Telephone & Data Systems: The Story of America's Last Independent Regional Wireless Pioneer

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

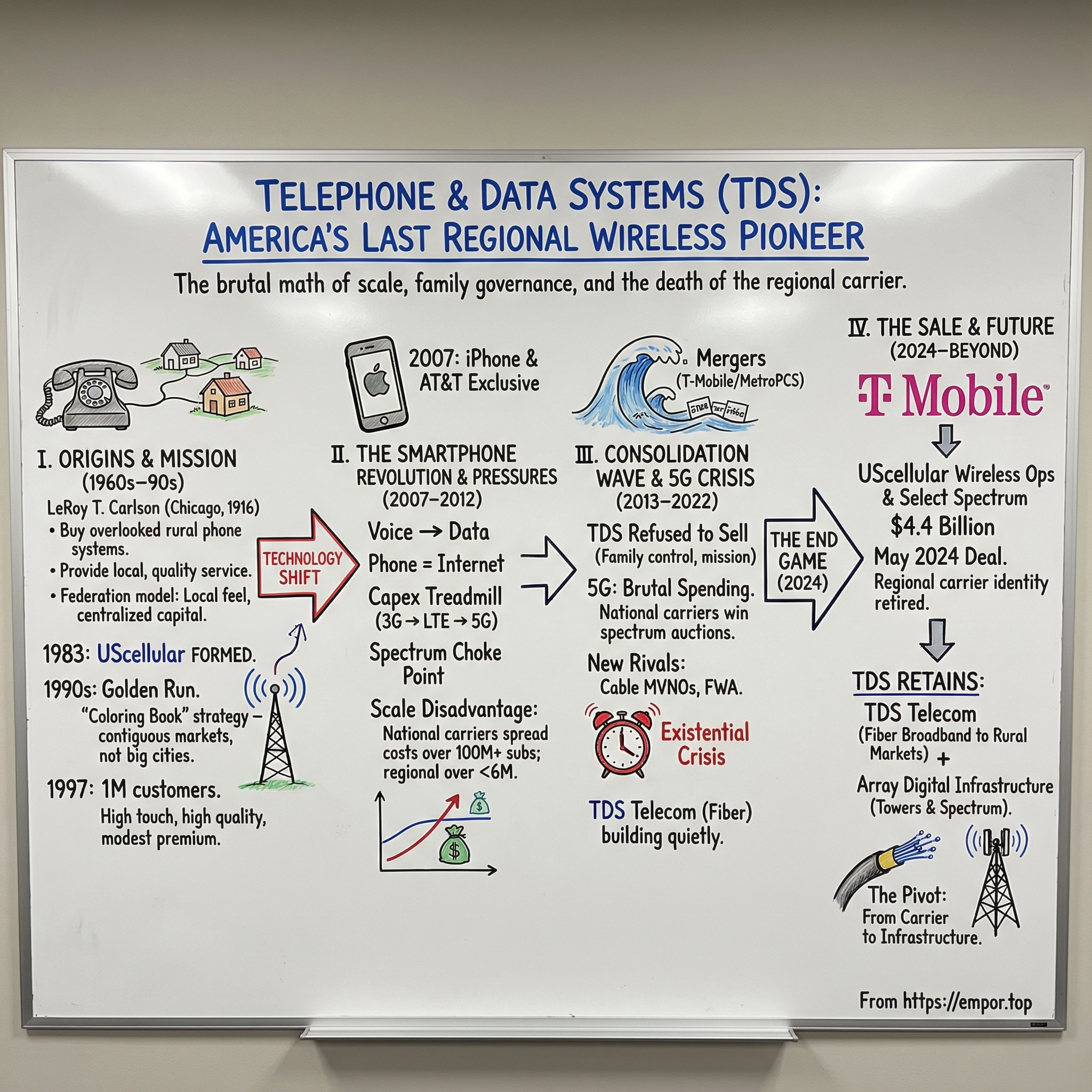

Picture a Chicago boardroom in August 2023. Three generations of the Carlson family sit around the table as the slides roll: subscriber counts trending down, coverage maps that make UScellular look smaller every year, and a 5G build that reads less like an upgrade and more like a bill you can’t dodge. For fifty-four years, the Carlsons had built and defended an independent telecom empire with a simple mission: connect the rural communities the giants overlooked. Now they were staring at the question that mission had postponed for decades: is staying independent still brave… or just expensive?

That summer, the company kicked off a strategic review. The process was exhaustive, and by the end, the independent directors at UScellular had unanimously recommended a deal. Both boards — UScellular’s and TDS’s — unanimously approved it. The outcome was one of the most consequential telecom transactions in years: UScellular’s wireless operations would be sold to T-Mobile.

That decision is where our story begins, because it forces the bigger one. TDS is a case study in infrastructure economics, family governance, and the brutal math of scale. It’s in the middle of a hard pivot — from a diversified telecom operator to something narrower and more defensive: a business anchored in fiber broadband and towers.

So here’s the deceptively simple question: how did a Chicago family business survive the great telecom consolidation wave — and should it have tried? The answer tells you something uncomfortably universal about infrastructure: when the technology cycle turns, mission and loyalty don’t change the cost curve. And the hardest strategic skill isn’t building a winning hand. It’s knowing when a winning hand has started to turn.

Back in 2010, TDS was a Fortune 500 company traded on the NYSE. It employed about 12,300 people and served more than 7 million customers across 36 states — one of the biggest U.S. phone companies not born from the old Bell system. Today, it’s almost the opposite story: the wireless business it helped pioneer is on its way out, and the future is a bet on fiber and tower infrastructure.

This is the story of the death of the regional wireless carrier in America. It’s a story about spectrum — a finite resource that can be a moat one decade and a millstone the next. And it’s a story about 5G: technology powerful enough to reshape an industry, and expensive enough to make independence feel like denial. But it’s also a family story, about three generations of Carlsons who kept saying yes to the communities everyone else said no to — right up until the moment the economics stopped letting them.

II. The LeRoy T. Carlson Empire: Origins of a Telecom Dynasty (1968–1990s)

LeRoy T. Carlson was born on Chicago’s South Side in 1916, the son of Swedish immigrants who prized work ethic, education, and self-reliance. He was the middle of three children, raised in a tight-knit Swedish neighborhood, and he carried that blend of discipline and ambition for the rest of his life.

He stacked credentials early: a bachelor’s degree from the University of Chicago, then an MBA from Harvard Business School in 1941. He served in World War II, returned home, and went looking for his next chapter. Before telecom, he tried on a few: manufacturing, real estate, and a string of operating roles that sharpened his instincts for messy, asset-heavy businesses. One deal in particular became the bridge. When he purchased Suttle Equipment Company, he got a front-row seat to the telephone industry—and to the opportunity hiding in plain sight.

By the late 1950s, Carlson had noticed what most of the market ignored: rural America was filled with small, independent phone companies that worked hard, served their towns, and were chronically undercapitalized. Many were family-run. Some were farmer cooperatives. Nearly all of them needed to modernize their networks, but didn’t have the balance sheet to do it.

Carlson did. And more importantly, he had the temperament for it.

