning it—one call returned, one problem solved, one renewal handled cleanly, year after year.

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-HIGH

Starting a full-service bank is still brutally hard. You need serious capital, regulatory approval, experienced leadership, and patience—because building deposits and trust takes time. That keeps true “new banks” from popping up like software startups.

But banking isn’t one business anymore. It’s a bundle. And fintech has made it much easier to enter individual slices of that bundle. A startup can launch a lending platform, a payments product, or a wealth app without a branch network or a traditional loan officer model.

That’s the tension: TowneBank’s deposit franchise is difficult to replicate from scratch, which protects the core. But because banking has been unbundled, new entrants can still attack the most profitable verticals without carrying the full weight of running a regulated, full-service bank.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MEDIUM

In banking, your “suppliers” are mainly two groups: depositors, who provide the funding, and talent, who provides the judgment and relationships.

Both have gained leverage in the digital era. Depositors can shop rates instantly, and moving money is easier than it used to be. Meanwhile, the people you need to compete—specialists in technology, compliance, and high-end commercial banking—are expensive, and they know it.

Then there’s the quieter supplier: core technology vendors. There aren’t endless great options, and switching is painful, slow, and risky. That makes vendor power feel moderate even when the relationship looks like a standard contract on paper.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

TowneBank’s best customers—the larger commercial ones—are also the most demanding. They know they have alternatives, and they negotiate hard on price, structure, and service expectations.

Smaller businesses and consumers tend to be more loyal, especially when the relationship model is real and multi-product. But even here, buyer power has risen. Fintech options are everywhere, and pricing transparency—especially around interest rates—has made shopping around easier across every customer segment.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

This is the most persistent pressure on TowneBank’s model: customers don’t always need “a bank” for each financial job anymore.

Fintech products can substitute for pieces of the relationship—payments, lending, wealth management. Larger companies can bypass banks altogether by tapping capital markets directly. Even crypto and alternative finance, despite all their volatility, represent another set of substitutes in the broader sense: different ways to store value, move money, and access liquidity.

What softens the blow is complexity. When a customer’s needs span commercial lending, treasury management, insurance, and wealth planning, coordination matters—and full-service, integrated banking still has real value. But the unbundling isn’t theoretical. It’s ongoing, and it keeps pushing banks to prove why the bundle should stay together.

XIV. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

TowneBank has reached a size where the fixed costs of modern banking—technology, compliance, cybersecurity, marketing—can be spread across a much larger balance sheet than a typical community bank. That scale matters. It’s a big reason the relationship model can still work profitably in 2025.

But it’s also a reminder of the ceiling: TowneBank is not a megabank. It can’t match the national giants on raw cost efficiency or outspend them on technology. Its scale advantage is real—just regional, not absolute.

2. Network Economies: LOW

Banking isn’t a classic network-effect business. More TowneBank customers don’t inherently make TowneBank more valuable to other TowneBank customers the way they would on a social network or a marketplace.

There is a softer “ecosystem” effect: the more services TowneBank can connect—banking, insurance, mortgage, wealth—the more useful the relationship becomes. But that’s integration value, not true network economies.

3. Counter-Positioning: HISTORICALLY STRONG, NOW FADING

From 1999 through the post-crisis years, TowneBank benefited from a very real structural asymmetry: the megabanks couldn’t simply “decide” to behave like a relationship bank without breaking their own centralized, scale-driven machines.

That edge has faded. Plenty of banks now market themselves as relationship-driven, and customers have been trained by digital-first players to expect instant convenience for many everyday needs. TowneBank can still differentiate on service, but “relationship” is no longer as rare—or as unanswerable—as it was in the early years.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

For businesses, switching banks is painful. You’re not just moving money—you’re rewiring operations: operating accounts, treasury management, payments, vendor files, borrowing relationships, and all the day-to-day workflows that keep a company running. You also lose the accumulated context: the banker who already knows how your business works, what your seasonality looks like, and what you’re trying to build.

