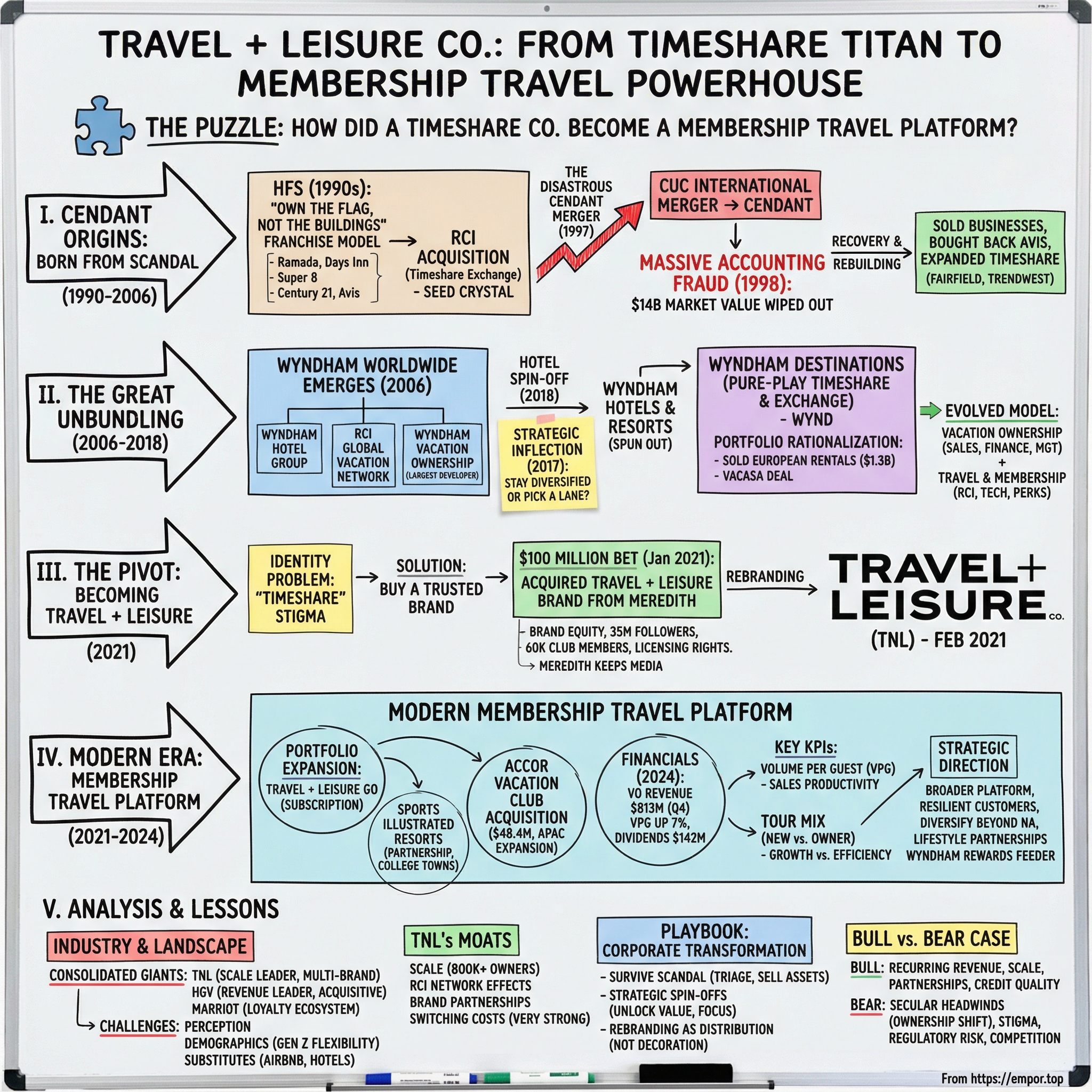

Travel + Leisure Co.: From Timeshare Titan to Membership Travel Powerhouse

I. Introduction: The Puzzle of the Vacation Empire

Picture it: late 2024. In Orlando, Florida, the headquarters of the country’s largest vacation ownership company runs like an air-traffic control tower for leisure travel. Travel + Leisure Co. helps deliver more than six million vacations a year. Its Vacation Ownership portfolio spans 270-plus resorts worldwide, anchored by big-name vacation club brands and serving more than 800,000 owners.

Financially, it’s not a niche business hiding in the shadows. In 2024, Travel + Leisure Co. reported net revenues of $3.864 billion and net income of $411 million. It trades on the NYSE as TNL. And that’s what makes the whole thing so intriguing: this company sits at the center of an industry many people write off as outdated, high-pressure, or worse—yet it has managed to present itself as something closer to a modern leisure travel platform.

So that’s the puzzle we’re going to solve. How did a timeshare business—born out of one of the biggest corporate fraud scandals in American history, reshaped through multiple spin-offs, and constantly fighting the stigma attached to its category—end up as a brand that wants to be associated with “membership travel” instead of “timeshare sales”?

The path runs straight through the rise and fallout of one of the most aggressive conglomerate builders of the 1990s, a series of carefully executed corporate separations, and a blunt, audacious move: spending $100 million to buy the Travel + Leisure name and, with it, a chance to rewrite what customers think the company is.

It all traces back to 1990, with the formation of Hospitality Franchise Systems, or HFS. HFS started in the unglamorous business of hotel franchising and later expanded into vacation exchange. But what happened between that origin story and the company you see today is the real masterclass—one that blends Blackstone-era dealmaking instincts, late-’90s merger mania, a scandal that erased $14 billion in market value, and eventually a strategic decision to split hotels from timeshares and double down on the economics of vacation ownership.

Along the way, we’ll dig into why the timeshare model—despite its reputation—can be so durable and so profitable, and whether Travel + Leisure Co.’s shift toward a broader membership travel platform is a true reinvention… or the most sophisticated rebrand the industry has ever seen.