In 1967, he returned full-time to the operating telephone business. Then, in 1967 and 1968, he and a close friend acquired ten rural Wisconsin telephone companies. Those deals became the foundation of Telephone and Data Systems, incorporated on January 1, 1969.

The founding idea was simple and unusually durable: buy overlooked local phone systems, invest in better technology, and win by treating customers like neighbors, not line items. TDS Telecom was built through steady acquisitions of telephone companies started by local families, farmers, and co-ops. Carlson’s goal wasn’t just to own these systems—it was to upgrade them, keep the service personal, and prove that small communities deserved first-class connectivity too.

From the beginning, Carlson also made a structural decision that shaped everything that followed: TDS would be a holding company, not one giant monolithic operator. Local teams kept day-to-day control and community relationships. The parent company provided capital, shared services, and the leverage of buying power and coordinated technology rollouts. It was a federation model: local feel, centralized discipline.

Growth came quickly. In 1974 and 1975, TDS added eight more companies in Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee and crossed its one-hundred-thousandth customer. With roughly 500 employees, the company had outgrown its original setup. So in July 1974, TDS reorganized into regions—Wisconsin, Northeast, Southeast, and Mid-Central—creating a template for scaling without losing the “we know your name” advantage.

Then the industry changed.

The 1980s—especially the post-AT&T breakup era—created a rare opening for companies that weren’t part of the old Bell system. The Baby Bells were focused on dense, high-return metro markets. They had little interest in scattered rural territories. Meanwhile, the regulatory push for universal service created steadier economics for operators willing to invest in infrastructure outside major cities. For TDS, this wasn’t a footnote. It was a tailwind.

But Carlson’s most consequential move came even earlier than most people would have expected: wireless.

In 1983, cellular telephony was still more novelty than necessity. Yet Carlson could see the direction of travel. On December 23, 1983, TDS formed a new subsidiary—United States Cellular Corporation—to handle its growing cellular activities. It was small, often pushed around by larger players, and regularly underestimated. That didn’t sit well with Carlson. He fought aggressively for UScellular’s place in the market—and often won.

The early cellular licensing environment was a kind of Wild West: applications, negotiations, and plenty of horse-trading. Through an industry-wide agreement, the company was awarded licenses for cellular networks in Knoxville and Tulsa. Then, in March 1985, TDS made its bet unmistakable. It chose to sell its cable television holdings and devote its attention—and capital—to UScellular. Cable had promise, but cellular looked like the higher-growth, higher-return future. And it threatened wireline in a way cable didn’t.

The cable exit wasn’t symbolic; it funded the pivot. TDS generated $41 million from selling its cable systems, completing the last sale in November 1986, and redeployed that capital into cellular. Those early licenses would go on to become some of the most valuable assets the company ever owned.

That same year brought a leadership handoff. On his 70th birthday in 1986, LeRoy stepped back from daily management, and his son Ted became President and CEO. It marked the start of a second-generation era that would steer the business for decades.

Carlson also left behind another enduring feature: control. The Carlson family maintained voting power through a special class of stock—Series A Common Shares—that allowed them to elect a majority of the Board. It insulated TDS from short-term market pressure and hostile takeovers. Later, it would become a flashpoint, especially when the industry’s economics shifted and outsiders began asking whether independence was still the right answer.

By the end of the 1980s, TDS had become something rare in American telecom: a family-controlled holding company with meaningful wireline and wireless assets, a service-first culture, and a clear mission to build where the giants wouldn’t. The foundation was in place for an extraordinary run.

And, quietly, the seeds of the eventual reckoning were too.

III. The Wireless Gold Rush: UScellular's Rise (1990s–Early 2000s)

The 1990s were UScellular’s golden run: the decade when the Carlson family’s unglamorous bet on rural and suburban America stopped looking quaint and started looking brilliant.

The numbers told the story. UScellular’s subscriber base jumped 66 percent in 1995. In 1996, it grew another 56 percent, even as other carriers started to see demand soften. And in January 1997, the company added its one millionth customer—meaning it had doubled in just two years.

That kind of growth wasn’t an accident. UScellular didn’t try to win the biggest, flashiest cities where licenses were expensive and the Baby Bells could spend anyone under the table. Instead, it built what executives called the “coloring book” strategy: carefully filling in contiguous blocks of smaller markets—especially across the Midwest and Northwest—so the network could be built efficiently and managed like a coherent territory, not a scattered collection of outposts.

Even as it expanded, UScellular stayed disciplined about where it played. And in the late ’90s, that looked like a competitive cheat code. As the Chicago Tribune observed on May 11, 1997, UScellular benefited because its markets “ha[d not] attracted the competitors flocking to larger markets like Chicago and Los Angeles.” In other words: while everyone else fought knife battles in the biggest arenas, UScellular kept racking up wins in places the giants barely bothered to scout.

The strategy also matched the culture. These were customers who wanted a carrier that showed up—stores in town, service reps who didn’t treat them like a ticket number, and a company willing to invest in coverage even when the population density didn’t make the spreadsheets sing. In those markets, UScellular’s local presence and customer service weren’t just marketing. They were the product.

Then came the big technology shift of the era: analog to digital. The late 1990s forced every carrier onto a capital spending treadmill. But for operators that executed well, it was also an opportunity to pull away. UScellular invested heavily, earned industry recognition for its network, and built a reputation for strong call quality and customer service—good enough that it could often charge a modest premium without losing the relationship.

From the outside, it looked like a regional carrier that had found the playbook. The customer base kept climbing, and by 2010 it hit its high-water mark: 6.2 million subscribers. UScellular was headquartered in Chicago and had become the nation’s sixth-largest wireless carrier. It would never be that big again.

At its peak, the value proposition was simple and coherent: better service than the national players, a real local footprint through community-focused retail, and network quality that held up where it operated. Pay a little more, get treated better—and get a carrier that acted like it belonged to your town.

And of course, this was also the period when telecom consolidation started to roll like a storm front. The early 2000s created plenty of chances for TDS to sell UScellular at premium valuations. National carriers wanted what UScellular had: spectrum, customers, and working networks in territories that could plug right into bigger footprints. The interest was real.

The Carlson family kept saying no. They believed independence protected customers, created opportunity for employees, and preserved the mission that had built the company in the first place.

In hindsight, that choice reads two ways: principled stewardship or stubborn entrenchment. At the time, it felt entirely defensible. Customer service metrics stayed strong. Network investments still paid off. Growth slowed, but it remained positive. Most importantly, the advantages that made UScellular special still looked durable.

What the Carlsons couldn’t see—what almost no one fully understood yet—was that wireless was about to enter a new era, and the rules that made a great regional carrier possible were about to be rewritten.

IV. The Smartphone Revolution & The Beginning of the End (2007–2012)

On January 9, 2007, it was a normal winter day at TDS headquarters in Chicago. In San Francisco, Steve Jobs walked onstage and kicked off the era that would break the business model of the regional wireless carrier.

Apple introduced the iPhone as three things in one: a phone, an iPod, and an internet device. Jobs called it “five years ahead” of anything else. Then came the part that mattered just as much as the hardware: Apple picked a single U.S. carrier partner. Cingular—soon to be AT&T—would be the exclusive home of the iPhone.

For a company like UScellular, the announcement landed like a slow-motion shockwave. The implications were obvious only in hindsight, but they were devastating.