TowneBank’s ecosystem raises the friction. If a customer has banking plus insurance, mortgage, and wealth management all tied together, leaving isn’t a single decision—it’s a multi-step unwinding.

For consumers, switching costs are lower, but they’re not zero. Direct deposit, autopay, and familiarity with digital tools create enough hassle that many people stick with what works unless they have a strong reason to move.

5. Branding: MODERATE (LOCAL)

In Hampton Roads, TowneBank’s brand is strong and specific: it’s the hometown bank that feels local and present, and “Virginia’s Bank” actually means something.

That brand power is less automatic in newer markets. Still, the company has been building recognition outside its core. For example, it was voted Gold in the bank category in the 2025 edition of Charlotte's Best, the second consecutive year to earn that distinction. The bigger point stands: TowneBank’s brand is an asset, but it’s strongest where the relationships are deepest.

6. Cornered Resource: LOW-MODERATE

TowneBank’s most valuable “resource” is the hardest to put on a balance sheet: the trust and local knowledge sitting inside its teams and their relationships. That’s meaningful—and it compounds.

But it isn’t fully cornered. Bankers can be hired away. Competitors can build relationships over time. Even the deposit franchise, while valuable, isn’t exclusive in the way a patent or a proprietary network might be.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

TowneBank has real process advantages that show up across cycles: conservative underwriting, a repeatable M&A integration approach, and a decentralized model that still coordinates like a single institution. These processes are the product of decades of iteration—and they’re not easily copied overnight.

At the same time, none of this is magic. A disciplined competitor can learn a lot of the same playbook. TowneBank’s advantage is in execution and consistency, not an uncopyable invention.

Overall Power Assessment: TowneBank’s moats are moderate, anchored most strongly in switching costs created by deep, multi-product relationships—and supported by a counter-positioning advantage that used to be sharper than it is today. The challenge now is keeping those powers durable as technology raises customer expectations and makes parts of banking easier to unbundle.

XV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Demographic tailwinds: TowneBank is planted in places that are still gaining people and businesses. Virginia and the Carolinas have been growing faster than the country overall. Hampton Roads continues to benefit from a durable military presence. And markets like the Research Triangle and Charlotte keep attracting talent, capital, and new companies—exactly the kind of long-run momentum a relationship bank can compound with.

Relationship banking endures: For complex commercial customers, banking still isn’t a single product—it’s a set of ongoing problems that need judgment and speed. Treasury management, customized lending, and coordinating across banking, insurance, and wealth aren’t easy to replace with an app. And 2023 was a live-fire test: when confidence cracked across the system, banks with real relationship deposits generally held up better than banks built on rate-shopping, transaction-only accounts.

M&A runway: Consolidation hasn’t stopped—it’s just become the background music of the industry. That leaves a steady pipeline of potential acquisitions. TowneBank has also shown it can integrate without breaking what it buys, because it’s willing to prioritize cultural fit and keep local leaders in place. The announced Dogwood deal, in particular, meaningfully extends the bank’s growth runway in the Carolinas.

Ecosystem revenue diversification: TowneBank isn’t purely a spread business. Insurance and wealth management generate fee income that doesn’t move in lockstep with interest rates, helping smooth earnings and giving the company more than one engine to grow.

Credit discipline: TowneBank’s brand has been built on boring, conservative underwriting—and in banking, boring is often the point. The 0.04% nonperforming asset ratio signals real credit quality and suggests the bank has kept its risk culture intact even as it has grown.

Valuation opportunity: Regional banks frequently trade at depressed valuations, sometimes for good reasons and sometimes because the market paints the whole group with the same brush. If TowneBank keeps executing—growing, managing credit, and improving efficiency—there’s a plausible path for valuation improvement alongside earnings growth.

Leadership depth: The transition from Aston to Foster is a reminder that the company isn’t only one founder’s force of will. If culture is TowneBank’s asset, the early evidence suggests it can carry into the next generation of leadership.