II. The Cendant Origins: Born from Scandal (1990-2006)

The HFS Empire-Building

In 1990, the hotel industry was bruised. Real estate values had fallen hard, properties were trading at distressed prices, and most capital wanted nothing to do with lodging.

Henry Silverman saw the opposite: a once-in-a-cycle buying window.

That same year, The Blackstone Group formed Hospitality Franchise Systems, or HFS, and tapped Silverman—an attorney-turned-investment banker with deep lodging experience, and the former CEO of Days Inn—to lead the effort. The plan wasn’t to buy hotels. It was to buy something far more scalable: brands.

Silverman’s insight was simple and powerful. Don’t own the buildings. Own the flag.

HFS would purchase underperforming or undervalued franchise brands (or just the rights to their names), then make money by charging franchisees upfront and ongoing fees in exchange for marketing, reservations, and administrative support. The franchisees carried the costs and risks of owning and operating the properties. HFS collected the royalties.

That asset-light model—high-margin fees with minimal capital tied up in real estate—let HFS move fast.

In 1990, it bought Howard Johnson’s and the U.S. rights to the Ramada brand from Prime Motor Inns for $170 million. In 1992, it bought the Days Inn franchise out of bankruptcy for $290 million, which helped make HFS the largest hotel franchisor in the world, with brands licensed to roughly 2,300 hotels.

Blackstone took HFS public in December 1992. Through the 1990s, it became one of the fastest-growing companies of its size, and its stock climbed dramatically from the IPO price to a peak in 1998.

And Silverman didn’t stop at hotels. In 1993, HFS bought Super 8 for $125 million, plus the Park Inn brand. Then it expanded into real estate brokerage franchising—acquiring Century 21 from MetLife for $200 million in 1995, changing its name to HFS Inc. that same month, and following up with Electronic Realty Associates for $37 million and Coldwell Banker for $740 million.

The pattern was consistent: buy brands, build systems, collect fees.

Then came a move that matters a lot for this story’s endgame. True to its “own the system, not the operations” philosophy, HFS kept the Avis brand name and reservations system, while spinning out the corporate-owned car rental operations as Avis Rent a Car, Inc.

And around this time, HFS also bought Resort Condominiums International—RCI—a timeshare exchange service, for up to $825 million.

RCI was the world’s largest timeshare exchange network. At the moment, it probably looked like just another fee-based membership business. In hindsight, it was a seed crystal: the earliest piece of what would eventually become Travel + Leisure Co.’s vacation ownership empire.

The Disastrous Merger

By 1997, Silverman had become a Wall Street favorite. HFS was a machine: a growing portfolio of franchise and membership businesses throwing off fee income without the capital intensity of owning the underlying assets.

Then came the deal that nearly blew it all up.

In late 1997, HFS agreed to merge with CUC International, a direct marketing company behind discount membership programs like Shoppers Advantage and Travelers Advantage. On December 18, 1997, the companies completed a “merger of equals,” creating Cendant Corporation. The combination was valued around $14 billion, and Silverman became CEO.

But in a critical leadership shift, Silverman also said he would step back from day-to-day management and move into the chairman role, while CUC founder and CEO Walter Forbes took the top operating seat.

It didn’t take long for that decision to look disastrous.

In April 1998—just months after the merger—Cendant disclosed that it had uncovered massive accounting improprieties tied to CUC. The fraud was enormous. Revenue had been inflated by roughly $500 million over three years. Reported profits turned into losses once the numbers were corrected.

When the news went public, the market reaction was instant and brutal. Cendant’s stock collapsed from the low $40s to around $12, wiping out about $14 billion in market value. At the time, it was one of the largest accounting fraud cases in U.S. history, and an early flashpoint in the era of corporate scandals that would later define the early 2000s.

The legal consequences were severe. Walter Forbes was sentenced to 12 years and seven months. E. Kirk Shelton, CUC’s vice chairman, received a 10-year sentence. Both were ordered to pay $3.275 billion in restitution.

Recovery and Rebuilding

Once the fraud was exposed, the board forced Forbes out. Silverman stepped back into the CEO role, and Cendant went into triage.

What followed was a disciplined rebuild. Cendant sold businesses to reduce debt and stabilize the company. It also started making targeted moves that would shape its long-term identity.

It re-acquired the operations of Avis Rent a Car for $937 million. It pushed into travel distribution by acquiring Galileo International for $2.9 billion and Cheap Tickets for $425 million.

And then, crucially, Cendant went deeper into timeshare—not just exchanging weeks through RCI, but selling and managing vacation ownership itself. It acquired Fairfield Communities for $690 million and Trendwest Resorts for $980 million.

Those two deals mattered more than they probably seemed at the time. Fairfield and Trendwest became the backbone of what is now Travel + Leisure Co.’s vacation ownership business. While headlines fixated on the scandal and the cleanup, Cendant was quietly assembling the pieces of a timeshare powerhouse.

In retrospect, the Cendant era is the first great irony of this story: the fraud forced a restructuring, and the restructuring set the company on the path that—through spin-offs and reinvention—eventually produced the modern Travel + Leisure Co.

III. The Great Unbundling: Wyndham Worldwide Emerges (2006-2018)

The Cendant Breakup

By 2005, Cendant had done the hard part: it survived the scandal, paid the price, and rebuilt credibility. But it was still a corporate junk drawer—hotel flags, timeshares, car rentals, real estate brokerage, and travel distribution all living under one ticker. Henry Silverman’s conclusion was classic Silverman: the sum was worth more as pieces than as a pile.

So Cendant split itself apart.

The real estate brokerage business became Realogy. The travel distribution unit, Travelport, went to The Blackstone Group. The hospitality services division—hotels, vacation ownership, and exchange—became Wyndham Worldwide. And the remaining shell of Cendant rebranded as Avis Budget Group, home to the car rental operations.