First, wireless stopped being a voice business and became a data business. In the old world, the product was call reliability and local coverage. In the new world, the product was fast internet everywhere—email, maps, web browsing, streaming—across an entire footprint. That meant far more equipment, far denser networks, and a never-ending upgrade cycle. Capital spending didn’t just rise. It became the price of admission.

Second, the phone itself became the competitive weapon. Exclusive device deals—first the iPhone with AT&T, and later various Android launches tied to other big carriers—made “having the right handset” a reason to switch. Smaller operators couldn’t get the same terms, the same marketing muscle, or the same early access. UScellular wouldn’t begin offering Apple products until later in 2013—six years after the iPhone debuted, which in consumer electronics might as well be a generation.

Third, and most brutally, smartphones rewired customer expectations around coverage. In the voice era, a customer could tolerate a carrier that was great in Iowa and irrelevant in California. Most people didn’t travel constantly, and roaming filled in the edges. But once your phone became your internet connection, “works everywhere” turned from a nice-to-have into the baseline. A regional footprint—UScellular’s defining strategic choice—started to look less like focus and more like a limitation.

UScellular didn’t sit still. In October 2008, it launched Mobile Broadband, promising data speeds roughly 10 times faster than before. Using EVDO technology—what most consumers understood as 3G—it brought something close to DSL-like capability to phones and mobile devices.

But the treadmill had started. By the time UScellular had pushed 3G through its markets, the rest of the industry was already sprinting toward 4G LTE. UScellular began offering 4G LTE coverage in the first quarter of 2012—because it had to. LTE was clearly the future, and any carrier that failed to deploy it was signing its own obituary.

This is where the quiet structural problem became loud. In the voice era, UScellular’s scale disadvantage was real but survivable. In the data era, it became existential. The national carriers could spread the cost of each new network generation across well over 100 million customers. UScellular was trying to fund the same basic technology leap on a fraction of the subscriber base. The per-customer math didn’t work in their favor—and it got worse every year.

At the same time, spectrum became a choke point. Data usage exploded, and spectrum is finite. In FCC auctions, the biggest checkbooks won. And the carriers with nationwide footprints could deploy new spectrum more efficiently, because every network investment had more customers to monetize.

You could see the shift in customer behavior. UScellular had long been able to charge a bit more, because it offered strong local network performance and service that felt human. But the smartphone era changed the question customers asked. It stopped being, “Who treats me best in my town?” and became, “Why am I paying more here when Verizon or AT&T will work better when I leave?”

Inside the company, this was the dilemma Ted Carlson had to live with. LeRoy T. Carlson, Jr. had joined TDS in 1974 as a vice president, became president in 1981, and CEO in 1986—a role he held until January 2025. Under his leadership, UScellular faced an ugly choice: transform by spending enormous sums on an uncertain return, or protect the balance sheet and watch the competitive position erode.

The LTE decision captured that bind. Building 4G was mandatory, but it was also punishingly expensive for a regional carrier. UScellular committed anyway, investing hundreds of millions annually in network infrastructure. And every dollar poured into LTE was a dollar not spent on the other weapons the national carriers used—huge marketing budgets, aggressive promotions, and device subsidies designed to pull customers away and keep them locked in.

By the end of this period, UScellular still had a real business. But the underlying equation had flipped. Operational excellence and customer service could no longer overcome the brutal advantage of national scale in a data-hungry, spectrum-constrained, capital-intensive industry.

The seeds of the eventual sale were planted here—even if it would take another decade for the consequences to fully arrive.

V. The Consolidation Wave TDS Refused (2013–2018)

Between 2013 and 2018, the American wireless industry didn’t just evolve. It compressed. Deal after deal turned a crowded ecosystem into a handful of giants. And TDS—owner of UScellular—mostly watched it happen.

The signal moment came right at the start of the period. In October 2012, MetroPCS agreed to merge with T-Mobile USA in a deal structured as a reverse merger. When it closed on May 1, 2013, the combined company became T-Mobile US and began trading on the New York Stock Exchange. It was a clear message to the market: scale wasn’t optional anymore.

From there, the logic of consolidation became hard to argue with. Regional operators were steadily losing relevance as national carriers stacked advantages: spreading network upgrade costs across tens of millions of customers, negotiating better device deals, spending bigger on advertising, and offering coverage that worked everywhere without caveats. Research firm iGR estimated that subscribers served by regional operators fell sharply from 2012 to 2014.

By the mid-2010s, only a small group of notable “Tier 2” carriers remained independent—names like C Spire, UScellular, ATN, Ntelos, and Cincinnati Bell—together serving only a few million customers. The list was getting shorter every year.

TDS still didn’t move. Not as a buyer, and not as a seller.

The Carlson family’s reasoning blended principle and pragmatism. Selling, they believed, would abandon the very communities the company existed to serve—places larger carriers routinely under-invested in. Buying wasn’t realistic either; the remaining regional carriers were expensive, and mergers rarely solve a scale problem if the combined footprint is still regional. And UScellular still had something real: strong positions in certain markets and a base of customers who genuinely liked the company.

But critics read the same decision differently. To them, this was what entrenched control looks like: a family insulated by a dual-class structure, able to reject market pressure even as evidence piled up that “regional wireless” was turning into an endangered category.

Instead of a big, decisive deal, UScellular began quietly trimming the map. The company pursued a series of asset sales—transactions that could be framed as discipline, but also looked like a slow retreat. One of the most symbolic: UScellular announced the sale of several markets to Sprint, including Chicago.

Chicago wasn’t just any market. It was the hometown—where LeRoy Carlson was born, where TDS was headquartered, and where the company’s identity had been built. Exiting it was an admission, even if no one said it out loud: UScellular couldn’t win in major metros against carriers with deeper pockets and stronger spectrum positions.

The reshuffling continued. UScellular exited non-contiguous markets, sold licenses where its competitive standing was weakest, and concentrated more tightly on the Midwest and Northwest—the places where it still felt like a local champion rather than a small fish in a big-city tank.

And hovering over all of this was spectrum. Every FCC auction became its own stress test. UScellular kept showing up, but the national carriers kept winning—because they could. Each time UScellular got outbid, it wasn’t just losing an auction. It was watching tomorrow’s network capacity get handed to competitors who already had more scale.

While wireless turned into a knife fight, a quieter story inside the holding company started to matter more. TDS Telecom—the wireline subsidiary that rarely got the spotlight—was steadily building fiber broadband in small towns across America. There was an irony to it that would have made LeRoy Carlson smile: the original business, rural connectivity, was becoming more strategically valuable just as the wireless bet he made decades earlier became harder to justify.

TDS’s leadership consistently framed family control as a feature, not a bug. As the company put it:

TDS is controlled by the family that founded the Company over 50 years ago. While we understand this structure is not typical for public companies in the United States, it has provided TDS the ability to make investments that may have longer-term benefits for all stakeholders, achieving business stability and a positive culture for our people.

It wasn’t just PR. The Carlsons did see themselves as stewards.

But by 2018, the environment didn’t care about good intentions. The financial pressure was rising, subscriber losses were harder to dismiss, and with each quarter, the menu of strategic options got smaller.

