SunCoke Energy: The Hidden Infrastructure Behind American Steel

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

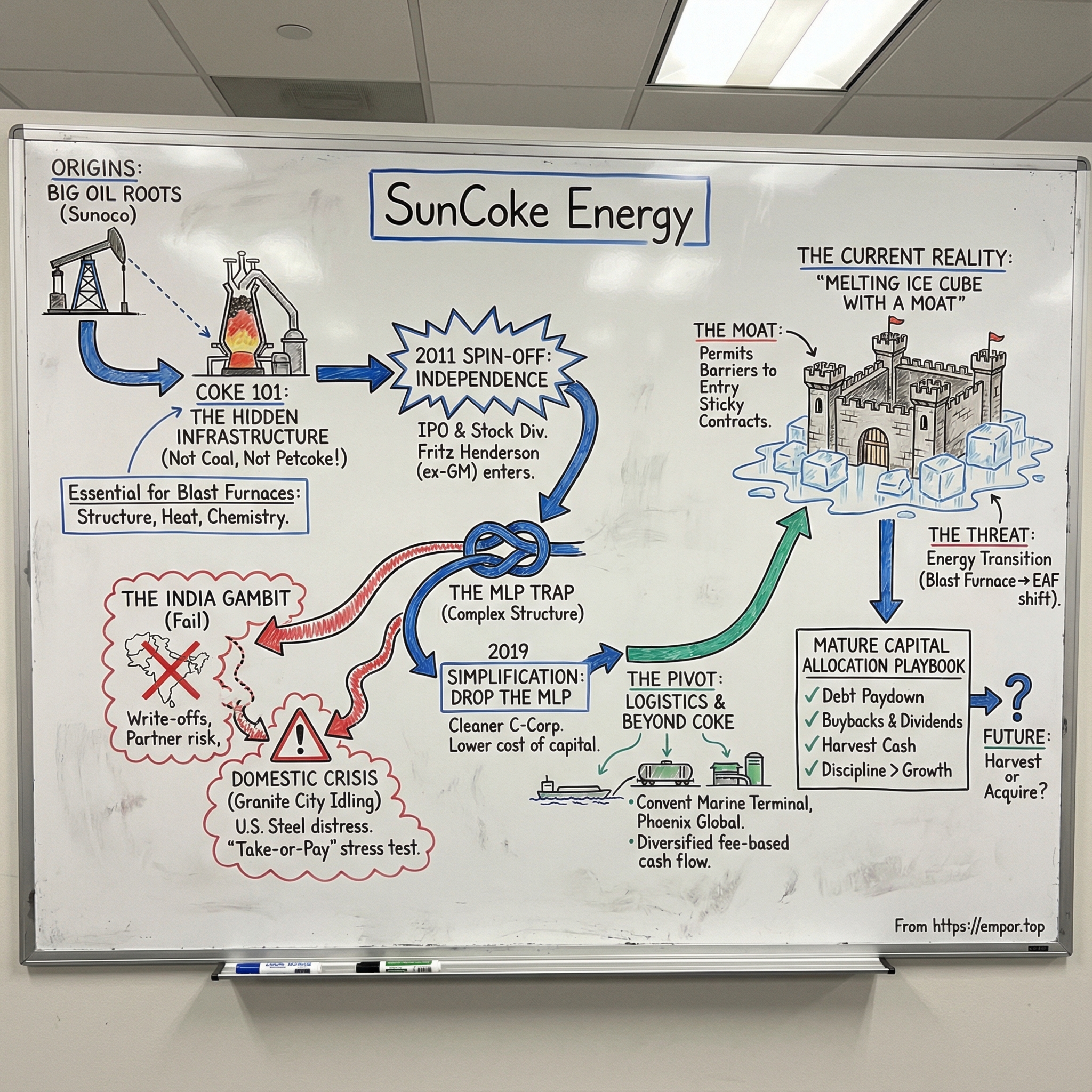

Picture a blast furnace complex at full tilt: heat shimmering, steelworkers in hard hats, and an orange glow that never really goes away. Inside, at roughly 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, coal is baked into something far more valuable than fuel. Not coal. Not petroleum coke. Metallurgical coke—almost pure carbon—built for one job: making blast furnaces work. Without it, a huge chunk of the physical world around you—bridges, rebar, rail, cars, appliances—doesn’t get made.

And in North America, one company sits at the center of that supply chain: SunCoke Energy. SunCoke is the largest independent producer of high-quality coke in the Americas by annual production, with more than 60 years of experience. It supplies about 4.2 million tons a year to leading integrated steelmakers, running cokemaking facilities across Virginia, Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois, plus an international operation in Vitória, Brazil.

What makes SunCoke worth an entire episode isn’t that coke is obscure. It’s that the company’s path is a perfect case study in industrial survival. How does a century-old, heavily regulated process—once tucked inside a much larger oil company—get spun into a standalone public business, live through the near-collapse of American steel, stumble into a painful international expansion, unwind a complicated corporate structure, and then build a second act in logistics… all while the energy transition rewrites the rules for anything even adjacent to coal?

The punchline is: this isn’t a zombie company limping along. In 2024, SunCoke generated $1.94 billion in revenue and $272.8 million in consolidated Adjusted EBITDA. Revenue was down year over year, but net income rose to $95.9 million. Those are the results of a business that learned how to run a mature, cyclical industry for cash—while staying realistic about what “long term” means when your customers are steadily shifting away from blast furnaces.

So this story is about spin-offs—when they unlock value, and when they simply ring-fence risk. It’s about commodity cycles and the unforgiving math of steel. It’s about the kind of infrastructure moat that doesn’t look like a moat until you try to build a new plant and realize you basically can’t. And it’s about what happens when an essential industrial input becomes politically, environmentally, and financially complicated.

If you’re an investor, SunCoke is a live case study in capital allocation inside a “melting ice cube.” If you’re a strategist, it’s a masterclass in staying upright through multiple existential threats. Let’s dig in.

II. Coke 101: The Unsung Hero of Steelmaking

Before we get into SunCoke’s corporate twists and turns, we have to get clear on the product. Metallurgical coke isn’t coal. It isn’t petroleum coke. And it isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s one of the few truly irreplaceable ingredients in traditional steelmaking.

Here’s the basic trick. You take metallurgical coal and bake it in massive, purpose-built ovens at temperatures above 2,000°F, for roughly a couple of days, without oxygen. With no oxygen available, the coal can’t burn the normal way. Instead, it cooks. The volatile stuff—oils, tars, and a bunch of other compounds—gets driven off, and what you’re left with is coke: a carbon-rich material that’s hard, porous, and strong.

That “porous and strong” part is the whole game.

Coke then gets delivered to an integrated steel mill and fed into a blast furnace along with iron ore and limestone. From there, it plays three jobs at once.

First, it’s chemistry. Coke creates carbon monoxide, which strips oxygen from iron ore and turns iron oxide into metallic iron.

Second, it’s energy. Coke is what enables the furnace to reach the extreme temperatures needed to melt and transform the material.

Third—and this is the one people miss—it’s structure. A blast furnace is a towering counterflow reactor: solids go in at the top, hot gases rise from the bottom, and molten iron drains down through the middle. Coke has to hold up under crushing weight and brutal heat while still letting gases flow through. If the coke breaks down, the furnace doesn’t just run less efficiently. It can seize up.

So when SunCoke calls itself “infrastructure,” this is what they mean. Coke isn’t a commodity you can casually swap out. It’s engineered for a particular furnace, a particular ore blend, and a particular operating rhythm.