Wyndham Worldwide officially debuted on July 31, 2006, spun out from Cendant as the vehicle for its hotel and timeshare future.

Stephen P. Holmes, Cendant’s vice chairman and Wyndham’s new chairman and CEO, framed the move as more than a financial engineering exercise. Wyndham, he said, was a consumer-facing name with real pull—a corporate identity that could finally make the whole portfolio feel coherent to customers.

Inside the new company were three distinct engines:

Wyndham Hotel Group, one of the world’s largest hotel franchisors and a provider of hotel management services.

RCI Global Vacation Network, the operator of the world’s largest vacation exchange network, plus a major vacation rental network.

And Wyndham Vacation Ownership, already the world’s largest developer of vacation ownership resorts by owners and resorts.

Strategically, the case for unbundling was straightforward. These businesses didn’t just look different—they behaved differently. Hotel franchising was asset-light and capital-efficient. Timeshare required more capital, but it could produce substantial cash flow through financing and ongoing fees. Vacation rentals sat somewhere else entirely. Different investors value those models differently, and Cendant finally let each one stand on its own.

Building the Timeshare Giant

Once Wyndham Worldwide was on its own, the mandate was clear: keep building scale in vacation ownership.

In 2013, Wyndham acquired Shell Vacations Club for $102 million, plus $153 million of assumed debt. It kept consolidating brands and experiences under the Wyndham umbrella, building a portfolio that included Club Wyndham, WorldMark, and a growing set of lifestyle partnerships.

But timeshare scale comes with a shadow: sales practices. In 2016, Wyndham Vacation Resorts became the subject of investigations into its sales tactics in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. The Pennsylvania Real Estate Commission fined Wyndham and its broker at the Shawnee-on-Delaware location, Craig Roberts, a total of $15,000. Eight months earlier, Wyndham had settled similar allegations in Wisconsin, paying $655,000 in restitution to 29 consumers.

It was a reminder of the tightrope the entire category walks. The sales machine is the growth engine—but it’s also the reputational risk that never really goes away.

The Strategic Inflection Point

By 2017, Wyndham Worldwide had a bigger question to answer: stay diversified, or pick a lane?

In August 2017, Wyndham announced it would spin off its hotel division into a separate publicly traded company—leaving the remaining business as a pure-play timeshare and vacation exchange company. The separation became official on May 31, 2018, when Wyndham Hotels & Resorts was spun out to shareholders and what remained of Wyndham Worldwide was renamed Wyndham Destinations.

On paper, that choice looked counterintuitive. Hotel franchising was cleaner, simpler, and generally better regarded. Timeshare was more controversial and more complex.

But economically, timeshare had an advantage Wyndham didn’t want to give up: recurring revenue. Financing income, management fees, and exchange services created cash flows that didn’t depend solely on filling rooms night after night. The company could generate positive cash flow from maintaining and servicing its ownership base in a way that traditional lodging businesses simply couldn’t replicate.

Leadership mattered here, too. Michael D. Brown joined the company in 2017, coming from Hilton Grand Vacations with deep vacation ownership experience. In June 2018, he led the evolution of the newly independent Wyndham Destinations, headquartered in Orlando—positioned to push the business beyond being just “the timeshare unit,” and into whatever came next.

IV. The Pivot: Becoming Wyndham Destinations (2018)

The Hotel Spin-Off

The separation became real on May 31, 2018. Wyndham Worldwide officially completed the spin-off of Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, and the company left behind didn’t just get smaller—it got sharper. It renamed itself Wyndham Destinations, began trading under the ticker WYND, and positioned itself as the world’s largest vacation ownership and exchange company.

This wasn’t a modest footprint. Wyndham Destinations now had a global presence across 110 countries, with more than 220 vacation ownership resorts and access to roughly 4,300 affiliated exchange properties through its network.

Michael D. Brown, now president and CEO, framed the moment as the payoff from a decade of building scale—and a starting gun for the next phase: a focused, pure-play company with a leading position and room to grow.

For shareholders, the mechanics were clean: for every share of Wyndham Worldwide they owned, they received one share of Wyndham Hotels stock. Investors could keep exposure to both paths—hotel franchising on one side, vacation ownership and exchange on the other—while each company ran its own playbook.

Portfolio Rationalization

With the hotel business gone, Brown moved quickly to simplify what remained. The theme was focus: shed the parts that didn’t fit, and double down on ownership and exchange.

First up was Europe. In 2018, Wyndham sold its European vacation rentals business to an affiliate of Platinum Equity for about $1.3 billion. This wasn’t a tiny carve-out—it was described as Europe’s largest manager of holiday rentals, spanning more than 110,000 units across 600-plus destinations in more than 25 countries, and operating a roster of local brands including cottages.com, James Villa Holidays, Landal GreenParks, Novasol, and Hoseasons.

Then came North America. In 2019, Vacasa entered into an agreement to purchase Wyndham Vacation Rentals for about $162 million, a deal expected to close that fall subject to customary conditions. For Vacasa, it meant more inventory and a broader footprint. For Wyndham Destinations, it was another step in a deliberate exit.

The message was clear: Wyndham Destinations was choosing not to fight the increasingly crowded vacation rental war—where Airbnb and other platforms were reshaping consumer expectations—and instead to concentrate on the business it believed it could own: vacation ownership and exchange.

The bet was on stickiness. Rentals can be booked and abandoned with a click. Timeshare customers, once acquired, tend to stay in the system—generating recurring fees and financing income year after year.

The Business Model Evolution

After the portfolio cleanup, Wyndham Destinations increasingly looked like a company built around two engines: Vacation Ownership and Travel & Membership.

