Tenable Holdings: The Story of Vulnerability Management's Pioneer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

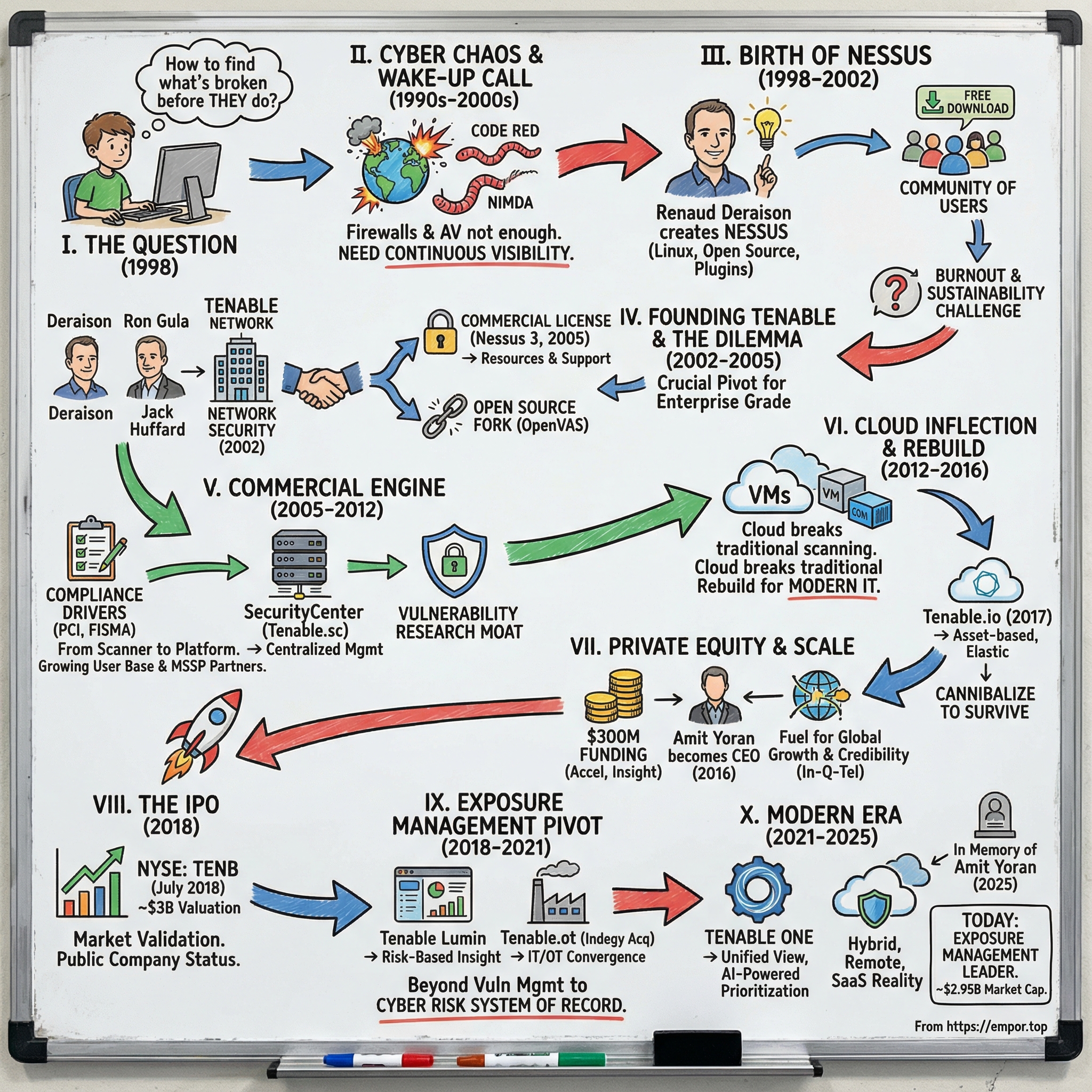

Picture a nineteen-year-old computer science student in Paris in 1998, lit by the glow of a monitor at some ungodly hour. The internet is young, chaotic, and wildly insecure. Renaud Deraison isn’t trying to build a company. He’s trying to answer a question that feels urgent in his bones: how do you find what’s broken in your network before someone else does?