That reality shapes the business economics. Coke plants are enormous, expensive, and slow to build—projects measured in years, not quarters. And once you’ve built one, you need predictable demand to justify it. That’s why the industry runs on long-term, take-or-pay contracts. Steelmakers commit to buying set volumes over long stretches—often a decade or more—and if they don’t take the coke, they still pay for it. SunCoke also structures many of these agreements to pass through commodity and certain operating costs, so the company isn’t forced to eat every swing in coal prices or other inputs.

Those contracts are the backbone of stability—and the source of the biggest risk. If your steel customer is healthy, take-or-pay is a fortress. If your steel customer blows up, the contract can become a piece of paper with no one left to honor it.

Then there’s the other barrier: the air.

Cokemaking is among the most heavily regulated industrial processes in America, for good reason. It can produce significant emissions, and communities near plants have long raised health concerns. In Granite City, for example, pollution from the local facility has been linked by researchers to serious public health impacts, including premature deaths and thousands of asthma symptoms annually. Whatever the exact number, the takeaway is simple: permitting a brand-new coke facility in the U.S. is extraordinarily difficult today. That means the plants that already exist—grandfathered, upgraded, and monitored—have something like a regulatory moat around them.

SunCoke also leans into a technical edge with its heat-recovery cokemaking technology. Instead of treating the intense heat and off-gases as pure waste, the system captures thermal energy and uses it to generate steam or electricity. It’s still a heavy industrial process, but it can be more efficient, and it can reduce certain environmental impacts relative to older designs.

And this is why coke matters to the SunCoke story—and why SunCoke matters to steel. As long as blast furnaces keep running, coke remains non-negotiable. There’s no direct substitute for that combination of chemistry, heat, and physical support. But if steel production keeps shifting toward alternative methods that don’t use blast furnaces, then coke demand doesn’t just soften. It structurally declines.

That tension—essential today, threatened tomorrow—sets up everything that comes next.

III. The Sunoco Years: Origins in Big Oil

SunCoke’s roots run back more than a century, to a version of industrial America that looks almost alien today. Steel wasn’t a set of contractors linked by purchase orders. It was empires—ore, coal, rail, coke, blast furnaces, all under one roof. And if you want to understand why SunCoke’s business looks the way it does—capital-heavy, contract-driven, and built around a handful of giant customers—you have to start there.

In the early 1900s, the cokemaking operations that would eventually roll up into SunCoke lived inside integrated steel producers. U.S. Steel, Bethlehem Steel, and their peers didn’t just buy inputs; they owned them. Vertical integration wasn’t a buzzword. It was insurance. Control the coal and the coke, and you reduce the odds that a supply shock shuts down the furnace and strands your most expensive asset.

So how did coke plants end up inside an oil company?

That’s the twist that takes you into the conglomerate era, when big industrial firms accumulated businesses that were adjacent… and sometimes just available. Over decades of acquisitions and divestitures, Sunoco ended up owning cokemaking assets that produced steady cash but didn’t fit cleanly with the company’s transportation fuels and refining focus. There’s a surface-level logic—both refining and cokemaking are complex, high-temperature, process-heavy operations—but strategically, the overlap was thin. Different customers. Different economics. Different regulatory and community dynamics. Not much synergy beyond “we know how to run big industrial equipment.”

By June 2010, Sunoco said it planned to break off its cokemaking unit—SunCoke Energy—in early 2011. At the time, the unit had facilities in Virginia, Indiana, Ohio, and Illinois capable of producing about 3.7 million tons annually, and it also operated a facility in Brazil producing about 1.7 million tons annually. In 2009, the business earned $180 million on $1.12 billion in revenue. In other words: this wasn’t a side hobby. It was a real, cash-generating industrial platform sitting inside a company that wanted to be something else.

Sunoco’s stated rationale was straightforward: SunCoke’s cokemaking business was separate and distinct from Sunoco’s transportation fuels business, with different customers, different business models, and no meaningful integration. Spinning it out would let each company focus—Sunoco on fuels and refining, and SunCoke on serving steelmakers—while giving the coke business direct access to public capital markets to fund its own plans.

That’s classic spin-off logic. The “strategic orphan” problem. Too small and too different to be central to the parent’s narrative, but too valuable to toss away. A spin creates a clean box around the business—its risks, its cash flows, and its capital needs—and hands it to investors who actually want that box.

And by the time Sunoco made that decision, SunCoke already looked like a company in motion, not a bundle of aging assets. The buildout had been steady and deliberate. In 1998, SunCoke implemented heat-recovery technology at a new facility in East Chicago, Indiana. In 2005, the first phase of the Haverhill heat-recovery plant opened in Franklin Furnace, Ohio, followed by a second phase completed in 2008. In 2007, SunCoke opened its first international heat-recovery facility in Vitória, Brazil. And in 2009, it brought online a new heat-recovery cokemaking facility in Granite City, Illinois.

Each of these projects was the same bet, repeated: spend heavily up front, build for a specific customer, then lock in demand through long-term contracts. That’s how cokemaking works when it works.

It’s also how the future crises got planted, years in advance. Granite City—built to serve U.S. Steel—would later become the epicenter of SunCoke’s biggest domestic shock when the mill idled. And Vitória, Brazil—built with ArcelorMittal—gave SunCoke a taste of international operations that would shape, and then shadow, what came next.

By 2010, SunCoke was already doing more than a billion dollars in revenue and throwing off real profit. The assets were in place. The contracts were signed. The business had gravity.

Now it just needed to stand on its own.

IV. The 2011 Spin-Off: Birth of SunCoke Energy

SunCoke’s spin-out from Sunoco was the first real inflection point in the company’s modern life—and the timing was oddly perfect. The economy was still climbing out of the 2008 crater. Investors were starved for steady income. And “energy infrastructure” was having a moment. On Wall Street, the structure everyone wanted was the Master Limited Partnership, the MLP: a vehicle built to package cash-generating assets into something that looked safe, predictable, and yield-heavy.

SunCoke came to market in two steps. First, Sunoco sold a minority stake: about 20% of SunCoke Energy’s common stock in an IPO that closed on July 21, 2011. Then, on January 17, 2012, Sunoco completed the separation by distributing the rest of its SunCoke shares to Sunoco shareholders in a pro-rata, tax-free special stock dividend. Overnight, SunCoke went from “a business line inside an oil company” to a fully independent, publicly traded company.

Under the hood, the separation was engineered with the same precision SunCoke used to run its ovens. On July 12, 2011, Sunoco borrowed $300 million from an affiliate of one of the IPO underwriters. A couple weeks later, on July 26, SunCoke priced an IPO of 13.34 million shares at $16 per share. When the deal closed, that earlier $300 million borrowing got repaid via a mix of SunCoke stock and cash: 13.34 million shares valued at $213 million, plus $87 million in cash.

Once Sunoco handed out its remaining stake—roughly 80.9% of SunCoke’s outstanding shares—the new company could finally speak in its own voice. “Today marks the completion of the planned separation of SunCoke Energy from Sunoco,” said Frederick A. “Fritz” Henderson, SunCoke’s chairman and CEO. As a standalone company, he argued, SunCoke would have the flexibility to pursue domestic and international growth, serve steel customers more directly, and create opportunities for employees and shareholders.

And that brings us to one of the more surprising casting decisions in this story: Fritz Henderson.

