Sensata Technologies: The Industrial Sensing Giant You've Never Heard Of

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

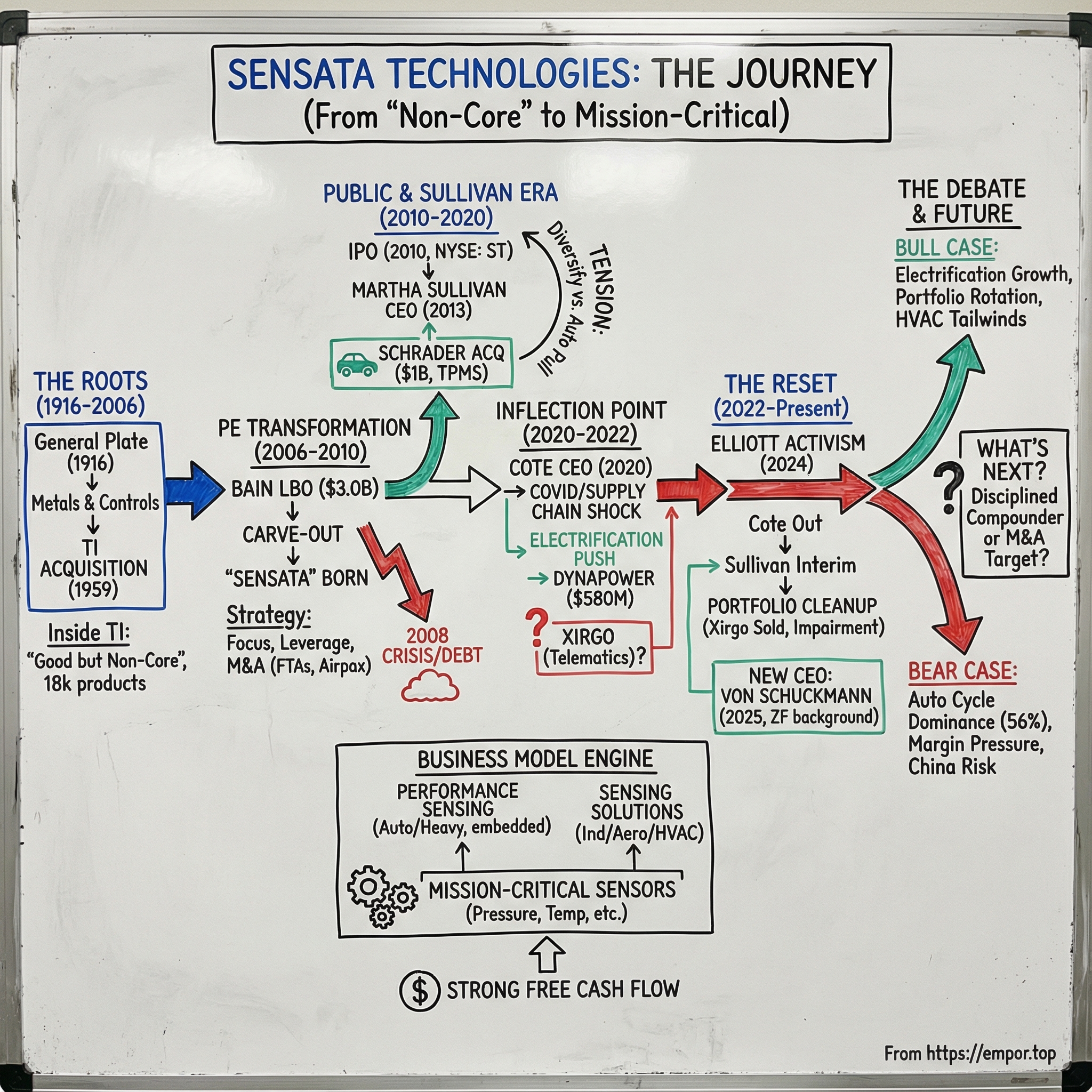

Picture this: you’re cruising down the highway when your dashboard lights up with a tire-pressure warning. That little alert is the last step in a chain that starts with a sensor the size of a small coin—one designed to catch a slow leak before it becomes a blowout. There’s a very good chance that sensor came from a company you’ve never heard of: Sensata Technologies.

Now zoom out. The same kind of invisible, mission-critical hardware shows up all over the physical world: inside cars and trucks, in aircraft systems, in HVAC units keeping buildings livable, and in industrial machines that keep factories moving. Sensata is one of the world’s leading suppliers of sensing, electrical protection, control, and power-management solutions. It operates in 13 countries, and its products show up in an almost comically wide range of end markets: automotive, appliances, aircraft, industrial and heavy vehicle, heating and air-conditioning, data and telecom, plus everything from military applications to marine and recreational vehicles.

That breadth is the point. Sensata is an industrial company hiding in plain sight—roughly a $4 billion business that functions like the nervous system of modern machinery. In 2024, revenue was $3,932.8 million, which makes Sensata a real mid-cap industrial player. And yet most people—even plenty of investors—would struggle to tell you what Sensata actually does, why its products matter, or why the company has been so hard for the market to value.

Because this isn’t just a “sensors are everywhere” story. Sensata is also a story about how businesses get built in the modern industrial economy. It’s a corporate carve-out that became a private equity transformation: a division once tucked inside Texas Instruments, pulled out and turned into a standalone company through leverage, operational focus, and a steady diet of acquisitions. It’s a portfolio-rotation story too—how you try to move away from a historical cash-cow end market while still relying on that cash flow to fund the pivot. And at its core, it’s a story about mission-critical components: the parts nobody notices when they work, but everyone cares about when they fail—sold into customer relationships where you can be deeply embedded and still get priced down year after year.

Operationally, Sensata runs through two segments: Performance Sensing and Sensing Solutions. Performance Sensing includes sensors and high-voltage solutions used in automotive and heavy-vehicle subsystems—things like tire pressure monitoring, thermal management, and electrical protection. And that’s the irony: the product list can sound almost painfully unglamorous—pressure sensors, temperature sensors, protection devices—until you realize these are the components that help prevent breakdowns, improve efficiency, and keep people safe.