Vacation Ownership was the core. It covered the marketing and sale of vacation ownership interests, consumer financing, and the property management services that kept the resorts running.

Travel & Membership was the network layer. It included the RCI exchange business, membership travel products, and the technology platforms that helped manage bookings and benefits.

To understand why this model can be so durable, you have to understand the financing. Many buyers don’t pay for their vacation ownership interest all at once—they finance a meaningful portion through Wyndham itself, often at interest rates well above prime. That creates a receivables portfolio that throws off interest income, turning the company into a specialized lender to its own customer base. The health of that portfolio—defaults, credit quality, and the underlying FICO mix—directly affects profitability.

Operationally, one metric tells you whether the machine is humming: Volume Per Guest, or VPG. It’s the average sale generated per sales tour, and it effectively bundles the whole sales funnel into one number—how many tours you generate, how often you close, and how big the average purchase is. Improve VPG while keeping acquisition costs under control, and the model scales. Lose control of either side, and the economics get ugly.

V. The Brand Acquisition Gambit: Becoming Travel + Leisure (2021)

The Strategic Vision

By 2020, Wyndham Destinations had an identity problem hiding in plain sight. The business might have been humming—resorts, exchange, financing, recurring fees—but the name on the door still translated the same way to a lot of consumers: timeshare.

And “timeshare,” fairly or not, comes with baggage. Years of consumer perception research pointed to the same set of objections: high-pressure sales, difficulty exiting, and ugly resale stories. Even people who genuinely liked their ownership often didn’t want to recommend it to friends. The product could work; the reputation wouldn’t.

Michael D. Brown and his team concluded that if the company wanted to grow beyond its core base, it needed to stop looking like a timeshare company first and a travel company second. Their solution was bold and simple: buy a travel brand that already meant something—and use it to pull the whole company up the value chain, from “vacation ownership seller” to “membership travel platform.”

The $100 Million Bet

On January 6, 2021, Wyndham Destinations and Meredith Corporation announced a deal that sounded, at first blush, almost like a category error: Wyndham Destinations was acquiring the Travel + Leisure brand and related assets from Meredith for $100 million.

The payment was structured to be manageable: $35 million in cash at closing, with the remainder paid over time through June 2024. Wyndham also agreed to a five-year marketing commitment across Meredith’s broader portfolio.

Brown sold the logic plainly. Travel + Leisure brought reach—about 35 million followers across platforms—and a base of nearly 60,000 travel club members. More importantly, it brought permission. The brand had decades of credibility, and the company wanted that credibility to rub off on everything it sold next.

The structure, though, was the truly unusual part. Meredith kept the media operation. It would continue to publish and monetize Travel + Leisure across print and digital, including advertising and marketing, under a 30-year, royalty-free, renewable licensing arrangement. Wyndham wasn’t buying a magazine business. It was buying the name, the clubs, the customer relationships, and the right to build new businesses under an aspirational banner.

In other words: they bought the brand equity, the audience, and the runway for licensing and membership products—without taking on the volatility of running a media company.

Management expected the deal to be neutral to earnings in year one and accretive in year two.

The Transformation Logic

This was a rebrand, but not the cosmetic kind. The bet was that “Travel + Leisure Co.” would be read differently—by customers and by Wall Street—than “Wyndham Destinations.”

Travel + Leisure had been shaping travel taste since 1971. It stood for aspiration, expertise, and a certain kind of polished authority. That’s exactly what the timeshare label struggled to convey.

The company’s plan was to use that brand as a platform for capital-light expansion: licensing deals, new branded travel services, and membership and subscription offerings that could grow without the capital burden of building more resorts.

On February 17, 2021, the change became official. Wyndham Destinations, Inc. renamed itself Travel + Leisure Co. and began trading under the new ticker symbol, TNL.

Internally, the business was organized into three lines: the legacy Wyndham Destinations vacation ownership operation; Panorama, which housed exchange and membership; and the Travel + Leisure Group, focused on licensing and media partnerships.

The skeptics’ question was obvious: is this brilliant repositioning—or just a shinier label on the same machine? Because the core economics still came from selling vacation ownership and financing it. But the acquisition did something real: it gave the company a trusted front door, and a credible story for new products and new customers who might never have clicked on anything called “Wyndham Destinations.”

VI. Modern Era: The Membership Travel Platform (2021-2024)

Portfolio Expansion

With Travel + Leisure on the sign, the company leaned hard into a multi-brand playbook: use a trusted consumer name to widen the top of the funnel, and offer more ways to “join” than a traditional timeshare purchase.

One early expression of that was Travel + Leisure GO, a subscription travel club positioned for customers who wanted curated trips and perks but weren’t ready to commit to ownership.

Then, in September 2023, the company made the strategy even more explicit with a headline-grabbing partnership: Sports Illustrated. Travel + Leisure Co. would bring its playbook for building and operating vacation clubs—development, distribution, and management—to a new Sports Illustrated-branded vacation club product. Geoff Richards, the company’s chief operating officer of vacation ownership, framed it as building “a custom club experience for passionate sports fans.”

The vision wasn’t just a logo slapped on an existing resort. The companies announced a network concept focused on college towns, and named the first planned location: Tuscaloosa, Alabama, across the Black Warrior River from the University of Alabama. The pitch practically wrote itself—Alabama’s sports tradition, the school’s long history of Sports Illustrated covers, and even the fact that Travel + Leisure had recently named Tuscaloosa one of the 25 best college towns in the U.S.

Michael D. Brown called the project “a tangible demonstration of our multi-brand strategy,” and said the company was “uniquely positioned” to build customized vacation club products with major brands and hospitality partners. The resorts were expected to be developed using an asset-light development financing model. The Tuscaloosa resort was anticipated to open in late 2025, with no immediate earnings impact—but with incremental growth expected to begin in the second half of 2025.