If that name rings a bell, it’s because Henderson wasn’t a coke or steel veteran. He was a General Motors lifer. He joined GM in 1984, worked his way through finance and operations, and eventually became president and CEO on March 31, 2009—replacing Rick Wagoner after Wagoner stepped down at the request of President Barack Obama amid GM’s Chapter 11 reorganization. Henderson’s tenure at the top was short. He resigned as GM CEO on December 1, 2009, replaced by board chair Edward Whitacre, Jr. In early 2010, GM kept him on as a paid consultant for international operations. Later that year, on September 2, 2010, Sunoco announced Henderson would join as a senior vice president and then lead SunCoke as chairman and CEO after the spin.

On paper, the résumé was undeniable: University of Michigan undergrad, Harvard MBA, and decades inside one of the world’s most complex industrial companies—including time as CFO and head of international operations. Sunoco CEO Lynn Elsenhans praised him as “exceptionally gifted,” pointing to the business and financial expertise she believed SunCoke would need as a standalone company with global ambitions. Henderson, for his part, emphasized SunCoke’s position as the leading independent coke producer in North America and talked openly about “significant global growth potential.”

But the skepticism was immediate, and not irrational. Business schools love to debate whether elite executives can parachute across industries and win. Henderson’s critics looked at his short, turbulent run as GM CEO—ending after eight months, with the Obama Administration’s Auto Task Force pushing a debt-laden automaker through Chapter 11—and wondered what exactly that experience would translate into at a highly regulated, contract-heavy, heavy-industrial coke producer.

Regardless of who sat in the corner office, the initial SunCoke investment story was simple and clean. The domestic core was a set of contracted cokemaking facilities—Jewell in Virginia; Indiana Harbor in Indiana; Haverhill in Ohio; Granite City in Illinois; and Middletown in Ohio—supported by an international operation in Brazil that provided diversification and a hint of global capability.

The pitch to public-market investors leaned hard into stability. SunCoke wasn’t a coal miner living and dying by spot pricing. And it wasn’t a steelmaker whose earnings evaporated when demand turned. SunCoke’s take-or-pay contracts aimed to lock in volumes and pricing mechanisms so the company got paid whether the steel cycle was booming or ugly. This was supposed to be infrastructure: essential, contracted, and protected by real barriers to entry.

In 2011, that story landed. Energy infrastructure was fashionable, yield was scarce, and SunCoke offered something rare: a niche industrial business most investors had never studied, with long-lived assets and a narrative that promised steadier cash flows than the brutal steel market it served.

The market would eventually remind everyone that “contracted” doesn’t mean “invincible.” But at birth, SunCoke looked like exactly what Wall Street wanted to buy.

V. The India Gambit: Building Coke Capacity for a Growing Market

Within eighteen months of becoming independent, SunCoke made the kind of big swing that public markets love in good times and punish for years when it goes bad: an expansion into India.

The logic was easy to sell. India’s steel industry was growing fast on the back of infrastructure buildout and urbanization. Coke capacity was hard to add, thanks to environmental scrutiny and the sheer capital required to build modern facilities. And SunCoke’s pitch—heat-recovery technology, operational know-how, and a “cleaner” way to run a notoriously dirty process—seemed tailor-made for a market trying to grow without turning its cities into smoke stacks. If SunCoke could establish itself early, this could be a multi-decade growth platform.

In November 2012, SunCoke and VISA Steel Limited announced agreements to form a cokemaking joint venture in India. SunCoke planned to invest about Rs. 368 crores (about $67 million) for a 49% stake, with VISA Steel holding 51%. The joint venture was expected to be unlevered at closing and was built around an existing asset: VISA Steel’s 400,000-metric-ton-per-year heat-recovery coke plant and associated steam generation units at Kalinganagar in Odisha. The deal was slated to close in early 2013, pending customary conditions, including approval from VISA Steel’s shareholders.

Soon after, the companies officially launched the venture as VISA SunCoke Limited, with co-management and equal representation on the board. Henderson called it a “key milestone” in SunCoke’s international growth strategy, framing VISA Steel as the ideal local partner—respected, connected, and already operating in the region. He also tied the bet directly to India’s macro story: as infrastructure, housing, and transportation needs accelerated, Indian steelmakers would need more high-quality coke, and VISA SunCoke aimed to become the supplier of choice.

On paper, the structure looked disciplined. A local partner who knew the market. Minority ownership to cap the exposure. And an operating plant instead of a risky greenfield build.

Then the world changed.

In 2015 and 2016, the global steel market cracked under the weight of Chinese overcapacity, which pushed cheap steel into international markets and crushed pricing. Indian steel producers got squeezed. Financial stress spread across the ecosystem. Customers defaulted. And VISA Steel itself fell into severe distress. The “stable cash flow” joint venture didn’t just underperform—it became a problem asset.

The damage showed up quickly in SunCoke’s results. In one quarter, SunCoke reported a loss of $0.36 per share versus expectations that called for a small profit, driven in large part by a non-cash $19 million asset write-down tied to the Indian joint venture. And the bad news didn’t stop with one impairment. Over time, SunCoke recorded additional adjustments related to its interest in VISA SunCoke—and the company ultimately wrote off the full value of its original investment. The growth engine was gone.

The India episode is a sharp case study in how industrial expansion can fail when the underlying assumptions don’t travel. Fast-growing emerging-market demand doesn’t guarantee attractive returns. Local partners can become the source of risk rather than a buffer against it. Commodity cycles hit harder when financing is fragile and contract enforcement is less reliable. And minority ownership, while it limits upfront dollars, also limits control when things start to unravel.

Most of all, India exposed the real boundary of SunCoke’s model. In the U.S., “contracted infrastructure” works because counterparties are creditworthy and contracts are enforceable. SunCoke’s core strength was running cokemaking facilities safely and efficiently—not navigating a volatile emerging-market business environment where those foundations can give way.

VI. The Domestic Crisis: U.S. Steel's Decline & The Granite City Shutdown

While the India bet was unraveling, a more dangerous problem was forming at home. The same wave of Chinese overcapacity that crushed steel markets abroad was hammering American producers too. For SunCoke, that pressure concentrated in one place: Granite City, Illinois—where its newest, most advanced domestic coke plant sat bolted to U.S. Steel’s blast furnaces.

On November 23, 2015, U.S. Steel announced it would temporarily idle its blast furnace and related steelmaking operations at Granite City Works. SunCoke’s response was immediate and carefully worded. SunCoke Energy, Inc. and SunCoke Energy Partners, L.P. issued a statement saying they had a longstanding relationship with U.S. Steel and that they expected U.S. Steel to honor the take-or-pay contract to supply coke to Granite City through 2025.

That statement captured the whole tension of SunCoke’s model in one sentence. The contract was supposed to be the moat. But when your customer shuts the furnace, the product has nowhere to go. And take-or-pay only protects you if the other side can pay.

Granite City wasn’t a random facility in the portfolio. SunCoke had been operating a coke-making facility at Granite City Works since 2009, supplying the coke that makes blast furnace steel possible. It was also a reminder that this complex had lived through shocks before. Granite City had been “idled” in 2009 and again in 2015. Back in 2009, when the contract was approved, steel sales were strong—then, within months, demand collapsed and domestic production fell sharply. In both idlings, union officials expressed confidence the plant would eventually come back. Sometimes they were right. Sometimes the wait was longer than anyone wanted to admit.

From 2015 to 2018, Granite City Works stayed idled amid falling prices, slowing demand, and foreign competition. The shutdown cost roughly 1,800 jobs. When demand improved, the plant restarted in June 2018 and brought back about 800 jobs.