In his spare time, he starts building a vulnerability scanner called Nessus. That scrappy project will go on to become one of the most widely deployed security assessment tools in the world, help define an entire category of enterprise software, and eventually grow into Tenable: a public cybersecurity company worth billions.

This is the story of Tenable Holdings, the company that helped turn “vulnerability management” from a niche practice into a standard operating procedure. As of December 2025, Tenable has a market capitalization of roughly $2.95 billion, with trailing twelve-month revenue near $975 million. The company was founded in 2002 by John C. Huffard Jr. and Renaud M. Deraison and is headquartered in Columbia, Maryland.

What makes Tenable fascinating isn’t just the destination. It’s the path. This wasn’t a classic Silicon Valley rocket ship funded from day one. It started as an open-source tool that became so useful, so trusted, and so embedded inside real organizations that it essentially dragged the market into existence behind it. The journey from “free download” to “public company” is a masterclass in category creation, commercialization timing, and knowing when you have to reinvent yourself before the world forces you to.

Today, Tenable sells what it calls exposure management: a unified way to see and reduce risk across a messy reality of IT, cloud, and converged OT/IoT environments. Its Tenable One platform aims to give enterprises a single view of risk across assets and attack pathways, with AI-powered prioritization layered on top.

And the questions Tenable had to answer along the way are the same ones every security founder eventually runs into. How do you turn open source into a business without alienating the community that made you matter? When do you cannibalize your own hit product before a competitor does it for you? And how do you sell something that actually improves security in a world that too often buys tools for compliance checkboxes?

To understand how Tenable got here, we have to go back to the moment the internet started breaking in spectacular, headline-grabbing fashion.

II. The Cybersecurity Context & Market Genesis (1990s–Early 2000s)

The late 1990s were a weird, fragile moment in computing. The internet was exploding—by 1999, roughly 280 million people were online worldwide—but the way we “secured” networks was almost comically simplistic. Most companies had two lines of defense: firewalls and antivirus.

Firewalls were the bouncers at the door, focused on keeping the bad guys out. Antivirus was the mugshot book, looking for known signatures of known malware. And both had the same fatal assumption baked in: you already knew what you were defending against.

But attackers weren’t playing by that rule anymore. They were finding new holes faster than organizations could even learn the names of the old ones. The difference between “a patch exists” and “you are safe” was about to become painfully clear.

The wake-up call came in the summer of 2001. Code Red, a worm first observed on July 15, tore through Microsoft IIS web servers. By July 19, infections hit about 359,000 hosts in a single day, and the damage tally reached at least $2.6 billion globally. What made security teams sick to their stomach wasn’t just the scale—it was the cause. Code Red exploited a vulnerability described in Microsoft Security Bulletin MS01-033, and a patch had been available for a month.

Thirty days of warning. A free fix. And still, the internet burned.

Then, on September 18, 2001, Nimda showed up and raised the stakes again. It spread by exploiting multiple vulnerabilities in Microsoft Windows and by taking advantage of backdoors left open by earlier worms like Code Red II and Sadmind. Reports at the time said Nimda became the internet’s most widespread virus/worm within 22 minutes. Twenty-two minutes.

Nimda was especially terrifying because it wasn’t a one-trick pony. It used five different infection vectors—less like a single exploit and more like a swarm—making it brutally effective against organizations that didn’t even know where to start looking.

And that was the core failure of the era: the gap between knowing a vulnerability existed somewhere in the world and knowing whether it existed on your network. Once patches started arriving for critical issues, attackers learned to treat them like roadmaps. The moment an update was released, cybercriminals would study what it fixed and race to exploit the same weakness in environments that hadn’t caught up yet.

In theory, the response was simple: patch faster. In practice, companies didn’t even have a reliable way to answer the first question: What do we have, and what’s vulnerable?

The tools available didn’t make that easy. There were commercial scanners—ISS (later acquired by IBM), early SAINT, SARA—but they were often expensive, limited, and demanding to operate. Meanwhile, government and military organizations had been investing in vulnerability assessment for years, driven by classified programs and the growing belief that cyberwarfare was real. But for the average enterprise, vulnerability work was still a sporadic ritual: run a scan sometimes, produce a report, hope nothing catastrophic happened in between.