Over the next two decades, Sensata goes from a Texas Instruments castoff, to a newly minted public company, to a business constantly wrestling with one big reality: the automotive gravitational pull. Even after years of strategic effort, the company has remained heavily tied to the auto cycle. That tension—between what Sensata has been and what it wants to become—is what gives this story its stakes.

II. The Deep Roots: From General Plate to Texas Instruments (1916–2006)

In April 1916, a Massachusetts entrepreneur named Rathbun Willard took out a $50,000 loan and started a company in a place you wouldn’t expect to be the seedbed of a modern sensor giant. On April 24, 1916, he founded the General Plate Company to provide “gold plate” for the jewelry makers just over the border in Rhode Island. Production began modestly, in the cellar of the Bigney Building in Attleboro.

That humble start matters, because it hints at a recurring theme in industrial technology: the origin often looks nothing like the destination. Gold plating for jewelry sounds worlds away from automotive pressure sensors, but the connective tissue is real—materials science, process control, and precision manufacturing. Those capabilities compound.

General Plate quickly hit a practical constraint: space. Willard bought more than 200 acres in an area then called Cat-O-Nine-Tail Swamp, and in 1926 the company put up its first building at 34 Forest Street.

The real inflection point came in 1931, when General Plate merged with Spencer Thermostat Company to form Metals & Controls Corporation. It was a marriage of two skill sets that turned out to be unusually durable: metal processing on one side, temperature-sensing and control on the other. Put them together and you get the core of what this lineage would become known for—precision components that survive harsh environments and still measure accurately.

That combination eventually drew the attention of Texas Instruments. In 1959, TI acquired Metals & Controls as it expanded beyond its early roots, building a broader technology portfolio. The business that would later become Sensata then lived inside Texas Instruments for almost five decades—1959 through 2006.

It was a stable home, but also a limiting one. As TI increasingly defined itself as a semiconductor company, sensors and controls didn’t fit the story. Inside a conglomerate, “good business” can still be “non-core.” And non-core businesses rarely get the CEO-level attention they need to become great businesses.

By the early 2000s, that division was no small side project. It was highly engineered and application-specific, producing roughly 18,000 different products and shipping over a billion units each year. And in the December 2006 acquisition of FTAS, more than 900 employees were added.

So TI’s problem wasn’t that the sensors business was broken. It was that it was the wrong kind of right: profitable, complex, and operationally demanding—without generating the investor excitement that semiconductors did. Private equity, meanwhile, looked at that exact profile and saw a classic carve-out opportunity.

The stage was set.

III. The Bain Capital Era: Private Equity Transformation (2006–2010)

On April 27, 2006, the sensors and controls business officially separated from Texas Instruments and entered a new chapter. That day, investment funds associated with Bain and CCMP Capital Asia Ltd. (together, the Sponsors) completed the acquisition of the business for $3.0 billion in cash, plus $31.4 million in transaction fees and expenses. After the deal, the Sponsors indirectly owned 99 percent of Sensata’s outstanding ordinary shares.

The price tag was huge, but the logic was classic private equity: take a strong, operationally complex division that had been “non-core” inside a bigger company, give it singular focus, tighten the machine, and build scale—then exit through an IPO or a sale.

First, the company needed a name and a story of its own. “Sensata” comes from the Latin word sensata, meaning “those gifted with sense.” The logo leaned into that idea too, drawing inspiration from Braille—touch translated into information. It was branding with intent: a way to explain, in human terms, what a sensors company really does.

With independence came a clearer operating frame. Sensata was positioned as a global designer and manufacturer of customized, highly engineered sensors and controls, with manufacturing in the Americas and Asia. It organized itself into two global business units—sensors and controls—and leaned hard on the strengths that mattered in this kind of business: deep technical expertise, long customer relationships, a broad product portfolio, and a cost structure that could win programs year after year.

One of the most important anchors in the transition was Martha Sullivan. Long before she became CEO, she was already central to how the business ran. She had joined Texas Instruments in 1984, built her career inside the organization, and developed deep expertise in automotive sensing. In 2006, she became Sensata’s Chief Operating Officer, then President in 2010—continuity that mattered when everything else about the company was being rewired.

Then Bain did what Bain does. It started buying.

The first acquisition came just months after the carve-out. In November 2006, Sensata purchased the First Technology Automotive and Special Products business from Honeywell. For the year ended December 31, 2005, FTAS had sales of approximately $69 million.

More followed quickly. In March 2007, Sensata bought SMaL Camera from Cypress Semiconductor. In July 2007, it acquired Airpax Holdings, Inc. and its four subsidiaries.

The strategy was straightforward: use the stable cash flows of the core business to roll up adjacent sensing and controls assets, expanding the platform and widening the set of end markets and applications Sensata could serve. But there’s a trade-off baked into that playbook. The company took on significant debt to do the 2006 acquisition—and then added more debt with the follow-on deals. Interest expense became a major line item, and so did the amortization of intangibles from all that M&A. The result was uncomfortable on paper: despite a fundamentally healthy operating business, Sensata reported significant net losses in each period after the 2006 acquisition.

That’s the LBO paradox. Cash flow can be strong, but the income statement can look ugly—especially if you’re eventually planning to tell your story to public-market investors.

And then the macro environment turned from challenging to brutal. The 2008 financial crisis hit like a sledgehammer. Global vehicle production collapsed, and a leveraged company with heavy automotive exposure was suddenly fighting for oxygen. Sensata responded the way disciplined industrial operators tend to: it cut costs, renegotiated where it could, and tried to protect the engineering capability that made the franchise valuable. But the crisis slowed the timeline, and any near-term path to an IPO became harder to justify.

In 2009, Sensata sold the former SMaL Camera business to Melexis. It was an early sign of portfolio pruning—an admission that not every deal fits, and a willingness to exit something that wasn’t core. That instinct, to shape the portfolio rather than just accumulate assets, would show up again and again in Sensata’s history—sometimes cleanly, sometimes not.

IV. Going Public and the Martha Sullivan Era (2010–2020)

By early 2010, the world had stopped feeling like it was in freefall. The credit markets were functioning again. IPO windows were cracking open. And Bain finally had a path to do what private equity came to do in the first place: exit.