For SunCoke, the financial question wasn’t just volume. It was credit. In a commodity downturn, a distressed steelmaker can do all the things that make long-term contracts feel theoretical: default, push for renegotiation, or seek relief through bankruptcy. SunCoke’s contracts were only as durable as its counterparty’s willingness and ability to perform.

In the event, U.S. Steel survived and honored its commitments, but it wasn’t a “set it and forget it” victory. SunCoke had to navigate the moment with a mix of enforcement and pragmatism—working with U.S. Steel on volume adjustments while protecting its contractual rights.

The episode also put a spotlight on SunCoke’s biggest structural exposure: customer concentration. The company’s coke sales were dominated by a small group of integrated steelmakers—U.S. Steel, ArcelorMittal (later sold to Cleveland-Cliffs), and AK Steel (also acquired by Cleveland-Cliffs). When that customer set catches a cold, SunCoke doesn’t have a long list of alternative buyers waiting in line.

And Granite City didn’t become “resolved” after 2018. In 2019, the facility went through another series of layoffs. In 2023, Blast Furnace B was idled, with U.S. Steel attributing the move and associated layoffs to decreased demand tied to the UAW strikes.

The story has continued into the 2020s with a new layer of scrutiny: emissions and the long-term future of blast furnace steelmaking in the region. SunCoke’s Granite City facility—Gateway Energy—emitted more than 492,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2022. U.S. Steel’s neighboring Granite City Works wasn’t included in that comparison because, with both blast furnaces shuttered, the facility was not burning coke at the time. Meanwhile, the broader uncertainty around U.S. Steel itself has only increased. Nippon Steel announced a deal to buy U.S. Steel for nearly $15 billion, but officials have pushed for it to be blocked. And before that deal, SunCoke made an offer for Granite City Works’ blast furnaces that union leaders said in 2022 could cost the region roughly 1,000 jobs.

So Granite City became the clearest demonstration of what SunCoke really owned. Not just ovens and contracts—but a set of relationships tied to aging industrial assets, local politics, and the solvency of a small number of customers.

The investor lesson from this period is simple and uncomfortable: “well-contracted” doesn’t mean “risk-free.” Take-or-pay shifts the risk from spot prices to counterparty health. SunCoke’s structure held up better than it would have in an uncontracted world, but it also made one truth unavoidable: diversification—of customers, and eventually of businesses—matters at least as much as the fine print in the contract.

VII. The Great Simplification: Dropping the MLP Structure

By 2019, SunCoke had made it through the India writeoff and the Granite City shock. But another problem had quietly become just as constraining: the way the company was organized. The Master Limited Partnership structure that was supposed to lower taxes and unlock cheap capital had started doing the opposite. It was no longer a tailwind. It was an anchor.

To see why, you have to understand what MLPs were built for. An MLP is a partnership that trades publicly like a stock, but generally avoids corporate-level income tax because income flows through to the unitholders. The tradeoff is that MLPs are designed to pay out most of their cash and operate within a narrower set of qualifying activities. That’s perfect for pipeline-style businesses: predictable, steady, and built to throw off distributable cash.

SunCoke leaned into that trend. In 2013, it floated SunCoke Energy Partners, L.P. (SXCP) as an MLP and used it as part of a broader push into logistics, including the acquisition of Lake and Kanawha River Terminals.

At first, it looked like the standard energy-infrastructure playbook working exactly as advertised. SXCP held many of the prime assets and paid distributions at attractive yields. Meanwhile, SunCoke—the parent—kept the general partner interest, including incentive distribution rights that entitled it to a growing share of SXCP’s cash flows once certain distribution targets were hit. In the early 2010s, investors understood this structure and rewarded it.

Then the ground shifted under the entire MLP universe. Tax changes dulled the benefits. Institutions tired of the complexity and governance quirks. And as the energy sector buckled in 2014–2016, anything that smelled even remotely oil-and-gas-adjacent got hit in sympathy. The result was brutally simple: the cost of capital went up, right when MLPs most needed friendly capital markets to fund growth.

As SunCoke later put it plainly, the MLP “no longer serve[d] its original purposes of providing a more advantageous cost of capital and access to MLP equity markets.”

So the company did what a lot of former MLP sponsors eventually did: it collapsed the structure. In February 2019, SunCoke Energy, Inc. and SunCoke Energy Partners, L.P. announced a definitive agreement for SXC to acquire all SXCP common units it didn’t already own, in a stock-for-unit merger. The “Simplification Transaction” was expected to close in late Q2 or early Q3 of 2019. SXCP’s unaffiliated unitholders would receive 1.40 shares of SXC for each SXCP unit, a deal the companies said represented a premium to recent trading levels. After the merger, SXCP would become a wholly owned subsidiary, the SXCP units would stop trading publicly, and the incentive distribution rights would be eliminated.

The pitch was classic simplification language, but the underlying goal was real: get rid of the structure that was forcing cash out the door and creating friction everywhere else. SunCoke said the combined company would have a cleaner corporate footprint, more float and trading liquidity, immediate cash flow accretion, and a lower cost of funding—along with more flexibility to fund growth initiatives and return capital to shareholders.

Not everyone was thrilled. Two months after the merger was announced, a lawsuit challenged the deal. And at the time of the announcement, SunCoke and SXCP said the transaction implied an enterprise value for SXCP of about $1.52 billion—so this wasn’t a minor reshuffling.

In the end, SunCoke said the simplification produced roughly $10 million per year in synergies, coming from both cost savings and tax benefits. But the bigger impact wasn’t the synergy line item. It was what the company became afterward.

Under the old setup, SunCoke increasingly looked like a yield product—optimized to distribute cash, constrained in what it could retain, and dependent on public markets staying open and friendly. Post-simplification, it could behave like an industrial operator: consolidate cash flows, keep more of what it generated, strengthen the balance sheet, and choose how to deploy capital—debt reduction, buybacks, selective investment—without having the corporate structure dictate the answer.

That’s the core lesson of the 2019 shift. Financial engineering can be an advantage, until it isn’t. Structures that thrive in one market regime can turn into self-inflicted wounds in the next. And sometimes the most value-creating move isn’t a new growth project—it’s admitting the old framework has stopped working, and having the discipline to unwind it.

VIII. Logistics Pivot: Beyond Coke

Even as SunCoke was dealing with India, Granite City, and the messy unwind of the MLP structure, it was also doing something much quieter—and ultimately more important for the company’s long-term stability.

It was building a second leg.

Over time, SunCoke assembled a logistics platform that handles coal and other bulk materials through a network of terminals. And eventually, that platform grew into a business that would contribute roughly 40% of EBITDA—real diversification, not just a slide-deck promise.

The pivot started early. In 2013, SunCoke expanded into logistics with the acquisition of Lake and Kanawha River Terminals. Then, in 2015, it made the defining move: it bought a Gulf Coast export hub and, with it, a much bigger opportunity set.

SunCoke Energy Partners, L.P. entered into an agreement with Raven Energy Holdings, LLC—an affiliate of The Cline Group—to acquire Convent Marine Terminal in Convent, Louisiana, for $412 million. Fritz Henderson framed it as a strategic match: a “preeminent export asset” that would be accretive from day one, generating stable cash flows for SXCP, supporting higher distributions, and boosting the incentive distribution payments flowing back to the general partner.

In plain English: Convent was exactly the kind of asset the MLP structure was built to own.