Code Red and Nimda forced a mindset shift. Security couldn’t just be reactive. It couldn’t be occasional. You needed a way to continuously find weaknesses—before attackers did.

Vulnerability management wasn’t a crisp category yet. But the need for it was suddenly undeniable. And it was into this world—panicked, under-tooled, and finally paying attention—that a young French programmer was about to drop a tool that would democratize scanning and change everything.

III. Renaud Deraison & The Birth of Nessus (1998–2002)

In 1998, Renaud Deraison was a teenage computer science student in France with a very specific obsession: network security. While most of his peers were learning the basics, Deraison was spending his nights asking a more unsettling question: if I were the attacker, where would I get in?

The late-’90s hacker and security scene had its own ethos. Finding flaws mattered. Sharing them—often loudly, publicly—was treated as a kind of civic duty. And the center of gravity for that world wasn’t a conference stage or a company blog. It was mailing lists.

On April 4, 1998, Deraison posted to Bugtraq, the security mailing list everyone read. The message was simple: he’d been working for about a year on a Linux application with a graphical interface that could check a network for more than 50 vulnerabilities. He called it Nessus.

That email lit the fuse.

Deraison would later say he launched it at the right place, at the right price, on the right platform, at the right time. Nessus didn’t beat the incumbent scanners feature-for-feature. ISS was the heavyweight of the era. But here’s the twist: Nessus was built for Linux—exactly what many security practitioners preferred—and ISS had just dropped Linux support. Meanwhile, the community around Bugtraq skewed hard against commercial tools, and they were hungry for something powerful they could actually get their hands on.

And Nessus was free.

At the time, commercial vulnerability scanners were expensive enough to lock out a huge chunk of the market—researchers, students, small shops, even plenty of real companies. Nessus was a response to both problems: the limitations of existing open-source options and the price tag of the commercial ones. Deraison released it under the GNU General Public License, and adoption spread the way the best open-source projects spread: one download becomes a recommendation, becomes a habit, becomes a standard.

The masterstroke was an architectural choice that turned Nessus from a tool into a living system: plugins. Instead of forcing one person to maintain a monolithic scanner, Deraison built a framework where vulnerability checks could be written and updated independently. That meant Nessus could evolve as fast as the threat landscape—because the community could evolve it. Users weren’t just consumers; they became contributors, testers, and, inevitably, evangelists.

Deraison leaned into that relationship. He lived in the bug reports and feature requests, working days and then working again at night. For months, he’d go until 5 a.m., reverse-engineering obscure, undocumented protocols just to make the scanner more capable.

Nessus started showing up everywhere: government agencies, enterprises, security consultancies, managed security providers. It became the default scanner people reached for. Years later, in 2013, Nessus celebrated its 15th anniversary and was widely considered the de facto standard for vulnerability scanning. By then, it had helped create a generation of practitioners—Nessus experience had become one of those unspoken checkboxes for getting into security.

But embedded inside all that success was a problem that open source hits again and again: the tool was becoming critical infrastructure, and the maintainer was still just… a person.

Deraison worked other jobs—he’d been at SolSoft and even founded a security consulting company, Nessus Consulting S.A.R.L.—while continuing to pour his time into a project used across the world. There was no clean business model attached to “the internet depends on this.” The commitment was to keep Nessus free, but the workload was anything but.

By 2002, Nessus had become essential to enterprise security. Yet its creator was still operating like a volunteer with a day job, trying to support a tool that clearly deserved full-time attention. The question hanging over the project was existential: could open source sustain something this important, or would something have to give?

The answer arrived in the form of two business-minded partners who saw what Nessus could become—if someone could figure out how to build a real company around it.

IV. Founding Tenable & The Open Source Dilemma (2002–2005)

There’s a moment in the life of almost every great open-source project when the story stops being purely technical and starts becoming painfully human. The software is spreading. Organizations are depending on it. The bug reports never end. And the creator has to ask a question that feels almost disloyal: how do you keep this thing alive without burning out—or giving it away to people who will?

