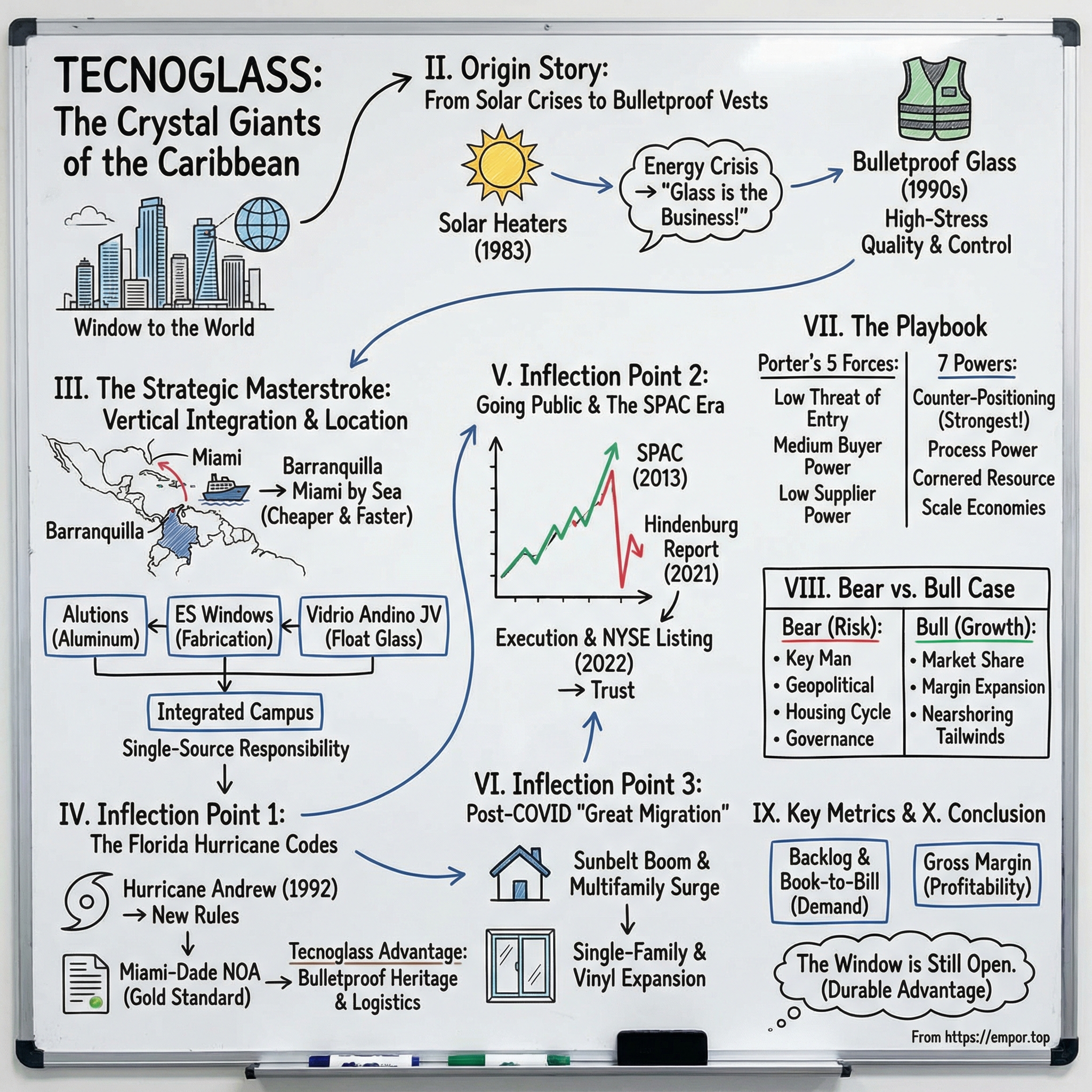

Tecnoglass: The Crystal Giants of the Caribbean

I. Introduction: The "Window to the World"

Stand on a rooftop in Miami’s Brickell district and look up. The Porsche Design Tower rises into the Florida sky, its glass skin catching the sun like polished metal. A few miles away, the Paramount Miami Worldcenter stretches across the skyline, wrapped in floor-to-ceiling curtain wall. Go all the way to San Francisco and the Salesforce Tower does the same trick on the other coast, reflecting the Pacific through thousands of precisely engineered panels.

These buildings share an unlikely common thread: much of that glass traces back to one place—a single, hyper-efficient manufacturing campus in Barranquilla, Colombia, a port city most Americans couldn’t pick out on a map.

That’s Tecnoglass. It’s the second-largest glass fabricator serving the U.S. and the leading architectural glass transformation company in Latin America. From Barranquilla, the company runs a vertically integrated, state-of-the-art operation that ships to more than 1,000 customers worldwide—with the U.S. generating more than 90% of its revenue.