Sensata Technologies Holding N.V. went public in March 2010, listing on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker ST. The IPO priced at $18 per share and sold tens of millions of ordinary shares, raising hundreds of millions of dollars and giving Bain and the other sponsors partial liquidity. It was a classic carve-out arc: pull a non-core business out of a conglomerate, lever it, reshape it, then bring it to public markets once the timing is right.

Public ownership changed the job. Now Sensata had to do two things at once: run the operational playbook that made it a good business, and tell a coherent story that public investors could believe in—especially for a company that, since the LBO, had reported losses on paper thanks to debt and acquisition accounting.

Then came the leadership handoff that would define the next decade. In a planned transition effective at the start of 2013, Martha Sullivan became CEO and a director, succeeding Thomas Wroe. She kept the President title too, a signal that this wasn’t a strategic break from the past so much as a doubling down on operational execution.

Sullivan’s rise stood out in industrial technology, a sector that has historically been light on female CEOs. But inside Sensata, it made perfect sense. She’d joined Texas Instruments in 1984 and held roles that touched the commercial and technical heart of the business—Precision Controls Marketing Manager, Automotive Marketing Manager, North American Sensors General Manager—before running the sensors products unit globally and becoming a TI Vice President in 1998. By the time Sensata was on its own, she wasn’t learning the business. She was the business.

Under Sullivan, Sensata leaned hard into two moves that can coexist, but create tension: keep buying, and try to diversify.

The defining deal of the era landed in 2014. Sensata agreed to acquire the Schrader group from Madison Dearborn Partners for an enterprise value of $1.0 billion. Schrader was the global leader in tire pressure monitoring systems, or TPMS—exactly the kind of sensor category where regulation turns into guaranteed demand. TPMS had become standard on cars in North America and was spreading globally, pushed by safety and fuel-economy rules. Schrader had helped pioneer the category with OEMs, and Sensata said Schrader held more than 50% market share across key regions.

The story was compelling. A growing market. A dominant player. Real technical capabilities in pressure sensing and communication. And a piece of industrial heritage: Schrader is widely regarded as the first manufacturer of the pneumatic tire valve, the industry standard used across motor vehicles worldwide.

Financially, Sensata framed the deal the way experienced acquirers do: near-term dilution, longer-term payoff. The company expected the acquisition to be modestly dilutive to adjusted earnings per share in 2014, then accretive in 2015, with additional upside after integration and debt paydown—and more upside if and when TPMS adoption ramped in China. Sullivan’s rationale was direct: Schrader extended Sensata’s leadership in pressure sensing and opened up access to a large and rapidly growing low-pressure sensor market, with TPMS as the biggest immediate wedge.

But the Schrader deal also made the company’s core tension harder to ignore. If the goal was to reduce reliance on automotive, buying the TPMS leader was, in many ways, a bigger bet on automotive. Sensata kept growing, but autos remained the gravitational center—exposing the company to production cycles and the relentless price-down culture that comes with being a Tier 1 supplier. And the logic loop was real: diversification required capital, but most of Sensata’s capital came from the automotive engine management was trying to lessen dependence on.

Late in the decade, you can see Sullivan trying to sharpen the portfolio—not just add to it. In 2018, Sensata agreed to sell its valves business to Pacific Industrial for an enterprise value of about $173 million, with closing expected in the third quarter. That business—mechanical valves for tire and fluid-control applications, plus aftermarket tire hardware—had come along with Schrader. In 2017, it generated roughly $117 million in revenue and $20 million in adjusted EBIT. It performed well, Sensata said, and had improved since 2014. But it wasn’t the kind of differentiated, secular-growth sensing franchise Sensata wanted to be known for.

Sullivan put it plainly: Sensata wanted to focus on mission-critical, complex sensing solutions where it could differentiate and earn leading margins. The valves business didn’t fit that strategy, and she believed it would be better positioned inside Pacific, where it could be the center of the story instead of a bolt-on.

That instinct—prune what doesn’t fit, concentrate on what does—would only get more important. And in the years ahead, it would get harder to execute cleanly.

V. The Inflection Point: COVID, Supply Chain Crisis, and Strategic Reset (2020–2022)

Sensata’s CEO transition in early 2020 was timed about as badly as possible—at least from a macro standpoint. The company announced that Jeffrey Cote, then President and Chief Operating Officer, would succeed Martha Sullivan as Chief Executive Officer effective March 1, 2020.

Cote was a 13-year veteran inside Sensata by that point. He joined in 2007 as Chief Financial Officer, later served as Executive Vice President and Chief Administrative Officer, and became COO in 2012. And his path to the top job was a little unusual for an industrial CEO: before Sensata, he ran operations as Chief Operating Officer at Ropes & Gray LLP, and earlier held senior operating, financial, and administrative roles at Digitas.

On March 1, 2020, Cote officially took over as CEO and President. Within weeks, the world changed. COVID-19 shut factories across the globe, and automotive production—still Sensata’s primary end market—fell off a cliff.

Cote moved fast and spoke plainly about the moment. “What we are seeing is truly unprecedented and it warrants an equivalent response,” he said, announcing salary reductions and unpaid time off across leadership and the board. The message was simple: protect the company, protect the team, and survive the storm.

Then came the rebound—and it was chaos in the opposite direction. Demand snapped back faster than supply chains could handle, and manufacturers everywhere got whiplash trying to restart production. Sensata leaned on what it considered one of its core strengths: a flexible manufacturing footprint. Management pointed to a sharp sequential revenue jump—“a testament to our leading positions and our strength and flexibility of our manufacturing model.”

Coming out of that volatility, Cote pushed Sensata harder into its electrification thesis. If the world was going to electrify transportation, heating, and industry, then the “boring” plumbing of that transition—sensing, protection, and power management—should be a great place to be.

The biggest swing came in 2022, when Sensata completed the acquisition of Dynapower Company LLC for $580 million in cash. Dynapower, a provider of energy storage and power conversion solutions, was expected to generate more than $100 million in annualized revenue in 2022 with roughly 20% EBITDA margins, and management said it was positioned for rapid growth. The pitch was a clear extension of the electrification story: Dynapower would help Sensata deliver “highly engineered, mission-critical power conversion systems” into renewable energy storage, industrial, and defense customers.