That’s the crossroads Nessus hit in the early 2000s. And it’s where Ron Gula enters the picture.

Gula wasn’t just “a security guy.” He’d been a penetration tester at the NSA, the kind of job that trains you to think like an attacker all day and then write the report that keeps defenders up at night. After that, he worked at BBN, developing network honeypots designed to lure hackers in and expose how they moved. He later led penetration testing and incident response teams at US Internetworking. And as CTO of Network Security Wizards—founded with his wife, Cyndi—he helped build Dragon, an intrusion detection system that Gartner recognized as a market leader in 2001.

Just as important: Ron had already lived the “build a security product” journey end to end. Network Security Wizards was acquired by Enterasys Networks. He understood what enterprises actually bought, and it wasn’t just code. It was accountability. It was support. It was the ability to call someone when a scan found something terrifying and the board wanted answers by morning.

Nessus had become indispensable, but it didn’t come with a purchase order, a help desk, or a roadmap that large organizations could rely on. Gula saw the gap—and he also saw the opportunity.

In September 2002, Ron Gula, Jack Huffard, and Renaud Deraison founded Tenable Network Security, Inc. Nessus, the tool Deraison had built and nurtured for years, became the beating heart of the new company from day one. They chose the name “Tenable” from “attainable” and “defendable,” a nod to the idea that security shouldn’t just be aspirational—it should be something you can actually measure and improve.

But Tenable didn’t flip a switch and turn Nessus into an enterprise product overnight. For the first few years, the work was less about flashy new features and more about building the machinery around the software: support, reliability, and the things big customers quietly require before they’ll bet their environments on a tool.

And then came the decision that would define Tenable for years, and permanently change its relationship with part of the community.

On October 5, 2005, Tenable released Nessus 3—and changed the license from the GNU General Public License to a proprietary one. After seven years as an open-source project, Nessus was now commercial software.

The reaction was immediate and loud. A fork emerged to keep an open-source scanner alive, first discussed as GNessUs and then evolving into OpenVAS—proposed by pentesters at SecuritySpace, discussed with pentesters at Portcullis Computer Security, and later amplified to a wider audience when Tim Brown posted it on Slashdot. The vulnerability scanning ecosystem split in two: Nessus on the commercial track, and OpenVAS carrying the open-source torch.

From Tenable’s perspective, the move wasn’t a rejection of open source so much as an admission of reality. Open-source contributions alone couldn’t reliably fund what professional users were now demanding: rigorous testing, enterprise-grade enhancements, and dedicated customer support. Deraison argued that going proprietary would let Tenable invest in faster updates and deeper coverage as new threats emerged—work that required sustained resources, not spare-time heroics.

There was also a competitive issue hiding in plain sight. Under GPL terms, it was possible for others to take Nessus’s code, repackage it, and build businesses around it—while Tenable remained responsible for the hardest parts: keeping the scanner current and credible. Closing the code helped Tenable protect its ability to out-innovate copycats and keep investing ahead of both free and paid competitors.

Right after the change, Tenable introduced mandatory registration for Nessus 3 downloads and rolled out a tiered licensing model: a free version with limited plugins and capabilities, and paid options for full access.

The fork, meanwhile, continued. Nessus began as an open-source project in 1998; in 2005 it went closed-source with Nessus 3; and in 2006 one of the forks was rebranded as OpenVAS. Over time, the two products diverged—not just philosophically, but in the pace and breadth of vulnerability coverage. Nessus ultimately supported substantially more CVEs than OpenVAS, reflecting a simple dynamic in enterprise software: investment and velocity tend to win.

Controversial as it was, the decision unlocked Tenable’s next chapter. With a commercial foundation, the company could fund the kind of research and engineering effort that vulnerability management demanded. And enterprise customers wanted more than a scanner. They wanted distributed scanning across complicated networks, compliance reporting, integrations into existing security programs, and someone to stand behind the product when things broke.

Just as importantly, the organizations that had been using Nessus informally—especially in government and large enterprises—now had a vendor they could actually buy from. And the timing couldn’t have been better: compliance frameworks like PCI-DSS and FISMA were beginning to require vulnerability assessments. Auditors didn’t want a clever tool. They wanted a supported, enterprise-grade system with a name on the contract.