Convent Marine Terminal is one of the largest export facilities on the U.S. Gulf Coast. It can transload up to 15 million tons per year of coal and other raw materials, and it sits in a logistics sweet spot—on the Lower Mississippi River, with the ability to move product by river barge, ocean vessel, truck, and rail. Zoom out, and this fits into a broader network: terminals positioned to serve the Gulf Coast, East Coast, Great Lakes, and international markets, with access into major rail networks including Norfolk Southern, Canadian Northern, and CSX. Across the system, SunCoke’s terminals have roughly 40 million tons of annual processing capacity.

Convent wasn’t just big; it was getting better. The terminal completed a $120 million expansion to modernize the facility and improve efficiency. It’s also the only bulk terminal in the region with direct rail access for ocean-going shipments. It has two independent shiploading systems, including a newer shiploader capable of accommodating cape-sized vessels, plus about 1.5 million tons of ground storage and a set of inbound and outbound capabilities that make it a cost-effective transload option for a range of bulk materials and liquids.

This is the strategic logic in one move: diversify away from coke, lean into fee-based infrastructure, and use capabilities SunCoke already had. If you can reliably run a cokemaking plant—moving massive volumes of raw material, managing tight specs, operating safely, and coordinating with industrial customers—you can run a terminal. It’s a natural adjacency.

Operationally, SunCoke describes logistics as handling and mixing services for coal and other aggregates at Convent Marine Terminal, Lake Terminal, and Kanawha River Terminals.

Economically, it’s a different animal than coke. Terminals earn fees based on volumes handled, with less direct exposure to commodity prices. Take-or-pay contracts can provide a revenue floor, while spot volumes add upside when markets cooperate. Maintenance capital tends to be lower than what it takes to keep a coke battery running. And the network itself—permits, locations, rail and water access—isn’t something a competitor can replicate quickly or cheaply.

By 2024, logistics was a meaningful contributor to SunCoke’s consolidated results. The company pointed to progress during the year, including a new coal handling agreement at Kanawha River Terminal and an extension of the coal handling agreement at Convent Marine Terminal.

And while logistics doesn’t magically sever SunCoke’s ties to coal and steel—those markets still drive a lot of the volume—it does reduce the company’s dependence on coke production specifically. It also gives SunCoke something valuable in a world where blast furnace steel may slowly shrink: flexibility. Terminals can be repurposed. As markets change, infrastructure like this can shift to other bulk materials, from construction aggregates to industrial inputs.

For investors, this is what disciplined capital allocation looks like in a mature, cyclical business. SunCoke didn’t try to outgrow its industry with a high-risk bet. It built an adjacent platform with better long-term characteristics—one that made the core business less fragile.

IX. The Coal Conundrum & Energy Transition

You can’t tell the SunCoke story without addressing the elephant in the room: steel is slowly moving away from coal-based blast furnaces and toward electric arc furnaces. That shift is both the existential threat hanging over the business and the reason it can still be a compelling cash-flow story in the meantime.

At the simplest level, the two routes to steel run on different power sources. Blast furnaces depend on coke. Electric arc furnaces use electricity. That single difference cascades into everything else—especially emissions. Because EAFs don’t rely on coke as the core fuel and reducing agent, they can produce dramatically less carbon dioxide than the traditional blast furnace route—often cited as up to 85% less.

And the industry isn’t debating whether this transition is real. It’s happening. EAF’s share of global steel production is expected to rise from about 28% to 41% by 2030, with the shift particularly pronounced in North America and Europe.

EAFs also have structural advantages that operators love. You can make steel with a 100% scrap-metal feedstock, which is generally less energy-intensive than starting from iron ore. And EAFs are flexible. Blast furnaces are built to run continuously—once you light them, you really don’t want to turn them off. EAFs can ramp up and down far more easily, and can be idled at lower cost when the cycle turns.

For coke producers, the implication is brutal: EAFs don’t need coke ovens, sinter plants, or blast furnaces at all. Add in cheaper renewable power over time and the economics get even better for scrap-based steelmaking. Every new EAF project is, in some sense, demand that will never belong to SunCoke.

But here’s the part that keeps the story from collapsing into “blast furnaces are dead.” Globally, the blast furnace route still accounts for roughly 70% of steel production. The shift is real, but it’s uneven—and slower than the headlines suggest.

In the U.S., it’s further along. EAF already represents roughly 70% of domestic production, meaning SunCoke’s home market is ahead of the world in moving away from blast furnaces. That’s not comforting if you make coke. But it does clarify the playing field: SunCoke isn’t betting on a reversal. It’s operating in a market that’s already living in the future.

The real nuance is in what blast furnaces still do better. Integrated mills—blast furnaces paired with basic oxygen furnaces—have historically dominated “flat products,” like sheet steel and heavier plate. EAF players have pushed into this market too; Nucor expanded into flat products back in 1987 while still using EAF production. But certain grades remain hard to replicate without integrated steelmaking. Automotive-grade flat-rolled steel is the classic example, where purity and consistency matter.

That’s why Granite City keeps coming up in this story. SJ18—a lightweight, hard steel used in automotive production—is only made in Granite City in the U.S., and other mills haven’t been able to replicate it. As one observer put it: “There are capabilities of high-grade production at Granite City no other integrated facility can match in the United States.” Another was even blunter: “It’s quite a niche that no one else can make it. Others have tried and failed miserably.”

This is the reality SunCoke leans on in its positioning. Yes, EAF share keeps rising. But blast furnaces don’t vanish on a schedule like a software deprecation. They’re multi-billion-dollar complexes with useful lives measured in decades. The transition tends to look less like a cliff and more like a slow retreat—mills idling, consolidating, restarting, and idling again, all while the remaining assets fight to stay relevant by serving the hardest-to-make products.

That slow-motion dynamic shows up in how management talks about the near term, too. They’ve pointed to challenging market conditions: tepid steel demand, oversupply in the seaborne coke market, and pressure on coke pricing—especially in spot volumes. The message is basically: the cycle can get ugly, but with a solid balance sheet and healthy cash flow, SunCoke expects to ride it out.

Then there’s the ESG layer, which creates a different kind of constraint. Even if SunCoke isn’t a coal producer, it’s coal-adjacent enough to be screened out, overlooked, or penalized with a higher cost of capital. SunCoke’s line—“we’re steel infrastructure, not coal production”—only goes so far when many investors screen by category rather than by business model.

So the company’s approach has been pragmatic, and honestly, pretty rational for a business facing structural decline: harvest cash from existing assets, return capital to shareholders, and avoid sinking money into long-lived growth projects that might not have a long-lived market. In other words, don’t pretend this is a forever story. Run it like what it is—a durable, essential part of today’s steel supply chain with a shrinking long-term footprint.

X. Modern Capital Allocation: Debt Paydown, Buybacks, and Pragmatism

After the 2019 simplification, SunCoke started acting less like a financial structure and more like what it actually is: a mature industrial operator. The playbook has been straightforward—pay down debt, return cash to shareholders, and run the business for durable returns instead of swinging for growth.

In 2024, that approach showed up clearly in the numbers. Net income attributable to SunCoke was $95.9 million, or $1.12 per diluted share. Consolidated Adjusted EBITDA was $272.8 million, and operating cash flow was $168.8 million.

A big contributor was operational performance—plus a one-time gain from eliminating the majority of legacy black lung liabilities. Together, those helped SunCoke finish the year above the high end of its revised guidance range. The company also posted record safety performance, with a Total Recordable Incident Rate of 0.50. And on the diversification front, logistics kept moving in the right direction: SunCoke signed a new coal handling agreement at Kanawha River Terminal and extended its coal handling agreement at Convent Marine Terminal. With cash generation holding up, the company increased its quarterly dividend by 20%.