VI. The 5G Existential Crisis (2018–2022)

If the iPhone lit the fuse, 5G threatened to finish the job.

On paper, 5G was a leap: faster speeds, lower latency, and a platform for new categories like the Internet of Things. In real life, for most consumers, it looked like “my phone internet is a bit faster.” For carriers, it looked like something else entirely: another massive round of spending, on top of everything they’d already sunk into LTE.

And 5G wasn’t one upgrade. It was three networks layered on top of each other—low-band for coverage, mid-band for capacity, and high-band for speed—each with its own spectrum, its own equipment, and its own deployment quirks. For a national carrier, that was painful but doable. For a regional carrier, it was brutal. The checks got written either way; the difference was how many customers you had to spread them across.

That set up UScellular’s dilemma in its purest form. Customers weren’t demanding 5G loudly enough to pay materially more for it. But any carrier that didn’t build it risked looking dated—and in wireless, “dated” becomes churn.

So UScellular did what it had always done: it showed up and tried to play the game.

In June 2019, the company bid in the FCC’s Millimeter Wave Spectrum Auctions, buying high-frequency licenses covering 98 percent of its subscribers for $256.0 million. A few months later, in October 2019, it announced plans to launch 5G. In February 2020, it unveiled its first 5G-capable phone, the Samsung Galaxy S20, and published coverage maps for its first commercial 5G network in parts of Iowa and Wisconsin—both urban and rural.

But the rollout could only ever be selective. UScellular focused on the markets where it was strongest, because it didn’t have the capital—or the strategic logic—to chase nationwide parity. Even so, the investment was significant, and the revenue uplift was not. The scale problem that LTE exposed now became impossible to ignore: the national carriers could amortize 5G across more than 100 million subscribers; UScellular was funding a similar technology transition across a fraction of that base.

And the subscriber line started to bend the wrong way, faster. Losses piled up quarter after quarter. The second quarter brought another 40,000 postpaid phone subscriber decline, following a 44,000 loss the quarter before.

Then, just as 5G demanded the biggest spending cycle yet, a new competitor arrived with a business model designed to avoid spending cycles altogether: cable.

Comcast’s Xfinity Mobile and Charter’s Spectrum Mobile entered wireless as MVNOs—mobile virtual network operators—selling service on Verizon’s network without having to build their own. That meant no tower builds, no spectrum wars, no endless equipment upgrades. They could price aggressively, bundle wireless with home broadband, and sell to millions of households they already billed every month.

This wasn’t a theoretical threat. Comcast and Charter posted big wireless growth in Q2 2024—Comcast added 322,000 wireless subscribers, and Charter added 557,000 mobile lines. The point wasn’t the exact count. It was the direction: cable was becoming a real force in mobile, and it was doing it with a cost structure that regional carriers couldn’t match.

At the same time, the boundary between wireless and wireline started collapsing from the other direction. Fixed wireless access—home broadband delivered over 5G—became a major push for T-Mobile and Verizon. Suddenly, the national wireless giants weren’t just competing with UScellular for phone customers. They were also taking aim at TDS Telecom’s bread-and-butter wireline broadband markets. The old logic of “wireless over here, wireline over there” was breaking down, and neither side of TDS was naturally advantaged in the converged fight.

The pandemic briefly made it easier to believe the situation might stabilize. Connectivity demand surged as work and school moved home. Rural markets saw new arrivals from cities. Usage spiked, revenues held up, and the pace of deterioration didn’t feel quite as relentless for a moment.

But the underlying math didn’t change. UScellular carried debt tied to mid-band spectrum purchases made to stay relevant in 5G. As revenues softened, investing in network improvements got harder—right when network quality and customer experience were becoming even more decisive. UScellular itself acknowledged it was falling behind.

That’s when the company started reaching for the levers it still controlled. One of the biggest was towers.

UScellular owned roughly 4,400 cell towers—real assets with real value. Selling or leasing towers could generate cash without immediately shrinking the subscriber base. But it came with a darker subtext. Tower monetization is often described as “unlocking value.” In the language of distressed businesses, it can also sound like “selling the furniture”: a one-time infusion that doesn’t fix the core problem, and can leave you with fewer options later.

By 2022, management was boxed in. Keep investing in 5G and watch capital drain away into an arms race you can’t win. Slow down, and watch the network gap widen until customers leave even faster. The regional wireless death spiral wasn’t a metaphor anymore. It was the operating reality.

VII. The End Game: The 2024 Sale Decision & What Went Wrong

The public inflection point came on August 4, 2023. TDS and UScellular announced that both Boards of Directors had decided to “initiate a process to explore a range of strategic alternatives for UScellular.”

In corporate English, “exploring strategic alternatives” usually means one thing: we’re for sale. And in this case, it was the first time the company said out loud what the industry math had been screaming for years. UScellular’s run as an independent wireless carrier was nearing its end.

Less than a year later, the euphemism turned into a contract.

CHICAGO, May 28, 2024 /PRNewswire/ — UScellular and TDS announced they had entered into a definitive agreement to sell UScellular’s wireless operations and select spectrum assets to T-Mobile for a purchase price of $4.4 billion, made up of cash plus up to approximately $2 billion of assumed debt.

The structure tells you what each side believed was valuable. T-Mobile wasn’t buying “a regional carrier” as much as it was buying components it could plug into a national machine: customers, stores, and spectrum that fit its network roadmap. Under the agreement, T-Mobile would acquire UScellular’s wireless operations and about 30% of its spectrum assets across several bands.

“With this deal T-Mobile can extend the superior Un-carrier value and experiences that we’re famous for to millions of UScellular customers and deliver them lower-priced, value-packed plans and better connectivity on our best-in-class nationwide 5G network,” said Mike Sievert, CEO of T-Mobile.

And what TDS kept was just as revealing. UScellular would retain roughly 70% of its spectrum holdings and all of its approximately 4,400 towers. In other words: the future, as TDS now saw it, wasn’t competing for phone plans. It was owning infrastructure.

Then came the part that can make or break any telecom deal: Washington. The regulatory review moved faster than many expected given the transaction’s scope and the obvious headline—one less meaningful competitor in a number of local markets. Still, the Department of Justice cleared the transaction. “UScellular simply could not keep up,” said Assistant Attorney General Gail Slater. “Consumers would benefit from a stronger T-Mobile.”

That was the government saying the quiet part out loud: UScellular was already being beaten. Blocking the deal wouldn’t preserve competition; it would just preserve a slow decline.

After closing, T-Mobile made the victory lap: it had acquired substantially all of UScellular’s wireless operations, putting more than four million UScellular customers on a path to T-Mobile’s national network. Final economics shifted slightly with closing adjustments. T-Mobile acquired the wireless business and specified spectrum assets for an aggregate purchase price of approximately $4.3 billion after adjustments, consisting of $2.6 billion paid in cash and approximately $1.7 billion in debt to be assumed.

“The closing of the sale of UScellular’s wireless operations and certain spectrum assets to T-Mobile marks an important milestone in the Company’s 42-year history,” said Walter Carlson, TDS President and CEO. “The successful completion of this transaction has delivered significant shareholder value and has positioned the continuing Array business with a strong balance sheet and a tower infrastructure business poised for growth and value creation.”