Geography was the other axis of expansion, and in early 2024 the company took a big swing overseas. Travel + Leisure Co. announced an agreement to acquire Accor’s vacation ownership business, Accor Vacation Club, for $48.4 million. The deal was expected to close in the first quarter of 2024 and to be immediately accretive to earnings upon completion. It brought 24 resorts and nearly 30,000 members into the fold.

Strategically, Accor did two things at once. First, it added another major global brand affiliation alongside Wyndham, Margaritaville, and Sports Illustrated. Second, it deepened Travel + Leisure Co.’s footprint in Asia Pacific: the company said the addition would lift its regional membership to more than 100,000 and increase its club resort count by about 40% to 77.

And importantly, this wasn’t “international” in name only. The resorts spanned Australia, New Zealand, and Indonesia under Accor brands like Peppers, MGallery, Grand Mercure, The Sebel, Novotel, Mantra, and Mercure—showpiece locations included Nusa Dua in Bali, Darling Harbour in Sydney, and Queenstown in New Zealand.

Financial Performance

By 2024, the numbers were reflecting what the strategy was supposed to deliver: steady demand, and a sales engine that could grow without needing a fundamentally different business model.

In the fourth quarter of 2024, Vacation Ownership revenue rose 5% to $813 million compared with the prior year period. Net vacation ownership interest sales increased 11% year over year, despite a higher provision rate. Gross VOI sales rose 10%, driven primarily by stronger performance per tour: VPG increased 7%, and tours grew 2%.

Capital returns stayed part of the story. The company paid a cash dividend of $34 million, or $0.50 per share, on December 31, 2024 to shareholders of record as of December 13. For the full year, dividends totaled $142 million.

Management pointed to strong adjusted EBITDA and VPG coming in at the top end—or above—initial guidance, attributing the results to consumers continuing to prioritize vacations. Looking to 2025, the company said it expected continued profitable growth in vacation ownership, which it described as the cornerstone of its investment strategy: growing earnings and free cash flow for shareholders. It guided to adjusted EBITDA of $955 million to $985 million for 2025.

The Strategic Direction

At this point, the company’s identity is less “we sell timeshares” and more “we run a scaled membership travel platform that happens to include vacation ownership.” Travel + Leisure Co. remained headquartered in Orlando, and it remained the largest vacation ownership company in the world by number of owners and resorts, with a network of more than 270 properties, around 25,000 units, and over 800,000 owners.

The strategic pillars were clear: broaden into a larger hospitality platform, focus on financially resilient customers as credit quality improved, diversify beyond North America, and keep using lifestyle brand partnerships to bring in new demand.

One key advantage in feeding the sales engine was its continued relationship with Wyndham Hotels through Wyndham Rewards. Hotel guests—already in a travel mindset—could be routed into tours, making the hotel network a valuable channel for generating new prospects for the vacation ownership business.

VII. The Timeshare Industry & Competitive Landscape

Industry Fundamentals

From the outside, vacation ownership can look like a relic in the age of Airbnb: commit now, vacation later, and keep paying every year in between. The basic deal is straightforward. A customer buys the right to use vacation accommodations on a recurring basis—often annually—for a long term, sometimes decades, and in some cases in perpetuity. In return, they pay an upfront purchase price (frequently financed) and ongoing maintenance fees.

What’s changed is the packaging. The industry began with fixed weeks at a specific resort—same place, same time, every year. Over time it shifted to points-based systems that trade rigidity for choice: different destinations, different seasons, different unit sizes. In its modern form, what gets sold can feel less like a deed and more like a membership with booking privileges.

And despite the stigma, the category hasn’t disappeared. As of August 2025, projections pointed to continued growth: an increase from $17.9 billion in 2024 to $19.35 billion in 2025, with expectations of reaching $26.14 billion by 2029. Whatever else you think about timeshares, that doesn’t look like an industry in retreat.

The reputation problem, though, is still real. High-pressure sales presentations, difficulty exiting ownership, and disappointing resale value stories create a steady drumbeat of negative word-of-mouth. Yet the model endures because it solves a specific problem for a specific kind of customer: people who reliably take vacations, want predictable accommodations, value exchange options, and believe they can come out ahead versus booking hotels year after year.

Competitive Positioning

Over the last decade, the industry has consolidated into a handful of giants, and the easiest way to understand who’s who is to follow the mergers.

Today, the landscape is dominated by three major players: Travel + Leisure Co. (often still thought of as “Wyndham” because of its history and brands), Hilton Grand Vacations, and Marriott Vacations Worldwide. That consolidation matters because many “independent” timeshare brands are, in reality, labels inside much larger corporate platforms.

Travel + Leisure Co. is the scale leader by footprint—owners, resorts, and the ecosystem around them. It has gone through multiple parent-company identities (Wyndham Worldwide, Wyndham Destinations, and now Travel + Leisure Co.), but the operating reality is continuity: a large vacation ownership base, a broad resort portfolio, and a critical strategic asset in RCI, one of the two primary exchange networks used across the category.

Hilton Grand Vacations has been the growth-by-acquisition story. It’s now the revenue leader, and it expanded dramatically through deals, including Diamond Resorts in 2021 and Bluegreen Vacations in 2024. In 2024, HGV generated $3.978 billion in revenue and net income of $313 million, and it reported more than 150 resorts and more than 525,000 club members.

Travel + Leisure Co. sits close behind on revenue. In 2023, it generated net income of $396 million on net revenue of $3.8 billion. Its portfolio has increasingly leaned into brand variety—Wyndham, Margaritaville, Sports Illustrated, and Accor Vacation Club—so it can sell “membership travel” through multiple front doors.

Marriott Vacations Worldwide is the third pillar. In 2024, it generated $3.53 billion in revenue and net income of $219 million, and it serves about 700,000 owner families. Its edge is obvious: it can tap into the loyalty ecosystems of Marriott International and Hyatt to feed demand and reinforce perceived quality.