That dividend hike matters because it’s a signal: management believes the cash is real, not just cyclical noise. But they’ve also been blunt about what’s coming next.

Heading into 2025, SunCoke expects a hit from the Granite City cokemaking contract extension, which resets economics lower. At the same time, management anticipates lower margins on higher spot coke sales, driven by a tepid steel demand outlook and oversupply in the seaborne coke market pressuring coke pricing.

Put it together, and guidance reflects a step down. SunCoke expects full-year 2025 consolidated Adjusted EBITDA of $210 million to $225 million, a meaningful decline from 2024 that captures both tougher contract terms and a tougher market.

The other part of the capital allocation story is what SunCoke is choosing to become. In 2025, the company completed the acquisition of Phoenix Global, a provider of mission critical services to major steel-producing companies.

Management described Phoenix as a strong strategic fit because it expands and diversifies SunCoke’s customer base and enhances its capabilities as a supplier of industrial services to steelmaking customers. Read that another way: this is SunCoke continuing to widen the definition of what it sells—from coke, to logistics, to a broader set of steel-adjacent services that can ride alongside customers even as the production mix shifts.

For investors, the thesis increasingly lives in the framework, not the growth rate. SunCoke has been explicit: this isn’t a “compound forever” story. It’s a cash generation and cash return story, where outcomes depend on a few critical levers:

- Maintaining contract volumes and pricing at reasonable levels through renewals

- Managing operating costs and capital requirements efficiently

- Returning excess cash to shareholders through dividends and buybacks

- Opportunistically building the logistics and services businesses

- Avoiding capital-destroying investments in potentially stranded assets

This is the mature-business playbook. The skill isn’t optimism. It’s discipline—about valuation, about the balance sheet, and about not confusing “still essential today” with “guaranteed for decades.”

XI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

SunCoke’s fifteen-year run—from a tucked-away Sunoco subsidiary to a standalone public company—ends up being a surprisingly clean set of lessons about how old-economy businesses actually win, lose, and survive. A few frameworks make the pattern easier to see.

The Industrial Spin-Off Playbook: Spin-offs create value when they liberate a business from the wrong parent. SunCoke gained a dedicated leadership team, direct access to capital, and the ability to make decisions for steel customers instead of refining customers—all things that were hard to prioritize inside an oil company. But a spin-off also shows up with whatever baggage it was handed. SunCoke didn’t get to redesign its asset footprint, customer concentration, or contract mix on day one. The spin created the opening; the real story was whether management could execute through cycles.

Contracted Infrastructure Businesses: Take-or-pay contracts can make a commodity-adjacent business feel like infrastructure—but only up to a point. They smooth revenue and protect against volume whiplash, which is a big reason SunCoke could get through Granite City without collapsing. But they also concentrate risk in a handful of counterparties, and they don’t stop reality from showing up at renewal. The practical lesson is to value contracts for the cash you realistically expect to collect, discounted for counterparty health and future renegotiation pressure—not for what the paper says in a vacuum.

Managing Commodity Exposure: SunCoke does a good job of pushing coal-cost volatility through to customers, which reduces the most obvious commodity risk. But it can’t pass through the steel cycle. Steel demand determines whether customers are healthy, whether blast furnaces run, and what terms look like when contracts reset. The real lesson here is to look past the company’s direct exposure and model the second-order exposure through the customer base.

International Expansion Risk: India was the painful reminder that industrial expertise doesn’t automatically travel. You can build and operate great equipment and still lose money if the local partner fails, if customers can’t pay, or if contracts don’t protect you the way they do at home. Add currency and political risk, and the downside compounds fast. The takeaway is simple: international expansion in heavy industry demands conservatism—cap the capital at risk, avoid over-relying on one counterparty, and keep real exit options.

Capital Structure Matters: The MLP era is a case study in how financial engineering can flip from advantage to constraint. The structure worked when investors rewarded yield and complexity, then became a tax and governance headache when the market regime changed. SunCoke’s decision to simplify—essentially admitting the old model had stopped working—wasn’t glamorous, but it bought flexibility. For investors, the rule is to be skeptical of complexity unless management can clearly explain how it lowers the cost of capital or increases long-term cash to common shareholders.

The Mature Business Dilemma: This is the “harvest versus transform” decision every mature industrial company eventually faces. SunCoke largely chose harvest: run the core for cash, protect the balance sheet, and build adjacencies like logistics and services rather than swing for a moonshot reinvention. For investors, the question isn’t whether that’s inspiring. It’s whether the harvested cash, returned over time, is enough given the price you pay and the number of years blast furnace steel remains durable.

Environmental and Social License: SunCoke operates inside one of the most regulated, most politically fragile industrial categories there is. Heat-recovery technology can improve efficiency and reduce certain impacts, but it doesn’t change the core issue: cokemaking is inherently dirty, and communities and regulators know it. ESG pressure shrinks the investor base and can raise the cost of capital. Over time, those pressures likely intensify—creating real closure risk, but also, paradoxically, scarcity value for the permitted capacity that survives.

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you wanted to start a competing coke producer tomorrow, you’d run into three walls immediately: cost, time, and permits. A modern facility takes hundreds of millions of dollars, years to build, and—more importantly—environmental approvals that are now close to impossible to secure for new cokemaking operations. The plants that exist today largely operate under grandfathered regulatory regimes. So SunCoke’s protection isn’t just “we’re better.” It’s that the system makes it extraordinarily hard for anyone new to show up.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

SunCoke’s critical input is metallurgical coal, sourced from suppliers like Arch Resources and Peabody Energy. Met coal is more specialized than thermal coal, with fewer viable sources, which gives suppliers some leverage. But it’s still a commodity within quality grades, and that limits how much any single supplier can dictate terms. SunCoke’s logistics footprint also helps—less true vertical integration than a miner, but enough infrastructure and optionality to strengthen its hand. One more nuance: transportation matters. For a heavy, bulky input, proximity can create regional lock-in, which can tilt advantage toward suppliers located near a given plant.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

On the other side of the table are a handful of enormous customers: Cleveland-Cliffs (after acquiring AK Steel and ArcelorMittal USA’s operations), U.S. Steel, and ArcelorMittal’s Brazilian subsidiary. That kind of concentration naturally gives buyers power—there just aren’t that many blast-furnace steelmakers left to sell to.

But the contract structure blunts it. Take-or-pay agreements typically lock in volumes and economics for long stretches, often 10 to 15 years, so buyer power is limited while the contract is in force. And switching isn’t trivial. Coke quality specs, proximity, and day-to-day operational integration create real stickiness. The catch is timing: at renewal, the power balance swings back toward the steelmaker. The reset in Granite City economics is the clearest example of how much leverage buyers can have when it’s time to reprice.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH (and Growing)

The substitute risk isn’t another coke supplier—it’s a different way of making steel. Electric arc furnaces don’t need coke at all. They melt scrap using electricity, and they’re already the dominant production method in the U.S., at roughly 70% of output, with share continuing to rise.

That sounds existential, and in the long run it is. But it’s not a fast-moving cliff. Some grades still require blast-furnace production, and the installed base of blast furnaces is built to run for decades. So the substitution threat is structural rather than cyclical—real, but slow.