Strategically, Dynapower was bold. It moved Sensata closer to clean-energy infrastructure—adjacent to its historical strengths, but with new customer relationships and a different competitive set.

But this was also the period when Sensata’s capital allocation started to attract more criticism. Under Cote’s tenure—March 1, 2020 through April 30, 2024, when he resigned from all company positions—one deal in particular became a focal point: Sensata’s entry into telematics through the acquisition of Xirgo Technologies for $400 million in April 2021. Investors increasingly viewed telematics as non-core, and the move added to the sense that Sensata was trying to do too many things at once, in the middle of brutal end-market turbulence.

By the time the supply chain crisis, automotive volatility, and dealmaking all piled on top of each other, the setup was there: aggressive M&A, challenging markets, and growing skepticism—exactly the mix that tends to invite activists.

VI. The New Sensata: Electrification, Activism, and the Next Chapter (2022–Present)

By 2024, all the volatility, mixed M&A results, and a stock that hadn’t kept up created the kind of opening activists live for. Enter Elliott Investment Management—one of the most feared names in the business.

On April 29, 2024, Sensata Technologies Holding plc announced it had entered into a Cooperation Agreement with Elliott. Elliott was already Sensata’s largest investor, with an economic stake at or above $600 million, around 10%. Given Elliott’s playbook, it was hard not to assume the position could be even larger.

What happened next was fast, and it was decisive. Sensata announced that Jeff Cote, CEO and President, had informed the board of his intention to retire and step down from the board, effective April 30, 2024. Even the formal language in the agreement captured the moment: “the Company shall take all such actions as are necessary to accept the resignation of Jeffrey Cote.”

The board moved to stabilize the company. Martha Sullivan—Sensata’s prior CEO and a board member since 2013—returned as Interim President and CEO while the board launched a search for a permanent leader. Sullivan, 62 at the time, brought instant credibility: she’d run Sensata from 2013 to 2020 and, before that, had held senior roles going all the way back to the TI era, including COO and President. If Sensata needed a steady hand, this was it.

The market loved the reset. Sensata shares jumped sharply in after-hours trading on the news of the Elliott pact and the CEO transition.

Elliott also got a seat at the table. After what the company described as a “constructive dialogue,” Sensata appointed Elliott’s nominee, Phillip Eyler, to the board effective July 1, 2024. He joined the CEO Search Committee and the Nominating and Governance Committee—exactly the levers you’d expect an activist to want.

Then came the portfolio cleanup. One of the clearest signs that Elliott’s influence was real was how quickly Sensata unwound the telematics bet that had become a lightning rod with investors. On September 30, 2024, Sensata’s Insights business was acquired by Balmoral Funds and rebranded back to Xirgo Technologies—effectively reversing the 2021 Xirgo acquisition and putting telematics back outside Sensata’s walls.

The financial statements captured the pain of the transition. Operating income for the nine-month period included large third-quarter 2024 charges: about $150 million of goodwill impairment tied to Dynapower, plus roughly $141 million in restructuring and other charges related to the loss on the sale of the Insights business and additional product lifecycle management exits.

That Dynapower impairment landed particularly hard. It was an admission that the growth expectations embedded in the $580 million purchase price hadn’t shown up on schedule. Dynapower stayed in the portfolio, but the write-down made clear Sensata was now in “prove it” mode on that deal.

By December 2024, the board wrapped the CEO search. On December 17, 2024, Sensata announced it would appoint Stephan von Schuckmann as CEO effective January 1, 2025.

On paper, it was a very pointed choice. Von Schuckmann brought more than 20 years of global automotive and industrial experience, most recently as a Member of the Board of Management at ZF Friedrichshafen AG, where he led the company’s electric mobility division—ZF’s largest division, with annual revenue of more than $12 billion. If Sensata wanted a leader fluent in the transition from conventional powertrains to electrified ones, it just hired someone who had lived that transformation at scale.

The company’s full-year 2024 results read like an organization trying to get its footing back. “Sensata had a strong finish to the year with fourth quarter revenue exceeding expectations, full year free cash flow increasing by over 40% compared to prior year, and adjusted operating margin increasing for the fourth consecutive quarter,” von Schuckmann said.

Cash generation was still a bright spot. Sensata produced $551.5 million of operating cash flow and $393.0 million of free cash flow in 2024. It also used the year to keep de-risking the balance sheet—redeeming $700 million of bonds in July 2024 that otherwise would have matured in October 2025.

But the forward view showed how much pruning was underway. “Taking into consideration the approximately $300 million of revenue exited in 2024, we expect that full year 2025 revenue will be organically flat with 2024 at approximately $3.6 billion,” said Brian Roberts, EVP and CFO.

The strategic narrative, though, stayed consistent: electrification, everywhere. Not just EVs and charging, but the electrification of buildings through HVAC and heat pump innovation, and battery and controls solutions in material handling.

And yet the old gravitational pull hadn’t disappeared. About 56% of Sensata’s 2024 net sales still came from automotive—down from the historical 60%-plus, but still the majority. The diversification challenge remained. The difference now was that Sensata had a new CEO, an activist watching closely, and far less patience to get it wrong.

VII. The Business Model Deep Dive

To understand Sensata, you have to get comfortable with a simple idea: this company doesn’t sell “sensors” in the abstract. It sells very specific answers to very specific engineering problems—devices and systems that sit inside mission-critical machines and quietly keep them safe, efficient, and compliant.

At a high level, Sensata Technologies Holding plc develops, manufactures, and sells sensors and sensor-rich solutions, electrical protection components and systems, and related products used across mission-critical systems in the United States and internationally.

The business is organized into two complementary segments.

The first is Performance Sensing. This is the side of Sensata that lives closest to vehicles—cars, on-road trucks, and off-road equipment. It includes sensors and high-voltage solutions that support functions like tire pressure monitoring, thermal management, electrical protection, regenerative braking, powertrain (engine and transmission), and exhaust management. In practice, this segment is about selling deeply embedded components—sensors, high-voltage contactors, and related solutions—into platforms that ship in high volumes and run on brutal performance and cost requirements.