The “continuing” company wasn’t just smaller. It was fundamentally different. On July 24, 2025, UScellular announced that once the sale closed—expected on August 1, 2025—it would change its name to Array Digital Infrastructure, Inc. The rebrand wasn’t cosmetic. It was an admission that the identity of “UScellular the carrier” was being retired, replaced by something more defensible on paper: towers and spectrum, not retail stores and churn.

For the Carlson family, it marked the end of a decades-long chapter in American wireless. “As we progress through the divestiture of the wireless operations, we are pleased to take these next steps in announcing leadership as well as the new legal name, Array Digital Infrastructure, Inc., of the post-closing company,” said LeRoy T. Carlson, Jr., board chair.

And once you reach this point in the story, the counterfactual becomes impossible to ignore. What if TDS had sold UScellular earlier—when the subscriber base was still growing and regional wireless still had buyers willing to pay for “option value”? What if they had sold in 2008, near the high-water mark? Or in 2013, when consolidation was accelerating and the market still believed there were multiple winners left?

We can’t run the alternate timeline. But we can see the arc. Every year TDS waited, UScellular’s bargaining power weakened: more capex required, fewer subscribers to spread it across, and more reasons for customers to defect. By the time the company finally raised its hand, the deal wasn’t a trophy. It was a necessary landing.

VIII. TDS Telecom: The Quiet Survivor

While UScellular’s decline consumed investor attention and management oxygen, the other half of the house kept building. TDS Telecom — the original, less glamorous business — was quietly remaking itself into something that could actually thrive in a post-regional-wireless world.

At a basic level, TDS Telecom does what it always has: it brings internet, TV, and phone service to communities that are small to mid-sized, often suburban or rural, and frequently ignored until someone makes a point of showing up. Today it serves about 1.1 million connections across the U.S., and it frames its mission in the same spirit the company was founded on: use communications services to make life better in places the big players don’t prioritize. The difference is the technology. This is no longer a copper story. It’s fiber — with advertised speeds up to 8 Gig.

And that shift isn’t incidental. It’s the strategy. The fiber build is, in many ways, TDS returning to its roots: invest in underserved markets, upgrade the infrastructure, and win through presence and service — just updated for the era where “a phone line” has become “a high-capacity data pipe.”

“We’ve been transforming into a fiber company in a big way for several years,” said Bothfeld.

By the time TDS Telecom updated investors during its fourth-quarter earnings report, the ambition had gotten bigger. The company raised its long-term target to 1.8 million marketable fiber service addresses — a 50% increase from the prior goal — and it ended the year at 928,000 total fiber service addresses.

The reason this can work — even in rural America — is that the economics of fiber are meaningfully different from the economics of rural wireless. Wireless is a perpetual arms race: new generations, new spectrum bands, new radios, new towers, over and over. Fiber is expensive upfront, but once it’s in the ground, it doesn’t become obsolete every few years. The upgrades are often electronics on either end, not ripping out the whole network. Customers also tend to stick. Switching a broadband provider usually means scheduling an install, letting someone into your home, and risking downtime — a very different experience than porting a phone number and swapping a SIM.

In many of TDS Telecom’s markets, there’s also a simple reality: very few companies are willing to spend real money to build modern infrastructure there. That reluctance creates openings that don’t exist in wireless.

The company’s updated goals reflect how far it wants to push that advantage. It now aims to have fiber available to 80% of its marketable service addresses, up from a prior goal of 60%. It ended the year at 52%. It also targeted having 95% of its footprint capable of at least 1 Gig speeds, and it finished the year at 74%.

Subsidies matter here, too — not as a nice-to-have, but as a piece of the economic puzzle that makes the hardest geographies pencil out. “With the E-ACAM program,” said Bothfeld, “we will receive approximately $90 million of annual regulatory revenue for 15 years in exchange for bringing higher speeds to some of the most rural geographies in our footprint.”

And, crucially, the operating results have started to validate the pivot. In 2024, TDS Telecom increased residential revenues by 6% as both broadband connections and average revenue per connection grew. That growth was driven by fiber-market investment. Combined with cost discipline, it helped drive a 23% year-over-year increase in adjusted EBITDA.

Then there’s one more twist — and it’s a sign of how much the industry lines have blurred. TDS Telecom is launching its own mobile offering, TDS Mobile, using AT&T’s network as an MVNO. “During 2025, we intend to fully launch TDS Mobile across our entire footprint. We believe that adding mobile to our product portfolio is complementary to our broadband offering and enables us to offer a full suite of competitive products and services to our customers.”

In other words: after spending decades trying to win wireless by owning the network, TDS is now approaching mobile the way cable did — sell the service, rent the infrastructure, bundle it with broadband, and focus on customer relationships.

In many ways, the moat here is more defensible than anything UScellular could claim in its final decade. In rural markets, it’s hard to justify multiple fiber builds. Once TDS runs fiber down your street, a competitor has to believe it can spend millions to overbuild and still win enough customers to earn an acceptable return. That’s a very different dynamic than wireless, where national carriers can compete everywhere simply because their customers roam everywhere.

But it’s not a victory parade, either. Real threats are gathering. Fixed wireless access from T-Mobile and Verizon can deliver “good enough” broadband without laying cable, and it’s improving quickly. Starlink and other satellite networks can reach places where fiber will never make sense. So the question for TDS Telecom isn’t whether fiber is better — it is, on latency, reliability, and symmetrical speeds. The question is whether “better” stays worth paying for as the wireless alternatives get cheaper, easier, and more ubiquitous.

IX. The Carlson Family & Governance: Visionaries or Stubborn?

At TDS, you can’t talk about strategy without talking about control. The biggest governance question is also the biggest business question: over the company’s fifty-four-year run, did family control protect long-term value… or postpone the inevitable and punish shareholders?

On paper, the setup is straightforward. The Board has twelve members. Holders of Common Shares elect 25% of the directors, rounded up, plus one additional director—four directors total on a twelve-person board. Holders of Series A Common Shares elect the remaining eight.

In practice, that means the Carlson family controls board elections while owning only a minority of the economic interest. To governance critics, that’s the definition of entrenchment: a structure that insulates leadership from outside pressure even when performance deteriorates. But it’s also the mechanism that let TDS behave differently from the rest of the industry. The company could make long-horizon bets—like the fiber build at TDS Telecom, or the post-sale reshaping of UScellular into what became Array Digital Infrastructure—without having to win a quarterly popularity contest.

The problem is the flip side. When you’re insulated from market discipline, it’s easier to stay the course long after the course stops working. And that’s the accusation here: that the family held onto UScellular years longer than was economically rational, and that shareholders paid the price. By the time the company finally agreed to sell in 2024 for $4.4 billion, it was hard not to wonder what that same asset package might have fetched a decade earlier.

The leadership handoff in 2025 underscored how tightly governance and continuity are woven together at TDS. The company announced that effective February 1, 2025, Walter C. D. Carlson would succeed LeRoy (“Ted”) T. Carlson, Jr. as TDS President and Chief Executive Officer, with Ted Carlson moving into a newly created Vice Chair role focused on enterprise strategy.