Industry Rivalry: LOW-MODERATE

This is not a market with dozens of players undercutting each other every quarter. The domestic landscape is a small set of producers: SunCoke as the major independent, coke plants owned by steelmakers themselves, and limited imports. During contract terms, there’s little room for price-war behavior; the competition is mostly for the next contract, not today’s shipment. Geography also limits head-to-head battles—plants tend to serve nearby mills because shipping coke far gets expensive fast. The risk is what happens as the market shrinks: fewer blast furnaces means fewer renewals, and that can intensify rivalry at the margins over the remaining demand.

Overall Industry Attractiveness: Porter's framework lands on a business that’s protected by formidable barriers to entry, but facing a substitute-driven decline that no amount of execution can fully stop. That’s why SunCoke can be profitable today—and why the key question is duration. For investors, the “attractiveness” lives less in the industry’s growth and more in entry price, time horizon, and whether management keeps executing the cash-return playbook without making stranded-asset bets.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers is a useful lens here because it forces a simple question: what, exactly, lets SunCoke earn returns that don’t immediately get competed away?

Scale Economies: MODERATE (3/10)

There are real scale benefits in cokemaking. Bigger plants running closer to full utilization tend to have lower unit costs. But most of that advantage is captured at the facility level, not at the corporate level. In other words, one well-sized, well-run plant gets you most of the scale you’re going to get. SunCoke’s multi-plant footprint helps with purchasing and spreading overhead, but it’s not the kind of scale that completely changes the competitive game.

Network Economies: NOT APPLICABLE (0/10)

This isn’t a network business. A steel mill doesn’t value SunCoke more because other steel mills also buy from SunCoke. More customers don’t create a reinforcing loop the way they would in a marketplace or a payments network.

Counter-Positioning: NOT APPLICABLE (0/10)

SunCoke doesn’t have a disruptive model that incumbents can’t adopt without hurting their own economics. There’s no “we do it this new way and they can’t follow” dynamic.

Switching Costs: HIGH DURING CONTRACT, MODERATE AT RENEWAL (7/10 / 4/10)

During a contract term, switching costs are real. Coke quality and consistency matter; getting it wrong can impair furnace performance and steel quality. Proximity matters too, because coke is heavy and expensive to move. And once operations are integrated—delivery cadence, specs, troubleshooting—relationships get sticky.

But the clock is always ticking toward the next negotiation. At renewal, switching becomes much more feasible, and leverage shifts back toward the steelmaker. So this power is strong, but it’s not permanent; it’s strongest inside the contract window.

Branding: LOW (2/10)

This isn’t consumer branding. Nobody is paying more for “premium” coke because the logo feels trustworthy. What matters is reputation: reliable delivery, consistent quality, and being a partner a steel mill can count on. That’s meaningful, but in Helmer’s framework, it’s not a deep branding moat.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE-HIGH (7/10)

This is SunCoke’s most durable power: the right to operate.

Permits for coke plants—especially modern facilities in the U.S.—are extraordinarily difficult to secure under today’s environmental rules. The capacity that already exists has scarcity value because it’s effectively grandfathered, upgraded, and maintained within a regulatory framework that new entrants can’t easily replicate.

Geography compounds it. Being located near steel mills and coal supply routes isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s part of the economics. The best locations are already taken, and hauling coke long distances quickly becomes uneconomic.

Process Power: MODERATE (5/10)

SunCoke has decades of operating knowledge: heat-recovery technology, safety systems, quality control, and the day-to-day execution needed to keep huge industrial assets running. That expertise matters. But it’s not magical. A determined, well-capitalized competitor could replicate much of it over time. This is advantage through accumulated competence, not a proprietary secret.

Overall Power Assessment: SunCoke’s advantage mostly comes down to Cornered Resource (permits and positioning) and Switching Costs (while contracts are in force). That’s a real moat—but it’s a moat around a market that’s gradually shrinking as steelmaking shifts away from blast furnaces.

The investment implication is the same theme we’ve been circling all episode: SunCoke is a melting ice cube with a moat. The moat can slow the melt and protect returns along the way, but it can’t reverse the underlying trend. That’s why valuation and capital allocation discipline matter more here than dreams of long-term growth.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

Blast furnace steelmaking probably isn’t vanishing on the timeline the loudest headlines imply. Steel plants are massive, long-lived systems, and as long as a meaningful number of blast furnaces stay lit, coke stays essential. Layer on the political and economic tailwinds—reshoring, industrial policy, and the desire for domestic supply chain security—and the argument is that U.S. steel output holds up better than feared, which keeps domestic coke demand from collapsing.

Then there’s structure. This is an oligopoly with brutal barriers to entry. New coke capacity is extraordinarily hard to permit and expensive to build, so incumbents don’t face a wave of new competitors. That scarcity can support rational pricing and decent returns, even in a mature market.

SunCoke’s second leg helps, too. Logistics diversifies the cash flows and offers a path to modest growth that doesn’t depend entirely on blast furnace utilization.

Finally, bulls point to capital allocation and valuation. SunCoke has leaned into debt reduction, dividend growth, and selective acquisitions to create shareholder value without needing revenue growth. And the stock can trade at a meaningful discount to replacement cost—these are assets you can’t practically recreate at anything like the company’s market value. If the cash flows prove durable, the free cash flow yield can look compelling versus other options in the market.

There’s also an endgame argument: SunCoke could be acquired. A steelmaker might value supply security, and a financial buyer might see a cash-generating infrastructure-like business to own and harvest.

The Bear Case:

The bear view starts with the uncomfortable premise that the decline isn’t theoretical—it’s structural, and it’s getting worse. EAF share keeps rising, and the industry is building new EAF capacity far more enthusiastically than it’s reinvesting in blast furnaces. Even if blast furnaces don’t disappear overnight, the direction of travel is clear.

On top of that is customer risk. SunCoke sells to a small handful of giant steelmakers, and that concentration can turn a “contracted” business into a binary one. If a major customer restructures, idles furnaces for extended periods, or simply loses the ability to pay, the take-or-pay contract can become far less protective than it looks on paper. Uncertainty around U.S. Steel’s future ownership, and Cleveland-Cliffs’ ongoing optimization of its blast furnace footprint, only adds to that anxiety.

Then comes regulation and perception. Cokemaking is one of the most scrutinized industrial processes in the country. Tighter environmental requirements could force closures or require expensive compliance spending. And even if operations are stable, ESG-driven screens can shrink the investor and buyer universe, putting a ceiling on valuation regardless of near-term fundamentals.

Bears also focus on the slow squeeze inside the model. Contract renewals can increasingly favor the steelmakers, and the Granite City reset at lower economics may be a preview, not a one-off. Outside of contracts, spot coke pricing can be pressured by seaborne oversupply. And as plants age, maintenance capital can rise at exactly the wrong time—eating the free cash flow that investors are counting on.

The core conclusion is blunt: there’s no obvious pathway to durable growth here, only managed decline. The stock may look cheap because it is.

The Realistic Case:

Both sides have a point. SunCoke is a cash-generative business with real moats that protect current returns, but those moats don’t change the long-term trajectory as steelmaking shifts away from blast furnaces.

What you earn from here largely comes down to four variables:

- Entry valuation: Paying the right price is most of the battle

- Management capital allocation: Returning capital and protecting the balance sheet creates value; chasing growth for its own sake destroys it

- Contract renewal terms: Each reset answers the question of who has the leverage

- Blast furnace duration: The real clock is how long the remaining blast furnace fleet stays economical

In that framing, SunCoke looks more like a 7–10 year duration investment than a 20+ year compounder. It can make sense as part of a diversified portfolio—an income-and-capital-return story—so long as you’re willing to actively track the steel transition and the health of a small number of customers.