How a Colombian, family-run business outmaneuvered global incumbents to become a dominant supplier for the American Sunbelt reads like a masterclass in strategy hiding in plain sight: pick the right geography, own the critical steps of production, and keep investing while others hesitate. This isn’t just a manufacturing story. It’s a nearshoring story—what happens when you move production closer to where demand lives, and then design the entire company around that advantage. It’s about how location can beat size, how sea lanes can beat highways, and how the unglamorous details of building codes can become a moat as real as any patent.

A few themes run through Tecnoglass’s decades-long climb. There’s the family-founder dynamic: two brothers who have led the company since the 1980s and still control it today through a dual-class structure. There’s the physics of logistics: the counterintuitive reality that shipping heavy, fragile glass by sea from Colombia to Miami can be cheaper—and faster—than hauling it by truck from Ohio or Pennsylvania. And there’s resilience: against hurricanes that hardened Florida’s building standards into some of the strictest on earth, and against years of Wall Street skepticism that wrote Tecnoglass off as an “orphan stock”—too foreign, too small, too obscure to matter.

José Manuel and Christian Daes have spent four decades turning that skepticism into fuel. By 2024, Tecnoglass delivered record full-year revenue of $890.2 million and built a backlog of $1.1 billion. More than a successful company, they built something rarer: a strategically placed industrial machine that can shape skylines a thousand miles away—Barranquilla’s own window to the world.

II. Origin Story: From Solar Crises to Bulletproof Vests

Tecnoglass didn’t start with skyscrapers, or even windows. It started with sunlight, an unstable power grid, and two brothers trying to build something practical for everyday Colombians.

On March 11, 1983, José Manuel Daes and Christian Daes launched Energía Solar ESWindows as a small, hands-on business making solar water heaters in Barranquilla. The pitch was simple: Colombia had plenty of sun, electricity was expensive, and households wanted reliable hot water. The brothers pulled together what capital they could, hired a team, and began turning out systems that were more craft than factory.

Then Colombia’s electricity system reminded everyone what “reliable” really meant.

In the early 1990s, the country depended heavily on hydroelectric power—often as much as 70–80% of total generation in normal years. That worked great until it didn’t. When El Niño brought drought conditions, reservoir levels fell, hydro output dropped, and the country slid into the 1992 energy crisis, stretching from May 2, 1992, to February 7, 1993, during the presidency of César Gaviria.

The government responded with rationing. Starting March 2, 1992, scheduled blackouts hit major cities—up to nine hours at a time in Bogotá, and up to 18 hours on the islands of San Andrés and Providencia. Then it got even more surreal: beginning Saturday, May 2, 1992, Gaviria moved the nation’s clocks forward from UTC-5 to UTC-4 in an attempt to squeeze more daylight out of the day. Colombians dubbed it “Hora Gaviria.”

For the Daes brothers, “Hora Gaviria” was jet fuel. When the grid became unpredictable, energy independence stopped being a nice-to-have. Solar heaters—once a convenience—suddenly felt like a necessity.

But the real breakthrough wasn’t that more people wanted heaters. It was what the brothers noticed inside the product. Solar heaters weren’t complicated. The high-value, hard-to-make component was the glass—especially tempered glass that could handle thermal stress while capturing heat efficiently. The heaters were the vehicle. The glass was the business.

They asked the question that marks the beginning of Tecnoglass: why are we in the heater business when we should be in the glass business?

On April 18, 1994, Tecnoglass S.A. began operations, built to produce tempered, laminated, and insulated glass, as well as screen-printed glass, bulletproof glazing, and curved glass—aimed at a market that wanted higher quality, competitive pricing, and dependable delivery.

It was the right move at the right time, in the wrong place—because Colombia in the 1990s was living through violence that demanded an entirely different kind of product discipline. Pablo Escobar had been killed in 1993, but the broader drug-war era continued. Kidnappings were common. Car bombs weren’t rare. And anyone with money or visibility—business owners, politicians, professionals—was suddenly shopping for protection.

That meant bulletproof glass. Not just for government armored vehicles, but for private cars, offices, and homes. And bulletproof glass doesn’t tolerate “pretty good.” If laminated glass fails, it doesn’t fail gracefully. It fails catastrophically.

So the Daes brothers learned manufacturing the hard way: under life-or-death quality requirements. They invested in precision equipment. They built rigorous quality control because their customers demanded it—and because the consequences of a defect were immediate and unforgiving. In the process, they developed deep expertise in lamination and high-performance glass that would later translate directly into a different extreme-stress use case: hurricane-resistant windows in Florida.

Bulletproof glazing taught them something else, too: control equals reliability. The more of the process they owned, the more they could guarantee performance. The more they could guarantee performance, the more their reputation compounded. And in markets where glass has to work under extreme conditions, reputation is everything.