Walter Carlson’s background was not the classic telecom-operator path. Before becoming CEO, he spent more than 44 years at Sidley Austin LLP, including 37 years as a partner. He was a nationally recognized securities litigator who led teams across major matters for clients. He earned his bachelor’s degree from Yale and a J.D. from Harvard Law School.

Zooming out, TDS isn’t alone here. Other family-controlled telecom and media empires—like the Roberts family at Comcast, or the Dolans at Cablevision (now split across AMC Networks and MSG)—show the same trade-off: family vision can enable long-term thinking, but it can also weaken shareholder accountability. There isn’t a universally “right” model. Outcomes depend less on the paperwork and more on what the people in control choose to do with it.

The Carlson family’s “serve communities” mission was real, and it mattered to the towns TDS built for. But mission can also become a shield—an argument for maintaining control even when the economics have shifted and the best decision for shareholders might be to exit.

One thing is hard to dispute: the dual-class structure delayed the day of reckoning. Any buyer couldn’t just persuade public shareholders; they’d have to negotiate with the Carlsons, whose voting power exceeded their economic stake. That gave the family something immensely valuable—choice. They could decide if and when to sell. But that same choice also reduced the forcing function that might have driven a sale earlier, when UScellular’s leverage and valuation were stronger.

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The TDS and UScellular saga leaves a set of lessons that show up again and again in infrastructure businesses—whether you’re looking at telecom, utilities, rail, pipelines, or anything else where the product is a network and the bill is perpetual.

Scale matters in infrastructure businesses—eventually, fatally. UScellular’s regional strategy worked for years because the advantages were local: relationships, retail presence, and a network that could be excellent within a defined footprint. But the smartphone era changed what customers were buying. “Great in my town” stopped being enough; the baseline became “works everywhere, fast.” Once the job becomes funding nationwide-grade technology on a regional customer base, the math turns. A smaller carrier can be well-run and still be structurally outgunned.

Spectrum as moat—until it isn’t. UScellular did the hard work for decades: showing up to auctions, accumulating licenses, and building a valuable spectrum portfolio. In the 2G and 3G years, that really was a moat. But spectrum isn’t a finished product—it’s raw material. If you don’t have the capital and scale to deploy it quickly and fully, it starts to behave less like an advantage and more like a stranded asset. In the end, much of what UScellular owned was simply worth more in the hands of a national carrier that could put it to work across a far larger base.

The rural strategy paradox. TDS’s mission—serve the communities others ignore—was real, and it created a culture customers could feel. But rural markets come with stubborn physics: fewer people, farther apart, and higher costs per customer. That’s manageable when technology upgrades are incremental. It becomes punishing when the industry shifts into massive, repeated rebuilds like LTE and 5G. The very strategy that built trust and differentiation also narrowed the company’s strategic exits when the capital demands exploded.

Family control cuts both ways. The Carlson control structure bought TDS something valuable: time. It let the company invest on long horizons, avoid being pushed around by quarterly sentiment, and stay focused on stewardship. But that same insulation also reduced the forcing function to change course when the evidence turned. Family control isn’t automatically good or bad. It’s leverage—amplifying the quality of the decisions made by the people holding it.

Consolidation is often inevitable. TDS chose not to sell during the 2013–2018 consolidation wave, implicitly betting that a well-run regional carrier could compete indefinitely against national scale. That bet didn’t pay off. In industries with real scale economies, consolidation isn’t an event—it’s gravity. You can fight gravity, but you usually need extraordinary execution, favorable regulation, or a genuine structural edge. Otherwise, the best move is often to sell while you still have leverage, not after it’s gone.

Hidden assets can emerge. For years, UScellular was the headline and TDS Telecom was the understudy. Then the wireless business entered a long squeeze, and the wireline side—especially fiber—started to look like the more durable engine. The investing lesson is simple: conglomerates and holding companies can hide optionality. The segment everyone talks about isn’t always the one that ends up carrying the future.

The capex treadmill never stops. Telecom is a business where standing still is falling behind. Every generation brings new spectrum bands, new radios, new equipment, and new expectations—often without a matching ability to raise prices. If you can’t keep pace, you don’t just lose a feature comparison. You lose customers, which makes it even harder to fund the next round. It’s a compounding problem.

Knowing when to sell. This is the hardest one, because it’s not about running the business well—it’s about reading the industry’s direction and acting before the window closes. With hindsight, the best time to sell UScellular was likely when subscriber growth was still healthy and “regional wireless” still looked like a stable category—roughly the late 2000s into the early 2010s. Each year after that made the buyer universe smaller, the negotiating leverage weaker, and the outcome more defensive. The key question for boards isn’t “Are conditions perfect?” They almost never are. It’s “Are conditions more likely to get better from here—or worse?”

XI. Analysis Framework: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

One way to make sense of what happened here is to step back from the timeline and ask a colder question: structurally, what kind of game was UScellular playing? And did it ever have a durable way to win?

That’s where two classic strategy lenses help: Porter’s 5 Forces (what pressures your industry puts on you) and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers (what, if anything, gives you an enduring edge).

Porter's 5 Forces for UScellular (Pre-Sale):

Threat of New Entrants: LOW to MEDIUM. Building a wireless carrier the “traditional” way is brutally hard: you need spectrum licenses, you need to build a network, and you need regulatory permission. Those are real barriers. But cable companies found a loophole that mattered: MVNOs. By leasing capacity from national carriers, they entered wireless without building towers or buying spectrum. It wasn’t new entry in the classic sense, but it had the same effect on the market—and it hit regional carriers especially hard.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM. The radio access network supply chain is concentrated, with the major players being Ericsson, Nokia, and Samsung. That limits leverage on pricing and terms. Then there are tower companies—owners of the physical sites and leases—that often have pricing power of their own. In both cases, there isn’t much competition you can play off to get a better deal.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH. For customers, switching has gotten easy. Number portability removed the biggest psychological lock-in, and the industry trained consumers to shop plans like any other commodity—helped along by relentless promotions. Meanwhile, national carriers can bundle, discount, and cross-subsidize in ways a regional carrier can’t.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH and increasing. WiFi calling reduces dependence on cellular coverage. Messaging apps eat voice and SMS. Fixed wireless access offers an alternative for home broadband. Every one of these substitutes chips away at how “must-have” traditional carrier service feels, and how much pricing power any one carrier can hold.

Competitive Rivalry: EXTREME. UScellular was fighting three national carriers with far more customers, deeper balance sheets, and stronger spectrum positions—and then cable MVNOs showed up with lower costs and aggressive pricing. Wireless has high fixed costs, limited differentiation, and promotion-heavy competition. That combination tends to produce the kind of rivalry where smaller players don’t slowly lose. They eventually get squeezed out.

Porter's 5 Forces for TDS Telecom (Current):

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-LOW. Building fiber is expensive, slow, and usually irrational to duplicate once someone has already done it. That naturally limits direct overbuilding. But the “new entrant” risk comes from different technology, not a second fiber operator: fixed wireless access and satellite networks like Starlink can show up without digging trenches.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM. TDS Telecom has more sourcing flexibility than wireless did—more vendors and less reliance on a tiny set of RAN suppliers. But labor and construction capacity become the choke points here, and those costs can swing meaningfully.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM. In many rural markets, customers still have fewer real choices than in cities, which dampens churn. But FWA and satellite options are expanding, and every viable alternative increases customer leverage.