The Bear Case

Size challenges: TowneBank sits in a tough middle lane—no longer small enough to live purely on “community bank” goodwill, but not large enough to match megabanks on technology budgets or pricing power. That’s the classic squeeze risk: attacked from above by giants and from below by specialists.

CRE exposure: Commercial real estate is the big flashing caution light for the entire regional bank sector, and TowneBank isn’t exempt. Many banks have learned the hard way that CRE concentrations can turn quickly, especially if office fundamentals stay weak. TowneBank’s relationship model can help it spot problems earlier, but concentration risk is still concentration risk.

Margin pressure: The current rate environment has been supportive for margins, but cycles turn. If rates normalize and deposit competition stays intense, funding costs can rise faster than asset yields—and net interest margin can compress.

Technology gap: TowneBank can’t outspend megabanks or the best fintechs. If the digital experience falls behind, especially for younger customers and tech-forward businesses, the bank risks losing relationships before they ever become relationships.

Fintech disruption: Banking keeps getting unbundled. Payments, lending, and wealth management are all being attacked by focused competitors that don’t need to run a full-service balance sheet to take profitable slices of the pie.

M&A dependency: If organic growth slows, acquisitions become the lever—and that comes with two problems: prices can be high, and integrations always carry risk. Even a strong integration playbook can’t eliminate the chance of overpaying or misjudging a cultural fit.

Leadership transition risk: The first succession—from Aston to Foster—looks orderly. The harder test is whether TowneBank can keep the founder-era culture consistent through multiple leadership generations and across a wider geographic footprint.

Geographic concentration: TowneBank’s footprint is still heavily tied to Virginia and the Carolinas. That focus is a strength, but it also concentrates exposure to regional economic swings, potential Navy budget changes, and localized real estate downturns.

Efficiency ratio: Relationship banking is expensive. Local leadership, high-touch service, and a broader ecosystem cost real dollars. To justify that cost structure, the bank has to keep earning a premium—through pricing, credit performance, or growth—because it won’t win by being the lowest-cost provider.

XVI. What Would Have Happened Otherwise

Counterfactual thinking is a good way to measure TowneBank’s real contribution, because it forces the question: what, exactly, did it replace?

If TowneBank had never existed, Hampton Roads would almost certainly be a market dominated entirely by out-of-state megabanks, with credit decisions pushed to regional centers in places like Charlotte or Atlanta. The businesses that depended on speed, flexibility, and a banker who could actually say yes would have had two options: accept slower, more standardized processes, or piece together financing elsewhere.

Could another local bank have stepped in and filled the gap? Virginia’s own history argues no. As one observer put it: “This is the last chance for Virginia to have a statewide, independent regional bank. There aren't enough small banks left to where you could sew them together to re-create another one.”

And then there’s the human side. The 43 founders who met in Aston’s garage wouldn’t have built something together. They would have scattered—into other banks, other industries, other chapters—taking decades of local banking judgment with them. The capital that became TowneBank would have flowed somewhere else too, likely into investments with less direct attachment to the community.

For Hampton Roads, that difference compounds. A small business that got a fast credit decision from a local banker might instead have waited weeks for an answer from a distant committee. Some deals would have died on the vine. Some expansions would have been delayed. Not every lost opportunity shows up in a statistic, but the ripple effects are real.

Now flip the counterfactual the other way: what if TowneBank had stayed small and never leaned into acquisitions? In a state where hometown banks were getting absorbed one after another, it’s hard to imagine TowneBank remaining independent for long. It likely would have been bought too—another Virginia name folded into an out-of-state balance sheet—with the relationship model surviving just long enough to be “rationalized” away.

And what if TowneBank had tried to go national instead of building contiguously? The very thing that made it work—deep local knowledge and a culture that stays personal—would have been the first casualty. Relationship banking doesn’t scale infinitely. Once you stretch it across thousands of miles, it stops being a relationship and turns back into a brand promise.