Tenable was building itself to be exactly that.

V. Building the Commercial Engine (2005–2012)

After the 2005 licensing change, Tenable entered the hard middle of the company-building journey. Nessus was everywhere. The brand was trusted. But popularity doesn’t automatically turn into revenue. Now Tenable had to do the most difficult thing a beloved free product can attempt: persuade people to pay, not because the tool was cool, but because the business needed it.

It helped that the world was tilting in Tenable’s favor.

In the mid-2000s, compliance stopped being a side conversation and became a forcing function. PCI-DSS made regular vulnerability assessments mandatory for organizations handling credit card data. FISMA pushed similar requirements across U.S. government agencies and contractors. And even though Sarbanes-Oxley wasn’t a security law, it put public companies under intense pressure to prove they had control over their systems and processes.

The result was simple: vulnerability scanning moved from “best practice” to “audit requirement.” And the moment auditors started asking for evidence, budgets magically appeared.

Tenable rode that wave by moving up the stack. Nessus could tell you what was wrong on a single machine or network segment. Enterprises needed something bigger: centralized management, distributed scanning at scale, reporting that mapped to compliance frameworks, and a way to track remediation over time.

That’s where SecurityCenter came in, now known as Tenable.sc. It was Tenable’s on-premise platform for running Nessus across large, complex environments: coordinating multiple scanners, aggregating results, turning raw findings into executive-friendly reports, and showing trends over time so security teams could prove they were actually getting better. In other words, Nessus became the engine, and SecurityCenter became the dashboard—and for large organizations, that dashboard is what made the purchase feel inevitable.

All of this happened in a brutal competitive arena. IBM’s acquisition of Internet Security Systems in 2006 gave ISS a huge enterprise go-to-market machine. Qualys, founded in 1999, had already embraced a SaaS delivery model and pushed hard on cloud-based scanning. And Rapid7 was emerging as a fast-moving rival, building its own vulnerability management suite.

Tenable’s response wasn’t to outspend everyone. It was to out-execute with discipline.

For much of its first decade, Tenable operated with a capital-efficient mindset, closer to a bootstrapped company than a venture-fueled rocket ship. Growth came from the Nessus user base that already trusted the technology, from government contracts that valued credibility and continuity, and from partners who could deliver the product without Tenable having to build a massive direct sales army overnight.

A big part of that edge came from research. Scanning technology is only half the battle; coverage and freshness are the real game. Tenable invested heavily in vulnerability researchers who could discover issues, contribute back to the security community, and—most importantly—keep the Nessus plugin database comprehensive and current. That plugin pipeline became a moat: the faster you can translate new vulnerabilities into reliable checks, the more valuable you are to customers who live in constant patch-and-exploit cycles.

Distribution mattered too. The MSSP and broader channel ecosystem gave Tenable leverage. Partners could resell Nessus and SecurityCenter and wrap them inside managed offerings, which helped Tenable reach mid-market customers without paying the full cost of a direct enterprise sales motion. And as those MSSPs standardized on Tenable’s tools, they became a standing referral engine—advocates who were effectively building Tenable’s reputation one customer environment at a time.

By 2012, with Ron Gula as CEO, Tenable had turned a category-defining scanner into a real commercial business: thousands of customers, clear leadership in vulnerability management, and proof that the open-source-to-enterprise transition could work—even after the pain of the licensing shift.

But the next threat wasn’t another scanner company. It was an architectural shift in how computing worked.

Cloud infrastructure was starting to break the assumptions vulnerability management had been built on—static networks, known IP ranges, long-lived servers. Tenable’s products had been designed for a world you could map. The world was becoming one you had to constantly rediscover.

The question hanging over the company wasn’t whether vulnerability management mattered. It was whether Tenable could rebuild itself for an environment that never stopped moving.

VI. The Cloud Inflection Point & Tenable.io (2012–2016)

From 2012 through 2016, Tenable ran straight into a problem that wasn’t about features or competition. It was about physics.