By the late 1990s, Energía Solar had effectively transformed into Tecnoglass: a serious glass “transformation” company with capabilities that most Colombian manufacturers didn’t have. The brothers’ ambitions were growing—and so was their awareness that their home base had an unusual advantage.

Their factory sat in Barranquilla, a port city with direct access to the Caribbean. And across that water, roughly a thousand miles away, an American catastrophe had already rewritten the rules of construction—creating the kind of regulatory-driven demand that a quality-obsessed glass maker could turn into the opportunity of a lifetime.

III. The Strategic Masterstroke: Vertical Integration & Location

If you visit Barranquilla today, you might wonder why anyone would build a world-class manufacturing operation here. It’s hot, sprawling, and chaotic—Colombia’s fourth-largest city, without Bogotá’s polish or Cartagena’s tourist glow. But José Manuel and Christian Daes saw what most people miss: Barranquilla isn’t just a city. It’s a logistics weapon.

It sits at the mouth of the Magdalena River, Colombia’s main inland waterway, a natural conveyor belt linking the interior to the Caribbean. The port zone has multiple public-use terminals and handles a meaningful share of the region’s cargo. For a company that ships heavy, fragile product, being able to move by water—rather than by road—isn’t a detail. It’s the whole game.

Look at a map and the logic snaps into focus. Barranquilla is Colombia’s largest seaport on the Caribbean. It’s about 10 nautical miles upriver on the west bank of the Magdalena River, close enough to the open sea to move fast, far enough inland to connect to the country behind it. From there, a container ship can reach Miami in roughly three to four days. Compare that to a truck hauling glass from the American Midwest—fighting congestion, tolls, driver constraints, and weather—and you’re suddenly in the strange reality of modern logistics: ocean freight from Colombia can be competitive with domestic trucking inside the U.S.

But the Daes brothers didn’t just benefit from geography. They exploited the economics of empty space.

Because the U.S. runs a persistent trade deficit with Colombia, ships arrive in Colombian ports full and often head back with unused capacity. That empty space is a sunk cost for carriers, so return legs get priced aggressively. Tecnoglass positioned itself to buy that capacity. As the company has put it, this allows them to distribute to the eastern, southern, and western U.S. “at very attractive rates”—often lower than domestic land shipment within the United States. And because demand for high-spec architectural glass tends to concentrate in big coastal cities, Tecnoglass can ship directly into the places where the work is, while many competitors still rely on costly inland trucking to reach the same job sites.

That’s logistics arbitrage in its purest form: turn a trade imbalance into a durable advantage.

Still, location alone doesn’t make a moat. What turned that advantage into something hard to copy was the second strategic choice: build a campus that does almost everything in-house, and eliminate what the brothers call “margin stacking” by middlemen.

The story starts in 1994, when Tecnoglass S.A. launched to temper and laminate glass. But architectural glass doesn’t ship as glass. It ships as systems—glass, frames, hardware, finishes, and assembly. If you’re buying key components from third parties, every handoff adds lead time, markup, and another opportunity for something to go wrong.

So in 2007, Tecnoglass made a crucial move: it founded Alutions, its aluminum extrusion business. Instead of purchasing aluminum profiles from suppliers—paying their margins, waiting on their schedules, and managing their quality—the company brought extrusion onto the Barranquilla campus. Raw aluminum billets come in. Finished profiles come out. The windows and curtain wall systems get built right there. Fewer dependencies. Less finger-pointing. More control.

Over time, the campus became the company’s signature. With Tecnoglass, ES Windows, and Alutions operating as one integrated machine, the company could offer single-source responsibility: one manufacturer accountable for the full product, not a chain of vendors passing the risk down the line. The footprint expanded dramatically as demand grew; today the operation spans several million square feet and is designed to move materials through the process with factory-like rhythm.

Then, in 2019, Tecnoglass went after the last major piece it didn’t fully control: float glass.

Float glass is the base input for almost everything that comes later—large, flat sheets created by floating molten glass over molten tin. It’s capital-intensive, and it’s typically produced by global giants. Tecnoglass announced a joint venture agreement with Saint-Gobain through a planned purchase of a minority ownership interest in Vidrio Andino, Saint-Gobain’s Colombia-based subsidiary with annualized sales of about $100 million. The planned facility would have nominal production capacity of approximately 750 metric tons per day of float glass. Tecnoglass’s investment for the minority interest was approximately $45 million, expected to be funded with about $34 million in cash plus land contributed at an aggregate value of approximately $11 million.

The strategic point wasn’t the deal structure. It was what it represented: pushing vertical integration further upstream to help secure long-term float glass supply and improve purchasing economics over time.

By this stage, what began as a solar heater company had been rebuilt into an industrial platform. Materials arrive in Barranquilla. Glass gets fabricated, laminated, insulated, and assembled into finished architectural systems. Those finished systems leave the same campus and go straight onto vessels bound for American ports.