Industry Challenges

Several structural headwinds keep this industry on a short leash.

First is perception. Even as products have evolved, the category is still associated with aggressive sales tactics and buyer’s remorse. And regulators continue to pay attention—exactly the kind of scrutiny reflected in the Pennsylvania and Wisconsin actions discussed earlier.

Second is demographics. Younger travelers tend to default to flexibility. They’re comfortable booking on-demand, switching destinations spontaneously, and avoiding long-term commitments. Converting millennials and Gen Z from “book whenever” to “own forever” remains one of the industry’s hardest problems.

Third is substitution. Hotels, short-term rentals, and the broader shift toward experiences all compete for the same travel dollar. When consumers have abundant, frictionless options, the industry has to work harder to justify why ownership—and the ongoing fee structure—still makes sense.

TNL's Differentiation

In that environment, Travel + Leisure Co.’s playbook leans on a few durable advantages.

Scale is the obvious one. With more than 800,000 owners and a global resort footprint, the company can spread marketing, technology, and operating costs across a massive base—and offer members a wider menu of destinations than smaller rivals can match.

Then there’s RCI, the network effect inside the machine. More properties in the exchange network means more options for members, which makes membership more valuable, improves satisfaction, and helps reduce churn.

Brand partnerships are the newer lever. Margaritaville, Sports Illustrated, and Accor let the company reach distinct customer segments without having to build everything from scratch. It’s a way to expand distribution and relevance while staying relatively capital-light.

Finally, there’s technology. Acquisitions like Alliance Reservations Network and ongoing digital platform work are meant to make booking and servicing feel closer to modern travel—while still preserving the high-touch sales and relationship model that, for better or worse, is what converts travelers into owners.

VIII. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

Corporate Transformation Playbook

If you step back from the brand names and the corporate paperwork, the Travel + Leisure Co. story reads like a playbook for how companies survive—and even profit from—massive disruption.

Surviving catastrophic scandal is the first, and most dramatic, lesson. The Cendant fraud erased roughly $14 billion in market value almost overnight. A lot of companies don’t come back from that. Cendant did. The turnaround wasn’t magic; it was triage and discipline: a rapid leadership reset, deep cooperation with regulators, and a willingness to sell assets to repair the balance sheet and stabilize the core.

Then there’s the power of strategic spin-offs as value creation. The unbundling from Cendant into separate companies—Realogy, Travelport, Wyndham Worldwide, and Avis Budget—wasn’t just cleanup. It was an intentional way to escape the conglomerate discount and let each business operate with the strategy, capital structure, and investor base that fit its economics. The pattern repeated later when Wyndham Worldwide split into Wyndham Hotels & Resorts and Wyndham Destinations. The throughline is focus: the more clearly the market can understand what you are, the more fairly it tends to price you.

Portfolio rationalization is the next lesson—and it’s harder than it sounds. Selling the vacation rental businesses for more than $1.4 billion in combined proceeds wasn’t a desperate move. It was a choice. Those assets could generate real revenue, but they didn’t fit the company’s long-term identity as an ownership-and-membership platform. Transformation often looks less like buying shiny new things and more like letting go of good businesses that distract from the best one.

Finally, rebranding can be a strategic weapon, not a cosmetic touch-up. The Travel + Leisure acquisition was a direct attempt to solve a perception problem: “Wyndham Destinations” reads like timeshare, and timeshare comes with baggage. Buying Travel + Leisure was a bet that a trusted consumer brand could open doors to new products and new customers—and potentially change how the whole company is understood. Whether it fully succeeds is still an open question, but the logic is hard to argue with: in consumer businesses, perception isn’t decoration. It’s distribution.

Timeshare Industry Insights

Timeshare, for all its stigma, is also a case study in recurring revenue economics.

Start with upfront sales, ongoing relationships. Hotels have to win the customer again every stay. Vacation ownership, once sold, creates a relationship that can last for decades. Maintenance fees, management fees, and exchange fees can keep flowing even when an owner doesn’t travel in a given year.

Then there’s financing as a profit center. When a customer finances a purchase through the developer, the company doesn’t just book a sale—it builds an interest-earning receivables stream that can last for years. That’s why credit quality matters so much. Targeting stronger FICO profiles and managing defaults isn’t a side job; it’s central to profitability.

And the real growth engine is often the base you already have. Owner upgrades are where lifetime value compounds. Travel + Leisure Co. has said that new owners spend an additional 2.6x their initial purchase through upgrades over time. In other words, the “sale” isn’t one moment—it’s a long relationship, and the best customers tend to keep buying.

Strategic M&A Lessons

The company’s dealmaking highlights a few patterns that show up again and again in successful transformations.

Buying brands vs. businesses is the clearest one. In the Travel + Leisure deal, the company didn’t buy a media operation and all its volatility. It bought the name, the club assets, and the licensing rights—while Meredith continued running the magazine under a long-term, royalty-free license. That’s a creative structure: capture brand equity without inheriting a business model you don’t actually want to operate.

Tuck-in acquisitions matter, too. Deals like Shell Vacations and Accor Vacation Club added scale and new customer pools without requiring a full reinvention of the company’s operating system.

And timing can be strategy. Divesting the vacation rentals business before the pandemic disruption meant the company exited at a favorable moment, freed up capital, and sharpened focus—right before travel demand went through its biggest stress test in modern history.

IX. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-LOW

Breaking into vacation ownership isn’t like spinning up an app and buying some Google ads. You need real capital to develop or acquire resorts, a trained sales organization to move inventory, and a compliance machine that can survive constant regulatory attention. Established players also benefit from long-standing brand relationships and distribution channels that newcomers can’t conjure overnight.