XV. Key Metrics to Track

If you want to keep a clean read on where SunCoke is headed, you don’t need a spreadsheet with fifty tabs. You need to watch the few levers that actually move the story. Three matter most:

1. Contract Renewal Terms (Pricing and Duration)

This is the tell. SunCoke can look “infrastructure-like” as long as contracts lock in volumes, preserve take-or-pay protections, and reset at workable economics. But renewal is where bargaining power shows up in real life. Do terms hold, or do steelmakers squeeze pricing and shorten duration because demand is weaker and alternatives are improving?

Granite City resetting at lower economics is a warning light. The next few renewals will determine whether that was a one-off tied to a specific facility and moment—or the new normal.

Where to find it: earnings call commentary, 10-K contract disclosures, and investor presentations with commercial updates.

2. Domestic Coke Adjusted EBITDA per Ton

This is the simplest way to watch the health of the core business without getting distracted by volume swings. EBITDA per ton captures both sides of the equation: what SunCoke is earning on each ton of coke and how efficiently it’s running the plants.

If this metric drifts down, it usually means one of two things: contract economics are getting worse, or costs are creeping up. If it stays stable—or even improves—despite a choppy steel backdrop, that’s a sign of real operational discipline and more resilience than the headline narrative suggests.

Where to find it: quarterly earnings releases include segment results; you can estimate this by dividing Domestic Coke Adjusted EBITDA by reported sales volumes.

3. Logistics Segment EBITDA as Percentage of Total

This is the diversification scoreboard. SunCoke’s long-term risk is tied to blast furnaces, so the question is whether the logistics platform is becoming large enough to matter—enough to smooth cycles, broaden the customer base, and reduce dependence on coke over time.

If logistics continues to take a larger share of total EBITDA, the “second leg” is doing its job. If it stalls, the company becomes more exposed to exactly the decline it’s trying to manage.

Where to find it: segment results in quarterly earnings releases; calculate logistics share as a percentage of consolidated Adjusted EBITDA.

XVI. Epilogue: What Does the Future Hold?

By late 2025, SunCoke was doing what it has spent the last decade learning to do: operate through uncertainty without pretending it can control the cycle. Steel demand remained choppy, blast furnace utilization could swing fast, and contract resets were getting tougher. At the same time, SunCoke kept widening the lane it wanted to run in.

A big marker of that was Phoenix Global. In 2025, SunCoke completed the acquisition of Phoenix, a provider of mission-critical services to major steel-producing companies. Strategically, it was a continuation of the same logic as the logistics build-out: expand beyond coke into work that stays relevant as steelmakers change how they produce steel.

The backdrop for all of this was still dominated by one relationship: U.S. Steel. The proposed Nippon Steel acquisition of U.S. Steel faced intense political opposition, leaving the future of that ecosystem murky. Nippon had agreed to buy U.S. Steel for nearly $15 billion, but President Biden, President-elect Trump, and other officials signaled they wanted the deal blocked. For SunCoke, the issue wasn’t Washington drama for its own sake—it was what any ownership change might mean for blast furnace decisions, plant investment, and long-term contracting behavior.

Granite City captured that uncertainty in miniature. Before the Nippon deal emerged, SunCoke made an offer for Granite City Works’ blast furnaces—an idea union leaders said could cost the region roughly 1,000 jobs. That local effort stalled, but it could be revived. Meanwhile, Nippon leadership had not commented on what it intended to do with Granite City’s steel mill if the broader purchase went through. The point isn’t which specific outcome happens. It’s that SunCoke’s fate is still tethered to decisions made around a small number of massive, politically sensitive assets.

Operationally, SunCoke’s messaging stayed consistent: a solid balance sheet, healthy cash flow generation, and a steady focus on safety, reliability, and disciplined capital allocation—including the expected continuation of the quarterly dividend. The tone wasn’t “we’ll grow through this.” It was “we’ll manage through this.”

From here, the paths are pretty clear:

Stay Independent and Harvest: Keep doing what’s worked—run the assets well, return cash to shareholders, and accept that the core market slowly changes under your feet.

Pursue Acquisition: Explore buying blast furnace assets, as it contemplated at Granite City, which could shift SunCoke toward a more integrated metallics footprint.

Accelerate Logistics and Services: Push harder on the second and third legs—terminals, handling, and industrial services—potentially including acquisitions beyond Phoenix Global.

Accept Being Acquired: If the right strategic or financial buyer shows up, selling the company could outperform the returns of staying independent and harvesting cash over time.

Zoom out far enough and SunCoke becomes less about one company and more about the next era of American heavy industry. Reshoring. Industrial policy. Tradeoffs between decarbonization and industrial capability. The tension between environmental goals, energy security, and domestic production. Those forces will shape what steelmaking looks like in the U.S., and that will shape what “essential” means for coke.

That’s why SunCoke matters beyond its modest market capitalization. It sits at the intersection of legacy infrastructure and the energy transition, with just enough moat to throw off real cash—and just enough structural decline to force hard choices.

And that’s the paradox at the heart of the story: a “boring” company making an obscure product for a shrinking corner of the market ends up being a masterclass in adaptation. From Big Oil parent to independent spin, from global ambitions to an emerging-market writeoff, from MLP complexity to C-corp simplicity, from coke dependence to logistics and services—SunCoke’s journey is what industrial survival actually looks like.

The broader lesson, for founders and investors, is the same one SunCoke keeps relearning: business models have lifespans; moats protect but don’t magically create growth; capital allocation matters most when growth is constrained; and some of the most instructive stories live in the least glamorous parts of the economy.

XVII. Further Reading & Resources

Essential Sources:

-

SunCoke Energy SEC Filings — Start with the 2011 S-1 for the “origin story” of the spin. Then use the annual 10-Ks for how the business actually works: contract structures, customer concentration, and risk factors. And if you want the cleanest explanation of why the company walked away from the MLP era, read the 2019 proxy around the simplification.

-

"American Steel" by Richard Preston — A narrative history of the U.S. steel industry’s reinventions and collapses. It’s the fastest way to build intuition for the world SunCoke sells into.

-

CRU Group Industry Reports — One of the core institutional sources for steel and metallurgical coal market data and analysis. Useful for understanding how “the market” thinks about supply, demand, and cycles.

-

SunCoke Investor Presentations (2015-2025) — A time-lapse of management’s strategy in their own words: the logistics build-out, how they talk about contracts and capital allocation, and how the energy transition changes the framing over time.

-

"The Prize" by Daniel Yergin — It’s not about coke, but it is about how energy commodities, geopolitics, and infrastructure interact—exactly the mental model you need for this story.

-

American Iron and Steel Institute Publications — Ground-truth material on steelmaking routes, industry structure, and market dynamics. Helpful for the “how the system works” layer behind the narrative.

-

Trade Publications: American Metal Market, Argus Media — Where the day-to-day reality shows up: pricing, outages, idlings, restarts, and the headlines that eventually become earnings call talking points.

-

Cleveland-Cliffs and U.S. Steel Investor Materials — The customer viewpoint. These presentations and filings reveal blast furnace strategy, capital spending priorities, and how seriously each company is taking the shift toward EAF.

-

Academic Research on MLP Structures — Finance and law journal work on why MLPs became popular, what the incentive distribution rights really did, and why the structure fell out of favor when market conditions changed.

-

McKinsey, BCG, and Wood Mackenzie Reports on Steel Decarbonization — The big-picture transition story: EAF growth, blast furnace decline curves, and what “decarbonization” actually means for timelines and technology choices.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music