Vulnerability management had been built for a world with edges. A corporate network had a perimeter, a data center had racks, and servers tended to stick around long enough for a weekly scan to mean something. But by the early 2010s, cloud adoption was no longer a curiosity. AWS had been around since 2006, yet it wasn’t until this period that “hybrid” started to look inevitable—and “cloud-first” started to look sane.

For a scanning company, that shift was terrifying.

Traditional scanning assumed stability: known IP ranges, persistent assets, and a schedule you could depend on. Cloud infrastructure broke every one of those assumptions. Virtual machines spun up and disappeared. Containers could live for minutes. IP addresses were assigned dynamically, recycled, and reused. A periodic scan against a “stable inventory” starts to feel like taking a photograph of a freeway and calling it traffic monitoring.

So Tenable made one of the defining decisions in its history: rebuild for this new reality, even if it meant undercutting its own success. The result was Tenable.io, which Tenable made available in January 2017 as a cloud-based vulnerability management platform designed for modern, elastic environments.

The launch reflected years of work and a blunt diagnosis. Amit Yoran, who became CEO in 2016, put it this way: “Networks, assets and threats have all changed dramatically over the last few years, but vulnerability management hasn’t kept up.”

Just as important, Tenable.io wasn’t “SecurityCenter, but hosted.” It was a full rewrite, designed around the complexity of modern IT. Deraison captured what had changed: “In the modern world of IT, applications can be deployed in many different ways ranging from on-premises deployment to various forms of virtualization technologies running in public and private clouds.”

One of the biggest shifts was what Tenable chose to track. In a world where IP addresses come and go, tying security to an IP is like tying identity to a hotel room number. Tenable.io focused on assets instead. Using an asset fingerprinting algorithm, it aimed to identify the true resource behind the noise—even when that resource was a laptop on the move, a short-lived VM, or a cloud instance that could be rebuilt from scratch tomorrow.

That architectural change also reshaped the business model. Tenable.io was licensed by assets rather than IP addresses. It wasn’t just a pricing tweak; it was Tenable aligning how it charged with how customers actually thought about their environments.

Tenable.io also pushed the company into adjacent problem areas that were becoming impossible to ignore. Web application scanning, for example, was a different beast—and Deraison didn’t pretend otherwise: “Web application scanning has become extremely complex and you have to do a bunch of things that frankly Nessus has not been adapted to do. So we took a long hard look and we decided to build a brand new product.”

Containers were another frontier. In October 2016, Tenable acquired FlawCheck, a container security vendor, and brought that technology into the platform as Tenable.io Container Security, designed to continuously monitor container images for vulnerabilities, malware, and policy compliance.

Underneath all of this was the real gamble: Tenable was choosing to cannibalize. SecurityCenter was a proven on-prem product with real revenue and customers who still ran traditional data centers. But Tenable’s leadership recognized the trap. If they waited until cloud adoption was universal, they wouldn’t be “transitioning.” They’d be chasing—behind cloud-native competitors that had been built for ephemerality from day one.

Deraison was direct about the direction of travel: “Security Center will continue to be maintained for a very long time, but we believe that customers will get way more value from Tenable.io.”

It’s one of the hardest moves in tech: building the thing that could eventually replace your flagship, before anyone forces you to. Tenable made that call—and it set up the next chapter of the company’s growth.

VII. The Private Equity Chapter: Insight Partners & Accel (2012–2018)

For its first decade, Tenable ran like a capital-efficient, founder-led machine. But there’s a ceiling to how fast you can scale a global enterprise sales force on pure operating cash—especially in cybersecurity, where credibility is table stakes and coverage has to keep pace with a threat landscape that never slows down. Eventually, to go bigger, you need fuel.

Tenable’s funding story reflects a company that raised when it chose to—not because it had to. Its first major institutional round didn’t arrive until 2012, after the business was already established and profitable.

In September 2012, Tenable raised a $50 million Series A from Accel Partners. This wasn’t money to find product-market fit. It was growth capital to expand a proven one: a company that had already spent years turning Nessus and its enterprise platform into a real commercial engine.

Then came the round that truly set the trajectory. In November 2015, Tenable announced a $250 million Series B led by Insight Venture Partners and Accel. At the time, it was one of the largest fundraises for a private security company—and the intent was straightforward: accelerate long-term global growth.