The second segment is Sensing Solutions, which tilts more toward industrial and aerospace. It develops and manufactures application-specific sensor and electrical protection products used in a wide range of markets, including appliances, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC), semiconductors, and aerospace. It also includes areas like operator controls and EV charging infrastructure. On the clean energy side, the portfolio spans products and solutions such as high-voltage contactors, rectifiers, energy storage systems, and electrical sensing products for industrial, transportation, stationary, and commercial energy conversion and storage markets—covering applications like battery-energy storage, microgrids, and renewable energy generation and storage.

Zoom in another level, and the product list gets broad fast: pressure sensors, temperature sensors, position sensors, current and voltage sensors, switches, and thermal management components. Sensata also sells more integrated systems tied to battery management, power conversion, and vehicle electrification.

The real “why this works” is less about any single product and more about how these products get sold. A lot of Sensata’s revenue is driven by a design-in model. These parts typically aren’t pulled off a shelf and dropped into a machine. They’re engineered into the application, often in collaboration with the customer, and that process is where a supplier can earn its keep.

That design-in dynamic creates switching costs—especially in automotive and aerospace, where qualification requirements are intense and the consequences of failure are serious. Once a Sensata sensor is designed into a vehicle platform or an aircraft system, swapping suppliers mid-stream is expensive, risky, and time-consuming. That tends to create visibility: a design win can translate into years of production revenue. But it comes with a catch. Platforms age out, programs end, and the company has to keep winning the next generation of designs to replace what rolls off.

Manufacturing is the other pillar. Sensata’s global footprint is meant to do two things at once: stay cost-competitive and stay close to customers. The company’s view is that having manufacturing around the world lets it supply global platforms regionally with the same product—and reduce exposure to disruptions that can hit long supply chains.

Then there’s the other engine Sensata has leaned on for years: acquisitions. Sensata has acquired 18 companies, building capability and scale faster than it likely could through organic growth alone. Done well, that can be a real advantage in a fragmented industrial landscape. Done poorly—or done at the wrong price—it can become a drag. And the recent history around Xirgo and Dynapower is a reminder that integration risk and valuation risk are always part of the bill.

Finally, the financial glue that holds this model together: cash. Even through a messy few years, Sensata continued to generate meaningful cash flow. In 2024, the company generated operating cash flow of approximately $700 million, giving it flexibility to pay down debt and return capital. For the twelve months ended December 31, 2024, Sensata repurchased about $68.9 million of shares and paid $72.2 million in dividends.

VIII. Competitive Landscape & Market Position

Sensata plays in a market that’s both enormous and unforgiving: sensors are everywhere, and almost nobody has anything close to a monopoly. Even within something as “simple” as pressure sensing, share is spread across a long tail of competitors. In 2021, the top ten players in the global pressure sensor market accounted for only about 15.5% of the total—meaning the other 80-plus percent was chopped up among many smaller companies.

In that same 2021 snapshot, Sensata Technologies, Inc. was the largest single player, but with only about 2.84% share. It sat in a tight cluster with Siemens (2.69%), Rockwell Automation (2.07%), Amphenol (1.96%), Honeywell (1.28%), Robert Bosch (1.23%), ABB (1.12%), Infineon (1.07%), Emerson (0.71%), and TE Connectivity (0.53%). That’s the reality of this business: lots of credible suppliers, each strong in their own niches, and no one so dominant that the market naturally “tips” in their favor.

The competitive set also changes depending on where you’re looking. In pressure sensors, the global names show up over and over—Honeywell, ABB, Emerson, Amphenol, TE Connectivity, and Sensata among them. Players like Amphenol and TE Connectivity have leaned into miniaturization and ruggedized designs for harsh environments, and they’ve used acquisitions, product innovation, and partnerships to widen their footprint.

Zoom out to industrial sensing more broadly, and the landscape gets even more crowded. Sensata faces companies like ABB, Amphenol, AMS AG, and Rockwell Automation in a segment that’s both large and fragmented, with competition coming from every angle. Then you get into newer categories tied to electrification—like EV current sensing—where the competitive mix shifts again to include specialists such as LEM Holding and Allegro Microsystems, alongside the diversified incumbents.

Where Sensata really shines is in specific applications where it has a defensible position built over decades. Tire pressure monitoring is the cleanest example. Thanks to Schrader, Sensata has a leadership position in TPMS, a category with regulatory tailwinds and deep OEM integration. In industrial sensing and aerospace, though, Sensata often runs into diversified giants with bigger budgets and broader cross-selling relationships. And in EV sensing, it’s a multi-front fight: traditional incumbents adapting their portfolios, plus newer entrants built specifically around electrification.

Across the industry, consolidation keeps reshaping the map. Joint ventures and acquisitions are increasingly aimed at building more integrated sensor solutions, including multimodal systems and portfolios that incorporate more intelligence and software. The direction of travel is clear: customers want fewer components and more complete solutions.

All of that feeds into Sensata’s core positioning challenge: it’s a “tweener.” It’s not big enough to automatically win on scale against companies like Honeywell or TE Connectivity. But it’s also too large, and spread across too many end markets, to be a pure-play specialist that investors can value as the obvious category winner. That can be a strength—Sensata has flexibility and multiple growth angles—but it also makes the story harder to tell, and harder to get paid for.

IX. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-LOW

Industrial sensing has real barriers to entry, but they aren’t uniform. In mission-critical applications—automotive safety systems, aerospace controls, anything where failure becomes a recall or worse—new suppliers don’t just show up and start winning business. Qualification cycles can run 18 to 24 months, and customers want a proven track record, not a promise.

At the same time, parts of sensing are closer to a commodity than a craft. In those segments, lower-cost manufacturers, especially in Asia, can come in and compete on price. So the moat is less “sensors are hard” and more “being trusted inside a safety-critical design is hard.”

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Sensata has meaningful scale, which helps when negotiating with suppliers. But the semiconductor supply chain crisis was a harsh reminder that leverage has limits when inputs are specialized and capacity is tight. Some components and materials aren’t easily substitutable, and in a disruption, it doesn’t matter how big you are if the part simply isn’t available.