Threat of Substitutes: GROWING. Fixed wireless access from T-Mobile and Verizon can deliver broadband without a fiber build. Starlink can serve places fiber may never reach. These aren’t perfect substitutes for fiber, but they don’t have to be. They just have to be good enough for enough households to pressure pricing and take share.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM. There are local and regional fiber competitors in some areas, and cable overlaps in parts of the footprint. But it’s still a calmer battlefield than wireless—especially in the rural markets where economics often support one primary wired infrastructure provider.

Hamilton's 7 Powers (UScellular Analysis):

-

Scale Economies: ABSENT. This is the heart of it. UScellular had real regional scale, but it was tiny compared to national carriers. Once wireless became a data-and-upgrade business, the minimum efficient scale rose beyond what a regional carrier could realistically reach. The missing Power here wasn’t a weakness—it was fatal.

-

Network Effects: NOT APPLICABLE. Your experience with a carrier doesn’t materially improve because more people use the same carrier.

-

Counter-Positioning: FAILED. “Better service” was a real differentiator in the voice era and early smartphone era, and it helped justify a modest premium in core markets. But as coverage expectations went national and price competition intensified, customer service alone couldn’t offset network footprint and promotional firepower.

-

Switching Costs: WEAK. Number portability removed the biggest barrier. Contracts once provided friction, but installment plans and bring-your-own-device offers made switching easier over time, not harder.

-

Branding: MODERATE. UScellular earned genuine loyalty in its best markets. But the brand couldn’t command a large enough premium to overcome structural disadvantages, and its pull weakened as wireless became more commoditized.

-

Cornered Resource: PARTIAL. Spectrum is finite, and UScellular owned valuable licenses. But the national carriers had more of it, often better suited to the 5G era, and they could deploy it more efficiently across a far larger base. UScellular’s spectrum was real value—just not enough to function as an enduring moat.

-

Process Power: INSUFFICIENT. UScellular’s customer service culture was real and operationally meaningful. It just wasn’t the kind of advantage that survives when the competitive gap is driven by capital intensity and scale.

Key Insight: UScellular didn’t lack effort, competence, or even assets. It lacked durable Power that matched what the industry started rewarding. When the smartphone era arrived, wireless became a scale game. And in a scale game, “regional excellence” turns into “structural disadvantage.”

Hamilton's 7 Powers (TDS Telecom Analysis):

-

Scale Economies: LOCAL. Fiber has a different kind of scale advantage: once you’ve built the network in a town, your costs and economics tend to discourage a second build. That’s not national scale, but it can be defensible market by market.

-

Network Effects: NOT APPLICABLE.

-

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE. TDS Telecom often builds where incumbents won’t—especially in smaller communities where big players don’t want to spend. That creates a window of opportunity, and sometimes a lasting position, precisely because others choose not to compete.

-

Switching Costs: MODERATE. Switching broadband is more painful than switching mobile: installs, tech visits, and the risk of downtime. Once someone has working fiber, they tend not to churn back to worse options unless there’s a compelling reason.

-

Branding: WEAK. Broadband is still largely a utility. Customers care most about speed, reliability, and price.

-

Cornered Resource: NONE. Rights-of-way aren’t truly exclusive. If a competitor wants to invest, they usually can.

-

Process Power: MODERATE. There’s real know-how in building and operating networks in small towns—permitting, construction, customer service, maintenance. That operational competence can be hard for urban-focused competitors to replicate quickly.

TDS Telecom’s profile is meaningfully better than UScellular’s was at the end—but it’s still not a fortress. The open question is whether local fiber advantages and “go where others won’t” counter-positioning can hold up as fixed wireless and satellite keep improving.

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case (Post-UScellular Sale)

Bull Case:

Clean balance sheet post-sale. The roughly $4.3 billion in proceeds from the T-Mobile transaction gives TDS something it hasn’t had in years: room to breathe. That capital can go to paying down debt, returning value to shareholders through dividends, and funding more fiber builds. Most importantly, it restores flexibility—options that weren’t available when wireless capex was eating the budget.

TDS Telecom has runway. There’s still a real multi-year opportunity in bringing modern broadband to underserved communities. TDS Telecom has spent years building the muscle for this: permitting, construction, installs, service, and operating in smaller markets without burning cash. The growth won’t look like a viral tech startup, but it can be steady if fiber penetration follows the builds.

Rural broadband subsidies. Programs like RDOF, BEAD, and E-ACAM help make the toughest geographies pencil out. Under E-ACAM, TDS expects to receive about $90 million per year for 15 years in exchange for bringing higher speeds to some of the most rural parts of its footprint. Subsidies don’t replace a business model, but they can accelerate one—and improve early returns while the network fills up.

Less competition in rural fiber than urban/suburban markets. Big carriers and cable operators generally chase density, because density drives returns. TDS Telecom operates where that density often isn’t there, which can mean fewer deep-pocketed competitors willing to overbuild. In a lot of small towns, the real competition is “old and slow” rather than “new and aggressive.”

Tower assets retain value. Array Digital owned 4,449 towers at the end of the third quarter. Towers are the kind of infrastructure investors usually like: recurring revenue, contractual escalators, and long-lived assets. The T-Mobile relationship matters here. T-Mobile signed a 15-year Master License Agreement to become a long-term tenant on a minimum of 2,015 incremental towers owned by Array, and to extend the lease term for roughly 600 towers where T-Mobile was already a tenant. That’s visibility—exactly what a tower business sells.

Management focus. For years, leadership had to manage a shrinking wireless business while trying to fund the next upgrade cycle. With that chapter closed, execution can finally get simpler: build fiber where it earns returns, run the network well, and treat towers like the infrastructure business they are.

Dividend sustainability improves. A business no longer trapped in a 5G spending race has a better chance of supporting a stable dividend. If leverage comes down and the fiber plan performs, the dividend story gets easier to defend.

Bear Case:

Fixed wireless access will devastate rural fiber economics. The most direct threat is “good enough” internet that doesn’t require digging a trench. T-Mobile and Verizon can sell home broadband over 5G, and in areas with adequate coverage, the value proposition is obvious: fast install, competitive pricing, and no construction timeline. If enough households decide that fixed wireless is fine, fiber penetration rates could disappoint—and fiber returns depend on penetration.

Starlink and satellite constellations provide true competition everywhere. Starlink changed the satellite conversation. For many rural customers, it’s not a last resort anymore—it’s a real alternative. And rural is exactly where Starlink looks strongest, which puts pressure right on TDS Telecom’s core footprint.

TDS Telecom doesn't have enough scale. One lesson from UScellular is that scale disadvantages don’t always stay contained to one segment. Even in wireline, bigger competitors can spread costs across more customers, invest more aggressively, and buy attractive assets. If consolidation accelerates in fiber, TDS risks being left with the hardest, lowest-return territories.

Government subsidies are one-time. Subsidies can make a build possible, but they don’t last forever. The worry isn’t the next few years—it’s what happens later. When the support rolls off, do the most rural markets still support reinvestment, maintenance, and upgrades at acceptable returns?