By that point, Tenable had raised $300 million in total. Ron Gula used the moment to sharpen the positioning, emphasizing Tenable’s “continuous network monitoring” story and pointing to the kind of customers it served—large, complex networks operating under constant pressure.

The investors echoed the thesis. Insight’s Richard Wells framed it as a bet on a big, universal problem: vulnerability and security risk as a top concern across every sector. Accel’s Ping Li emphasized Tenable’s adoption among major customers and the way CISOs increasingly saw Tenable as a central hub for understanding and improving security posture.

And Tenable didn’t sit on the cash. The company expanded aggressively—adding more than 200 employees in 2015 and pushing hard on channels and international reach. It operated in 10 countries and announced plans to expand into 10 more, including China, Mexico, Ireland, Sweden, the United Arab Emirates, and India.

Another credibility booster landed here too: Tenable partnered with In-Q-Tel to provide cybersecurity services to the United States Intelligence Community. In government, that kind of relationship can be meaningful revenue. In the commercial market, it’s something else just as valuable: a signal. If the intelligence community trusts your scanner, it’s easier for an enterprise buyer to trust it too.

Then, in 2016, the company made a leadership move that often shows up right before a major scale-up. Ron Gula stepped down as CEO and became chairman. Tenable brought in Amit Yoran—previously CEO of RSA Security (a division of Dell)—to lead the next phase. Gula had taken Tenable from nothing to a substantial business, including surpassing $100 million in annual revenue. But pushing into the next chapter would demand a different kind of operating cadence.

By the time Yoran took over, Tenable had become a global standard in vulnerability management, serving more than 20,000 customers worldwide and backed with $300 million in capital. The company was now set up for the obvious question that comes next when a category leader reaches this stage: do you get acquired, or do you go public?

VIII. Going Public: The 2018 IPO

By 2018, Tenable had done the hard parts that usually come before a public debut. It had rebuilt for the cloud, installed a new CEO built for scale, and leaned into a clear story: Tenable wasn’t just a scanner company, it was the category leader in vulnerability management. The question was what you do next when you’re already the default choice in so many security teams.

In late July 2018, Tenable answered that question by going public.

On July 26, 2018, Tenable’s stock hit the market and immediately popped. Shares were priced at $23, above the expected $20 to $22 range, then opened at $33, jumped as much as 40% in the debut, and finished the day at $30.25—up 31.5%. The offering raised about $250 million, and the first-day move pushed the company’s market value above $3 billion.

A few days later, on July 30, 2018, Tenable Holdings announced the closing of its IPO: 12,535,000 shares sold, including the underwriters’ full option for an additional 1,635,000 shares. Gross proceeds to Tenable, before fees and expenses, were approximately $288.3 million.

Investors had a pretty straightforward thesis to latch onto. Kathleen Smith of Renaissance Capital summed up the appeal: “The strength here is it's growing really fast, there's lots of recurring revenue and the valuation looks reasonable.” She pointed to Tenable’s ability to keep subscriptions going across roughly 24,000 client firms—and to expand within existing accounts, as customers increased their subscriptions after signing on.

That recurring-revenue profile was central to the IPO pitch. Tenable’s enterprise platform offerings were primarily sold as subscriptions, usually prepaid, with terms generally running one to three years (most commonly one year). And those subscriptions were becoming more of the business over time: enterprise platform revenue rose from 58% of total revenue in 2016 to 72% in the first quarter of 2018.

Financially, Tenable reported $206 million in revenue for the 12 months ended March 31, 2018. But the story it took to Wall Street wasn’t “we scan networks.” It was bigger: Tenable’s platform provided broad visibility across an organization’s modern attack surface and helped translate vulnerability data into business insights—so leaders could understand and reduce cyber risk, not just generate reports.

Morgan Stanley, J.P. Morgan, Allen & Company LLC, and Deutsche Bank served as the active book-running managers. The deal was heavily oversubscribed, a sign of just how strong investor demand was for cybersecurity names at the time.