That said, the edges of the market are getting easier to enter. Asset-light models, plus a growing universe of alternative accommodations and subscription-style travel offerings, mean you can compete for the same vacation dollars without ever building a resort.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

The supplier set—developers, construction firms, and technology vendors—is fragmented, which keeps leverage on the buyer’s side. Scale matters here: a company as large as Travel + Leisure can negotiate pricing and terms in ways smaller operators can’t.

And as the industry leans more toward asset-light development—managing and marketing properties rather than owning them outright—supplier dependence drops even further.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM-HIGH

This is where timeshare gets weird, because the buyer’s power changes dramatically depending on when you measure it.

Before purchase, consumers have leverage. They can walk away, they have endless travel alternatives, and developers compete aggressively for their attention. But after purchase, the balance flips. Switching costs become enormous: owners have sunk money into the product, exiting is often difficult, and resale value can be limited. The result is a market where winning the customer is hard, but keeping them—at least financially—can be close to automatic.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

The list of substitutes is basically: the entire modern travel economy. Hotels, short-term rentals, vacation rentals, subscription travel clubs, and loyalty program redemptions all fight for the same spend. And as more travelers shift budget toward experiences, not just lodging, “owning” accommodations can feel less compelling.

When the consumer has more options than ever—and can book them in seconds—the timeshare value proposition has to work harder to stand out.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a concentrated, bruising category. Hilton Grand Vacations, Travel + Leisure Co., and Marriott Vacations Worldwide anchor the industry, and competition tends to revolve around three levers: brand, location portfolio, and points-based product design.

High fixed costs inside the model push companies toward aggressive sales behavior, and reputation becomes part of the battlefield as the entire industry tries to outrun its own stigma.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Travel + Leisure’s scale is real: more than 270 properties and more than 800,000 owners. That scale lowers per-unit costs across marketing, operations, and technology. It also expands choice for members, which is a key ingredient in making an ownership ecosystem feel valuable over time.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE-STRONG

RCI is the clearest network-effect asset in the portfolio. More affiliated resorts create more exchange options, which makes the network more valuable to members, which attracts more resorts. It’s a reinforcing loop that helps entrench the big exchange platforms.

But it’s not a perfect flywheel. Travel is seasonal, geography matters, and not all weeks and destinations are created equal—so the network effect is meaningful, but constrained.

3. Counter-Positioning: EMERGING

In theory, Travel + Leisure benefits from the fact that some potential competitors can’t comfortably copy the model. Traditional hotel companies often prefer asset-light franchising, and going hard into vacation ownership can create internal conflicts or brand complications. Online travel agencies can sell nights, but they can’t easily sell ownership.

The limitation is obvious, though: the biggest hotel brands already do this. Marriott and Hilton have successful timeshare divisions, which caps how much counter-positioning advantage Travel + Leisure can claim.

4. Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

This is the company’s strongest power, but it applies mainly after the sale. Once someone becomes an owner, switching is painful: sunk costs, limited resale options, and the psychological and administrative friction of unwinding the relationship. Those switching costs support steady recurring revenue.

They also fuel the industry’s reputation problem. What’s defensible for the company can feel like a trap to the customer.

5. Branding: MODERATE (IMPROVING)

Timeshare has an image problem, and Travel + Leisure Co. has been spending years trying to route around it. Buying the Travel + Leisure name was the most direct move possible: swap a label that screams “timeshare” for one that signals aspiration and credibility.

Sub-brands and partnerships like Margaritaville and Accor add appeal for specific segments, but branding here is still a work in progress—and it ultimately has to show up in customer acquisition, not just corporate messaging.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK-MODERATE

Prime resort locations are valuable and finite, but they’re not exclusive—competitors have great locations too. The Travel + Leisure brand is a differentiated asset, but how much it can truly change consumer behavior in vacation ownership remains to be proven over time.

RCI is also an important resource, but it operates in a competitive exchange landscape, notably against Interval International.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

This business runs on process. Tour generation, sales presentation optimization, consumer financing, and credit decisioning have been refined over decades into an operational discipline. That embedded know-how is valuable.

But it’s not unique. Other major players have developed similar machines, which limits how defensible this advantage is on its own.

Power Ranking: SWITCHING COSTS + SCALE are primary moats

Travel + Leisure is at its strongest with the customers it already has: switching costs create stability, and scale keeps the system efficient and expansive. The brand is improving, but it’s not a silver bullet. The soft underbelly is still customer acquisition—where substitutes are plentiful, consumer skepticism is real, and the company has to earn the sale one tour at a time.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case: The Membership Travel Platform Thesis

Structural Advantages:

At its core, Travel + Leisure Co. is built on recurring revenue and long customer lifetimes. Once someone becomes an owner, the relationship doesn’t end when the vacation does. Management fees, exchange fees, and the steady drumbeat of upgrades can extend for years—often decades.

There’s also a scale advantage baked into the model. With an installed base of more than 800,000 owners, the company has a level of stability that’s hard to replicate. Even when the economy gets choppy, maintenance fees still come in, because they’re tied to ownership, not to how optimistic consumers feel in a given quarter.

And the credit profile has been moving in the right direction. Management has emphasized improving portfolio credit quality by focusing on higher-income customers, which, in theory, makes the whole financing engine more resilient over time.

Growth Drivers:

The growth story is less about building a thousand new resorts and more about widening the platform.

The Accor Vacation Club acquisition is a good example. It expands the company’s reach in Asia Pacific and extends the membership base geographically, giving Travel + Leisure Co. more pathways to sell and service owners outside its traditional North American center of gravity.

Then there’s the brand strategy. Travel + Leisure licensing is designed to be capital-light: new products and partnerships that can generate fees and demand without the company needing to own every underlying asset.