That’s why the make-versus-buy question never really goes away. Vertical integration can protect supply, but it also adds complexity and capital needs. Sensata has to keep threading that needle.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

If you want to understand the pressure Sensata lives under, start with automotive OEMs. They are among the toughest buyers in the world, and annual price-downs are just table stakes—suppliers are expected to get cheaper over time even as quality improves and requirements get stricter.

There’s also the reality check that helped set the stage for activism: from Elliott’s initial action date on April 29, Sensata’s stock fell over the one-, three-, and five-year periods, while the Russell 2000 performed better over those same horizons. In other words, customers have leverage, and so does the market—and Sensata has felt both.

Design-ins do create lock-in. Switching a sensor supplier mid-platform is painful, slow, and risky. But customers still hold plenty of power when programs renew and the next platform is up for bid. Industrial and aerospace customers tend to be less concentrated and more relationship-driven, which generally improves pricing dynamics, but automotive still sets the tone.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

In a lot of Sensata’s world, there’s no true substitute for sensing. You can’t replace a physical pressure sensor on an aircraft hydraulic system with software. You can’t “digitally infer” your way out of measuring temperature in a battery thermal management system.

Where substitution does happen, it’s usually within the category—technology shifts like MEMS replacing older sensor designs. That can disrupt incumbents. Sensata’s advantage is that it has typically adapted as the technology base has evolved, rather than getting stranded on the wrong side of the curve.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

Competition is intense, and it’s structural. The pressure sensor market is fragmented, with lots of credible suppliers. In mature automotive sensing categories, that fragmentation runs head-first into relentless OEM cost pressure, which keeps margins under strain.

Then you add the land grab in electrification. EVs and adjacent electrified systems are the growth markets everyone wants, which means the fight for “sensor content per vehicle” is crowded and aggressive. Sensata has strong positions, but it’s battling incumbents and specialists all chasing the same programs at the same time.

X. Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

Scale helps in manufacturing. Bigger volume can mean lower unit costs, more purchasing leverage, and the ability to spread fixed costs across a larger base. But industrial sensing isn’t a winner-take-all market where the biggest player automatically wins everything.

Sensata has argued that it’s among the largest suppliers of sensors and controls across the key applications it competes in, and that its position comes from a mix of technological expertise, long-standing customer relationships, a broad portfolio, and a competitive cost structure. The catch is that much of the business is still highly application-specific. Customization limits how far pure scale advantages can go.

Network Effects: NONE

There’s no flywheel here. Sensata’s sensors don’t become more valuable because more people use them. This is a classic industrial components market: competitive, fragmented, and driven by specs, quality, reliability, and cost—not platform dynamics.

Counter-Positioning: NOT APPLICABLE

Sensata isn’t the scrappy disruptor with a new model that incumbents can’t copy without hurting themselves. In most of its categories, Sensata is the incumbent. The fight is about defending share against larger diversified rivals and specialists carving out niches—not flipping the industry’s rules.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG

This is the heart of Sensata’s advantage. Most of what Sensata sells is designed in, not picked off a shelf. Products are frequently tailored to the customer’s system, and Sensata has a track record of adding real engineering value in that process.

Qualification cycles—often 12 to 24 months—make switching slow and painful. In safety-critical applications, especially automotive and aerospace, the risk of a component failure makes customers conservative about changing suppliers. But switching costs aren’t a blank check. At program renewal, customers can and do use competitive bids to push price concessions.

Branding: WEAK

Sensata isn’t a consumer brand. Drivers don’t know whose sensor triggers the warning light, and building owners don’t care who made the component inside the HVAC unit.

What does matter is reputation inside the OEM: with engineers and procurement teams, brand is shorthand for quality, responsiveness, and technical competence. That helps win design-ins, but it rarely translates into durable pricing power.

Cornered Resource: WEAK

Sensata doesn’t appear to have a singular “you can’t copy this” resource in the Hamilton Helmer sense—no unique patent trove or exclusive access that permanently blocks competitors. Engineering talent and customer relationships are valuable, but not truly cornered.

Acquisitions like GIGAVAC and Sendyne added specialized capabilities, but those capabilities, in principle, can be replicated over time by other well-funded competitors.

Process Power: MODERATE

The second real pillar is process. Sensata has built operational and execution capabilities that are hard to see from the outside and difficult to replicate quickly. The company positions itself as an extension of customers’ engineering teams—using shared knowledge, tight collaboration, and a deep global bench to deliver tailored solutions in demanding, mission-critical environments.

This also shows up in the company’s M&A integration muscle. Even with recent missteps, integrating 18-plus acquisitions creates institutional learning. And against larger, slower competitors, speed and responsiveness—especially in customization—can be a meaningful edge.

Overall Assessment:

Sensata’s competitive strength comes mostly from two places: switching costs created by design-in, and process power built through operational execution and integration know-how. Those are real advantages, but they’re moderate—helpful in winning and keeping programs, not strong enough to eliminate price pressure in a crowded industry.

So the long-term bet isn’t that Sensata has an unbreakable moat. It’s that the markets around it keep expanding—electrification, HVAC, and broader industrial sensing—and that management can keep rotating the portfolio toward those growth areas while protecting margins along the way.

XI. The Investment Debate: Bull vs. Bear

The Bull Case:

Electrification of Everything Creates Content Growth. The core bet is simple: as transportation, buildings, and industrial systems electrify, the number of places you need sensing, protection, and control goes up, not down. EVs, in particular, shift the “sensor map” from engines and exhaust toward batteries, thermal management, and high-voltage systems. Sensata has argued that its battery-electric vehicle content—helped by products like GIGAVAC—now exceeds what it typically provides on gas and diesel platforms.

Portfolio Rotation Is Underway. This is the optimistic interpretation of the last few years: Sensata is exiting lower-value lines, cleaning up the portfolio, and pushing investment toward areas with better growth and longer runways. In 2024, sales from electrification-related products grew 22%, a data point bulls point to as proof that the strategy is showing up in real demand, not just slide decks.