And the benefits compound. Quality control gets easier when you own the chain. Lead times tighten when you don’t wait on suppliers. Costs drop when you strip out intermediaries. And the moat deepens because a competitor can’t copy this by buying one machine—they’d have to replicate an entire ecosystem, in the right place, designed as one continuous flow.

Tecnoglass didn’t just build a factory. It built a machine tuned to a very specific market.

And that machine was about to collide with a regulatory shockwave in the United States—one that would turn extreme performance glass from a niche product into a requirement.

IV. Inflection Point 1: The Florida Hurricane Codes

At around 5:00 a.m. on August 24, 1992, Hurricane Andrew slammed into Homestead, Florida. It was a Category 5 storm, with winds in the neighborhood of 165 to 175 miles per hour, and it didn’t just damage South Florida—it erased it. Roughly 63,000 homes were destroyed and another 100,000 were damaged.

But the most important wreckage wasn’t physical. It was reputational.

When investigators combed through what was left, they found a second disaster hiding inside the first: a lot of buildings hadn’t failed because Andrew was unstoppable. They failed because they were badly built. In places like Country Walk—one of the most infamous examples—homes came apart in part because of corner-cutting so basic it sounded like a joke: staples used where nails should’ve been, low-grade plywood where stronger materials were required.

Florida’s political establishment took it personally. The state that sold itself as paradise had allowed developers to build structures that couldn’t protect families when it mattered. The insurance industry, staring at roughly $26 billion in losses in 1992 dollars, demanded reform. So did residents. And almost overnight, the rules of construction in Florida changed.

In the wake of Andrew, Florida tightened its building codes dramatically. In South Florida, the first major post-Andrew update arrived in 1994 with the South Florida Building Code. It strengthened roofing standards and, crucially, pushed the market toward impact-resistant windows and hurricane shutters in new construction.

That shift created an entire new product category: impact-resistant fenestration—windows and doors that had to do more than resist wind. They had to take a hit from flying debris and still hold. Because in a hurricane, a broken window isn’t “just” a broken window. Once the building envelope is breached, wind rushes in, pressure changes, and the forces on the structure can escalate fast enough to cause catastrophic failure.

Then came the certification regime that turned these rules into a moat.

In the High Velocity Hurricane Zone—Miami-Dade and Broward counties—products need a Miami-Dade Notice of Acceptance, or NOA. To get it, manufacturers have to prove their systems can handle punishing wind pressure, repeated impacts, and real-world installation demands. It isn’t a box-checking exercise. It’s lab testing, documentation, audits, and ongoing compliance.

The Miami-Dade NOA became the gold standard—widely viewed as the toughest building product certification anywhere. And it did two things at once: it made entry expensive and slow, and it made certified products mandatory. If you were building in South Florida, you didn’t get to “opt out.” You bought NOA-approved systems.

U.S. manufacturers scrambled. Many struggled. Laminated glass—multiple layers bonded with polymer interlayers so the glass can crack without failing—isn’t exotic in theory. But scaling it efficiently, at consistent quality, and at Florida’s volumes was another matter.

Tecnoglass saw the opening immediately.

Throughout the 1990s, the company had been refining laminated-glass manufacturing for bulletproof applications in Colombia. The overlap with hurricane resistance was almost uncanny: extreme stress, tight tolerances, unforgiving quality standards, and high consequences when things go wrong.

Tecnoglass didn’t just meet Miami-Dade. It leaned into it. The bulletproof heritage had built a culture where “good enough” wasn’t an option, and that mentality translated cleanly into hurricane-rated systems. Then the company layered on its other advantage: logistics. While many U.S. competitors were hauling finished windows down to Florida by truck, Tecnoglass could ship directly from Barranquilla into Miami by sea—often faster, often cheaper, and at scale.

And the codes did what they were designed to do. Studies found that homes built in Florida after the 1994 changes suffered significantly less damage to roofs and wall coverings than older construction. The regulations worked—and as Florida’s population surged and cranes filled the skyline, demand for impact-resistant glass rose right alongside it.

By the late 2000s, Tecnoglass had become a go-to supplier for South Florida’s high-rise residential boom. Its systems ended up in projects like One Thousand Museum and Paramount in Miami, and the company’s reach extended far beyond Florida into signature towers like the Salesforce Tower in San Francisco.

If you bought a condo in Miami between 2010 and 2020, there’s a very good chance you’re looking through Tecnoglass.

They had found the perfect market: sophisticated developers building premium properties in a geography that effectively required Tecnoglass’s kind of product—served from a vertically integrated campus that could ship straight into Florida’s ports.

The missing ingredient was scale capital—and a way to tell this story to U.S. investors who could fund the next chapter.