XVII. Lessons for Founders and Investors

For Founders

Timing paradox: Don’t wait for perfect conditions. TowneBank was built on the idea that uncertainty isn’t just risk—it’s opportunity. In messy moments, talent gets dislocated, customers start looking around, and incumbents get distracted protecting what they already have.

Skin in the game: Align incentives early and make it real. TowneBank’s more than 4,000 founding shareholders weren’t abstract investors—they were neighbors and future customers. That kind of ownership structure doesn’t just fund a business; it sets the tone for how the business behaves for decades.

Focus on what big players can’t do: Don’t try to beat giants at their own game. The megabanks can offer scale, but they’re structurally bad at consistent, locally empowered relationship banking. TowneBank didn’t outspend them. It sidestepped them—by building where their org charts and credit boxes couldn’t flex.

Culture as competitive advantage: Culture sounds soft until you watch it compound. TowneBank treated “the Towne Way” like an operating system, not a slogan—and that’s why it could survive both geographic expansion and a major leadership transition without losing its identity.

Strategic patience: Real relationships aren’t hackable. Transaction banking can win quick, copyable business. Relationship banking wins the slow way—by stacking years of trust until customers stop shopping and start calling you first.

M&A discipline: In banking, overpaying is the silent killer. TowneBank’s edge wasn’t just doing deals—it was having the discipline to walk away when the price or the culture didn’t fit, protecting the integration track record that made the next deal possible.

Ecosystem thinking: Build adjacency with intention. Banking plus insurance plus mortgage plus wealth isn’t just cross-selling; it’s becoming more useful. Each added service deepens context, increases convenience, and raises the friction of leaving—because the customer isn’t tied to a product, they’re tied to a team.

For Investors

Business model durability: TowneBank is a bet that relationship banking remains valuable even as fintech evolves from “apps” to AI-driven platforms. Relationship banking held up through fintech 1.0; whether it holds through fintech 2.0 is still an open question.

Management quality: In banks, management is the product. TowneBank’s long-term credit discipline, its ability to integrate acquisitions, and its commitment to culture are evidence of something investors rarely get to see clearly: consistent decision-making across cycles.

Local monopolies: Geographic dominance still matters. TowneBank’s #1 deposit share in Hampton Roads isn’t just a bragging right—it’s a source of resilience, low-cost funding, and brand gravity in its home market.

Crisis reveals quality: Marketing can claim discipline; crises prove it. TowneBank’s ability to navigate both 2008 and the 2023 regional-bank panic is the clearest validation that its conservative underwriting and relationship deposits are more than a narrative.

The “boring is beautiful” insight: The banking strategies that sound exciting often end in write-downs. TowneBank’s “boring” focus—relationships, conservative credit, steady expansion—looks less thrilling, but it’s the kind of boring that tends to survive.

Deposit franchises: In a world where money can move in seconds, deposits that don’t move are worth a premium. TowneBank’s relationship model is ultimately a deposit strategy: build trust, embed into operations, and create funding that’s stickier than the highest rate on the internet.

XVIII. The Future: What's Next for TowneBank

TowneBank heads into 2026 at a strategic crossroads. In the span of a year, it has been back on the acquisition trail—three transactions either already completed or still in motion—and on a pro forma basis, it’s approaching roughly $22 billion in assets. That’s a very different company than the one that started in a Portsmouth garage.

The Dogwood deal is the clearest statement of intent. If it closes as expected in early 2026, the combined TowneBank-Dogwood company would be about a $22 billion institution, materially widening TowneBank’s reach across the Carolinas and taking it into South Carolina for the first time. The map gets bigger, the integration work gets harder, and the stakes rise with it.

At the same time, the digital transformation imperative hasn’t gone away—if anything, it’s gotten louder. TowneBank has to keep investing in technology to meet modern expectations while preserving the relationship overlay that differentiates it from digital-first competitors. It isn’t an either/or choice. It’s both. And “both” demands sustained spending, constant execution, and a culture willing to evolve without losing its center.