The Sports Illustrated Resorts partnership is the same playbook, aimed at a different tribe. The pitch is straightforward: passionate sports fans are often willing to pay for immersive, themed experiences, and a recognizable brand can create pricing power if the product delivers.

Finally, there’s distribution. The connection to Wyndham Hotels through Wyndham Rewards gives Travel + Leisure Co. a built-in channel for tour generation. Hotel guests are already traveling, already spending on leisure, and can be routed into the top of the funnel more efficiently than cold leads.

Financial Position:

By 2024, the company was executing against the fundamentals that matter most in this model: tour flow and VPG performance. It was also returning capital through dividends and buybacks, signaling management’s confidence in the durability of the cash flows.

On the balance sheet side, the company’s leverage remained manageable, and its ability to finance and refinance timeshare receivables through securitization markets remained an important source of flexibility.

Bear Case: The Declining Industry Thesis

Secular Headwinds:

The hardest bear argument is the simplest: consumer preferences may be moving away from ownership.

Younger travelers tend to default to flexibility—Airbnb, hotel points, and spontaneous, mix-and-match trips. A multi-decade commitment can feel like an artifact from a different era. If that’s a structural shift, not a cyclical one, it’s a long-term headwind the industry can’t rebrand its way out of.

And that brings us to the second problem: stigma. Even with the Travel + Leisure name on the door, the underlying product is still vacation ownership. If consumer skepticism remains high, acquisition costs stay elevated, and conversion rates have a ceiling no matter how polished the pitch becomes.

Business Model Risks:

This is also a business with sharp edges. High-pressure sales tactics—real or perceived—create regulatory and reputational risk that never fully goes away.

Financially, the receivables portfolio is a strength until it isn’t. It concentrates credit exposure in consumer discretionary spending. In a downturn, you can get hit from both sides at once: higher defaults on existing loans and weaker demand for new sales.

And while the company has leaned into more capital-light approaches, parts of the model remain asset-heavy. Resorts still need renovations, refresh cycles don’t stop, and development and upkeep can become a treadmill of recurring capital spending.

Competitive Pressures:

Competition among the “Big Three” is not gentle. Hilton Grand Vacations has added scale and inventory through acquisitions like Diamond Resorts and Bluegreen. Marriott Vacations has a powerful advantage in brand ecosystem and loyalty.

If those rivals push harder on pricing, incentives, or marketing intensity, it can pressure margins across the category—especially in the battle for new customers, where switching costs don’t exist yet.

And then there’s the bigger competitive threat: substitutes. Alternative accommodations keep taking share of vacation spending, and shifting work patterns are changing how people travel. More frequent, shorter trips may favor hotels and rentals over products historically designed around longer, more predictable stays.

XI. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you want to keep score on whether Travel + Leisure Co.’s machine is getting stronger or starting to sputter, there are two metrics that tend to tell the story faster than almost anything else.

1. Volume Per Guest (VPG)

VPG is sales productivity in one number: the average gross vacation ownership interest sale per tour.

It matters because it compresses the whole sales engine into a single readout. Are they generating enough qualified tours? Are the presentations converting? Do they have enough pricing power to close bigger deals? When VPG rises, it usually means demand is healthy and the sales organization is executing. When it falls, it can point to softer demand, weaker close rates, or discounting that’s starting to bite.

Management gives VPG guidance and watches it closely. And when VPG holds above recent levels—north of $3,000—it’s a signal that, even with all the noise around timeshares as a category, the core model is still working.

2. Tour Mix (New Owner Tours vs. Owner Tours)

The second tell is what kind of tours they’re actually running: first-time buyers versus existing owners coming back for upgrades.

New owner tours are the lifeblood of long-term growth. They tell you whether the company is successfully bringing fresh customers into the ecosystem and expanding beyond the installed base.

Owner tours, on the other hand, are where efficiency lives. Upgrades tend to close at higher rates because the customer already knows the product. But that pool is ultimately limited—you can’t upgrade the same base forever without replenishing it.

The healthiest version of this business has both: a steady stream of new owners to keep the platform growing, and a strong upgrade engine to drive near-term performance. That’s why management has put so much emphasis on generating new owner tours, including through the Wyndham Hotels partnership. If new owner tour growth is strong, it’s one of the clearest signs the Travel + Leisure brand and the company’s partnership strategy are actually widening the top of the funnel.

XII. Final Thoughts: What Kind of Company Is This?

Travel + Leisure Co. sits in an unusual place: part hospitality operator, part consumer lender, part membership business. Its DNA was shaped by a corporate scandal that forced it to relearn trust the hard way. Its identity was refined through spin-offs that stripped away complexity and left a company with a sharper focus. And its most recent era—buying the Travel + Leisure name, leaning into partnerships, and expanding internationally—has been an attempt to change what people think they’re buying when they buy into the platform.

That leaves one clean, unavoidable question: is this simply a timeshare company with better branding, or has it actually become something broader?

The answer, right now, is messy. The core engine is still vacation ownership: sell the product, finance a lot of it, and then collect recurring fees from a long-lived owner base. That hasn’t changed. The Travel + Leisure brand, the Sports Illustrated partnership, and the Accor Vacation Club deal are real strategic extensions—but they haven’t yet overtaken the traditional business in terms of where the revenue and profits fundamentally come from.

What is hard to argue with is durability. Through financial shocks, reputational baggage, and the pandemic-era stress test, the machine has kept producing substantial cash flow, powered by an installed base of owners who are, by design, sticky. The same switching costs that make consumer advocates uneasy are also what make the revenue stream unusually reliable.

So the long-term investment debate comes down to growth. Can Travel + Leisure Co. keep bringing in new customers fast enough to offset demographic and perception headwinds? The brand strategy, partnerships, and geographic expansion are all bets on widening the funnel. Whether those bets compound—or stall—will decide if this is the endpoint of a transformation story… or the setup for its next chapter.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music