V. Inflection Point 2: Going Public & The SPAC Era

By 2013, Tecnoglass had run into the classic ceiling of a successful private manufacturer. The Daes brothers had built a machine that could win in Florida and beyond—but scaling it meant pouring money into new capacity, new technology, and broader commercial reach. Bank debt could only take them so far. Real expansion required equity. The problem was that a traditional IPO would be slow, expensive, and distracting. And for a Colombian company trying to convince U.S. investors—many of whom couldn’t place Barranquilla on a map—that path looked even steeper.

So they chose a back door that, at the time, wasn’t famous at all: a SPAC.

This was 2013, long before SPACs became a punchline and a frenzy. Back then, they were mostly a niche tool: a publicly traded shell company with cash, created for the sole purpose of merging with a private business and taking it public in the process.

Tecnoglass’s SPAC was Andina Acquisition Corporation. Andina had been incorporated in the Cayman Islands on September 21, 2011 as a blank check company, and it completed its IPO in March 2012. Then, in December 2013, the deal closed. Tecnoglass, Inc. was the surviving public company, and it was set to begin trading on the NASDAQ Capital Market on December 23, 2013 under the symbol TGLS (with warrants as TGLSW).

The transaction gave the company capital and a U.S. listing while keeping what the brothers cared about most: control. Based on Andina’s market price of $10.14 per share on October 31, 2013, Tecnoglass Holding shareholders received approximately $208.5 million in total merger consideration at closing and owned about 79.7% of Andina’s ordinary shares after the merger.

And the governance structure made the control explicit. Public investors received Class A shares with one vote per share. The founders held Class B shares with ten votes per share. Even without owning a majority of the equity, the Daes family could keep steering the ship.

But the public markets didn’t greet Tecnoglass like a growth story. They treated it like a question mark.

On NASDAQ, Tecnoglass became what investors call an “orphan stock”: a small-cap manufacturer based in an emerging market, lightly covered by analysts, thinly traded, and automatically discounted by institutions trained to avoid anything that feels complicated. That skepticism had fuel. Around the time it went public, Tecnoglass cycled through three auditors in roughly a year, and auditors flagged material weaknesses tied to the identification and reconciliation of related-party transactions.

For years, the stock price stayed stubbornly muted, even as the business executed. Tecnoglass was building towers in America, but in the market it still felt like a faraway name with too many footnotes.

Then, in December 2021, that fragility snapped into a full-blown crisis.

Hindenburg Research published a short report alleging “serious red flags” at Tecnoglass, citing a months-long investigation that, in its words, included reviews of U.S. and Colombian court records, securities filings, corporate registrations, property records, export records, and decades of media reporting. The report raised questions about undisclosed related-party transactions and past legal matters involving company leadership.

The market reaction was immediate and brutal. Tecnoglass shares fell more than 40%, dropping from $31.77 to $18.67. Nearly $1 billion of market value evaporated in a day.

Tecnoglass didn’t respond by trading punches on social media. Instead, it set up a Special Committee to examine three things: whether certain related-party transactions had not been properly disclosed, what controls existed around related-party transactions, and the truth of allegations in the report regarding past law enforcement activity involving certain officers. The company said the committee did not identify evidence of fraud associated with the related-party transactions referenced in the report, and that it did not expect the findings would have an adverse effect on its consolidated financial statements, results of operations, or liquidity.

From the outside, the strategy was simple: heads down, execution up. Keep investing. Keep shipping. Keep posting results.

That approach worked over time. Almost three and a half years later, Tecnoglass was trading around $58 on the New York Stock Exchange—roughly three times where it was after the Hindenburg report—and in November 2023, Forbes named it the number 1 U.S. small-cap company.

The turning point in the company’s public-market rehabilitation came in 2022, when Tecnoglass transferred its listing from NASDAQ to the NYSE. The company said it expected to begin trading on May 9, 2022, keeping the same symbol: TGLS. José Manuel Daes called it a “significant milestone,” pointing to the NYSE’s visibility, liquidity, and reach with investors.

Tecnoglass also noted it had become the first Colombian-founded company to be directly listed on the NYSE. And in practical terms, the move mattered. The NYSE listing helped change the company’s optics: more institutional attention, more analyst coverage, and a narrative shift from “orphan stock” toward “credible industrial compounder.”

The short-seller noise didn’t disappear. By late 2024, Culper Research raised similar allegations about leadership. Tecnoglass sued Culper and its founder, accusing them of trying to destroy shareholder value, and said it had provided Culper with a Mexican court decision indicating memos linking the company to a drug cartel were not authentic. The company stated: “Tecnoglass, José Daes, and Christian Daes are not, and never have been, connected to or involved in any way with, the Sinaloa cartel or its operations.”

These episodes didn’t become footnotes. They became part of the risk profile: governance scrutiny, reputational volatility, and the reality that a foreign-controlled public company can be an easy target when the story gets complicated.

But by the time the dust settled, something important had changed. Tecnoglass had proven that it could keep performing through public-market turbulence—and that durability, more than any press release, is what finally began to earn investor trust.