For Tenable, the IPO was the capstone on a twenty-year arc: from Deraison’s first Bugtraq email, to an open-source tool that defined a market, to the painful decision to commercialize, through a cloud rewrite and a CEO handoff designed for scale. Going public wasn’t just about raising capital. It was the market confirming something Tenable had spent years proving: vulnerability management wasn’t a niche practice anymore. It was a durable, essential category of enterprise software.

IX. The Exposure Management Pivot (2018–2021)

Going public didn’t just add quarterly scrutiny. It gave Tenable a bigger platform—more capital, more credibility, and a louder microphone. And with that microphone, Tenable had to answer a question that was starting to feel existential: what, exactly, are we the category leader in?

“Vulnerability management” had built the company. But it was also starting to box it in. More and more security vendors were tacking on vulnerability scanning as a feature inside broader suites. If scanning became table stakes, Tenable couldn’t afford to sound like “the scanner company.” It needed a larger story—one that framed Tenable as the system of record for cyber risk, not just the tool that found the flaws.

That’s where Amit Yoran’s leadership mattered. Yoran came to Tenable with rare, across-the-stack credibility: a West Point graduate who founded NetWitness and sold it to RSA, later served as RSA’s president, helped stand up the US-CERT program at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and co-founded Riptech—an early managed security service provider acquired by Symantec in 2002.

In December 2016, after co-founder Ron Gula retired, Yoran became Tenable’s chairman and CEO. He then led the company through its 2018 IPO—and pushed Tenable to expand beyond the compliance-first framing that had dominated vulnerability management for years.

The shift was clear in how the market described Tenable’s direction. An IDC market share report captured it bluntly: “Tenable is working toward moving its customers away from vulnerability management as a compliance-based reporting medium into a risk-based solution designed to help organizations manage and measure cyber-risk across the modern attack surface.”

To make that vision real, Tenable introduced Tenable Lumin, positioning it as a way to translate raw technical findings into business-level insight—visualizing, measuring, and benchmarking cyber risk alongside other risk metrics. The message was simple, and it was a major reframing: it’s not enough to know you have vulnerabilities. You need to know which ones matter, what they mean for the business, and how to communicate that clearly to executives and boards.

Under that broader “exposure” umbrella, Tenable kept its leadership in the core market. It was ranked number one in global market share and revenue for device vulnerability management in 2018 and 2019, and it was growing more than twice as fast as its closest competitor. Tenable also reported the largest Common Vulnerabilities Exposure (CVE) library among vulnerability management vendors and said it uncovered over 100 zero-day threats in 2019.

The product footprint expanded too. Tenable’s acquisition of industrial security leader Indegy brought IT vulnerability management into closer alignment with industrial cybersecurity, leading to Tenable.ot—positioned as the industry’s first unified, risk-based view across IT and operational technology (OT) security.

Years later, Yoran’s story took a heartbreaking turn. He was diagnosed in March 2024 with a treatable form of cancer. In December 2024, he temporarily stepped away from his role as CEO after learning he needed additional treatment. He passed away unexpectedly on January 3, 2025. Tenable appointed CFO Steve Vintz and COO Mark Thurmond as co-CEOs, and lead independent director Art Coviello became chairman of the board.

“Amit was an extraordinary leader, colleague, and friend. His passion for cybersecurity, his strategic vision, and his ability to inspire those around him have shaped Tenable's culture and mission,” Coviello said in a statement.

X. Modern Era: Platform Consolidation & AI Integration (2021–2025)

The post-pandemic era hit Tenable with a familiar kind of pressure: the world changed faster than the security stack could keep up.

Remote work pulled critical systems out of neat corporate networks and into messy, hybrid reality. Cloud adoption went from “strategic initiative” to “we need this working by Monday.” Every new SaaS app, VPN, endpoint, and cloud account became another place vulnerabilities could hide—and another place attackers could look.

At the same time, the cybersecurity market kept consolidating. Buyers increasingly wanted fewer vendors and more “platform” suites, where tools came bundled and stitched together under one dashboard. For Tenable, a company built on being the best at a specific, essential job, that shift created a new challenge: staying the category leader while the category itself risked becoming just one checkbox inside someone else’s bundle.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music