Geographically, the next moves are still open-ended. TowneBank can keep densifying markets it already knows. It can keep pushing down the I-85 corridor. Or it can consider new states like Tennessee or Florida. Each path has a different risk-reward profile, and each tests the same question: how far can you stretch a culture built on local trust before it starts to thin out?

The business model itself will also get tested by demographics. Relationship banking worked brilliantly with customers who grew up expecting to sit across a desk from their banker. But younger owners may define “relationship” differently—more responsive, more digital, less tied to face-to-face meetings. TowneBank’s challenge is to translate its core values into the channels and behaviors the next generation expects, without turning the model into just another marketing line.

Then there’s the long game of leadership. The Aston-to-Foster transition looked smooth, but maintaining founder-era culture across multiple generations of leadership is historically difficult. Over time, succession becomes less about a single handoff and more about whether an organization can keep selecting, training, and rewarding the same kind of leadership that built the franchise.

All of which leads to the ultimate strategic question: is TowneBank built to be independent forever—or is it eventually a target? At its current scale, it would be meaningful to a larger regional bank that wants a stronger Virginia-and-Carolinas presence. But it’s also now large enough to keep doing what it has been doing: remain independent, keep acquiring, and keep building.

In fact, TowneBank was one of the acquirers that completed at least two bank purchases in 2025, joining a list that included Farmers Bancorp Inc., Cadence Bank, First Financial Bancorp., Glacier Bancorp Inc., Michigan State University FCU, and Seacoast Banking Corp. of Florida.

There’s one more possibility on the table: a merger of equals that creates a true super-regional. The logic is easy to see—combine with another relationship-focused regional, get scale, spread costs, and stay culturally aligned. The hard part is also easy to see: finding a true match, at the right price, with the right chemistry, is rare. And in banking, “almost aligned” is often where deals go to die.

XIX. Epilogue: The Hometown Banking Experiment

Twenty-five years ago, in a two-car garage in Portsmouth, Virginia, a group of veteran bankers made a bet that most of the industry would have laughed off. Relationship banking was supposedly finished. Scale was the only way to win. Local decision-making was treated like an expensive relic.

TowneBank’s answer was to do the opposite—and to do it with real commitment. On April 8, 1999, it opened for business with three offices and the backing of nearly 4,000 local shareholders who invested nearly $50 million to make the idea real.

So far, the hypothesis has held. TowneBank went from zero deposits to nearly $20 billion in assets, from a handful of locations to a footprint spanning Virginia and North Carolina, with South Carolina next on the map. In an era when community banks were disappearing, TowneBank demonstrated that local knowledge and genuine relationships could still compete—and even compound.

But the story isn’t a victory lap for the past. Technology is non-negotiable now. The win condition isn’t choosing relationships over digital; it’s delivering both at once. The banks that make it through the next 25 years won’t just be trusted. They’ll be easy to use, secure, fast, and modern—while still feeling human.

And that’s why TowneBank’s story matters beyond banking. It points to a bigger set of questions: can regional players survive in industries dominated by giants and disruptors? Does “community focus” actually serve communities, or is it nostalgia dressed up as strategy? What should financial institutions be—local partners in economic life, or pure capital allocators optimized for efficiency?

The surprise in TowneBank’s arc is real. A bank founded in 1999—built by a man who started in banking as a high school kid getting coffee—grew into one of the standout regional bank stories of the 21st century, despite the direction the entire industry was moving.

TowneBank’s next chapter will help answer whether there’s a durable future for the middle ground in American banking. If it keeps thriving, it’s proof that relationship banking isn’t a temporary holdout—it’s a permanent advantage when executed well. If it stumbles, it may mean consolidation didn’t lose. It just took longer than anyone expected.

Either way, the experiment that started in that Portsmouth garage—and the thousands of shareholders and bankers who believed in it—remains worth studying. Because for all the abstraction in modern finance, banking still comes down to something very old-fashioned: people trusting other people with their money, and what those people choose to do with that trust.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music