VI. Inflection Point 3: The Post-COVID "Great Migration"

The COVID-19 pandemic didn’t just disrupt supply chains. It reshuffled the American population map.

Suddenly, millions of white-collar workers weren’t tethered to Manhattan or San Francisco. High-tax, high-cost states like New York and California saw net outmigration. Florida—no state income tax, year-round sun, and a lifestyle brand all its own—became the headline destination of the Great Migration.

For Tecnoglass, it was demand gasoline.

New residents needed places to live. Developers responded the only way they could: build fast. Multifamily projects surged. Office space followed as companies planted flags across the Sunbelt. And in Florida, virtually all of that new construction required exactly what Tecnoglass was built to make: impact-resistant, hurricane-code-compliant glass and window systems, delivered in volume.

At the same time, the pandemic stress-tested global manufacturing. Companies that relied on Asian suppliers found themselves stuck in logistics purgatory—delays stretching from weeks into months, and container pricing that swung wildly. “Just in time” became “not in time,” and on a construction site, late product isn’t a nuisance. It’s a schedule-killer.

This was the flip side of Tecnoglass’s vertical integration bet. With raw materials flowing into Barranquilla and finished systems shipping straight out to U.S. ports, Tecnoglass could keep producing while competitors waited on missing components. Reliability—always valuable in construction—became a differentiator developers would pay for.

Even with meaningful exposure to Colombian peso swings and real costs from aluminum tariffs, the company still managed to grow and expand margins during the period, a signal that the model wasn’t just efficient in calm waters. It could handle rough seas, too.

Then Tecnoglass made its next leap: take what it learned winning high-rises and push into the biggest window market of all—single-family homes.

It broadened its offering with Multimax, a product line aimed at large-scale homebuilders. And it backed that push with a more retail-like strategy than you’d expect from a curtain-wall manufacturer: opening showrooms in high-growth markets to get closer to builders, contractors, and homeowners.

The results showed up quickly. In the third quarter of 2022, revenue rose sharply versus the prior year, driven by strength in commercial, rapid growth in single-family residential, and continued market share gains. Single-family residential became a much larger piece of the mix—no longer a side project, but a second engine.

The next move was even more consequential: vinyl.

Vinyl windows dominate single-family residential construction across much of the United States. They’re typically cheaper than aluminum and offer strong thermal insulation. But Tecnoglass had historically been an aluminum-systems company, built around commercial and high-rise applications. Going after vinyl meant new manufacturing capabilities, new go-to-market motions, and new relationships—homebuilders instead of tower developers.

Tecnoglass invested to build that capability, launched its vinyl product line, and positioned it as a market-doubling expansion in the U.S. opportunity set.

To support the push, the company continued expanding its showroom footprint. Locations in New York, South Carolina, Texas, and Arizona were already operating, with another planned for California in the fourth quarter of 2025. The strategy was straightforward: keep widening the funnel beyond Florida, and make it easier for single-family customers to buy Tecnoglass.

That geographic expansion became the next frontier. CEO José Manuel Daes pointed to new penetration not only across Florida—Tampa, Jacksonville, and the Panhandle—but also into markets like Boston, New York, Texas, California, Hawaii, and other coastal regions.

Financially, the story kept compounding. In 2023, Tecnoglass posted record revenue of $833.3 million, achieved through entirely organic growth, alongside record adjusted EBITDA of $304.1 million. In 2024, revenue grew again to a new record of $890.2 million, fueled by the same playbook: expand geographically, broaden the product line, and keep the Barranquilla machine running at higher utilization.

And perhaps the clearest marker of momentum was the backlog. Tecnoglass reported a record backlog of $1.3 billion, up year-over-year. In this business, backlog isn’t just a nice-to-have. Architectural glass gets specified early, bid early, and locked in months—sometimes years—before installation. A backlog like that is unusual visibility: committed demand already sitting on the books, waiting to be manufactured, shipped, and installed.

VII. The Playbook: Power Analysis

To see whether Tecnoglass can keep its edge, it helps to look at the business through two lenses investors love: Michael Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers. One asks, “How hard is this game?” The other asks, “What makes this player hard to beat?”

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Copying Tecnoglass isn’t a “buy some machines and hire a team” project. A real challenger would have to build a multi-million-square-foot manufacturing campus, earn Miami-Dade NOA approvals (years of testing, documentation, and compliance), lock in ocean logistics and port relationships, and win trust with developers who only care about one thing on a job site: who delivers, on time, every time.

And even if someone wanted to do all of that, they’d be trying to catch a company with roughly four decades of compounding know-how. The learning curve is part of the moat.

You can see the price tag in Tecnoglass’s own plans. Management announced a roughly $350–$400 million expansion plan to replicate elements of the model in the U.S. If the incumbent needs hundreds of millions to build a “second platform,” a new entrant would be signing up for an even harder version of that same bill—with far less certainty of success.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

Yes, developers negotiate hard. Construction is competitive, and budgets are tight.