The company sold its best asset. If you believe spectrum and wireless customers were the long-term growth engine, then selling UScellular looks like cashing out the upside and keeping the slow-and-steady business. Fiber in small towns can be durable, but it may never offer the same optionality that spectrum does in a tech cycle.

Carlson family still controls company. The governance structure didn’t disappear with the wireless sale. If family control contributed to waiting too long to act at UScellular, the same question hangs over the post-sale company: when hard decisions show up again, will they get made on time?

Without UScellular, TDS is too small, too regional, and lacks strategic rationale. As a rural fiber-and-tower story, TDS may not fit cleanly into what most investors look for. That can mean a persistent valuation discount—not necessarily because the assets are bad, but because the narrative is harder to place.

Critical KPIs to Monitor:

For investors tracking TDS going forward, two metrics matter most:

-

Fiber broadband net adds and penetration rates: This tells you whether TDS Telecom is turning fiber passings into paying customers at rates that justify the build cost. If net adds turn negative or penetration stalls, it’s a warning sign that fixed wireless access or satellite is displacing demand.

-

Tower co-location and amendment activity at Array Digital: Towers are worth more when more tenants and more equipment show up. As management put it, in the first half of 2025, colo applications increased by more than 100% versus the first half of 2024: “It’s back to this rural edgeout that carriers are engaged in. We’re a big part of that, and we’re seeing very robust colo apps.” If that activity holds, it supports the idea that Array’s towers sit in the flow of continued rural network buildouts.

XIII. Epilogue: What Could Have Been & What Happens Next

The alternate history is hard to resist. If TDS had sold UScellular to AT&T or Verizon sometime around 2008 to 2010—when subscribers were near their peak, and before smartphones fully rewired wireless economics—the price tag might have been north of $10 billion. The Carlson family would have cashed in their wireless bet at exactly the moment the market still rewarded “regional scale” as a strategic asset.

Instead, they held on. Through the iPhone shockwave. Through the LTE rebuild. Through the consolidation years when peers took deals. Through the 5G cycle that demanded more capital than a regional footprint could comfortably support. And with every year that passed, UScellular’s leverage eroded: fewer customers to spread the cost across, more reasons for customers to switch, and a buyer universe that cared less about “a carrier” and more about parts—spectrum, towers, and whatever could be snapped into a national network.

So was this mistake or misfortune?

Probably some of both. The Carlson family’s mission—serving communities others ignored—was real. So was their belief that a regional operator could keep competing if it executed well enough. They may have been wrong, but they weren’t acting in bad faith. And the same dual-class structure that protected long-term thinking also protected them from the market’s clearest message: sell while you still have bargaining power.

For other regional infrastructure companies staring down consolidation, the lesson is sobering. Markets are usually right about industry structure, even when they’re early on timing. Fighting consolidation demands extraordinary execution, favorable regulation, and more luck than most teams get. Sometimes the best move isn’t to outfight the trend—it’s to recognize the moment the game changed and exit before the war of attrition starts writing your valuation down quarter by quarter.

Then there are the human and community questions. What happens to UScellular employees, retail stores, and the “local” brand after T-Mobile takes over? The UScellular name will be phased out as customers and operations migrate onto T-Mobile. Meanwhile, Array Digital Infrastructure Inc. (formerly UScellular) continues as a separate, infrastructure-focused company—still owning a meaningful tower footprint and retaining a significant portion of the spectrum it didn’t sell.

That leaves the post-sale TDS betting on two businesses that are steadier than wireless, but also more modest: TDS Telecom’s fiber operations and Array’s tower portfolio. TDS Telecom serves about 1.1 million connections. Array operates more than 4,400 towers. Neither is a rocket ship. But both provide essential infrastructure, and both can throw off real cash if managed well.

From here, there are a few plausible paths. TDS could pursue fiber roll-ups, buying smaller rural broadband providers to build scale. It could become the target—exactly the kind of rural infrastructure platform a larger strategic buyer or infrastructure investor might want. Or it could drift toward a slower, more financial end state: running mature assets for cash and returning capital over time.

And zooming out, there’s the bigger marker in the sand: the end of regional wireless in America. UScellular was the last significant independent regional carrier to fall. As Blair Levin of New Street Research put it, the company’s days as a viable competitive force were effectively over—and the most likely endgame for other would-be challengers is asset monetization, not a sustained fourth national network. “Their pricing was higher than the big three. The most likely outcome is EchoStar [Dish] selling spectrum to the big three.”

Which raises the uncomfortable policy question: is rural America better or worse off with only three national carriers? The DOJ’s view was clear—consumers benefit more from a stronger T-Mobile than from preserving a weakened UScellular that “simply could not keep up.” But consolidation also means less competitive pressure, and the long-run impact on pricing and service quality in rural markets isn’t something any press release can settle.

In the end, TDS is a case study in disruption, governance, and the limits of independence. LeRoy T. Carlson built something rare: a company with a real mission, a real service culture, and a half-century legacy of showing up where others wouldn’t.

But mission doesn’t repeal math. Independent regional wireless eventually collided with data-heavy networks and national scale economies—and lost. By the time TDS finally sold, it wasn’t choosing the best possible outcome. It was choosing the viable one.

What’s left is a smaller company with a cleaner balance sheet and a more focused mission. In a strange way, TDS in 2025 echoes TDS in 1969: a family-controlled operator trying to bring modern connectivity to underserved communities—now with fiber instead of copper, and towers instead of retail stores. Whether that mission proves more durable this time is the next chapter.

The story continues.

XIV. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper on how TDS got here—and what the telecom industry’s economics look like when you zoom out—these are the best places to start:

-

TDS Annual Reports & Investor Presentations (2005-2024) – The cleanest record of the company’s strategy shifts, capital allocation, and how the story evolved in its own words.

-

FCC Spectrum Auction Results & Analysis – A window into the real competitive battlefield: who won, who got priced out, and why spectrum became the constraint that scaled players could exploit.

-

"The Master Switch" by Tim Wu – The broader historical cycle that TDS ran into: how communications industries repeatedly consolidate, and why that gravity is hard to fight.

-

UScellular Sale Announcement & T-Mobile Deal Documents (2024) – The primary sources for what was actually sold, what was kept, and how the transaction was structured and reviewed.

-

MoffettNathanson Telecom Research Reports – Some of the clearest thinking on wireless economics, capex cycles, and why “scale” in mobile isn’t just an advantage—it’s often destiny.

-

Rural Broadband Policy Papers (Benton Institute, FCC) – The policy backdrop for TDS Telecom: subsidies, rural build economics, and the government’s role in who gets connected and how.

-

Harvard Business Review: "When Family Businesses Are Best—and Worst" – A strong framework for the Carlson-family governance trade-off: stewardship versus entrenchment.

-

Recon Analytics/Wave7 Research on Regional Carriers – Data-heavy tracking of the regional carrier decline, and how quickly “Tier 2” wireless became a shrinking category.

-

Array Digital Infrastructure Investor Presentations – How the post-sale company explains itself: towers, tenants, spectrum, and what “infrastructure-first” looks like after you stop being a carrier.

-

Wireless History Foundation Hall of Fame Materials – Helpful biographical context on LeRoy T. Carlson and the founding generation that shaped the culture and the mission from the start.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music