HVAC and Climate Tech Are Secular Growth Markets. Heat pumps, more efficient refrigeration, and the boom in data center cooling are all trends that don’t rely on the auto cycle. Regulations and efficiency standards reinforce that demand over time, and they create exactly the kind of “mission-critical, compliance-driven” applications where Sensata tends to do well.

Free Cash Flow Generation Is Strong. Even in a messy transition, Sensata kept producing meaningful cash. In 2024, it generated $551.5 million of operating cash flow and $393.0 million of free cash flow. The bull case says that kind of cash generation gives the company room to pay down debt, fund R&D, and keep reshaping the portfolio without starving the core business.

New Leadership Brings Fresh Perspective. Bulls like the optics and the substance of the CEO change. Stephan von Schuckmann has deep experience across both conventional and electrified powertrains, and a track record built inside a major global supplier. If Sensata’s next chapter is about executing the electrification pivot with more discipline, this is the kind of operator you’d hire.

Activist Involvement Provides Accountability. Elliott’s presence raises the cost of drifting. In the bull framing, that means tighter capital allocation, faster portfolio decisions, and fewer “nice-to-have” acquisitions that don’t fit the core sensing and power-management thesis.

Valuation Reflects Pessimism. The stock has often traded as if Sensata is stuck as a cyclical auto supplier. Bulls argue that if the mix continues shifting toward electrification, HVAC, and industrial markets, the company should earn a higher multiple more in line with diversified industrial peers—especially if margins recover.

The Bear Case:

Show Me Story. Bears have heard the diversification narrative for years. And despite progress, automotive was still 56% of 2024 net sales. The skepticism is that Sensata keeps promising a mix shift, but the gravity of auto volumes and auto pricing continues to define the company.

Automotive Exposure Remains Dominant. Even if the long-term direction is right, the near-term reality is brutal: automotive cycles, production volatility, and annual price-downs are still the biggest drivers of results. As long as that’s true, Sensata can’t fully escape being valued like an auto-facing supplier.

EV Sensor Content Story May Be Overhyped. Yes, EVs create new sensing needs. But they also remove some legacy content tied to internal combustion complexity. Bears argue the “more sensors in EVs” claim is not automatic; what matters is net content per vehicle and whether Sensata wins the right programs at acceptable margins.

Chinese Competition Is Accelerating. Electrification is a global race, and China is moving fast. Local sensing and component companies are improving quickly and often have an inside track with domestic OEMs. Add geopolitics, localization pressure, and supply chain uncertainty, and the China angle becomes both a competitive and strategic risk.

Margin Pressure Appears Structural. The bear case isn’t that margins are temporarily down—it’s that the economics of mature automotive categories, combined with intense competition, keep compressing profitability over time. If that’s true, Sensata may never regain the margin profile investors want, even with a better mix.

Capital Allocation Track Record Is Questionable. Recent history gives bears plenty of ammunition. In 2024, operating income reflected a roughly $150 million goodwill impairment tied to Dynapower, alongside other charges as the company restructured and exited parts of the portfolio. The Dynapower and Xirgo chapters feed the view that Sensata has, at times, paid too much or strayed too far from its core.

Management Execution Risk. A new CEO, an activist on the board, and a major strategic reset can be a powerful combination—or a distracting one. Bears worry the company could spend the next few years managing transitions, integration issues, and restructurings instead of compounding steadily.

What to Watch:

Investors should monitor several key indicators:

- Automotive as percentage of revenue — Is the mix actually shifting, or just the messaging?

- Non-automotive revenue growth rates and margins — Are HVAC and industrial scaling, and are they really more profitable?

- Electrification product wins — Are wins translating into durable, ramping revenue?

- Free cash flow conversion — Can Sensata keep generating cash while investing and restructuring?

- Capital allocation decisions — Under new leadership, does the company stay disciplined on M&A, exits, and balance sheet priorities?

XII. Key Lessons & Takeaways

For Founders & Operators:

The PE Transformation Playbook. Sensata is a clean example of what private equity does well when the setup is right: take an overlooked division inside a conglomerate, give it a focused mandate, install leadership that lives and breathes the business, tighten operations, and then use M&A to build a bigger platform. Texas Instruments’ 2006 decision to sell its Sensors & Controls division to Bain wasn’t just a transaction—it was the moment Sensata became a company with the freedom, and the pressure, to define its own strategy.

M&A as Core Competency. “Buy” can be a strategy, not just an event—but only if you treat it like a capability. That means discipline on what you buy, what you pay, and how you integrate. Sensata’s record shows both sides of the coin: deals like Schrader and GIGAVAC strengthened the core; moves like Xirgo and the post-deal reality of Dynapower show how quickly an acquisition can become a distraction, or worse, a write-down.

The Portfolio Rotation Challenge. Rotating a business away from its historical profit engine is one of the hardest moves in corporate strategy. The legacy business throws off the cash you need to invest in the future—but if you starve it, performance deteriorates faster than you can replace it. Sensata’s story is a reminder that diversification isn’t a slogan; it’s a multi-year balancing act with no clean playbook.

Being Mission-Critical Matters. Design-ins and qualification cycles create real switching costs, and that’s a genuine advantage. But “mission-critical” doesn’t mean “pricing power.” Customers still push for annual price-downs, especially in automotive, and they still re-bid work when platforms refresh. Sensata’s edge is durability of relationships and embedded designs—not immunity from competition.

The Tweener Trap. Sensata has been a frustrating company to categorize, which is exactly the problem. It’s not a pure auto supplier, not a classic diversified industrial, and not a software-like “tech” story either. Being too big to be nimble and too small to overwhelm competitors with mega-scale creates a perpetual positioning challenge—and, often, a perpetual valuation debate.

For Investors:

Private Equity Exit Dynamics. The post-IPO period matters. When a company comes public after a leveraged PE chapter, shareholder incentives, selling pressure, and capital structure often shape the stock as much as the underlying business does.

Cyclicality vs. Secular Growth. It’s easy to say “electrification beneficiary.” It’s harder to prove it in the mix. With automotive still 56% of 2024 net sales, the right question is whether the secular growth vectors are truly becoming large enough to change what drives results.