But windows and curtain wall aren’t like paint or carpet. If the glass package shows up late, the entire project can slip—sometimes by weeks. That can mean delayed occupancy, delayed revenue, and painful carrying costs. In that world, “cheap” is only cheap until it breaks the schedule.

Tecnoglass earns pricing power not by being the lowest bidder, but by being the supplier developers trust to hit deadlines. That reliability creates real switching costs, even when buyers would love to treat the product like a commodity.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

Vertical integration is the quiet assassin of supplier power. Tecnoglass extrudes its own aluminum, transforms its own glass, and holds a joint venture interest tied to its float-glass supply. What’s left—aluminum billets, energy, labor—are largely commodity inputs where no single vendor can hold the company hostage.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW

High-rises and modern multifamily buildings don’t have a substitute for architectural glass. If anything, energy codes and design trends keep pushing in the opposite direction: bigger openings, more glazing, higher-performance units. Demand tends to shift toward “better glass,” not “less glass.”

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

Tecnoglass competes with large players and specialists. Apogee Enterprises is one of the better-known U.S. names in the space, and other competitors include Cardinal Glass & Door and Oldcastle Glass Group.

But Tecnoglass’s position is distinct: a cost-advantaged, Florida-hardened producer that can meet strict hurricane standards at scale—then ship efficiently into the U.S. from the Caribbean. The company has highlighted how that mix shows up in profitability: Tecnoglass reported gross margins in the mid-40% range, versus materially lower levels at some major peers.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Analysis:

Counter-Positioning (THE STRONGEST POWER)

This is the heart of the story. Tecnoglass built a cost structure and operating model that many U.S. incumbents can’t match—not because they lack talent, but because responding would force them to blow up their existing model.

A legacy competitor with established U.S. plants can’t easily “just move to Colombia.” The optics of offshoring jobs would be brutal. The sunk costs in domestic facilities create inertia. And the organizational muscle to manage a large Colombian manufacturing base from a U.S. corporate structure often isn’t there.

That’s counter-positioning: the attacker enters with a different model, and the incumbent can’t copy it without punishing itself.

Process Power

The Barranquilla campus isn’t just big. It’s trained.

Raw inputs go in; finished window and façade systems come out. The layout has been tuned for flow over years of iteration. Quality systems have been refined through enormous production volume. And the human element matters: operators, supervisors, and engineers who’ve spent careers learning what works, what fails, and how to keep the line running.

A competitor can buy equipment. They can’t buy the muscle memory of a factory.

Cornered Resource

Barranquilla itself functions like a cornered resource. There simply aren’t many places that combine port access, the right labor base, available industrial land, and proximity to U.S. demand—especially for a product that’s heavy, fragile, and expensive to move.

Tecnoglass didn’t just pick the spot. It committed early, built deep relationships, and secured the footprint. Even a motivated rival would need years to replicate the same practical advantages.

Scale Economies

Scale is the flywheel. Over the last five years, Tecnoglass grew sales at a 21.2% compounded annual growth rate. As volume rises, fixed costs get spread across more units, utilization improves, and purchasing leverage increases. In manufacturing, that’s how good becomes great: the bigger machine gets cheaper to run per unit, which makes it easier to win more volume, which makes the machine even better.

VIII. Bear vs. Bull Case

Every great business story has two versions running in parallel. One is the compounding machine you can’t unsee once you understand it. The other is the list of things that can break the machine.

The Bear Case:

Key Man Risk

José Manuel and Christian Daes have run Tecnoglass for four decades. They aren’t just executives; they’re the operating system. The founders retain approximately 34% ownership and a significant portion of the company’s shares, which keeps incentives aligned—but also concentrates risk. Succession planning, or any lack of it, matters here. What happens to the culture, the relationships, and the day-to-day execution when the brothers step back?

Geopolitical Risk

Tecnoglass’s advantage is partly geographic, and geography comes with politics. Colombia’s political landscape has shifted leftward in recent years. Changes to tax policy, labor regulations, or the broader business environment could compress margins or erode cost advantages over time. The company has navigated Colombian politics for decades, but stability is never guaranteed.

Housing Cycle Exposure

Construction is cyclical, and glass is downstream of the cycle. Interest rates rise, projects get delayed. Credit tightens, starts slow. And because Tecnoglass generates about 95% of its revenue from the U.S., it’s highly exposed to American demand. A sharp housing or commercial construction downturn would hit volumes quickly, no matter how good the Barranquilla machine is.

Governance Concerns

Tecnoglass’s dual-class structure concentrates control with the founders. Related-party transactions have drawn scrutiny, and the company has been the subject of multiple short reports questioning management and disclosure practices. Tecnoglass has pushed back, and no fraud has been substantiated—but the setup creates recurring headline risk. Add in the report’s emphasis on insider selling—more than $345 million in stock sales by the CEO and COO over the past nine months, described as their largest selloff on record—and you have a stock that can reprice on narrative as much as on fundamentals.

The Bull Case:

Market Share Expansion

Here’s the simplest bullish argument: Tecnoglass is still early in the biggest market. It has strong share in Florida’s impact-resistant commercial glass world, but remains underpenetrated in most other states and in large segments of U.S. residential. Expanding into single-family, launching vinyl, and pushing deeper into Texas, California, and the Northeast creates a long runway if the company can replicate its Florida playbook.

Margin Expansion Potential

The mix shift matters. Single-family products tend to be less bespoke than large commercial projects, which can improve manufacturing efficiency and support stronger margins over time. And if the vinyl line ramps the way management expects, it should become a positive contributor to the overall margin profile.

Nearshoring Tailwinds

Tecnoglass is almost a pure play on nearshoring: manufacturing in the Americas for American customers, with ocean lanes doing the heavy lifting. If de-globalization and supply chain localization continue, that positioning becomes more valuable, not less. And management has framed growth as something they can drive through volume, not just pricing. CFO Santiago Giraldo pointed to expectations for double-digit growth in 2026, saying, “So when we’re talking about double-digit growth, it’s more coming from volume rather than the assumption that we’re gonna be able to raise prices again.”

IX. Key Metrics to Watch

If you want to keep tabs on whether Tecnoglass’s machine is still compounding, you can get most of the signal from two numbers: what’s coming in, and what they keep.

1. Backlog and Book-to-Bill Ratio

Backlog is the company’s forward-looking scoreboard. It’s work already won—projects specified, sold, and waiting to be produced and shipped. The book-to-bill ratio tells you whether that pipeline is filling faster than it’s being converted into revenue. Above 1.0x means orders are outpacing fulfillment, which is usually what you want to see in a growing manufacturer.

Tecnoglass’s record $1.3 billion backlog, paired with a book-to-bill of 1.3x, points to demand staying ahead of output. The key is the trend: watch how backlog moves quarter to quarter, because it often tells you where revenue is headed before the income statement does.

2. Gross Margin

Gross margin is the clearest snapshot of how well the model is holding up. It captures pricing discipline, factory efficiency, and the invisible tug-of-war between costs and mix.

Management has said it expects gross margins to stay in the low- to mid-40% range for 2026, with the usual swing factors: raw material costs, foreign exchange, and what proportion of sales comes from higher-spec commercial work versus more standardized residential products. If margins compress meaningfully, it’s a warning sign—either costs are rising faster than pricing, competition is getting sharper, or the mix is shifting down-market. If margins expand, it’s validation that the vertical integration and process advantages are still doing their job.

Together, these two metrics tell the whole story: backlog shows you demand; gross margin shows you whether Tecnoglass is converting that demand into durable profits.

X. Conclusion: The Window to the World

In Barranquilla, not far from Tecnoglass’s sprawling manufacturing campus, the company built a monument locals call La Ventana de Sueños—the Window of Dreams. It was inaugurated in Puerto Colombia as a new lighthouse, meant to guide vessels and, just as importantly, to become a place families visit.

The symbolism lands because the strategy did, too. Four decades ago, two brothers in a Colombian port city looked out across the Caribbean and saw an edge hiding in plain sight. They bet that location could beat scale, that owning the chain could beat buying it, and that the harshest standards—whether born from violence at home or hurricanes in Florida—could be turned into advantage if you built quality like your life depended on it.

They built a window to the world. And through that window, they’ve shipped the kind of glass that doesn’t just fill buildings—it defines them.

This story isn’t risk-free. Governance questions have created real headline volatility. Construction cycles are unforgiving. The founders won’t run the company forever. And the demand for architectural glass will always be tied to forces no management team controls: interest rates, migration, and yes, the next storm season.

But the core case for Tecnoglass is simple and unusually durable. The advantages are structural, not fashionable. The moat is enforced by certifications that take years to earn. The factory is a machine designed around throughput and control. And the growth playbook is still expanding—beyond Florida, deeper into the Sunbelt and coastal markets, and from high-rise commercial into the massive single-family world, with new product lines broadening what the company can sell.

The crystal giants of the Caribbean have made a habit of proving skeptics wrong. Whether they can keep doing it will come down to execution, succession, and the macro tides they can’t command.

But as a pure expression of nearshoring, Sunbelt construction demand, and a manufacturing model that actually seems to get stronger under stress, Tecnoglass remains one of the more distinctive stories in industrial America—built, improbably, just offshore.

The window is still open.

Sources

This story is based on a mix of primary and secondary materials, including Tecnoglass filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, investor presentations, earnings call transcripts, and company press releases. It also draws from reporting in major financial publications and independent research coverage, including NAHB materials on Florida building codes, court documents tied to the Andina SPAC merger, and financial data compiled across multiple market data services.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music