The Boring Industrial Compounder. Sensata isn’t flashy—and that can be the point. If a business like this generates steady free cash flow, improves margins, and allocates capital well, it can compound quietly for a long time. The catch is always the same: execution has to be real, and the entry price matters.

Valuation vs. Quality. A discount can be opportunity—or it can be the market accurately pricing risk: competitive intensity, automotive exposure, and uneven capital allocation. The only way to tell is to understand what the business actually is, where it earns money, and whether the strategy is showing up in results.

Key KPIs to Track:

-

Automotive Revenue as % of Total — The cleanest signal of whether diversification is happening. If the percentage falls because non-automotive grows faster, the pivot is working. If it stays flat, the “new Sensata” story is still mostly aspiration.

-

Adjusted Operating Margin — Margin trajectory is the scoreboard for portfolio decisions, pricing, and operational discipline. For the first quarter of 2025, guidance reflects a return to more normal seasonality, with the company expecting margins to improve as revenue builds into the year—reaching 19.0% or better in the second quarter, then improving further in the second half of 2025.

-

Free Cash Flow Conversion — Cash is what funds the transition: paying down debt, investing in new platforms, and returning capital. Tracking free cash flow relative to adjusted net income helps separate real earning power from accounting noise—and shows whether the strategy is self-funded or balance-sheet dependent.

XIII. Epilogue: Where Does Sensata Go From Here?

Sensata entered 2026 with a new CEO, an activist looking over management’s shoulder, and a noticeably cleaner portfolio after the divestitures and exits of the prior year. The core electrification thesis was still the same—more electrified systems mean more sensing, protection, and control. The harder part was timing: the revenue ramps kept taking longer than anyone wanted.

Von Schuckmann has been clear about the posture. “Our back-to-basics approach continues to deliver. We are building resiliency in our business and we are pleased to report a strong second quarter where we exceeded our revenue and earnings commitments and significantly improved our free cash flow,” he said.

From here, Sensata’s path branches in a few directions, and the range of outcomes is wide. If the company can compound organically—especially in electrification and HVAC sensing—public markets tend to reward that with a better multiple. Sensata can also keep using M&A, but with a tighter filter: smaller, more disciplined deals that add real capability rather than complexity. And there’s always the endgame option that hovers over any mid-cap industrial with valuable niches: if Sensata can’t unlock the value itself, a larger industrial player might decide to do it for them—either buying the whole company or carving out the most strategic pieces.

Technology adds another layer of uncertainty. The upside story is compelling: sensing paired with edge compute and AI/ML can turn “measurement” into “interpretation”—systems that detect anomalies early, predict failures, and optimize performance in real time. But the same shift can reshape the competitive set. If value migrates up the stack toward software and integrated platforms, Sensata has to make sure it’s not just supplying components while others capture the economics.

Then there’s China—arguably the most complicated variable in the whole equation. Sensata has cautioned that its guidance did not reflect potential impacts of recently announced tariffs that may be imposed, or threatened to be imposed, by the United States on Canada, China, Mexico, and other countries, or any retaliatory actions. Layer on geopolitical tension, customer localization demands, and rapidly improving domestic Chinese competitors, and you get a strategy problem that doesn’t respond to the old playbook of “build where demand is and win on engineering and scale.”

On the brighter side, the secular tailwinds are real. Heat pump adoption continues to grow, pushed by efficiency standards and the electrification of heating. Data center expansion keeps driving demand for sophisticated thermal management. Industrial regulation keeps tightening, and that creates demand for sensing solutions that enable compliance and efficiency. These are exactly the kinds of trends Sensata wants to ride because they’re less tied to the auto production cycle and more tied to policy, energy economics, and infrastructure buildout.

The ultimate test is simple to state and hard to execute: can Sensata deliver steady growth and margin improvement while navigating brutal automotive dynamics, building credibility in newer markets, and proving that the portfolio now matches the strategy? This company has lived through a century of reinvention—ownership changes, industry cycles, leadership transitions. The next chapter will decide whether Sensata earns its keep as a standalone industrial technology compounder, or whether the clearest path to value is as part of a larger platform.

For investors, it’s the classic “boring business” dilemma. The story won’t make headlines, but the fundamentals matter: meaningful cash flow, real switching costs in designed-in components, and end markets that the modern world can’t function without. At the right price, with disciplined execution, that mix can be a great long-term setup. The open question is whether Sensata can turn “should” into “did”—and whether today’s price fully reflects both the upside and the risks.

XIV. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Links & References:

-

Sensata Investor Relations — Annual reports (10-K) from 2020–2024, especially the Management Discussion & Analysis sections on strategy, end-market mix, and segment performance.

-

Bain Capital Case Studies — Academic and case-based writeups on the 2006 LBO of TI’s sensors division and the operating and M&A playbook that followed.

-

"The Private Equity Playbook" by Adam Coffey — A useful lens on how PE-backed companies actually run: leverage, operations, add-ons, and the incentives that shape decisions.

-

Industry Reports: MarketsandMarkets and Freedonia Group — Market sizing and competitive landscape coverage across sensors, automotive electrification, and industrial demand trends.

-

Automotive News Archives — Reporting around the Schrader acquisition and the evolution of TPMS as regulations pushed the category from “nice-to-have” to standard equipment.

-

Sensata Quarterly Earnings Call Transcripts — Good checkpoints include Q4 2020 (COVID shock and recovery), Q2 2022 (Dynapower and electrification positioning), and the most recent quarters covering portfolio exits and the reset.

-

Elliott Investment Management 13D Filings — Primary-source detail on activist involvement, ownership, and the cooperation agreement framework.

-

"The Innovator's Dilemma" by Clayton Christensen — Not about Sensata specifically, but a strong framework for how incumbents can get disrupted when value shifts within a technology stack.

-

Trade Publications: Control Engineering, Sensors Magazine — More technical reads on sensing applications, reliability requirements, and where the technology is heading.

-

Competitor Investor Materials — TE Connectivity, Amphenol, and Honeywell annual reports and investor decks for how adjacent giants describe the same markets—and where Sensata fits by comparison.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music